DOI: 10.31038/CST.2016113

Abstract

Objective: Fear of recurrence is a phenomenon associated with breast cancer survivorship that has been shown to cause pervasive and prominent distress, and poorer overall quality of life. Determining the factors that predict fear of recurrence is important for understanding its consequences on breast cancer survivors.

Design: This study examined whether certain demographic and medical factors influence and predict a fear of recurrence. The factors included time since diagnosis, age at diagnosis, the stage of breast cancer, and the number and average age of children.

Main outcome measures: Fear of recurrence was measured using the Concerns About Recurrence Scale. Over 3000 participants were recruited online with a final sample of 1116 breast cancer survivors.

Results: Five multiple regression models were performed to explore whether particular demographic and medical variables significantly predicted overall fears and worries associated with role, death, womanhood, and health. All five regression models were significant and analyses revealed commonalities underlying certain fears.

Conclusions: The study identified characteristics of women who may be at greater risk for chronic psychological distress and would benefit from ongoing supportive care.

Key words

breast cancer; fear of recurrence; demographics; children; time since diagnosis; age at diagnosis;

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most frequently diagnosed diseases; currently it is estimated that 1 in 9 women in Canada will be diagnosed with breast cancer and that 1 in 29 women will succumb to the disease [1]. With the exception of non-melanoma skin cancers, breast cancer is the second leading cause of death from cancer in Canadian women [1]. Fortunately, due to improvements in screening programs and treatments, death rates in women have decreased considerably since the mid-1980s [2,3]. The survival rate of breast cancer patients is now estimated to be 88% [1] and if diagnosed in an early localized stage, 98% [3]. The increase in breast cancer survivorship rates raises concerns for the quality of life experienced by the survivors. Quality of life in relation to breast cancer survivors refers to their physical, psychological, and social well-being in terms of their health after treatment [4].

Survivorship can be defined as corresponding to the period either following completion of active treatments – surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, or hormonal therapy [5] or immediately following the diagnosis [6]. For our purposes, breast cancer survivorship is defined as the time since diagnosis until death [6]. Additionally, while the term “survivor” can refer to the diagnosed individual as well as individuals providing care, in this study, we are reserving the use of “survivors” to individuals diagnosed with breast cancer, and “caregivers” will be used to refer to individuals who are providing care and support to an individual diagnosed with breast cancer.

A breast cancer diagnosis is a lifelong burden. The diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer are universally viewed as stressful and life-threatening experiences [7]. Moreover, there are long-term pervasive effects and residual symptoms, such as fatigue, neuropathy, and pain, even after successful treatment [5,8]. Other challenges that breast cancer survivors have to endure include the adjustment to life after treatment, having sufficient access to health services and support, and living with the fear of cancer recurrence.

Paradoxically, even though support is often needed more during the adjustment period, it is also often during this period that services provided by health care professionals are greatly reduced [5,9]. Breast cancer survivors move from very frequent to infrequent visits, resulting in increased levels of stress due to apprehension and health-related concerns [5,9]. Indeed, past studies have shown that the stress associated with breast cancer survivorship is an important factor to consider in evaluating survivors’ quality of life following treatment [5]. In fact, it has been reported that survivors have higher emotional distress and lower physical and psychological quality of life [7]. Although social support is often reported in the literature as a determinant of emotional well-being in breast cancer survivors, there is no extensive literature investigating the facets of social support that affect quality of life. According to Fong et al. [9], it is the quality of social support, rather than the quantity, that predicts emotional well-being.

Based on a sample of 157 female breast cancer survivors, Fong et al. [9] assessed their availability to social support and emotional well-being (i.e., depression symptoms, stress, negative and positive affect) at baseline (3 to 6 months post-treatment) and after one year (15 to 18 months post-treatment). They reported that quantity of social support significantly declined over the year, and it was associated with increased depression symptoms and stress. Social support quality generally remained stable, but for participants with declining quality of social support, they found that survivors experienced increased depression symptoms, stress, and negative affect. However, when modeled together, it was found that only change in social support significantly predicted change in depression, stress, and negative affect. In their study, the quality of social support explained an additional 4 to 6% of variance in the emotional well-being outcomes.

Aside from the availability of social support as a determinant of well-being and quality of life, a pervasive dread for survivors is the fear of cancer recurrence. Fear of recurrence is defined as the “fear or worry that cancer will return or progress in the same organ or in another part of the body” [6]. Fear of recurrence can be an intrusive and debilitating stressor for breast cancer survivors, potentially inducing high levels of stress due to the uncertainty of whether there will be a cancer recurrence or metastasis [6]. Previous studies report that approximately 33% to 56% of survivors, regardless of stage of breast cancer diagnosis, have moderate to high risk fears, which are associated with lower quality of life and psychological distress [6,7,10,11].

