DOI: 10.31038/AFS.2021351

Abstract

Aquaculture is a growing industry with a high demand mainly due to its significant contribution to the food sector. One of the main challenges of aquaculture is the prevention and treatment of fish diseases through the extensive application of antibiotics. However, information on the various consequences of pharmaceuticals in fish farms remains limited to this day. Based on the existing scientific literature, this report aims to give an overview of the most commonly used antibiotics in aquaculture, which belong to the groups of quinolones, sulfonamides, tetracyclines, amphenicols and macrolides. This review paper summarizes the information available on the characterization, ecotoxicology and application of florfenicol, erythromycin, furazolidone, oxolinic acid, ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, sulfadiazine, sulfadimethoxine, sulfamethoxazole, oxytetracycline and tetracycline.

Keywords

Veterinary drugs, Antibiotics, Characterization, Ecotoxicity, Treatment

Introduction

Aquaculture is the food production sector with the strongest growth, as farming, trading, and processing of marine products are of major social, economic, and environmental importance. Global fish production has reached 179 million tons in 2018, where aquaculture accounted for 46% of the total production. China is by far the major fish producer with 35% of the worldwide production [1]. The recent expansion of aquaculture raises concerns related to the destruction of natural habitat, the utilization of potentially harmful synthetic compounds, the effect of escapees on wild stocks, wasteful production of fishmeal and fish oil, and social and cultural effects on aquaculture laborers and communities. Fish farming requires extensive use of veterinary drugs, including antibiotics. Some of these pharmaceuticals are only partially metabolized, and then excreted, entering the aquatic environment in their native form or as metabolites and showing considerable persistence [2]. Quinolones, amphenicols, macrolides, tetracyclines, and sulfonamides are the most widely used groups of antibiotics [3-6]. The 10 drug molecules that are the most commonly used to prevent and treat fish diseases are: florfenicol, erythromycin, furazolidone, oxolinic acid, ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, sulfadiazine, sulfadimethoxine, sulfamethoxazole, oxytetracycline and tetracycline [7]. Due to their variety and accumulation in the environment, aquatic organisms are exposed to various antibiotics that can be found as mixtures with potentially enhanced “cocktail effect”, which have not been studied in-depth to this day. The main concerns associated to the use of veterinary drugs are the development of antibiotic resistance, mutagenicity, and inhibition or acute toxicity of aquatic organisms [8]. In natural settings, prolonged exposure to low doses of antibiotics can lead to the selective proliferation of resistant bacteria, which can transfer their resistance genes to other bacterial species, including pathogenic bacteria [9]. Despite their low concentrations, the bioaccumulation and biomagnification of pharmaceuticals can have a significant impact on the aquatic ecosystem and even human health (Pan et al., 2019). Furthermore, additional sources of pharmaceuticals have to be considered for extensive environmental evaluation and implementation of possible control measures. These sources include pharmaceutical facilities, hospitals, and households, as a significant percentage of drugs is not fully eliminated by conventional water treatment technologies [10]. In fish farming, drugs are usually coated (mostly with fish oil, gelatin, or vegetable oil) and gradually added to the fish food. The coating agent helps to prevent the drug from entering the water in the fish farm [11], but effluents containing unconsumed food pellets with high levels of antibiotics are released into the aquatic environment without any treatment [12]. There is a limited knowledge about the fate and consequences of antibiotics once they reach the environment. This report aims at compiling information on available analytical methods to detect and identify low concentrations of antibiotics in the environment, summarize potential ecotoxicological risks, and ultimately to propose possible treatment technologies to effectively eliminate them.

This review paper is divided into four parts. The first one describes the most commonly employed molecules, their use and the associated drawbacks. The second part is devoted to their ecotoxicity. The third part reviews the current methods used for the analysis of these pharmaceuticals in various environmental matrices. The last part discusses the water treatment processes currently applied to remove and/or degrade these compounds.

Main Drugs Used in Fish Farming

This part reviews the six main families of drugs usually used in fish farming, their main properties and their mode of administration: cyclins, amphenicols, sulfonamides, quinolones, macrolides and nitrofurans.

Tetracycline

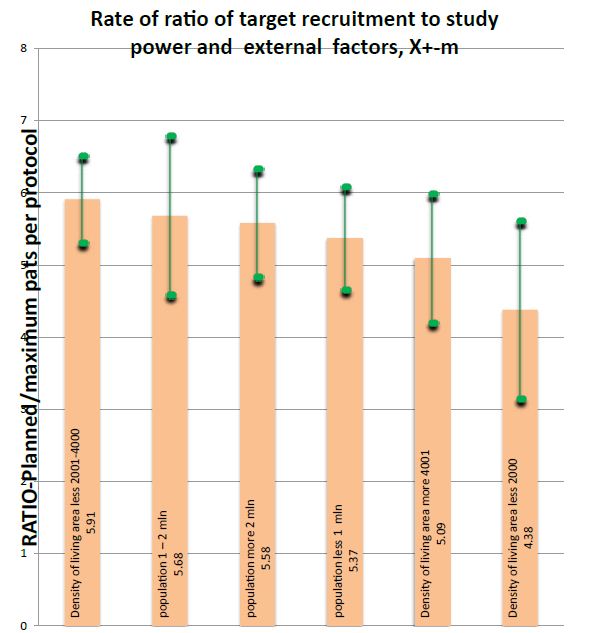

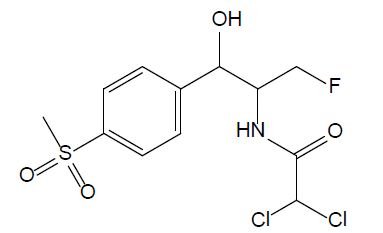

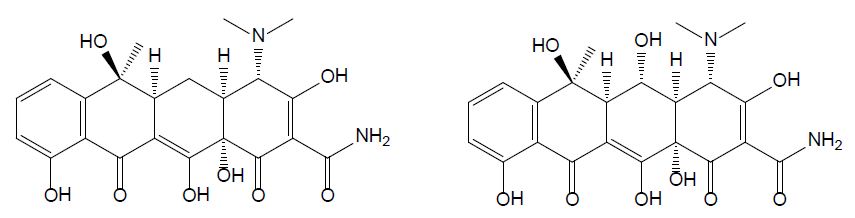

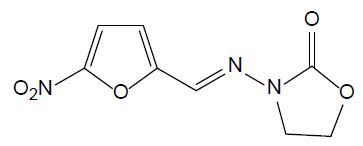

Tetracyclines were discovered in the 1940s and showed activity against a wide range of microorganisms. They are inexpensive and applied for the treatment of human and animal infections as well as in animal feed to promote growth. Tetracycline (TET) is one of the most common type of antibiotics used in medicine, agriculture, and animal husbandry; its chemical structure comprises a fused linear tetracyclic nucleus to which various functional groups are attached as shown in Figure 1 [13]. Due to its widespread application, a growing number of pathogens are developing resistance to tetracycline, therefore decreasing its efficiency. Oxytetracycline (OTC) is a broad-spectrum antibiotic used in veterinary medicine to treat, among others, diseases in fish [8]. It has a role as an antibacterial and anti-inflammatory drug, protein synthesis inhibitor, and antimicrobial agent (ChEBI 27701). OTC is active against gram-positive bacteria, gram-positive bacilli, and gram-negative organisms [14]. In the past decades, the use of OTC increased with the development of aquaculture and livestock production [15] and thanks to its low cost and its broad-spectrum efficacy in treating infections [14]. There are three main ways to administer OTC to farmed fish: through the feed, bath treatment, and injection. Among these options, the incorporation of the antibiotic in food for oral administration is the most common and the one with the least risk in terms of environmental pollution [8]. OTC is only minimally metabolized and is mainly excreted through urine.

Figure 1: Chemical structures of tetracycline (left) and oxytetracycline (right).

