Abstract

Arterial calcification is an independent predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in end-stage renal disease. CD73, a GPI-linked plasma membrane ecto-enzyme encoded by NT5E gene, is involved in vascular calcification inhibition. Mutations in NT5E gene are linked to premature onset of arterial and distal joint calcification in families, possibly due to the downstream effects of CD73 on tissue-non-specific-alkaline-phosphatase (TNAP), an important enzyme in the calcification process. We hypothesised that common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in NT5E gene may contribute to the risk of calcifcation in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), and explored rs4373339C>T, rs2229523A>G, rs10944128A>G SNPs role on bone mineral density (BMD) and aortic pulse wave velocity (aPWV), the markers of calcification. 302 CKD patients from LACKABO study with calcification markers, haemodynamic and genetic data were studied. The mean age of the CKD cohort was 57.8 ± 15.6 years. rs2229523 SNP showed allele specific differences in BMD, a marker of vascular bone axis; and AA genotype was associated with lower levels of BMD at initial (93.9 versus 125.7 mg/cm3, p = 0.0182) and follow-up (80.4 versus 109.4 mg/cm3, p = 0.0126) screening. These relationships held after adjustments for known confounders of the calcification process. Similar relationship was observed for aPWV with rs2229523 AA genotype. We demonstrated for the first time a non-synonymous variant modulates BMD. These findings offer new insights into the bone-vascular axis in CKD, identifying a novel role for CD73 of potential clinical importance, but further studies are needed to expound the biology driving these observations.

Keywords

NT5E gene, polymorphisms, bone mineral density, aortic pulse wave velocity, and chronic kidney disease

Introduction

Arterial calcification is a strong and independent predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [1], and is associated with bone loss, fractures, and arterial stiffening [2–4]. Within chronic kidney disease (CKD), vascular calcification is an aggregate of both intimal (atherosclerotic) and medial calcification [5], with a high prevalence of risk factors for both in this population [6]. Previously, this phenomenon was believed to result from the passive precipitation of calcium-phosphorus product in plasma. Over the past two decades, however, experimental studies suggest that it is actually an active, tightly-regulated, cell-mediated process, resembling bone and/or cartilage formation, which can be modulated by both activators and inhibitors [7, 8]. Genetic studies suggest that certain endogenous inhibitors are essential for the normal suppression of this process in arteries and soft tissues [7] and that a deficiency in any of these inhibitors is sufficient to unleash calcification.

Pyrophosphate (PPi) is one of the most important of these inhibitors, produced in almost all extracellular matrices [9] and shown to inhibit calcification through direct physiochemical inhibition of hydroxyapatite formation in vitro [10]. Deficiency in PPi caused by inherited mutations in the ENPPI gene, which encodes the PPi-generating enzyme, ectonucleotide-pyrophosphatase-phosphodiesterase (ENPPI), result in rare calcification disorders like generalised arterial calcification of infancy (GACI, OMIM: 20800) [11], and the ENPP1 genotype has been shown to associate with higher coronary artery calcification score in patients with ESRD [12]. Mutations in NT5E gene, which encodes CD73, have also been implicated in pyrophosphate regulation and associate with extensive lower extremity arterial calcification and small joint capsule calcification in some families (arterial calcification due to CD73 deficiency (ACDC) or calcification of joints and arteries (CALJA), OMIM: 211800) [11, 13–17]. Pyrophosphate regulation is believed to play a particularly important role in the development of vascular calcification in CKD, as suggested by the negative association between plasma PPi levels and quantity of vascular calcification in ESRD [18]. Therefore, genes associated with pyrophosphate deficiency, would be ideal candidates to explore further. Though mutations in NT5E gene have been implicated in conditions like ACDC or CALJA, the most common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in this gene have not been investigated in the general CKD population.

The NT5E gene (NM_002526.3) is located on chromosome 6q14-q21, and encodes a 574 amino-acid glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-linked plasma membrane ecto-enzyme known as CD73. CD73 binds extracellular AMP and converts it to adenosine and inorganic phosphate [19] and is expressed widely in different tissues [20]. Within the vasculature, it is expressed in endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts [20], as well as in circulating lymphocytes [21]. CD73 indirectly inhibits calcification through its effects on tissue-non-specific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP) expression, with a resultant reduction in PPi hydrolysis [12]. Adenosine, released through CD73 activity, is thought to be the relevant mediator here, through its inhibitory effects on TNAP expression [13]. The relationship between ENPP1 and CD73 in PPi regulation is well described by Rutsch et al. [22].

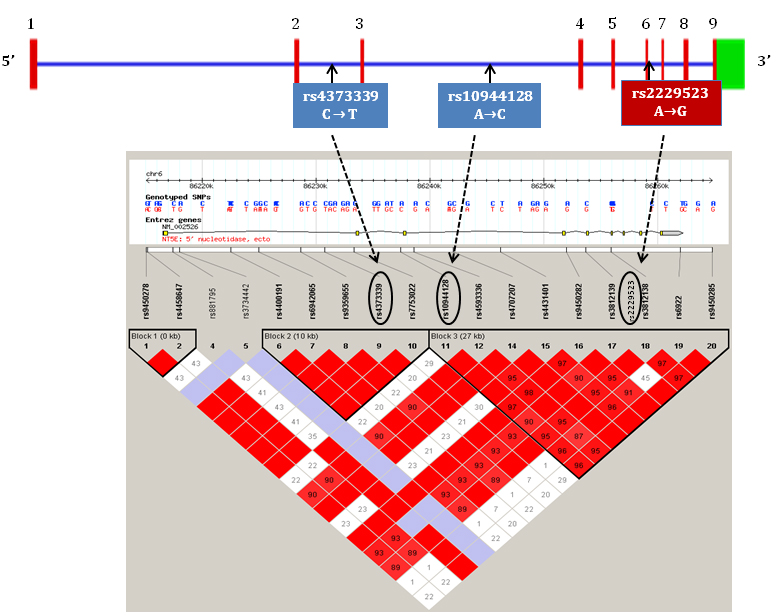

We hypothesised that the common polymorphisms in NT5E gene contribute to the development of calcification and associate with related indices such as bone loss and arterial stiffness. We therefore explored the relationship of polymorphic variation in NT5E with calcification (coronary artery, CAC, and aortic, AC, scores), bone mineral density (BMD), and aortic stiffness (aPWV) in pre-dialysis CKD patients. Three tagging SNPs (tagSNPs) selected from two large linkage disequilibrium (LD) blocks due to their high r2 values of >0.8, covering 37kb region were genotyped. Of the three SNPs, two were intronic (rs4373339 C>T, rs10944128 A>C) and one was a non-synonymous coding SNP (rs2229523 A>G) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of NT5E gene with exons, introns, LD blocks and genotyped tagSNPs.

