Archives

COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Syrian Refugees

Abstract

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately affected refugee populations, with refugees suffering higher rates of exposure and infection and a higher risk of severe disease and death due to socioeconomic disparities, reduced access to healthcare, and underlying medical conditions. Widespread vaccination is critical to reduce the individual morbidity and mortality as well as the public health burden of COVID-19. However, the uptake of COVID-19 vaccination among refugee populations is unknown.

Methods: We used validated surveys to quantitatively assess COVID-19-related fear and vaccine hesitancy in a population of Syrian refugees living in Turkey.

Results: COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is critically high among Syrian refugees, with 85% of participants refusing vaccination. However, COVID-19 fear is also high, with over 90% of participants expressing fear of contracting or dying from COVID-19. Misinformation and false beliefs regarding vaccine efficacy and side effects contribute to the discrepancy between high fear of an infectious disease and low rates of acceptance of a life-saving preventive measure.

Conclusion: COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is alarmingly high in Syrian refugee populations. Targeted interventions to improve vaccine acceptance in refugee populations are urgently needed.

Keywords

COVID-19, Vaccine hesitancy, Refugees, Syria, Turkey

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused over 650 million recorded cases and over six million deaths worldwide as of December 2022 per World Health Organization statistics. Refugees and asylum-seekers have been disproportionately affected by all aspects of the pandemic. Refugees are at higher risk of initial exposure to SARS-CoV-2, are more likely to be hospitalized with COVID-19, and have a higher mortality rate compared to non-refugee populations [1]. A multitude of factors contribute to increased risk of in this population. Refugees are more likely to reside in crowded living conditions, to work low-wage public-facing jobs, to have less access to public health messaging in their native language, and to have lower health literacy compared to non-refugee individuals [2-8]. Once infected, refugees have a higher risk of severe COVID-19 symptoms, of requiring hospitalization due to COVID-19, and of death due to COVID-19. This is likely due to a higher incidence of chronic comorbidities, delays in seeking medical attention, and exclusion from the healthcare system, among other causes. Special attention to the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on refugees is urgently needed.

Turkey harbors the world’s largest population of refugees and the world’s largest Syrian refugee population, with 3.65 million Syrian refugees and an additional 330,000 refugees from other countries [9]. Turkey has been profoundly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, with over 12 million infections, nearly 92,000 deaths, massive inflation, and an unemployment rate of up to 40% [10]. Even prior to the pandemic, the refugee population in Turkey placed humanitarian and economic strain on the country. In 2020, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)’s budget for refugees and asylum-seekers in Turkey was 365 million US dollars (USD); however, the sum of all available funds was only 131 million USD, a gap of 234 million USD [11].

Vaccination, combined with non-pharmaceutical methods such as social distancing and use of masks, offers the world’s best chance at curtailing the COVID-19 pandemic. Multiple effective and safe vaccinations to prevent COVID-19 have been developed and widely implemented with infection reduction rates of over 90% and excellent safety profiles. Unfortunately, vaccine hesitancy, defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “the reluctance or refusal to vaccinate despite the availability of vaccines,” is common in many populations. Given that refugees are at increased risk of COVID-19 exposure, infection, severe disease, and death, vaccination of this population is critically important, and vaccine hesitancy in this group is life-threatening. However, refugee and migrant populations have dismally low vaccination rates compared to non-refugee populations. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccination rates for other preventable infectious diseases, such as measles-mumps-rubella (MMR), polio, and diphtheria-pertussis-tetanus (DPT), had been persistently low for decades in refugee populations compared to non-refugee populations [12]. With regard to the COVID-19 vaccine, as of June 2021, 85% of COVID-19 vaccine doses administered had been given in high- and middle-income countries, but 85% of refugees reside in developing countries [13]. Even within vaccine administration programs in developing countries, refugees are neglected: for example, in Lebanon in April 2021, refugees and migrants comprised 30% of the country’s population, but only 2.9% of vaccinated individuals [14].

Low COVID-19 vaccination rates among refugees are multifactorial. Some contributors are systemic, including lack of healthcare coverage or access to care for refugees, lack of vaccine information in refugees’ language, lack of transportation or financial means to obtain vaccination, and perceived fear of detention when presenting for medical care [15]. However, COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is prevalent in refugee populations as identified by qualitative interviews [16]. These investigations identified misinformation and false beliefs as major drivers of vaccine hesitancy: for example, that COVID-19 is a hoax, that COVID-19 is a “Western disease,” that the government cannot be trusted, and that the COVID-19 vaccine contains microchips [17]. Facebook, TikTok, Whatsapp, and YouTube were cited as primary sources of COVID-19-related information [17].

Objectives

A rigorous understanding of the motivations, attitudes, and fears regarding vaccination is critically needed in order to decrease vaccine hesitancy and improve vaccination rates in refugee populations. In this study, we present the first quantitative investigation of refugee COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy using a validated questionnaire.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted in January 2022 among Syrian refugee patients in Turkey. Data were collected from patients aged 18 and older who presented for outpatient care at a public medical facility in Istanbul, Turkey. Patients who had already received any COVID-19 vaccine were excluded. Informed consent was obtained from each participant. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of XXX (IRB# XXX).

COVID-19-related fear was assessed via the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S). FCV-19S was developed in 2020 by a multinational group from Hong Kong, Iran, the United Kingdom, and Sweden [18]. FCV-19S assesses multiple aspects of fear related to COVID-19, including vulnerability to infection, fear of dying, and psychological and physical symptoms of anxiety. FCV-19S has robust psychometric properties and provides a reliable quantification of the severity of fear of COVID-19. Response patterns are not affected by respondent age or gender. The scale has since been implemented and validated in numerous other European, Middle Eastern, and Asian countries, including Turkey.

General vaccine hesitancy sentiment was assessed using the World Health Organization (WHO) Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE) definition. Assessment of vaccine hesitancy by the SAGE definition can be done via as few as three questions regarding vaccine behaviors; this definition and question set have been widely employed worldwide [19].

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy was assessed using a version of the Vaccination Attitudes Examination (VAX) scale. VAX is a measure of anti-vaccination sentiment that was initially developed in 2017 by a cooperative group from the United States and New Zealand [20]. Initially developed to measure general anti-vaccination attitudes, the VAX scale can be adapted to assess attitudes toward specific vaccines. The original VAX scale has high internal consistency and validity, and responses are significantly associated with both past vaccine behavior and future vaccine intentions. The VAX scale has been adapted to create the Attitudes toward COVID-19 Vaccine Scale to assess COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, and has been implemented in several countries, including the United States, France, and India.

For the present study, assessments were translated from English into Arabic, and participant responses were translated back into English. A pilot with 20 participants was initially performed. The questionnaire and the logistical arrangements were found feasible by the participants.

Statistical analysis: Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software version 24 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA). Results are presented as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and as the mean and standard deviation for continuous variables.

Results

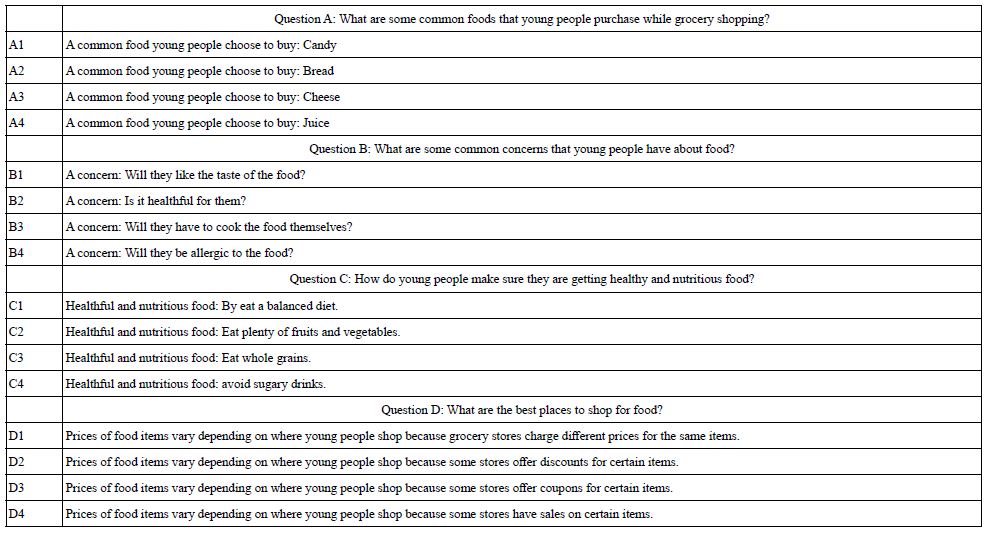

A total of 321 participants were recruited to the study and completed the survey. The median participant age was 43 (range: 18-75). Forty-three percent of participants identified as female. The majority of participants were illiterate (60%), were not working (62%), and lived in large households (household size of five to six, 41%; household size of seven to nine, 42%). Thirty percent of participants reported a personal history of COVID-19 infection. Twenty-seven percent of participants reported a personal history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and/or hyperlipidemia. Demographic characteristics of the cohort are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of study participants

|

Median (range) |

|

| Age | 43 (18-75) |

| N (%) | |

| Gender identity | |

| Female | 139 (43.3) |

| Male | 182 (56.7) |

| Education | |

| Illiterate | 193 (60.1) |

| Primary school graduate | 71 (22.1) |

| Secondary school graduate | 57 (17.8) |

| Work status | |

| Not working | 200 (62.3) |

| Working irregularly | 41 (12.8) |

| Working regularly | 80 (24.9) |

| Size of household | |

| 3-4 | 57 (17.8) |

| 5-6 | 130 (40.5) |

| 7-9 | 134 (41.7) |

| Personal history of COVID-19 infection | |

| Yes | 94 (29.3) |

| No | 227 (70.7) |

| Personal history of chronic disease (DM, HTN, and/or HLD) | |

| Yes | 86 (26.8) |

| No | 235 (73.2) |

Fear of COVID-19 was common among participants, as assessed by FCV-19S. Ninety-three percent of participants reported feeling uncomfortable when thinking about COVID-19, and 75% of participants reported fear of dying of COVID-19. Forty to 65% of participants also reported physical symptoms of anxiety (palpitations or insomnia) related to fear of COVID-19. Results of the FCV-19S assessment are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2: Fear of COVID-19

|

Yes [N (%)] |

No [N (%)] |

|

| I am most afraid of Coronavirus-19. | 300 (93.5) | 21 (6.5) |

| It makes me uncomfortable to think about Coronavirus-19. | 300 (93.5) | 21 (6.5) |

| My hands become clammy when I think about Coronavirus-19. | 180 (56.1) | 141 (43.9) |

| I am afraid of losing my life because of Coronavirus-19. | 239 (74.5) | 82 (25.5) |

| When watching news and stories about Coronavirus-19 on social media, I become nervous or anxious. | 218 (67.9) | 103 (32.1) |

| I cannot sleep because I’m worrying about getting Coronavirus-19. | 127 (39.6) | 194 (60.4) |

| My heart races or palpitates when I think about getting Coronavirus-19. | 207 (64.5) | 114 (35.5) |

