Abstract

Background: Postgastrectomy vitamin B12 deficiency is common metabolic sequel and worsens the quality of life of gastric cancer survivors. We usually selected intramuscular injection of vitamin B12 for vitamin B12 deficiency after gastrectomy. Recently, oral vitamin B12 replacement is reported. Therefore, we investigated retrospectively the efficacy of oral vitamin B12 replacement for gastric cancer patients with vitamin B12 deficiencyafter total gastrectomy.

Methods: We reviewed 73 patients with gastric cancer who underwent total gastrectomy and were treated vitamin B12 replacement. Patients were consisted of 56 males and 17 females and median age was 70 y/o. We investigated time to vitamin B12 deficiency after total gastrectomy, initial treatment of vitamin B12 replacement, and improvement of vitamin B12 deficiency.

Results: The median time to vitamin B12 deficiency was about 9 months. Initial treatment of vitamin B12 replacements were intramuscular injection for 42 patients, per oral replacement for 28 patients and intravenous injection for 3 patients. Finally, all patients were treated with per oral replacement and the serum vitamin B12 levels became within normal range. Final vitamin B12 doses of replacement therapy were 500 µg of 20 out of 73 pts, respectively.

Conclusions: After total gastrectomy, vitamin B12 deficiency is occurred in 100% patients and within 1 year after TG frequently. Vitamin B12 replacement therapy should be necessary and continued. According to our results, one vitamin B12 tablet a day is enough. The vitamin B12 deficiency symptoms could be prevented. 500 micrograms vitamin B12 replacement orally is maybe effective and necessary.

Keywords

vitamin B12, replacement therapy, total gastrectomy, gastric cancer, oral vitamin B12 replacement

Background

A variety of factors affects some patients after gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Some nutrition deficiencies result from disturbance of the normal anatomic and physiologic mechanism that control gastric function. Gastrectomised patients commonly lose weight. The degree of weight loss tends to parallel the magnitude of the operation. The cause of weight loss after gastric surgery generally are altered dietary intake or malabsorption. Vitamin B12 deficiency as malnutrition after gastrectomy is common complication [1, 2].

Normally, there is a vast excess of intrinsic factor. But after gastrectomy, there is little intrinsic factor. Especially, after total gastrectomy (TG), there is no intrinsic factor. Because of this, vitamin B12 deficiency is an inevitable complication after TG. Cumulative vitamin B12 deficiency rates were 100% for TG and 15.7% for distal gastrectomy (DG) 4 years after surgery. The median time to vitamin B12 deficiency was 15 months after TG, whereas the median time was not reached after DG [3].

In spite of vitamin B12 administration orally is not a reliable route after TG, Kim et al previously reported that serum vitamin B12 increased after oral and intramuscular administration of vitamin B12 in TG patients. In this report, for the oral vitamin B12 replacement, mecobalamin was administrated. The dosage comprised three 500 µg tablets of mecobalamin for a total of 1500 µg daily. For the intramuscular vitamin B12 replacement, cyanocobalamin was administered. The dosage was 1000 µg weekly for 5 weeks and monthly thereafter [4].

Even if an oral vitamin B12 replacement is effective, a question whether is necessary for three tablets a day, 1500 µg daily, or not is left. Are one or two tablets, 500 or 1000 µg daily, not an effective dose? Thus, we evaluated retrospectively the efficacy and safety of oral vitamin B12 replacement for vitamin B12 deficiency after TG in gastric cancer patients.

Materials and Methods

The study was a single-center retrospective assessment and was conducted at Yokohama City University Hospital, Department of Surgery, Yokohama, Japan.

