DOI: 10.31038/CST.2016122

Abstract

Cancer of the lungs is among the leading causes of cancer in the world. It has two forms; small cell lung cancer (SCLC), and non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). NSCLC constitutes about 85% of cases of lung cancer. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and its mutations are found to have an important role in this cancer. Therefore, EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) can work effectively against NSCLC. Gefitinib, which is a first generation TKI, and Afatinib, which is a second-generation TKI, are effective as a first-line therapy for advanced NSCLC. Erlotinib is effective as a second-line therapy for advanced NSCLC. However, further studies are required in cases of combination of TKIs with chemotherapeutic agents as some studies show negative outcomes while others show better outcomes. Patients of advanced NSCLC can also develop resistance to TKIs, and in that case, some other therapeutic strategies such as radiotherapy can help. This paper deals with several aspects of NSCLC, EGFR mutations, TKIs, and their resistance. It also gives future guidelines in the use of TKIs against NSCLC.

Key words

Lung cancer, NSCLC, Target therapy, EGFR, TKI

Introduction

Lung cancer is among the leading causes of cancer in both genders in the U.S. The median five-year survival rate for the cancer is about 5% in the world. There are two main categories of the lung cancer based on their histological characteristics; one is Small Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC) and the other is Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) [1].

SCLC constitutes about 15% of the cases of lung cancer and NSCLC constitutes about 85% of the cases of lung cancer. Most of the patients of NSCLC have unresectable and advanced disease (in the stage of IIIB or stage IV). Median survival of the patients of NSCLC is below 6 months, if it is not properly treated. The preliminary therapeutic strategy usually involves the use of platinum agents along with taxane.

Another highly accepted therapeutic strategy in the treatment of the patients of advanced NSCLC is to target the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [2].

