DOI: 10.31038/JCRM.2022512

Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of this clinical research is to illustrate the impact of prosody on speech and voice production. Prosody impacts speech and comprehension of content, as it incorporates the suprasegmentals involved in the production of the speaking voice (e.g., intonation, vocal intensity, speech rate, word juncture, speech rhythm, and pausing appropriately). When providing therapy to clients from foreign countries (and clients with dysphonia), it is important to address the above prosodic features to enhance vocal quality, speech rhythm, as well as articulation, as these features have an impact on listener comprehension of the message.

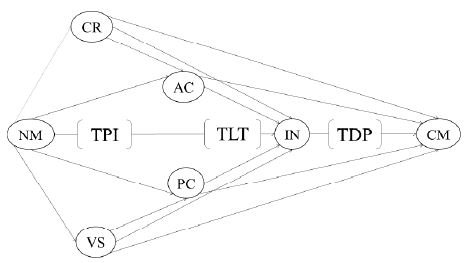

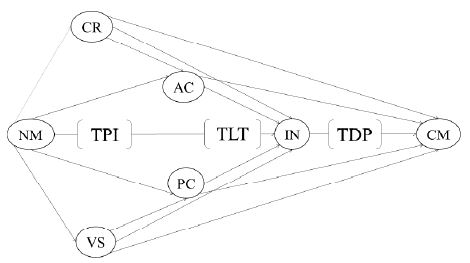

Methods: The waveforms of both groups (control and participant) will be recorded on the Multidimensional Voice Program as they read the paragraph for the purpose of comparing and analyzing the waveforms of the two groups in terms of the components of prosody. Additionally, seven raters will listen to the recordings and evaluate them in terms of the following areas: speech rhythm, intonation, intensity, stress, pitch variation, and speech rate. The raters will be given a chart with names of the suprasegmentals and circle those they find deviant or incorrect for each recording; additionally, they will rate the degree of deviance on a scale of 1-5 (with 5 being the most deviant) in terms of the suprasegmental interference with voice and intelligibility.

Results and Conclusion: The results showed that incorrect use of voice/speech production in the context of prosody negatively affected vocal production and speech intelligibility, or clear comprehension of the message, as per the raters. The raters’ evaluations were consistent with each other and reflected the aspects of the waveforms in terms of the suprasegmentals (e.g., little to no pitch, low intensity, incorrect stress, pausing inappropriately).

Keywords

Suprasegmentals-vocal intensity, Intonation, Stress, Speech rate, Speech rhythm

Introduction

Prosody incorporates the melodic and rhythmic areas of speech (e.g., intonation, stress within sentences, words/multisyllabic words, length of sounds, intensity (variation between soft and loud voice), and the sharing of brain activations, particularly in the right hemisphere auditory areas [1]. According to Wagner and Watson, prosody can be defined as “a level of linguistic representation at which the acoustic-phonetic properties of an utterance vary independently of its lexical items” (e.g., phonological rhythm, semantic relationships, predictability of the linguistic material) [2]. Prosody is associated with emotion in speech. For example, intensity, vocal pitch, rhythm, and rate of an utterance are influenced by vocal emotion, which reveals the attitude and meaning of the speaker. The authors’ results show mixed support for hemispheric lateralization of speech prosody, particularly in the temporal lobe auditory areas in comparison to the frontal lobe evaluative area. Mannell (2007) states that prosody is the study of those aspects of speech that approach a level above the individual phoneme, often including the sequences of words and phrases. Prosody may also be thought of as the grammar of language [3].

Steedman (1991) stated that prosody reflects syntax because syntax and meaning are connected in terms of prosody [4]. Another aspect of prosody concerns head movements [5]. These authors found in their study that rhythmic head motion communicates linguistic information (e.g., the head movements correlated with pitch and intensity of the speaker’s voice). In this animation study, head movements were allowed to be manipulated without changing characteristics of the visual or acoustic speech; a greater number of syllables were identified by participants when natural head motion was present compared to when head motion was eliminated or distorted. The authors’ results suggested that non-verbal movements may be important in the perception of speech. According to Paige et al. (2014), appropriate prosody during oral reading contributes to comprehension processing, along with accuracy and automaticity [6]. Wagner and Watson (2010) state that there are debates on how to characterize the acoustic-phonetic properties of pitch accent and boundaries and how they are linked to discourse, as well as syntactic and semantic structure [2]. It is not clear how prosodic structure fits into models of language production. However, the study of Munhall et al. “demonstrated an interaction between visual prosody and the identification of individual words in a set of statement sentences” [5]. There were correlations between head movements and vocal acoustics, indicating that head gestures may be a contributing factor to word processing.

Cutler et al. (1986) contend that prosodic research in the comprehension of spoken language falls into three main areas: the recognition of spoken words, the computation of syntactic structure, and the processing of structure in terms of the contribution of accentuation and de-accentuation [7]. Hahn (2004) reports evidence that accent and comprehensibility are distinct constructs but overlaps [8]. The author notes that primary stress, placed correctly, showed that listeners recalled significantly more content in comparison to when the primary stress was missing or incorrectly placed. This finding suggests the importance of suprasegmentals regarding voice production, the latter in terms of variation in pitch, intensity, and stress.

Mannell (2007) points out that prosody overlaps with emotion in speech because the acoustic features used to express prosody (e.g., pitch, rhythm, vocal intensity, and rate of utterance) are affected by emotion in the voice [3]. Additionally, further research can open a greater understanding regarding the difficulties processing emotional speech (which incorporates voice production) in populations with pathologies.

Foote and Trofimolovich noted that for non-native listeners, “segmental accuracy and fluency appeared to underlie listener” perceptions of second language speech in a reading task [9]. For native listeners, word stress, accuracy, and second language reading/listening proficiency influenced perception [9].

Wagner and Watson (2010) point out that duration has been shown to correlate with prominence in English to signal word stress as well as phrase prominence [2]. Duration also signals phrasing and indicates lexical contrasts between words. The durational lengthening at the end of prosodic constituents tends to occur when the gestures slow down [2]. Fundamental frequency can also indicate primary prominence by a higher pitch in the word, which points to the importance of voice use.

According to an article from Wikipedia, intonation has been described in different ways: the division of speech into units, highlighting certain words or syllables, and the choice of pitch (rise or fall) [10]. Stress functions as a way of making a syllable prominent and may also be related to individual words as well as sentence stress (prosodic stress). Stress is associated with pitch prominence, increased duration, increased loudness, and the acoustic quality of vowels – all a part of voice production.

