DOI: 10.31038/JPPR.2021411

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), viral illnesses maintain to emerge and constitute a critical trouble to public health. In the ultimate twenty years, numerous viral epidemics including the excessive acute respiration syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in 2002 to 2003, and H1N1 influenza in 2009, had been recorded. Most recently, the Middle East respiration syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) became first diagnosed in Saudi Arabia in 2012. In a timeline that reaches the existing day, an endemic of instances with unexplained low breathing infections detected in Wuhan, the biggest metropolitan place in China’s Hubei province, became first mentioned to the WHO Country Office in China, on December 31, 2019. Published literature can hint the start of symptomatic people lower back to the start of December 2019. As they have been not able to discover the causative agent, those first instances have been categorized as “pneumonia of unknown etiology.” The Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and nearby CDCs prepared an extensive outbreak research program. The etiology of this infection became attributed to a unique virus belonging to the coronavirus (CoV) family. On February 11, 2020, the WHO Director-General, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, introduced that the disorder resulting from this new CoV changed into a “COVID-19,” that is the acronym of “coronavirus disorder 2019”. In the beyond twenty years, extra CoVs epidemics have happened [1]. SARS-CoV provoked a large-scale epidemic starting in China and regarding dozen nations with about 8000 instances and 800 deaths, and the MERS-CoV that started out in Saudi Arabia and has about 2,500 instances and 800 deaths and nonetheless reasons as sporadic instances.

This new virus appears to be very contagious and has quick unfold globally. In a assembly on January 30, 2020, in step with the International Health Regulations (IHR, 2005), the outbreak changed into declared through the WHO a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) because it had unfold to 18 nations with 4 nations reporting human-to-human transmission. An extra landmark happened on February 26, 2020, because the first case of the disorder, now no longer imported from China, changed into recorded withinside the United States (US). Initially, the new virus was called 2019-nCoV. Subsequently, the task of experts of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) termed it the SARS-CoV-2 virus as it is very similar to the one that caused the SARS outbreak (SARS-CoVs). The CoVs have become the major pathogens of emerging respiratory disease outbreaks. They are a large family of single-stranded RNA viruses (+ssRNA) that can be isolated in different animal species. For reasons yet to be explained, these viruses can cross species barriers and can cause, in humans, illness ranging from the common cold to more severe diseases such as MERS and SARS. Interestingly, these latter viruses have probably originated from bats and then moving into other mammalian hosts — the Himalayan palm civet for SARS-CoV, and the dromedary camel for MERS-CoV — before jumping to humans. The dynamics of SARS-Cov-2 are currently unknown, but there is speculation that it also has an animal origin. The capability for those viruses to develop to emerge as an epidemic global appears to be a critical public fitness risk. Concerning COVID-19, the WHO raised the chance to the CoV epidemic to the “very high” level, on February 28, 2020. On March 11, because the quantity of COVID-19 instances outdoor China has expanded thirteen instances and the quantity of nations concerned has tripled with greater than 118,000 instances in 114 international locations and over 4,000 deaths, WHO declared the COVID-19 an epidemic. World governments are at paintings to set up countermeasures to stem feasible devastating effects. Health companies coordinate records flows and troubles directives and hints to exceptional mitigate the effect of the chance. At the equal time, scientists round the sector paintings tirelessly, and records approximately the transmission mechanisms, the scientific spectrum of disease, new diagnostics, and prevention and healing techniques are unexpectedly developing. Many uncertainties stay in regards to each the virus-host interplay and the evolution of the pandemic, with precise connection with the instances while it’s going to attain its peak.

At the moment, the healing techniques to address the contamination are handiest supportive, and prevention aimed toward decreasing transmission withinside the network is our first-rate weapon. Aggressive isolation measures in China have caused a modern discount of cases. In Italy, in geographic areas of the north, initially, and eventually in the course of the peninsula, political and fitness government are making high-quality efforts to include a surprise wave this is seriously trying out the fitness system. In the midst of the crisis, the authors have selected to apply the “Statpearls” platform because, in the PubMed scenario, it represents a completely unique device that can permit them to make updates in real-time. The aim, therefore, is to gather statistics and medical proof and to offer an outline of the subject so one can be constantly updated.

Etiology

CoVs are positive-stranded RNA viruses with a crown-like look beneathneath an electron microscope (coronam is the Latin time period for crown) because of the presence of spike glycoproteins at the envelope. The subfamily Orthocoronavirinae of the Coronaviridae own circle of relatives (order Nidovirales) classifies into 4 genera of CoVs: Alphacoronavirus (alphaCoV), Betacoronavirus (betaCoV), Deltacoronavirus (deltaCoV), and Gammacoronavirus (gammaCoV). Furthermore, the betaCoV genus divides into 5 sub-genera or lineages. Genomic characterization has proven that in all likelihood bats and rodents are the gene reassets of alphaCoVs and betaCoVs. On the contrary, avian species appear to symbolize the gene reassets of deltaCoVs and gammaCoVs. Members of this massive own circle of relatives of viruses can motive respiratory, enteric, hepatic, and neurological sicknesses in one-of-a-kind animal species, together with camels, cattle, cats, and bats. To date, seven humans CoVs (HCoVs) — able to infecting humans — had been diagnosed. Some of HCoVs had been diagnosed withinside the mid-1960s, whilst others had been most effective detected withinside the new millennium.

In general, estimates advise that 2% of the populace are wholesome vendors of a CoV and that those viruses are answerable for approximately 5% to 10% of acute respiration infections [2].

- Common human CoVs: HCoV-OC43, and HCoV-HKU1 (betaCoVs of the A lineage); HCoV-229E, and HCoV-NL63 (alphaCoVs). They can motive not unusual place colds and self-restricting higher respiration infections in immunocompetent individuals. In immunocompromised topics and the elderly, decrease respiration tract infections can occur.

- Other human CoVs: SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, and MERS-CoV (betaCoVs of the B and C lineage, respectively). These motive epidemics with variable medical severity offering respiration and extra-respiration manifestations. Concerning SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, the mortality prices are as much as 10% and 35%, respectively.

Thus, SARS-CoV-2 belongs to the betaCoVs category. It has spherical or elliptic and frequently pleomorphic form, and a diameter of about 60–one hundred forty nm. Like different CoVs, it’s far touchy to ultraviolet rays and heat [3]. In this regard, even though excessive temperature decreases the replication of any species of virus. Currently, the inactivation temperature of SARS-CoV-2 have to be properly elucidated. It appears that this virus may be inactivated at approximately 27°C. On the contrary, it is able to face up to the bloodless even beneath 0°C. Furthermore, those viruses may be successfully inactivated through lipid solvents together with ether (75%), ethanol, chlorine-containing disinfectant, peroxyacetic acid, and chloroform besides for chlorhexidine. In genetic terms, Chan [4] have demonstrated that the genome of the brand new HCoV, remoted from a cluster-affected person with abnormal pneumonia after traveling Wuhan, had 89% nucleotide identification with bat SARS-like-CoVZXC21 and 82% with that of human SARS-CoV. For this reason, the brand-new virus changed into known as SARS-CoV-2-. Its single-stranded RNA genome consists of 29891 nucleotides, encoding for 9860 amino acids. Probably, numerous SARS-CoV-2 exist. Although the SARS-CoV-2 origins aren’t totally understood, genomic analyses propose that SARS-CoV-2 in all likelihood advanced from a stress discovered in bats. The ability amplifying mammalian host, intermediate among bats and humans, is, however, now no longer known. Since the mutation withinside the authentic stress ought to have immediately brought on virulence closer to humans, it isn’t always sure that this middleman exists.

