Abstract

We introduce the science of Mind Genomics to the study of large sets of messages, specifically those found on the Internet and dealing with arthritis. Through experimental design, we create small sets of 25 test combinations, comprising 20 messages in different combinations of 2–5 elements. We use the experimental design to estimate the contribution of each message to interest. We then extend the estimated contributions to elements that were untested. This approach enables us to assess how 170 different messages about arthritis appeal to the general public, and reveals four new emergent mind-sets, responding to different types of messages. We then introduce a tool, the Person Viewpoint Identifier (PVI), allowing a medical professional to assign a new person to the appropriate mind-set, setting up a knowledge base for more effective messaging for health-promotion, and more person-compatible treatment.

Introduction

Arthritis causes persistent pain, distress, and disability [1, 2]. The symptoms of pain, disability, and depression appear to increase with age, and their prevalence may be underestimated [3]. Arthritis patients of all ages complain of five physical symptoms comprising pain, stiffness, fatigue, joint cracking, and swelling, respectively. These symptoms negatively affecting their decisions about performing functional routine activities, their mood and their well-being [4]. Arthritis is becoming more prevalent among the young as well. Younger arthritis patients complained about physical “slowing down” and cognitive and emotional changes [5]. Arthritis patients report psychological challenges such as depression, helplessness, and anxiety, conditions which significantly impacting their life quality [5, 6].

The power of arthritis, a long-term condition, affecting patients’ physical health status, patients’ mental well-being, and increasing public and private healthcare expenditures, makes it important to improve self-management of arthritis [7]. Yet, self-management is complex, requiring both medical knowledge and patient-centered knowledge [8]. Self-management of one’s illness requires patient trust in physicians [9]. What is emerging is the need for the patient to understand himself or herself at a deeper emotional and intellectual level. This knowledge will reveal what is important. The knowledge should create an empowered patient who is a partner together with the doctor through an ongoing process, effectively maintaining the mental and physical welfare of the individual [10].

Arthritis patients reported that physicians attributed their symptoms to age, and all-too-often made no recommendations to manage symptoms, actions which lead to patient frustration, uncertainty, and loss of trust in the physicians [4]. Loss of trust leads to lack of adherence [11]. Reports suggests that quite often, patients are not given the relevant and necessary information on support, resources, and ‘tips’ about how to self-manage their illness [5, 12]. Moreover, patient experiences, perceptions, and expectations in arthritis are not understandable [4, 13]. Insights from patients’ perspective is required but has been neglected [14].

The complicated nature of arthritis means that the patient must be ‘taught’ a variety of different types of information. Some of the factors in self-management of chronic illness may be related to lifestyle (e.g., diet, sleep). Other information may be related to activities, exercise programs, occupational therapy, and so forth. A literature search indicates that patients were unaware of advice on exercise or weight control, and did not access the available services in a productive manner [15, 16]. Furthermore, only half of the patients received physiotherapy, although many expected such physiotherapy to be easily available [17]. None of the patients were aware of occupational therapy and expected their care to be proactive rather than reactive [17].

Arthritis patients perceived arthritis as a low priority of health care systems and complained about the scarcity of specialists dealing with arthritis. They also expressed a need to talk for a longer time with physicians [16, 17]. Finally, patients expressed anxiety because they perceived a lack of good and understandable information by which they could make judgments [17]. Patients claimed that they need more information to allow them higher control resulting in self-management of their arthritis [9]. Patients wanted tailored information about the disease, advantages, disadvantages of treatment and medication without having to specifically request it [18–21]. This lack of information confirms findings of previous studies [22–24].

The Internet presents the largest publicly available source of messaging to arthritis sufferers. Our study tests what messages arthritis suffers find most compelling, and how to drive the right communication to the arthritis sufferer, based on mind-set. Appropriate messages, correctly targeted, may promote well-being and trust in physicians leading to higher self-management of illness.

This paper focuses on perceptions and expectations of arthritis patients, based upon reactions to messages about arthritis ‘scraped from the Internet. Understanding patient perception and expectations is imperative for health services. Such information promoted better communication messages and services. The result is that the patient receives the necessary information, and the health-care system empowers the patient to participate in the self-management of arthritis [17].

Asking Versus Experimenting

Asking questions of respondents about their preferences and beliefs has been a tradition in research since the field began in earnest in the 1950’s. A great deal of our knowledge of what people want in fast-moving goods and services including in health services and in medicine, has emerged from the analysis of often agonizing-detailed studies. Indeed, one might use the metaphor of ‘warehouses filled with data, ’ and not be very off the mark.

Two newer approaches have emerged to understand the rules of choice. The former, tracking behavior, is an increasingly large proportion of consumer research as of this writing (2019), with the field replete with good data, but also replete with consumer and legal reactions against the suggested invasion of privacy. Indeed, tracking people’s behavior and the ownership of such data is an increasingly contentious area world-wide, leading to many lawsuits, and in the case of Europe, leading to regulations about privacy.

The second new approach is experimentation, made very easy on the Internet. The notion is that one can understand the structure of consumer expectations and preferences through experiments. These experiments, motivated in part by the growth of the field called behavioral economics, suggests that we can learn a great deal by giving respondents concepts or vignettes and asking them to react to these concepts. By systematically varying the concepts (the test stimuli), and measuring the responses, it becomes possible to generate patterns, relating the responses to the antecedent stimuli.

Dealing with large numbers of messages through modeling and data imputation

One of the key issues for studying a large category of messaging, such as arthritis, is the richness of the information available. As electronic communication increases through the web, there emerges an extraordinarily large number of websites devoted to topics of general concern, and within those websites many messages. How does one run an experiment to understand which messages accord and which messages do not accord and finally when there can be upwards of 100 messages?

One simple way presents single messages to respondents, instructing them to rate the message, and of course rotating the order of the messages in order to reduce the fatigue and the boredom. The respondent may be instructed to rate only a subset of the messages.

The aforementioned approach, presenting single items, works when the messages tell a story, paint a word picture, and have ecological validity. In other words, testing single items, single ideas, works best when the messages make sense. The messages must comprise short stories within them. This requirement is met by many messages, but not met by messages which may be tag lines or messages which may be pictures support the general story but in themselves not relevant.

Moskowitz & Martin [25] presented the original science of Mind Genomics in a paper, where they introduced the notion of presenting a respondent with a set of systematically varied concepts, estimating the coefficients from models created after relating the elements or messages in the concept to the response, and then, most important, estimating the coefficients of elements untested by that respondent. In other words, the approach enabled the researcher to estimate the impact of a message, and use a form of numerical analysis, data imputation, to estimate the value or coefficient of untested elements. The reader is referred to that paper for full details. Below is a simplified explanation:

- Each of the test elements is profiled on a set of three non-evaluative bipolar scales (semantic differential scales)

- Each test element has a set of eight closest neighbors, defined by the Euclidean distance between the pairs of elements. The Euclidean distance is defined in the normal way, using the scales on which the elements were profiled

- Each respondent evaluates two sets of 20 elements, combined into 50 vignettes, according to an underlying experimental design.

- The ratings are transformed, so that a rating of 1–6 is transformed to 0, and a rating of 7–9 is transformed to 100. A small random number (<10–5) is added to the rating. This small number does not affect the results, but ensures that the regression analysis below ‘runs, ’ even in those situations where a respondent confines all ratings to 1–6 (transformed to 0), or the respondent confines all ratings to 7–9 (transformed 100.) The small random number ensures variation in the dependent variable, necessary for the regression not to ‘crash.’

- The ratings are deconstructed into the part-worth contribution of the 40 elements using OLS (ordinary least-squares) regression. The regression generates coefficients.

- At this first step, those elements not tested are assigned a value of 0. When an element was tested, its value is the coefficient estimated in Step 5.

- Starting from the first element to the element (including text and visual elements), the algorithm goes through the set of elements. The algorithm looks at each element, one element at a time. When the element had been tested by the respondent, then the element coefficient is unchanged. When the element had not been tested by the respondent, the element coefficient (starting with 0 at the beginning) is replaced by the average coefficient of the eight nearest elements defined in Step 2, above.

- The algorithm goes through the respondent’s data until it reaches a point when the coefficient of untested elements no longer materially changes (<.001 change). The process stops when all untested elements stop changing, and the coefficients have stabilized to their estimated values.

- The coefficients are then averaged.

- For each respondent, the process provides a conservative estimate of the coefficients of the elements, tested and untested.

The Arthritis Study

The objective of this study was to understand what specific messages from a set of 170, taken from web-pages, were most appealing to respondents in the general population of those defining themselves as suffering from arthritis. The messages were ‘scraped’ from sites featuring discussions of arthritis. The messages were taken from then-current websites, during the early years of the 21st century. The fact that the elements are more than a decade old is irrelevant to the study because the focus is on the types of messages which interest consumers. The web-sites are simply sources of messages, with such messages crafted by those who are involved with arthritis. The websites are transient, changed often, and thus simply a momentary embodiment of messages and pictures which the website owner believes will educate, convince, and even on occasion ‘sell’ a product.

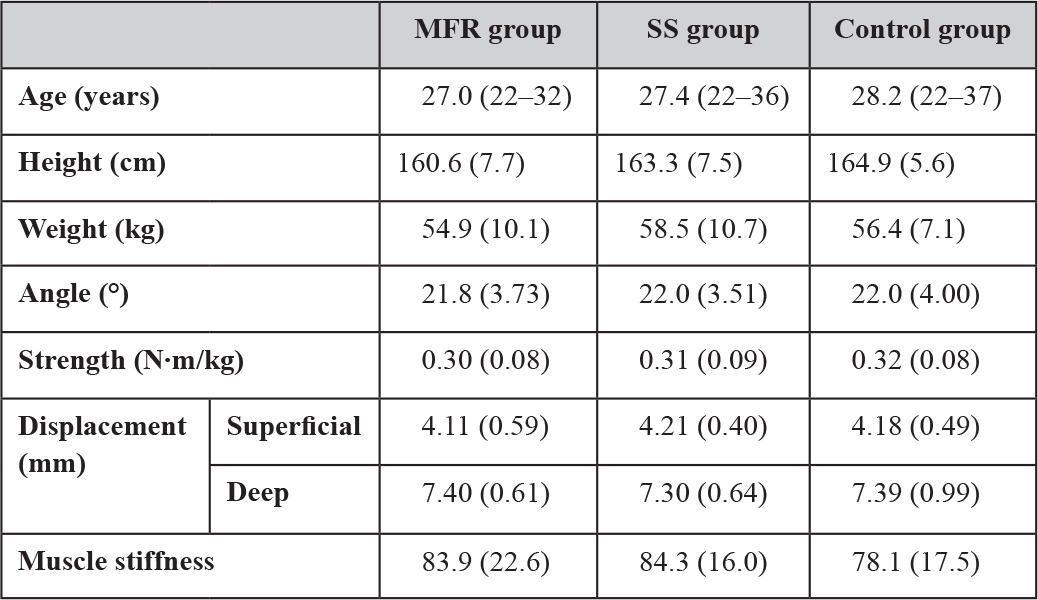

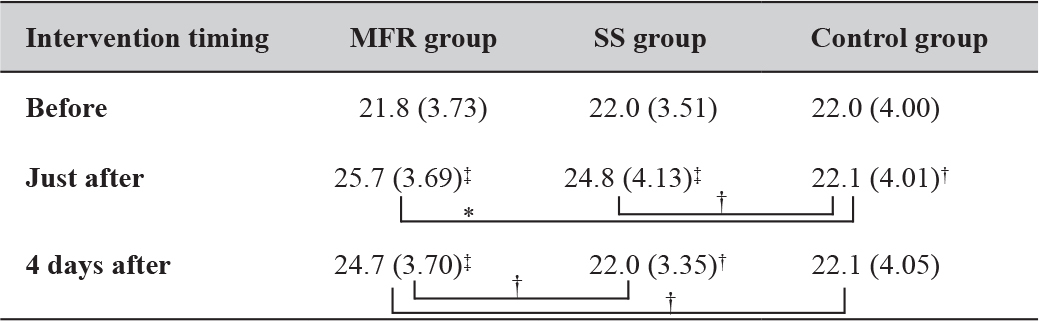

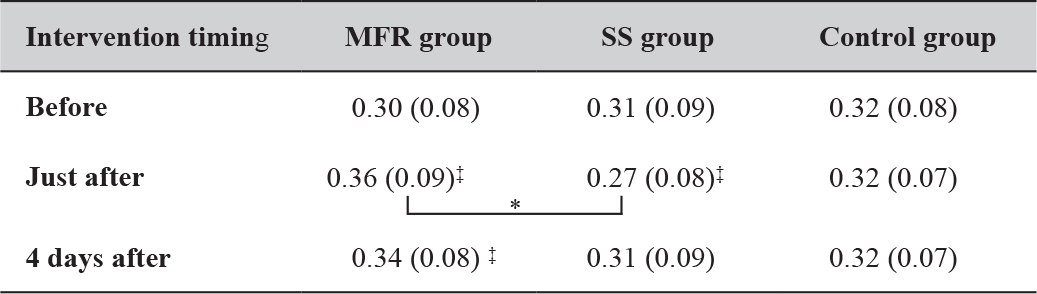

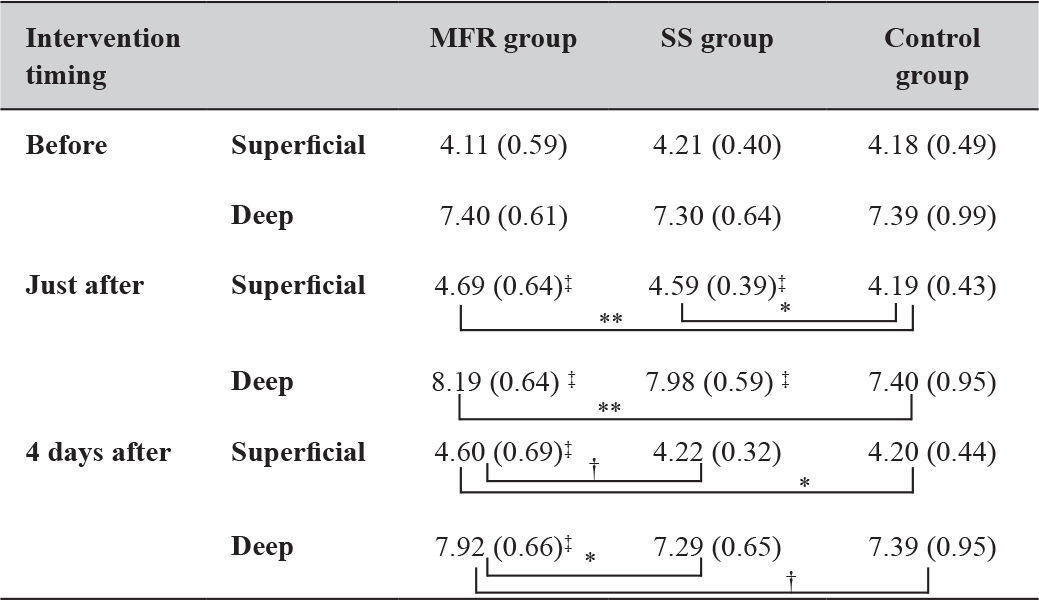

Table 1 show 10 of the 11 websites that were ‘scraped’ to provide the set of 151 text elements and 19 visual elements. (The 11th website was simply text, and from a user-group.) The messages were slightly edited to make them shorter, and easier to read. Every effort was made to keep the original sense of the message

Table 1. The ten websites and a representative element from each website after the slight text editing

|

Website |

Example of message ‘scraped’ |

|

|

1 |

Contains a Glossary of terms used in rheumatic diseases |

|

|

2 |

The path to a healthy lifestyle |

|

|

3 |

Ask our fitness and nutrition expert any questions you may have |

|

|

4 |

Ask our experts any question at the oldest & largest free Q&A service on the Internet |

|

|

5 |

Contains information about diagnosis and treatments |

|

|

6 |

These guides will help you find information fast |

|

|

7 |

Order free brochures or buy an exercise tape in the Arthritis Store |

|

|

8 |

We recommend that before you start any exercise program, it is important that your physician examines you to see which types of exercise would be best for you |

|

|

9 |

Arthritis Advocacy Priorities – Read about the issues |

|

|

10 |

Browse through the latest books and newsletters |

In order to estimate the coefficients of elements untested by each respondent, a small group of five respondents, none of whom would participate in the large study, profiled each of the 170 elements, text and pictures on eight bipolar scales. This exercise allowed us to identify the eight closest neighbors of each element, using the eight bipolar scales (profiling) as dimensions. The use of eight bipolar scales and the eight closest neighbors is simply happenstance, and not a deliberate conjunction of scales and distance.