General vaccine hesitancy was common among participants. Seventy-one percent of participants reported refusing a vaccine for themselves or their child in the past, and 46% reported postponing a vaccine recommended by a physician. Vaccine hesitancy data are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3: Vaccine hesitancy

|

Yes [N (%)] |

No [N (%)] |

|

| Have you ever refused a vaccine for yourself or a child because you considered it as useless or dangerous? | 229 (71.3) | 92 (28.7) |

| Have you ever postponed a vaccine recommended by a physician? | 147 (45.8) | 174 (54.2) |

| Have you ever had a vaccine for a child or yourself despite doubts about its efficacy? | 0 (0) | 321 (100.0) |

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy was high among participants. Only 14% of participants stated that they would receive the COVID-19 vaccine. The remaining 86% of participants stated that they would refuse the COVID-19 vaccine. Of those respondents who refused vaccination, reasons for refusal were fear of side effects (78.5%), doubt about effectiveness (19%), and suspicion of short production timeline (2.5%). Attitudes toward COVID-19 Vaccine Scale response data are displayed in Table 4.

Table 4: Intentions regarding COVID-19 vaccination

| If a vaccine against the Coronavirus was available, would you get vaccinated? |

N (%) |

| Yes | 46 (14.3) |

| No | 275 (85.7) |

| If no, why? | |

| Fear of side effects | 216 (78.5) |

| Doubt about effectiveness | 52 (19.0) |

| Suspicion of short production timeline | 7 (2.5) |

Discussion

In this study, we present the first quantitative assessment of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and fear of COVID-19 in a refugee population using validated questionnaires. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is alarmingly high in this population: 86% of participants stated that they would refuse a COVID-19 vaccine. General vaccine hesitancy is also prevalent in this population, with more than 40% of participants reporting a history of refusing or postponing a recommended vaccine.

The prevalence of vaccine hesitancy in this large cohort of refugee patients is concerning given this population is at extremely high risk in every phase of an infectious pandemic, from initial infection to death. Firstly, migrants and refugees are at higher risk of infection with the Coronavirus compared to non-refugee populations. For example, in Denmark in May 2020, the incidence of COVID-19 in the migrant population was 240 per 100,000, compared to 128 per 100,000 among native Danish individuals [21]. Similarly, in Spain in April 2020, the incidence of COVID-19 in the migrant population was 8.81 per 1,000, compared to only 6.51 per 1,000 for native Spanish individuals [22]. The living conditions of refugees, which commonly involve camp-type settings with crowding and extensive use of shared spaces, likely contribute to the increased incidence in refugee populations: outbreaks have been observed in migrant shelters in many countries. Even in non-camp settings, refugees are more likely to reside in shared or overcrowded housing. For example, in a survey of Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, migrants were twice as likely to live in an overcrowded housing setting (17%, versus 8% of native-born individuals) [1]. Occupational risks also contribute to increased risk of contracting COVID-19 among refugee populations: refugees are more likely to be employed in public-facing jobs, such as retail, delivery, hospitality, and transport, thereby increasing the risk of COVID-19 exposure compared to other, non-public-facing jobs [23]. Furthermore, refugees generally have more tenuous financial means compared to non-refugee populations and are more likely to be employed in “no work, no pay” jobs such as those mentioned above, necessitating the continuation of work even in high-risk conditions [4,5,23].

Refugees are also at higher risk of hospitalization and mortality from COVID-19. In Denmark in September 2020, migrants made up 15% of COVID-19-related inpatient admissions, despite comprising only 9% of the population [21]. In Sweden, the relative risk of ICU admission for COVID-19 was five times higher for migrants from Africa and the Middle East than for native Swedish individuals [24]. Similarly, in Norway, the incidence of hospitalization due to COVID-19 was 147 per 100,000 in migrant populations, compared to 37 per 100,000 for native Norwegian individuals [2,25]. Certain ethnic groups are at even higher risk of poor outcomes, and studies specific to Syrian refugees have found dismal COVID-related mortality rates. In Sweden, Syrian migrants had a relative risk of death from COVID-19 of 6.14 compared to native Swedish individuals [26]. Excess mortality in Syrian migrants in Sweden was 220% in 2020, due overwhelmingly to COVID-19 deaths [26].

Thus, given the high risk of initial exposure, severe disease, and death in this population, the magnitude of benefit from vaccination in this population is enormous, and the consequences of vaccine hesitancy are catastrophic. For example, the resurgence of measles in the United States, Norway, and other countries in the early 2000s as a result of increased parental refusal of MMR vaccination was notable for outbreaks heavily concentrated in migrant and refugee populations. In two outbreaks in Minnesota, USA in the 2010s, 72% of cases occurred in members of the Somali community [27,28]. During this time period, MMR vaccination rates among two-year-old Somalis in Minnesota fell to 54%, from over 90% ten years prior [29]. Similarly, in a 2011 measles outbreak in Oslo, Norway, 80% of cases occurred in members of the Somali community, in which MMR vaccine rates were also noted to be low [29,30]. Unfortunately, the present study confirms that vaccine hesitancy continues to be a major barrier to vaccination among refugee communities with regard to COVID-19 vaccination. Interventions to increase vaccine uptake in refugee populations are critically needed.

Vaccine uptake can be improved by addressing each contributing factor to low vaccination rates. Systemic factors must be addressed on the institutional level. For example, although the national COVID-19 vaccine program in Turkey, the setting of the present study, includes all individuals living in the country regardless of immigration, refugee, or asylum-seeking status, public health and vaccine programs in some countries exclude refugees, either explicitly, or indirectly due to requirements for identification or documentation to be presented at the time of vaccination. Removing systemic barriers by making COVID-19 vaccines available to all individuals regardless of legal status, improving outreach in refugees’ native language, increasing vaccine convenience, and guaranteeing protection from detention when seeking healthcare will all increase vaccination rates in individuals who desire to be vaccinated.

However, the present study identified that unvaccinated individuals who desire to be vaccinated (but may be impeded from doing so by systemic factors such as those detailed above) are a small minority among the Syrian refugee population in Turkey; the vast majority of participants are refusing COVID-19 vaccination, with concern for side effects the most commonly cited reason for refusal. Therefore, removing systemic barriers to vaccination is not sufficient to improve vaccination rates. Education on vaccine effects must be provided and misinformation and false beliefs must be addressed to improve vaccine hesitancy.

Although the present study is the first to quantitatively assess COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in refugee populations using validated questionnaires, vaccine hesitancy in general has been well-studied. The most effective strategies for reducing vaccine hesitancy and improving vaccination rates overwhelmingly involve accessible, understandable health education from trusted sources. These strategies have been well-described by previous groups [31,32]; we briefly summarize the most common and salient points here. First, and perhaps most importantly, public health messaging must be available in refugees’ native language. In Turkey, a robust COVID-19 public health program is available via internet and a COVID-19 hotline is available via telephone, but these sources are only available in Turkish and English; 80% of Syrian refugees speak only rudimentary Turkish. An Arabic translation of the website or an Arabic language option for the telephone hotline would make this information more accessible for Syrian refugees. This model has been extremely successful in Sweden, where healthcare workers use telemedicine platforms nicknamed “Corona lines” to distribute COVID-19 educational information, triage respiratory symptoms, and instruct patients on appropriate quarantine and hygiene in Arabic, Somali, Tigrinya/Amharic, and Persian/Dari as well as the Swedish national languages. Second, vaccine development, testing, and approval information should be transparent and accessible to the public. As prior qualitative interviews cited above noted social media as the main source of COVID-19-related information for refugees, this information should be publicized via not only traditional media, but verified sources on social media as well. For example, national health ministries can use their official Facebook and other social media feeds to publicize vaccine information; this information should be in refugees’ native language, as discussed below. Specific provocative or culturally relevant false beliefs, such as concern that the vaccine contains pork products or causes infertility, should be targeted and addressed emphatically. The participants in the present study overwhelmingly indicated fear of side effects as the reason for vaccine refusal; public health information should emphasize the favorable side effect profile of COVID-19 vaccines. Third, personal storytelling from persons with whom refugee populations identify are effective means of appealing to individuals’ empathy and emotion. For example, for a target population of Syrian refugees, a public health announcement featuring a multigenerational Syrian family who accepted the vaccine can be filmed and widely publicized as described above. Fourth, community leaders, particularly religious leaders, such as imams at Syrian-majority Arabic-speaking mosques, should be partnered with for the dissemination of vaccine information. Fifth, refugee populations should be actively included in the process of public health education and information dissemination; for example, local public health committees should include at least one refugee member who participates in vaccination campaigns.