Transmission

Because the primary instances of the COVID-19 ailment had been related to direct publicity to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market of Wuhan, the animal-to-human transmission turned into presumed as the primary mechanism [5,6]. Nevertheless, next instances had been now no longer related to this publicity mechanism. Therefore, it turned into concluded that the virus may also be transmitted from human-to-human, and symptomatic human beings are the maximum common supply of COVID-19 unfold. Because of the opportunity of transmission earlier than symptoms, and for this reason folks that continue to be asymptomatic may want to transmit the virus, isolation is the great manner to comprise this epidemic. As with different breathing pathogens, inclusive of flu and rhinovirus, the transmission is assumed to arise via breathing droplets (particles >5-10 μm in diameter) from coughing and sneezing. Aerosol transmission is likewise viable in case of protracted publicity to accelerated aerosol concentrations in closed spaces [7]. Analysis of statistics associated with the unfold of SARS-CoV-2 in China appears to suggest that near touch among people is necessary. Of note, pre-and asymptomatic people may also make a contribution to up 80% of COVID-19 transmission. The unfold, in fact, Is mainly restricted to own circle of relatives members, healthcare professionals, and different near contacts (6 feet, 1.8 meters). Concerning the length of infection on gadgets and surfaces, a examine confirmed that SARS-CoV-2 may be determined on plastic for up to two-three days, chrome steel for up to two-three days, cardboard for up to at least one day, copper for as much as four hours. Moreover, evidently infection is better in extensive care units (ICUs) than widespread wards and SARS-Cov-2 may be determined on floors, pc mice, trash cans, and sickbed handrails in addition to in air as much as four meters from patients.

Based on facts from the primary instances in Wuhan and investigations performed through the China CDC and neighbourhood CDCs, the incubation time might be commonly inside three to 7 days (median 5.1 days, just like SARS) and up to two weeks because the longest time from contamination to signs became 12.5 days (95% CI, 9.2 to 18) [8]. This fact additionally confirmed that this novel epidemic doubled approximately each seven days, while the fundamental replica number (R0-R naught) is 2.2. In different words, on average, every affected person transmits the infection to an extra 2.2 individuals. Of note, estimations of the R0 of the SARS CoV epidemic in 2002-2003 had been about three. It has to be emphasised that these statistics is the end result of the primary reports. Thus, in addition research are had to recognize the mechanisms of transmission, the incubation instances and the scientific course, and the length of infectivity.

Epidemiology

Data furnished via way of means of the WHO Health Emergency Dashboard document 3,679,499 showed instances of COVID-19, inclusive of 254,199 deaths. Of note, 6.90 of instances had been deadly (as of 6:32 pm CEST, 7 May 2020). To date, there are instances in 215 Countries. Considering case comparison, in Europe there are 1,626,037 showed instances; Americas 1,542,829; Eastern Mediterranean 235,398; Western Pacific; South-East Asia 82,852; Africa 35,470. The maximum deadly instances had been recorded withinside the US (65,197) accompanied via way of means of UK (30,076), and Italy (29,684).

The maximum up to date supply for the epidemiology of this rising pandemic may be observed at the subsequent reasserts:

The WHO Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Situation Board. The Johns Hopkins Center for Systems Science and Engineering web website online for Coronavirus

Global Cases COVID-19, which makes use of brazenly public reassets to song the unfold of the epidemic.

Pathophysiology

CoVs are enveloped, positive-stranded RNA viruses with nucleocapsid. For addressing pathogenetic mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2, its viral shape, and genome need to be considerations. In CoVs, the genomic shape is prepared in a +ssRNA of about 30 kb in length — the biggest recognised RNA viruses — and with a 5′-cap shape and 3′-poly-Atail. Starting from the viral RNA, the synthesis of polyprotein 1a/1ab (pp1a/pp1ab) withinside the host is realized. The transcription works via the replication-transcription complex (RCT) prepared in double-membrane vesicles and through the synthesis of subgenomic RNAs (sgRNAs) sequences. Of note, transcription termination takes place at transcription regulatory sequences, positioned among the so-referred to as open analyzing frames (ORFs) that paintings as templates for the manufacturing of subgenomic mRNAs. In the abnormal CoV genome, as a minimum six ORFs may be present. Among these, a frameshift among ORF1a and ORF1b courses the manufacturing of each pp1a and pp1ab polypeptides which are processed with the aid of using virally encoded chymotrypsin-like protease (3CLpro) or primary protease (Mpro), in addition to one or papain-like proteases for generating sixteen non-structural proteins (nsps) [9]. Apart from ORF1a and ORF1b, different ORFs encode for structural proteins, inclusive of spike, membrane, envelope, and nucleocapsid proteins. And accent protein chains. Different CoVs gift unique structural and accent proteins translated with the aid of using committed sgRNAs.

Pathophysiology and virulence mechanisms of CoVs, and consequently additionally of SARS-CoV-2 have hyperlinks to the feature of the nsps and structural proteins. For instance, studies underlined that nsp is capable of block the host innate immune response. Among features of structural proteins, the envelope has a essential function in virus pathogenicity because it promotes viral meeting and release. However, a lot of those features (e.g., the ones of nsp 2, and 11) have now no longer but been described. Among the structural factors of CoVs, there are the spike glycoproteins composed of subunits (S1 and S2). Homotrimers of S proteins compose the spikes at the viral surface, guiding the hyperlink to host receptors [10]. Of note, in SARS-CoV-2, the S2 subunit — containing a fusion peptide, a transmembrane area, and cytoplasmic area — is extraordinarily conserved. Thus, it can be a goal for antiviral (anti-S2) compounds. On the contrary, the spike receptor-binding area provides handiest a 40% amino acid identification with different SARS-CoVs. Other structural factors on which studies ought to always cognizance is the ORF3b that has no homology with that of SARS-CoVs and a secreted protein (encoded through ORF8), that is structurally distinct from the ones of SARS-CoV. In global gene banks including GenBank, researchers have posted numerous Sars-CoV-2 gene sequences. This gene mapping is of essential significance permitting researchers to hint the phylogenetic tree of the virus and, above all, the popularity of traces that fluctuate consistent with the mutations. According to latest research, a spike mutation, which likely befell in past due November 2019, precipitated leaping to humans. In particular, Angeletti [11] as compared the Sars-Cov-2 gene series with that of Sars-CoV. They analyzed the transmembrane helical segments withinside the ORF1ab encoded 2 (nsp2) and nsp3 and located that function 723 affords a serine in place of a glycine residue, even as the placement 1010 is occupied through proline in place of isoleucine. The count of viral mutations is fundamental for explaining capacity disorder relapses. The studies might be had to decide the structural traits of SARS-COV-2 that underlie the pathogenetic mechanisms. Compared to SARS, for example, preliminary medical information display much less more breathing involvement, despite the fact that because of the dearth of large information, it isn’t feasible to attract definitive medical information.

