DOI: 10.31038/EDMJ.2017125

Abstract

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a common and debilitating condition in the United States affecting an estimated 7.7 million adults annually. Women are twice as likely to be diagnosed as men. Individuals who have been exposed to military combat, victims of natural disasters, concentration camp survivors, and victims of violent crime are at particular risk for PTSD, but not all victims of trauma will suffer from PTSD. Hallmarks of the disorder include intrusive memories, flashbacks, and nightmares which result in compensatory behaviors to avoid triggering stimuli, as well as emotional blunting. Management of PTSD typically involves medication and psychotherapy, especially cognitive-behavioral therapy, but complementary and alternative medicine, or mind-body approaches that occur outside of traditional medical venues, are also being utilized.

The proposed mechanisms for PTSD are multifaceted. Dysregulation of neuroendocrine pathways and feedback loops have been commonly implicated in the pathogenesis of PTSD, but a definitive unifying framework for the etiology of this disorder has not yet been identified. Dysregulation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis is commonly invoked in the pathogenesis or pathophysiologic response to PTSD, but abnormalities of adrenal catecholamines, neuroendocrine transmitters in the brain, the pituitary-thyroid axis, and sex hormone regulation have also been identified.

The goal of this report is to review the literature to-date that examines the potential role of hormones in PTSD, and to explore limitations to methodologies and testing that might account for variation in the literature.

Keywords

PTSD, hormones, neuroendocrine, HPA

Introduction

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) was first recognized as a distinct diagnostic entity in 1980 by the American Psychiatric Association when it was included in the DSM-III. Despite a 36-year history, however, it remains underdiagnosed and misunderstood. PTSD’s emergence as a distinct diagnosis filled an important void in psychiatric theory and practice by acknowledging that an external trauma may cause symptoms, as opposed to the view that such symptoms are attributable to an individual’s weakness (e.g., a traumatic neurosis). Exposure to any traumatic event can induce PTSD, although it is difficult to predict who will be affected and who will not. Those diagnosed with PTSD are predictably at risk for a reduced quality of life, substance abuse, suicide, reduced productivity, domestic violence, impaired relationships, and other risky and unhealthy behaviors [1]. The U.S. Department of Defense has invested significant resources into the research, development, and implementation of PTSD programs. Consequently, the majority of studies to date have been performed on males with active combat experience. Unfortunately, only 23 to 40 percent of veterans who screen positive for PTSD seek and receive medical care [2]. Pharmacological and cognitive therapy interventions for those who suffer from PTSD have been shown to have some positive effects, but many veterans do not seek medical assistance for their symptoms and consequently self-medicate. When they do seek treatment, patients may instead turn to complementary and alternative treatments [3].

The intent of this review is to examine the neuroendocrine dysregulation associated with PTSD, consider potential treatment avenues, and explore potential causes for the apparently conflicting data that have appeared over the decades.

For the purposes of this review, a query of the PubMed database was performed in the fall of 2016 that cross-referenced “Post Traumatic Stress Disorder” or “PTSD” with the following terms: pathophysiology, endocrine, hormones, cortisol, catecholamines, pituitary, testosterone, symptoms, human studies, and military literature. These terms were expected to link the endocrine phenomena with psychiatric topics of interest. A total of 58 studies were identified and are reviewed here.

Part 1: The Role of Hormones in the Pathogenesis of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

The Hypothalamo-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) System

Stimulation of the HPA axis begins in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus. Under normal physiology the PVN receives crosstalk from the suprachiasmatic nucleus to modulate diurnal variations [4]. However, in response to stressors, the PVN releases corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) and arginine vasopressin. In turn, CRH acts on the anterior pituitary gland to stimulate secretion of ACTH, which then acts on the adrenal cortex to stimulate secretion of cortisol. Hormones at each step of this cascade feedback on preceding levels to attenuate additional secretion.

The most relevant data gathered regarding the pathogenesis of PTSD pertain to the HPA axis and support disturbed feedback inhibition and blunted cortisol responses to stress. Studies that have evaluated ACTH levels in patients with PTSD have demonstrated normal concentrations, or levels that are comparable to control groups, but Bremner et al. have documented higher cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentrations of CRH in Vietnam veterans with PTSD as compared to healthy controls [5]. They surmise that higher concentrations of CRH in the CSF of PTSD patients reflect alterations in stress-related neurotransmitter systems and that higher CSF CRH concentrations may play a role in disturbances of arousal in such patients. Savic et al. examined 400 participants divided into four groups: 133 individuals with current PTSD, 66 subjects with a history of PTSD, 102 trauma controls without PTSD, and 99 healthy controls [6]. ACTH concentrations were assessed after overnight dexamethasone suppression, and no significant differences were observed between groups. Similarly, a pilot study by Muhtz et al. examined 14 patients with chronic PTSD and 14 healthy controls without PTSD [7]. They combined a low dose (0.5 mg) of oral dexamethasone at 23:00 followed by 100 mcg IV CRH 16 hours later. ACTH was measured at -15, 0 and every 15 minutes thereafter for a total of 135 minutes. No significant differences were observed in ACTH levels between the two study groups, but they did find that individuals with a history of early childhood trauma had higher post-suppression ACTH levels than those without childhood trauma. They suggest that the type of trauma may play a role in the multifactorial metabolic derangements of PTSD. In general, these data underscore that no differences exist in ACTH levels among groups, but a question remains about whether CRH is elevated and whether this affects the dynamics of stress arousal in patients.

Conversely, De Kloet et al. evaluated 23 veterans with PTSD, 22 trauma patients without PTSD, and 24 healthy controls in the afternoon following overnight administration of 0.5 mg dexamethasone [8]. They found that there were marginally higher ACTH concentrations among the PTSD patients at 16:00 on a day when dexamethasone was not given (p =0.06) and at 20:00 on a day following administration of dexamethasone (p=0.04), but there was not a significant difference between the study groups in the degree of post-dexamethasone suppression. As shown in Figure 1, PTSD patients also demonstrate a significantly blunted salivary cortisol (a surrogate for free cortisol) upon awakening as compared to healthy control subjects (but not trauma control subjects). Kellner et al. also found no difference when comparing ACTH concentrations between 17 individuals with PTSD and 17 healthy controls without PTSD [9]. These data indicate that no reproducible, clinically significant differences exist between the ACTH levels of PTSD patients as compared with unaffected control subjects.

![Figure 1. Salivary cortisol response to awakening among 23 Dutch Military Veterans with PTSD (solid squares) as compared to 24 Healthy Control subjects (solid circles). Adapted from de Kloet et al. [7].](http://researchopenworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/EDMJ-2017-104_Fig_1.png)

Figure 1. Salivary cortisol response to awakening among 23 Dutch Military Veterans with PTSD (solid squares) as compared to 24 Healthy Control subjects (solid circles). Adapted from de Kloet et al. [7].

