Introduction

Pancreas transplantation was initially developed as a means to re-establish endogenous insulin secretion responsive to normal feedback controls and has evolved over time to a form of auto-regulating total pancreatic endocrine replacement therapy that can reliably achieve a durable euglycemic state without the need for either exogenous insulin therapy or close glucose monitoring. Pancreas transplantation is performed in patients who require administration of insulin because of type 1 or, less commonly, insulin-requiring type 2 diabetes, or following total pancreatectomy for benign disease [1]. Pancreas transplantation entails a major surgical procedure and the necessity for long-term immunosuppression so it is not offered universally to all patients with insulin-requiring diabetes but is usually directed to those that will already be committed to chronic immunosuppression [most commonly for kidney transplantation secondary to end stage diabetic nephropathy) [1]. In addition, candidates with potentially life-threatening metabolic complications from diabetes such as hypoglycemia unawareness or those who are failures of exogenous insulin therapy may benefit from pancreas transplantation in the absence of a kidney transplant [2]. A successful pancreas transplant is currently the only definitive long-term treatment that restores normal glucose homeostasis in patients with complicated diabetes without the risk of either severe hypo/hyperglycemia and may prevent, stabilize, or reverse progressive diabetic complications [1–3].

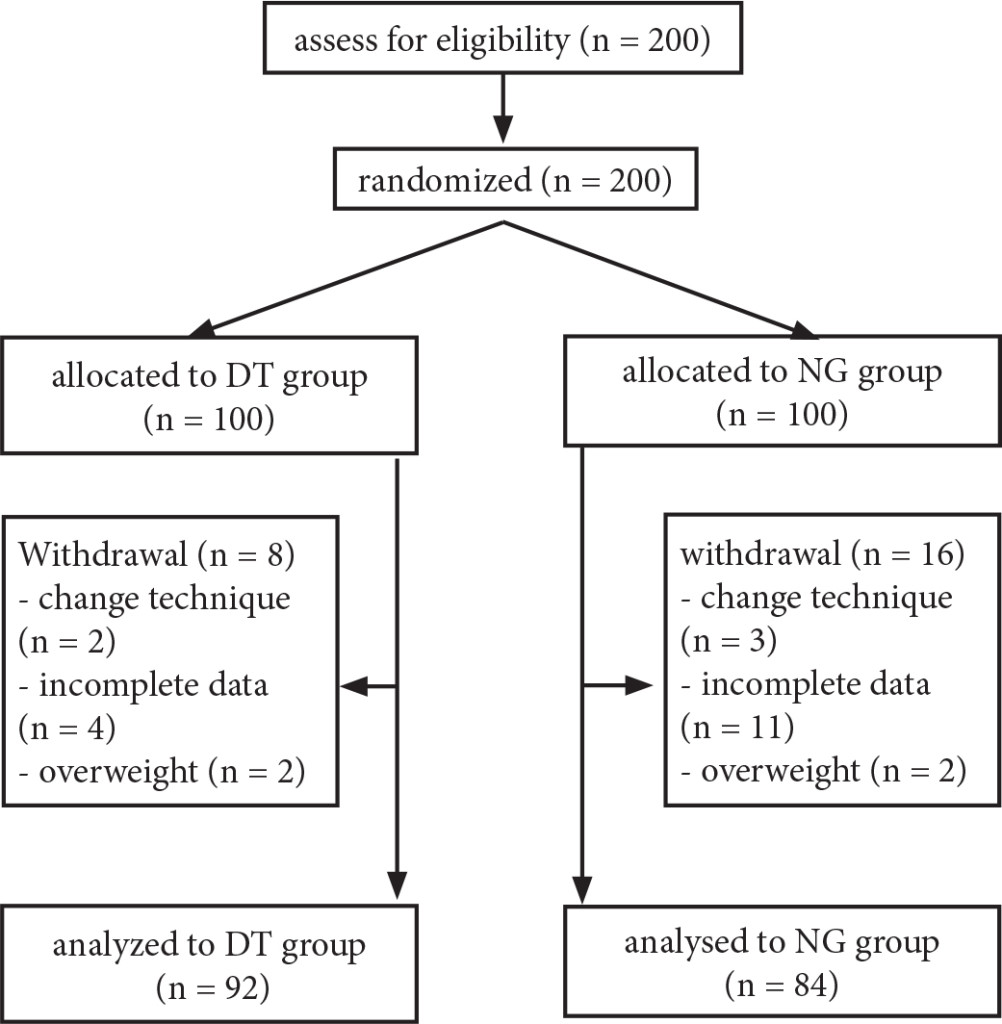

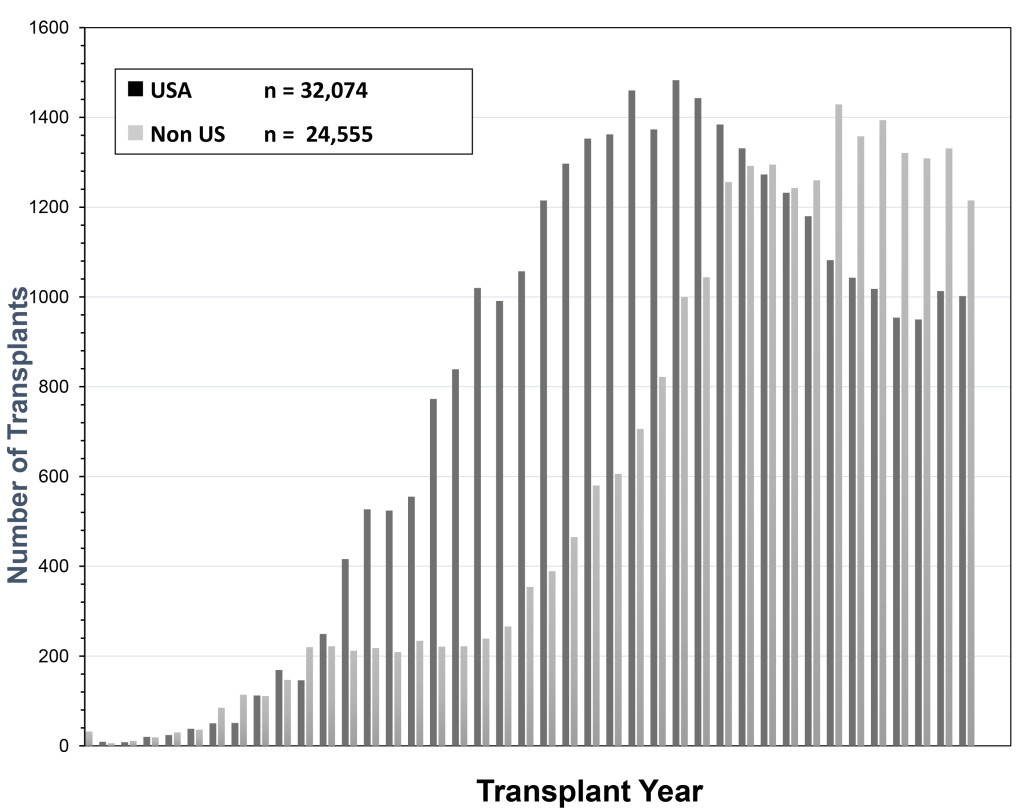

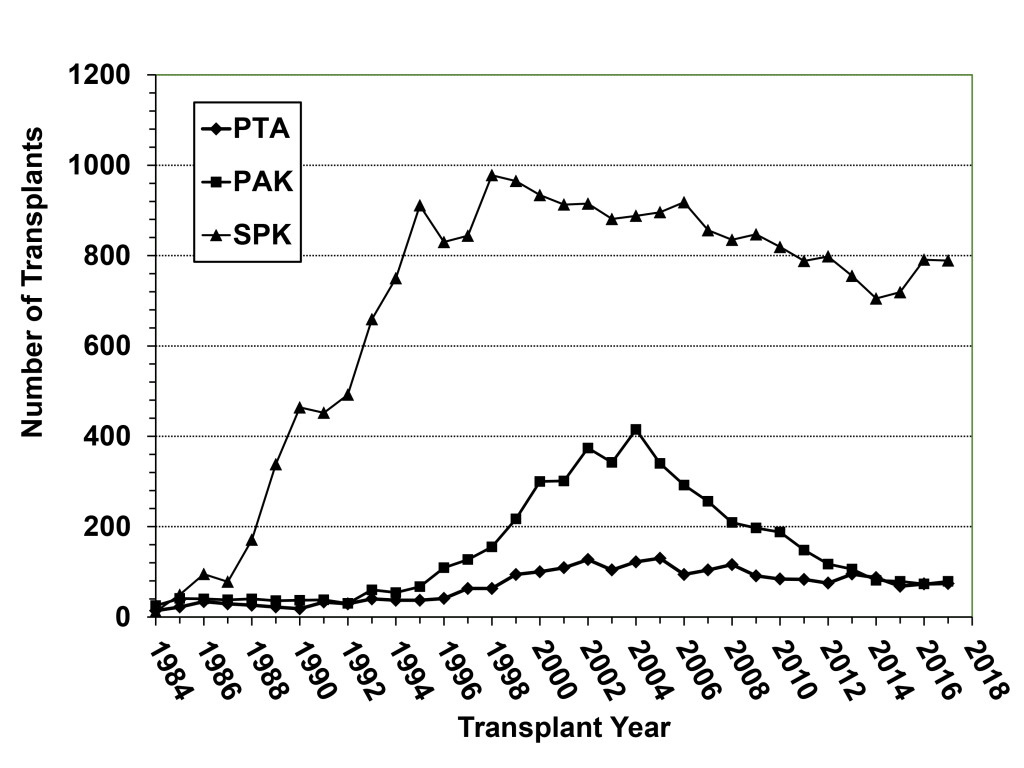

The history of pancreas transplantation largely parallels advances in clinical immunosuppression and surgical techniques. As of December 2017, more than 56,000 pancreas transplants were reported to the International Pancreas Transplant Registry [IPTR) including >32,000 from the United States [US) and >24,000 from outside of the US [FIGURE 1). [3–6) Pancreas transplantation in diabetic patients is divided into 3 major categories; those performed simultaneously with a kidney [SPK) transplant, usually from a deceased donor; those performed after a successful kidney [PAK) transplant in which the kidney transplant was performed from either a living [most commonly) or deceased donor; and pancreas