Table 2 shows an example of pairs of elements which are most separated on three of the eight scales. For example, for the bipolar scale ‘beginner versus experienced, ’ the lowest rating on the bipolar scale (3.8) is ‘Your personalized program can help you learn how to make informed decisions about your treatment options.’ In contrast, on the same scale, the highest rating is 6.8. ‘We recommend that before you start any exercise program, it is important that your physician examines you to see which types of exercise would be best for you.’

Table 2. The highest and lowest text elements on three of the eight bipolar semantic scales. Each element was profiled on all eight scales.

|

1-Beginner Vs 9-Experienced |

|

|

Your personalized program can help you learn how to make informed decisions about your treatment options |

3.8 |

|

We recommend that before you start any exercise program, it is important that your physician examines you to see which types of exercise would be best for you |

6.8 |

|

1-Less Vs 9-More Active |

|

|

Find information on your daily calcium need to keep your bones healthy |

3.7 |

|

Read our Questions and Answers about arthritis pain |

7.8 |

|

1-Occasional Versus 9-Chronic |

|

|

Print out your meal plan and follow it to a new you…recipes and a shopping list are included |

4.2 |

|

Learn your pain medicine risk profile |

7.8 |

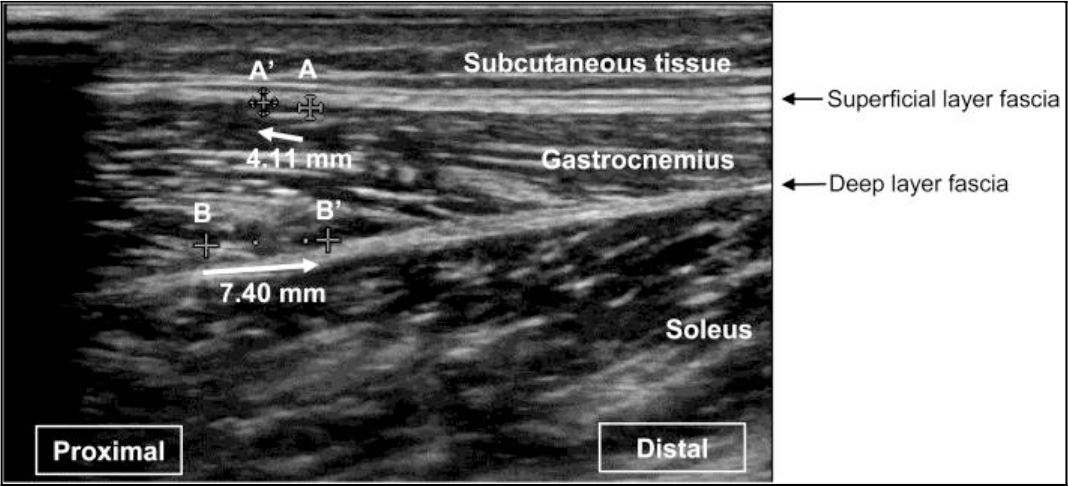

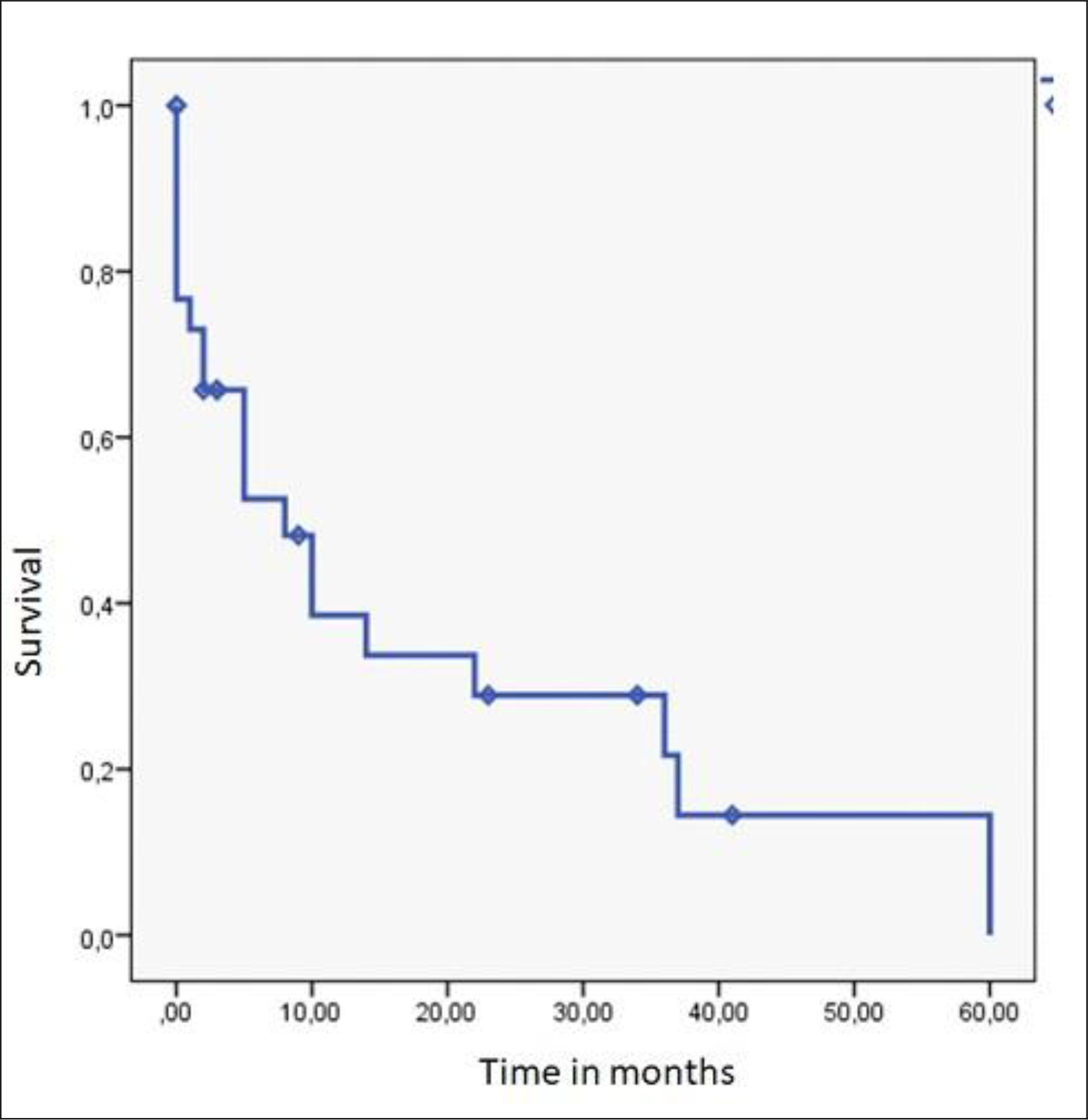

Although the up-front semantic profiling was done as a preparatory step to estimate the coefficients of untested elements, a second use of the semantic profiling quickly emerged. One could get a ‘sense’ of the nature of the various websites by plotting the distribution of scores for each website, on each bipolar scale. Figure 1 gives a sense of how the various websites focus on one tonality (beginner vs experienced) in their messaging.

Figure 1. How the text elements score on the semantic differential scale of ‘for beginner vs for experienced’. Each website presents a variety of different messages

Measures

Silos, Elements and Experimentally Designed Vignettes

The elements were classified into silos, or groups of related elements. By related we mean that the elements in a group shared something in common, and if put together could contradict each other. The structure of silo and element is a bookkeeping tool, one which facilitates critical thinking. The act of putting elements into silos based upon meaning forces the researcher to think more deeply about the structure of the information that is being communicated. Table 3 presents two examples from each silo. The actual sorting of elements into silo is a subjective matter. From a statistical point of view, the assignment of elements to silos has only a minimal effect on the analysis of the results later, through OLS (ordinary least-squares) regression.

Table 3. The 10 silos, and examples of two elements from each silo

|

AD – Organization |

AD01 |

A portion of all proceeds will benefit the Arthritis Foundation |

|

AD – Organization |

AD09 |

Fight for more research funding, insurance coverage for medications and the rights of people with arthritis |

|

CM Communication |

CM01 |

Read ‘A Day in My Life’…stories are submitted by Community Members, and are first-person accounts of what it is like to live with a disease or condition |

|

CM Communication |

CM22 |

The message board is a great way for you to exchange ideas, thoughts, and express yourself |

|

EB Self-manage |

EB01 |

Manage your arthritis and improve your life |

|

EB Self-manage |

EB11 |

Learn ways to prevent injury-related arthritis … prompt treatment can avert serious damage |

|

EX Experts |

EX01 |

Ask our experts any question at the oldest & largest free Q&A service on the Internet |

|

EX Experts |

EX09 |

A site produced and supervised by Board Certified Rheumatologists, your specialists in Arthritis and Osteoporosis |

|

GI General information |

GI01 |

View our online checklist on how to monitor medication use for seniors |

|

GI General Information |

GI27 |

Up to date research on the aches and pains of arthritis and the effective homeopathic medicines |

|

NE Nutrition |

NE01 |

Eating a healthy, balanced diet is important for everyone, but particularly for people with arthritis |

|

NE Nutrition |

NE17 |

Find information on your daily calcium need to keep your bones healthy |

|

PR Privacy |

PR01 |

Learn more about the new ‘Speaking of Pain’ program, and find out how you can request a free brochure |

|

PR Privacy |

PR12 |

We will never share your personal information with any external organization without your consent |

|

RS Resource Info |

RS01 |

Click here for comprehensive information about your health |

|

RS Resource Info |

RS17 |

The Manual of Medical Information transforms the language of the professionals’ version into commonly used English |

|

SH ShoppingHH |

SH01 |

Buy all your arthritis-care products here in the online store. Just click on a product link to browse hundreds of items |

|

SH Shopping |

SH06 |

Refill your prescriptions, find drug information and check drug interactions at the online pharmacy |

|

WF Wellness Fitness |

WF01 |

Take three or more health quizzes and enter to win a free tee-shirt |

|

WF Wellness Fitness |

WF18 |

Your personalized program can help you learn how to start and maintain a fitness program |

Each respondent evaluated two sets of 25 vignettes each, with each set comprising 20 elements combined into the 25 vignettes. A vignette comprised 2–5 elements, combined according to an experimental design (see Table 4 for a schematic for one respondent, and concepts or vignettes 1–6 of 25 vignettes created by design for that respondent.)

Table 4. Schematic of concepts (vignettes) for a respondent. The vignettes are created from a randomized four silos out of the full set of silos and elements. A ‘0’ means that the silo is absent from the vignette. A 1–4 means that one of four elements from the silo is present in the vignette.

|

Category |

A |

B |

C |

D |

|

|

Concept |

1 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

|

Concept |

2 |

4 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

|

Concept |

3 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

3 |

|

Concept |

4 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

|

Concept |

5 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

|

Concept |

6 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

We can think of the design as a ‘menu’ which ensures that only one element from a silo could appear in a single vignette. The 20 different elements per set come to at most 40 different elements seen by a respondent. By design, within a vignette the elements are statistically independent of each other. Generally, when two or more designs are combined, as in the current study, the respondent sees a set of elements which end up being statistically independent. Statistical independence will enable the ratings to be related to the presence/absence of the underlying elements forming the vignette. In turn, the numerical analysis, imputation of the value of missing elements, will be made possible by the computational algorithm specified above, specifically Steps 5–10.