Amphenicols

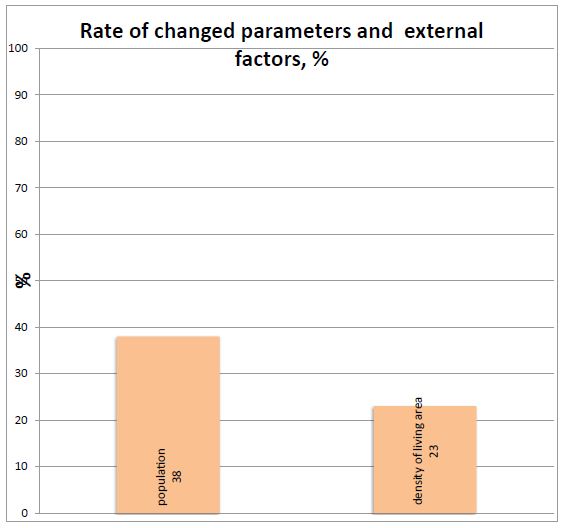

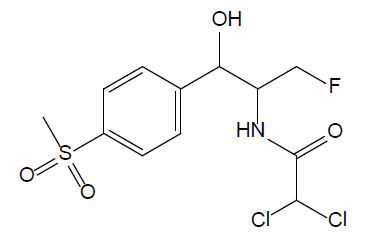

Amphenicols are important veterinary antibiotics with wide-spectrum antimicrobial activity. Florfenicol (FF, see Figure 2) is an antimicrobial agent, which is extensively used in fish farming. Grave et al. investigated the use of antimicrobial drugs in Norwegian aquaculture from 2000 to 2005 by analyzing prescription data, in close relation with the national data of the sold antimicrobial drugs. FF has long been the most abundant drug prescribed for halibut farming in Norwegian aquaculture [16]. In 2013, 0.3 tons and 300 tons of FF were used in fish farming in Norway and Chile, respectively. In 2016, it was reported that over 1000 tons of FF were used in China. Temperature, exposure time, coating agent, and pellet size are the important factors that influence release of FF into the water [11]. According to the EU Council directive, the maximum residue limit value of the sum of FF and florfenicol amine in muscle and skin in natural proportions of healthy fish was given as 1,000 μg/kg (Commission Regulation EU No 37/2010). FF is bacteriostatic, which means it prevents the bacteria from protein synthesis [11]; it is usually used for respiratory and intestinal infections [17].

Figure 2: Chemical structure of chloramphenicol.

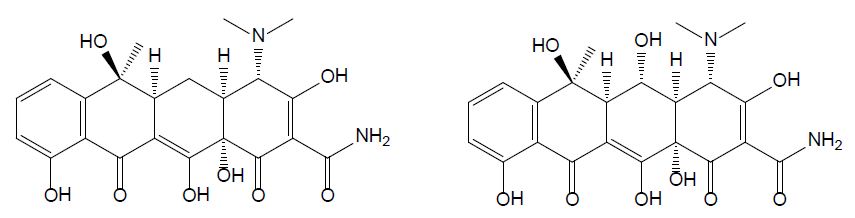

Sulfonamides

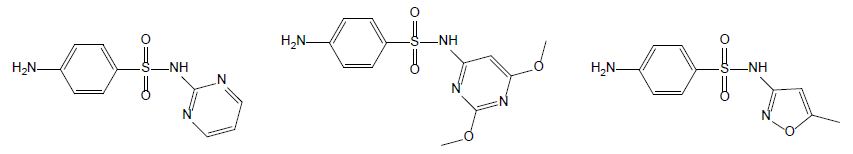

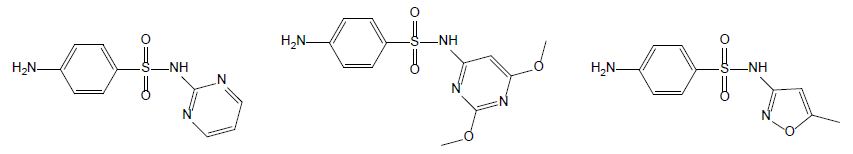

Sulfonamides are used as chemotherapeutics to treat various bacterial infections in veterinary medicine [5]. Due to their broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity and low cost, they were among the most applied antibiotics and thus, commonly detected in aquaculture wastewater [18]. Currently, only a few drugs belonging to sulfonamides are used due to the developed resistance in previously susceptible microorganisms. Sulfadiazine (SDZ) and sulfadimethoxine (SDM) are the most used antibiotics in fish farming; their chemical structures are displayed Figure 3. When applied to animals, sulfadiazine, is excreted in its native form and its N4-acetyl metabolite [19]; it is often considered as a representative antibiotic of sulfonamides due to its wide presence in the environment with low hydrophobicity and high water solubility in [20]. Sulfadimethoxine (SMX – Figure 4) is a broad-spectrum antibiotic used in human therapy, aquaculture, livestock, and veterinary medicine. Although its use is decreasing in humans, its low cost secures its popularity in veterinary medicine [21].

Figure 3: Chemical structures of sulfadiazine (left hand), sulfamethoxine (middle) and sulfamethoxazole (right hand).

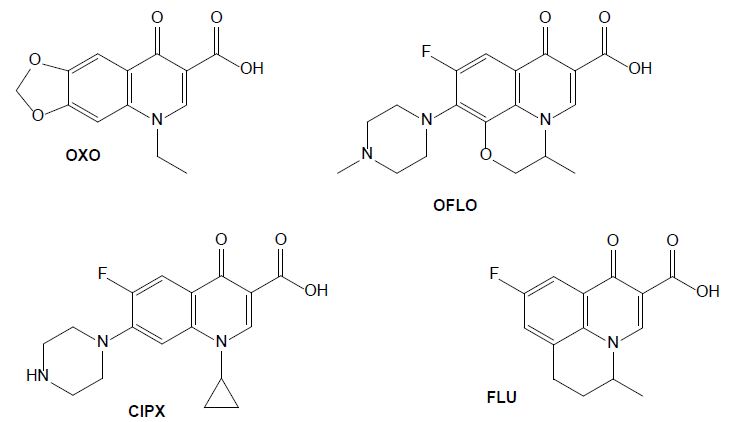

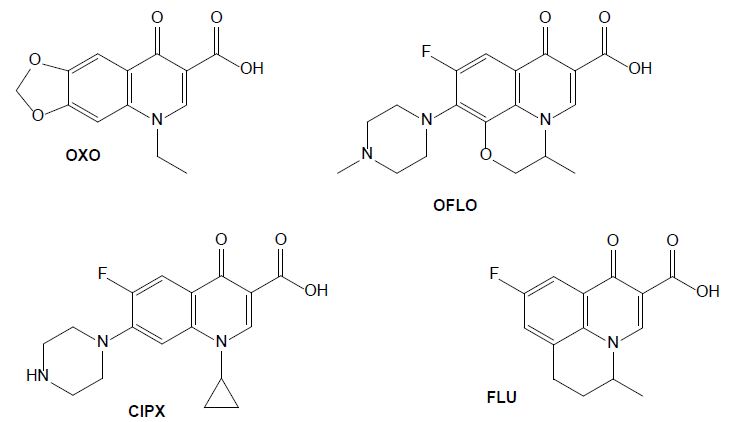

Figure 4: Chemical structures of some quinolone drugs: oxolinic acid (OXO), ofloxacin (OFLO), ciprofloxacin (CIPX) and flumequine (FLU).

Quinolones

The antibiotics from the group of quinolones are widely used in human and veterinary medicines to treat infectious diseases and to promote livestock growth (Yang et al., 2020). They directly inhibit DNA replication by interacting with two enzymes. Oxolinic acid (OXA) is efficient against a gram-negative bacterium that causes diseases such as vibriosis, yersiniosis, and furunculosis. It has been administrated to farm fishes as a prophylactic and chemotherapeutic agent acting as anti-infective, antibacterial and enzyme inhibitor [22]. Its use in humans is now prohibited in several countries but is still frequently used in veterinary medicine to treat urinary infections, and it was detected in animal excreta [23]. Ofloxacin (OFLO) is a quinolone that was previously used for human health, for the therapy of mild to moderate bacterial infections, it has since been replaced by more potent and less toxic antibiotics, however it is still used in aquaculture. In the group of quinolones, ciprofloxacin (CIPX) is considered as a representative drug against gram-negative bacteria; it has been detected in marine environment, as well as in freshwater. In aquatic environments it affects the metabolism of some bacteria carbon sources and is toxic to fishes (Yang et al., 2020). Flumequine (FLU), as a first generation quinolone, is structurally related to nalidixic and oxolinic acid [24]. Oxidation experiments carried out on flumequine led to a total of 19 transformation products issued from hydroxylation, dehydrogenation, hydroxyl substitution, decarboxylation, demethylation, and ring opening transformation pathways [25].

Macrolides

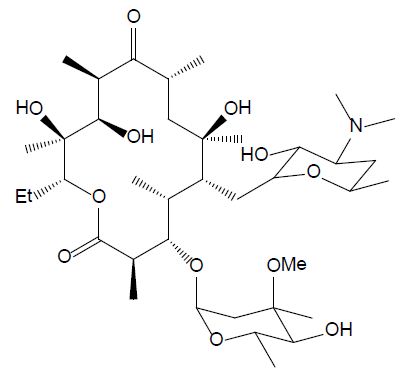

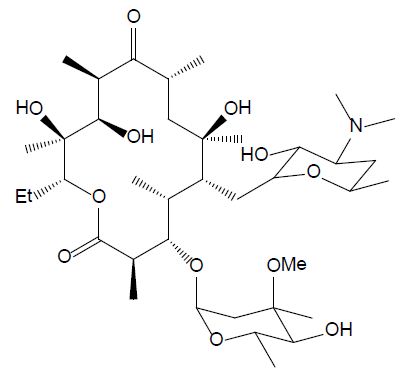

The group of macrolides refers to macrocyclic lactone ring structures; they are used for their immunomodulatory and antibacterial functions (Yang et al., 2020). In addition to their antibacterial action, macrolides can have an anti-inflammatory effect by decreasing the activity of immune cells and altering bacterial cells. Erythromycin (ERY, see Figure 5) is efficient against gram-positive bacteria, as streptococcus species. However, most of the microorganisms that cause infection in fish are gram-negative, so this compound should only be utilized after fish culturing and sensitivity test results should affirm its viability. Additionally, erythromycin is not efficient in bath treatment and must be administered by injection or in the feed [26].

