DOI: 10.31038/CST.2018344

Abstract

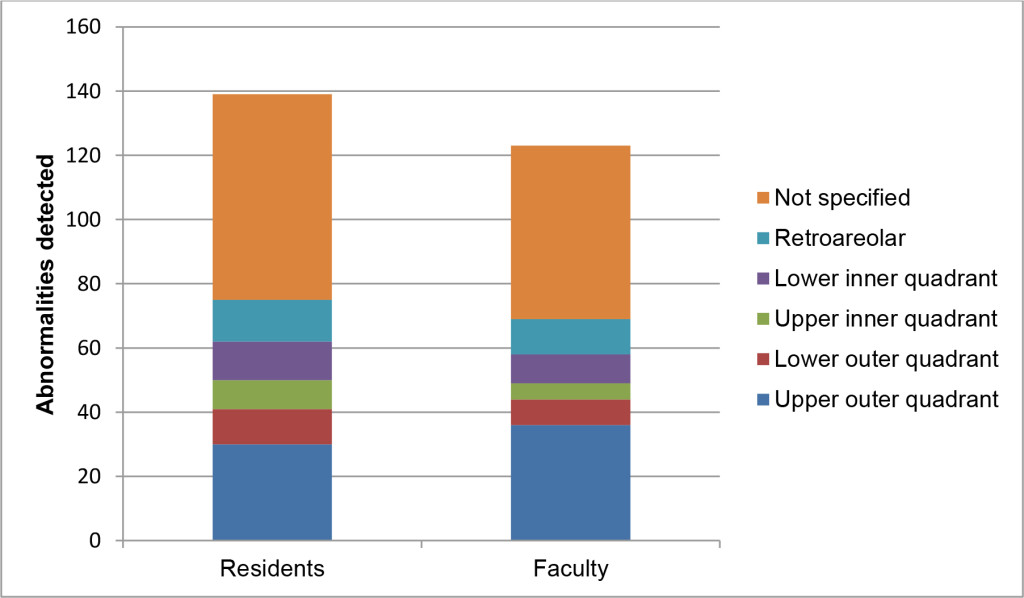

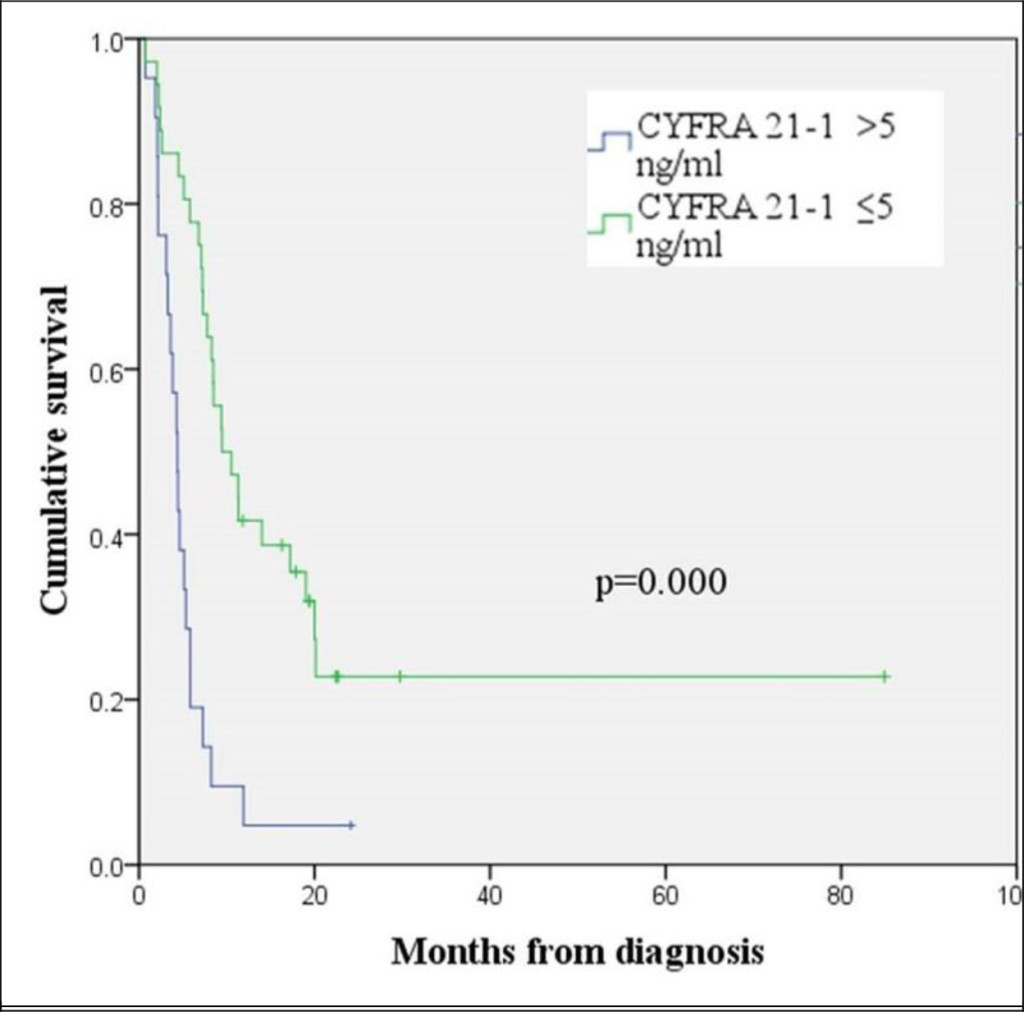

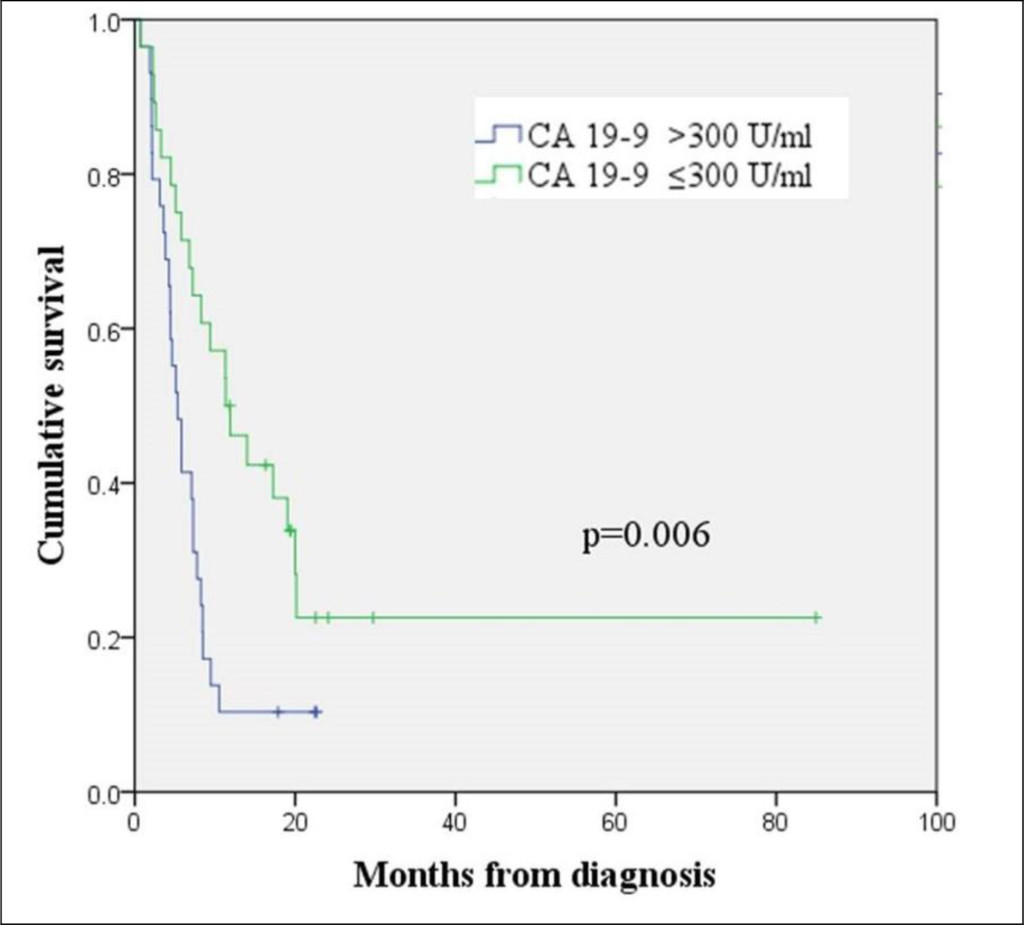

Colon cancer is the third most common diagnosed cancer for men and women in the United States. Colonoscopy remains the best diagnostic tool for the detection of colon cancer as well as adenomatous polyps. Adenoma Detection Reate has been directly linked to prep quality, colonoscopy withdrawal time and physician feedback on competency. Recently several endoscopic devices, endoscopes and techniques have been introduced to increase individual ADR. Endoscopes that increase mucosal visualization include wide-angle colonoscopes, multiple lense colonoscopes and short turn radius colonoscopes. Accessory devices include transparent caps, endocuff, and endorings among others. Finally, these products can be augmented by having a trained technician acting as a second observer during colonoscopy. Aim: To determine if a trained technician can augment polyp detection rates as a second observer. Methods: A prospective, non-randomized, pilot study was conducted on 1681 patients undergoing surveillance colonoscopy of patients with prior history of colon polyps. Consecutive patients were performed by Standard Colonoscopy; n = 765 (m = 317, f = 448) Group I, followed by Observer Augment Colonoscopy; n = 916 (m = 392, f = 524) Group II. Data collected included prep quality (Boston Criteria), withdrawal time (WT), ADR, number of Adenomas/patient, polyp location, polyp size and advanced polyp histology. Results: ADR rates was significantly higher in Observer Augmented Colonoscopy compared to Standard Colonoscopy (41.8% vs. 37.6%, p = 0.008). Average number of polyps per patient detected by Observer Augmented Colonoscopy was 2.32/patient compared to 1.85/patient in the Standard Colonoscopy group (p = 0.001). Seventy-eight % of the augmented polyps removed were flat and 5mm or less and 42% were found in the sigmoid colon. Absolute benefit increase and Relative benefit increase was 4.2% and 11.2% respectively. No differences in prep