These fears primarily affect the survivors’ emotional and mental states resulting in debilitating stress and worry. Sometimes the fears are so overwhelming that the survivor has difficulty performing daily and social activities causing impairment that is disproportionate to the actual risk of recurrence [12]. Needless to say, fear of recurrence is a common phenomenon for a diagnosis of any type of cancer. Recently, Wanat et al. [13] conducted a meta-ethnography of 17 qualitative studies published between 1996 and 2014, on patients’ experience with recurrence. The studies included patients from a range of cancer types, with breast and ovarian cancers being the most common. After synthesizing the studies, Wanat et al. [13] identified six constructs that encompassed patients’ experience with recurrence.

The first identified construct was experiencing emotional turmoil following diagnosis, that is, the emotional impact of the diagnosis such as shock, fear, anger, devastation, and hopelessness. Wanat et al. [13] reported that 15 of the 17 studies found that the awareness of the possibility of recurrence did not reduce the emotional impact. The second identified construct was experiencing otherness, which primarily referred to the social impacts that a recurrence had on the patients’ existing relationships (e.g., sharing feelings and emotional and physical suffering with others, managing social lives). Next, it was found that seeking support in the health care system was found to be an important part of patients’ experience. This refers to the relationship between the patient and health care professionals and the access (and understanding) of medical information. The last three identified constructs were adjusting to a new prognosis and uncertain future, finding strategies to deal with recurrence, and facing mortality and pertained to balancing worries of disease progression and possibility of death with hope, regaining control over the cancer, taking responsibility for one’s health, and preserving emotional well-being. Wanat et al. [13] reported that common steps towards preservation of emotional well-being involved stopping activities that induced stress such as employment, and adopting activities that restored emotional balance such as connecting with nature.

In an effort to further understand the pervasiveness that fear of recurrence may have on breast cancer survivors, Bloom, Stewart, Chang, & Banks [14] interviewed 185 breast cancer survivors at two time points (time of diagnosis and again five years later when they were cancer free) to assess their quality of life in four domains: physical, psychological, social, and spiritual. The authors reported a significant decrease in worry about the future. Survivors who did not experience a recurrence or metastasis improved in their physical and mental well-being and 92% of the survivors rated their health as good or excellent after the five-year period.

Later research also corroborated the finding that longer time since diagnosis, although it cannot extinguish the fears and worries, could reduce the extent of fears and worries. In a study conducted by Kornblith et al. [15], younger survivors from 18 to 55 years old, scored significantly worse than survivors 65 years old or more) on a range of quality of life measures, including fear of recurrence. It was reasoned that younger survivors experience more distress due to the responsibilities that they may have as primary caretakers for younger children [15]. Parenting children while coping with breast cancer has been shown to cause lower well-being in breast cancer survivors [16] and young mothers especially, experience greater fears of having a recurrence. In an earlier study, we reported that breast cancer survivors under the age of 35 displayed greater levels of fear of recurrence in all domains [10]. Results suggested that being a mother was associated with greater fear of cancer recurrence, but the age of children (i.e., under or over the age of 18) did not impact the magnitude of fear.

Koch et al. [12] reported similar findings in their examination of fear of recurrence in long-term breast cancer survivors, that is, five or more years since diagnosis. Additionally, they showed that fear of recurrence appeared to be independent of cancer stage. However, most studies on fear of recurrence typically do not report whether the participant’s stage of diagnosis affected her level of fear towards a possible recurrence or metastasis, or whether the fear experienced depends on age at or time since diagnosis.

Recently, Cohee et al. [17] tested the theory that social constraints, that is avoidance of the person or discussion, minimizing concerns, and being critical or expressing discomfort negatively impact cognitive processing, which would ultimately affect overall quality of life and increase distress and negative affect. Based on a sample of 222 young, long-term breast cancer survivors (3 to 8 years post-diagnosis and 45 years of age or younger at time of diagnosis) and their partners, Cohee et al. [17] reported that cognitive processing, as defined by intrusive thoughts and cognitive avoidance, mediated the relationship between social constraints and fear of recurrence. They also examined a number of demographic variables, finding ‘current age’ in the mediation analysis for breast cancer survivors and ‘years of education’ for partners to be relevant predictors. In conclusion, Cohee et al. [17] reported that the demographic variables were not significant predictors for fear of recurrence in the respective mediation models.

While time since diagnosis has generally been reported to be associated with decreased fear and worry, there have been mixed findings in regards to the impact that age of breast cancer diagnosis may have on fear of recurrence. Some studies suggest that all survivors may experience fear of recurrence independently of age, while others, including our group, report that women diagnosed at a younger age tend to have higher psychological distress and lower quality of life which may lead to a greater magnitude of fear of recurrence [10,14,15,18]. Taken together, these findings demonstrate how common fear of recurrence is in survivors and its elusive nature.

