DOI: 10.31038/AFS.2022416

Abstract

The taxonomy, morphology, some physiological aspects, distribution, behavioral and economic importance of Silurus glanis in Iran are described. It has been reported from Eastern Europe to Central Asia. Up to now, Wels catfish recorded from the Urmia Lake and the Caspian Sea basins. This species is thought to be the largest fish in inland water of Iran. In the most part of Iran being scale less, it could not be eaten for religious reasons.

Keywords

Siluridae, Biology, Morphology, Distribution, Iran

Introduction

Wels catfish, scientifically known as Silurus glanis, belongs to the family Siluridae and is distributed in Eastern Europe, Asia Minor and Central Asia. In Iran, this fish is found in the Basins of the Urmia Lake and the Caspian Sea, Aras to Atrak Rivers [1,2]. It is found mainly in large lakes and rivers and sometimes in the brackish waters of the Black and Baltic Seas. It has been found that this fish feeds on ducks, mice, tall freshwater crabs and small fish at night and spawns in the waters of the Aral Sea as well as in freshwater. This fish is one of the most important commercial fishing items in Anzali wetland, so that it is ranked fifth among 25 species of economic fish in Anzali wetland. Catched fish is mainly eaten fresh, frozen and canned. In addition to the economic exploitation of natural waters from natural waters, it is also considered as a species of farming and recreational fishing.

Classification:

← Class: Actinopterygii

← Infraclass: Teleostei

← Order: Siluriformes

← Family: Siluridae

Physical, Behavioral and Physiological Characteristics of Wels Catfish

Body Shape

It has an elongated body and a sinus that is compressed at the end. S. glanis is said to be a poisonous fish. The dorsal fin is very small and has 3 to 5 soft radii. The anus is very long and reaches up to two thirds of the total length of the fish. The number of soft radii in it is 77 to 92 and its color is the same color as the dorsal surface. The caudal fin is oval in shape and has a slight curvature. The pectoral fin has a thorn and 14 to 17 soft radii. There are probably toxic glands under the base of the breast fin. The ventral fin is darker and smaller than the pectoral fin and has a soft radius of 11 to 13. It has a pair of long whiskers in the upper jaw and two pairs of smaller whiskers below the mandible. There is a row of abrasive teeth on each jaw. Each row of teeth has hundreds of tiny teeth. It also has teeth on the roof of the mouth. It has a large, expandable stomach to swallow large prey and a very large, wide mouth. It has two pairs of relatively large nostrils on the back of the head and near the base of the whiskers. The fin is small breasts under the gill cover. The paws of the pair are round and paddle-like. The caudal fin has more or less two branches and 19 radii [3].

Size

The largest “permanent” fish is freshwater. In the world, the largest reported size is 500 cm (5 m) and the maximum reported weight is 306 kg. A study of skeletal bones shows that it can grow up to 450 kg, but such skeletons have never been trapped [4].

In Iran, the largest size recorded with a hook (with a certificate) weighed 104 kg. In Guilan, S. glanis up to 90 kg are still caught. In the Aras River, with nets, 2.5 meters long and weighing 245 kg have been caught.

Life Span

The maximum age of the Wels cast fish is 80 years. S. glanis bones have been found that are estimated to have lived 100 years before the fish died. Different populations of S. glanis follow different age patterns [5,6].

Food

In different parts of the world: from bony fish such as Abramis, Alburnus, Alosa, Barbus, Capoetobrama, Carassius, Cyprinus, Esox, Neogobius, Perca, Pungitius, Rutilus, Scardinius, Tinca, Vimba, small aquatic mammals, birds, waste and excrement [7-9]. It also feeds on invertebrates, eggs and larvae of other fish, groups of insects, a variety of bipeds and crustaceans during the larval and juvenile stages. Because Wels catfish feeds various range of foods e.g., fishes, amphipods, invertebrates, birds, etc., the chances of plastic particles being transferred from the prey to itself are very high [10-16].

In Iran, its diet consists mostly of bony fish, species such as Cyprinus, Abramis, Carassius, Perca, Liza, Rutilus, Esox, Alosa, frogs, birds and small aquatic mammals, etc. [17-23].

Behavioral Characteristics

Predation

The Wels catfish is semi-voluntarily constantly chasing stimuli until the brain detects one of them and commands it to react. The Wels catfish has very small eyes, a feature that reflects the fact that the Wels catfish is a nocturnal hunter and that its eyes are depleted due to the lack of use of eyes for hunting. Mustache also plays a role in hunting: High mustache is used to hunt and avoid obstacles, and it also has the ability to receive specific vibrations of the body of weak fish. The lower whiskers mostly transfer the condition of the litter to the fish. There are also taste buds on the whiskers.