quality or withdrawal time were observed. Conclusion: Observer Augmented Colonoscopy results in significantly higher ADR compared to Standard Colonoscopy. It also results in greater average number polyps found per individual patient most often observed in the sigmoid colon. We strongly recommend training assistants to be vigilant observers during colonoscopy. A prospective, multi-centered, randomized study is currently underway.

Keywords

Colonoscopy, Colon Cancer, Polyp, Colon Cancer Screening, Adenoma Detection Rate (ADR)

Background

Cancer is the second leading cause of death after heart diseases [1]. Colonoscopy is a widely used gold standard tool for colorectal screening and can help detect both standard and advanced colonic neoplasms in asymptomatic adults [2–6]. Several studies have demonstrated that experienced gastroenterologists miss up to 11% of advanced adenomas and 26% of all adenomas [7]. Interval colon cancer is increasingly being reported, predominately as a result of missed polyps on prior colonoscopy and reflects strongly on quality of the exam.

Removal of adenoma is considered the most effective method in reducing the incidence of mortality of CRC and warrants the success of colonoscopy as a screening procedure [3, 4, 8]. One of the benchmarks of quality colonoscopy is Adenoma Detection Rates (ADR). The ADR and Polyp Detection Rate (PDR), defined as the proportion of colonoscopies in which one or more adenomas (or polyp) are detected, are both considered as an outcomes measure for colonoscopy [5, 9]. Factors that improve polyp and adenoma detection include prolonged colonoscopy withdrawal time, improved quality of the bowel preparation, and instrument accessories such as the application of a cap-assisted colonoscopy, and the third eye retro-scope [10–14]. Recent advances have shown improved polyp detection when additional trained individuals are monitoring for polyps by concentrating on the screen throughout length of the exam [15–17]. A study done on 844 patients in Korea by Lee et al.