The pathogenic mechanism that produces pneumonia appears to be specifically complex. Clinical and preclinical studies will need to give an explanation for many factors that underlie the unique medical displays of the disease. The information to date to be had appear to signify that the viral contamination is able to generating an immoderate immune response withinside the host. In a few cases, a response takes location which as an entire is categorised a ‘cytokine storm’. The impact is significant tissue harm with dysfunctional coagulation. Just some time ago, Italian researched added the time period of MicroCLOTS [12] (microvascular COVID-19 lung vessels obstructive thromboinflammatory syndrome) for underlying the lung viral harm related to the inflammatory response and the microvascular pulmonary thrombosis. While numerous cytokines which include the tumor necrosis thing α (TNF-α), IL-1β, IL-8, IL-12, interferon-gamma inducible protein (IP10), macrophage inflammatory protein 1A (MIP1A), and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP1) are implicated withinside the pathogenic cascade of the disease, the protagonist of this typhoon is interleukin 6 (IL-6). IL-6 is produced more often than not through activated leukocytes and acts on a big variety of cells and tissues. It is capable of sell the differentiation of B lymphocytes, promotes the boom of a few classes of cells, and inhibits the boom of others. It additionally stimulates the manufacturing of acute-section proteins and performs a vital position in thermoregulation, in bone preservation and withinside the capability of the principal worried system. Although the primary position performed through IL-6 is pro-inflammatory, it could additionally have anti-inflammatory effects [13]. In turn, IL-6increases in the course of inflammatory diseases, infections, autoimmune disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and a few forms of cancer. It is likewise implicated withinside the pathogenesis of the cytokine launch syndrome (CRS) this is an acute systemic inflammatory syndrome characterised through fever and a couple of organ dysfunction. IL-6 isn’t always the handiest protagonist at the scene. It turned into proved, for instance, that the binding of SARS-CoV-2 to the Toll-Like Receptor (TLR) induces the discharge of pro-IL-1β that is cleaved into the energetic mature IL-1β mediating lung inflammation, till fibrosis.

Histopathology

Tian [14] And others pronounced histopathological records received at the lungs of sufferers who underwent lung lobectomies for adenocarcinoma and retrospectively discovered to have had the contamination on the time of surgery. Apart from the tumors, the lungs of both ‘accidental’ instances confirmed edema and crucial proteinaceous exudates as massive protein globules. The authors additionally pronounced vascular congestion blended with inflammatory clusters of fibrinoid fabric and multinucleated massive cells and hyperplasia of pneumocytes. More recently, Zhang [15] executed a postmortem transthoracic needle lung biopsy in an affected person who died of COVID-19. Immunostaining confirmed diffuse alveolar harm and a vital alveolar expression of viral antigens. In autopsies on COVID-19 cases, the authors provided an in-depth image of the histological styles in lung and extrapulmonary tissues. This image turned into characterised through capillary congestion, necrosis of pneumocytes, hyaline membrane, interstitial edema, pneumocyte hyperplasia, and reactive atypia. Platelet-fibrin thrombi in small arterial vessels have been the expression of intravascular coagulopathy. Moreover, withinside the lung they located infiltrates expressed as macrophages in alveolar lumens and lymphocytes withinside the interstitium. In summary, much like SARS and MERS, excessive COVID-19 lung harm turned into manifested in phrases of Diffuse Alveolar Disease (DAD) with excessive capillary congestion. Again, numerous findings have been suggestive for vascular dysfunction [16], in lung and different tissues.

History and Physical

The medical spectrum of COVID-19 varies from asymptomatic or paucisymptomatic bureaucracy to medical situations characterised with the aid of using respiration failure that necessitates mechanical air flow and assist in an ICU, to multiorgan and systemic manifestations in phrases of sepsis, septic shock, and more than one organ disorder syndromes (MODS). In one of the first reviews at the disease, Huang [17] Illustrated that patients (n. 41) suffered from fever, malaise, dry cough, and dyspnea. Chest automated tomography (CT) scans confirmed pneumonia with extraordinary findings in all cases. About a 3rd of those (13, 32%) required ICU care, and there have been 6 (15%) deadly cases. The case research of Li [7] posted withinside the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) on January 29, 2020, encapsulates the primary 425 instances recorded in Wuhan. Data imply that the patients’ median age turned into fifty-nine years, with various 15 to 89 years. Thus, they pronounced no medical instances in kids under 15 years of age. There had been no large gender differences (56% male). On the contrary, in different reviews there’s a decrease incidence withinside the woman gender. Clinical and epidemiological facts from the Chinese CDC and concerning 72,314 case records (confirmed, suspected, diagnosed, and asymptomatic instances) had been shared withinside the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) [18], offering a primary crucial instance of the epidemiologic curve of the Chinese outbreak. There had been 62% showed instances, consisting of 1% of instances that had been asymptomatic, but were laboratory-positive (viral nucleic acid test). Furthermore, the general case-fatality rate (on showed instances) became 2.3%. Of note, the deadly instances had been basically aged sufferers, mainly the ones elderly ≥ eighty years (approximately 15%), and 70 to seventy-nine years (8.0%). Approximately half (49.0%) of the crucial sufferers and laid low with pre-existing comorbidities which include cardiovascular disease, diabetes, persistent breathing disease, and oncological diseases, died. While 1% of sufferers had been elderly nine years or younger, no deadly instances passed off on this group.

The authors of the Chinese CDC file divided the medical manifestations of the sickness through there severity:

- Mild sickness: non-pneumonia and moderate pneumonia; this passed off in 81% of cases.

- Severe sickness: dyspnea, breathing frequency ≥ 30/min, blood oxygen saturation (SpO2) ≤ 93%, PaO2/FiO2 ratio or P/F [the ratio between the blood pressure of the oxygen (partial pressure of oxygen, PaO2) and the percentage of oxygen supplied (fraction of inspired oxygen, FiO2)] < 300> 50% inside 24 to 48 hours; this passed off in 14% of cases.

- Critical sickness: breathing failure, septic shock, and/or a couple of organ dysfunction (MOD) or failure (MOF); this passed off in 5% of cases.

