Abstract

Introduction: Alternate splicing of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A gene yields a number of proteins of varying amino acid lengths ranging from 121 to 206 amino acids. Recently, other isoforms of VEGF have been recognized that form from alternate splicing of the C-terminal region of exon 8 of VEGF gene. These sister isoforms are known as VEGFxxxb, where xxx denotes the number of amino acids present in the protein. During human pregnancy, VEGF165 and its receptors are recognized as master regulator of placental angiogenesis; and both VEGF165 and VEGF165b proteins are secreted by cytotrophoblasts. The present study compares the temporal expression of both isoforms of VEGF in chorionic villi tissues, throughout gestation, in normal human pregnancy.

Methods: Placentas were obtained from elective termination of pregnancy or term delivery. Tissues collected were dissected in saline to identify chorionic villi without associated decidua. VEGF protein expressions were determined by ELISA using monoclonal antibody to human VEGF165 and VEGF165b proteins as capture antibody, DY293B and DY3045, respectively (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Non-parametric test considered p<0.05 as significant.

Results: Both isoforms of VEGF were detected in 166 chorionic villi samples analyzed. The expression patterns of the two proteins differed markedly throughout gestation. While VEGF165 showed a minor dip in the second trimester, VEGF165b showed a peak during that time. The two isoforms were positively and significantly correlated in second and third trimesters of pregnancy.

Conclusions: The data reveal that both isoforms of VEGF play key roles in regulating the angiogenic balance throughout gestation in normal human pregnancy. We hypothesize that VEGF165b protein expression in placental tissues could be a physiological phenomenon to restrain overexpression of VEGF165 during placental development, which if left unchecked, could lead to pregnancy-related complications as pregnancy advanced.

Keywords

ELISA, Throughout Gestation, Uncomplicated Human Pregnancy, VEGF165, VEGF165b

Introduction

Placental angiogenesis plays a pivotal role in instituting a fetomaternal circulation and in establishing the placental villous tree that contributes to the development of the placenta throughout human pregnancy. Of the many angiogenic factors that were investigated e.g., five members of VEGF family, four members of the angiopoitin family, and one member of large ephrin family; vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) was recognized as the one specific for blood vessel formation [1–3]. Gene knockout studies have provided convincing evidence for a central role of VEGF in fetal and placental angiogenesis. Targeted homozygous null mutations of VEGF receptors in mice demonstrated failure in hematopoiesis, formation of blood islands and blood vessels, resulting in embryonic death by day 8 of pregnancy [4]. Carmeliet et al. further demonstrated that loss of a single VEGF allele in a mouse model led to gross developmental deformities in vessel formation that resulted in embryonic death between day 11 and 12 of mouse pregnancy. The authors concluded that not only fetal and placental angiogenesis were dependent on VEGF, but a threshold level of VEGF had to be achieved for normal vascular development to occur [5].

The VEGF A gene has eight exons. Alternate splicing of VEGF mRNA accounts for five isoforms of VEGF proteins: VEGF121, VEGF145, VEGF165, VEGF189 and VEGF206, of which VEGF165 isoform is most abundant in vivo [6]. In the past decade, the complexity of VEGF165 biology further intensified when it was found that alternate splicing of exon 8 at the C-terminal region of VEGF gene could yield yet other isoforms of VEGF. While the number of amino acids in the sister isoforms remained the same, there were however alternate open reading frames of six amino acids at the C-terminal region of the sister isoforms. The sister isoforms were identified as VEGFxxxb, xxx referring to the number of amino acids present in the protein [7]. The splicing event modifies the C-terminal region of the VEGF protein from CDKPRR (VEGFxxx) to SLTRKD (VEGFXXXb). The replacement of the six amino acids alters the tertiary structure of the newly formed protein, as the disulfide bond that was previously formed between cysteine 160 at the C-terminal region with cysteine 146 of exon 7, could no longer be formed. The terminal two arginine molecules (RR) being replaced with lysine and aspartic acid (KD) further modifies the overall charge of the protein; and replacement of proline (P) residue with arginine (R) additionally transforms the structure of the C-terminal domain [7].