transplantation alone [PTA) in the complete absence of the need for a kidney transplant. The latter two [PAK and PTA) categories are usually combined together as solitary pancreas transplants because the transplant is performed in the absence of uremia. Historically, solitary [PAK and PTA) transplants have had similar albeit inferior outcomes compared to SPK transplantation. In the US, the majority [84%) of pancreas transplants are currently performed as SPK transplants whereas approximately 16% are performed as either PAK or PTA cases [FIGURE 2) [3–6].

Figure 1. Total number of pancreas transplants performed in the US and outside of the US between 1966 and 2017 as reported by UNOS and the IPTR (at the time of analysis the reporting for non-US cases was not complete for the year 2017)

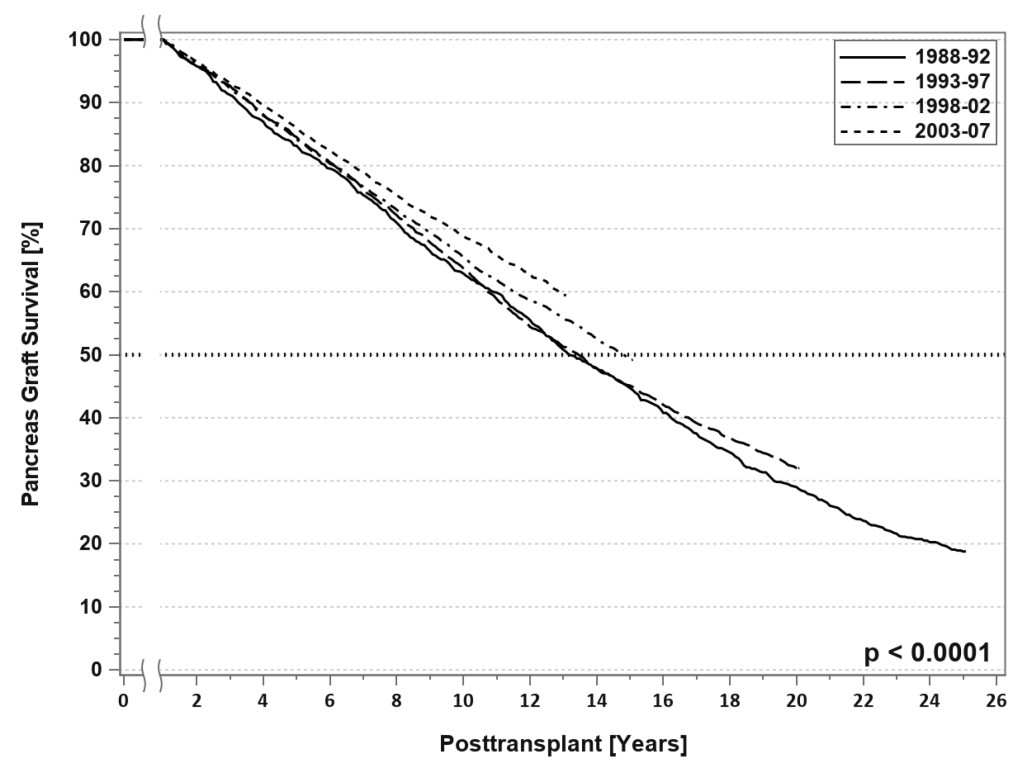

SPK transplantation has become a generally accepted treatment for uremic type 1 diabetes [1]. The evolution in surgical techniques, current patient management strategies, and advances in immunosuppression have resulted in excellent outcomes, even in populations previously considered high risk, such as patients older than 50 years, African-American recipients, patients with a “type 2 diabetes” phenotype, and solitary pancreas transplants recipients[1–11]. Insulin independence is sustained at 5 years in 77% of SPK and 60% of solitary pancreas transplant recipients [3–6]. For SPK transplant recipients with dual allograft function at one year, the conditional half-life of the pancreas graft currently averages 12–15 years, which is amongst the longest for extra-renal grafts

[FIGURE 3). [3–6, 12] Nearly all pancreas transplants are currently performed by one of three standardized techniques[1, 13–15]. Both technical and immunologic graft failure rates have decreased over time [3–6]. One of the most recent and exciting innovations in pancreas transplantation is the description of laparoscopic pancreas transplantation under robotic assistance [16, 17].

Figure 2. Annual number of pancreas transplant procedures in diabetic patients performed by transplant category in the US; the decline in SPK transplants began in 1999 whereas the number of solitary pancreas transplants (both PAK and PTA) started decreasing after 2004.

Figure 3. SPK conditional primary deceased donor pancreas graft survival for transplants performed between 1988 and 2007.

