DOI: 10.31038/AFS.2020223

Abstract

Amino acids (AAs) and proteins are major macronutrients in feedstuffs and fish. Due to a paucity of information about tissue-specific AA nutrition in aquatic animals, this review highlights the important energetic roles and functions of AAs (particularly glutamate, glutamine, and aspartate) in some tissues (particularly skeletal muscle, liver, kidney, and intestine) of fed fish. Although AAs have long been known to provide most of the energy utilized by fish, roles of specific AAs in certain tissues are unknown. Recent studies with hybrid striped bass and largemouth bass indicated that glutamate, glutamine and aspartate are major metabolic fuels in the proximal intestine, liver, kidney and skeletal muscle. Although these amino acids are abundant in both plant- and animal-source feedstuffs, their provision in compound feeds may be inadequate for optimum intestinal health or optimum growth performance of fish. Dietary supplementation with of glutamate, glutamine and aspartate may be crucial for the health of the organs and the whole body of fish, particularly under stress conditions. Knowledge of AA nutrition in fish will help to improve the growth, development and health of fish, as well as the efficiency of aquaculture worldwide.

Keywords

Amino acids, Energetic source, Protein metabolism, Fish tissues

Introduction

Amino acids (AAs) are indispensable nitrogen sources for living animals and, therefore, are a topic of utmost interest in the field of animal nutrition. In general, AAs can be grouped according to the chemical nature of their side chains, transport affinities, role in animal nutrition, or the catabolic fate of their carbon skeletons [1]. For instance, leucine, isoleucine, and valine are referred to as branched-chain AAs (BCAAs), whereas tryptophan, phenylalanine, and tyrosine are categorized as aromatic AAs. Other common groups include sulfur AAs, such as methionine and cysteine, and excitatory AAs, such as glutamate and aspartate. AAs are indispensable for protein biosynthesis and serve as the precursors of special products such as nitric oxide, polyamines, catecholamines, porphyrins, creatine, and melanin [1,2].

The first studies demonstrating the importance of AAs as an energy source for fish were performed about 50 years ago. Although several reasons have been proposed to explain the high fish requirements for dietary protein, it seems very important to focus on what has been done so far to understand this “apparent high” requirement and the greater contribution of dietary proteins for energy purposes [3,4]. From the comparison of protein efficiency ratios in a number of farmed animals, it could be observed that fish and terrestrial animals differ only in the relative dietary protein concentration required to achieve maximum growth rate. Previous studies highlight minimal or inexistent differences in protein requirements [5,6]. However, dietary protein contributes not only to body growth via protein synthesis, but a regular intake of proteins or AAs is required because fish continually use these biomolecules to replace existing proteins for tissue maintenance and to build new proteins during growth and reproduction [2].

At present, there is a paucity of information about the mechanisms for AA utilization in the energetic metabolism. Usually, animals have many different cell types and this diversity is matched by a complex system of AA transporters that operate on basis of substrate specificity and ion requirements [7]. Furthermore, the fish body has a common pool of total AAs, which is divided into the intracellular pool and extracellular pool. The intracellular pool is organ- and cell-specific [1]. Furthermore, intracellular pools of different organs are linked to the extracellular pool through the circulatory system. The AA composition of the intracellular pool is strongly influenced by the cell enzymes and the manner in which AAs are transported across the cell membrane. The same factors also control the AA distribution among different cellular compartments, such as the cytosol and mitochondria [8]. Moreover, the free AA pool composition within fish body also depends on other factors, such as starvation, acclimatization, absorption time, and food protein composition [3].

In nature, feed deprivation is a typical condition for fish because of recurring seasonal fluctuations, such as reproductive conditions or the availability of prey [9]. Fish have the ability to survive under fasting conditions for short or long periods without serious detrimental physiological effects. Starvation may provide insights on nutrients mobilization without the confusing interferences that exist when monitoring feed ingestion and digestibility. Additionally, it may be possible to estimate how the lipids and proteins inside the fish body may be utilized to survive as part of starvation metabolism [10]. Besides the requirements for protein biosynthesis, AAs are deaminated, and their carbon skeletons are oxidized to CO2 and water via the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and, in some cases, converted to fat or glucose and glycogen. In fish, AAs are quantitatively more important energy substrates than glucose and lipids are [11].

The literature on AA metabolism in fish tissues is relatively scarce and this topic has not been systematically compiled under an integrative view. In this review, the metabolism of AAs in different fish tissues is discussed with special focus on their use as energy sources.

Amino Acids in Fish Metabolism

Key Metabolic Pathways

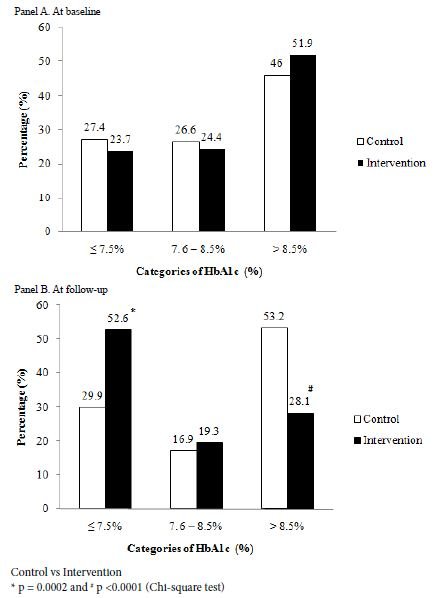

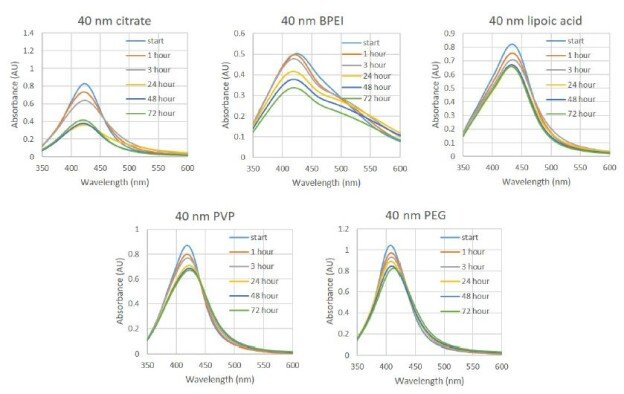

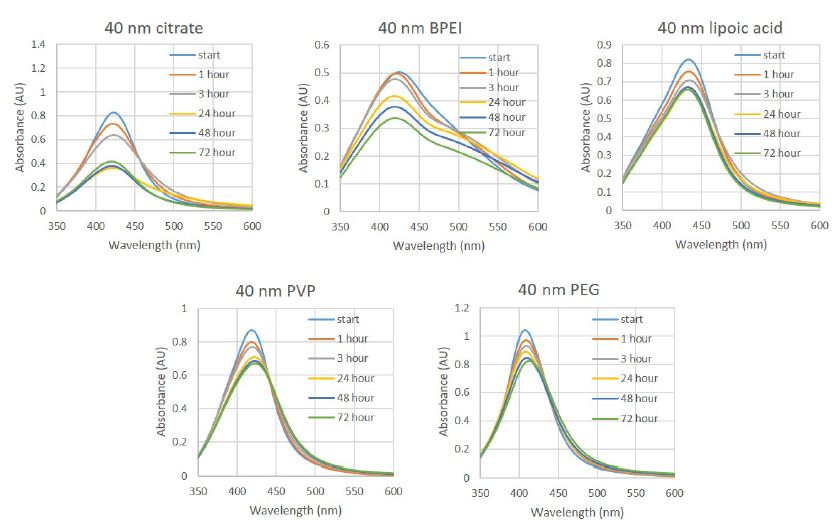

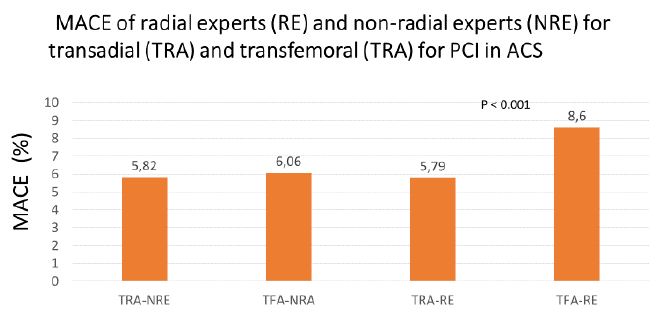

The degradation of AAs occurs via multiple pathways, including deamination and oxidation of carbon skeletons to CO2 through the TCA cycle [1,11]. Precursor substrates for gluconeogenesis include lactate and pyruvate, as well as glucogenic AAs derived from dietary protein. Since most of lactate and pyruvate are formed from glycolysis, the conversion of these metabolites into glucose via gluconeogenesis constitutes the glucose-lactate cycle. In contrast, gluconeogenesis from dietary AAs results in the formation of ammonia and represents a net transfer of carbons from proteins to carbohydrates. In herbivorous and omnivorous mammals, the recycling of glucose carbons accounts for a significant fraction of gluconeogenesis, particularly under fasting conditions [12,13]. AAs yielding acetyl-CoA or acetoacetyl-CoA are classified as ketogenic, since these two compounds are the precursors of ketone bodies. Some AAs are both ketogenic and glucogenic (Figure 1), while only leucine and lysine are exclusively ketogenic AA [14].