In a previous study, placental expressions of VEGF165 and VEGF165b were examined in which the comparison was made between uncomplicated and complicated pregnancies at term [8]. In an earlier study, we have examined placental expression of VEGF165b throughout gestation in normal human pregnancy [9]. The two growth factors of VEGF are secreted by cytotrophoblasts; and are implicated in placental angiogenesis in human pregnancy. We, therefore, undertook the present study to simultaneously investigate the expressions of both VEGF165 and VEGF165b in placental tissues, throughout gestation, in women with uncomplicated pregnancy. Understanding the simultaneous temporal changes in these two growth factors of VEGF as placenta develops, we consider, would be extremely valuable.

Materials and Methods

The investigative protocol for the study was approved by the Human Subject Ethics Committee of the BronxCare Health System, New York, protocol # 10101304. Discarded placental tissue samples were collected within approximately 30 minutes of the procedures from normal pregnant women who underwent elective termination of pregnancy at 6 weeks to 23 weeks and 6 days; and from normal women who delivered uncomplicated singleton pregnancies at term. Placentas from missed abortion or from pregnancies complicated with diabetes, hypertension, chronic renal disease, and chronic peripheral vascular disease or with major fetal anomalies were excluded. The approved protocol allowed the collection of the following clinical information regarding the women from whom placental tissues were obtained. These included: maternal age, parity, race/ethnicity (self-reported), gestational age (as determined by ultrasound or by initial date of the last menstrual period), reason for pregnancy termination (whether elective, for maternal medical reasons or for fetal indications), and medicine(s) administered to induce termination of pregnancy. Placentas from pregnancies 7- 23 weeks and 6 days were collected from the elective termination group, and those from 37 to 42 weeks of gestation were collected from term delivery group. Placentas delivered below 37 weeks of gestation were not included because these placentas are considered as preterm.

Soon after collection, the placental tissues were processed to obtain chorionic villi samples by a method described earlier [10]. Briefly, portions of each placenta were first thoroughly washed in cold saline to remove maternal blood and were then dissected in saline to collect free floating chorionic villi that were not anchored to the basal plate nor were emerging from the chorionic plate surface vessels. Pieces of these chorionic villi samples were placed in separate tubes, each tube bearing the same ID# designated for that placenta. Tissues and clinical information were de-identified before exiting the delivery suites. The sample collection tubes were then transported to the laboratory on ice and stored at -800C until assay.

Chorionic villi VEGF165 and VEGF165b protein expressions were simultaneously determined by enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) methods. The capture antibodies for the ELISA kits were monoclonal antibodies to human proteins VEGF165 (DY293B) and VEGF165b (DY3045), respectively (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Chorionic villi samples were homogenized in Reagent Diluent 2 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), and supernatants following centrifugation of the homogenate at 13000 rpm for 2 minutes were used to determine the free forms of the isoforms based on the manufacturer’s protocols. Simultaneous analysis of both VEGF isoforms meant that we carried out both VEGF165 and VEGF165b proteins assays using chorionic villi tissues samples isolated from the same placentas, the assays were not carried out using the same aliquots. A Tecan infinite 200 Pro microplate reader (Tecan Systems Inc., San Jose, CA) set at 450 nm with wavelength correction set at 540 nm was used to measure absorbance. The sensitivity of VEGF165 ELISA was 31.3 pg/ml and that of VEGF165b ELISA was 62.5 pg/ml. Intra-assay and inter-assay variations for both assay kits were between 7–10%.

Statistical Analyses

The statistical software package SPSS, version 25 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) was used for statistical analyses. First, the normality of the data was statistically analyzed which showed that the data was not normally distributed. Hence, non-parametric statistics were applied. The data was grouped by trimesters and the following non-parametric tests were performed: 1) Kruskal Wallis test (an alternative test to One-Way-ANOVA) was used to explore the differences in VEGF isoform expressions among the trimester groups. (It is important to note that KW test does not provide post–hoc data the way one-way-ANOVA does). 2) The non-parametric Mann Whitney U test was applied to compare two trimester groups at a time against each other. 3) Spearman Rank correlation coefficient test was applied to summarize the strength and direction of a relationship between the variables as well as between the variables and gestational age in days. A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The demographic characteristics of women from whom placental samples were obtained showed comparable maternal age among the three trimester groups (28.2 ± 6.5, 28.2 ± 6.1 and 30.0 ± 6.8 years, for first, second and third trimester groups, respectively). Race/ethnicity was self-reported, and the distribution pattern was 30% Black, 60% Hispanic, 2% Caucasian and 8% of other ethnic origin. When 166 placentas were grouped by trimester the data showed that 71 placentas collected from elective termination of pregnancy were in the first trimester, with an average gestational age of 8 weeks; 33 placentas collected also from elective termination of pregnancy were in the second trimester, with an average gestational age of 16 weeks; and 62 placentas collected from term delivery were from third trimester, with an average gestational age of 39 weeks and 2 days.

