DOI: 10.31038/ESCC.2020212

Abstract

This study ties increasing climate feedbacks to projected warming consistent with temperatures when Earth last had this much CO2 in the air. The relationship between CO2 and temperature in a Vostok ice core is used to extrapolate temperature effects of today’s CO2 levels. The results suggest long-run equilibrium global surface temperatures (GSTs) 5.1°C warmer than immediately “pre-industrial” (1880). The relationship derived holds well for warmer conditions 4 and 14 million years ago (Mya). Adding CH4 data from Vostok yields 8.5°C warming due to today’s CO2 and CH4 levels. Long-run climate sensitivity to doubled CO2, given Earth’s current ice state, is estimated to be 8.2°C: 1.8° directly from CO2 and 6.4° from albedo effects. Based on the Vostok equation using CO2 only, holding ∆GST to 2°C requires 318 ppm CO2. This means Earth’s remaining carbon budget for +2°C is estimated to be negative 313 billion tonnes. Meeting this target will require very large-scale CO2 removal. Lagged warming of 4.0°C (or 7.4°C when CH4 is included), starting from today’s 1.1°C ∆GST, comes mostly from albedo changes. Their effects are estimated here for ice, snow, sulfates, and cloud cover. This study estimates magnitudes for sulfates and for future snow changes. Magnitudes for ice, cloud cover, and past snow changes are drawn from the literature. Albedo changes, plus their water vapor multiplier, caused an estimated 39% of observed GST warming over 1975-2016. Estimated warming effects on GST by water vapor; ocean heat; and net natural carbon emissions (from permafrost, etc.), all drawn from the literature, are included in projections alongside ice, snow, sulfates, and clouds. Six scenarios embody these effects. Projected ∆GSTs on land by 2400 range from 2.4 to 9.4°C. Phasing out fossil fuels by 2050 yields 7.1°C. Ending fossil fuel use immediately yields 4.9°C, similar to the 5.1°C inferred from paleoclimate studies for current CO2 levels. Phase-out by 2050 coupled with removing 71% of CO2 emitted to date yields 2.4°C. At the other extreme, postponing peak fossil fuel use to 2035 yields +9.4°C GST, with more warming after 2400.

Introduction

The December 2015 Paris climate pact set a target of limiting global surface temperature (GST) warming to 2°C above “pre-industrial” (1750 or 1880) levels. However, study of past climates indicates that this will not be feasible, unless greenhouse gas (GHG) levels, led by carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4), are reduced dramatically. Already, global air temperature at the land surface (GLST) has warmed 1.6°C since the 1880 start of NASA’s record [1]. (Temperatures in this study are 5-year moving averages from NASA, Goddard Institute for Space Studies, in °C. Baseline is 1880 unless otherwise noted.) The GST has warmed by 2.5°C per century since 2000. Meanwhile, global sea surface temperature (=(GST – 0.29 * GLST)/0.71) has warmed by 0.9°C since 1880 [2].

The paleoclimate record can inform expectations of future warming from current GHG levels. This study examines conditions during ice ages and during the most recent (warmer) epochs when GHG levels were roughly this high, some lower and some higher. It strives to connect future warming derived from paleoclimate records with physical processes, mostly from albedo changes, that produce the indicated GST and GLST values.

The Temperature Record section examines Earth’s temperature record, over eons. Paleoclimate data from a Vostok ice core covering 430,000 years (430 ky) is examined. The relations among changes in GST relative to 1880, hereafter “∆°C”, and CO2 and CH4 levels in this era colder than now are estimated. These relations are quite consistent with the ∆°C to CO2 relation in eras warmer than now, 4 and 14 Mya. Overall climate sensitivity is estimated based on them. Earth’s remaining carbon budget to keep warming below 2°C is calculated next, based on the equations relating ∆°C to CO2 and CH4 levels in the Vostok ice core. That budget is far less than zero. It requires returning to CO2 levels of 60 years ago.

The Feedback Pathways section discusses the major factors that lead from our present GST to the “equilibrium” GST implied by the paleoclimate data, including a case with no further human carbon emissions. This path is governed by lag effects deriving mainly from albedo changes and their feedbacks. Following an overview, eight major factors are examined and modeled to estimate warming quantities and time scales due to each. These are (1) loss of sulfates (SO4) from ending coal use; (2) snow cover loss; (3) loss of northern and southern sea ice; (4) loss of land ice in Antarctica, Greenland and elsewhere; (5) cloud cover changes; (6) water vapor increases due to warming; (7) net emissions from permafrost and other natural carbon reservoirs; and (8) warming of the deep ocean.

Particular attention is paid to the role that anthropogenic and other sulfates have played in modulating the GST increase in the thermometer record. Loss of SO4 and northern sea ice in the daylight season will likely be complete not long after 2050. Losses of snow cover, southern sea ice, land ice grounded below sea level, and permafrost carbon, plus warming the deep oceans, should happen later and/or more slowly. Loss of other polar land ice should happen still more slowly. But changes in cloud cover and atmospheric water vapor can provide immediate feedbacks to warming from any source.

In the Results section, these eight factors, plus anthropogenic CO2 emissions, are modeled in six emission scenarios. The spreadsheet model has decadal resolution with no spatial resolution. It projects CO2 levels, GSTs, and sea level rise (SLR) out to 2400. In all scenarios, GLST passes 2°C before 2040. It has already passed 1.5°. The Discussion section lays out the implications of Earth’s GST paths to 2400, implicit both in the paleoclimate data and in the development of specific feedbacks identified for quantity and time-path estimation. These, combined with a carbon emissions budget to hold GST to 2°C, highlights how crucial CO2 removal (CDR) is. CDR is required to go beyond what emissions reduction alone can achieve. Fifteen CDR methods are enumerated. A short overview of solar radiation management follows. It may be required to supplement ending fossil fuel use and large-scale CDR.

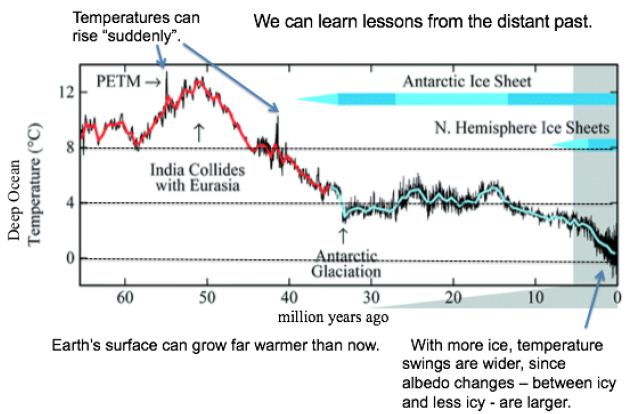

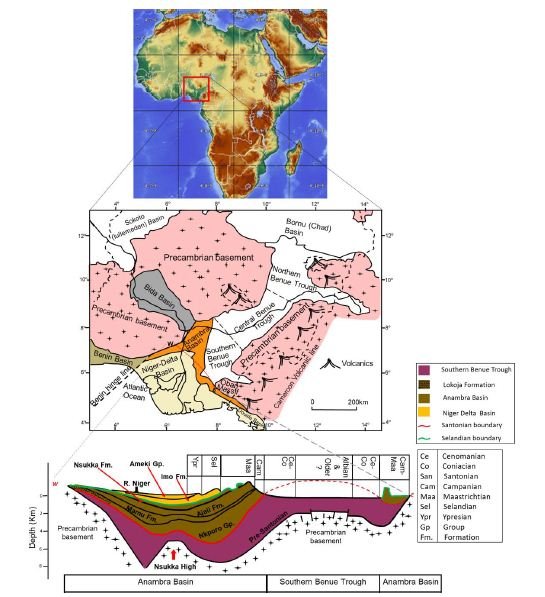

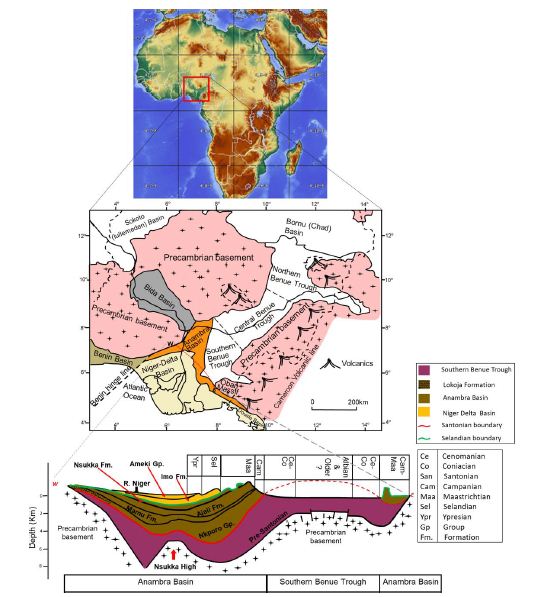

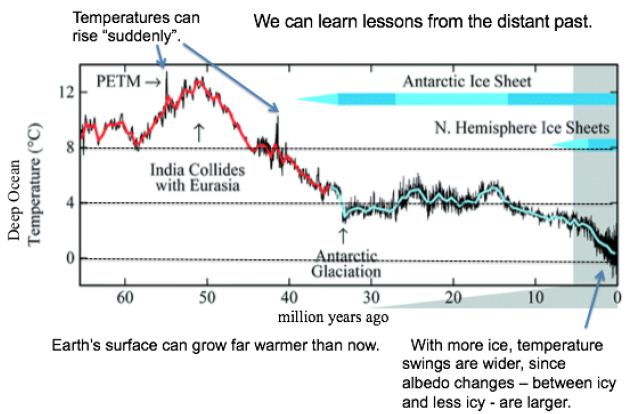

The Temperature Record

In a first approach, temperature records from the past are examined for clues to the future. Like causes (notably CO2 levels) should produce like effects, even when comparing eras hundreds of thousands or millions of years apart. As shown in Figure 1, Earth’s surface can grow far warmer than now, even 13°C warmer, as occurred some 50 Mya. Over the last 2 million years, with more ice, temperature swings are wider, since albedo changes – from more ice to less ice and back – are larger. For GSTs 8°C or warmer than now, ice is rare. Temperature spikes around 55 and 41 Mya show that the current one is not quite unique.

Figure 1: Temperatures and Ice Levels over 65 Million Years [3].

Some 93% of global warming goes to heat Earth’s oceans [4]. They show a strong warming trend. Ocean heat absorption has accelerated, from near zero in 1960: 4 zettaJoules (ZJ) per year from 1967 to 1990, 7 from 1991 to 2005, and 10 from 2010 to 2016 [5]. 10 ZJ corresponds to 100 years of US energy use. The oceans now gain 2/3 as much heat per year as cumulative human energy use or enough to supply US energy use for 100 years [6] or the world’s for 17 years. By 2011, Earth was absorbing 0.25% more energy than it emits, a 300 (±75) million MW heat gain [7]. Hansen deduced in 2011 that Earth’s surface must warm enough to emit another 0.6 Wm-2 heat to balance absorption; the required warming is 0.2°C. The imbalance has probably increased since 2011 and is likely to increase further with more GHG emissions. Over the last 100 years (since 1919), GSTs have risen 1.27°C, including 1.45°C for the land surface (GLST) alone [1]. The GST warming rate from 2000 to 2020 was 0.24°C per decade, but 0.35 over the most recent decade [1,2]. At this rate, warming will exceed 2°C in 2058 for GST and in 2043 for GLST only.

Paleoclimate Analysis

Atmospheric CO2 levels have risen 47% since 1750, including 40% since 1880 when NASA’s temperature records begin [8]. CH4 levels have risen 114% since 1880. CO2 levels of 415 parts per million (ppm) in 2020 are the highest since 14.1 to 14.5 Mya, when they ranged from 430 to 465 ppm [9]. The deep ocean then (over 400 ky) ranged around 5.6°C±1.0°C warmer [10] and seas were 25-40 meters higher [9]. CO2 levels were almost as high (357 to 405 ppm) 4.0 to 4.2 Mya [11,12]. SSTs then were around 4°C±0.9°C warmer and seas were 20-35 meters higher [11,12].

The higher sea levels in these two earlier eras tell us that ice then was gone from almost all of the Greenland (GIS) and West Antarctic (WAIS) ice sheets. They hold an estimated 10 meters (7 and 3.2 modeled) of SLR between them [13,14]. Other glaciers (chiefly in Arctic islands, the Himalayas, Canada, Alaska, and Siberia) hold perhaps 25 cm of SLR [15]. Ocean thermal expansion (OTE), currently about (~) 1 mm/year [5], is another factor in SLR. This corresponds to the world ocean (to the bottom) currently warming by ~0.002°Kyr-1. The higher sea levels 4 and 14 Mya indicate 10-30 meters of SLR that could only have come from the East Antarctic ice sheet (EAIS). This is 17-50% of the current EAIS volume. Two-thirds of the WAIS is grounded below sea level, as is 1/3 in the EAIS [16]. Those very areas (which are larger in the EAIS than the WAIS) include the part of East Antarctica most likely to be subject to ice loss over the next few centuries [17]. Sediments from millions of years ago show that the EAIS then had retreated hundreds of kilometers inland [18].

