Abstract

The change in nutritional status is observed in patients with Motor Neuron Disease, in body composition. The electrical bio impedance method (BIA) determines lean mass, fat mass and phase angle, by estimating total body water. ALSFRS-R is used to monitor the functionality and progression of the disease.

Objective: To evaluate the composition with ALSFRS-R.

Methodology: Cross-sectional study in adult patients with conclusive diagnosis of MND. For the classification of nutritional status, BMI was used, and for body composition analysis, measurements of lean mass, fat mass, total body water and phase angle. Results: patients, with 54.8% of males with median age of 61.0 years. 77.4% presented the appendicular form of the disease. The median score of ALSFRS-R was 27 points, and the average BMI was 22.6 kg / m2. The phase angle had an average of 3.9 in women, and 4.1 in men. For statistical analysis, results with a probability of type I error lower than 5% (p <0.05 and p <0.001) were considered as statistically significant. The BMI and phase angle were correlated with the scale scores.

Conclusion: Nutritional status is directly related to disease progression, and depletion of body compartments influences the functionality of patients with MND.

Keywords

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, body composition, nutritional state, functionality

Introduction

Motor neuron disease (MND) is a progressive, degenerative hyper catabolic disease with involvement of the motor neurons of the cortex, brain stem and spinal cord [1]. Due to the symptoms and the rapid progression of the disease, depletion of nutritional status is observed. Patients present a reduction in the lean mass inherent to disease progression, and the increase in body fat may be positively associated with disease progression [2].

Electrical bio impedance is a tool used to analyze body composition, and it is classified as a gold standard for evaluation in MND [3].The interpretation of the phase angle, allows the measurement of the body changes, and was proposed as an index of malnutrition, or prognostic factor of survival in other diseases. The association of the evaluation of the body composition with the functionality of these patients may help in the treatment of the evolution of the MND / ALS [4].

Hence, the objective of this work is to evaluate the body composition and to analyze the association of the nutritional state with the functionality of patients with MND.

Methods

A cross-sectional study carried out at the Neuromuscular Disease Research Section of the Federal University of São Paulo, approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the University, under number 0606/2016, with authorization to participate, through a signed Free and Informed Consent Form.

The study was carried out from March to July 2016. Adult patients with a defined diagnosis were included [5]. Patients who did not tolerate being in the supine position for the examination were also excluded from the study.

For the analysis of the body composition, the Bio impedance device “BIODYNAMICS MODELO 450” was used, which provides clinical data of Body Composition and Hydration, such as body fat, total body water, lean mass and phase angle with precision of +/- 0.2 %.

The Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale (ALSFRS-R) was applied, analyzed in two ways: by total score, and by domains (bulbar, appendicular and respiratory).

Regarding statistical analysis, the categorical variables were described in absolute value and relative frequency, whereas the continuous variables were described through measures of central tendency, dispersion and position.

Linear correlations between the anthropometric indicators (BMI, body water, lean mass, fat mass and phase angle) and the scores obtained in the ALSFRS-R functionality scale (total score and in the domains) were plotted according to Pearson’s method. After that, linear regression analyzes, the average to verify the extent (β) of the correlation between these indicators and the scale score were performed. The analyzes were performed with the aid of the statistical package IBM SPSS version 20.0.Results with a probability of Type I error of less than 5% were considered as statistically significant.

Results

The sample consisted of 31 patients, 12 adults and 19 elderly. There was prevalence of males and in a median age of 61 years, ranging from 22 to 80 years. Body composition was evaluated without distinction of age.

More than two thirds of the patients (77.4%) presented the appendicular form of the disease, and approximately 10% of the patients presented familial origin.

The mean time from onset of symptoms to the time of evaluation was 32.4 months (8.4 – 86.4). The median ALSFRS-R score was 27.0 points (8–39). The respiratory domain had the highest median score, followed by the appendicular and bulbar domains.

Regarding weight loss, 80.6% of the patients reported weight loss from the onset of symptoms, of which 64% had a loss greater than 10% of the previous weight. The median body mass index was 22.6 kg / m2 (11.8 – 34.6 kg/m2) and approximately 45% of the patients were in the eutrophic range, according to the BMI classification.

The bio impedance method identified 30.9% of fat mass, 67.6% of lean mass and 30.4% of total body water in the studied sample. The phase angle, measured using the bio impedance method, averaged 3.9 degrees in women and 4.1 degrees in men.