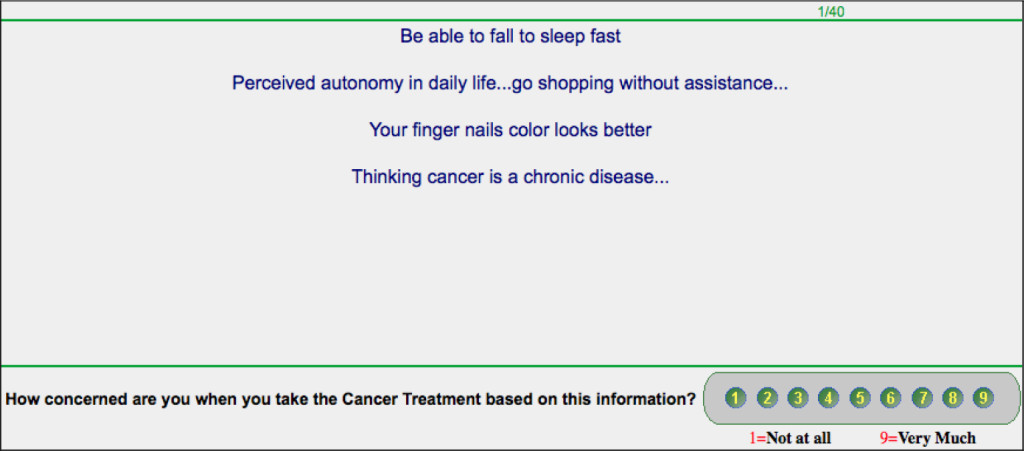

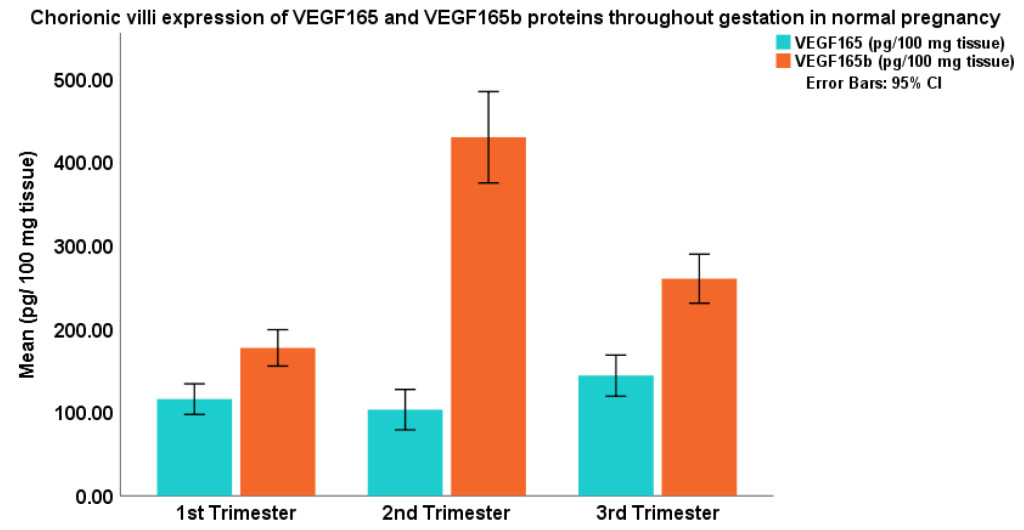

In this study, non-parametric statistics were applied because the data were skewed. Kruskal Wallis test results revealed that VEGF165 protein expression was not statistically different among the three trimester groups, the expression of VEGF165b protein, however, was significantly different (p=0.0001). In (Table 1) the 25th, 50th and 75th percentile values of the two VEGF isoforms are shown. The expression patterns of the two proteins are shown graphically in (Figure 1), which depicts two entirely different expression patterns for the two isoforms of VEGF throughout gestation in normal human pregnancy. While VEGF165 protein showed a minor dip in the second trimester of pregnancy, the expression patterns of VEGF165b showed a significant peak during that time. Pairwise comparison of trimester groups using Mann Whitney U test further revealed that the expression pattern of VEGF165 was not significantly different, but VEGF165b protein expression in each trimester was significantly different from the other (p=0.0001).