[18] in 2011 demonstrated that endoscopy nurse participation increased ADR, however, the benefit was exclusively with inexperienced endoscopists and nurses with ≥ 2 years endoscopy experience. A randomized prospective study done at Yale University including 502 patients showed a trend toward improved overall ADR with endoscopy nurse observation during colonoscopy [19]. Nurses in this study by

Aslanian et al. 2013 had ≥ 1.5 years of prior endoscopy experience. A meta-analysis by Y.S Oh et al [20] concluded that involvement of a fellow during colonoscopy did not affect adenoma and polyp detection rates. Our aim was to further determine if observer augmented colonoscopy by an experienced endoscopy technician improves ADR versus standard colonoscopy.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a prospective, non-randomized feasibility study to determine the merits of a large scale prospective study the study was approved by institutional review board. Written informed consent for the study was obtained from all patients. A total of 1681 patients undergoing surveillance colonoscopy of patients with prior history of colon polyps were included in the study. This included 765 consecutive patients with standard colonoscopy followed by 916 patients using augmented vigilance. Those with a diagnosis of colon cancer were excluded from analysis. Bowel preparation quality, withdrawal time, ADR, number of adenomas per patient, polyp location, size and polyp histology were prospectively recorded by the endoscopist. Endoscopy technicians at each site were educated to detect polyps by monitoring the endoscopy screen throughout the exam insertion and withdrawal. Each technician had a minimum of 3 years’ experience assisting in colonoscopy. A minimum requirement for bowel preparation was Boston score of 6, with each segment having a minimal score of 2. Polyps overlooked by the endoscopist and noted by the technician were removed and the procedure was flagged for final interpretation. A missed polyp by the endoscopist was credited to the endoscopy technician upon withdrawal if no attempt was made to stop the colonoscopy to target for removal.