Patients

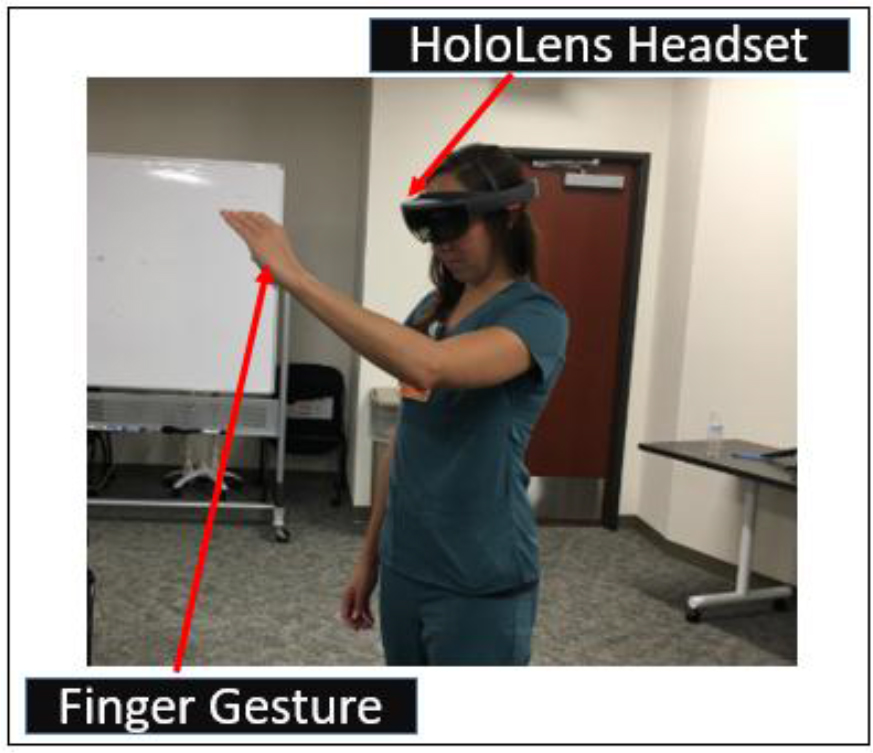

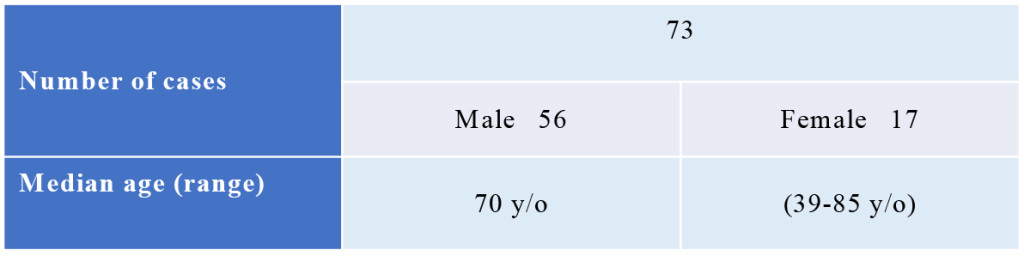

Serum vitamin B12 was measured after the surgery that is total gastrectomy for gastric cancer. All the patients whose serum vitamin B12 levels were below 180 pg/ml were treated with the intramuscular or intravenous or oral vitamin B12 replacement. Inclusion criteria were a history of TG for gastric cancer irrespective of receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy or postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy and level of vitamin B12 below 180 pg/ml regardless of vitamin B12 deficiency related symptoms. The exclusion criteria were as a history of receiving any vitamin B12 supplementation such as multivitamins or nutritive supplement food. We reviewed 73 patients (pts) who underwent TG for gastric cancer between July 2004 and April 2016. These pts were diagnosed vitamin B12 deficiency and treated vitamin B12 replacement. Pts were consisted of 56 males and 17 females and median age was 70 y/o (range: 39–85) (Fig. 1). We investigated time to vitamin B12 deficiency after TG, initial treatment of vitamin B12 replacement, and improvement of vitamin B12 deficiency.

Figure 1. Patients

Pts were consisted of 56 males and 17 females and median age was 70 y/o (range: 39–85).

pts; patients

Replacement therapy

For the intra-muscular vitamin B12 replacement (IM), cyanocobalamin was administered. The dosage was 500 µg every 1–3 month.

For the oral vitamin B12 replacement (PO), mecobalamin was administrated. The dosage comprised 500 µg tablet of mecobalamin for a total of 500–1500 µg daily.