Data available from reviews and directives supplied via way of means of fitness coverage agencies, permit dividing the medical manifestations of the ailment in step with the severity of the medical pictures. The COVID-19 might also additionally gift with mild, moderate, or intense illness. Among the intense medical manifestations, there are intense pneumonia, ARDS, sepsis, and septic surprise. The medical direction of the ailment appears to are expecting a positive fashion withinside the majority of patients. In a percent nevertheless to be described of cases, after approximately per week there’s a surprising worsening of medical situations with hastily worsening respiration failure and MOD/MOF. As a reference, the standards of the severity of respiration insufficiency and the diagnostic standards of sepsis and septic surprise may be used.

Uncomplicated (Slight Illness)

These sufferers commonly gift with signs and symptoms of a higher respiration tract viral infection, together with slight fever, cough (dry), sore throat, nasal congestion, malaise, headache, muscle pain, or malaise. New lack of flavor and/or smell, diarrhea, and vomiting are commonly observed. Signs and signs and symptoms of a extra severe disease, which include dyspnea, aren’t gift.

Moderate Pneumonia

Respiratory signs and symptoms which include cough and shortness of breath (or tachypnea in children) are gift with out symptoms and symptoms of extreme pneumonia.

Severe Pneumonia

Fever is related to extreme dyspnea, breathing distress, tachypnea (> 30 breaths/min), and hypoxia (SpO2 < 90% on room air). However, the fever symptom should be interpreted cautiously as even in extreme types of the disease, it could be mild or maybe absent. Cyanosis can arise in children. In this definition, the prognosis is clinical, and radiologic imaging is used for aside from complications.

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS)

The prognosis calls for scientific and ventilatory criteria. This syndrome is suggestive of a severe new-onset breathing failure or for worsening of an already diagnosed breathing picture. Different types of ARDS are outstanding primarily based totally at the diploma of hypoxia. The reference parameter is the PaO2/FiO2, or P/F ratio:

- Mild ARDS: two hundred mmHg < PaO2/FiO2 ≤ three hundred In not-ventilated sufferers or in the ones controlled via non-invasive ventilation (NIV) via way of means of the use of tremendous end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) or a non-stop tremendous airway pressure (CPAP) ≥ five cm H2O.

- Moderate ARDS: one hundred mmHg < PaO2/FiO2 ≤ two hundred

- Severe ARDS: PaO2/FiO2 ≤ one hundred

When PaO2 isn’t Always Available, a Ratio SpO2/FiO2 ≤ 315 is Suggestive of ARDS

Chest imaging applied consists of chest radiograph, CT scan, or lung ultrasound demonstrating bilateral opacities (lung infiltrates > 50%), now no longer absolutely defined through effusions, lobar, or lung collapse. Although in a few cases, the scientific state of affairs and ventilator facts may be suggestive for pulmonary edema, the number one respiration starting place of the edema is confirmed after the exclusion of cardiac failure or different reasons consisting of fluid overload. Echocardiography may be useful for this purpose [19].

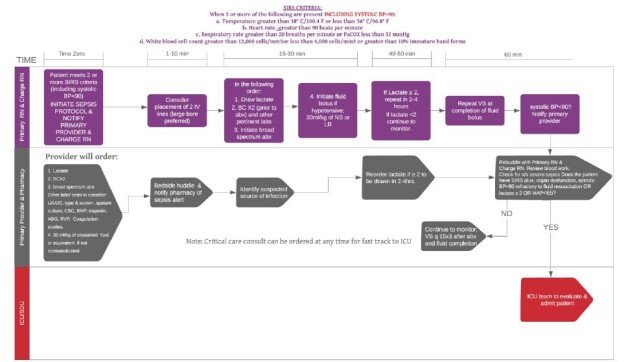

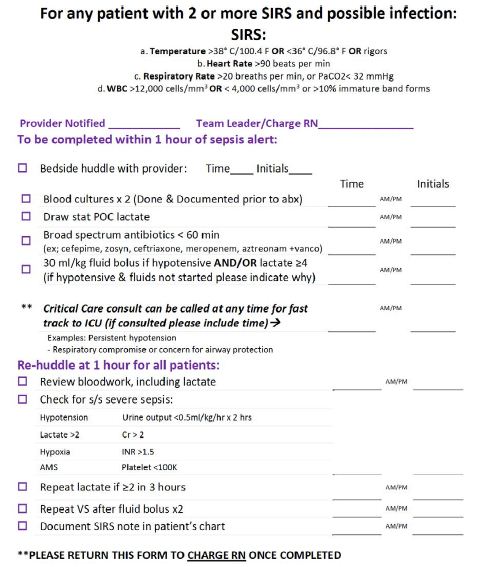

Sepsis

According to the International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3), sepsis represents a life-threatening organ disorder as a result of a dysregulated host reaction to suspected or demonstrated infection, with organ disorder. The scientific pics of sufferers with COVID-19 and with sepsis are specially serious, characterised through a huge variety of symptoms and symptoms and signs of multiorgan involvement. These symptoms and symptoms and signs encompass respiration manifestations inclusive of excessive dyspnea and hypoxemia, renal impairment with decreased urine output, tachycardia, altered intellectual status, and practical changes of organs expressed as laboratory statistics of hyperbilirubinemia, acidosis, excessive lactate, coagulopathy, and thrombocytopenia. The reference for the assessment of multiorgan harm and the associated prognostic importance is the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) rating, which predicts ICU mortality primarily based totally on lab outcomes and scientific statistics. A pediatric model of the rating has additionally acquired validation [20].

Septic Shock

In this scenario, that is related to elevated mortality, circulatory, and cellular/metabolic abnormalities including serum lactate stage more than 2 mmol/L (18 mg/dL) are present. Because sufferers commonly be afflicted by persisting hypotension in spite of quantity resuscitation, the management of vasopressors is needed to keep a median arterial pressure (MAP) ≥ 65 mmHg [20].

The Peculiar History of This New Disease

In a few sufferers, the medical records of this ailment happen with specific characteristics. It foresees that the affected person manifests specially fever, which isn’t always very conscious of antipyretics, and a nation of malaise. A dry cough is regularly associated. After 5-7 days, older sufferers with already impaired lung characteristic start to revel in shortness of breath and improved breathing rate. In extra fragile sufferers, however, dyspnea can also additionally already seem on the onset of symptoms. On the alternative hand, in more youthful topics and in people who do now no longer have primary breathing impairments or different comorbidities, dyspnea can also additionally seem later. In those sufferers experiencing worsening inflammatory-triggered lung injury, there may be a lower in oxygen saturation.