Results

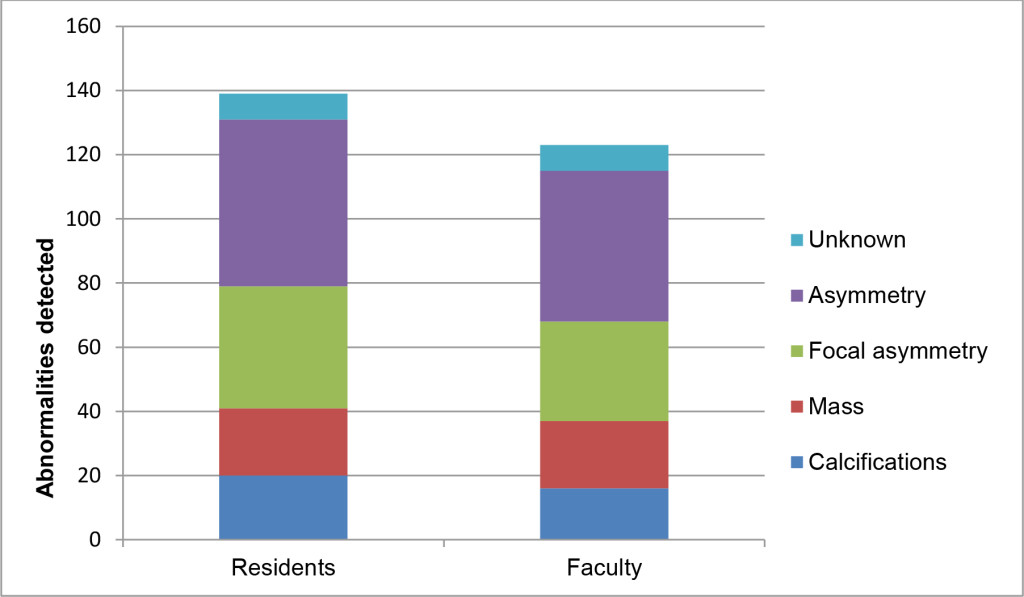

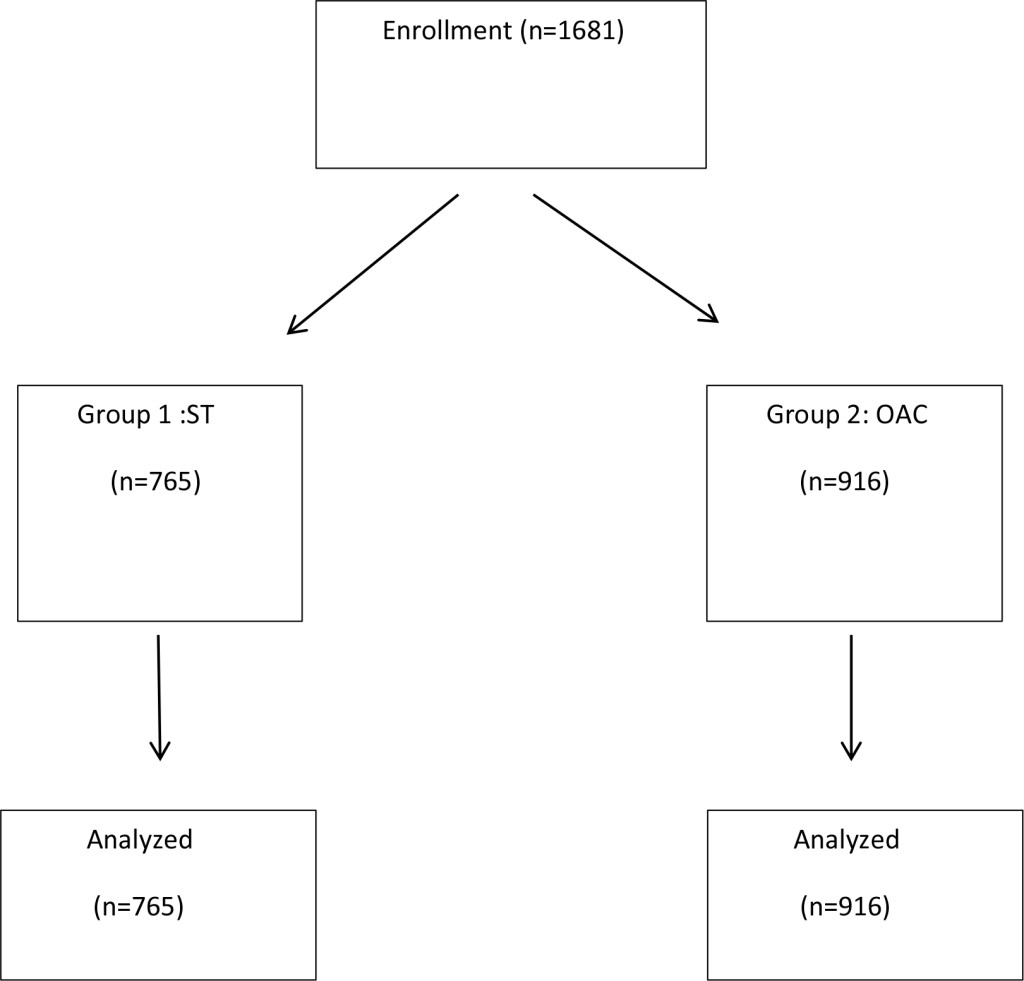

Figure 1 shows a flow diagram of the study. In total 1681 patients were included in the study. Patients were randomized to Standard Colonoscopy (ST) n = 765 (male = 317, female = 448) Group 1, or to Observer Augmented Colonoscopy (OAC) n = 916 (male = 392, female = 524 ) Group 2.

Figure 1. Schematic Diagram showing layout of the study conducted with assortment of total number of patients (n = 1681) into 2 groups. Group 1: Standard Colonoscopy (n = 765) and Group 2: Observer Augmented Colonoscopy (n = 916) and subsequent analysis.

There was no significant difference in the baseline characteristics between the two groups. 42 percent were male and 58 percent were female.

A significant difference was found in the ADR rates between the 2 groups, 41.8% in Group 2 vs 37.6% in Group 1, p = 0.008, (Table 1). Average number of polyp per patient detected by Observer Augmented Colonoscopy was 2.32/patient compared to 1.85/ patient in standard colonoscopy group (p = 0.001). Absolute Benefit Increase (ABI) was 4.2% and Relative Benefit Increase (RBI) was 11.2% with Number Needed to Treat by OAC to find one additional patient with adenoma was 23.8. Polyps less than or equal to 5 mm were found to be 73.3% in group 1 (ST) and 78% in group 2 (OAC). Polyps sized 6–9mm and equal to or more than 10 mm were 9.8% and 16.9% in group 1 and 6.4% and 15.6% in group 2 respectively. Right sided and left