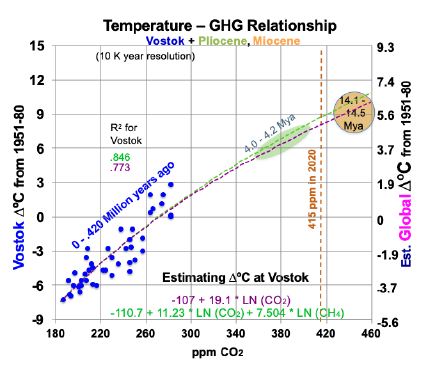

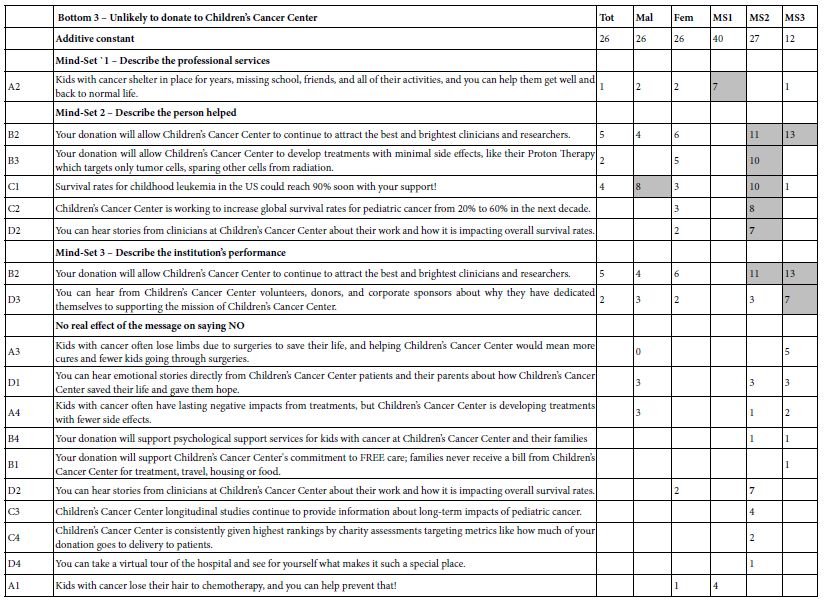

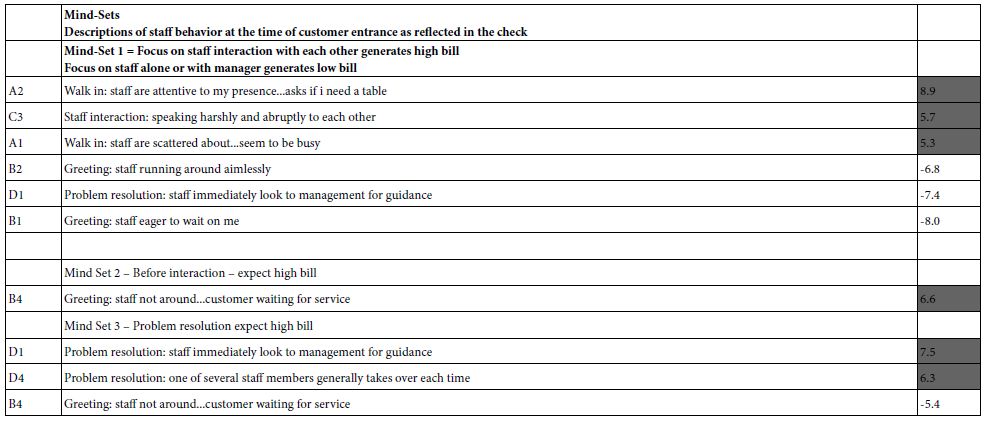

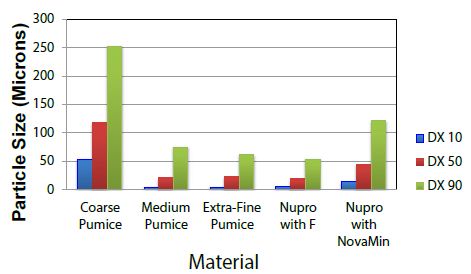

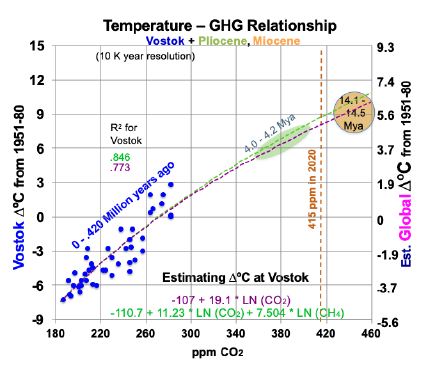

CO2 levels now are somewhat higher than they were 4 Mya, based on the current 415 ppm. This raises the possibility that current CO2 levels will warm Earth’s surface 4.5 to 5.0°C, best estimate 4.9°, over 1880 levels. (This is 3.4 to 3.9°C warmer than the current 1.1°C.) Consider Vostok ice core data that covers 430 ky [19]. Removing the time variable and scatter-plotting ∆°C against CO2 levels as blue dots (the same can be done for CH4), gives Figure 2. Its observations span the last 430 ky, at 10 ky resolution starting 10 kya.

Figure 2: Temperature to Greenhouse Gas Relationship in the Past.

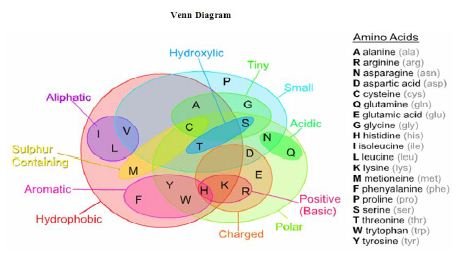

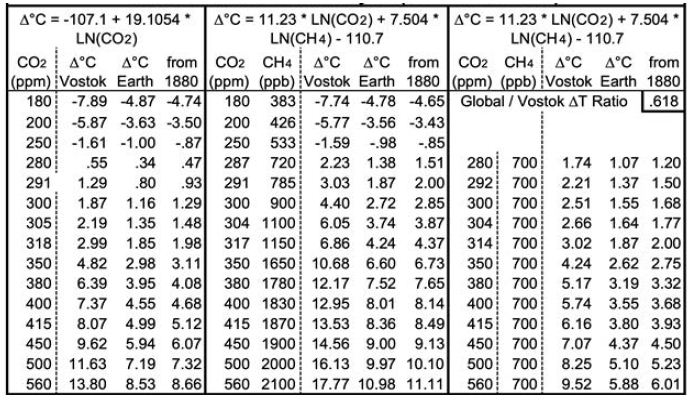

Superimposed on Figure 2 are trend lines from two linear regression equations, using logarithms, for temperatures at Vostok (left-hand scale): one for CO2 (in ppm) alone and one for both CO2 and CH4 (ppb). The purple trend line in Figure 2, from Equation (1) for Vostok, uses only CO2. 95% confidence intervals in this study are shown in parentheses with ±.

(1) ∆°C = -107.1 (±17.7) + 19.1054 (±3.26) ln(CO2).

The t-ratios are -11.21 and 11.83 for the intercept and CO2 concentration, while R2 is 0.773 and adjusted R2 is 0.768. The F statistic is 139.9. All are highly significant. This corresponds to a climate sensitivity of 13.2°C at Vostok [19.1054 * ln (2)] for doubled CO2, within the range of 180 to 465 ppm CO2. As shown below, most of this is due to albedo changes and other amplifying feedbacks. Therefore, climate sensitivity will decline as ice and snow become scarce and Earth’s albedo stabilizes. The green trend line in Figure 2, from Equation (2) for Vostok, adds a CH4 variable.

(2) ∆°C = -110.7 (±14.8) +11.23 (±4.55) ln(CO2) + 7.504 (±3.48) ln(CH4).

The t-ratios are -15.05, 4.98, and 4.36 for the intercept, CO2, and CH4. R2 is 0.846 and adjusted R2 is 0.839. The F statistic of 110.2 is highly significant. To translate temperature changes at the Vostok surface (left-hand axis) over 430 ky to changes in GST (right-hand axis), the ratio of polar change to global over the past 2 million years is used, from Snyder [20]. Snyder examined temperature data from many sedimentary sites around the world over 2 My. Her results yield a ratio for polar to global warming: 0.618. This relates the left- and right-hand scales in Figure 2. The GST equations, global instead of Vostok local, corresponding to Equations (1) and (2) for Vostok, but using the right-hand scale for global temperature, are:

(3) ∆°C = -66.19 + 11.807 ln(CO2) and

(4) ∆°C = -68.42 + 6.94 ln(CO2) + 4.637 ln(CH4).

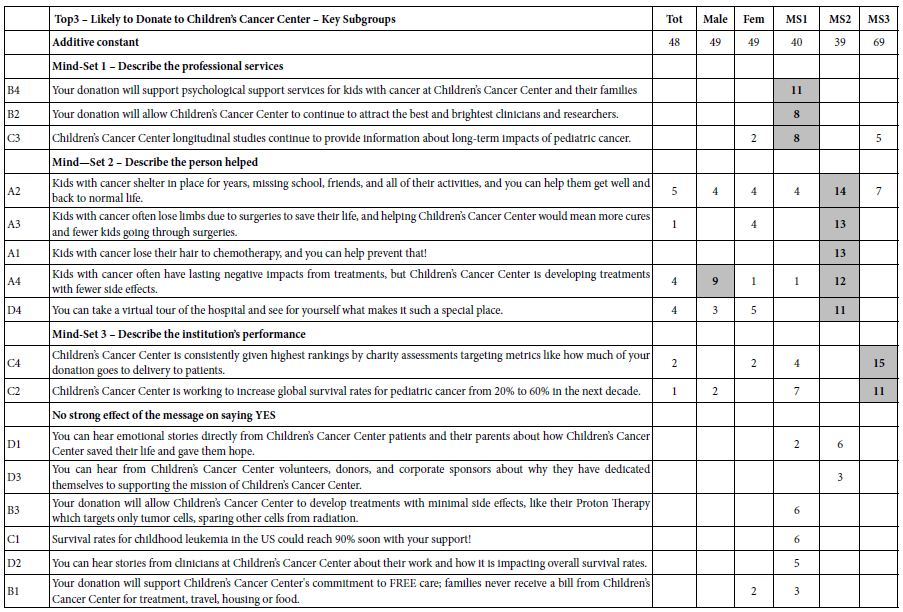

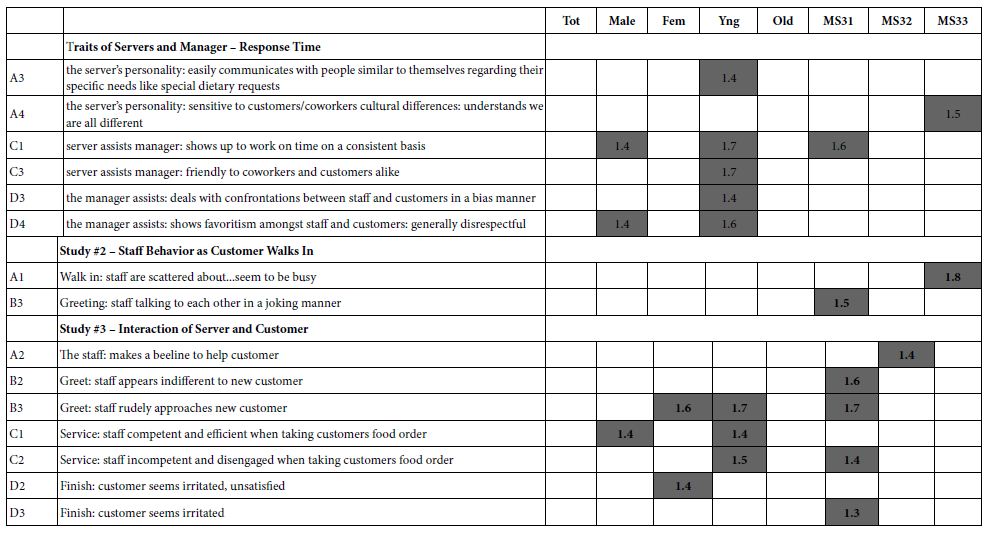

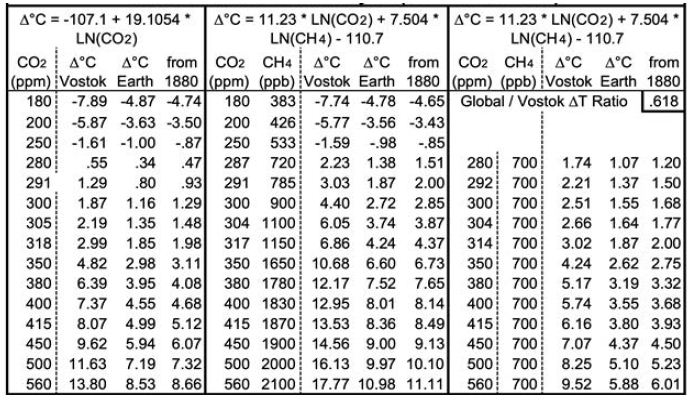

Both equations yield good fits for 14.1 to 14.5 Mya and 4.0 to 4.2 Mya. Equation 3 yields a GST climate sensitivity estimate of 8.2° (±1.4) for doubled CO2. Table 1 below shows the corresponding GSTs for various CO2 and CH4 levels. CO2 levels range from 180 ppm, the lowest recorded during the past four ice ages, to twice the immediately “pre-industrial” level of 280 ppm. Columns D, I and N add 0.13°C to their preceding columns, the difference the 1880 GST and the 1951-80 mean GST used for the ice cores. Rows are included for CO2 levels corresponding to 1.5 and 2°C warmer than 1880, using the two equations, and for the 2020 CO2 level of 415 ppm. The CH4 levels (in ppb) in column F are taken from observations or extrapolated. The CH4 levels in column K are approximations of the CH4 levels about 1880, before human activity raised CH4 levels much – from some mixture of fossil fuel extraction and leaks, landfills, flooded rice paddies, and large herds of cattle.

