DOI: 10.31038/JPPR.2020324

Abstract

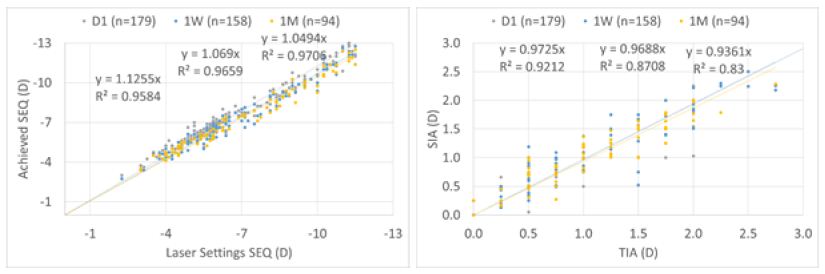

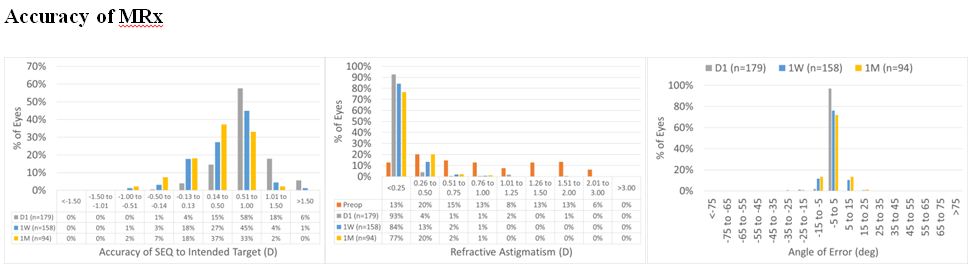

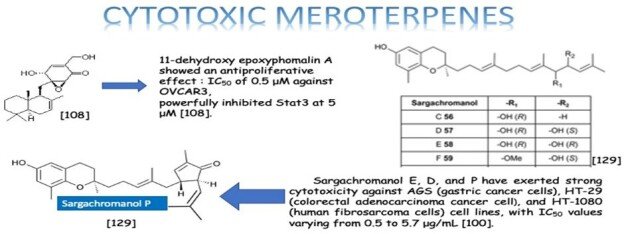

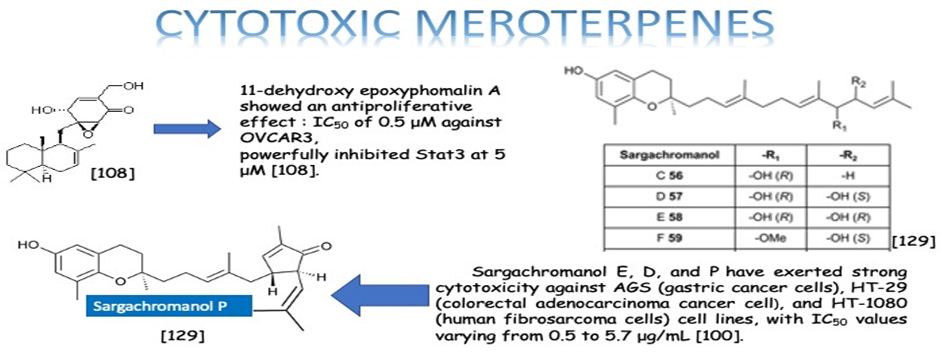

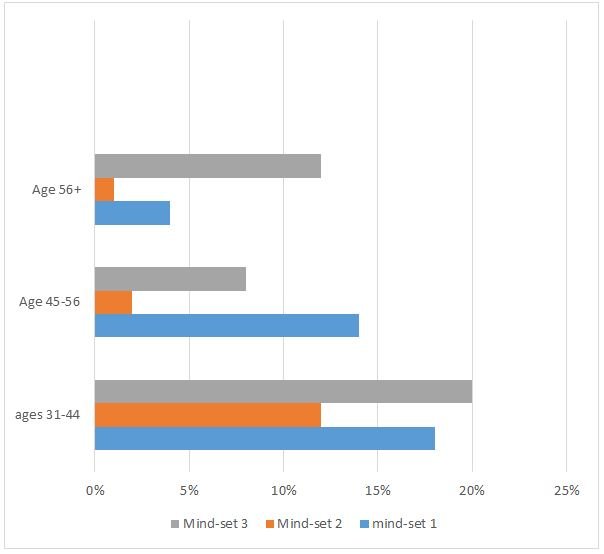

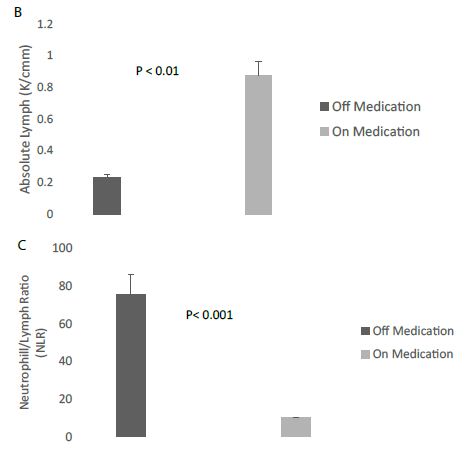

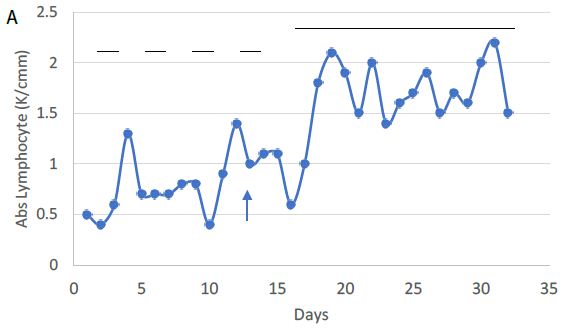

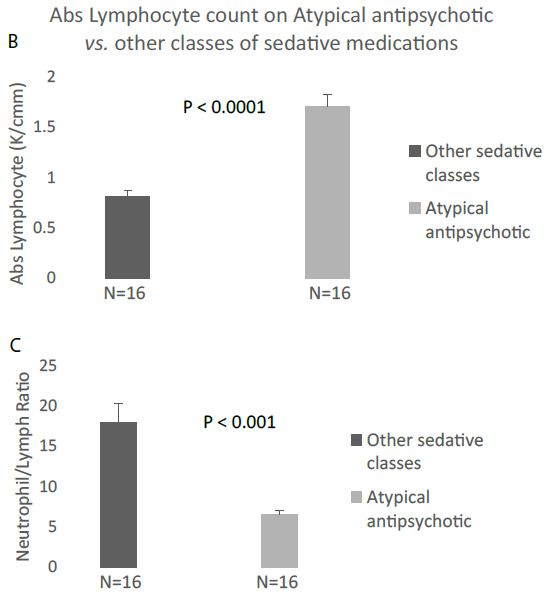

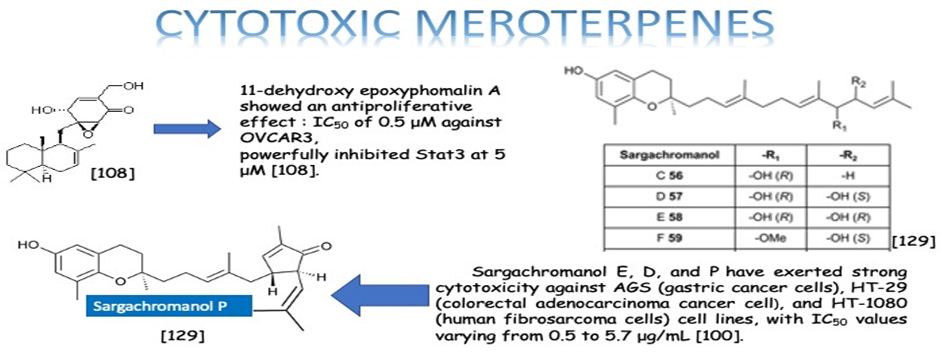

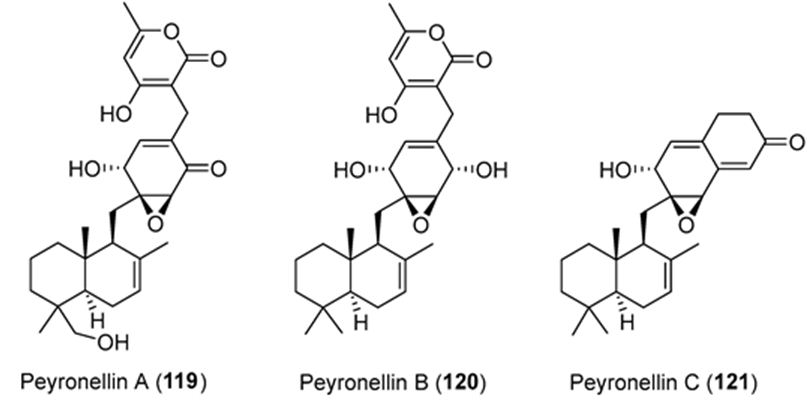

Meroterpenes are mixed natural products. They consist of one terpene and one polyketide skeletons. Due to their structural varieties, meroterpenoids display diverse bioactivities, like anticancer, anti-inflammatory, anti-biotic, and antifibrotic activities. Our aim is to highlight the importance of the meroterpenes which have been the most studied on and reported among the bioactive natural products last years. According to our literature survey, the three most effective meroterpene groups have been determined. One group is the meroterpenes isolated from the brown alga Sargassum siliquastrum: Sargachromanol E, D, and P have exerted strong cytotoxicity against AGS (gastric cancer cells), HT-29 (colorectal adenocarcinoma cancer cell), and HT-1080 (human fibrosarcoma cells) cell lines, with IC50 values varying from 0.5 to 5.7 μg/mL [100]. The other most effective meroterpene is Eucalypglobulusal F, which is isolated from E. globulus fruit, has shown cytotoxicity against the human acute lymphoblastic cell line (CCRF-CEM) with an IC50 value of 3.3 μM [89]. Also, the last one is 11-dehydroxy epoxyphomalin A (4), from the endophytic fungus Peyronellaea coffeae-arabicae FT238, which was obtained from the native Hawaiian plant Pritchardia lowreyana showed a strong antiproliferative effect with an IC50 of 0.5 μM against OVCAR3 (Ovarian carsinoma cells) [102]. Conclusively, meroterpenes have potential nominees as an anticancer drug. Moreover, the structure of naturally isolated meroterpenes has a moderate anticancer activity that can easliy be modified by semi-synthetic ways due to their simple structures comparing to other natural compounds such as triterpenes or phenolic compounds.