sided polyps were 43.7% and 56.3% in group 1 versus 35.9% and64.1% in group 2. High grade dysplasia was evident in 2.4% polyps in group 1 versus 3.9% in group 2. Cancer was detected in 0.75 and 0.79% in group 1 and group 2 respectively.

Table 1. Detection Rates of colon polyps and mean number of polyps detected per subject with percentage of polyps according the size and location

|

Group 1(n = 765) |

Group 2 (n = 916) |

p value |

|

|

ADR Polyps/Pt Polyps/pt ABI RBI NNT TOTAL POLYPS Polyp size 1. ≤ 5mm 2. 6–9mm 3. ≥ 10mm Polyp location Right colon Left colon

High grade dysplasia polyps Cancer |

37.6% 1.85 533 391 polyps (73.3%) 52 polyps (9.8%) 90 polyps (16.9%) 233 (43.7%) 300 (56.3%)

13 (2.4%) 04 (0.75%) |

41.8% 2.32 889 693 polyps (78%) 57 polyps (6.4%) 139 polyps (15.6%) 319 polyps (35.9%) 570 polyps (64.1%)

35 (3.9%) 07 (0.79%) |

<0.001 4.2% 11.2% 23.8 |

Table illustrating detection rates of colon polyps and mean number of polyps detected per subject with percentage of polyps according to side and location. Polyp/patient was higher in Group 2 at 41.8% (Observer Augmented Colonoscopy) versus 37.6% in Group 1 (Standard Colonoscopy) . Absolute Benefit Increase (ABI) was 4.2% and Relative Benefit Increase (RBI) was 11.2% with Number Needed to Treat by OAC to find one additional patient with adenoma was 23.8. Right and left sided polyps in standard colonoscopy group were 43.7% and 56.3% respectively versus 35.9% and 64.1% in augmented colonoscopy group.