Material and Methods

Patients

Pre-dialysis CKD patients (stage 2–5) enrolled in The London Arterial Calcification, Kidney and Bone Outcomes (LACKABO) study, a single-centre prospective study aimed to assess the natural history of vascular calcification were studied [23]. Men were included if their serum creatinine was greater than or equal to 150 μmol/l and women were included if their serum creatinine was greater than or equal to130 μmol/l. All participants were 18 years or older. Patients were excluded if on renal replacement therapy. 302 patients were originally recruited into this study at baseline. However, arterial calcification scores and genetic data were available for only 229 and 279 participants, respectively, unless otherwise stated in the tables. Therefore, the primary phenotype-genotype analysis was performed on these participants, hence the number of subjects differed for each analysis.

After a mean of 49 months, participants were invited again to have follow-up scans and just over 50% of patients attended. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki, ethical approval was obtained from the Local Research Ethics Commitees and written informed consent provided by all study participants.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

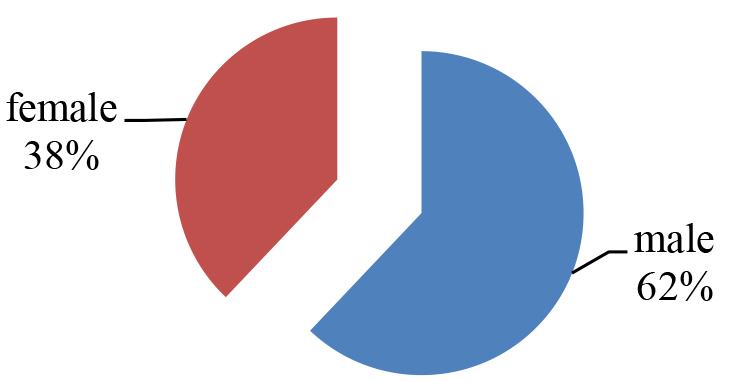

Demographic data including age, gender, height and weight were recorded and BMI calculated at study entry (baseline). Past and present medical history, prescribed medications and cardiovascular risk factors were also noted. Majority of the patients were Caucasians (72.5%) and others included were Asians (12.3%), Black (9.5%), Chinese (1.7%) and of mixed ethnicity (4%).

Arterial calcification phenotype measurements

Coronary artery calcification (CAC) and aortic calcification (AC)

Coronary artery and aortic calcification was measured using Electron Beam Computed Tomography (EBCT). Briefly, the scanning was performed at the Royal Brompton Hospital, London using a C-150 scanner (GE-Imatron) with a 100 msec scanning time and a single slice of 3mm for the section between the carina to the level of the diaphragm. 36 to 40 slices were obtained during a single-breathhold. Patients were exposed to an overall radiation dose (0.9 msv), which is equivalent to approximately one third of the annual exposure from background radiation. CAC and AC scores were determined from the computed pixels of calcification. A pixel was defined as having a minimal density of 130 Hounsefield units (HU) and a surface area of >0.51mm2. Calcification was defined as a plaque of at least 3 contiguous pixels of calcification. Calcification scores were recorded in both the aorta and in individual coronary arteries including the left circumflex, left main stem, left anterior descending, and right coronary artery. The total coronary calcification score was determined by averaging the four individual arterial scores and this value was used for subsequent analysis.

There are no agreed cut-off values for EBCT calcification score categories. We therefore, used the 5 numerical categories used by Shaw et al [24]. and adapted it by applying a descriptive term to each category (ranging from low to very high), based on category interpretations from a recent systematic review [25]: 0–10 (low); 10.1–100 (moderate); 101–400 (moderately high); 400–1000 (high); >1000 (very high).

Bone mineral density (BMD)

BMD was assessed in 238 patients from individual EBCT scans described above, which were performed to assess aortic calcification. The average of 3 lumbar vertebrae on each EBCT scan was used to calculate BMD and used in the subsequent analysis.

Blood pressure (BP) and aortic pulse wave velocity (aPWV)

All measurements were obtained in a quiet temperature-controlled room. Peripheral blood pressure and heart rate were recorded from the brachial artery of the non-dominant arm using validated oscillometric technique (HEM-705CP; Omron Corporation). aPWV, defined as the speed of pulse waves travelling along the length of an artery, was determined from sequential readings of ECG-gated carotid and femoral artery waveforms using SphygmoCor system [26]. All measurements were made in duplicate and average values were used for analysis.

Biochemical markers

Blood samples were obtained to measure vascular calcification-related biomarkers including blood lipids, glucose, serum creatinine, urea, calcium, phosphate. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated from serum creatinine using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease method [27].

Genetic analysis

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was isolated using standard method and stored at -80oC for genetic analysis. Allelic discrimination was performed using AB17500 Taqman system and Taqman SNP genotyping assays (Applied Biosystems). Briefly, each assay contains two fluorescent-labelled probes corresponding to the alleles harboured by the SNP of interest. The probes carry reporter fluorescent dyes that are cleaved and released into solution during PCR by Taq polymerase when the corresponding DNA is being replicated. The colour of the released dye identifies the genotype; this is detected when the assay is analysed using the accompanying Taqman software (version 2.0.4).

For genotyping, 1ng of gDNA was mixed with 2x Taqman Universal Master Mix, No AmpErase UNG, labelled probe (FAM and VIC dye-labelled) and MQ H2O to a total volume of 15 µL for each sample. This mixture was dispensed into a standard MicroAMPTM Optical 96-Well Reaction Plate, and amplified using Taqman real-time PCR system. Postive and negative standards were also included on each plate. The PCR conditions consisted of a pre-PCR read at 60oC (1min), a holding stage at 95oC (10min), followed by 46 PCR cycles (15 secs at 95 oC, 1min at 60 oC for each cycle) and a final post-PCR read at 60oC (1min). Allelic discrimination was carried out by detecting allele specific fluorescence and data was analysed off-line with the sequence detectionsoftware. If the genotype clusters were unambiguous, manual calling was performed or the sample was re-genotyped for that SNP. As small amounts of DNA was available in some patients, the company recommended reaction mixture concentrations were adjusted for all assays and all samples. These concentrations have been standardised and used in our previous genetic studies (>95% success rate).