Other GHGs (e.g., N2O and some not present in the Vostok ice cores, such as CFCs) are omitted in this discussion and in modeling future changes. Implicitly, this simplifying assumption is that the weighted rate of change of other GHGs averages the same as CO2.

Implications

Applying Equation (3) using only CO2, now at 415 ppm, yields a future GST 4.99°C warmer than the 1951-80 baseline. This translates to 5.12°C warmer than 1880, or 3.99°C warmer than 2018-2020 (2). This is consistent not only with the Vostok ice core records, but also with warmer Pliocene and Miocene records using ocean sediments from 4 and 14 Mya. However, when today’s CH4 levels, ~ 1870 ppb, are used in Equation (4), indicated equilibrium GST is 8.5°C warmer than 1880. Earth’s GST is currently far from equilibrium.

Consider the levels of CO2 and CH4 required to meet Paris goals. To hold GST warming to 2°C requires reducing atmospheric CO2 levels to 318 ppm, using Equation (3), as shown in Table 1. This requires CO2 removal (CDR), at first cut, of (415-318)/(415-280) = 72% of human CO2 emissions to date, plus any future ones. Equation (3) also indicates that holding warming to 1.5°C requires reducing CO2 levels to 305 ppm, equivalent to 81% CDR. Using Equation (4) with pre-industrial CH4 levels of 700 ppb, consistent with 1750, yields 2°C GST warming for CO2 at 314 ppm and 1.5°C for 292 ppm CO2. Human carbon emissions from fossil fuels from 1900 through 2020 were about 1600 gigatonnes (GT) of CO2, or about 435 GT of carbon [21]. Thus, using Equation (3) yields an estimated remaining carbon budget, to hold GST warming to 2°C, of negative 313 (±54) GT of carbon, or ~72% of fossil fuel CO2 emissions to date. This is only the minimum CDR required. First, removal of other GHGs may be required. Second, any further human emissions make the remaining carbon budget even more negative and require even more CDR. Natural carbon emissions, led by permafrost ones, will increase. Albedo feedbacks will continue, warming Earth farther. Both will require still more CDR. So, the true remaining carbon budget may actually be in the negative 400-500 GT range, and most certainly not hundreds of GT greater than zero.

Table 1: Projected Equilibrium Warming across Earth’s Surface from Vostok Ice Core Analysis (1951-80 Baseline).

The difference between current GSTs and equilibrium GSTs of 5.1 and 8.5°C stem from lag effects. The lag effects come mostly from albedo changes and their feedbacks. Most albedo changes and feedbacks happen over days to decades to centuries. Ones due to land ice and vegetation changes can continue over longer timescales. However, cloud cover and water vapor changes happen over minutes to hours. The specifics (except vegetation, not examined or modelled) are detailed in the Feedback Pathways section below.

However, the bottom two lines of Table 1 probably overestimate the temperature effects of 500 and 560 ppm of CO2, as discussed further below. This is because albedo feedbacks from ice and snow, which in large measure underlie the derivations from the ice core, decline with higher temperatures outside the CO2 range (180-465 ppm) used to derive and validate Equations (1) through (4).

Feedback Pathways to Warming Indicated by Paleoclimate Analysis

To hold warming to 2°C or even 1.5°, large-scale CDR is required, in addition to rapid reductions of CO2 and CH4 emissions to almost zero. As we consider the speed of our required response, this study examines: (1) the physical factors that account for this much warming and (2) the possible speed of the warming. As the following sections show, continued emissions speed up amplifying feedback processes, making “equilibrium” GSTs still higher. So, rapid emission reductions are the necessary foundation. But even an immediate end to human carbon emissions will be far from enough to hold warming to 2°C.

The first approach to projecting our climate future, in the Temperature Record section above, drew lessons from the past. The second approach, in the Feedback Pathways section here and below, examines the physical factors that account for the warming. Albedo effects, where Earth reflects less sunlight, will grow more important over the coming decades, in part because human emissions will decline. The albedo effects include sulfate loss from ending coal burning, plus reduced extent of snow, sea ice, land-based ice, and cloud cover. Another key factor is added water vapor, a powerful GHG, as the air heats up from albedo changes. Another factor is lagged surface warming, since the deeper ocean heats up more slowly than the surface. It will slowly release heat to the atmosphere, as El Niños do.

A second group of physical factors, more prominent late this century and beyond, are natural carbon emissions due to more warming. Unlike albedo changes, they alter CO2 levels in the atmosphere. The most prominent is from permafrost. Other major sources are increased microbial respiration in soils currently not frozen; carbon evolved from warmer seas; release of seabed CH4 hydrates; and any net decreased biomass in forests, oceans, and elsewhere.

This study estimates rough magnitudes and speeds of 13 factors: 9 albedo changes (including two for sea ice and four for land ice); changes in atmospheric water vapor and other ocean-warming effects; human carbon emissions; and natural emissions – from permafrost, plus a multiplier for the other natural carbon emissions. Characteristic time scales for these changes to play out range from decades for sulfates, northern and southern sea ice, human carbon emissions, and non-polar land ice; to centuries for snow, permafrost, ocean heat content, and land ice grounded below sea level; to millennia for other land ice. Cloud cover and water vapor respond in hours to days, but never disappear. The model also includes normal rock weathering, which removes about 1 GT of CO2 per year [22], or about 3% of human emissions.

Anthropogenic sulfur loss and northern sea ice loss will be complete by 2100 and likely more than half so by 2050, depending on future coal use. Snow cover and cloud cover feedbacks, which respond quickly to temperature change, will continue. Emissions from permafrost are modeled as ramping up in an S-curve through 2300, with small amounts thereafter. Those from seabed CH4 hydrates and other natural sources are assumed to ramp up proportionately with permafrost: jointly, by half as much. Ice loss from the GIS and WAIS grounded below sea level is expected to span many decades in the hottest scenarios, to a few centuries in the coolest ones. Partial ice loss from the EAIS, led by the 1/3 that is grounded below sea level, will happen a bit more slowly. Other polar ice loss should happen still more slowly. Warming the deep oceans, to reestablish equilibrium at the top of the atmosphere, should continue for at least a millennium, the time for a circuit of the world thermohaline ocean circulation.

This analysis and model do not include changes in (a) black carbon; (b) mean vegetation color, as albedo effects of grass replacing forests at lower latitudes may outweigh forests replacing tundra and ice at higher latitudes; (c) oceanic and atmospheric circulation; (d) anthropogenic land use; (e) Earth’s orbit and tilt; or (f) solar output.

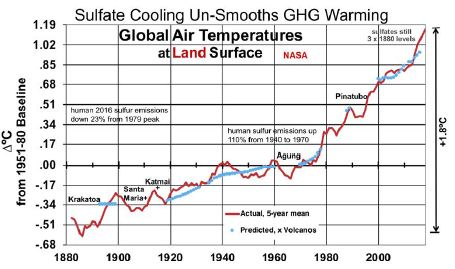

Sulfate Effects

SO4 in the air intercepts incoming sunlight before it arrives at Earth’s surface, both directly and indirectly via formation of cloud condensation nuclei. It then re-radiates some of that energy upward, for a net cooling effect at Earth’s surface. Mostly, sulfur impurities in coal are oxidized to SO2 in burning. SO2 is converted to SO4 by chemical reactions in the troposphere. Residence times are measured in days. Including cooling from atmospheric SO4 concentrations explains a great deal of the variation between the steady rise in CO2 concentrations and the variability of GLST rise since 1880. Human SO2 emissions rose from 8 Megatonnes (MT) in 1880 to 36 MT in 1920, 49 in 1940, and 91 in 1960. They peaked at 134 MT in 1973 and 1979, before falling to 103-110 during 2009-16 [23]. Corresponding estimated atmospheric SO4 concentrations rose from 41 parts per billion (ppb) in 1880 (and a modestly lower amount before then), to 90 in 1920, 85 in 1940, and 119 in 1960, before reaching peaks of 172-178 during 1973-80 [24] and falling to 130-136 over 2009-16. Some atmospheric SO4 is from natural sources, notably dimethyl sulfides from some ocean plankton, some 30 ppb. Volcanoes are also an important source of atmospheric sulfates, but only episodically (mean 8 ppb) and chiefly in the stratosphere (from large eruptions), with a typical residence time there of many months.

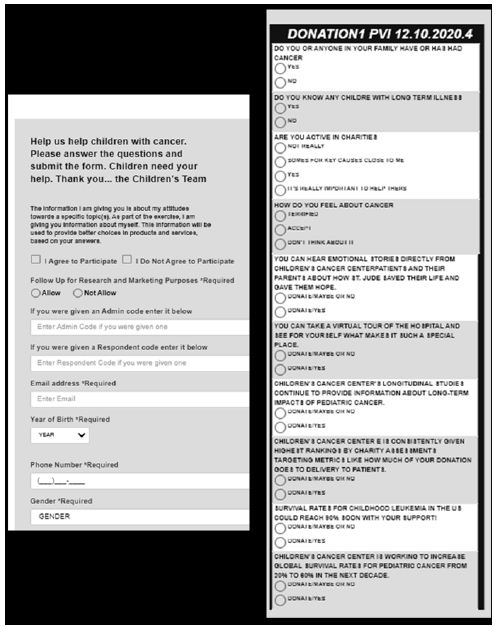

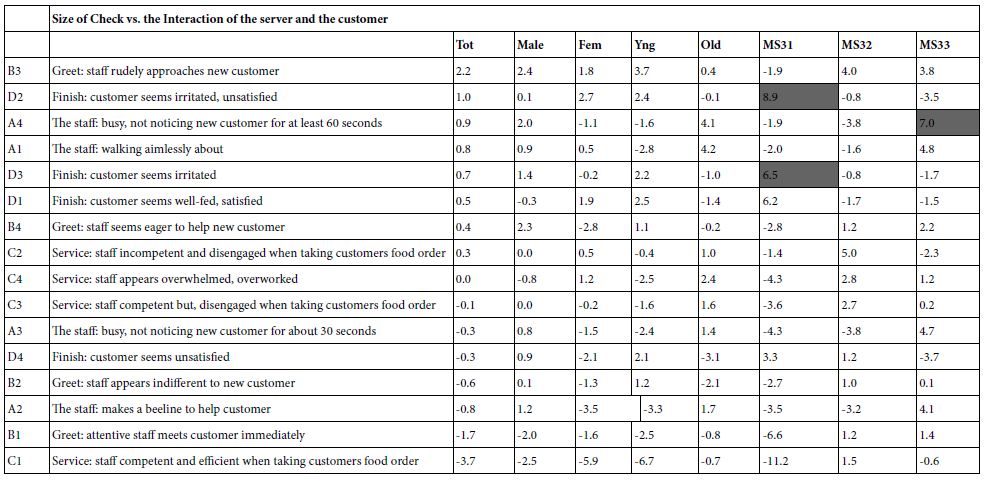

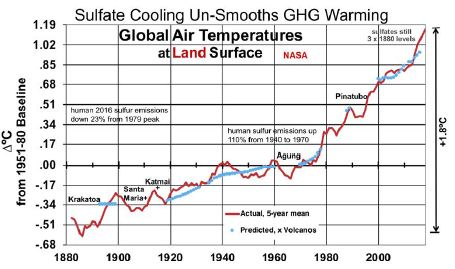

Figure 3 shows the results of a linear regression analysis, in blue, of ∆°C from the thermometer record and concentrations of CO2, CH4, and SO4. SO4 concentrations between the dates referenced above are interpolated from human emissions, added to SO4 levels when human emissions were very small (1880). All variables shown are 5-year moving averages and SO4 is lagged by 1 year. CO2, CH4, and SO4 are measured in ppm, ppb and ppb, respectively. The near absence of an upward trend in GST from 1940 to 1975 happened at a time when human SO2 emissions rose 170% from 1940 to 1973 [23]. This large SO4 cooling effect offset the increased GHG warming effect, as shown in Figure 3. The analysis shown in Equation (5) excludes the years influenced by the substantial volcanic eruptions shown. It also excludes the 2 years before and 2-4 years after the years of volcanic eruptions that reached the stratosphere, since 5-year moving temperature averages are used. In particular, it excludes data from the years surrounding eruptions labeled in Figure 3, plus smaller but substantial eruptions in 1886, 1901-02, 1913, 1932-33, 1957, 1979-80, 1991 and 2011. This leaves 70 observations in all.

Figure 3: Land Surface Temperatures, Influenced by Sulfate Cooling.

Equation (5)’s predicted GLSTs are shown in blue, next to actual GLSTs in red.