Figure 5: Chemical structure of erythromycin.

Nitrofurans

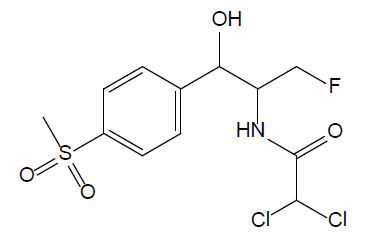

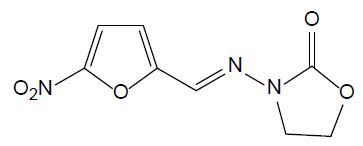

Nitrofurans are antimicrobial agents which have been used for animal production. They have strong impact on gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria and act against protozoa as well. In 1993, their application has been banned by EU due to their potential mutagenic effect. Furazolidone (FUR, see Figure 6) is a nitrofuran antibiotic widely used in human and aquaculture medicine against protozoal and Helicobacter pylori infections. Its biodegradation leads to 3-amino-2-oxazolidone and β-hydroxyethylhydrazine [27]. It is still utilized in developing countries, although it is banned in developed countries.

Figure 6: Chemical structure of furazolidone.

Ecotoxicology of the Main Drugs Used for Fish Farming

Table 1 presents a summary of the ecotoxicological data available for veterinary drugs mainly used in fish farming. The data are discussed below, for each pharmaceutical family.

Table 1: Ecotoxicology data for the veterinary drugs mainly used in fish farming

|

Drug

|

Ecotoxic effect |

Reference

|

| Tetracycline & oxytetracycline, |

24 h-EC50 for Stentor coeruleus and Stylonychia lemnae were 94.4 mg/L and 40.1 mg/L, respectively |

Magdaleno et al., 2017 |

| Florfenicol |

Inhibiting growth rate of Corbicula fluminea at concentrations higher than 1.8 mg/L |

Guillermino et al., 2017 |

| Sulfadiazine |

LC50 of 1.884 mg/L for Daphnia magna |

Duan et al., 2020 |

| Sulfamethoxazole |

IC50 = 12.56 ± 4.48 mg/L for A. fischeri |

Drzymała & Kalka, 2020 |

| Sulfadimethoxine |

EC50 of 248 mg/L for daphnia magna |

Tkaczyk et al., 2021 |

| Oxolinic acid |

4.6 mg/L EC50 for Daphnia magna |

Tkaczyk et al., 2021 |

| Ofloxacin |

Chronic toxicity and drug resistant bacteria |

H. Guo et al., 2021 |

| Ciprofloxacin |

Concentrations greater than or equal to 10 μg/L: ecotoxic for development, growth, detoxification and oxidative stress enzymes |

Białk-Bielińska et al., 2011 |

| Flumequine |

Affecting growth rate of Daphnia magna at 23% across generation |

De Liguoro et al., 2019 |

| Erythromycin |

EC50 values in the range of 10 -30 mg/L for Vibrio fischeri |

Liu et al., 2018 |

| Furazolidone |

Very toxic to Alivibrio fischeri with an EC50 of 2.05 mg/L |

Lewkowski et al., (2019) |

Tetracyclines

In aquaculture, oxytetracycline is one of the most used antibiotics that raises concerns due to its effects on human and animal health, and environmental pollution [8]. In the marine environment, oxytetracycline and quinolones are photochemically degraded and form divalent cationic complexes in the presence of Ca2+ and Mg2+ ions, causing a loss in antibacterial activity. In freshwater, the antimicrobial activity of tetracyclins is of bigger concern due to the development of antibiotic resistance [28]. OTC inhibits the growth of two species of algae: pseudokirchneriella subcapitata (the international standard species for evaluation of inhibition) and Ankistrodesmus fusiformis (native from Argentina). The former was the most sensitive with an EC50 of 0.92±0.30 mg/L [29]. OTC can also affect nitrification since the main bacteria responsible for biofilters – nitrosomonas that promote the conversion of ammonia to nitrite and Nitrobacter that convert nitrite to nitrate – are gram-negative. Li et al. investigated the toxic effect of tetracycline and tetracycline hydrochloride on two model ciliates: Stentor coeruleus and Stylonychia lemnae. The 24 h-EC50 of tetracycline for Stentor coeruleus and Stylonychia lemnae were 94.4 mg/L and 40.1 mg/L, respectively. For tetracycline hydrochloride, the EC50 for Stentor coeruleus and Stylonychia lemnae were 8.39 mg/L and 14.0 mg/L, respectively [15]. This shows that tetracycline hydrochloride is more toxic than tetracycline in these test organisms. Both compounds deteriorate the ultra-cell structure and inhibit the cell growth rate [29].

Amphenicols

Florfenicol (FF) restrains the bacterial protein synthesis efficiency by binding to 50S subunit and 70S ribosome, and it is listed as the top-priority monitoring compounds in veterinary drugs in South-Korea [30]. FF also inhibits the hematopoietic system [31] and deteriorates the mobility, regeneration, and population increase of the tropical Cladocera silvestrii [32]. It also decreases egg hatchability and hinders the development of the cardiovascular system [33]. Guilhermino et al. showed that a FF concentration in water greater than 1.8 mg/L can inhibit the growth of the mollusk Corbicula fluminea [34].

Sulfonamides

The chronic and acute toxicity of sulfadiazine on the crustacean Daphnia magna was investigated and the LC50 value was determined as 1.884 mg/L [35]. The exposition of zebrafish to some sulfonamides, including sulfadiazine, caused an increased heart rate and abnormal swimming. This investigation also proved that sulfadiazine was a typical inducer of metabolic enzymes and suggested a potential ecotoxicological risk [36]. It is important to consider that sulfadiazine can have an impact on biological water treatment processes. Li et al. studied the effects of this antibiotic on a sequencing batch biofilm reactor (SBBR). They found that a sulfadiazine concentration higher than 6 mg/L inhibits COD (Chemical Oxygen Demand) and ammoniacal nitrogen removal within the SBBR when treating aquaculture waste [37]. Sulfadiazine promotes the secretion of extracellular polymeric substances by the microorganisms and impacts the biofilm composition, it has a direct impact on nitrification and the removal of organic matter. Sulfamethoxazole has been studied in a microcosmos composed of water, sediment and zebrafishes. The drug concentration decreased gradually in water while increasing over time in sediment and zebrafish. Bioaccumulation in zebrafish was reduced by 13-28% in the presence of sediment particles in the water; it was further reduced (24-33%) when increasing the water salinity [38]. In the study conducted by [39], sulfadimethoxine was considered to be moderately toxic with an EC50 towards the green algae Chlorella vulgaris of 4.24 mg/L in fresh water, which was measured to be higher (11.2 mg/L) in salt water [39].

Quinolones

According to a study by Tkaczyk et al., oxolinic acid EC50 was 4.6 mg/L EC50 for Daphnia magna [40]. Sun et al. investigated the bioaccumulation of ofloxacin in crucian carp and showed that fluorine increases the bioaccumulation of the antibiotic; higher bioaccumulation potential appears at a low concentration of drug, mostly in the liver [41]. De Liguoro et al. evaluated the effect of continuous and alternate exposure of flumequine at 2 mg/L on Daphnia magna survival, growth, and reproduction. At this concentration, mortality was observed at a rate of 23 ± 14% across generation [42].

Macrolides

Erythromycin has shown medium risk for algae, but bacteria are the main target of antibiotics such as erythromycin. Erythromycin can cross the cell membrane of the bacteria and bind to 50S subunit ribosome [43]. It is also very persistent in the environment due to having aromatic rings, which makes it refractory [44].

Nitrofurans

Lewkowski et al. investigated the effect of furazolidone on growth of oat, radish Sativus, and Alivibrio fischeri bacteria. Their results indicated that furazolidone is very toxic to Alivibrio fischeri with an EC50 of 2.05 mg/L [45]. The accumulation of furazolidone metabolites have been reported in the literature [5]; its use is prohibited by the Food and Drug Administration due to being a nitrofuran compound and inhibiting monoamine oxidase [46].

Methods for Characterization of Drugs Used in Fish Farming

Table 2 presents a summary of the analytical approaches employed for the detection and quantification of veterinary drugs mainly used in fish farming; protocols and methods are discussed below.