Table 1. Chorionic villi VEGF Protein Expressions throughout Gestation in Normal Pregnancy

|

Groups |

N |

VEGF165 (pg/ 100 mg tissue) |

VEGF165b (pg/100 mg tissue) |

||||

|

25th Percentile |

50th Percentile |

75th Percentile |

25th Percentile |

50th Percentile |

75th Percentile |

||

|

1st Trimester |

71 |

68.00 |

87.45 |

147.30 |

122.06 |

166.51 |

240.00 |

|

2nd Trimester |

33 |

50.80 |

68.40 |

148.10 |

297.42 |

428.97 |

529.66 |

|

3rd Trimester |

62 |

77.25 |

110.95 |

212.80 |

175.09 |

256.52 |

344.98 |

VEGF165 : Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor165 ; VEGF165b: Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor165b; GA: gestational age in days. The first trimester placental chorionic villi samples were from 70/7–120/7 weeks gestation, the average GA was 81/7 weeks; second trimester were from 121/7 to 236/7 weeks, the average GA was 160/7 weeks; and the third trimester term were from 370/7 to 414/7 weeks of gestation, the average GA 392/7 weeks. Homogenized human placental chorionic villi samples were analyzed using assay kit from R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN; to determine VEGF165 and VEGF165b protein expressions. Data were not normally distributed hence non-parametric statistics were used and 25th, 50th and 75th percentile values of VEGF165 and VEGF165b are shown.

Figure 1. GA: gestational age.

The first trimester placental chorionic villi samples were from 70/7-120/7 weeks gestation, the average GA was 81/7 weeks; second trimester were from 121/7 to 236/7 weeks, the average GA was 160/7 weeks; and the third trimester term were from 370/7 to 414/7 weeks of gestation, the average GA 392/7 weeks.

Correlation between the two proteins of VEGF as well as between the isoforms of VEGF and gestational age were examined in this study. Spearman’s correlation test results revealed that expression of VEGF165b protein was significantly and positively correlated with gestational age in days in the first trimester of normal pregnancy (r= +0.299, p=0.011, (Table 2). The table also depicts the test results of Spearman’s correlation between the two isoforms. The data reveal a significant positive correlation in the second (r = +0.376, p=0.031) and third trimester (r=+0.271, p=0.033), of normal pregnancy.

Table 2. Correlation between VEGF165, VEGF165b and Gestational Age in Days throughout gestation

|

VEGF165 |

VEGF165b |

|||

|

First Trimester |

VEGF165

|

Correlation |

1.000

|

0.070 |

|

GA |

Correlation |

0.029 |

0.299* |

|

|

SecondTrimester |

VEGF165 |

Correlation |

1.000 |

0.376* |

|

GA |

Correlation |

-0.149 |

0.013 |

|

|

Third Trimester |

VEGF165 |

Correlation |

1.000 |

0.271* |

|

GA |

Correlation |

-0.027 |

-0.112 |

|

VEGF165 : Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor165 ; VEGF165b: Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor165b; GA: gestational age in days. Data were not normally distributed hence Spearman’s correlation was applied. Significant positive correlation was seen between VEGF165b and GA in the first trimester of pregnancy. The two VEGF proteins were significantly and positively correlated in the second and third trimester of normal pregnancy.

Conclusion

In this study, chorionic villi samples were isolated from each placenta, and VEGF165 and VEGF165b protein expressions were determined by ELISA that used monoclonal antibody to human VEGF165 or VEGF165b protein as the capture antibody in each case. VEGF protein expression and that of its receptors are closely regulated to times of vasculogenesis and angiogenesis [11]. In this study, both isoforms of VEGF proteins were identified in all 166 chorionic villi samples that were analyzed suggesting that both proteins of VEGF may exert regulatory roles in pregnancy-linked angiogenesis in normal human pregnancy.