We found that fear of COVID-19 is also common in this population, with over 90% of participants reporting COVID-19-related fear. Notably, 75% of participants stated that they fear dying of COVID-19. The coexistence of high COVID-19 fear with high vaccine hesitancy seems contradictory. This contradiction emphasizes the role of misinformation, portraying the preventive measure as more harmful than the disease itself, in promoting vaccine hesitancy in this population. However, COVID-19 fear may become a motivation for participants to agree to vaccination if misinformation is replaced with accurate information about the efficacy and safety of COVID-19 vaccines.

The limitations of our study include its design as a cross-sectional survey, which represents the attitudes of the survey participants at one time point, and does not assess changes in attitudes over time. The demographic and clinical variables assessed, such as comorbidities and history of COVID-19 infection, were self-reported by participants, and were not verified by the investigators. The study was restricted to Syrian refugees in an urban metropolis. It may not be generalizable to other ethnic refugee populations, or to refugees in rural areas.

Conclusion

Refugee populations are at high risk of COVID-19 exposure, infection, severe morbidity, and mortality. Fear of COVID-19 infection is high in this population, with over 90% of participants reporting COVID-19-related fear. However, despite high levels of fear the disease, COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is contradictorily and critically high among Syrian refugees in Turkey, with over 80% of individuals refusing vaccination. Fear of side effects is the most common reason for refusal of vaccination. Targeted public health outreach interventions are critical to improve vaccination rates in this vulnerable population.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- OECD (2020) What is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on immigrants and their children? Paris: OECD.

- Indseth T, Grosland M, Arnesen T, Skyrud K, Klovstad H, et al. (2021) COVID-19 among immigrants in Norway, notified infections, related hospitalizations and associated mortality: A register-based study. Scand J Public Health 49: 48-56. [crossref]

- Intervention GMoHNPHODoESa. Epidemiological surveillance in points of care for refugees/migrants weekly report week 14/2020. Greek Ministry of Health National Public Health Organization Department of Epidemiological Surveillance and Intervention; 2020.

- Giordano C (2020) Freedom or money? The dilemma of migrant live-in elderly carers in times of COVID-19. Gend Work Organ.

- Wang FTC, Qin Weidi (2020) The impact of epidemic infectious diseases on the wellbeing of migrant workers: A systematic review. International Journal of Wellbeing 10.

- Chiarenza A, Dauvrin M, Chiesa V, Baatout S, Verrept H (2019) Supporting access to healthcare for refugees and migrants in European countries under particular migratory pressure. BMC Health Serv Res 19: 513.

- Kizilkaya MC, Kilic SS, Bozkurt MA, Sibic O, Ohri N, et al. (2022) Breast cancer awareness among Afghan refugee women in Turkey. EClinicalMedicine 49: 101459. [crossref]

- Sayan M, Eren MF, Kilic SS, Kotek A, Kaplan SO, et al. (2022) Utilization of radiation therapy and predictors of noncompliance among Syrian refugees in Turkey. BMC Cancer 22: 532. [crossref]

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Fact Sheet: Turkey. 2021.

- G S. The impact of COVID-19 on poverty in Turkey. The Borgen Project; 2021 13 July 2021.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [Internet]. 2021.

- Roberton T, Weiss W, Jordan Health Access Study T, Lebanon Health Access Study T, Doocy S (2017) Challenges in Estimating Vaccine Coverage in Refugee and Displaced Populations: Results From Household Surveys in Jordan and Lebanon. Vaccines (Basel) 5. [crossref]

- ER (2021) On COVID vaccinations for refugees, will the world live up to its promises? The New Humanitarian.

- Waddell B (2021) States That Have Welcomed the Most Refugees from Afghanistan. US News and World Report.

- Observatory Report: Left Behind: The State of Universal Healthcare Coverage in Europe. Brussels: Médecins du Monde; 2019.

- Salibi N, Abdulrahim S, El Haddad M, Bassil S, El Khoury Z, et al. (2021) COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in older Syrian refugees: Preliminary findings from an ongoing study. Prev Med Rep 24: 101606. [crossref]

- Crawshaw AF, Deal A, Rustage K, Forster AS, Campos-Matos I, et al. (2021) What must be done to tackle vaccine hesitancy and barriers to COVID-19 vaccination in migrants? J Travel Med 28. [crossref]

- Ahorsu DK, Lin CY, Imani V, Saffari M, Griffiths MD, et al. (2020) The Fear of COVID-19 Scale: Development and Initial Validation. Int J Ment Health Addict 1-9. [crossref]

- Rey D, Fressard L, Cortaredona S, Bocquier A, Gautier A, et al. (2018) Vaccine hesitancy in the French population in 2016, and its association with vaccine uptake and perceived vaccine risk-benefit balance. Euro Surveill 23. [crossref]

- Martin LR, Petrie KJ (2017) Understanding the Dimensions of Anti-Vaccination Attitudes: the Vaccination Attitudes Examination (VAX) Scale. Ann Behav Med 51: 652-660. [crossref]

- Institut SS (2020) COVID-19 I Danmark. Epidemiologisk trend og fokus: Herkomst (etnicitet). Copenhagen. Statens Serum Institut.

- Guijarro C, Perez-Fernandez E, Gonzalez-Pineiro B, Melendez V, Goyanes MJ, et al. (2021) Differential risk for COVID-19 in the first wave of the disease among Spaniards and migrants from different areas of the world living in Spain. Rev Clin Esp (Barc) 221: 264-273. [crossref]

- Reducing COVID-19 transmission and strengthening vaccine uptake among migrant populations in the EU/EEA. Stockholm; 2021 3 June 2021.

- Utrikesfödda och covid-19: Konstaterade fall, IVAvård och avlidna bland utrikesfödda i Sverige 13 mars 2020 – 15 februari 2021. Stockholm: Swedish Public Health Agency (Folkhalsomyndigheten); 2021.

- Covid-19 blant personer født utenfor Norge, justert for yrke, trangboddhet, medisinsk risikogruppe, utdanning og inntekt2021. Folkehelseinstituttet; 2021.

- Hansson E, Albin M, Rasmussen M, Jakobsson K (2020) [Large differences in excess mortality in March-May 2020 by country of birth in Sweden]. Lakartidningen 117. [crossref]

- Gahr P, DeVries AS, Wallace G, Miller C, Kenyon C, et al. (2014) An outbreak of measles in an under vaccinated community. Pediatrics 134: e220-228. [crossref]

- Leslie TF, Delamater PL, Yang YT (2018) It could have been much worse: The Minnesota measles outbreak of 2017. Vaccine 36: 1808-1810. [crossref]

- Tankwanchi AS, Jaca A, Larson HJ, Wiysonge CS, Vermund SH (2020) Taking stock of vaccine hesitancy among migrants: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 10: e035225.

- Vainio K, Ronning K, Steen TW, Arnesen TM, Anestad G, et al. (2011) Ongoing outbreak of measles in Oslo, Norway, January-February 2011. Euro Surveill 16. [crossref]

- Thomas CM, Osterholm MT, Stauffer WM (2021) Critical Considerations for COVID-19 Vaccination of Refugees, Immigrants, and Migrants. Am J Trop Med Hyg 104: 433-435. [crossref]

- Aborode AT, Fajemisin EA, Ekwebelem OC, Tsagkaris C, Taiwo EA, et al. (2021) Vaccine hesitancy in Africa: causes and strategies to the rescue. Ther Adv Vaccines Immunother 9: 25151355211047514. [crossref]

Voice Analysis for Decisions in Clinical Practice

Verbal and nonverbal communication generates various debates and feelings between individuals, finally improving knowledge and experiences and, last but not least, influencing people’s health. Mental activity is mainly influenced by visual, sound, and smells perception. A person’s appearance, colour use, scent, and movement in a specific environment create diverse motion pictures going along with excitement, indifference, or discomfort, according to data processing. The music expresses various themes; miscellaneous musical compositions decoded by matching corresponding musical instruments or human voices determine emotions, relaxation, and even attentiveness. Verbal communication skills are necessary to improve an individual’s professional, cultural and social life; the words’ meaning and energy influence people’s well-being. The effects of the usage of the words in the written format are different from the spoken words since the speech energy, controlled by the nervous system, adds value to the words’ significance. Communication skills by terms make a difference between individuals and initiate numerous actions according to their relevance, physical characteristics of words’ transmission, intended recipient’s sensitivity, and context.

In this digital era, an individual can put an idea in a writing format or convert it into a say that instantly goes up to the intended recipients using IT devices.

Speech or the words’ ordering analysis offers information about the individual:

- Level of Expertise

- Skills for knowledge translation in practice

- Emotions

- Possible medical conditions

- Well-being

Speech depicts its coordination in appearance; deficiencies at various levels for command and execution pathways indicate the voice’s signs of interest in clinical practice. Voice characteristics combined with the breathing data reflect blood flowing in the human body. Heart activity, the respiratory system’s function, and gravitational waves influence human body fluids movement; the digestive, endocrine, skeletal, respiratory system, kidney, and liver functions influence blood composition. The mind activity affects all these variables interplay, conveying the words and voice expression. Even so, the heart function and respiratory system, both under nervous system coordination, are seen as significant contributors to the voice function. Heart failure modifies the body’s fluid distribution and, subsequently, voice characteristics that change from one stage to another in its evolution.

Each person’s voice is distinctive and adaptable to various internal and external stimuli. AI supply leads to fast voice analysis and prediction of disorders in appearance or evolution. In this digital era, a video visit or only a phone call visit can offer sufficient details about individuals, including data health. For the medical team, an e-visit may be considered appropriate when necessary. For the patient, an in-person or e-visit represents a convenient option to get care in need. The patient experience can be appreciated /measured by his words’ composition to express gratitude, voice attributes, and sentiment analysis, preferably using AI supply. Subjective voice analysis and artificial intelligence utilization offer another perspective in clinical practice. Recent medical literature highlights ambitious AI projects for using the voice function in diagnosis. Therefore, according to individual financial status, there will be a wide range of options for the disease’s management in clinical practice. But only by using a mobile phone can the patient and the physician be connected to successfully control the patient’s disorders. The art of using the voice for analysis and decisions in clinical practice defines us as professionals in the community we serve.