Ben-David et al. determined in their research that “emotional prosody and semantics are separate but not separable channels, and it is difficult to perceive one without the other” [11]. Behrman (2014) points out that although a non-native accent is not a communication disorder, it may have a negative effect on communication [12]. This author investigated prosodic training outcomes of non-native speakers of American English with a single participant by using segmental and prosody training for accent management. The results showed improved prosody patterns as well as increased accuracy of pronunciation. Listeners could more easily understand the content secondary to the contribution of segmental and prosody training. Klopfenstein (2009) confers with Behrman (2014) regarding the importance of prosody for speech intelligibility, which incorporates voice production [12,13]. Klopfenstein (2009) notes that prosody is often marginalized and misunderstood in the field of Speech-Language Pathology [13], indicating the importance of prosody or speech intelligibility (e.g., difficulty with prosody in the speech of people who are deaf or who have neurological disorders, as these individuals may not always be able to interpret vocal and speech messages). It appears that the suprasegmentals are very relevant to address in therapy. According to Grigos & Patel (2007) [14], stress functions as a way of making a syllable prominent and may be related to individual words as well as sentence stress (prosodic stress). Stress is associated with voice (e.g., pitch prominence, increased duration, and increased loudness, which refers to the acoustic quality of vowels).

The aim of the research by Groen et al. (2018) [15], was to determine the input of decoding skills from prosody skills. Their participants were fifth grade children with age-appropriate decoding but weak comprehension skills. The children with poor comprehension scored significantly below the chronological-age controls on all prosody tasks and below younger comprehension controls on a speech rhythm task. It appeared that children with poor comprehension demonstrate a delay in the perception and production of speech prosody. Therefore, it is seen that the relationship between text reading prosody and reading comprehension is not exclusively a question of decoding, illustrating the importance of suprasegmentals.

Felps et al. (2008) tested a method that transforms foreign-accented speech to resemble its native-accented counterpart [16]. Accent is contained in prosody while formant structure and speaker identity are attributed to vocal tract length and glottal shape. The study used natural speech and concluded that both areas can be complementary.

Ben-David et al. found that “prosody and semantics are integral, and it is difficult to perceive one without the other” [11]. The influence of prosody, however, has a much greater impact on the emotional rating of speech than semantics. The authors state that knowing this information can improve communication techniques and allow a better understanding of difficulties that clients with pathologies have in processing emotional speech. Furthermore, the findings of Bruce et al. (2012) revealed that non-native accented speech has a negative impact on comprehension, even in terms of simple tasks [17]. Their conclusion is that accents, varying in both segmental and prosodic features, can interfere with successful interactions between non-native accented speakers and native listeners, particularly native listeners with aphasia.

Research by Anderson-Hsieh et al. (1992) compared the relative contributions to intelligibility in terms of prosody, segmentals, and syllable structure [18]. In researching eleven different language groups, they determined that the various components of prosody (lexical stress, intonation, relative duration of weak and strong syllables) most likely contribute to intelligibility in different ways.

According to Amano-Kusumoto and Hosom (2011) [19], intelligibility at one level cannot be compared to intelligibility at another level; for example, speech intelligibility at the phoneme level cannot be used to predict intelligibility at the sentence level. That is, word, syllable, and sentence intelligibility levels are dependent on each other, while phoneme intelligibility impacts word intelligibility. An unclear sound phoneme may be recovered from a larger context, whereas phoneme intelligibility impacts word intelligibility. In terms of sentence intelligibility, these authors found that gender does not play a role in the relationship between fundamental frequency and sentence intelligibility. These researchers discovered that the listener’s age and hearing status (impaired vs. non-impaired) affects intelligibility between conversational and clear speech. Formant transitions, temporal envelope, F1 and F2 ranges, formant bandwidth, and Voice Onset Time (VOT) are factors that can be part of prosody as they are a part of increased intelligibility. The authors also contend that in elderly people, who have temporal processing deficits and prosodic features, may have difficulty with perceiving certain aspects of speech.

Non-native English speakers must learn to understand pronunciation, stress, intonation, and vowel/consonant sounds from people in different parts of the world [20]. In a word identification task, high frequency words showed higher intelligibility than lower frequency words [21]. Anderson-Hsieh et al. (1992) and Derwing et al. (1998) concluded that suprasegmentals play a more important role than segmentals (phonemes) in the intelligibility of speech pronunciation and comprehensibility in communicative contexts, and that prosodic deviance had a greater effect on non-native language learners [18,22].

Field (2005) produced an initial first language study that showed misplacing stress in words can seriously impair speech intelligibility, implying that how the voice is used for stress affects intelligibility [23]. The author found that in two syllable words, there was no effect on intelligibility when primary stress was on the first syllable. When there was a rightward shift of stress, for example, in the word “turbine,” there was an effect on intelligibility. Overall, the statistics showed that intelligibility was decreased significantly rightward than leftward. According to Lepage and Busa (2014) [24], incorrectly stressing a word had little effect on intelligibility if stressed vowels retained their quality and unstressed vowels were reduced. The authors also found that misplaced leftward stress impairs intelligibility significantly more than misplaced rightward stress.

Bond and Small (1983) stated that native English speakers rely more on stressed syllables of words than the unstressed syllables [25]. The authors found that the participant groups responded similarly to misallocation of stress. Grosjean and Gee (1987) suggest that stressed syllables may provide a code that links to a representation of the word in the native language listener’s mind. Research by Cutler and Clifton (1984) showed that stress misplacement seems to seriously impair intelligibility for native listeners, more when it is shifted to the right [26,27]. Vowel reduction and stress misallocation, when put together, have a detrimental effect on intelligibility. In the study of Yenkimaleki and Heuvan (2018), Derwing et al. (1998) showed that training second language learners, with emphasis on word stress, incorporating voice, led to better intelligibility [22,28].

According to Field (2005) previous research has shown that suprasegmentals have a higher correlation than segmentals (speech sounds) in terms of intelligibility, which indicates the importance of using the voice properly [23]. Previous psycholinguistic studies have highlighted the importance of stressed syllables over unstressed syllables in cases of “slips of the ear.” In fact, native speakers tend to identify misplaced stress more than mispronunciation of a phoneme, which indicates that misplaced stress is more important to the intelligibility of a word than the pronunciation of a phoneme [23]. In his study, Field found that there was a larger decrease in intelligibility when there was a stress shift to an unstressed syllable that did not have a change in vowel quality [23]. Hearing a weak quality vowel in a stressed syllable may reduce intelligibility in a native listener. Stressed syllables help identify words that are already stored in the mental lexicon of a native listener and perhaps an experienced non-native listener. Decreased intelligibility may also be related to a change in vowel quality; a full quality syllable has a closer relationship to the orthographic representation of a word with which a listener is familiar. In this case, it would thus be easier for the listeners to distinguish which word was being said, even if there was a stress shift. Field found, in his study, that there was a higher decrease in intelligibility with a lexical stress shift to the right of a word than to the left. It appears that stress, which incorporates how one uses his/her voice, has a significant effect on speech intelligibility.

