DOI: 10.31038/IDT.2021211

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic is challenging the world affecting heavily people’s mental health. The psychological consequences of this pandemic include depressive symptoms, anxiety, worry, and loneliness due to home confinement during lockdowns. A good sleep quality is essential to face this stressing condition, nevertheless one of the first complaint reported by the population, soon after the onset of the pandemic in China, was sleep disturbance. A large amount of work has now evidenced that sleep disturbance related to the pandemic affects more than one third of the population of both sexes across all involved countries. Very young people and the elderly are particularly affected by this problem. Anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder are strictly associated with sleep disturbance. As risk of suicide has increased during the pandemic, insomnia has also been proven to be a cause of suicidal ideation. The strict confinement measures adopted by most countries to tackle the outbreak have also contribute to create a sense of disorientation among people and to change their sleep habits. Poor sleep quality reduces daytime functioning and mental resources. These effects can have dramatic consequences in the general public, but more specifically in health care workers, now facing the most stressful experience right in the center of this catastrophe. In this article we review available evidence on the impact of COVID-19 on people’s quality of sleep and on the occurrence of sleep disturbance in different subsets of the population, analyzing also risk factors determining insomnia and the consequences of this dreadful condition.

Introduction

Outbreaks of infectious diseases, along with control measures to limit the spread of pathogens, profoundly affect people’s mental health and well-being [1]. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, is not only challenging worldwide health care systems and governments, but also the general public, concerned by the risk of being infected, distressed by the implementation of mobility restrictions and worried about future insecurity. These concerns collaborate to impair sleep and, due to the role of sleep-in emotional stabilization, this impairment can further weaken people’s mental health status [2]. The psychological consequences of this pandemic have been compared to those following natural disasters, as in both cases individuals are forced to change their everyday and work practices [3]. In both situations psychological stress can cause relevant sleep disturbance, however until the onset of SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in December2019, our experience on pandemics, at least in developed countries, was limited.

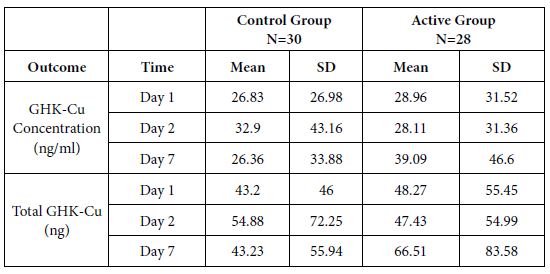

Sleep quality indicates a satisfying sleep, including aspects of sleep initiation, sleep maintenance, sleep quantity, and refreshment upon awakening. Sleep disturbance encompasses disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep, which have a great impact on public health affecting millions of people worldwide [4]. Insomnia, the most common sleep complaint, is defined as a difficulty in initiating and maintaining sleep or an overall worsened quality of sleep. A good sleep quality is important to maintain physical activity, to preserve energy levels and to sustain mental health. The lack of sleep, or sleep disruption, negatively affects the daily physical functioning and mental status, causing depression and anxiety, thus reducing the quality of life [5]. In addition, sleep disorders have been associated with a variety of diseases including diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and stroke [5]. A good quality of sleep, is particularly relevant when facing difficult and challenging situations such as the ongoing pandemic. Though, one of the main consequences of the psychological stress affecting the population after the pandemic abruptly started, were insomnia and sleep disruption. The occurrence of sleep disturbance further worsens the general state of anxiety and stress among the population so that a vicious circle, difficult to break, is generated. The consequences of this vicious circle can be devastating. A remarkable study has shown that anxiety about COVID-19 positively correlated with insomnia severity and suicidal ideation. Analysis revealed that the statistical association between pandemic fears and suicidal thinking was fully accounted for by insomnia severity [6]. To make the picture worse, some authors have also hypothesized a possible correlation between sleep loss and risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection, as sleep loss negatively impacts the immune responses by disrupting its circadian rhythmicity [7]. After one year from its onset, this pandemic, first believed to be transient, is still ongoing and a great body of evidence is now available on its effects on sleep quality in the general population and in specific categories, such as healthcare workers, who more than others, have to deal with the burden of the disease. In this article we review available evidence on the impact of COVID-19 on people’s quality of sleep and on the occurrence of sleep disturbance in different subsets of the population, analyzing also risk factors determining insomnia and the consequences of this dreadful condition (Table 1).

Table 1: Issues related to the impact of COVID-19 on sleep quality that have been addressed by the currently available literature.

|

References

|

| Prevalence of sleep disorders and symptoms of insomnia in the general public |

9,10,14,15,18,20,22

|

| Prevalence of sleep disorders in subsets of population, mainly health care workers |

9, 54, 65,66,67,68

|

| Effects of home confinement on sleep habits and sleep disorders |

25, 29, 30,31,32,33

|

| Individual factors influencing the intensity and the type of the sleep disorders |

9, 10,11,18, 20,22,37,40

|

| General factors influencing the occurrence of sleep disorders (e.g. physical activity) |

31, 43,44

|

| Differences in sleep quality and habits across countries |

9, 29, 38

|

| Change in the occurrence of sleep disorders over time (through different stages of the pandemic) |

46,47,48

|

Only main references are cited

Sleep Disturbance in the General Population

Sleep quality is a complex construct, making it difficult to evaluate empirically. Over the years, many different sleep assessment methods have appeared. Most of the available studies have been performed using subjective methods such as sleep questionnaires and sleep diaries and only in few cases contact or contactless devices. Sleep questionnaires are very rapid and inexpensive tests that can be administered via internet and for these reasons they are ideal to assess sleep in large population samples. Moreover, questionnaires summarize in a quantitative way the subject’s perception about his own quality of sleep. As they are mostly subjective, sleep questionnaires can be influenced by the same sources of bias and inaccuracy as any other such reports [8]. About 50% of all studies published on sleep quality during this pandemic use the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), followed by the Athens Insomnia Index and the Insomnia Severity Index [9]. Other research-developed methods have been used, but the validity of these studies is unclear.