Introduction

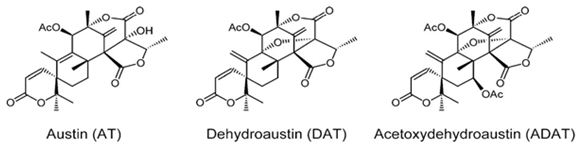

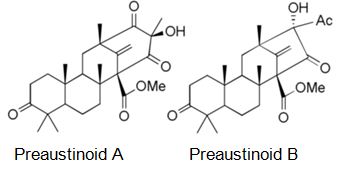

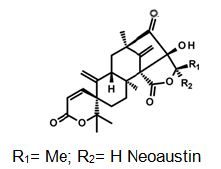

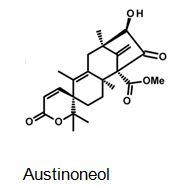

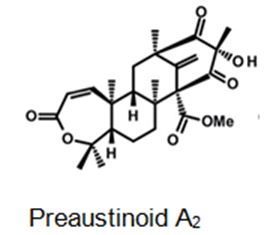

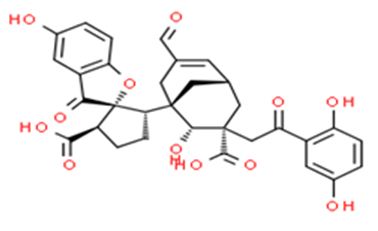

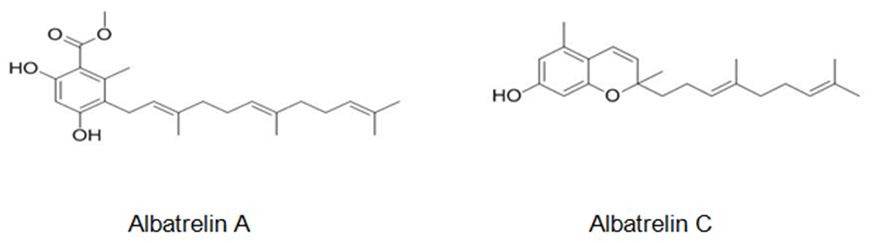

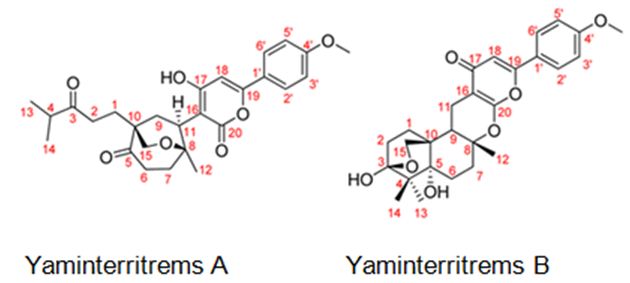

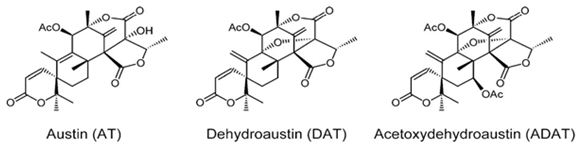

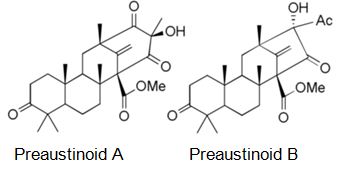

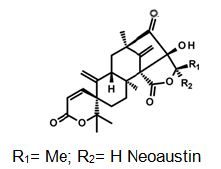

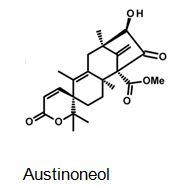

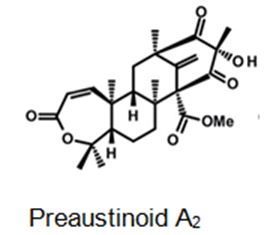

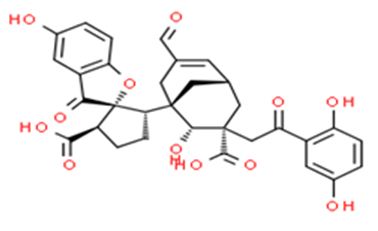

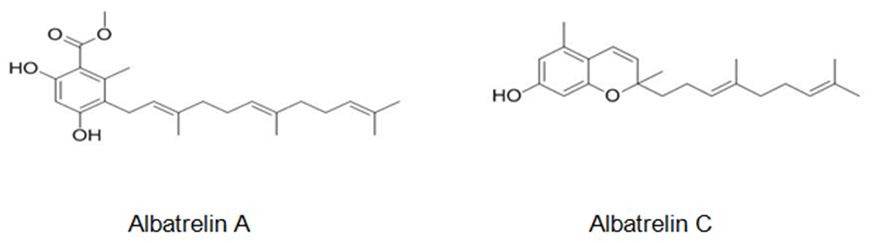

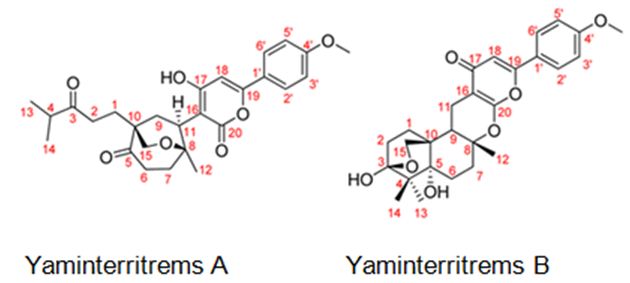

Natural products are extensively known to be a major resource of biologically active compounds that hold manifold and unusual platforms [1]. Terpenoids are structurally differing secondary metabolites with more than 40,000 reported structural diversity bearing valuable bioactive characters [2,3] Their structures are chiefly sourced from plants and microbes, which are mainly biosynthesized by the 2-C- methylerythritol 4-phosphate pathway or the mevalonate pathway [4,5]. Terpenoids were known to have potential pharmacological properties against fatal diseases, such as malaria [6], cardiovascular disease [7], and cancer [3,8]. Meroterpenoids are hybrid secondary metabolites that moderately obtain from the terpenoid pathways [9,10]. Especially, meroterpenoids derived from polyketide and terpenoid precursors have sp3-rich terpenoid scaffolds and sp2-rich polyketide scaffolds, which argue different pharmacological activities [11]. Their carbon skeletons come from intra- and intermolecular cyclizations and/or rearrangements of terpene chains to give unique polycyclic or macrocyclic structures often possessing varied functional groups [12,13]. Naturally exist meroterpenoids have been obtained from a variety of origins containing animals, plants, bacteria, and fungi [14], and are demonstrated by ubiquinone-10 (coenzyme Q10) [15], α-tocopherol (vitamin E) [16], vinblastine [17], merochlorin A [18,19], and teleocidin B-4 [10,20]. Meroterpenoids are usually isolated from fungi and marine organisms. Otherwise, plants can produce minimal groups of meroterpenoids, such as cannabinoids and polyprenylated phloroglucinols [9], despite plants are rich sources of various types of terpenoids [11]. Stemming from their structural variety, meroterpenoids show various bioactivities, like anticancer [21], anti-inflammatory [22], anti-biotic [23], and antifibrotic [24] activities. In current years, the alluring chemical structures and impressive biological activities of these compounds have appealed to considerable interest from the synthetic and pharmacological societies [14,25-27]. Considering meroterpenes which have been commonly isolated in fungi from Penicillium and Aspergillus genera [28]: Austin (Figure 1) is a good characteristic of this class, having been isolated for the first time in 1976 by Chexal et al. from a culture of Aspergillus ustus [29]. Afterward, in 1994, it was isolated, besides five other meroterpenes, from Penicillium sp. [30]. Assorted Austin-like compounds have been published from an endophyte species of Penicillium cultivated in rice: preaustinoid A and B (Figure 2) [31], 7-b-acetoxydehydroaustin, neoaustin (Figure 3), dehydro-austin (Figure 1), austinoneol (Figure 4) [32], preaustinoid A1, A2 (Figure 5) and B1 [33]. Several derivatives exhibit activity against Escherichia coli, Bacillus sp., and Pseudomonas aureginosa [33,34]. Further examples contain applanatumin A (Figure 6), a novel meroterpenoid dimer with potent antifibrotic activity from Ganoderma applanatum [24], albatrelins A–C (Figure 7), three novel dimers with cytotoxicity from Albatrelleus ovinus [35], and yaminterritrems A and B (Figure 8) with a novel skeleton and inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 expression from Aspergillus terreus. As it has been understood from all the examples fungi are recognized as producers of meroterpenoids with novel structures and various bioactivities [36,37].

Figure 1: The molecular structure of Austin, dehydroaustin and acetoxydehydroaustin [38].

Figure 2: The molecular structure of Preaustinoid A and B [39].

Figure 3: The molecular structure of Neoaustin [40].

Figure 4: The molecular structure of Austinoneol [40].

Figure 5: The molecular structure of Preaustinoid A2 [40].

Figure 6: The molecular structure of Applanatumin A [41].

Figure 7: The molecular structure of Albatrelin A [42] and C [43].

Figure 8: The molecular structure of Yaminterritrems A and B [36].