Lepage and Busa (2014) indicated that incorrect vowel reduction is more damaging than misplacement of word stress, and that word stress and vowel reduction should be an area of concern for those clinicians who provide voice therapy, as well as teachers of pronunciation [24]. Furthermore, according to Sapir et al. (2001) intensive voice treatment can improve voice quality, loudness, articulation, prosody, and intelligibility [29].

Intelligibility and Pausing

Studies by Tolhurst (1957), Picheny et al. (1986), Li and Loizou (2008), Smiljanic and Bradlow (2008), and Hazan and Baker (2011) show that speakers have some control over the intelligibility of their speech by adopting various speaking styles that increase listeners’ understanding [30-34]. The authors, Tolhurst (1957), Picheny et al. (1986), Li and Loizou (2008), Smiljanic and Bradlow (2008), and Hazan and Baker (2011), found that improving the suprasegmental aspects (e.g., appropriate speech rate, appropriate pausing, and alteration of intonation patterns) all increased perceiving intelligibility of conversational speech at different levels.

According to Dreher and O’Neill (1957) and Summers et al. (1988) [35,36], the Lombard speech effect (the involuntary tendency of speakers to increase their vocal effort when speaking in loud/noisy environments) has been shown to be more intelligible than speech in a quiet environment. Nevertheless, it is important to be aware of not abusing one’s voice when increasing intensity.

Prosody and Neurological Problems

Reduced prosody can be seen in neurological diseases such as Parkinson’s disease where voice and speech abnormalities occur, along with reduced prosody. Additionally, it appears that voice production is a component of speech intelligibility and working on voice production can enhance speech intelligibility. These factors impact speech intelligibility which relates to issues of social, economic, and psychological well-being [37]. Yenkimaleki and Heuvan (2018) found that prosodic feature awareness training is beneficial to both speech production and speech recognition [28].

Patel et al. (2012) found that exaggerated and redundant prosodic cue use has been seen among adults with dysarthria secondary to Cerebral Palsy (CP) [38]. It is possible that these speakers heighten their prosodic contrasts to increase intelligibility. Although intensity range and fundamental frequency were similar across groups, the children with dysarthria spoke more slowly, and their fundamental frequency (F0) was more variable than the group without dysarthria. Furthermore, there was a decrease in intelligibility when these children increased F0 and duration further than a normal range (or the range usually used). The authors suggested that there could be interventions working on prosody (which is a component of voice production) to improve intelligibility of children with dysarthria. The authors noted that it was difficult to state the effectiveness of therapy because of the diversity of prosodic problems. Overall, however, there were improvements in acoustic and/or perceptual ratings of prosody, even though the participants were not within normal limits. Some important information was gleaned from this study such as the importance of addressing the slow rate of speech which increases severity. The authors also suggest that enhancing word-level prosodic features may increase intelligibility, and that children with CP may benefit from targeted intervention regarding prosody early in the treatment phase. Fundamental frequency can also indicate primary prominence by a higher pitch in the word. Kochanski et al. (2005) [39], however, state that loudness is the best acoustic correlate.

Need for the Study

Greater research is needed to determine the role and contribution of the suprasegmemtals (e.g., intonation, vocal intensity, stress, speech rate and rhythm) in voice production, prosody, and speech intelligibility, not only for clients with foreign accents. Although correct voice production is addressed in voice therapy, the suprasegmentals can enhance the production of vocal output and have a positive effect on voice. Work on the suprasegmentals related to prosody for individuals with foreign accents and individuals who would benefit from this therapy can increase speech intelligibility and voice production.

Questions Asked

- In the present study, which suprasegmentals (e.g., intonation, pausing appropriately, vocal intensity) can most negatively affect speech/voice on a scale of 1-5, with 5 being the highest)?

- Which aspect/s of prosody were least affected in terms of accent?

- Is there a difference in ratings among the three groups of raters, that is, the professors, the graduate students, and the undergraduate students, all of whom are in the department of Speech Communication Arts and Sciences?