(5) ∆°C = -20.48 (±1.57) + 09 (±0.65) ln(CO2) + 1.25 (±0.33) ln(CH4) – 0.00393 (±0.00091) SO4

R2 is 0.9835 and adjusted R2 0.9828. The F-statistic is 1,312, highly significant. T-ratios for CO2, CH4, and SO4 respectively are 7.10, 7.68, and -8.68. This indicates that CO2, CH4, and SO4 are all important determinants of GLSTs. The coefficient for SO4 indicates that reducing SO4 by 1 ppb will increase GLST by 0.00393°C. Deleting the remaining human 95 ppb of SO4 added since 1880, as coal for power is phased out, would raise GLST by 0.37°C.

Snow

Some 99% of Earth’s snow cover, outside of Greenland and Antarctica, is in the northern hemisphere (NH). This study estimates the current albedo effect of snow cover in three steps: area, albedo effect to date, and future rate of snow shrinkage with rising temperatures. NH snow cover averages some 25 million km2 annually [25,26]. 82% of month-km2 coverage is during November through April. 25 million km2 is 2.5 times the 10 million km2 mean annual NH sea ice cover [27]. Estimated NH snow cover declined about 9%, about 2.2 million km2, from 1967 to 2018 [26]. Chen et al. [28] estimated that NH snow cover decreased by 890,000 km2 per decade for May to August over 1982 to 2013, but increased by 650,000 km2 per decade for November to February. Annual mean snow cover fell 9% over this period, as snow cover began earlier but also ended earlier: 1.91 days per decade [28]. These changes resulted in weakened snow radiative forcing of 0.12 (±0.003) W m-2 [28]. Chen estimated the NH snow timing feedback as 0.21 (±0.005) W m-2 K-1 in melting season, from 1982 to 2013 [28].

Future Snow Shrinkage

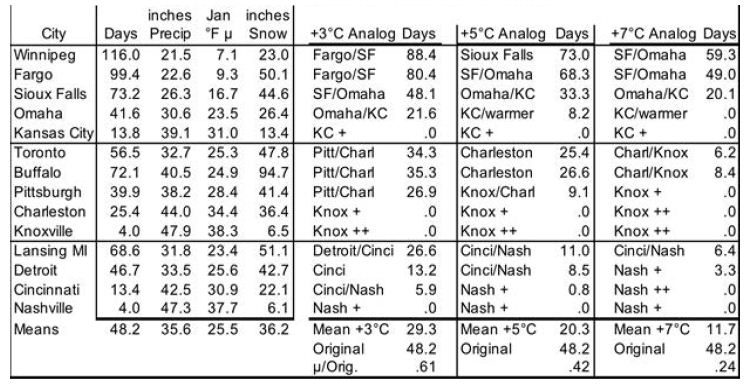

However, as GST warms further, annual mean snow cover will decline substantially with GST 5°C warmer and almost vanish with 10°. This study considers analog cities for snow cover in warmer places and analyzes data for them. It follows with three latitude and precipitation adjustments. The effects of changes in the timing of when snow is on the ground (Chen) are much smaller than from how many days snow is on the ground (see analog cities analysis, below). So, Chen’s analysis is of modest use for longer time horizons.

NH snow-covered area is not as concentrated near the pole as sea ice. Thus, sun angle leads to a larger effect by snow on Earth’s reflectivity. The mean latitude of northern snow cover, weighted over the year, is about 57°N [29], while the corresponding mean latitude of NH sea ice is 77 to 78°N. The sine of the mean sun angle (33°) on snow, 0.5454, is 2.52 times that for NH sea ice (12.5° and 0.2164). The area coverage (2.5) times the sun angle effect (2.52) suggests a cooling effect of NH snow cover (outside Greenland) about 6.3 times that for NH sea ice. [At high sun angles, water under ice is darker (~95% absorbed or 5% reflected when the sun is overhead, 0°) than rock, grass, shrubs, and trees under snow. This suggests a greater albedo contrast for losing sea ice than for losing snow. However, at the low sun angles that characterize snow latitudes, water reflects more sunlight (40% at 77° and 20% at 57°), leaving much less albedo contrast – with white snow or ice – than rocks and vegetation. So, no darkness adjustment is modeled in this study]. Using Hudson’s 2011 estimate [30] for Arctic sea ice (see below) of 0.6 W m-2 in future radiative forcing, compared to 0.1 to date for the NH sea ice’s current cooling effect, indicates that the current cooling effect of northern snow cover is about 6.3 times 0.6 W m-2 = 3.8 W m-2. This is 31 times the effect of snow cover timing changes, from Chen’s analysis.

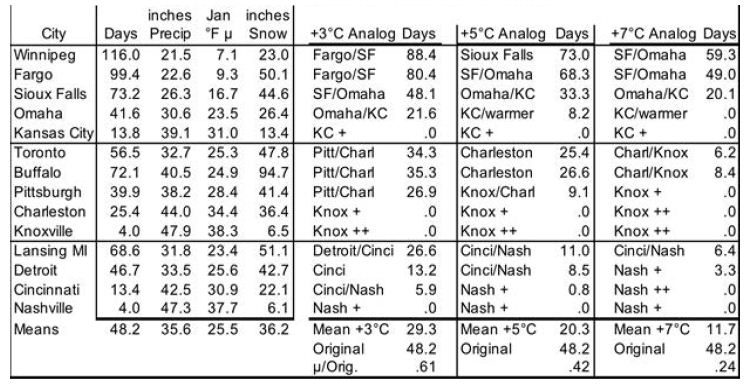

To model evolution of future snow cover as the NH warms, analog locations are used for changes in snow cover’s cooling effect as Earth’s surface warms. This cross-sectional approach uses longitudinal transects: days of snow cover at different latitudes along roughly the same longitude. For the NH, in general (especially as adjusted for altitude and distance from the ocean), temperatures increase as one proceeds southward, while annual days of snow cover decrease. Three transects in the northern US and southern Canada are especially useful, because the increases in annual precipitation with warmer January temperatures somewhat approximate the 7% more water vapor in the air per 1°C of warming (see “In the Air” section for water vapor). The transects shown in Table 2 are (1) Winnipeg, Fargo, Sioux Falls, Omaha, Kansas City; (2) Toronto, Buffalo, Pittsburgh, Charleston WV, Knoxville; and (3) Lansing, Detroit, Cincinnati, Nashville. Pooled data from these 3 transects, shown at the bottom of Table 2, indicate 61% as many days as now with snow cover ≥ 1 inch [31] with 3°C local warming, 42% with 5°C, and 24% with 7°C. However, these degrees of local warming correspond to less GST warming, since Earth’s land surface has warmed faster than the sea surface and observed warming is generally greater as one proceeds from the equator toward the poles; [1,2,32] the gradient is 1.5 times the global mean for 44-64°N and 2.0 times for 64-90°N [32]. These latitude adjustments for local to global warming pair 61% as many snow cover days with 2°C GLST warming, 42% with 3°C, and 24% with 4°C. This translates to approximately a 19% decrease in days of snow cover per 1°C warming.

Table 2: Snow Cover Days for Transects with ~7% More Precipitation per °C. Annual Mean # of Days with ≥ 1 inch of Snow on Ground.

This study makes three adjustments to the 19%. First, the three transects feature precipitation increasing only 4.43% (1.58°C) per 1°C warming. This is 63% of the 7% increase in global precipitation per 1°C warming. So, warming may bring more snowfall than the analogs indicate directly. Therefore the 19% decrease in days of snow cover per 1°C warming of GLST is multiplied by 63%, for a preliminary 12% decrease in global snow cover for each 1°C GLST warming. Second, transects (4) Edmonton to Albuquerque and (5) Quebec to Wilmington NC, not shown, lack clear precipitation increases with warming. But they yield similar 62%, 42%, and 26% as many days of snow cover for 2, 3, and 4°C increases in GST. Since the global mean latitude of NH snow cover is about 57°, the southern Canada figure should be more globally representative than the 19% figure derived from the more southern US analysis. Use of Canadian cities only (Edmonton, Calgary, Winnipeg, Sault Ste. Marie, Toronto, and Quebec, with mean latitude 48.6°N) yields 73%, 58%, and 41% of current snow cover with roughly 2, 3, and 4°C warming. This translates to a 15% decrease in days of snow cover in southern Canada per 1°C warming of GLST. 63% of this, for the precipitation adjustment, yields 9.5% fewer days of snow cover per 1°C warming of GLST. Third, the southern Canada (48.6°N) figure of 9.5% warrants a further adjustment to represent an average Canadian and snow latitude (57°N). Multiplying by sin(48.6°)/sin(57°) yields 8.5%. The story is likely similar in Siberia, Russia, north China, and Scandinavia. So, final modeled snow cover decreases by 8.5% (not 19, 12 or 9.5%) of current amounts for each 1°C rise in GLST. In this way, modeled snow cover vanishes completely at 11.8°C warmer than 1880, similar to the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) GSTs 55 Mya [3].

Ice

Six ice albedo changes are calculated separately: for NH and Antarctic (SH) sea ice, and for land ice in the GIS, WAIS, EAIS, and elsewhere (e.g., Himalayas). Ice loss in the latter four leads to SLR. This study considers each in turn.

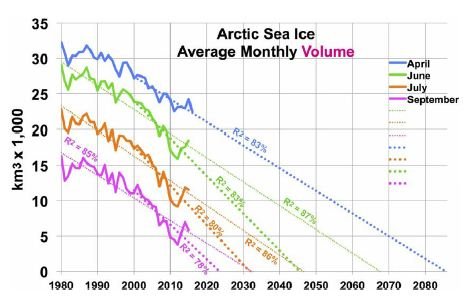

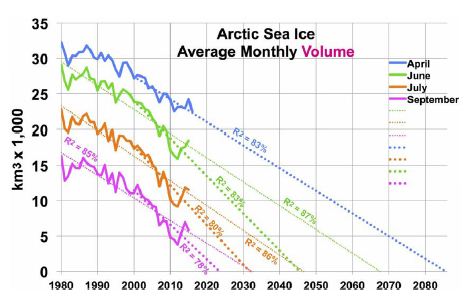

Sea Ice

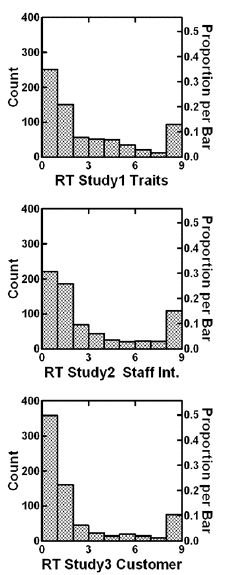

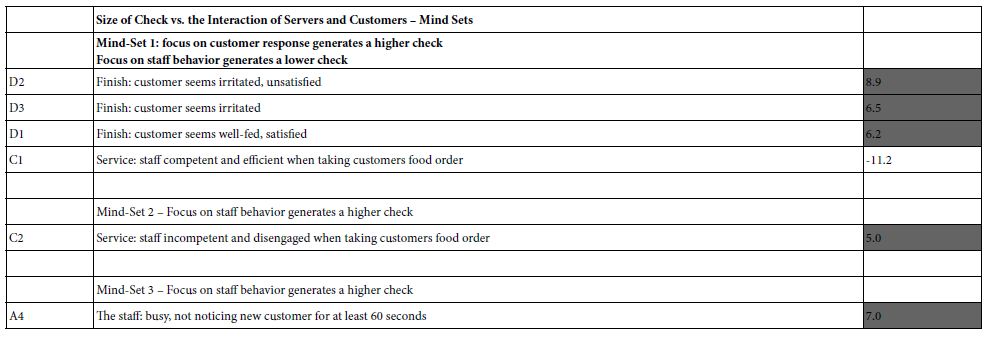

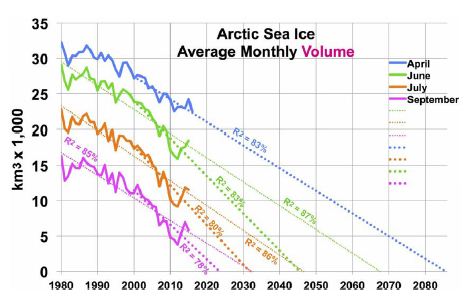

Arctic sea ice area has shown a shrinking trend since satellite coverage began in 1979. Annual minimum ice area fell 53% over the most recent 37 years [33]. However, annual minimum ice volume shrank faster, as the ice also thinned. Estimated annual minimum ice volume fell 73% over the same 37 years, including 51% in the most recent 10 years [34]. Trends in Arctic sea ice volume [34] are shown in Figure 4, with their corresponding R2, for four months. One set of trend lines (small dots) is based on data since 1980, while a second, steeper set (large dots) uses data since 2000. (Only four months are shown, since July ice volume is like November’s and June ice volume is like January’s). The graph suggests sea ice will vanish from the Arctic from June through December by 2050. Moreover, NH sea ice may vanish totally by 2085 in April, the minimum ice volume month. That is, current volume trends yield an ice-free Arctic Ocean about 2085.

Figure 4: Arctic Sea Ice Volume by Month and Year, Past and Future.