Figure 1: Classification of amino acids according to the metabolism of carbon skeletons. (A) Classification of amino acids as exclusively glucogenic, both glucogenic and ketogenic, or exclusively ketogenic. (B) Disposal of carbon skeletons as a part of the central pathways of energy metabolism.

The first enzymes to initiate AA catabolism are generally specific for a given AA or a group of structurally similar AAs (e.g., BCAAs). The general reaction types include oxidative deamination, transamination, and non-oxidative decarboxylation. Oxidative deamination is carried out by AA oxidases and dehydrogenases. D-amino acid oxidase (EC 1.4.3.3) has been detected in a variety of salmonid tissues [15] and in the common carp (Cyprinus carpio) as well [16]. Active aminotransferases for ammonia removal from specific AAs have been described in several fish tissues of salmonids [17] and Jian carp [18]. Quantitatively, the most important transaminases are aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT), also known as glutamate-oxaloacetate transaminase (GOT) and glutamate-pyruvate transaminase (GPT), respectively. Several studies were carried out detecting these enzymatic activities in the fish blood serum and tissues. A variety of AAs act as donors for deamination reactions in fish, which use AAs as the main substrates for gluconeogenesis in their bodies, as well as main oxidative fuels [1,2]. Moreover, AAs may also undergo reactions brought on by oxidases and decarboxylases with significant physiological and nutritional consequences. Among the possible decarboxylation reactions is the conversion of glutamate into γ-aminobutyrate (GABA, a neurotransmitter), ornithine into putrescine, and arginine into agmatine [14]. The physiological significance of AA decarboxylation in fish merits systemic research.

Energy Metabolism

It has been suggested that about 50 to 70% of calories (as-fed basis) in diets consumed by trout are provided by protein, reaching about 55 to 75% on a dry-weight basis [19]. Fish consume protein to obtain AAs, which are taken up by their cells in accordance with their needs for energy or protein synthesis. The dietary protein requirements of fish ranges from 30% to 60%, depending on species, age, size, and feeding habits [2,20]. These quantities are greater than the amounts required for mammals and birds, such as swine (12-20%), dairy cows (10-18%), and chickens (14-22%) [3,21,22].

As animals get their energy needs from oxidation of the complex molecules that they eat, the energy in feed is not available until the complex molecules are broken down to simpler molecules by digestion. Furthermore, the energy needs of fish are mainly supplied by macromolecules as fats, carbohydrates, and proteins. There is little consistent information on the ability of fish to digest fats of different melting points, although fats are generally well digested and utilized by fish, providing about 8.5 kcal metabolizable energy (ME) per gram [23]. The ME values of carbohydrates for fish range from near zero for cellulose to about 3.8 kcal/g for easily digestible sugars. The value of carbohydrates in fish feeds is a controversial issue. It appears, however, that digestible carbohydrates can be well utilized as an energy source if they are provided in proper balance with other nutrients [24]. Protein has a ME value of about 4.5 kcal/g for fish, which is higher than that defined for mammals and birds [23]. Thus, it seems clear that most fish do not use carbohydrates (e.g., starch, glycogen, and simple sugars) as a major energy source [25].

Moreover, the energy metabolism in fish could be compared as similar to mammals and birds with two notable exceptions: (a) fish do not expend energy to maintain a body temperature different from that of the environment and (b) the excretion of waste nitrogen requires less energy in fish than it does in homeothermic land animals [26]. Although AAs have long been known to provide most of the energy utilized by fish, the role of specific AAs in certain tissues are unknown. Recent studies with hybrid striped bass and largemouth bass indicated that glutamate, glutamine and aspartate are major metabolic fuels in the proximal intestine, liver, kidney and skeletal muscle [11,27]. Note that these amino acids are abundant in both plant- and animal-source feedstuffs [22,28,29], but their provision in compound feeds may be inadequate for optimum intestinal health or optimum growth performance of fish [30]. Hence, the whole protein content does not vary too much among different species, and the AA profiles within the fish body is similar to that of the aforementioned animals [31,32]. However, species-specific composition in eye tissues from zebrafish (Danio rerio) and sardine (Sardina pilchardus) have been described [33].

The contribution of proteins and AAs towards meeting the energy requirements of fish is highly considered, because of the concept of “protein-sparing” through optimization of the digestible protein (DP) to digestible energy (DE) ratio addressed in a large number of species [34,35]. Moreover, the lack of control of amino acid catabolism as affected by dietary protein levels was considered as a major reason for the high protein requirements in fish [25]. As most of the fish are carnivorous, the use of protein as energy source could be compared with carnivorous mammals. Such comparison with terrestrial animals suggested that teleost fish or even shrimp use a greater proportion of proteins for energy purposes despite lower overall energy requirements due to the aquatic mode of life, which includes poikilothermy and ammoniotelism [6].

The basal energy needs of fish are lower than those of terrestrial animals due to their poikilothermic character, in which the internal temperature varies considerably according to environmental conditions. Therefore, dietary protein contributes not only to fish growth by providing AAs for protein synthesis, but also ATP production via AA catabolism. Evidence from several studies suggests that proteins and lipids are the major sources of energy for fish [36-38]. The final product of protein metabolism in teleost fish is ammonia, rather than urea and uric acid in mammals and birds, respectively. Because the synthesis of urea and uric acid requires a large amount of energy, the release of ammonia is energetically advantageous for fish [39]. Thus, the efficiency of AAs as metabolic fuels is greater in fish than in mammals and birds. High rates of AA utilization for body growth have been observed in fish as compared with other animals [8,40]. These quantitative differences have been attributed to the carnivorous/omnivorous feeding habit of fishes and their apparent preferential use of protein over carbohydrate as a dietary energy source [41].

Some cells in the nervous system can use diverse substrates, including AAs, to support oxidative energy metabolism [42]. At the same time, AA oxidation may contribute from 50 to 70% of total energy needs in marine fish embryos and yolk-sac larvae [25,43]. Indeed, it has been suggested that AAs could provide 14 to 85% of the energy requirements for teleost fish, depending on their developmental stage [44]. Energy supply is a limiting factor for physiological processes, and therefore, the study of energy metabolism associated to such processes is key to improve the growth, development and health of fish. Metabolic reorganization and alterations in intermediary metabolic pathways occur in fish to meet their increased energy demands for adaptations to changes in the aquatic environments.

Amino Acids Mobilization in Different Fish Tissues

AAs distribution and their respective concentrations into the various fish organs and tissues depend on their physiological roles (Table 1). Relatively little is known about AA metabolism in specific fish tissues. Mobilization of glycogen and lipids, as well as protein (primarily in skeletal muscle) contributes to ATP production [63,64]. Some species try to preserve liver glycogen stores by degrading proteins to support gluconeogenesis and use lipids and/or proteins as energy substrates [45,50]. In general, fish produces glycogen through gluconeogenesis during long periods of starvation, representing an energy source for muscle tissue and mobilizing it to maintain homoeostasis during the first stages of starvation [64-66]. On the other hand, an alternative pathway for de novo glucose synthesis can be through gluconeogenesis from lactate, glycerol and some AAs [67]. Fish uses AAs as the main substrates for gluconeogenesis and as main oxidative fuel. This is especially true for migratory fish, which may go for long periods without eating [68]. However, after fasting time the fish could eventually necessitate of protein catabolism to replenish glycogen stores that were exhausted during extensive starvation [49,50,67]. The anadromous Arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus) seems to find energy from protein stores into muscle tissues during the latter part of overwintering, or during migration growth and adiposity. This conclusion is supported by the reduction in muscular body mass observed during food-deprived fish from May through June [69]. Typically, fish return to standard metabolism depending on available feed after the fasting period, although this also depends on the environmental conditions, species, and age of the animal [70].