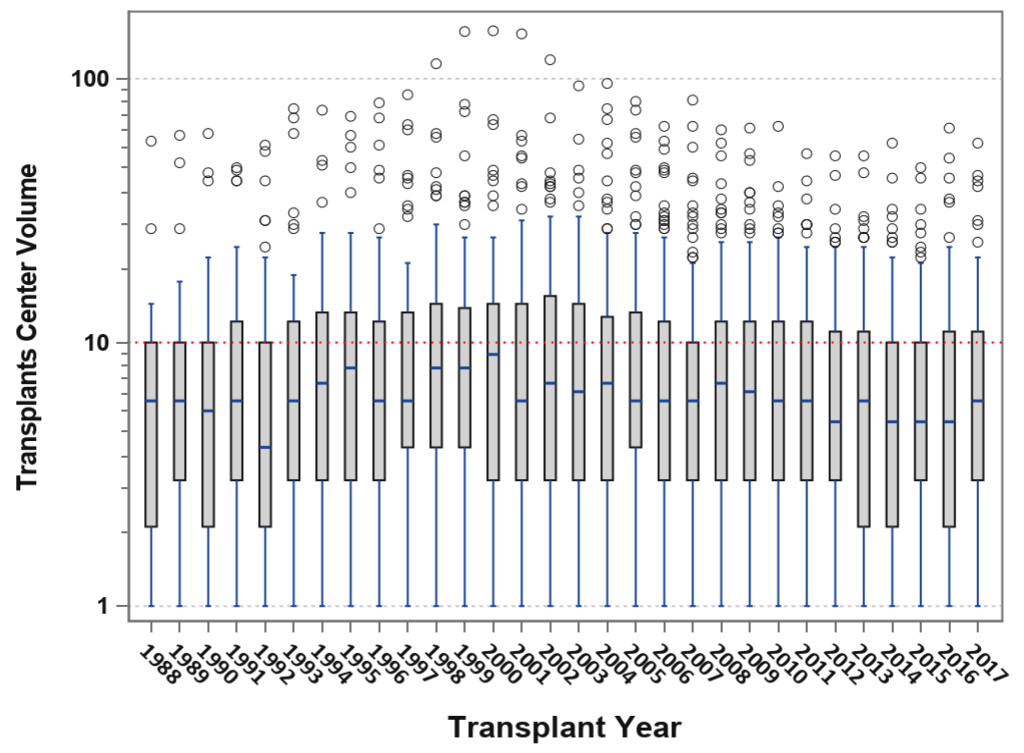

Pancreas transplantation in 2018 can be characterized by the “rule of 90s”; worldwide, 90% are SPK transplants, 90% are from conventional [young and low Body Mass Index [BMI] <30 kg/m2) donors, 90% are performed with enteric drainage, 90% have systemic venous drainage, 90% are managed with antibody induction, 90% receive initial tacrolimus or mycophenolate maintenance therapy, 90% of recipients are Caucasian, 90% have type 1 diabetes, 90% of recipients have a BMI <30 kg/m2, 90% have a panel reactive antibody level ≤20%, the 1-year graft survival rate for SPK transplants is 90%, and 5-year patient survival rates are 90% in all three recipient categories. [3–6] At the other end of the spectrum, there is the “rule of 30s”; 30% of patients are ≥ age 50 years , 30% undergo relaparotomy, 30% experience acute rejection, 30% of dual organ biopsies are discordant, 30% develop donor specific antibody, 30% remain steroid-free long-term, 30% of centers perform PTAs, 30% of centers performed more transplants in the most recent era [2010–2014) compared to the previous era [2005–2009), 30% of centers are very low volume centers [≤10 pancreas transplants in 5 years; Figure 4), 30% of SPK transplants in the US are performed by 12 large volume centers, and a 30% overall reduction in total pancreas transplants performed annually in the US occurred in the decade from 2005 to 2015 [Figure 1) [3–6].

Figure 4. Box-plot analysis showing transplant center volume over time; the median center volume has decreased from 9 to 6 pancreas transplants annually and the current lower and upper quartile values are 3–12 pancreas transplants per year.

Improving Outcomes in the Setting of Fewer Transplants Being Performed

According to data from the IPTR and the United Network for Organ Sharing [UNOS), the total annual number of pancreas transplants steadily increased in the US until 2004 [peaking at 1484) but then declined annually for the next 11 consecutive years [reaching a low of 943 in 2015, which was the lowest total since 1994). Fortunately, the number of pancreas transplants has rebounded to above 1000 per year in 2016 and 2017 [Figure 1) [3–6, 18]. This trend downward has been more dramatic for solitary pancreas transplants, particularly in the PAK category [415 performed in 2004, 79 performed in 2017, Figure 2). From 2004–2015, the annual number of SPK transplants in the US declined by 20% overall whereas the annual overall decreases in PAKs and PTAs were 81% and 42%, respectively [Figure 2) [3–6, 18]. In the last decade, era analyses of national data have demonstrated that deceased donor recovery rates and additions to the waiting list have decreased while donor organ discard rates and recipient waiting times have increased. At present, pancreas transplantation is one of the few solid organ transplants in the US that is experiencing an overall decline in activity [3–6, 18]. Unexpectedly, this has occurred in spite of significant improvements in graft and patient survival outcomes, even in higher risk patients, as shown below [Table 1) – an alarming trend because the history of solid organ transplantation has been characterized by an increase in volume mirroring improved results in most circumstances [18, 19].

Table 1. Recent outcomes of primary deceased donor pancreas and pancreas/kidney transplants performed between 1998 and 2017 with a potential follow-up time of at least 6 months.