Prevalence of Sleep Disturbance

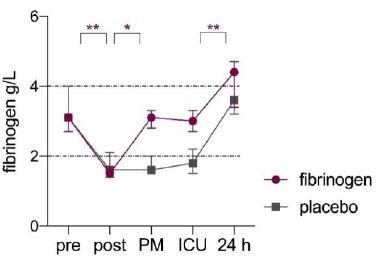

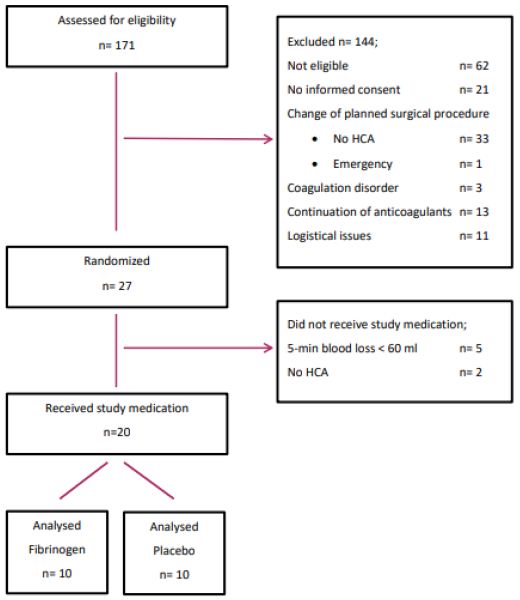

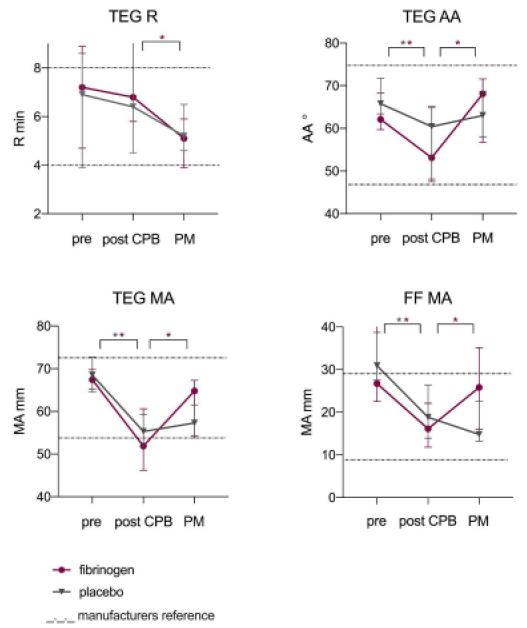

First data on the occurrence of sleep disturbance came from China, where the epidemic started in Wuhan in December 2019 and where the first psychological and emotional impact of the pandemic was assessed. Here, during the initial phase of the outbreak, more than half of people reported signs of distress and moderate to severe anxiety [10-13]. In one study, 2030 subjects who were Wuhan residents, had been to Wuhan or had contact with anyone from Wuhan during the outbreak, were interviewed in the two months following the WHO’s announcement [10]. Results revealed that in an early phase more than 50% of participants were not fully satisfied with their sleep quality and one third reported various sleep problems including longer sleep onset latency, short sleep duration and sleep fragmentation[10]. The worst sleep difficulties were reported by 4% of subjects complaining symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Huang and Zhao also collected early information from a survey on 7236 volunteers and found that 35% of these participants reported symptoms of general anxiety, 20% of depression, and 18% of poor sleep quality [14]. The high prevalence of COVID-19-related sleep disorders and its correlation with psychological stress has been confirmed worldwide outside China. In Italy a devastating outbreak spread soon after the onset in China with an impressive number of deaths in March 2020. Here, Casagrande and colleagues showed that, among 2291 subjects from the general population, 57.1% complained poor sleep quality, and evidenced a significant relationship between sleep quality, generalized anxiety and PTSD symptoms [15]. The population included in this study was very young (mean age 18 years), but similar data were reported by Innocent and co-workers in another sample of adults (mean age 50 years) [16]. These authors, analyzing details of the sleep disturbance, reported an increase in bad dreams from 1 out of 10, before the pandemic, to 4 out of 10 after [16]. They also reported that the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with a 6% increase in the number of people who took sleeping medications 3 or more times a week [16]. A recent Italian study also revealed an increased frequency of nightmares in a sample of 5988 adults during the pandemic. Predictors of higher nightmare frequency were young age, female gender, sleep duration, intra-sleep wakefulness, anxiety and depression [17]. Data collected from a large representative sample in UK households (14 393 participants) indicate that the percentage of adults reporting mental health problems increased from approximately 23% in 2017–2019 to approximately 37% in late April 2020. Again, problems included anxiety, depression and sleep disturbance [18]. In 2020, high rates, up to73%, of self-reported sleep disturbance were shown also in Germany, France and Greece [19-21]. After one year of wide investigation of COVID-19-related sleep disturbance, a few meta-analyses have summarized results providing worrying conclusion [9,22]. One meta-analysis analyzed a total of forty-four papers pooling together 54,231 subjects from 13 countries, reporting a prevalence of sleep problems of approximately 35% [9]. As expected, patients with active COVID-19 appeared to have a higher prevalence rate. Subgroup analysis by countries revealed that Italy had the highest pooled prevalence rate of 55% (95% CI 53-56%), followed by France 50.8% (95% CI 49-52.6%). These data are not surprising as Italy faced the shock to represent the gate way of the epidemic in the western world, when most of the scientific leaders worldwide believed that the outbreak would be confined to China. It is interesting that another meta-analysis, summarizing psychological conditions of the general population during the pandemic, found that rates of anxiety and depression were 33.7% and 31.9%, respectively [23]. The overlapping prevalence rates between psychological stress indicators and sleep problems point to a bidirectional relationship between sleep and psychiatric morbidities [9] (Figure 1). The latest meta-analysis analyzing both psychological stress and insomnia pooling 137 articles found a prevalence of depression, anxiety and insomnia of 15.9%, 15.1% and 23% respectively [22]. Interestingly, this meta-analysis, published after one year from the pandemic onset, showed a very high rate of PTSD (21.9%) as compared to what reported earlier China. These authors conclude that the psychological stress and insomnia related to COVID-19 are equally high across affected countries and across gender [22]. While I am writing, a large survey on several thousand adults from different countries around the world is ongoing. The survey, conducted by the International COVID-19 Sleep Study aims to describe the nature of various sleep and circadian rhythms symptoms, as well as their psychological and medical correlates, that arise at various points during the COVID-19 pandemic [24].