Table 1: Major roles of amino acids in fish tissues.

|

Tissues

|

Amino acids |

Physiological and/or metabolic role |

References

|

|

Liver

|

Met |

The main role of Met is the synthesis of taurine (for bile production) |

[14,45,46] |

| Val and Ile |

Val and Ile are used as glucogenic amino acids

|

|

Leu

|

Leu could be metabolized to ketone bodies, providing energy for tissues such as brain and heart during starvation |

[14]

|

|

Ala

|

Ala is used as substrate for glycogen and/or glucose production in liver |

[47-50]

|

|

Met, Leu and Lys

|

In hepatocytes, Met, Leu and Lys could regulate glycolysis, gluconeogenesis and lipogenesis; particularly relevant their involvement in regulation of metabolism related gene expression |

[51,52]

|

|

Blood system

|

Ala, Gln, and Arg |

Concentrations of Ala, Gln, and Arg in plasma may be increased during long-term starvation for gluconeogenesis |

[36]

|

|

Gln,Arg and Orn

|

Gln, Arg and Orn contribute to remove ammonia from blood during food deprivation |

[53-55]

|

|

Nervous system

|

Glu

|

The main role of Glu is to provide energy for the enterocytes and precursors of biologically molecules like glutathione

|

[56-59]

|

|

Gly

|

Inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system; co-agonist with glutamate for N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor receptors; antioxidant; anti-inflammation; one-carbon metabolism; conjugation with bile acids

|

|

Muscle

|

Ala, Asp, Glu and leu

|

Ala and Asp serve as glucogenic precursors during the rest time. Moreover Ala concentration in muscle is increased to support muscular activity Leu is oxidized during food deprivation in fish to produce ATP for swimming

|

[40,60,61]

|

|

Gut

|

Glu and Gln

|

Glu and Gln are major energy source, and used for glutathione synthesis. They play a crucial role intestinal health of fish, by modulating intestinal structure, protecting against oxidative damage and acting as energy substrate for the enterocytes.

|

[11,59]

|

|

Arg

|

Arg has a role to improve intestinal health. Increased activity of several intestinal enzymes and changed composition of the intestinal microbiota

|

[62]

|

The low glucose turnover rate reported in fish as compared to other animals (mammals and birds) is in agreement with the fact that proteins play a large role in ATP production in most ectothermic fish [67,71,72]. This is supported by the lower nitrogen retention in ectothermic fish such as carp (30%) feeding diets with increased carbohydrate content, as compared with homeotherms like pigs (45%) and chickens (50%) [39]. AAs are not only oxidized for ATP production, but they are also used to synthesize macromolecules such as proteins in the gills or other organs, and for the osmoregulation during fish seawater acclimation [73]. Osmotic pressures in teleost fish are regulated at nearly constant levels. The non-essential AAs seem to be preferentially used for osmoregulatory proposes, rather than the ten AAs considered essential for the fish, namely arginine, histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine [2]. However, the role of AAs as oxidative substrates in specific tissues has been largely neglected in previous studies that examined the effects of environmental salinity on the AA composition of fish plasma and tissues [74]. Some specific aspects of AA metabolism in different fish tissues are discussed in the following sections.

Blood System

Changes in the plasma levels of AAs at various time intervals after feeding have been monitored for several species, including rainbow trout [75], carp [76], tilapia [77], and channel catfish [78]. The enzyme glutamate dehydrogenase showed moderate activities in rainbow trout and carp erythrocytes, where glutamine was more important than glucose as an oxidative substrate [79]. Glutamate is used for the synthesis of glutamine and glutathione. Glutamine is essential for the synthesis of purines and pyrimidines, whereas glutathione protects cells from oxidative stress [1].

The metabolic reactions in the liver greatly affect the concentration of most AAs in blood and gut. Liver monitors the absorbed dietary AAs arriving from the portal blood and has the important role of controlling their catabolism and release into the general circulation. Much of the AAs taken up by the liver are rapidly degraded [80]. A rapid catabolism of excess dietary AAs was observed in rainbow trout by measuring a large increase in ammonia excretions within four hours of feeding a high protein meal [81]. In the case of BCAAs, skeletal muscles may be more important for initiating BCAA degradation than the liver [71,82].

During feed deprivation, fish appears to use catabolic energy conservation strategies to meet caloric needs while minimizing tissue energy loss [83]. It has been suggested that white muscle proteolysis is the source for increased plasma levels of free AAs observed during long-term feed deprivation, normally constituting the primary source of energy in carnivorous species [54]. Furthermore, AAs can supply glucose during periods of prolonged starvation via gluconeogenesis. In several fish species, long-term starvation mobilizes muscle protein by increasing the levels of free AA, usually alanine and glutamine, the most released AAs [36,53]. The increases in plasma AAs augment their metabolic utilization [54] and this is apparently the case for most non-essential glucogenic AAs in teleost fish [84].

AAs release via proteolysis of white muscle has been identified as an important fuel source for sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) during periods of prolonged starvation [36]. However, the total plasma AAs in starved lake sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens) was found to be unchanged during 45 days of feed deprivation [45]. Moreover, starved brown trout (Salmo trutta) showed a significant increase in total plasma AA levels after 15 days of feed deprivation [85]. These different responses in different studies may reflect species-specific metabolic adaptation strategies in response to feed deprivation and/or differences in body energy stores, such as lipids and glycogen. In this regard, Solea senegalensis is characterized by low body lipid stores, which supports the importance of proteolysis during prolonged feed deprivation in this species [55]. The increased levels of plasma glutamine, ornithine, and arginine observed in ureotelic fish that had been feed-deprived for 21 days may facilitate detoxification of ammonia production after AA catabolism. Glutamine is formed from glutamate and ammonia, and this reaction is a cellular mechanism for ammonia detoxification in fish. However, for every mole of ammonia detoxified, two equivalent moles of ATP are hydrolyzed [86]. Higher plasma levels of serine, asparagine, glutamine, arginine, and ornithine were observed in fish (S. senegalensis) that had been feed-deprived for 21 days [87]. This may suggest their role as important sources of carbons for gluconeogenesis, which is in line with the high rates of 14C incorporation from 14C-labeled serine and asparagine into glucose in isolated hepatocytes from feed-deprived O. mykiss. In addition, glutamine, arginine, and ornithine can be metabolized to glutamate, and deamination of glutamate is a main pathway for its oxidation to CO2 or for gluconeogenesis in the fish liver [20].

Liver

Liver plays an essential role on controlling the mobilization of energetic reserves for survival during the starvation period. In the fed state, sulfur AAs are used for the synthesis of taurine, which is required for the production of bile salts to promote lipid digestion and absorption. However, under starvation conditions, methionine is not needed to produce bile salts and, therefore, might be used as a glucogenic AA to produce glucose as a possible energy source for the central nervous system and red blood cells [45,46]. Valine and isoleucine are glucogenic, being catabolized via the TCA cycle and utilized for gluconeogenesis (Figure 1). Moreover, glutamate and glutamine are oxidized extensively in the liver of zebrafish and hybrid striped bass, with the rate of CO2 production from glutamine being greater than that from glutamate [11], while catfish hepatocytes produce five times more ammonia from glutamine than from glutamate [88]. Ketogenic AAs are converted to acetyl-CoA or ketone bodies in order to provide energy for tissues such as the brain and heart during starvation [47,89]. The analysis of stable isotopes in different tissues has been widely used in ecological studies to learn about the nutrient transfer across ecosystem boundaries and to understand trophic relationships and the migration of animals (including fish) through dietary changes that occur throughout their lives [9].

The juvenile yellowtail amberjack (Seriola lalandi) was subjected to an isotopically equilibrated diet of δ13C and δ15N AAs and proteins for 60 days and after this period, two treatments were carried out [90]. For one treatment, the fish continued to be fed and those in the other group were deprived of feed. The compound-specific isotopic analysis (CSIA) of AAs from different tissues showed significant differences between the muscle and liver samples of the control group and those fed the test diet. The CSIA for the δ15N values of liver AAs revealed the largest changes relative to the diet for non-essential AAs, whereas glycine and lysine remained constant. However, methionine was the most enriched AA within the control group, as compared to test diet. Valine and isoleucine, both essential AAs, were highly enriched in the liver of starved fish, a condition arising from either a high rate of utilization or an insufficient dietary supply. Enrichment patterns were observed for alanine, aspartate, and glutamate [90].