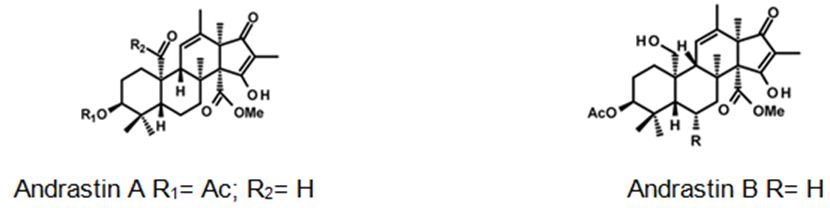

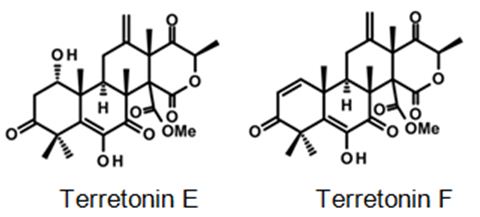

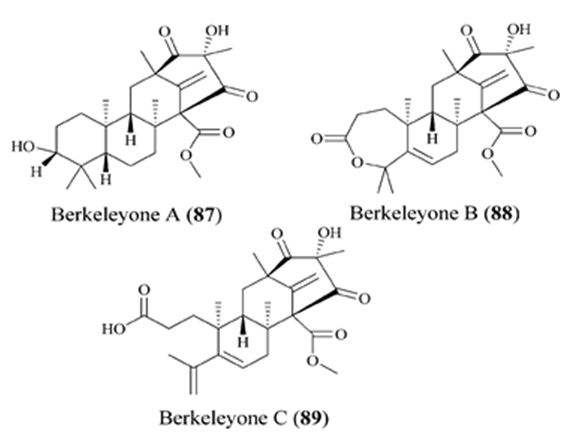

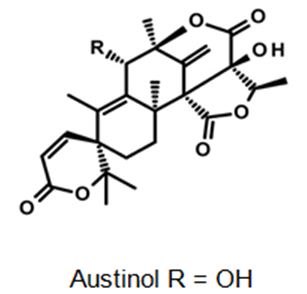

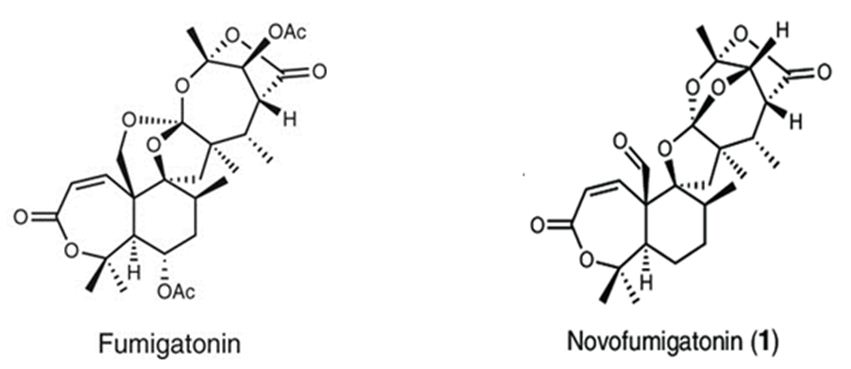

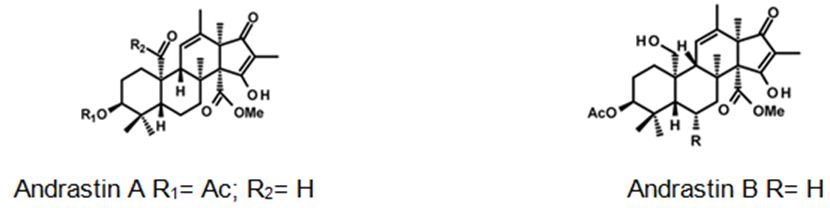

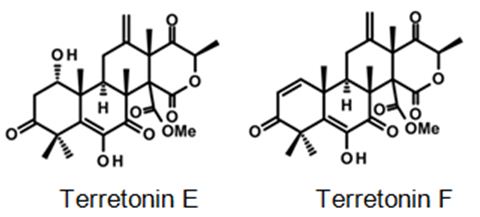

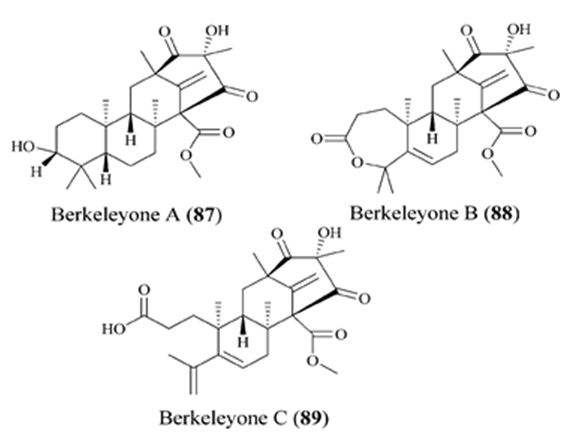

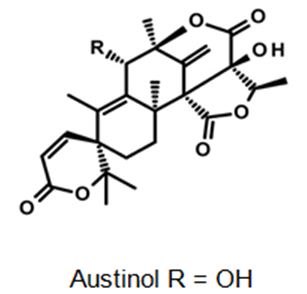

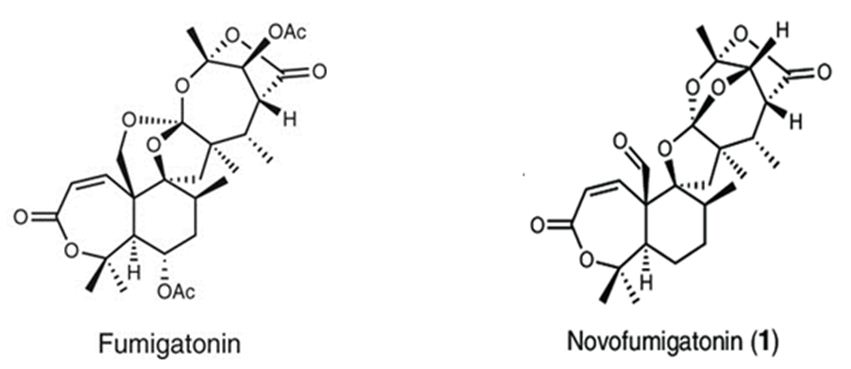

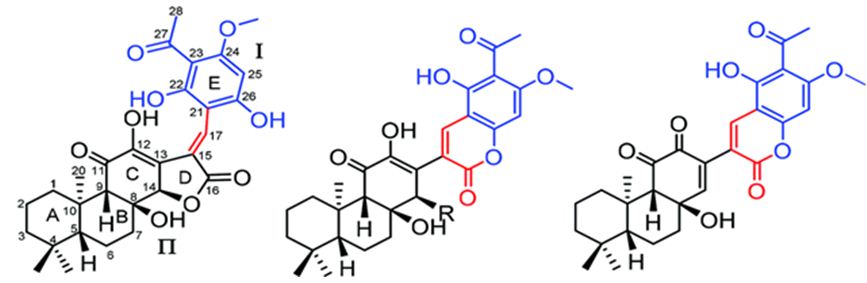

Biosynthetically, the composite structures of fungal meroterpenoids are largely originated from plain precursors alike a linear isoprenoid or the C-2 carbon unit acetyl-CoA, via a series of chemical transformations catalyzed by two enzyme groups, terpene cyclases and polyketide synthases (PKSs) [44,45]. Also the huge structural diversity, fungal meroterpenoids have drawn wide interest from the scientific society because of their wide spectrum of pharmacological activities [10,46-49]. The meroterpenoids from endophytic fungi were classified into two major groups: polyketide–terpenoids and non-polyketide– terpenoids [9,50]. α-pyrone meroterpenoids including triketide terpenoid moieties were identified from the fungi with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors [51]. Thus these α-pyrone meroterpenoids have been appealing to chemists and pharmacologists’ appreciable attention [52]. The α-pyrone meroterpenoids form an important subset of this class and have a familiar C3-oxidized drimane unit that is connected to numerous polyketide- based pyrone fragments at C11 [51]. Members of this group show a wide range of bioactivity differing from anti-cholinesterase activity to acyl-CoA/cholesterol acyltransferase inhibition. While not, as usual, meroterpenoids having a diterpene unit have also been discovered in nature [53]. Members of this subset naturally share a typical C3-oxidized ent-isocopalane fragment that takes place in mixture with various aromatics and has been known to show anti-mycobacterial, insecticidal and cytotoxic characteristics [54]. Pyripyropenes and phenylpyropenes are subclasses of meroterpenes actual in the filamentous fungi genus Aspergillus and Penicillium. These compounds are biogenetically originated from a hybrid of polyketide and terpenoid. Their structures were contained in three parts: a pyridine/phenyl ring, an α-pyrone, and a sesquiterpene motif. Subsequently, they were first isolated in 1994, 19 pyripyropenes were exhibit to be effective as acyl-CoA/cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT) inhibitors and are thought to be beneficial in the avoidance and treatment of hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis [55-60]. In the marine environment, meroterpenes are compounds of assorted biosynthesis, essentially quinone or hydroquinones bonded with a terpenoid portion differing from one to nine isoprene units. These secondary metabolites are obtained principally from brown algae such as Cystoseira [61], marine microorganisms [28], soft corals [62], or marine invertebrates, such as sponges or ascidians [63,64]. Several prenylated hydroquinones inhibit the proliferation of a panel of cancer cells [65-67]. Furthermore, three new sesqui- and diterpene hydroquinone MK2 or PI3 kinase inhibitors have been reported from demosponges [68-70]. The fungal meroterpenoids as the interesting hybrid natural products are broadly scattered in marine environments with various molecular architectures, that are brought terpene moieties together other precursors such as polyketide unit by diverse biosynthetic pathways [48,71-73]. Among the fungus-originated meroterpenoids, a polyketide-terpenoid biosynthetic pathway that has a C-alkylation of 3,5-dimethylorsellinic acid (DMOA) with farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) produced more than 100 secondary metabolites alongside several unique scaffolds [9,14]. The biogenetic pathways of these usual natural products have been largely investigated, disclosing a set of synthetic gene clusters and functional enzymes [74-76]. The structural diversity of the DMOA-based meroterpenoids was ascribed to sequential cyclization, complex oxidative ring rearrangement, and recyclization. Stand on the carbocyclic frameworks, the DMOA-FPP derived meroterpenoids can be grouped into seven subtypes. Andrastins having a 6,6,6,5-tetra-carbocyclic skeleton (Figure 9) are the potent inhibitors of RAS proteins, which are important for regulating cell division and the progressing of cancer [77]. Terretonin-type (Figure 10) congeners bearing a δ-lactone in ring D are derived from terrenoid (andrastin- type) by D-ring expansion and bizarre rearrangement of the methoxy group [78]. Berkeleyone- type (or protoaustinoid-type) (Figure 11) derivatives being the caspase- 1 inhibitor is the meroterpenoids defining a set of unique and functionalized chemical scaffolds, which are identified by the existence bicyclo [3.3,1]nonane or its rearranged bicyclo[3,2,1]octane unit in rings C and D [79], and are originated by the same intermediate as for andrastins with miscellaneous rearrangement. Austinol (Figure 12) and its analogs displayed a pentacyclic scaffold with a spiro-δ-lactone in ring A and a γ-lactone in ring E, that was originated from protoaustinoid through oxidation and ring rearrangement [80]. Chrysogenolides are a class of DMOA- based compounds with a rare seven-numbered ring B, which shows the inhibition of nitric oxide production [73], while anditomin analogs highlighted the presence of an uncommon and highly oxygenated bridged-ring system [81-88]. Fumigatonin and novofumigatonin (Figure 13) are an extra subtype consisting of highly oxidized and complexed condensed ring systems [82,83]. These meroterpenoids have been stated to own a range of biological activities [83-85].

Figure 9: The molecular structure of Andrastin A and B [40].

Figure 10: Some examples for Terretonin type-meroterpenes: isolated from the culture extract of the marine derived-fungus Aspergillus insuetus [40].

Figure 11: The molecular structure of Berkeleyone A-C [86].

Figure 12: The molecular structure of Austinol [40].

Figure 13: The molecular structure of Fumigatonin and Novofumigatonin [87].

Anticancer, Cytotoxic, and Antitumor Activity

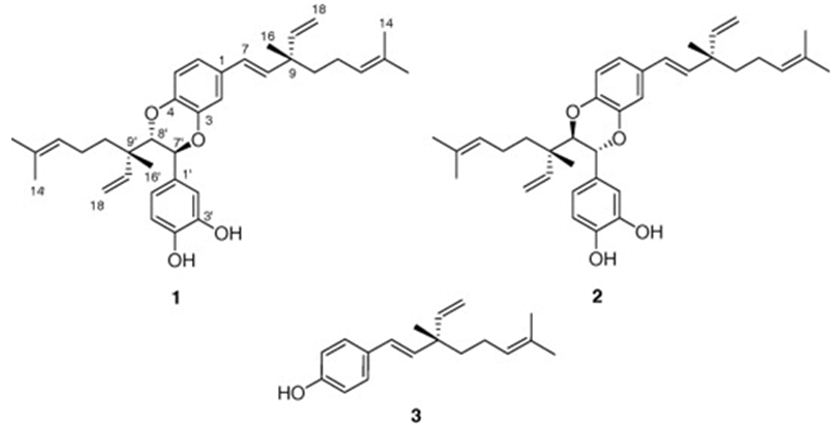

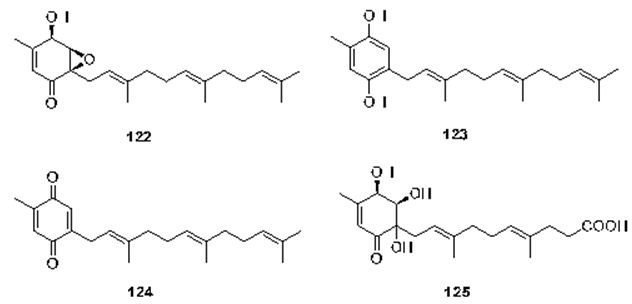

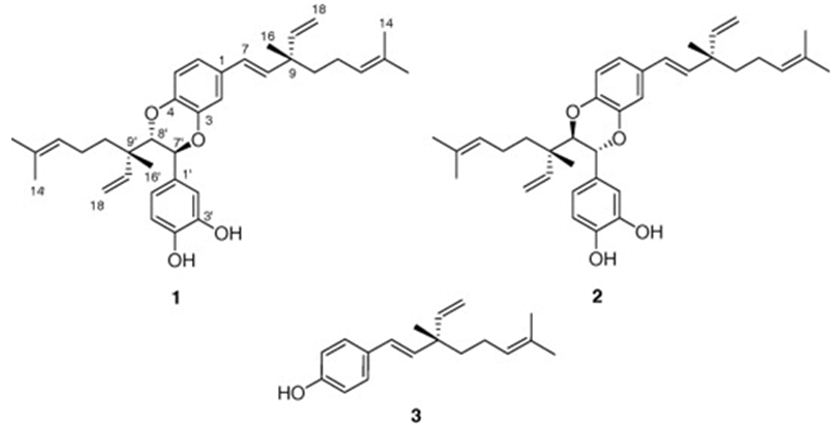

We have mentioned two studies about Psoralea sp.: One belongs to Wu et all. They have obtained two novel dimeric meroterpenoids, bisbakuchiols A (1) and B (2), along with (S)-bakuchiol (3) from the seeds of Psoralea corylifolia L. (Fabaceae) (Figure 14). Bisbakuchiols A and B consist of an extraordinary dimeric meroterpenoid skeleton in which two meroterpenes are connected through a dioxane bridge. All compounds have been examined for their potential to inhibit hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) activation induced by hypoxia in a HIF-1-mediated reporter gene assay in AGS human gastric cancer cells. (S)-Bakuchiol inhibited hypoxic activation of HIF-1 with an IC50 value of 6.1 μM [88].

Figure 14: The molecular structure of bisbakuchiols A (1) and B (2), and (S)-bakuchiol (3) [88].

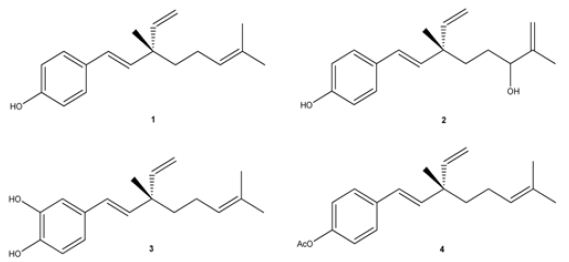

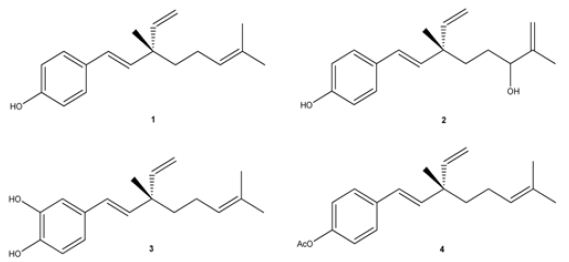

The other is made by Madrid and his research group. They have investigated the biological activity of the resinous exudate of aerial parts from Psoralea glandulosa, and its active components (bakuchiol (1), 3-hydroxy-bakuchiol (2) and 12-hydroxy-iso-bakuchiol (3)) (Figure 15) against melanoma cells (A2058). Also, the effect in cancer cells of bakuchiol acetate (4) (Figure 15), a semi-synthetic derivative of bakuchiol, have been examined. The results achieved show that the resinous exudate inhibited the growth of cancer cells with an IC50 value of 10.5 μg/mL after 48 h of treatment, while, for pure compounds, the most active was the semi-synthetic compound 4. Their data also proved that resin can induce apoptotic cell death, which could be associated with a complete action of the meroterpenes existing [89].

Figure 15: The molecular structure of Bakuchiol (1), 3-hydroxy-bakuchiol (2), 12-hydroxy-iso-bakuchiol (3), and semi-synthetic derivative of bakuchiol: bakuchiol acetate (4) [89].

