Abstract

Detailed knowledge of hydrogeological and hydrochemical characteristics of coastal basins is the prime basis for improved water quality management. This review presents a detailed hydrochemical and hydrogeological reassessment of coastal basins of southwestern Nigeria. Results indicate that the Abeokuta group is the oldest Formation and comprises the Ise, Afowo, and Araromi Formations. Despite the marked spatial variability of these formations, their lithology remains relatively the same. Also crucial in this area is the deltaic Formation, which contains alluvial deposits. The Ogun and Osse-Owena Basins are the central coastal basins in western Nigeria. Though the Osse-Owena Basin has not been fully explored hydrogeologically, it is not associated with good groundwater storage, since basement complex rocks underlie it. These coastal basins were further grouped into the upper surficial aquifer system; and the intermediate aquifer system. Also found in this area is the crystalline Basement Terrain. From the hydrogeologic point of view, unweathered basement rock contains negligible groundwater; though, a significant aquiferous unit can develop within the weathered overburden and fractured bedrock. The general hydrogeological condition in the area showed that groundwater is very localized. These basins’ hydrochemistry showed groundwater is relatively good in terms of its suitability for drinking, industrial and agricultural uses. Groundwater classification based on physical parameters showed mixed results, though groundwater sources are most suitable for drinking. Due to the increasing urbanization and other forms of land use in the area, preventive measures must protect groundwater from depletion.

Keywords

The Abeokuta Group; The Ilaro Formation; The deltaic formation and alluvial deposits; Hydrogeological condition; Groundwater chemistry

Introduction

Water is an indispensable prerequisite of life deemed an economic resource rather than a social good [1-4]. Even though freshwater storage in the ecosystem remains steady, freshwater pressure such as subsurface water has experience expansion due to population increase, development, dry season farming, and household activities [1,5]. Though, the quality and quantity of this economic resource are likewise critical factors in the perspective of modern water quality management, especially in coastal areas [1,6,7]. Factors such as quality of recharge, rock weathering and mineralogical composition of the underlying rock types, land use, and climate change usually play a vital role in groundwater chemistry, affecting groundwater quality [1,8].Understanding groundwater evolution involves the hydrochemical analyses of major dissolved ions of groundwater, discovering the principal geochemical processes, and evaluating the impacts of land-use types on groundwater quality in various regions of the world [1,9,10]. Many factors such as rock-water interactions, climate changes, precipitation or dissolution of mineral species, the intensity of chemical weathering of the different rock types, groundwater resources, exchange reactions, and human activities, prolonged residence time in the aquifer and saltwater intrusion account for the variability of hydrochemistry of groundwater in coastal aquifers [1,11-14]. The hydrochemistry of coastal aquifers of southwestern Nigeria is highly variable due to variation in geological configurations and human activities. Groundwater contamination stemming from human activities, and inadequate sewage discharge is on the rise in Nigeria [15-17]. Consequently, groundwater utilized for domestic uses is problematic and hence calls for scientific scrutiny. Examining hydrochemistry and groundwater quality in coastal regions is crucial to monitor and detect groundwater contaminants sources [18-21]. Groundwater quality analysis in Abeokuta South, Nigeria by Emenike, Nnaji [17] showed that water quality parameters exhibited wide variations from location to location. Sodium, magnesium, iron (++), and EC showed the most violation of drinking water quality standards. Anthropogenetic actions are escalating threat to groundwater quality and thus call for routine monitoring of groundwater in Abeokuta. Statistical and hydrochemical modelling of groundwater quality southwestern Nigeria showed a conjunctive imprint of anthropogenic and geogenic activities influencing the increasing dissolved chemical constituents in the groundwaters [1]. Hydrochemical analysis of groundwater quality along the coastal aquifers of southwestern Nigeria revealed that the primary process influencing the hydrochemistry is saltwater invasion while mineral dissolution and rainwater infiltration play less significant roles [22]. Nitrate controls biogeochemical process over Fe, and its concentrations are above the World Health Organization’s (WHO) standard for drinking water in most water samples in the Shallow Coastal Aquifer of Eastern Dahomey Basin, Southwestern Nigeria [8]. Integrated geophysical and geochemical investigations of saline water intrusion in a coastal alluvial terrain of southwestern Nigeria by Oyeyemi, Aizebeokhai [23], showed a lateral invasion and up coning of saline water within the aquifer systems. The water is alkaline, and salinity is high with a very high electrical conductivity. The impact of anthropogenic activities over groundwater quality of a coastal aquifer in Southwestern Nigeria indicated some metals such as Cu, Fe, Mn, Al, Zn, Pb, As, Cd, Cr and H2S) were detected in only some shallow wells. However, the effects on public health are still undocumented. The drainage, geology, chemistry and associated human factors play a vital role in the extent of shallow groundwater contamination in the area [24]. Potential sources of contaminants to the groundwater such as weathering of bedrocks, leachate from septic tanks and dumpsites, runoff of materials, hardness, nutrients from agricultural lands, and chlorine pollution were identified in basement rocks of Osun State, Southwest, Nigeria [25]. Groundwater in Abeokuta Southwestern, Nigeria, is not suitable for drinking but has good irrigation quality [26]. Assessment of the risks of groundwater pollution in the coastal areas of Lagos, southwestern Nigeria, showed that the lower aquifer is mostly affected with saline water intrusion while the phreatic aquifer pollutions are both from anthropogenic and saline sources [27]. While the hydrochemistry of coastal aquifers is well researched, studies combining the hydrogeological and hydrochemical analysis of groundwater are rare. This review presents a detailed hydrogeological and hydrochemical analysis of coastal basins of southwestern Nigeria.

Geographical Setting

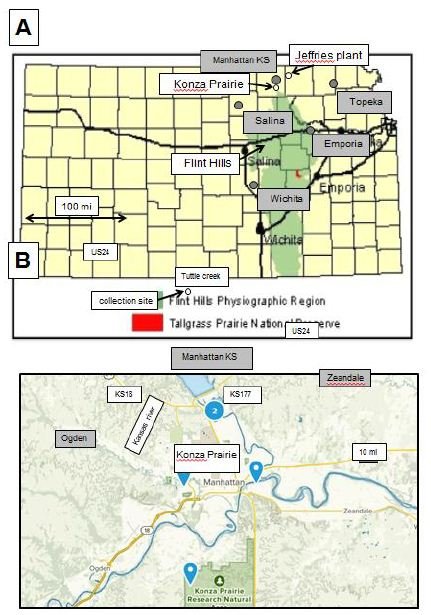

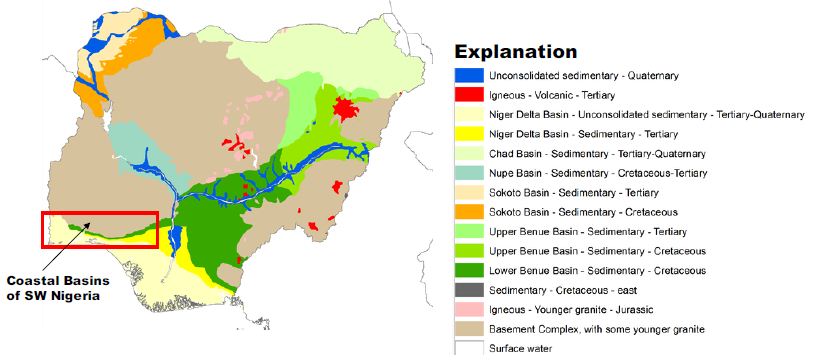

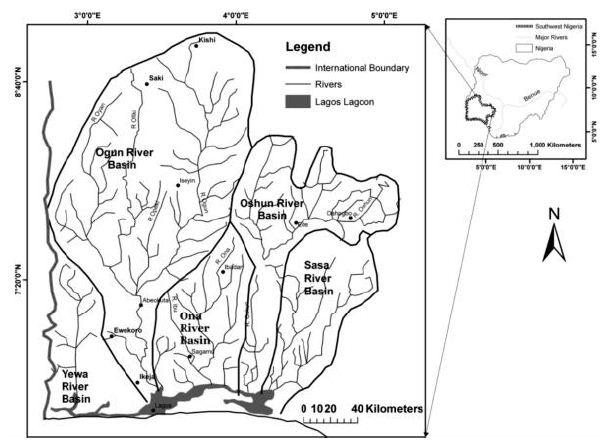

Southwestern Nigeria’s coastal basins constitute the Benin Embayment’s eastern portion, forming an arcuate coastal basin [28-30]. The onshore parts underlie the coastal plains of southwestern Nigeria, Benin, and Togo [31]. The Okitipupa Basement Ridge separated the Benue Trough’s embayment until the Campanian-Maastrichtian period when subsidence and marine transgression united the two basins (Figure 1). Some basement chunks that underlie the Dahomey Embayment are displaced towards the basin’s northern and southern axis and the offshore [31]. An inventory of water resources in southwestern Nigeria confirms that water supplies are generally from surface sources, such as dams and weirs in streams and rivers. Borehole and shallow-wells, tapping groundwater, are used to complement the short supply from surface water. Existing data from UNICEF-water assisted projects suggests that boreholes in southwestern Nigeria are intended to tap water from the weathered regolith or the jointed/fractured basement rock aquifers. The Coastal Basins are comprising of the Osse, Ogun and Yewa River Basins.

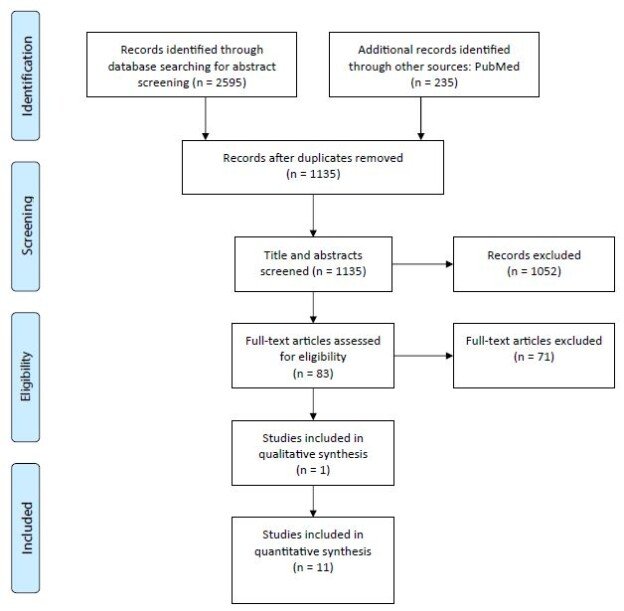

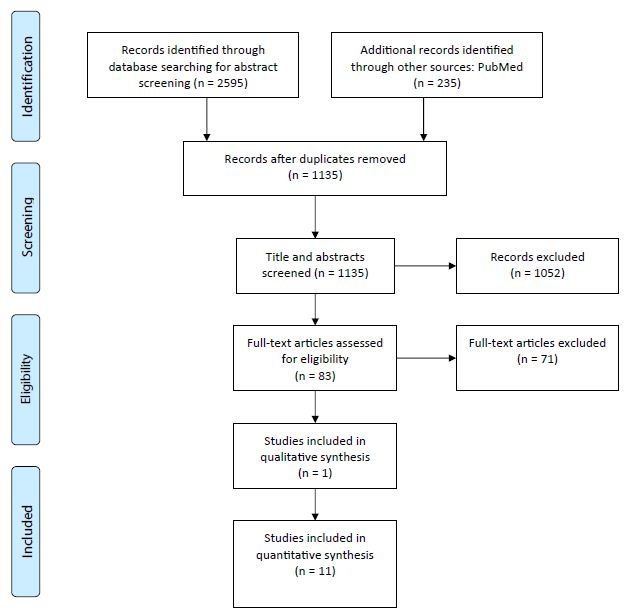

Figure 1: Coastal Basins of Southwestern Nigeria. After Ola-Buraimo, Oluwajana [31].