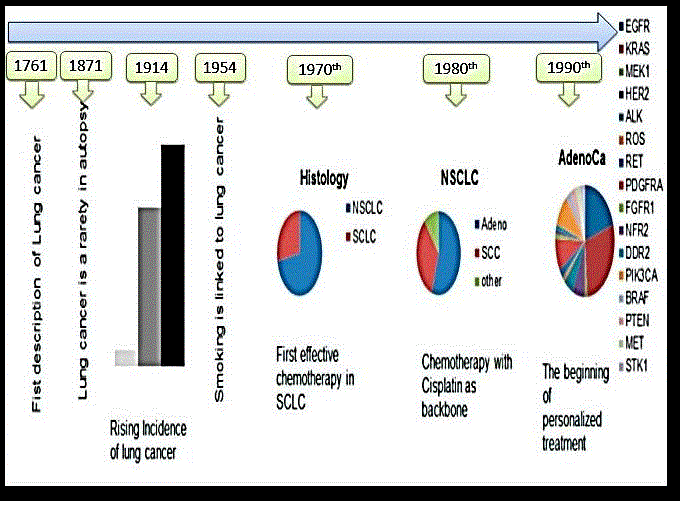

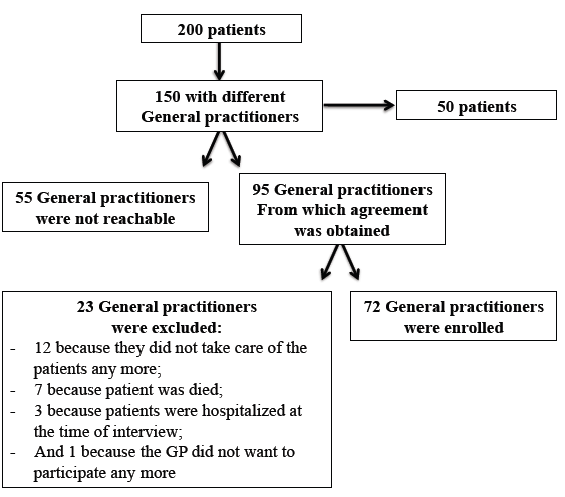

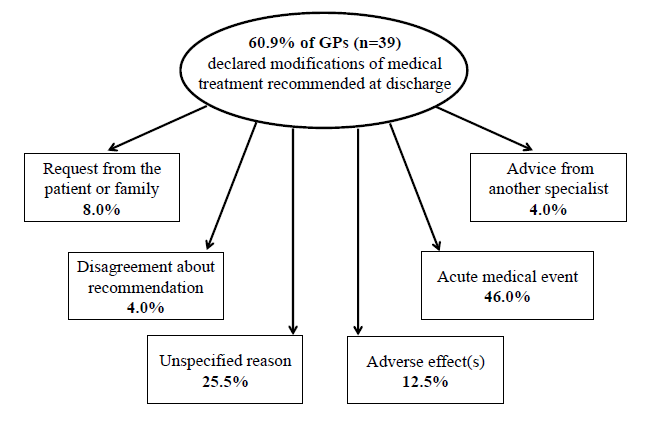

Recently, the NSCLC classified as squamous cell carcinoma and non-squamous which include adenocarcinoma and large cell type [Figure 1].

Figure 1. Story of lung cancer diagnosis

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR)

Epidermal growth factor was initially studied by Stanley Cohen and collaborators [3], who got Nobel Prize in 1986 for this discovery, and in 1988, Mendelsohn and collaborators obtained the receptors showing that EGFR can be a promising anticancer target [Table 1].

In May 2004, researchers found that the somatic mutations in the kinase domain of EGFR are positively related to the potent response of EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (TKIs) against advanced NSCLC [2].

EGFR, also known as ErbB1, and it belongs to receptors commonly referred to as receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) of the family of ErbB. Among the other members of the family of these receptors are ErbB2 (also known as HER2), ErbB3 (also known as HER3), and ErbB4 (also known as HER4) [4].

All of these receptors share a structural architecture consisting of a transmembrane domain, an extracellular ligand-binding domain, as well as an intracellular domain having tyrosine kinase activity to transducer the signals. The attachment of the ligand to EGFR starts a series of intracellular signaling that finally results in the appearance of cellular effects as cell proliferation as well as survival [2].

Table 1. EGFR TKI in the first line treatment of NSCLC compared with chemotherapy: phase III trials

| Study | No. patients | TKI | Control arm | Median PFS | P value |

| IPASS | 1217 216 mutant EGFR 176 non mutant |

Gefitinib | Carbo/paclitaxel | 9.8 vs 6.4 | significant |

| WJTOG-3405 | 177 all Mutant | Gefitinib | Cisplatin/Docetaxel | 9.2 vs 6.3 | significant |

| NEJ-02 | 230 all mutant | Gefitinib | Carbo/paclitaxel | 10.8 vs 5.4 | significant |

| First signal | 313 42 Mutant EGFR |

Gefitinib | Cisplatin/Gem | 8 vs 6.4 | significant |

| OPTIMAL | 165 all mutant | Erlotinib | Carbo/Gem | 13.1 vs 4.6 | significant |

| EURTAC | 173 all mutant | Erlotinib | Platinum based + (Gem or Doct.) |

9.7 vs 5.2 | significant |

| LUX-lung 3 | 345 all mutant | Afatinib | Cisplatin/pemetrexed | 11.1 vs 6.9 | significant |

| LUX-lung 6 | 364 all mutant | Afatinib | Cisplatin/Gem | 11 vs 5.6 | significant |

IPASS: Iressa Pan-Asia Study

NEJ: North East Japan

FIRST-SIGNAL: First-line Single Agent Iressa Versus Gemcitabine and Cisplatin Trial in Never-Smokers with Adenocarcinoma of the Lung;

OPTIMAL: Randomised Phase III Study Comparing First-line Erlotinib versus Carboplatin Plus Gemcitabine in Chinese Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients with EGFR Activating Mutations;

EURTAC: Erlotinib versus Standard Chemotherapy as First-line Treatment for European Patients with Advanced EGFR Mutation-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer;

LUX-Lung 3: Phase III Study of Afatinib or Cisplatin Plus Pemetrexed in Patients With Metastatic Lung Adenocarcinoma With EGFR Mutations;

LUX-Lung 6: a Randomized, Open Label, Phase III Study of Afatinib Versus Gemcitabine/Cisplatin as First-line Treatment for Asian Patients With EGFR Mutation-Positive Advanced Adenocarcinoma of the Lung;

EGFR Mutations

EGFR mutations were first considered as important cancer causing factors when gefitinib, which is among the first TKIs developed to work on the EGFR intracellular tyrosine kinase domain, showed significant decrease in the size of tumor in some patients having EGFR mutations. Mutations in the EGFR tyrosine kinase are found in nearly 15% of NSCLC adenocarcinomas in the U.S., and it is most commonly found in women and non-smokers. However, incidences of the disease in East Asian populations range from 22% to 62% [2].