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS (version 25.0) and GraphPad Prism (version 5.0) software. All variables were checked for normal distribution and skewed variables were transformed before further analysis. Normally distributed data are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD), skewed data as median and inter-quartile range (IQR) and as geometric means, and categorical data as percentages. Oneway analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to investigate the genotype differences in phenotype(s), and Welch’s t-tests compared average BMD and aPWV differences between the two homozygous allele carriers. And since rs2229523 SNP showed a dose dependent pattern of inheritance on BMD, SNP association was tested assuming a standard additive model using a regression analysis that adjusted for known factors that influence the calcification process (age, gender, MAP, eGFR). Paired t-tests were performed to see changes in BMD and aPWV after 49 months. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant, in all statistical tests.

Results

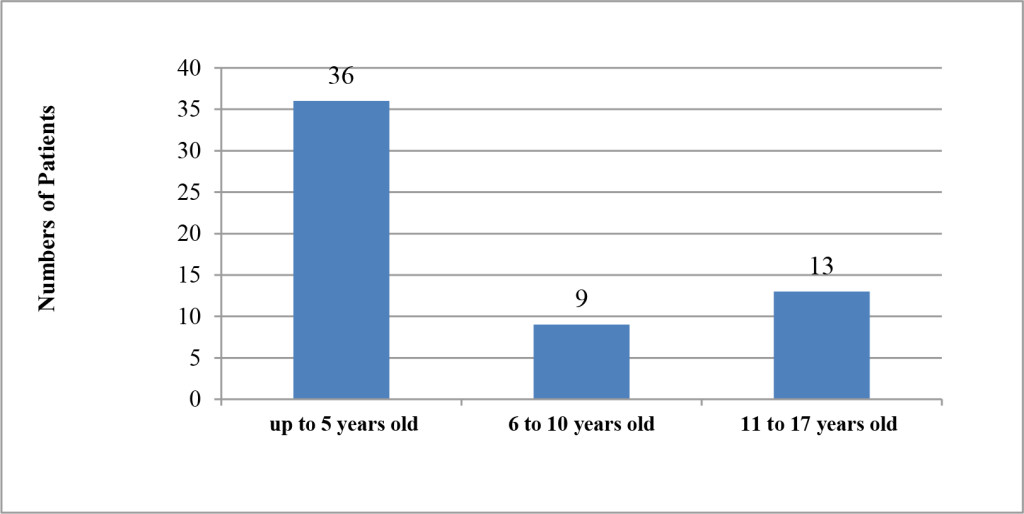

Demographic, clinical and calcification-related characteristics at baseline

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of the LACKABO study participants are given in Table 1. The mean age was 57.8 years (age range: 19–91) and the eGFR average was 40.4 ml/min, consistent with pre-dialysis stage 3 CKD. As expected, 80% of these patients were hypertensive, 20% had diabetes and 8% had a past incident of myocardial infarction. About half of these CKD patients were also on cardiovascular drugs; hence the lipid profile and blood pressures were in the normal range (Tables 1–2).

Table 1. Clinical and demographic characteristics in 302 subjects.

|

Parameters |

Mean ± SD |

|

Demographics |

|

|

Age (years) |

57.8 ± 15.6 |

|

Gender (M/F) |

221/81 |

|

Height (m) |

1.71 ± 0.1 |

|

Weight (kg) |

81.1 ± 18.8 |

|

BMI (kg/m2) |

27.6 ± 5.5 |

|

Renal parameters |

|

|

eGFR (mL/min) † |

39.2 (25.8–50.9) |

|

Calcium (nM) |

2.27 ± 0.2 |

|

Phosphate (nM) |

1.3 ± 0.8 |

|

CV Risk Factors |

|

|

Current smokers (%) |

13.2 |

|

Hypertension (%) |

80.1 |

|

Diabetes (%) |

20.2 |

|

Previous myocardial infarction (%) |

7.6 |

|

Total cholesterol (mmol/l) |

4.7 ± 1.15 |

|

HDL cholesterol (mmol/l) |

1.5 ± 0.5 |

|

LDL cholesterol (mmmol/l) |

2.4 ± 1.0 |

|

Triglyceride (mmol/l) |

2.5 ± 6.98 |

|

Blood glucose (mmol/l) |

5.7 ± 2.8 |

|

NTProBNP (pmol/l) |

74.5 ± 361 |

|

C-reactive protein (mg/L) † |

1.57 (0.72–3.61) |

|

CVD medications (%) ACE Inhibitor Aspirin α-Blocker α2-Blocker β-Blocker Ca2+ Channel Antagonists Diuretics Nitrates Statins Warfarin |

47.4 37.7 19.2 39.7 30.8 34.1 52.6 5.3 53.0 4.0 |

BMI = body mass index; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate;

CVD = cardiovascular disease; BP = blood pressure; HDL = high density lipoprotein;

LDL = low density lipoprotein.

† = median with interquartile range.

Table 2. Vascular calcification and other related measures.

|

Parameters |

Mean ± SD |

|

Arterial Calcification Scores (n = 229) |

|

|

Coronary Calcification Grade (%) Low (0–10) Moderate (10.1–100) Moderately high (100.1–400) High (400.1–1000) Very High (>1000) |

40 18.3 18.8 10.8 12.1 |

|

Total Coronary Calcification Score (baseline, n = 240)† |

46.6 (0.0–344.4) |

|

Aortic calcification score (baseline, n = 241)† |

52.7 (6.2–397.1) |

|

Blood Pressure and Arterial Stiffness (n = 302) |

|

|

Peripheral systolic BP (mmHg) |

132.7 ± 18.9 |

|

Peripheral diastolic BP (mmHg) |

79.1 ± 11.4 |

|

Peripheral pulse pressure (mmHg) |

53.6 ± 16.7 |

|

Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) |

97.0 ± 12.0 |

|

Heart rate (bpm) |

68.8 ± 12.9 |

|

aPWV (m/s; baseline, n = 217) |

9.06 ± 3.0 |

|

aPWV (m/s; follow up, n = 88) |

8.24 ± 3.8 |

|

Vascular-Bone Axis Marker (n = 238) |

|

|

Bone mineral density (mg/cm3; baseline, n = 238)† |

120.8 (96.4–152) |

|

Bone mineral density (mg/cm3; follow up, n = 159)† |

103.2 (79–137.2) |

BP = blood pressure; aPWV = aortic pulse wave velocity.

† = median with interquartile range.

The results for arterial calcification and other related markers are presented in Table 2. Approximately 12% of patients were in the highest score category of >1000, and median score for the population was 46.6 (IQR: 0.0–344.3). Exclusion of those with a calcification score of 0 (n = 74), resulted in a median calcification score of 169.5 (IQR: 42.9–681.8).