Other investigators, however, have been able to demonstrate some dysregulation of the pituitary-adrenal axis through careful assessment. In attempt to elucidate the mechanism of an observed paradoxical increase in CRH in the setting of reduced baseline cortisol concentrations among patients with PTSD, Yehuda et al. performed an elaborate study among 19 male and female subjects with PTSD as compared to 19 male and female controls [10]. They posited two potential mechanisms for this finding, including enhanced negative feedback of cortisol on the hypothalamus versus reduced adrenal responsiveness to ACTH in PTSD. They tried to discriminate between these two possibilities by measuring ACTH and cortisol at baseline and in response to overnight dexamethasone suppression. They demonstrated that the ACTH-to-cortisol ratio did not differ between groups before or after dynamic testing, but that the subjects with PTSD showed greater suppression of ACTH and cortisol in response to dexamethasone than did the controls. These results, summarized in Figure 2, suggest that enhanced cortisol negative feedback inhibition of ACTH secretion occurs in patients with PTSD, as opposed to reduced adrenal output of cortisol in response to ACTH stimulation [10]. These findings may explain why no significant differences in ACTH levels can be appreciated between PTSD and control groups.

![Figure 2. Percent suppression of ACTH from baseline by 0.5 mg of dexamethasone overnight among patients with PTSD versus patients without PTSD. Adapted from Yehuda et al. [11].](http://researchopenworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/EDMJ-2017-104_Fig_2.png)

Figure 2. Percent suppression of ACTH from baseline by 0.5 mg of dexamethasone overnight among patients with PTSD versus patients without PTSD. Adapted from Yehuda et al. [11].

Contrary to the studies above, Ströhle et al. studied 8 adults with PTSD and 8 healthy age- and sex-matched controls without PTSD in a similar experiment. They found that patients with PTSD had a decreased ACTH response to CRH after pretreatment with dexamethasone, suggesting a “hyporeactive” stress hormone system [11]. Some of Yehuda’s earlier work had raised the possibility that these studies may not have measured ACTH accurately, asserting that ACTH levels must be determined through repeated sampling over a short period of time. Using the gold-standard metyrapone test in individuals with PTSD, there was a significant increase in ACTH and in the cortisol precursor, 11-deoxycortisol, in subjects with PTSD as opposed to those without it. This suggests that the HypothalamoPituitary–Adrenal (HPA) axis is releasing higher concentrations of ACTH in individuals with PTSD in comparison to individuals without PTSD [12]. These conclusions are something of an outlier among the greater PTSD literature pertaining to ACTH, and they should spur reassessment of the best methodologies to accurately measure hormonal dynamics in PTSD as research moves forward.

A majority of the research exploring cortisol levels in patients with PTSD demonstrates lower ambient cortisol levels as compared to healthy controls and other psychiatric groups. Yehuda et al. showed this when comparing Holocaust survivors with PTSD to Holocaust survivors without PTSD and found that chronic PTSD was associated with reduced serum cortisol concentrations [13]. They suggest that the continuing high stress levels associated with PTSD may be exhausting the HPA axis and resulting in decreased cortisol levels. Similarly, Boscarino compared service veterans who were deployed in Vietnam with Vietnam-era veterans who were not in the theater of combat [14]. He controlled for the level of combat, as well as for multiple other potentially confounding variables, and his results indicate that those who were deployed in the combat theater had a higher prevalence of PTSD, and that theater veterans with current PTSD had lower cortisol concentrations than those who did not have PTSD. These findings suggest the importance of considering combat exposure in addition to the DSM diagnosis criteria when studying PTSD and cortisol concentrations. Overall, these two studies complement the observations referenced in the aforementioned studies pertaining to ACTH by demonstrating that cortisol levels are lower than expected in populations with prolonged hyperarousal states.

Another study, by Goenjian et al., compared adolescents from two cities in Armenia that were near the occurrence of a 6.9 magnitude earthquake. Specifically, the city of Spitak was at the epicenter of the earthquake and the city of Yerevan was at the periphery. The adolescents were old enough at the time of the earthquake to remember it. According to the DSM-IV, PTSD symptoms are grouped into different categories. Category B includes persistent re-experiencing of the traumatic event. Category C includes persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma and numbing of general responsiveness. Category D includes persistent symptoms of increased arousal. PTSD symptom scores were significantly higher among adolescents from Spitak, and they found a negative correlation between PTSD category C and D symptoms and baseline cortisol levels. Category B symptom scores narrowly missed statistical significance (p=0.06). There were no independent effects of sex or any other clinical or hormonal variables on these findings. The study supports the proposition that individuals with PTSD may have enhanced negative feedback inhibition of cortisol, resulting in lower cortisol levels [15]. When compared to the findings by Boscarino, these data also suggest that there is no significance to the type of trauma, in this case natural disaster as opposed to combat, that produces this blunted cortisol response.

Also addressing the nature and severity of trauma, Olff et al. explored HPA axis changes among civilians with chronic PTSD due to trauma such as sexual abuse, loss of a loved one, disaster, or motor vehicle accident. The control group consisted of healthy volunteers without PTSD. The results showed that plasma cortisol levels were significantly reduced in the PTSD group compared to the control group. In addition, the average cortisol levels were lower after controlling for potentially confounding variables, such as sex, age, body mass index (BMI), and smoking. A negative linear relationship between cortisol levels and the severity of PTSD symptoms was also found. The authors suggest that these findings raise the question as to whether some of the discrepant findings related to serum cortisol and PTSD in the medical literature may be attributable to the differing severity of trauma in different studies [16]. In the larger picture, this study underscores that the blunting of cortisol among PTSD patients may occur with many different types of trauma and suggests a relationship between the severity of trauma and the degree of cortisol blunting.

In attempt to elucidate the potential role of reduced cortisol binding globulin (CBG) concentrations as a mechanism for decreased cortisol concentrations in PTSD, Kanter et al. studied thirteen Vietnam veterans and found that while plasma cortisol levels were significantly lower among PTSD patients than among control subjects without PTSD, they also found that CBG levels were increased in the PTSD patients compared to controls [17]. Wahbeh et al. evaluated salivary cortisol levels (as a reflection of free cortisol) in PTSD and found that the levels were lower among 51 combat veterans with PTSD as compared with 20 veterans without PTSD [18]. He further found that adding age, BMI, smoking, medications affecting cortisol, awakening time, sleep duration, season, depression, perceived stress, service area, combat exposure, and lifetime trauma as covariates to the model did not reduce the significance of the relationship between PTSD and salivary cortisol. These data contribute to the overall understanding of PTSD dynamics by eliminating the role of CBG in the blunted cortisol findings.