These basins are grouped as the geological formations outcrop parallel to each other in an east-west direction and transgressing the basins in the same Coastal River Basins. The Osse River Basin is about 51400 sqkm in landmass. On the other hand, the Ogun River Basin has about occupied an area of about 88800 sqkm. The two basins are drained by many dendritic flowing streams, which empty their water into the sea. The Osse Basin is perhaps the lateral equivalent of the Benin-Owena River Basin [32]. The main drainage in the Osse-Osiomo systems is little streams and rivulets flowing straight into the sea and forming part of the Delta composite. Parallel streams with the same pattern drained the Ogun Basin, most protuberant being the Ogun, Osun, and Yewa river systems. This basin’s climate is archetypally coastal with very high rainfall, ranging from 2250 mm in the north to over 2600 mm along the coastal line. The relative humidity is very high, >80%. The mean annual temperature is about 21°C [32].

Geological Setting

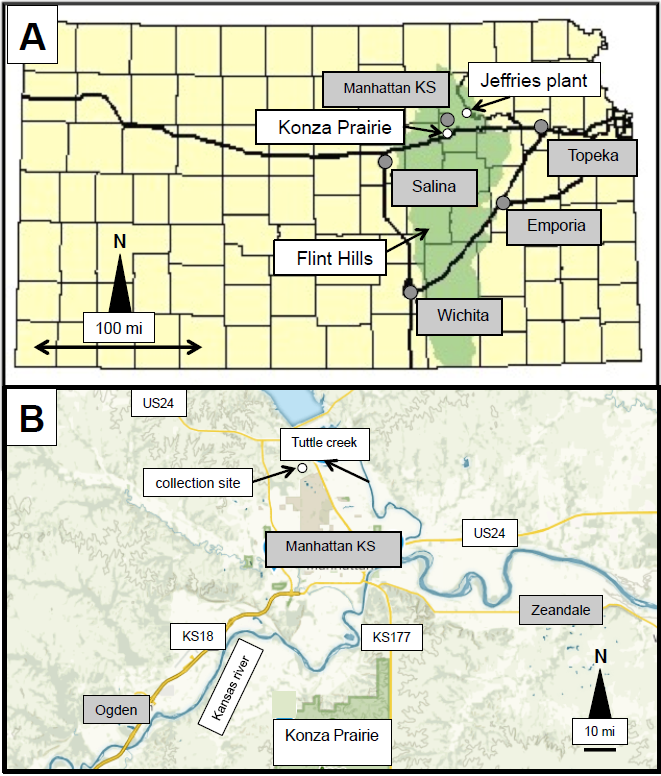

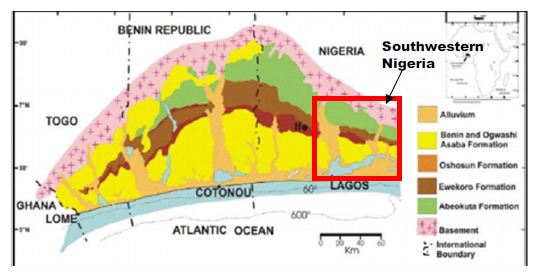

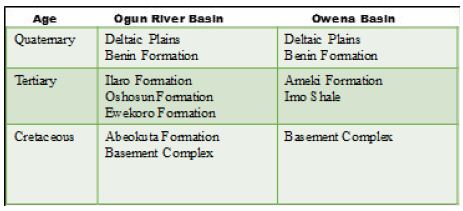

The coastal basin of southwestern Nigeria is restricted to the west by the Ghana ridge, which is an extension of the Romanche Fracture Zone; and eastwards, by the Benin Hinge line, a basement escarpment which splits the Okitipupa Structure from the Niger Delta Basin and also marks the inland extension of the Chain Fracture Zone (Figure 2). The Nigeria portion of the basin spreads from Nigeria’s boundary and Benin’s Republic to the Benin Hinge Line. The stratigraphy of the sediments in the Nigerian sector of the Benin Basin is contentious. Different stratigraphic names have been suggested for the same Formation in different localities within the basin [31]. This problem can be attributed to the lack of adequate borehole reporting and satisfactory outcrops for comprehensive stratigraphic studies. As a result, the stratigraphy of the entire basin was divided into three chronostratigraphic compendia. These are (i) pre-lower Cretaceous folded sediments and (ii) Cretaceous sediments and Tertiary sediments (Figure 3).

Figure 2: The Nigerian portion of Dahomey (Benin) Basin. After Ola-Buraimo, Oluwajana [31].

Figure 3: A Lithologic section of Arimogija – Okeluse exposure. After Ola-Buraimo, Oluwajana [31].

In the Nigerian sector of the basin the Cretaceous sequence, as compiled from outcrop and borehole records, consists of the Abeokuta Group, further divided into three geologic units: Ise, Afowo, and Araromi Formations. Ise Formation overlies the basement complex unconformably and comprises of coarse conglomeratic sediments [33,34]. Afowo Formation is composed of transitional to marine sands and sandstone with variable but thick interbedded shales and siltstone [35,36]. Araromi is the uppermost Formation and comprises shales and siltstone with interbeds of limestone and sands. The Tertiary sediments comprise Ewekoro, Akinbo, Oshosun, Ilaro, and Benin (bare coastal sand). The Ewekoro Formation comprises fossiliferous, well-bedded limestone while Akinbo and Oshosun Formations are made up of flaggy grey and black shales [37,38]. Glauconitic rock bands and phosphatic beds define the boundary between the Ewekoro and Akinbo Formations. The Ilaro and Benin Formations are predominantly coarse sandy estuarine, deltaic, and continental beds [31].

The Abeokuta Group

The sedimentary Formation of southwestern Nigeria, otherwise known as the Eastern Dahomey Basin, extending from the Nigeria/Benin border in the west of Makun-Omi and broken in the east. The Abeokuta Group is the oldest Formation, and it comprises of main sands with intercalations of argillaceous sediments, which lie unconformably on the crystalline basement complex formation [39,40]. This group can be subdivided into three geologic units;

- The lse Formation, which overlies the basement complex and consists of pre-drift sediments of grits and siltstones and overlain by coarse-medium grained, loose sands interbedded generally by kaolinitic clays;

- The Afowo Formation comprises intermediate to marine sands and sandstone with variable but thick interbedded shales and siltstones. The shale to sand ratio Increase upwards with the sediment becoming highly fossiliferous. The whole arrangement represents paralic sedimentation; and

- The Araromi Formation, which is the youngest of the stratigraphic sequence, comprises shales and siltstones with Interbeds of limestone and sands. It Is opulently fossiliferous.

The Abeokuta Formation usually has a basal conglomerate with about 1 meter thick and mostly comprises poorly rounded quartz pebbles with a silicified and ferruginous sandstone matrix or a soft gritty white clay matrix [39]. The formation outcrops where there is no conglomerate, a coarse, poorly sorted pebbly sandstone with copious white clay establishes the basal bed. The superimposing sands are coarse-grained, clayey, micaceous, and ill-sorted, suggestive short distances of transportation, or short duration of weathering and possible derivation from the granitic rocks located to the northwards. Upward stratigraphically along with the outcrop areas, the shale content increases progressively in some places, particularly around Ijebu-Ode. Close to the embayment’s eastern margin, thin beds of lignite may be present together with a high impregnation of bitumen in the sand and clays. These features are displayed in most of the eastern part of the embayment, locally referred to as Tar sand. The basal beds’ upper horizons were found in some outcrops to contain thin beds of Oolitic ironstone. The stratigraphic dating from palynological studies indicates that the ages of the lower and upper limits of the neostratotype Formation are late Albian and late Senonian. This is a characteristic species for the late Turonian-early Senonian of the Ivory Coast and was reported from Gabon’s Coniacian-Campanian. Therefore, this pollen occurrence implies a late Senonian age for the Formation’s upper layers [39].

The Ise-Afowo, Araromi, Akinbo, and Ilaro Formations

Ise and Afowo Formations are similar; thus, the two geologic units are treated together in most literature [39,41,42]. The two formations contain sand and sandstones, but the latter is interbedded by thick of shale units. Similarly, the Ise, Afowo, and Abeokuta Formations showed a similar lithologic and electric log. The uppermost beds of Abeokuta Formation which outcrop in the Ijebu-Ode, Itori, Wasimi, and Ishaga, consist mainly of fine-coarse-grained sand which is occasionally interbedded by shale, mudstone, limestone, and silt. In most recent literature the Ise and Afowo Formations are discussed as Abeokuta Formation. The Abeokuta Formation consists mainly of grits, loose sand, sandstone, kaolinitic clay, and shale. It was further characterized as usually having a basal conglomerate or a basal ferruginised sandstone [39]. The Araromi Formation overlies the Afowo Formation and has been described as the youngest Cretaceous sediment in the eastern Dahomey Basin. It is composed of fine to medium-grained sandstone at the base, overlain by shales, siltstone with interbedded limestone, marl, and lignite. This Formation is highly fossiliferous [43]. The Ewekoro Formation overlies the Araromi Formation. It is an extensive limestone body, which is traceable over a distance of about 320 km from Ghana in the west, towards the eastern margin of the Dahomey (Benin) Basin in Nigeria [44,45]. It is Palaeocene in age. Superimposing the Ewekoro Formation is the Akinbo Formation, which is mainly composed of shale and clayey sequence. The clay stones are concretionary and are largely kaolinite. The Formation’s base is defined by the presence of a glauconitic band with lenses of limestones [43]. The Akinbo Formation and consists of greenish-grey or beige clay and shale with interbeds of sandstones. The shale is thickly laminated and glauconitic. The basal beds may consist of either, sandstones, mudstones, claystones, clay-shale, or shale. The Ilaro Formation superimposes the Oshosun Formation and consists of massive, yellowish poorly, consolidated, cross-bedded sandstones. The youngest stratigraphic sequence in this basin is the Benin Formation, otherwise known as the Coastal Plain Sands and contains poorly sorted sands with layers of clay units. The sands are occasionally interbedded and show transitional to continental characteristics. The age is from Oligocene to Recent [43]. Most of the boreholes constructed in the basin are either single-screened or multiple-screened and occasionally open wells are constructed through fractured basement rocks that produce a considerable amount of water. The Depth to water level hardly exceeds 24 meters. Most aquifers in this basin are found around 40 meters below the surface. These aquifers are rarely confined, and very few boreholes tap water below 60 meters [46]. The mean yield from boreholes is ~0.4 l/s. In the crystalline basement section of the basin, a borehole depth of 40–80 m is estimated. Data from available boreholes in the southern end of Kwara State extending to Osun State, indicate the range between 25–68 meters borehole depth. The overburden thickness is also highly variable, ranging between 3–24 meters. In places around Ibadan, the overburden thickness and borehole depth are within the same range. The thickness of the overburden aquifer in the rural areas of Oyo State is correlated to the tectonic fractures rather than weathering (regolith).