|

1998–02 |

2003–07 |

2008–12 |

2013–17 |

P-value |

||||

|

Patient Survival |

SPK

|

1 Year |

94.7 |

95.4 |

96.9 |

97.4 |

<0.0001 |

|

|

3 Year |

90.1 |

91.5 |

94.0 |

95.1 |

||||

|

5 Year |

85.2 |

87.2 |

89.6 |

|||||

|

PAK

|

1 Year |

95.3 |

96.3 |

97.1 |

95.7 |

0.13 |

||

|

3 Year |

89.9 |

91.4 |

93.5 |

91.3 |

||||

|

5 Year |

82.1 |

85.1 |

88.8 |

– |

||||

|

PTA

|

1 Year |

98.2 |

96.3 |

96.6 |

98.4 |

0.36 |

||

|

3 Year |

93.1 |

91.6 |

93.6 |

94.9 |

||||

|

5 Year |

88.8 |

87.8 |

86.8 |

|||||

|

Graft |

SPK |

Pancreas |

1 Year |

83.4 |

85.0 |

88.8 |

90.3 |

<0.0001 |

|

3 Year |

76.6 |

78.8 |

82.9 |

84.7 |

||||

|

5 Year |

69.8 |

72.6 |

77.1 |

– |

||||

|

Kidney |

1 Year |

91.8 |

92.6 |

94.8 |

95.8 |

<0.0001 |

||

|

3 Year |

84.5 |

86.2 |

88.8 |

90.8 |

||||

|

5 Year |

77.0 |

79.7 |

82.2 |

– |

||||

|

PAK

|

1 Year |

78.3 |

78.9 |

84.7 |

85.1 |

<0.0001 |

||

|

3 Year |

66.6 |

65.5 |

73.7 |

75.3 |

||||

|

5 Year |

57.0 |

56.3 |

67.1 |

|||||

|

PTA

|

1 Year |

80.2 |

77.8 |

82.2 |

84.0 |

0.03 |

||

|

3 Year |

63.4 |

60.0 |

67.8 |

72.2 |

||||

|

5 Year |

55.2 |

53.0 |

58.2 |

– |

||||

Coincident with the decrease in pancreas transplant activity in the US, there has been a steady increase in the number of pancreas transplants performed outside of the US such that more annual pancreas transplants are now being performed outside of the US since 2008 [3–6]. In 2017, 1002 pancreas transplants were performed in the US [including multivisceral transplants) whereas nearly 1400 pancreas transplants were performed outside of the US and reported to the IPTR [Figure 1) [3–6]. Because reporting of pancreas transplants performed in the US is mandatory and reporting of non-US cases is voluntary, the actual number of pancreas transplants performed outside of the US may be even higher. However, recent data from the Eurotransplant [a collective of all transplant centers in eight European countries) and United Kingdom [UK) transplant registries suggest that a reduction in annual pancreas transplant activity has occurred in these regions as well [20]. Between 2004 and 2016, the average annual decline in pancreas transplant rates was 2.9% in the US and 1.8% in Eurotransplant member countries. In the UK, from 2009 to 2016, a 0.5% annual decline in pancreas transplant activity occurred. The overall increase of non-US transplant numbers was due to the increased transplant activities of South American transplant centers where new pancreas transplant programs were started. Paradoxically, this decrease in annual pancreas transplant activity occurred commensurate with a burgeoning increase in incident rates for type 1 diabetes in children. Corresponding to the >30% decline in the total annual number of pancreas transplants being performed in the US in the past decade, fewer patients are being added to the waiting list, waiting times have increased, and wait list mortality for SPK transplant candidates has risen to 10% [3–6].

Only about 7 in 10,000 Type 1 and 4 in 1 million Type 2 patients with diabetes will ever receive a pancreas transplant in the US. Concurrent with the above trends, the overall number of active pancreas transplant centers are declining; only 10 centers in the US performed ≥20 pancreas transplants in 2017 and half of all centers perform <6 pancreas transplants in 2017 [Figure 4); many do not perform solitary pancreas transplants [3–6, 21]. For example, <50% of pancreas transplant centers perform PAKs and <25% actually perform PTAs in a given year. Only 12 centers in North America are certified by the American Society of Transplant Surgeons [ASTS) for pancreas transplant fellowship training [which previously required performing a minimum of 20 pancreas transplants per year). With the steady decline in volumes, many pancreas transplant programs are losing their ASTS fellowship training accreditation. Consequently, the ASTS recently lowered the annual threshold to 15 pancreas transplants per annum in order to permit centers to gain or maintain certification for fellowship training. Pancreas transplant programs comprise the vast majority of organ-specific transplant programs in the US that are most commonly cited by the UNOS Membership and Professional Standards Committee for not meeting minimum activity requirements. Low center volume is a problem in the Eurotransplant consortium as well. As a result, fewer surgeons are adequately trained in pancreas transplantation and many abdominal organ recovery surgeons are not experienced in pancreas organ recovery, which may influence pancreas procurement [18, 22]. Parenthetically, previous data have suggested that pancreas transplant outcomes are favorably influenced by increasing center volume [21].

This unintentional de-emphasis on pancreas transplantation represents a “crisis in confidence” and has the potential to threaten the existence of the procedure as a viable and effective therapeutic option. The national trend in decreasing numbers of pancreas transplants is disturbing and related to a number of factors. For example, the lack of a primary referral source from either diabetologists, endocrinologists or family medicine practitioners has hindered the growth of pancreas transplantation. Most pancreas transplant referrals are from nephrologists who refer patients with diabetes and chronic kidney disease to a transplant center for kidney rather than pancreas transplant evaluation. Ideally, a kidney transplant program with an active pancreas transplant component will identify potential candidates and appropriately offer them either SPK or PAK transplantation. However, this may not occur in programs that do not perform pancreas transplantation but would like to retain the patient for renal transplantation alone. The situation for PTA candidates is even worse as many diabetic patients actually have to circumvent the conventional diabetes care model in order to gain access to PTA.

Improvements in diabetes management, education and awareness; better insulin analogues and glucose sensors; sophisticated and more patient-friendly insulin pumps; and the promise of the artificial or bionic pancreas have all contributed to the diversion of interest away from pancreas transplantation [23]. For most patients with diabetes, the above advances are obvious improvements in therapy because they frequently result in a delay in the progression of diabetic complications. Consequently, lower rates of chronic kidney disease and delayed progression to other end-organ complications may result in fewer or later referrals for transplantation. This may be preferred for patients with diabetes that are able to avoid the need for transplantation. However, for those who might benefit from pancreas transplantation, late referral usually means that patients are older, may have a higher BMI, and may have additional co-morbidities that preclude successful pancreas transplantation. Additionally, most patients with diabetes have non-type 1 diabetes, which is generally, but incorrectly, regarded as a contraindication to pancreas transplantation.

SPK and PAK transplantation became Medicare-approved procedures on July 1st, 1999, after which time the American Diabetes Association included these treatment options within their evidence-based standards of care [24]. PTA became approved by Medicare on April 26, 2006, and despite coverage by Medicare and most primary insurers, subsequent validation by the American Diabetes Association has not occurred even though data on PTA spans several decades, thousands of transplants and chronicles steadily improving outcomes [2, 23, 24]. Because PTA is one of many treatment options available for diabetes mellitus, it stands in direct competition with conventional medical therapies and islet transplantation [23, 25, 26]. Many diabetes care professionals consider PTA to be a “radical”, aggressive, or overzealous therapy [requiring major surgery and lifelong immunosuppression) for a “benign” [yet life-shortening) disease. Other available treatment options are less invasive and, for that reason alone, more appealing to patients, diabetologists, endocrinologists, and primary care physicians. However, the long-term survival advantage in all three recipient categories of pancreas transplantation is not widely known or accepted. Even today, pancreas transplantation is often considered only as a life enhancing rather than a life-extending procedure.

For instance, the University of Wisconsin published their experience with 1000 SPK transplants with 22 year follow-up [27]. In this report, patient survival following SPK transplantation was superior to all other transplant options for type 1 diabetic patients with uremia. Patient survival following SPK transplant was even superior to uremic patients with Type 1 diabetes who underwent living donor kidney transplantation alone. This remarkable finding supports the contention that freedom from diabetes provides a survival advantage in the setting of kidney transplantation. Another study from the University of Minnesota evaluated outcomes in patients following living donor kidney transplantation who either underwent subsequent PAK transplant or were eligible for but did not undergo PAK because of financial or personal [but not medical) reasons. Patients who were ineligible for PAK because of comorbidity were excluded from analysis [28]. Although patient and kidney graft survival rates were not influenced [positively or negatively) by PAK transplant, 4-year renal function was significantly improved following PAK transplant in the setting of improved glycemic control. In a UNOS registry analysis from 1995–2010 of all adult patients registered either for an SPK or PAK transplant, the major findings were: 1. Patient survival for all transplanted patients was far superior to remaining on the waiting list; 2. Five-year patient survival was similar but 10-year patient survival was higher for SPK compared to PAK transplant recipients; 3. Receiving a PAK following either living or deceased donor kidney transplantation markedly improved long-term kidney graft survival rates compared to not receiving a pancreas graft; 4. Ten-year kidney graft survival rates were similar [61%) for recipients of either an SPK or living donor kidney alone transplants; and 5. Ten-year pancreas graft survival rates were 58.7% for SPK, 44.4% for pancreas after living donor kidney transplant, and 41.7% for pancreas after deceased donor kidney transplant [29]. However, the kidney graft survival rate was highest at 10 years [69.7%) for those surviving patients who received a living donor kidney followed by a sequential PAK transplant. Other studies have documented steadily improving outcomes following PAK transplant [29]. Based on these findings, it is logical to infer that both patient and renal graft longevity is maximized by achieving an insulin and dialysis-free state, whether this is accomplished either by an SPK transplant or a PAK transplant following [preferably) a living donor kidney transplant. Adding a pancreas to a kidney transplant [either simultaneously or sequentially) provides a survival advantage beyond kidney transplantation alone compared to all other treatments available to the uremia diabetic individual.