Effect of Home-confinement on Sleep Pattern

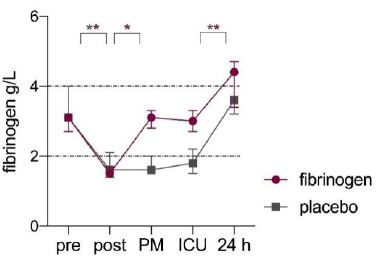

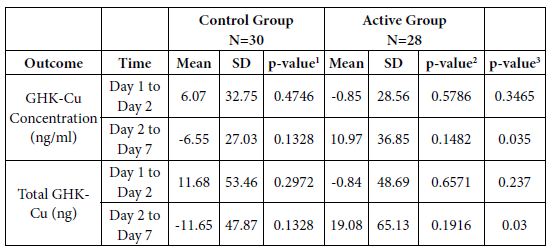

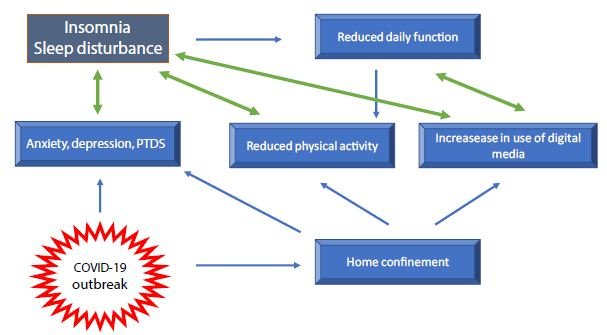

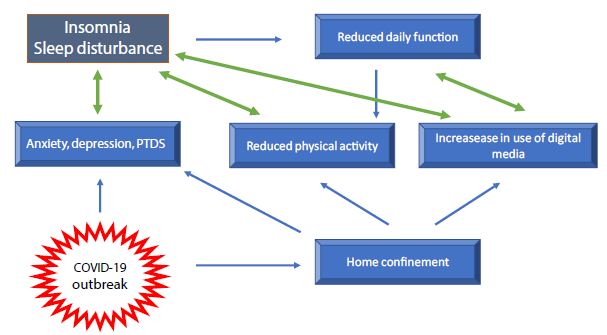

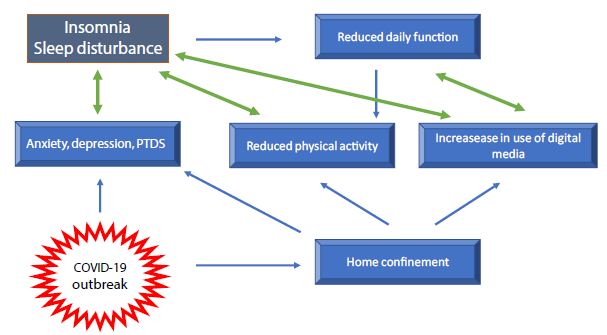

Being forced to stay at home and in many cases working from home, thus reducing social contacts, may have a great impact on daily functioning such as in night sleep and produces alteration of circadian rhythms. Italy was the first European country to impose a total unprecedented lockdown in March 2020. During that month, while people were forced into home confinement, an on-line survey was conducted in 1310Italian residents [25]. It was observed that during home confinement, sleep timing significantly changed, with people going to bed about one ore later and waking up later, spending more time in bed. However, paradoxically, the sleep quality was lower according to the PSQI results [25]. Sleep difficulties, other than correlating with the level of anxiety, were associated with the feeling of elongation of time. Other peculiar data relative to the lockdown were reported, such as people experiencing confusion about what day of the week, day of the month and time of the day it was. After this early study, other studies have confirmed changes in sleep habits during the lockdown period. Some of these confirmed a longer sleep time, particularly among students [26-29]. Lee and co-workers analyzed the sleep pattern of 25217 subjects between 1st January and 29th April 2020 in the US and in16 European countries. They found that the sleeping pattern before and after the country-level lockdown largely differed, but generally the population delayed and slept longer than usual [29]. It is important to note that a longer time spent in bed simply reflects more time spent at home and does not indicate a good quality of sleep, that in fact worsens [25,30]. The stress-sleep link during lockdown periods has been analyzed by a taskforce of the European CBT-I Academy [31]. This taskforce has highlighted that individuals’ sleep habits during lockdown periods are challenged by several factors other than physiological distress. These include alteration of the circadian rhythm due to a reduced exposure to sunlight and reduced physical activity which is known to improve sleep quality [31] (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Factors influencing sleep quality during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In working parents, sleep habit may change due to the need to combine work with home-schooling and home administration, that may affect the time spent to sleep. A different situation is that of people living alone, particularly those who have not chosen it. In these individuals home confinement may induce an exacerbation of loneliness and it has been previously established that the lack of social interaction, causing feeling of loneliness, may negatively affect sleep quality [32]. Conversely, it has been reported that during the pandemic those who scored higher on measures of social participation and sense of belonging reported a better quality of sleep [33]. Although common trends have been described, it is clear that effect of confinement measures on sleep quality is not uniform, depending on a variety of individual characteristics. For example, one study has been published showing, unexpectedly, that in one sample COVID-19 lockdown measures worsened sleep quality in pre-pandemic good sleepers, whereas a subset of people with pre-pandemic severe insomnia underwent a clinically meaningful alleviation of symptoms [34]. The concern about negative sleep-related effects of home confinement has prompt the European CBT-I Academy taskforce to provide specific recommendations for the general population, for women and children in family context, for healthcare staff and recommendations for the use of sleep medication [24].

Risk Factors for Sleep Disturbance