Wels catfish can track prey directly through audio receivers. It also has the ability to detect the sounds of ordinary fish and weak or trapped fish (for example, on hooks). Wels catfish are often fish eaters, but they welcome any other type of food! Remains of the human body have been found in the viscera, although it may have been dead before being eaten. But there have been numerous reports of equine attacks on dogs that have been drinking water. It has a strong olfactory system, some odors are alarming for Wels catfish: for example, the smell of perch can be a warning to stay away from the spines of this fish.

The units of the taste system in the Wels catfish are the taste buds. Unlike humans, where taste buds are found only on the tongue, in Wels catfish these buds are also on the whiskers and around the mouth. The sense of taste works in harmony with other senses, especially the sense of smell, that is, first the olfactory system detects the presence of food and then the taste system determines its quality. The presence of external taste receptors gives the Wels catfish the ability to taste food without the need to ingest it. This is especially important for Wels catfish, which live in the dark.

Wels catfish live alone, but are seen in pairs or groups during the breeding season.

Reported Wels Catfish Habitats

In the World

Wels catfish are naturally distributed throughout Eastern Europe and Western Asia. This fish is distributed in all rivers from the upper Rhine to the east, i.e. the northern, Baltic, Black, Azov, Aral and Caspian lakes, but its density is in the catchments of the Volga and Danube rivers.

In Iran

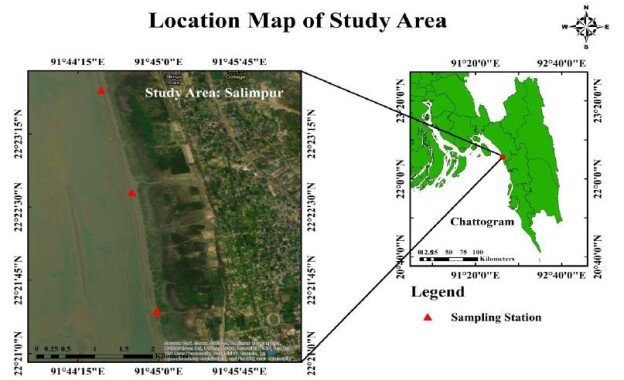

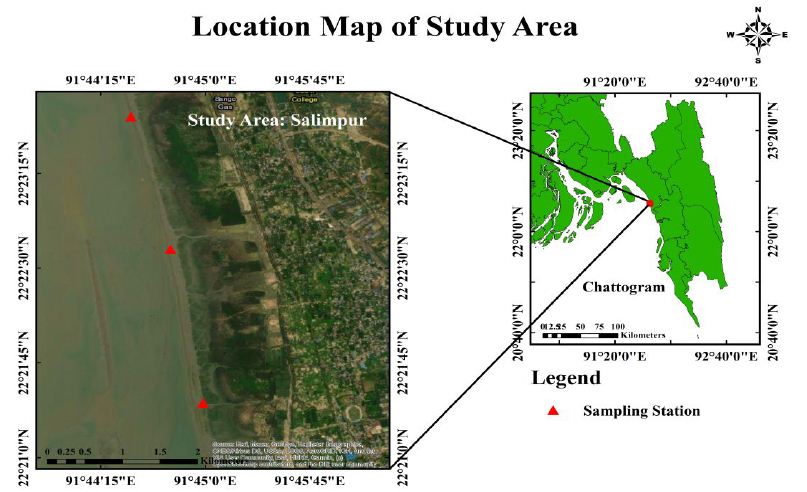

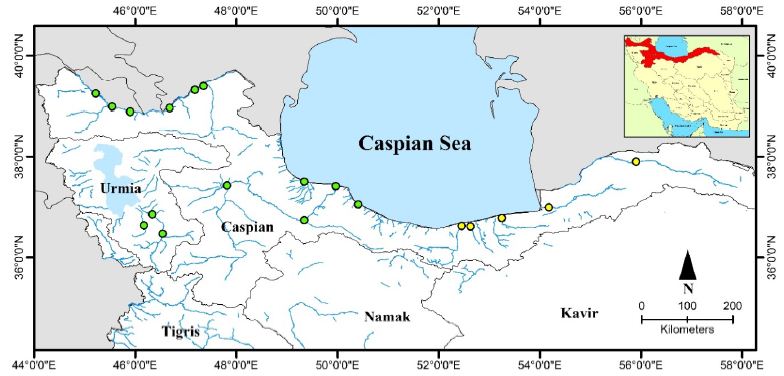

In addition to the Caspian Sea, Wels catfish are found in all rivers in northern Iran from the Atrak River in the northeast to Aras in the northwest [22]. In addition, the rivers leading to Lake Urmia are also home to this fish. The northern parts of Karun, parts of Kurdistan and the Ghezel Ozan tributaries in Zanjan are other areas of distribution of this fish in Iran (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Distribution map of S. glanis in Iran; green circle: current distribution, yellow circle: previous distribution

Figure 2: S. glanis, Recorded from Aras dam (Photo by: Jouladeh-Roudbar).