Table 2 shows the correlation matrix between the anthropometric indicators and the scale score in the three different domains, in addition to the total score observed. In general, BMI and Phase Angle were the best indicators correlated with the scale scores. The BMI showed significant correlations (p <0.001), directly proportional, with the score in the bulbar and respiratory domains, in addition to the total score.

Table 1. Demographics of the study population

|

Subject |

N |

% |

|

Gender |

||

|

Male |

17 |

54, 8 |

|

Female |

14 |

45, 2 |

|

Age in years |

||

|

Average (min – max) |

61, 0 (22 – 80) |

|

|

Elderly (≥ 60 years) |

18 |

58, 1 |

|

Disease manifestation form |

||

|

Appendicular |

24 |

77, 4 |

|

Bulbar |

7 |

22, 6 |

|

Time of onset of symptoms (months) |

||

|

Average(min – max) |

32, 4 (8, 4 – 86, 4) |

|

|

ALSFRS-R, domains – average (min – max) |

||

|

Bulbar |

9, 0 (0 – 12) |

|

|

Appendicular |

9, 0 (0 – 20) |

|

|

Respiratory |

10, 0 (4 – 12) |

|

|

ALSFRS-R, total score – average (min – max) |

||

|

Total |

27 (8 – 39) |

|

|

Body mass index (kg/m²) – average (min – max) |

||

|

Male |

23, 0 (17, 6 – 32, 2) |

|

|

Female |

22, 9 (11, 8 – 32, 4) |

|

|

Fat mass– average (min – max) |

||

|

Male |

29, 2 (13, 7 – 43, 3) |

|

|

Female |

34, 2 (19, 2 – 55, 2) |

|

|

Lean mass –average (min – max) |

||

|

Male |

70, 7 (56, 7 – 86, 3) |

|

|

Female |

60, 6 (33, 7 – 74, 3) |

|

|

Total body water (L) – average (min – max) |

||

|

Male |

34, 9 (16 – 51, 4) |

|

|

Female |

27, 6 (18, 4 -35, 4) |

|

|

Phase angle (º) – average (min – max) |

||

|

Male |

4, 1 (2, 8 – 6) |

|

|

Female |

3, 9 (2, 4 – 6, 3) |

|

Table 2. Matrix of correlations between anthropometric indicators and the scores obtained on the ALSFRS-R scale.

|

ALSFRS-R |

||||

|

Subject |

Bulbar |

Appendicular |

Respiratory |

Total |

|

BMI (Kg/m2) |

0, 555** |

0, 169 |

0, 370** |

0, 492** |

|

Fat mass (%) |

-0, 045 |

-0, 129 |

-0, 065 |

-0, 141 |

|

Lean mass (%) |

-0, 024 |

0, 171 |

0, 014 |

0, 128 |

|

Body water (L) |

0, 367** |

0, 174 |

0, 335* |

0, 402** |

|

Phase angle (°) |

0, 152 |

0, 659*** |

0, 516*** |

0, 744*** |

|

*P<0, 10 |

||||

The phase angle showed significant correlations of at least moderate intensity (p <0.05), with the scores observed in the appendicular and respiratory domains of the scale, besides the total score obtained. The total body water measure also correlated positively with the bulbar domains and the total score. On the other hand, the indicators of body fat mass and lean mass did not show a significant correlation with the scale scores.