The angiogenic potential of VEGF165 has been confirmed by several bioassays that measured VEGF receptor expression during embryogenesis and tissue repair [11], capillary growth in vivo in developing chick chorioallantonic membrane [12], and a temporal and spatial correlation between VEGF and ocular angiogenesis in a primate model [13]. These studies affirmed VEGF signaling pathways to be the master regulator of angiogenesis [11–14]. The pro-angiogenic potential of VEGF165 results from six amino acids at its C-terminus e.g., CDKPRR [7, 15]. Involvement of VEGF165 in human pregnancy, particularly in placental development has also been recognized. Reports on the placental expressions of VEGF165 protein state that the protein increases in first 10 weeks of normal pregnancy, but as pregnancy advances, VEGF and its receptor VEGFR-2 concentrations decline. In these reports, VEGF was suggested to increase vascular permeability, vasodilation and angiogenesis [16–18]. It is also suggested to be involved in the formation and maintenance of the trophoblastic plugs that block the spiral arteries in the first trimester of normal pregnancy [19]. Figure 1 depicts that VEGF165 protein expression is somewhat lower in the second trimester of normal pregnancy. This data is consistent with the finding of an immunohistochemical study that reported VEGF165 antigen staining to be weaker in mid-gestational placental tissues, compared to the intensity of staining for the protein in the first or third trimester placental samples [20].

The isoform VEGF165b has not been investigated in as much detail as VEGF165. VEGF165b protein is expressed in normal tissues of lung, pancreas, colon, skin and brain [7, 21, 22]. Reports reveal that VEGF165b constitute 50% or more of total VEGF expressed in most non-angiogenic tissue [23]. Investigators have alleged that VEGF165b is not pro-angiogenic in vivo [23] and it actively inhibits VEGF165 mediated endothelial cell proliferation and migration in vitro [4, 7, 21–23]. VEGF165b is further reported to inhibit physiological angiogenesis in developing mammary tissue, in transgenic animals, overexpressing VEGF165b [24]. Moreover, VEGF165b is reported to inhibit angiogenesis in vivo in six other different tumor models [21–25]. The results of the present study on chorionic villi VEGF165b protein expression throughout gestation in normal human pregnancy are similar to the results we have reported earlier [9]. Our studies underscore the importance of VEGF165b antigen in normal human pregnancy. Identification of VEGF165b protein in this study, in all 166 chorionic villi samples that were collected throughout all trimesters of human pregnancy validates this notion. This temporal variation in VEGF165b protein in human pregnancy perhaps reflects that VEGF165b protein expression is more stringently controlled at each phase of human gestation, and that the isoform may play a more active role in placental development. The spatial activation of VEGF165b protein at various phases of human gestation as seen in the study emphasizes that placental angiogenesis could be more dependent on VEGF165b isoform.

VEGFR-2 is the predominant signaling receptor for VEGF-mediated angiogenesis [26]. Phosphorylation of VEGFR-2 on tyrosine residue at 1052 position of the molecule generates a highly dynamic and complex signaling system that triggers angiogenic response [4, 21, 26]. The binding affinities of VEGFR-2 are identical between VEGF165 and VEGF165b isoforms. However, VEGF165b is less efficient than VEGF165 in inducing phosphorylation on Y1052 residue [27]. The lower ability of VEGF165b to induce VEGFR2 phosphorylation on Y1052 is due to its incapacity to induce optimal rotation of the intracellular domain of the receptor molecule that is required for phosphorylation to occur [27]. Reduced Y1052 phosphorylation induces rapid inactivation of the kinase domains of the receptors resulting in weak activation of the signaling pathways [23]. Recent studies have shown that VEGF165b can stimulate VEGFR-2, ERK1/2 and Akt phosphorylation in endothelial cells, however, the induced phosphorylation is weaker than that promoted by VEGF165 [21, 28]. VEGF165b is currently not considered as anti-angiogenic but as a weakly angiogenic form of VEGF [28].