The situation is clearly notable because, for sufferers who’re paucisymptomatic and barely hypoxic, the primary healing technique is oxygen remedy. Although this approach is effective, the worsening of respiration failure can also additionally arise in a few sufferers. With the power preserved, the following step, consistent with logic, is the NIV. This remedy has a fast achievement with the aid of using growing the P/F. In a few sufferers, however, there’s a sudden, sudden worsening of scientific conditions. Patients fall apart below the operator’s eyes and require fast intubation and invasive mechanical air flow. However, after 24-48 hours the affected person may have a fast development with a boom in P/F. Operators are consequently tempted to continue with weaning. But very often, after a preliminary achievement, there’s a brand new worsening of respiration conditions, consisting of two require a brand new invasive remedy. Therefore, mechanical air flow has additionally been counselled for 1-2 weeks.

Evaluation

Most nations are making use of a few kind of scientific and epidemiologic facts to decide who ought to have trying out performed. In the US, standards were evolved for humans beneath investigation (PUI) for COVID-19. According to the U.S. CDC, maximum sufferers with showed COVID-19 have evolved fever and/or signs and symptoms of acute respiration illness (e.g., cough, trouble breathing). If someone is a PUI, it’s far advocated that practitioners at once installed area contamination manage and prevention measures. Initially, they advocate trying out for all different reassets of respiration contamination. Additionally, they advocate the usage of epidemiologic elements to help in choice making. There are epidemiologic elements that help withinside the choice on who to test. This consists of absolutely everyone who has had near touch with a affected person with laboratory-showed COVID-19 inside 14 days of symptom onset or a records of journey from affected geographic areas (currently China, Italy, Iran, Japan, and South Korea) inside 14 days of symptom onset [21,22].

Diagnosis

Molecular Test

The WHO recommends gathering specimens from each the top breathing tract (naso-and oropharyngeal samples) and decrease breathing tract along with expectorated sputum, endotracheal aspirate, or bronchoalveolar lavage. The series of BAL samples need to most effective be achieved in automatically ventilated sufferers as decrease breathing tract samples appear to stay superb for a extra prolonged period. The samples require garage at 4 tiers celsius. In the laboratory, amplification of the genetic fabric extracted from the saliva or mucus pattern is thru a opposite polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), which entails the synthesis of a double-stranded DNA molecule from an RNA mold. Once the genetic cloth is sufficient, the quest is for the ones quantities of the genetic code of the CoV which can be conserved. The probes used are primarily based totally at the preliminary gene series launched through the Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center & School of Public Health, Fudan University, Shanghai, China on Virological.Org, and next confirmatory assessment through extra labs. If the take a look at end result is positive, it’s miles encouraged that the take a look at is repeated for verification. In sufferers with showed COVID-19 diagnosis, the laboratory assessment ought to be repeated to assess for viral clearance previous to being launched from observation. The availability of checking out will range primarily based totally on which united states someone lives in with growing availability happening almost daily.

Serology

Despite the several antibody exams designed, so far serologic analysis has obstacles in each specificity and sensitivity. Again, outcomes from extraordinary exams vary. A CDC studies on a take a look at advanced through the United States Vaccine Research Center on the National Institutes of Health is ongoing. Of note, this takes a look at appears to have a specificity better than 99% with a sensitivity of 96%. Nevertheless, similarly studies are wanted for elucidating numerous elements of the matter. In particular:

- If IgG antibodies will offer immunity from destiny SARS-CoV-2 infection.

- On the protecting titer of antibodies.

- On the period of the protection.

Serologic, however, will have a crucial position in broad-primarily based totally surveillance.

Laboratory Examinations Concerning Laboratory Examinations

- In the early degree of the disease, an everyday or reduced general white blood mobileular rely (WBC) and a reduced lymphocyte rely may be Interestingly, lymphopenia seems to be a poor prognostic factor.

- Increased values of liver enzymes, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), muscle enzymes, and C-reactive protein may be

- Unless a bacterial overlap, an everyday procalcitonin cost is found.

- The improved neutrophil-to-lymphocyteratio (NLR), derived NLR ratio (d-NLR) [neutrophil count divided by the result of WBC count minus neutrophil count], and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, may be the expression of the inflammatory storm. The correction of those indices is an expression of a positive

- Increased D-dimer

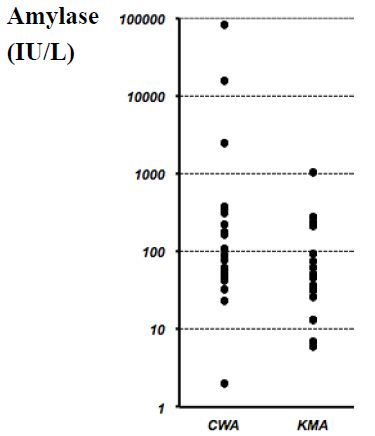

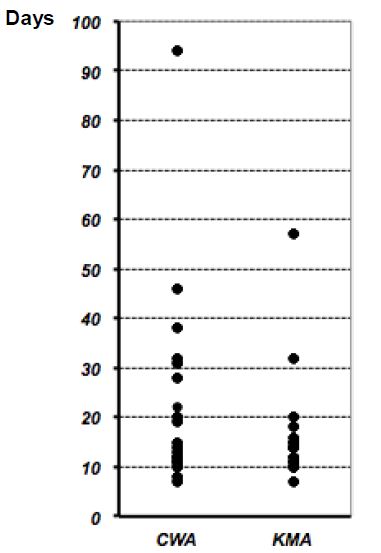

- In essential patients, D-dimer valueis increased, blood lymphocytes decreased persistently, and laboratory changes of multiorgan imbalance (excessive amylase, coagulation disorders, etc.) are found [23].

Imaging

Chest X-ray Exam

Since the ailment manifests itself as pneumonia, radiological imaging has a essential function withinside the diagnostic process, management, and follow-up. Standard radiographic exam (X-ray) of the chest has a low sensitivity in figuring out early lung modifications and withinside the preliminary ranges of the ailment. At this stage, it may be absolutely negative. In the greater superior ranges of infection, the chest X-ray exam usually suggests bilateral multifocal alveolar opacities, which generally tend to confluence as much as the entire opacity of the lung. Pleural effusion may be associated.

Chest Computed Tomography

Given the excessive sensitivity of the technique, chest computed tomography (CT), especially excessive-decision CT (HRCT), is the technique of preference withinside the have a look at of COVID-19 pneumonia, even withinside the preliminary stages. Several non-particular HRCT findings and styles may be found. Most of those findings can also be discovered in different lung infections, including Influenza A (H1N1), CMV, SARS, MERS, streptococcus, and Chlamydia, Mycoplasma. The maximum not unusual place findings are multifocal bilateral “floor or floor glass” (GG) regions related to consolidation regions with patchy distribution, especially peripheral/subpleural and with extra involvement of the posterior areas and decrease lobes. The “loopy paving” sample may be additionally observed. This latter locating is characterised with the aid of using the presence of GG regions with superimposed interlobular septal thickening and intralobular septal thickening. It is a non-particular locating that may be detected in one-of-a-kind conditions. Other findings are the “reversed halo sign” that is a focal place of GG delimited with the aid of using a peripheral ring with consolidation, and the locating of cavitations, calcifications, lymphadenopathies, and pleural effusion.