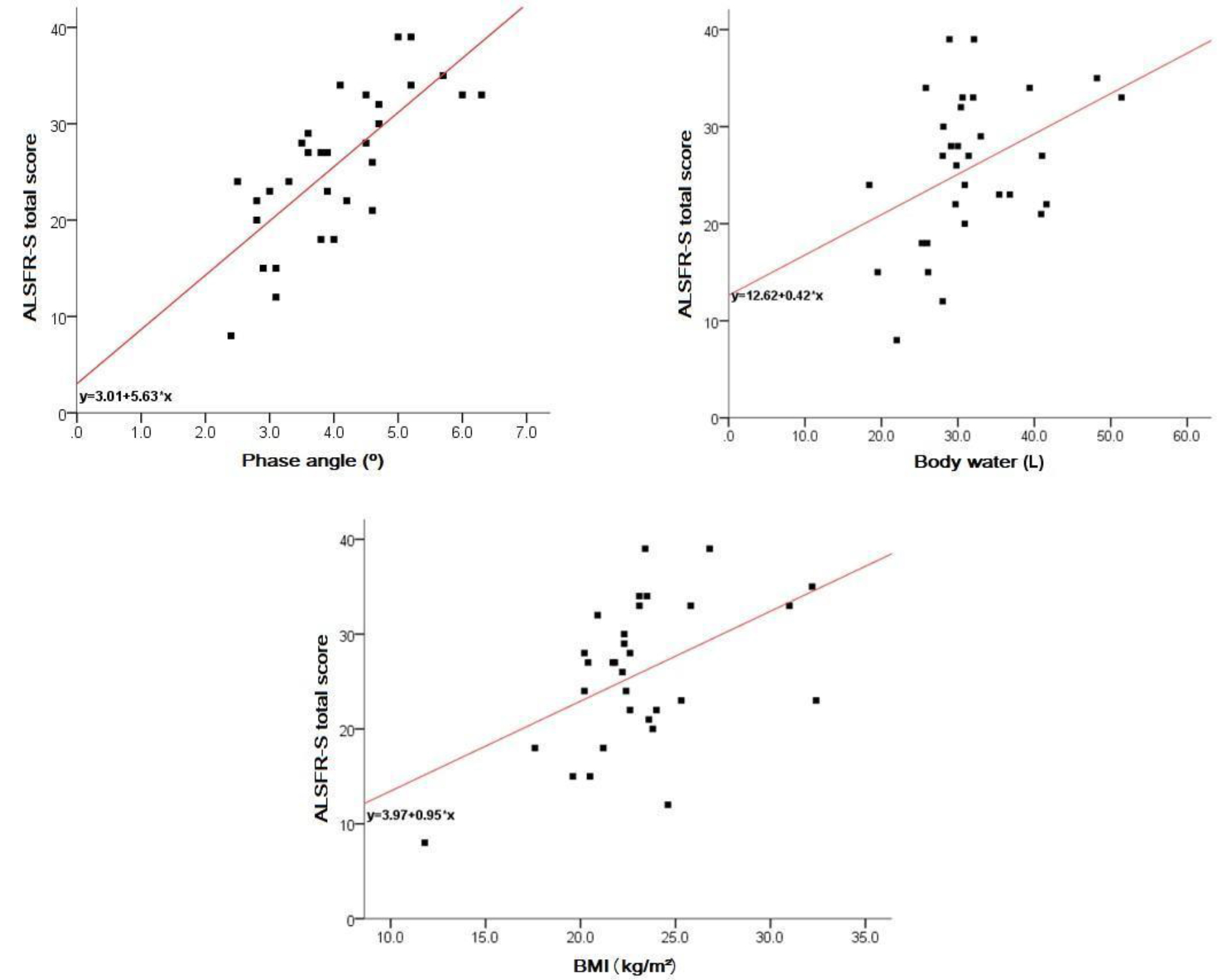

The results of the linear regression (Figure 1) point to an average increment of 5.63 (CI 95% 3.70 – 7.55) points in the scale at each degree measured in the phase angle. However, for each liter of total body water measured, there is an average increment of 0.42 (95% CI 0.05 – 0.75) points in the scale, and for each BMI unit, an average increase of approximately 0.95 (95% CI 0.31 – 1.58) points on the scale can be inferred.

Figure 1. Body composition x functionality

Discussion

The epidemiological and clinical characteristics observed in patients with MND in this study are in agreement with the evidence described in the literature [6]. Being a relatively rare disease, the sample studied is sufficient to represent changes in the body composition of patients with DNM [7]. Patients older than 60 years were considered elderly, since, according to the World Health Organization, this is the cut age for developing countries, in which Brazil fits in [8]. Variables that were not nutritional factors were used to characterize the sample, but were excluded from the analysis.

Most of the patients in this study, representing 75% of the sample, presented the appendicular form as manifestation of the disease. It can also be observed that, there was predominance of the sporadic form on the familial one, which represented approximately 10% of the patients, as described in the literature [9, 10].

Studies have observed that patients with MND often present marked weight loss from the onset of symptoms [11], and JAWAID et al. described that weight loss is a negative prognostic factor for patients with MND [12]. In this study, the majority of patients (80.6%) reported weight loss from the onset of clinical symptoms, with 64% of them presenting a marked loss greater than 10% of the previous weight. This condition can be attributed to the characteristic picture of dysphagia, decreased food intake, hyper metabolism and increased energy expenditure [13]. It was observed that, in the present study, dysphagia was present in 100% of the bulbar patients, and among the patients with appendicitis, bulbar involvement was not recurrent. However, it is suggested that the hyper catabolic state may begin before the clinical manifestation of the disease [14].