To further corroborate this viewpoint, recently published data have documented that since the inception of UNOS in 1987, 79, 198 life-years have been “saved” by SPK transplantation [4.6 life-years per recipient) and 14, 903 life-years by solitary pancreas transplants [2.4 life-years per recipient) in the US [30]. The perception that PTA is merely an invasive insulin replacement therapy is contrary to existing literature because this option confers a median survival time of 13.6 years compared to 8.0 years for patients who remain on the waiting list. The target patient population is also at significantly increased risk for multiple other morbidities attributed to diabetes that are not captured by data that address survival exclusively. Considering all of the data, the lack of wider application of pancreas transplantation to appropriately selected patients with complicated diabetes remains enigmatic and a missed opportunity.

It has been virtually overlooked that pancreas transplantation is now associated with an extremely low mortality rate, ranging from 3% at 1 year to 5–8% at 3 years in all 3 pancreas transplant categories [Table 1) [3–6]. At 3 years follow-up, pancreas graft survival [insulin-independence) rates are 85% for SPK transplant, 75% for PAK, and 72% for PTA recipients nationally. Following SPK transplantation, the national 3-year kidney graft survival rate is 91%. Many pancreas transplant recipients have been insulin-independent for >10 years and some for >20 years [12]. In every update of the IPTR spanning 30 years, patient and graft survival rates in all 3 categories of pancreas transplantation have continued to improve whereas early technical and immunological graft losses have continued to decline. However, the transplant community has become victimized by success; improving survival rates in all solid organ transplants have translated into higher thresholds that are implemented as metrics of acceptable performance. With fewer pancreas transplants being performed and fewer patients on the waiting list, the margin for error is much smaller and not all transplant centers remain actively involved in or committed to the practice of pancreas transplantation. Because of increased regulatory oversight, even large centers have responded by adopting a more risk adverse approach to transplantation in general and pancreas transplantation specifically. In addition, the marked decline in PAK transplants may be explained in part by overall improvements in outcomes and quality of life for patients receiving a kidney alone transplant, after which time they feel “well enough” to forego another transplant. Unfortunately, this is very shortsighted as these patients still face major issues despite a functioning kidney transplant; low quality of life and shortened lifespan because of their unchanged or even worsened diabetic state; and the potential for earlier kidney graft failure secondary to recurrent diabetic nephropathy [28, 29, 31].

Donor, Recovery and Preservation Issues

At present, pancreata are currently recovered for the intent to transplant in only 17% of deceased donors in the US [32]. Of these recovered organs, 25% are discarded so only 13% of deceased donors provide a pancreas that is actually transplanted. Some of these pancreata are sent for islet recovery, which in most cases does not result in islet transplantation. In other cases, aberrant hepatic artery anatomy or intestinal recovery may preclude pancreas recovery, although both of these conditions may be compatible with safe pancreas transplantation [22, 32]. Rates of pancreas utilization among Donor Service Areas vary from 0 to 50+% of donors. Pancreas utilization is influenced by limitations in acceptable warm and cold ischemia, which largely prevents widespread organ sharing and routine acceptance of donation after cardiocirculatory death [DCD) donors. However, recent reports have suggested that pancreas utilization in DCD donors is underutilized and a missed opportunity [32–34]. Moreover, because of logistical constraints, having a back-up patient at another center is problematic if the primary center chooses not to use the pancreas graft. In addition to donor quantity, donor quality has changed because donor age, BMI and proportion of donors who sustain brain death secondary to a cerebrovascular or cardiovascular etiology have all increased over time. The ideal pancreas donor ranges from 10–40 years of age, weighs 60–180 lbs., and sustains head trauma as a cause of brain death [32]. With the addition of cold ischemia <12 hours, these 4 core factors primarily determine the likelihood of success [and utilization) in pancreas transplantation. Having more than one of these factors outside the ideal range may have a significant detrimental effect on outcomes [35]. However, the recent surge in organ donation from young donors who sustain brain death secondary to anoxic encephalopathy following a drug overdose is rapidly becoming another source of “ideal” pancreas donors. Another viable alternative for pancreas recovery is the use of pediatric donors [below the age of 10 years or less than 30 kg in size) [36].

An additional aspect of donor pancreas under-utilization is the decline in experienced recovery teams that are able to adequately manage the donor, define and preserve the anatomy, and safely remove the pancreas intact without compromising any of the abdominal organs [22, 32]. The UNOS Pancreas Transplant Committee noted in a June 2014 Report to the Board of Directors that many pancreas discards were for reasons such as surgical error, surgical damage, and poor allograft description, with some of the discards attributed to the experience level of the recovery surgeon. The number of transplant surgeons actively involved in pancreas transplantation and donation is substantially lower than the number of kidney and/or liver transplant surgeons [18]. In addition, liver and kidney recovery usually take precedence over pancreas recovery among the abdominal organs, and the “liver” team is usually directing the recovery of abdominal organs. The lack of a “pancreas organ advocate” during the retrieval process may limit recovery and placement. In addition, having fewer patients on the waiting list may translate into greater selectivity with respect to donor organ offers. Finally, because of the constraints of cold ischemia coupled with Medicare regulations, pancreas recovery is rarely performed unless a specific recipient or receiving center has been identified preemptively.

Pancreas Allocation and Donor Risk Indices

The new Pancreas Transplant allocation policy [initiated on 10/31/2014) introduced recipient qualifying criteria for eligibility to accrue waiting time for SPK transplant, which limits the body mass index [BMI) cut-off for patients with diabetes mellitus and a C-peptide level >2.0 ng/ml. However, these new criteria are not supported by outcome or utilization data and have the potential to reduce overall pancreas transplant activity [3, 18]. Consequently, these qualifying criteria may be removed from the waiting list process. The overall decline in pancreas transplant activity is also temporally associated with the development and introduction of the Pancreas Donor Risk Index as a screening tool into clinical practice, in which multiple risk factors such as donor age, BMI, and cold ischemia time are integrated into a composite score to objectify donor assessment [37]. The Pancreas Donor Risk Index was designed using UNOS data to provide a predictive model to estimate post-transplant graft survival using pretransplant variables. While the Pancreas Donor Risk Index may accurately discriminate optimal versus marginal donor pancreas utilization at the extremes, there are insufficient data to validate its ability to stratify the average risk or suboptimal donor. Therefore, it has not been generally accepted into practice and is rarely used in making decisions about organ offers.