Lung Ultrasound

Ultrasound method can permit comparing the evolution of the disease, from a focal interstitial sample up to “white lung” with proof frequently of subpleural consolidations.

It ought to be finished in the first 24 hours withinside the suspect and each 24/48 hours and may be beneficial for affected person follow-up, desire of the putting of mechanical ventilation, and for indication of inclined positioning. The most important sonographic functions are:

- Pleural traces frequently thickened, irregular, and discontinuous till it nearly seems discontinuous; subpleural lesions may be visible as small patchy consolidations or nodules.

- B traces. They are frequently motionless, coalescent, and cascade and may waft as much as the rectangular of “White lung”.

- They are maximum glaring withinside the posterior and bilateral fields specially withinside the decrease fields; the dynamic air bronchogram in the consolidation is a manifestation of sickness evolution.

- Perilesional pleural effusion.

- In summary, throughout the direction of the disease, it’s miles feasible to become aware of the primary section with focal regions of constant B traces, a section of numerical boom of the traces B as much as the white lung with small subpleural thickenings, and in addition development till proof of posterior consolidations.

Treatment/Management

There isn’t any particular antiviral remedy encouraged for COVID-19, and no vaccine is presently available. The remedy is symptomatic, and oxygen remedy represents step one for addressing breathing impairment. Non-invasive (NIV) and invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) can be important in instances of breathing failure refractory to oxygen remedy. Again, extensive care is wanted to address complex styles of the disease. Concerning ARDS remedy, amassing understanding at the pathophysiology of lung damage, have progressively triggered clinicians to check techniques for managing breathing failure.

As Gattinoni [24] Suggested, COVID-19-caused ARDS (CARDS) isn’t always a “Typical” ARDS. This element of the sickness is of essential significance and has probable negatively affected the healing technique withinside the early tiers of the pandemic. Indeed, notwithstanding at starting of the pandemic, early IMV became postulated because the higher approach for addressing CARDS, in COVID-19 pneumonia the standard ARDS respiration mechanics offering decreased lung compliance (i.e., cappotential to stretch and enlarge lungs) can’t be found. On the contrary, in CARDS, excellent pulmonary compliance may be demonstrated. As a consequence, and in assessment to what became to start with believed, NIV will have a key function in CARDS therapy.

O2 Fast Challenge

In an affected person with a SpO2 < 93> 28-30/min, or dyspnoea, the management of oxygen through a 40% Venturi masks have to be performed. After a five to ten mins reassessment, if the scientific and instrumental photo has stepped forward the affected person keeps the remedy and undergoes a re-assessment inside 6 hours. In case of failure improvement, or new worsening, the affected person undergoes a non-invasive remedy, if now no longer contraindicated.

HFNO and Non-invasive Ventilation

In regards to HFNO or NIV, the experts’ panel, factors out that those tactics done via way of means of structures with appropriate interface becoming do now no longer create great dispersion of exhaled air, and their use may be taken into consideration at low danger of airborne transmission.

HFNO

Because this technique has a more danger of aerosolization, it need to be utilized in terrible strain rooms.

Suggested Approaches to Control HFNO

- Indication: while it’s far hard to hold SpO2 > 92% and/or now no longer stepped forward dyspnoea thru general

- Setting: 30-forty L/min and FiO2 50-60%; alter consistent with medical

- Switch to NIV if the symptomatology isn’t stepped forward after 1 hour with flow > 50 L/min and FiO2>70%.

- HFNO also can be used for CPAP breaks (among CPAP cycles) and for assisted fibreoptic tracheal intubation in seriously sick

- Contraindication to HFNO: hypercapnic patient.

- Non-invasive air flow and Continuous Positive Airway Pressure NIV/CPAP has a key position in coping with COVID-19-related breathing

- Suggested methods for acting NIV/CPAP:

- Interface: Helmet is desired for minimizing the chance of aerosolization. In the case of NIV with face mask (full-face or oronasal), the usage of expiratory valve included and non-tubes with exhalation port, and insert an antimicrobial clear out out at the expiratory valve is recommended.

Setting

- Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP): begin with 8-10 cmH2O and FiO2 60%

- NIV (e.g., Pressure guide ventilation, PSV): begin with PEEP five cmH2O checking the tolerance of the affected person and produce to 8-10 cmH2O, FiO2 60%, PS 8-10 cmH2O • Management: do now no longer make many adjustments withinside the first 24 hours; after as a minimum 4-6 hours, if stabilized, detach for optimum 1 hour and permit the consumption of small portions of fluids; during the night, NIV continuously.

Intubation and Protecting Mechanical Air Flow

Special precautions are vital all through intubation. The method needs to be performed through a professional operator who makes use of non-public protecting equipment (PPE) together with FFP3 or N95 masks, protecting goggles, disposable robe lengthy sleeve raincoat, disposable double socks, and gloves. If possible, fast series intubation (RSI) need to be performed. Preoxygenation (100% O2 for five minutes) need to be performedviathe non-stop wonderful airway pressure (CPAP) method. Heat and moisture exchanger (HME) need to be located among the masks and the circuit of the fan or among the masks and the air flow balloon [25].

Mechanical air flow has to be with decrease tidal volumes (four to six ml/kg expected frame weight, PBW) and decrease inspiratory pressures, accomplishing a plateau pressure (Pplat) < 28 to 30 cm H2O. PEEP ought to be as excessive as feasible to hold the using pressure (Pplat-PEEP) as little as feasible (< 14 cm H2O). Moreover, disconnections from the ventilator should be averted for stopping lack of PEEP and atelectasis. Finally, the usage of paralytics isn’t always advocated except PaO2/FiO2 < 150> 12 hours in line with day, and the usage of a conservative fluid control method for ARDS sufferers without tissue hypoperfusion (robust recommendation) are emphasized [26].