Table 2: Analytical methods reported for the detection and quantification of the main antibiotic veterinary drugs used in fish farming

|

Drug type

|

Matrix |

Characterization methoda |

MS typeb |

Sample preparationc |

Analytical column |

LC Mobile phased |

Reference

|

| Tetracyclins including OTC |

Feeds |

HPLC-UVD/FLD |

– |

LLE using acetonitrile and Na2EDTA-Mcllvaine buffer solution |

C18 Hypersil GoldTM (250 x 4.6 mm, 5 μm) |

Phase A: H2O + sodium acetate CaCl2 + EDTA

Phase B: ACN

Phase C: MeOH |

Han et al., 2020 |

| Antibiotic drugs

Including SMX, SDZ, SMZ, CIPX, OFLO, TET and ERY |

Wastewater |

UPLC-MS/MS |

TQ |

SPE using an Oasis HLBTM cartridge) |

C18 BEHTM (50 x 2.1 mm, 1.7 µm) |

Phase A: H2O + FA

Phase B: ACN or MeOH |

Li et al., 2009 |

| Sulfonamides, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines and other veterinary drugs |

Seafood samples |

UPLC-MS/MS |

TQ |

QuEChERS procedure |

C18 Hypersil GoldTM (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.9 μm) |

Phase A: H2O / MeOH + FA

Phase B: ACN + FA |

Dinh et al., 2020 |

| Metabolites of nitrofurans and FUR |

Shrimp body |

LC-MS/MS |

TQ |

Hydrolysis + double LLE using ethyl acetate |

C18 SymmetryTM (150 x 2.1 mm, 3.5 μm) |

Phase A: ACN

Phase B: H2O + FA |

Douny et al., 2013 |

| 4 tetracyclines including TET, OTC; quinolones including FLU, CPIX and OXA |

Fish muscles |

LC-MS/MS |

TQ |

Liquid extraction with trichloroacetic acid |

C18 Zorbax Eclipse XDBTM (150 × 4.6 mm, 5.0 µm) |

Phase A: H2O + HFBA

Phase B: ACN |

Guidi et al., 2018 |

| OTC |

Sol interstitial water |

LC-MS/MS |

TQ |

Centrifugation, filtration |

C18 Xterra MSTM (100 x 21 mm, 3.5 µm) |

Phase A: MeOH + FA

Phase B: MeOH / H2O + FA |

Halling-Sørensen et al., 2003 |

| FF |

Water in recirculating aquaculture system |

HPLC-PDA |

– |

SPE using an Oasis HLBTM cartridge |

Hypersil GOLDTM (250 x 4.6 mm, 5 μm) |

Phase A: ACN

Phase B: H2O |

Zhang et al., 2020 |

| FF and its residues |

Beef meat |

LC-MS/MS |

TQ |

SPE using an Oasis MCXTM cartridge |

C18 Inertsil ODS-4TM (150 × 2.1 mm, 3-μm) |

Phase A: H2O + acetic acid

Phase B: ACN |

Saito-Shida et al., 2019 |

| FF |

Fish feed |

LC-MS/MS |

TQ |

Centrifugation with ACN addition |

C18 SBTM (50 x 2.1 mm, 1.8 µm) |

Phase A: H2O + acetic acid

Phase B: ACN / MeOH |

Barreto et al., 2018 |

| 14 sulfonamide antibiotic residues |

309 marine products |

HPLC-PDA

UPLC-MS/MS |

TQ |

Centrifugation with ACN addition |

C18 CapcellpakTM (250 x 4.6 mm, 5 ㎛) for HPLC-PDA

C18 Acquity UPLC BEHTM (100 x 2.1 mm, 1.7 µm) for UPLC-MS/MS |

Phase A: H2O + KH2PO4

Phase B: MeOH

for HPLC-PDA

Phase A: H2O + FA

Phase B: ACN + FA

for UPLC-MS/MS |

Won et al., 2011 |

| 20 antibiotics including FF, SDZ, SMX, CPIX, TET, OTC and ERY |

Surface waters |

UPLC-MS/MS |

TQ |

SPE using an Oasis HLBTM cartridge |

C18 HSS T3TM (100 x 2.1 mm, 1.8 µm) |

Phase A: H2O + FA

Phase B: ACN + FA |

Yan et al., 2013 |

| 19 sulfonamides including SDZ, SDM and SMX |

Ebro river, WWTP samples |

LC-MS/MS |

QqLIT |

on-line SPE using Oasis HLBTM or Oasis MCXTM cartridges |

C18 AtlantisTM (150 × 2.1 mm, 3 µm |

Phase A: H2O + FA

Phase B: ACN + FA |

García-Galán et al., 2011 |

| 73 pharmaceuticals including TET, OTC, SDZ, SMX, OFLO, FLU, CPIX and ERY |

River water, WWTP influent and effluent |

LC-MS/MS |

QqLIT |

on-line SPE using a Oasis HLBTM cartridge |

C18 Purospher Star RP-18TM endcapped column (125 × 2.0 mm, 5 μm) |

Phase A:

ACN / MeOH

Phase B: H2O |

Gros et al., 2009 |

| 20 antibiotics including

CIPX, ERY, SMZ, SMX, TET and OTC |

Raw influent, treated effluent, surface water |

LC-MS/MS |

TQ |

on-line SPE using a combination of SBTM and HR-XTM cartridges |

C18 Poroshell 120 ECTM (100 x 3.0 mm, 2.7 μm) |

Phase A: H2O + FA

Phase B: ACN + MeOH |

Tran et al., 2016 |

| SMX and its photoproducts |

Aquatic organisms |

LC-MS/MS |

TQ |

No sample preparation |

C18 Zorbax eclipse plusTM (50 x 2.1 mm, 1.8 µm) |

Isocratic mobile phase H2O / ACN |

Li et al., 2020 |

| OTC, FF, OXA and FLU |

Marine sediments |

HPLC-PDA-FLD |

– |

LLE (using oxalic acid in methanol) assisted by sonication |

Kromasil PhenylTM (250 x 4.6 mm, 5 µm) |

Phase A: H2O + TFA

Phase B: MeOH + TFA Phase C: ACN + TFA, with or without gradient |

Norambuena et al., 2013 |

| 46 antimicrobial drug residues including sulfonamides, tetracyclines, quinolones, macrolides, nitrofurans and phenicols |

Aquatic matrices, pond water |

UPLC-HRMS |

OrbitrapTM |

SPE using an Oasis HLBTM cartridge |

C18 Hypersil GoldTM (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.9 μm) |

Phase A: H2O + TFA

Phase B: MeOH + TFA |

Goessens et al., 2020 |

| 11 fluoroquinolones including OFLO and CIPX |

Wastewater and sludges |

UPLC-MS/MS |

Q-trap |

SPE using molecularly imprinted polymer cartridges |

C18 Proshell 120 SBTM (100 × 2.1 mm, 2.7 µm) |

Phase A: H2O + FA

Phase B: MeOH + FA |

Yu et al., 2020 |

| Fluoroquinolone residues |

Sewage samples |

LC-MS/MS |

TQ |

on-line SPE with micellar desorption |

C18 SymmetryTM (150 x 3.9 mm, 4 µm) |

Isocratic mobile phase consisting of H2O + MeOH |

Montesdeoca-Esponda et al., 2012 |

| FLU and OXA |

Aquatic sediments and agricultural soils |

HPLC-FLD |

– |

MAE |

C8 InertsilTM (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm) |

Isocratic mobile phase consisting of H2O + oxalic acid buffer + ACN |

Prat et al., 2006 |

| FLU |

Ultrapure water, tap water, secondary clarifier effluent and river water |

HPLC-FLD

LC-MS/MS |

Q-TOF |

Microfiltration |

C18 BDS HypersilTM (250 x 4,6 mm, 5 μm) |

Phase A: H2O + FA

Phase B: MeOH |

Qui et al., 2019 |

a LC: liquid chromatography, HPLC: high performance liquid chromatography, UPLC: ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography, UVD: UV detector, FLD: fluorescence detector, PDA: Photodiode array detector, MS/MS: tandem mass spectrometry, HR-MS: high resolution mass spectrometry

b Q: quadrupole, TQ: triple quadrupole, q: collision cell, TRAP: ion trap, LIT: linear ion trap, TOF: time-of-flight

c LLE: liquid-liquid extraction, SPE: solid phase extraction, QuEChERS: sample preparation method (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Efficient, Rugged and Safe), MAE : microwave assisted extraction

d ACN: acetonitrile, MeOH: methanol, EDTA: ethylenediaminotetraacetic acid, FA: formic acid, TFA: trifluoro acetic acid

The first step of the analytical process consists in sample preparation, which includes extraction of analytes from the matrix, purification and concentration. When imposed by the analytical technique, a derivation step is added at the end of the process. Solid phase extraction (SPE) has been extensively reported as a tool for choice for the extraction of the pharmaceuticals mainly used in fish farming because (i) it is suitable for very complex matrices, (ii) it is highly selective, and (iii) it permits significant pre-concentration. Furthermore, SPE can be installed on-line with a chromatographic system and automated, which allows high throughput analysis; this is the case for some studies reported in Table 2 [47]. Oasis HLB™ are the most used cartridges in the reported studies, as they are suitable for the simultaneous extraction of compounds from various families: sulfonamides (SMX, SDZ, SMZ), tetracyclines (TET, OTC), quinolones (OFLO, FLU, CPIX), macrolides (ERY), nitrofurans and phenicols (FF) [15,23,47]. Apart from SPE-based approach, various sample preparation processes have been reported, including liquid-liquid extraction (LLE) with or without sonication or microwave assistance (Norambuena et al., 2013; Prat et al., 2006). In a general way, acetonitrile appears as the solvent of choice for the extraction of these molecules.