In NSCLC, two most commonly encountered EGFR mutations include L858R mutation in exon 21 as well as the exon 19 deletions. Both of these mutations are drug sensitizing and represent over 85% of EGFR mutations. Research shows that purified intracellular domain of EGFR L858R and the representative deletion mutant show a huge difference in sensitivity to EGFR TKIs as compared to wild-type receptor [2, 5].

It has been found that exons 18-21 results in the coding of a part of the EGFR tyrosine kinase domain and T to G mutation in exon 21 is considered as the most frequently found alteration resulting in the replacement of arginine with leucine at the position of 858 (L858R). It has also been found that in the exon 19 deletion (del.), there is a removal of four amino acids [2, 6].

EGFR mutations with L858R and del 19 can activate EGFR signalling pathway in the mutant EGFR-positive cancer causing cells. Some of the mutations also result in higher level of sensitivity to TKIs as compared to the cases having wild-type EGFR. On the other hand, resistance mutations can also be found either in the start of the mutations or after sustained exposure to TKIs. Some of the most important examples of EGFR mutations resulting in resistance are PTEN, KRAS, and BRAF mutations [7] that are commonly involved in developing resistance to EGFR TKIs in cases of NSCLC.

Other common resistance mutations are T790M in the EGFR gene, which can be primary or acquired, and also epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and MET amplification, which are usually acquired.

Some other EGFR mutations of unidentified clinical significance can also occur in the advanced NSCLC. However, they are small in number as compared to the well-known EGFR mutations, which are of clinical importance. These mutations involve the substitution of amino acid in G719, E709, L861, and S768. Their connection to the efficacy of EGFR TKIs needs further studies.

The mutation divided into favorable and un-favorable in which the mutation in L861 and G719 are rare but it can result in favorable efficacy of EGFR TKIs, whereas other mutations can result in poor responses to EGFR TKIs.

Use of EGFR Tkis to Treat NSCLC

Gefitinib, which is a first generation EGFR TKI, got accelerated approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), in 2003, for the treatment of advanced NSCLC as a second-line treatment. Studies showed the efficacy of the drug in the form of response rate (RR) of over 9% in Caucasian participants and over 25% in Japanese participants. In the year 2004, erlotinib got approval for the treatment of the cancer.

It was founded that the erlotinib monotherapy resulted in 2-month survival advantage in comparison to best supportive care in cancer patients having chemotherapy-refractory NSCLC in the advanced stages. Erlotinib monotherapy gave a RR of about 9% while placebo gave RR below 1% [2, 6].

Nodaway TKIs used both as a first-line therapy in advanced stages of NSCLC as well as second-line therapy and also as third-line therapy for EGFR mutation-positive cancer [Table 1].

Use of EGFR Tkis as a First-Line Therapy For NSCLC

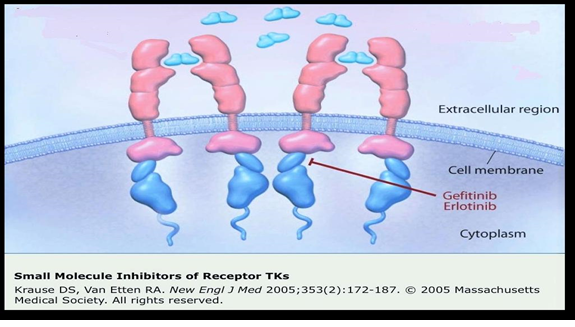

Gefitinib has been found effective as a first-line treatment in patients having EGFR-mutated NSCLC in advanced stages [8] [Figure 2].