Method

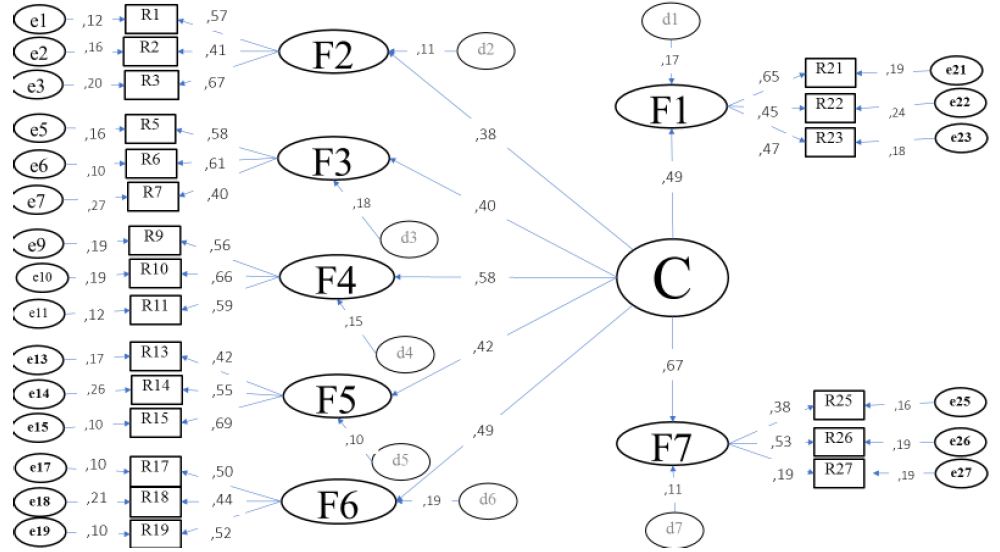

The following is a small-end clinical study on Prosody: The suprasegmentals of speech were evaluated by both instrumental and raters’ assessments. Instrumental evaluation of the participants’ waveforms of males and females from different countries (e.g., China, Italy, and Hungary) read a paragraph aloud, and their speech and voices were evaluated on the Multidimensional Voice Program instrument, reflected in the waveforms. Ten individuals (males and females in the control group) read the same paragraph aloud for comparison with the accent group. No hearing problems were reported or observed in either the participant or control group. People with hearing loss tend to raise the fundamental frequency of their voices to enhance their perception to increase identification of their own voice Akil et al. (2017) [40]; this action did not occur with either the participants or the control group. Participant raters also listened to the recorded tapes of both groups (participant and control) and evaluated the prosody of each person in each group. The prosody of each tape was evaluated along seven suprasegmental dimensions for both the participant group and the control group: (1) pausing appropriately at linguistic junctures; (2) intonation (pitch variation); (3) speech rate (too fast or too slow); (4) intensity (too loud or too soft); (5) connected speech (smooth or choppy); (6) word-sentence stress; (7) within normal limits. Therefore, each individual rater contributed 84 ratings in total. For the accent group, the raters circled the suprasegmental in each person’s tape recording in which they found a problem (e.g., lack of intonation, choppy speech, and monotone voice) as noted above. The raters assessed the degree of negative impact that the suprasegmental had on voice and speech on a scale of 1-5, with 5 being the most negative. Any suprasegmental not circled indicated that this aspect of prosody was appropriate (e.g., vocal intensity).