Discussion

Higher ADR decreases the risk of development of colorectal cancer by finding and removing precursor lesions [5]. The recommended minimum goal of ADR is >20% in women and >30% in men [21] This may vary depending on patient population, risk factors including patient age and family history. ADR’s also are dependent on screening versus surveillance colonoscopy. As in previous studies our results show that OAC resulted in higher ADR compared to standard colonoscopy. Furthermore data showed that the average number of polyps per patient in OAC was also higher compared to standard colonoscopy and the results were statistically significant. Two previous retrospective studies have evaluated the impact of a fellow involvement during colonoscopy [16, 22].A retrospective study by Rogart et al. reported 14% improvement in the ADR by including fellows as second observers. Our results demonstrated that 82% of the augmented polyps removed were flat and 5 mm or less. In a study by Rogart et al. the adenomas detected when fellows participated were also smaller (4.4mm vs 5.8 mm, p = 0.05) from these findings it is suggested that visual scanning might be efficient when two sets of eyes are involved. In this regard our study demonstrates that trained endoscopy technician participation increases ADR significantly. Our study showed that 58% of the polyps were found in the sigmoid colon. A multicenter study [18] showed no significant difference in the anatomical location or shape of polyps.

There can be several reasons that can lead to a polyp being missed. Failure to bring the polyp into view can result in missed lesions [17]. Several potential reasons for missing adenomas during a colonoscopy include the following [23]: (a) The polyp was not detected. (b) The polyp may not be visible in field of endoscopic view due to the anatomical location. (c) The polyp was in the field of view but not recognizable. (d) The endoscopist may have been distracted. (e) The polyp was recognizable but not detected. The latter indicates that some polyps are within the field of view. The current study suggests that better recognition may be achieved by adding a second observer to improve detection of recognizable, but missed polyps. The observer can be a technician rather than a fellow or nurse. The level of fellowship training and experience also increases ADR [16]. Study by Almansa C et al. shows a relationship between visual gaze patterns (VGP) and ADR and endoscopist with higher ADR spend more time concentrating on the center of the screen [17]. By having a second set of eyes focusing on the screen it can help improve ADR by addressing potential polyp detection limitations c-e above. This essentially has the same effect as decreasing withdrawal time, more area scanned in less time. Phenomenon’s like “change blindness” when changes are missed during eye movements and interruptions in visual scanning and “inattentional blindness” when we fail to visualize something when our attention is focused elsewhere [24, 25] can be a reason for endoscopist not perceiving the presence of adenomas. In OAC some of these deficiencies can be attenuated. It is evident from our prospective study in which the ADR is 41.8% in observer augmented colonoscopy vs 37.6% in standard colonoscopy, p<0.001

Experienced endoscopy staff usually focus on performing their responsibilities, such as administering sedation under physician supervision, patient monitoring, polypectomy assistance, and other technical aspects of the procedure. All aspects of the endoscopic procedure may be facilitated by an experienced nurse and or technician. A previous retrospective study showed that an experienced nurse increased the PDR versus an inexperienced nurse [26]. In a single-center retrospective study conducted by the same investigators endoscopy nurse inexperience was associated with increased odds for immediate complications, decreased cecal intubation rates and prolonged procedure times [27]. The endoscopy nurse/technician can help improve the quality of screening colonoscopy as an additional observer. We also believe that methods for maximizing polyp detection should be a part of endoscopy nurse and technician training programs. Endoscopy technicians in our study were educated to detect polyps in the observer augmented group which they performed along with their routine responsibilities during colonoscopy. Furthermore they had a minimum of 3 years’ experience in assisting with colonoscopy and polypectomy.

Colonoscopy rarely misses polyps that are equal to or greater than 10 mm, but the miss rate increases significantly in smaller sized polyps [28, 29]. Nonpolypoid depressed adenomas are more difficult to identify during a screening colonoscopy, but they carry a greater risk for developing into high-grade dysplasia or sub mucosal invasive cancer [30, 31]. Our results showed that most of the polyps identified in dual observation group were flat and 5mm or less and more than half of them were found in the sigmoid colon. There is no record whether the endoscopy technician or the endoscopist found the polyps. Our study mirrors the study by Lee et al. [18] who reported that only 7 (7/408, 1.7%) nonpolypoid depressed adenomas were found in the dual-observation group, but they did not record whether the nurse or endoscopist found the lesions. Increasing the detection of sessile polyps has been recognized as an important factor in improving the efficacy of colonoscopy particularly in the prevention of right-sided colon cancers [32]. A study by Sawhney MS et al [33] stated that adenomas with high grade dysplasia are more likely to be flat and in the proximal colon. Total colonic dye-spray enhances the detection of small adenomas in the proximal colon and patients with multiple adenomas [34]. A randomized controlled trial also concluded that chromoendoscopy improves the total number of adenomas detected and enhances the detection of diminutive and flat lesions [35].These technologies are time-consuming and not standard of care.