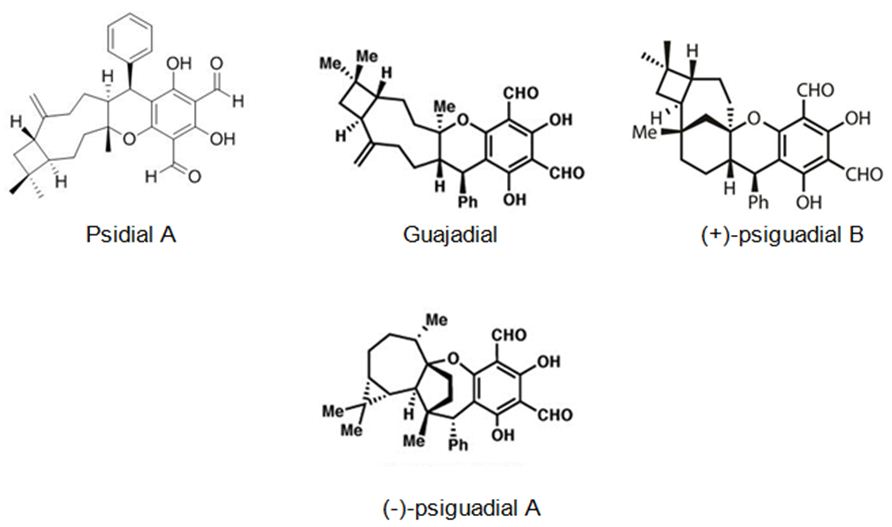

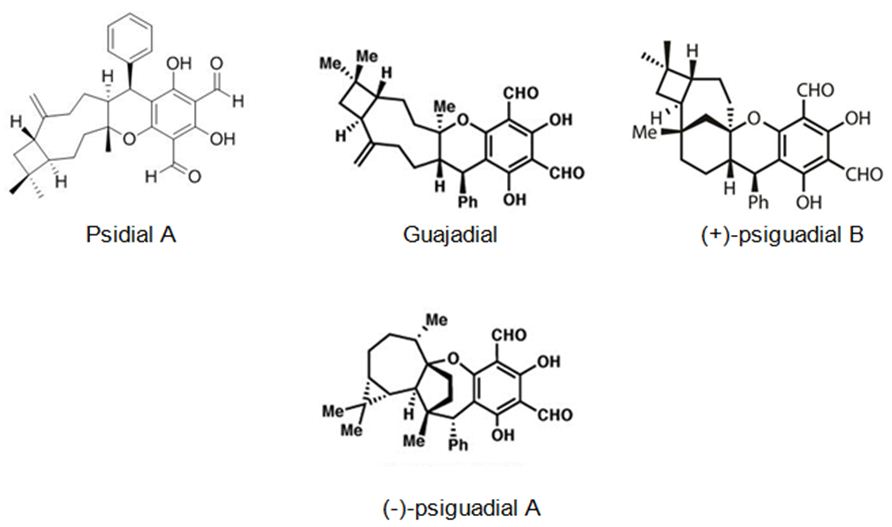

The second most studied plant example is Psidium guajava L. (guava). Rizzo et. all have searched in vitro, in vivo and in silico anticancer and estrogen-like activity of Psidium guajava L. (guava) extracts and enriched mixture including the meroterpenes guajadial, psidial A and psiguadial A and B (Figure 16). All samples were assessed in vitro for anticancer activity against nine human cancer lines: K562 (leukemia), MCF7 (breast), NCI/ADR-RES (resistant ovarian cancer), NCI-H460 (lung), UACC-62 (melanoma), PC-3 (prostate), HT-29 (colon), OVCAR-3 (ovarian) and 786-0 (kidney). Psidium guajava‘s active compounds shown similar physicochemical characteristics to estradiol and tamoxifen, as in silico mol. docking studies displayed that they fit into the estrogen receptors (ERs). The meroterpene-enriched fraction was also appraised in vivo in a Solid Ehrlich murine breast adenocarcinoma model and exhibited to be highly active in preventing tumor growth, also showing uterus increase in comparison to negative controls. The capability of guajadial, psidial A and psiguadials A and B to decrease tumor growth and arouse uterus proliferation, they are in silico docking similarity to tamoxifen too, indicate that these compounds may act as Selective Estrogen Receptors Modulators (SERMs), hence holding important potential for anticancer treatment [90].

Figure 16: The molecular structure of guajadial, psiguadial A-B [91] and psidial A [92].

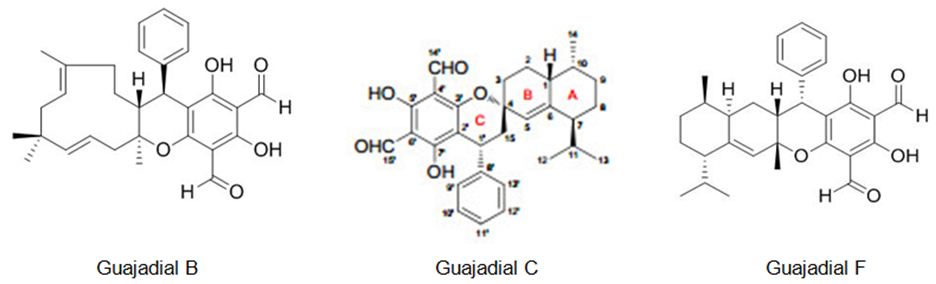

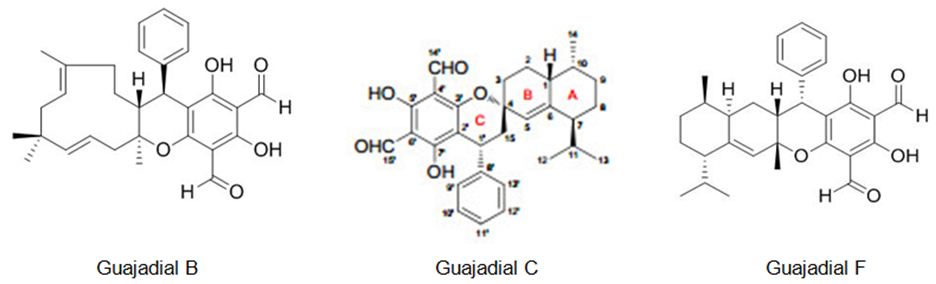

Qin et al. also have studied Psidium guajava L fruits, it has resulted in the identification of two new meroterpenoids, psiguajavadials A (I) and B (II), along with 14 earlier defined meroterpenoids. All of the meroterpenoids have exhibited cytotoxicities against five human cancer cell lines, with guajadial B (12) being the most powerful having an IC50 value of 150 nM toward A549 cells. Additionally, biochemical topoisomerase I (Top1) assay has disclosed that psiguajavadial A, psiguajavadial B, guajadial B, guajadial C, and guajadial F (Figure 17) served as Top1 catalytic inhibitors and deferred Top1 poison-mediated DNA damage. The flow cytometric analysis has pointed out that the new meroterpenoids psiguajavadials A and B could induce apoptosis of HCT116 cells. These data indicate that meroterpenoids from guava fruit could be used for the progress of antitumor agents [93].

Figure 17: The molecular structure of guajadial B [94], guajadial C [95] and guajadial F [96].

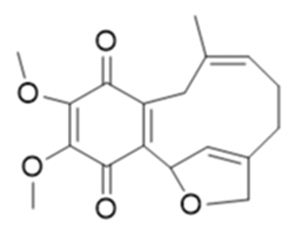

JNU-144 (Figure 18): a new meroterpenoid has been isolated, from Lithospermum erythrorhizon, and investigated its’ antitumor activity on all hepatoma cell lines, JNU-144 shown potent anti-tumor effects. Particularly, in SMMC-7721 cells, JNU-144 induced apoptosis by activating the intrinsic apoptosis pathway. The researchers have also discovered that JNU-144 inhibited EMT in both SMMC-7721 and HepG2 cells by reprogramming the gene expression profile. Moreover, JNU- 144 suppressed tumor growth in vivo. These results prove the potential for JNU-144 as a novel therapeutic drug for liver cancer [97].

Figure 18: The molecular structure of JNU-144 [97].

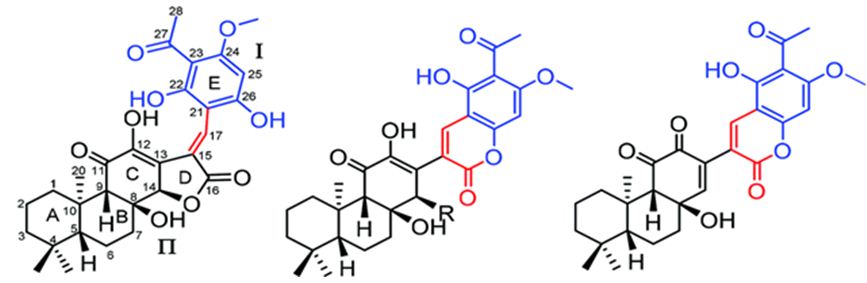

Zhang et al. have obtained Fischernolides A-D (1-4) (Figure 19), four meroterpenoids based on diterpene and acylphloroglucinol, having an unprecedented 28-carbon skeleton with a novel scaffold, from the roots of Euphorbia fischeriana. Compound 2 exerted significant cytotoxicity and can induce the apoptosis of MCF-7 and Bel-7402 cell lines by caspase activation [98].

Figure 19: The molecular structure of Fischernolides A-D (1-4) [98].

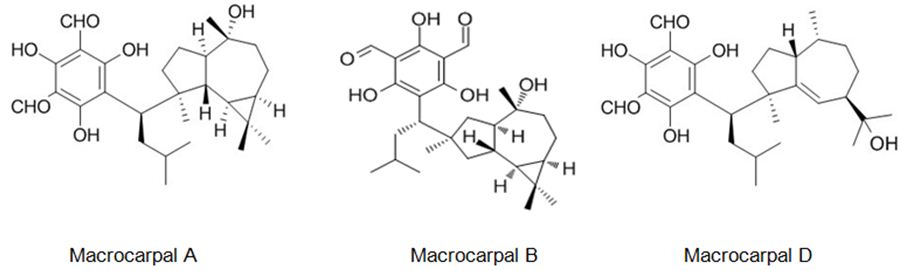

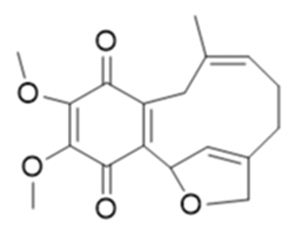

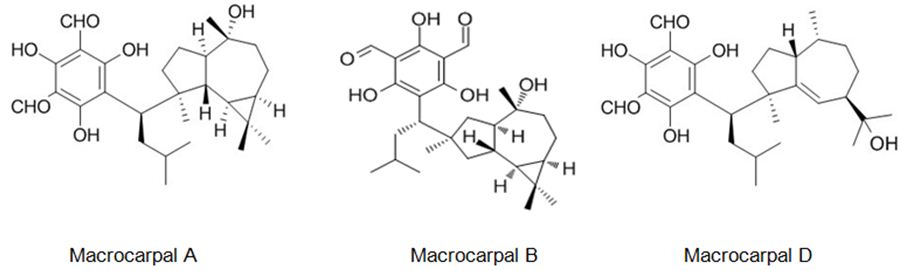

The six new pairs of bibenzyl-based meroterpenoid enantiomers, (±)-rasumatranin A-D (1-4) and (±)-radulanin M and N (5 and 6), and six known compounds have been isolated from the adnascent Chinese liverwort: Radula sumatrana. Cytotoxicity tests of the obtained compounds have exhibited that 6-hydroxy-3-methyl-8-phenylethylbenzo[b]oxepin-5-one (8) showed effect against the human cancer cell lines MCF-7, PC-3, and SMMC-7721, with IC50 values of 3.86, 6.60, and 3.58 μM, in order, and induced MCF-7 cell death through a mitochondria-mediated apoptosis pathway [99]. Lee et. al. have investigated the cytotoxicity of the brown alga Sargassum siliquastrum on human cancer cells (AGS, HT-29, HT-1080, and MCF-7). Bioassay-guided fractionation of the crude extracts has demonstrated that the 85% aqueous methanol (MeOH) fraction was the most toxic. Seven known meroterpenoids (1-7) have been obtained from this cytotoxic fraction. Each compound has been tested for its cytotoxic effect on human cancer cells. Compounds 1, 2, and 4 have shown vigorous cytotoxicity against AGS, HT-29, and HT-1080 cell lines, with IC50 values varying from 0.5 to 5.7 μg/mL [100]. The six new meroterpenoids, diplomeroterpenoids A-F, two new chalcone-lignoids, diplochalcolins A and B, and 13 well-known compounds have been isolated from the root extract of Mimosa diplotricha. diplomeroterpenoids A has exerted antiproliferative activity against human hepatoblastoma HepG2 cells with a GI50 value of approximately 8.6 μM [101]. The last-mentioned research example from plant source belongs to Jin et. al. They have isolated ten new formyl-phloroglucinol-terpene meroterpenoids, eucalypglobulusals A-J (1-10), and 10 known analogs were isolated from E. globulus fruit Eucalypglobulusal F has shown cytotoxicity against the human acute lymphoblastic cell line (CCRF-CEM) with an IC50 value of 3.3 μM, while eucalypglobulusal A, eucarobustol C, macrocarpal A, macrocarpal B, and macrocarpal D (Figure 20) have exerted DNA topoisomerase I (Top1) inhibition. The compounds: eucalypglobulusal A and macrocarpal A, acted as Top1 catalytic inhibitors and delayed Top1 poison-mediated DNA double-strand damage [102].

Figure 20: The molecular structure of Macrocarpal A [103], B [104], D [105].

The next three examples will be on the meroterpenes obtained from plant-related fungi. Liang et al. have studied on the secondary metabolites of the endophytic fungus Guignardia mangiferae from Smilax glabra and their antitumor effects. Twelve compounds have been isolated from the extract of 100 L liquid fermented broth and ten of them were elucidated as 15-hydroxyl tricycloalternarene 5b (1), guignardiaene D (2), guignardiaene C (3), guignardone A (4), guignardone B (5), 3-(4-methyl phenoxy) propanoic acid (6), nonane-2,4-diol (7), ergosterol (8), tyrosol (9), and p-hydroxybenzaldehyde (10). The inhibitory activity of compounds 1-7 on SF-268, MCF-7, and NCI-H460 cell lines was examined in vitro by SRB. The meroterpenes 1-5 exerted inhibitory effects on SF-268, while compounds. 6 and 7 showed inhibitory effects on MCF-7 selectively [106]. Long et. al. have obtained eleven new meroterpenoids, bipolahydroquinones A-C, cochlioquinones I-N, isocochlioquinones F, and G, along with 6 familiar ones from an endophytic fungus Bipolaris sp. L1-2 from Lycium barbarum. Bipolahydroquinone C, cochlioquinone I and cochlioquinones K-M have exhibited cytotoxicity against NCI-H226 and(or) MDA-MB-231 with IC50values ranging 5.5-9.5 μM [107].