BMI can be used as a predictor of progression and survival [14]. Some studies have described an association between the change in BMI and the clinical course of the disease, and evidence that survival is better in overweight patients compared to eutrophic or low-weight patients [11, 14, 15]. Other studies have shown that changes in BMI in the first two years after diagnosis correlate significantly with survival, and with the rate of progression of motor symptoms [12]. This faces the present study, where the BMI of the evaluated patients demonstrated significant, directly proportional correlations with the full score of the functionality scale. On the other hand, authors observed that there was an increase in mortality in patients with a higher BMI (above 35), and suggest that obesity may be related to a more rapid progression of the disease with reasons not yet elucidated [13, 16].

Previous studies have observed that there is a decrease in body weight, BMI, lean mass, phase angle, and an increase in fat mass during the course of the disease, and that depletion of lean mass has a negative impact on functionality and such thing is a prognostic factor for the survival decrease [17–19]. Fat mass is associated with a better outcome of the disease [20]. Authors suggest that increased LDL / HDL cholesterol may be related to neuronal protection and increased survival [15, 18]. Regarding body water, in this present study, the measure of this variable was positively correlated with the bulbar domains and the total score of the ALSFRS-R scale. Thus, for each liter of total body water measured, there was an average increase of 0.42 (95% CI 0.05 to 0.75) in the scale.

This fact is in agreement with the literature, which attributes to hydration as one of the most sensitive factors of malnutrition, and that the phase angle can also be interpreted as an indicator of water distribution between the extra and intra-cellular compartment, and that the better the phase angle, the better the cell membrane integrity [20].

In patients with MND, there is a probable relationship between phase angle and malnutrition, since the alteration of this indicator was higher in malnourished patients than in eutrophic ones [4]. In a study involving patients with MND and phase angle, the authors showed that there was significant worsening of the phase angle in these, and the same suggests that the phase angle could be used as a severity index [3]. The literature also describes that BMI and phase angle are independently associated with survival, and do not correlate with each other. This fact was also observed in this present study.

The reference value for healthy population of the phase angle is approximately 6.5º +/- 1º for females, and 7.5º +/- 1, 1º for males [3]. In this study, the phase angle averaged 3, 9º in women, and 4, 1º in men, as those found in the literature in patients with MND, where the average phase angle for women was 3, 8º , and for men of 4, 5º [20].

Authors demonstrated that there was a decline of the ALSFRS-R scale in the first 5 years of diagnosis of the evaluated patients [21]. The same study also noted that the higher the rate of decline in ALSFRS-R, the lower the survival. Considering that the literature assigns a gravity index to the phase angle, it was observed that in this present study there was a relation between the scale of functionality and the phase angle. The phase angle presented significant correlations of at least moderate intensity with the scores observed in the appendicular and respiratory domains of the scale, in addition to the total score obtained. There is agreement of the relationship between the phase angle and the appendicular domain, considering that the caloric restriction exacerbates the motor symptoms [18]. The results of the linear regression point to an average increase of 5.63 (95% CI 3.70 – 7.55) points in the scale, to every degree measured in the phase angle. However, as it is a cross-sectional study, it was not possible to evaluate the association between phase angle, ALSFRS-R and survival.

Bio impedance is a simple and easy to apply method, but the use in clinical practice to evaluate patients with MND may present limitations and bias for some measures, since the corporal distribution of these patients may behave differently, [20] once there is a difference in the fat distribution, as well as hydration. Although bio impedance monitors body composition more fractionally, body weight assessment should be a priority, once it is from its variation and monitoring that nutritional intervention is guided, and that BMI at the time of diagnosis can be considered a factor prognosis [17]. It is essential that the care invested be interdisciplinary to ensure the optimization of the quality of life of these patients. Studies confirm that patients who receive care from a multiprofessional team tend to have better survival compared to those who are deprived of these care [9]. All things considered, monitoring of nutritional status becomes indispensable for a better course of the disease.

Final considerations

The nutritional status is directly related to disease progression, and the depletion of the body compartments influences the functionality of patients with MND. BMI is a prognostic indicator and should be used as monitoring during the course of the disease. ALSFRS-R provides data that allows monitoring the evolution of the disease in a generalized way and by domains, allowing a more sensitive and focused observation of the bulbar, motor and / or respiratory alterations resulting from the disease, guiding the professional conduct and treatment.