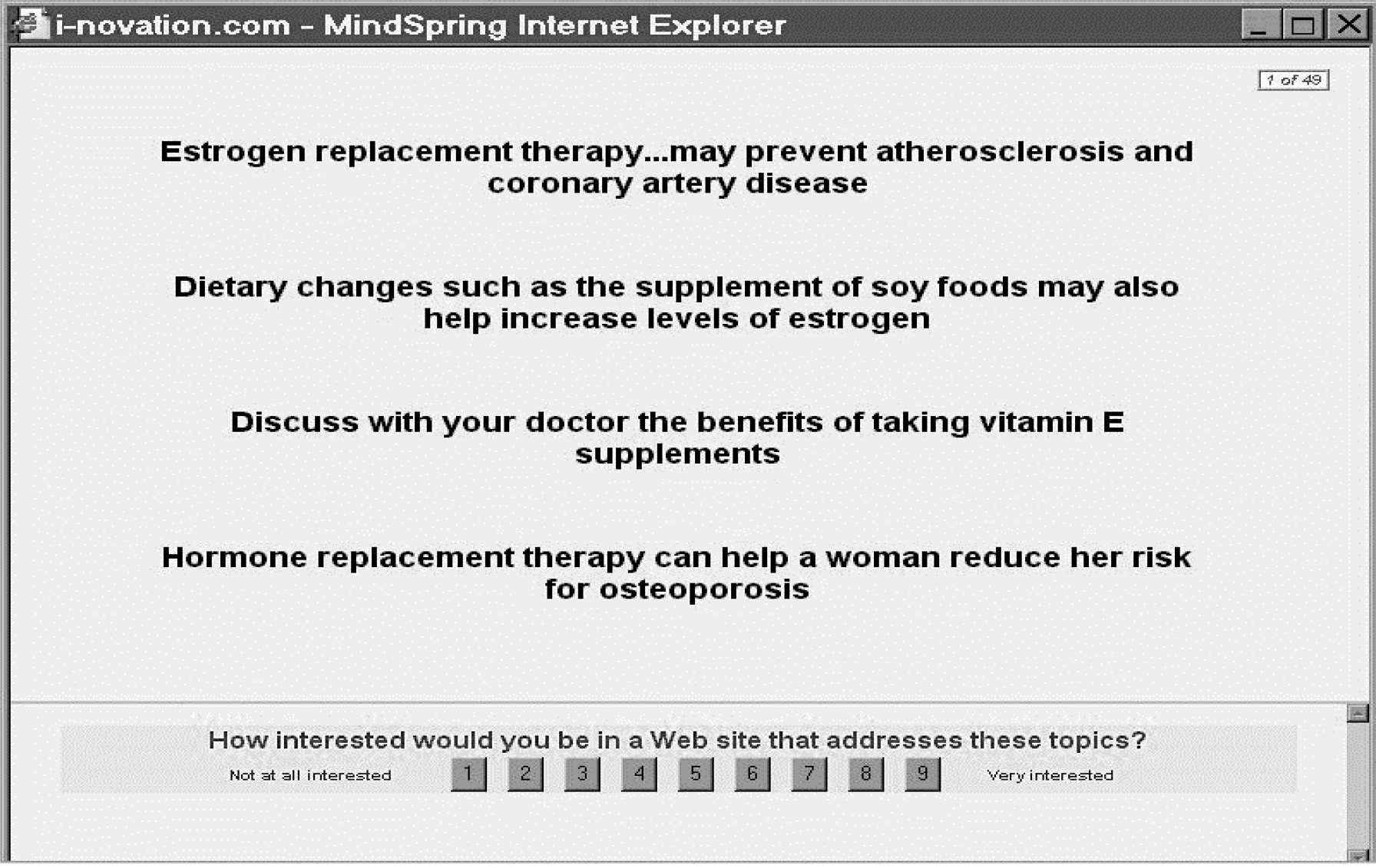

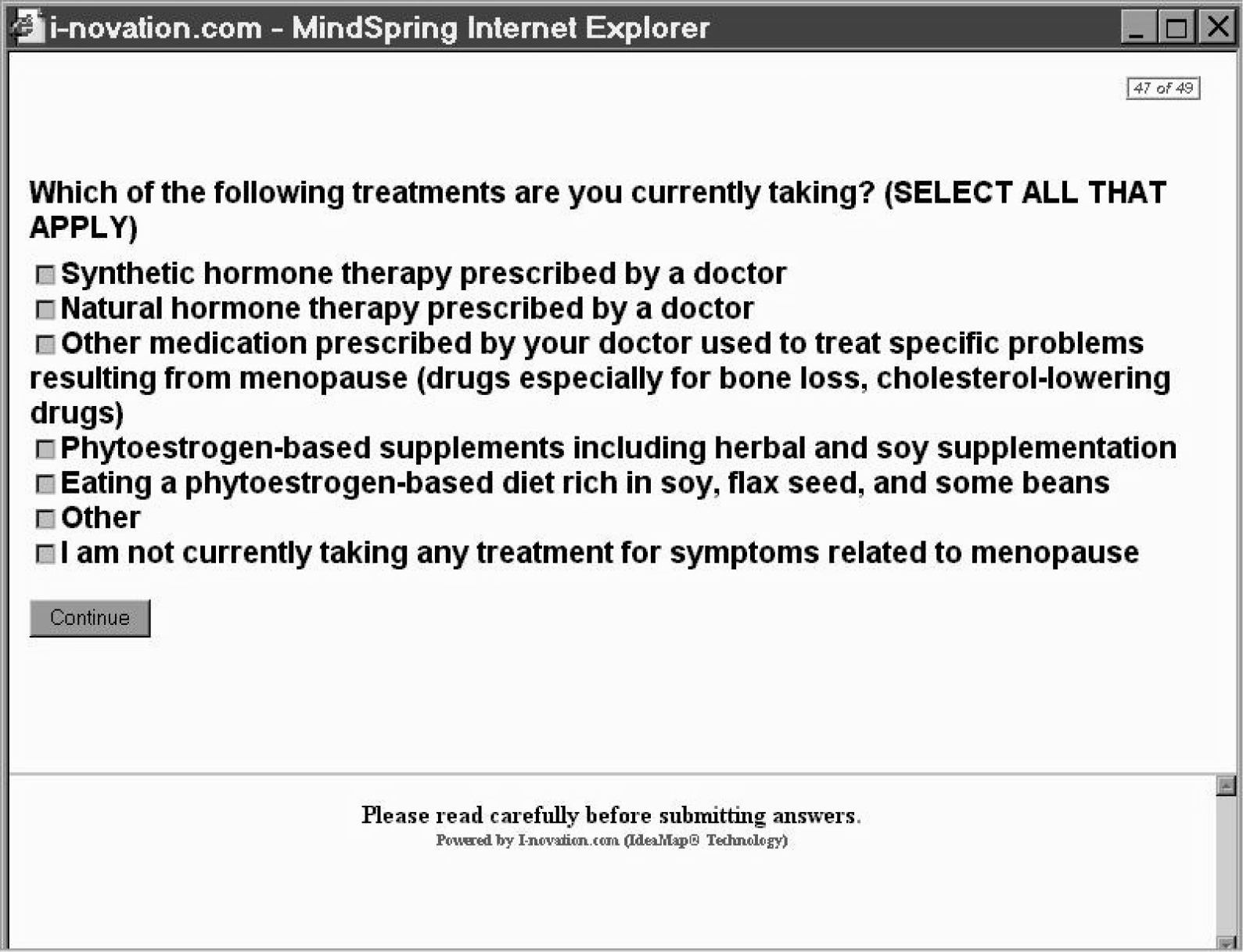

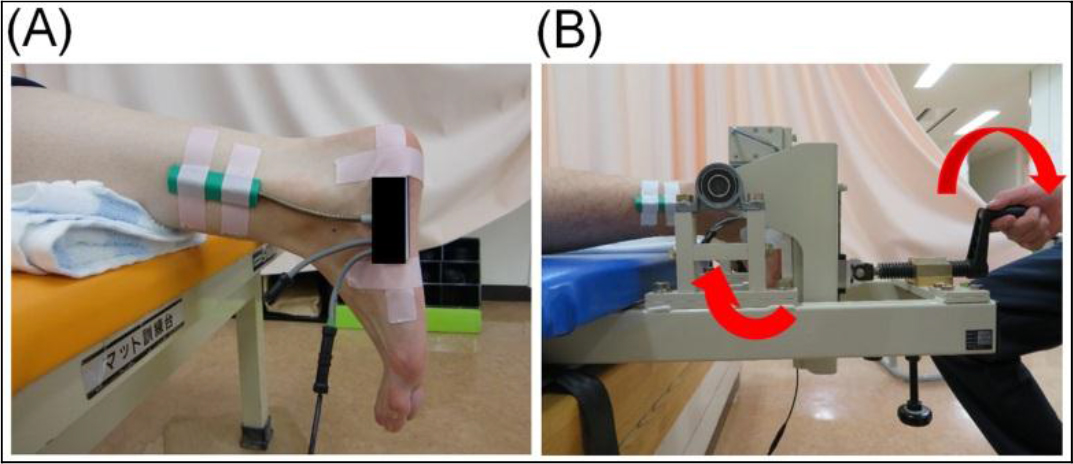

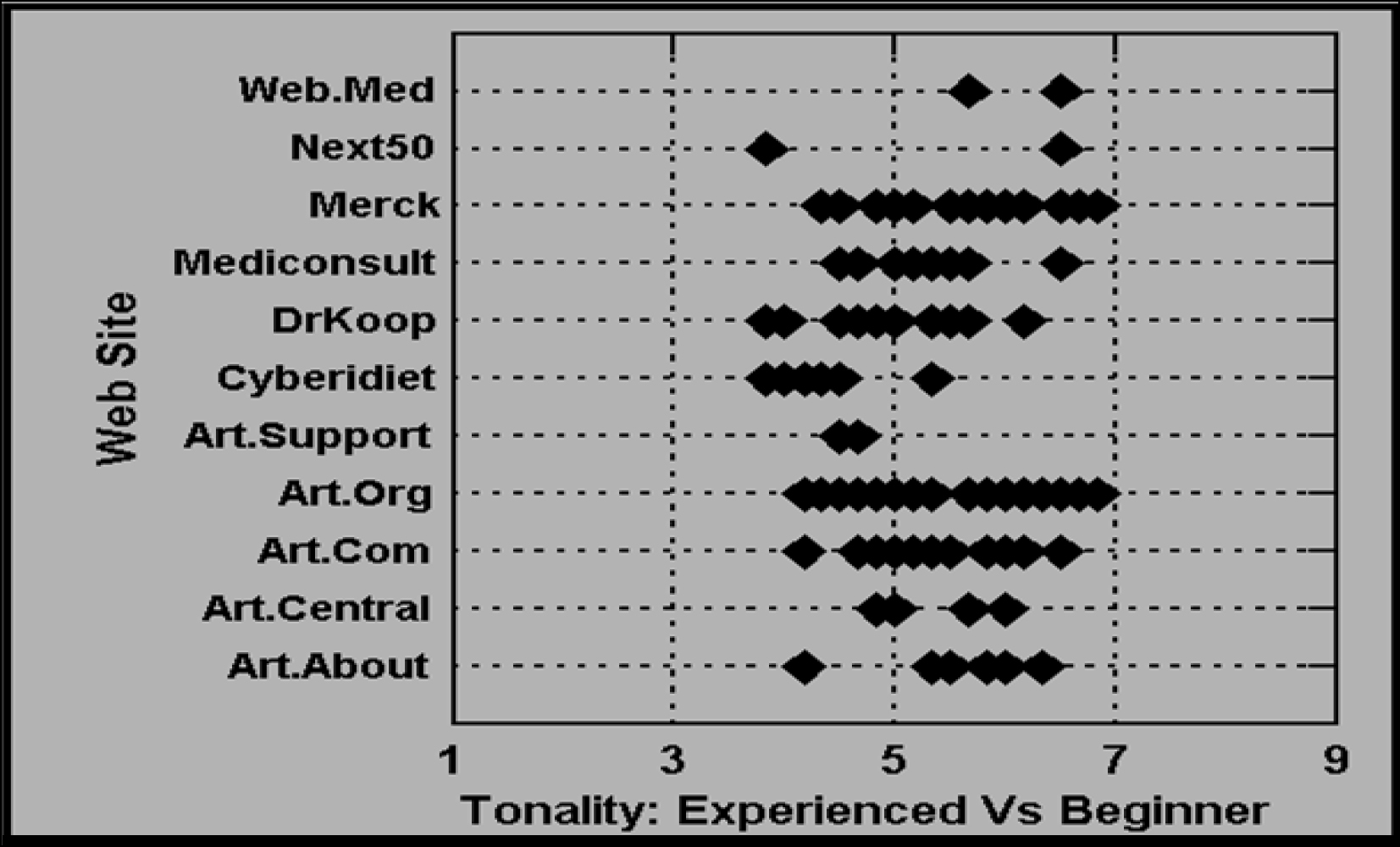

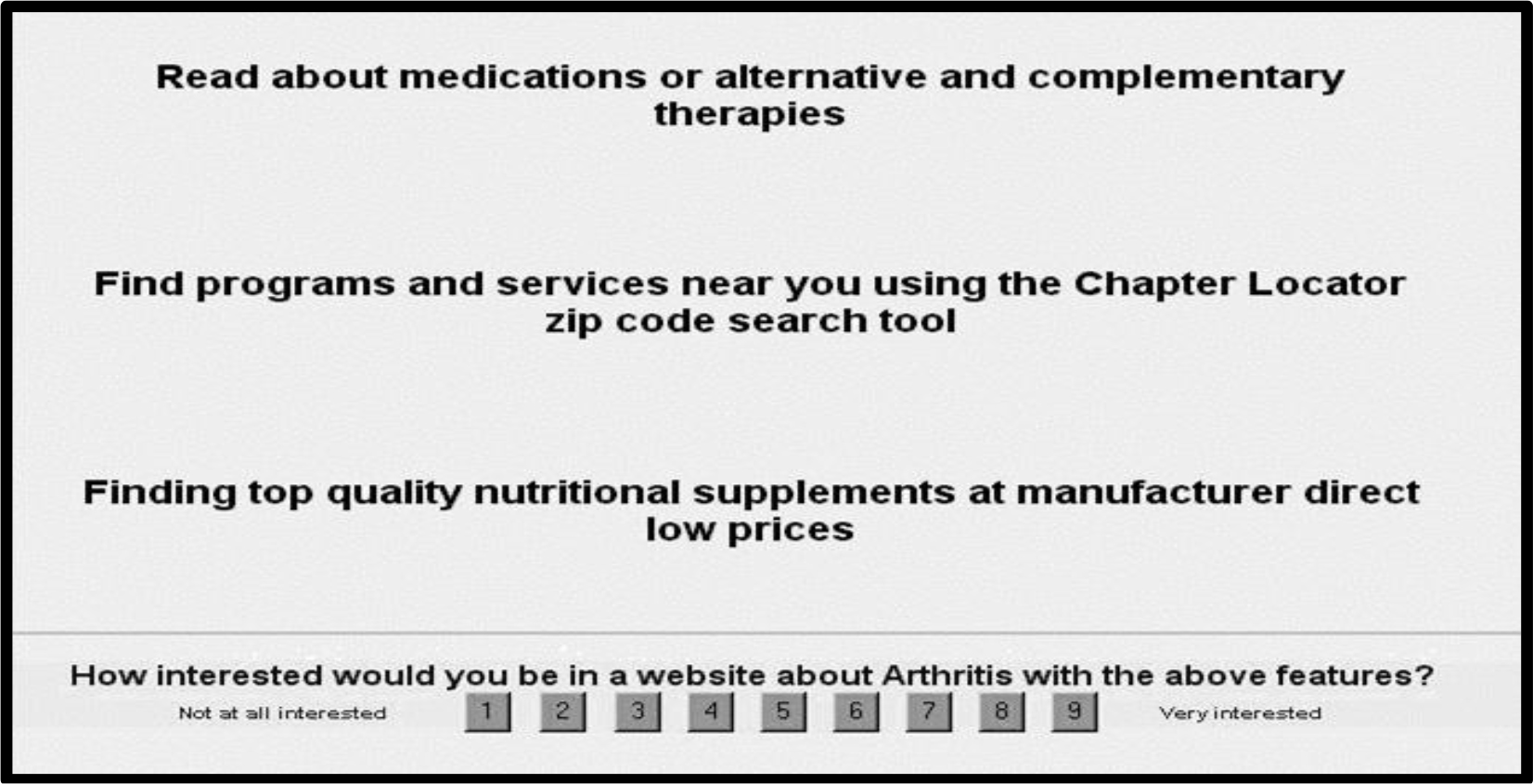

Two examples of vignette appear, respectively, in Figure 2 (all text), and in Figure 3 (one visual, the remaining elements are text.) The vignette is constructed ‘dynamically’ on the respondent’s computer, a process which makes the interview flow quickly, and is not onerous. The respondent need not wait for the transfer of screens from a host computer to the respondent’s computer.

Figure 2. An example of a vignette comprising text only, with the rating scale at the bottom.

Figure 3. Example of a vignette, comprising picture, text, with the rating question at the bottom.