Although fear of recurrence is a well-studied topic in the cancer survivorship literature and some correlates have been identified, we have yet to distinguish characteristics that may help identify survivors who are at high-risk for developing a significant fear of recurrence. Understanding this relationship is important because it will help inform whether sufficient services are provided to individuals to alleviate their fears, stress, and concerns. There has been some insight on potential interventions, however. Bower et al. [19] found that mindfulness meditation is efficacious in the short-term in reducing stress, behavioural symptoms, and proinflammatory signalling in premenopausal breast cancer survivors. However, as with other studies in the literature, the longevity of the effects is unclear [19], and more research is needed to prolong intervention effects and identify the parameters and characteristics and interventions appropriate for different cancer populations and age groups. The present study will aim to provide more insight on the determinants of vulnerable groups that would benefit from psychosocial interventions and allow us to develop interventions that guarantee the highest possible well-being and quality of life of breast cancer survivors.

Current Study

Our group has shown that breast cancer survivors who were diagnosed at a young age, had a recent diagnosis, or identified as a mother have a heightened fear of recurrence [10,14–16]. While we have not seen a relationship between the age of children and the extent of fear of recurrence [10], the influence of the number of children in this context has not been explored. As mentioned above, being a mother has been demonstrated to be an important factor in the fear of recurrence due to increased responsibilities such as raising a child; therefore, it is relevant to explore the impact that the number of children at the time of diagnosis may have. Moreover, to our knowledge, the impact of medical variables such as time since diagnosis and stage of diagnosis have not been explored in conjunction with these variables on fear of recurrence in breast cancer survivors.

To address this gap, the current study examined the following demographic and medical variables as possible predictors of fear of recurrence: Time since diagnosis, age at diagnosis, stage of breast cancer, number of offspring, and average age of offspring, as well as their interactions. Based on the literature, we expected a greater fear of recurrence for breast cancer survivors who were diagnosed at a young age, had more than one child at the time of diagnosis, and were diagnosed with a later stage of breast cancer.

Measures

Demographic and medical questionnaires

The demographic questions included age, ethnicity, country of origin, occupation, income, education, number, and age of each child. The medical characteristics were age at diagnosis, time since diagnosis, stage of breast cancer, and type of treatment received. The demographics variables for this study were chosen based on previous literature.

Concerns About Recurrence Scale (CARS [6])

This multidimensional scale was designed to determine to what extent fear of recurrence impacts breast cancer survivors. It also investigates what the sources of those fears may be based on a 30-item questionnaire. The CARS includes five subscales; the first subscale Overall Fear of recurrence is addressed with four questions pertaining to the frequency, potential for upset, consistency, and intensity of fears. These four questions are rated on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (I don’t think about it at all) to 6 (I think about it all the time).

The other four subscales were designed to measure the source of the fears. This section contains 26 questions with a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all), to 1 (a little), to 2 (moderately), to 3 (a lot) and to 4 (extremely). These four sub-scales include Health Worries, Womanhood Worries, Role Worries, and Death Worries. Health worries address the concerns about future treatment, emotional upset, and physical health. Womanhood worries address body image issues, femininity, sexuality, and identity. Role worries address roles and responsibilities in home life and within the work place. Death worries address the fear that breast cancer could lead to death. Higher scores on all scales indicate greater fears. This scale has demonstrated high validity and internal reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.87.

Procedure

Participants completed an on-line survey that was administered through iSurvey.ca. The consent form, which outlined the purpose of the data collection, was completed on-line. The survey took approximately 45 minutes to complete and participants could return to the survey at a later date if not completed. Various other questionnaires were included as part of the survey but for the purposes of this study, only scores associated with the Concerns About Recurrence Scale were analyzed in relation to the demographic and medical variables. This study was approved by the University of Ottawa Research Ethics Board (#04-09-04).

Data Analyses

Multiple regression analyses were used to develop models that predict individual worries (health, womanhood, role, death) and overall fears based on the physical and medical demographic variables – time in years since diagnosis, age, age at diagnosis, stage of breast cancer, number of offspring, and average or median age of offspring. Prior to analysis, the statistical assumptions were reviewed for violations. Participant scores were deemed to be outliers if their associated Mahalanobis Distance was greater than the critical value of χ2 = 16.81 at p < .01

Due to multicollinearity, “age” was removed from the model. The five remaining variables met all assumptions and were entered in one step since we had no reason to expect that any particular variable would have a more or less impact on the results. All analyses were performed using SPSS, V22.