Some individuals are more likely to develop sleep problems than others. Those individuals sensitive to stress-related sleep disruption are more likely to develop chronic insomnia [31]. Examined risk factors for COVID-19-related sleep disturbance include age, sex, level of education, occupation and other individual factors [9,31]. It is likely however, that the common means by which sleep is affected is the level of anxiety generated by all pandemic-related concerns, including mainly family’s health, country’s economic stability, physical health and personal economic situation [35]. The effect of gender on sleep disturbance has been extensively investigated. Sleep in woman differs from that of man, mainly for hormonal factors changing during their life span, but also for social factors such as children caring [36,37]. Generally, women report more need to sleep and more insomnia. Sleep disruption is frequently reported by women particularly during pregnancy and the first years of life of children [31,36,37]. As confinement may change habits in the life of the children, this period can be particularly stressful for mothers or other caregivers [31]. Notwithstanding, pre-existing insomnia is a major risk for developing PTSD during the pandemic, particularly in women [31,37]. Many studies have reported that female sex is a major determinant of poor sleep quality [10,11,20]. However, when data were pooled, meta-analysis did not confirm the effect of gender on sleep quality [9,22]. Trakada and colleagues assessed sleep disturbance and risk factors during the lockdown periods in five European countries and in Brazil, in a sample of 1908 participants [38]. Overall the total sleep time was approximately 25 minutes longer than usual but 1in 3 individuals reported sleep disturbance. People with a higher educational level reported the best quality and longer duration of sleep. Differences in sleep duration were observed among different countries, with the worst quality recorded in Brazil a country experiencing a dramatic outbreak followed by striking political problems [39]. Differences among countries depend on different ways of living and sleeping habits, but also on the socioeconomic status of the country as this can increase the public fear and concern [38]. As for the role of the educational level, differently from this study, other reports showed that people with higher education levels experienced an increased mental stress at the time of the pandemic [18,40]. In a sample of adults in the United States a higher education level was associated with greater concerns about the consequences of COVID-19 (e.g., becoming seriously ill) [40]. Perhaps, a higher education determines greater engagement and interest in health information, but also an increased ability to use information to rationalize risks. The effect of age on sleep disturbance has also been explored. It is now acquired that young adults, without a pre-existing diagnosis, are at great risk to develop sleep disturbance when compared to the general population [9,20,21,25,41]. Other factors have been taken into account as determinants of poor sleep quality. Never, before this pandemic, media have played such a determinant role in providing information and recommending preventive behaviors. However, despite its undisputable usefulness, media, by repeating stressing information, can alter the emotional status, producing anxiety. The predictable overuse of media during lockdowns has been associated with poor sleep quality and day time impairment [25,42]. The over use of digital media before going to bed increases sleep latency, bedtime and wake time [25]. Furthermore, people suffering from insomnia tend to use internet overnight, consequently creating a vicious circle. The lockdowns during the pandemic also caused a reduction in physical activity. As it is known that physical activity improves sleep quality, the reduced activity and the poor quality of sleep are both related to decrease wellbeing during the pandemic [43,44]. Finally, many less obvious factors, belonging to the individual’s personal experiences and life, have been considered as stressors determining sleep disturbance. For example, one study showed that, among American Indians, childhood trauma predicts greater declines in sleep quality associated with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic [45].