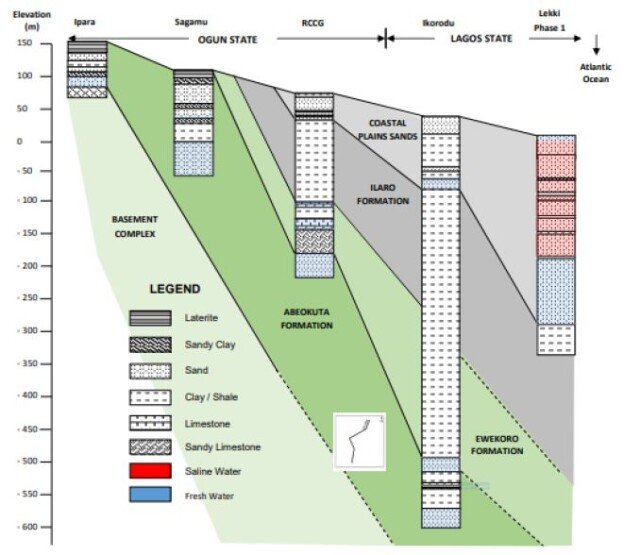

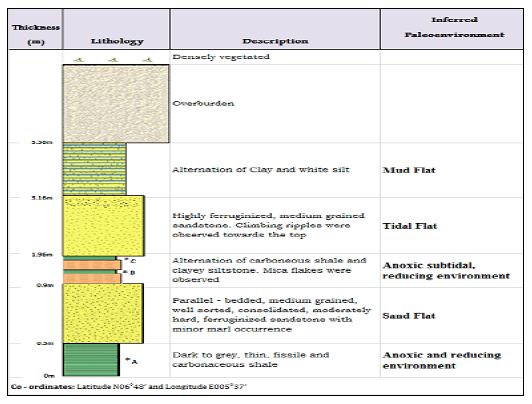

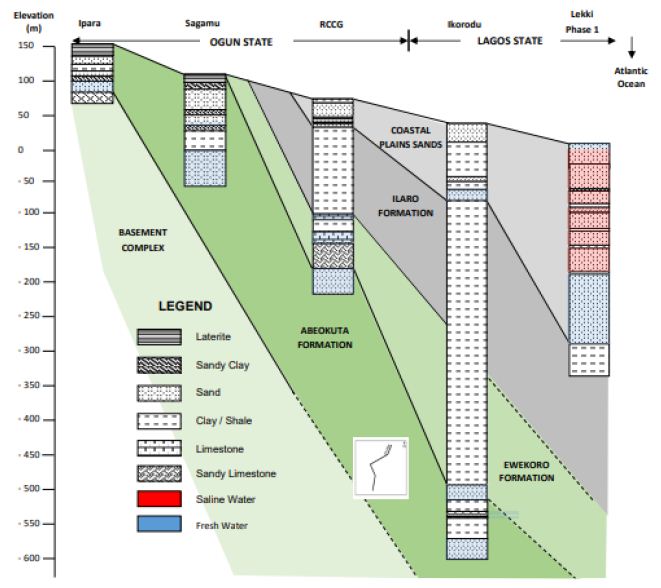

Borehole yield ranging from 1–2 l/s in the basement complex section is considered suitable for installing motorized submersible pumps. Borehole yields less than 0.5 l/s are also considered good for handpumps. The recharge into the weathered aquifer is predominantly through the infiltration of rainwater. Therefore, continued yields from motorized pumps may not be workable. Midwestern Nigeria’s coastal basin’s principal aquifers occur in sandy units and overburden/superficial deposits confined by shale and clay formations. The aquifers’ thickness is highly variable with first and third horizons reaching a thickness of about 200 meters and 250 meters at Lekki headland. The second horizon is roughly 100 meters thick (Figure 4). The estimated groundwater stored in the first aquifer horizon is about 2.87 × 103 m3. The water table is mostly shallow, ranging 0.4–21 meters below the ground surface. It is estimated that annual fluctuation is less than 5 meters. The principal aquifer is within bare coastal sands, occasionally underlain by impermeable horizons of shale and clay units. Many high-yielding boreholes provide more than 30% of the water supply in Lagos and its hinterlands [46].

Figure 4: Typical hydrogeological section of coastal basins of southwestern Nigeria. After Adelana, Vrbka [46].

The geological succession in these basins simple, forming a simple monocline against the basement outcrop northward, with a slight faulting indication. The inclines are reportedly about 1° or less southwestwards (Table 1). The Basement Complex rocks superimpose more than 50% of the Coastal basins [47-49]. The Abeokuta Formation is the oldest outcropping sedimentary formation in the Ogun and Osse River Basin. This appeared to cover the basement complex directly. The Formation is in turn superimposed by the Ewekoro, Ilaro, and Benin Formations. The is the substantial development of alluvium in the coastal areas and along the course of the major drainage systems of the Rivers Ogun and Osse.

Table 1: Hydrogeology of coastal basins of southwestern Nigeria.

After Offodile [32]

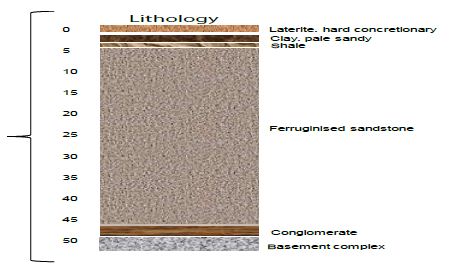

The Abeokuta Formation

This is the oldest Formation in the Ogun Basin, outwardly covering the Basement Complex. The Formation thickness ranged from 250 to 300 meters, containing arkosic sandstones and grits, tending to be carbonaceous towards the bottom. There is an increase in thickness from about 250 meters in the western sections of the basin towards the Benin border. The basal conglomerates also were encountered. One of the outcrops gave the following units in Figure 5. The Abeokuta Formation has good potential for groundwater except that the bituminous constituents associated with the sands could affect groundwater quality. This Formation is being interrelated to the Nkporo Shale, east of the River Niger. The little report is existing about the groundwater potentials of the Abeokuta Formation. Nevertheless, its proximity to the Basement Complex and its high porosity, a substantial amount of groundwater is expected to be stored above the crystalline rock layer. This condition has been confirmed at the bottom near the Basement layer, intercepted by the borehole described in the following section. This Formation is outstanding in the basin. Hydrogeologically, groundwater in the basin’s northern parts is limited to the splintered and in-situ worn portions of the rocks. The in-situ worn portion either superimposes the unweathered basement or occurs within the unweathered basement [50].

Figure 5: Section of Abeokuta Formation. After Offodile [32].

In the former, the worn materials create phreatic aquifers typically exploited through hand-dug shallow wells, while in the later, groundwater is confined in nature and can only be accessed through boreholes. Groundwater flow is strongly influenced by topography and two common types of springs, mainly, overland and slope springs have been observed in the area. Recharge to these aquifers is primarily by infiltrating rainfall and in some places, by the outflow from adjacent surface water. The recharge areas comprise decayed and splintered rocks in which pressure heads quickly spread through local water-bearing fractures and unified voids, thereby leading to an abrupt rise in ejections in response to rain. Spring discharges in the northern parts of the basin are very common in the rainy season but terminate totally during the dry season. The area underlain by sedimentary formations is regarded as having good groundwater potential due to an aquiferous sandy layer [50].

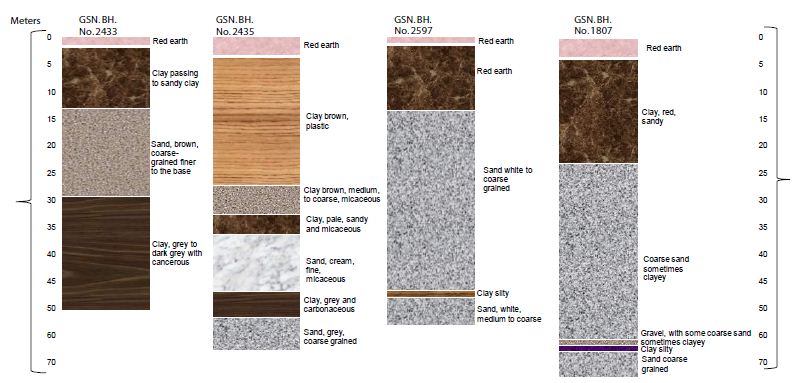

However, the success of boreholes in this basin is highly variable, and it could be credited to inferior drilling methods, or the frequent occurrence of the clayey matrix, which extends to seal the pores and reduce the absorptivity. The successful boreholes were reported from Aiyetoro and Ijebu Ode. Also, specific capacity ranging from 63 to 17550 list/hr/m (1300 gift) have been measured. Successful boreholes were also reported from Iboro, Imushin, and Ishaga as depicted below. In the eastern parts, within the Osse Basin, the Abeokuta Formation appears to thicken in Agenebode and Auchi’s higher regions, where the groundwater table is deep (120-300 meters). The low water table recorded is thought to be due to the aquifer’s high porosity, as typified in by the Kerri-Kerri Formation, in the Upper Benue Basin Nanka Sands of the Anambra Basin [32]. Some drilled boreholes in the Abeokuta Basin are shown in Figure 6. Figure 7 illustrates some successful boreholes in Abeokuta Formation. The GSN. BH. No. 2436 is located at Meko. The lies unconformably showed unconformity. It has a total depth of 57.9 meters. Although it penetrates the Basement Complex, yields are relatively low (1620 lits/hr (0.45 lits/sec)—the GSN. BH. No. 2612 was located at Igbogila. The borehole penetrates a Basement Complex section and has a total depth of 70.5 meters. Yield is relatively high (28350 lits/hr), or 7.87 lits/sec. it has a specific capacity of about 390.8 lits/hr—the GSN. BH. No. 2438 is located at Aiyetoro. The borehole penetrated a Basement Complex formation and showed unconformity. The total depth is about 55.9 meters. Yield is relatively low (2340 lit/hr), or 0.65 lits/sec (Offodile, 2002). Figure 7 further illustrates some boreholes penetrating the Abeokuta Formation. The GSN. BH. No. 2433 reached a depth of 48 meters below the ground level. This borehole’s actual location is unknown, but it is believed to penetrate the Abeokuta Formation. The borehole produced a yield of about 3600 lits/hr and had a specific capacity of 11880 lit/hr/m (Offodile, 2002). The GSN. BH. No. 2435 is located at Ishaga. It penetrated the basement complex (BC) and had a total depth of 75 meters. It had a yield of 31050 lits/hr. It also had a specific capacity of 3192.75 lit/hr/m [32]. The lithology is mainly sandy (Figure 7) – the GSN. BH. No. 2597 is located at Ijebu Ode about 46 km NE of the town. The borehole penetrated the BC and reached a depth of 54.6 meters. The yield obtained from this well is comparatively low (10800 lits/hr), with a specific capacity of 935.5 lits/hr/m. The last borehole in Figure 6 (GSN. BH. No. 1807), also lies unconformably on the BC. The well reached a depth of 72.8 meters and produced a yield of 13500 lits/hr, with a specific capacity of 4039.2 lit/hr/m [32]. Generally, boreholes penetrating the Abeokuta Formation has a higher proportion of sands.

Figure 6: Lithological sections of boreholes in Abeokuta Formation. After Offodile [32].

Figure 7: The lithology of boreholes in Abeokuta Formation. After Offodile [32].

The Ilaro Formation

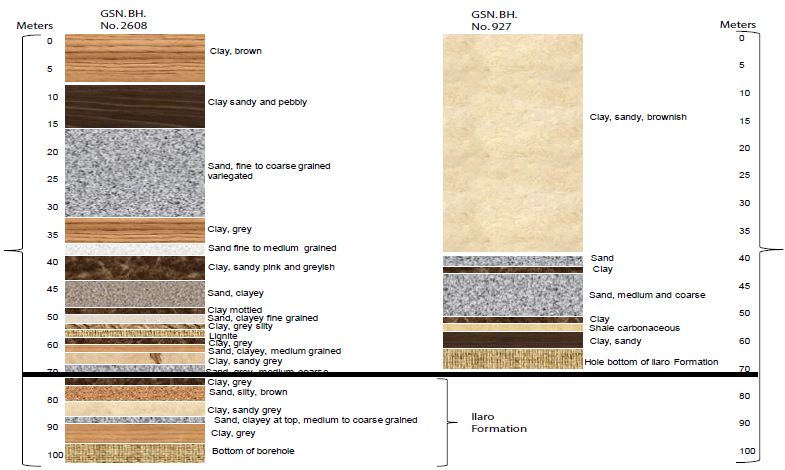

The Ilaro Formation is comprised of fine to medium-grained which are reasonably well sorted. The Formation lies conformably on the Oshoshun Formation (Lower-Middle Eocene) and locally unconformably underneath the Benin Formation -Oligocene-Pleistocene [51-53]. The Ilaro Formation is typically Middle to Upper Eocene in age. The estimated thickness of this Formation is about 70 meters and displays rapid lateral facies changes. This can affect aquifer quality [54]. Hydrogeologically, not much information exists on the Ilaro Formation, though it is reported to be transitional to, and in part equivalent to the Ameki Formation. Given the Ilaro Formation’s geological physiognomies, its equivalent lateral part could be a good aquifer that can yield a substantial amount of water. However, GSN. BH. No. 2611 in Ilaro had reached a depth of 57 meters and gave a low yield of 2975 lits/hr and a specific capacity of 1023 lits/hr/m [32]. The lithology of this borehole is illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8: The lithology of the borehole in Ilaro. After Offodile [32].