Results

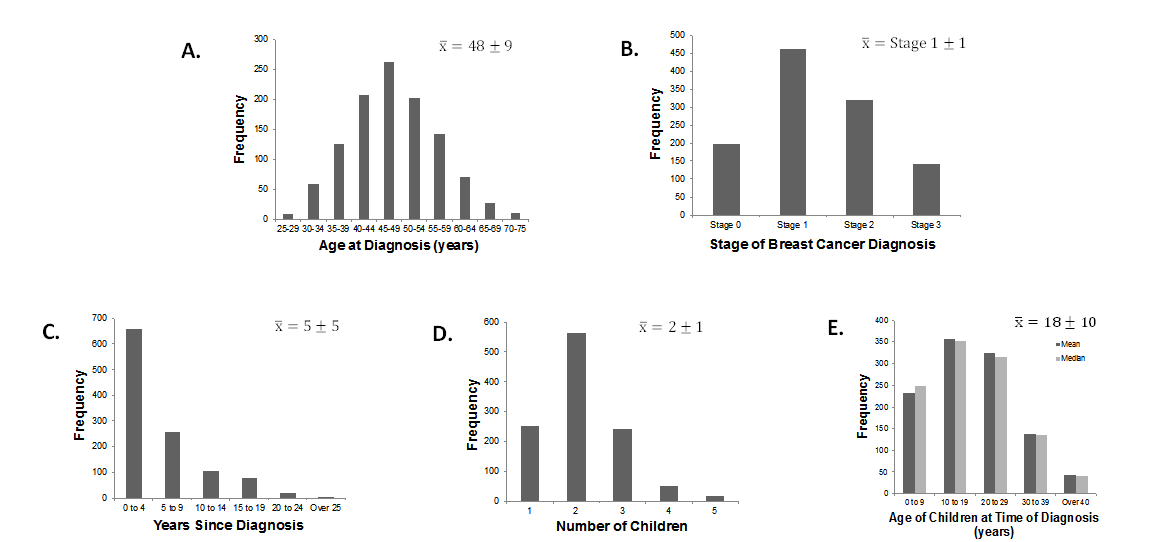

Figure 1, plots A to E, show the frequency distributions associated with each demographic variable. The age of participants at diagnosis (Figure 1A) ranged between 25 to 75 years (M = 48 ± 9 years SD). The participants were diagnosed with stage 0 to stage 3 breast cancer (Figure 1B) with the majority identified with stage 1; stage 4 was excluded due to metastases to other sites. Years since diagnosis ranged from 1 to 28 years (Figure 1C). They reported having between one and five children at the time of diagnosis (Figure 1D) with average age ranging from 1 to 50 years old (Median and Mean age = 18 ± 10 years SD, Figure 1E).

Figure 1. Frequency distributions of the medical (A, B) and demographic variables (C, D, E).

Table 1 provides the overall results of each model, in order of level of significance and variance accounted for. The overall fears subscale produced the greatest strength, explaining 14% of the variance associated with fear of recurrence, followed by Role Worries, Womanhood Worries, Death Worries, and Health Worries; overall the combination of the four Worries was associated with roughly 4% of the variance. See Table 2 for a summary of the zero-order correlations.

Table 1. Overall model summary of multiple regression analyses on CARS subscales.

| Subscale | F | P | R2 adj |

| Overall Fears | 35.77 | <.001 | .135 |

| Role Worries | 4.66 | <.001 | .016 |

| Womanhood Worries | 3.28 | .006 | .010 |

| Death Worries | 2.62 | .023 | .007 |

| Health Worries | 2.29 | .044 | .006 |

Table 2. Summary of the zero-order correlations on CARS subscales.

| r | ||||||

| Stage of Diagnosis | Age of

Diagnosis |

Number of Children at Time of Diagnosis | Average Age of Children at Diagnosis | Years since Diagnosis | Years x Age Interaction | |

| Overall Fears | -.085 to .141

(p < .001) |

-.191

(p < .001) |

.004

(p = .448) |

-.190

(p < .001) |

-.253

(p < .001) |

.091

(p = .001) |

| Health Worries | .025

(p – .200) |

-.086

(p = .002) |

-.009

(p = .388) |

-.070

(p = .009) |

-.031

(p = .153) |

Interaction not tested |

| Death Worries | .046

(p = .063) |

-.088

(p = .002) |

.024

(p = .209) |

-.070

(p = .010) |

-.026

(p = .193) |

Interaction not tested |

| Role Worries | .038

(p = .101) |

-.118

(p < .001) |

-.001

(p = .484) |

-.099

(p < .001) |

-.056

(p = .032) |

.047

(p = .057) |

| Womanhood worries | .005

(p = .440) |

-.082

(p = .003) |

-.036

(p = .116) |

-.072

(p = .008) |

-.064

(p = .016) |

.014

(p = .322) |

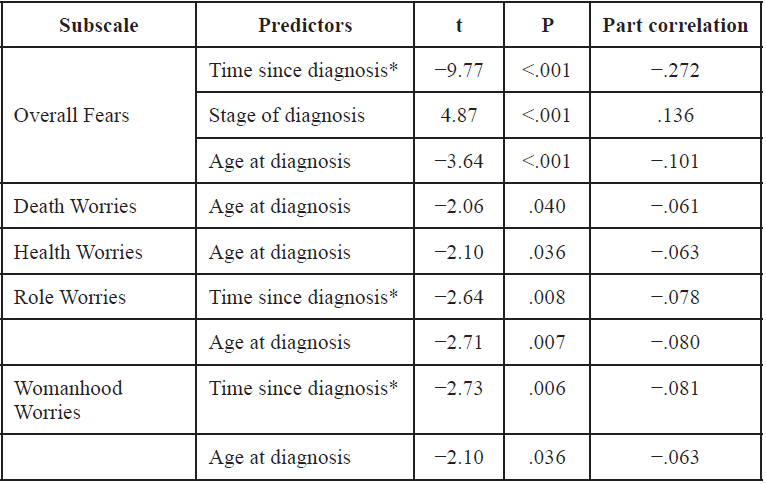

Table 3 lists the demographic and/or medical characteristics that significantly predicted specific Worries. Neither the number nor the average/median age of offspring contributed significantly to any of the models, suggesting that fear of recurrence is independent of these factors.