Is Pandemic-related Sleep Disturbance a Transient Problem?

Indeed, the common sense suggests a form of adaptation to this pandemic, as to other negative events that may occur in life. In Germany, a web-based survey was conducted to assess the public mental health burden over a period of 50 days after the COVID-19 outbreak onset. A total of 16245 individuals provided information on sleep disturbances, COVID-19-fear, and level of anxiety [46]. The fear increased with the increasing infection rate but decreased within six weeks to the level before the shutdown, indicating habituation to the threatening situation. The level of anxiety and sleep disturbance proceeded simultaneously with high peaks of infection [46]. Interestingly, one group showed that in France the prevalence of sleep problems significantly decreased during the last weeks of the confinement, and this trend was confirmed one month after the end of the confinement, therefore suggesting that sleep disorders might be transient[47]. However, the possibility of recovering a good sleep pattern largely depends on the type and on the severity of the sleep disorder and is more common in people with mild problems [47]. One study analyzed the effect of sleep habits and social interactions on depression, insomnia and sleepiness, through the COVID-19 pandemic, in a group of patients visiting a specialized sleep clinic in Japan. The authors reported that self-isolation due to COVID-19 had relatively small one-year effects on depression, sleepiness and insomnia in a clinical population [48]. It is therefore likely that as the pandemic is going on, coping strategies have been activated to protect the mental status with favorable consequences on sleep quality.

Sleep Disturbance in Specific Subsets of the Population

Patients with SARS-CoV-2 Infection and COVID-19

Most of the studies on sleep disturbance have been performed in the general population and in health care workers, with fewer studies addressing the problem in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection/COVID 19. Hartley and co-workers performed an on-line survey in 1777 patients in quarantine for SARS-CoV-2 infection [49]. Forty-seven percent of participants reported a decrease in sleep quality during the quarantine. Factors associated with a reduction in sleep quality by logistic regression were sleep reduction (OR 15.52), going to bed later (OR 1.72), getting up earlier (2.18), an increase in sleep-wake irregularity (OR 2.29), reduced exposure to daylight (OR 1.46) and increased screen use in the evening (OR 1.33) [49]. Liguori and co-workers interviewed a total of 103 patients hospitalized for COVID-19 in order to assess the presence of neurological symptoms. They found that sleep impairment was the most frequent symptom, followed by dysgeusia, headache, hyposmia, and depression [50]. They also reported that women were more commonly affected by daytime somnolence. In addition, sleep impairment was more frequent in patients with more than 7 days of hospitalization [50]. Insomnia was also reported in 12% of patients with COVID-19 during the recovery period after discharge from the hospital [51]. As for other categories, data on patients with COVID-19 were obtained using questionnaires. However, another Italian group assessed sleep using wrist actigraphy in a limited number of patients who had experienced severe respiratory symptoms and who had needed prolonged intensive care unit (ICU). In these patients they reported a lower sleep efficiency and immobility time and a higher fragmentation index compared to those patients who had experienced only mild respiratory symptoms and not requiring ICU stay [52]. A meta-analysis showed that patients with COVID-19 have a higher prevalence of sleep disturbance, 74.8%, compared to the general population and HCW [9]. These data are not surprising as symptoms such as cough, dyspnea, fever and pain may disturb sleep. In addition, drugs used to treat COVID-19, such as oral steroids, may cause insomnia. Furthermore, patients with SARS-CoV2 infection, particularly if hospitalized, show a high prevalence of anxiety and depression that may contribute to impair sleep [53].

Older People

The COVID-19 pandemic has greatly affected the life of the elderly and the association of age with a higher vulnerability to COVID-19 is a subject of major importance [54]. Older adults may experience loneliness due to social distancing and isolation. Moreover, as age is the main factor influencing mortality for Coivid-19, the elderly may be greatly concerned by the risk to be infected, particularly if affected by chronic diseases [54]. With aging the maintenance of circadian rhythms is more difficult, as melatonin level diminishes, and older age is often associated with a reduction in sleep efficiency and continuity [54,55]. Notwithstanding, as most of data on sleep problems during the pandemic have been collected by web survey, studied samples more commonly include young adults, being these the biggest users of the internet, and only few studies included the elderly. Indeed in the general population age is associated with a higher prevalence of sleep disorders during the pandemic [9]. Sleep problems in the elderly correlate with the level of loneliness [56]. This loneliness-sleep disturbance association is especially strong among those people with more COVID-19 related worries or among those with lower resilience [56]. Goodman-Casanova and co-workers in a group of old adults with a diagnosis of moderate dementia, confirmed that those living alone reported greater negative psychological effects and sleeping problems during home confinement [57]. Indeed, further studies are necessary to understand the impact of the pandemic on mental status and sleep quality of the elderly, so that protective strategies can be implemented.