Formative Evaluation of Trauma-informed Content Provided to Undergraduate Nursing Students in NURS 466 – Community Health

Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of this Quality Improvement (QI) project was to complete a formative evaluation of Trauma Informed Care (TIC) content delivered in a population-focused health nursing course for senior-level undergraduate nursing students.

Methods: This was a descriptive study that gathered feedback from students about the Trauma Informed Care content. A survey was disseminated via Qualtrics after the module/lecture to gather information about the effectiveness of the lecture with respect to TIC content; timing of the lecture in the semester relative to clinical; attitudes/perceptions about the importance of the content and practical application.

Results: The content provided to the students in Nursing 466 Community Health improved students’ knowledge and skills related to providing Trauma Informed Care. Twenty-five participants from the Bachelor of Science in Nursing program at Gonzaga University participated

Keywords

Bachelor of nursing students, Trauma-informed care, COVID-19, Population health

Introduction

Current times require us to reexamine the content we are teaching community/public health nursing courses. The American Association of Public Health suggests that undergraduate public health nursing education should include information on trauma-informed care. Trauma-informed pedagogy in public health is not new, but the trauma related to the COVID-19 pandemic argues for making it a priority for all educators [1]. As a result of the pandemic many in the public have experienced trauma related to stress, financial impact, mental health, and physical well-being. We are faced with increasing rates of the COVID-19 pandemic, chronic conditions, infections, violence, and extreme weather events. All these circumstances point to a growing need for including content about Trauma Informed Care. The concept of trauma can be described as the following “Individual trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life-threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being [1]. This article reports the formative evaluation of adding content about Trauma Informed Care (TIC) to a population-focused health course in a Bachelor of Science (BSN) program at a private university in the inland northwest. Trauma-informed care is grounded in a set of four assumptions and six key principles as a framework. The four Rs of this Trauma-Informed Approach framework are: realize, recognize, respond, and resist re-traumatization [1]. “A program, organization, or system that is trauma-informed realizes the widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths for recovery; recognizes the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others involved with the system; and responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices, and seeks to actively resist re-traumatization (wording bolded in original text). These concepts are needed when working in population health. The content that was presented to this BSN group of students was organized into three sections. Section 1 was an overview of trauma-informed care, including the definitions of trauma and passive trauma. The trauma that those who experience homelessness or living in poverty were used as exemplars. This section included an overview of neurobiology, biopsychosocial needs of those experiencing homelessness, addiction, and/or poverty, and how the brain reacts to trauma. Section two described different types of traumas as a public health issue of our time and included an overview of Adverse Childhood Effects (ACEs). Exemplars of trauma related to ACES, as well as the pandemic, and natural disasters were presented. Section two also included an overview of current statistics related to trauma and how stress affects those that experience trauma. Section three addressed addiction, stress, and homelessness, how to return to a state of hope, how to implement and “do” trauma-informed care, transformation, and post-traumatic growth, and how not to re-traumatize individuals. Today we are not only faced with increasing diseases but also other traumatic events [2]. These events can be additional sources of trauma and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in public health. Although the need for nurses who can manage care along a continuum, implement evidence-based practice, work in multi-disciplinary teams, and integrate clinical expertise with knowledge of community resources is recognized, there is a lack of pedagogy that includes Trauma Informed Care [3]. This article describes the need for gathering formative information to add trauma-informed pedagogy to the current community health course. Using that formative information students provide could lead to changes made to the content before presenting it to the next group of students. The TIC content and knowledge could be implemented with the partnership between the school of nursing (SON) and local agencies where students complete public health clinicals.

Background

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is an essential need to prepare BSN students to not only care for individuals, but also for populations. According to SAMSHA “PHN practice is population-focused and requires unique competencies, skills, and knowledge. The important skills of analytic assessment, program planning, cultural competence, communication, leadership, and systems thinking, and policy are critical to the PHN role” [4]. Considering the pandemic, students’ interest may be piqued, and more students now see public health as a viable career option. It is important as faculty to recognize how Public Health will be taught in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic and have awareness of the trauma students could experience as new nurses taking care of COVID patients. The pandemic will have likely affected students as well as those prone to experience trauma among the population on a personal level either because they have become ill themselves or know someone that was affected by the virus. Furthermore, we need to consider the trauma of providing nursing care as a student to COVID patients. With this comes the need for trauma-informed care. Those from marginalized communities, the homeless population, and middle-class families have all been prone to traumatic experiences. Trauma Informed Care will ensure that the students gain knowledge and learning tools to serve their community with the knowledge of what Trauma Informed care is and how to reduce the risk of re-traumatization of clients [3]. The added pedagogy included Trauma Informed Care, to an already packed course that includes Disaster Preparedness, prioritizing social determinants of health, and the use of politics and policy. As faculty teaching, this group of “post-pandemic” students requires our pedagogy to include trauma-informed care so as to not exacerbate the client’s trauma in their public health clinicals’. The students at this school of nursing work in partnership with community sites such as shelters, homeless centers, the department of health, and many other agencies that provide services to populations that experience extreme poverty. The content took on a hybrid format of teaching online and in the classroom. Study findings provide information to inform revisions to the lecture to better meet the needs of students regarding this content.

Problem

Undergraduate Nursing students in this BSN program need Trauma Informed Care content. There is a gap in practice in the literature regarding Trauma Informed Care (TIC) taught in the BSN program. As a result of the COVID-19 Pandemic, many in the public may have experienced some form of trauma. There is a recurring recommendation from the American Public Health Association to start integrating TIC into the undergraduate curricula to educate BSN students on what Trauma Informed Care is and how to apply it to practice. This Quality Improvement Project aimed to examine the formative feedback and perceived value of the TIC content integrated into the BSN Community Health content.

Methods

This was a descriptive study within one BSN program. Students were enrolled in the senior-level community health class. Participation was voluntary and consent, as well as understanding the purpose and process of this project, was presumed by completion of the survey. Approval from the university’s IRB was obtained. The survey included both scaled and open-ended questions and students could voluntarily participate post-lecture. This article describes the preliminary findings of the perceived value of the TIC content and how students responded to the content delivered. The overall goal was to gather feedback about the effectiveness of the lecture and what changes need to be made for the future integration of TIC into the community health course. Participants were invited to participate in a Qualtrics survey sent out securely to their student email addresses during class by a staff member from the Dean’s Office. The investigator did not utilize email addresses herself but had the staff member send the surveys via email during class time from a remote location. The class roster was available to the staff member in the university system. Email addresses were not stored in any other system except for Qualtrics, the survey software. Once the survey and project were completed using Qualtrics, any email addresses used by the system were deleted. The investigator/course instructor informed the class (potential subjects) about the survey and study goals immediately before the lecture was given and informed the students of their ability to opt-in/out of the survey portion of the class, which occurred after the lecture was given. The survey consisted of 9 questions Likert-type scaled responses and 5 open-ended questions that were designed to gather feedback about the effectiveness of the lecture with respect to content; timing of the lecture in the semester relative to clinicals’; perceived importance of the content and practical application; information necessary to inform revisions to the lecture to make it tailored to the population-level needs of the students A Likert scale was used to gather quantitative data. Five of the questions were open-ended so that the students could provide written feedback exploring contextual factors [5,6]. Students’ narrative responses provided essential information about how to format the content and presentation for the next group.

Results

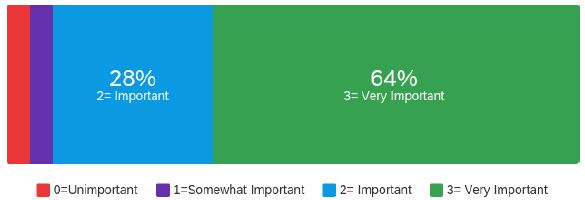

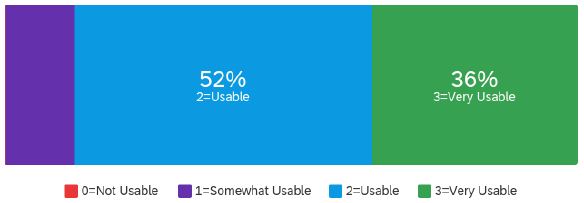

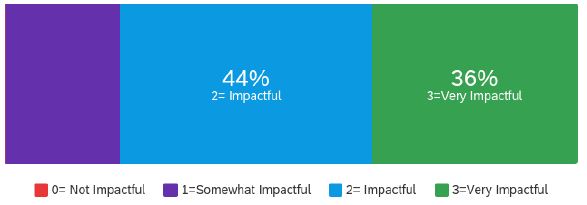

The Trauma Informed Care content is particularly valuable. This information also provides resources and tools for clinical practice use. The formative evaluation process used in the project provided valuable feedback to increase the quality of this content and delivery in the future to the next group of participants (students). The content provided to the students in Nursing 466 Community Health improved students’ knowledge and skills related to providing Trauma Informed Care. Twenty-five participants from the Bachelor of Science in Nursing program at Gonzaga University participated. Participating evaluators indicated that the education program was effective with respect to TIC content, the timing of the lecture in the semester relative to clinical, attitudes/perceptions about the importance of the content and practical application. Overall, 52% of participants felt the content was very understandable and 64% felt the content was very important to clinical practice. 56% of participants felt that the lecture was very understandable and 64% of the participants felt that the content was important to clinical practice. Participants (54%) felt that the content was usable in their practice and 44% of participants felt that it would impact their values and beliefs.

Demographics

Thirty-six students were enrolled in the course; 25 (69%) of participants completed the survey. This section outlines descriptive statistics performed for the Likert-type items that were a part of the questionnaire. To capture the students’ perceptions about the lecture, we included in the questionnaire questions such as “How informative was the lecture content” and “How relevant is this lecture to public health.” These questions were measured utilizing a Likert-type scale ranging. 0=Unimportant, 1=Somewhat important, 2=Moderately important, 3=Important, 4=Very important, 5=I don’t know.