In most of the studies devoted to drugs used in fish farming, analytes are separated using liquid chromatography. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) is the most widely applied technique to detect veterinary drugs with great accuracy and reliability [48]; it is nevertheless more and more replaced by UPLC (Ultrahigh Performance Liquid Chromatography), which uses a new generation of columns filled with small particles of hybrid material (diameter at the μm scale) and operates with a much higher column pressure (up to 15,000 psi) than HPLC. UPLC considerably reduces runtime and thus increases sample throughput; it performs also much better in terms of resolution, sensitivity, and separation efficiency; it is almost always coupled with a mass spectrometer (see below). Li et al. developed a rapid, sensitive, and reliable UPLC-MS/MS method for the determination of 21 antibiotics belonging to 7 classes in different wastewater matrixes (Li et al., 2009). Yu et al. reported a selective and sensitive method to measure 11 antibiotics in water by UPLC-MS/MS; it was successfully used to identify ofloxacin in wastewater and sludge samples [49]. Dinh et al. used UPLC-MS/MS to find different veterinary drugs including furazolidone, with a limit of detection of 1.5-3 μg/kg for the later [5]. Whatever the chromatographic system (HPLC or UPLC), most of the studies were conducted using reverse phase chromatography. Many brands and geometries were tested but at the end the retained columns are almost all C18-types. The mobile phase is almost always a very classical one in the following type of configuration: a binary gradient made of an aqueous phase (ultrapure water) and an organic one (ACN or MeOH), both acidified with a small organic acid (acid formic, acetic, trifluoroacetic…) generally at 0.1%. Among all the studies listed in Table 2, the only one that uses a non C18 stationary phase (phenylpropylsilane phase) is that by Norambuena et al., devoted to the analysis of oxytetracycline, florfenicol, flumequine and oxolinic acid in marine sediments (Norambuena et al., 2013). In this work, HPLC was equipped with a PDA (photodiode array detector). HPLC with PDA detection was also used for the detection of florfenicol in water by Zhang et al. and that of sulfonamide residues by Won et al. [50,51]. HPLC-PDA has been also reported for the detection of sulfadiazine in South-Korean marine products, although SDZ was only identified in 2 of the 10 samples analyzed [51]. Han et al. reported a combination of UVD (UV detector) and FLD (fluorescence detector) for the analysis of tetracyclines in feeds [48]. Studies reporting the detection of flumequine and oxolinic acid by HPLC-FLD in sediments, soils and various types of water have been also reported [25]. In a general way “classical” HPLC detectors tend to be gradually replaced by mass spectrometers, which are today recognized as the best detectors in terms of sensitivity, specificity and selectivity.

In almost all of the studies conducted using LC-MS coupling, the liquid chromatograph (HPLC or UPLC) is coupled with a triple quadrupole (TQ) operated in the MRM (multiple reaction monitoring) mode on two transitions. Tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) is preferred to simple MS as it strongly reduces the risk of false negatives when performing analysis of complex matrices (Bouchonnet, 2013). Hybrid mass spectrometers associating a quadrupole, a collision cell, and an ion trap have been also reported; their principle of operation is quite similar to that of TQs except that the ion trap permits ion accumulation before detection [47,49]. Among all the studies listed in Table 2, only that by Goessens et al. refers to a high-resolution mass spectrometer (Orbitrap™), which has been employed to analyze 46 antimicrobial drug residues including sulfonamides, tetracyclines, quinolones, macrolides, nitrofurans and phenicols in aquatic matrices [23]. Since it allows the differentiation of isobaric ions, high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) constitutes a tool of choice for structural elucidation of metabolites and by-products; it also significantly reduces interferences during routine analysis of very complex matrices. The use of MS/MS and/or HRMS enables the development and validation of multi-residue methods able to detect and quantify many molecules in one unique run. Even if the number of analytes remains limited in comparison with methods reported for pesticide residue dosages (hundreds of analytes), some of the methods reported for the analysis of veterinary antibiotics allows the simultaneous detection of tens of drugs. For instance, Gros et al. developed a LC-MS/MS method for the one run detection of 73 pharmaceuticals including tetracycline, oxytetracycline, sulfadiazine, sulfamethoxazole, ofloxacin, flumequine, ciprofloxacin and erythromycin in river water and WWTP influent and effluent while a LC-HRMS was developed by Goessens et al. for the analysis of 46 antimicrobial drug residues including sulfonamides, tetracyclines, quinolones, macrolides, nitrofurans and phenicols in aquatic matrices [23].

A few analytical approaches were developed apart from traditional separative processes such as liquid chromatography. For example, an aptaprobe was used for the detection of sulfadimethoxine; it simply and conveniently detects SDM with accuracy in the range of 94.2-113% in seawater and 104-118% in fish [52]. A dichromatic label-free aptasensor detects SDM presence through fluorescent emission and color changes of gold nanoparticles. This aptasensor can be applied to the rapid detection in fish and water samples with accuracies between 99.2 and 102% for fish, 99.5 and 100.5% for water [53]. Almeida et al. also developed a new low-cost plastic membrane electrode that detects low concentrations of SDM in aquaculture waters. To test this device, sulfadimethoxine was added to aquaculture waters and the results showed a good agreement between added and measured drug amounts with recoveries ranging from 96.8% to 101%, with a relative error between -0.7% and 3.5%, which suggests that it constitutes a good method that could be extended to the determination of other pharmaceuticals in water [54].

Treatment Processes

Once they reach the environment, micropollutants are subjected to three main degradation processes: biodegradation, hydrolysis, and photolysis [8]. Due to their own antibacterial activity, antibiotics are poorly or not degraded by natural biotic processes. Chemical and physical processes – natural or industrial – can be considered as a better option to remove these refractory veterinary drugs. As we will see below, many treatments have been considered for their degradation and/or removal from aqueous media; they include membrane anodic Fenton, advanced oxidation processes, heterogeneous photocatalysis, and electrocoagulation [55]. Table 3 lists some treatments applied for the removal of veterinary pharmaceuticals considered individually.

Table 3: Various treatment methods for the removing of the veterinary drugs mainly used in fish farming from aqueous media

|

Treatment process

|

Drug |

Reference

|

| H2O2/Fe + UV treatment |

Tetracycline, oxytetracycline |

Zhao et al., 2020 |

| CaO2/UV |

Florfenicole |

Zheng et al., 2019 |

| Photodegradation with TiO2, |

Sulfadiazine |

He et al., 2016 |

| Batch culture of c. vulgaris microalgae |

Sulfamethoxazole |

Y.-Y. Peng et al., 2020 |

| Ozonation |

Sulfadimethoxine

Erythromycin |

A.Y.-C. Lin et al., 2009 |

| Heterogeneous photocatalysis with suspended TiO2 |

Oxolinic acid |

Giraldo et al., 2010 |

| Ultraviolet / peroxydisulfate |

Ofloxacin |

Zhu et al., 2020 |

| Reverse osmosis membrane |

Ciprofloxacin |

Alonso et al., 2018 |

| Electrochemical cathode degradation, Magnetic biochar |

Furazolidone |

Kong et al., 2015; Gurav et al., 2020 |

Using a pilot drinking water treatment plant, Vieno et al. observed the elimination of some pharmaceuticals with a process consisting in ferric salt coagulation, rapid sand filtration, ozonation, and two-stage granular activated carbon filtration. Most pharmaceuticals ceased to be quantifiable at the end of ozonation; only ciprofloxacin passed all treatment steps almost unaffected [56]. No treatment appears as a universal solution at this day. For instance, classical wastewater treatments are known to be inefficient for the elimination of sulfonamides [47]. Tetracycline is hard to degrade using conventional wastewater treatments such as activated sludge, which might be due to tetracyclines’ strong hydrophilic properties related to their stable naphthalene ring structure (Zhao et al., 2020). The biological degradation of oxytetracycline is limited due to its broad-spectrum antimicrobial properties, which are considered responsible for the development of antibiotic resistance genes in the environment (Xie et al., 2016). OTC fails to be degraded into non-toxic transformation products by most abiotic processes; therefore sonocatalytic degradation has been proposed to form less toxic intermediates [57].