Healthcare Workers

This epidemic is greatly challenging HCW who are particularly vulnerable to the effect of COVID-19 on mental status as well as on physical health. As the emergency started the burden of work has dramatically increased for all healthcare categories and particularly for those directly involved in the management of patients with COVID-19. In addition to common general concerns, the strict contact with patients increases the HCW’s fear of the to be infected or to infect familiars. Moreover, when the pandemic started most of the HCW were unfamiliar with the use of personal protection equipment and were not used to deal with infectious patients, so that their working condition was extremely stressing [58]. As a consequence of accumulated psychological pressure and intense fear of dying, suicides have been also reported among HCW [59]. In this context, the occurrence of sleep disturbance among HCW has been a predictable consequence and has been widely explored since the beginning of the emergency [33,58,60,61]. Ferini-Strambi and co-workers highlight that sleep problems among HCW were common before the pandemic onset, with up to 61% of nurses complaining poor sleep quality [62]. Poor sleep quality reduces day time functioning and mental resources, impairs decision making and reduces concentration [63]. Therefore, in HCW a poor sleep night, particularly if recurrent over time, causes irreversible errors that can threaten patient’s life. Particularly during this pandemic, errors can also threaten the worker’s health, as the risk of infection while working increases. The first large study on medical staff reported insomnia, accompanied by anxiety and depression in more than 30% of frontline workers [64]. Since this and other early observations in China, a large amount of work has been produced and analyzed by a number of meta-analysis [9,65-68]. An early meta-analysis, published in May 2020, included 13 studies with a total of 33062 participants [65]. Anxiety, depression and insomnia were reported with a prevalence rate of 23.2%, 22.8% and 38.9% respectively. The prevalence rate of anxiety and depression appeared to be higher in females. Nurses, that are the larger healthcare workforce and are at close contact with the patients, were more affected than doctors. Conversely, Salari and co-workers reported a pooled prevalence rate of sleep disturbance of 37.8% in nurses and 41.6% in physicians [67]. A more recent meta-analysis including a total of 93 studies on nurses found even higher pooled rates of anxiety and sleep disturbance, 37% and 43%, respectively [65]. Although some small differences among studies, it is clear and expected that the occurrence of sleep disturbance, associated with a high level of physiological stress, among HCW is a worrying issue that may have important social implications. These reports outline the urgency of interventions to improve the psychological wellbeing of health workers.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic is one of the greatest challenges faced by the world from the beginning of this century, heavily affecting governments, general public and health systems. The pandemic, as well as causing physical problems and deaths, has heavily weakened the population’s mental health, particularly in developed countries where people, since long time, were not used to such kind of catastrophe. The widespread of depression, anxiety, sorrow and worry for the future has been associated invariably with sleep disruption and insomnia. The occurrence of a sleep disorder can further contribute to worsen people’s psychological status in a vicious cycle, that is difficult to break and which can contribute to generate fearsome and irreversible events, including suicide. Sleep disturbance is widespread in all countries parallel with the pandemic and a bidirectional relationship exists between sleep and psychological disorders. In light of these considerations, it is clear that measures must be taken in order to help people to restore their quality of sleep.

Disclosures

The author has no disclosures.

References

- WHO (2020) Mental health and psychosocial considerations during COVID-19 outbreak.

- Tempesta D, Socci V, De Gennaro L, Ferrara M (2018) Sleep and emotional processing. Sleep Med Rev 40:183-95. [crossref]

- Sakurai M, Chughtai H (2020) Resilience against crises: COVID-19 and lessons from natural disasters. Special edition: Orchestration in Contemporary Software Development Ecosystems 29.

- Léger D, Bayon V (2010) Societal costs of sleep disturbances. Sleep Med Rev 14:379-89. [crossref]

- Grandner MA (2020) Sleep, Health. Sleep Med Clin 15:319-340.

- Killgore WDS, Cloonan SA, Taylor EC, Fernandez F, Grandner MA, et al. (2020) Suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of insomnia. Psychiatry Res 290:113134. [crossref]

- Silva ESME, Ono BHVS, Souza JC (2020) Sleep and immunity in times of COVID-19. Rev Assoc Med Bras 66:143-147. [crossref]

- Ibáñez V, Silva J, Cauli O (2018) A survey on sleep assessment methods. PeerJ 6: e4849. [crossref]

- Jahrami H, BaHammam HS, Bragazzi NL, Saif Z, Faris MA, et al. (2021) Sleep problems during the COVID-19 pandemic by population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med 17: 299-313. [crossref]

- Zhang F, Shang Z, Ma H, Jia Y, Sun L, et al. (2020) Epidemic area contact history and sleep quality associated with posttraumatic stress symptoms in the first phase of COVID-19. Sci Rep 10: 22463.

- Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, et al. (2020) Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:1729-132. [crossref]

- Zhao X, Lan M, Li H, Yang J (2020) Perceived stress and sleep quality among the non-diseased general public in China during the 2019 coronavirus disease: a moderated mediation model. Sleep Med 77: 339-345

- Lin LY, Wang J, Ou-Yang XY, Miao Q, Chen R, et al. (2020) The immediate impact of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak on subjective sleep status. Sleep Med 77: 348-354 [crossref]

- Huang, Y and Zhao N (2020) Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 epidemic in China: A webbased cross-sectional survey. PsychiatryRes 288: 1129-54. [crossref]

- Casagrande M, Favieri F, Tambelli R, Forte G (2020) The enemy who sealed the world: Efects quarantine due to the COVID-19 on sleep quality, anxiety, and psychological distress in the Italian population. SleepMed 75: 12-20. [crossref]

- Innocenti P, Puzella A, Mogavero MP, Bruni O, Ferri R, et al. (2020) Letter to editor: COVID-19 pandemic and sleep disorders: a web survey in Italy. Neurol Sci 41:2021-2022. [crossref]

- Scarpelli S, Alfonsi V, Mangiaruga A, Musetti A, Quattropani MC, et al. (2021) Pandemic nightmares: Effects on dream activity of the COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. J Sleep Res Pg No: e13300.