Worries related to course of illness

Age at diagnosis had a negative relationship with all Worries and uniquely contributed to Death and Health Worries (see Table 3), suggesting that younger age at diagnosis is associated with more fears and worries specific to the course of illness.

Identity-related fears

Age at diagnosis and Time since diagnosis were found to be common negative predictors for identity-related fears, that is, Role and Womanhood Worries, indicating that more recent diagnoses and younger survivors experience greater fear of recurrence and exhibit greater worries in these specific domains.

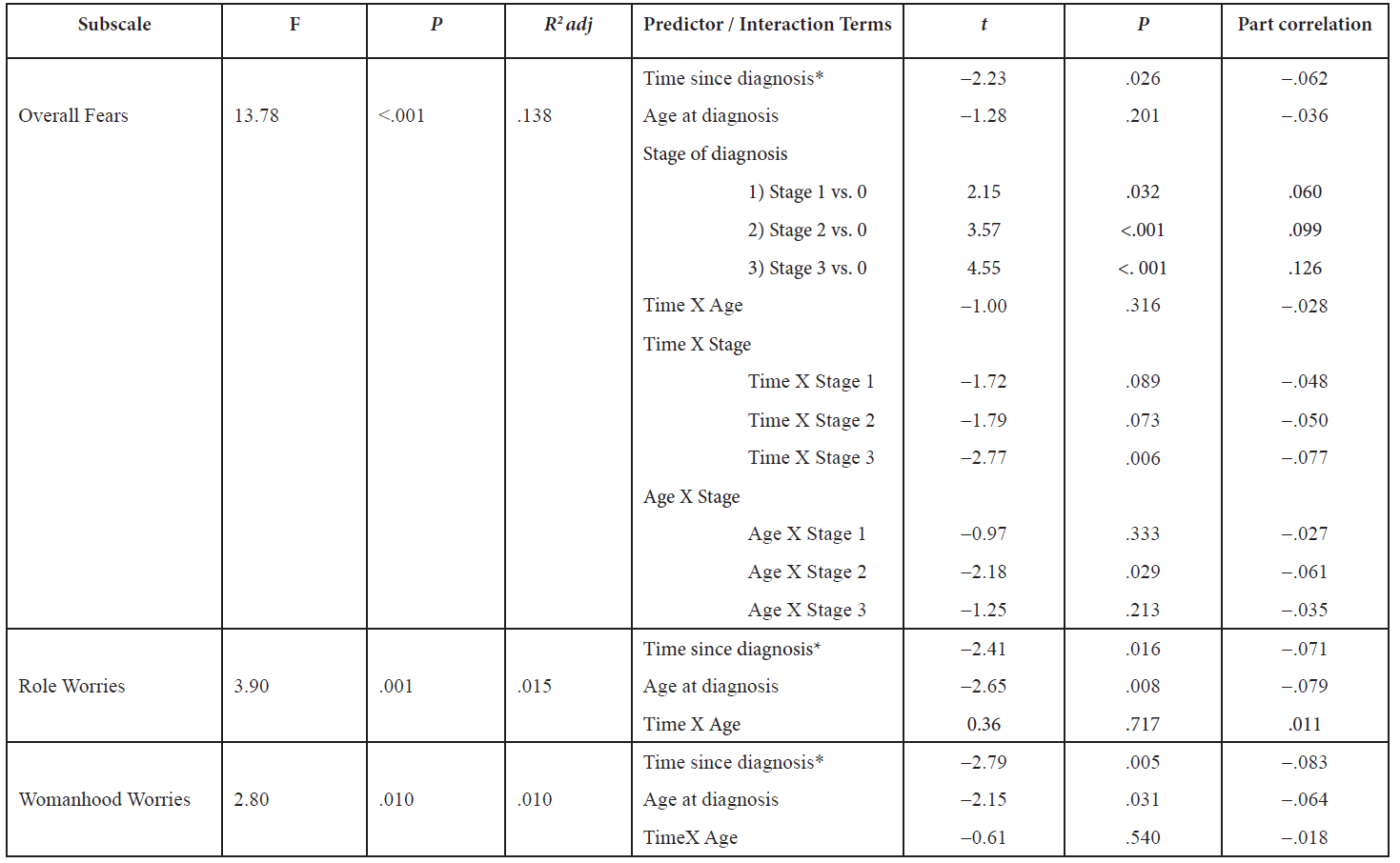

As a follow-up test, we entered the individual predictors associated with Role Worries and Womanhood Worries as well as their interaction term; as shown in Table 4, these analyses did not reveal significant interactions and the individual predictors maintained their significance.