Genotype and allele frequencies

Two hundred and seventy nine patients had DNA available, and all samples were successfully genotyped for rs2229523 and rs4373339 SNPs, but for rs10944128 only 236 samples were genotyped due to DNA depletion. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was satisfied for rs2229523 and rs4373339 SNPs, but not for rs10944128 SNP. This could be due to the difficulty in calling the genotypes accurately or the assay failure for this SNP. The minor allele frequencies were similar when compared to CEU HapMap data (0.28 versus 0.30 for rs2229523, 0.17 versus 0.13 for rs4373339, and 0.45 versus 0.39 for rs10944128 respectively).

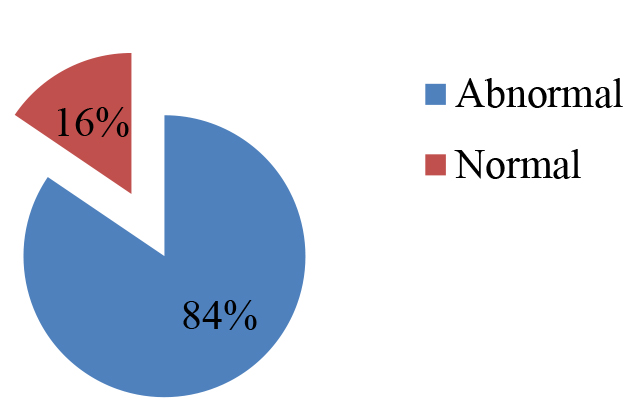

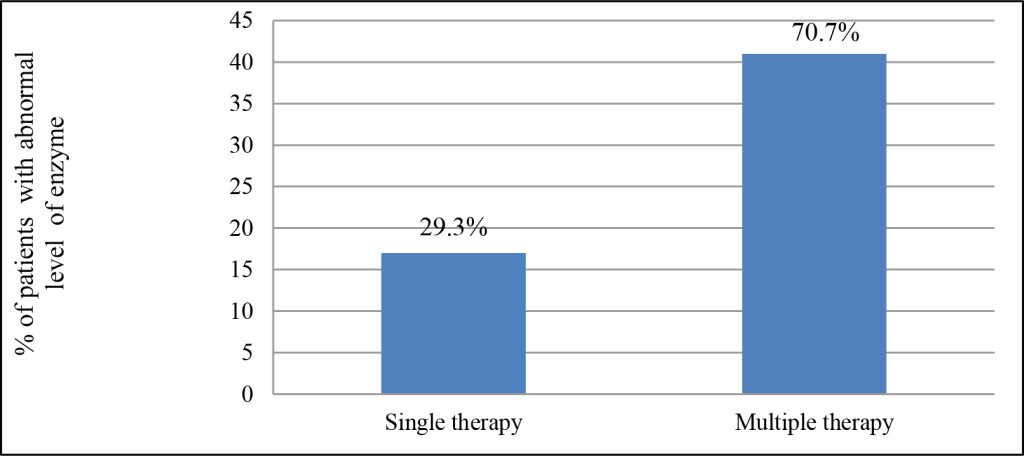

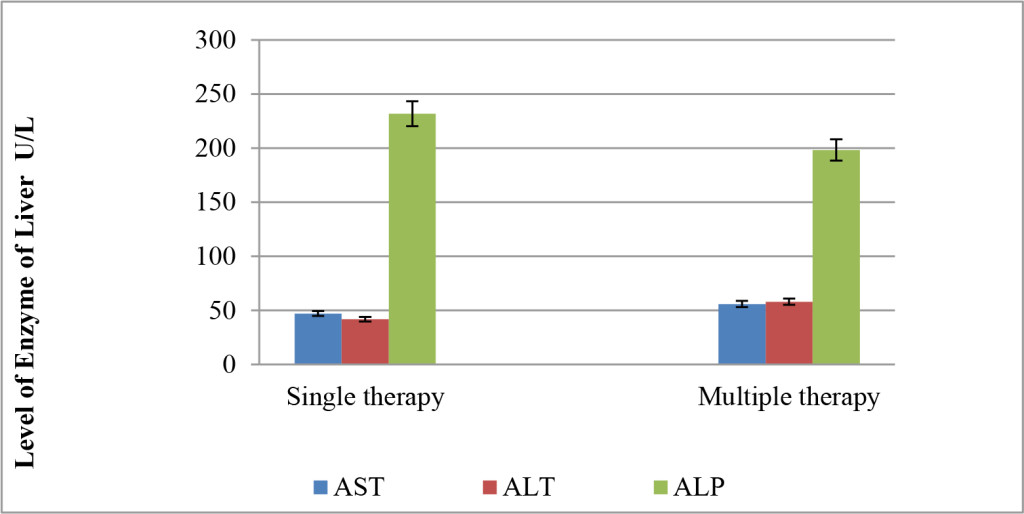

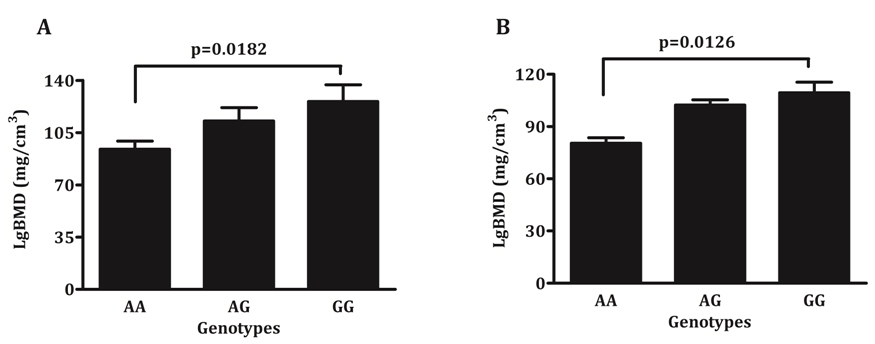

Association of NT5E SNPs with BMD and aPWV, but not with arterial calcification indices