- Daly M, Sutin AR, Robinson E (2020) Longitudinal changes in mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from the UK Household Longitudinal Study. Psychol Med 13: 1-10. [crossref]

- Jung S, Kneer J, Krueger T (2020) The German COVID-19 survey on mental health: primary results. MedRxiv.

- Beck F, Léger D, Fressard L, Peretti-Watel P, Verger P, et al. (2021) COVID-19 health crisis and lockdown associated with high level of sleep complaints and hypnotic uptake at the population level. J Sleep Res 30:e13119

- Kaparounaki CK, Patsali ME, Mousa DV, Papadopoulou EVK, Papadopoulou KKK, et al. (2020) University students’ mental health amidst the COVID-19 quarantine in Greece. Psychiatry Res290:113111. [crossref]

- Cénat JM, Blais-Rochette C, Kokou-Kpolou CK, Noorishad PG, Mukunzi JN, et al. (2020) Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 295:113599. [crossref]

- Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, Vaisi-Raygani A, Rasoulpoor S, et al. (2020) Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Health 16:57. [crossref]

- Partinen M, Bjorvatn B, Holzinger B, Chung F, Penzel T, et al. (2021) Sleep and circadian problems during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic: the International COVID‐19 Sleep Study (ICOSS). J Sleep Res 30:e13206.

- Cellini N, Canale N, Mioni G, Costa S (2020) ense of time and digital media use during COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. J Sleep Res Pg No: e13074. [crossref]

- Ong JL, Lau T, Massar SAA, Chong ZT, Ng BKL, et al. (2020) COVID-19 Related Mobility Reduction:heterogenouseffects on physical activity rhythms. Sleep 44:179. [crossref]

- Gao C, Scullin MK (2019) Sleep health early in the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in the United States: integrating longitudinal, cross-sectional, and retrospective recall data. Sleep Med 73: 1-10. [crossref]

- Wright KP Jr, Linton SK, Withrow D, Casiraghi L, Lanza SM, et al. (2020) Sleep in university students prior to and during COVID-19 Stay-at-Home orders. CurrBiol 30:R797-R798 [crossref]

- Lee PH, Marek J, Nálevka P (2021) Sleep pattern in the US and 16 European countries during the COVID-19 outbreak using crowdsourced smartphone data. Eur J Public Health 31: 23-27.

- Blume C, Schmidt MH, Cajochen C (2020) Effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on human sleep and rest-activity rhythms. CurrBiol 30: R795-R797. [crossref]

- Altena E, Baglioni C, Espie CA, Ellis J, Gavriloff D, et al. Dealing with sleep problems during home confinement due to the COVID‐19 outbreak: Practical recommendations from a task force of the European CBT‐I Academy. J Sleep Res 29:e13052. [crossref]

- McHugh JE and Lawlor BA(2013) Perceived stress mediates the relationship between emotional loneliness and sleep quality over time in older adults. Br J Health Psychol 18: 546-555. [crossref]

- Xiao H, Zhang Y, Kong D, Li S, Yang N, et al. (2020) The effects of social support on sleep quality of medical staff treating patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in January and February 2020 in China Med Sci Monit 26:e923549.

- Kocevska D, Blanken TF, Van Someren EJW, Rösler L (2020) Sleep quality during the COVID-19 pandemic: not one size fits all. Sleep Med 76:86-88. [crossref]

- Statista (2020) Main worries or concerns about the COVID-19 / coronavirus pandemic in the United States, United Kingdom and Germany.

- Riemann D, Baglioni C, Bassetti C, Bjorvatn B, Dolenc Groselj L, et al. (2017) European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. J Sleep Res 26: 675-700. [crossref]

- Mindell JA and Jacobson BJ (2000) Sleep disturbances during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 29: 590-597. [crossref]

- Trakada A, Nikolaidis PT, Andrade MDS, Puccinelli PJ, Economou NT, et al. (2020) Sleep During “Lockdown” in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17: 9094. [crossref]

- The Lancet (2020) COVID-19 in Brazil: “So what?” Lancet395:1461.

- Sutin AR, Robinson E, Daly M, Gerend MA, Stephan Y, et al. (2020) Body mass index, weight discrimination, and psychological, behavioral, and interpersonal responses to the coronavirus pandemic. Obesity 28: 1590-1594.