Hudson estimated that loss of Arctic sea ice would increase radiative forcing in the Arctic by an amount equivalent to 0.7 W m-2, spread over the entire planet, of which 0.1 W m-2 had already occurred [30]. That leaves 0.6 W m-2 of radiative forcing still to come, as of 2011. This translates to 0.31°C warming yet to come (as of 2011) from NH sea ice loss. Trends in Antarctic sea ice are unclear. After three record high winter sea ice years in 2013-15, record low Antarctic sea ice was recorded in 2017-19 and 2020 is below average [27]. If GSTs rise enough, eventually Antarctic land ice and sea ice areas should shrink. Roughly 2/3 of Antarctic sea ice is associated with West Antarctica [35]. Therefore, 2/3 of modeled SH sea ice loss corresponds to WAIS ice volume loss and 1/3 to EAIS. However, to estimate sea ice area, change in estimated ice volume is raised to the 1.5 power (using the ratio of 3 dimensions of volume to 2 of area). This recognizes that sea ice area will diminish more quickly than the adjacent land ice volume of the far thicker WAIS (including the Antarctic Peninsula) and the EAIS.

Land Ice

Paleoclimate studies have estimated that global sea levels were 20 to 35 meters higher than today from 4.0 to 4.2 Mya [13,14]. This indicates that a large fraction of Earth’s polar ice had vanished then. Earth’s GST then was estimated to be 3.3 to 5.0°C above the 1951-80 mean, for CO2 levels of 357-405 ppm. Another study estimated that global sea levels were 25-40 meters higher than today’s from 14.1 to 14.5 Mya [11]. This suggests 5 meters more of SLR from vanished polar ice. The deep ocean then was estimated to be 5.6±1.0°C warmer than in 1951-80, in response to still higher CO2 levels of 430-465 ppm CO2 [11,12]. Analysis of sediment cores by Cook [20] shows that East Antarctic ice retreated hundreds of kilometers inland in that time period. Together, these data indicate large polar ice volume losses and SLR in response to temperatures expected before 2400. This tells us about total amounts, but not about rates of ice loss.

This study estimates the albedo effect of Antarctic ice loss as follows. The area covered by Antarctic land ice is 1.4 times the annual mean area covered by NH sea ice: 1.15 for the EAIS and 0.25 for the WAIS. The mean latitudes are not very different. Thus, the effect of total Antarctic land ice area loss on Earth’s albedo should be about 1.4 times that 0.7 Wm-2 calculated by Hudson for NH sea ice, or about 1.0 Wm-2. The model partitions this into 0.82 Wm-2 for the EAIS and 0.18 Wm-2 for the WAIS. Modeled ice mass loss proceeds more quickly (in % and GT) for the WAIS than for the EAIS. Shepherd et al. [36] calculated that Antarctica’s net ice volume loss rate almost doubled, from the period centered on 1996 to that on 2007. That came from the WAIS, with a compound ice mass loss of 12% per year from 1996 to 2007, as ice volume was estimated to grow slightly in the EAIS [36,37] over this period. From 1997 to 2012, Antarctic land ice loss tripled [36]. Since then, Antarctic land ice loss has continued to increase by a compound rate of 12% per year [37]. This study models Antarctic land ice losses over time using S-curves. The curve for the WAIS starts rising at 12% per year, consistent with the rate observed over the past 15 years, starting from 0.4 mm per year in 2010, and peaks in the 2100s. Except in CDR scenarios, remaining WAIS ice is negligible by 2400. Modeled EAIS ice loss increases from a base of 0.002 mm per year in 2010. It is under 0.1% in all scenarios until after 2100, peaks from 2145 to 2365 depending on scenario, and remains under 10% by 2400 in the three slowest-warming scenarios.

The GIS area is 17.4% of the annual average NH sea ice coverage [27,38], but Greenland experiences (on average) a higher sun angle than the Arctic Ocean. This suggests that total GIS ice loss could have an albedo effect of 0.174 * cos (72°)/cos (77.5°) = 0.248 times that of total NH sea ice loss. This is the initial albedo ratio in the model. The modeled GIS ice mass loss rate decreases from 12% per year too, based on Shepherd’s GIS findings for 1996 to 2017 [37]. Robinson’s [39] analysis indicated that the GIS cannot be sustained at temperatures warmer than 1.6°C above baseline. That threshold has already been exceeded locally for Greenland. So it is reasonable to expect near total ice loss in the GIS if temperatures stay high enough for long enough. Modeled GIS ice loss peaks in the 2100s. It exceeds 80% by 2400 in scenarios lacking CDR and is near total by then if fossil fuel use continues past 2050.

The albedo effects of land ice loss, as for Antarctic sea ice, are modeled as proportional to the 1.5 power of ice loss volume. This assumes that the relative area suffering ice loss will be more around the thin edges than where the ice is thickest, far from the edges. That is, modeled ice-coved area declines faster than ice volume for the GIS, WAIS, and EAIS. Ice loss from other glaciers, chiefly in Arctic islands, Canada, Alaska, Russia, and the Himalayas, is also modeled by S-curves. Modeled “other glaciers” ice volume loss in the 6 scenarios ranges from almost half to almost total, depending on the scenario. Corresponding SLR rise by 2400 ranges from 12 to 25 cm, 89% or more of it by 2100.

In the Air: Clouds and Water Vapor

As calculated by Equation (5), using 70 years without significant volcanic eruptions, GLST will rise about 0.37°C as human sulfur emissions are phased out. Clouds cover roughly half of Earth’s surface and reflect about 20% [40] of incoming solar radiation (341 W m–2 mean for Earth’s surface). This yields mean reflection of about 68 W m–2, or 20 times the combined warming effect of GHGs [41]. Thus, small changes in cloud cover can have large effects. Detecting cloud cover trends is difficult, so the error bar around estimates for forcing from cloud cover changes is large: 0.6±0.8 Wm–2K–1 [42]. This includes zero as a possibility. Nevertheless, the estimated cloud feedback is “likely positive”. Zelinka [42] estimates the total cloud effect at 0.46 (±0.26) W m–2K –1. This comprises 0.33 for less cloud cover area, 0.20 from more high-altitude ones and fewer low-altitude ones, -0.09 for increased opacity (thicker or darker clouds with warming), and 0.02 for other factors. His overall cloud feedback estimate is used for modeling the 6 scenarios shown in the Results section. This cloud effect applies both to albedo changes from less ice and snow and to relative changes in GHG (CO2) concentrations. It is already implicit in estimates for SO4 effects. 1°C warmer air contains 7% more water vapor, on average [43]. That increases radiative forcing by 1.5 W m–2 [43]. This feedback is 89% as much as from CO2 emitted from 1750 to 2011 [41]. Water vapor acts as a warming multiplier, whether from human GHG emissions, natural emissions, or albedo changes. The model treats water vapor and cloud feedbacks as multipliers. This is also done in Table 3 below.

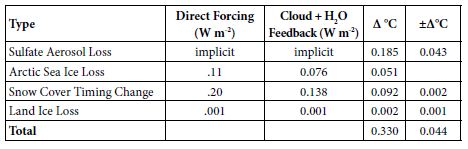

Table 3: Observed GST Warming from Albedo Changes, 1975-2016.

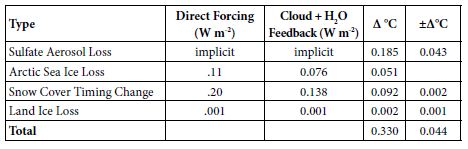

Albedo Feedback Warming, 1975-2016, Informs Climate Sensitivities

Amplifying feedbacks, from albedo changes and natural carbon emissions, are more prominent in future warming than direct GHG effects. Albedo feedbacks to date, summarized in Table 3, produced an estimated 39% of GST warming from 1975 to 2016. This came chiefly from SO4 reductions, plus some from snow cover changes and Arctic sea ice loss, with their multipliers from added water vapor and cloud cover changes. On the top line of Table 3 below, the SO4 decrease, from 177.3 ppb in 1975 to 130.1 in 2016, is multiplied by 0.00393°C/ppb SO4 from Equation (5). On the second line, in the second column, Arctic sea ice loss is from Hudson [30], updated from 0.10 to 0.11 W m–2 to cover NH sea ice loss from 2010 to 2016. The snow cover timing change effect of 0.12 W m–2 over 1982-2013 is from Chen [28]. But the snow cover data is adjusted to 1975-2016, for another 0.08 W m-2 in snow timing forcing, using Chen’s formula for W m-2 per °C warming [28] and extra 0.36°C warming over 1975-82 plus 2013-16. The amount of the land ice area loss effect is based on SLR to date from the GIS, WAIS, and non-polar glaciers. It corresponds to about 10,000 km2, less than 0.1% of the land ice area.

For the third column of Table 3, cloud feedback is taken from Zelinka [42] as 0.46 W m–2K–1. Water-vapor feedback is taken from Wadhams [43], as 1.5 W m–2K–1. The combined cloud and water-vapor feedback of 1.96 W m–2K–1 modeled here amounts to 68.8% of the 2.85 total forcing from GHGs as of 2011 [41]. Multiplying column 2 by 68.8% yields the numbers in column 3. Conversion to ∆°C in column 4 divides the 0.774°C warming from 1880 to 2011 [2] by the total forcing of 2.85 W m-2 from 1880 to 2011 [41]. This yields a conversion factor of 0.2716°C W-1m2, applied to the sum of columns 2 and 3, to calculate column 4. Error bars are shown in column 5. In summary, estimated GST warming over 1975-2016 from albedo changes, both direct (from sulfate, ice, and snow changes) and indirect (from cloud and water-vapor changes due to direct ones), totals 0.330°C. Total GST warming then was 0.839°C [2]. (This is more than the 0.774°C (2) warming from 1880 to 2011, because the increase from 2011 to 2016 was greater than the increase from 1880 to 1975.) So, the ∆GST estimated for albedo changes over 1975-2016, direct and indirect, comes to 0.330/0.839 = 39.3% of the observed warming.

1975-2016 Warming Not from Albedo Effects

The remaining 0.509°C warming over 1975-2016 corresponds to an atmospheric CO2 increase from 331 to 404 ppm [44], or 22%. This 0.509°C warming is attributed in the model to CO2, consistent with Equations (3) and (1), using the simplification that the sum total effect of other GHGs changes as the same rate as for CO2. It includes feedbacks from H2O vapor and cloud cover changes, estimated, per above, as 0.686/(1+1.686) of 0.509°C, which is 0.207°C or 24.7% of the total 0.839°C warming over 1975-2016. This leaves 0.302°C warming for the estimated direct effect of CO2 and other factors, including other GHGs and factors not modeled, such as black carbon and vegetation changes, over this period.

Partitioning Climate Sensitivity

With the 22% increase in CO2 over 1975-2016, we can estimate the change due to a doubling of CO2 by noting that 1.22 [= 404/331] raised to the power 3.5 yields 2.0. This suggests that a doubling of CO2 levels – apart from surface albedo changes and their feedbacks – leads to about 3.5 times 0.509°C = 1.78°C of warming due to CO2 (and other GHGs and other factors, with their H2O and cloud feedbacks), starting from a range of 331-404 ppm CO2. In the model, for projected temperature changes for a particular year, 0.509°C is multiplied by the natural logarithm of (the CO2 concentration/331 ppm in 1975) and divided by the natural logarithm of (404 ppm/331 ppm), that is divided by 0.1993. This yields estimated warming due to CO2 (plus, implicitly, other non-H2O GHGs) in any particular year, again apart from surface albedo changes and their feedbacks, including the factors noted that are not modelled in this study.

Using Equation (3), warming associated with doubled CO2 over the past 14.5 million years is 11.807 x ln(2.00), or 8.184°C per CO2 doubling. The difference between 8.18°C and 1.78°C, from CO2 and non-H2O GHGs, is 6.40°C. This 6.40°C climate sensitivity includes the effect of albedo changes and the consequent H2O vapor concentration. Loss of tropospheric SO4 and Arctic sea ice are the first of these to occur, with immediate water vapor and cloud feedbacks. Loss of snow and Antarctic sea ice follow over centuries to decades. Loss of much land ice, especially where grounded above sea level, happens more slowly.

Stated another way, there are two climate sensitivities: one for the direct effect of GHGs and one for amplifying feedbacks, led by albedo changes. The first is estimated as 1.8°C. The second is estimated as 6.4°C in epochs, like ours, when snow and ice are abundant. In periods with little or no ice and snow, this latter sensitivity shrinks to near zero, except for clouds. As a result, climate is much more stable to perturbations (notably cyclic changes in Earth’s tilt and orbit) when there is little snow or ice. However, climate is subject to wide temperature swings when there is lots of snow and ice (notably the past 2 million years, as seen in Figure 1).

In the Oceans

Ocean Heat Gain: In 2011, Hansen [7] estimated that Earth is absorbing 0.65 Wm-2 more than it emits. As noted above, ocean heat gain averaged 4 ZJ per year over 1967 to 1990, 7 over 1991-2005, and 10 over 2006-16. Ocean heat gain accelerated while GSTs increased. Therefore, ocean heat gain and Earth’s energy imbalance seem likely to continue rising as GSTs increase. This study models the situation that way. Oceans would need to warm up enough to regain thermal equilibrium with the air above. While oceans are gaining heat (now ~ 2 times cumulative human energy use every 3 years), they are out of equilibrium. The ocean thermohaline circuit takes about 1,000 years. So, if human GHG emissions ended today, this study assumes that it could take Earth’s oceans 1,000 years to thermally re-equilibrate heat with the atmosphere. The model spreads the bulk of that over 400 years, in an exponential decay shape. The rate peaks during 2130 to 2170, depending on the scenario. The modeled effect is about 5% of total GST warming. Ocean thermal expansion (OTE), currently about 0.8 mm/year [5], is another factor in SLR. Changes to its future values are modeled as proportional to future temperature change.