Establishment of functional fetal and placental circulations is some of the earliest strategic events during embryonic/placental development [29, 30]. The significant positive correlation seen between chorionic villi VEGF165b protein expression and gestational age in first trimester of pregnancy in this study (Table 2) suggests that VEGF165b may contribute to the development of villous vascular network in early pregnancy. An increase in expression of plasma VEGF165b protein in first trimester of normal pregnancy has been reported by other investigators, and the authors suggest that failure in the upregulation of VEGF165b protein in the plasma in the first trimester of pregnancy was a predictive marker of preeclampsia [31]. Simultaneous increase of both isoforms of VEGF in human placental tissues in the third trimester of pregnancy has also been reported by other investigators [8]. The large increase in transplacental exchange which supports the exponential increase in fetal growth and uterine blood flow during the last half of gestation is suggested to depend primarily on the dramatic growth of placental vascular beds [32]. Vascular density of the placental cotyledons remains relatively constant throughout mid-gestation and increases dramatically during the last third of gestation in association with dramatic fetal growth [32, 33]. In third trimester of normal pregnancy, both fetal development and demands are at its peak; and our data show a positive correlation between VEGF165 and VEGF165b during this time. Hence, it may be suggested that angiogenic modification of placental vasculature that allows maximum blood to flow through may depend on the synergistic action of both isoforms of VEGF.

Our present findings suggest a notable difference between tumor and placental angiogenesis. It is widely reported that in human tumors, up-regulation of VEGF165 protein occurs with a proportional drop in VEGF165b levels; indicating that in tumor angiogenesis the balance between the two isoforms of VEGF is lost [34]. However, the findings of the present study suggest that gestational age-specific expression of both VEGF isoforms is necessary for optimal placental angiogenesis and growth to results in a successful viable outcome.

That hypoxic environment favors VEGF165-induced angiogenesis and tumorigenic growth is well known [35]. In an earlier study we have demonstrated that placental environment switches from a hypoxic to a normoxic environment beyond the first trimester of normal human pregnancy [36]. We hypothesize that perhaps during this transitional period from first to second trimester of normal pregnancy, placental oxidative environment per se regulate the alternate splicing of exon 8 of the VEGF gene. In hypoxic condition proximal splicing of exon 8 may be favored, which up-regulates the expression of VEGF165 protein. In a normoxic state, distal splicing of exon 8 may be favored, whereby the expression of VEGF165b protein gets up-regulated. That switch in the partial pressure of oxygen at the end of first trimester of normal pregnancy can modify the expression pattern of two proteins has been reported earlier, between placental derived growth factor and VEGF [37]. It is feasible that this switch in the spliceosome at the end of the first trimester may be the contributing factor that may have resulted in the peak VEGF165b protein expression seen in the second trimester of this study. It is likely that this dependence of placental growth on VEGF165b beyond the first trimester could be a physiological phenomenon to restrain any overexpression of VEGF165 which if left un-checked, could perhaps lead to pregnancy-related complications as pregnancy advanced.

The limitation of our study is that we have not confirmed our data by western blot, polymerase chain reaction or by immunohistochemical methods. We acknowledge that cells respond to extracellular stimuli through a series of signaling cascades. When a receptor is activated, varieties of proteins are recruited to interact with each other to generate a cascade of sequential steps that result in a biological effect [38]. Signaling molecules are common to several pathways and often form a complex intracellular network [38]. Yet, in this study we have not examined other isoforms of VEGF, their receptors or other factors that may have also been involved in placental angiogenesis. We believe that addition of all these factors would have made the study more complex and any conclusions drawn from the study would have been extremely difficult to interpret. The strength of our study is our relatively larger sample size in each of the trimester groups. Simultaneous expressions of these two important VEGF proteins in human chorionic villi tissue throughout gestation in normal human pregnancy have not been reported before. In this study, stringent ELISA methods using monoclonal antibodies to human VEGF165 and VEGF165b human proteins were used as capture antibodies. The manufacturer claims that DY293B capture antibody that was used does not cross react with placental growth factor (PIGF), VEGF-B167, VEGF-B186, VEGF-C, VEGF-D, recombinant (rh) human VEGF R1(Flt-1)/Fc Chimera or with rhVEGF R2(KDR)/Fc Chimeras. Similarly, the monoclonal capture antibody DY3045 does not cross react with rhhuman VEGF121, VEGF162, VEGF165, rhVEGF R3/Fc, VEGF R1/Fc or VEGF R-2/Fc Chimeras. Furthermore, the detection methods used were sensitive, allowing the detection of VEGF165 as low as 31.2 and VEGF165b as low as 62.5 pg/ml, respectively. The study underscores the importance of VEGF165b in placental angiogenesis in normal human pregnancy. We speculate that placental oxidative environment might influence the C-terminal VEGF angiogenic switch, whereby different VEGF variants could be formed from a single VEGF gene; that play key roles in regulating angiogenic balance during normal human pregnancy. It may be suggested that gestational age-specific expression of both VEGF165 and VEGF165b isoforms may be necessary for a successful viable outcome.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr. CM Salafia for her guidance for the study, and the staff members of the Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology at BronxCare Health System for their support. For this research, outside grants were not sought. The study was funded by the Residency Program of the BronxCare Health System.