The Benin Formation

The Benin Formation (Miocene-Recent) consists of thick bodies of ferruginous and white sands. The Formation lies conformably on Ilaro Formation. Friable, poorly sorted with intercalation of shale, clay, and sandy clay with lignite [55]. The Benin aquifer is an important reservoir of groundwater. It is well developed in the Osse Basin and underlies more than 50% of its sedimentary section. The Benin aquifer is underlain by the sandstones of and shales of the upper Ilaro Formation, consists of a sequence of predominant continental sands and some lenses of shales and clays proved to be up to 107.7 meters thick in the area. The cross-section of the Benin Basin is further illustrated below. The Benin Aquifer gives very high yields of up to 4500 lits/hr (10000 g/hr) in most parts of the outcrop area.

The water table is relatively shallow, ranging between 20 to 25 meters. The water quality is also good. By this Formation, the land area underlain extends from Ado-Odo, Ilaro, Ikeja, and Mushin, passing through Okitipupa of Ogun Basin, into a broad area Benin-Ugheli-Agbo province of Osse Basin, in Edo and Delta States [32]. The lithology of boreholes from the Benin formation is illustrated in Figure 8. The GSN. BH. No. 2608 is located at Ikeja, had a total depth of 99 meters. The yield from this borehole is comparatively high (55350 lits/hr) [32]. Figure 9 illustrates the lithology of Benin formation [56].

Figure 9: Hydrogeologic Cross-section of the Benin Basin. After Oteri and Ayeni [56].

Figure 10 shows the specific capacity of this borehole is 9,220 lits/hr/m. This well penetrates the Benin Formation. The GSN. BH. No. 927 is located in Otta. The well had a depth of 243 meters. The remaining lithologies were not accessed. Yield from this borehole was estimated to be 22500 lits/hr in GSN. BH. No. 2599, located at Mushin penetrates a similar sequence, attained a depth of 108.6 meters. This well gave a yield of 32850 lits/hr (9 lits/sec). The specific capacity was 1930.5 lits/hr/m. This prolific yield is typical of the Benin Formation across the southwestern river basins of Nigeria. The Benin Formation is also very important in the Osse Owena Basin, where it is the primary groundwater source [32].

Figure 10: The lithology of the borehole in Ikeja and Otta. After Offodile [32].

The Deltaic Formation and Alluvial Deposits

This Formation contains alluvial deposits associated with Lagos’ coastal areas and the Osse Basin areas connecting to the Niger Delta Basin [57-59]. The hydrogeological conditions in areas were explained in studies on the Niger Delta Basin. Be sufficient to mention that the sandstone beds are limited in thickness and usually variable in the lateral extent. Furthermore, these aquifers have been exposed to saline water intrusion due to overdevelopment and seawater invasions. Correspondingly, the limitations in thickness and extent of the aquifers significantly reduce the boreholes’ specific capacity. The groundwater condition varies swiftly across the basins. In the Lagos region areas where the Formation appears to be least developed and has been polluted, the underlying Benin Formation provides a ready supply to the groundwater demand in the basin [32]. These comprise the Yewa, Ogun, and Oshun river networks’ vast basins, presenting a general alluvial development with considerable groundwater potential. The available drilling records have not distinguished this Formation. However, a 49275 lits/hr yield from GSN. BH. No. 2610 at Ibefun. The borehole was just 28.5 meters deep and had a specific capacity of 9234 lits/hr/m. This presents an excellent yield and underlines the high potential of these river basins’ alluvial deposits. The hydrogeology of these basins is similar to that of the Niger Delta Basin, discussed in the previous chapter.

Hydrogeological Condition in Coastal Basins of Southwestern Nigeria

The Ogun River Basin

The Ogun River Basin is one of the significant coastal basins located in southwestern Nigeria [60-62]. The basin is situated between latitudes 6° 26′ N and 9° 10’N and longitudes 2° 28’E and 4° 8 ‘E (Figure 11). About 98% of the basin area falls within Nigeria and the remaining 2% in the Benin Republic. The basin covers an of about 23,000 sqkm. The topography is generally low, with the gradient in the north-south direction. The Basin is drained by the Ogun River which had its source from the Iran hills at an elevation of about 530 meters above sea level. The river flows southwards over a distance of about 480 km before it discharges into the Lagos lagoon. The main tributaries of the Ogun River are the Ofiki and Opeki Rivers. Two seasons are distinguishable in the Ogun River Basin; a dry season from November to March and a wet season between April and October. The mean annual rainfall ranged from 900 mm in the northern parts to 2000 mm in the south. The total annual potential evapotranspiration ranged from 1600 and 1900 mm [63]. Hydrogeologically, very little is known about the Ogun Basin since the basin is often discussed in southwestern Nigeria’s coastal basins. However, Offodile [32], compiled data on borehole on borehole depths summarized in Table 2. There is not much reporting of hydrogeological physiognomies of the individual boreholes from western Nigeria’s coastal basins. Most of the boreholes in this basin penetrate the Pre Cambrian-Basement Complex. Yields from these boreholes are poorly known. However, GSN. BH. No. 2614 in Ewekoro gave an artesian flow of 90-135 lits/hr obtained near the borehole base. Similarly, GSN. BH. No. 1583 at Itori gave artesian flow at 81 meters. The estimated yield was 450 lits/hr and a specific capacity of 92.7 m 45000 lits/hr/m. Although, these two boreholes produced a substantial amount of water, a more detailed study on the hydrogeology Ogun Basin is required for further evaluation.

Figure 11: Ogun-Osun River Basins and the Adjacent Basins. After Oke, Martins [63].

Table 2: Borehole information from Ogun Basin.

| S/no. |

Borehole Locality (Abeokuta Formation) |

GSN. BH. No. | Total Depth (m) | Depth to First Water (m) | Final Depth to Water (m) | Yield (lits/hr) | Draw Down (m) | Specific Capacity (lits/hr/m) |

Remarks |

| 1 |

Aiyetoro 2 |

2438 | 63 | 31.2 | 31.2 | 2340 | 15 |

Pre Cambrian-45.9-63 m |

|

| 2 |

Aiyetoro 2 |

2439 | 53.7 | 20.7 | 20.7 | 18900 | 3.6 | 5250 |

Pre Cambrian-45.9-63 m |

| 3 |

Ijebu Ife |

1808 | 57 | 42 | 39.9 | 10655 | 10.6 | 1035 | |

| 4 |

Ijebu Ode |

2620 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Abandoned Pre Cambrian-Very shallow |

| 5 |

Ijebu Ode |

2597 | 69.9 | 46.2 | 46.2 | 10800 | 11.4 | 945 |

Pre Cambrian-54.6-69.6 m |

| 6 |

Ijebu Ode |

2598 | 54 | – | – | – | – | – |

Abandoned Pre Cambrian-18.3-54 m |

| 7 |

Imushin |

1807 | 87 | 55.8 | 52.8 | 13500 | 3.3 | 4080 |

Pre Cambrian-72.9-87 m |

| 8 |

Imushin |

2616 | 75.9 | – | 51.9 | 35100 | 1.8 | 19500 |

Pre Cambrian-65.4-75 m |

| 9 |

Ishage |

2435 | 75 | 29.1 | 19.8 | 31050 | 9.6 | 3225 |

Pre Cambrian-67.8-75 m |

| 10 |

Meko |

2436 | 57.9 | 42.3 | 42.3 | 1620 | 10.5 | – |

Pre Cambrian-54.6-57.9 m |

| (a) Borehole Locality (Fugar Area) | |||||||||

| 11 |

Agenebodo |

2604 | 127.2 | 105.9 | 105.9 | – | – | – |

Not tested |

| 12 |

Fugar |

1136 | 69.3 | – | – | – | – | – |

Abandoned |

| 13 |

Fugar |

1179 | 157.5 | – | 129.6 | 4500 | – | – |

– |

| 14 |

Fugar |

2603 | 157.8 | 129.6 | 129.6 | – | – | – |

Not tested |

| 15 |

Ogbona |

2613 | 213 | – | 183.3 | – | – | – |

Not tested |

| (b) Borehole Locality (Ewekoro Formation) | |||||||||

| 16 |

Ewekoro |

2614 | 90 | – | – | 58500 | – | – |

Artesian flow 90-135 lits/hr Obtained near the bottom of the hole |

| 17 |

Iboro2 |

2433 | 48 | 13.5 | 10.2 | 36000 | 3 | 1200 |

– |

| 18 |

Labour |

2434 | 33.6 | – | – | 32850 | 3 | 10950 |

– |

| 19 |

Ifon2 |

2602 | 79.5 | 64.5 | 61.8 | 12600 | 2.1 | 6000 |

– |

| 20 |

Igbogila2 |

2612 | 70.5 | 11.4 | 10.2 | 28350 | 11.7 | 2415 |

– |

| 21 |

Itori |

1583 | 96 | – | – | – | – | – |

Artesian flow at 81 m, 450 lits/hr; at 92.7 m 45000 lits |

| 22 |

Yemoji |

1590 | 348 | – | – | – | – | – |

– |

| (c) Borehole Locality (Ibeshe Area) | |||||||||

| 23 |

Ibeshe2 |

2437 | 121.2 | 57.5 | 57.9 | 10.26 | 9.3 | 1095 |

– |

| 24 |

Ilaro |

2611 | 132.9 | 17.4 | 20.4 | 26.55 | 22.5 | 1170 |

– |

| (d) Borehole Locality (Imo Shale) | |||||||||

| 25 |

Sabon Gida |

2601 | 121.2 | 41.4 | – | 13.05 | 51 | 255 |

Artesian flow 900 to 1350 lits/hr |

After Offodile [32]

The Osse Owena Basin

Also known as the Benin-Owena, River Basin occurs in Edo-State. The basin is situated within the Western Littoral Hydrological Area HA-6, one of the eight hydrological areas into which Nigeria is subdivided. The gauge station at which the hydrometric measurements were made is located at Osse River at Iguoriahki [64-66]. Hydrogeologically, this basin has not been well explored. Earlier, Offodile [32] summarised borehole information on this basin. Base on the borehole information presented in Table 3, it is clear that this basin has not been fully explored hydrogeologically.

