Abstract

We present two cases of carotid blowout syndrome with a hemorrhagic shock treated with an endovascular approach. In the first case, the treatment was performed by a selective embolization, while in the other case, both embolization and positioning of a covered stent was performed in order to avoid bleeding of external carotid artery. These endovascular treatments allowed the resolution of bleeding and the survival of the patients. Unfortunately, both patients died six months after the procedure for the evolution of their neoplastic disease. The endovascular treatment of carotid blowout syndrome represents a valid therapeutic option to stop carotid bleeding, but it does not change the prognosis of the patients.

Keywords

Carotid blowout, Covered stent, Hemorrhage

Introduction

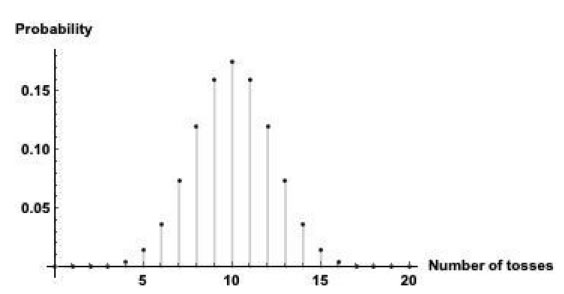

The incidence of significant hemorrhage in patients with Head and Neck cancer is approximately 6-14%, while terminal hemorrhages occur in approximately 3-12%of cases [1,2]. Head and neck cancer is the eighth most common cancer worldwide, and account for approximately 3% of all malignant tumors [3]. These are a broad category including diverse types originating from different anatomical structures like craniofacial bones, soft tissues, salivary glands, skin, and mucosal membranes with squamous cell carcinoma, which is the most common histological type (90%) [4]. the 5–years survival rate for head and neck cancers is around 60% [3]. Although chemotherapy and radiotherapy have improved the life expectancy of patients with head and neck cancers, they have also increased the risk of hemorrhage up to 7.6 times (4-6). These cancers are the most common cancers associated with hemorrhage, with an incidence rate ranging from 0.5-to 10% [2,6,7]. Carotid blowout syndrome is a rare, life threatening complication in patient with advanced head and neck cancer [8]. It refers to the ruptureof the carotid artery or its extracranial branches, usually secondary to tumor encasement or invasion. It can occur after good response to radical treatment, in which there is loss of tissue bulk surrounding and supporting an artery due to previous tumor invasion. Untreated carotid blowout syndrome is associated with mortality rates up to 60% and neurological morbidity of 40% [9]. Risk factors for carotid blowout syndrome in patients with head and neck cancer include post-radiotherapy necrosis, recurrent tumors, pharyngo-cutaneous fistulas, poor nutrition, diabetes mellitus and prolonged corticosteroid use [10]. When acute bleeding occurs from carotid blowout, treatment options are surgical ligation, endovascular embolization, or reconstruction with covered stents [11]. Surgery in a previously irradiated areamay be challenging, and emergent operative ligation can be associated with higher rate of major morbidity [9].

Cases Report

We reported two cases of carotid blowout syndrome with acute hemorrhage in patients with head and neck cancer.