Qualitative feedback identified strengths in the use of the open-ended questions related to how the lecture impacted the students’ values and beliefs about people who live with homelessness and substances; the length of the presentation; timeliness of the presentation; understandability of the lecture and lastly, what changes the participants suggested to improve the lecture for future students

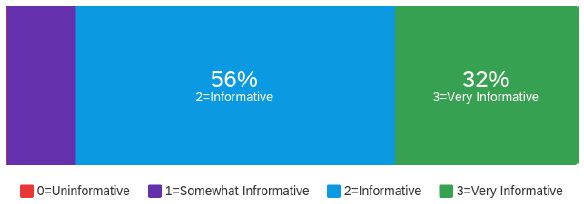

14 (56%) of respondents indicated that they found the lecture content to be informative, while 8 (32%) found it very informative. 21 (84%) of respondents found the lecture to be very relevant to the landscape of public health (Graph 1).

Graph 1: How informative was the lecture content

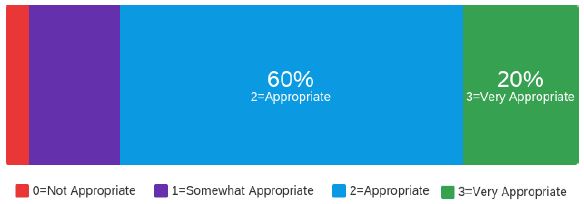

The students were asked to assess the length of the presentation. There were 25(60%) respondents that found the length of the presentation appropriate, while 5(20%) found it very appropriate (Graph 2).

Graph 2: Length of lecture

From this question, four different themes came to light. These themes are “different parts of the lecture “extending the lecture” “reduction in the lecture” and “additions to lecture.

The lecture was split up into three different sections and the students responded favorably to this and stated that “the presentation blended well together, and each section built off one another in a coherent manner”. There were some comments to extend the lecture by including more breaks and breaking apart what trauma-informed care is based on evidence-based practice and how that can be implemented in different communities. Related to the reduction in lecture the lecture was very consolidated, and students felt that there were a few slides that could be omitted. Some students suggested that perhaps it could be a multiday lecture. Additions to the lecture included suggestions to add some more videos and to include the ACE’s resources and some CDC resources.

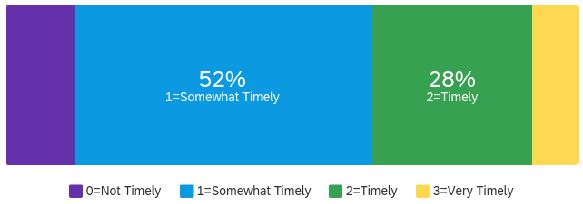

The timeliness of the lecture relative to the student’s clinical experiences was also assessed. There were 13 (52%) respondents that indicated that the lecture was somewhat timely;7 (28%) of respondents rated it as timely with respect to how early it was offered in the course (Graph 3).

Graph 3: Timeliness of the lecture

Timeliness was very important to the students, and they noted that it would be good for students to benefit from the content much earlier in their BSN curriculum. Students suggested receiving this content earlier in the semester of their program. It was stated that if they had this before their senior practicum it would be very beneficial. Others stated that they could see this content being threaded throughout their 4-year program. It was mentioned that trauma-informed care is something they are thankful they learned in their BSN track and wished to learn about it earlier.

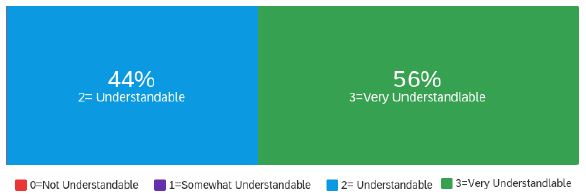

To assess the impact of the lecture, the following questions were asked: “How understandable was the presentation?” 14 (56%) Respondents felt the presentation was very understandable (Graph 4).

Graph 4: How understandable was the lecture

In response to this question Students mentioned that the topic was very relevant and helped them to see the “bigger picture”. Furthermore, they stated it would help them to identify paying attention to the information relating to ACEs among children, and being able to be an advocate for their patients was very important and helpful. Regarding the enjoyability of the lecture, students felt the PowerPoint was easy to follow and enjoyable to view.

“How important will this lecture be to your clinical practice,” 7 (28%) respondents felt that this was very important content for their clinical practice. 16 (64%) of respondents felt that this was very important content for their clinical practice (Graph 5).

Graph 5: Importance of lecture to clinical practice

“To what extent do you feel the content can be used by you in practice immediately?” 9 (36%) of respondents felt that the content could be used in practice immediately. 13 (52%) respondents felt that the content was usable for practice immediately (Graph 6).

Graph 6: Usability of lecture in practice

“To what extent did the lecture content impact your values and beliefs about people who live with homelessness and use substances?” 9(35%) of respondents felt that the content was very impactful and related to the above question. 11 (44%) of respondents felt it was impactful content (Graph 7).

Graph 7: Impact on values and beliefs

The first question analyzed reflects the impact that the content on the student’s values and beliefs about how people live with homelessness and substances. Students stated that the content was “extremely relevant” and is a significant component in promoting healing. Furthermore, students stated that “being educated on this topic allows us to be more aware and educate the community we work with during our community health clinical’ as future nurses, and it provides details about the struggles the homeless face since many of those experience some form of trauma that have been homeless before.” There were two sub-questions to this overall question.

- The next question addressed what students’ reaction was to the details about physiological and psychological content. Students responded that neurological and biological changes are important to consider and that it was “cool” to learn more about the actual physiology and physical and chemical changes that occur during trauma. Furthermore, it was stated that “the lecture did a really good job at explaining the reasoning behind homelessness and addiction”.

- Understanding what Adverse Childhood Effects (ACEs) are, was another area of this question that could influence the values and beliefs. Students state that understanding ACES “impacts the way you interact with patients in the clinical setting and broadened their perspective and strengthened their patience while working with this population and/or people who may have experienced ACEs or trauma in the past.

What changes would you make to the TIC lecture to improve it for future NURS 466 students? This question addressed any suggestions or changes to the lecture. Three themes emerged including resources, timing, and methods. Students suggested that they could offer specific resources or reference for patients or clients. They also asked how they can be sure to not re-traumatize patients. One of the students suggested asking someone who experienced trauma and overcame it to write a letter and share how they overcame their trauma. Timing again addressed the fact students wanted this content earlier in the semester, and program. Regarding methods, students mentioned more class discussions and asked for some real-life clinical examples. They also suggested part of the lecture be more interactive and include discussion.

Outcomes

Participating evaluators indicated that the education program was effective with respect to TIC content, the timing of the lecture in the semester relative to clinical, attitudes/perceptions about the importance of the content and practical application. Receiving formative evaluation to improve the development of a trauma-informed public health education program that provided evidence-based strategies and resources was the primary goal of this project. The results of the program demonstrated the effectiveness of using formative evaluation to develop a trauma-informed educational lecture for senior undergraduate Bachelor of Nursing students. The educational lecture overall demonstrated positive responses as to how the lecture impacted the students’ values and beliefs about people who live with homelessness and substances; the length of the presentation; timeliness of the presentation; understandability of the lecture and lastly, what changes the participants suggested to improve the lecture for future students. The findings of this educational lecture resonate with findings from other publications in relation to the importance of educational content on trauma-informed care for undergraduate nursing students to equip students with knowledge and understanding of trauma-informed care as it relates to public health. Emphasis on how timely this lecture was given is noted and will help change the timeliness of future lectures provided at the beginning of the student’s semester rather than toward the end.

Limitations

While the development of this Trauma-Informed care lecture reasonably provides strong evidence of the effectiveness of using formative evaluation to aid the development of the lecture within the sample population, it has some limitations. The first limitation is that it did not provide pre- and post-feedback as to what knowledge base the students had related to the content. It was limited only to one class in the undergraduate nursing program and the feedback is provided at the end of class when students are overloaded with the information they just received.

Future Directions

To overcome some of the limitations the respondents in the next part of this project will have a pre-and post-survey. The formative information provided in this project will better the lecture offered to the next student group in the Spring 2021 semester.

Funding

There was no funding involved for this project.

Conclusions

The trauma-informed care for public health lecture developed for senior undergraduate nursing students is powerfully applied by using evidence-based content and resources poised to provide an excellent delivery system for educating students. The lecture provided students with evidence-based content related to how trauma-informed care impacts public health. The student participants’ responses to the formative evaluations in developing this content were positive. In addition, the responses provided positive feedback and suggestions to improve the development of this lecture for future students.

References

- SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach (2014) Retrieved from Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

- Auerbach, J, Miller F (2020) COVID 19 Exposes the cracks in our already fragile mental health system. AJPH. [crossref]

- Abuelezam N (2020) Teaching public health will never be the same. AJPH 110. [crossref]

- National League for Nursing. NLN. 2022.

- Center for Disease Control. CDC. 2021.

- S Department of health and human services (HHS) (2014) Office of women’s (OWH) health trauma informed care (TIC) training and technical assistance initiative. Participant scales. Cross-site evaluation of the national training initiative on trauma informed care (TIC) for community-based providers from diverse service systems. Abt. Associates.

Monthly Fluctuation of Spike Protein-specific IgG Antibody Level against COVID-19 after COVID-19 Vaccination and Booster Shot

Abstract

We investigated the spike protein-specific IgG antibody levels against COVID-19 in a 64-year-old male medical staff periodically after two doses of COVID-19 vaccination and a third booster shot during a one-year period. The antibody levels increased after the two doses vaccination; however, it rapidly decreased in the first 3 months. The antibody levels increased again after the third booster vaccination. The antibody levels were remarkably higher than that after the two doses of vaccination and remained high for several months. We demonstrated that the third booster shot was significant in maintaining a high level of immunity against COVID-19.