Declaration of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ferrara N (1999) Vascular endothelial growth factor: molecular and biological aspects. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 237: 1–30.

- Dvorak HE, Nagy JA, Feng D, Brown LF, Dvorak AM (1999) Vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor and the significance of microvascular hyperpermeability in angiogenesis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 237: 97–132.

- Eriksson U, Alitalo K (1999) Structure, expression and receptor-binding properties of novel vascular endothelial growth factors. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 237: 41–57.

- Mustonen T, Alitalo K (1995) Endothelial receptor tyrosine kinases involved in angiogenesis. J Cell Biol 129: 895–898.

- Carmeliet P, Ferreira V, Breier G, Pollefeyt S, Kieckens L, et al. (1996) Abnormal blood vessel development and lethality in embryos lacking a single VEGF allele. Nature 380: 435–439.

- Tischer E, Mitchell R, Hartman T, Silva M, Gospodarowicz D, et al. (1991) The human gene for vascular endothelial growth factor. Multiple protein forms are encoded through alternative exon splicing. J Biol Chem 266: 11947–11954.

- Bates DO, Cui TG, Doughty JM, Winkler M, Sugiono M, et al. (2002) VEGF165b, an inhibitory splice variant of vascular endothelial growth factor, is down-regulated in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res 62: 4123–4131.

- Bates DO, MacMillan PP, Manjaly JG, Qiu Y, Hudson SJ, et al. (2006) The endogenous anti-angiogenic family of splice variants of VEGF, VEGFxxxb, are down-regulated in pre-eclamptic placentae at term. Clin Sci (Lond) 110: 575–585.

- Basu J, Seeraj V, Gonzalez S, Salafia CM, Mishra A, et al. (2017) Vascular endothelial growth factor165b protein expression in the placenta of women with uncomplicated pregnancy. J Clin Obstet Gynecol Infertility 1: 1–6.

- Basu J, Agamasu E, Bendek B, Salafia CM, Mishra A, et al. (2018) Correlation between placental matrix metalloproteinase-9 and tumor necrosis factor-α protein expression throughout gestation in normal human pregnancy. Reprod Sci. 25: 621–627.

- Peters KG, DeVries C, Williams LT (1993) Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor expression during embryogenesis and tissue repair suggests a role in endothelial differentiation and blood vessel growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci 90: 8915–8919.

- Ausprunk DH, Knighton DR, Folkman J (1974) Differentiation of vascular endothelium in the chick chorioallantois: a structural and autoradiographic study. Dev Biol 38: 237–248.

- Miller JW, Adamis AP, Shima DT, D’Amore PA, Moulton RS, et al. (1994) Vascular endothelial growth factor/ vascular permeability factor is temporally and spatially correlated with ocular angiogenesis in a primate model. Am J Path 145: 574–584.

- Ribatti D, Crivellato E (2012) “Sprouting angiogenesis”, a reappraisal. Dev Biol 372: 157–165.

- Keyt BA, Berleau LT, Nguyen HV, Chen H, Heinsohn H, et al. (1996) The carboxyl-terminal domain (111–165) of vascular endothelial growth factor is critical for its mitogenic potency. J Biol Chem 271: 7788–7795.

- Vuckovic M, Ponting J, Terman BI, Niketic V, Seif MW, et al. (1996) Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, KDR, in human placenta. J Anat 188: 361–366.

- Cooper JC, Sharkey AM, Charnock-Jones DS, Palmer CR, Smith SK (1996) VEGF mRNA levels in placentae from pregnancies complicated by pre-eclampsia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 103: 1191–1196.

- Shiraishi S, Nakagawa K, Kinukawa N, Nakano H, Sueishi K (1996) Immunohistochemical localization of vascular endothelial growth factor in the human placenta. Placenta 17: 111–121.