Not surprisingly, there are also studies that have found elevated cortisol levels in individuals with PTSD. One study, by Wang et al., described the occurrence of PTSD and plasma cortisol concentrations among 48 survivors of a coal mining disaster in China. They found that plasma cortisol levels were significantly higher in PTSD patients six months after the disaster than in survivors without PTSD, and this relationship was maintained after adjusting for age and BMI. In this study, the cortisol levels at six months were also correlated with somatic symptoms, interpersonal symptoms, depression, anxiety, and hostility scores on the PTSD Symptom Checklist 90-Revised (PCL- 90-R), a widely used 90-item self-report instrument that includes nine subscales that target various domains of psychopathology [19]. Another study from China, by Song et al., examined 34 earthquake survivors with PTSD, 30 earthquake survivors with subclinical PTSD, and 34 normal controls [20]. They found that the survivors with PTSD and those with subclinical PTSD both demonstrated significantly higher levels of serum cortisol as compared to the control group. A study that included Vietnam combat veterans with PTSD also found that they had higher cortisol concentrations compared to the control group [21]. Another study that included Croatian combat veterans with PTSD demonstrated fewer glucocorticoid receptors on the surfaces of lymphocytes among the PTSD patients compared to healthy controls. This inverse association has been identified in a number of psychiatric diagnoses and potentially explains the observation of elevated cortisol concentrations [22]. Wheeler et al. compared the cortisol production rates between 10 control subjects and with 10 individuals with chronic PTSD and a history of childhood trauma, domestic violence, or war trauma. They demonstrated no difference in cortisol production rates between the two groups using stable isotopic methods in the unprovoked state, but they did demonstrate significantly reduced urinary free cortisol levels in the chronic PTSD group [23]. These studies show that there may be cortisol dynamics related to the proximity in time to a traumatic event, and that observed elevations in cortisol are probably not related to up-regulations in cortisol production in the adrenal gland.

In attempt to evaluate the impact of time on cortisol levels, Simmons et al. examined exposure to lifetime traumatic events and changes to cortisol levels in hair samples, a relatively new and reliable method for assessment of integrated cortisol over time [24]. The sample population included 70 children who were also enrolled in a longitudinal study of brain development and who had experienced a variety of trauma as reported by parents using the LITE-PR screening measure. Three cm of hair representing approximately 3 months of growth were removed from the vertex. They discovered that hair cortisol concentrations (HCC) are positively correlated with lifetime trauma and is a potentially cost-effective and reliable biomarker of HPA dynamics among children. Of note, these findings in children are consistent across studies but are inconsistent with HCC studies in adults. The explanation for this discrepancy may be rooted in the temporal proximity of the trauma to the sampling. This study reinforces the previously mentioned studies suggestive of enhanced cortisol early after the traumatic event.

As previously introduced, salivary cortisol measurements are another recent non-invasive method to assess cortisol levels. Yoon and Weierich measured salivary cortisol and alpha-amylase in 20 women who met criteria for diagnosis of PTSD per DSM-IV to evaluate HPA and Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) reactivity to trauma reminders [25]. On two separate occasions, subjects underwent the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) to describe their traumatic event, and submitted salivary samples before, during and after the SCID. The alpha-amylase levels reflect SNS responses at each time point, whereas the salivary cortisol levels indicate HPA activity approximately 20 minutes prior to the sample collection. They found blunted cortisol activity and marked SNS activity when exposed to stressors (i.e., the description of the trauma during SCID). They conclude that the blunted cortisol is a protective mechanism when HPA is chronically activated to protect the body from long-term immunosuppression; a concept reinforced by multiple studies over time. This theory also partially explains the phenomenon of enhanced SNS activity such that under normal physiology, cortisol downregulates SNS response, while in these patients, the blunted cortisol fails to mediate this effect. This study is important because it reinforces and attempts to explain ongoing observations in the PTSD-HPA literature as well as integrate it into other systems of interest, such as the effect of PTSD on catecholamines.

In summary, there appears to be a preponderance of evidence supporting the idea that patients with PTSD exhibit decreased cortisol concentrations compared with unaffected individuals, as well as disturbed feedback regulation of cortisol on the hypothalamus. This latter point has been demonstrated by enhanced ACTH suppression following exogenous glucocorticoid administration. Additionally, blunted cortisol responses over time may leave the sympathetic nervous system relatively unchecked, thus contributing to the tonic hypervigilance these patients experience. As might be expected, those with a history of more severe trauma or stress exhibit more severe symptomatology.

A. The Catecholamines: Epinephrine & Norepinephrine

There is limited literature on epinephrine and norepinephrine in the setting of PTSD, but the majority of the literature suggests that norepinephrine is elevated in such patients. Blanchard et al. examined plasma norepinephrine in Vietnam veterans with combat experience. Group one contained combat veterans with diagnosed PTSD and group two was comprised of combat veterans without PTSD. The veterans were exposed to auditory stimuli simulating a combat experience with increasing volume for three minutes. PTSD veterans exhibited significant increases in plasma norepinephrine from pre-stimulus and post-stimulus (p<0.001) compared to combat veterans without PTSD, who did not show changes due to the auditory stimulus. Moreover, veterans with PTSD who experienced an increase in plasma norepinephrine also showed a concomitant increase in heart rate. In addition, there was no difference in baseline norepinephrine levels between the two groups [26]. Geracioti et al., using a stressor, looked at serial cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) norepinephrine concentrations sampled via an indwelling spinal canal subarachnoid catheter over a number of hours. They discovered that CSF norepinephrine concentrations were significantly higher in the participants with PTSD than the healthy control group. Geracioti asserts that the higher baseline CSF norepinephrine concentrations were related to CNS hyper-activation in PTSD, even in the absence of a specific stressor [27]. Taken in the context of the data presented thus far, this CNS activation may be related to the previously mentioned elevations in CRH and underscores the theory that blunted cortisol fails to attenuate the sympathetic nervous system.

The cause of elevated levels of norepinephrine appears to be a low concentration of the norepinephrine transporter (NET) in the stressed state. The NET is responsible for attenuating signaling by clearing norepinephrine from synaptic clefts, thus resulting in lower levels of arousal. Expanding upon rodent studies in which repeated exposure to stress is associated with decreased NET in the locus coeruleus, Pietrzak et al. used Positron emission tomography (PET) with [11C]- methylreboxetine to assess NET availability in this crucial region. They compared healthy adult humans, patients exposed to trauma but without PTSD symptoms, and patients with PTSD symptoms, and found that PTSD was associated with significantly reduced NET availability in the locus coeruleus, and that greater norepinephrine activity with PTSD was associated with an increased severity of anxious arousal symptoms [28]. This established consistency among animal and human studies about stress exposure and attenuation of NET availability.

Correspondingly, Kosten et al. suggest that PTSD patients have increased sympathetic nervous system activity. They examined urinary norepinephrine and epinephrine levels at two-week intervals during the course of hospitalization without the use of a stressor. Patient groups included those with PTSD, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder type I (manic), paranoid schizophrenia, and undifferentiated schizophrenia. The patients with PTSD had significantly higher mean urinary norepinephrine and epinephrine levels than the other groups, and the higher levels were sustained throughout the hospitalization [29]. These data further suggest that evidence of persistent catecholamine elevations are not limited to PTSD and encompass a number of other psychiatric diagnoses.

In summary, human studies demonstrate increased levels of both plasma and CSF norepinephrine among subjects with PTSD, a finding also demonstrated in animal studies.