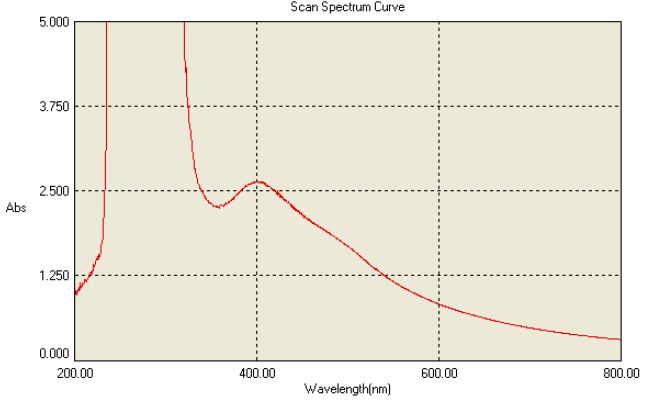

Instrumental Results on the Multidimensional Voice Program

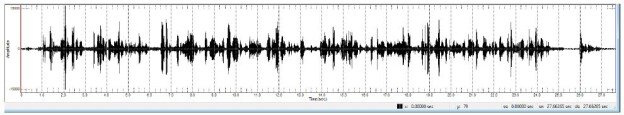

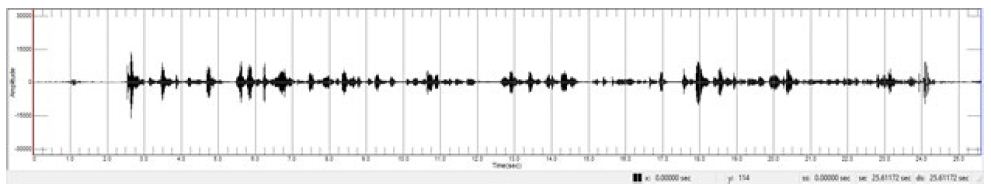

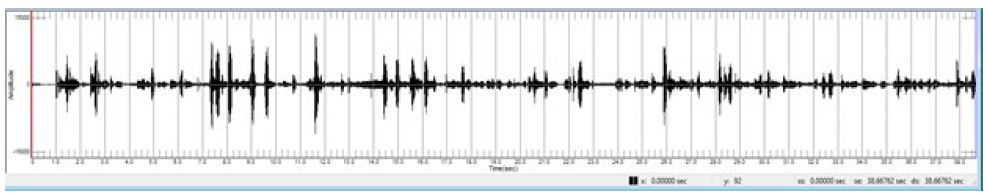

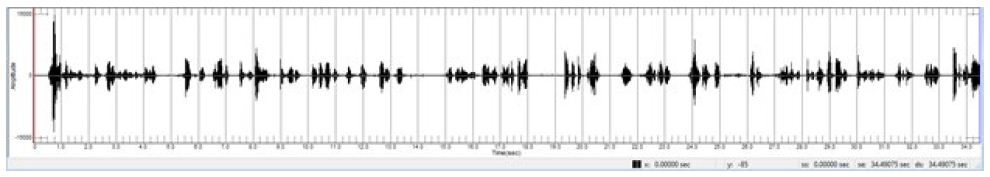

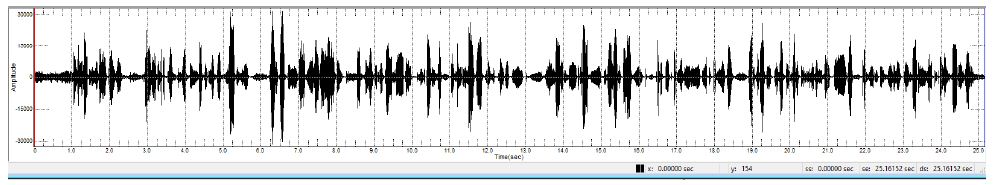

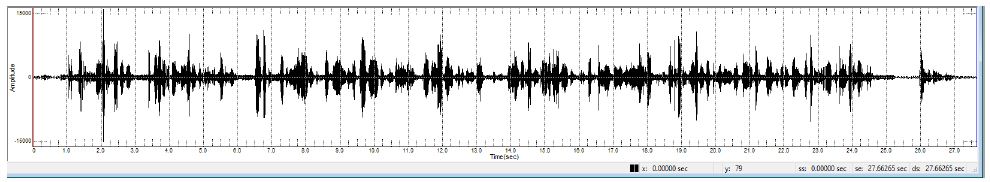

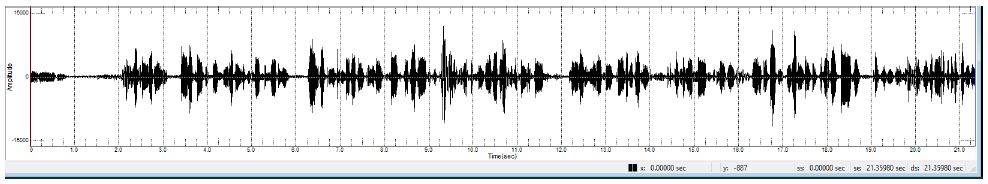

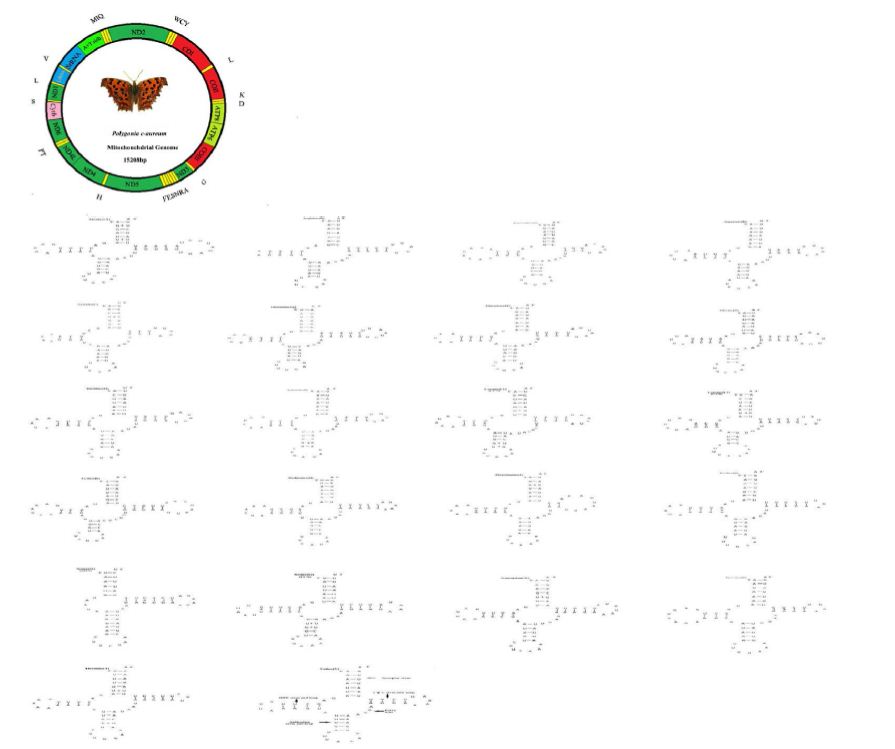

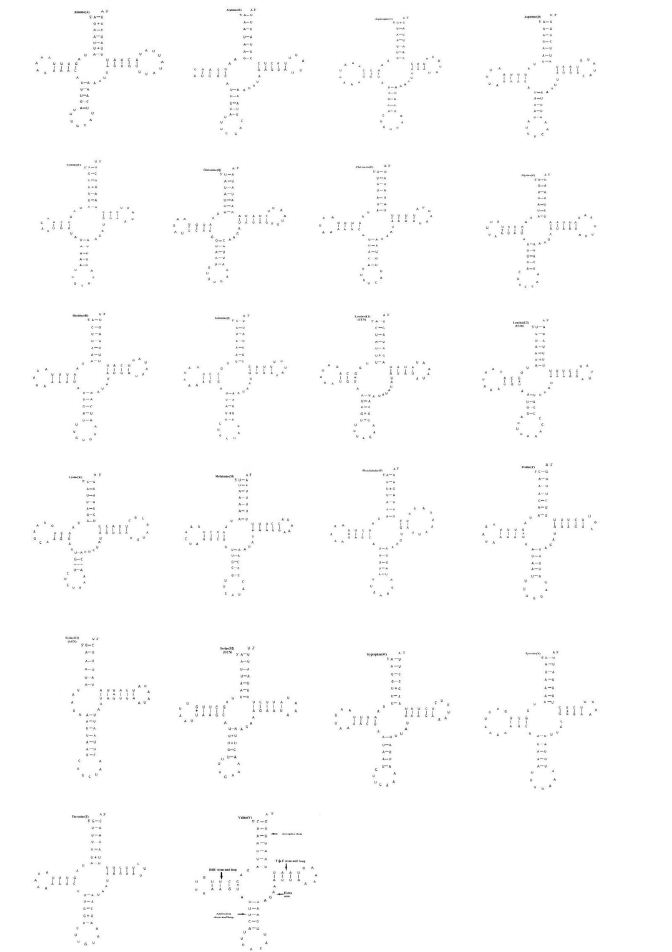

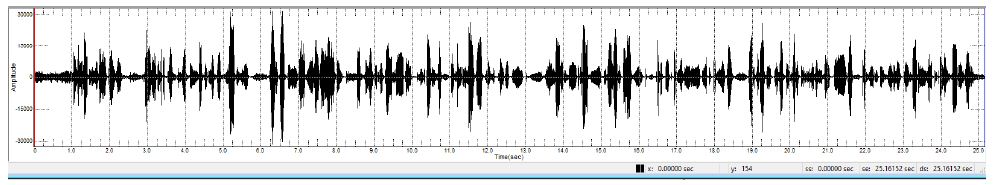

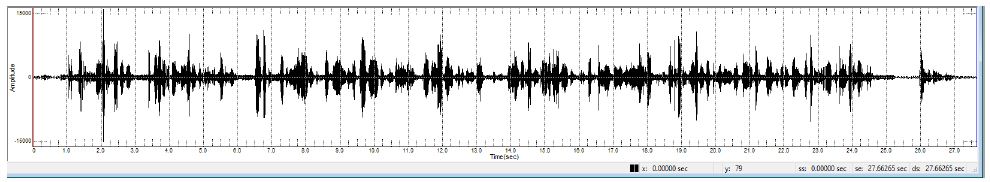

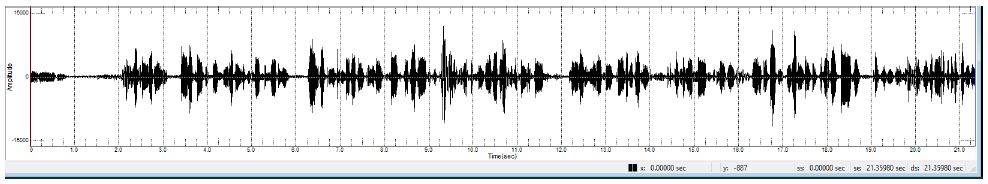

The waveforms in this study indicated a difference in prosody between the control group and foreign participants, which needs to be addressed when working with foreign accents. As noted, the 21 participant raters listened to the audiotapes of the paragraph readings by the individuals from different countries as well as those from the control group. The results of the data from the Multidimensional Voice Program show the difference in waveforms between the accent group and control group in terms of prosody. See Figures 1-3 for examples of prosody related to foreign accent: pitch variation, intensity, and pausing. The results of the data from the Multidimensional Voice Program were in accord with the raters’ prosody evaluation (pitch variation, intensity, and pausing appropriately).