Table 3. Significant predictors determined by the multiple regression analyses.

* How long it has been since diagnosis of breast cancer in years

Overall fears

Overall fears measure the extent to which women worry about recurrence based on its frequency, intensity, consistency, and potential for upset. The analyses revealed that Time since diagnosis, age at diagnosis, and stage of breast cancer (see Table 4) were significant predictors. Stage of diagnosis contributed uniquely and positively to Overall Fears – higher stage equalled more fear. The results suggest that the more recent the diagnosis, the higher the fear. Moreover, individuals diagnosed at a younger age identified as having more overall fears. Lastly, stage of breast cancer indicated a positive relationship showing that a higher stage of breast cancer was associated with greater fear.

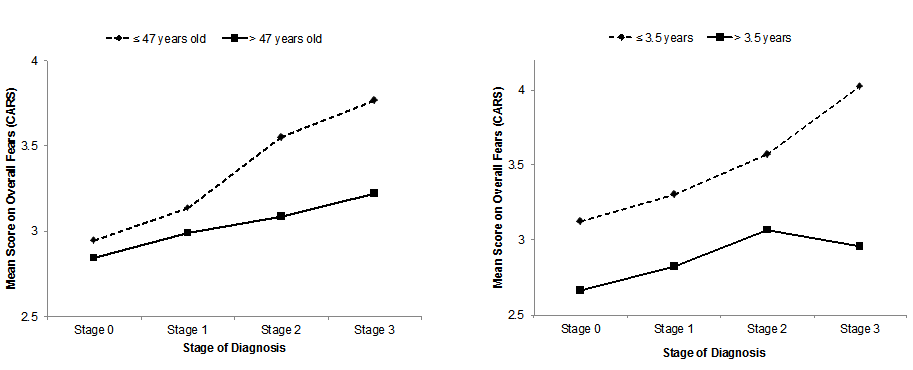

To follow up, we centered the two of the three significant predictors, time since diagnosis and age at diagnosis, and created dummy variables to represent each individual stage in the third significant predictor: stage. With the newly created variables, we created two-way interaction terms to enter in a simple multiple regression model with the original predictors. When accounting for the interactions, only two of the original three predictors remained significant (see Table 4). We also found an interaction between Time since diagnosis and Stage 3 (t = -2.77, p = .006) and Age at diagnosis and Stage 2 (t = -2.18, p = .029). For an illustration of the interactions, see Figure 2.

Figure 2. Schematic illustration of the interactions.

Left: Age of diagnosis (median-split) and Stage. Right: Time since diagnosis (median-split) and Stage.

The literature suggests that fear of recurrence is independent of Stage (e.g., Koch et al., 2014); however, our results suggest that Stage is a significant predictor of Overall fears. To explore the relationship between Stage and the remaining four predictors, we conducted a hierarchical regression analysis, with Stage entered before our set of predictors. Change statistics indicated that Stage accounted for 3.8% (p < .001) and our four predictors accounted for 10.1% of the variance (p < .001) in our model.

Table 4. Regression results after accounting for interaction terms for Overall Fears, Role Worries, and Womanhood Worries

* How long it lias been since diagnosis of breast cancer in years

Discussion

The main objective of this study was to determine whether particular demographic and medical variables predict fear of recurrence in a large sample of breast cancer survivors. In particular, we examined the relations between a selection of demographic and medical variables to fear of recurrence in a sample of first-time breast cancer survivors with children at the time of diagnosis. We hypothesized that the five demographic and medical variables entered into the regression analysis would have varying influences on fear of recurrence and would all be significant predictors of fear and worry in each subscale. While all the models were significant for each subscale, we also found common predictors for certain fears – suggesting that these were related to each other and belong to a broader class of fears.

In our earlier studies (see [10] and [16]), motherhood was a significant predictor of fear of recurrence in breast cancer survivors. For example, Lebel et al. [10] reported that young mothers had a higher fear of recurrence than older mothers or women without children; later Arès et al. [16] found that mothers, more than non-mothers, experienced greater fears both in the short and long term. Arès et al. [16] also explored determinates of higher fear of recurrence in young mothers but did not identify any of significance. Our current study differs from these on a few essential points.

Although we did not intend to examine the effects of motherhood on fear of recurrence per se, based on the literature, we included two unexplored predictors that were related to motherhood that may influence fear of recurrence: Age of children at the time of diagnosis and number of children at the time of diagnosis. In the current study we also employed more stringent inclusion criteria. Notably, all the participants included in the current study were first-time breast cancer survivors without a prior diagnosis of cancer, with children at the time of the diagnosis. Our earlier findings did suggest that ‘age’ was an important factor to consider but was not explored thoroughly. In the current study, age at diagnosis was a common predictor for all subscales, demonstrating that the individual’s age at the time of diagnosis significantly affects fear of recurrence in all domains. This outcome is in agreement with the hypothesis that fears and worries are higher depending on the age of the survivor at diagnosis, that is, younger survivors being associated with greater fears.