For the intra-venous vitamin B12 replacement (IV), cyanocobalamin was administered. The dosage was 500 µg every 1–3 month.

Measurement of Vitamin B12

Before the start of treatment and every 1 to 6 months after vitamin B12 replacement, serum specimens were obtained. Serum vitamin B12 were measured with the chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay in a UniCel DxH 800 analyzer (Beckman Coulter, USA).

Results

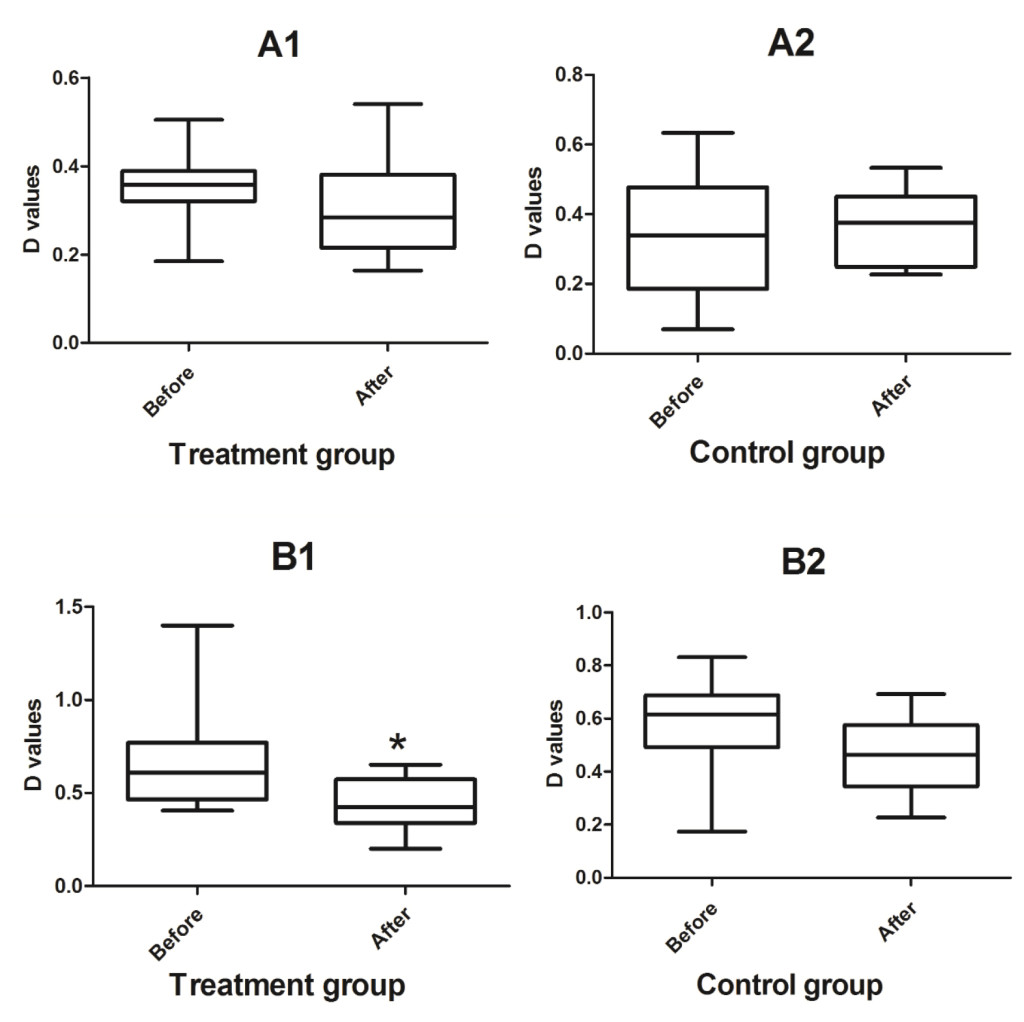

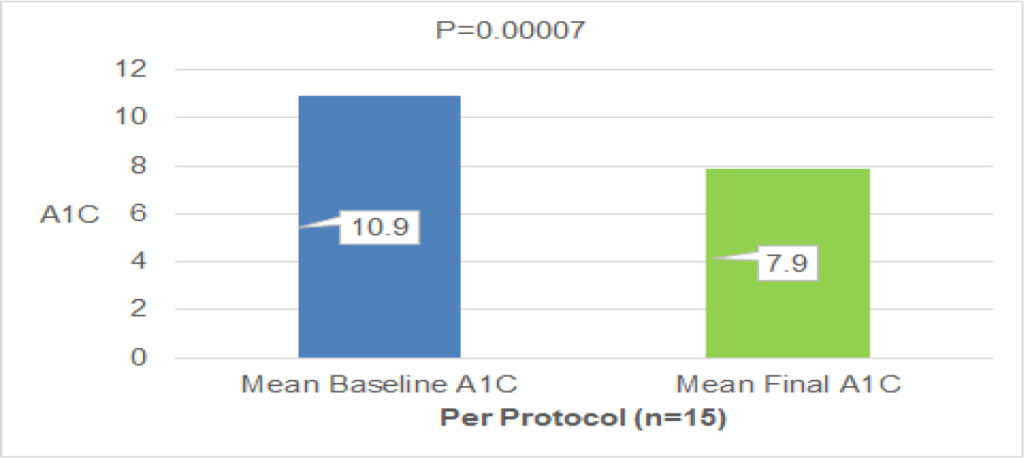

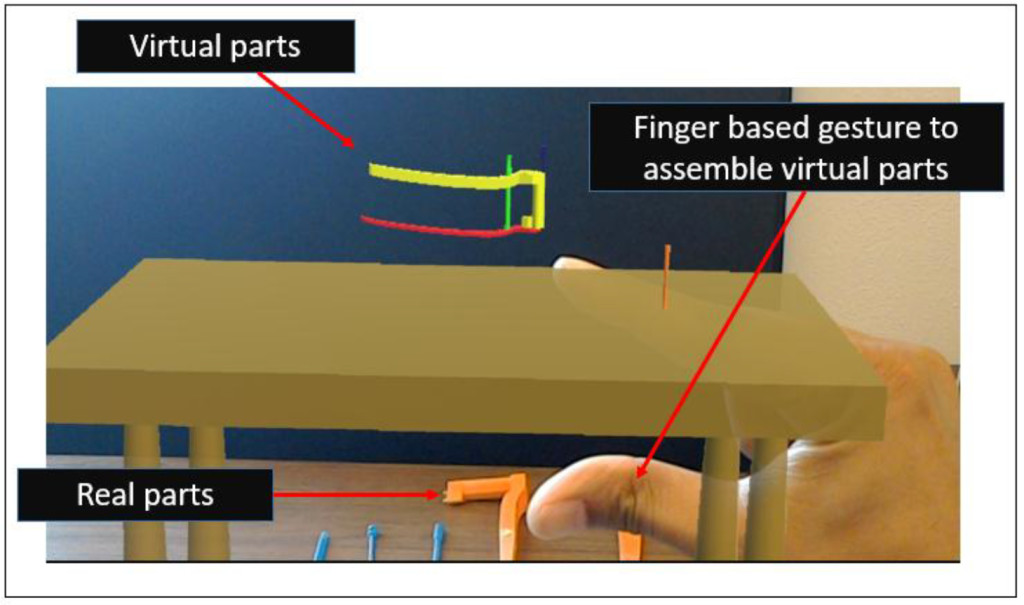

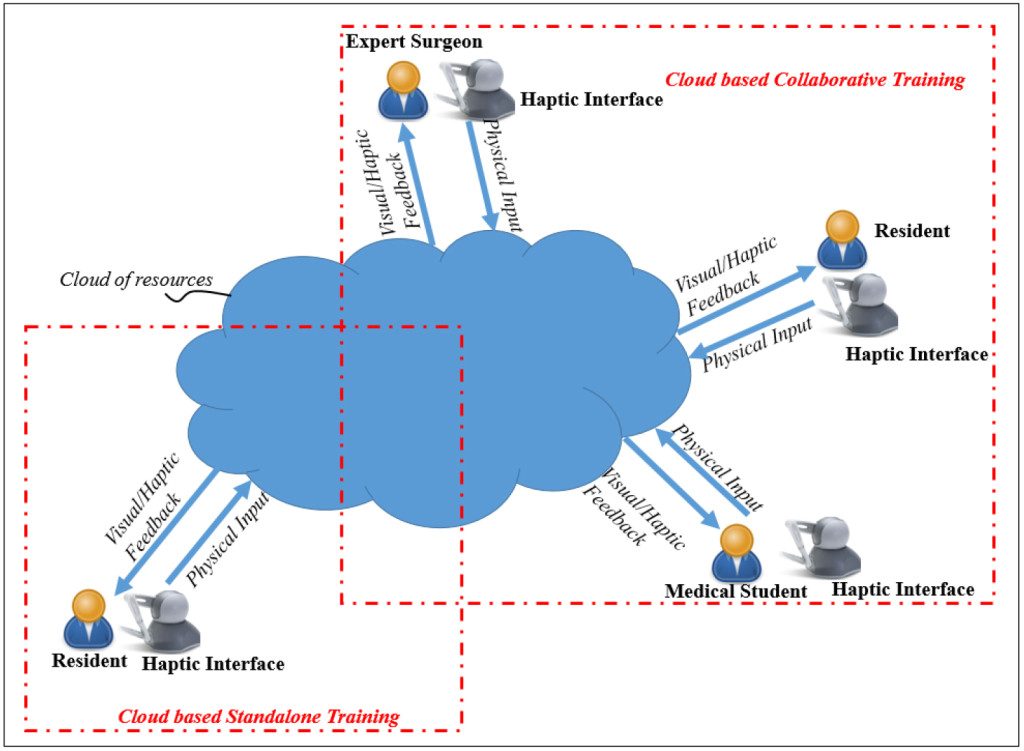

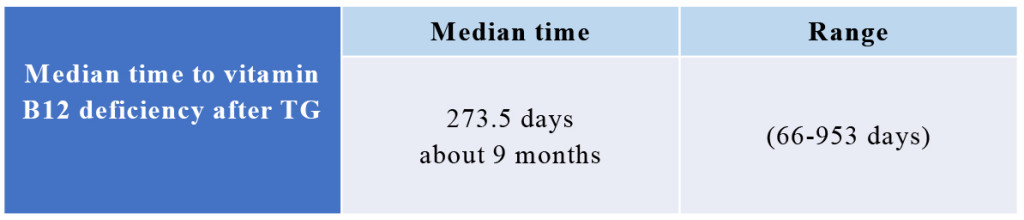

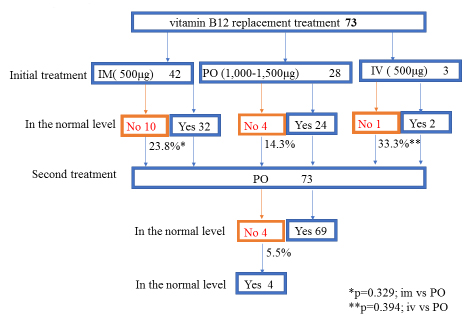

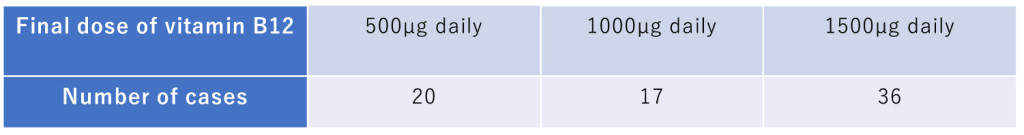

The median time to vitamin B12 deficiency was 273.5 days (about 9 months, range: 66–953 days) after TG (Fig. 2). Initial treatment of vitamin B12 replacements were IM (dosage: 500 µg cyanocobalamin) for 42 pts, PO (dosage: 1,000–1,500 µg mecobalamin a day) for 28 pts and IV (dosage: 500 µg cyanocobalamin) for 3 pts. Serum vitamin B12 levels were not normalized in 10 (23.8%) out of 42 pts of IM, 4 (14.3%) out of 28 pts of PO, 1 (33.3%) out of 3 pts of IV, respectively. There is no significant difference between IM, IV and PO. Finally, all pts were treated with PO. But serum vitamin B12 levels decreased in 4 (5.5%) out of 73 pts of PO. These 4 pts were not continuously administered vitamin B12. After explaining it not to discontinue vitamin B12 replacement therapy to these 4 pts, the serum vitamin B12 levels became within normal range (Fig. 3). Final vitamin B12 doses of replacement therapy were 500 µg of 20, 1,000 µg of 17, and 1,500 µg of 36 out of 73 pts, respectively (Fig. 4).

Figure 2. Median time of vitamin B12 deficiency

The median time to vitamin B12 deficiency was 273.5 days (about 9 months, range: 66–953 days) after TG.

TG; total gastrectomy

Figure 3. Vitamin B12 replacement therapy

Initial treatment of vitamin B12 replacements were IM (dosage: 500 µg cyanocobalamin) for 42 pts, PO (dosage: 1,000–1,500 µg mecobalamin a day) for 28 pts and IV (dosage: 500 µg cyanocobalamin) for 3 pts. “No” means that serum vitamin B12 levels were not normalized. “Yes” means that serum vitamin B12 levels were normalized. “No” was 10 (23.8%) out of 42 pts of IM, 4 (14.3%) out of 28 pts of PO, 1 (33.3%) out of 3 pts of IV, respectively. There is no significant difference between IM, IV and PO. Finally, all pts were treated with PO. But serum vitamin B12 levels decreased in 4 (5.5%) out of 73 pts of PO. These 4 pts were not continuously administered vitamin B12. After explaining it not to discontinue vitamin B12 replacement therapy to these 4 pts, the serum vitamin B12 levels became within normal range.

IM; intra-muscular vitamin B12 replacement, PO; oral vitamin B12 replacement, IV; intra-venous vitamin B12 replacement, pts; patients

Figure 4. Final dose of vitamin B12 PO

Final vitamin B12 doses of replacement therapy were 500 µg of 20, 1,000 µg of 17, and 1,500 µg of 36 out of 73 pts, respectively.

Discussion

Normally, there is a vast excess of intrinsic factor. But after gastrectomy, there is little intrinsic factor. Especially, after TG, there is no intrinsic factor. Because of this, vitamin B12 deficiency is an inevitable complication after TG. Cumulative vitamin B12 deficiency rates were 100% for TG and 15.7% for DG 4 years after surgery. The median time to vitamin B12 deficiency was 15 months after TG, whereas the median time was not reached after DG [3]. In this report, the median time to vitamin B12 deficiency was about 9 months after TG. Our result was shorter than previous report from Korea [3]. The difference between Japan and Korean dietary habits may be the cause of this result. It is described in the textbook as follows [5], body stores are of the order of 2–3mg, sufficient for 3–4 years if supplies are completely cut off. May TG progress a daily choler excretion or a consumption of the vitamin B12? Gastric atrophy is background of gastric cancer. Most gastric cancer patients are complicated with atrophic gastritis. A severe lack of intrinsic factor due to gastric atrophy [5]. Vitamin B12 storage before TG would be decreased in gastric cancer patients with gastric atrophy. This small storage of vitamin B12 may be the cause of the shorter median time to vitamin B12 deficiency after TG.