Table 3: Borehole information from Osse Owena Basin.

| Borehole Locality (Ameki Formation) |

GSN. BH. No. |

Total Depth (m) | Depth to First Water (m) | Final Depth to Water (m) | Yield (lits/hr) | Draw Down (m) | Specific Capacity (lits/hr/m) |

Remarks |

|

| 1 | Asaba |

– |

72 |

27.6 | 23.1 | 8325 | – | – |

– |

| 2 | Asaba |

– |

72 |

22.5 | 25.5 | 9450 | 3 | 31 |

– |

| 3 | Asaba |

– |

67.5 |

16.5 | 17.4 | 18000 | – | – |

– |

| 4 | Asaba |

– |

45.6 |

25.2 | 22.2 | 95850 | 3 | 31950 |

– |

| 5 | Asaba2 |

– |

44.7 |

26.4 | 24 | 95850 | 4.2 | 22815 |

– |

| 6 | Isse-Uku |

– |

112.5 |

102.5 | – | – | – | – |

Abandoned |

| 7 | Isse-Uku |

– |

120 |

– | – | – | – | – |

Abandoned |

| 8 | Iuue |

– |

241.5 |

– | – | – | – | – |

Abandoned |

| 9 | Ogwashi-Uku |

– |

89.7 |

– | – | – | – | – |

Abandoned |

| 10 | Uburu |

– |

114 |

– | 108.5 | – | – | – |

Abandoned |

| Borehole Locality (Benin Formation) | |||||||||

| 11 | Abafon |

– |

45.6 |

– | 41.4 | – | – | 16.67 |

– |

| 12 | Ado Odo |

– |

96 |

– | I1 | 45000 | 2.7 | 9990 |

– |

| 13 | Ado Odo |

– |

– | – | – | ||||

| 14 | Agbon |

– |

63 |

– | 45 | 40500 | – | – |

– |

| 15 | Agbon |

– |

75 | – | 7.5 | 45000 | 4.5 | – |

– |

| 16 | Agbon |

– |

75 | – | 7.5 | 45000 | – | 32.13 |

– |

| 17 | Benin City |

– |

110.4 | – | 56.4 | 29.25 | – | 27.55 |

– |

| Borehole Locality (Ameki Formation) | |||||||||

| 18 | Benin City |

– |

61.8 | – | 15 | 67500 | 2.1 | – |

– |

| 19 |

Ethiope |

– | 34.5 | – | 10.5 | 49500 | 1.8 | – |

– |

| 20 | Sapele |

– |

37.5 | – | 4.8 | 31500 | – | – |

– |

| 21 | Sapele |

– |

37.5 | – | – | – | – | – |

No Data |

| 22 | Sapele |

– |

37.5 | – | 5.1 | 27000 | – | – |

– |

| 23 | Sapele |

– |

– | – | – | – | – | – |

No Data |

After Offodile [32]

The Osun River Basin

The Osun basin is drained by the Osun River system which rises from Oke-Mesi ridge, about 5 km North of Effon Alaiye along the Oshun and Ekiti States border and flows North through the Itawure gap to latitude 7° 53′ before winding its way westwards through Oshogbo and Ede and Southwards to enter Lagos lagoon about 8 km east of Epe [63,67]. A considerable part of the basin is underlain by rocks of the Precambrian Basement Complex, most of which are very ancient. This Basement Complex rocks showed significant variations in grain size and mineral composition [63]. The rocks are quartz gneisses and schist consisting essential of quartz with small amounts of white micaceous minerals. Even though the outcrops are visible, large areas are overlain by layers of laterite soil formed by weathering and decomposing the parent rock material. The minerals’ origin has been dealt with based on heavy mineral studies along the river basin. Moreover, the sedimentary rocks of Cretaceous and Tertiary deposits are found in the southern sector of the basin [63]. Generally, in coastal basins of southwestern Nigeria, groundwater is contained in four principal aquifers [56]:

- The first is the shallow aquifer, which contained the Recent Sediments along the Atlantic Sea coast and river valleys. It is used for minimal private domestic supplies through dug wells and shallow boreholes.

- The second and third aquifers are in the Coastal Plains Sands Formation. They are exploited through hand-dug shallow wells in some areas, shallow – and profound – boreholes. These aquifers provide considerable amounts of water for water supplies. This is the principal aquifer exploited, particularly in Lagos and its environs.

- The fourth aquifer is the deep and highly productive Abeokuta formation, which was discussed in previous sections.

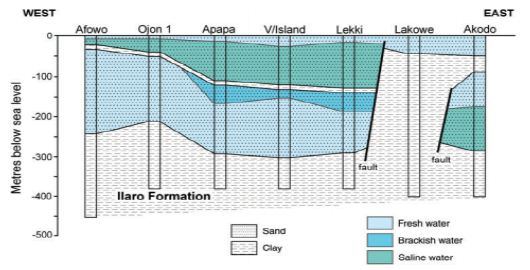

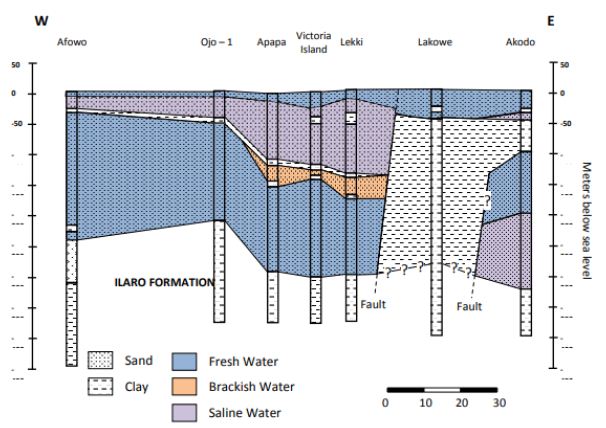

A few boreholes located mostly in Ikeja industrial area in Lagos only extract water from the fourth aquifer. The water from this aquifer is hot with temperatures as high as 80°C recorded in a few boreholes. This aquifer is undergoing massive development in adjoining Ogun State when encountered at shallower depths of between 300 and 550 meters. Figure 12 is a north-south geologic cross-section showing various Formations in the sedimentary basin. In Figure 12, a hydrogeologic cross-section from west to east along the coast shows both the lithologic and water-quality variations in the Coastal Plains Sands and Recent Sediments [56].

Figure 12: Hydrogeological cross-section of coastal basins along with Lagos State. After Oteri and Ayeni [56].

The delineation of shallow aquifers in the coastal plain sands of Okitipupa Area, Southwestern Nigeria, revealed two central aquifer units within the Okitipupa Area, Southwestern Nigeria [56]:

- The upper/surficial aquifer system, which occurs at depths ranging from 5.8 m (around Agbabu) to 61.5 m (around Ikoya), and with materials of higher average resistivity (504.7 Ωm), suggestive of gravelly/coarse to medium-grained sand; and

- The intermediate aquifer system, characterized by depth range of 32.1-127.5 m, average resistivity of 296.8 Ωm, typical of medium-grained sand saturated with water.

The highly resistive, impermeable materials overlying the aquifer units around Ajagba, Aiyesan, Agbetu, Ilutitun, Igbotako, and Erinj suggests that the aquifer units are less vulnerable to near-surface contaminants than in Agbabu, Igbisin, Ugbo, and Aboto where less resistive materials overlie aquifers. However, this indicates that the aquifer cannot be recharged in these areas. The geoelectric sequence suggests subsurface geology characterized by the alternation of sands/gravel, clay/shale, and sandstone occurring at varying depths with variable thicknesses. The sand and gravel layers constitute the aquifer units [56]. The aquifer units’ geoelectric parameters were determined by interpreting the sounding curves, assisted by the distinctive resistivity contrasts between the discrete geoelectric layers.

The upper and lower aquifer horizons work are referred to as the surficial (upper) and intermediate (lower) aquifers. In a different study by Adepelumi, Ako [68], which delineates saltwater intrusion into the freshwater aquifer of Lekki Peninsula, Lagos, Nigeria, the study delineates four distinct resistivity zones viz:

- The unconsolidated dry sand having resistivity values ranging between 125 and 1,028 Xm represents the first layer;

- The fresh water-saturated soil having resistivity values which correspond to 32–256 Xm is the second layer;

- The third layer is interpreted as the mixing (transition) zone of fresh with brackish groundwater. The resistivity of this layer ranges from 4 to 32 Xm; and

- Layer four is characterized by resistivities values generally below 4 Xm reflecting an aquifer possibly containing brine. The rock matrix, salinity, and water saturation are the major factors controlling the Formation’s resistivity. Furthermore, this study illustrates that saline water intrusion into the aquifers can be accurately mapped using the surface DC resistivity method.

The Crystalline Basement Terrain

The Basement Complex terrains of South-western Nigeria are underlain by Precambrian basement rocks, which comprise crystalline igneous and metamorphic rocks mostly granite/porphyritic granite, granite-gneiss, quartz-schist, migmatite as well as Augen-gneiss, Pegmatite intrusions and variably Migmatized Biotite-hornblende Gneiss [28,69,70]. Descriptions on the field and petrographic/mineralogical characteristics of the different rock types are subject to various works. Textural and compositional attributes are wide-ranging. Directional fabrics such as foliation, lineation, and lamination are often developed in the Gneisses, Schists, Quartzites, and Tectonized rocks [71]. From the hydrogeologic perspective, unweathered basement rock contains negligible groundwater; however, the significant aquiferous unit can develop within the weathered overburden and fractured bedrock. It is this weathered and fractured zone, which forms potential groundwater zones. However, several factors that usually contribute to the weathering and development of fracture systems in the basement rocks can be summarized as follows [71]: (i) Presence and stress components of fractures; as conduit zones, hydro-geomorphological conditions that dictate the influence of weathering agents; (ii) Hydro-climatic/temperature regimes that dictate chemical weathering pace; and (iii) Mineral contents of the rock which affect the degree of weathering/overburden thickness.

The availability of groundwater in Pre Cambrian-Basement of southwestern Nigeria depends not only on the geology but also on the complex interactions of the various hydroclimatic and geomorphologic factors [72,73]. Accordingly, several methods have been established to locate favourable sites for groundwater resources extraction within basement rocks. These include remote sensing geophysical methods and geomorphological studies [71]. Assessment of previous studies on groundwater in the crystalline basement terrain of southwestern Nigeria discovered that the hydrogeological setting of the terrain is characterized by weathered saprolite units with varied thickness over the different bedrock units, Porphyritic Granites, Granite-gneiss, Migmatite, Pegmatite, and Quartz-schist settings. Such a setting suggests the influence of rock types and mineralogy on the extent of fracturing and weathering. Consequently, groundwater occurrences in the study area are in localized, disconnected phreatic regolith aquifers, practically under unconfined to semi-confined conditions. Nonetheless, groundwater in the study area can be categorized under two central units: area with highly weathered and fractured bedrock units and poorly weathered/sparsely fractured bedrock units [71]. In an area with deeply weathered regolith and highly fractured zones, groundwater occurrences usually depend on the thickness of the water-bearing rock; this rock can be gravelly and fractured with possible quartz veins within the deep weathered zone of between 10 m to 30 m. These are characteristic of areas underlain in the study area by weathered crystalline and metamorphic rocks such as schist/quartz-schist, fractured granite-gneiss, and porphyritic granites as well as Augen gneiss with vertical fracture zones. These are generally characterized by moderate to high yield of about 75 m3/day and up to >150 m3/day. The borehole depth usually varies from 20 to 60 m, while the saturated thickness varies from 20 to 35 m below the ground surface [71]. In areas where the weathered zone is thin or absent, groundwater is usually tricky due to widely spaced fractures and the weathered zone’s localized zone/pockets. In the study area, these are characteristic of areas underlain by crystalline and metamorphic rocks, especially migmatite and variably Migmatized gneiss characterized by thin/shallow overburden unit of usually less than 10 meters in thickness and low yield of generally less than 75 m3/day. In such a setting also, the borehole depth varies from 20 to 30 m while saturated thickness varies from 8 to 20 m below the ground surface [71]. Nonetheless, towards the base of the weathered zone at the interface with the fresh bedrock, the permeability is usually high, allowing water to move freely due to the low proportion of clayey materials. However, deep-seated fractures are vital in such situations and can sometimes provide appreciable water supplies, mainly when tectonically controlled. Wells or boreholes that penetrate this horizon can usually provide sufficient water to sustain even hand-dug wells. Due to the complex interactions of the various factors affecting weathering in a typical basement complex setting like the study area, the groundwater potential zone distribution can be erratic and may not be present in some locations [71]. The analysis that involved characterization of weathered overburden revealed estimated overburden thickness using geoelectrical VES surveys from 3.8 to 50 meters with a mean value of about 20 meters as dictated by bedrock types. These values are within the range of values obtained for similar Basement Complex terrains of Africa. Furthermore, it was observed that areas with thin/shallow overburden coincided mostly with areas underlain by variably Migmatized gneiss complex, while the area with thicker overburden unit coincided with area mainly underlain by schist. However, the quartzite/quartz-schist setting coincided with areas of moderate to shallow overburden thickness [71]. In a nutshell, the varied thickness and the weathered overburden units’ isolated pockets also confirm the localized nature of weathered basement aquifers under the crystalline basement setting. The implication of this lies in the fact that there is the need for careful characterization and delineation of areas of possible fracturing and deep weathering as an aquiferous zone in respect of groundwater developments in Basement Complex settings of the study area. Therefore, the present study addresses the aspect of characterization of the groundwater potential using integrated GIS, RS, and MCDA techniques in conjunction with conventional hydrological and hydrogeological data [71]. Although the hydrogeology of southwestern Nigeria’s coastal basins is well described in the literature, a comprehensive description of its hydrochemistry has been lacking. The following section presents a synthesis of physicochemical physiognomies of groundwater in the basin.