In this study the examination of breast cancer survivors who self-identified as mothers more closely, with more stringent inclusion criteria, revealed some nuances. Specifically, age and number of children at the time of diagnosis did not influence the magnitude of fear that the participants experienced in regards to a cancer recurrence. Our results revealed that having children, or more broadly, ‘motherhood’, did not appear to have an impact on the level of fear experienced in first-time breast cancer survivors. Unlike our previous studies which used a younger cut-off and segregated age into categories, our analyses were based on the full range of ages, from 25 to 75 years old. Therefore, the importance and relationship of age and number of children at the time of diagnosis could unfold differently and reflect a finer tuning of the data. Building on our previous work, although mothers may experience higher levels of fear of recurrence [10], the results of the current study exemplifies the complexity of fear of recurrence and breast cancer survivorship, and the importance to consider additional facets and determinants such as cancer history, when exploring this construct.

Time since diagnosis was shown to influence fear of recurrence in specific life domains such as roles and womanhood. That is, participants with a recent diagnosis scored, on average, higher than other participants in terms of their distress towards a potential recurrence. This is not surprising as more recent survivors would have greater concerns, especially in the domains of their roles and responsibilities associated with being a woman. However, studies have shown that such fears and worries tend to dissipate over time [12,14] and supportive care, at least, in the short run, would be very useful.

Stage of breast cancer at diagnosis influenced the extent to which survivors worried about a possible recurrence. Although previous studies have suggested that fear of recurrence is independent of breast cancer stage [7], our data suggest otherwise and indicate that survivors with higher stages of breast cancer are associated with a heightened amount of distress. Higher stages of breast cancer are more threatening to the life of the survivor and have more negative symptoms [1]. This may evoke more uncertainties and worries in breast cancer survivors in regards to the possibility of a recurrence.

The characteristics that did not appear to be associated with greater uncertainties and worries in breast cancer survivors were the number and average or median age of children at diagnosis. In the study conducted by Kornblith et al., [15], more than 50% of the younger breast cancer survivors had children living with them (n = 61), while this was true for only 9% of the older survivors (n = 67). While this study suggests that higher fear and worry in younger mothers could be due to the responsibility of having younger children and being a primary care taker, we did not see this relationship in the current study, using a much larger sample. This outcome suggests that the number of children does not have an important impact on the fears of a mother.

These results are consistent however, with the idea that fears are present in all mothers due to the possibility of leaving their children regardless of their age [10,20] or number of children. In our study, participants had at least one child and at most five children. We reasoned that the number of children would be associated with more distress; however, our findings suggest that it is not the number or age of children that is an important generator of distress in breast cancer survivors who are mothers. In the study conducted by Adams et al. [20] they found that young mothers have the hard task of balancing priorities such as their health and treatment needs as well as the physical and emotional demands of children and family. In addition, communicating the illness to their children was shown to be a difficult task [20]. This may explain the increase in fear and worry in young mothers who are survivors as there is an additional stress to balance with their diagnoses when they have to consider their children in the process [20].

Limitations

One major limitation of this study is the use of the demographic predictor variable, average age of children at the time of diagnosis. This variable represents the average age of all children at the time of diagnosis, which means some meaningful data may be lost or misinterpreted. The impact of having children who are dependent (i.e., infants, toddlers, children, and adolescents) and independent (i.e., young and older adults,) are important factors to consider; however, using an average number may encompass both categories of children. Additionally, we examined and compared the range of ages of the children and the median age of children, to the average age of all children; however, the effects were identical regardless of the metric used. It may be useful in the future to rank the average age of the children based on the standard deviations of the mean of the combined ages. Future studies should also consider examining additional parameters, such as marital status of the mothers, health of children, and availability of caretakers, to fully explore and understand the relationship between motherhood and fear of recurrence.

Another limitation of this study is that this sample only represents English-speaking mothers from North America; in order to generalize this to a larger population a more representative and diverse sample should be used. This study was conducted through an online survey, and while this was earlier thought to limit the demographic to those who had internet access, there are now data showing that this is no longer an issue and online surveys actually reach a larger global group of participants [21]. Using survey methods as a tool for data collection has been shown to be a very reliable and valid method [21].

There are other demographic variables that may influence fear of recurrence that were not considered in this study. These variables include education, marital status, income, social economic status, and social support. Nonetheless, the most significant model found explained 14% of the variance in our data, which may provide some explanation of a causal mechanism between breast cancer characteristics and fear of recurrence.

Implications and Future Directions

While this study is consistent with the literature with respect to predictors of fear of recurrence, it has also demonstrated that while mothers (especially young mothers) have greater fear of recurrence, the number of children and age of children at diagnosis does not affect the amount of fear or worry of the survivor. This highlights instead the need for supportive care programs for breast cancer survivors aimed at protecting those who are at greater risk (for instance young mothers) for chronic psychological distress associated with fear of recurrence. These results have confirmed that younger survivors especially need more priority in this context and indicates the importance of sensitivity towards the individual characteristics of the patient in order to detect whether they are experiencing high emotional distress and the need for early interventions to assist them in managing their fears and worries.