Keywords

COVID-19, Vaccine, Antibody, Spike protein, Booster

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic [1], which began in early 2020, affected the examination and treatment of patients in hospitals, healthcare, and nursing care facilities in various ways. Vaccination for COVID-19 [2-4] initially started in the United Kingdom in December 2020 and subsequently started in Japan in February 2021, which has been effective in preventing the onset and reducing the severity of the disease [5-7] owing to its high immune induction potency [8]. However, some cases of breakthrough infections have been reported [9-11], and it has been pointed out that one of the causes is a decrease in the levels of antibodies against the disease over time [12]. However, booster vaccination has been shown to be effective in preventing the onset of the disease and reducing the risk of severe disease [13-15]. Therefore, we consider it meaningful to assess COVID-19 antibody levels periodically after vaccination and booster shots to prevent such infections. We measured the antibody levels of our medical staff against COVID-19 monthly after COVID-19 vaccination and examined changes in antibody levels after administration of additional vaccination during a one-year period.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

The subject was a 64-year-old male medical staff of our corporation who received the COVID-19 vaccine by Pfizer-BioNTech twice and received an additional vaccine dose by Moderna eight months after the second vaccine dose and was administered COVID-19 antibody testing monthly for a year.

Ethical Principles

The present study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the Seikokai Group Ethics Committee approved the study protocol. Informed consent was obtained from the staff.

Methods

The staff member received two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine by Pfizer-BioNTech between 10 June and 1 July 2021 and was subsequently administered COVID-19 antibody testing over time. Following that, he received an additional booster COVID-19 vaccine by Moderna on 21 February 2022 and was subsequently administered COVID-19 antibody testing over time. Antibody levels were measured monthly: one month after the completion of the second vaccination [16], two months after the second vaccination, and three months after the second vaccination. Subsequently, the fourth, fifth, and sixth measurements were performed every one month. An additional vaccine dose was administered eight months after the second vaccination. The seventh antibody level was measured one month after the additional vaccine dose, and the eighth, ninth, and tenth measurements were performed every one month, respectively. In total, the fluctuation of antibody levels was monitored for a year. Antibody levels were measured by quantification of spike protein-specific IgG antibodies, which have neutralizing activity against the receptor-binding domain of the virus. Abbott SARS-CoV-2 IgG (Abbott Japan, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan; cutoff value: 50 AU/mL) was used to perform this measurement.

Results

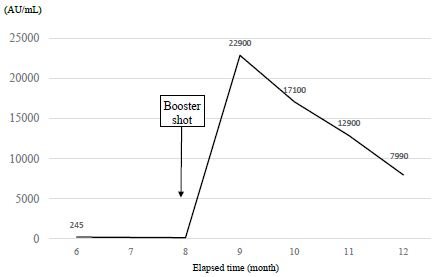

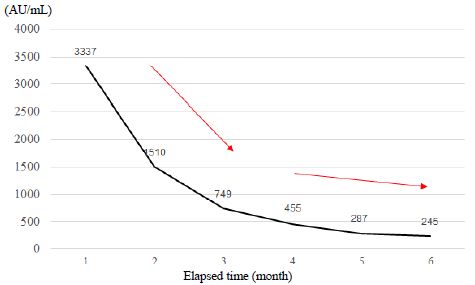

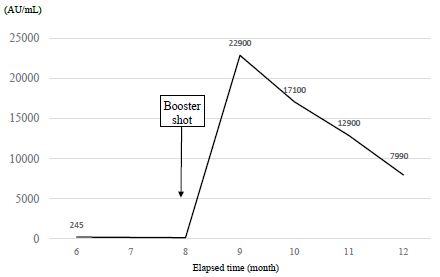

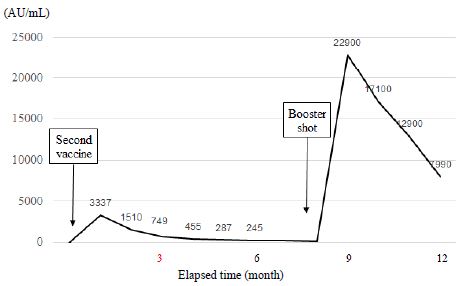

The time course of the antibody levels after two doses of the vaccine for the first 6 months is shown in Figure 1. The antibody level at one month after the second vaccine dose was 3,337 AU/mL, but that at the next month was 1,510 AU/mL, which is a decrease of 55%. The antibody level at three months after the vaccination was 749 AU/mL, a 78% decrease from that at the first measurement. Antibody levels at 4, 5, and 6 months after treatment were 455, 287, and 245 AU/mL, respectively. The decline in antibody levels was relatively slow compared with that in the first three months (Figure 1: arrows). The time course of the antibody levels from six months to 12 months after two doses of the vaccine is shown in Figure 2. After the administration of booster vaccine dose, the antibody level was remarkably increased to 22,900 AU/mL (at 9 months) and declined to 17,100 AU/mL (at 10 months), 12,900 AU/mL (at 11 months), and 7,990 AU/ml (at 12 months). However, the antibody level after the additional vaccine dose was relatively higher than that after the second dose. The total course of vaccination and antibody levels for a year period are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 1: Time course of the antibody levels for six months after administration of a second vaccine dose

Figure 2: Changes in the antibody levels after administered an additional vaccine dose

Figure 3: Total time course of vaccine doses and antibody tests for a-year period

Discussion

How antibody levels change after COVID-19 vaccine dose is now a matter of concern not only for healthcare professionals but also for the general population. In this study, we evaluated the antibody levels of our medical staff following vaccination and booster shot for COVID-19 every month during a one-year period. After two doses of the vaccine, the antibody level at three months decreased by 78% from baseline and at six months, decreased by 93% from baseline. This result indicates that the degree of decrease in antibody levels in the first three months was higher than that in the second three months, and the current results support our previous study [17]. We also demonstrated that after the administration of the booster shot, the antibody levels were remarkably increased and significantly higher than that after the second vaccine dose (Figure 3). Notably, the antibody levels remained high even after several months of the booster shot. Our current data also showed similar results to those of the previous studies [18-21]. It has been thought that the vaccinations increased at the same time as the outbreak of the delta strain that began in May last year from India [22-24], contributing to the convergence [25] of COVID-19 worldwide; however, the subsequent decrease in antibody levels may have contributed to the new omicron strain outbreak. However, the administration of additional doses of the vaccine is considered a significant countermeasure against COVID-19 because it was shown that the antibody levels against the disease increased again after the additional doses and that the severity and mortality rate from COVID-19 were reduced by the additional vaccine doses [26,27]. This remarkable increase in antibody levels after the additional vaccine dose may also contribute to the convergence of the omicron strain. We believe that the current data may help infection measures against COVID-19 for doctor, nurse, and other medical staff.

Study Limitations

The serum sample was obtained from one medical staff, and a large-sample investigation is needed to confirm our current study.

Conclusion

We measured the antibody levels of our medical staff over time after COVID-19 vaccination and examined changes in antibody levels after the administration of the booster vaccination for a year. Although the antibody levels declined with time after vaccination, we showed that the antibody levels significantly increased again after booster vaccination and remained high for several months.

Acknowledgment

The authors deeply indebted Saeki Ishiwata for providing serum samples and technical assistance for this research. The authors also thank to Bio Medical Laboratories Incorporated (BML, Inc.) for valuable support.

The preliminary data of this study was presented at a 4th European Congress on Infectious Diseases via live on 11 November 2022 at Paris, France, and on demand web streaming.

Funding

The authors declare that they have nothing to disclose regarding funding.

Conflict of Interest

The authors state that they have no conflict of interest to declare.

Author Contributions

Ikuma Kasuga conceived the work and designed the study protocol. Yuko Ishii contributed to the data curation and laboratory analysis. Yoshimi Yokoe and Osamu Ohtsubo supervised the project. Ikuma Kasuga contributed to the writing of the original draft, and all authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript version.

References

- Gao Z, Xu Y, Sun C, Wang X, Guo Y, et al. (2021) A systematic review of asymptomatic infections with COVID-19. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 54: 12-16. [crossref]

- Mulligan MJ, Lyke KE, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, et al. (2020) Phase I/II study of COVID-19 RNA vaccine BNT162b1 in adults. Nature 586: 589-593. [crossref]

- Kim JH, Marks F, Clemens JD. Looking beyond COVID-19 vaccine phase 3 trials. (2021) Nat Med 27: 205-211.

- Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, Gostin LO, Larson HJ, et al. (2021) A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med 27: 225-228. [crossref]

- Keech C, Albert G, Cho I, Robertson A, Reed P, et al. (2020) Phase 1-2 trial of a SARS-CoV-2 recombinant spike protein nanoparticle vaccine. N Engl J Med 383: 2320-2332.

- Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, et al. (2020) Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med 383: 2603-2615. [crossref]

- Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, et al. (2021) Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med 384: 403-416.

- Wang Z, Schmidt F, Weisblum Y, Muecksch F, Barnes CO, et al. (2021) mRNA vaccine-elicited antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and circulating variants. Nature 592: 616-622.

- Callaway E (2021) Could new COVID variants undermine vaccines? Labs scramble to find out. Nature 589: 177-178.

- Gupta RK, Topol EJ (2021) COVID-19 vaccine breakthrough infections. Science 374: 1561-1562.

- Hacisuleyman E, Hale C, Saito Y, Blachere NE, Bergh M, et al. (2021) Vaccine breakthrough infections with SARS-CoV-2 variants. N Engl J Med 384: 2212-2218. [crossref]

- Khoury J, Najjar-Debbiny R, Hanna A, Jabbour A, Ahmad YA, et al. (2021) COVID-19 vaccine – Long term immune decline and breakthrough infections. Vaccine 39: 6984-6989. [crossref]

- Bar-On YM, Goldberg Y, Mandel M, Bodenheimer O, Freedman L, et al. (2021) Protection of BNT162b2 vaccine booster against Covid-19 in Israel. N Engl J Med 385: 1393-1400.