B. Thyrotropin (TSH) and the Thyroid Gland

The medical literature suggests that the pituitary-thyroid axis may be altered in patients with PTSD, but results are mixed, with the majority of research suggesting increased thyroid hormone concentrations. Goenjian et al. examined adolescents with PTSD and a history of trauma resulting from the Spitak earthquake in Armenia in 1988. The study population was divided into two groups: 33 adolescents who experienced trauma at the epicenter in Spitak, and 31 adolescents who lived at the periphery of the earthquake zone. The group exposed to trauma had significantly higher basal thyrotropin (TSH) concentrations than the non-trauma-exposed group, suggesting that higher TSH levels may reflect an underlying comorbid depression, which is known to be associated with hypothyroidism, or an agerelated, trauma-induced decrease in sensitivity to thyroid hormone feedback on the pituitary and/or hypothalamus [15]. Conversely, Olff et al. studied 39 chronic PTSD patients and 44 healthy volunteers and found that average TSH levels were lower in PTSD patients than in the controls after controlling for sex, age, BMI, and smoking, suggesting enhanced negative feedback from thyroid hormones [16]. These discrepant TSH data may be attributable to a number of potential confounders, including variable coping mechanisms, types of trauma, or other comorbidities.

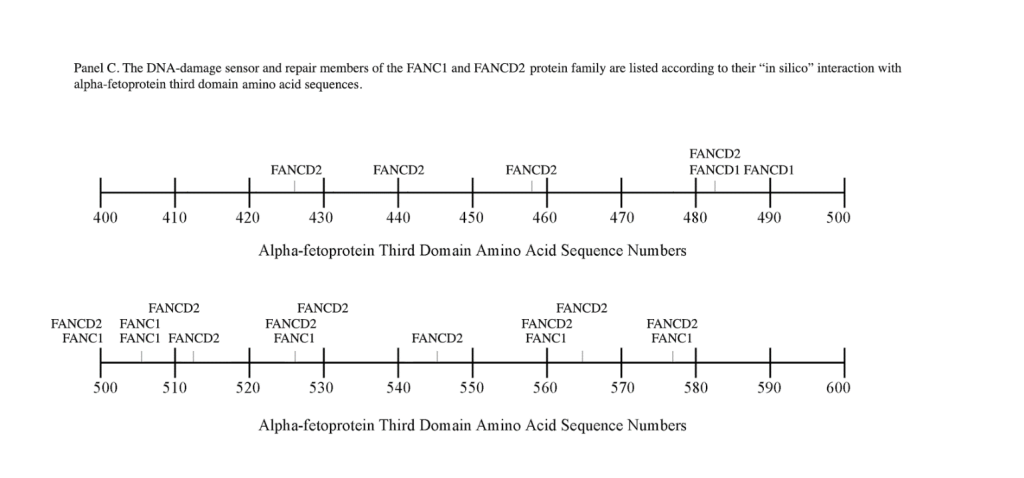

In effort to sort out these discrepant TSH findings, Wang et al. identified a positive correlation between levels of Total Triiodothyronine (TT3), Free T3 (FT3), and Total Thyroxine (TT4) and the frequency of PTSD symptoms [30]. The most significant relationship was observed between a measure of current PTSD symptoms (e.g., CAPS- 2 hyperarousal scores) and TT3. The authors suggest that these results might indicate a “high thyroid, high hyperarousal” PTSD subtype, or alternatively, might suggest a “high thyroid, high hyperarousal” phase in the course of PTSD. Similarly, Wang and Mason found elevations in serum FT3 levels and PTSD symptoms among World War II veterans, as shown in Figure 3. Specifically, they found a significant positive relationship between TT3 and FT3 and PTSD hyperarousal symptoms [31]. A multivariate analysis including all thyroid measures showed a significant overall difference between the PTSD group and the control group, with significant elevations of serum TT3, FT3, and the TT3/FT4 ratio in the World War II PTSD group as compared to the control subjects. No significant mean differences were found in levels of TT4, FT4, thyroid binding globulin (TBG), or TSH between the groups. Importantly, the observed alterations of thyroid function in conjunction with PTSD symptoms appear to be chronic and detectable more than 50 years after the war. These data show that the dominant finding among PTSD patients is elevated T3, and when taken in the context of the data previously presented, is consistent with in accordance with a poorly attenuated sympathetic nervous system that leads to greater systemic arousal.

![Figure 3. Mean Free T3, Free T4, and TSH concentrations in 12 World War II veterans with PTSD (solid bars) as compared to 18 healthy, age matched control subjects (stippled bars). Adapted from Wang et al. [30].](http://researchopenworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/EDMJ-2017-104_Fig_3.png)

Figure 3. Mean Free T3, Free T4, and TSH concentrations in 12 World War II veterans with PTSD (solid bars) as compared to 18 healthy, age matched control subjects (stippled bars). Adapted from Wang et al. [30].

Karlović et al. found significantly higher concentrations of TT3 compared to a control group in their study of 43 male Croatian soldiers with combat-related chronic PTSD and 39 healthy men [32]. There was a significant correlation between TT3 levels and the number of traumatic events experienced in both the overall PTSD group and in those with PTSD and comorbid alcohol dependence. Additionally, soldiers with chronic combat-related PTSD, with or without comorbid alcohol addiction, had significantly higher values of TT3 than controls. There was a significant correlation between TT3 levels and symptoms of increased arousal in both of the above groups. Mason et al. similarly evaluated 96 American combat veterans and 24 healthy controls [33], and they found moderately elevated TT4 levels (but not FT4 levels), as well as elevations in both TT3 and FT3, and elevated T3/T4 ratios among combat veterans with PTSD. They also found increases in TBG levels, but no difference in TSH levels. This same group conducted another study that compared thyroid hormone levels between Israeli combat veterans with PTSD and American combat veterans with PTSD and compared both groups to an unaffected group of combat veterans without PTSD. They found significantly higher mean TT3 levels among the veterans of both cultures with PTSD compared to the unaffected control group, but there was no significant difference found between TT3 levels when comparing the results of the Israeli combat veterans with PTSD to the American combat veterans with PTSD [34]. These data raise the question whether there are crosscultural or ethnic confounders to the findings of elevated T3 among PTSD patients.

In summary, patients with either a distant history of PTSD or a more recent PTSD diagnosis appear to have significant alterations in the pituitary-thyroid axis. An elevation of T3 is the most consistent finding, and this elevation appears to be correlated with the common symptom of hyperarousal. Alterations in the feedback of thyroid hormone on TSH secretion also appears to be common in patients with PTSD.

C. Prolactin

Although prolactin is a well-recognized stress-response hormone, little research has been done examining prolactin concentrations in individuals with PTSD [35, 36]. Vidović et al. measured prolactin levels in 39 Croatian war veterans with PTSD and 25 healthy volunteers on two occasions approximately 6 years apart and found prolactin levels were significantly higher in the PTSD subjects at both assessments [35]. Grossman et al. studied veterans exposed to combat with and without PTSD, as well as healthy controls, and found that both groups of veterans, with and without PTSD, demonstrated significantly greater prolactin suppression in response to dexamethasone as compared to healthy control participants [36]. The authors suggest that perhaps the increased suppression of prolactin is associated with combat exposure rather than with PTSD. Olff et al. reported significantly lower basal prolactin concentrations in patients with PTSD compared to healthy volunteers, and although this finding was not affected by adjustment for depression, smoking, BMI or demographic variables, adjustment for age did obviate the observation, with prolactin levels being significantly lower in the older participants [16]. Dinan et al. reported no significant difference in prolactin between female patients with PTSD and healthy controls, suggesting normal functioning of the 5-Hydroxytryptophan (5-HT) receptor system [37]. In summary, there is no consensus that the regulation of prolactin is routinely disrupted in PTSD.