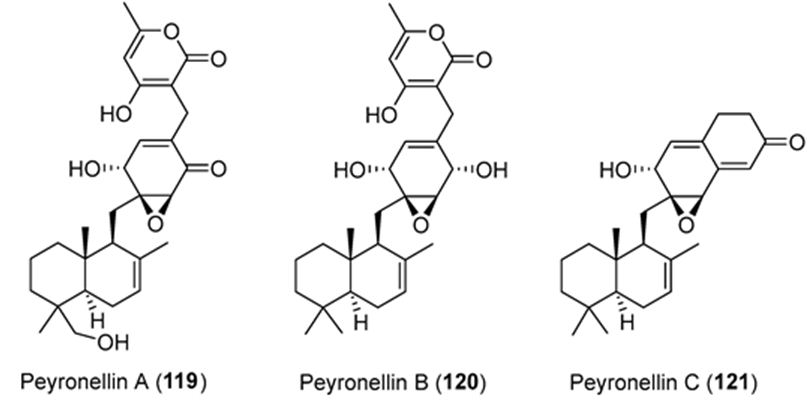

Li et. al. have isolated three uncommon polyketide-sesquiterpene metabolites peyronellins A-C (1-3) (Figure 21), together with the new epoxyphomalin analog 11-dehydroxy epoxyphomalin A (4), from the endophytic fungus Peyronellaea coffeae-arabicae FT238, which was obtained from the native Hawaiian plant Pritchardia lowreyana. Compound 4 showed an antiproliferative effect with an IC50 of 0.5 μM against OVCAR3, and it also powerfully inhibited Stat3 at 5 μM [108].

Figure 21: The molecular structure of peyronellins A-C [109].

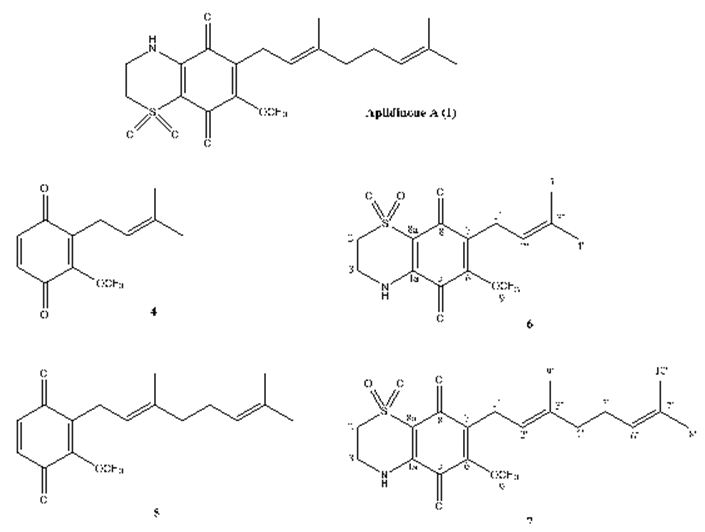

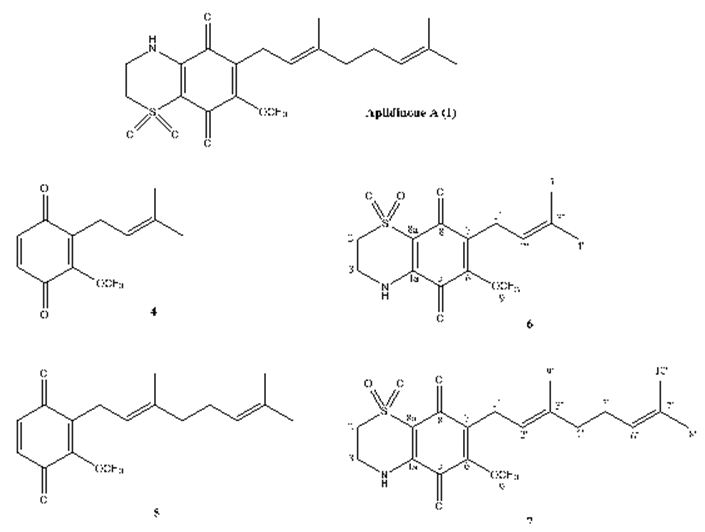

The meroterpenes isolated from marine sources are another subject that must be pointed out. In the first example study, Imperatore et. al. have reported the synthesis of two quinones: 2-methoxy-3-(3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl)cyclohexa-2,5-diene-1,4-dione and (E)-2-(3,7-dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-yl)-3-methoxycyclohexa-2,5-diene-1,4-dione and of their corresponding dioxothiazine fused quinones: 6-methoxy-7-(3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[b][1,4]thiazine-5,8- dione-1,1-dioxide and (E)-7-(3,7-dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-yl)-6-methoxy-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[b][1,4]thiazine-5,8-dione-1,1-dioxide inspired to the marine natural product aplidinone A (1), a geranylquinone displaying the 1,1-dioxo-1,4-thiazine ring isolated from the ascidian Aplidium conicum. The potential effects on viability and proliferation in three diverse human cancer cell lines, breast adenocarcinoma (MCF-7), pancreas adenocarcinoma (Bx-PC3) and, bone osteosarcoma (MG-63), have been searched. The methoxylated geranylquinone exhibited the highest antiproliferative effect showing akin toxicity in all three cell lines analyzed. In an interesting way, deeper research has highlighted a cytostatic effect of quinone 5 traceable to a G0/G1 cell-cycle arrest in BxPC-3 cells after 24 h treatment. (Figure 22) [110].

Figure 22: The molecular structure of aplidinone A and of synthetic analogs [110].

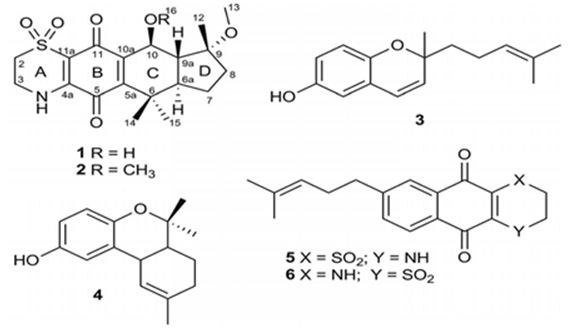

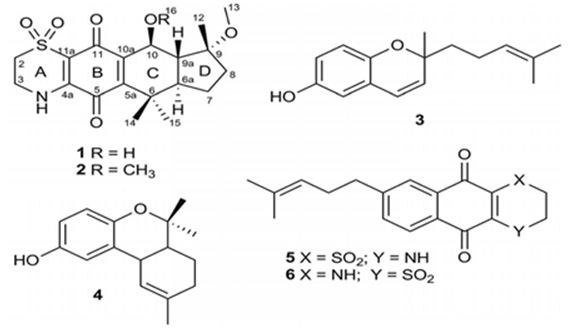

The previous A. Conicum study belonged to the same research group is on totally natural product isolation of A. Conicum. Menna et. al. have searched this marine source, and resulted in the isolation of two new meroterpenes, the conithiaquinones A (1) and B (2), in addition to two previously published chromenols (3 and 4) and conicaquinones (5 and 6) (Figure 23). Both conithiaquinones A and B exhibited significant activities on the growth and viability of cells, with 1 showing fascinating cytotoxicity against human breast cancer cells [111].

Figure 23: The molecular structure of conithiaquinones A (1) and B (2), two previously published chromenols (3 and 4) and conicaquinones (5 and 6) [111].

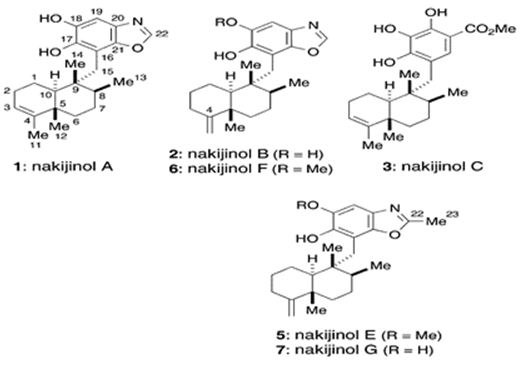

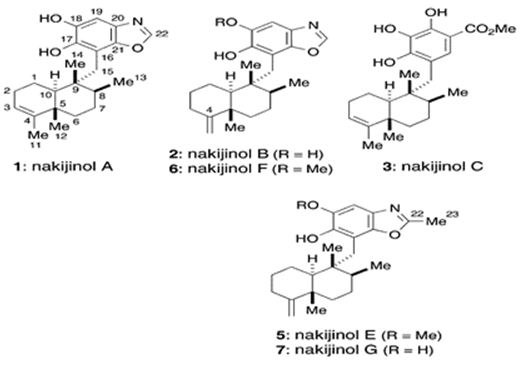

Additionally, marine meroterpenes from sponges have anticancer activity. Li et. al. have isolated five new sesquiterpene hydroquinones, dactylospongins A-D (1-4) and 19-O-methylpelorol (10), four new sesquiterpene quinones too: melemeleones C-E (6-8) and dysidaminone N (9) from the marine sponge Dactylospongia sp. collected from the South China Sea, along with five known analogs, ent-melemeleone B (5), pelorol (11), 17-O-acetylavarol (12), 20-O-acetylavarol (13), and 20-O-acetylneoavarol (14). 19-O-methylpelorol (10) showed cytotoxicity against lung cancer PC-9 cell lines with an IC50 value of 9.2 μM [112]. Three new meroterpenoids, hyrtiolacton A (I), nakijinol F, and nakijinol G, along with 3 known ones, nakijinol B, nakijinol E, and dactyloquinone A, have been isolated and elucidated from a Hyrtios sp. marine sponge picked up from the South China Sea. These compounds have been tested for their protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP1B) inhibitory and cytotoxic effects. Nakijinol G exerted PTP1B inhibitory activity with an IC50 value of 4.8 μM but no cytotoxicity against 4 human cancer cell lines [113] (Figure 24).

Figure 24: The molecular structure of nakijinols [114].

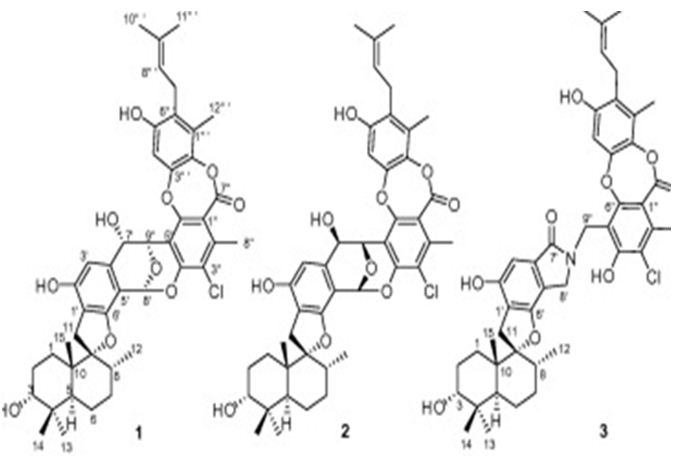

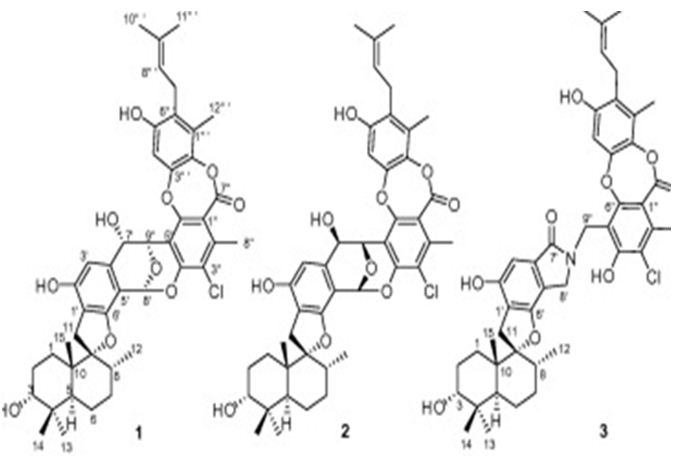

The next two research study is about the meroterpenes from marine-related fungi. Three phenylspirodrimane-based meroterpenoids with novel scaffolds, namely chartarolides A(I)-C, have been isolated from a sponge (Niphates recondite) related fungus Stachybotrys chartarum WGC-25C-6. Chartarolides A-C (Figure 25) have shown considerable cytotoxic effects against a panel of human tumor cell lines and exhibited strong inhibitory activities against the human tumor- associated protein kinases of FGFR3, IGF1R, PDGFRb, and TrKB [115].

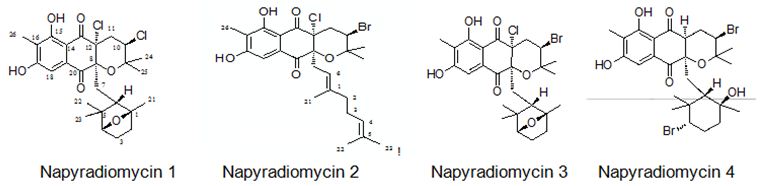

Farnaes et. al. have made microbial production, isolation, and structure elucidation of four new napyradiomycin congeners (I-IV) from marine-originated actinomycete. Utilizing fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis, napyradiomycins 1-4 (Figure 26) have detected to induce apoptosis in the colon adenocarcinoma cell line HCT-116, displaying the feasibility of a specific biochemical target for this group of cytotoxins [116].

Figure 25: The molecular structure of Chartarolides A-C (1-3) [115].