- Hyun S, Hahm HC, Wong GTF, Zhang E, Liu CH (2020) Psychological correlates of poor sleep quality among U.S. young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sleep Med 78:51-56. [crossref]

- Léger D, Beck F, Fressard L, Verger P, Peretti-Watel P, COCONEL Group (2020) Poor sleep associated with overuse of media during the COVID-19 lockdown. Sleep 43:125. [crossref]

- Chouchou F, Augustini M, Caderby T, Caron N, Turpin NA, et al. (2020) The importance of sleep and physical activity on well-being during COVID-19 lockdown: reunion island as a case study. Sleep Med 77: 297-301. [crossref]

- Alonso-Martinez AM, Ramirez-Velez R, Garcia-Alonso Y, Izquierdo M, García-Hermoso A (2021) Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, Sleep and Self-Regulation in Spanish Preschoolers during the COVID-19 Lockdown. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18:693. [crossref]

- John-Henderson NA (2020) Childhood trauma as a predictor of changes in sleep quality in American Indian adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sleep Health 6: 718-722 [crossref]

- Hetkamp M, Schweda A, Bäuerle A, Weismüller B, Kohler H, et al. (2020) Sleep disturbances, fear, and generalized anxiety during the COVID-19 shut down phase in Germany: relation to infection rates, deaths, and German stock index DAX. Sleep Med 75:350-353. [crossref]

- Beck F, Leger D, Cortaredona S, Verger P, Peretti-Watel P, COCONEL Group (2020) Would we recover better sleep at the end of COVID-19? A relative improvement observed at the population level with the end of the lockdown in France. Sleep Med 78:115-119. [crossref]

- Ubara A, Sumi Y, Ito K, Matsuda A, Matsuo M, et al. (2020) Self-Isolation Due to COVID-19 Is Linked to Small One-Year Changes in Depression, Sleepiness, and Insomnia: Results from a Clinic for Sleep Disorders in Shiga Prefecture, Japan. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:8971-76. [crossref]

- Hartley S, Colas des Francs C, Aussert F, Martinot C, Dagneaux S, et al. (2020) The effects of quarantine for SARS-CoV-2 on sleep: an online survey. Encephale 3:S53-S59.

- Liguori C, Pierantozzi M, Spanetta M, Sarmati L, Cesta N, et al. (2020) Subjective neurological symptoms frequently occur in patients with SARS-CoV2 infection. Brain BehavImmun 88:11-16. [crossref]

- Liu HQ, Yuan B, An YW, Chen KJ, Hu Q, et al. (2021) Clinical characteristics and follow-up analysis of 324 discharged COVID-19 patients in Shenzhen during the recovery period. Int J Med Sci 18: 347-355.

- Vitale JA, Perazzo P, Silingardi M, Biffi M, Banfi G, et al. (2020) Is disruption of sleep quality a consequence of severe COVID-19 infection? A case-series examination. ChronobiolInt 37:1110-1114.

- Liguori C, Pierantozzi M, Spanetta M, Sarmati L, Cesta N, et al. (2021) Depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients with SARS-CoV2 infection.J Affect Disord 278:339-340. [crossref]

- Cardinali DP, Brown GM, Reiter RJ, Pandi-Perumal SR(2020) Elderly as a High-risk Group during COVID-19 Pandemic: Effect of Circadian Misalignment, Sleep Dysregulation and Melatonin Administration. Sleep Vigil 26: 1-7.

- Welz PS, Benitah SA (2020) Molecular connections between circadian clocks and aging. J Mol Biol 432: 3661-3679.

- Grossman ES, Hoffman YSG, Yuval Palgi Y, Shrira A (2021) COVID-19 related loneliness and sleep problems in older adults: Worries and resilience as potential moderators. PersIndivid Dif 168:110371.

- Goodman-Casanova JM, Dura-Perez E, Guzman-Parra J, Cuesta-Vargas A, Mayoral-Cleries F (2020) Telehealth home support during COVID-19 confinement for community-dwelling older adults with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia: survey study. J Med Internet Res 22:e19434. [crossref]

- Sheng X, Liu F, Zhou J, Liao R (2020) Psychological status and sleep quality of nursing interns during the outbreak of COVID-19. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao 40:346-350. [crossref]

- Montemurro N (2020) The emotional impact of COVID-19: From medical staff to common people. Brain BehavImmun 87: 23-24. [crossref]

- Qi J, Xu J, Li BZ, Huang JS, Yang Y, et al. (2020) The evaluation of sleep disturbances for Chinese frontline medical workers under the outbreak of COVID-19. Sleep Med. 72:1-4. [crossref]

- Tu ZH, He JW, Zhou N (2020) Sleep quality and mood symptoms in conscripted frontline nurse in Wuhan, China during COVID-19 outbreak: a cross-sectional study. Medicine (Baltimore) 99:e20769. [crossref]

- Ferini-Strambi L, Zucconi M, Casoni F, Salsone M (2020) COVID-19 and Sleep in Medical Staff: Reflections, Clinical Evidences, and Perspectives. Curr Treat Options Neurol 22:29. [crossref]

- Medic G, Wille M, Hemels ME (2017) Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nat Sci Sleep 9:151-161.

- Zhang C, Yang L, Liu S, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. (2020) Survey of insomnia and related social psychological factors among medical staff involved in the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak. Front Psychiatry 11: 306.

- Pappa S ,Ntellac V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, et al. (2020) Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 88:901-907. [crossref]

- Al Maqbali M, Al Sinani M, Al-Lenjawi B (2021) Prevalence of stress, depression, anxiety and sleep disturbance among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res 141: 110343. [crossref]

- Salari N, Khazaie H, Hosseinian-Far A, Ghasemi H, Mohammadi M, et al. (2020) The prevalence of sleep disturbances among physicians and nurses facing the COVID-19 patients:a systematic review and meta-analysis.Global Health.16:92.

- Zeng LN, Yang Y, Wang C, Li XH, Xiang YF, et al. (2019) Prevalence of poor sleep quality in nursing staff: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Behav Sleep Med 18: 746-759. [crossref]