D. Somatostatin and Growth Hormone:

There are a limited number of studies examining serum growth hormone (GH) and GH regulation in patients with PTSD. Van Liempt et al. assessed nocturnal GH secretion in 13 veterans with PTSD, 15 unaffected trauma controls, and 15 healthy controls [38]. They reported that plasma GH was significantly reduced in the PTSD group compared to healthy controls. The authors also reported a correlation between sleep fragmentation, which was more common in the PTSD subjects, and GH secretion. When given a memory test before and after sleep, the veterans with PTSD who awoke more frequently during the night and who had lower GH secretion were able to remember fewer words during the test. This suggests that sleep dependent memory may be interrupted by frequent awakenings and/or reduced secretion of GH. After an earthquake in Northern China, Song et al. assessed earthquake survivors with PTSD, subclinical PTSD (i.e., subjects who met all but the severity criterion of a DSM-IV diagnosis of PTSD), and healthy controls. The survivors with PTSD, but not those with subclinical PTSD, had significantly higher serum GH levels than did the healthy controls. There was no statistically significant difference in GH levels between the PTSD participants and those with subclinical PTSD [20]. As previously discussed, Goenjian et al. examined 8th grade students who lived near the epicenter of an earthquake in Spitak, Armenia, as well as others who were from the periphery of the earthquake zone in Yerevan, and they found significantly higher pre-exercise concentrations of GH in the group from Spitak compared to the group from Yerevan [15]. In general, these discrepant data do not support meaningful patterns of GH dysregulation among PTSD patients at this time.

Morris et al. explored the GH response to clonidine stimulation testing in subjects with combat-related PTSD but without depression, PTSD plus depression, and healthy veteran controls, and they found a significantly blunted GH response in the patients with PTSD without depression [39], but the GH response to clonidine among combat veterans with depression was not different from that of control subjects. Conversely, Dinan et al. studied the GH response to stimulation with desipramine and found no significant difference between female trauma patients with PTSD and unaffected control subjects [37]. These two studies also show discrepancy in GH patterns and fail to demonstrate the statistical significance of their findings.

To examine the question of growth hormone’s role in PTSD in a different way, Bremner et al. examined somatostatin, a welldocumented endogenous inhibitor of GH secretion. Their study reported higher CSF somatostatin concentrations in PTSD patients than in control subjects without PTSD, and further, that CSF concentrations of somatostatin were significantly correlated to CSF CRH concentrations in Vietnam combat veterans but not in healthy controls [5]. These data appear to extend the previously discussed findings pertaining to paradoxically elevated CSF CRH levels.

In summary, higher CSF concentrations of somatostatin and blunted responses to GH stimulation testing among patients with PTSD suggest that dysregulation of GH secretion may be associated with the diagnosis of PTSD, but the role of this dysregulation in the etiology or pathogenesis of the condition remains unclear.

E. Other Hormones (Oxytocin, Vasopressin, Testosterone)

Very little research has been done to explore the relationship between oxytocin and PTSD. Heim et al. examined women who experienced different severities of childhood abuse and found that decreased CSF oxytocin concentrations were associated with maltreatment and emotional abuse. Not all of the women in this study had PTSD, however, and when examined, it was found that CSF oxytocin levels were not associated with PTSD [40]. Research into the potential therapeutic effects of oxytocin as a memory enhancer and as a hormone that evokes a “sense of safety” in settings other than PTSD, is only in its infancy [41,42].

There is also a dearth of research exploring the relationship between Vasopressin and PTSD. Pitman, Orr and Lasko examined the effects of intranasal vasopressin on the heart rate, skin conductance, and lateral frontalis electromyographic (EMG) responses during personal combat imagery among 43 Vietnam veterans with PTSD in a double-blind, placebo controlled study, and found that vasopressin had a specific effect on EMG responses [41]. Specifically, lateral frontalis reactivity was greater during the viewing of personal combat imagery with vasopressin than with either placebo or oxytocin administration. The authors summarize that the findings are consistent with a potential role for stress hormones in PTSD symptomatology, but that the lack of a control group without PTSD prohibits firm conclusions.

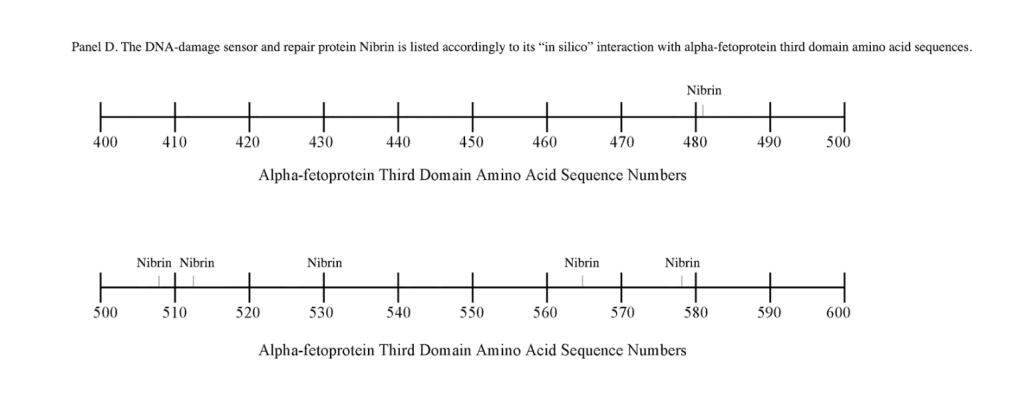

Literature on testosterone concentrations in male patients with PTSD has yielded mixed results, with some literature reporting elevated testosterone concentrations among males with PTSD, but other reports finding no statistically significant relationship. As shown in Figure 4, Karlović et al. studied four groups of patients: 17 combat soldiers with PTSD and no comorbid psychiatric disorders, 31 combat soldiers with PTSD and comorbid alcohol dependence, 18 combat soldiers with PTSD and comorbid major depression, and 34 healthy control combat soldiers without PTSD or other psychiatric disorders [43]. Analysis by ANCOVA found that patients with “pure” PTSD had significantly higher serum testosterone concentrations as compared to patients who had PTSD combined with depression or alcohol dependence. Importantly, the entire group of PTSD subjects, without considering comorbid conditions, showed no significant differences in basal serum testosterone concentrations as compared to control subjects. Mason et al. longitudinally evaluated androgen levels among individuals being treated as inpatients for PTSD, major depression, bipolar disorder, or paranoid schizophrenia, as well as 24 healthy male control subjects [44]. They found that the patients with PTSD had significantly higher basal serum testosterone levels compared to patients with major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder at all test points. At the last testing point, the PTSD group also had a statistically higher serum testosterone level than the control group. The PTSD group and the group with paranoid schizophrenia did not significantly differ with the group who had major depression at any time.

![Figure 4. Approximate median fasting morning concentrations of total testosterone among patients with combat-related PTSD with and without comorbid conditions as compared with healthy control combatants. Adapted from Karlovic et al. [42].](http://researchopenworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/EDMJ-2017-104_Fig_4.png)

Figure 4. Approximate median fasting morning concentrations of total testosterone among patients with combat-related PTSD with and without comorbid conditions as compared with healthy control combatants. Adapted from Karlovic et al. [42].