Salmonid fish encounter periods of little or no feed intake for many reasons, such as low feed availability during winter conditions. The role of carbohydrates and proteins as energy sources during periods of short-term fasting (days to weeks) or long-term starvation (months) in different fish species is less clear [50,91,92]. In coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch), liver glycogen decreases one week after the initiation of fasting, but returns to a normal level after three additional weeks of feed deprivation. Net protein breakdown has been observed during prolonged periods of feed deprivation in salmonids, but not during the initial phase [50,91]. Juvenile salmonids are potentially more sensitive to fasting than adult fish, although there are still similarities between the different life stages in protein metabolism during fasting [93]. Alanine is likely used as a substrate for glycogen and/or glucose production in the liver [48,50], but may also be oxidized in the liver and used as a direct energy source [49]. In this scenario, decreased levels of alanine in the liver of fasted fish have been demonstrated [93].

Some genetic parameters have been considered in experiments involving food-deprived and well-fed amberjack fish, in particular changes in liver leptin (LepA1 and LepA2) expression [90]. An increase in liver leptin expression was previously observed during fasting/feed restriction, similar to the increase reported in Atlantic salmon [94,95]. The activity of enzymes involved in lipid metabolism (glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase and 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase) and glycolysis (pyruvate kinase) appeared inversely correlated to liver leptin expression in food-deprived fish. The highest activity of these enzymes was recorded concurrently with low liver leptin expression in well-fed fish. Moreover, such interrelationships were not observed for enzymes involved in AA metabolism and gluconeogenesis [69]. Liver metabolic responses to increased dietary carbohydrates in both carnivorous fish and tilapia were also investigated as an attempt to understand the reasons for the higher metabolic use of carbohydrates in omnivorous fish than in carnivorous fish [96,97]. Some studies demonstrated that the liver of omnivorous fish responds well at the metabolic level to dietary carbohydrates, similarly to previous reports on juvenile tilapia and hybrid tilapia [98,99].

Biochemical responses to dietary nutrients in tilapia liver were previously investigated [100-102]. Gene expression studies showed no regulation at mRNA levels for metabolic enzymes related to glycolysis and gluconeogenesis, whereas mRNA levels for hepatic enzymes involved in AA catabolism were clearly dependent on the amount of dietary protein intake. This was not an expected result, as increased lipogenic and decreased gluconeogenic enzyme activities were observed in tilapia feeding carbohydrate-rich diets [103]. This indicates that enzymes in tilapia liver did not respond to dietary carbohydrates at the transcriptional level. Although the first steps of glucose utilization via the hepatic glucokinase (gck gene) were clearly higher in fish fed higher carbohydrate diets, the long-term adaptation of tilapia to carbohydrates does not necessitate persistent molecular adaptation for glucose utilization within the liver of this fish. It is unknown how the liver of carnivorous fish respond to dietary carbohydrate intake.

Intestine

Although the intestine uses both Glu and Gln as energy sources, the supply of each molecule is different. Both dietary and arterial Gln content are recruited into intestinal cells, while almost all Glu utilized in the gut comes from the lumen [104]. Glu is a non-essential AA that universally exists in living organisms. It plays various roles in enterocytes metabolism and physiology, either directly, as an energy source [56] or excitatory neurotransmitter in the enteric nervous system [105], or through conversion into bioactive molecules, such as glutathione [58]. Glu serving as a substrate for the synthesis of glutathione by the intestinal mucosa is derived from enteral Glu rather than arterial Glu, and 95% of dietary Glu is metabolized as a major energy source by the intestinal cells of piglets [59]. Although Glu can be synthesized in the body, this metabolic pathway is inadequate to meet the requirement of the piglet small intestine for glutamate [106]. These studies indicate that the utilization of dietary Glu has an important role in gut health and systemic metabolism. Examining this role may be helpful to better understand AA metabolism in the intestines of fish.

Moreover, after protein hydrolysis in the gut, the AAs are absorbed and pass along the portal system to the liver. During their passage across the intestinal wall, AAs can be incorporated into intestinal proteins (constitutive or secretory) or catabolized by the tissue [68]. The gut itself can metabolize extensive amounts of certain AAs, such as glutamate and aspartate. Indeed, in some animals, gut metabolism has a major influence on the whole body AA requirement [56].

Nervous System

Besides glucose, ketone bodies and possibly both lipids and proteins may act as energy sources in the brain of several vertebrates [107]. Astrocytes can use glutamine as an energy source and produce glutamine from glutamate (a neurotransmitter removed from the synaptic cleft), as well as from precursors, such as glucose and fatty acids [42]. The synthesis and utilization of substrates such as glutamine, ketone bodies and lactate are greatly influenced by their concentrations in the cells and the extracellular milieu [108,109]. The carbon skeletons of glutamate are mainly metabolized into CO2, lactate, or alanine, while the nitrogen of glutamate is utilized for the synthesis of other AAs such as glutamine, proline, and arginine [57,59,110]. Glutamine has various functions in cellular metabolism, such as serving as energy fuel and being a precursor for purine and pyrimidine nucleotides, NAD+, and amino sugars [57,58].

Muscular System

Proteins may play an important role in fueling muscle work in fish, but their exact contribution has yet to be established [111]. The design of reliable methods to measure substrate fluxes in fish muscle [112] has allowed researchers to start investigating how fish muscles respond to common environmental stresses. White muscle under stress is forced to produce lactate at higher rates than can be processed by aerobic tissues. However, lactate accumulation is minimized because disposal is also strongly stimulated. Trout have a much higher capacity to metabolize lactate under normoxic conditions than during hypoxia or intense swimming. The low density of monocarboxylate transporters and lack of up-regulation with exercise explain the phenomenon of lactate retention in white muscle. This tissue operates as an almost-closed system, where glycogen stores act as an “energy spring” that alternates between power release during swimming and slow withdrawal in situ from lactate during recovery [111].

To cope with exogenous glucose, trout can completely suppress hepatic production and boost glucose disposal. Without these responses, glycaemia would increase four times faster and reach dangerous levels. Therefore, the capacity of salmonids to regulate glucose levels is much better than presently described in the existing literature. However, knowledge about the use of proteins or AAs as fuel for muscle work in fish is still lacking. Glutamate and glutamine are major metabolic fuels for the skeletal muscles of zebrafish and hybrid striped bass [11]. This is contrast to mammalian muscles, where fatty acids and glucose are primary energy substrates [39].

Little is known about the use of proteins as fuel for muscular work in fish, although evidence from sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) shows that proteins become the dominant source of fuels towards the end of migration when all the other substrates reach depletion [36]. At this point, researches also reported changes in AA and protein concentrations, as well as the activities of related enzymes. AA fluxes have not been measured in exercising fish and the only direct measurement of protein catabolism during swimming was the rate of nitrogen excretion in juvenile trout with a high growth rate. However, the high growth rate may be a destabilizing factor since significant changes in the protein composition of fish tissues occur during this stage of growth. A study examined the roles of glutamate, alanine, and aspartate as gluconeogenic precursors in resting kelp bass [60], and a further research measured the fluxes of all AAs in resting rainbow trout [113]. It is unclear whether the high rates of protein catabolism observed in migrating salmon and juvenile trout are typical of active muscles or whether they only occur under exceptional circumstances of extreme exercise or rapid growth [114].

The intramuscular metabolism of ectotherms has receive little attention, but the design of reliable methods to measure substrate fluxes in fish has allowed researchers to start investigating how fish muscles respond to common stresses [112]. For example, the mudskipper (Periophthalmodon schlosseri) is quite active and levels of total free AAs increased significantly in skeletal muscle and plasma, while alanine levels increased three-fold in the muscle, four-fold in the liver, and two-fold in plasma [61]. From these results, the authors concluded that P. schlosseri was capable of partially catabolizing certain AAs to support activity on land because of its capacity for life on sea and land. The tolerance of P. schlosseri to environmental ammonia is much higher than any other fishes because of its capability to actively excrete NH4+ and its low skin permeability to NH4+, which prevents back diffusion [115]. In this context, the amino groups of these AAs are transferred directly or indirectly to pyruvate to form alanine. The carbon chains are fed into the TCA cycle and are partially oxidized to malate, which could replenish pyruvate through the function of the malic enzyme. This favorable ATP yield from partial AA catabolism is not accompanied by a net release of ammonia [114]. Mudskippers can be very active on land. Thus, urea formation, which is energetically expensive, may not be a suitable strategy. By exposing mudskippers to terrestrial conditions, in constant darkness to minimize physical activity, the researchers reduced the rate of proteolysis and AA catabolism in response to aerial exposure [116]. In contrast, increased concentrations of alanine, BCAAs, and total free AAs were observed in the tissues of P. schlosseri exposed to terrestrial conditions for 24 h [117].