Case 1

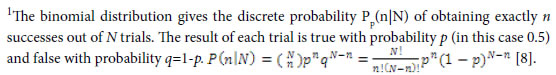

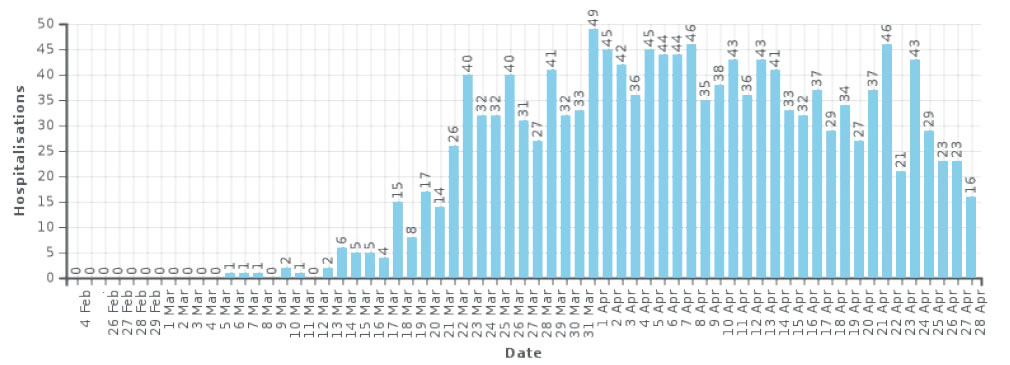

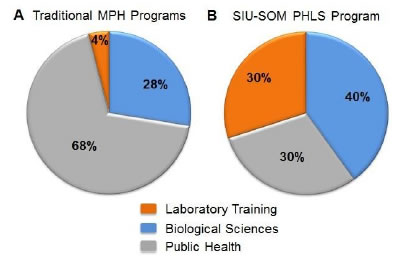

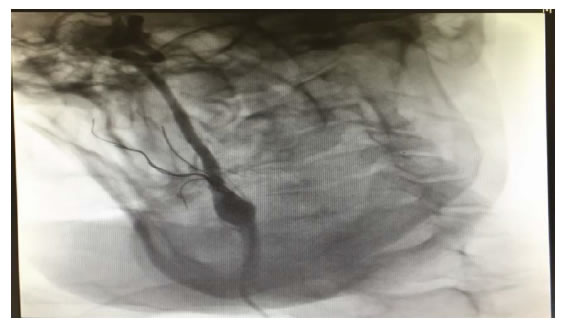

A 49-year old man was diagnosed in October 2017 with squamous carcinoma of the tongue. He had previous medical history and potus actively. After biopsy he was treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The patient received 3 cycles of chemotherapy with DCFwithout complication. CT imaging showed partial response. The case was discussed at a multi-disciplinary tumor board and concomitant radiotherapy and chemotherapy with platinum was initiated. After the treatment the patient refused examinations. Seven month later, the patient was hospitalized due to an aggravation of the clinical conditions. CT imaging documented a local recurrence of cancer. During the hospitalization a respiratory disorder was presented. Tracheostomy was urgently performed. Unfortunately, a massive hemorrhage appeared with hemodynamic instability and hemorrhagic shock. The patientafter intensive care, the patient underwent the endovascular treatment urgent with embolization of the external carotid artery and its branches (Figure 1). There were no central neurological complications (Stroke ischemic or TIAs) and after 12 hours the bleeding ceased with restoration of a goodhaemodynamic compensation. There were no episodes of re-bleeding during the hospital stay. The patient was discharged and transferred to Hospice. The patient died after 6 months due to the progression of the neoplastic disease which led him to acute respiratory failure.

Figure 1. Endovascular treatment with embolization ECA and its branches.