Conversely, Spivak et al. found no statistically significant difference in morning testosterone levels between chronically untreated PTSD subjects and healthy control subjects. The participants included 21 Israeli combat veterans with PTSD and 18 healthy Israeli males with some combat exposure but no PTSD. The authors suggest that a possible explanation for the difference between their findings and the findings of others may relate to the greater severity of PTSD in these untreated subjects [45].

In summary, although certain subgroups of subjects with PTSD appear to have increased concentrations of testosterone compared to other subgroups, there are not consistently increased levels of testosterone among male PTSD patients as compared to healthy control subjects in observational studies. Although potentially promising, the therapeutic efficacy of treating PTSD patients with oxytocin agonists, vasopressin, or anti-androgen therapy, remains to be established.

Part 2: Caution Surrounding Assay Methodologies and Critical Review of the Literature

Schumacher et al. stress the need for critical interpretation on the part of the reader in the context of the relationship between hormonal perturbations and PTSD [46]. They underscore the necessity for using well-validated assays in any study in which hormone concentrations are a critical component. Moreover, the DSM has undergone serial updates since PTSD achieved its formal diagnosis classification in 1980, and this evolution may affect sample selection among older studies. Secondly, there are a wide variety of self-assessment tools for PTSD, and responses to these instruments will vary across countries, cultures and languages, and the instruments themselves will undergo revisions through the years. Thus, the methods of assessment in 1980 may bear little resemblance to methods used today. Moreover, techniques for monitoring hormone dynamics in 2016 are more precise than they were 36 years ago. All of these factors must be considered when interpreting data that span decades and cultural or geographical boundaries. Thus, it is important that the reader carefully consider research data to tease out important confounders, especially as new data and improved assays become available.

Schumacher et al. go on to declare that “gas or liquid chromatography (GC or LC) that is coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (MS) represent the gold standards” for accurate and sensitive analyses of steroids, but they acknowledge that this methodology is associated with high cost [46]. The tandem GC/MS technique markedly reduces molecular interference and background noise. In instances where multiple steroid isomers have similar MS profiles, the preceding chromatography should have already separated these isomers into different strata. Unfortunately, the utility of radioimmunoassays (RIA) that have been employed since the 1970s are limited because steroid hormones have low molecular weights and are not especially immunogenic, and the use of validated RIAs that are preceded by specific purification and separation steps has decreased over time, in favor of the use of frequently unvalidated commercial kits due to ease of use. Furthermore, publication requirements on the part of reference journals have become less strict, so the burden of validation ultimately lies on the reader’s attention to the RIA procedures that are published. The authors urge caution when a study’s assay methodology is not described in detail.

Yehuda noted that cortisol measured in a single venous sample is not a reliable estimate of basal cortisol dynamics, especially if the process of venipuncture (or anticipation thereof) induces transient fluctuations of the hormone [12]. The advent of salivary or hair cortisol sampling offer two ways to address the confounder of acute sampling-related stress. Another strategy is to obtain serial venous samples via IV catheter and allow patients to recover from the acute stress of IV placement prior to sampling. It is given that every study has limitations, ranging from small study sizes, gender differences, variable types of trauma, comorbid depression, substance abuse, unidentified confounders, mishandled samples, or medication regimens may impact interpretation and external validity of results [21,47]. In sum, it is reasonable to consider that confounding variables will be a significant factor when considering the complex and poorly understood nature of psychiatric disease [47-58].

Summary and Conclusions

In this report, we reviewed 58 studies published between 1985 and 2016 that examined the hormonal dynamics of PTSD and their potential implications for novel therapeutics in the treatment of PTSD. With respect to the HPA Axis, the majority of research supports the finding of lower cortisol levels and an impaired negative feedback mechanism (as evidenced by enhanced ACTH suppression following dexamethasone administration) that may be rooted in decreased CRH secretion. This suggests a potential future treatment that targets CRH1 receptors with, for example, a long-acting CRH analogue.

Multiple studies demonstrate that norepinephrine levels are elevated in patients with PTSD compared to healthy controls, supporting the concept of “adrenal overdrive” in such patients. Only one study shows an elevation in both epinephrine and norepinephrine.

There also appears to be a consistent alteration in the pituitarythyroid axis, with elevated T3 levels being the most typical finding, and this elevation consistently correlates with hyperarousal symptoms. Alterations in the feedback of thyroid hormone on TSH secretion may also be operative in patients with PTSD, as these patients are more likely to show TSH on the low end of the normal range.

While there is no consistent alteration in prolactin levels in individuals with PTSD, there are higher CSF concentrations of both somatostatin and blunted responses to GH stimulation testing among patients with PTSD. This suggests that dysregulation of GH secretion may be associated with the diagnosis of PTSD, but the role of this dysregulation in the etiology or pathogenesis of the condition remains unknown. Finally, although certain subgroups of subjects with PTSD may have increased concentrations of testosterone compared to other subgroups, there are not consistently increased levels of testosterone among PTSD patients as compared to healthy controls. Although promising, the therapeutic potential of oxytocin agonists, or with testosterone or vasopressin antagonists, remains to be established.

Overall the neuroendocrine patterns observed over time suggest a complex interplay among the adrenal axis, thyroid hormones, catecholamines and somatostatin, but additional work is required to elucidate potential targets for therapy. In short, the pathophysiology of PTSD and its relationship to neuroendocrine dysregulation function is a multifactorial and dynamic process that exists on a spectrum with other psychiatric and organic dysfunctions. The concept of being able to understand PTSD as an isolated entity is probably unrealistic and counterintuitive to the needs of treating the whole person. However, accumulating evidence is showing that the cornerstones of hormonal dysregulation (summarized in Table 1) may provide an important framework for determining how to mitigate the effects of exposure to trauma and how to optimize plan management practices in the future.

Table 1. Summary of comparisons obtained from this literature review of hormone abnormalities related to PTSD as compared to controls. Blank cells indicate no data available. A dash ( – ) indicates that data showed no differences.