The evaluation of body composition provides information that aggregates in the individualization of the nutritional therapy. The phase angle is an excellent predictor of severity, and concomitant with the application of ALSFRS-R, it is possible to notice that the alteration of the body composition has a direct and negative impact on the functionality of these patients.

References

- Bastos AF, Orsini M, Machado D, Mello MP, Nader S (2011) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: one or multiple causes? Neurol Int 3: e4. [crossref]

- Silva LBC, Mourão LF, Silva AA, Lima NMFV, Almeida SR, et al. (2010) Effect of nutritional supplementation with milk whey proteins in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. Arq Neuro-Psiquiatr 68: 263–268. [crossref]

- Desport JC, Preux PM, Bouteloup-Demange C, Clavelou P, Beaufrère B, et al. (2003) Validation of bioelectrical impedance analysis in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am J Clin Nutr 77:1179–1185. [crossref]

- Desport JC, Marin B, Funalot BT, Preux PM, Couratier P (2008) Phase angle is a prognostic factor for survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 9: 273–278. [crossref]

- Brooks BR, Miller RG, Swash M, Munsat TL (2000) El Escorial revisited: reviserd criterial for the diagnosis of amyotroph lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord 1: 293–299. [crossref]

- Nieves JW, Gennings C, Factor-Litvak P, Hupf J, Singleton J, et al. (2016) Association Between Dietary Intake and Function in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. JAMA Neurol 73: 1425–1432. [crossref]

- Chiò A, Logroscino G, Traynor BJ, Collins J, Simeone JC, et al. (2013) Global epidemiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a systematic review of the published literature. Neuroepidemiology 41:118–130. [crossref]

- WHO (2002) Active Ageing-A Police Framework. A Contribution of the World Health Organization to the second United Nations World Assembly on Aging. Madrid, Spain.

- Phukan J, Hardiman O (2009) The management of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol 256: 176–186. [crossref]

- Leigh PN, Abrahams S, Al-Chalabi A, Ampong MA, Goldstein LH, et al. (2003) The management of motor neurone disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 74 Suppl 4: iv32–32iv47. [crossref]

- Shimizu T, Nagaoka U, Nakayama Y, Kawata A, Kugimoto C, et al. (2012) Reduction rate of body mass index predicts prognosis for survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A multicenter study in Japan. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 13: 363–366. [crossref]

- Jawaid L, Murthy SB, Wilson AM, Qureshi SU, Amro MJ, et al. (2010) A decrease in body mass index is associated with faster progression of motor symptoms and shorter survival in ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 11: 542–548. [crossref]

- Paganoni S, Deng J, Jaffa M, Cudkwicz ME, Wills AN (2011) Body mass index, not dyslipidemia, is an independent predictor of survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 44: 20–24. [crossref]

- O’reilly JE, Wang H, Weisskopf MG, Fitzgerald KC, Falcone G, et al. (2012) Premorbid body mass index and risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 14: 205–211. [crossref]

- Dorst J, Kühnlein P, Hendrich C, Kassubek J, Sperfeld AD, et al. (2011) Patients with elevated triglyceride and cholesterol serum levels have a prolonged survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol 258: 613–617. [crossref]

- Reich-Slotky R, Andrews J, Cheng B, Buchsbaum R, Leyv D, et al. (2013) Body mass index (BMI) as predictor of ALSFRS-R score decline in ALS patients. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 14: 212–216. [crossref]

- Marin B, Desport JC, Kajeu P, Jesus P, Nicolaud B, et al. (2010) Alteration of nutritional status at diagnosis is a prognostic factor for survival of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 82: 628–634. [crossref]

- Dupuis L, Corcia P, Fergani A, Aguilar JLG, Bonnefont-Rousselor D, et al. (2008) Dyslipidemia is a protective factor in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology 70: 1004–1009. [crossref]

- Dorst J, Cypionka J, Ludolph AC (2013) High-caloric food supplements in the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A prospective interventional study. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 14: 533–536. [crossref]

- Roubeau V, Blasco H, Maillot F, Corcia P, Praline J (2015) Nutritional Assessment of Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in routine practice: value of weighing and bioelectrical impedance analysis. Muscle Nerve 51: 479–484. [crossref]

- Gordon PH, Cheng B, Salachas F, Pradat PF, Bruneteau G, et al. (2010) Progression in ALS is not linear but is curvilinear. J Neurol 257: 1713–1717. [crossref]