Land Ice Mass Loss, Its Albedo Effect, and Sea Level Rise: Modeled SLR derives mostly from modeled ice sheet losses. Their S-curves were introduced above. The amount and rate parameters are informed by past SLR. Sea levels have varied by almost 200 meters over the past 65 My. They were almost 125 meters lower than now during recent Ice Ages [3]. SLR reached some 70 meters higher in ice-free warm periods more than 10 Mya, especially more than 35 Mya [3]. From Figure 1, Earth was largely ice-free when deep ocean temperature (DOT) was 7°C or more, for SLR of about 73 meters from current levels, when DOT is < 2°C. This yields a SLR estimate of 15 meters/°C of DOT in warm eras. Over the most recent 110-120 ky, 110 meters of SLR is associated with 4 to 6°C GST warming (Figure 2), or 19-28 meters/°C GST in a cold era. The 15:28 warm/cold era ratio for SLR rate shows that the amount of remaining ice is a key SLR variable. However, this study projects only 1.5 to 4 meters rate of SLR by 2400 per °C of GST warming, but still rising. The WAIS and GIS together hold 10-12 meters of SLR [15,16]. So, 25-40 meter SLR during 14.1-14.5 Mya suggests that the EAIS lost about 1/3 to 1/2 of its current ice volume (20 to 30 meters of SLR, out of almost 60 today in the EAIS [45]) when CO2 levels were last at 430-465 ppm and DOTs were 5.6±1.0°C [11,12]. This is consistent with this study’s two scenarios with human CO2 emissions after 2050 and even 2100: 13 and 21 meters of SLR from the EAIS by 2400, with Δ GLSTs of 8.2 and 9.4°C. DeConto [19] suggested that sections of the EAIS grounded below sea level would lose all ice if we continue emissions at the current rate, for 13.6 or even 15 meters of SLR by 2500. This model’s two scenarios with intermediate GLST rise yield SLR closest to his projections. SLR is even higher in the two warmest scenarios. Modeled SLR rates are informed by the most recent 19,000 years of data ([46,47], chart by Robert A. Rohde). They include a SLR rate of 3 meters/century during Meltwater Pulse 1A for 8 centuries around 14 ky ago. They also include 1.5 meters/century over the 70 centuries from 15 kya to 8 kya. The DOT rose 3.3°C over 10,000 years, for an average rate of 0.033°C per century. However, the current SST warming rate is 2.0°C per century [1,2], about 60 times as great. Although only 33-40% as much ice (73 meters SLR/(73+125)) is left to melt, this suggests that rates of SLR will be substantially higher, at current rates of warming, than the 1.5 to 3 meters per century coming out of the most recent ice age. In four scenarios without CDR, mean rates of modeled SLR from 2100 to 2400 range from 4 to 11 meters per century.

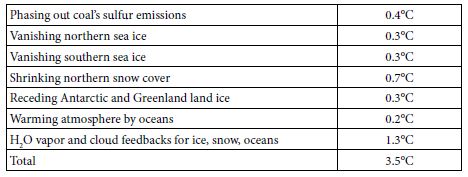

Summary of Factors in Warming to 2400

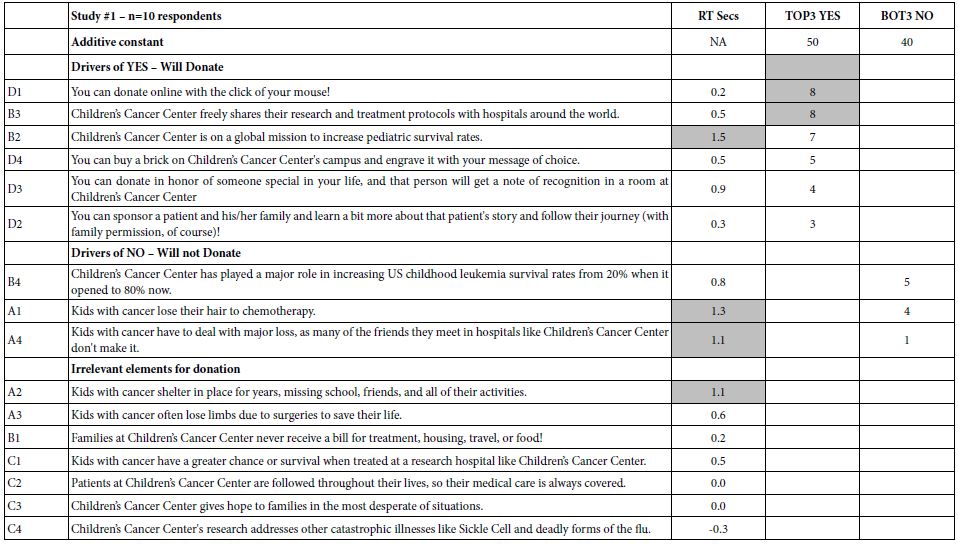

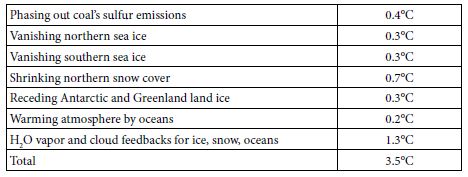

Table 4 summarizes the expected future warming effects from feedbacks (to 2400), based on the analyses above.

Table 4: Projected GST Warming from Feedbacks, to 2400.

The 3.5°C warming indicated, added to 1.1°C warming since 1880, or 4.6°C, is 0.5°C less than the 5.1°C warming based on Equation (4) from the paleoclimate analysis. This gap suggests four overlapping possibilities. First, underestimations (perhaps sea ice and clouds) may exceed overestimations (perhaps snow) for the processes shown in Table 4. Underestimation of cloud feedbacks, and their consequent warming, is quite possible. Using Zelinka’s 0.46 Wm–2K–1 in this study, instead of the IPCC central estimate of 0.6, is one possibility. Moreover, recent research suggests that cloud feedbacks may be appreciably stronger than 0.6 Wm–2K–1 [48]. Second, change in the eight factors not modelled (black carbon, vegetation and land use, ocean and air circulation, Earth’s orbit and tilt, and solar output) may provide feedbacks that, on balance, are more warming than cooling. Third, temperatures used here for 4 and 14 Mya may be overestimated or should not be used unadjusted. Notably, the joining of North and South America about 3 Mya rearranged ocean circulation and may have resulted in cooling that led to ice periodically covering much of North America [49]. Globally, Figure 1 above suggests this cooling effect may be 1.0-1.6°C. In contrast, solar output increases as our sun ages, by 7% per billion years [50], so that solar forcing is now 1.4 W m–2 more than 14 Mya and 0.4 more than 4 Mya. A brighter sun now indicates that, for the same GHG levels and albedo levels, GST would be 0.7°C warmer than it would have been 14 Mya and 0.2°C warmer than 4 Mya. Fourth, nothing (net) may be amiss. Underestimated warming (perhaps permafrost, clouds, sea ice, black carbon) may balance overestimated warming (perhaps snow, land ice, vegetation). The gap would then be due to a lower albedo climate sensitivity than 6.4°C, as discussed above using data for 1975-2016, because all sea ice and much snow vanish by 2400.

Natural Carbon Emissions

Permafrost: One estimate of the amount of carbon stored in permafrost is 1,894 GT of carbon [51]. This is about 4 x carbon that humans have emitted by burning fossil fuels. It is also 2 x as much as in Earth’s atmosphere. More permafrost may lie under Antarctic ice and the GIS. DeConto [52] proposed that the PETM’s large carbon and temperature (5-6°C) excursions 55 Mya are explained by “orbitally triggered decomposition of soil organic carbon in circum-Arctic and Antarctic terrestrial permafrost. This massive carbon reservoir had the potential to repeatedly release thousands of [GT] of carbon to the atmosphere-ocean system”. Permafrost area in the Northern Hemisphere shrank 7% from 1900 to 2000 [53]. It may shrink 75-88% more by 2100 [54]. Carbon emissions from permafrost are expected to accelerate, as the ground in which they are embedded warms up. In general, near-surface air temperatures have been warming twice as fast in the Arctic as across the globe as a whole [32]. More research is needed to estimate rates of permafrost warming at depth and consequent carbon emissions. Already in 2010, Arctic permafrost emitted about as carbon as all US vehicles [55]. Part of the carbon emerges as CH4, where surface water prevents carbon under it being oxidized. That CH4 changes to CO2 in the air over several years. This study accounts for the effects of CO2 derived from permafrost. MacDougall et al. estimated that thawing permafrost can add up to ~100 ppm of CO2 to the air by 2100 and up to 300 more by 2300, depending on the four RCP emissions scenarios [56]. This is 200 GT of carbon by 2100 plus 600 GT more by 2300. The direct driver of such emissions is local temperatures near the air-soil interface, not human carbon emissions. Since warming is driven not just by emissions, but also by albedo changes and their multipliers, permafrost carbon losses from thawing may proceed faster than MacDougall estimated. Moreover, MacDougall estimated only 1,000 GT of carbon in permafrost [56], less than more recent estimates. On the other hand, a larger fraction of carbon may stay in permafrost soil in than MacDougall assumed, leaving deep soil rich in carbon, similar to that left by “recent” glaciers in Iowa.

Other Natural Carbon Emissions

Seabed CH4 hydrates may hold a similar amount of carbon to permafrost or somewhat less, but the total amount is very difficult to measure. By 2011, subsea CH4 hydrates were releasing 20-30% as much carbon as permafrost was [57]. This all suggests that eventual carbon emissions from permafrost and CH4 hydrates may be half to four times what MacDougall estimated. Also, the earlier portion of those emissions may happen faster than MacDougall estimated. In all, this study’s modeled permafrost carbon emissions range from 35 to 70 ppm CO2 by 2100 and from 54 to 441 ppm CO2 by 2400, depending on the scenario. As stated earlier, this model simply assumes that other natural carbon reservoirs will add half as much carbon to the air as permafrost does, on the same time path. These sources include outgassing from soils now unfrozen year-round, the warming upper ocean, seabed CH4 hydrates, and any net decrease in worldwide biomass.

Results

The Six Scenarios

- “2035 Peak”. Fossil-fuel emissions are reduced 94% by 2100, from a peak about 2035, and phased out entirely by 2160. Phase-out accelerates to 2070, when CO2 emissions are 25% of 2017 levels, then decelerates. Permafrost carbon emissions overtake human ones about 2080. Natural CO2 removal (CDR) mostly further acidifies the oceans. But it includes 1 GT per year of CO2 by rock weathering.

- “2015 Peak”. Fossil-fuel emissions are reduced 95% by 2100, from a peak about 2015, and phased out entirely by 2140. Phase-out accelerates to 2060, when CO2 emissions are 40% of 2017 levels, then decelerates. Compared to a 2035 peak, natural carbon emissions are 25% lower and natural CDR is similar.

- “x Fossil Fuels by 2050”, or “x FF 2050”. Peak is about 2015, but emissions are cut in half by 2040 and end by 2050. Natural CDR is the same as for the 2015 Peak, but is lower to 2050, since human CO2 emissions are less. This path has a higher GST from 2025 to 2084, while warming sooner from less SO4 outweighs less warming from GHGs.

- “Cold Turkey”. Emissions end at once after 2015. Natural CDR is only by rock weathering, since no new human CO2 emissions push carbon into the ocean. After 2060, cooling from ending CO2 emissions earlier outweighs warming from ending SO2

- “x FF 2050, CDR”. Emissions are the same as for “x FF 2050”, as is natural CDR. But human CDR ramps up in an S-curve, from less than 1% of emissions in 2015 to 25% of 2015 emissions over the 2055 to 2085 period. Then they ramp down in a reverse S-curve, to current levels in 2155 and 0 by 2200.

- “x FF 2050, 2xCDR” is like “x FF 2050, CDR”, but CDR ramps up to 52% of 2015 emissions over 2070 to 2100. From 2090, it ramps down to current levels in 2155 and 0 by 2190. CDR = 71% of CO2 emissions to 2017 or 229% of soil carbon lost since farming began [58], almost enough to cut CO2 in the air to 313 ppm, for 2°C warming.