One of the most important habitats of Wels catfish in Iran is Aras Dam Lake in West Azerbaijan. In studies conducted on this river, Wels catfish have been caught from 6 selected stations in 3 stations along this river. There are also many hills above the dam lake, especially in the area called Cheshmeh Soraya, which is a border region between Iran, Turkey and Nakhchivan, where Wels catfish are concentrated. The river’s potential for the Wels catfish to live behind the Aras Dam has also been proven by scientists in the Republic of Azerbaijan. According to these studies, when the Nakhchivan water reservoir was built on the river in 1973, the predominant fish in the region were the Capoeta capoeta and Barbus cyri, but in 1976 the Wels catfish had the highest weight after the carp. The great depth of the reservoir along with its great length and width has been the cause of this growth.

Another Wels catfish habitat is the Manjil Dam Lake. The trout branches in Zanjan are also one of the places where there are many Wels catfish. The Atrak River in Golestan Province, the Tajan River in Sari, and the Bahnmir River on the outskirts of Babolsar are other Wels catfish habitats in Iran. Valiabad Tonekabon River, Amirkalayeh Wetland and most importantly Anzali Wetland are other places of life of this fish. The Fereydunkenar River was once the most important river in the life of the Wels catfish. In Azerbaijan, the Zarrinehrood, Siminehrood and Talkhehrud rivers (before the drought) were the habitats of the Wels catfish.

Reproduction

Fish usually reach sexual maturity in the second to fourth year of life, at which age the Wels catfish is about 60 to 70 cm long and weighs 900 to 2,000 grams. Wels catfish sometimes migrate up to 25 km for spawning. Wels catfish the male has a drooping skin at the end of the abdomen. In material, this part is smaller but thicker. Males are larger and have the task of caring for the egg and the baby. Wels catfish reproduces once a year. Reproduction takes place at a temperature of 18 to 20 degrees, which if this temperature is not provided, and reproduction will be delayed. Pairs play reproductive games before reproduction, including chasing and jumping out of water.

Wels catfish eggs are yellow and sticky, 3 mm in diameter, and attach to plants. Wels catfish nest. The relative uniformity is high and can reach up to 330,000 per kilogram, indicating that many eggs and larvae are killed. The absolute uniformity of small and medium-sized Wels catfish is from 480 to 11,000. The eggs are concentrated in clusters in the nest and the male fish, which has few sperm, fertilizes them and takes care of them until the larvae hatch (hatch). The incubation period of the eggs is 3 to 5 days (often 50 hours) at a temperature of 24 degrees Celsius. The larvae are about eight and a half millimeters long after hatching. The larvae do not leave the nest until they have absorbed the yolk sac. The eggs, and especially the Wels catfish larvae, like all larvae that live in the nest, have found special respiratory adaptations to withstand the lack of oxygen in the nest. Wels catfish grow very fast in the first year of life.

References

- Jouladeh-Roudbar A, Eagderi S, Vatandoust S (2015) First record of Paraschistura alta (Nalbant and Bianco, 1998) from Eastern Iran and providing its COI barcode region sequences (Teleostei: Nemacheilidae). Iranian Journal of Ichthyology 2: 235-243.

- Jouladeh-Roudbar A, Vatandoust S, Eagderi S, Jafari-Kenari S, Mousavi-Sabet H (2015) Freshwater fishes of Iran; an updated checklist. Aquaculture, Aquarium, Conservation & Legislation 8: 855-909.

- Jouladeh-Roudbar A, Eagderi S, Esmaeili HR (2016a) First record of the striped bystranka, Alburnoides taeniatus (Kessler, 1874) from the Hari River basin, Iran (Teleostei: Cyprinidae). Journal of Entomology and Zoology studies 4: 788-791.

- Jouladeh-Roudbar A, Eagderi S, Hosseinpour T (2016b) Oxynoemacheilus freyhofi, a new nemacheilid species (Teleostei, Nemacheilidae) from the Tigris basin, Iran. FishTaxa 1: 94-107.

- Jouladeh-Roudbar A, Eagderi S, Soleimani A (2017a) First record of Petroleuciscus esfahani Coad and Bogutskaya, 2010 (Actinopterygii: Cyprinidae) from the Karun River drainage, Persian Gulf basin, Iran. International Journal of Aquatic Biology 4: 400-405.