In comparison to the control group, the above examples of the foreign accent group show reduced vocal intensity, limited pitch variation, and inappropriate pausing (choppy speech) in comparison to the control group whose waveforms indicate suitable pitch variation, pausing appropriately, sufficient intensity (Figures 4-6) which follow.

As noted above, the examples of the foreign accent group (Figures 1-3) show reduced vocal intensity, limited pitch variation, and inappropriate pausing, in comparison to the control group (Figures 4-6), where these areas of prosody indicate sufficient intensity, and both appropriate pausing and pitch variation. In sum, the figures relating to the two groups show prosody and voice differences between the control group and the accent group as observed in the waveforms.

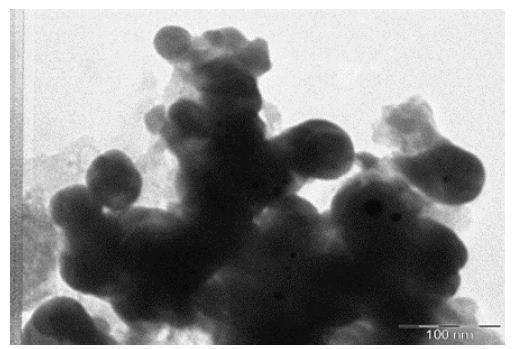

Figure 1: Foreign (African) Accent

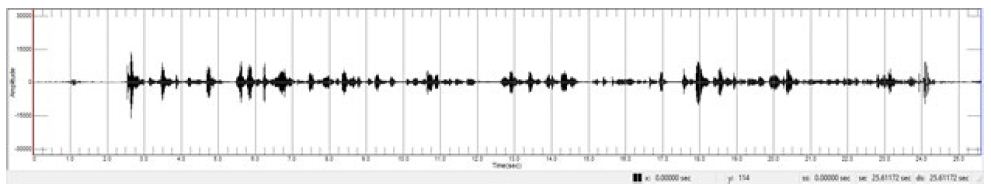

Figure 2: Foreign (Japanese) Accent

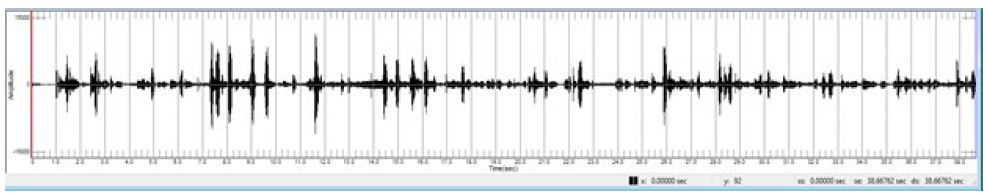

Figure 3: Foreign (Urdu) Accent

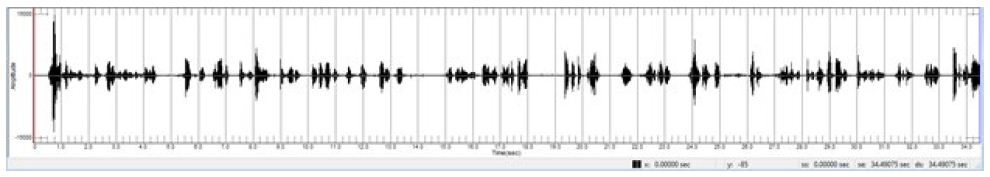

Figure 4: Control Group

Figure 5: Control Group

Figure 6: Control Group

Participant Raters’ Results

Seven raters from each of the following groups–professors, graduate, and undergraduate speech pathology students compared and listened to the recordings of both the participants and the control group. The raters evaluated the prosody of the two groups on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being within normal limits. They found the following characteristics in the accent group: excessive pausing, inappropriate pausing, monotone voice or limited pitch variation, choppy speech, prolonged speech, slow rate, too loud or too soft. These results appeared to confirm the data seen on the waveforms. According to the raters, the suprasegmentals which most negatively affected speech/voice production were the following from the highest to lowest degree of frequency.

Choppy Speech: Frequency: 198 (67.3%)

Pitch Variation (monotone): Frequency: 184 (62.6%)

Excessive Pausing Frequency: 146 (49.7%)-related to choppy speech

Speech Rate (too slow): Frequency: 135 (45.9%)

The characteristics found in the control group were all within regular limits, compared to the accent group. The waveforms on the instrument appeared aligned with the raters’ evaluations of the participants.

Questions Answered:

- In the present study, which suprasegmentals had the most negative effect on prosody on a scale of 1-5, with 5 being the most difficult?

The participants had the most difficulty pausing appropriately and using pitch variation, resulting in choppy speech, a monotone voice, and speaking too slowly.

- Is there a difference in ratings among the three groups of raters, that is, the professors, the graduate students, and the undergraduate students, all of whom are in the department of Speech Communication Arts and Sciences?

The three rater groups evaluated all the participants (both control and accent groups) and were consistent in their ratings regarding the above characteristics for the accent group: choppy speech production, monotone voice, speaking too slowly, and inappropriate pausing. The control group, however, demonstrated appropriate pausing, pitch variation, speech rate (prosody was consistently rated within normal limits).

- Which aspects of prosody were the least affected by accent, according to the raters?

The least affected aspects were loudness (intensity) and word stress, that is, for this group of participants.

Discussion

This study was undertaken to bring attention to problems with prosody and how the suprasegmentals of speech and voice (e.g., intonation, vocal intensity, rate and rhythm, stress) not used appropriately can have a negative effect on prosody and thus listener comprehension. Viewing the waveforms of the participants in comparison to the control group’s waveforms, it is obvious that the participants exhibit almost a flat waveform with very little pitch variation, which is how their speech was perceived by the raters who listened to their recordings. These suprasegmentals are important for listener comprehension of the content and to impart the value of prosody to the clients in terms of listener comprehension. The above findings highlight the importance of addressing suprasegmentals during voice and speech therapy for clients who have difficulty with prosody to increase the intelligibility of their speech.