- Accorsi EK, Britton A, Fleming-Dutra KE, Smith ZR, Shang N, et al. (2022) Association between 3 doses of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine and symptomatic infection caused by the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron and Delta variants. JAMA 327: 639-651. [crossref]

- Garcia-Beltran WF, St Denis KJ, Hoelzemer A, Lam EC, Nitido AD, et al. (2022) mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine boosters induce neutralizing immunity against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. Cell 185: 457-466. [crossref]

- Zhou W, Xu X, Chang Z, Wang H, Zhong X, et al. (2021) The dynamic changes of serum IgM and IgG against SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. J Med Virol 93: 924-933. [crossref]

- Kasuga I, Gamo S, Yokoe Y, Sugiyama T, Tokura M, et al. (2022) Antibody levels over time against novel coronavirus and incidence of adverse reaction after vaccination. Health Evaluation and Promotion 49: 462-469.

- Belik M, Jalkanen P, Lundberg R, Reinholm A, Laine L, et al. (2022) Comparative analysis of COVID-19 vaccine responses and third booster dose-induced neutralizing antibodies against Delta and Omicron variants. Nat Commun 13.

- Zeng G, Wu Q, Pan H, Li M, Yang J, et al. (2022) Immunogenicity and safety of a third dose of CoronaVac, and immune persistence of a two-dose schedule, in healthy adults: interim results from two single-centre, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 clinical trials. Lancet Infect Dis 22: 483-495. [crossref]

- Petrelli F, Luciani A, Borgonovo K, Ghilardi M, Parati MC, et al. (2022) Third dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: A systemic review of 30 published studies. J Med Virol 94: 2837-2844. [crossref]

- Muik A, Lui BG, Wallisch A-K, Bacher M, Mühl J, et al. (2022) Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron by BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine-elicited human sera. Science 375: 678-680. [crossref]

- Vaidyanathan G (2021) Coronavirus variants are spreading in India – what scientists know so far. Nature 593: 321-322. [crossref]

- Callaway E (2021) Delta coronavirus variant: scientists brace for impact. Nature 595: 17-18. [crossref]

- Planas D, Veyer D, Baidaliuk A, Staropoli I, Guivel-Benhassine F, et al. (2021) Reduced sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 variant Delta to antibody neutralization. Nature 596: 276-280.

- Bernal JL, Andrews N, Gower C, Gallagher E, Simmons R, et al. (2021) Effectiveness of Covid-19 vaccines against the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant. N Engl J Med 385: 585-594. [crossref]

- Barda N, Dagan N, Cohen C, Hernán MA, Lipsitch M, et al. (2021) Effectiveness of a third dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine for preventing severe outcomes in Israel: an observational study. Lancet 398: 2093-2100.

- Arbel R, Hammerman A, Sergienko R, Friger M, Peretz A, et al. (2021) BNT162b2 vaccine booster and mortality due to Covid-19. N Engl J Med 385: 2413-2420. [crossref]

Demographic and Clinicopathological Evaluation of Colorectal Adenocarcinoma in Bangladesh at a Tertiary Level Hospital

DOI: 10.31038/CST.2023811

Abstract

Background and aim: Colorectal Cancer (CRC) is the third leading cause of global cancer death in humans and its incidence is gradually rising in developing nations including Bangladesh. The study was carried out to unveil the demographic and clinicopathological profile of CRC cases in Bangladeshi patients.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted among purposively selected 50 patients irrespective of age and sex with histologically proven colorectal cancer at a tertiary level hospital for a period of 2 years. Large bowel resection specimens of CRC made the samples. Demographic and clinical information were recorded in a pre-tested, structured case record. Relevant macroscopic and microscopic features of tumors were recorded during gross and microscopic examinations of the specimen.