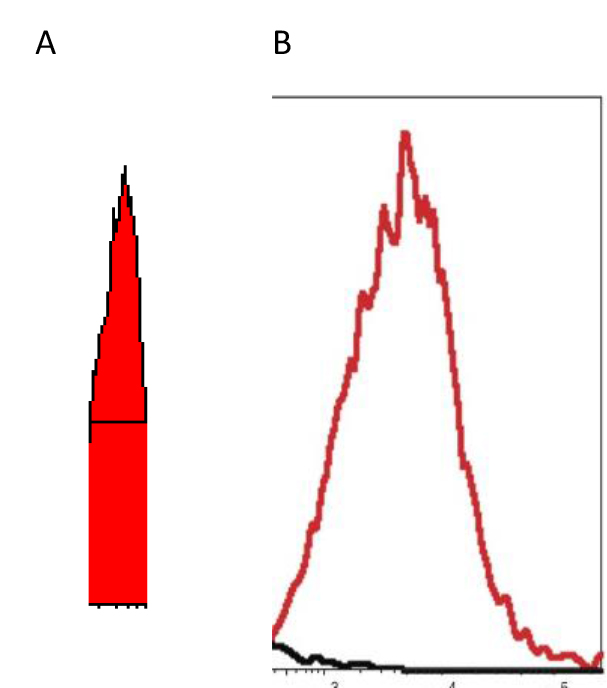

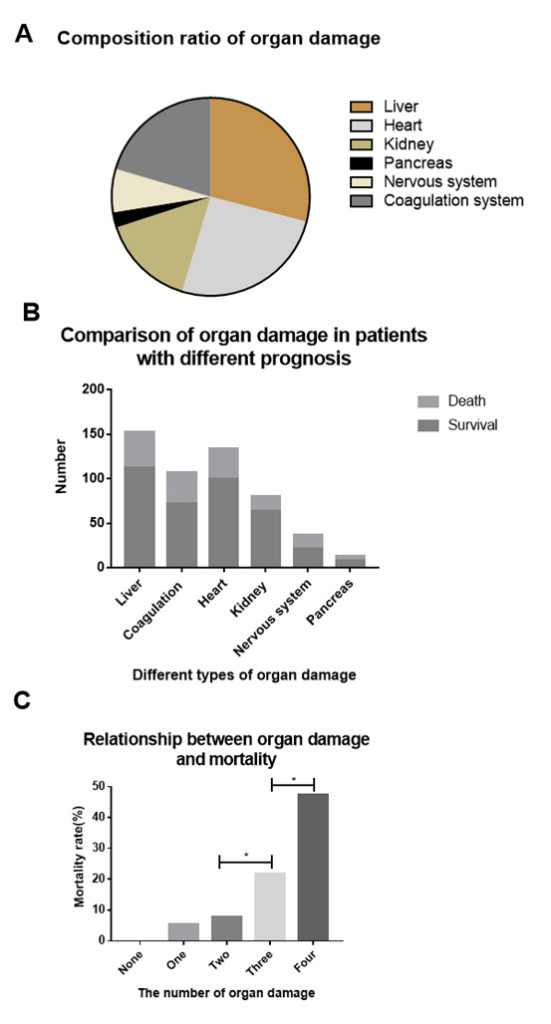

One way ANOVA demonstrated whether patient genotypes differed for BMD and aPWV (Table 3), whilst Welch’s t-test examined differences in the phenotype between the two homozygous allele carriers (Figure 2). Only rs2229523 SNP, showed a significant association and an allele dose trend with BMD. Patients with AA genotype demonstrated significantly lower BMD values than patients with GG genotypes (93.9 versus 125.7 mg/cm3, p = 0.0182) at baseline screening (Figure 2). A similar trend was also noted in patients screened after 49 months (80.4 versus 109.4 mg/cm3, p = 0.0126). In regression models adjusted for age, gender, mean arterial pressure and eGFR, rs2229523 AA genotype was also associated with a lower BMD. As seen in Table 4, the AA genotype remained significantly and independently associated with BMD in patients screened at baseline and during follow-up. These findings held true when data were analysed excluding non-Europeans and patients on CVD drugs.

Figure 2. Average bone mineral density according to rs2229523 genotypes, A) Baseline and B) Follow-up.

Table 3. Genotype differences in BMD and aPWV at baseline and follow-up.

|

|

BMD (mg/cm3)* |

aPWV (m/s)* |

||

|

|

Baseline Mean ± SD (n) |

Follow-up Mean ± SD (n) |

Baseline Mean ± SD (n) |

Follow-up Mean ± SD (n) |

|

rs2229523 A>G |

||||

|

AA |

93.9 ± 1.7 (24) |

80.4 ± 1.6 (19) |

7.84 ± 1.3 (21) |

7.19 ± 1.5 (11) |

|

AG |

112.7 ± 1.4 (76) |

103.4 ± 1.5 (50) |

8.69 ± 1.4 (70) |

7.67 ± 1.7 (26) |

|

GG |

125.7 ± 1.5 (118) |

109.4 ± 1.5 (77) |

8.63 ± 1.4 (109) |

7.28 ± 1.5 (42) |

|

**p = |

0.0182 |

0.0126 |

0.350 |

0.901 |

|

rs10944128 A>G |

||||

|

AA |

114.7 ± 1.5 (69) |

99.9 ± 1.6 (45) |

8.64 ± 1.4 (58) |

6.94 ± 1.5 (23) |

|

AC |

123.7 ± 1.4 (50) |

102.0 ± 1.5 (31) |

9.01 ± 1.4 (45) |

7.25 ± 1.5 (22) |

|

CC |

114.1 ± 1.6 (67) |

104.5 ± 1.5 (45) |

8.54 ± 1.4 (61) |

8.14 ± 1.6 (24) |

|

p = |

0.462 |

0.880 |

0.708 |

0.464 |

|

rs4373339 C>T |

||||

|

CC |

116.3 ± 1.5 (150) |

99.0 ± 1.5 (96) |

8.69 ± 1.4 (137) |

7.38 ± 1.6 (52) |

|

CT |

121.3 ± 1.4 (9) |

112.4 ± 1.6 (7) |

7.92 ± 1.5 (9) |

6.33 ± 1.3 (4) |

|

TT |

117.9 ± 1.5 (57) |

110.3 ± 1.6 (42) |

8.33 ± 1.4 (54) |

7.60 ± 1.5 (23) |

|

p = |

0.921 |

0.384 |

0.628 |

0.564 |

* Geometric means and SD

** Welch’s t-test comparing two homozygous allele carriers.

Table 4. Stepwise regression results showing an independent association of rs2229523 SNP with log transformed BMD.

|

Dependent variable: LgBMD |

Beta value |

t-value |

Significance level (P = ) |

R 2 Change |

|

Baseline model |

||||

|

Age |

–0.450 |

–7.444 |

<0.001 |

0.218 |

|

rs2229523 SNP |

–0.163 |

–2.699 |

0.0075 |

0.025 |

|

Gender |

0.121 |

1.991 |

0.048 |

0.014 |

|

|

R square = 0.257; F = 23.608; P<0.001 |

|||

|

Follow-up model |

||||

|

Age |

–0.548 |

–7.984 |

<0.001 |

0.312 |

|

rs2229523 SNP |

-0.167 |

–2.432 |

0.0163 |

0.028 |

|

|

R square = 0.340; F = 36.268; P<0.001 |

|||

Excluded variables in baseline model were: mean arterial pressure, eGFR.