Other Therapies

Among different healing strategies, despite the fact that systemic corticosteroids for the remedy of viral pneumonia or acute breathing misery syndrome (ARDS) have been now no longer recommended, in extreme CARDS those capsules are generally used (e.g., methylprednisolone 1 mg/Kg die). Unselective or beside the point management of antibiotics ought to be avoided, despite the fact that a few facilities advocate it. Although no antiviral remedies were approved, numerous procedures were proposed inclusive of lopinavir/ritonavir (400/a hundred mg orally each 12 hours). Nevertheless, a latest randomized, controlled, open-label trial tested no advantage with lopinavir/ritonavir remedy in comparison to conventional care [27]. Preclinical research recommended that remdesivir (GS5734) — an inhibitor of RNA polymerase with in vitro pastime towards more than one RNA viruses, together with Ebola — may be powerful for each prophylaxis and remedy of HCoVs infections [28]. This drug changed into undoubtedly examined in a rhesus macaque version of MERS-CoV infection [29]. Alpha-interferon (e.g., five million gadgets through aerosol inhalation two times according to day) changed into additionally used. Chloroquine (500 mg each 12 hours), and hydroxychloroquine (two hundred mg each 12 hours) have been proposed as immunomodulatory therapy. Of note, in a non-randomized trial, Gautret [30] confirmed that hydroxychloroquine turned into appreciably related to viral load discount till viral disappearance and this impact turned into greater with the aid of using the macrolides azithromycin. In vitro and in vivo studies, indeed, have proven that macrolides may also mitigate infection and modulate the immune system [31]. In particular, those tablets may also result in the downregulation of the adhesion molecules of the molecular surface, decreasing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, stimulating phagocytosis with the aid of using alveolar macrophages, and inhibiting the activation and mobilization of neutrophils. However, similarly research is wanted for recommending using azithromycin, by myself or related to different tablets inclusive of hydroxychloroquine, outdoor of any bacterial overlaps [32]. Again, interest should be paid with the concomitant use of hydroxychloroquine with azithromycin because the affiliation can cause a better danger of QT c program language period prolongation and cardiac arrhythmias. Chloroquine also can set off QT prolongation. Because COVID-19 sufferers have a better prevalence of venous thromboembolism and anticoagulant remedy is related to decreased ICU mortality, it’s miles recommended that sufferers ought to obtain thrombo-prophylaxis [33]. Moreover, within side the case ofknown thrombophilia or thrombosis, complete therapeutic-depth anticoagulation (e.g., enoxaparin 1 mg/kg two times daily) is indicated.

In Italy, a wonderful research led via way of means of the Istituto Nazionale Tumori, Fondazione Pascale di Napoli is targeted on using tocilizumab similarly to conventional therapies. It is a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody, directed towards theIL-6 receptorand usually used withinside the remedy of rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile arthritis, massive mobileular arthritis, Castleman’s syndrome, and for handling toxicity because of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Moreover, withinside the US, a Phase 2/3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-managed have a look at on sarilumab this is some other anti-IL-6R antibody, is ongoing [34,35]. When the disorder outcomes in complicated medical images of MOD, organ characteristic assist further to respiration assist, is mandatory. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) for sufferers with refractory hypoxemia regardless of lung-protecting air flow ought to advantage attention after a case-by-case analysis. It may be recommended for people with bad outcomes to susceptible role air flow.

Prevention

Preventive measures are the cutting-edge method to restrict the unfold of cases. Because an endemic will growth so long as R0 is more than 1 (COVID-19 is 2.2), manage measures need to cognizance on lowering the price to much less than 1.

Preventive techniques are centered at the isolation of sufferers and cautious contamination manage, which includes suitable measures to be followed all through the prognosis and the supply of scientific care to an inflamed patient [35]. For instance, droplet, contact, and airborne precautions need to be followed all through specimen collection, and sputum induction need to be avoided.

- The WHO and different businesses have issued the subsequent well-known recommendations:

- Avoid near touch with topics stricken by acute breathing

- Wash your fingers frequently, specifically after touch with infected people or their environment.

- Avoid unprotected touch with farm or wild animals.

- People with signs of acute airway contamination ought to hold their distance, cowl coughs or sneezes with disposable tissues or garments and wash their fingers.

- Strengthen, in particular, in emergency medicinal drug departments, the utility of strict hygiene measures for the prevention and manipulate of infections.

- Individuals which might be immunocompromised ought to keep away from public gatherings.

The maximum crucial method for the populous to adopt is to often wash their fingers and use transportable hand sanitizer and keep away from touch with their face and mouth after interacting with a probable infected environment. Healthcare employees being concerned for inflamed people need to make use of touch and airborne precautions to encompass PPE inclusive of N95 or FFP3 masks, eye protection, gowns, and gloves to save you transmission of the pathogen. Meanwhile, clinical studies are developing to expand a coronavirus vaccine. In current days, China has introduced the primary animal tests, and researchers from the University of Queensland in Australia have additionally introduced that, after finishing the three-week in vitro study, they’re shifting directly to animal testing. Furthermore, withinside the U.S., the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) has introduced that a segment 1 trial has begun for a singular coronavirus immunization in Washington state.

Differential Diagnosis

The signs of the early ranges of the sickness are nonspecific. Differential prognosis ought to consist of the opportunity of an extensive variety of infectious and non-infectious (e.g., vasculitis, dermatomyositis) not unusual place breathing disorders.

- Adenovirus

- Influenza

- Human metapneumovirus (HmPV)

- Parainfluenza

- Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)

- Rhinovirus (not unusual place cold)

For suspected cases, speedy antigen detection, and different investigations have to be followed for comparing not unusual place respiration pathogens and non-infectious conditions. The Mayo Clinic proposed a COVID-19 self-evaluation device designed for setting up a ability candidate for a COVID-19 diagnostic test (https://www.Mayoclinic.Org/covid-19-self-evaluation-device).

Prognosis

Preliminary records indicate the suggested demise charge tiers from 1% to 2% pending at the take a look at and country. The majority of the fatalities have come about in sufferers over 50 years of age. Young youngsters look like mildly inflamed however might also additionally function a vector for extra transmission.

Complications

Long time period headaches amongst survivors of contamination with SARS-CoV-2 having clinically massive COVID-19 disorder aren’t but available. The mortality prices for instances globally stay among 1% to 2%. Follow-up research will make clear the quantity of the sequelae on organ functions, which include respiratory, renal, cardiovascular, in addition to psychological/psychiatric, and associated with persistent ache problems.

Deterrence and Patient Education

b

Patients and households have to acquire coaching to:

- Maintaining correct social distance is obligatory for stopping the unfold of the disease.

- Strict private hygiene measures (fingers wash) are essential for the prevention and manage of this contamination.

- Avoid near touch with topics stricken by acute breathing

- People with signs and symptoms of acute airway contamination have to preserve their distance, cowl coughs or sneezes with disposable tissues or clothes, and wash their fingers.

Immunocompromised sufferers have to keep away from public publicity and public gatherings. If an immunocompromised man or woman ought to be in a closed area with more than one people present, along with a assembly in a small room; masks, gloves and private hygiene with antiseptic cleaning soap need to be undertaken with the aid of using the ones in near touch with the individual. In addition, earlier room cleansing with antiseptic dealers need to be undertaken and executed earlier than publicity. However, thinking about the risk worried to those individuals, publicity need to be averted except a meeting, institution event, etc. Is a real emergency.