| Hormone |

Plasma |

CSF |

Urine |

Saliva |

Hair |

References |

| TSH |

↑↓ |

|

|

|

|

15, 29 |

| FT4 |

– |

|

|

|

|

15, 29 |

| FT3 |

↑ |

|

|

|

|

15, 29-32 |

| TT4 |

↑ |

|

|

|

|

15, 29, 32 |

| TT3 |

↑ |

|

|

|

|

15, 29-33 |

| PRL |

↑↓ |

|

|

|

|

35 |

| Estrogen

(FM only) |

↑ |

|

|

|

|

66 |

| Progesterone

(FM only) |

↑ |

|

|

|

|

66 |

| Testosterone

(M only) |

↑ |

|

|

|

|

42 – 44 |

| CRH |

|

↑ |

|

|

|

6, 8, 10, 11, 14-16, 64, 67, 69 |

| ACTH |

↑↓ |

|

|

|

|

9, 10, 11, 14, 15, 16, 64 |

| Cortisol |

↓ |

|

↑↓ |

↓ |

↓↑ |

7, 11-17, 19, 20, 22-24, 36, 46, 48, 64, 70 |

| Somatostatin |

|

↑ |

|

|

|

4 |

| GH/IGF-1 |

↑↓ |

|

|

|

|

19, 36-38, 61 |

| Oxytocin |

– |

|

|

|

|

39, 40, 41 |

| Vasopressin |

– |

|

|

|

|

40 |

| Norepinephrine |

↑ |

↑ |

↑ |

|

|

20, 25-28, 46 |

| Epinephrine |

|

|

↑ |

|

|

20, 28, 46 |

List of Abbreviations

5-HT: 5-Hydroxytryptophan

ACTH: Adrenocorticotropic Hormone

ADHD: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

ANCOVA: Analysis of Covariance

BMI: Body Mass Index

CAPS-2: Clinician Administered PTSD Scale, v. 2

CBG: Corticotropin Binding Globulin

CRH: Corticotropin Releasing Hormone

CSF: Cerebrospinal Fluid

DSM-III: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, v. 3

DSM-IV: Diagnositic and Statistical Manual, v. 4

EMG: Electromyography

FSH: Follicle Stimulating Hormone

FT3: Free T3

GH: Growth Hormone

HCC: Hair Cortisol Concentration

HPA: Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal

LC: Liquid Chromatography

LH: Leutinizing Hormone

LITE-PR: Lifetime Incidence of Traumatic Events-Parent Report

NATO: North Atlantic Treaty Organization

NET: Norepinephrine Transporter

PCL-C: PTSD Check List-Civilian Version

PCL-M: PTSD Check List-Military Version

PRL: Prolactin

PTSD: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

PVN: Paraventricular Nucleus

RIA: Radioimmunoassay

SCID: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV

SCL-90-R: Symptom Check List-Revised

SNS: Sympathetic Nervous System

T3: Tri-iodothyronine

T4: Thyroxine

TBG: Thyrotropin Binding Globulin

TSH: Thyroid Stimulating Hormone

TT3: Total T3

TT4: Total T4

UN: United Nations

References

- Hourani L, Council C, Hubal R, Strange L (2011) Approaches to the primary prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder in the military: A review of the stress control literature. Military Medicine 176: 721-730.

- Buchanan C, Kemppainen J, Smith S, MacKain S, Wilson C (2011) Awareness of posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans: A female spouse/intimate partner perspective. Military Medicine 176: 743-751.

- Grodin M, Piwowarczyk L, Fulker D, Bazazi A, Saper R (2008) Treating survivors of torture and refugee trauma: A preliminary case series using qigong and t’ai chi. Journal of Alternative Complementary Medicine 14: 801-806.

- Nader N1, Chrousos GP, Kino T (2010) Interactions of the circadian CLOCK system and the HPA axis. Trends Endocrinol Metab 21: 277-286. [crossref]

- Bremner J, Licinio J, Darnell A, et al. (1997) Elevated CSF corticotropin-releasing factor concentrations in posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 154:624-629.

- Savic D, Knezevic G, Damjanovic S, Spiric Z, Matic G (2012) The role of personality and traumatic events in cortisol levels–where does PTSD fit in? Psychoneuroendocrinology 37: 937-947. [crossref]

- Muhtz C, Wester M, Yassouridis A, Wiedemann K, Kellner M (2008) A combined dexamethasone/corticotropin-releasing hormone test in patients with chronic PTSD–first preliminary results. J Psychiatr Res 42: 689-693.

- De Kloet CS, Vermetten E, Heijnen CJ, Geuze E, Lentjes EG, Westenberg HG (2007) Enhanced cortisol suppression in response to dexamethasone administration in traumatized veterans with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology 32: 215-226.

- Kellner M, Yassouridis A, Hübner R, Baker DG, Wiedemann K (2003) Endocrine and cardiovascular responses to corticotropin-releasing hormone in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: a role for atrial natriuretic peptide? Neuropsychobiology 47: 102-108.

- Yehuda R, Golier JA, Halligan SL, Meaney M, Bierer LM (2004) The ACTH response to dexamethasone in PTSD. Am J Psychiatry 161: 1397-1403. [crossref]

- Ströhle A, Scheel M, Modell S, Holsboer F (2008) Blunted ACTH response to dexamethasone suppression-CRH stimulation in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychiatr Res 42: 1185-1188.

- Yehuda R (1997) Sensitization of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 821: 57–75.

- Yehuda R, Kahana B, Binder-Brynes K, Southwick SM, Mason JW, et al. (1995) Low urinary cortisol excretion in Holocaust survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 152: 982-986.

- Boscarino JA (1996) Posttraumatic stress disorder, exposure to combat, and lower plasma cortisol among Vietnam veterans: findings and clinical implications. J Consult Clin Psychol 64:191-201.

- Goenjian AK, Pynoos RS, Steinberg AM, et al. (2003) Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activity among Armenian adolescents with PTSD symptoms. J Trauma Stress 16: 319-323.

- Olff M, Güzelcan Y, de Vries GJ, Assies J, Gersons BP (2006) HPA- and HPT-axis alterations in chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology 31: 1220-1230.

- Kanter ED, Wilkinson CW, Radant AD, et al. (2001) Glucocorticoid feedback sensitivity and adrenocortical responsiveness in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 50: 238-45.

- Wahbeh H, Oken BS (2013) Salivary cortisol lower in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress 26: 241-248. [crossref]

- Wang HH, Zhang ZJ, Tan QR, et al. (2010) Psychopathological, biological, and neuroimaging characterization of posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of a severe coal mining disaster in China. J Psychiatr Res 44: 385-392.

- Song Y, Zhou D, Wang X (2008) Increased serum cortisol and growth hormone levels in earthquake survivors with PTSD or subclinical PTSD. Psychoneuroendocrinology 33: 1155-1159. [crossref]

- Pitman R, Orr S. Twenty-four-hour urinary cortisol and catecholamine excretion in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry 27: 245-247.

- Gotovac K, Sabioncello A, Rabatic S, Berki T, Dekaris D (2003) Flow cytometric determination of glucocorticoid receptor (GCR) expression in lymphocyte subpopulations: Lower quantity of GCR in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Clin Exp Immunol 131: 335–339.

- Wheler GH1, Brandon D, Clemons A, Riley C, Kendall J, et al. (2006) Cortisol production rate in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91: 3486-3489. [crossref]

- Simmons JG, Badcock PB, Whittle SL, et al. (2016) The lifetime experience of traumatic events is associated with hair cortisol concentrations in community-based children. Psychoneuroendocrinology 63: 276-281.

- Yoon SA, Weierich MR (2016) Salivary biomarkers of neural hypervigilance in trauma-exposed women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 63: 17-25. [crossref]

- Blanchard EB, Kolb LC, Prins A, Gates S, McCoy GC (1991) Changes in plasma norepinephrine to combat-related stimuli among Vietnam veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 179: 371-373.