Procedure

Running the arthritis study on the Web

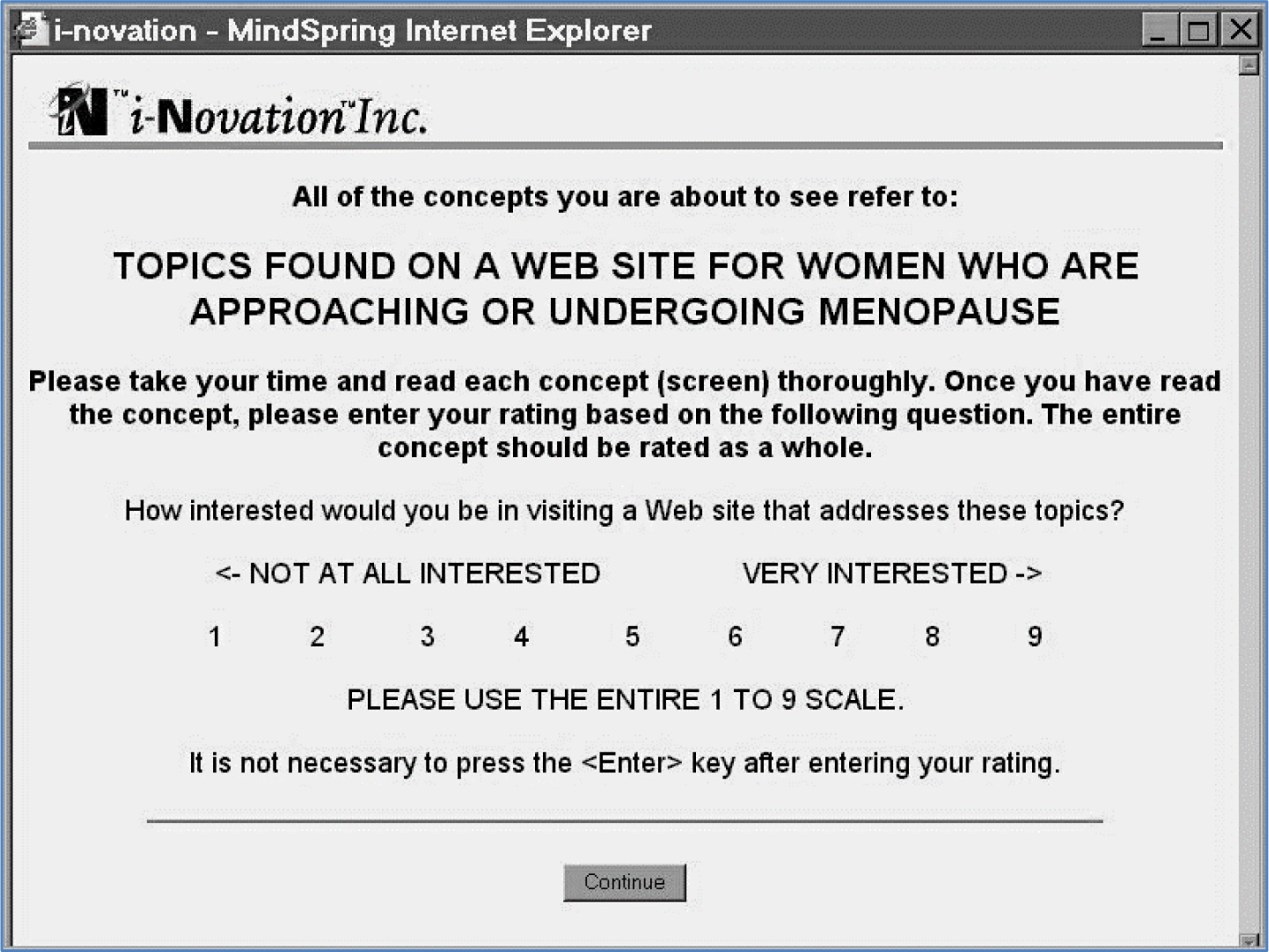

A great deal of consumer research has migrated to the Web, especially studies which do not involve the evaluation of several products in a short, sequential format, such as so-called ‘taste-testing.’ The Mind Genomics approach set up for this and related studies are perfectly adapted for the Web. Respondents who agree to participate first see an introductory screen (Figure 4), which tells them a little about the study, and what is expected of them. The less that one says about the purpose of the study, the better the study results, because it will be the elements, the specific messages, which drive the ratings.

Figure 4. The orientation page for the arthritis study

Sample

The panel comprised 144 individuals who reported that they have arthritis, or arthritis-type pain. The respondents were recruited by a Canadian panel provider, Open Venue, Ltd., which specialized in the recruitment of respondents for these studies, and especially the recruitment of respondents who satisfied specific screening. Table 5 shows the distribution of the 144 respondents falling into the self-defined classification groupings.

Table 5. The distribution of the 144 respondents falling into self-defined classification groupings.

|

|

Total |

Arthritis Med |

Tylenol |

Other Pain Reliever |

|

Base size |

144 |

26 |

63 |

83 |

|

Base – Column percent |

% |

% |

% |

% |

|

Health Status re Arthritis |

||||

|

Has Arthritis |

80 |

96 |

79 |

76 |

|

Gender |

||||

|

Males |

78 |

85 |

76 |

78 |

|

Females |

22 |

15 |

24 |

22 |

|

Age |

||||

|

Under 35–54 |

52 |

50 |

60 |

54 |

|

55 and older |

48 |

50 |

40 |

46 |

|

Usage |

||||

|

Arthritis Medication Users |

18 |

100 |

17 |

17 |

|

Tylenol® Users |

44 |

42 |

100 |

40 |

|

Other Pain Reliever Users |

58 |

54 |

52 |

100 |

|

Information Source about arthritis |

||||

|

Doctor |

89 |

96 |

86 |

89 |

|

Media |

60 |

65 |

51 |

65 |

|

Web |

51 |

38 |

44 |

54 |

|

Social Network |

44 |

35 |

43 |

47 |

|

|

56 |

54 |

48 |

53 |

|

Drugstore/Pharmacy |

56 |

54 |

54 |

58 |

Results

How the elements ‘drive’ the response – the Mind Genomics model

Each respondent evaluated two independently created sets of 25 vignettes, or 50 vignettes in total. Each set of 25 vignettes comprised a unique set of combinations, structured so that the elements appeared an equal number of times against different backgrounds, and were by statistically independent of each other. The two foregoing features of Mind Genomics enables the data to be analyzed using standard, off-the-shelf statistical procedures, such as OLS (ordinary least-squares) regression.

The data matrix comprised 50 rows or cases. The independent variables were the eight elements, coded 0 when absent from a case, and coded 1 when present in a case. The dependent variable was the transformed rating, which took on the value 0 when the original rating was 1–6, and, in turn, took on the value 100 when the original rating was 7–9. The small random number added to the dependent variable ensured that the OLS regression would not crash.

The analysis generated an additive constant and eight coefficients, one for each element that the respondent tested. The values of the remaining coefficients, for elements not tested by the respondent, were estimated by the algorithm explicated above. The result was a ‘complete’ model for each respondent, comprising an additive constant, actual coefficients for tested elements, and estimated coefficients for untested elements. The coefficients emerging from the algorithm are conservative estimates of the true coefficients that would be obtained when the elements are directly tested. Thus, the results reported here can be considered as conservative. Any messages which score well, i.e., have very high positive coefficients, in fact, may be even more powerful messages than one might conclude from the data.

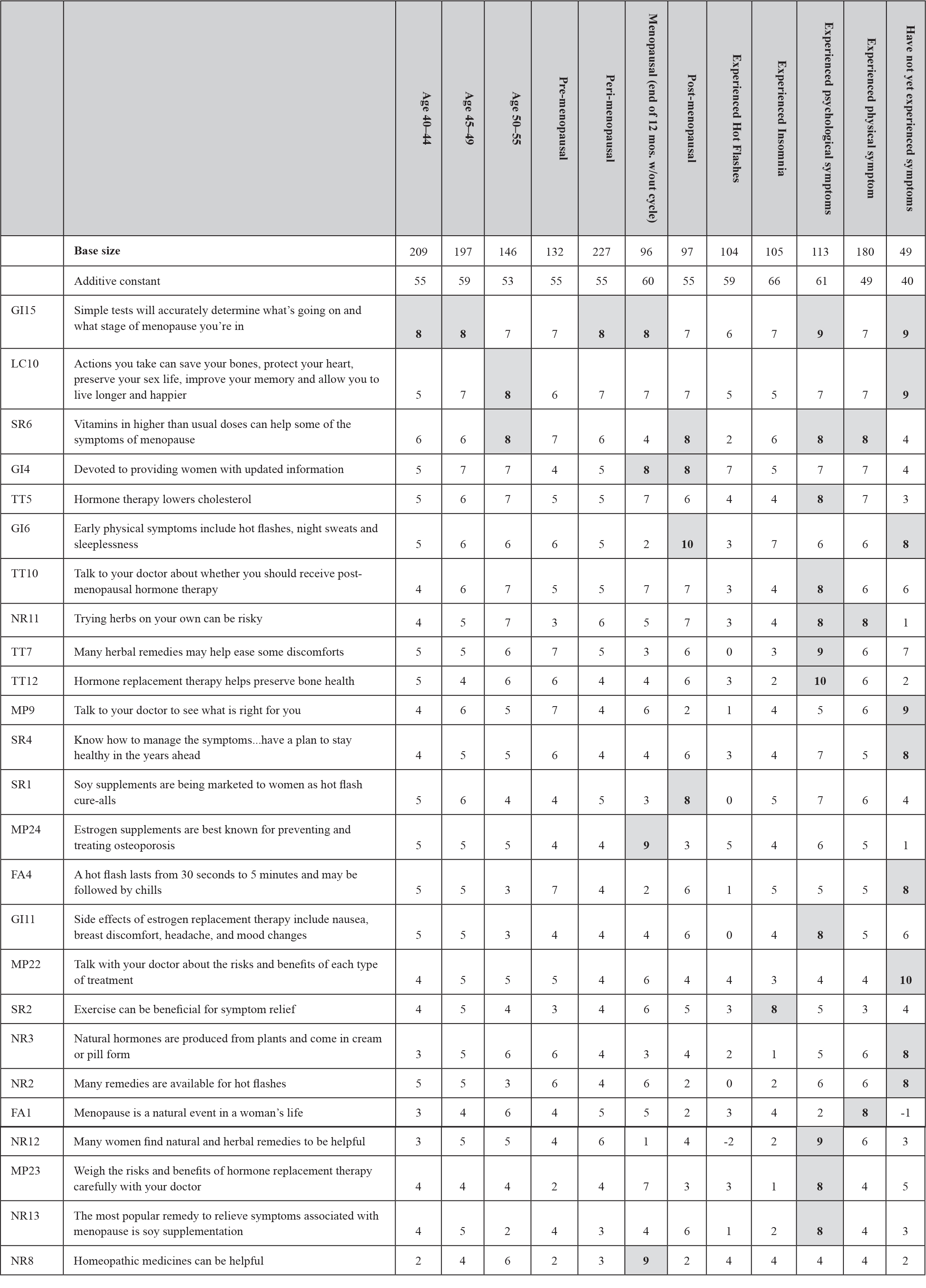

Table 6 suggests disappointing news. When we look at the data from the total panel of 144 respondents, we see an additive constant of 48, but very low coefficients. Respondents with arthritis are moderately interested in the messaging in general, but no message strongly drives interest. The answer may be in the subgroups that we can extract from knowing how the respondents describe themselves, but as we will see, the answer really emerges from the way the respondents think about the messages.

Table 6. Winning elements about arthritis from the total panel who are recruited to be arthritis sufferers.

|

|

|

Total Panel |

|

(144) |

||

|

Additive constant |

48 |

|

|

NE14 |

We recommend that before you start any exercise program, it is important that your physician examines you to see which types of exercise would be best for you |

5 |

|

GI11 |

Explore types of arthritis and treatments in the ‘Arthritis Answers’ |

4 |

|

NE11 |

We have great, healthy recipes, as well as information about vitamins, diet and medical conditions |

4 |

The strongest performing element, across key groups of respondents

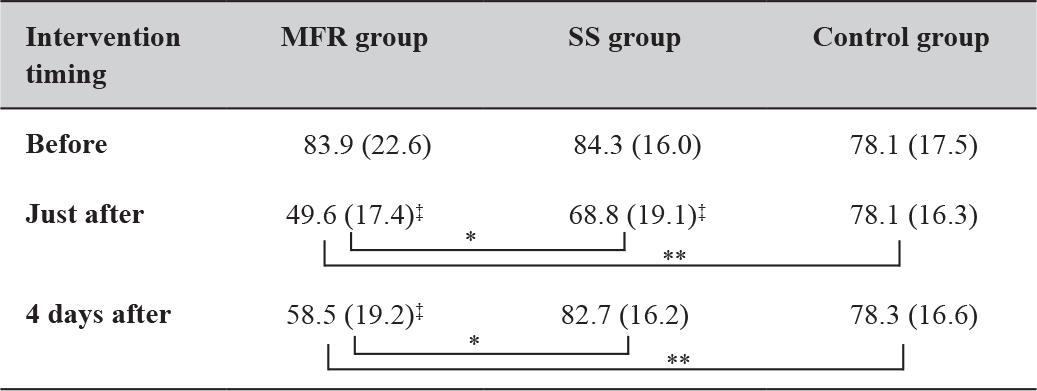

Table 7 shows the relevant parameters needed to interpret the results for total panel, key subgroups, and to-be-uncovered mind-sets. Even when looking at the self-defined subgroups, Table 7 shows that the strongest performing element for total panel does not perform particularly well when we look at the typical subgroups.

Table 7. How subgroups respond to the strongest performing element from the total panel (in bold italics). The table shows the subgroup, the base size, the additive constant from the model, and the estimated coefficient for the element (We recommend that…)

|

We recommend that before you start any exercise program, it is important that your physician examines you to see which types of exercise would be best for you http://www.merck.com/health/ |

|||

|

Respondent subgroup |

Base Size |

Additive Constant |

Element Coefficient |

|

Total Sample |

144 |

48 |

5 |

|

Gender – Males |

112 |

51 |

6 |

|

Gander – Females |

32 |

36 |

1 |

|

Age – 35–54 |

75 |

53 |

1 |

|

Age – 55 and older |

69 |

42 |

9 |

|

Use – Arthritis Medication |

26 |

50 |

0 |

|

Use – Tylenol® |

63 |

49 |

4 |

|

Use – Other Pain Relievers |

83 |

47 |

8 |

|

Information from – Doctor |

128 |

49 |

6 |

|

Information from – Media |

87 |

46 |

7 |

|

Information from – Web |

74 |

53 |

7 |

|

Information from – Social Network |

64 |

48 |

4 |

|

Information from – Print |

80 |

50 |

3 |

|

Information from – Drugstore/Pharmacy |

80 |

52 |

5 |

|

Condition – Has Arthritis |

115 |

54 |

6 |

|

Mind-Set 1 |

41 |

69 |

-4 |

|

Mind-Set 2 |

32 |

53 |

-4 |

|

Mind-Set 3 |

25 |

39 |

10 |

|

Mind-Set 4 |

46 |

30 |

16 |

Base Size – Number of respondents falling into the group. At the end of the experiment, the respondent completed a short classification questionnaire, providing gender, age, and so forth. It is from this self-profiling classification that we obtain the subgroups. The mind-set segments emerge from the analysis, reflecting groups of individuals who respond similarly to the messages. Their results will be presented below. Some of the groupings are mutually exclusive, like gender, age, Mind-Sets. Others are not, such as the source of one’s information about arthritis.

Additive Constant The model can be expressed as: Binary Rating = k0 + k1(Element 1) + k2(Element 2) … k170(Element 170). The additive constant, k0, is the estimated value that a vignette would receive on a 0–100-point scale without any elements present in the vignette. Of course, all vignettes comprised 2–5 elements, so the additive constant is a computed value. We can consider the additive constant as a baseline, showing up the likelihood of being interested in the arthritis website in the absence of specific messaging.

We can interpret the constant as follows in terms of interest in the arthritis website:

| Constant > | 70 = very high interest, elements don’t have to do any work to drive interest |

| Constant > | 40–70 = medium to high basic interest |

| Constant | 30–40 = moderate basic interest |

| Constant | 20–30 = low basic interest |

| Constant < | 20 = virtually no basic interest, elements drive interest |

Coefficient

The coefficient tells us the added expected incremental or decremental probability or proportion of respondents who would change their vote on the website from an original 1–6 (not interested) to the higher values 7–9 (interested.) The highest coefficient is +5, which should not necessarily surprise it when we look at the results from the total panel. People are different in what they like and dislike. The results from subgroups suggest some increased interest when we look at certain groups, such as those 55 and older. The real differences emergence when we divide the respondents by how they THINK, not by WHO they are. These differences manifest themselves in the Mind-Sets, especially Mind-Set 4. Below we will explain one way to discover these mind-sets.

We can interpret the coefficient as follows in terms of interest in the arthritis website:

| Coefficient > 15 | = Extremely strong driver of interest |

| Coefficient 10 to 15 | = Very strong driver of interest |

| Coefficient 5 to 10 | = oderate driver of interest |

| Coefficient 5 to –3 | = Not relevant as a driver of interest |

| Coefficient -3 or lower | = Begins to reduce interest, and should be avoided |

Exploring user groups

The study with 151 text elements and 19 pictures (all scraped from websites), and the self-profiling classification generates an extraordinary amount of data. What becomes both interesting and frustrating is that the individual data points, comprising the respondent, the element, and the coefficient, are each interesting in and of themselves. That is, the data generated by Mind Genomics is cognitively ‘rich.’ It is not only the pattern of data points which is of interest, showing a generality of nature, but rather the performance of each data point, since that data point is a meaningful message.

In recognition of the need to simplify the ‘story’, the analysis here will show only a few highlights, but then move to the essence of the findings, newly emerging mind-sets.