References

- Perlman S, Netland J (2009) Coronaviruses post-SARS: update on replication and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 7: 439-450. [crossref]

- Chan JF, To KK, Tse H, Jin DY, Yuen KY (2013) Interspecies transmission and emergence of novel viruses: lessons from bats and birds. Trends Microbiol 21: 544-555. [crossref]

- Chen Y, Liu Q, Guo D (2020) Emerging coronaviruses: Genome structure, replication, and pathogenesis. J Med Virol 92: 418-423. [crossref]

- Chan JF, Kok KH, Zhu Z, Chu H, To KK, et al. (2020) Genomic characterization of the 2019 novel human-pathogenic coronavirus isolated from a patient with atypical pneumonia after visiting Wuhan. Emerg Microbes Infect 9: 221-236. [crossref]

- Guo ZD, Wang ZY, Zhang SF, Li X, Li L, et al. (2020) Aerosol and Surface Distribution of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 in Hospital Wards, Wuhan, China, 2020. Emerging Infect Dis 126: 1583-1591. [crossref]

- Lauer SA, Grantz KH, Bi Q, Jones FK, Zheng Q, et al. (2020) The Incubation Period of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) From Publicly Reported Confirmed Cases: Estimation and Application. Ann Intern Med 172: 577-582. [crossref]

- Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, et al. (2020) Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia. N Engl J Med 382: 1199-1207.

- Bauch CT, Lloyd-Smith JO, Coffee MP, Galvani AP (2005) Dynamically modeling SARS and other newly emerging respiratory illnesses: past, present, and future. Epidemiology 16: 791-801. [crossref]

- Lei J, Kusov Y, Hilgenfeld R. (2018) Nsp3 of coronaviruses: Structures and functions of a large multi-domain protein. Antiviral Res 149: 58-74. [crossref]

-

Song W, Gui M, Wang X, Xiang Y (2018) Cryo-EM structure of the SARS coronavirus spike glycoprotein in complex with its host cell receptor ACE2. PLoS Pathog. [crossref]

- Angeletti S, Benvenuto D, Bianchi M, Giovanetti M, Pascarella S, et al. (2020) COVID-2019: The role of the nsp2 and nsp3 in its pathogenesis. J Med Virol 92: 584-588. [crossref]

- Ciceri F, Beretta L, Scandroglio AM, Colombo S, Landoni G, et al. (2020) icrovascular COVID-19 lung vessels obstructive thromboinflammatory syndrome (MicroCLOTS): an atypical acute respiratory distress syndrome working hypothesis. Crit Care Resusc 22: 95-97. [crossref]

- Conti P, Ronconi G, Caraffa A, Gallenga CE, Ross R, et al. (2020) Induction of pro- inflammatory cytokines (IL-1 and IL-6) and lung inflammation by Coronavirus-19 (COVI-19 or SARS- CoV-2): anti-inflammatory strategies. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 34: 327-331. [crossref]

- Tian S, Hu W, Niu L, Liu H, Xu H, et al. (2020) Pulmonary Pathology of Early-Phase 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pneumonia in Two Patients With Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 15: 700-704. [crossref]

- Zhang H, Zhou P, Wei Y, Yue H, Wang Y, et al. (2020) Histopathologic Changes and SARS-CoV-2 Immunostaining in the Lung of a Patient With COVID-19. Ann Intern Med 172: 629- 632.

- Menter T, Haslbauer JD, Nienhold R, Savic S, Hopfer H, et al. (2020) Post-mortem examination of COVID19 patients reveals diffuse alveolar damage with severe capillary congestion and variegated findings of lungs and other organs suggesting vascular dysfunction. Histopathology 77: 198-209. [crossref]

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, et al. (2020) Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395: 497-506.

- Wu Z, McGoogan JM. (2020) Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72 314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA 323: 1239-1242. [crossref]

- Kogan A, Segel MJ, Ram E, Raanani E, Peled-Potashnik Y, et al. (2019) Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome following Cardiac Surgery: Comparison of the American-European Consensus Conference Definition versus the Berlin Definition. Respiration 97: 518-524. [crossref]

- Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, et al. (2016) The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 315: 801-810. [crossref]

- Seymour CW, Kennedy JN, Wang S, Chang CH, Elliott CF, et al. (2019) Derivation, Validation, and Potential Treatment Implications of Novel Clinical Phenotypes for Sepsis. JAMA 321: 2003-2017.

- Matics TJ, Sanchez-Pinto LN (2017) Adaptation and Validation of a Pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment Score and Evaluation of the Sepsis-3 Definitions in Critically Ill Children. JAMA Pediatr 171

- Yang AP, Liu JP, Tao WQ, Li HM (2020) The diagnostic and predictive role of NLR, d-NLR and PLR in COVID-19 patients. Int Immunopharmacol

- Gattinoni L, Coppola S, Cressoni M, Busana M, Rossi S, Chiumello D (2020) COVID-19 Does Not Lead to a “Typical” Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 201: 1299-1300. [crossref]

- Hui DS, Chow BK, Lo T, Tsang OTY, Ko FW, et al. (2019) Exhaled air dispersion during high-flow nasal cannula therapy versus CPAP via different masks. Eur Respir J

- Wu CN, Xia LZ, Li KH, Ma WH, Yu DN, et al. (2020) High-flow nasal-oxygenation-assisted fibreoptic tracheal intubation in critically ill patients with COVID-19 pneumonia: a prospective randomised controlled trial. Br J Anaesth

- Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D, Liu W, Wang J, et al. (2020) A Trial of Lopinavir-Ritonavir in Adults Hospitalized with Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med 382: 1787-1799. [crossref]

- Gordon CJ, Tchesnokov EP, Feng JY, Porter DP, Götte M (2020) The antiviral compound remdesivir potently inhibits RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Biol Chem 295: 4773-4779. [crossref]

- de Wit E, Feldmann F, Cronin J, Jordan R, Okumura A, et al. (2020) Prophylactic and therapeutic remdesivir (GS-5734) treatment in the rhesus macaque model of MERS- CoV infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117: 6771-6776.

- Gautret P, Lagier JC, Parola P, Hoang VT, Meddeb L, et al. (2020) Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non- randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents [crossref]

- Zarogoulidis P, Papanas N, Kioumis I, Chatzaki E, Maltezos E, et al. (2012) Macrolides: from in vitro anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties to clinical practice in respiratory diseases. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 68: 479-503. [crossref]

- Mercuro NJ, Yen CF, Shim DJ, Maher TR, McCoy CM, et al. (2020) Risk of QT Interval Prolongation Associated With Use of Hydroxychloroquine With or Without Concomitant Azithromycin Among Hospitalized Patients Testing Positive for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol

- Kollias A, Kyriakoulis KG, Dimakakos E, Poulakou G, Stergiou GS, et al. (2020) Thromboembolic risk and anticoagulant therapy in COVID-19 patients: emerging evidence and call for action. Br J Haematol

- Buonaguro FM, Puzanov I (2020) Ascierto PA. Anti-IL6R role in treatment of COVID-19-related ARDS. J Transl Med

- Vittori A, Lerman J, Cascella M, Gomez-Morad AD, Marchetti G, et al. (2020) COVID- 19 Pandemic ARDS Survivors: Pain after the Storm?. Anesth Analg