Groundwater Chemistry

Physical Chemistry

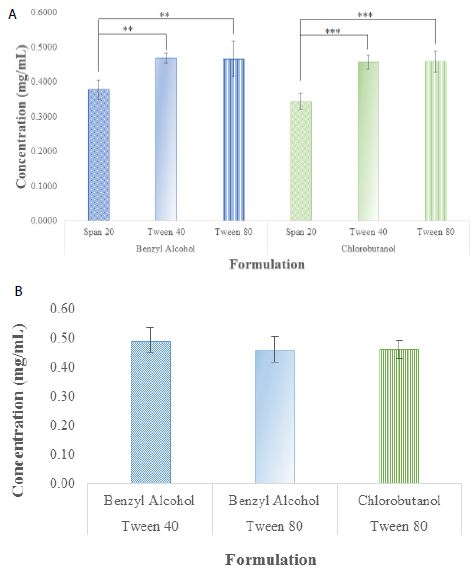

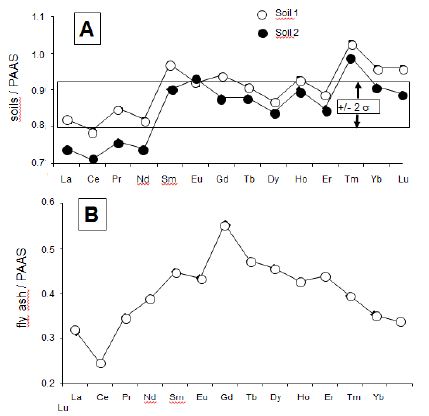

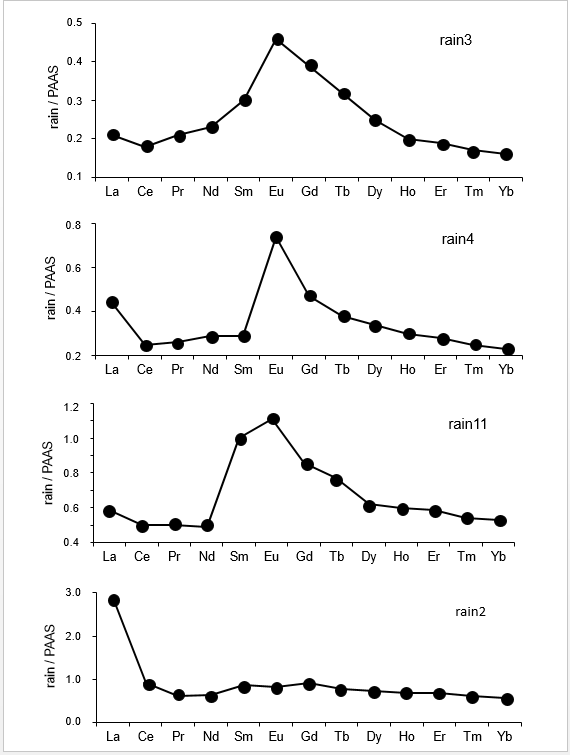

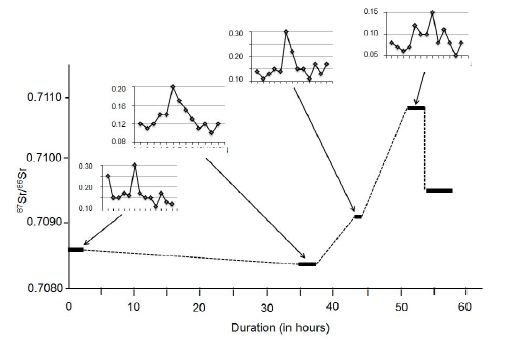

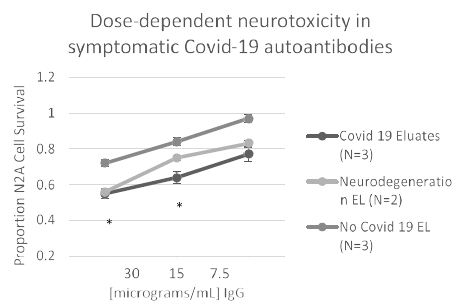

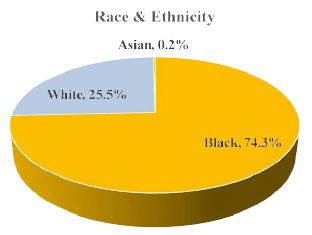

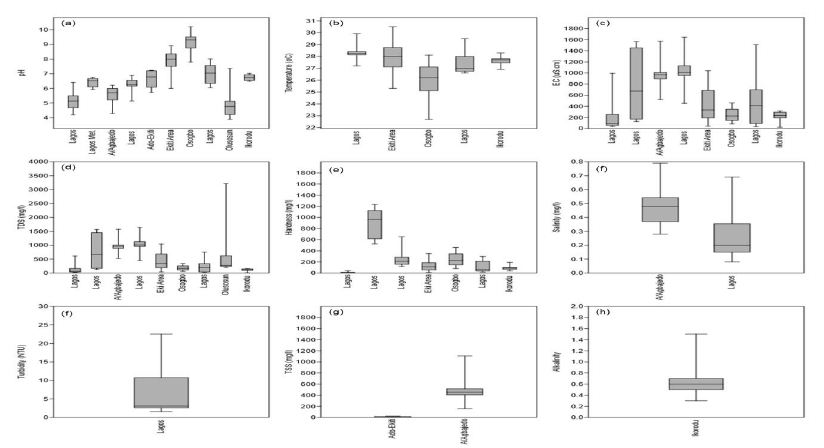

Figures 13-15 present a summary of groundwater’s physical and chemical parameters in southwestern Nigeria’s coastal basins. Evaluation of pH concentration from 210 locations showed that pH ranged from 3.9 to 10.2 with a mean pH value of 7.4. Generally drinking water having pH < 7 is measured as acidic, and pH > 7 is considered basic. The normal range for pH in surface water systems is 6.5 to 8.5 and for groundwater aquifers 6 to 8.5 [74-76]. Unlike the Niger Delta Basin, groundwater in coastal basins of southwestern Nigeria is slightly alkaline. Alkalinity is a degree of the water’s capacity to resists a change in pH that would tend to make the water more acidic. The measurement of alkalinity and pH is needed to determine the water’s corrosivity [77-80]. The pH of clean water is 7 at 25°C, but when exposed to the atmosphere’s carbon dioxide, this equilibrium results in a pH of approximately 5.2. Because of the association of pH with atmospheric gasses and temperature, it is strongly recommended that the water is tested as soon as possible. The water’s pH is not a measure of the acidic or basic solution’s strength and alone does not provide a full picture of the characteristics or limitations with the water supply. In general, groundwater sources with low pH (< 6.5) could be acidic, soft, and corrosive. Therefore, the water could leach metal ions such as iron, manganese, copper, lead, zinc from the aquifer, plumbing fixtures, and piping. Consequently, groundwater with low pH could contain elevated levels of toxic metals, cause premature damage to metal piping, and have associated aesthetic problems such as a metallic or sour taste, laundry staining, and the characteristic blue-green staining of sinks and drains [81-83].

Groundwater sources having pH > 8.5 could indicate that the water is hard [84-86]. Hard water does not pose a health risk but can cause aesthetic problems. These problems include:

- Formation of a ‘scale’ or precipitate on piping and fixtures causing water pressures and the interior diameter of piping to decrease;

- Causes an alkali taste to the water and can make coffee taste bitter;

- Formation of a scale or deposit on dishes, utensils, and laundry basins;

- Difficulty in getting soaps and detergents to foam and Formation of insoluble precipitates on clothing, etc.; and Decreases efficiency of electric water heaters.

The temperature ranged from 22.7 to 30.5°C, with a mean value of 27.5°C. The causes for the temperature rise in aquifers are numerous, and these are directly linked to the continuing structural developments and the existing uses at the earth’s surface. These influences can be direct or indirect. The direct influences on the groundwater temperature include all heat inputs to the groundwater through the sewage network, district-heat pipes, power lines, and sources connected with groundwater heat use and storage [87-89]. The indirect influences on groundwater temperature processes are linked with urbanization-related changes in the heat balance in the near-surface atmosphere. The most important factors are:

- The disturbance of the water balance due to a high degree of surface imperviousness;

- The change of soil characteristics caused by an aggregation of structures (differences in the near-surface heat input and heat capacity);

- Changes in the irradiance balance by changes in the atmospheric composition; and

- Anthropogenic heat generation (domestic heating, industry, and transport).

The differences mentioned above cause changes in the heat balance by comparison with the areas surrounding the city. The city heats itself slowly, stores more heat overall, and passes it on again slowly to the surrounding areas, i.e., it can generally be considered an enormous heat storage unit [90,91]. Over the long term, this process increases the annual mean air and soil temperatures. The long-term warming of the near-surface soil also leads to a heating of the groundwater. Since the temperature affects the physical qualities and the groundwater’s chemical and biological nature, deterioration of groundwater quality and an impairment of the groundwater fauna may result from high temperatures [92-94]. The concentration of EC was synthesized from 177 locations from the basins. Conductivity values ranged from 31.9 to 1643 µS/cm with a mean value of 526.47 µS/cm. Electrical conductivity is widely used for monitoring the mixing of fresh and saline water, for separating stream hydrographs, and for geophysical mapping of contaminated groundwater [95,96]. Distilled water should typically have an EC of less than 0.3 µS/cm. For groundwater, EC values greater than 500 µS cm-1 indicate that the water may be polluted, although values as high as 2000 µS/cm may be acceptable for irrigation water [97,98]. In Europe, the EC of drinking water should be no more than 2500 µS/cm; water with a higher TDS may have water quality problems and be unpleasant to drink [99-101]. Synthesis of hardness from 211 locations revealed that hardness ranged from 11 to 3215 mg/l with a mean value of 467.05 mg/l. Initially, water hardness was understood to be the capacity of water to precipitate soap. Hard water does not allow soap to form as many suds. Water high in hardness is detrimental to plumbing and will reduce the life of water heaters. Water softeners will typically reduce hardness to below 10 mg/l. However, they replace the calcium and magnesium metals with sodium which is undesirable for low salt intake diets [102-104]. Water softener companies often discuss hardness in ‘Grains per Gallon’ instead of the standard units mg/l. To convert hardness from mg/L to grains per gallon, multiply mg/l by 17. Thus, 525 mg/l is equal to 31 gram/gallon. Salinity ranged from 0.08 to 1109 mg/l with a mean value of 178.90 mg/l. There is a substantial reporting on salinity in coastal basins of southwestern Nigeria. All-natural water holds some salt level, and in groundwater, the concentration can naturally vary from fresh to saltier-than-seawater. While small amounts of salt are vital for life, high levels can limit groundwater use and affect ecosystems that depend on groundwater. Small quantities of salt are deposited on the landscape every time it rains. Evaporation and plant transpiration remove water from the landscape but leave the salt behind. It concentrates salt over time. Evaporation can also directly increase groundwater salinity in areas where groundwater is close to the surface. Old groundwater can also become saltier as it passes through aquifers and picks up salts from dissolved minerals.

Although salt in the southwestern Nigeria landscape’s coastal aquifers is natural, groundwater and salt movement’s salinity into groundwater-dependent ecosystems can be increased by human activities. Increases in groundwater salinity can be caused by:

- Increased groundwater recharge because of irrigation, which mobilizes salts naturally accumulated in the soil (irrigation salinity);

- Increased groundwater recharge because of land clearing, bringing groundwater near the land surface, causing evaporation from the soil surface and salt accumulation (dryland salinity);

- Leaking pipes, over-watering of gardens, and runoff from compacted surfaces can raise groundwater levels and concentrate salts in urban areas, which can lead to salt damage on buildings and roads (urban salinity);

- Over-pumping near the coast, which can cause seawater to seep into replenishing water levels.