Most of the alternative approaches for the removal of the most resistant molecules are based on photocatalytic or electrochemical approaches. For instance, sulfamethoxazole is not efficiently removed in conventional wastewater treatment plants [47] but it is susceptible to photodegradation in aqueous solutions along several pathways [58]. UV-photolysis appears as a treatment of choice for many micropollutants, especially in the presence of a catalyst that increases both the kinetics and yields of the degradation reaction. UV-irradiation induces the formation of hydroxyl radicals from water and dissolved oxygen; these highly reactive radicals are responsible for the oxidation of micropollutants. The addition of hydrogen peroxide, alone or with a metal has been frequently reported. Zhao et al. evaluated the effect of H2O2/Fe addition to the UV treatment of tetracycline. They found out that optimum concentrations of H2O2 (0.5 mM) and Fe(II) (0.05 mM) promote the degradation of TET. Also, a higher pH level facilitated the UV-attenuation of TET (Zhao et al., 2020) while a lower pH helped its degradation under ozonation conditions. Ming Zheng et al. utilized CaO2/UV as an advanced oxidation process to remove FF and other active pharmaceutical compounds from wastewater. CaO2 is considered as the “solid form” of H2O2 with an advantage of being more stable than H2O2 in presence of base or catalyst. CaO2 can produce .OH And O2. radicals and oxidize complex chemical compounds. The highest removal of FF happened at 0.1 g.L-1 of CaO2. The addition of CaO2 also allows reducing the irradiation time and so decreasing the consumption of energy [31]. Titanium oxide appears as a widely used photocatalyst for the removal of pharmaceuticals. UV-irradiation with TiO2 removed 99% of sulfadiazine under the following conditions: initial concentrations of sulfadiazine at 5.0 mg/L and TiO2 at 0.08 g/L, pH = 7, radiation intensity of 1000 μw/cm2 and reaction time of 50 min [59]. SDZ can be also effectively degraded using gamma irradiation, the elimination efficiency being improved under acidic conditions [60]. Degradation of sulfamethoxazole under ultraviolet light with TiO2 reached 96%. TiO2 is the most suitable catalyst due to its stability, non-toxicity, and high catalytic activity [59]. Oxolinic acid was degraded using heterogeneous photocatalysis with titanium dioxide suspended on particles. After 30 min under optimal conditions both the substrate and the microbial activity were eliminated [61] and the residual byproducts did not show antibacterial activity [62]. Organic matter can both hinder and activate the photodegradation. For instance, oxolinic acid persistence is lower in ultrapure water than in environmental water, especially in the presence of high salinity values. The presence of organic matter can decrease the photodegradation rate in freshwater by acting as a light filter and hydroxyl radicals scavenger [63]. An ultraviolet/peroxydisulfate system was reported for the degradation of ofloxacin in synthetic seawater and in synthetic marine aquaculture water; the global toxicity (including toxicities of reagents and by-products) induced by such a process is lower than that induced with traditional approaches using NaClO [64]. Traditional removal processes only based on chemical reactions tend to be replaced by the so-called AOPs (advance oxidation processes) but some of them remains in use. For instance, [21] demonstrated that sulfadimethoxine can be removed by potassium permanganate in water. The degradation is affected by the pH of the solution and a higher temperature is also beneficial for the removal [21]. The use of zero-valent iron-activated persulfate has been developed to remediate antibiotic-contaminated wastewater since it removes 69% and 74% of SDM from filtered and unfiltered discharge water, respectively [65]. It has to be kept in mind that in a general way catalysis is hardly applied to complex matrices (water containing high levels of dissolved organic matter for instance) as it becomes quite inefficient in the presence of large amounts of organic and inorganic species. Furthermore, altering the pH when necessary can be very costly.

Electro-Fenton technology is also an advanced oxidation process that produces hydroxyl radicals to degrade refractory pollutants. However, this process may be inefficient due to the high dissociation energy of some chemical bonds, such as C-F in florfenicol. On the other hand, UV light has shown to be capable of cleaving such bonds, and the combination of Electro-Fenton with UV could be an efficient technology. Jiang et al. coupled the photoelectrochemical reaction in a sequential filtration system to degrade and mineralize FF. Their study revealed 78.1 ± 9.1% mineralization of FF at a low concentration of 14 µM [66]. Various technologies have been studied to remove furazolidone from wastewater samples; among them, Kong et al. used an electrochemical system to degrade FUR in a cathode compartment. Their study evaluated the effect of different cathode potentials, initial antibiotic concentration, and cathode buffer solution on FUR degradation. Different cathode potentials resulted in different degradation products, and different buffer solutions and initial concentrations of furazolidone had just an obvious effect on its removal efficiency [67].

Ozonation has also been reported as a powerful tool for micropollutants abatement. For example, it allowed the degradation of tetracycline at 99.5% with 40% of mineralization (C. Wang et al., 2020). Sulfadimethoxine showed to be completely removed from water by ozone bubbling within 20 minutes; this strong efficiency was partially explained by the presence of one or several aromatic rings on which the O3 molecule can fix itself before hydrolysis and/or ring opening [68]. Ozonation at an application rate of 0.17 g O3/min was able to remove some antibiotics in about 20 min, although the degradation of erythromycin was slower, and more effective at a high pH or with H2O2 addition [68].

As ciprofloxacin is particularly refractory to conventional wastewater treatments, special attention has been paid to its removal using alternative processes. Reverse osmosis was successfully tested for the removal (99.96% removal) of CPIX in seawater [69]. Additionally, ciprofloxacin removal by electrosorption has been successfully demonstrated using graphite felt electrodes [70].

Finally, and despite their microbial activity, some veterinary drugs were submitted to treatments involving biological processes. In two sewage treatment plants in Guangzhou, more than 85% of ofloxacin was removed in the effluents after activated sludge [71]. A novel microalgae biofilm membrane photobioreactor (MBMP) was developed for the cultivation of microalgae and the removal of sulfonamides from residual wastewater of aquaculture. The reduction of sulfadiazine in the MBMP during its stable operation was up to 61-79.2%. It can be considered that the performance of the MBMP is higher than the one achieved by traditional batch cultivation [18]. The removal of sulfamethoxazole by a batch culture of microalgae c. vulgaris was 34.07% after 12 days of concentration in marine aquaculture wastewater (against 3.33% without microalgae). Gurav et al. used a magnetic biochar to remove furazolidone from wastewater; they showed that the magnetic biochar had a higher surface area as compared to normal biochar, and possessed a much better removal efficiency [27].

Conclusion

Aquaculture is a booming industry, which by necessity uses drugs to prevent and treat diseases in fish farms. The current literature has been mainly focused on the possible adverse effects on human health due to the possible remnants of these drugs in fish. In recent years, the presence of drugs in environmental matrices has become more evident but the effects of aquaculture waste on the environment have been poorly documented. Thanks to the continuous improvement of analytical methods, it is now possible to successfully determine veterinary pharmaceuticals at trace amounts in complex matrices. The most common analytical processes rely on solid phase extraction and liquid chromatography – HPLC or UHPLC – coupled with mass spectrometry. Current efforts are aimed at developing multiresidue methods for the simultaneous analysis of various drugs from different families. In any case, the literature directed specifically to the water discarded by aquaculture is very scarce. Although most of the analytical methods are focused on separative processes, recent ventures successfully tested aptasensors and aptaprobes to quickly and efficiently measure low concentrations of antibiotics in water.

Waste from agriculture and aquaculture usually reaches the environment directly, without being previously treated. Currently, there is more knowledge about the toxic effects of pharmaceuticals in humans and animals than about their environmental impact. A good evaluation of their potential ecotoxicological impact should consider factors such as the presence of sediments, the stability of water and other substances with which the drugs can interact since all these parameters may affect the final result of the investigations [72]. It is known that contamination by antibiotics includes the development of resistance in the aquatic pathogens, direct toxicity to microflora and microfauna, and even possible risks to human health due to the consumption of non-target contaminated benthic fauna [73]. For this reason, ways to treat or eliminate these pollutants are still under investigation given that conventional wastewater treatment plants are not fully efficient – and sometimes quasi inefficient – for their removal. The antimicrobial activity of pharmaceuticals makes their treatment through biotic processes difficult and advanced oxidation processes appear as a tool of choice for their removal. Photocatalysis and electrochemistry are not really viable on a wide scale to this day but ozonation and UV/H2O2 oxidation are much more applicable. In a general way, it is of first importance to mitigate the ecotoxicological risks associated with aquaculture waste released into the sea, by (i) selecting the proper veterinary drugs, (ii) limiting the amount of waste release from fish farming and (iii) setting efficient solutions for the removal of pharmaceuticals once or before they reach the environment [74-77].

References

- FAO (2020) The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020. FAO.

- Castilla-Fernández D, Moreno-González D, Bouza M, Saez-Gómez A, Ballesteros E, et al. (2021) Assessment of a specific sample cleanup for the multiresidue determination of veterinary drugs and pesticides in salmon using liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Food Control 130: 108311.

- Chokmangmeepisarn P, Thangsunan P, Kayansamruaj P, Rodkhum C (2021) Resistome characterization of Flavobacterium columnare isolated from freshwater cultured Asian sea bass (Lates calcarifer) revealed diversity of quinolone resistance associated genes. Aquaculture 544: 737149.