Proteins are one of the primary sources of metabolic energy in carnivorous fishes. The main storage tissue of utilizable protein is white muscle. AAs released through proteolysis can be oxidized either as energy or converted to other utilizable forms via anabolic pathways, as noted previously [11,14]. Before AAs can be oxidized through the TCA cycle, the amino group must be removed by either transamination or deamination. Ammonia is not produced during transamination, but deamination produces either NH3, which spontaneously takes up H+ to form NH4+ [118]. Certain AAs (e.g. arginine, glutamine, histidine, and proline) can be converted to glutamate, which can undergo deamination by glutamate dehydrogenase, producing NH4+ and α-ketoglutarate. The latter is fed into the TCA cycle. Glutamate can also undergo transamination with pyruvate, catalyzed by alanine aminotransferase, producing α-ketoglutarate without releasing ammonia. Continuous glutamate-pyruvate transamination would facilitate the oxidation of the carbon chains of some AAs. Under normal circumstances, the carbon chain of an AA is completely oxidized to CO2 through the TCA cycle and the electron transport chain, thus producing ATP and/or its equivalent [119]. This would cause a reduction in the efficiency of ATP production because not all AAs would fully be oxidized, allowing certain AAs to be used as energy sources, while minimizing ammonia accumulation. In fish, alanine constitutes 20 to 30% of the total AA pool [119]. Most of the free AAs could be converted into alanine and the overall quantitative energetics would appear to be quite favorable. The net conversion of glutamate to alanine would yield 20 moles of ATP per mole of alanine formed if the resultant α-ketoglutarate is completely oxidized to CO2. This favorable ATP yield from AA catabolism is accompanied by a direct release of ammonia into the living environment.

Alanine is an important substrate for hepatic gluconeogenesis and is one of the main AAs released by the skeletal muscle [1]. It is also an important source of energy for fish. However, the effect of adding alanine into diets is controversial, as dietary alanine is largely extracted by the splanchnic bed. In addition, β-alanine supplementation does not affect the growth of Japanese flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) [120].

Skeletal muscle plays an important role in initiating BCAA degradation via transamination. There are reports that muscle tissues of goldfish [121] and trout [122] have higher activities of BCAA transaminases than mammalian muscles, which indicates a high capacity for leucine catabolism in fish muscle. In trout, the rate of leucine catabolism is higher during intense swimming than at rest [40]. The quantitative importance of leucine oxidation by fish muscle depends mainly on the use of protein as an endogenous energy source, since blood leucine does not contribute significantly to total CO2 production. This means that other substrates (e.g., glutamate, glutamine, alanine and aspartate) contribute predominantly to ATP production during exercise in fish. The oxidation of alanine occurs within the muscle, kidney and liver via glutamate-pyruvate transaminase. Alanine transport into the cells is under hormonal control during stressful conditions. Thereby, alanine is actively released at high rates by all muscle types studied, ensuring its supply to the liver and kidneys and this AA may be a major final product of muscle metabolism [40].

Important Amino Acids as Energy Sources

Lysine and Methionine

The effects of synthetic methionine and lysine on the growth and feed conversion of animals are so impressive that the use of these two AA as feed additives worldwide exceeds 700,000 metric tons annually [123,124]. Lys has a particular role in metabolism, since Lys and Leu are exclusively ketogenic AAs that are broken down to acetyl-CoA, which is oxidized to CO2 via in the TCA cycle. Unlike Lys, Met is a glucogenic AA that produces glucose as an energy source. Under methionine-limiting conditions, excesses of branched-chain AAs reduce methionine oxidation possibly due to competitive inhibition by the branched-chain ketoacids. Through the formation of S-adenosylmethionine (a donor of methyl group), methionine plays a key role in one-carbon metabolism [45,46].

Alanine

The transamination of non-essential AAs, such as alanine and aspartate, was found to be important for ATP production in fish in early investigations [71]. Alanine can stimulate the feeding response of certain fish [125] and carries nitrogen for inter-organ AA metabolism [36]. Recently, a study suggested a possible role for the hormones STC1 (a stanniocalcin homologue) and PTHrP (parathyroid hormone-relate protein) in teleost fish to safeguard liver glycogen reserves under stressful situations [126]. The strategy may involve the production of glucose via BCAA, alanine, glutamine, and glutamate and their mobilization from the muscle to the liver. Alanine is a fundamental AA that provides energy for the central nervous system during the starvation period by constant translocation from the muscle tissues through the blood system to the liver. However, under non-stressful conditions, the main energy source mainly comes from glutamate and glutamine [11].

Glycine

Glycine participates in gluconeogenesis, sulfur AA metabolism, one-carbon metabolism, and fat digestion [127]. It also stimulates feed intake in many fish [125]. In sturgeon, increased levels of glycine and a reduction of glucogenic AAs occur in response to feed deprivation. Glycine represents almost 30% of collagen, the major structural protein of connective tissues, such as tendons, skin, and ligaments [128]. Moreover, glycine might be reserved for the synthesis of creatine and, thus, the generation of creatine phosphate, a high-energy molecule used as an energy source for overcoming extreme conditions, like running away from predators [129]. In this regard, glycine plays an important role in energy metabolism during periods of feed deprivation and for activities requiring rapid use of high quantities of energy.

Arginine

Arginine is classified as an essential AA in young animals, including young fish, and is necessary for optimal growth [2]. Arginine plays various physiological roles in animal cells, such as serving as a component of proteins, an oxidative energy substrate, a stimulator of hormone secretion (e.g. growth hormone, insulin, glucagon), and a precursor of polyamine and nitric oxide (NO), which is vital for the vasodilation and immune responses [130]. In most mammals (e.g., humans, pigs and rat), the small intestine is the site for endogenous synthesis of citrulline and arginine from glutamine, glutamate and proline [21]. However, endogenous synthesis of arginine has not been demonstrated in most teleost fish [131]. In mammalian liver, arginine is essentially catabolized by arginase via the urea cycle [21]. The embryos of salmonids seem to have a functional urea cycle for ammonia detoxification, as researchers observed relatively higher activity of five urea cycle enzymes. This situation is quite different from adult fish. Arginase is ubiquitous in fish tissues, with the highest activity in the liver and kidney [132]. The dietary requirement for arginine among various fish species may differ because of differences in metabolic and enzymatic efficiency [131]. Previous growth studies suggested that the fish arginine requirement might range from 4 to 6% of dietary protein. Salmon have the highest requirement (about 6% of dietary protein), whereas this number ranges from 4 to 5% in other species [2]. Arginine is a nutritionally essential AA for fish not only as a precursor for protein synthesis, but also for its metabolic role in the production of diverse metabolites, including nitric oxide (NO), polyamines, urea, proline, and glutamate [130,133].

Conclusions

To improve the knowledge about the use of AAs as a major energy source in fish, it is important to understand the bioavailability of each dietary AA to be absorbed and retained. The estimated bioavailability of AAs could be indirectly determined by the digestibility of dietary proteins. However, in aquatic organisms, leaching of water-soluble nutrients from both feed and feces is always a factor contributing to inaccuracy when determining the amounts of available AAs that are actually absorbed. Apart from those AAs retained for anabolic processes (i.e. protein deposition during growth), there is also a need to determine the amounts required to meet the demands of metabolic processes. Therefore, the amounts of dietary AAs that enter the portal circulation cannot be determined precisely. It is important to distinguish those AAs used in metabolic processes (e.g., ATP production) from those retained by fish under starvation conditions. Clearly, more research is needed on the metabolism of AAs in swimming fish to solve this intriguing problem. Muscular performance depends critically on the adequate supply of metabolic fuels and disposal of final products. Therefore, knowing how metabolite fluxes are regulated is necessary to understand the strategies whereby fish survive, grow, and develop. The ATP used for contraction can be generated through various pathways of energy metabolism that catabolize carbohydrates, lipids, or proteins. It can be suggested that under both fed and food-deprived conditions, AAs are major metabolic fuels for the intestine, liver, skeletal muscle, kidneys, and possibly other tissues.

References

- Wu G (2013) Amino Acids: Biochemistry and Nutrition. Boca Raton.

- Wilson RP (2002) Amino acids and proteins. San Diego, CA: Elsevier 144-179.

- Kaushik SJ, Seiliez I (2010) Protein and amino acid nutrition and metabolism in fish: current knowledge and future needs. Aquac Res 41: 322-332.

- Kim JD, Lall SP (2000) Amino acid composition of wholebody tissue of Atlantic halibut (hippoglossus hippoglossus), yellowtail flounder (pleuronectes ferruginea) and Japanese flounder (paralichthys olivaceus). Aquaculture 187: 367-373.

- Bowen SH (1987) Dietary protein requirements of fishes – A reassessment. Can J Fisher Aquatic Sci 44: 1995-2001.

- Cowey CB (1994) Amino acid requirements of fish – a critical appraisal of present values. Aquaculture 124: 1-11.