Surgical Techniques

Prior to the mid-1980s, a number of different techniques of exocrine drainage were investigated and many pancreas transplants were performed as segmental grafts [13–15]. During this developmental phase, exocrine drainage techniques were considered to be the “Achilles’ heel” of pancreas transplantation. From the late-1980s to 1995, the majority of pancreas transplants were performed as whole organ pancreatic grafts with systemic venous and bladder exocrine drainage [systemic-bladder technique). The advent of bladder drainage of the exocrine secretions revolutionized the safety and improved the success of pancreas transplantation. However, starting in 1995, a seismic shift from bladder to enteric exocrine drainage occurred coincident with improvements in immunosuppression, preservation techniques, diagnostic monitoring, general medical care, and the success of enteric conversion [13–15]. In the new millennium, most pancreas transplants have been performed as whole organ pancreatico-duodenal grafts with systemic venous delivery of insulin and enteric exocrine drainage [systemic-enteric technique) [1, 3, 5].

Enteric drainage usually refers to jejunal or ileal diversion of the exocrine secretions either with or without a diverting Roux limb[13–15]. Pancreas transplantation with primary enteric exocrine drainage accounted for 91% of SPK, 89% of PAK, and 89% of PTA cases in the US from 2010–2014 [3]. However, during this time, the systemic-bladder technique remained a viable option in selected cases and a preferred option at specific centers [1]. Of the cases performed with enteric drainage in the US, the proportions performed with a diverting Roux-en-y limb were 21% in SPK, 15% in PAK, and 15% in PTA cases [3, 5, 6]. To improve the physiology of pancreas transplantation, an innovative technique of portal venous delivery of insulin and enteric drainage of the exocrine secretions [portal-enteric technique) was developed in the early 1990s and refined over the past 20+ years [14, 15]. Currently, the proportions of enteric-drained cases performed with portal venous delivery of insulin are 22% in SPK, 11% in PAK, and 13% in PTA cases [3]. While the potential of the portal-enteric technique has not been fully realized, it has spawned a number of newer techniques of enteric exocrine drainage including duodenal or gastric diversion [14, 15]. A number of studies have demonstrated no major or consistent differences in outcomes for bladder-drained or enteric-drained pancreas transplants with either portal or systemic venous drainage [13–15]. The surgical complication rate also does not vary according to the type of transplant [SPK versus solitary pancreas transplantation). The incidence of duodenal segment leaks has been reported to be 5–20% in bladder-drained and 5–8% in enteric-drained pancreas transplants [13–15, 27, 38]. Increasing experience with enteric exocrine drainage is likewise associated with a decreased incidence of surgical complications. Although nearly all pancreas transplants are currently performed with one of the three above techniques, current philosophy dictates that the most appropriate technique to be performed is defined by both donor and recipient anatomy as well as the individual surgeon’s comfort level and experience.

Recipient Selection and Waiting List Considerations

The number of additions to the kidney-pancreas waiting list in the US steadily decreased from a high of 1935 in 2000 to 1228 in 2017 [5, 6]. In addition, the number of prevalent candidates [active and inactive) on either the kidney-pancreas or the pancreas waiting lists steadily decreased from 3499 in 2002 to 2518 in 2018. The number of active candidates has decreased by more than 50%, from 2776 in 2002 to 1039 in 2018. In spite of fewer patients on the active waiting list, median waiting times for kidney-pancreas transplantation have continued to increase and range from 1.2 to 4 years depending on blood type. In the past decade, the proportion of recipients who are older, African American, have a higher BMI, or are characterized as having type 2 diabetes have all increased [1, 3, 5, 6]. Recent studies have reported that pancreas transplantation can be successfully performed in selected patients with non-type 1 diabetes [7–10, 39]. In 2013, 25.7% of candidates on the waiting list were ≥ age 50 years, 19.7% were African American [11.4% were Hispanic), 19.1% had a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, and 8.9% were classified as having type 2 diabetes. This positive trend in successfully transplanting higher risk patients that were excluded from receiving a pancreas transplant in the past has become possible secondary to significant advances in surgical techniques, immunosuppression and post-transplant medical management strategies. Unfortunately, guidelines for liberalizing recipient criteria have not been widely promulgated or accepted by the medical and surgical communities.

Immunosuppression and Immunological Outcomes

The history of pancreas transplantation is a remarkable success story of the last 50 years that is closely linked to advances in biological and immunosuppressive drug therapies [1–3]. Progress in surgical techniques and clinical immunosuppression have led to improving results in vascularized pancreas transplantation that are attributed to reductions in technical failures and immunologic graft losses over time, respectively [1–6, 40]. The use of biologic agents for induction and “cocktails” of multiple agents with varying mechanisms of action for maintenance therapy have become the standard of immunosuppression following pancreas transplantation [1–8, 40–43]. Immunosuppressive strategies in pancreas transplantation have evolved from experience extrapolated in kidney transplantation because the majority are performed as SPK transplants. Unlike other types of solid other transplants, pancreas transplantation provides an excellent paradigm to study acute rejection because insulin-requiring diabetic patients represent a relatively homogeneous patient population who historically had a high rate of acute rejection possibly because of variable drug absorption [from impaired gastric emptying] or heightened immune responsiveness from the presumed auto-immune etiology of diabetes. In addition, adding a pancreas to a kidney allograft appears to increase the risk of acute rejection, which may be related to the inherent immunogenicity of the pancreas graft or perhaps because of increased antigen load or altered antigen presentation in the recipient. [43–46] Consequently, SPK transplantation has been associated with a higher rate of acute rejection compared to other transplanted organs whereas solitary pancreas transplantation may have even a higher rate of acute rejection secondary in part to limitations in monitoring the pancreas graft. [2, 23, 47]

At present, 90% of SPKT recipients receive antibody induction, with nearly 80% receiving a depleting antibody agent. [3–6, 43] Depleting antibody induction using a biological agent has become a cornerstone of contemporary immunosuppression in pancreas transplantation. The rationale for the evolving trend in depleting antibody induction is to provide a more potent immunosuppressive umbrella of protection for maintenance therapies that incorporate minimization strategies such as corticosteroid elimination or avoidance, calcineurin inhibitor reduction or withdrawal, or even calcineurin inhibitor monotherapy. According to International Pancreas Transplant Registry data, rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin and alemtuzumab are currently the two most commonly used antibody induction agents in SPK transplantation. One-year rates of acute rejection have steadily decreased and are currently in the 5–20% range depending on pancreas transplant category, case mix and immunosuppressive regimen. [3, 4, 6] Historically, these regimens were based primarily on efficacy in the prevention of acute rejection. However, the amount, frequency, and duration of various agents must be tailored according to individualized risk factors. Although nearly all possible combinations of maintenance immunosuppressive protocols have been used, nearly 80% of patients in the recent past have received maintenance therapy with the tacrolimus/mycophenolate combination, and 30–50% have undergone either early or delayed corticosteroid withdrawal without adverse consequences. [3–5, 40–43] The current one-year rate of immunological pancreas graft loss is 1.8% in SPK transplant recipients. [3, 4, 6] Although depleting antibody induction strategies are associated with lower rates of acute rejection compared to either no induction or non-depleting antibody induction, somewhat surprisingly no major differences in mid-term patient or graft survival rates or graft function have been noted according to method of antibody induction. As early graft survival rates have improved because of lower rates of both acute rejection and immunological graft loss, the consequences of chronic rejection have become more important. [45] Ultimately, the development of a non-nephrotoxic, non-diabetogenic, and non-gastrointestinal toxic maintenance immunosuppressive regimen is highly desirable to improve outcomes and quality of life in pancreas transplant recipients. Immunosuppressive strategies will continue to evolve to safer, less toxic, and more targeted therapies with similar or improved efficacy long-term compared to currently available regimens.