- Pastor-Belda M, Campillo N, Arroyo-Manzanares N, Hernández-Córdoba M, Viñas P (2020) Determination of amphenicol antibiotics and their glucuronide metabolites in urine samples using liquid chromatography with quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography B 1146: 122122.

- Dinh QT, Munoz G, Vo Duy S, Tien Do D, Bayen S, et al. (2020) Analysis of sulfonamides, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, triphenylmethane dyes and other veterinary drug residues in cultured and wild seafood sold in Montreal, Canada. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 94: 103630.

- Du J, Li X, Tian L, Li J, Wang C, et al. (2021) Determination of macrolides in animal tissues and egg by multi-walled carbon nanotube-based dispersive solid-phase extraction and ultra-high performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Food Chemistry 365: 130502.

- Lulijwa R, Rupia EJ, Alfaro AC (2019) Antibiotic use in aquaculture, policies and regulation, health and environmental risks: A review of the top 15 major producers. Reviews in Aquaculture 12: 640-663.

- Leal JF, Santos EBH, Esteves VI (2018) Oxytetracycline in intensive aquaculture: Water quality during and after its administration, environmental fate, toxicity and bacterial resistance. Reviews in Aquaculture 11: 4.

- Archundia D, Duwig C, Lehembre F, Chiron S, Morel MC, et al. (2017). Antibiotic pollution in the Katari subcatchment of the Titicaca Lake: Major transformation products and occurrence of resistance genes. Science of The Total Environment 576: 671-682.

- Krzeminski P, Tomei MC, Karaolia P, Langenhoff A, Almeida CMR, et al. (2019) Performance of secondary wastewater treatment methods for the removal of contaminants of emerging concern implicated in crop uptake and antibiotic resistance spread: A review. Science of The Total Environment 648: 1052-1081. [crossref]

- Barreto FM, da Silva MR, Braga PAC, Bragotto APA, Hisano H, et al. (2018) Evaluation of the leaching of florfenicol from coated medicated fish feed into water. Environmental Pollution 242: 1245-1252. [crossref]

- Kim W, Lee Y, Kim SD (2017) Developing and applying a site-specific multimedia fate model to address ecological risk of oxytetracycline discharged with aquaculture effluent in coastal waters off Jangheung, Korea. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 145: 221-226. [crossref]

- Chopra I, Roberts M (2001) Tetracycline Antibiotics: Mode of Action, Applications, Molecular Biology, and Epidemiology of Bacterial Resistance. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 65: 232-260. [crossref]

- Lee PT, Liao ZH, Huang HT, Chuang CY, Nan FH (2020) β-glucan alleviates the immunosuppressive effects of oxytetracycline on the non-specific immune responses and resistance against Vibrio alginolyticus infection in Epinephelus fuscoguttatus × Epinephelus lanceolatus hybrids. Fish & Shellfish Immunology 100: 467-475. [crossref]

- Li Z, Qi W, Feng Y, Liu Y, Ebrahim S, et al. (2019) Degradation mechanisms of oxytetracycline in the environment. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 18: 1953-1960.

- Grave K, Hansen MK, Kruse H, Bangen M, Kristoffersen AB (2008) Prescription of antimicrobial drugs in Norwegian aquaculture with an emphasis on “new” fish species. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 83: 156-169. [crossref]

- Wang Y, Li X, Fu Y, Chen Y, Wang Y, et al. (2020) Association of florfenicol residues with the abundance of oxazolidinone resistance genes in livestock manures. Journal of Hazardous Materials 399: 123059.

- Peng YY, Gao F, Yang HL, Wu HWJ, Li C, et al. (2020) Simultaneous removal of nutrient and sulfonamides from marine aquaculture wastewater by concentrated and attached cultivation of Chlorella vulgaris in an algal biofilm membrane photobioreactor (BF-MPBR). Science of The Total Environment 725: 138524. [crossref]

- Al-Ansari MM, Benabdelkamel H, Al-Humaid L (2021) Degradation of sulfadiazine and electricity generation from wastewater using Bacillus subtilis EL06 integrated with an open circuit system. Chemosphere 276: 130145. [crossref]

- Cheng L, Chen Y, Zheng YY, Zhan Y, Zhao H, et al. (2017) Bioaccumulation of sulfadiazine and subsequent enzymatic activities in Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis). Marine Pollution Bulletin 121: 176-182. [crossref]

- Zhuang J, Wang S, Tan Y, Xiao R, Chen J, et al. (2019) Degradation of sulfadimethoxine by permanganate in aquatic environment: Influence factors, intermediate products and theoretical study. Science of the Total Environment 671: 705-713. [crossref]

- (2020) Oxolinic acid. National Center for Biotechnology Information.

- Goessens T, Huysman S, De Troyer N, Deknock A, Goethals P, et al. (2020) Multi-class analysis of 46 antimicrobial drug residues in pond water using UHPLC-Orbitrap-HRMS and application to freshwater ponds in Flanders, Belgium. Talanta 220: 121326.

- Barmpa A, Frousiou O, Kalogiannis S, Perdih F, Turel I, et al. (2018). Manganese (II) complexes of the quinolone family member flumequine: Structure, antimicrobial activity and affinity for albumins and calf-thymus DNA. Polyhedron 145: 166-175.

- Qi, Y, Qu R, Liu J, Chen J, Al-Basher G, et al. (2019) Oxidation of flumequine in aqueous solution by UV-activated peroxymonosulfate: Kinetics, water matrix effects, degradation products and reaction pathways. Chemosphere 237: 124484.

- Yanong RPE (2019) Use of Antibiotics in Ornamental Fish Aquaculture. Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences.

- Gurav R, Bhatia SK, Choi TR, Park YL, Park JY, et al. (2020) Treatment of furazolidone contaminated water using banana pseudostem biochar engineered with facile synthesized magnetic nanocomposites. Bioresource Technology 297: 122472. [crossref]

- Sreejith S, Shajahan S, Prathiush PR, Anjana VM, Viswanathan A, et al. (2020) Healthy broilers disseminate antibiotic resistance in response to tetracycline input in feed concentrates. Microbial Pathogenesis 149: 104562. [crossref]

- Magdaleno A, Carusso S, Moretton J (2017) Toxicity and Genotoxicity of Three Antimicrobials Commonly Used in Veterinary Medicine. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 99: 315-320. [crossref]

- Zhang Y, Zhang X, Guo R, Zhang Q, Cao X, et al. (2020) Effects of florfenicol on growth, photosynthesis and antioxidant system of the non-target organism Isochrysis galbana. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology 233: 108764. [crossref]

- Zheng M, Daniels KD, Park M, Nienhauser AB, Clevenger EC, et al. (2019) Attenuation of pharmaceutically active compounds in aqueous solution by UV/CaO2 process: Influencing factors, degradation mechanism and pathways. Water Research 164: 114922.

- Freitas EC, Rocha O, Espíndola ELG (2018) Effects of florfenicol and oxytetracycline on the tropical cladoceran Ceriodaphnia silvestrii: A mixture toxicity approach to predict the potential risks of antimicrobials for zooplankton. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 162: 663-672.

- Hu D, Meng F, Cui Y, Yin M, Ning H, et al. (2020) Growth and cardiovascular development are repressed by florfenicol exposure in early chicken embryos. Poultry Science 99: 2736-2745. [crossref]

- Guilhermino L, Luís R Vieira, Diogo Ribeiro, Ana Sofia Tavares, Vera Cardoso (2017) Uptake and effects of the antimicrobial florfenicol, microplastics and their mixtures on freshwater exotic invasive bivalve Corbicula fluminea. The Science of the Total Environment 622-623: 1131-1142. [crossref]

- Duan Y, Deng L, Shi Z, Liu X, Zeng H, et al. (2020) Efficient sulfadiazine degradation via in-situ epitaxial grow of Graphitic Carbon Nitride (g-C3N4) on carbon dots heterostructures under visible light irradiation: Synthesis, mechanisms and toxicity evaluation. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 561: 696-707.

- Lin T, Yu S, Chen Y, Chen W (2014) Integrated biomarker responses in zebrafish exposed to sulfonamides. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 38: 444-452. [crossref]

- Li Z, Chang Q, Li S, Gao M, She Z, et al. (2017) Impact of sulfadiazine on performance and microbial community of a sequencing batch biofilm reactor treating synthetic mariculture wastewater. Bioresource Technology 235: 122-130.