- Alfaidy N, Hoffmann P, Boufettal H, Samouh N, Aboussaouira T, et al. (2014)The multiple roles of EG-VEGF/Prok1 in normal and pathological placental angiogenesis. BioMed Res Int 2014, Article ID 451906.

- Jackson MR, Carney EW, Lye SJ, Ritchie JW (1994) Localization of two angiogenic growth factors (PDECGF and VEGF) in human placenta throughout gestation. Placenta 15: 341–353.

- Qiu Y, Hoareau-Aveilla C, Oltean S, Harper SJ, Bates DO (2009) The anti-angiogenic isoforms of VEGF in health and disease. Biochem Soc Trans 37: 1207–1213.

- Bates DO, Harper SJ (2005) Therapeutic potential of inhibitory VEGF splice variants. Future Oncol 1: 467–473.

- Woolard J, Wang WY, Bevan HS, Qiu Y, Morbidelli L, et al. (2004) VEGF165b, an inhibitory vascular endothelial growth factor splice variant: mechanism of action, in vivo effect on angiogenesis and endogenous protein expression. Cancer Res 64: 7822–7835.

- Qiu Y, Bevan HS, Weeraperuma S, Wratting D, Murphy D, et al. (2008) Mammary alveolar development during lactation is inhibited by the endogenous anti-angiogenic growth factor isoform VEGF165b. The FASEB J 22: 1104–1112.

- Varey AH, Rennel ES, Qiu Y, Bevan HS, Perrin RM, et al. (2008) VEGF165b, an antiangiogenic VEGF-A isoform, binds and inhibits bevacizumab treatment in experimental colorectal carcinoma: balance of pro-and antiangiogenic VEGF-A isoforms has implications for therapy. Br J Cancer 98: 1366–1379.

- Rahimi N, Costello CE (2015) Emerging roles of post-translational modifications in signal transduction and angiogenesis. Proteomics 15: 300–309.

- Kawamura H, Li X, Harper SJ, Bates DO, Claesson-Welsh L (2008) Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGF)-A165b is a weak in vitro agonist for VEGF receptor-2 due to lack of coreceptor binding and deficient regulation of kinase activity. Cancer Res 68: 4683–4692.

- Catena R, Larzabal L, Larrayoz M, Molina E, Hermida J, et al. (2010) VEGF121b and VEGF165b are weakly angiogenic isoforms of VEGF-A. Mol Cancer 9: 320.

- Ramsey EM (1982) The placenta, human and animal. New York: Praeger.

- Patten BM (1964) Foundations of embryology, 2nd (edn). New York: McGraw-Hills.

- Bills VL, Varet J, Millar A, Harper SJ, Soothill PW, Bates DO (2009) Failure to up-regulate VEGF165b in maternal plasma is a first trimester predictive marker for pre-eclampsia. Clin Sci 116: 265–272.

- Reynolds LP, Redmer DA (1995) Utero-placental vascular development and placental functions. J Anim Sci 73: 1839–1851.

- Kaufmann P, Mayhew TM, Charnock-Jones DS (2004) Aspects of human fetoplacental vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. II. Changes during normal pregnancy. Placenta 25: 114–126.

- Peiris-Pagès M (2012) The role of VEGF165b in pathophysiology. Cell Adh Migr 6: 561–568.

- Cao Y, Linden P, Shima D, Browne F, Folkman J (1996) In vivo angiogenic activity and hypoxia induction of heterodimers of placenta growth factor/vascular endothelial growth factor. J Clin Invest 98: 2507–2511.

- Basu J, Bendek B, Agamasu E, Salafia CM, Mishra A, et al. (2015) Placental oxidative status throughout normal gestation in women with uncomplicated pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol Int 276095: 1–6.

- Ahmed A, Dunk C, Ahmad A, Khaliq A (2000) Regulation of placental vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and placenta growth factor (PLGF) and soluble Flt-1 by oxygen—A review. Placenta 21: 16-S24.

- Ferretti C, Bruni L, Dangles-Marie V, Pecking AP, Bellet D (2007) Molecular circuits shared by placental and cancer cells, and their implications in the proliferative, invasive and migratory capacities of trophoblasts. Human Reprod Update 13: 121–141.