Pancreas Versus Islet Transplantation

PTA and islet transplantation are usually linked together as equivalent beta-cell replacement strategies for patients with diabetes in the absence of chronic kidney disease, both of which are then considered as investigational therapies rather than as standards of care. [24–26] Unfortunately, this characterization is not accurate and confusing to patients who might benefit from PTA. In 2000, Shapiro, et al, published their landmark paper on successful islet transplantation in seven patients using the “Edmonton” protocol. [48] Although islet transplant outcomes have continued to improve, overall graft function and durability have not matched those achieved for PTA. [2, 23, 30, 49] In fact, complete and stable long-term insulin independence is uncommon and, in current studies, is not even a primary endpoint following islet transplantation. In addition, “successful” islet transplantation frequently requires more than one donor pancreas. Unlike PTA, islet transplantation remains in a developmental phase with slightly improved success rates only reported in the new millennium in a few hundred cases. At present, islet transplantation is not approved by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services in the US, but is paid for by public health systems in some other countries. Similar to islet transplantation, other novel diabetes management options such as the “bionic pancreas”, immunotherapy, gene therapy and stem cell therapy remain innovative yet unrealized investigational ventures that have overshadowed enthusiasm for PTA. Moreover, none of these promising therapies have the current established successful track record of PTA but are being touted as potential “cures” for diabetes. Yet, the mere prospect of potential effectiveness with non- or less-invasive treatment options has subjugated the proven success of PTA.

Summary and Conclusion

In spite of the increasing success of pancreas transplantation, it seemingly has been relegated to a secondary or even tertiary role in the management of diabetes. Overall advances in diabetes management, education and awareness; newer insulin analogues and glucose sensors; state of the art, portable, and more patient-friendly insulin pumps; and the potential of the artificial or bionic pancreas have all contributed to the diversion of interest away from pancreas transplantation as a viable treatment option in the absence of uremia. Pancreas transplantation has been performed with a high and increasing level of success for 30 years. Consequently, it is logical to assume that the diabetes care community will not change their perception of pancreas transplant as a “last resort” form of therapy. However, in spite of recent trials and tribulations, pancreas transplantation remains an important therapeutic alternative for selected patients with hyperlabile or “complicated” diabetes who cannot be managed optimally with conventional insulin therapy. Ultimately, a more reliable source of high quality organs, less diabetogenic [and less toxic] immunosuppression, and lower surgical morbidity are needed in order to propel pancreas transplantation into the forefront of widely accepted management strategies for patients with insulin-requiring diabetes.

Because the healthcare landscape is a moving target, new and innovative ways to educate the public and medical community are needed to correct misperceptions about pancreas transplantation. In addition to conducting outreach sessions with endocrinologists and diabetologists, the pancreas transplant community needs to reach the vast number of family practice physicians who manage the majority of patients with diabetes. Regarding “promotion” of pancreas transplantation, recent data and new evidence needs to be disseminated using not only conventional publications but also social networking, medical websites, media campaigns and through re-engaging the American Diabetes Association. Ultimately, the most important factor for more widespread application of pancreas transplantation remains education, including ongoing engagement of patients with diabetes and health care professionals. Various types of media and social networks could and should function as ideal platforms for recipients of successful pancreas transplants to spread the message that complete and durable insulin-independence is an attainable goal in the majority of cases.

From a transplant community perspective, greater emphasis needs to be placed on improving pancreas recovery rates including removing financial disincentives, facilitating broader sharing with charter aircraft to minimize cold ischemia, implementing pancreas donor advocates, expanding acceptable donor criteria to include selected donation after circulatory death donors and pediatric donors, and assuring that abdominal organ recovery surgeons are experienced in pancreas recovery. In addition, liberalizing recipient selection to include older patients as well as non-type 1 diabetics with uremia and expanding indications for solitary pancreas transplantation (PAK and PTA) will increase the size of the waiting list, which ultimately drives pancreas utilization. Recent studies have suggested that even at active pancreas transplant centers, there are a number of patients who are either on the kidney waiting list or whom have received successful kidney alone transplantation who may benefit from either SPK or PAK transplantation. Having a multidisciplinary team in place to specifically evaluate uremic diabetic individuals for pancreas transplantation can facilitate the “pipeline” by effectively triaging more potential candidates, increase “internal conversions” from the kidney to the SPK transplant waiting list, and identifying patients who may benefit from PAK transplantation. [50] Rather than relying on the diabetes care and nephrology communities for access to potential pancreas transplant candidates, kidney transplant centers must become accountable for providing the opportunity for pancreas transplantation. For SPK transplant recipients with potential living donors, one might consider having the living donor donate their kidney to someone else on the kidney waiting list in exchange for priorization on the SPK waiting list. Alternatively, a more assertive approach to PAK transplantation may be warranted. In spite of recent challenges, pancreas transplantation remains an important therapeutic option for selected patients with hyperlabile or “complicated” diabetes who cannot be managed optimally with conventional insulin therapy.

Abbreviations

ASTS: American Society of Transplant Surgeons

BMI: Body Mass Index

DCD: Donation after Cardiocirculatory Death

IPTR: International Pancreas Transplant Registry

PAK: Pancreas after Kidney

PTA: Pancreas Transplant Alone

SPK: Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney

UK: United Kingdom

UNOS: United Network for Organ Sharing

US: United States

References

- Gruessner RW, Gruessner AC (2013) The current state of pancreas transplantation. Nat Rev Endocrinol 9: 555–562. [crossref]

- Gruessner RW, Gruessner AC (2013) Pancreas transplant alone: a procedure coming of age. Diabetes Care 36: 2440–2447. [crossref]

- Gruessner AC, Gruessner RW (2016) Pancreas Transplantation of US and Non-US Cases from 2005 to 2014 as Reported to the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) and the International Pancreas Transplant Registry (IPTR). Review of Diabetic Studies 13: 35–58.

- Updated International Pancreas Transplant Registry (IPTR) data, Angelika Gruessner (personal communication); United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS).

- Kandaswamy R, Stock PG, Gustafson SK, Skeans MA, et al. (2018) OPTN/SRTR 2016 Annual Data Report: Pancreas. Am J Transplant 18: 114–171. [crossref]

- Gruessner AC, Gruessner RWG (2018) Pancreas Transplantation for Patients with Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in the US – A Registry Report. Gastroenterol. Clin N Am 47: 417–441.

- Orlando G, Stratta RJ, Light J (2011) Pancreas transplantation for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 16: 110–115. [crossref]

- Stratta RJ, Rogers J, Farney AC, et al. (2015) Pancreas transplantation in C-peptide positive patients: Does “type” of diabetes really matter? J Am Coll Surg 220: 716–727.

- Gruessner AC, Laftavi MR, Pankewycs O, Gruessner RWG (2017) Simultaneous Pancreas and Kidney Transplantation – Is it a Treatment Option for Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus? An Analysis of the International Pancreas Transplant Registry. Current Diabetes Reports 17: 44 (1–9).

- Rogers J, Farney AC, Orlando G, Iskandar SS, Doares W, et al. (2014) Pancreas transplantation: The Wake Forest experience in the new millennium. World J Diabetes 5: 951–961. [crossref]

- Redfield RR, Scalea JR, Odorico JS (2015) Simultaneous pancreas and kidney transplantation: current trends and future directions. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 20: 94–102.

- Gruessner AC, Gruessner RWG (2016) Long-term Outcome after Pancreas Transplantation – A Registry Analysis. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 21: 377–385.