Excluded variables in follow-up model were: gender, mean arterial pressure, eGFR.

Genotype differences were found with aPWV for rs2229523 SNP (Table 3); aPWV is reduced in patients carrying the rs2229523 AA genotype compared with the GG genotype. This non-significant trend was observed at both visits (baseline: 7.84 versus 8.63 m/s, p=0.350; follow-up: 7.19 versus 7.28 m/s, p=0.901).

No association was found between the SNPs and the arterial calcification indices (CAC, AC) in this CKD group.

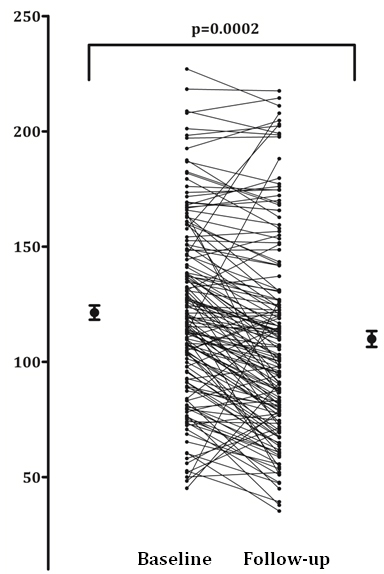

Changes in BMD and aPWV at 49 months

Follow up data was available for just over 50% of the participants who returned for a scan. After a mean of 49 months, the vascular bone axis marker (BMD) reduced significantly (113.9 versus 103 mg/cm3;

p = 0.0002; Figure 3), whilst the aPWV reduced to a much lesser extent (8.55 versus 7.89 m/s; p = 0.057, data not shown).

Figure 3. Average bone mineral density values at baseline and follow up.

Associations between age and calcification phenotypes

As expected, age associated significantly with BMD, PWV, CAC and AC (r = –0.46, r = 0.49, 0.60, 0.51; p = 0.001 respectively, data not shown), and when this relationship was explored further by examining just CAC in men and women according to decades of age, the average CAC score increased with each decade in both men and women (Table 5); the lowest mean values were observed in the younger patients and highest values in older patients.

Table 5. Coronary artery calcification score in CKD patients by age and gender.

|

Age Groups (n) |

Men (Mean ± SEM) |

Women (Mean ± SEM) |

|

<40 years (31) |

4.5±3.0 |

0.13±0.1 |

|

41–50 years (34) |

89.3±59.3 |

77.5±51.4 |

|

51–60 years (47) |

425±194 |

54.6±18.7 |

|

61–70 years (53) |

762±196 |

75.8±26.3 |

|

>71 years (74) |

875±138 |

213±130 |

SEM = standard error of mean.

BMD also associated inversely with AC (r = –0.30, p = 0.001, data not shown) and aPWV (r = –0.16, p = 0.032, data not shown), which suggests that low BMD and increasing arterial calcification have common features [28]. The positive correlation between calcification scores and stiffness (aortic: 0.40, p = 0.001; coronary artery: 0.22, p = 0.015, data not shown), demonstrates the associated changes in the vessel wall of CKD patients [29].

Discussion

This study sought to determine the influence of common SNPs in the NT5E gene on calcification phenotypes (BMD, aPWV) in pre-dialysis CKD patients. For the first time, we identified a significant independent association between a single NT5E gene polymorphism (rs2229523 SNP) and BMD, a marker of the vascular-bone axis. Independent of risk factors like age, gender, mean arterial pressure and eGFR, we found that rs2229523 AA genotype associated with lower BMD. This relationship was found in patients screened both at baseline and after 49 months of follow up. The rs2229523 AA genotype also showed reduced aortic stiffness (aPWV). However, no independent SNP associations were observed with aPWV or with coronary artery or aortic calcification (CAC, AC).

Significant association between rs2229523 SNP and BMD

The finding that an NT5E rs2229523 SNP is associated with BMD suggests a role for CD73 in bone formation. This is supported by the finding of osteopenia, reduced osteoblastic markers and impaired osteroblastic differentiation in CD73 knockout mice [30]. In the same study, induced overexpression of CD73 was associated with increased osteoblastic differentiation, and increased expression of osteocalcin and bone sialoprotein, the effects of which were reversed by an A2B receptor antagonist [30]. These findings suggest that the effects of CD73 on bone metabolism are mediated by CD73-derived adenosine signalling. The role of CD73 in bone metabolism is further supported by another study where CD73 expression is regulated by the Wnt-b-catenin signalling pathway, a known critical pathway in both bone metabolism and osteogenic vascular calcification [31]. In addition, the inducible HIF-1 alpha transcription factor, which regulates many factors involved in bone regeneration and development, also regulates CD73 expression [32].

The regression analysis findings suggest that rs2229523 AA genotype predicts a lower BMD after adjustments of confounding factors like age, gender, mean arterial pressure and eGFR. The exact mechanisms behind the the lower BMD and reduced aPWV observed in patients with AA genotype are currently unclear and outside the scope of this study, but merits further investigation. The SNP in question is a non-synonymous coding SNP which results in a change in amino-acid from threonine to alanine at position 376. It is believed that this results in an alternative shorter isoform of the protein. The clinical implication of this isoform change is not known, but this is the first study linking this SNP to BMD. As rs2229523 is a tagSNP, the observed relationship may relate to this amino-acid change or may, alternatively, relate to another SNP within the same LD block.

None of the SNPs in this study, associated with BMD or bone mineral content in published genome wide association studies (GWAS) [33,34], and this could be explained by the populations or phenotypes studied or the genechips used. But the present finding of an association between BMD and rs2229523 SNP, and its role in the regulation of vascular calcification is not surprising given the known reciprocal and parallel relationship between arterial and skeletal mineralisation. A significant inverse assocation between vascular calcification and BMD has been demonstrated in non-CKD populations [35] as well as in dialysis [2] and pre-dialysis CKD populations [29], a finding replicated in our study. This relationship appears to be particularly strong in CKD, which provides an ideal milieu for both arterial calcification and osteopenia due to synergism between hyperphosphataemia, hyperparathyroidism, and the treatments associated with CKD [29,36]. Pre-clinical studies showed that inflammatory markers such as lipids and cytokines appear to accelerate vascular calcification while they promote bone loss [38]. Similarly, osteogenic agents, like PTH and BMP-7, promote skeletal mineralisation but suppress this process in arteries [36]. The mechanism linking arterial calcification to bone loss is unknown and the temporal nature of events has not been established. One theory is that both share a common aetiology and use common factors [38]. CD73 provides a link between the two conditions; its osteogenic role in bone in parallel with its anti-inflammatory role in the vasculature would result in bone loss and calcification in the event of deficiency, consistent with the reciprocal relationship observed between the two conditions.