- Matthews JC (2000) Amino acid and peptide transport systems. Wallingford, UK: CAB International 3-23.

- Jürss K, Bastrop R (1995) Amino acid metabolism in fish. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of Fishes 4: 159-189.

- Karasov WH, Martinez del Rio C (2007) Physiological Ecology: How Animals Process Energy, Nutrients, and Toxins. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Rossi A, Cazenave J, Bacchetta C, Campana M, Parma MJ (2015) Physiological and metabolic adjustments of Hoplosternum littorale (Teleostei, Callichthyidae) during starvation. Ecol Indic 56: 161-170.

- Jia S, Li X, Zheng S, Wu G (2017) Amino acids are major energy substrates for tissues of hybrid striped bass and zebrafish. Amino Acids 49: 2053-2063. [crossref]

- Perdigoto R, Rodrigues TB, Furtado AL, Porto A, Geraldes C, et al. (2003) Integration of [U-13C] glucose and H2O for quantification of hepatic glucose production and gluconeogenesis. NMR Biomed 16: 189-198.

- Coelho M, Nunes PM, Mendes V, Manadas B, Heerschap A, et al. (2015) Effect of Global ATGL knockout on murine fasting glucose kinetics. J Diabet Res 2015: 542029. [crossref]

- Wu G (2009) Amino Acids: Metabolism, functions, and nutrition. Amino Acids 37: 1-17. [crossref]

- Fickeisen DH, Brown Jr GW (1977) D‐Amino acid oxidase in various fishes. Fish Biol 10: 457-465.

- Deng J, Zhang X, Tao L, Bi B, Kong L, et al. (2011) D‐lysine can be effectively utilized for growth by common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Aquac Nutr 17: 467-475.

- Samsonova MV, Lapteva TI, Yu BF (2005) Aminotransferases in early development of salmonid fish. Russian J Dev Biol 36: 70-74.

- Jiang J, Feng L, Tang L, Liu Y, Jiang W, et al. (2015) Growth rate, body composition, digestive enzymes and transaminases activity, and plasma ammonia concentration of different weight Jian carp (Cyprunus carpio var. Jian). Anim Nutr 1: 373-377.

- Lee JK, Cho SH, Park SU, Kim KD, Lee SM (2003) Dietary protein requirement for young turbot (Scophthalmus maximus L.). Aquac Nutr 9: 283-286.

- Ballantyne JS (2001) Amino acid metabolism. Fish Physiol 19: 77-107.

- Wu G (2014) Dietary requirements of synthesizable amino acids by animals: a paradigm shift in protein nutrition. J Anim Sci Biotechnol 5: 34.

- Li P, Wu G (2020) Composition of amino acids and related nitrogenous nutrients in feedstuffs for animal diets. Amino Acids 52: 523-542.

- Jobling M (1983) A short review and critique of methodology used in fish growth and nutrition studies. J Fish Biol 23: 685-703.

- Hart, Paul JB (2002) Handbook of fish biology and fisheries. New York, NY: Blackwell.

- Cowey CB, Walton MJ (1988) Studies on the uptake of (14C) amino acids derived from both dietary (14C) protein and dietary (14C) amino acids by rainbow trout, Salmo gairdneri Richardson. J Fish Biol 33: 293-305.

- Van de Pol I, Flik G, Gorissen M (2017) Comparative physiology of energy metabolism: Fishing for endocrine signals in the early vertebrate pool. Front Endocrinol 8: 36. [crossref]

- Li XY, Wu G (2019) Oxidation of energy substrates in tissues of Largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). J Anim Sci 97: 68-69.

- Hou YQ, He WL, Hu SD, Wu G (2019) Composition of polyamines and amino acids in plant-source foods for human consumption. Amino Acids 51: 1153-1165. [crossref]

- Li XL, Rezaei R, Li P, Wu G (2011) Composition of amino acids in feed ingredients for animal diets. Amino Acids 40: 1159-1168. [crossref]

- Li XL, Zheng SX, Wu G (2020) Nutrition and metabolism of glutamate and glutamine in fish. Amino Acids 52: 671-691. [crossref]

- Latshaw JD, Bishop BL (2001) Estimating body weight and body composition of chickens by using noninvasive measurements. Poult Sci 80: 868-873. [crossref]

- Ramseyer LJ (2002) Predicting whole-fish nitrogen content from fish wet weight using regression analysis. North Am J Aquac 64: 195-204.

- Falco F, Barra M, Cammarata M, Cuttitta A, Jia S, et al. (2016) Amino acid composition in eyes from zebrafish (Danio rerio) and sardine (Sardina pilchardus) at the larval stage. SpringerPlus 5: 519.

- Cho CY, Kaushik SJ (1990) Nutritional energetics in fish: energy and protein utilization in rainbow trout (Salmo gairdneri). World Rev Nutr Dietet 61: 132-172. [crossref]

- Cho CY, Bureau DP (2001) A review of diet formulation strategies and feeding systems to reduce excretory and feed wastes in aquaculture. Aquac Res 32: 349-360.

- Mommsen TP, French CJ, Hochachka PW (1980) Sites and patterns of protein and amino acid utilization during the spawning migration of salmon. Can J Zool 58: 1785-1799.

- Hemre GI, Mommsen TP, Krogdahl A (2002) Carbohydrates in fish nutrition: Effects on growth, glucose metabolism and hepatic enzymes. Aquac Nutr 8: 175-194.

- Miao S, Nie Q, Miao H, Zhang W, Mai K (2016) Effects of dietary carbohydrate-to-lipid ratio on the growth performance and feed utilization of juvenile turbot (Scophthalmus maximus). J Ocean Univ China 15: 660-666.

- Wu G (2018) Principles of Animal Nutrition. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Van den Thillart G (1986) Energy metabolism of swimming trout (Salmo gairdneri). Oxidation rates of palmitate, glucose, lactate, alanine, leucine and glutamate. J Comp Physiol B 156: 511-520.

- Tacon AGJ, Cowey CB (1985) Fish energetics. Dordrecht: Springer 155-183.

- McKenna MC, Dienel GJ, Sonnewald U, Waagepetersen HS, et al. (2012) Basic Neurochemistry. San Diego, CA: Academic Press 200-231.

- Rønnestad I, Thorsen A, Finn RN (1999) Fish larval nutrition: Recent advances in amino acid metabolism. Aquaculture 177: 201-216.

- Van Waarde A (1983) Aerobic and anaerobic ammonia production by fish. Comp Biochem Physiol B 74: 675-684.

- Gillis TE, Ballantyne JS (1996) The effects of starvation on plasma free amino acid and glucose concentrations in lake sturgeon, Acipenser fulvescens. J Fish Biol 49: 1306-1316.

- Hassel B (2001) Pyruvate carboxylation in neurons. J Neurosci Res 66: 755-762. [crossref]

- Robinson AM, Williamson DH (1980) Physiological roles of ketone bodies as substrates and signals in mammalian tissues. Physiol Rev 60: 143-187. [crossref]

- Canals P, Gallardo MA, Blasco J, Sanchez J (1992) Uptake and metabolism of L-alanine by freshly isolated trout (Salmo trutta) hepatocytes – the effect of fasting. J Exp Biol 169: 37-52.

- Pereira C, Vijayan MM, Moon TW (1995) In vitro hepatocyte metabolism of alanine and glucose and the response to insulin in fed and fasted rainbow trout. J Exp Zool 271: 425-431.

- Sheridan MA, Mommsen TP (1991) Effects of nutritional state on in vivo lipid and carbohydrate metabolism of coho salmon, Oncorhynchus kisutch. Gen Comp Endocrinol 81: 473-483. [crossref]

- Lansard MS, Panserat E, Plagnes J, Seilez I, Skiba Cassy S (2010) Integration of insulin and amino acid signals that regulate hepatic metabolism-related gene expression in rainbow trout: role of TOR. Amino Acids 39: 801-810. [crossref]

- Lansard MS, Panserat E, Plagnes J, Dias K, Sieliez I, et al. (2011) L-leucine, L-methionine, and L-lysine are involved in the regulation of intermediary metabolism-related gene expression in rainbow trout hepatocytes. J Nutr 141: 75-80. [crossref]

- Moon TW (2011) Metabolic reserves and enzyme activities with food deprivation in immature American eels, Anguilla rostrata (LeSueur). Can J Zool 61: 802-811.