- Boggi U, Amorese G, Marchetti P (2010) Surgical techniques for pancreas transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 15: 102–111. [crossref]

- Rogers J, Farney AC, Orlando G, Farooq U, Al-Shraideh Y, et al. (2014) Pancreas transplantation with portal venous drainage with an emphasis on technical aspects. Clin Transplant 28: 16–26.

- El Hennawy H, Stratta RJ, Smith F (2016) Exocrine Drainage in Vascularized Pancreas Transplantation in the New Millennium. World J Transplant 6 (2): 255–71. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v6.i2.255.

- Boggi U, Signori S, Vistoli F, et al. (2012) Laparoscopic robot-assisted pancreas transplantation: First world experience. Transplantation 93: 201–206.

- Cantrell LA, Oberholzer J (2018) Robotic pancreas transplantation: the state of the art. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 23: 423–427. [crossref]

- Stratta RJ, Gruessner AC, Odorico JS, Fridell JA, Gruessner RW (2016) Pancreas Transplantation: An Alarming Crisis in Confidence. Am J Transplant 16: 2556–2562. [crossref]

- Gruessner AC, Gruessner RW (2014) Declining Numbers of Pancreas Transplants but Significant Improvements in Outcome. Transplant Proc 46: 1936–1937.

- Kopp W, van Meel M, Putter H, Samuel U, Arbogast H, et al. (2017) Center Volume is Associated with Outcome after Pancreas Transplantation within the Eurotransplant Region. Transplantation 101: 1247–1253.

- Alhamad T, Malone AF, Brennan DC, Stratta RJ, Chang SH, et al. (2017) Transplant Center Volume and the Risk of Pancreas Allograft Failure. Transplantation 101: 2757–2764. [crossref]

- Ausania F, Drage M, Manas D, Callaghan CJ (2015) A registry analysis of damage to the deceased donor pancreas during procurement. Am J Transplant 15: 2955–2962. [crossref]

- Niederhaus SV (2015) Pancreas transplant alone. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 20: 115–120. [crossref]

- Robertson RP, Davis C, Larsen J, Stratta R, Sutherland DE (2000) ADA Position Statement: Pancreas and islet transplantation for patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care 23: 112–116.

- Niclauss N, Morel P, Berney T. (2014) Has the Gap Between Pancreas and Islet Transplantation Closed? Transplantation 98: 593–599.

- Moassesfar S, Masharani U, Frassetto LA, et al. (2016) A Comparative Analysis of the Safety, Efficacy, and Cost of Islet Versus Pancreas Transplantation in Nonuremic Patients with Type 1 Diabetes. Am J Transplant 16: 518–526.

- Sollinger HW, Odorico JS, Becker YT, D’Alessandro AM, Pirsch JD (2009) One thousand simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplants at a single center with 22-year follow-up. Ann Surg 250: 618–630.

- Kleinclauss F, Fauda M, Sutherland DER, Kleinclauss C, Gruessner RW, et al. (2009) Pancreas after living donor kidney transplants in diabetic patients: Impact on long-term kidney function. Clin Transplant 23: 437–446.

- Fridell JA, Niederhaus S, Curry M, Fox A: Odorico J (2018). The Survival Advantage of Pancreas after Kidney Transplantation. Am J Transplant 18: in press

- Rana A, Gruessner A, Agopian VG, Khalpey Z, Riaz IB, et al. (2015) Survival benefit of solid-organ transplant in the United States. JAMA Surg 150: 252–259. [crossref]

- Weiss AS, Smits G, Wiseman AC (2009) Twelve-Month Pancreas Graft Function Significantly Influences Survival Following Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 988–995.

- Fridell J, Rogers J, Stratta RJ (2010) The pancreas allograft donor: Current status, controversies, and challenges for the future. Clin Transplantation 24: 433–449.

- Muthusamy AS, Mumford L, Hudson A, Fuggle SV, Friend PJ (2012) Pancreas Transplantation from Donors after Circulatory Death from the United Kingdom. Am J Transplant 12: 2150–2156.

- Kopp WH, Lam HD, Schaapherder AFM, et al. (2018) Pancreas Transplantation with Grafts from Donors Deceased after Circulatory Death: 5 years Single-Center Experience. Transplantation 102: 333–339.

- Finger EB, Radosevich DM, Dunn TB, Chinnakotla S, Sutherland DE, et al. (2013) A composite risk model for predicting technical failure in pancreas transplantation. Am J Transplant 13: 1840–1849. [crossref]

- Fernandez L, Turgeon NA, Odorico JS, et al. (2004) Superior Long-Term Results of Simultaneous Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation from Pediatric Donors. Am J Transplant 4: 2093–2101.

- Axelrod DA, Sung RS, Meyer KH, et al. (2010) Systematic Evaluation of Pancreas Allograft Quality, Outcomes, and Geographic Variation in Utilization. Am J Transplant 10: 837–845.

- Sutherland DE, Gruessner RW, Dunn DL, Matas AJ, Humar A, et al. (2001) Lessons learned from more than 1,000 pancreas transplants at a single institution. Ann Surg 233: 463–501. [crossref]

- Wiseman AC, Gralla J (2012) Simultaneous Pancreas Kidney Transplant Versus Other Kidney Transplant Options in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 656–664.

- Odorico JS, Sollinger HW (2002) Technical and immunosuppressive advances in transplantation for insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. World J Surg 26: 194–211.

- Singh RP, Stratta RJ (2008) Advances in immunosuppression for pancreas transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 13: 79–84. [crossref]

- Heilman RL, Mazur MJ, Reddy KS (2010) Immunosuppression in simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation: progress to date. Drugs 70: 793–804. [crossref]

- Stratta RJ, Farney AC, Rogers J, Orlando G (2014) Immunosuppression for Pancreas Transplantation with an Emphasis on Antibody Induction Strategies: Review and Perspective. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 10: 117–132.

- Reddy KS, Davies D, Ormond D, Tuteja S, Lucas BA, et al. (2003) Impact of acute rejection episodes on long-term graft survival following simultaneous kidney-pancreas transplantation. Am J Transplant 3: 439–444. [crossref]

- Humar A, Khwaja K, Ramcharan T, Asolati M, Kandaswamy R, et al. (2003) Chronic rejection: the next major challenge for pancreas transplant recipients. Transplantation 76: 918–923. [crossref]

- Troxell ML, Koslin DB, Norman D, et al. (2010) Pancreas allograft rejection: analysis of concurrent renal allograft biopsies and posttherapy follow-up biopsies. Transplantation 90: 75–84.

- Gruessner RWG, Sutherland D, Kandaswamy R, et al. (2008) Over 500 solitary pancreas transplants in nonuremic patients with brittle diabetes mellitus. Transplantation 85: 42–47.

- Shapiro AM, Lakey JR, Ryan EA, et al. (2000) Islet transplantation in seven patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus using a glucocorticoid-free immunosuppressive regimen. N Engl J Med 343: 230–38.

- Schuetz C, Anazawa T, Cross SE, Labriola L, Meier RPH, et al. (2018) β Cell Replacement Therapy: The Next 10 Years. Transplantation 102: 215–229. [crossref]

- Scalea JR, Sultan S, Lamos EM, Bartlett ST, Barth RN (2018) Improvement in Pancreas Transplant Evaluation and Surgical Volume Using a Multidisciplinary Approach. Am J Transplant 18: 1295–1296.