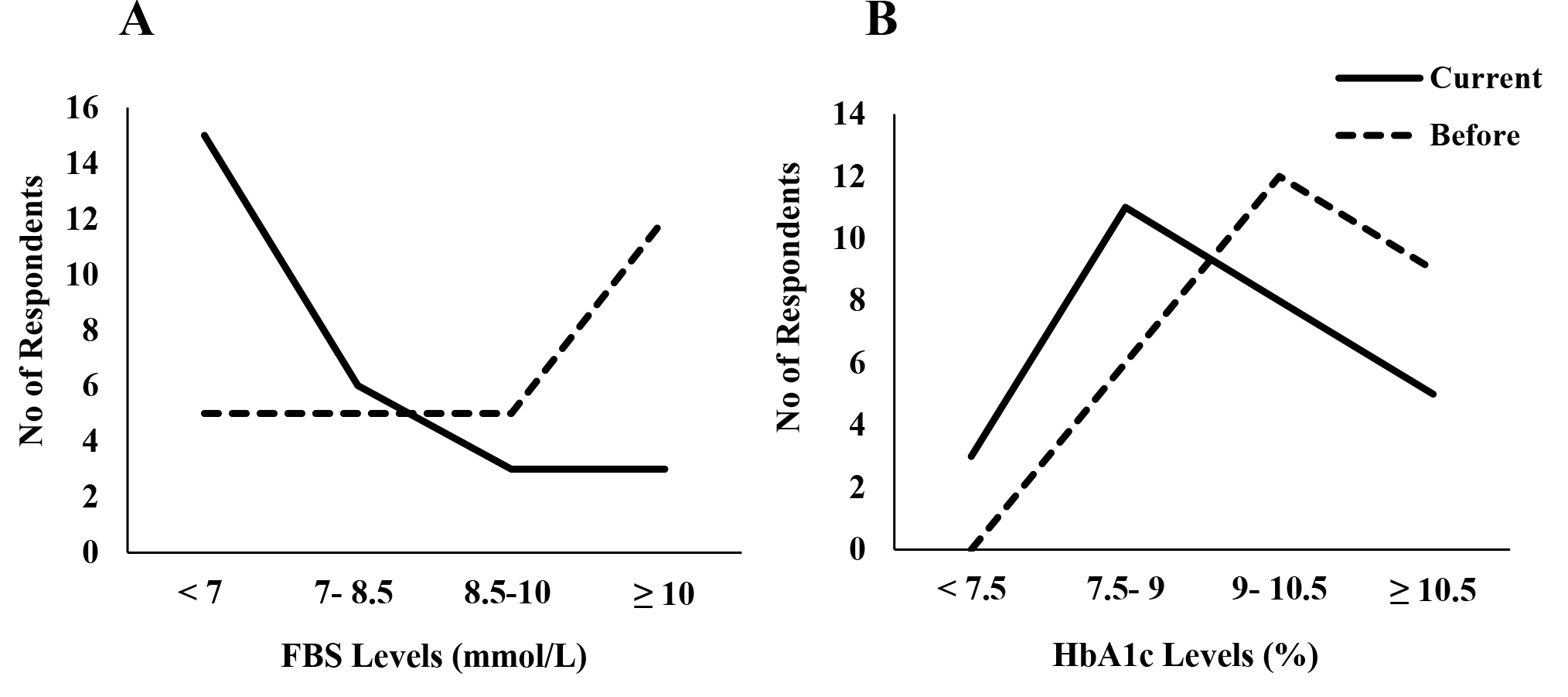

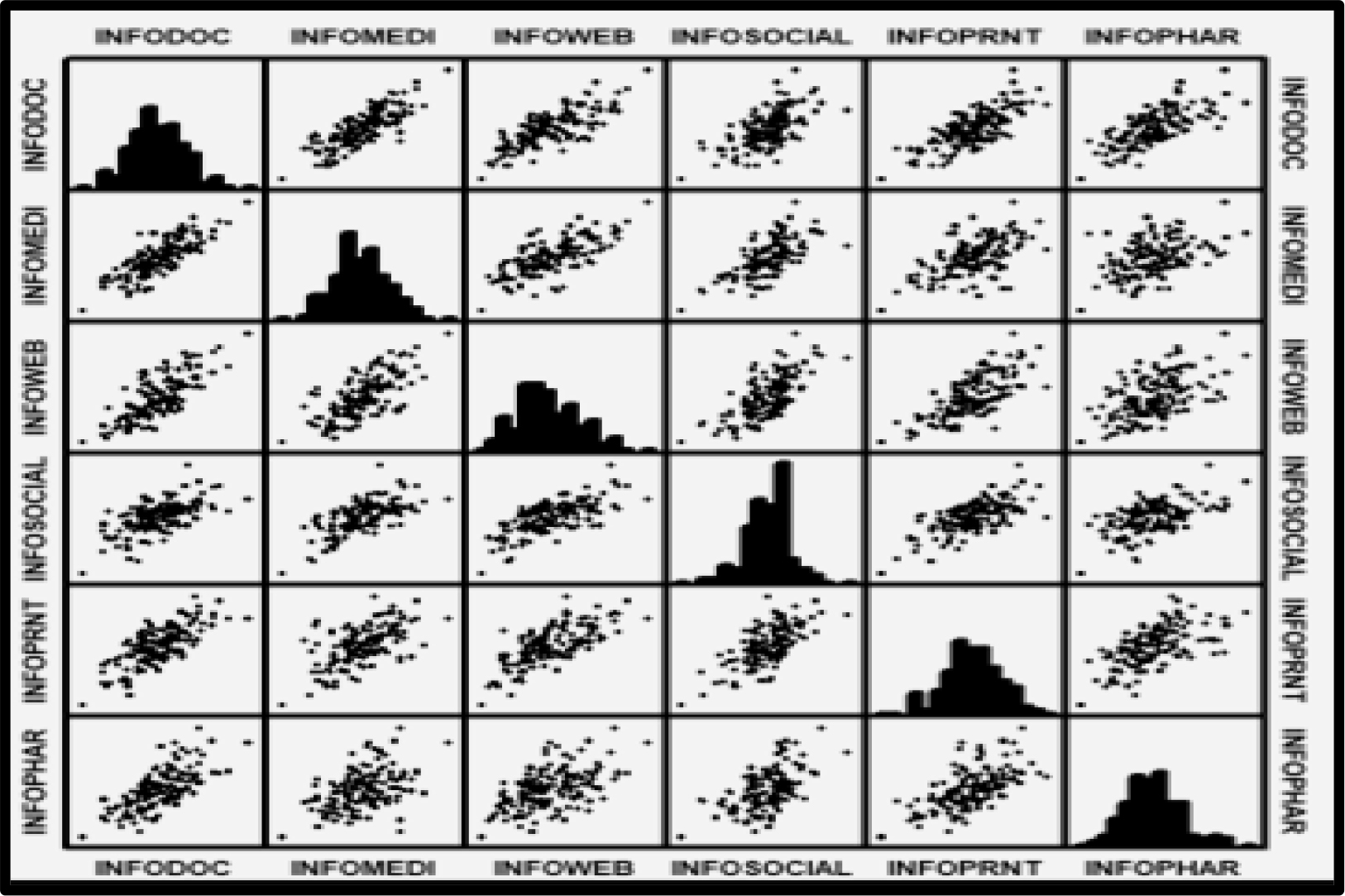

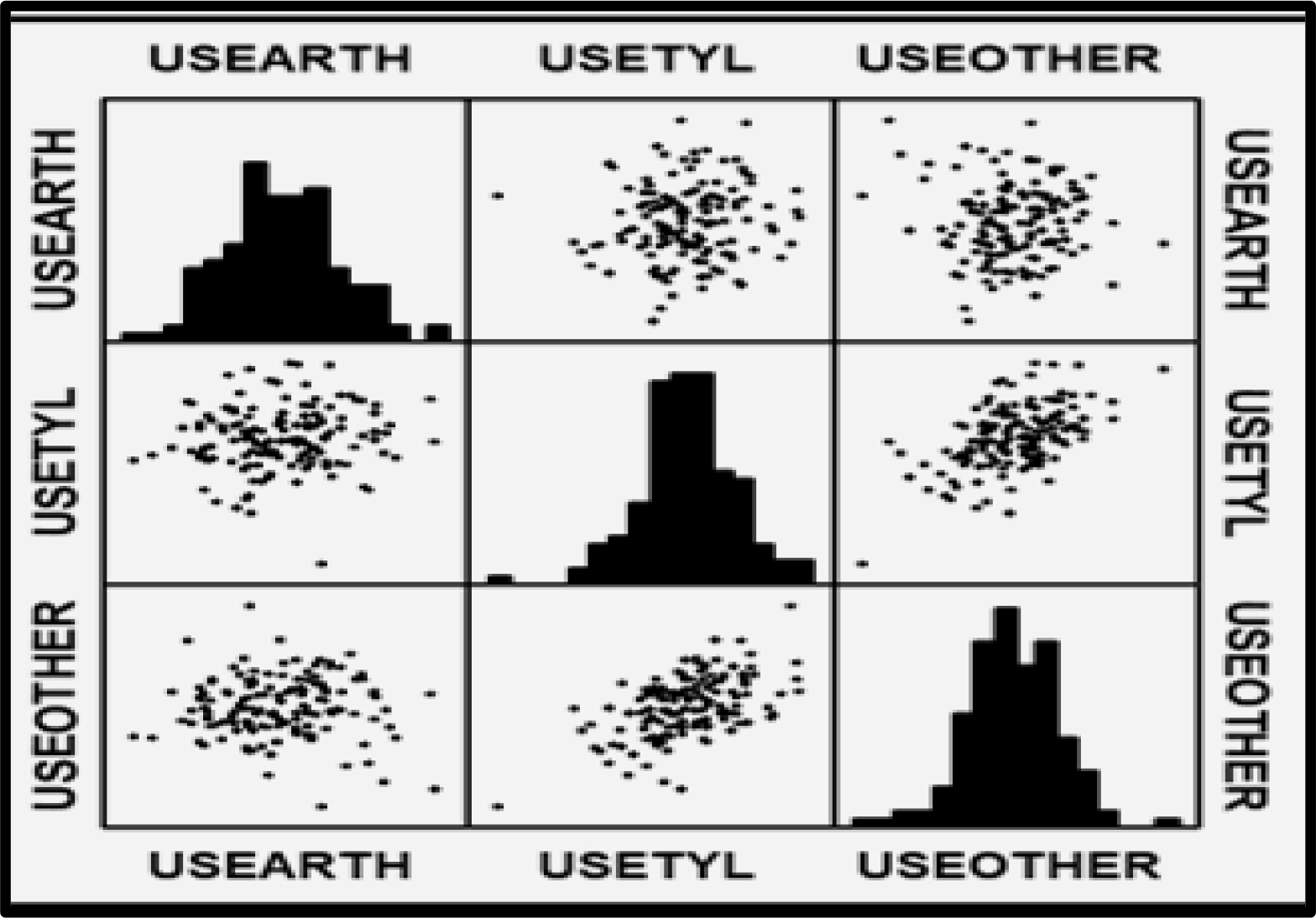

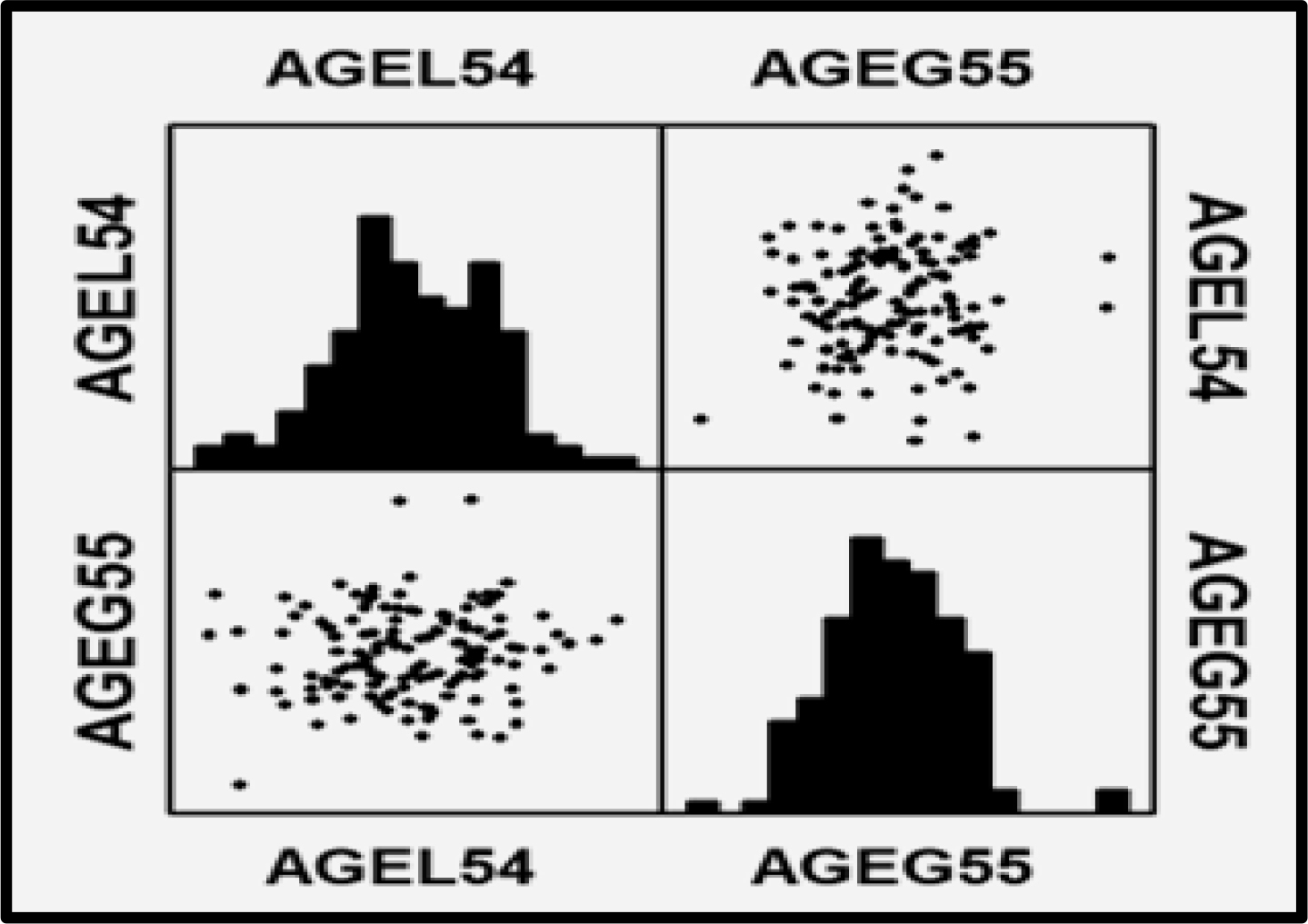

When we plot the coefficients text elements using a scatterplot, we find that the patterns are quite similar when the groups are defined by the source of information (Figure 5), a little more diverse when we plot the data by the type of product one uses (Figure 6), and quite unrelated when we plot the data by the two age groups (under 55 versus 55 and older, Figure 7).

Figure 5. Coefficients of the text elements. The scatterplot shows the plot of the corresponding elements for each pair of subgroups, defined by the source of information used by the respondent. The scatterplots suggest linear relations between the sources of information, using the individual 170 coefficients as the data points.

Figure 6. Coefficients of the text elements. The scatterplot shows the plot of the corresponding elements for each pair of subgroups, defined by the pain medicine used by the respondent. The pattern is noisy.

Figure 7. Coefficients of the text elements. The scatterplot shows the plot of the corresponding elements for each pair of subgroups, defined by the age of the respondent. There appears to be no relation between the patterns of coefficients generated by the younger respondents (age 54 or younger) versus the pattern generated by the older respondents (age 55 or older.)