Figure 26: The molecular structure of napyradiomycins 1-4 [116].

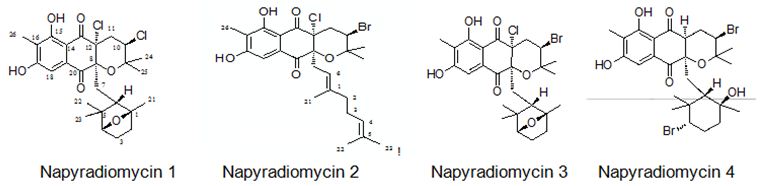

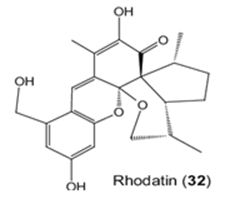

The study of Sandargo et. al. is to the mushroom: Rhodotus palmatus. They have isolated Rhodatin (1) (Figure 27), a meroterpenoid having a unique pentacyclic scaffold with both spiro and spiroketal centers, and five unprecedented acorane-type sesquiterpenoids, named rhodocoranes A-E (2-6, respectively), are the first natural products isolated from the basidiomycete Rhodotus palmatus. Rhodatin powerfully has prevented the hepatitis C virus, while 4 has shown cytotoxicity and selective antifungal activity [117].

Figure 27: The molecular structure of Rhodatin [118].

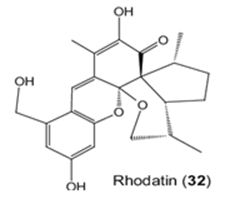

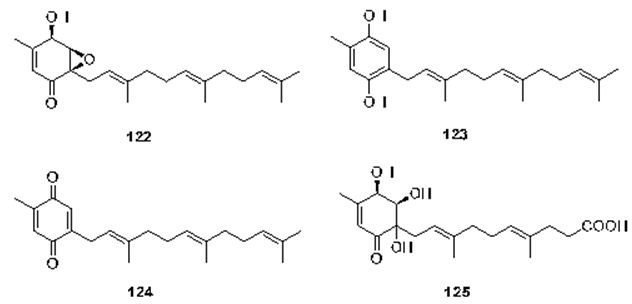

The last chapter is dealing with the microorganism sourced-meroterpenes. In the review written by Liu et al. It has been mentioned that terpene-quinone and -hydroquinone is the major bioactive members since they produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) [119]. Three quinone- and hydroquinone-type meroterpenes produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) [120]. Three quinone- and hydroquinone-type meroterpenes (122-124) (Figure 28) were obtained from a marine-derived Penicillium sp. Compounds 122 and 123 exerted considerable cytotoxicity against five cancer cell lines (A549, SKOV-3 (human ovary adenocarcinoma), SKMEL-2 (human skin cancer), XF498 (human CNS cancer), and HCT15 (human colon cancer)) with IC50 values in the range of 3-10 μg/mL, whereas compound 124 had IC50 values varying from 20 to 40 μg/mL (doxorubicin was used as a positive control with IC50 values of 0.02~0.8 μg/mL). These results prove that the quinone form prone to be less cytotoxic [121]. Penicillone A (125) (Figure 28), isolated from marine-derived Penicillium sp. F11. contains a carboxylic acid group in the place of the isoprenyl tail, which brought on mild cytotoxicity against fibrosarcoma (HT1080) and human nasopharyngeal carcinoma (Cne2) cell lines (IC50 = 45.8 and 46.2 μM, respectively) [121,122].

Figure 28: The molecular structure of compounds 122-125 [122].

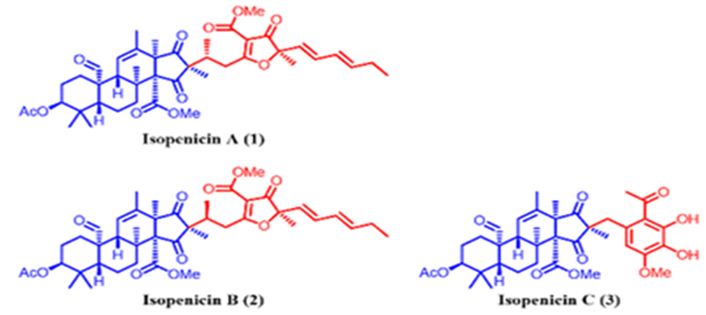

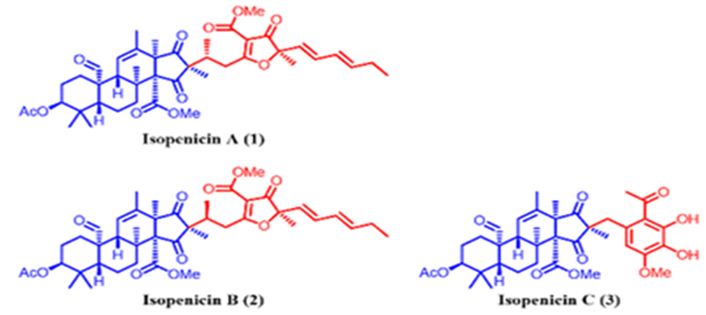

The Wnt-β-catenin signaling pathway plays a significant role in the regulation, differentiation, proliferation, and cellular death processes; therefore, modifications in this pathway are caused to numerous abnormalities of development, growth, and homeostasis in animal organisms. Wnt proteins contain a various family of secretion glycoproteins which join to Frizzled receptors and Low-Density Lipoprotein receptor-related Protein, to stabilize the crucial β-catenin protein, and to commence a complex signaling cascade, which is associated to multiple nucleocytoplasmatic systems. Modifications in the canonical Wnt-β-catenin signaling pathway have been related to variations in many proteins taking part in this route, or with activation/ inactivation of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, which clarify different processes of tumorigenesis, in addition to several malformations and human diseases. There are relations between the Wnt-β-catenin signaling pathway with various neoplastic processes, and its application can be used in the diagnosis and prognosis of cancer [123]. Tang et al. have isolated isopenicins A-C (1-3) (Figure 29), three novel meroterpenoids bearing two types of uncommon terpenoid-polyketide hybrid skeletons, from the cultures of Penicillium sp. sh18. The inhibitory effects of these compounds on the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway have been examined, and 1 has been determined as a potent inhibitor of the Wnt signaling pathway [124].

Figure 29: The molecular structure of isopenicins A-C [124].

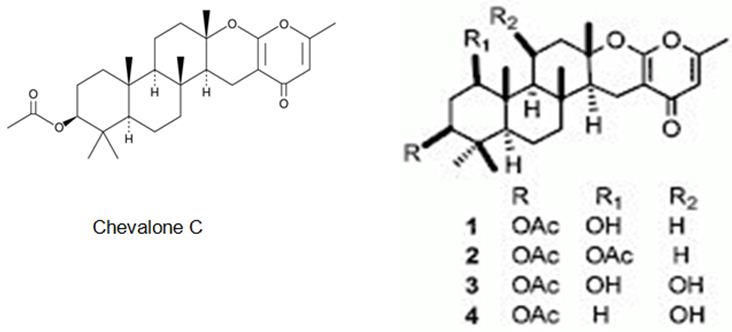

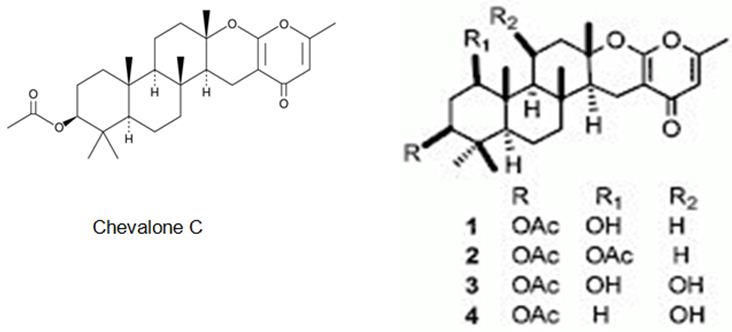

The latter two studies are referring to the meroterpenes obtained form two different fungus species of Neosartorya sp. Rajachan et. al. have isolated four meroterpenoids, 1-hydroxychevalone C, 1-acetoxychevalone C, 1,11-dihydroxychevalone C, and 11-hydroxychevalone C and 2 ester epimers, 2S,4S-spinosate and 2S,4R-spinosate, along with 7 known compounds, chevalones B, C (Figure 30), and E, tryptoquivaline, nortryptoquivaline, tryptoquivaline L, and quinadoline A from the fungus Neosartorya spinosa. 1-hydroxychevalone C, 1-acetoxychevalone C, 1,11-dihydroxychevalone C, and quinadoline A exhibited cytotoxicity against KB and NCI-H187 cancer cell lines with IC50 values in the range of 32.7-103.3 μM [125].

Figure 30: The molecular structure of Chevalone C [126] and analogs [125].

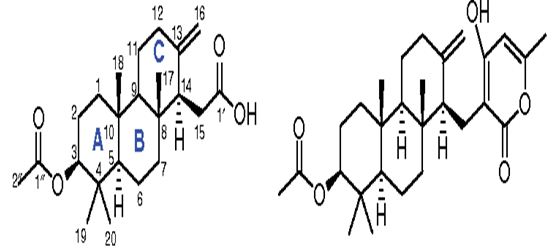

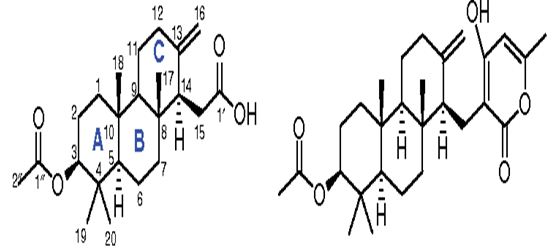

A new meroterpenoid, named tatenoic acid (I) (Figure 31) from have been isolated the fungus Neosartorya tatenoi KKU-2NK23, together with five common compounds, aszonapyrones A (Figure 31) and B (2 and 3), aszonalenin (4), ergosterol (5) and D-mannitol (6). Aszonapyrone A (Figure 31), a known meroterpene, has exerted cytotoxicity against two cancer cell lines, NCI-H187 and KB [127-129].

Figure 31: The molecular structure of Tatenoic acid and Aszonapyrone A [127].

Conclusion

Meroterpenes are pharmacologically important compounds because of providing a wide structure variability and depending on it having a huge bioactivity spectrum. This review has been focused on their anticancer activities and presented 23 anticancer activity studies of meroterpenes obtained from different sources. The anticancer activity is the power of natural and synthetic or biological and chemical agents to reverse, withhold, or block carcinogenic progression [128]. According to our literature survey, the three most effective meroterpene studies have been determined. One is about the meroterpenes isolated from the brown alga Sargassum siliquastrum: Sargachromanol E, D, and P have exerted strong cytotoxicity against AGS (gastric cancer cells), HT-29 (colorectal adenocarcinoma cancer cell), and HT-1080 (human fibrosarcoma cells) cell lines, with IC50 values varying from 0.5 to 5.7 μg/mL [100]. The other most effective meroterpene is Eucalypglobulusal F, which is one of the new formyl-phloroglucinol-terpene meroterpenoid isolated from E. globulus fruit, has shown cytotoxicity against the human acute lymphoblastic cell line (CCRF-CEM) with an IC50 value of 3.3 μM [89]. Besides, the last one is the new epoxyphomalin analog 11-dehydroxy epoxyphomalin A (4), from the endophytic fungus Peyronellaea coffeae-arabicae FT238, which was obtained from the native Hawaiian plant Pritchardia lowreyana showed a strong antiproliferative effect with an IC50 of 0.5 μM against OVCAR3 (Ovarian carsinoma cells) [102]. As a result, meroterpenes have potential candidates as an anticancer drug. Also, the structure of naturally isolated meroterpenes has a moderate anticancer activity that can easliy be modified by semi-synthetic ways due to their simple structures comparing to other natural compounds such as triterpenes or phenolic compounds.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Wu R, Le Z, Wang Z, Tian S, Xue Y, Hyperjaponol H, et al. (2018) A New Bioactive Filicinic Acid-Based Meroterpenoid from Hypericum japonicum Thunb. ex Murray. Molecules [crossref]

- Gershenzon J, Dudareva N (2007) The function of terpene natural products in the natural World. Chem. Biol 3: 408-414. [crossref]

- Makkar F, Chakraborty K (2018) Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory oxygenated meroterpenoids from the thalli of red seaweed Kappaphycus alvarezii. Chem. Res 27: 2016-2026.

- Kuzuyama T, Biosynthetic studies on terpenoids produced by Streptomyces. (2017) J Antibiot 70: 811-818. [crossref]

- Luo XW, Chen CM, Li KL, Lin XP, Gao CH, et al. (2019) Sesquiterpenoids and meroterpenoids from a mangrove derived fungus Diaporthe sp. SCSIO 41011. Prod. Res 8: 1-7. [crossref]

- Parshikov IA, Netrusov AI, Sutherland JB (2012) Microbial trans- formation of antimalarial terpenoids. Biotechnol Adv 30: 1516-1523.

- Liebgott T, Miollan M, Berchadsky Y, Drieu K, Culcasi M, et al. (2000) Complementary cardioprotective effects of flavonoid metabolites and terpenoid constituents of Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761) during ischemia and reperfusion. Res. Cardiol 95: 368-377.