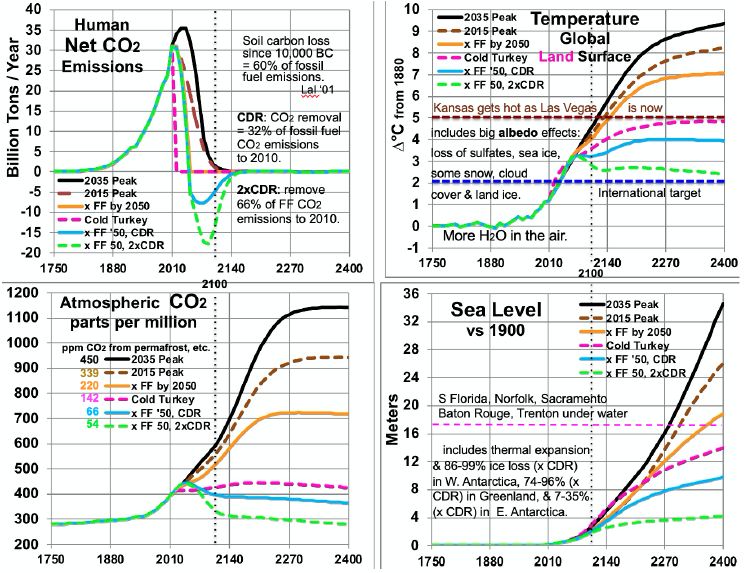

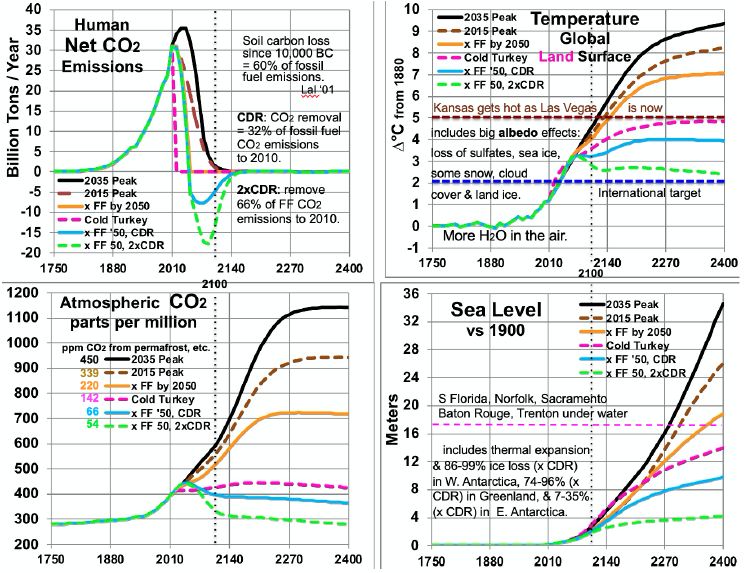

Projections to 2400

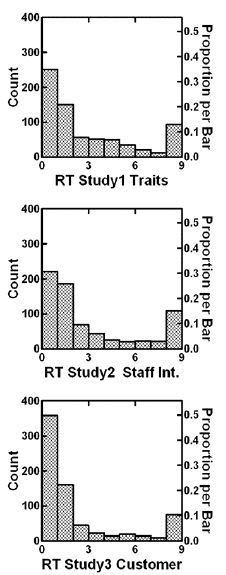

The results for the six scenarios shown in Figure 5 spread ocean warming over 1,000 years, more than half of it by 2400. They use the factors discussed above for sea level, water vapor, and albedo effects of reduced SO4, snow, ice, and clouds. Permafrost emissions are based on MacDougall’s work, adjusted upward for a larger amount of permafrost, but also downward and to a greater degree, assuming much of the permafrost carbon stays as carbon-rich soil as in Iowa. As first stated in the introduction to Feedback Pathways, the model sets other natural carbon emissions to half of permafrost emissions. At 2100, net human CO2 emissions range from -15 GT/year to +2 GT/year, depending on the scenario. By 2100, CO2 concentrations range from 350 to 570 ppm, GLST warming from 2.9 to 4.5°C, and SLR from 1.6 to 2.5 meters. CO2 levels after 2100 are determined mostly by natural carbon emissions, driven ultimately by GST changes, shown in the lower left panel of Figure 5. They come from permafrost, CH4 hydrates, unfrozen soils, warming upper ocean, and biomass loss.

Figure 5: Scenarios for CO2 Emissions and Levels, Temperatures and Sea Level.

Comparing temperatures to CO2 levels allows estimates of long-run climate sensitivity to doubled CO2. Sensitivity is estimated as ln(2)/ln(ppm/280) * ∆T. By scenario, this yields > 4.61° (probably ~5.13° many decades after 2400) for 2035 Peak, > 4.68° (probably ~5.15°) for 2015 Peak, > 5.22° (probably 5.26°) for “x FF by 2050”, and 8.07° for Cold Turkey. Sensitivities of 5.13, 5.15 and 5.26° are much less than the 8.18° derived from the Vostok ice core. This embodies the statement above, in the Partitioning Climate Sensitivity section, that in periods with little or no ice and snow [here, ∆T of 7°C or more – the 2035 and 2015 Peaks and x FF by 2050 scenarios], this albedo-related sensitivity shrinks to 3.3-3.4°. Meanwhile, the Cold Turkey scenario (with a good bit more snow and a little more ice) matches well the relationship from the ice core (and validated to 465 ppm CO2, in the range for Cold Turkey: 4 and 14 Mya). Another perspective is the climate sensitivity starting from a base not of 280 ppm CO2, but from a higher level: 415 ppm, the current level and the 2400 level in the Cold Turkey case. Doubling CO2 from 415 to 830 ppm, according to the calculations underlying Figure 5, yields a temperature in 2400 between the x FF by 2050 and the 2015 Peak cases, about 7.6°C and rising, to perhaps 8.0°C after 1-2 centuries. This yields a climate sensitivity of 8.0 – 4.9 = 3.1°C in the 415-830 ppm range. The GHG portion of that remains near 1.8° (see Partitioning Climate Sensitivity above). But the albedo feedbacks portion shrinks further, from 6.4°, past 3.3° to 1.3°, as thin ice and most snow are gone, as noted above, plus all SO4 from fossil fuels, leaving mostly thick ice and feedbacks from clouds and water vapor.

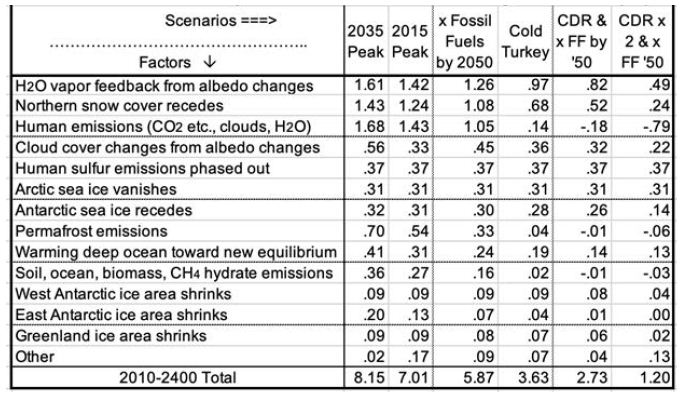

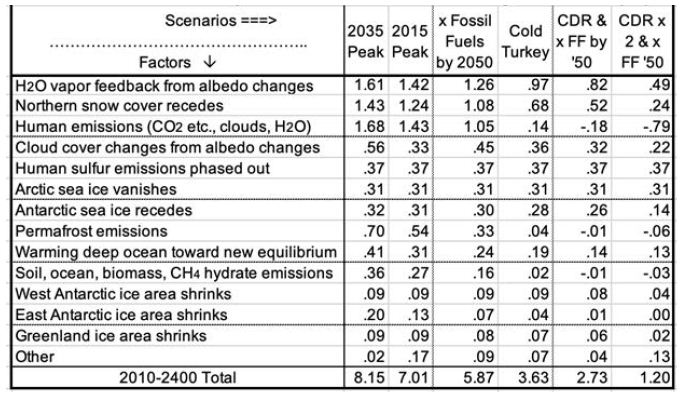

Table 5 summarizes estimated temperatures effects of 16 factors in the 6 scenarios to 2400. Peaking emissions now instead of in 2035 can keep eventual warming 1.1°C lower. Phasing out fossil fuels by 2050 gains another 1.2°C relatively cooler. Ending fossil fuel use immediately gains another 2.2°C. Also removing 2/3 of CO2 emissions to date gains another 2.4°C relatively cooler. Eventual warming in the higher emissions scenarios is a good bit lower than what would be inferred by using the 8.2°C climate sensitivity based on an epoch rich in ice and snow. This is because the albedo portion of that climate sensitivity (currently 6.4°) is greatly reduced as ice and snow disappear. More human carbon emissions (the first three scenarios especially) warm GSTs further, especially from less snow and cloud cover, more water vapor, and more natural carbon emissions. These in turn accelerate ice loss. All further amplify warming.

Table 5: Factors in Projected Global Surface Warming, 2010-2400 (°C).

Carbon release from permafrost and other reservoirs is lower in scenarios where GSTs do not rise as much. GSTs grow to the end of the study period, 2400, except for the CDR cases. Over 99% of warming after 2100 is due to amplifying feedbacks from human emissions during 1750-2100. These feedbacks amount to 1.5 to 5°C after 2100, in the scenarios without CDR. Projected mean warming rates with continued human emissions are similar to current rates of 2.5°C per century over 2000-2020 [2]. Over the 21st century, they range from 62 to 127% of the rate over the most recent 20 years. The mean across the 6 scenarios is 100%, higher in the 3 warmest scenarios. Warming slows in later centuries. The key to peak warming rates is disappearing northern sea ice and human SO4, mostly by 2050. Peak warming rates per decade in all 6 scenarios occur this century. They are fastest not for the 2035 Peak scenario (0.38°C), but for Cold Turkey (.80°C when our SO2 emissions stop suddenly) and xFF2050 (0.48°C, as SO2 emissions phase out by 2050). Due to SO4 changes, peak warming in the x FF 2050 scenario, from 2030 to 2060, is 80% faster than over the past 20 years, while for the 2035 Peak, it is only 40% faster. Projected SLR from ocean thermal expansion (OTE) by 2400 ranges from 3.9 meters in the 2035 Peak scenario to 1.5 meters in the xFF’50 2xCDR case. The maximum rate of projected SLR by 2400 is 15 meters from 2300 to 2400, in the 2035 Peak scenario. That is 5 times the peak 8-century rate 14 kya. However, the mean SLR rate over 2010-2400 is less than the historical 3 meters per century (from 14 kya) in the CDR scenarios and barely faster for Cold Turkey. The rate of SLR peaks from 2130 to 2360 for the 4 scenarios without CDR. In the two CDR scenarios, projected SLR comes mostly from the GIS, OTE, and the WAIS. But the EAIS is the biggest contributor in the three fastest warming scenarios.

Perspectives

The results show that the GST is far from equilibrium; barely more than 20% of 5.12°C warming to equilibrium. However, the feedback processes that warm Earth’s climate to equilibrium will be mostly complete by 2400. Some snow melting will continue. So will melting more East Antarctic and (in some scenarios) Greenland ice, natural carbon emissions, cloud cover and water vapor feedbacks, plus warming the deep ocean. But all of these are tapering off by 2400 in all scenarios. Two benchmarks are useful to consider: 2°C and 5°C above 1880 levels. The 2015 Paris climate pact’s target is for GST warming not to exceed 2°C. However, projected GST warming exceeds 2°C by 2047 in all six scenarios. Focus on GLSTs recognizes that people live on land. Projected GLST warming exceeds 2°C by 2033 in all six scenarios. 5° is the greatest warming specifically considered in Britain’s Stern Review in 2006 [59]. For just 4°, Stern suggested a 15-35% drop in crop yields in Africa, while parts of Australia cease agriculture altogether [59]. Rind et al. projected that the major U.S. crop yields would fall 30% with 4.2°C warming and 50% with 4.5°C warming [60]. According to Stern, 5° warming would disrupt marine ecosystems, while more than 5° would lead to major disruption and large-scale population movements that could be catastrophic [59]. Projected GLST warming passes 5°C in 2117, 2131, and 2153 for the three warmest scenarios. But it never does in the other three. With 5° GLST warming, Kansas, until recently the “breadbasket of the world”, would become as hot in summer as Las Vegas is now. Most of the U.S. warms faster than Earth’s land surface in general [32]. Parts of the U.S. Southeast, including most of Georgia, become that hot, but much more humid. Effects would be similar elsewhere.

Discussion

Climate models need to account for all these factors and their interactions. They should also reproduce conditions for previous eras when Earth had this much CO2 in the air, using current levels of CO2 and other GHGs. This study may underestimate warming due to permafrost and other natural emissions. It may also overestimate how fast seas will rise in a much warmer world. Ice grounded below sea level (by area, ~2/3 of the WAIS, 2/5 of the EAIS, and 1/6 of the GIS) can melt quickly (decades to centuries). But other ice can take many centuries or millennia to melt. Continued research is needed, including separate treatment of ice grounded below sea level or not. This study’s simplifying assumptions, that lump other GHGs with CO2 and other natural carbon emissions proportionately with permafrost, could be improved with modeling for the individual factors lumped here. More research is needed to better quantify the 12 factors modeled (Table 5) and the four modeled only as a multiplier (line 10 in Table 5). For example, producing a better estimate for snow cover, similar to Hudson’s for Arctic sea ice, would be useful. So would other projections, besides MacDougall’s, of permafrost emissions to 2400. More work on other natural emissions and the albedo effects of clouds with warming would be useful.

This analysis demonstrates that reducing CO2 emissions rapidly to zero will be woefully insufficient to keep GST less than 2°C above 1750 or 1880 levels. Policies and decisions which assume that merely ending emissions will be enough will be too little, too late: catastrophic. Lag effects, mostly from albedo changes, will dominate future warming for centuries. Absent CDR, civilization degrades, as food supplies fall steeply and human population shrinks dramatically. More emissions, absent CDR, will lead to the collapse of civilization and shrink population still more, even to a small remnant.