Figure 2. Site of action of 1st Generation TKI

In a study on patients having active EGFR mutations, the tumor samples of the patients were checked retrospectively for EGFR mutations as these mutations functioned as an important biomarker to know about the working of EGFR TKIs. Researchers found that tumor RRs were about 71% with gefitinib in patients having EGFR activating mutations as compared to about 41% in the chemotherapy group. Researchers found significant effect by considering the prolongation of life, i.e. 9.4 months in gefitinib treatment group as compared to 6.4 months in the other group. During the study, most of the patients, who were previously getting first-line chemotherapy, were moved to the gefitinib treatment, as the drug showed significant benefits [8] [Table 2].

Table 2. EGFR TKI in treatment NSCLC combined with chemotherapy as 1st line: phase III

| Study | No. of patients | TKI+ chemo | Type of chemotherapy | Primary end point | outcome |

| INTACT1 | 1093 Unselected (EGFR) | Gefitinib | Cisplatin/Gem. | OS | Negative 9.9 vs 10.9 months |

| INTACT 2 | 1037 Unselected (EGFR) | Gefitinib | Carboplatin/paclitaxel | OS | Negative 9.8 vs 9.9 months |

| TRIBUTE | 1079 Unselected (EGFR) | Erlotinib | Carboplatin/paclitaxel | OS | Negative Positive in nonsmoker |

| TALENT | 1172 Unselected (EGFR) | Erlotinib | Cisplatin/Gem. | OS | Negative 10.8 vs 11 |

INTACT: The Iressa NSCLC Trial Assessing Combination Treatment

TRIBUTE: Tarceva responses in conjunction with paclitaxel and carboplatin

TALENT: Tarceva Lung Cancer Investigation

Subsequent multiple trials, in which patients having EGFR mutations were considered, also showed the efficacy of EGFR TKIs as compared to standard doublet chemotherapy that was platinum-based. Randomized studies show substantially higher RRs as well as prolonged progression free survival (PFS), further showing the effectiveness of EGFR TKIs as a first-line therapy for patients having advanced stages of NSCLC with EGFR mutations [2].

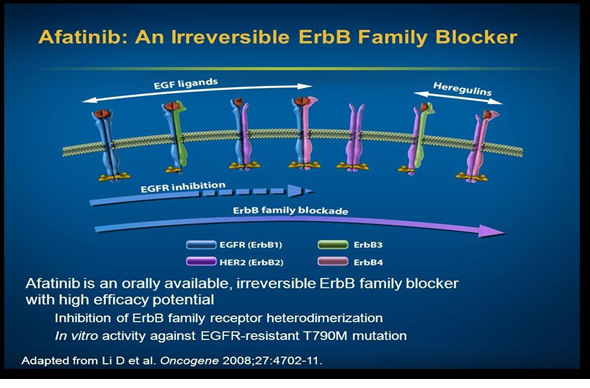

In 2013, FDA approved afatinib, a second-generation EGFR TKI. It is an irreversible TKI and is helpful as a first-line therapeutic option in patients of advanced metastatic NSCLC with EGFR mutations [6].

This drug binds with ATP attachment sites on the tyrosine kinases resulting in long lasting inhibitory effect on HER2 receptor. First-line afatinib has been found effective in improving the overall survival (OS) of patients having advanced stages of NSCLC with EGFR exon 19 deletion. Moreover, this improvement in the OS of patients was independent of race of patients. Studies consisting of a worldwide population showed that a median OS was over 30 months with the use of afatinib that is more than the median OS with chemotherapy. Although researchers found no considerable difference between the afatinib group and chemotherapy group in OS in patients having L858R mutations, but still afitinib can be a better treatment option for patients of L858R mutations [2] [Figure 3].

Figure 3. Site of action of 2nd Generation TKI

Use of EGFR Tkis as a Second-Line Therapy for NSCLC

Studies on erlotinib also show the effectiveness of the drug against wild-type EGFR NSCLC. In a study, researchers compared the effectiveness of docetaxel with erlotinib as a second-line treatment in patients having progressive wild-type EGFR NSCLC, who were initially treated with a platinum-based substances as a first-line therapeutic regimen. Researchers found that the median OS was about 8.2 months in patients using docetaxel while the median OS was about 5.4 months in patients using erlotinib. Moreover, PFS was substantially better in patients using docetaxel (i.e. 2.9 months) as compared to patients using erlotinib (i.e. 2.4 months). This showed that in spite of the efficacy of erlotinib, chemotherapy shows more effectiveness in the treatment of patients having advanced stages of wild-type EGFR NSCLC [2] [Table 3].