It is possible that the suprasegmentals may not always be addressed in therapy, even though a negative effect on voice and speech may occur if not used correctly. Not addressing prosody, when necessary, can reduce progress in terms of obtaining the most positive outcome. Individuals with voice problems must learn how to use their voices without phonotrauma and work on the suprasegmentals as well (if needed) which can enhance voice, listener comprehension of the message, and meaning. Working on the suprasegmentals can also have a positive effect on speech production. That is, correcting one prosodic feature can have a positive effect on another feature. For example, reducing choppiness may increase pitch variation and improve the client’s use of voice, as well as listener comprehension. Excessively slow rate, lack of pitch variation, low vocal intensity, incorrect stress, can reduce the meaning of the information heard and deprive the vocal folds from being appropriately engaged (e.g., to change the pitch for meaning). Field (2005) [23], for example, wrote an initial first language study that showed misplacing stress (which involves how one uses the voice) in words can seriously impair speech intelligibility. As noted, Ben-David et al. (2016) found that prosody and semantics are integral as one has an influence on the other [11]. The authors note, however, that prosody has a greater impact on the emotional rating of speech in comparison to semantics, and voice often incorporates emotion.

As noted, studies by Tolhurst (1957), Picheny et al. (1986), Li and Loizou (2008), Smiljanic and Bradlow (2008), and Hazan and Baker (2011) showed that speakers demonstrate some control over the intelligibility of their speech by implementing various speaking styles to increase listeners’ understanding. The authors determined that improving the suprasegmental features (e.g., appropriate speech rate, more appropriate pausing, pitch variation, appropriate vocal intensity, and alteration of intonation patterns, without any vocal abuse) improved conversational speech perception. It is the present principal investigator’s experience that intelligibility and voice improve when incorporating appropriate prosody (suprasegmentals) during therapy.

Articulation, of course, is important in terms of both voice production and articulation, which can support voice. Inappropriate prosody, however, may reduce intelligibility even more than just producing a speech sound incorrectly. For example, if a person has a few speech sound substitutions (e.g., l/r, d/th, i/I (seat for sit)), the content may be understood. From the present research, however, when a person does not, for instance, connect words in sentences, speaks with a monotone voice, has significantly reduced vocal intensity, listeners may have greater difficulty understanding that person than one with a few related articulation errors. Additionally, when working with one suprasegmental, another suprasegmental can become incorporated in the therapy. For example, improving pitch variation and connected speech can lead to improvements in intensity, appropriate speech rate, and appropriate pausing; additionally, precise articulation can take effort off the larynx. Improvements in these aspects can be a part of voice therapy and very motivating to the client as voice is enhanced. Prosody also gives the individual an avenue to express him or herself more meaningfully. Grigos and Patel note that “there is evidence to suggest that children master the suprasegmental aspects of speech before segmental features” indicating that prosodic control appears concurrently with language development and has an influence on the production of early infant vocalizations and words [14].

Most of the speakers featured in the clips/tapes of the present study were chosen because each had detectable accents and prosodic difficulties. There were, however, two clips of people from other countries who were judged to have regular prosody and vocal production. These latter clips/tapes indicate that one can have an accent and maintain appropriate prosody and suprasegmentals to which all the raters in this study agreed. These clips are not shown in the article, but they are similar to the waveforms of the control group, indicating appropriate prosody.

All of the participants in the clips/tapes of the present study were chosen because each had detectable accents with prosodic difficulties. Two clips of participants from foreign countries, however, not shown in this article, were judged by the raters to have regular prosody and vocal production in line with those of the control group. These two clips indicate that one can have an accent and maintain or learn to speak with appropriate prosody and suprasegmentals.

The following authors summarize the importance of prosody and its suprasegmentals on the impact on voice: McCabe and Altman (2017) stress that prosody in speech/voice production is essential as it provides contextual meaning in speech in terms of the variation of frequency, rate, and tone [41]. Prosody gives layers of meaning beyond the word. It communicates emotional and social elements that may not always be expressed through words. Voice therapy can offer individuals with prosodic difficulty methods to improve their prosody and thus their communication. Furthermore, according to Schirmer (2010) [42], a speaker’s prosody contributes to “shaping a word’s affective representation in memory” and may produce attitude changes in listeners that can have a lasting effect on listener behavior.

Nakatani and Schaffer (1978) found that stress and rhythm in terms of prosody affect speech naturalness as well as intelligibility, or the ease with which speech can be understood [43]. The findings of Patel et al. (2011) suggest that fundamental frequency and intensity are integrated to sustain the contrast between stressed and unstressed words [44,45].

Limitations

This study was limited because the raters evaluated the accented speech of individuals (the participants from different countries) who all read the same paragraph aloud, the latter to obtain consistency, in terms of the content, for comparison. Additionally, the study incorporated a small number of individuals with accents (participants).

Conclusion

The findings of this research revealed that voice production, which involves prosody related to the physiological components of voice and speech (e.g., intonation, pausing appropriately, breath support, articulation), should be part of voice therapy since prosody has a significant effect on voice production and listener comprehension. A recording device needs to be incorporated in the sessions, so that the clients can hear their improvements.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Dr. Howard Spivak, statistician, for his very helpful input into this article; I also thank the Brooklyn College professors and students who participated in this study by rating the accent tape recordings. I appreciate Dr. Alla Chavarga’s assistance in summarizing and discussing the results. I am especially appreciative of the contributions and assistance of Deema Farraj, Brooklyn College student, for her excellent assistance on the computer, editing the manuscript, and insightful input into this study.

References

- Belyk M, Brown S (2014) Perception of affective and linguistic prosody: An ALE meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 9: 1395-1403. [crossref]

- Wagner M, Watson DG (2010) Experimental and theoretical advances in prosody: A review. Lang Cogn Process 25: 905-945. [crossref]

- Mannel R (2007) Introduction to Prosody theories and models. Macquarie University.

- Steedman M (1991) Structure and intonation. Lang 67: 260-296.

- Munhall KG, Jones JA, Callan DE, Kuratate T, Vatikiotis-Bateson E (2004) Visual prosody and speech intelligibility: Head movement improves auditory speech perception. Psychol Sci 15: 133-137. [crossref]

- Paige DD, Rasinski T, Magpuri-Lavell T, et al. (2014) Interpreting the relationships among prosody, automaticity, accuracy, and silent reading comprehension in secondary students. J Lit Res 46: 123-156.

- Cutler A (1986) Forbear is a homophone: Lexical prosody does not constrain lexical access. Lang Speech 29: 201-220.

- Hahn LD (2004) Primary stress and intelligibility: Research to motivate the teaching of suprasegmentals. TESOL Quart 38: 201-223.