- Jouladeh-Roudbar A, Eagderi S, Ghanavi HR, Doadrio I (2017b) A new species of the genus Capoeta Valenciennes, 1842 from the Caspian Sea basin in Iran (Teleostei, Cyprinidae). ZooKeys 682: 137.

- Jouladeh-Roudbar A, Eagderi S, Ghanavi HR, Doadrio I (2016c) Taxonomic review of the genus Capoeta Valenciennes, 1842 (Actinopterygii, Cyprinidae) from central Iran with the description of a new species. FishTaxa 1: 166-175.

- Jouladeh-Roudbar A, Eagderi S, Murillo-Ramos L, Ghanavi HR, Doadrio I (2017c) Three new species of algae-scraping cyprinid from Tigris River drainage in Iran (Teleostei: Cyprinidae). FishTaxa 2: 134-155.

- Jouladeh-Roudbar A, Eagderi S, Sayyadzadeh G, Esmaeili HR (2017d) Cobitis keyvani, a junior synonym of Cobitis faridpaki (Teleostei: Cobitidae). Zootaxa 4244: 118-126.

- Jouladeh-Roudbar A, Ghanavi HR, Doadrio I (2020) Ichthyofauna from Iranian freshwater: Annotated checklist, diagnosis, taxonomy, distribution and conservation assessment. Zoological Studies 59: e21.

- Vajargah MF, Namin JI, Mohsenpour R, Yalsuyi AM, Prokić MD, et al. (2021) Histological effects of sublethal concentrations of insecticide Lindane on intestinal tissue of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Veterinary Research Communications 45: 373-380. [crossref]

- Yalsuyi AM, Vajargah MF, Hajimoradloo A, Galangash MM, Prokić MD, et al. (2021) Evaluation of behavioral changes and tissue damages in common carp (Cyprinus carpio) after exposure to the herbicide glyphosate. Veterinary Sciences 8: 218. [crossref]

- Vajargah MF, Mohsenpour R, Yalsuyi AM, Galangash MM, Faggio C (2021) Evaluation of histopathological effect of roach (Rutilus rutilus caspicus) in exposure to sub-lethal concentrations of Abamectin. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution 232: 1-8.

- Vajargah MF (2021) A Review on the Effects of Heavy Metals on Aquatic Animals. ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES 2.

- Vajargah MF, Yalsuyi AM, Hedayati A (2018) Effects of dietary Kemin multi-enzyme on survival rate of common carp (Cyprinus carpio) exposed to abamectin. Iranian Journal of Fisheries Sciences 17: 564-572.

- Vajargah MF, Hedayati A (2017) Toxicity Effects of Cadmium in Grass Carp () and Big Head Carp (). Transylvanian Review of Systematical and Ecological Research 19: 43-48.

- Yalsuyi AM, Hedayati A, Vajargah MF, Mousavi-Sabet H (2017) Examining the toxicity of cadmium chloride in common carp (Cyprinus carpio) and goldfish (Carassius auratus). Journal of Environmental Treatment Techniques 5: 83-86.

- Vajargah MF (2022) Familiarity with Caspian Kutum (Rutilus kutum). Aquac Fish Stud 4: 1-2.

- Sattari M, Imanpour Namin J, Bibak M, Forouhar Vajargah M, Bakhshalizadeh S, et al. (2020) Determination of trace element accumulation in gonads of Rutilus kutum (Kamensky, 1901) from the south Caspian Sea trace element contaminations in gonads. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, India Section B: Biological Sciences 90: 777-784.

- Sattari M, Bibak M, Bakhshalizadeh S, Forouhar Vajargah M (2020) Element accumulations in liver and kidney tissues of some bony fish species in the Southwest Caspian Sea. Journal of Cell and Molecular Research 12: 33-40.

- Sattari M, Bibak M, Forouhar Vajargah M (2020) Evaluation of trace elements contaminations in muscles of Rutilus kutum (Pisces: Cyprinidae) from the Southern shores of the Caspian Sea. Environmental Health Engineering and Management Journal 7: 89-96.

- Vajargah MF, Hossaini SA, Niazie EHN, Hedayati A, Vesaghi MJ (2013) Acute toxicity of two pesticides Diazinon and Deltamethrin on Tench (Tinca tinca) larvae and fingerling. International Journal of Aquatic Biology 1: 138-142.

- Yousefi M, Jouladeh-Roudbar A, Kafash A (2020) Using endemic freshwater fishes as proxies of their ecosystems to identify high priority rivers for conservation under climate change. Ecological Indicators 112: 106137.