- Geracioti TD Jr, Baker DG, Ekhator NN, West SA, Hill KK, et al. (2001) CSF norepinephrine concentrations in posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 158: 1227-1230. [crossref]

- Pietrzak RH, Gallezot JD, Ding YS, Henry S, Potenza MN, Southwick SM, et al. (2013) Association of posttraumatic stress disorder with reduced in vivo norepinephrine transporter availability in the locus coeruleus. JAMA Psychiatry 70: 1199-1205.

- Kosten TR, Mason JW, Giller EL, Ostroff RB, Harkness L (1987) Sustained urinary norepinephrine and epinephrine elevation in post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology 12: 13-20.

- Wang S, Mason J, Southwick S, Johnson D, Lubin H, Charney D (1995) Relationships between thyroid hormones and symptoms in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychosom Med 57: 398-402.

- Wang S, Mason J (1999) Elevations of serum T3 levels and their association with symptoms in World War II veterans with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: Replication of findings in Vietnam combat veterans. Psychosom Med 61: 131-138.

- Karlovic D, Marusic S, Martinac M (2004) Increase of serum triiodothyronine concentration in soldiers with combat-related chronic post-traumatic stress disorder with or without alcohol dependence. Wien Klin Wochenschr 116: 385-390.

- Mason J, Southwick S, Yehuda R, et al. (1994) Elevation of serum free triiodothyronine, total triiodothyronine, thyroxine-binding globulin, and total thyroxine levels in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 51: 629-641.

- Mason J, Weizman R, Laor N, et al. (1996) Serum triiodothyronine elevation in Israeli combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: a cross-cultural study. Biol Psychiatry 39: 835-838.

- Vidovic´ A, Gotovac; K, Vilibic´ M, et al. (2011) Repeated assessments of endocrine- and immune-related changes in posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuroimmunomodulation. 18: 199-211.

- Grossman R, Yehuda R, Boisoneau D, Schmeidler J, Giller EL Jr. (1996) Prolactin response to low-dose dexamethasone challenge in combat-exposed veterans with and without posttraumatic stress disorder and normal controls. Biol Psychiatry 40: 1100-1105.

- Dinan TG1, Barry S, Yatham LN, Mobayed M, Brown I (1990) A pilot study of a neuroendocrine test battery in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 28: 665-672. [crossref]

- Van Liempt S, Vermetten E, Lentjes E, Arends J, Westenberg H (2011) Decreased nocturnal growth hormone secretion and sleep fragmentation in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder; potential predictors of impaired memory consolidation. Psychoneuroendocrinology 36: 1361-1369.

- Morris P, Hopwood M, Maguire K, Norman T, Schweitzer I (2004) Blunted growth hormone response to clonidine in post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology 29: 269-278.

- Heim C, Young LJ, Newport DJ, Mletzko T, Miller AH, et al. (2009) Lower CSF oxytocin concentrations in women with a history of childhood abuse. Mol Psychiatry 14: 954-958. [crossref]

- Pitman RK, Orr SP, Lasko NB (1993) Effects of intranasal vasopressin and oxytocin on physiologic responding during personal combat imagery in Vietnam veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Research 48:107-117.

- Olff M, Langeland W, Witteveen A, Denys D (2010) A psychobiological rationale for oxytocin in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. CNS Spectr 15: 522-530. [crossref]

- Karlovic D, Serretti A, Marcinko D, Martinac M, Silic A, Katinic K (2012) Serum testosterone concentration in combat-related chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychobiology 65: 90-95.

- Mason JW, Giller EL, Kosten TR, Wahby VS (1990) Serum testosterone levels in post-traumatic stress disorder inpatients. J Traum Stress 3: 449–457.

- Spivak B, Maayan R, Mester R, Weizman A (2003) Plasma testosterone levels in patients with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychobiology 47: 57-60.

- Schumacher M, Guennoun R, Mattern C, et al. (2015) Analytical challenges for measuring steroid responses to stress, neurodegeneration and injury in the central nervous system. Steroids 103: 42-57.

- Lemieux AM and Coe CL (1995) Abuse-related posttraumatic stress disorder: Evidence for chronic neuroendocrine activation in women. Psychosom Med 57: 105-115.

- Morris P, Hopwood M, Maguire K, Norman T, Schweitzer I (2003) Blunted growth hormone response to clonidine in post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology 29: 269-278.

- Ludascher P, Schmahl C, Feldmann Jr RE, Kleindienst N, Scheider M, et al. (2015) No evidence for differential dose effects of hydrocortisone on intrusive memories in female patients with complex post-traumatic stress disorder–a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Journal of Psychopharmacology 29: 1077-1084.

- Kim EJ, Pellman B, Kim JJ (2015) Stress effects on the hippocampus: a critical review. Learn Mem 22: 411-416. [crossref]

- Belda X, Fuentes S, Daviu N, Nadal R, Armario A (2015) Stress-induced sensitization: The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and beyond. The International Journal on the Biology of Stress 18: 269-279.

- Thompson DJ, Weissbecker I, Cash E, Simpson DM, Daup M, Sephton SE (2015) Stress and cortisol in disaster evacuees: An exploratory study on associations with social protective factors. Applied Psychophysiology Biofeedback 40: 33-44.

- Wassell J, Rogers SL, Felmingam KL, Bryant RA, Pearson J (2015) Sex hormones predict the sensory strength and vividness of mental imagery. Biol Psychol 107: 61-68. [crossref]

- Contoreggi C (2015) Corticotropin releasing hormone and imaging, rethinking the stress axis. Nucl Med Biol 42: 323-339. [crossref]

- Nagaya N, Maren S (2015) Sex, steroids, and fear. Biol Psychiatry 78: 152-153. [crossref]

- Bangasser DA, Kawasumi Y (2015) Cognitive disruptions in stress-related psychiatric disorders: A role for corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) Hormones and Behavior 76: 125-135.

- Duan H, Wang L, Zhang L, Liu J, Zhang K, Wu J (2015) The relationship between cortisol activity during cognitive task and posttraumatic stress symptom clusters. PLOS One 10: 1-13.

- Greene-Shortridge TM1, Britt TW, Castro CA (2007) The stigma of mental health problems in the military. Mil Med 172: 157-161. [crossref]

![Figure 1. Salivary cortisol response to awakening among 23 Dutch Military Veterans with PTSD (solid squares) as compared to 24 Healthy Control subjects (solid circles). Adapted from de Kloet et al. [7].](http://researchopenworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/EDMJ-2017-104_Fig_1.png)

![Figure 2. Percent suppression of ACTH from baseline by 0.5 mg of dexamethasone overnight among patients with PTSD versus patients without PTSD. Adapted from Yehuda et al. [11].](http://researchopenworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/EDMJ-2017-104_Fig_2.png)

![Figure 3. Mean Free T3, Free T4, and TSH concentrations in 12 World War II veterans with PTSD (solid bars) as compared to 18 healthy, age matched control subjects (stippled bars). Adapted from Wang et al. [30].](http://researchopenworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/EDMJ-2017-104_Fig_3.png)

![Figure 4. Approximate median fasting morning concentrations of total testosterone among patients with combat-related PTSD with and without comorbid conditions as compared with healthy control combatants. Adapted from Karlovic et al. [42].](http://researchopenworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/EDMJ-2017-104_Fig_4.png)