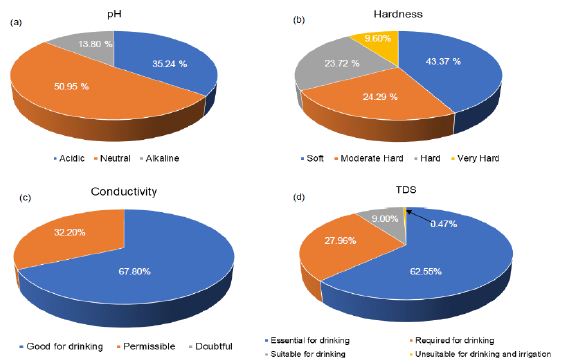

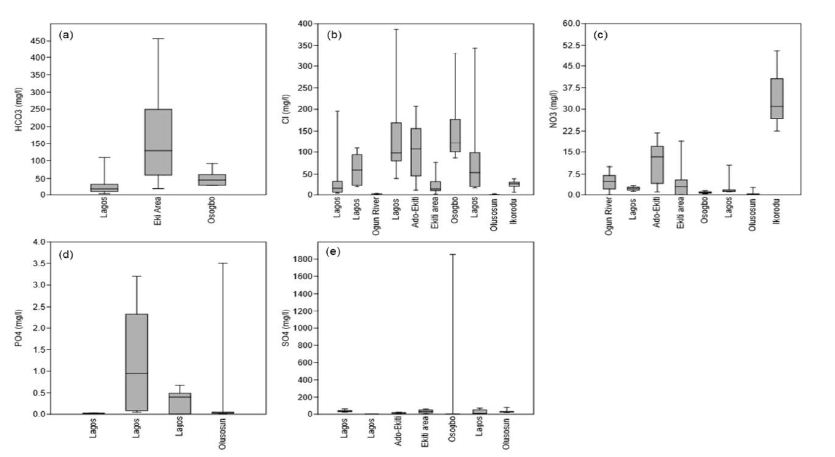

Groundwater salinity can also be reduced at times, such as when rapid recharge from flooding flushes out or dilutes salty groundwater. Broadscale changes in groundwater salinity occur very slowly, over decades or longer. Therefore, groundwater salinity is usually monitored rarely except where human impacts are of concern. Measurements on Turbidity, TSS, and Alkalinity were not much in the coastal basins of southwestern Nigeria. Turbidity ranged from 0.86 to 26.34 mg/l, with a mean value of 8.06 mg/l. This estimate was based on two studies (Figure 13f). Therefore, more reporting on turbidity is required in the basin. There is currently little information regarding turbidity in groundwater, and the cause is not fully understood. The common assumption is that groundwater turbidity indicates a fast transport pathway connecting potentially contaminated surface water with the aquifer. Studies found no relationship between turbidity and microbiology, although Chalk sources appear more susceptible to E. coli than other aquifers [105]. The occurrence of turbidity tends to be site-specific with a variety of causes. Mitigation measures in groundwater might include variable speed pumps, automatic pumping to waste, blending, or engineered solutions. Discussion on TSS was based on one study (Figure 13g). Total suspended solids ranged from 153 to 1109 mg/l with a mean value of 472.67 mg/l. Total Suspended Solids (TSS), also known as non-filterable residue, are those solids (minerals and organic material) that remain trapped on a 1.2 µm filter. Suspended solids can enter groundwater through runoff from industrial, urban, or agricultural areas [106]. Elevated TSS can reduce water clarity, degrade habitats, clog fish gills, decrease photosynthetic activity, and cause an increase in water temperature. TSS has no drinking water standard; drinking water with high TSS concentration can increase people’s severity with liver diseases. Similarly, there is not much reporting on alkalinity from these basins. Alkalinity ranged from 0.3 to 1.5 mg/l, with a mean concentration of 0.67 mg/l (Figure 13h). Alkalinity is not a chemical in water, but, instead, it is a property of water-dependent on the presence of certain chemicals in the water, such as bicarbonates, carbonates, and hydroxides. Groundwater aquifers with high alkalinity will experience less of a change in its acidity, such as acidic water, such as acid rain or an acid spill, introduced into the water body [107-109]. In a surface water body, such as a lake, the water’s alkalinity comes mostly from the lake’s rocks and land. Precipitation falls in the lake’s watershed, and most of the water entering the lake comes from runoff over the landscape. If the landscape is in an area containing rocks such as limestone, then the runoff picks up chemicals such as calcium carbonate (CaCO3), which raises the water’s pH and alkalinity. In areas where the geology contains large amounts of granite, lakes will have lower alkalinity. A pond in a suburban area, even in a granite-heavy area, as in some parts on the coastal basins (e.g., Lagos and its environs), could have high alkalinity due to runoff from home lawns where limestone has been applied. However, studies are required for further evaluation. Studies on dissolved oxygen from coastal basins of southwestern Nigeria are quite small in number. Ayolabi, Folorunso [110]’s integrated geophysical and geochemical methods for environmental assessment of the municipal dumpsite system in Lagos revealed DO ranging between 4 to 4.4 mg/l with a mean value of 4.1 mg/l. Similarly, Awomeso, Taiwo [111]’s study on the pollution of a waterbody by textile industry effluents in Lagos, Nigeria showed that COD concentration varies with distance from the discharge point. The concentration of was 890 mg/l at 0 meters, 600 mg/l at 50 meters, 214 mg/l at 100 meters, 1703 at 150 meters, 1172 ta 200 meters, 10 mg/l at 250 meters, 1693 mg/l at 300 meters, 860 mg/l at 350 meters, 1901 mg/l at 400 meters and 10 mg/l at 450 meters respectively. Omale and Longe [112]’s, assessment of the impact of abattoir effluents on River Illo, Ota, Nigeria showed that BOD ranged from 140 to 670 mg/l with a mean value of 333.33 mg/l. Most of the studies reporting BOD came from surface water bodies. Groundwater is yet to be fully explored in southwestern Nigeria’s coastal basins, based on these parameters. Dissolved oxygen significantly affects groundwater quality by regulating the valence state of trace metals and constraining dissolved organic species’ bacterial metabolism [113-115]. Consequently, the measurement of dissolved oxygen concentration should be considered vital in most water quality researches. Measurements of dissolved oxygen have been often ignored in groundwater monitoring. Oxygen has regularly been assumed absent below the water table; O2 measurements are not mandated by drinking water standards. Regular organic debris and organic waste derived from wastewater treatment plants, failing septic systems, and agricultural and urban runoff act as food sources for water-borne bacteria. Bacteria decompose these organic constituents using DO, consequently reducing the DO present for aquatic organisms. Chemical oxygen demand does not discriminate between biologically available and inert organic matter, and it is a measure of the total quantity of oxygen required to oxidize all organic material into carbon dioxide and water [116-119]. The COD values are always greater than BOD values, but COD measurements can be made in a few hours while BOD measurements take five days. Since parameters play a significant role in groundwater quality, it is recommended that such parameters are measured throughout the coastal basin of southwestern Nigeria. Figure 14 presents the groundwater classification based on pH, Hardness, Conductivity, and TDS. Based on pH 50.95% of groundwater sources in coastal basins of southwestern Nigeria fall in neutral class, 35.24% fall in acidic class, and 13.80% fall in alkaline class. Conversely, total hardness is also varying in the basin. About 43.37% of groundwater sources fall in soft class, 24.29% fall in intermediate class, 23.72% fall in hard class, and 9.60% fall in the very hard-water class. About 67.80% of groundwater sources have conductivity below 750 µS/cm, and 32.24% have EC values between 750 to 2250 µS/cm. Low TDS levels further show the low conductivity of groundwater sources in the basin. About 62.55% groundwater sources have TDS below 500 mg/l, 27.96% have TDS concentration between 500 to 1000 mg/l, 9.00% have TDS level between 1000 to 3000 mg/l and 0.47% have TDS above 3000 mg/l. This variability is further illustrated in Figure 14d.

Figure 13: Hydrogeological cross-section of coastal basins along with Lagos State.

Figure 14: Groundwater classification (a) pH, (b) Total hardness, (c) Conductivity and (d) TDS.

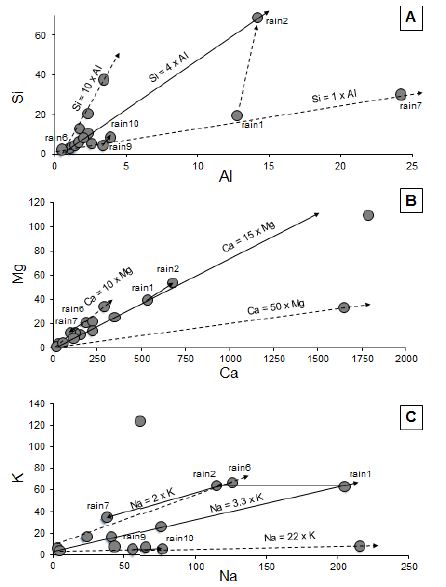

Cation Chemistry

Understanding the chemical physiognomies of groundwater is essential as a result of their contrasting sources. As soon as their concentration is above the suggested reference guidelines, these prerequisites may render groundwater unusable. Chemical essentials including Ca, Mg, Cu, Cd, B, Al, K, PO4, SO4 As, and Cl, for instance, are primarily derived from rocks. Nonetheless, elements like NO3 and SO4 are derived mainly from anthropogenic sources [118,119]. Understanding the derivation and absorption level of these chemical elements in groundwater is needed for effective groundwater management. Generally, there is little reporting on Al, NH4, and southwestern Nigeria’s coastal basins. For instance, Ayolabi, Folorunso [110]’s analysis of the municipal dumpsite system in Lagos showed Al ranged from 0.001 to 1.641 mg/l with a mean value of 0.29 mg/l.