- Trofimovich PA (2016) Multidimensional scaling study of native and non-native listeners’ perception of second language speech. Percept Mot Skills 122: 470-489. [crossref]

- Wikimedia Foundation. (2021, December 15). Prosody (linguistics). Wikipedia. Retrieved December 15, 2021, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prosody_(linguistics)

- Ben-David, BM, van Lieshou P (2016) Prosody and semantics are separate but not separable channels in the perception of emotional speech. Test for rating of emotions in speech. J Speech Lang Hear Res 59: 72-89. [crossref]

- Behrman A (2014) Segmental and prosodic approaches to accent management. Amer J Speech Lang Pathol 23: 546-561. [crossref]

- Klopfenstein M (2009) Interaction between prosody and intelligibility. Intl J Speech Lang Pathol 11: 325-331. [crossref]

- Grigos MI, Patel R (2007) Articular movement associated with the development of prosodic control in children. J Speech Lang Hear Res 50: 119-130. [crossref]

- Groen MA, Veenendaal NJ, Verhoeven L (2018) The role of prosody in reading comprehension: evidence from poor comprehenders. J Res in Read 42: 37-57.

- Felps D, Bortfeld H, Gutierrez-Osuna R (2008) Prosodic and segmental factors in foreign-accent conversion [PDF file]. Department of Computer Science, Texas A&M University, Technical Report tamu-cs-tr-2008-7-1.

- Bruce C, To CT, Newton C (2012) Accent on communication: The impact of regional and foreign accent on comprehension in adults with aphasia. Disabil Rehabil 34: 1024-1029. [crossref]

- Anderson-Hsieh J, Johnson R, Koehler K (1992) The relationship between native speaker judgements of non-native pronunciation and deviance in segmentals, prosody and syllable structure. Lang Learn 42: 529-555.

- Amano-Kusumoto A, Hosom JP (2011) A review of research on speech intelligibility and correlations with acoustic features [PDF file]. Center for Spoken Language Understanding (CSLU) Tech Rept 001: 1-16.

- Jung MY (2010) The intelligibility and comprehensibility of world English’s to non-native speakers. Pan-Pacific Assoc Appl Linguis 14: 141-163.

- Levi SV, Winters SV, Pisoni DB (2007) Speaker-independent factors affecting the perception of foreign accent in a second language. J Acoust Soc Amer 121: 2327-2338. [crossref]

- Derwing T, Munro MJ, Wiebe G (1998) Evidence in favor of abroad framework for pronunciation instruction. Lang Learn 48: 393-410.

- Field J (2005) Intelligibility and the listener: The role of lexical stress. TESOL Quart 39: 399-423.

- Lepage A, Busà MG (2014) Intelligibility of English L 2: The effects of incorrect word stress placement and incorrect vowel reduction in the speech of French and Italian learners of English [PDF file]. Proceedings of the International Symposium on the Acquisition of Second Language Speech Concordia Working Papers in Applied Linguistics 5: 387-400.

- Bond ZS, Small LH (1983) Voicing, vowel, and stress mispronunciations in continuous speech. Percept Psychophys 34: 470-474.

- Grosjean F, Gee JP (1987) Prosodic structure and spoken word recognition. Cogn 25: 135-155. [crossref]

- Cutler A, Clifton C Jr (1984) The use of prosodic information in word recognition. In H. Bouma & D. G. Bouwhuis (Eds.), Attention and performance X: Control of language processes. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum 183-196.

- Yenkimaleki M, Heuven VJ (2018) The effect of teaching prosody awareness on interpreting performance: An experimental study of consecutive interpreting from English into Farsi. Perspect 26: 84-99.

- Sapir S, Pawlas AA, Ramig LO, Hinds SL, Countryman S, et al. (2001) Effects of Intensive Phonatory-Respiratory Treatment (LSVT) on voice in two individuals with multiple sclerosis. J Med Speech Lang Pathol 9: 141-151. [crossref]

- Tolhurst G-C (1957) Effects of duration and articulation changes on intelligibility, word reception and listener preference. J Speech Hear Disord 22: 328-334. [crossref]

- Picheny MA, Durlach NI, Braida LD (1986) speaking clearly for the hard of hearing II: Acoustic characteristics of clear and conversational speech. J Speech Hear Res 29: 434-446. [crossref]

- Li N, Loizou P (2008) Factors influencing intelligibility of ideal binary-masked speech: Implications for noise reduction. J Acoust Soc Amer 123: 2287-2294. [crossref]

- Smiljanic´ R, Bradlow A (2008) Speaking and hearing clearly: Talker and listener factors in speaking style changes. Lang Linguist Compass 3: 236-264. [crossref]

- Hazan V, Baker R (2011) Acoustic-phonetic characteristics of speech produced with communicative intent to counter adverse listening conditions. J Acoust Soc Amer 130: 2139-2152. [crossref]

- Dreher JJ, O’Neill JJ (1957) Effects of ambient noise on speaker intelligibility for words and phrases. J Acoust Soc Amer 29: 1320-1323. [crossref]

- Summers WV, Pisoni DB, Bernacki RH, et al. (1988) Effects of noise on speech production: Acoustical and perceptual analyses. J Acoust Soc Amer 84: 917-928. [crossref]

- Ramig LO, Sapir S, Fox C, Countryman S (2001) Changes in vocal loudness following intensive voice treatment (LSVT) in individuals with Parkinson’s disease: a comparison with untreated patients and normal age-matched controls. Mov Disord 16: 79-83. [crossref]

- Patel R, Hustad, KC, Connaghan KP, et al. (2012) Relationship between prosody and intelligibility in children with dysarthria. J Med Speech Lang Pathol 20: 17. [crossref]

- Koschanski G, Grabe E, Colman J, et al. (2005) Loudness predicts prominence: fundamental frequency lends little. J Acoust Soc Amer 118: 1038-1054. [crossref]

- Akil F, Yollu, Umur U, Ozturk O., Yener, M. 10: 2017.

- McCabe DJ, Altman KW (2017) Prosody: An overview and applications to voice therapy. Glob J Oto 7: 555719.

- Schirmer A (2010) Mark my words: Tone of voice changes affective word representations in memory. PLoS One 5: e9080. [crossref]

- Nakatani LH, Schaffer JA (1978) Hearing “words” without words: prosodic cues for word perception. J Acoust Soc Am 63: 234-245. [crossref]

- Patel R, Niziolek C, Reilly K, Guenther FH (2011) Prosodic adaptations to pitch perturbation in running speech. J Speech Lang Hear Res 54: 1051-159. [crossref]

- Cooper N, Cutler A, Wales R (2002) Constraints of lexical stress on lexical access in English: Evidence from native and non-native listeners. Lang Speech 45: 207-228. [crossref]