Vitamin B12 absorption has two mechanisms. One is passive, occurring equally through buccal, duodenal, and ileal mucosa; it is rapid but extremely inefficient, with < 1% of an oral dose being absorbed by this process. The normal physiologic mechanism is active; it occurs through the ileum and is efficient for small oral dose of vitamin B12, and it is mediated be gastric intrinsic factor. Dietary vitamin B12 is released from protein complex by enzymes in the stomach, duodenum, and jejunum; it combines rapidly with a salivary glycoprotein that belongs to the family of cobalamin-binding proteins known as haptocorrins. In the intestine, the haptocorrin is digested by pancreatic tripsin and the cobalamin is transferred to intrinsic factor. Intrinsic factor is produced in the gastric parietal cells of the fundus and body of the stomach. The intrinsic factor-cobalamin complex passed to the ileum, where intrinsic factor attaches to specific receptor (cubilin) on the microvillus membrane of the enterocytes. The intrinsic factor-cobalamin complex enters the ileal cells, where intrinsic factor is destroyed. After a delay of about 6 hours, the cobalamin appears in portal blood attached to transcobalamin II. Between 0.5–5 µg of cobalamin enter the bile each day. This binds to intrinsic factor, and a major portion of biliary cobalamin normally is reabsorbed together with cobalamin derived from sloughed intestinal cells. Because of the appreciable amount of cobalamin undergoing enterohaptic circulation, cobalamin deficiency develops more rapidly in individuals who malabsorb cobalamin that it does in vegans, in whom reabsorption of biliary cobalamin is intact [5, 6].

There is an absorption disorder by lack of intrinsic factor and daily choler excretion of vitamin B12. And altered dietary intake and malabsorption caused body weight loss. Because of these variety of factors after TG, vitamin B12 deficiency would be occurred within one year after total gastrectomy, frequently.

Recently, body weight loss after gastrectomy was independent risk factor for continuation of adjuvant chemotherapy and survival [7, 8].

Pts who was undergone TG have only passive absorption of vitamin B12. In this reason, intramuscular injection of vitamin B12 is recommended as a parenteral chronic treatment for pts with vitamin B12 deficiency after TG [1, 2]. Previous reports indicated that oral vitamin B12 successfully treats patients with pernicious anemia who have defects in the main vitamin B12 absorption mechanisms as a result of the presence of autoantibodies specific for intrinsic factor or a history of surgical resection of the ileum [9–11].

In spite of vitamin B12 administration orally is not a reliable route after TG, Kim et al previously reported that serum vitamin B12 increased after oral and intramuscular administration of vitamin B12 in TG patients. In this report, for the oral vitamin B12 replacement, mecobalamin was administrated. The dosage comprised three 500 µg tablets of mecobalamin for a total of 1500 µg daily. For the intramuscular vitamin B12 replacement, cyanocobalamin was administered. The dosage was 1000 µg weekly for 5 weeks and monthly thereafter [4]. After TG, vitamin B12 absorption has only one mechanism that is passive absorption with <1 % of an oral dose being absorbed by this process. When three 500 µg tablets of mecobalamin for a total of 1500 µg daily are administered, total amount of vitamin B12 absorption is about <15µg. On the other hand, between 0.5–5 µg of cobalamin excreted choler each day [5, 6]. Because of passive absorption and choler excretion, three 500 µg tablets of mecobalamin administration is reasonable replacement therapy for vitamin B12 deficiency after TG. But mecobalamin tablet has high concentration of vitamin B12. We presume that passive absorption rate would be higher than 1% when mecobalamin tablet is administered orally. Because our results showed that 500 µg tablets of mecobalamin oral administration maintained normal serum vitamin B12 levels in 20 out of 73 pts. We guessed it in this way. When only 500 µg of mecobalamin were administered orally, total amount of vitamin B12 absorption should be over 5 µg. Otherwise there is more quantity of passive absorption than the quantity of choler excretion, and it is impossible that serum vitamin B12 maintains within normal levels.

Vitamin B12 deficiency worsen quality of life after TG. Because pernicious anemia, bilateral peripheral neuropathy or degeneration(demyelination) of the posterior and pyramidal tracts of the spinal cord, and optic atrophy, cerebral symptoms or dementia would be occurred [12,13]. Hwang et al. [14] reported a patient who developed ataxic gait 9 years after TG for gastric cancer. Spinal cord degeneration due to vitamin B12 deficiency should be suspected in patients with neurological disorders, including gait disturbance, after gastrectomy, even as a long-term complication. Like this case, vitamin V12 deficiency symptoms are long-term complications. Vitamin B12 replacement therapy should be necessary and continued.