- Chen Y, Zhou JL, Cheng L, Zheng YY, Xu J (2017) Sediment and salinity effects on the bioaccumulation of sulfamethoxazole in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Chemosphere 180: 467-475. [crossref]

- Borecka M, Białk-Bielińska A, Haliński ŁP, Pazdro K, Stepnowski P, et al. (2016) The influence of salinity on the toxicity of selected sulfonamides and trimethoprim towards the green algae Chlorella vulgaris. Journal of Hazardous Materials 308: 179-186. [crossref]

- Tkaczyk A, Bownik A, Dudka J, Kowal K, Ślaska B (2021) Daphnia magna model in the toxicity assessment of pharmaceuticals: A review. Science of The Total Environment 763: 143038. [crossref]

- Sun Y, Zhang L, Zhang X, Chen T, Dong D, et al. (2020) Enhanced bioaccumulation of fluorinated antibiotics in crucian carp (Carassius carassius): Influence of fluorine substituent. Science of The Total Environment, 748, 141567. [crossref]

- De Liguoro M, Maraj S, Merlanti R (2019) Transgenerational toxicity of flumequine over four generations of Daphnia magna. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 169: 814-821. [crossref]

- Sendra M, Moreno-Garrido I, Blasco J, Araújo CVM (2018) Effect of erythromycin and modulating effect of CeO2 NPs on the toxicity exerted by the antibiotic on the microalgae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Environmental Pollution 242: 357-366.

- Hua T, Li S, Li F, Ondon BS, Liu Y, et al. (2019) Degradation performance and microbial community analysis of microbial electrolysis cells for erythromycin wastewater treatment. Biochemical Engineering Journal 146: 1-9.

- Lewkowski J, Rogacz D, Rychter P (2019) Hazardous ecotoxicological impact of two commonly used nitrofuran-derived antibacterial drugs: Furazolidone and nitrofurantoin. Chemosphere 222: 381-390. [crossref]

- Sun Y, Waterhouse GIN, Xu L, Qiao X, Xu Z (2020) Three-dimensional electrochemical sensor with covalent organic framework decorated carbon nanotubes signal amplification for the detection of furazolidone. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 321: 128501.

- García-Galán MJ, Díaz-Cruz MS, Barceló D (2011) Occurrence of sulfonamide residues along the Ebro river basin: Removal in wastewater treatment plants and environmental impact assessment. Environment International 37: 462-473. [crossref]

- Han J, Jiang D, Chen T, Jin W, Wu Z, et al. (2020) Simultaneous determination of olaquindox, oxytetracycline and chlorotetracycline in feeds by high performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet and fluorescence detection adopting online synchronous derivation and separation. Journal of Chromatography B 1152: 122253. [crossref]

- Yu R, Chen L, Shen R, Li P, Shi N (2020) Quantification of ultratrace levels of fluoroquinolones in wastewater by molecularly imprinted solid phase extraction and liquid chromatography triple quadrupole mass. Environmental Technology & Innovation 19: 100919.

- Zhang Q, Guo R, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Mostafizur RMD, et al. (2020) Study on florfenicol-contained feeds delivery in Dicentrarchus labrax seawater recirculating and flowing aquaculture systems. Aquaculture 526: 735326.

- Won SY, Lee CH, Chang HS, Kim SO, Lee SH, et al. (2011) Monitoring of 14 sulfonamide antibiotic residues in marine products using HPLC-PDA and LC-MS/MS. Food Control 22: 1101-1107.

- Chen XX, Lin ZZ, Hong CY, Yao QH, Huang ZY (2020) A dichromatic label-free aptasensor for sulfadimethoxine detection in fish and water based on AuNPs color and fluorescent dyeing of double-stranded DNA with SYBR Green I. Food Chemistry 309: 125712. [crossref]

- Chen XX, Lin ZZ, Yao QH, Huang ZY (2020) A practical aptaprobe for sulfadimethoxine residue detection in water and fish based on the fluorescence quenching of CdTe QDs by poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride). Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 91: 103526.

- Almeida SAA, Montenegro MCBSM, Sales MGF (2013) New and low cost plastic membrane electrode with low detection limits for sulfadimethoxine determination in aquaculture waters. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry 709: 39-45.

- Nariyan E, Aghababaei A, Sillanpää M (2017) Removal of pharmaceutical from water with an electrocoagulation process; effect of various parameters and studies of isotherm and kinetic. Separation and Purification Technology 188: 266-281.

- Vieno NM, Härkki H, Tuhkanen T, Kronberg L (2007) Occurrence of pharmaceuticals in river water and their elimination in a pilot-scale drinking water treatment plant. Environmental Science & Technology, 41: 5077-5084. [crossref]

- Kumar Subramani A, Rani P, Wang P.-H, Chen B.-Y, Mohan S et al. (2019) Performance assessment of the combined treatment for oxytetracycline antibiotics removal by sonocatalysis and degradation using Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 7: 103215.

- Moore DE (1998) Mechanisms of photosensitization by phototoxic drugs. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis 422: 165-173.

- He Z, Cheng X, Kyzas GZ, Fu J (2016) Pharmaceuticals pollution of aquaculture and its management in China. Journal of Molecular Liquids 223: 781-789.

- Guo Z, Zhou F, Zhao Y, Zhang C, Liu F, et al. (2012) Gamma irradiation-induced sulfadiazine degradation and its removal mechanisms. Chemical Engineering Journal 191: 256-262.

- Giraldo AL, Peñuela GA, Torres-Palma RA, Pino NJ, Palominos RA, et al. (2010) Degradation of the antibiotic oxolinic acid by photocatalysis with TiO2 in suspension. Water Research 44: 5158-5167. [crossref]

- Pereira JHOS, Reis AC, Queirós D, Nunes OC, Borges MT, et al. (2013) Insights into solar TiO2-assisted photocatalytic oxidation of two antibiotics employed in aquatic animal production, oxolinic acid and oxytetracycline. Science of The Total Environment 463-464: 274-283. [crossref]

- dos Louros VL, Silva CP, Nadais H, Otero M, Esteves VI, et al. (2020) Oxolinic acid in aquaculture waters: Can natural attenuation through photodegradation decrease its concentration? Science of The Total Environment 749: 141661. [crossref]

- Zhu Y, Wei M, Pan Z, Li L, Liang J, et al. (2020) Ultraviolet/peroxydisulfate degradation of ofloxacin in seawater: Kinetics, mechanism and toxicity of products. Science of The Total Environment 705: 135960. [crossref]

- Chokejaroenrat C, Sakulthaew C, Angkaew A, Satapanajaru T, Poapolathep A, et al. (2019) Remediating sulfadimethoxine-contaminated aquaculture wastewater using ZVI-activated persulfate in a flow-through system. Aquacultural Engineering 84: 99-105.

- Wen-Li J, Yang-Cheng D, Muhammad Rizwan H, Han JL, Liang B, et al. (2019) A novel TiO2/graphite felt photoanode assisted electro-Fenton catalytic membrane process for sequential degradation of antibiotic florfenicol and elimination of its antibacterial activity. Chemical Engineering Journal 391: 123503.

- Kong D, Liang B, Yun H, Ma J, Li Z, et al. (2015) Electrochemical degradation of nitrofurans furazolidone by cathode: Characterization, pathway and antibacterial activity analysis. Chemical Engineering Journal 262: 1244-1251.

- Lin AYC, Lin CF, Chiou JM, Hong PKA (2009) O3 and O3/H2O2 treatment of sulfonamide and macrolide antibiotics in wastewater. Journal of Hazardous Materials 171: 452-458. [crossref]

- Alonso JJS, El Kori N, Melián-Martel N, Del Río-Gamero B (2018) Removal of ciprofloxacin from seawater by reverse osmosis. Journal of Environmental Management 217: 337-345. [crossref]

- Divyapriya G, Mohanalakshmi J, kumar KV, Nambi IM (2020) Electro-enhanced adsorptive removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous solution on graphite felt. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 8: 104299.

- Peng X, Wang Z, Kuang W, Tan J, Li K (2006) A preliminary study on the occurrence and behavior of sulfonamides, ofloxacin and chloramphenicol antimicrobials in wastewaters of two sewage treatment plants in Guangzhou, China. Science of The Total Environment 371: 314-322. [crossref]

- Isidori M, Lavorgna M, Nardelli A, Pascarella L, Parrella A (2005) Toxic and genotoxic evaluation of six antibiotics on non-target organisms. Science of The Total Environment 346: 87-98.

- Rigos G, Nengas I, Alexis M, Troisi GM (2004) Potential drug (oxytetracycline and oxolinic acid) pollution from Mediterranean sparid fish farms. Aquatic Toxicology 69: 281-288. [crossref]

- Barmpa A, Frousiou O, Kalogiannis S, Perdih F, Turel I, et al. (2018). Manganese (II) complexes of the quinolone family member flumequine: Structure, antimicrobial activity and affinity for albumins and calf-thymus DNA. Polyhedron 145: 166-175.

- Commission Regulation (EU) No 37/2010 of 22 December 2009 on pharmacologically active substances and their classification regarding maximum residue limits in foodstuffs of animal origin.

- Drzymała J, Kalka J (2020) Ecotoxic interactions between pharmaceuticals in mixtures: Diclofenac and sulfamethoxazole. Chemosphere 259: 127407. [crossref]

- Guo H, Li Z, Lin S, Li D, Jiang N, et al. (2021) Multi-catalysis induced by pulsed discharge plasma coupled with graphene-Fe3O4 nanocomposites for efficient removal of ofloxacin in water: Mechanism, degradation pathway and potential toxicity. Chemosphere 265: 129089.