- Sánchez-Muros MJ, Garcı́a-Rejón L, Garcı́a-Salguero L, de la Higuera M, Lupianez JA (1998) Long-term nutritional effects on the primary liver and kidney metabolism in rainbow trout. Adaptive response to starvation and a high-protein, carbohydrate-free diets on glutamate dehydrogenase and alanine amino transferase kinetics. Biochem Cell Biol 30: 55-63. [crossref]

- Dias J, Rueda-Jasso R, Panserat S, Conceição LEC, Gomes EF, et al. (2004) Effect of dietary carbohydrate to lipid ratios on growth, lipid deposition and metabolic hepatic enzymes in juvenile Senegal sole (Solea senegalensis). Aquac Res 35: 1122-1130.

- Burrin DG, Stoll B (2009) Metabolic fate and function of dietary glutamate in the gut. Am J Clin Nutr 90: 850-856. [crossref]

- Blachier F, Boutry C, Bos C, Tomé D (2009) Metabolism and functions of L-glutamate in the epithelial cells of the small and large intestines. Am J Clin Nutr 90: 814-821. [crossref]

- Newsholme P, Procopio J, Lima MMR, Pithon-Curi TC, et al. (2003) Glutamine and glutamate -their central role in cell metabolism and function. Cell Biochem Funct 21: 1-9.

- Reeds PJ, Burrin DG, Stoll B, Jahoor F (2000) Intestinal glutamate metabolism. J Nutr 130: 978-982. [crossref]

- Bever K, Chenoweth M, Dunn A (1981) Amino acid gluconeogenesis and glucose turnover in kelp bass (Paralabrax sp). Am J Physiol 240: 246-252. [crossref]

- Ip YK, Lem CB, Chew SF, Wilson JM, Randall DJ (2001) Partial amino acid catabolism leading to the formation of alanine in Periophthalmodon schlosseri (mudskipper): a strategy that facilitates the use of amino acids as an energy source during locomotory activity on land. J Exp Biol 204: 1615-1624. [crossref]

- Andersen SM, Waagbø R, Espe M (2016) Functional amino acids in fish health and welfare. Front Biosci 8: 143-169. [crossref]

- Navarro I, Gutiérrez J (1995) Fasting and starvation. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of Fishes 4: 393-434.

- Metón I, Fernández F, Baanante V (2003) Short and long-term effects of re-feeding on key enzyme activities in glycolysis-gluconeogenesis in the liver of gilthead sea bream. Aquaculture 225: 99-107.

- Figueiredo-Garutti ML, Navarro I, Capilla E, Souza R, Mouraes G, et al. (2002) Metabolic changes in Brycoon cephalus (Teleostei, Characidae) during post-feeding and fasting. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 132: 467-476. [crossref]

- Furné M, Morales AE, Trenzado CE, García-Gallego M, Carmen Hidalgo M, et al. (2012) The metabolic effects of prolonged starvation and re-feeding in sturgeon and rainbow trout. J Comp Physiol 182: 63-76. [crossref]

- Polakof S, Panserat S, Soengas J, Moon T (2012) Glucose metabolism in fish: A review. J Comp Physiol B 182: 1015-1045. [crossref]

- Bequette BJ (2003) Amino acid metabolism in animals: an overview. Amino Acids in Animal Nutrition 2: 103-124.

- Jørgensen EH, Martinsen M, Strøm V, Hansen KER, Ravuri CS, et al. (2013) Long-term fasting in the anadromous Arctic charr is associated with downregulation of metabolic enzyme activity and upregulation of leptin A1 and SOCS expression in the liver. J Exp Biol 216: 3222-3230. [crossref]

- Liang X, Wang J, Xue M, Gong G, Dong Y, et al. (2017) Gluconeogenesis during starvation and refeeding phase is affected by previous dietary carbohydrates levels and a glucose stimuli during early life in Siberian sturgeon (Acipenser baerii). Anim Nutr 3: 284-294.

- Walton MJ, Cowey CB (1982) Aspects of intermediary metabolism in salmonid fish. Comp Biochem Physiol B 73: 59-79.

- Garin D, Rombaut A, Fréminet A (1987) Determination of glucose turnover in sea bass Dicentrarchus labrax. Comparative aspects of glucose utilization. Comp Biochem Physiol B 87: 981-988. [crossref]

- Yancey PH (2001) Fish Physiology. Nitrogen Excretion 20: 309-341.

- Banerjee B, Gitalee B, Nirmalendu S (2014) Influence of environmental hypertonicity on the induction of ureogenesis and amino acid metabolism in air-breathing walking catfish (Clarias batrachus, Bloch). Indian J Exp Biol 52: 728-738. [crossref]

- Rolland M, Feekings JP, Dalsgaard J, Holm J, Skov P (2016) Modelling the effects of dietary methionine level and form on postprandial plasma essential amino acid profiles in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquac Nutr 22: 1185-1201.

- Plakas SM, Katayama T, Tanaka Y, Deshimaru O (1980) Changes in the levels of circulating plasma free amino acids of carp (Cyprinus carpio) after feeding a protein and an amino acid diet of similar composition. Aquaculture 21: 307-322.

- Yamada S, Tanaka Y, Katayama T, Sameshima M, Simpson KL (1982) Plasma amino acid changes in Tilapia nilotica fed a casein and a corresponding free amino acid diet. Bull Jpn Soc Sci Fish 48: 1783-1787.

- Wilson RP, Gatlin DM, Poe WE (1985) Postprandial changes in serum amino acids of channel catfish fed diets containing different levels of protein and energy. Aquaculture 49: 101-110.

- Ferguson RA, Storey KB (1991) Glycolytic and associated enzymes of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) red cells: in vitro and in vivo studies. J Exp Biol 155: 469-485.

- Bae JY, Ok IH, Lee S, Hung SS, Min TS, et al. (2011) Reevaluation of dietary methionine requirement by plasma methionine and ammonia concentrations in surgically modified rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss. J Appl Ichthyol 27: 887-891.

- Brett JR, Zala CA (1975) Daily pattern of excretion and consumption of sockeye salmon under controlled conditions. J Fish Res Board Can 33: 2479-2486.

- Walton MJ, Wilson R (1986) Postprandial changes in plasma and liver free amino acids of rainbow trout fed complete diets containing casein. Aquaculture 51: 105-115.

- Costas B, Aragao C, Jarabo IR, Chacoff LV, Arjona FJ, et al. (2011) Feed deprivation in Senegalese sole (Solea senegalensis Kauo, 1858) juveniles: Effects on blood plasma metabolites and free amino acid levels. Fish Physiol Biochem 37: 495-504. [crossref]

- Suarez RK, Mommsen TP (1986) Gluconeogenesis in teleost fishes. Can J Zool 65: 1869-1882.

- Navarro I, Blasco J, Baños N, Gutiérrez J (1997) Effects of fasting and plasma amino acid levels in brown trout. Fish Physiol Biochem 16: 303-309.

- Randall DJ, Tsui TKN (2002) Ammonia toxicity in fish. Mar Pollut Bull 45: 17-23.

- French CJ, Mommsen TP, Hochachka PW (1981) Amino acid utilisation in isolated hepatocytes from rainbow trout. Eur J Biochem 113: 311-317. [crossref]

- Legate NJ, Bonen A, Moon TW (2001) Glucose tolerance and peripheral glucose utilization in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), American eel (Anguilla rostrata), and black bullhead catfish (Ameiurus melas). Gen Comp Endocrinol 122: 48-59. [crossref]

- Kopio RR, Murray DM, Story DL, Brunengraber H (1984) The shunt pathway of mevalonate metabolism in the isolated perfused rat kidney. J Biol Chem 259: 372-377. [crossref]

- Barreto-Curiel F, Focken U, D’Abramo LR, Viana MT (2017) Metabolism of Seriola lalandi during starvation as revealed by fatty acid analysis and compound-specific analysis of stable isotopes within amino acids. PloS One 12: 0170124. [crossref]

- Navarro I, Gutierrez J, Planas J (1992) Changes in plasma-glucagon, insulin and tissue metabolites associated with prolonged fasting in brown trout (Salmo trutta fario) during two different seasons of the year. Comp Biochem Physiol Comp Physiol 102: 401-407. [crossref]

- Pottinger TG, Rand-Weaver M, Sumpter JP (2003) Overwinter fasting and re-feeding in rainbow trout: plasma growth hormone and cortisol levels in relation to energy mobilisation. Comp Biochem Physiol B biochem Mol Biol 136: 403-417. [crossref]

- Kullgren A, Samuelsson LM, Larsson DGJ, Björnsson BT, Bergman EJ (2010) A metabolomics approach to elucidate effects of food deprivation in juvenile rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 299: 1440-1448. [crossref]

- Rønnestad I, Nilsen TO, Murashita K, Angotzi AR, Gamst Mohn AG, et al. (2010) Leptin and leptin receptor genes in Atlantic salmon: Cloning, phylogeny, tissue distribution and expression correlated to long-term feeding status. Gen Comp Endocrinol 168: 55-70. [crossref]

- Trombley S., Schmitz M (2013) Leptin in fish: Possible role in sexual maturation in male Atlantic salmon. Fish Physiol Biochem 39: 103-106. [crossref]

- Boonanuntanasarn S, Kumkhong S, Yoohat K, Plagnes-Juan E, Burel C, et al. (2018) Molecular responses of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) to different levels of dietary carbohydrates. Aquaculture 482: 117-123.