The actual coefficients reveal that most elements are irrelevant in the mind of the respondents. That is, one can assemble dozens, even hundreds of elements, and assume that they all are effective because they appear in public on the Internet. Yet, the data suggest that they are not. Table 8 shows how one group, those who use arthritis medicines, are the ones who most strongly react to the messages. The respondents profiled themselves in terms of the medicines they took. The additive constants are virtually identical. When it comes to the coefficients, the only group of the three to show any real interest are those who take arthritis medicine. Furthermore, only six messages break through. The last line of Table 8 shows the one element appealing to other respondents. This element appeals only to uses of other medicines, besides arthritis medicine and Tylenol®, respectively. No messages appeal strongly to users of Tylenol®.

Table 8. Strong performing elements emerging from the division of respondents into the types of medicines they say they use for pain.

|

Elem |

Text |

Source |

Arthritis Med |

Use Tylenol® |

Use Other |

|

Additive constant |

50 |

49 |

47 |

||

|

Use Arthritis Medicine |

|||||

|

GI27 |

Up to date research on the aches and pains of arthritis and the effective homeopathic medicines |

Art.About |

14 |

-1 |

-5 |

|

AD2 |

Arthritis Advocacy Priorities – Read about the issues |

DrKoop |

14 |

2 |

2 |

|

AD6 |

Contact Congress – Quickly locate your legislators and send them a message |

DrKoop |

11 |

-2 |

-2 |

|

GI17 |

Living with arthritis – Coping strategies, hot and cold treatments, assistive devices, and more |

Art.Com |

11 |

0 |

-1 |

|

AD9 |

Fight for more research funding, insurance coverage for medications and the rights of people with arthritis |

DrKoop |

10 |

0 |

0 |

|

GI12 |

Find all your health and medical information here |

Art.Com |

10 |

-1 |

-5 |

|

Use Tylenol® |

|||||

|

NE14 |

We recommend that before you start any exercise program, it is important that your physician examines you to see which types of exercise would be best for you |

Merck |

0 |

4 |

8 |

These results are startling. They suggest that most of the messages used in the websites simply do not communicate, or at least do not persuade, despite the effort expended to create a meaningful, effective website.

The four mind-sets defined by how they respond to messaging

Our foray into the analysis of data by subgroups suggest that there is at least one group of respondents who react strongly to some elements. These are the users of arthritis medicine, in Table 8. The results from the total, and the results from a detailed analysis of coefficients from other subgroups (not reported) suggest that the conventional breakouts of respondents, based on who they ARE, and what they DO, do not reveal many strong-performing elements.

Mind Genomics studies often reveal the hard-to-believe finding that for the total panel relatively few elements perform well. A more productive way to discover strong-performing elements emerges when we consider the population as comprising a set of mutually exclusive ‘mind-sets, ’ viz., ideas which travel together. A mind-set can be considered an allele of a gene.

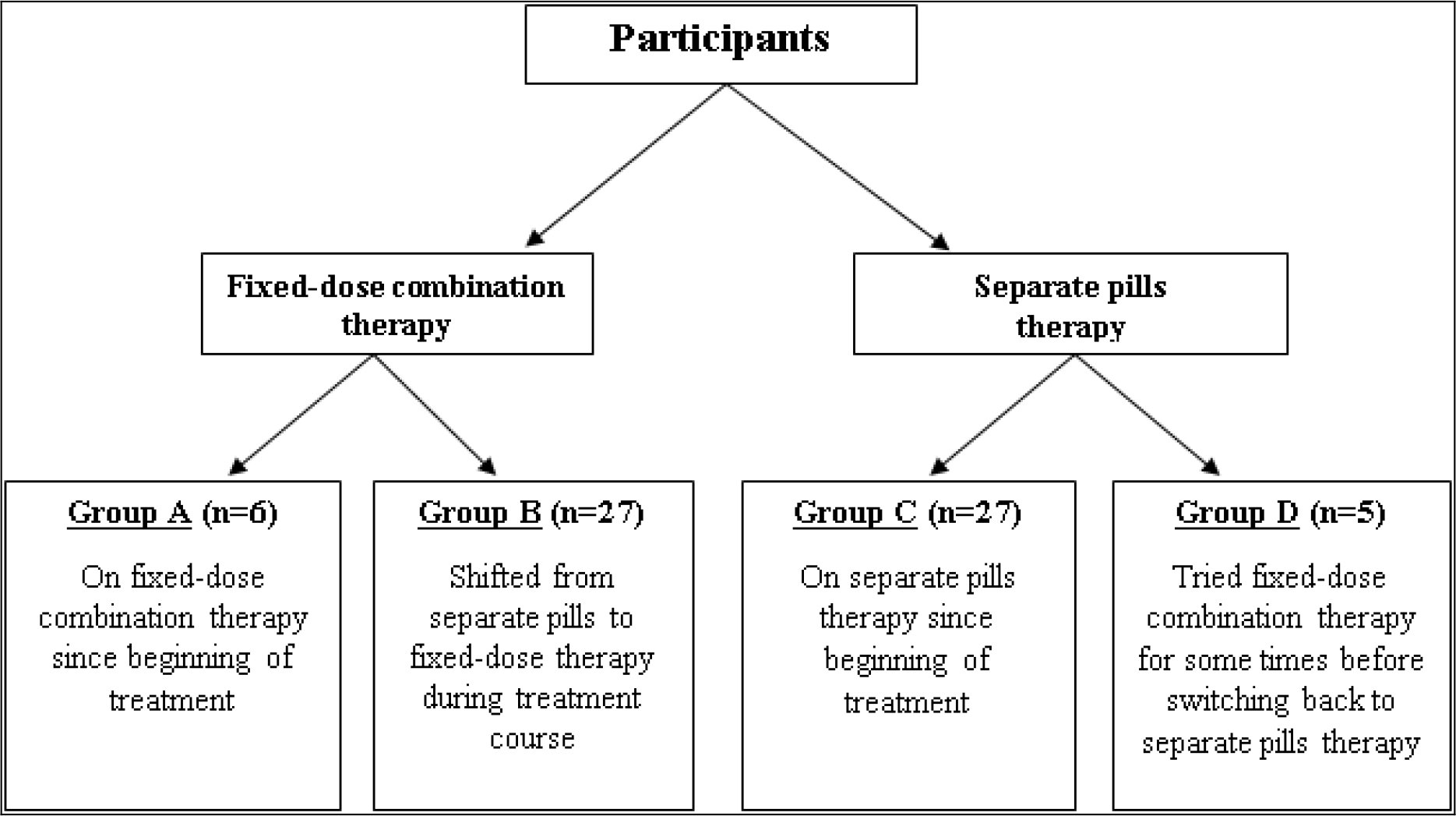

The mind-sets are obtained by computation, specifically clustering the coefficients of the 144 respondents so that the clusters comprise groups of respondents with similar patterns of coefficients for the 151 text coefficients. The specific mechanics of the clustering comprise the well-accepted method of k-means clustering. The coefficients comprise a small number of groups (parsimony), whose pattern of strong performing coefficients tell a story (interpretability.) It is important to keep in mind that the clustering and the discovery of mind-sets begins with objective statistical criteria based on the clustering algorithm. The subject step in clustering comprises the selection of the number of clusters after viewing the data, and the naming of the clusters.

The clustering emerged with four different mind-sets.

Mind Set 1 – High additive constant (great basic interest), but no element really shows a high coefficient

Mind Set 2 – Medium constant (interested), but few elements appeal to them. The elements with high coefficients are those involving ‘general wellness.’

Mind Set 3 – Lower constant (moderately interested), but there are a fair number of strongly performing elements. These elements deal with maintaining a good lifestyle, and learning about their arthritis

Mind Set 4 – Lowest constant (moderately interested), but again, they show a fair number of strongly performing elements. They are looking for community and emotional support of others, e.g., through message boards.

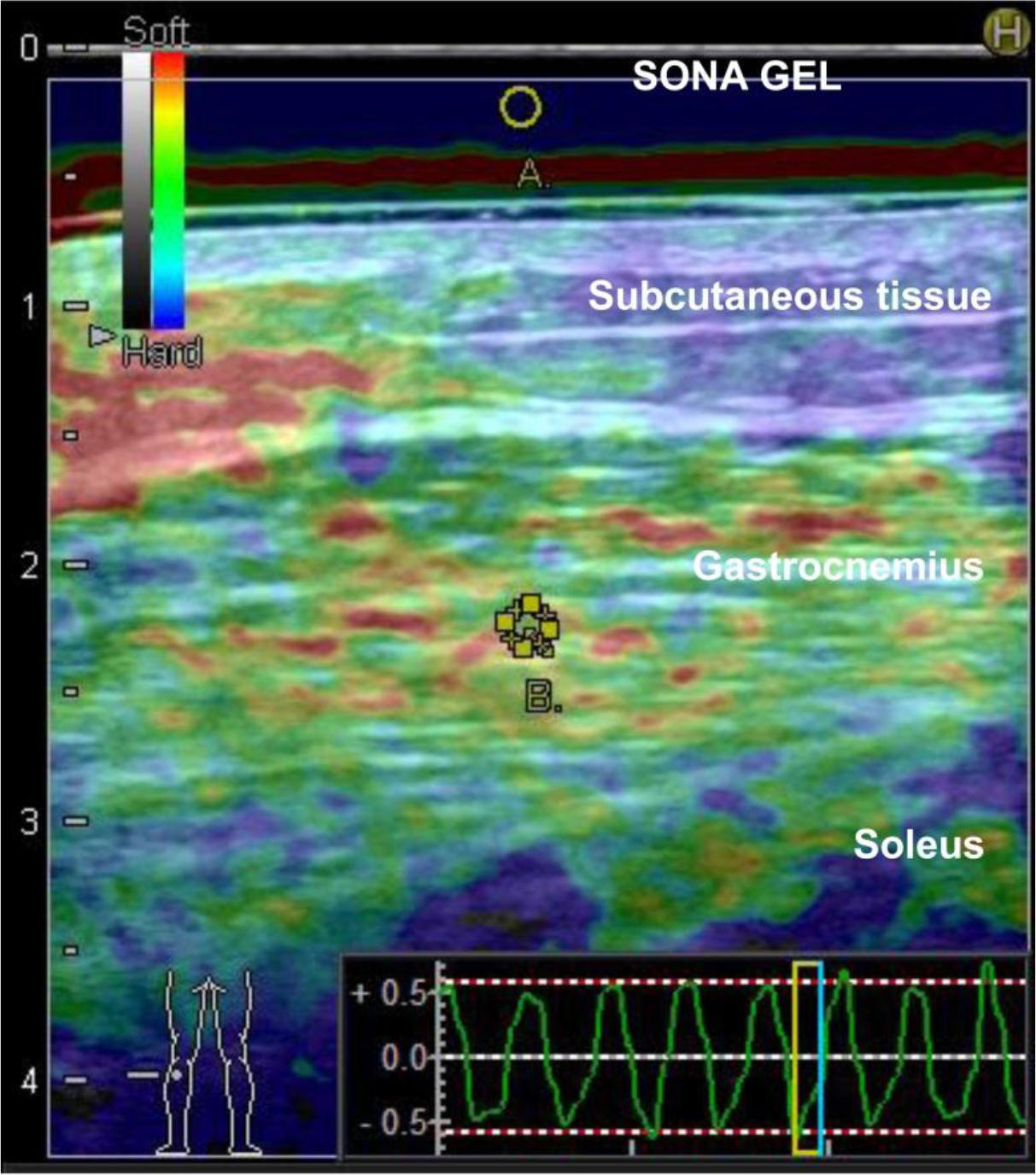

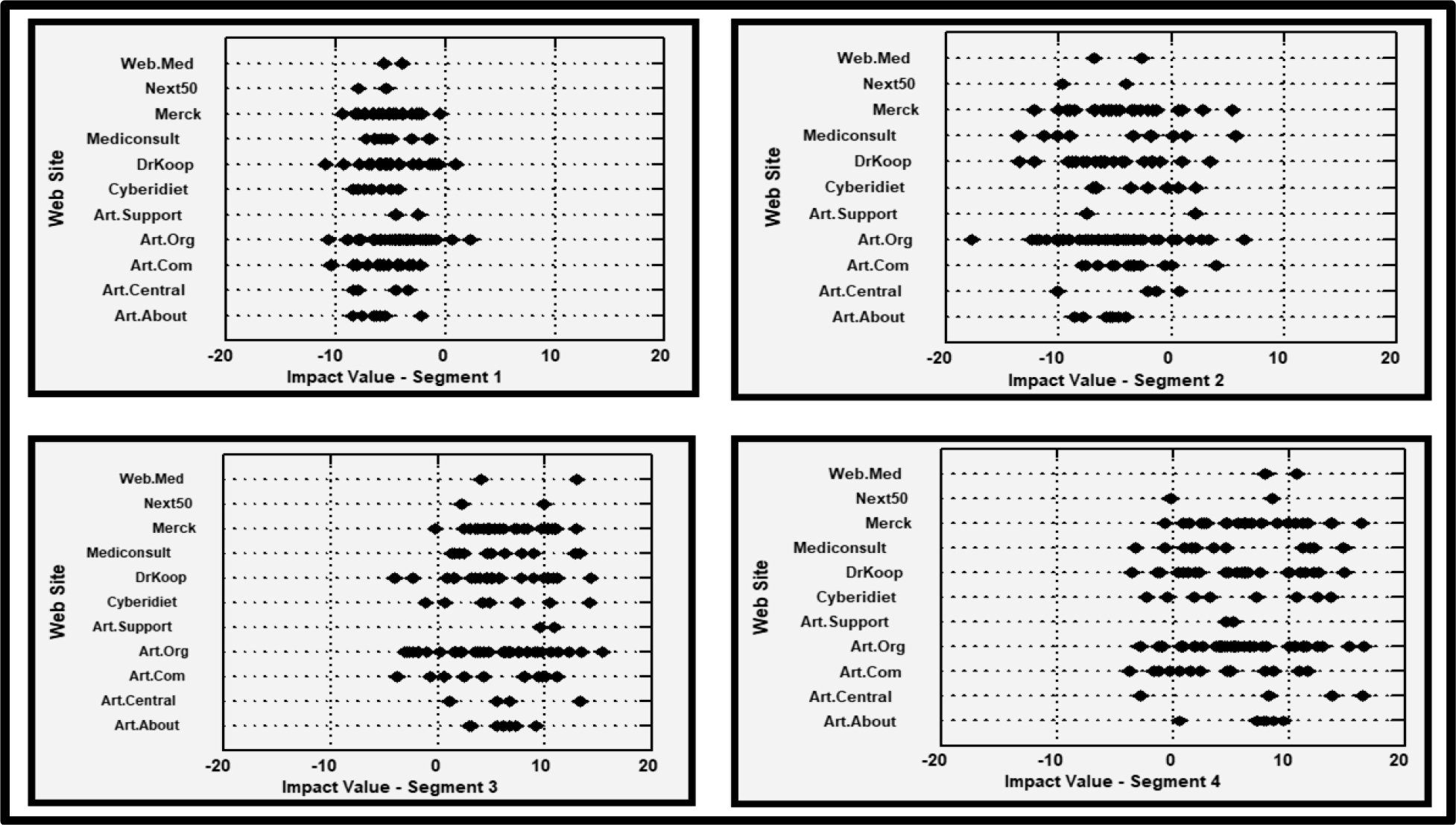

Figure 8 shows the coefficients laid out for each mind-set segment, giving a sense of the appeal of the elements in each website to the respondents in each of the four mind-set segments. The messages provided by the websites appeal to respondents in Mind-Sets 3 and 4, respectively.

Figure 8. How the mind-set segments respondents to the messages from the different websites. Impact value = coefficient.