- Ebada SS, Lin WH, Proksch P (2010) Bioactive sesterterpenes and triterpenes from marine sponges: occurrence and pharmacological significance. Mar Drugs 8: 313-346. [crossref]

- Geris R, Simpson TJ (2009) Meroterpenoids produced by fungi. Prod. Rep 26: 1063-1094. [crossref]

- Li H, Sun W, Deng MC, Qi C, Chen H, et al. (2018) Asperversins A and B, Two Novel Meroterpenoids with an Unusual 5/6/6/6 Ring from the Marine-Derived Fungus Aspergillus versicolor. Drugs 16. [crossref]

- Kikuchi H, Kawai K, Nakashiro Y, Yonezawa T, Kawaji K, et al. (2019) Construction of a Meroterpenoid-Like Compounds Library Based on Diversity-Enhanced Extracts. Eur. J 25: 1106-1112.

- Zubìa E, MJ Ortega, Salvà J (2005) Natural products chemistry in marine ascidians of the genus Aplidium. Mini-Rev. Org. Chem 2: 389-399.

- Menna M, Aiello A, FD’Aniello, Imperatore C, Luciano P, et al. (2013) Conithiaquinones A and B, Tetracyclic Cytotoxic Meroterpenes from the Mediterranean Ascidian Aplidium conicum. J. Org. Chem 2013: 3241-3246.

- Matsuda Y, Abe I (2016) Biosynthesis of fungal meroterpenoids. Prod. Rep 33: 26-53.

- Morton RA (1958) Nature 182: 1764-1767.

- Fernholz E (1938) On the constitution of α-tocopherol. Am. Chem. Soc 60: 700-705.

- Moncrief JW, Lipscomb WN (1965) Structures of leurocristine (vincristine) and vincaleukoblastine. X-ray analysis of leurocristine methiodide. Am. Chem. Soc 87: 4963-4964. [crossref]

- Kaysser L, Bernhardt P, Nam SJ, Loesgen S, Ruby JG, et al. (2012) Merochlorins A–D, Cyclic Meroterpenoid Antibiotics Biosynthesized in Divergent Pathways with Vanadium-Dependent Chloroperoxidases. Am. Chem. Soc 134: 11988-11991. [crossref]

- Kaysser L, Bernhardt P, Nam SJ, Loesgen S, Ruby JG, et al. (2014) Correction to “Merochlorins A–D, Cyclic Meroterpenoid Antibiotics Biosynthesized in Divergent Pathways with Vanadium-Dependent Chloroperoxidases”. Am. Chem. Soc 136.

- Awakawa T, Zhang LH, Wakimoto T, Hoshino S, Mori T (2014) A Methyltransferase Initiates Terpene Cyclization in Teleocidin B Biosynthesis. Am. Chem. Soc 136: 9910-9913.

- Yin X, Yin X, Feng T, Z-H. Li Z-J. Dong Y. Li J. K. Liu (2013) Highly oxygenated meroterpenoids from fruiting bodies of the mushroom Tricholoma terreum. Nat. Prod 76:1365–1368.

- De los Reyes, Zbakh H, Motilva V, Zubίa E (2013) Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory meroterpenoids from the brown alga Cystoseira usneoides. Nat. Prod 76: 621-629. [crossref]

- Mamemura T, Tanaka N, Shibazaki A, Gonoi T, Kobayashi J (2011) Yojironibs A–D, meroterpenoids and prenylated acylphloroglucinols from Hypericum yojiroanum. Tetrahedron Lett 52: 3575-3578.

- Luo Q, Di L, Dai WF, Lu Q, Yan YM, et al. (2015) Applanatumin A, a new dimeric meroterpenoid from Ganoderma applanatum that displays antifibrotic activity. Lett 17: 1110-1113.

- Choi H, Hwang H, Chin J, Kim E, Lee J, et al. (2011) Tuberatolides, potent FXR antagonists from the Korean marine tunicate Botryllus tuberatus. Nat. Prod 74: 90-94.

- Tran DN, Cramer N (2014) Biomimetic synthesis of (+)-ledene, (+)-viridiflorol, (–)-palustrol, (+)-spathulenol, and psiguadial A, C, and D via the platform terpene (+)-bicyclogermacrene. Eur. J 20: 10654-10660. [crossref]

- Qin XJ, Yan H, Ni W, Yu MY, Khan A, et al. (2016) Cytotoxic Meroterpenoids with Rare Skeletons from Psidium guajava Cultivated in Temperate Zone. Rep 6.

- Cueto M, Macmillan JB, Jensen PR, Fenical W (2006) Tropolactones A-D, four meroterpenoids from a marine-derived fungus of the genus Phytochem 67.

- Chexal KK, Springer JP, Clardy J, RJCole, JW. Kirksey, et al. (1976) Austin a novel polyisoprenoid mycotoxin from Aspergillus ustus. Am. Chem. Soc 98.

- Hayashi H, Mukaihara M, Murao S, Arai M, Lee AY, Clardy J (1994) Acetoxydehydroaustin, a new bioactive compound, and related compound neoaustin from Penicillium sp. MG-11. Biotechnol. Biochem 58: 334-338.

- Santos RMG, Rodrigues E Filho (2002) Meroterpenes from Penicillium sp found in association with Melia azedarach. Phytochem

- Santos RMG, Rodrigues E Filho (2003) Structures of Meroterpenes Produced by Penicillium sp, an Endophytic Fungus Found Associated with Melia azedarach. Braz. Chem. Soc 14.

- Santos RMG, Rodrigues E Filho (2003) Further meroterpenes produced by Penicillium sp., an endophyte obtained from Melia azedarach. Naturforsch 58.

- Schü BTM rmann, Sallum WST, Takahashi JA (2010) Austin, dehydroaustin and other metabolites from Penicillium brasilianum. Nova 33: 1044-1046.

- Liu LY, Li ZH, Ding ZH, Dong ZJ, Li GT, et al. (2013) Meroterpenoid pigments from the basdiomycete Albatrellus ovinus. Nat. Prod 76.

- Liaw CC, Yang YL, Lin CK, Lee JC, Liao WY, et al. (2015) New Meroterpenoids from Aspergillus terreus with Inhibition of Cyclooxygenase-2 Expression. Lett 17 2330-2333.

- Wang B, Zhang Z, Guo L, Liu L (2016) New Cytotoxic Meroterpenoids from the Plant Endophytic Fungus Pestalotiopsis fici. Chim. Acta 99: 151-156.

- Kataoka S,Furutani S,Hirata K,Hayashi H,MatsudaK (2011) Three austin family compounds from Penicillium brasilianum exhibit selective blocking action on cockroach nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neurotoxicology 32: 123-129.

- Masi M, Nocera P, Reveglia P, Cimmino A, Evidente A (2018) Fungal Metabolites Antagonists towards Plant Pests and Human Pathogens: Structure-Activity Relationship Studies. Molecules

- El-Demerdash A, Kumla D, Kijjoa A (2020) Chemical Diversity and Biological Activities of Meroterpenoids from Marine Derived-Fungi: A Comprehensive Update. Drugs 18.

- http://www.chemspider.com/Chemical-Structure.34947476.html

- http://www.chemfaces.com/natural/Albatrelin-A-CFN89347.html

- http://www.chemfaces.com/natural/Albatrelin-C-CFN89310.html

- Fischbach MA, Walsh CT (2006) Assembly-line enzymology for polyketide and nonribosomal peptide antibiotics: Logic, machinery, and mechanisms. Rev 106: 3468-3496.

- Itoh T, Tokunaga K, Matsuda Y, Fujii I, Abe I, et al. (2010) Reconstitution of a fungal meroterpenoid biosynthesis reveals the involvement of a novel family of terpene cyclases. Chem 2: 858-864.

- Macias FA, Varela RM, Simonet AM, Cutler HG, Cutler SJ, et al. (2000) Novel bioactive breviane spiroditerpenoids from Penicillium brevicompactum Dierckx. Org. Chem 65: 9039-9046.

- Zhang YC, Li C, Swenson DC, Gloer JB, Wicklow DT, Dowd PF (2003) Novel antiinsectan oxalicine alkaloids from two undescribed fungicolous Penicillium spp. Lett 5: 773-776. [crossref]

- Guo CJ, Knox BP, Chiang YM, Lo HC, Sanchez JF, et al. (2012) Molecular Genetic Characterization of a Cluster in A. terreus for Biosynthesis of the Meroterpenoid Terretonin. Lett 14: 5684-5687. [crossref]

- Nakamura H, Matsuda Y, Abe I (2018) Unique chemistry of non-heme iron enzymes in fungal biosynthetic pathways. Prod. Rep 35: 633-645.

- Birch AJ (1967) Biosynthesis of polyketides and related compounds. Science 156: 202-206. [crossref]

- Sunazuka T, Ōmura S (2005) Total synthesis of α-pyrone meroterpenoids, novel bioactive microbial metabolites. Chem Rev 105: 4559-4580. [crossref]

- Ding BZ, Wang X, Huang Y, Liu W, Chen She Z (2016) Bioactive α-pyrone meroterpenoids from mangrove endophytic fungus Penicillium sp. Prod. Res 30: 2805-2812. [crossref]

- Macías FA, Carrera C, JCG Galindo (2014) Brevianes revisited. Rev 114: 2717-2732. [crossref]

- Li J, Li F, King Smith E (2020) Renata Merging chemoenzymatic and radical-based retrosynthetic logic for rapid and modular synthesis of oxidized meroterpenoids. Chem 12: 173-179.

- Tomoda H, Kim YK, Nishida H, Masuma R, Omura S (1994) Pyripyropenes, noval inhibitors of Acyl-CoA: cholesterol acyltransferase produced by Aspergillus fumigatus. I. Production, isolation and biological properties. Antibiot 47: 148-153. [crossref]

- Kim YK, Tomoda H, Nishida H, Sunazuka T, Obata R, et al. (1994) Pyripyropenes, noval inhibitors of Acyl-CoA: cholesterol acyltransferase produced by Aspergillus fumigatus. II. Structure elucidation of pyripyropenes A, B, C and D. J. Antibiot 47: 154-162. [crossref]

- Tomoda H, Tabata N, Yang DJ, Takayanagi H, Nishida H, et al. (1995) Pyripyropenes, noval ACAT inhibitors produced by Aspergillus fumigatus. III. Structure elucidation of pyripyropenes E to L. Antibiot 48: 495–503.

- Tomoda H, Tabata N, Yang DJ, Namatame I, Tanaka H, et al. (1996) Pyripyropenes, noval ACAT inhibitors produced by Aspergillus fumigatus. IV. Structure elucidation of pyripyropenes M to R. J. Antibiot 49: 292-298. [crossref]

- Prompanya C, Dethoup T, Bessa LJ, MMM Pinto, Gales L, et al. (2014) New isocoumarin derivatives and meroterpenoids from the marine sponge-associated fungus Aspergillus similanensis sp. nov. KUFA 0013. Drugs 12: 5160-5173. [crossref]

- Ding Z, Zhang L, Fu J, Che Q, Li D, et al. (2015) Phenylpyropenes E and F: new meroterpenes from the marine-derived fungus Penicillium concentricum ZLQ-69. Antibiot 68: 748-751.

- Fadli M, Aracil JM, Jeanty G, Banaigs B, Francisco C (1991) Novel meroterpenoids from Cystoseira mediterranea: Use of the crown-gall bioassay as a primary screen for lipophilic antineoplastic agents. Nat. Prod 54: 261-264. [crossref]

- Sheu JH, Su JH, Sung PJ, Wang GH, Dai CF (2004) Novel meroditerpenoid-related metabolites from the formosan soft coral Nephthea chabrolii. Nat. Prod 67: 2048-2052. [crossref]

- Mitome H, Nagasawa T, Miyaoka H, Yamada Y, RWM Van Soest (2002) Dactyloquinones C, D and E novel sesquiterpenoid quinones, from the Okinawan marine sponge, Dactylospongia elegans. Tetrahedron Lett 58: 1693-1996.

- Garrido L, Zubia E, Ortega MJ, Salva J (2002) New meroterpenoids from the ascidian Aplidium conicum. Nat. Prod 65: 1328-1331. [crossref]

- Shen YC, Chen CY, Kuo YH (2001) New sesquiterpene hydroquinones from a taiwanese marine sponge, Hippospongia metachromia. Nat. Prod 64: 801-803. [crossref]

- Aiello A, Fattorusso E, Luciano P, Menna M, Esposito G, et al. (2003) Conicaquinones A and B, two novel cytotoxic terpene quinones from the Mediterranean ascidian Aplidium conicum. J. Org. Chem 5: 898-900.

- De Menezes JE, FEA Machado, TLG Lemos, Silveira ER, Braz R Filho, et al. (2004) Sesquiterpenes and a Phenylpropanoid from Cordia trichotoma. Natur 59: 19-22.

- Marion F, Williams DE, Patrick BO, Hollander I, Mallon R, et al. (2006) Liphagal, a selective inhibitor of PI3 kinase α isolated from the sponge Aka coralliphaga: Structure elucidation and biomimetic synthesis. Org. Lett 8: 321-324.

- Williams DE, Telliez JB, Liu J, Tahir A, van R Soest, et al. (2004) Meroterpenoid MAPKAP (MK2) inhibitors isolated from the Indonesian marine sponge Acanthodendrilla sp. Nat. Prod 67: 2127-2129.