Our technicians were educated to inspect the mucosa for polyps during insertion and withdrawal phases. Studies by Aslanian [19], Lee [18] and Kim [36] inspected the colonic mucosa during withdrawal phase but did not report the phase in which the inspection occurred.

Recent randomized trials with High Defination (HD) colonoscopy have reported a high ADR, ranging from 48.4% to 57% in patients with indication screening [37, 38]. High-definition chromo colonoscopy marginally increased overall adenoma detection, and yielded a modest increase in flat adenoma and small adenoma detection, compared with high-definition white light colonoscopy [38]. The high adenoma detection rates observed in this study may be due to the high-definition technology used in both groups and the fact that these were colonoscopy surveillance patients. Further prospective investigations need to be performed in this regard.

Our study had certain limitations. It was not randomized but rather a consecutive enrollment of patients, first with standard colonoscopy and subsequently with augmented colonoscopy a better study would have been randomized study using a computer to alternate colonoscopy methods. Furthermore the study was not blinded, the endoscopist knew the procedure was augmented or not and could have added bias to the results. Nonetheless our study confirms that of others that visual augmentation can uncover previously overlooked polyps. It also shows that technicians can perform as well as endoscopy nurses and or GI fellows based on previous study results.

Nurses and or technicians appear to be ideal second observers given their experience and integral involvement in procedures. The implementation of routine observation by endoscopy staff should not require a significant increase in resource utilization. Therefore we recommend that both nurses and technicians be vigilant observers during colonoscopy while refraining from other responsibilities particularly during the withdrawal phase of the colonoscopy.

References

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, et al. (2008) Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin 58: 71–96. [crossref]

- Lieberman DA, Weiss DG, Bond JH, Ahnen DJ, Garewal H, et al. Use of colonoscopy to screen asymptomatic adults for colorectal cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 343: 162–168.

- Zauber A G, Winawer SJ, O’Brien MJ (2012) “Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths,” The New England Journal of Medicine 366: 687–696.

- Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, O’Brien MJ, Gottlieb LS, et al. (1993) Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med 329: 1977–1981. [crossref]

- Kaminski MF, Regula J, Kraszewska E et al. (2010) “Quality indicators for colonoscopy and the risk of interval cancer,” The New England Journal of Medicine 362: 1795–1803.

- Davila RE, Rajan E, Baron TH (2006) ASGE guideline: colorectal cancer screening and surveillance. Gastrointest Endosc 63: 546–557.

- Heresbach D, Barrioz T, Lapalus MG (2008) Miss rate for colorectal neoplastic polyps: a prospective multicenter study of back-to-back video colonoscopies. Endoscopy 40: 284–290.

- Atkin WS, Morson BC, Cuzick J (1992) Long-term risk of colorectal cancer after excision of rectosigmoid adenomas. New England Journal of Medicine 326: 658–662.

- Williams JE, Holub JL, Faigel DO (2012) Polypectomy rate is a valid quality measure for colonoscopy: results from a national endoscopy database. Gastrointestinal endoscopy 75: 576–582.

- Leufkens AM, DeMarco DC, Rastogi A (2011) “Effect of a retrograde-viewing device on adenoma detection rate during colonoscopy: the TERRACE study,” Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 73: 480–489.

- S. C. Ng, K. K. F. Tsoi, H. W. Hirai (2012) “The efficacy of cap-assisted colonoscopy in polyp detection and cecal intubation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials,” The American Journal of Gastroenterology 107: 1165–1173.

- Anderson JC, Shaw RD (2014) “Update on colon cancer screening: recent advances and observations in colorectal cancer screening,” Current Gastroenterology Reports 16: 403.

- Overholt BF, Brooks-Belli L, Grace M, Rankin K, Harrell R, et al (2010) Withdrawal times and associated factors in colonoscopy: a quality assurance multicenter assessment. Journal of clinical gastroenterology 44: 80–86.

- Rex DK (2006) Maximizing detection of adenomas and cancers during colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 101: 2866–2877. [crossref]

- Xu L, Zhang Y, Song H, Wang W, Zhang S, et al. (2016) Nurse Participation in Colonoscopy Observation versus the Colonoscopist Alone for Polyp and Adenoma Detection: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized, Controlled Trials. Gastroenterology Research and Practice 2016: 1–7.

- Peters SL, Hasan AG, Jacobson NB, Austin GL (2010) “Level of fellowship training increases adenoma detection rates,” Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 8: 439–442.