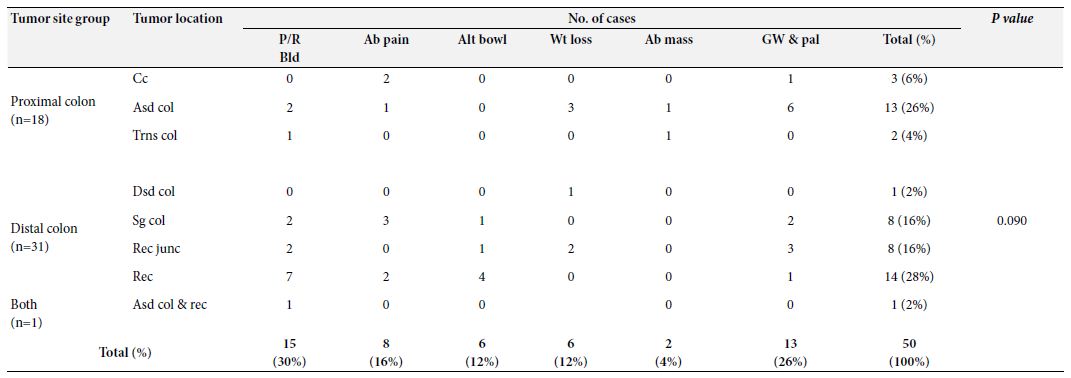

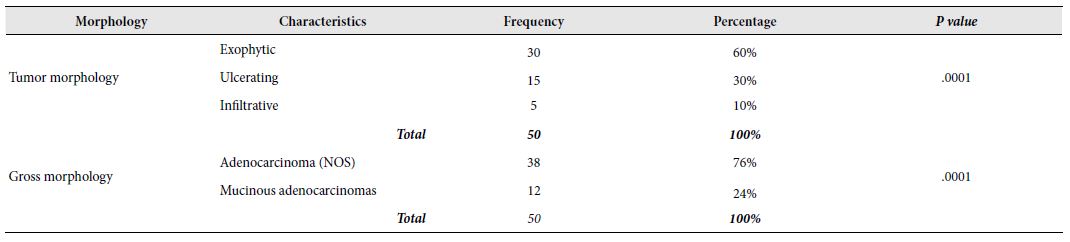

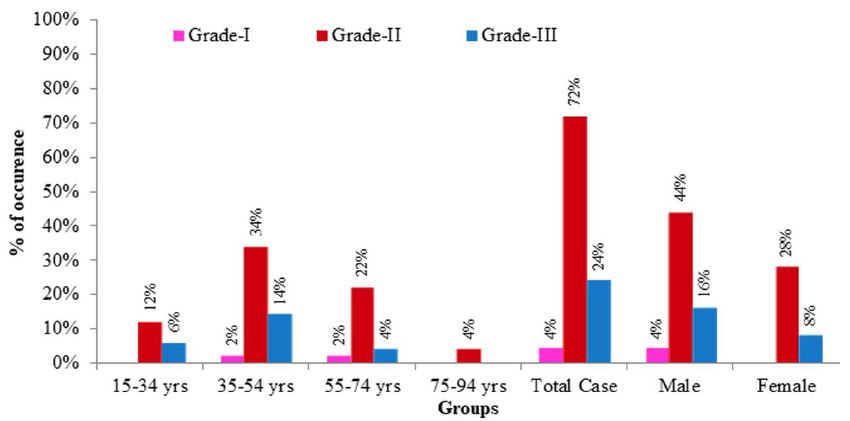

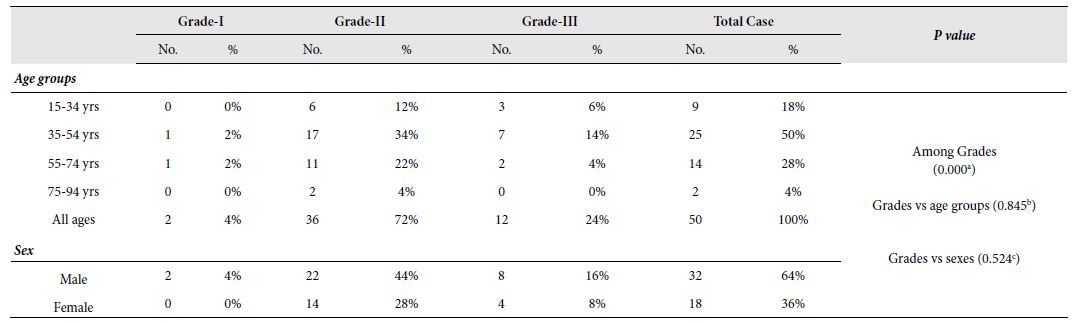

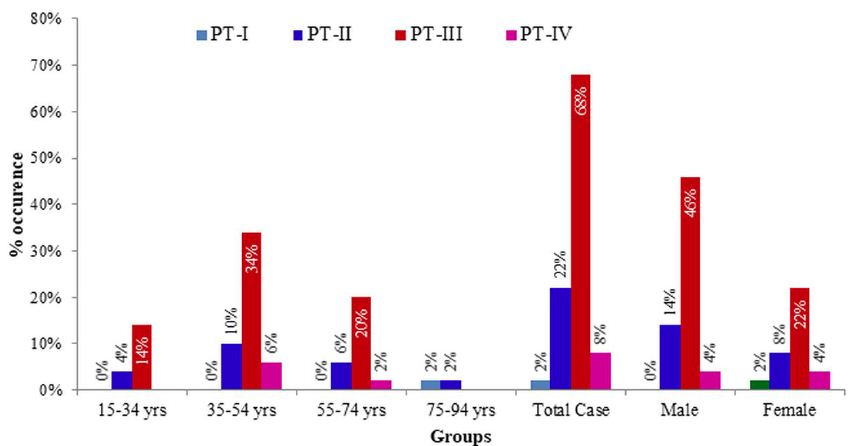

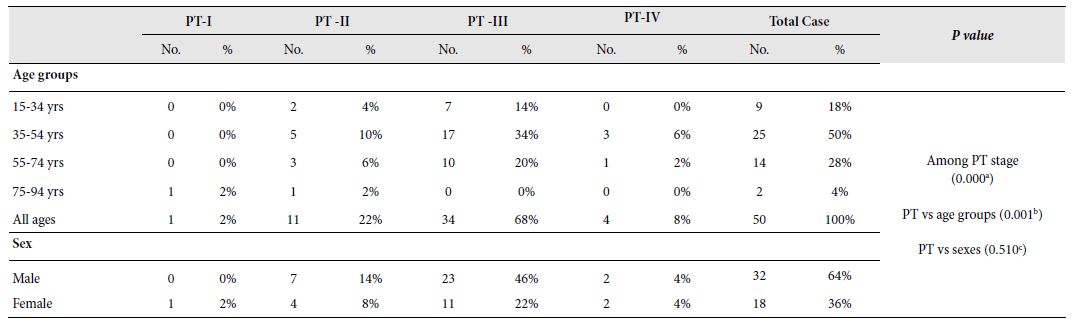

Results: Mean age of the CRC patients was 48.60±14.6 years. Adult active males (35-54 years old) were significantly affected by CRCs (p=0.0001). Per rectal bleeding (38.7%) and generalized weakness and pallor (38.98%) were the most frequent findings in distal and proximal CRCs, respectively. Adenocarcinoma NOS was the most commonly observed histologic type. Occurrence of CRC and tumour grades were significantly (p=0.0001) related where Grade-II and Grade-III tumour occurred in 72% and 24% of cases, respectively. Majority of the cases were presented at stage pT3 (68%) and pN0 (48%). Tumors in adult active age showed a higher tendency to be presented at advanced stages.

Conclusions: Bangladeshi adult active males of 35-54 years old were predominantly affected by a locally advanced stage of CRC. Routine screening programs are proposed for early detection and treatment of the cases.

Keywords

Colon cancer; Bangladeshi patients; Clinical features; Demographic characteristics; Intestinal tumor

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is one of the most common cancers globally. It is the second most common malignancy among women and the third most common malignancy in men [1]. The global burden of colorectal cancer is expected to increase by 60% by 2030. Its incidence shows a 10-fold variation across the world [2]. The prevalence of colorectal cancer is lower in Asia than in Western countries. But the incidence has been alarmingly increasing in countries of the Asia-Pacific region during the last two decades due to the westernization of lifestyles [3]. In Bangladesh, 5-year prevalence of colon and rectal cancer are 3.28 and 3.1 per 100,000 population, respectively [4]. There are variations in risk factors, mode of disease presentation, sub-site distribution, tumor morphology, grade and stage at presentation. These tumors grow insidiously and remain undetected for long periods remaining potentially curable, premalignant lesions over several years. Therefore, screening procedures provide a unique opportunity for cancer prevention [5]. However, in the long run, the tumor cells metastasize to lymph nodes and in the other organs. The treatment, prognosis and survival rate largely depend on the stage of disease at diagnosis.

The development of both familial and sporadic colorectal cancers can be influenced by genetic factors [6]. Age is another major risk factor for sporadic CRC. The diagnosis is rare before the age of 40 years. The incidence starts to increase significantly between 40 to 50 years and the age-specific incidence rates raise in each succeeding decade thereafter [7]. Although patients over 50 years of age represent 90% of newly diagnosed cases [8], the trend is changing with the increasing incidence among the younger population who present in a more advanced stage [9]. In recent years, tumor location has also been suggested to be a valuable predictor, which has added to the difficulty of discussing its clinicopathological features and outcomes [10]. The majority of colorectal cancers belong to classical adenocarcinomas, with several histological variants associated with specific molecular characteristics [11,12]. Understanding these features could guide the proper management and prognosis of the patient. But unfortunately, there is a scarcity of data regarding the demographic and clinicopathological patterns of colorectal cancers in Bangladeshi patients. Therefore, the present study was undertaken to understand the demographic and clinicopathological profiles of patients with colorectal carcinoma in Bangladesh.

Methods

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the local Ethics Committee (Institutional Review Board) at Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BSMMU) and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Study Design, Period and Sample

This cross-sectional, descriptive, hospital based, study was conducted in the Department of Pathology, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BSMMU), Dhaka, Bangladesh during the period of March 2019 to February 2021. Large bowel resection specimen histologically diagnosed as adenocarcinoma at the department of Pathology, BSMMU were included in this study. A total of 50 primary colorectal carcinoma cases irrespective of ages and sexes were included in the study. Clinically suspected colorectal carcinoma subsequently proved to be non-epithelial tumors of the colon were excluded from this study. Patients’ attendants were interviewed for demographic and clinical information, which were recorded in a performed questionnaire.

Gross and Microscopic Evaluation of Samples

During gross examination tumor site and macroscopic features of tumors were noted. Splenic flexure was taken as demarcating point of proximal and distal lesions. After that representative tissue blocks were submitted for routine processing and paraffin embedding. Standard protocol was maintained during tissue processing and staining. Microscopic examination of tissue sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin was carried out and relevant points were recorded. The tumors were classified following World Health Organization classification of tumor and grading of tumor was done by using AJCC specified four-tiered grading system. Staging was performed following TNM Classification of Colorectal Carcinoma American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC).

Statistical Analysis

Data was entered in MS Excel and analyzed by using SPSS software version 21. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages and analyzed using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were expressed as mean or median and analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test. Demographic factors and clinical characteristics were summarized with percentages for categorical variables and median for continuous variables.

Results

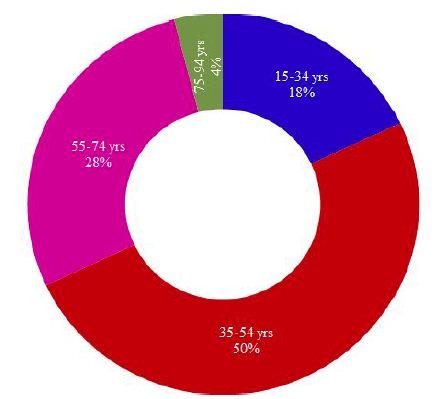

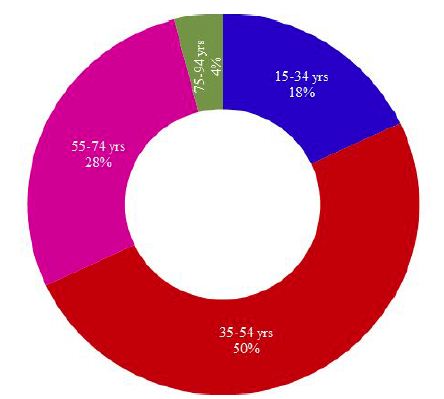

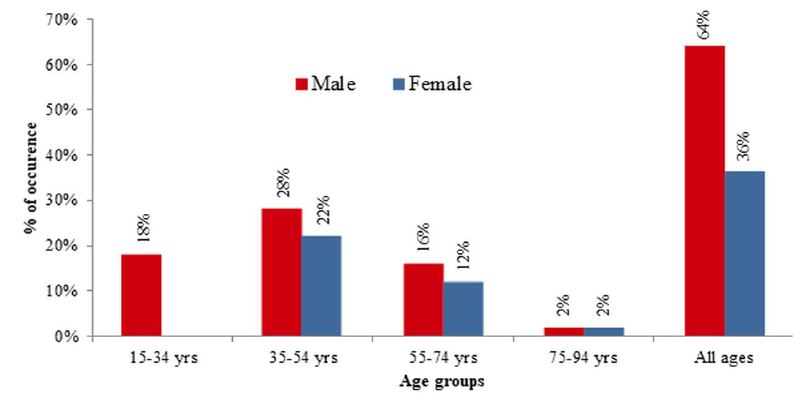

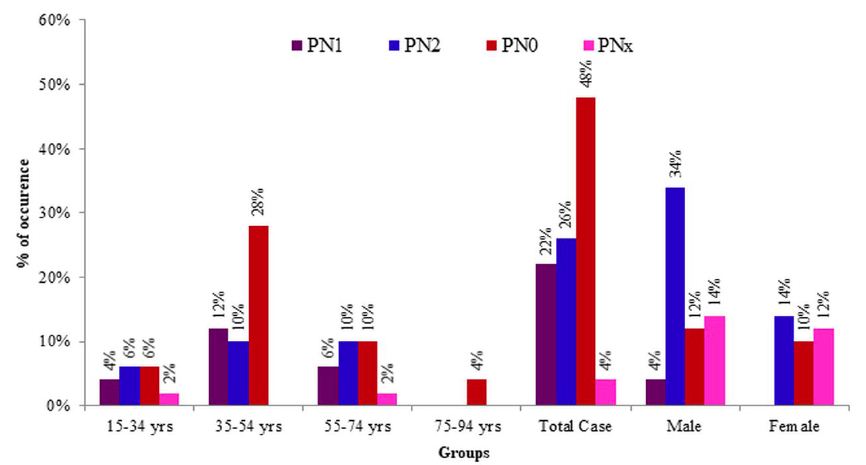

A total of 50 patients with CRC were enrolled in this study. Age of the study population varied from 19-85 years with a mean of 48.60±14.6 (SD) years. All the 50 cases were categorized into four age groups where samples from patients belonging to 15-34 years, 35-54 years, 55-74 years and 75-94 years were considered as young, adult, elderly and old age groups, respectively. Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of CRC cases in different age groups.

Figure 1: Distribution of CRC cases in different age groups of Bangladeshi patients

As shown in Figure 1; half (50%) of the CRC cases belonged to adult active age group (35-54 years), followed by 28% cases in elderly (55-74 years), 18% cases in young (15-34 years) and 4% cases in old age group (75-94 years). A chi-square test of independence was performed to examine the relationship between age groups and the frequency of occurrence of CRCs. The relation between these variables was significant, X2 (3, N=50)=22.48, p=.0001 at α=0.05. The adult active age group (35-54 years) was more likely to be affected by colorectal carcinoma than the other groups.