Table 9 shows the strongest performing elements for each mind-set, as well as the corresponding performance of the same element among the total panel, which includes the mind-set as one of four contributing groups. It is clear from Table 9 that for the Total Panel, virtually no element performs well, as we saw above in Table 7.

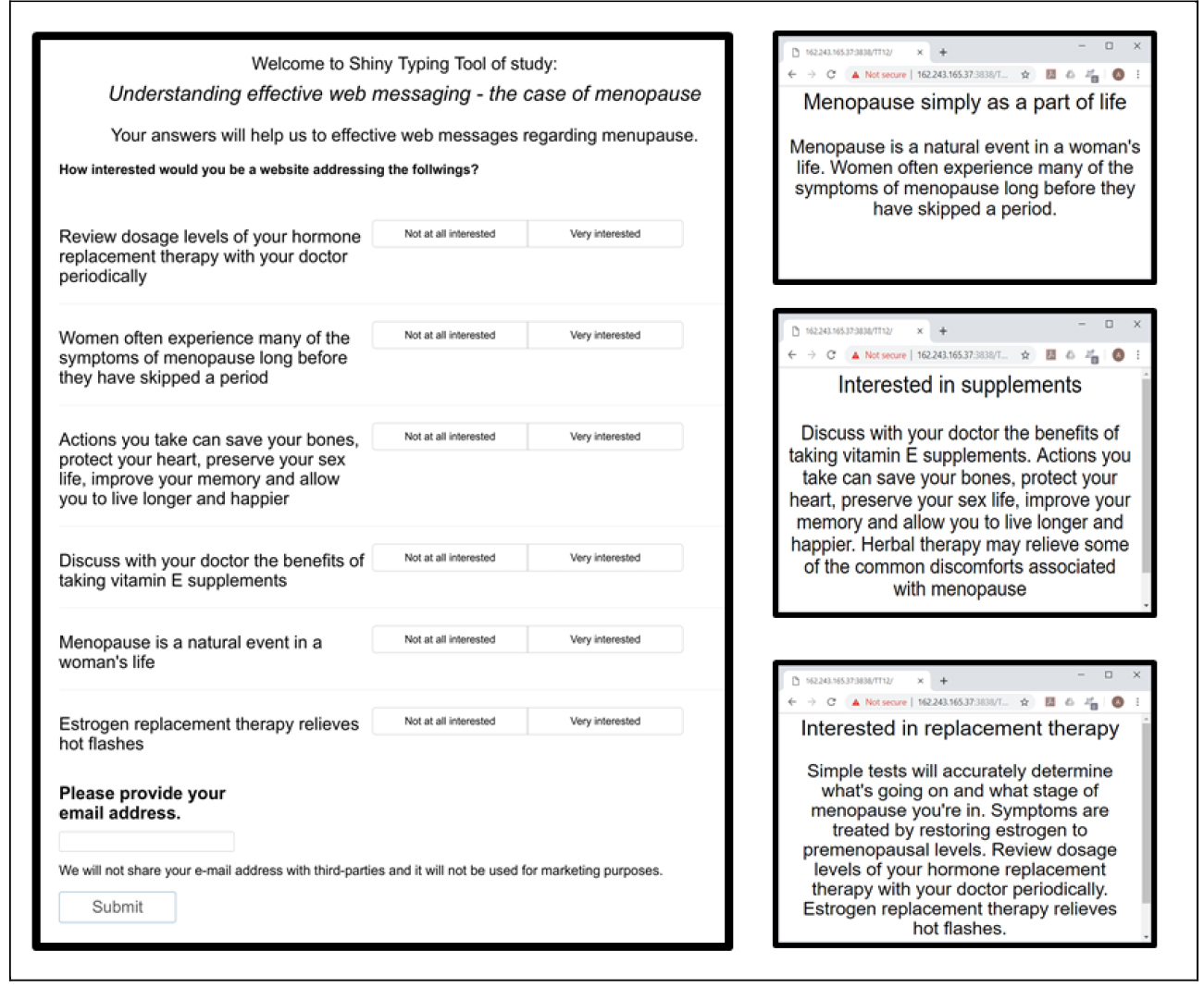

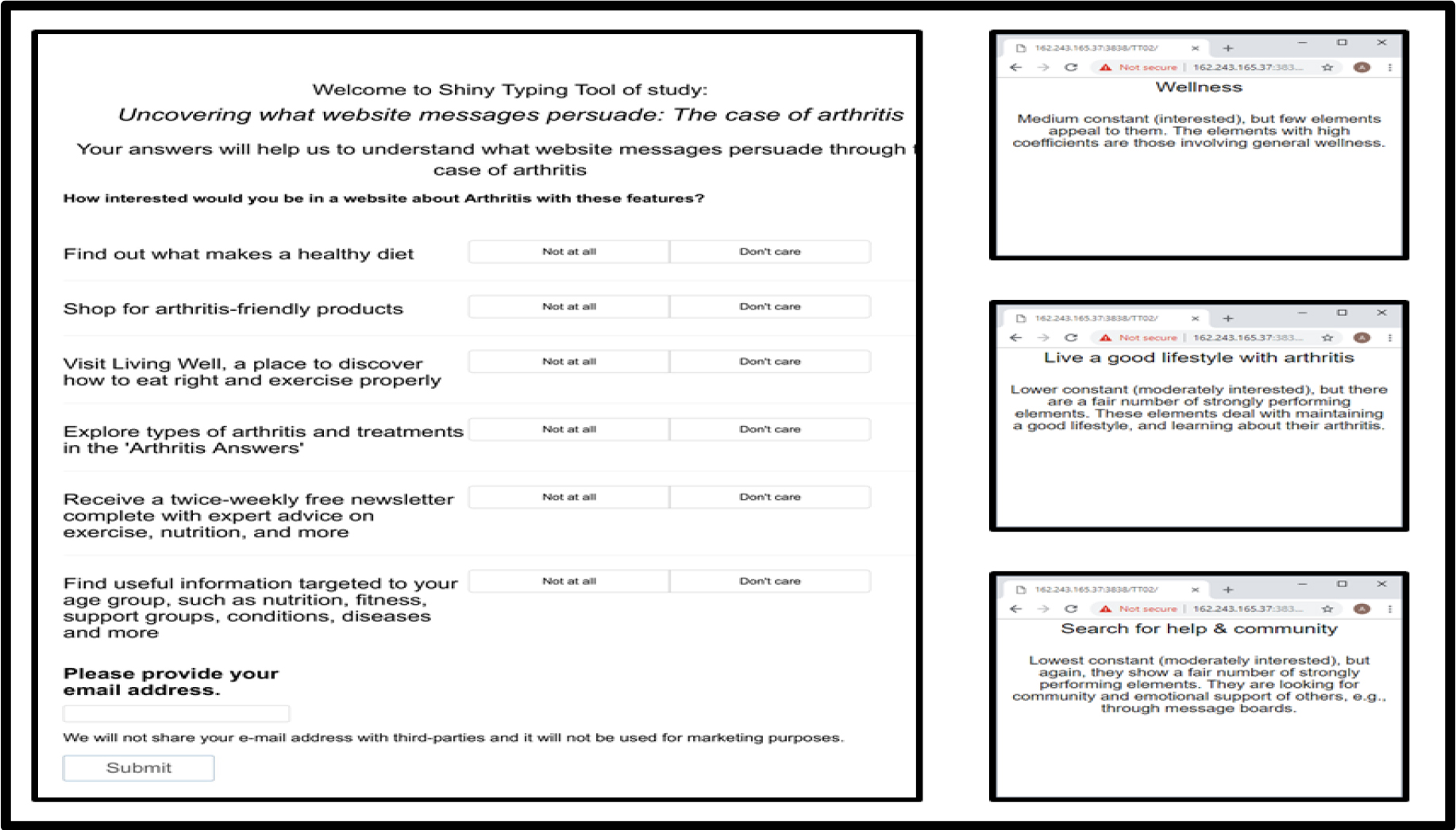

Figure 9. The PVI (Personal Viewpoint Identifier) for arthritis. The left section of the PVI shows the six questions and the two-point scale. The right section of the PVI shows the three feedback screens, corresponding to the three mind-sets (Mind-Set 1 & 2, Mind-Set 3, Mind-Set 4.)

Table 9. Strongest performing elements for the four mind-set segments

|

Text |

Source |

Total |

Mind Set |

|

|

|

Additive Constant |

|

||

|

|

Mind-Set 1 – Not responsive (Additive Constant=69) |

|

48 |

69 |

|

PR01 |

Learn more about the new ‘Speaking of Pain’ program, and find out how you can request a free brochure |

Art.Org |

3 |

2 |

|

|

Mind-Set 2 – Wellness (Additive Constant=53) |

|

48 |

53 |

|

EX03 |

Disease Center – Check here when you have questions about a medical condition |

Art.Org |

1 |

6 |

|

NE08 |

Visit Living Well, a place to discover how to eat right and exercise properly |

Mediconsult |

1 |

6 |

|

NE06 |

Find out what makes a healthy diet |

Merck |

3 |

5 |

|

|

Mind-Set 3 – Live a good lifestyle with arthritis |

|

48 |

39 |

|

GI14 |

Find useful information targeted to your age group, such as nutrition, fitness, support groups, conditions, diseases and more |

Art.Org |

3 |

15 |

|

CM11 |

Receive a twice-weekly free newsletter complete with expert advice on exercise, nutrition, and more |

DrKoop |

1 |

14 |

|

RS04 |

Search the Internet and our database for healthcare websites, hospitals and support |

Cyberidiet |

1 |

14 |

|

PR04 |

Our site follows the On-line Privacy Guidelines and the Guidelines on ‘Ethical Business Practice’ |

Art.Org |

0 |

13 |

|

EX07 |

Our disease topics have expanded information about living with diseases, finding support, the latest news and more |

Art.Central |

0 |

13 |

|

EX04 |

Read medical minutes and ask questions about your health |

Mediconsult |

2 |

13 |

|

GI23 |

Read about the types of arthritis and treatments in the ‘Arthritis Answers’ |

Web.Med |

3 |

13 |

|

NE06 |

Find out what makes a healthy diet |

Merck |

3 |

13 |

|

PR10 |

We have very strict policies and procedures designed to protect the privacy of our visitors |

Mediconsult |

0 |

13 |

|

GI21 |

Read about different types of arthritis and treatments |

Art.Org |

2 |

12 |

|

EB03 |

Visit Living Well…a place to discover how to strengthen your emotional health while living with a chronic condition |

Art.Org |

2 |

12 |

|

GI25 |

Tips for managing arthritis…bite-sized chunks of information with links to longer articles |

Art.Org |

2 |

11 |

|

NE11 |

We have great, healthy recipes, as well as information about vitamins, diet and medical conditions |

Art.Org |

4 |

11 |

|

RS13 |

Our new Caregiver Center can help with information and support for both givers and receivers of care |

DrKoop |

1 |

11 |

|

PR08 |

We have established practices and procedures to ensure that our privacy policies are effectively implemented |

Art.Com |

-1 |

11 |

|

PR09 |

We have engaged outside independent audits of our policies and practices |

Art.Com |

1 |

11 |

|

RS01 |

Click here for comprehensive information about your health |

Merck |

1 |

11 |

|

GI13 |

Find out how to protect yourself from bone loss |

Merck |

1 |

11 |

|

GI06 |

An archive of feature articles about all aspects of arthritis |

Art.Support |

0 |

11 |

|

AD09 |

Fight for more research funding, insurance coverage for medications and the rights of people with arthritis |

DrKoop |

2 |

11 |

|

NE12 |

Staying active is important for people with arthritis |

Merck |

0 |

11 |

|

PR07 |

We do not sell any personal information about our visitors, including e-mail addresses |

Art.Org |

0 |

11 |

|

|

Mind-Set 4 – Search for help & community |

|

48 |

30 |

|

SH03 |

Shop for arthritis-friendly products |

Art.Org |

1 |

16 |

|

GI11 |

Explore types of arthritis and treatments in the ‘Arthritis Answers’ |

Art.Central |

4 |

16 |

|

NE14 |

We recommend that before you start any exercise program, it is important that your physician examines you to see which types of exercise would be best for you |

Merck |

5 |

16 |

|

CM22 |

The message board is a great way for you to exchange ideas, thoughts, and express yourself |

Art.Org |

-2 |

15 |

|

GI01 |

View our online checklist on how to monitor medication use for seniors |

DrKoop |

-2 |

15 |

|

WF10 |

These guides will help you find information fast |

Mediconsult |

1 |

15 |

|

RS17 |

The Manual of Medical Information transforms the language of the professionals’ version into commonly used English |

Merck |

3 |

14 |

|

EB04 |

Welcome to the message boards – a place for you to connect with others, where new relationships and ideas can be formed and shared |

Art.Central |

0 |

14 |

|

SH01 |

Buy all your arthritis-care products here in the online store. Just click on a product link to browse hundreds of items |

Cyberidiet |

1 |

14 |

|

WF07 |

Give us your feedback about our site |

Merck |

2 |

14 |

|

CM20 |

The discussion group message board is moderated daily by a professional |

Art.Org |

3 |

13 |

|

WF18 |

Your personalized program can help you learn how to start and maintain a fitness program |

DrKoop |

1 |

13 |

|

WF13 |

Your personalized program can help you learn how to eat healthier foods |

Cyberidiet |

1 |

12 |

|

GI08 |

Read about arthritis lifestyle information – aquatics programs, exercise programs and other movement ideas |

Art.Org |

-1 |

12 |

|

EB01 |

Manage your arthritis and improve your life |

Art.Org |

1 |

12 |

|

SH06 |

Refill your prescriptions, find drug information and check drug interactions at the online pharmacy |

DrKoop |

0 |

12 |

|

GI04 |

A nationwide network of more than 2,000 diagnostic, surgical, and rehabilitation centers for the most up-to-date arthritis treatments |

Mediconsult |

0 |

12 |

|

SH04 |

You can fill prescriptions online |

Mediconsult |

0 |

12 |

|

EB06 |

The path to a healthy lifestyle |

Art.Com |

1 |

12 |

|

NE05 |

Print out your meal plan and follow it to a new you…recipes and a shopping list are included |

Merck |

1 |

12 |

|

WF12 |

Services for you…helpful tools and contact information |

Merck |

-1 |

12 |

|

CM18 |

Stop by the message boards and find others who share your interests and concerns |

Art.Org |

1 |

11 |

|

AD08 |

Enter a race or walk to raise funds needed for programs and research |

DrKoop |

0 |

11 |

|

EX02 |

Ask our fitness and nutrition expert any questions you may have |

Art.Org |

0 |

11 |

|

SH02 |

Order free brochures or buy an exercise tape in the Arthritis Store |

Mediconsult |

3 |

11 |

|

WF01 |

Take three or more health quizzes and enter to win a free tee-shirt |

Merck |

2 |

11 |

|

RS08 |

Sort through our Health Library Index – See a complete list of all arthritis articles |

Art.Org |

0 |

11 |

|

CM07 |

Be a smart reader! Anyone can visit and post messages on our boards |

DrKoop |

1 |

11 |

|

EX06 |

Minor Medical Directory – Click here for information about everyday health concerns |

Art.Com |

1 |

11 |

|

WF15 |

Your personalized program can help you learn how to make informed decisions about your treatment options |

Cyberidiet |

2 |

11 |

|

GI23 |

Read about the types of arthritis and treatments in the ‘Arthritis Answers’ |

Web.Med |

3 |

11 |

|

GI18 |

Looking for something specific or just want to browse? See the list of all articles in the Health Library |

Art.Org |

2 |

11 |

|

GI03 |

Taking Safety Measures…If you are at risk for osteoporosis, learn how to prevent falls and back injury |