Significant associations found between arterial calcification phenotypes, but not between calcification phenotypes and NT5E SNPs

We replicated previous positive associatons between age, arterial calcification (aortic and coronary artery) and arterial stiffness (aPWV) [29, 37, 38]. However, we did not find these phenotypes to associate with any of the NT5E SNPs. There are several possible explanations for the lack of associations between the SNPs and arterial calcification. First, the inability to measure medial calcification independent of intimal calcification may have prevented detection of an association. Histopathological evidence from specimens derived from arterial calcification due to deficiency of CD73 (ACDC) patients suggest, that the calcification process resulting from CD73 deficiency is confined to the arterial media [20]; therefore, medial calcification is the relevant phenotype. As current instruments do not have the capability of distinguishing between medial and intimal calcification [39], the measured phenotype in this study was actually an aggregate of both intimal and medial calcification, diluting the relevant phenotype.

Second, the lack of an assocation might be due to measurement of central artery rather than peripheral artery calcification. It is important to note that the ACDC phentotype is characterised by heavy calcification specifically in the large lower limb peripheral arteries, with relative sparing of the coronary and aortic arteries [20,13]. Therefore, a CD73-related protein family member, such as CD39, or its related isoforms, may compensate for CD73 deficiency in other vascular beds [40]. Given this, it is not surprising that NT5E SNPs were not associated with coronary or aortic calcfication in this study.

Third, it is possible that the relationship between NT5E mutations and calcification observed in ACDC [12] is non-causal. The proposed mechanism linking CD73 deficiency to arterial calcification is based upon in vitro experiments in skin fibroblasts [12], which may differ signficantly from vascular endothelial cells. Furthermore, the vascular calcification phenotype has not been recapitulated in in vivo mice studies, where CD73 deletion has been found to be associated with multi-organ fulminant vascular leakage rather than calcification [41].

Fourth, it may be that NT5E genetic variation does cause calcification but it does not do so by affecting the essential pyrophosphate pathway, instead it affects non-essential pathways. For example, the calcification phenotype produced by NT5E mutations is more likely to be explained by the anti-inflammatory role of CD73 rather than its indirect effects on pyrophosphate hydrolysis [42]. A polymorphism in an anti-inflammatory pathway is less likely to be of clinical significance due to the upregulation of alternative anti-inflammatory pathways in CKD.

Lastly, 27% of patients had an arterial calcification score of 0, which resulted in reduced power, and the SNPs investigated do not represent the whole gene, so it is possible that relevant variations reside in the other unexplored regions. Therefore, the relationship between NT5E genetic variation and arterial calcificaiton merits further investigation and replication in other independent CKD population.

Conclusion

For the first time, we have shown that rs2229523, a non-synonymous coding SNP resulting in an amino-acid change (threonine to alanine), and AA genotype is associated with lower BMD in patients with CKD seen before and after 49 months . Further work is necessary to evaluate the identified associations in other CKD cohorts. Functional studies are also required to elucidate the biological mechanisms underlying the observed relationship between NT5E rs2229523 SNP and BMD. The role of adenosine, adenosine regulators and adenosine receptor agonists as potential therapeutic agents in relation to vascular calcification and osteopenia also warrants extensive further exploration. Overall, this study offers new insights into the bone-vascular axis in chronic kidney disease, identifying a novel role for CD73 of potential clinical importance.

Acknowledgements We thank all the individuals who participated in the LACKABO study. The LACKABO study participants were recruited by a grant from the Kidney Research (Grant No. VC1/2002), and the genotyping costs were supported by the Addenbrooke’s Charitable Trust (Ref No. 23/08(B) (F). We also thank Dr Michael Rubens for performing scans, Dr Sharon Barrett and Dr Melanie Chan with pulse wave analysis measurements.

Conflict of interest The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Blacher J, Guerin AP, Pannier B, Marchais SJ, London GM. (2001) Arterial Calcifications, Arterial Stiffness, and Cardiovascular Risk in End-Stage Renal Disease. Hypertension. 38(4): 938–42.

- Aoki A, Kojima F, Uchida K, Tanaka Y, Nitta K. (2009) Associations between vascular calcification, arterial stiffness and bone mineral density in chronic hemodialysis patients. Geriatrics & Gerontology International. 9(3): 246–52.

- Blacher J, Guerin AP, Pannier B, Marchais SJ, Safar ME, London GM. (1999) Impact of aortic stiffness on survival in end-stage renal disease. Circulation. 99(18): 2434–9.

- Shoji T, Emoto M, Shinohara K, Kakiya R, Tsujimoto Y, Kishimoto H, et al. (2001) Diabetes mellitus, aortic stiffness, and cardiovascular mortality in end-stage renal disease. Journal of American Society of Nephrology. 12(10): 2117–24.

- Goodman WG, London G, Amann K, Block Ga, Giachelli C, Hruska Ka, et al. (2004) Vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 43(3): 572–9.

- Román-García P, Rodríguez-García M, Cabezas-Rodríguez I, López-Ongil S, Díaz-López B, Cannata-Andía JB. (2011) Vascular calcification in patients with chronic kidney disease: types, clinical impact and pathogenesis. Medical Principles and Practice. 20(3): 203–12.

- Schinke T, Karsenty G. (2000) Vascular calcification–a passive process in need of inhibitors. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 15(9): 1272–4.

- Schinke T, McKee MD, Kiviranta R, Karsenty G. (1998) Molecular determinants of arterial calcification. Annals of Medicine. 30(6): 538–41.

- Schoppet M, Shanahan CM. (2008) Role for alkaline phosphatase as an inducer of vascular calcification in renal failure? Kidney International. 73(9): 989–91.

- Meyer JL. (1984) Can biological calcification occur in the presence of pyrophosphate? Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 231(1): 1–8.

- Rutsch F, Vaingankar S, Johnson K, Goldfine I, Maddux B, Schauerte P, et al. (2001) PC-1 nucleoside triphosphate pyrophosphohydrolase deficiency in idiopathic infantile arterial calcification. American Journal of Pathology. 158(2): 543–54.

- Eller P, Hochegger K, Feuchtner GM, Zitt E, Tancevski I, Ritsch A, et al. (2008) Impact of ENPP1 genotype on arterial calcification in patients with end-stage renal failure. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 23(1): 321–7.