Table 3. EGFR TKI in NSCLC as 2nd or 3rd line (monotherapy): phase III

| Study | No. of patients | TKI+ chemo | Type of chemotherapy | Primary end point | outcome |

| ISEL | 1129 Non selected | Gefitinib | Supportive care | OS | Negative trial |

| BR.21 | 731 Non selected | Erlotinib | Supportive care | OS | Positive 6.7 vs 4.7 months |

| INTEREST | 1466 Non selected | Gefitinib | Docetaxel | OS (non-inferior) | Positive 7.6 vs 8 months |

| DELTA | 301 50 EGFR M+ |

Erlotinib | Docetaxel | PFS | Negative |

| TITAN | 424 unselected | Erlotinib | Docetaxel or pemetrexed |

OS | Negative 5.3 vs 5.5 |

| TAILOR | 222 EGFR wild |

Erlotinib | Docetaxel | OS | Negative 5.4 vs 8.2 |

ISEL trail: Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer

INTEREST: Iressa NSCLC Trial Evaluating Response and Survival Versus Taxotere

Delta: The Docetaxel and Erlotinib Lung Cancer Trial

TaILOr: Tarceva Italian Lung Optimization tRial

Combination of EGFR Tkis with Chemotherapy in the Treatment of Advanced NSCLC

Combination of EGFR TKIs with chemotherapy show poor outcomes in the treatment of advanced NSCLC. Several randomized studies show that the platinum-based regimen along with EGFR TKI has no or reduced benefits as compared to chemotherapy alone, thereby requiring further studies [9].

Studies have also been done on finding the negative effects of EGFR TKIs on chemotherapy, and researchers are of opinion that EGFR TKIs protect G1 phase of the cell cycle from the action of chemotherapy, thereby affecting the overall action of the combination therapy. It has also been found that concurrent administration of erlotinib with M phase-specific taxane results in decreased levels and a prolonged shorter apoptosis duration. In another study, it has been found that patients having wild-type EGFR tumors may show elevated rates of progressive disease as well as inferior survival on receiving combination of erlotinib with chemotherapy as compared to chemotherapy alone. The similar outcomes were reported for patients having activating EGFR mutations. On the other hand, some studies on Asian population have shown better median PFS in case of combining chemotherapy with erlotinib as compared to chemotherapy alone [2].

Resistance to Tkis

Researchers have found that tumor having exon 20 insertions show insensitivity to EGFR TKIs. However, this problem has been found in about 4% of the cases of NSCLC. Approximately 20% of the cases of NSCLC show primary resistance caused by alteration in the KRAS signaling protein, which is commonly found in former as well as current smokers. Some other mutations that can result in primary resistance to TKIs include MEK, PTEN, and ALK-fusion [10].

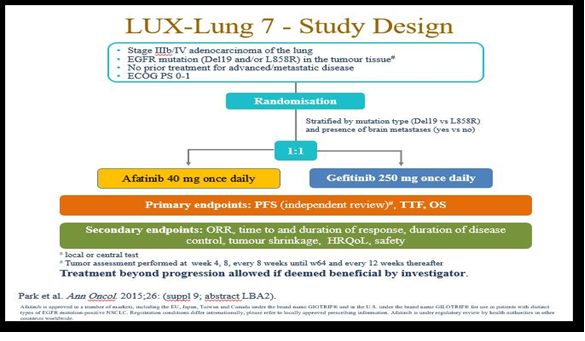

Resistances can also develop in patients having advanced EGFR mutation–positive NSCLC getting gefitinib or erlotinib as a treatment strategy. Disease progression can appear after nearly one year of therapy with any of these drugs. Most commonly found acquired resistance is due to mutation in T790M in which alteration occurs in exon 20 resulting in the replacement of methionine with threonine at the position 790. The 790M residue could disturb the attachment capacity of the TKIs with the ATP binding site. The EGFR exon 20 T790M mutations may result in up to 65% of cases of acquired resistance to TKIs [2, 10] [Figure 4].