Merck |

1 |

11 |

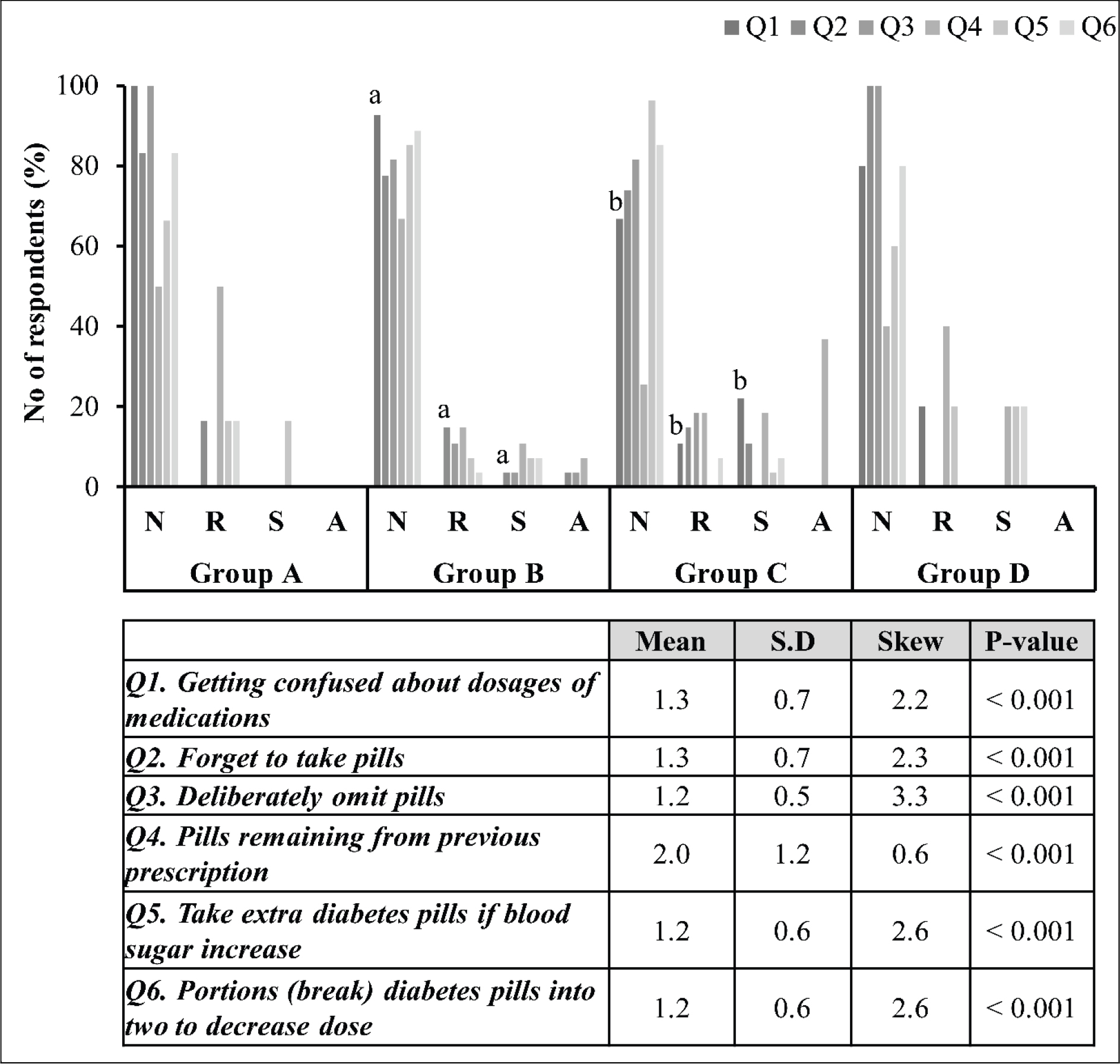

The strong performance of the elements is mirrored in the strong performance of some of the visuals. Table 10 lists the strong performing visuals. Only Mind-Set 3 and 4 respond strongly to the visuals, responding to different visuals. What appeals to one mind-set may be irrelevant to the other mind-set, and certainly irrelevant to Mind-Sets 1 and 2.

Table 10. Response of the four mind-sets to strongly visuals. The table shows only those elements whose coefficients were 10 or higher, denoting a strong positive response to the visual.

|

Total |

Mind-Set1 |

Mind-Set2 |

Mind-Set3 |

Mind-Set4 |

|

|

Mind-Set 1 – Not responsive |

|||||

|

Mind-Set 2 – Wellness |

|||||

|

Mind-Set 3 – Live a good lifestyle with arthritis |

|||||

|

Women wrapped in towel, holding pills |

-1 |

-7 |

1 |

11 |

-2 |

|

Four women exercising on mats |

0 |

-6 |

-6 |

11 |

4 |

|

Grandparents, with grandchild in middle |

0 |

-6 |

-8 |

10 |

5 |

|

Two doctors standing reviewing X rays |

1 |

-8 |

4 |

10 |

4 |

|

Mind-Set 4 – Search for help & community |

|||||

|

X rays of hands, showing ‘hot spots’ |

-1 |

-12 |

-14 |

2 |

15 |

|

Two hands holding each other |

-1 |

-7 |

-15 |

0 |

13 |

|

Two doctors seated, reviewing X rays |

1 |

-6 |

-9 |

2 |

12 |

|

Back of women with spinal cord highlighted |

-1 |

-7 |

-12 |

0 |

11 |

|

Mature couple, wife looking at husband |

1 |

-8 |

-8 |

8 |

10 |

Table 11 shows the composition of the four mind-sets, which are not quite equally distributed. It should become clear that to discover these mind-sets in the population will not be easy. The mind-sets appear to be distributed so that the four mind-sets are distributed approximately equally in each self-defined subgroup.

Table 11. Composition of the four mind-sets

|

|

Total |

Mind-Set 1 |

Mind-Set2 |

Mind-Set3 |

Mind-Set4 |

|

Base size: |

144 |

41 |

32 |

25 |

46 |

|

|

% |

% |

% |

% |

% |

|

Total sample |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

Gender-Males |

78 |

76 |

75 |

76 |

72 |

|

Gender-Females |

22 |

24 |

25 |

24 |

28 |

|

Age-35–54 |

52 |

56 |

56 |

60 |

41 |

|

Age-55 and older |

48 |

44 |

44 |

40 |

59 |

|

Use-Other Pain Reliever |

58 |

59 |

47 |

64 |

61 |

|

Use-Tylenol |

44 |

37 |

66 |

36 |

39 |

|

Arthritis Medication |

18 |

5 |

13 |

40 |

22 |

|

Information from Doctor |

89 |

85 |

81 |

88 |

98 |

|

Information from Media |

60 |

71 |

53 |

60 |

57 |

|

Information from Print |

56 |

56 |

50 |

68 |

52 |

|

Information from Drugstore/Pharmacy |

56 |

46 |

69 |

56 |

54 |

|

Information from Web |

51 |

66 |

47 |

44 |

46 |

|

Information from Social Network |

44 |

46 |

41 |

48 |

43 |

|

Has Arthritis |

80 |

85 |

69 |

80 |

83 |

Merging Mind-Sets 1 & 2, and finding the mind-sets in the general population for health promotion

This final section of the analysis focuses on the creation of a system to assign ‘new individuals’ to one of the mind-sets. As a preliminary step, we will combine Mind-Sets 1 and 2 into one mind-set, because neither mind-set seems to respond strongly to elements. This action, combining mind-sets, leaves us with Mind-Set (1 + 2), Mind-Set 3, and Mind-Set 4.

The messages and their corresponding coefficients work at this moment on the obtained data. In order to expand this knowledge on a wider population, modelling is needed in which we use the existing data (e.g. the coefficients of each element along with the segment membership) and create an ‘assignment model, ’ which we call the PVI (personal viewpoint analyzer.) The PVI can later be used to assign segment membership to new individuals.

Our first job is to make the assignment model easy to administer and analyze. Easy means making the assignment model, the PVI, short. In order to make the study shorter, we need to decrease the number of questions. The decrease in the number of questions is accomplished by selecting the most discriminating elements, e.g. those which show the highest deviation between the segments. This process identifies six text elements out of the 151 tested. These six elements end us as the base of the online personal viewpoint identification tool (PVI). As noted above, during the PVI development we merged the first two mind-sets in order to filter out respondents with low interest towards the elements.

The PVI instructs the to-be-typed participants to read the elements and rate each of them based on two-point scale. The six rating-questions and scale endpoints are similar to those used in the main study in order to keep consistency as much as possible. Participants are instructed to provide their e-mail address, which simply serves as an example in this case. Any other identification data can be used depending on the needs of the group authorizing the typing. The typing immediately leads to a web-site with the proper message for the respondent who is typing, based upon the respondent’s assigned mind-set.

As soon as the participants answered all questions and indicated their e-mail addresses, the PVI computes the most probable segment membership of the given respondent. The PVI stores the answers and e-mail address, which are suitable to get an overview of the participants or the ratio of the segments in the population. Participants are thanked for their participation by a thank you message which also presents their most probable segment membership. The thank you screen indicates the name of the segment the given participant belongs to along with a short description of the segment in order to give detailed information about the segment. By clicking on the refresh button of the browser, a new PVI test starts. Figure 9 shows the PVI tool for arthritis. The PVI is available on the following link: http://162.243.165.37:3838/TT02/

Discussion and Conclusion

This study revealed the patient perspective regarding effective communication messaging in arthritis. The communication messaging to promote self-management of arthritis suggest either three or four mindset-segments, depending upon how one considers mind-sets which do not ‘tell a clear story.’ This study illustrated how a medical professional may rapidly assign a person showing up in the clinic into the most likely, appropriate mind-set segment, and in turn know ahead-of-time the type of messages and treatment to which this specific new patient will respond.

People in the first mindset are not responsive to any communication. People in the second mind-set positively respond to communication messaging that target higher general wellness. These two mind-sets can be combined because there is little to strongly attract them. People in the third mind-set segment positively respond to communication messaging which emphasize a good lifestyle allowing time with family and becoming more health literate regarding Arthritis. People in the fourth mind-set segment respond positively to messaging which focus on relationships, emotional support and community.

The ability of a medical professional to easily tailor communication messaging to an individual by mind-set segment, echoes advanced health policies of personalized medicine. Tailored communication may make a vast difference in creating patient-physician collaboration, higher health literacy, higher engagement, and better choices in a shorter process to self-management of Arthritis [26].

References

- Hawker GA, Stewart L, French MR, Cibere J, Jordan JM, et al. (2008) Understanding the pain experience in hip and knee osteoarthritis—an OARSI/OMERACT initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 16: 415–422. [crossref]

- Woolhead G, Gooberman-Hill R, Dieppe P, Hawker G (2010) Night pain in hip and knee osteoarthritis: a focus group study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 62: 944–949. [crossref]

- Rosemann T, Wensing M, Joest K, Backenstrass M, Mahler C, et al. (2006) Problems and needs for improving primary care of osteoarthritis patients; the views of patients, general practitioners and practice nurses. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 7: 48.

- Gignac MA, Davis AM, Hawker G, Wright JG, Mahomed N, et al. (2006) “What do you expect? You’re just getting older”: a comparison of perceived osteoarthritis-related and aging-related health experiences in middle- and older-age adults. Arthritis Rheum 55: 905–912.

- Zuidema RM, Repping-Wuts H, Evers AWM, Van Gaal BGI, Van Achterberg T, et al. (2015) What do we know about rheumatoid arthritis patients’ support needs for self-management? A scoping review. International journal of nursing studies 52: 1617–1624.

- Boers M, Dijkmans B, Gabriel S, Maradit-Kremers H, O’Dell J, et al. (2004) Making an impact on mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: targeting cardiovascular comorbidity. Arthritis Rheum 50: 1734–1739.

- Kennedy A, Rogers A, Bower P (2007) Support for self care for patients with chronic disease. British Medical Journal 335: 968–970.

- van Houtum L, Rijken M, Heijmans M, Groenewegen P (2013) Self-management support needs of patients with chronic illness: do needs for support differ according to the course of illness? Patient Educ Couns 93: 626–632.

- Gabay G (2015) Perceived control over health, communication and patient–physician trust. Patient education and counseling 98: 1550–1557.

- Gabay G, Moskowitz HR, Silcher M, Galanter E (2017) The New Novum Organum: Policy, Perceptions and Emotions in Healthcare. Pardes-Ann Harbor Academic Publishing.

- Gabay G (2016) Exploring perceived control and self-rated health in re-admissions among younger adults: A retrospective study. Patient education and counseling 99: 800–806.

- Wilcox S, Der Ananian C, Abbott J, Vrazel J, Ramsey C, et al. (2006) Perceived exercise barriers, enablers, and benefits among exercising and non-exercising adults with arthritis: results from a qualitative study. Arthritis Rheum 55: 616–627.

- Parsons GE, Godfrey H, Jester RF (2009) Living with severe osteoarthritis while awaiting hip and knee joint surgery. Musculoskelet Care 7: 121–135.

- Browne K, Roseman D, Shaller D, Edgman-Levitan S (2010) Analysis and Commentary: Measuring patient experience as a strategy for improving primary care. Health Affairs 29: 921–925.

- Law RJ, Breslin A, Oliver EJ, Mawn L, Markland DA, et al. (2010) Perceptions of the effects of exercise on joint health in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 49: 2444–2451.

- John H, Hale ED, Treharne GJ, Carroll D, Kitas GD (2009) ‘Extra information a bit further down the line’: rheumatoid arthritis patients’ perceptions of developing educational material about the cardiovascular disease risk. Musculoskelet Care 7: 272–287.

- Mann C, Gooberman-Hill R (2011) Health care provision for osteoarthritis: concordance between what patients would like and what health professionals think they should have. Arthritis care & research, 63: 963–972.

- Ahlmen, M, Nordenskiold U, Archenholtz B, Thyberg I, Ronnqvist R, et al. (2005) Rheumatology outcomes: the patient’s perspective. A multicentre focus group interview study of Swedish rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 44: 105–110.

- Makelainen P, Vehvila¨inen-Julkunen K, Pietila¨ A (2009) Rheumatoid arthritis patient education: RA patients’ experience. Journal of Clinical Nursing 18: 2058–2065.

- Kristiansen TM, Primdahl J, Antoft R, Horslev-Petersen K (2012) Everyday life with rheumatoid arthritis and implications for patient education and clinical practice: a focus group study. Musculoskelet Care 10: 29–38.

- Ward V, Hill J, Hale C, Bird H, Quinn H, et al. (2007) Patient priorities of care in rheumatology outpatient clinics: a qualitative study. Musculoskelet Care 5: 216–228.

- Pier CS, Shandley KA, Fischer JL, Burstein F, Nelson MR, et al. (2008) Identifying the health and mental health information needs of people with coronary heart disease, with and without depression. Med J Aust 188: 142–144.

- Reed M, Harrington R, Duggan A, Wood VA (2010) Meeting stroke survivors’ perceived needs: a qualitative study of a community-based exercise and education scheme. Clinical Rehabilitation 24: 16–25.

- Taylor DM, Cameron JI, Walsh L, McEwen S, Kagan A, et al. (2009) Exploring the feasibility of videoconference delivery of a self-management program to rural participants with stroke. Telemed. e-Health 15: 646–654.

- Moskowitz HR, Martin D (1993) How computer aided design and presentation of concepts speeds up the product development process. In Esomar Marketing Research Congress: 405.

- Chilton F, Collett RA (2008) Treatment choices, preferences and decision-making by patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Musculoskelet Care 6: 1–14.

- Ryan S, Hassell A, Dawes P, Kendall S (2003) Perceptions of control in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Nurs Times 99: 36–38. [crossref]

- Kennedy A, Rogers A, Bowen R, Lee V, Blakeman T, et al. (2014) Implementing, embedding and integrating self-management support tools for people with long-term conditions in primary care nursing: a qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies 51: 1103–1113.