- Kamalam BJ, Medale F, Panserat S (2017) The utilisation of dietary carbohydrates in farmed fishes: new insights on influencing factors, biological limitations and future strategies. Aquaculture 467: 3-27.

- Wang Y, Liu YJ, Tian LX, Du ZY, Wang JT, et al. (2005) Effects of dietary carbohydrate level on growth and body composition of juvenile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus×O. aureus. Aquac Res 36: 1408-1413.

- Azaza MS, Khiari N, Dhraief MN, Aloui, N, Kraiem MM, et al. (2015). Growth performance, oxidative stress indices and hepatic carbohydrate metabolic enzymes activities of juvenile Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus L., in response to dietary starch to protein ratios. Aquac Res 46: 14-27.

- Gaye-Siessegger J, Focken U, Becker K (2006) Effect of dietary protein/carbohydrate ratio on activities of hepatic enzymes involved in the amino acid metabolism of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus (L.). Fish Physiol Biochem 32: 275-282.

- Chen MY, Ye JD, Yang W, Wang K (2013) Growth, feed utilization and blood metabolic responses to different amylose-amylopectin ratio fed diets in tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Asian Australas J Anim Sci 26: 1160-1171.

- Chen YJ, Zhang T, Chen HY, Lin S, Luo L, et al. (2017) An evaluation of hepatic glucose metabolism at the transcription level for the omnivorous GIFT tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus during the postprandial nutritional status transition from anabolism to catabolism. Aquaculture 473: 375-382.

- Figueiredo-Silva AC, Saravanan S, Schrama JW, Panserat S, Kaushik S, et al. (2013) A comparative study of the metabolic response in rainbow trout and Nile tilapia to changes in dietary macronutrient composition. Br J Nutr 109: 816-826. [crossref]

- Wu G (1998) Intestinal mucosal amino acid catabolism. J Nutr 128: 1249-1252. [crossref]

- Kirchgessner AL (2001) Glutamate in the enteric nervous system. Curr Opin Pharmacol 1: 591-596. [crossref]

- Rezaei R, Knabe DA, Tekwe CD, Dahanayaka S, Ficken MD, et al. (2013) Dietary supplementation with monosodium glutamate is safe and improves growth performance in postweaning pigs. Amino Acids 44: 911-923. [crossref]

- Gibbs SR, DeRoos RM (1991) Plasma levels of glucose, ketone bodies, lactate, and alanine in the vascular supply to and from the brain of the adult American bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana). J Exp Zool 258: 14-23. [crossref]

- Edmond J, Auestad N, Robbins RA, Bergstrom JD (1985) Ketone body metabolism in the neonate: development and the effect of diet. Fed Proc 44: 2359-2364. [crossref]

- Dienel GA, Cruz NF (2003) Neighborly interactions of metabolically activated astrocytes in vivo. Neurochem Int 43: 339-354.

- Nakamura H, Kawamata Y, Kuwahara T, Torii K, Sakai R (2013) Nitrogen in dietary glutamate is utilized exclusively for the synthesis of amino acids in the rat intestine. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 304: 100-108. [crossref]

- Weber JM, Choi K, Gonzalez A, Omlin T (2016) Metabolic fuel kinetics in fish: swimming, hypoxia and muscle membranes. J Exp Biol 219: 250-258.

- Haman F, Powell M, Weber JM (1997) Reliability of continuous tracer infusion for measuring glucose turnover rate in rainbow trout. J Exp Biol 200: 2557-2563. [crossref]

- Robinson J, Yanke D, Mirza J, Ballantyne JS (2011) Plasma free amino acid kinetics in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) using a bolus injection of 15N-labeled amino acids. Amino Acids 40: 689-696. [crossref]

- Weber M (2011) Metabolic fuels: regulating fluxes to select mix. J Exp Biol 214: 286-294. [crossref]

- Ip YK, Randall DJ, Kok TKT, Barzaghi C, Wright PA, et al. (2004) The giant mudsipper Periophthalmodon schlosseri facilitates active NH4+ excretion by increasing acid excretion and decreasing NH3 permeability in the skin. J Exp Biol 207: 787-801. [crossref]

- Lim CB, Chew SF, Anderson PM, Ip YK (2001) Reduction in the rates of protein and amino acid catabolism to slow down the accumulation of endogenous ammonia: a strategy potentially adopted by mudskippers (Periophthalmodon schlosseri and Boleophthalmus boddaerti) during aerial exposure in constant darkness. J Exp Biol 204: 1605-1614. [crossref]

- Ip YK, Lee CY, Chew SF, Low WP, et al. (1993) Differences in the responses of two mudskippers to terrestrial exposure. Zool Sci 10: 511-519.

- Mommsen TP, Walsh PJ (1992) Biochemical and environmental perspectives on nitrogen metabolism in fishes. Experientia 48: 583-593.

- Hochachka PW, Guppy M (1987) Metabolic arrest and the control of biological time. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press: 253-284.

- Kim K, Wang X, Bai SC (2003) Reevaluation of the dietary protein requirement of Japanese flounder Paralichthys olivaceus. J World Aquac Soc 34: 133-139.

- Van Waarde A (1981) Nitrogen metabolism in goldfish, Carassius auratus (L.). Activities of transamination reactions, purine nucleotide cycle and glutamate dehydrogenase in goldfish tissues. Comp Biochem Physiol B 68: 407-413.

- Teigland M, Kkungsoyr L (1983) Accumulation of alpha-ketoisocaproate from leucine in homogenates of tissues from rainbow trout (Salmo gairdnerii) and rat. An improved method for determination of branched chain keto acids. Comp Biochem Physiol B 75: 703-705.

- Fontaine J (2003) Amino Acids in Animal Nutrition. Wallingford, UK: CABI Publishing: 15-40.

- Nwanna LC, Lemme A, Abdallah M, Schwarz FJ (2012) Response of common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.) to supplemental DL-methionine and different feeding strategies. Aquaculture 356: 365-370.

- Shamushaki VAJ, Kasumyan AO, Abedian A, Abtahi B (2007) Behavioural responses of the Persian sturgeon (Acipenser persicus) juveniles to free amino acid solutions. Mar Freshwater Behav Physiol 40: 219-224.

- Palma PFS, Bock C, Silva TS, Guerreiro PM, Power DM, et al. (2019) STC1 and PTHrP modify carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in liver of a teleost fish. Sci Rep 9: 723.

- Fang YZ, Yang S, Wu G (2002) Free radicals, antioxidants, and nutrition. Nutrition 8: 872-879. [crossref]

- Li P, Wu G (2018) Roles of dietary glycine, proline and hydroxyproline in collagen synthesis and animal growth. Amino Acids 50: 29-38. [crossref]

- Lin CY, Huang LH, Deng DF, Lee SH, Liang HJ, et al. (2019) Metabolic adaptation to feed restriction on the green sturgeon (Acipenser medirostris) fingerlings. Sci Total Environ 684: 78-88. [crossref]

- Chen C, Shengyao LF, Kuang S, Liu Y, Jiang J, et al. (2012) Effect of dietary arginine on growth, intestinal enzyme activities and gene expression in muscle, hepatopancreas and intestine of juvenile Jian carp (Cyprinus carpio var. Jian). Br J Nutr 108: 195-207. [crossref]

- Dabrowski K, Terjesen BF, Zhang Y, Phang JM, Lee KJ (2005). A concept of dietary dipeptides a step to resolve the problem of amino acid availability in the early life of vertebrates. J Exp Biol 208: 2885-2894. [crossref]

- Wright PA, Campbell A, Morgan RL, Rosenberger AG, Murray BW (2004) Dogmas and controversies in the handling of nitrogenous wastes: Expression of arginase Type I and II genes in rainbow trout: influence of fasting on liver enzyme activity and mRNA levels in juveniles J Exp Biol 207: 2033-2042.

- Jobgen WS, Fried SK, Fu WJ, Meininger CJ, Wu G (2006) Regulatory role for the arginine–nitric oxide pathway in metabolism of energy substrates. J Nutr Biochem 17: 571-588. [crossref]