- St Hilaire C, Ziegler SG, Markello TC, Brusco A, Groden C, Gill F, et al. (2011) NT5E mutations and arterial calcifications. The New England Journal of Medicine. 364(5): 432–42.

- Sharp J. (1954) Heredo-familial vascular and articular calcification. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 13(1): 15–27.

- Mori H, Yamaguchi K, Fukushima H, Oribe Y, Kato N, Wakamatsu T, et al. (1992) Extensive arterial calcification of unknown etiology in a 29-year-old male. Heart Vessels. 7(4): 211–4.

- Zhang Z, He JW, Fu WZ, Zhang CQ, Zhang ZL. (2015) Calcification of joints and arteries: second report with novel NT5E mutations and expansion of the phenotype. Journal of Human Genetics. 60(10): 561–4.

- Yoshioka K, Kuroda S, Takahashi K, Sasano T, Furukawa T, Matsumura A. (2017) Calcification of joints and arteries with novel NT5E mutations with involvement of upper extremity arteries. Vascular Medicine. 22(6): 541–3.

- O’Neill WC, Sigrist MK, McIntyre CW. (2010) Plasma pyrophosphate and vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 25(1): 187–91.

- Colgan SP, Eltzschig HK, Eckle T, Thompson LF. (2006) Physiological roles for ecto-5’-nucleotidase (CD73). Purinergic Signal. 2(2): 351–60.

- Markello TC, Pak LK, St C, Dorward H, Ziegler SG, Chen MY, et al. (2011) Vascular pathology of medial arterial calcifications in NT5E deficiency: implications for the role of adenosine in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Molecular Genetics & Metabolism. 103(1): 44–50.

- Hasegawa T, Bouis D, Liao H, Visovatti SH, Pinsky DJ. (2008) Ecto-5’ nucleotidase (CD73)-mediated adenosine generation and signaling in murine cardiac allograft vasculopathy. Circulation Research. 103(12): 1410–21.

- Rutsch F, Nitschke Y, Terkeltaub R. (2011) Genetics in arterial calcification: pieces of a puzzle and cogs in a wheel. Circulation Research. 109(5): 578–92.

- Caplin B, Nitsch D, Gill H, Hoefield R, Blackwell S, MacKenzie D, et al. (2010) Circulating methylarginine levels and the decline in renal function in patients with chronic kidney disease are modulated by DDAH1 polymorphisms. Kidney International. 77(5): 459–67.

- Shaw LJ, Raggi P, Schisterman E, Berman DS, Callister TQ. (2003) Prognostic value of cardiac risk factors and coronary artery calcium screening for all-cause mortality. Radiology. 228(3): 826–33.

- Dendukuri N, Chiu K, Brophy JM. (2007) Validity of electron beam computed tomography for coronary artery disease: asystematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Medicine. 5: 35.

- Wilkinson IB, Fuchs SA, Jansen IM, Spratt JC, Murray GD, Cockcroft JR, et al. (1998) Reproducibility of pulse wave velocity and augmentation index measured by pulse wave analysis. Journal of Hypertension. 16(12 Pt 2): 2079–84.

- Hallan S, Asberg A, Lindberg M, Johnsen H. (2004) Validation of the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula for estimating GFR with special emphasis on calibration of the serum creatinine assay. American Journal of Kidney Disease. 44(1): 84–93.

- Kooman JP, Kotanko P, Schols AM, Shiels PG, Stenvinkel P. (2014) Chronic kidney disease and premature ageing. Nature Reviews Nephrology. 10(12): 732–42.

- Toussaint ND, Lau KK, Strauss BJ, Polkinghorne KR, Kerr PG. (2008) Associations between vascular calcification, arterial stiffness and bone mineral density in chronic kidney disease. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 23(2): 586–93.

- Takedachi M, Oohara H, Smith BJ, Iyama M, Kobashi M, Maeda K, et al. (2012) CD73-generated adenosine promotes osteoblast differentiation. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 227(6): 2622–31.

- Spychala J, Kitajewski J. (2004) Wnt and beta-catenin signaling target the expression of ecto-5’-nucleotidase and increase extracellular adenosine generation. Experimental Cell Research. 296(2): 99–108.

- Synnestvedt K, Furuta GT, Comerford KM, Louis N, Karhausen J, Eltzschig HK, et al. (2002) Ecto-5’-nucleotidase (CD73) regulation by hypoxia-inducible factor-1 mediates permeability changes in intestinal epithelia. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 110(7): 993–1002.

- Rivadeneira F, Styrkársdottir U, Estrada K, Halldórsson BV, Hsu YH, Richards JB, et al. (2009) Twenty bone-mineral-density loci identified by large-scale meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Nature Genetics. 41(11): 1199–206.

- Styrkarsdottir U, Halldorsson BV, Gretarsdottir S, Gudbjartsson DF, Walters GB, Ingvarsson T, et al. (2009) New sequence variants associated with bone mineral density. Nature Genetics. 41(1): 15–7.

- Lin T, Liu JC, Chang LY, Shen CW. (2011) Association between coronary artery calcification using low-dose MDCT coronary angiography and bone mineral density in middle-aged men and women. Osteoporosis International. 22(2): 627–34.

- Demer LL, Tintut Y. (2008) Vascular calcification: pathobiology of a multifaceted disease. Circulation. 117(22): 2938–48.

- Raggi P, Bellasi A, Ferramosca E, Islam T, Muntner P, Block GA. (2007) Association of pulse wave velocity with vascular and valvular calcification in hemodialysis patients. Kidney International. 71(8): 802–7.

- Temmar M, Liabeuf S, Renard C, Czernichow S, Esper NE, Shahapuni I, et al. (2010) Pulse wave velocity and vascular calcification at different stages of chronic kidney disease. Journal of Hypertension. 28(1): 163–9.

- Goodman WG, London G. (2004) Vascular Calcification in Chronic Kidney Disease. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 43(3): 572–9.

- Rutsch F, Nitschke Y, Terkeltaub R. (2011) Genetics in arterial calcification: Pieces of a puzzle and cogs in a wheel. Circulation Research. 109(5): 578–92.

- Thompson LF, Eltzschig HK, Ibla JC, Van De Wiele CJ, Resta R, Morote-Garcia JC, et al. (2004) Crucial role for ecto-5’-nucleotidase (CD73) in vascular leakage during hypoxia. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 200(11): 1395–405.

- Schrader J. (2011) NT5E mutations and arterial calcifications. The New England Journal of Medicine. 364(16): 1578–9.