In the current study, we explored several specific interactions in the regression models and our results suggest that there may be a relationship between particular stages of breast cancer diagnosis and certain medical variables. But, it is important to note that although these interactions were significant, they accounted for less than 1% of the variance (see part correlation on Table 4). The majority of our participants were diagnosed with Stage 1 breast cancer, we suggest that future studies explore whether fear differs as a function of stage, treatment, and number of recurrences in more advanced breast cancer diagnoses; and to determine if it is a moderator depending on the age of the survivor at diagnosis, demographics of the survivor’s children (e.g., sex, health, age), and the availability of a caregiver to provide care to the survivor as well as her children at the time of diagnosis. This would allow insight into the detailed levels of the variables tested that are important influences in fear of recurrence. Since fear of recurrence is so prevalent, determining the timing and the different ways to cope with fear of recurrence effectively is imperative to help alleviate fears in breast cancer survivors.

Acknowledgements and Funding Information

We would like to thank Avon Army of Women and Canadian Breast Cancer Research Alliance for their support of this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Canadian Cancer Society. Canadian cancer statistics 2015: Predictions of the future burden of cancer in Canada 2015.

- Canadian Cancer Society. Breast cancer statistics 2015.

- National Breast Cancer Foundation. Breast Cancer Facts.

- Ferrell BR, Grant M, Funk B, Garcia N, Otis-Green S, et al. (1996) Quality of life in breast cancer. Cancer Pract 4: 331-340. [crossref]

- Ganz PA, Kwan L, Stanton AL, Krupnick JL, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, et al. (2004) Quality of life at the end of primary treatment of breast cancer: first results from the moving beyond cancer randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 96:376–87.

- Vickberg SM (2003) The Concerns About Recurrence Scale (CARS): a systematic measure of women’s fears about the possibility of breast cancer recurrence. Ann Behav Med 25:16–24.

- Waldrop D, O’Connor T, Trabold N (2011) “Waiting for the Other Shoe to Drop:” Distress and Coping During and After Treatment for Breast Cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol 29:450–73.

- Ganz PA, Kwan L, Stanton AL, Bower JE, Belin TR (2011) Physical and Psychosocial Recovery in the Year After Primary Treatment of Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol 29:1101–9.

- Fong AJ, Scarapicchia TMF, McDonough MH, Wrosch C, Sabiston CM (2016) Changes in social support predict emotional well-being in breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology.

- Lebel S, Beattie S, Arès I, Bielajew C (2013) Young and worried: Age and fear of recurrence in breast cancer survivors. Health Psychol 32: 695-705. [crossref]

- van den Beuken-van Everdingen M, Peters ML, Rijke J de, Schouten HC, Kleef M van, ET AL. (2008) Concerns of former breast cancer patients about disease recurrence: a validation and prevalence study. Psychooncology 17:1137–45.

- Koch L, Bertram H, Eberle A, Holleczek B, Schmid-Höpfner S, Waldmann A, et al. (2014) Fear of recurrence in long-term breast cancer survivors—still an issue. Results on prevalence, determinants, and the association with quality of life and depression from the Cancer Survivorship—a multi-regional population-based study. Psychooncology 23:547–54.

- Wanat M, Boulton M, Watson E (2016) Patients’ experience with cancer recurrence: a meta-ethnography. Psychooncology 25:242–52.

- Bloom JR, Stewart SL, Chang S, Banks PJ (2004) Then and now: quality of life of young breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology 13:147–60.

- Kornblith AB, Powell M, Regan MM, Bennett S, Krasner C, Moy B, et al. (2007) Long-term psychosocial adjustment of older vs younger survivors of breast and endometrial cancer. Psychooncology 16:895–903.

- Arès I, Lebel S, Bielajew C (2014) The impact of motherhood on perceived stress, illness intrusiveness and fear of cancer recurrence in young breast cancer survivors over time. Psychol Health 29:651–70.

- Cohee AA, Adams RN, Johns SA, Von Ah D, Zoppi K, et al. (2015) Long-term fear of recurrence in young breast cancer survivors and partners. Psychooncology . [crossref]

- Ziner KW, Sledge GW, Bell CJ, Johns S, Miller KD, Champion VL (2012) Predicting fear of breast cancer recurrence and self-efficacy in survivors by age at diagnosis. Oncol Nurs Forum 39:287–95.

- Bower JE, Crosswell AD, Stanton AL, Crespi CM, Winston D, Arevalo J, et al. (2015) Mindfulness meditation for younger breast cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Cancer 121:1231–40.

- Adams E, McCann L, Armes J, Richardson A, Stark D, Watson E, et al. (2011) The experiences, needs and concerns of younger women with breast cancer: a meta-ethnography. Psychooncology 20:851–61.

- Greenlaw C, Brown-Welty S (2009) A Comparison of Web-Based and Paper-Based Survey Methods Testing Assumptions of Survey Mode and Response Cost. Eval Rev 33:464–80.