- Simon A Levert, Menniti C, Soulère L, Genevière AM, Barthomeuf C, et al. (2010) Marine Natural Meroterpenes: Synthesis and Antiproliferative Activity. Drugs 8: 347-358. [crossref]

- Iida M, Ooi T, Kito K, Yoshida S, Kanoh K, et al. (2008) Three new polyketide-terpenoid hybrids from Penicillium sp. Lett 10: 845-848. [crossref]

- Silva DE, Williams DE, Jayanetti DR, Centko RM, Patrick BO, et al. (2011) Dhilirolides A-D, meroterpenoids produced in culture by the fruit-infecting fungus Penicillium purpurogenum collected in Sri Lanka. Lett 13: 1174-1177.

- Qi B, Liu X, Mo T, Zhu Z, Li J, et al. (2017) 3,5-Dimethylorsellinic acid derived meroterpenoids from Penicillium chrysogenum MT-12, an endophytic fungus isolated from Huperzia serrata. Nat. Prod 80: 2699-2707.

- Lo HC, Entwistle R, Guo CJ, Ahuja M, Szewczyk E, et al. (2012) Two separate gene clusters encode the biosynthetic pathway for the meroterpenoids austinol and dehydroaustinol in Aspergillus nidulans. Am. Chem. Soc 134: 4709-4720.

- Matsuda Y, Iwabuchi T, Fujimoto T, Awakawa T, Nakashima Y, et al. (2016) Discovery of key dioxygenases that diverged the paraherquonin and acetoxydehydroaustin pathways in Penicillium brasilianum. Am. Chem. Soc 138: 12671-12677. [crossref]

- Mori T, T. Iwabuchi, S. Hoshino, H. Wang, Y. Matsuda, et al. (2017) Molecular basis for the unusual ring reconstruction in fungal meroterpenoid biogenesis. Chem. Biol 13: 1066-1073. [crossref]

- Nielsen KF, Dalsgaard PW, Smedsgaard J, Larsen TO, Andrastins AD (2005) Penicillium roqueforti metabolites consistently produced in blue-mold-ripened cheese. Agric. Food Chem 53: 2908-2913. [crossref]

- Matsuda Y, Iwabuchi T, Wakimoto T, Awakawa T, Abe I (2015) Uncovering the unusual D-ring construction in terretonin biosynthesis by collaboration of a multifunctional cytochrome P450 and a unique isomerase. Am. Chem. Soc 137: 3393-3401.

- Stierle DB, Stierle AA, Patacini B, McIntyre K, Girtsman T, et al. (2011) Berkeleyones and related meroterpenes from a deep water acid mine waste fungus that inhibit the production of interleukin 1-β from induced inflammasomes. Nat. Prod 74: 2273-2277. [crossref]

- Matsuda Y, Awakawa T, Wakimoto T, Abe I (2013) Spiro-ring formation is catalyzed by a multifunctional dioxygenase in austinol biosynthesis. Am. Chem. Soc 135: 10962-10965.

- Matsuda Y, Wakimoto W, Mori T, Awakawa T, Abe I (2014) Complete biosynthetic pathway of anditomin: nature’s sophisticated synthetic route to a complex fungal meroterpenoid. Am. Chem. Soc 136: 15326-15336.

- Okuyama E, Yamazaki M, Katsube Y (2008) Funigatonin, a new meroterpenoid from Aspergillus fumigatus. Tetrahedron Lett 25: 3233-3234.

- Rank C, Phipps RK, Harris P, Fristrup P, Larsen TO, et al. (2008) Novofumigatonin, a new orthoester meroterpenoid from Aspergillus novofumigatus. Lett 10: 401-404.

- Zhang Y, Li X, Shang Z, Li C, Ji N, et al. (2012) Meroterpenoid and diphenyl ether derivatives from Penicillium sp. MA-37, a fungus isolated from marine mangrove rhizospheric soil. Nat. Prod 75: 1888-1895. [crossref]

- Zhang J, Yuan B, Liu D, Gao S, Proksch P, et al. (2018) Brasilianoids A–F, New Meroterpenoids From the Sponge-Associated Fungus Penicillium brasilianum. Chem 6. [crossref]

- Skropeta D, Wei L (2014) Recent advances in deep-sea natural products. Prod. Rep 31: 999-1025. [crossref]

- Matsuda Y, Bai T, CBW Phippen, Nødvig CS, Kjærbølling I, et al. (2018) Novofumigatonin biosynthesis involves a non-heme iron-dependent endoperoxide isomerase for orthoester formation. Comm 9.

- Wu CZ, Cai XF, Dat NT, Hong SS, Han AR, et al. (2007) Bisbakuchiols A and B, novel dimeric meroterpenoids from Psoralea corylifolia. Tetrahedron Lett 48: 8861-8864.

- Madrid A, Cardile V, Gonzalez C, Montenegro I, Villena J, et al. (2015) Psoralea glandulosa as a potential source of anticancer agents for melanoma treatment. Int. J Mol. Sci 16: 7944-7959. [crossref]

- Rizzo LY, Longato GB, ALTG Ruiz, Tinti SV, Possenti A, et al. (2014) In Vitro, In Vivo and In Silico Analysis of the Anticancer and Estrogen-like Activity of Guava Leaf Extracts. Med. Chem 21: 2322-2330. [crossref]

- Chapman LM, Beck JC, Lacker CR, LWu, Reisman SE (2018) Evolution of a Strategy for the Enantioselective Total Synthesis of (+)-Psiguadial B. J. Org. Chem 83: 6066-6085.

- http://www.chemfaces.com/natural/Psidial-A-CFN99321.html

- Qin XJ, Yu Q, Yan H, Khan A, Feng MY, et al. (2017) Meroterpenoids with Antitumor Activities from Guava (Psidium guajava). J Agric. Food Chem 65: 4993-4999. [crossref]

- http://www.chemfaces.com/natural/Guajadial-B-CFN96065.html

- Gao Y, Lı GT, Lı Y, Haı P, Wang F, et al. (2013) Guajadials C-F, four unusual meroterpenoids from Psidium guajava. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect 3: 14-19.

- http://www.chemfaces.com/natural/Guajadial-F-CFN89478.html

- Wan H, Li J, Zhang K, Zou X, Ge L, et al. (2018) A new meroterpenoid functions as an anti-tumor agent in hepatoma cells by downregulating mTOR activation and inhibiting EMT. Sci. Rep 8: 1-11.

- Zhang J, He J, Cheng YC, Zhang PC, Yan Y, et al. (2019) Fischernolides A–D, four novel diterpene-based meroterpenoid scaffolds with antitumor activities from Euphorbia fischeriana. Chem. Front 6: 2312-318.

- Wang X, Li L, Zhu R, Zhang J, Zhou J, et al. (2017) Bibenzyl-Based Meroterpenoid Enantiomers from the Chinese Liverwort Radula sumatrana. J Nat Prod 80: 3143-3150.

- Lee JI, Kwak MK, Park HY, Seo Y (2013) Cytotoxicity of mero- terpenoids from Sargassum siliquastrum against human cancer cells. Prod. Comm 8: 431-432. [crossref]

- Chiou CT, Shen CC, Tsai TH, Chen YJ, Lin LC (2016) Meroterpenoids and Chalcone-Lignoids from the Roots of Mimosa diplotricha. J Nat. Prod 79: 2439-2445.

- Jin XJ, Yin LY, Yu Q, Liu H, Khan A, et al. (2018) Eucalypglobulusals A–J, Formyl-Phloroglucinol–Terpene Meroterpenoids from Eucalyptus globulus J. Nat. Prod 81: 2638-2646.

- http://www.chemfaces.com/natural/Macrocarpal-A-CFN99413.html

- https://vevostars.com/blog/cas-142698-60-0-macrocarpal-b/

- http://www.chemfaces.com/natural/Macrocarpal-D-CFN99471.html

- Liang F, Li D, Chen Y, Tao M, Zhang W, et al. (2012) Secondary metabolites of endophytic Guignardia mangiferae from Smilax glabra and their antitumor activities. Zhongcaoyao 43: 856-860.

- Long Y, Tang T, Wang LY, He B, Gao K (2019) Absolute Configuration and Biological Activities of Meroterpenoids from an Endophytic Fungus of Lycium barbarum. J. Nat. Prod 82: 2229-2237.

- Li CS, Ren G, B-J. Yang, G. Miklossy, J. Turkson, et al. (2016) Meroterpenoids with Antiproliferative Activity from a Hawaiian-Plant Associated Fungus Peyronellaea coffeae-arabicae Org. Lett 18: 2335-2338.

- Gao H, Li G, Lou HX (2018) Structural Diversity and Biological Activities of Novel Secondary Metabolites from Endophytes. Molecules

- Imperatore C, Casertano M, Luciano P, Aiello A, Menna M, et al. (2019) In Vitro Antiproliferative Evaluation of Synthetic Meroterpenes Inspired by Marine Natural Products. Drugs 17. [crossref]

- Menna M, Aiello A, D’Aniello F, Imperatore C, Luciano P, et al. (2013) Conithiaquinones A and B, Tetracyclic Cytotoxic Meroterpenes from the Mediterranean Ascidian Aplidium conicum. J. Org. Chem 16: 3241-3246.

- Li J, Yang F, Wang Z, Wu W, Liu L, et al. (2018) Unusual anti-inflammatory meroterpenoids from the marine sponge Dactylospongia sp. Org. Biomol. Chem 16: 6773-6782.

- Wang J, Mu FR, Jiao WH, Huang J, Hong LL, et al. (2017) Meroterpenoids with Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase 1B Inhibitory Activity from a Hyrtios sp. Marine Sponge. J Nat Prod 80: 2509-2514. [crossref]

- Takeda Y, Nakai K, Narita K, Katoh T (2018) A novel approach to sesquiterpenoid benzoxazole synthesis from marine sponges: nakijinols A, B and E–G. Org. Biomol. Chem 16: 3639-3647. [crossref]

- Liu D, Li Y, Li X, Cheng Z, Huang J, et al. (2017) Chartarolides A-C, novel meroterpenoids with antitumor activities. Tetrahedron Lett 58: 1826-1829.

- Farnaes L, Coufal NG, Kauffman CA, Rheingold AL, AGDi Pasquale (2014) Napyradiomycin derivatives, produced by a marine-derived actinomycete, illustrate cytotoxicity by induction of apoptosis. J. Nat. Prod 77: 15-21.

- Sandargo B, Michehl M, Praditya D, Steinmann E, Stadler M, et al. (2019) Antiviral Meroterpenoid Rhodatin and Sesquiterpenoids Rhodocoranes A–E from the Wrinkled Peach Mushroom, Rhodotus palmatus. Lett 21: 3286-3289.

- Hyde KD, JXu, Rapior S, Jeewon R, Lumyong S (2019) The amazing potential of fungi: 50 ways we can exploit fungi industrially. Fungal Diversity 97: 1-136.

- Menna M, Imperatore C, FD’Aniello, Aiello A (2013) Meroterpenes from Marine Invertebrates: Structures, Occurrence, and Ecological Implications. Drugs 11: 1602–1643.

- Li X, Choi HD, Kang JS, Lee CO, Son BW (2003) New polyoxygenated farnesylcyclohexenones, deacetoxyyanuthone A and its hydro derivative from the marine-derived fungus Penicillium sp. Nat. Prod 66: 1499-1500.

- Zhuang P, Tang XX, Yi ZW, Qiu YK, Wu ZJ (2012) Two new compounds from marine-derived fungus Penicillium sp. F11. Asian Nat. Prod. Res 14: 197-203.

- Liu S, Su M, Song SJ, Jung JH (2017) Marine-Derived Penicillium Species as Producers of Cytotoxic Metabolites. Drugs 15. [crossref]

- Ochoa-Hernández, Juárez-Vázquez CI, Rosales-Reynoso MA, Barros P-Núñez (2012) WNT-β-catenin signaling pathway and its relationship with cancer. Cır. Cır 80: 389-98. [crossref]

- Tang JW, Kong LM, Zu WY, Hu K, Li XN, et al. (2019) Isopenicins A-C: Two Types of Antitumor Meroterpenoids from the Plant Endophytic Fungus Penicillium sp. sh18. Org. Lett 21: 771-775. [crossref]

- Rajachan OA, Kanokmedhakul K, Sanmanoch W, Boonlue S, Hannongbua S, et al. (2016) Chevalone C analogues and globoscinic acid derivatives from the fungus Neosartorya spinosa KKU-1NK1. Phytochem 132: 68-75.

- https://www.caymanchem.com/product/25084

- Yim T, Kanokmedhakul K, Kanokmedhakul S, Sanmanoch W, Boonlue S (2014) A new meroterpenoid tatenoic acid from the fungus Neosartorya tatenoi KKU-2NK23. Prod. Res 28: 1847-1852. [crossref]

- Chanda S, Nagani KJ (2013) In vitro and in vivo Methods for Anticancer Activity Evaluation and Some Indian Medicinal Plants Possessing Anticancer Properties: An Overview. Phytochem 2: 140-152.

- Birringer M, Siems K, Maxones A, Frank J, Lorkowski S (2018) Natural 6-hydroxy chromanols and -chromenols: structural diversity, biosynthetic pathways and health implications. RSC Adv 8: 4803-4841.