- Almansa C, Shahid MW, Heckman MG, Preissler S, Wallace MB (2011) Association between visual gaze patterns and adenoma detection rate during colonoscopy: a preliminary investigation. The American journal of gastroenterology 106: 1070.

- Lee CK, Park DI, Lee SH, Hwangbo Y, Eun CS, et al (2011) Participation by experienced endoscopy nurses increases the detection rate of colon polyps during a screening colonoscopy: a multicenter, prospective, randomized study. Gastrointestinal endoscopy 74: 1094–1102.

- Aslanian HR, Shieh FK, Chan FW, Ciarleglio MM, Deng Y, et al. (2013) Nurse observation during colonoscopy increases polyp detection: a randomized prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol 108: 166–172.

- Oh YS, Collins CL, Virani S, Kim MS, Slicker JA, et al. (2013) “Lack of impact on polyp detection by fellow involvement during colonoscopy: a meta-analysis,” Digestive Diseases and Sciences 58: 3413–3421.

- Rex DK, Schoenfeld PS, Cohen J, Pike IM, Adler DG, et al. (2015) Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointestinal endoscopy 81: 31–53

- Rogart JN, Siddiqui UD, Jamidar PA, Aslanian HR (2008) Fellow involvement may increase adenoma detection rates during colonoscopy. The American journal of gastroenterology 103: 2841.

- Wallace MB (2007) Improving colorectal adenoma detection: technology or technique?. Gastroenterology 132: 1221–1223.

- Wolfe JM, Reinecke A, Brawn P (2006) Why don’t we see changes? The role of attentional bottlenecks and limited visual memory. Visual Cognition 14: 749–780.

- Simons DJ, Chabris CF (1999) Gorillas in our midst: Sustained inattentional blindness for dynamic events. Perception. 28: 1059–1074.

- Dellon ES, Lippmann QK, Sandler RS, Shaheen NJ (2008) Gastrointestinal endoscopy nurse experience and polyp detection during screening colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 6: 1342–1347.

- Dellon ES, Lippmann QK, Galanko JA, Sandler RS, Shaheen NJ (2009) Effect of GI endoscopy nurse experience on screening colonoscopy outcomes. Gastrointestinal endoscopy 70: 331–343.

- van Rijn JC, Reitsma JB, Stoker J, Bossuyt PM, van Deventer SJ, et al. (2006) Polyp miss rate determined by tandem colonoscopy: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 101: 343–350. [crossref]

- Ahn SB, Han DS, Bae JH, Byun TJ, Kim JP, et al. (2012) The Miss Rate for Colorectal Adenoma Determined by Quality-Adjusted, Back-to-Back Colonoscopies. Gut Liver 6: 64–70. [crossref]

- Kudo SE, Lambert R, Allen JI (2008) “Nonpolypoid neoplastic lesions of the colorectal mucosa,” Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 68: 3–47.

- Matsuda T, Saito Y, Hotta K, Sano Y, Fujii T (2010) “Prevalence and clinicopathological features of nonpolypoid colorectal neoplasms: should we pay more attention to identifying flat and depressed lesions?” Digestive Endoscopy 22: 57–62.

- Hewett DG, Rex DK (2011) Miss rate of right-sided colon examination during colonoscopy defined by retroflexion: an observational study. Gastrointest Endosc74: 246–252.

- Sawhney MS, Dickstein J, LeClair J, Lembo C, Yee E (2015) Adenomas with high-grade dysplasia and early adenocarcinoma are more likely to be sessile in the proximal colon. Colorectal Dis 17: 682–688. [crossref]

- Brooker JC, Saunders BP, Shah SG, Thapar CJ, Thomas HJ, et al (2002) Total colonic dye-spray increases the detection of diminutive adenomas during routine colonoscopy: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointestinal endoscopy 56: 333–338.

- Hurlstone DP, Cross SS, Slater R, Sanders DS, Brown S. Detecting diminutive colorectal lesions at colonoscopy: a randomised controlled trial of pan-colonic versus targeted chromoscopy. Gut. 53: 376–380.

- Kim TS, Park DI, Lee DY (2012) “Endoscopy nurse participation may increase the polyp detection rate by second-year fellows during screening colonoscopies,” Gut and Liver 6: 344–348.

- Rex DK, Helbig CC (2007) High yields of small and flat adenomas with high-definition colonoscopes using either white light or narrow band imaging. Gastroenterology 133: 42–47.

- Kahi CJ, Anderson JC, Waxman I, Kessler WR, Imperiale TF, et al (2010) High-definition chromocolonoscopy vs. high-definition white light colonoscopy for average-risk colorectal cancer screening. The American journal of gastroenterology 105: 1301.