Earth’s remaining carbon budget to hold warming to 2°C requires removing more than 70% of our CO2 emissions to date, any future emissions, and all our CH4 emissions. Removing tens of GT of CO2 per year will be required to return GST warming to 2°C or less. CDR must be scaled up rapidly, while CO2 emissions are rapidly reduced to almost zero, to achieve negative net emissions before 2050. CDR should continue strong thereafter.

The leading economists in the USA and the world say that the most efficient policy to cut CO2 emissions is to enact a worldwide price on them [61]. It should start at a modest fraction of damages, but rise briskly for years thereafter, to the rising marginal damage rate. Carbon fee and dividend would gain political support and protect low-income people. Restoring GST to 0° to 0.5°C above 1880 levels calls for creativity and dedication to CDR. Restoring the healthy climate on which civilization was built is a worthwhile goal. We, our parents and our grandparents enjoyed it. A CO2 removal price should be enacted, equal to the CO2 emission price. CDR might be paid for at first by a carbon tax, then later by a climate defense budget, as CO2 emissions wind down.

Over 1-4 decades of research and scaling up, CDR technology prices may drop far. Sale of products using waste CO2, such as concrete, may make the transition easier. CDR techniques are at various stages of development and prices. Climate Advisers provides one 2018 summary for eight CDR approaches, including for each: potential GT CO2 removed per year, mean US$/ton CO2, readiness, and co-benefits [62]. The commonest biological CDR method now is organic farming, in particular no-till and cover cropping. Others include several methods of fertilizing or farming the ocean; planting trees; biochar; fast-rotation grazing; and bioenergy with CO2 capture. Non-biological ones include direct air capture with CO2 storage underground in carbonate-poor rocks such as basalts. Another increases surface area of such rocks, by grinding them to gravel, or dust to spread from airplanes. They react with weak carbonic acid in rain. Another adds small carbonate-poor gravel to agricultural soil.

CH4 removal should be a priority, to quickly drive CH4 levels down to 1880 levels. With a half-life of roughly 7 years in Earth’s atmosphere, CH4 levels might be cut back that much in 30 years. It could happen by ending leaks from fossil fuel extraction and distribution, untapped landfills, cattle not fed Asparagopsis taxiformis, and flooding rice paddies. Solar radiation management (SRM) might play an important supporting role. Due to loss of Arctic sea ice and human SO4, even removing all human GHGs (scenario not shown) will likely not bring GLST back below 2°C by 2400. SRM could offset these two soonest major albedo changes in coming decades. The best known SRM techniques are (1) putting SO4 or calcites in the stratosphere and (2) refreezing the Arctic Ocean. Marine cloud brightening could play a role. SRM cannot substitute for ending our CO2 emissions or for vast CDR, both of them soon. We may need all three approaches working together.

In summary, the paleoclimate record shows that today’s CO2 level entails GST roughly 5.1°C warmer than 1880. Most of the increase from today’s GST will be due to amplification by albedo changes and other factors. Warming gets much worse with continued emissions. Amplifying feedbacks will add more GHGs to the air, even if we end our GHG emissions now. Further GHGs will warm Earth’s surface, oceans and air even more, in some cases much more. The impacts will be many, from steeply reduced crop yields (and widespread crop failures) and many places too hot to survive sometimes, to widespread civil wars, billions of refugees, and many meters of SLR. Decarbonization of civilization by 2050 is required, but far from enough. Massive CO2 removal is required as soon as possible, perhaps supplemented by decades of SRM, all enabled by a rising price on CO2.

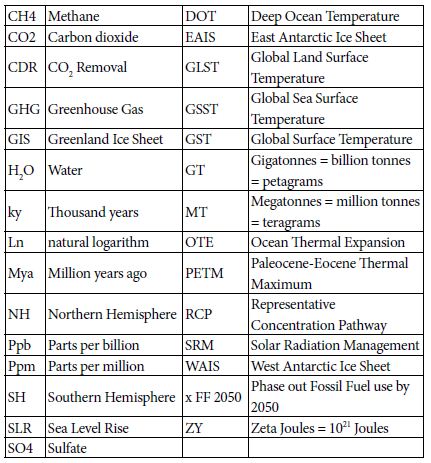

List of Acronyms

References

- https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/tabledata_v3/

- https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/tabledata_v3/GLB.Ts+dSST.txt

- Hansen J, Sato M (2011) Paleoclimate Implications for Human-Made Climate Change in Berger A, Mesinger F, Šijački D (eds.) Climate Change: Inferences from Paleoclimate and Regional Aspects. Springer, pp: 21-48.

- Levitus S, Antonov J, Boyer T (2005) Warming of the world ocean, 1955-2003. Geophysical Research Letters

- https://www.nodc.noaa.gov/OC5/3M_HEAT_CONTENT/

- https://www.eia.gov/totalenergy/data/monthly/pdf/sec1_3.pdf

- Hansen J, Sato M, Kharecha P, von Schuckmann K (2011) “Earth’s Energy imbalance and implications. Atmos Chem Phys 11: 13421-13449.

- https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/index.php?page=environment_how_ghg_affect_climate

- Tripati AK, Roberts CD, Eagle RA (2009) Coupling of CO2 and ice sheet stability over major climate transitions of the last 20 million years. Science 326: 1394-1397. [crossref]

- Shevenell AE, Kennett JP, Lea DW (2008) Middle Miocene ice sheet dynamics, deep-sea temperatures, and carbon cycling: a Southern Ocean perspective. Geochemistry Geophysics Geosystems 9:2.

- Csank AZ, Tripati AK, Patterson WP, Robert AE, Natalia R, et .al. (2011) Estimates of Arctic land surface temperatures during the early Pliocene from two novel proxies. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 344: 291-299.

- Pagani M, Liu Z, LaRiviere J, Ravelo AC (2009) High Earth-system climate sensitivity determined from Pliocene carbon dioxide concentrations, Nature Geoscience 3: 27-30.

- Wikipedia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greenland_ice_sheet

- Bamber JL, Riva REM, Vermeersen BLA, Le Brocq AM (2009) Reassessment of the potential sea-level rise from a collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. Science 324: 901-903.

- https://nsidc.org/cryosphere/glaciers/questions/located.html

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AntarcticBedrock.jpg

- DeConto RM, Pollard D (2016) Contribution of Antarctica to past and future se-level rise. Nature 531: 591-597.

- Cook C, van de TF, Williams T, Sidney RH, Masao I, al. (2013) Dynamic behaviour of the East Antarctic ice sheet during Pliocene warmth, Nature Geoscience 6: 765-769.

- Vimeux F, Cuffey KM, Jouzel J (2002) New insights into Southern Hemisphere temperature changes from Vostok ice cores using deuterium excess correction. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 203: 829-843.

- Snyder WC (2016) Evolution of global temperature over the past two million years, Nature 538: 226-

- https://www.wri.org/blog/2013/11/carbon-dioxide-emissions-fossil-fuels-and-cement-reach-highest-point-human-history

- https://phys.org/news/2012-03-weathering-impacts-climate.html

- Smith SJ, Aardenne JV, Klimont Z, Andres RJ, Volke A, al. (2011). Anthropogenic Sulfur Dioxide Emissions: 1850-2005. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 11: 1101-1116.

- Figure SPM-2 in S Solomon, D Qin, M Manning, Z Chen, M. Marquis, et al. (eds.) IPCC, 2007: Summary for Policymakers. in Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the 4th Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, USA.

- ncdc.noaa.gov/snow-and-ice/extent/snow-cover/nhland/0

- https://nsidc.org/cryosphere/sotc/snow_extent.html

- ftp://sidads.colorado.edu/DATASETS/NOAA/G02135/

- Chen X, Liang S, Cao Y (2016) Satellite observed changes in the Northern Hemisphere snow cover phenology and the associated radiative forcing and feedback between 1982 and 2013. Environmental Research Letters 11:8.

- https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/global-maps/MOD10C1_M_SNOW

- Hudson SR (2011) Estimating the global radiative impact of the sea ice-albedo feedback in the Arctic. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 116:D16102.

- https://www.currentresults.com/Weather/Canada/Manitoba/Places/winnipeg-snowfall-totals-snow-accumulation-averages.php

- https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/tabledata_v3/ZonAnn.Ts+dSST.txt

- https://neven1.typepad.com/blog/2011/09/historical-minimum-in-sea-ice-extent.html

- https://14adebb0-a-62cb3a1a-s-sites.googlegroups.com/site/arctischepinguin/home/piomas/grf/piomas-trnd2.png?attachauth=ANoY7coh-6T1tmNEErTEfdcJqgESrR5tmNE9sRxBhXGTZ1icpSlI0vmsV8M5o-4p4r3dJ95oJYNtCrFXVyKPZLGbt6q0T2G4hXF7gs0ddRH88Pk7ljME4083tA6MVjT0Dg9qwt9WG6lxEXv6T7YAh3WkWPYKHSgyDAF-vkeDLrhFdAdXNjcFBedh3Qt69dw5TnN9uIKGQtivcKshBaL6sLfFaSMpt-2b5x0m2wxvAtEvlP5ar6Vnhj3dhlQc65ABhLsozxSVMM12&attredirects=1

- https://www.earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/SeaIce/page4.php

- Shepherd A, Ivins ER, Geruo A, Valentina RB, Mike JB, et al. (2012) A reconciled estimate of ice-sheet mass balance. Science 338: 1183-1189.

- Shepherd A, Ivins E, Rignot E, Ben Smith (2018) Mass balance of the Antarctic Ice Sheet from 1992 to 2017. Nature 558: 219-222.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greenland_ice_sheet

- Robinson A, Calov R, Ganopolski A (2012) Multistability and critical thresholds of the Greenland ice sheet. Nature Climate Change 2: 429-431.

- https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/CloudsInBalance

- Figures TS-6 and TS-7 in TF Stocker, D Qin, GK Plattner, M Tignor, SK Allen, J Boschung, et al. (eds.). IPCC, 2013: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA.

- Zelinka MD, Zhou C, Klein SA (2016) Insights from a refined decomposition of cloud feedbacks. Geophysical Research Letters 43: 9259-9269.

- Wadhams P (2016) A Farewell to Ice, Penguin / Random House, UK.

- https://scripps.ucsd.edu/programs/keelingcurve/wp-content/plugins/sio-bluemoon/graphs/mlo_full_record.png

- Fretwell P, Pritchard HD, Vaughan DG, Bamber JL, Barrand NE et al. (2013) Bedmap2: improved ice bed, surface and thickness datasets for Antarctica .The Cryosphere 7: 375-393.

- Fairbanks RG (1989) A 17,000 year glacio-eustatic sea- level record: Influence of glacial melting rates on the Younger Dryas event and deep-ocean circulation. Nature 342: 637-642.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sea_level_rise#/media/File:Post-Glacial_Sea_Level.png

- Zelinka MD, Myers TA, McCoy DT, Stephen PC, Peter MC, al. (2020) Causes of Higher Climate Sensitivity in CMIP6 Models. Geophysical Research Letters 47.

- https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/4073/panama-isthmus-that-changed-the-world

- https://sunearthday.nasa.gov/2007/locations/ttt_cradlegrave.php

- Hugelius G, Strauss J, Zubrzycki S, Harden JW, Schuur EAG, et al. (2014) Improved estimates show large circumpolar stocks of permafrost carbon while quantifying substantial uncertainty ranges and identifying remaining data gaps. Biogeosciences Discuss 11: 4771-4822.

- DeConto RM, Galeotti S, Pagani M, Tracy D, Schaefer K, al. (2012) Past extreme warming events linked to massive carbon release from thawing permafro.st Nature 484: 87-92.

- Figure SPM-2 in IPCC 2007: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis.

- Figure 22.5 in Chapter 22 (F.S. Chapin III and S. F. Trainor, lead convening authors) of draft 3rd National Climate Assessment: Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States. Jan 12, 2013.

- Dorrepaal E, Toet S, van Logtestijn RSP, Swart E, van der Weg, MJ, et al. (2009) Carbon respiration from subsurface peat accelerated by climate warming in the subarctic. Nature 460: 616-619.

- MacDougall AH, Avis CA, Weaver AJ (2012) Significant contribution to climate warming from the permafrost carbon feedback. Nature Geoscience 5:719-721.

- Shakhova N, Semiletov I, Leifer I, Valentin S, Anatoly S, et al. (2014) Ebullition and storm-induced methane release from the East Siberian Arctic Shelf. Nature Geoscience 7: 64-70.

- Sandeman J, Hengl T, Fiske GJ (2018) Soil carbon debt of 12,000 years of human land use PNAS 114:36, 9575-9580, with correction in 115:7.

- Stern N (2007) The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge UK.

- Rind D, Goldberg R, Hansen J, Rosenzweig C, Ruedy R (1990) Potential evapotranspiration and the likelihood of future droughts. Journal of Geophysical Research. 95: 9983-10004.

- https://www.wsj.com/articles/economists-statement-on-carbon-dividends-11547682910

- www.climateadvisers.com/creating-negative-emissions-the-role-of-natural-and-technological-carbon-dioxide-removal-strategies/