In conclusion, after TG, vitamin B12 deficiency is occurred in 100% pts and within 1 year after TG frequently. Vitamin B12 replacement therapy should be necessary and continued routinely. IM is a reliable therapy. But IM needs to go to clinic a month and is painful. According to our results, one tablet PO a day is enough. The vitamin B12 deficiency symptoms could be prevented and number of the going to clinic on pts could be reduced using this replacement therapy.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest in association with the present study.

Acknowledgments: None

Abbreviations

TG: total gastrectomy

DG: distal gastrectomy

pts: patients

IM: intra-muscular vitamin B12 replacement

PO: oral vitamin B12 replacement

IV: intra-venous vitamin B12 replacement

References

- Brunicardi CF, Andersen DK, Billiar TR, Dunn DL, Hunter JG, Pollock RE. (2005) Schwartz’s Principles of Surgery, In: Dempsy DT, editor. Stomach. 8th ed. New York, McGraw-Hill: pp. 933–95.

- Townsent CM, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL. (2012) Sabiston Textbook of Surgery, In: Mahvi DM, Krantz SK, editor. Stomach. 19th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; pp.1182–1226.

- Hu Y, Kim HI, Hyung WJ, Song KJ, Lee JH, Kim YM, et al. (2013) Vitamin B(12) Deficiency after gastrectomy for gastric cancer: an analysis of clinical patterns and risk factors. Ann Surg. 258(6): 970–5. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000214. [Crossref]

- Kim HI, Hyung WJ, Song KJ, Choi SH, Kim CB, Noh SH. (2011) Oral vitamin B12 replacement: an effective treatment for vitamin B12 deficiency after total gastrectomy in gastric cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 18(13): 3711–7. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1764-6. [Crossref]

- Kasper DL, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J. (2015) Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine vol. 2, In: Hoffbrand AV, editor. Megaloblastic anemias. 19th ed. New York; McGraw-Hill; pp.640–9.

- Brunicardi CF, Andersen DK, Billiar TR, Dunn DL, Hunter JG, Pollock RE. (2005) Schwartz’s Principles of Surgery, In: Whang EE, Ashley SW, Zinner MJ, editor. Small intestine. 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; pp.1017–5.

- Aoyama T, Sato T, Maezawa Y, Kano K, Hayashi T, Yamada T, et al. (2017) Postoperative weight loss leads to poor survival through poor S-1 efficacy in patients with stage II/III gastric cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. Feb 7. doi: 10.1007/s10147-017-1089-y. [Crossref]

- Aoyama T, Yoshikawa T, Shirai J, Hayashi T, Yamada T, Tsuchida K, et al. (2013) Body weight loss after surgery is an independent risk factor for continuation of S-1 adjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 20(6): 2000–6. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2776-6. [Crossref]

- Berlin H, Berlin R, Brante G. (1968) Oral treatment of pernicious anemia with high doses of vitamin B12 without intrinsic factor. Acta Med cand. 184: 247–58 [Crossref]

- Kuzminski AM, Del Giacco EJ, Allen RH, Stabler SP, Lindenbaum J.(1998) Effective treatment of cobalamin deficiency with oral cobalamin. Blood. 92: 1191–8. [Crossref]

- Berlin R, Berlin H, Brante G, Pilbrant A. (1978) Vitamin B12 body stores during oral and parenteral treatment of pernicious anemia. Acta Med Scand. 204: 81–4. ) [Crossref]

- Kasper DL, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J. (2015) Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine vol. 2, In: Seeley WW,Miller BL, editor. Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. 19th ed. New York; McGraw-Hill; pp. 2598–608.

- Kasper DL, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J. (2015) Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine vol. 2, In: Amato AA, Barohn RJ, editor. Peripheral neuropathy. 19th ed. New York; McGraw-Hill; pp. 2674–94.

- Hwang CH, Park DJ, Kim GY. (2016) Ataxic gait following total gastrectomy for gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. Oct 7; 22(37): 8435–8438. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i37.8435. [Crossref]