Figure 4. LUX-Lung 7 study

Amplification of MET is also found to be an important mechanism behind the development of acquired resistance. Studies show that MET amplification may occur in about 10% of cases. Some other types of acquired resistance, which are in need of further studies, are caused by transformations to SCLC, 3CA mutation, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and stimulation of insulin-like growth-factor receptor pathway [10].

Management of the condition with acquired resistance to Tkis

The resistant is either primary, secondary (usually involves exon 20 (T790M), or tertiary (C797S mutation). Other mechanisms including: (1) amplification of c-met 5-20%, (2) amplification of her-2 in 12%, (3) mutation in BRAF 1 %,( 4) transformation to small cell lung ca in 3-14%.Resistance occurs usually with median of 9 – 13 months and commonly due to T790M mutation.

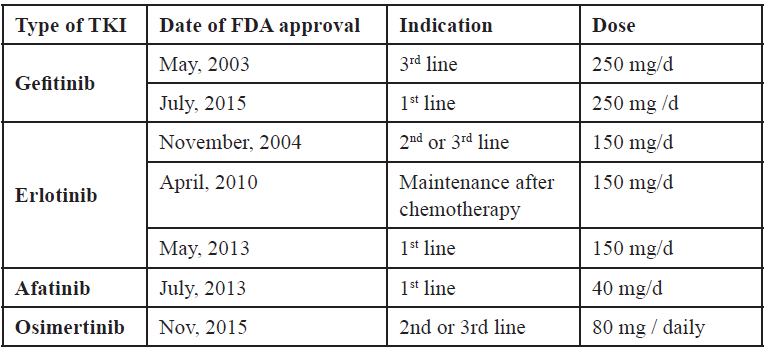

On November 13, 2015, the U. S. Food and Drug Administration granted accelerated approval to osimertinib once daily tablets, for the treatment of patients with metastatic epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) T790M mutation-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), as detected by an FDA-approved test, who have progressed on or after EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy [Table 4].

Table 4. Approval of different EGFR TKI

The approval was based on two multicenter, single-arm, open-label clinical trials in patients with metastatic EGFR T790M mutation-positive NSCLC who had progressed on prior systemic therapy, including an EGFR TKI (Study 1 and 2). All patients were required to have EGFR T790M mutation-positive NSCLC as detected by the cobas® EGFR mutation test and received osimertinib 80 mg once daily. The major efficacy outcome measure was objective response rate (ORR) according to RECIST v1.1 as evaluated by a Blinded Independent Central Review (BICR). Duration of response (DOR) was an additional outcome measure.

It has been found that doublet chemotherapy, which is platinum-based, can be a standard choice for treatment of patients of advanced stages of NSCLC, who are EGFR TKI-resistant. On the other hand, when there is metastasis of the cancer to the brain, treatment of choice is radiotherapy [2].