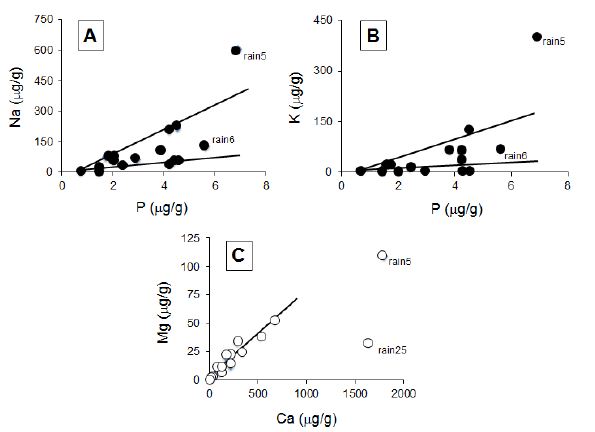

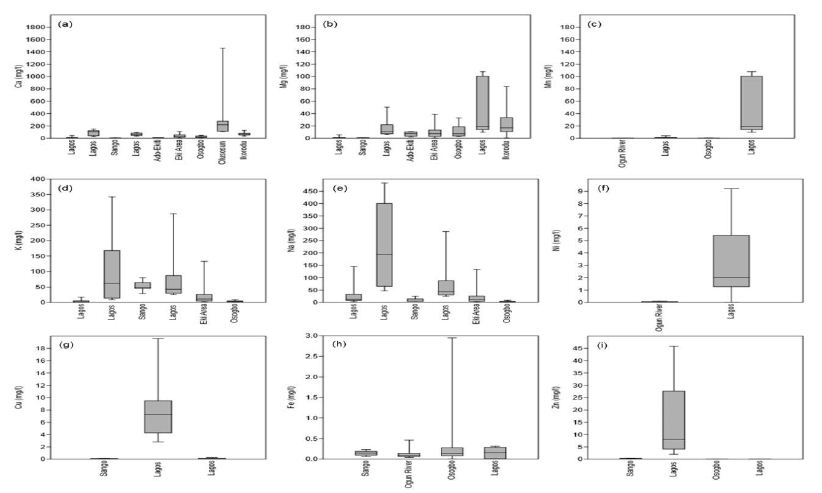

Longe and Enekwechi [120] investigated potential groundwater impacts, and the influence of local hydrogeology on natural attenuation of leachate at a municipal landfill from Olusosun landfill showed that NH4 ranged from 0.14 to 1.5 mg/l with an average value of 0.41 mg/l. A review of the level of arsenic in potable water sources in Nigeria and their potential health impacts by Izah and Srivastav [121]’s analysis showed that arsenic concentration in western Nigeria ranged from 0.00 to 0.38 mg/l at Ibadan, 0.00 to 0.05 mg/l in Odeda region, 0.03 to 0.47 mg/l at Ijebu land and 0.01 to 0.70 mg/l at Igun-ijesha. People are exposed to elevated levels of inorganic arsenic through drinking contaminated water, using contaminated water in food preparation and irrigation of food crops, industrial processes, eating contaminated food and smoking tobacco. Long-term exposure to inorganic arsenic, mainly through drinking water and food, can lead to chronic arsenic poisoning. Skin lesions and skin cancer are the most characteristic effects. The SON has recommended 0.2 mg/l as a maximum permissible limit in drinking water. Aluminium is an excellent metal in the earth’s crust and is regularly found in the form of silicates such as feldspar. The oxide of Al known as bauxite provides a suitable source of uncontaminated ore. Aluminium can be selectively leached from rock and soil to enter groundwater aquifer. Aluminium is known to exist in groundwater in concentrations ranging from 0.1 ppm to 8.0 ppm. Al can be present as Aluminum Hydroxide, a residual from the municipal feeding of aluminium (Aluminum Sulfate), or as Sodium Aluminate from clarification or precipitation softening. It has been known to cause deposits in cooling systems and contributes to the boiler scale. Aluminium may precipitate at normal drinking water pH levels and accumulate as a white gelatinous deposit. Aluminium is controlled in drinking water with a recommended Secondary Maximum Contaminant Level (SMCL). SMCL’s are used when the taste, odour, or appearance of water may be adversely affected. In this case, the WHO [122] established that an Al concentration above 0.1–0.2 mg/l might impact colour but recognize that level may not be appropriate for all water supplies. The Nigerian Standard for Drinking Water Quality (NSDWQ) has recommended 0.2 mg/l as a maximum permissible limit because of potential neuro-degenerative disorders associated with high Al concentrations in water. The natural levels of NH4 in groundwater and surface water are usually below 0.2 mg/litre. Anaerobic groundwaters may contain up to 3 mg/l. Leached effluents from the concentrated rearing of farm animals can give rise to much higher levels in groundwater. Ammonia pollution can also rise from cement mortar pipe linings. Ammonia is an indicator of possible bacterial, sewage, and animal waste effluence. Contact from environmental sources is insignificant in comparison with the endogenous synthesis of NH4. Toxicological effects are observed only at exposures above about 200 mg/kg of body weight. Ammonia in drinking water is not of immediate health significance, and consequently, no health-based guideline value is proposed by SON. There are few studies on Barium concentration in groundwater from coastal basins of southwestern Nigeria. Odukoya and Abimbola [123]’s assessment of contamination of surface and groundwater within and around two dumpsites in Lagos revealed that Ba concentrations ranged from 40 to 100 mg/l with a mean value of 49 mg/l within and around abandoned dumpsite. Barium also ranged from <0.001 to 80 mg/l with a mean value of 56 mg/l within and around active dumpsite. Barium is available as a trace element in both igneous and sedimentary rocks. Even though it is not found free, it occurs in several compounds, most commonly barium sulfate (or barite) and, to a lesser extent, barium carbonate (or witherite). Barium goes into the environment naturally via the weathering of rocks and minerals. Anthropogenic releases are primarily connected with industrial processes. The over-all population is exposed to Ba through the ingestion of drinking water and foods, usually at low levels. Figure 15a presents a synthesis of Ca from groundwater from coastal basins of southwestern Nigeria. Calcium ranged from 1.49 to 1460 mg/l with a mean value of 56.78 mg/l. Calcium in drinking water is beneficial, but it is important to note that calcium is a significant constituent of hardness. Based on SON guidelines, Ca is not limited to drinking water. Based on the results of the WHO meeting of experts held in Rome, Italy, in 2003 to discuss nutrients in drinking water [124], the assembly focused its attention on Ca and Mg, for which, next to F, a sign of health benefits accompanied by their existence in drinking water is robust. The Ca’s insufficient consumption has been accompanied by increased risks of osteoporosis, nephrolithiasis (kidney stones), colorectal cancer, hypertension and stroke, coronary artery disease, insulin resistance, and obesity. Most of these disorders have treatments but no cures. Due to a lack of convincing evidence for Ca’s role as a single influential element about these diseases, estimates of the Ca requirement have been made based on bone health outcomes to improve bone mineral density. Calcium is exclusive among nutrients because the body’s reserve is also functional: increasing bone mass is correlated to a decrease in fracture risk. There relatively high Ca level in these basins could be beneficial to the health of the people living there. Figure 15b presents a synthesis of Mg from groundwater in coastal basins of southwestern Nigeria. Evaluation of Mg from 183 sites across these basins showed that Ca ranged from 0 to 108 mg/l with a mean value of 12.26 mg/l. Based on the NSDWQ [125] reference guidelines, 0.2 mg/l was suggested as the maximum permissible Mg concentration in drinking water. The relatively high Ca and Mg recorded in these basins have resulted in the hard water as 56.63% of groundwater in these basins is either moderately hard, hard, or very hard. Numerous epidemiologic researches carried out during recent years have established an inverse relationship between water hardness and death from cardiovascular disease. Many recommendations leave been offered concerning, the causal agent for the association between death from cardiovascular disease and water hardness. Two standards have been debated: a toxic effect brought by the contamination of lead or cadmium or a shielding effect from Ca or Mg’s water content. What is vital is to limit the concentrations of these elements in drinking water. Figure 15c presents a synthesis of Mn from groundwater across the coastal basins of southwestern Nigeria. Manganese ranged from <0.001 to 108 mg/l with a mean concentration of 10.05 mg/l. The SON has recommended 0.2 mg/l Mn as the maximum permissible limit in drinking water due to the neurological disorder associated with water ingestions having a high Mn level [125]. Manganese has recently come under inspection in drinking water due to its possible toxicity and its impairment to water distribution networks. Manganese is rarely found alone in groundwater. It is often found in iron-bearing waters but is rarer than iron. Chemically it can be measured as a close relative of iron since it occurs in much the same iron forms. When manganese is available in groundwater, it is as annoying as iron, perhaps even more. At low concentrations, it produces incredibly objectionable stains on everything with which it comes in contact. Evaluation of K from 207 sites (Figure 15d), in the coastal basin of southwestern Nigeria, showed that K ranged from <0.001 to 341.7 mg/l with a mean value of 24.77 mg/l. Potassium is an essential electrolyte, which is a mineral required by the body to function correctly. Potassium is especially vital for nerves and muscles, including the heart. While K is central to human health, too much ingestion of K can be just as harmful as, or worse than, not getting enough. Usually, kidneys keep a healthy balance of K by flushing excess potassium out of the body. However, for many reasons, the level of potassium in the blood can be too high. This is called Hyperkalemia, or high potassium. The NSDWQ [125], issued no guidelines on K levels in drinking water. Figure 15e presents a synthesis of Na from groundwater across the coastal basins of southwestern Nigeria. Sodium concentration from 152 sites showed that Na ranged from <90.001 to 483.42 mg/l with a mean value of 38.02 mg/l. There is an increasing call to use K in combination with Na to treat and soften drinking water. However, this would cause the level of K in drinking water to increase. The WHO found that the level of K found in drinking water would present no health concerns for healthy adults; though, for specific populations with comprised renal functions, such as infants or individuals suffering from specific diseases, there is the likelihood of adverse health effects. Sodium is not measured to be toxic. The human body requires Na to maintain blood pressure, control fluid levels, and normal nerve and muscle function. However, there are no health-based criteria for Na in drinking water. Only a small amount of the Na we ingest practically comes from water. As a substitute, the standard for Na is based on taste. The mean Na concentration in these basins is below [125] recommended value (200 mg/l).

Quality assessment of groundwater in the vicinity of dumpsites in Ifo and Lagos, Southwestern Nigeria by Majolagbe, Kasali [126], showed that Cd concentration was below the detection limit at Ifo, whereas, mean Cd concentration was 0.005 in Lagos. In the same vein, groundwater quality assessment in a typical rural settlement (Igbora, Oyo state,) in southwest Nigeria by Adekunle, Adetunji [127], showed Cd concentration varies with distance from dumpsites. The Mean Cd concentration was 0.78 mg/l at 50 meters, 0.30 mg/l at 100 meters, 0.32 mg/l at 150 meters, and 0.30 mg/l at 200 meters away from during the dry season. Cadmium concentration was 0.34 mg/l at 50 meters, 0.32 mg/l at 100 meters, 0.30 mg/l at 150 mg/l and 0.24 mg/l at 200 meters away from dumpsite during wet season. Ayolabi, Folorunso [110]’s assessment of the municipal dumpsite system in Lagos indicated that Cd ranged from <0.001 to 0.025 mg/l. There are many studies on Cd in these basins, but the underline reasons for higher Cd in groundwater need to be understood. Many studies have been carried out to decode relationships between geological environment, potable/drinking water, and diseases as they were considered to have caused suffering due to diseases among people. Chronic anaemia can be caused by protracted exposure to drink water polluted with Cd. The Cd’s accumulation is established in the kidney under such conditions, resulting in cancer and cardiovascular diseases. The NSDWQ [125] has limit Cd concentration in drinking water to be 0.003 mg/l. Cadmium is restrained in drinking water because of its toxic effects on the kidney. Assessment of groundwater fluoride and dental fluorosis in Southwestern Nigeria by Gbadebo [128], revealed that groundwater samples from Abeokuta Metropolis (i.e., basement complex terrain) had F concentrations in the range of 0.65 to 1.20 mg/l. These values were lower than the F contents in the groundwater samples from Ewekoro peri-urban and Lagos metropolis where the values ranged between 1.10 to 1.45 and 0.15 and 2.20 mg/l, respectively. The F concentrations in nearly all locations were generally above the WHO recommended 0.6 mg/l. The study also revealed that the F distribution of groundwater samples from the different geological terrain was more dependent on pH and TDS than on temperature. The result of the analyzed social-demographic characteristics of the residents indicated that the adults (between the age of 20 and >40 years) showed dental decay than the adolescent (<20 years). This indicates an incidence of dental fluorosis by the high fluoride content in the populace’s drinking water. Conversely, evaluation of groundwater contamination in Ibadan, South-West Nigeria by Egbinola and Amanambu [129], revealed that F concentration is above the recommended limits in 13% and 100% the dry and wet season samples. The occurrence of F in groundwater has become one of the most significant toxicological environmental hazards worldwide. Fluoride in groundwater is due to the weathering and leaching of fluoride-bearing minerals from rocks and sediments. When consumed in small quantities (<0.5 mg/l), F is advantageous in promoting dental health by reducing dental caries, but higher concentrations (>1.5 mg/l) may cause fluorosis [130]. It is projected that about 200 million people, from among 25 nations the world over, may suffer from fluorosis and the causes have been attributed to fluoride pollution in groundwater including Nigeria. High F concentration in groundwater is expected from sodium bicarbonate-type water, which is calcium deficient. The alkalinity of water also mobilises fluoride from fluorite (CaF2) [131-133]. Exposure to F in humans is related to:

i. Fluoride concentration in drinking water

ii. Duration of consumption; and

iii. The climate of the area. In hotter climates where water consumption is more significant, exposure doses of fluoride (F) need to be modified based on mean F intake.