Concluding Remarks and Future Directions

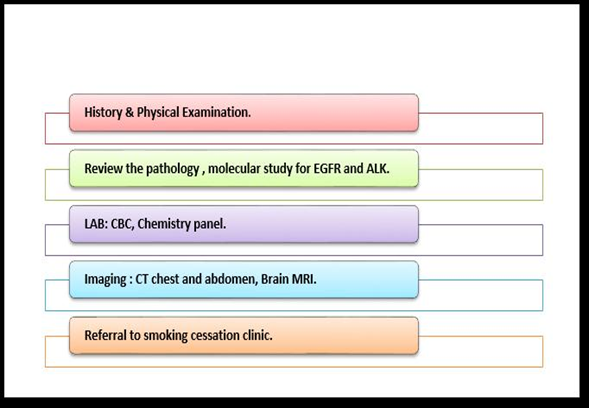

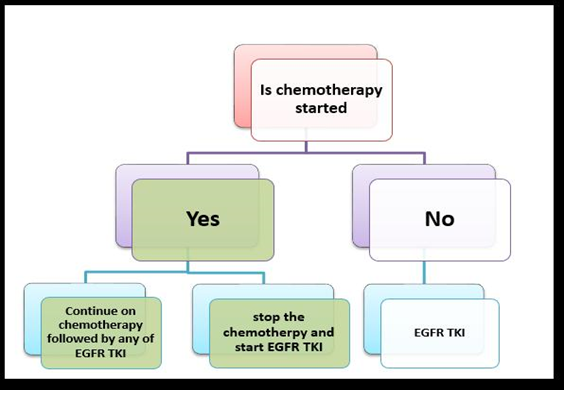

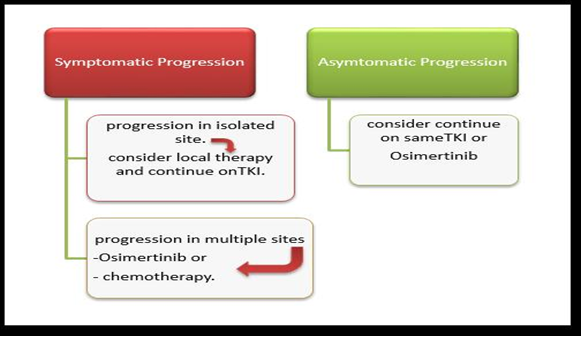

In the last few years, EGFR TKIs have been found to be among the most helpful treatment options for advanced NSCLC. Those substances were studied after the discovery of EGFR mutation, which is an important determinant of NSCLC. Moreover, the study of mutations helps the scientists to work on personalized medicine [Figures 5,6,7].

Figure 5. work up for advance NSCLC (adenocarcinoma)

Figure 6. Treatment algorithm of metastatic NSCLC (adenocarcinoma) with sensitizing EGFR mutation

Figure 7. Treatment of metastatic NSCLC progressed on EGFR TKI

Finally, we can conclude that; in the era of molecular study and personalized therapy, TKIs nowadays are able to fight with the disease more effectively. However, further studies are required in reducing the resistance of the cancer against TKIs.

Furthermore, optimization of the combination therapy is required, so that patients would be either fully cured or live longer because of the better treatment.

References

- Holland JC, Breitbart W S, Jacobsen PB, Loscalzo MJ, Butow PN, et al. (2015) Psycho-Oncology: Oxford University Press.

- Ogunleye F, Ibrahim M, Stender M, Kalemkerian G, Jaiyesimi I (2015) Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. The American Journal of Hematology/Oncology 11: 16-25.

- Taylor JM, Cohen S, Mitchell WM (1970) Epidermal growth factor: high and low molecular weight forms.Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 67: 164-171. [crossref]

- Lappano R, De Marco P, De Francesco EM, Chimento A, Pezzi V, et al. (2013) Cross-talk between GPER and growth factor signaling. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 137: 50-56. [crossref]

- Lee VH, Tin VP, Choy TS, Lam KO, Choi CW, et al. (2013) Association of exon 19 and 21 EGFR mutation patterns with treatment outcome after first-line tyrosine kinase inhibitor in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer.J Thorac Oncol 8: 1148-1155. [crossref]

- Reungwetwattana T, Dy GK2 (2013) Targeted therapies in development for non-small cell lung cancer.J Carcinog 12: 22. [crossref]

- Carneiro JG, Couto PG2, Bastos-Rodrigues L2, Bicalho MA3, Vidigal PV4, et al. (2014) Spectrum of somatic EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, PTEN mutations and TTF-1 expression in Brazilian lung cancer patients. Genet Res (Camb) 96: e002. [crossref]

- Maemondo M, Minegishi Y, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, Harada M, et al. (2012) First-line gefitinib in patients aged 75 or older with advanced non-small cell lung cancer harboring epidermal growth factor receptor mutations: NEJ 003 study. J Thorac Oncol 7: 1417-1422. [crossref]

- Cufer T, Ovcaricek T, O’Brien M E (2013) Systemic therapy of advanced non-small cell lung cancer: major-developments of the last 5-years. European journal of cancer 49: 1216-1225.

- Gainor JF, Shaw AT (2013) Emerging paradigms in the development of resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors in lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 31: 3987-3996. [crossref]

![Figure 1: Representation of the domains contained in LSD1 and LSD2[3, 6, 15]. A) Structural representation of LSD2 B) Structural representation of LSD1](http://researchopenworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/CST-2016-107-Figure1.png)