Case 2

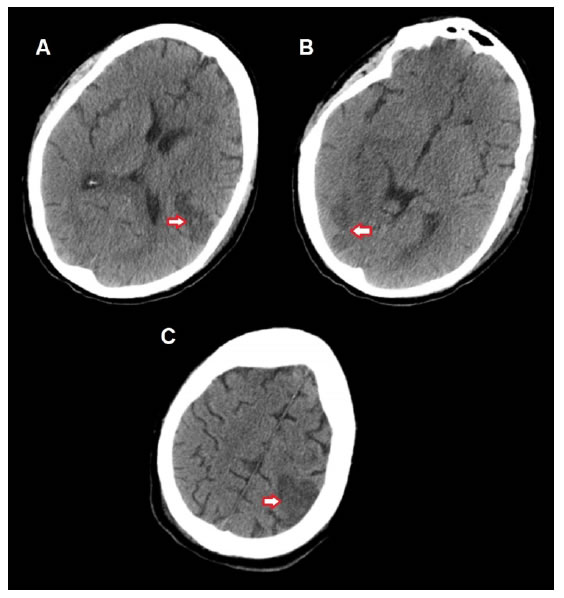

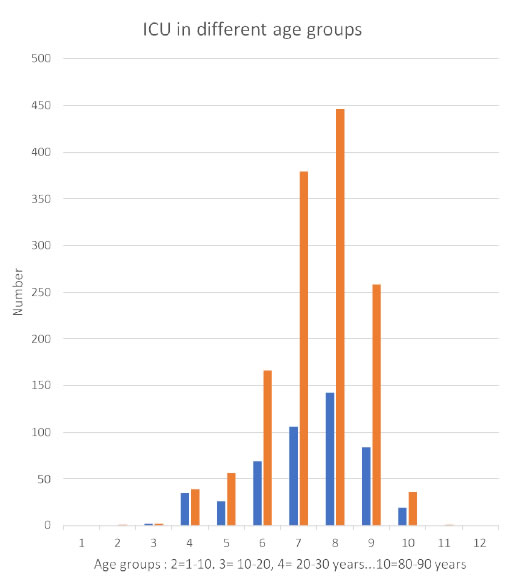

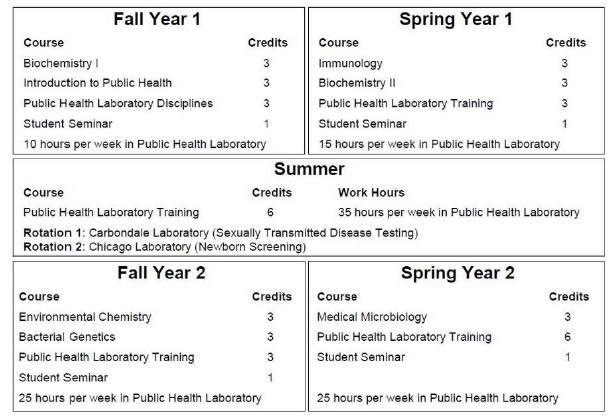

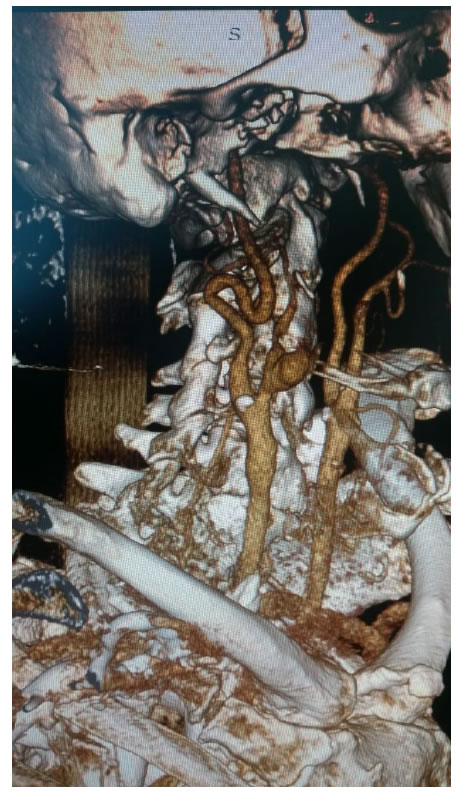

A 66-year-old patient underwent hemimandibulectomy with resection of the pterygoid and masseter muscles in July 2017. A histological examination showed a squamous carcinoma. After surgery, six cycles of chemotherapy comprising Cisplatin, 5-FUand Cetuximab was administered without complication. After 3 months a whole-Body 18F-FDG PET/CT showed lymph node progression. Second-line chemotherapy with the Carboplatin-Taxol was initiated without complication. After 3 cycles of chemotherapy, platinum-based radio-chemotherapy was started in December 2018. In January 2019 he showed rapid clinical progression of the disease and was admitted to our Department. During the hospitalization a massive hemorrhage appeared without hemodynamic instability. Therefore the patient underwent urgent CT of the neck which showed the presence of a pseudoaneurysm of the external carotid artery but a bleb of the common carotid artery immediately before the carotid bifurcation caused by neoplastic tissue sleeve around the bifurcation caused by neoplastic tissue sleeve around the bifurcation (Figure 2). Therefore it was necessary to undergo in urgency the patient not only to embolization of the pseudoaneurysm of the external carotid artery with controlled release spirals (Axium EV-3) but also to reconstruct the common carotid artery by positioning a stent coveredViabahn (Gore) between the common and internal carotid arteries in order to avoid the rupture of the vessel downstream of the pseudoaneurysm by the sleeve of neoplastic tissue present around (Figure 3). There were no central neurological complications (Stroke ischemic or TIAs) and the bleeding stopped immediately. The patient was immediately treated with dual anti-aggregation therapy to avoid intrastent thrombosis and there were not episodes of re-bleeding during the hospital stay. The patient was discharged and suspended chemo-radiation treatment and sent for supportive therapy. After 6 months the patient is still alive even though in progression with the neoplastic disease and did not present new episodes of bleeding or signs of capped stent infection.

Figure 2. Angio-CT vessels neck showing pseudoaneurysm ECA e neoplastic tissue around carotid bifurcation.

Figure 3. Endovascular treatment with embolization ECA and its branches e covered stent graft between ICA an CCA.

Discussion

Carotid Blowout Syndrome (CBS) is an uncommon complication of the advanced head and neck cancer. With continuing advancement and availability of endovascular techniques, an endovascular approach to be treatment of carotid blowout syndrome has been demonstrated tobe safe and has potential to control acute bleeding events and improve quality of life.The incidence has been estimated to be between 2% an 5% in patients receiving intervention for head and neck cancer, up to 10%in those receiving repeated courses of radiation. The morbidity of CBS has been–described, with perioperative mortality rate as high as 30% and a perioperative stroke rate as high as 15%, but remain highly variable owing to the rarty of the condition [12-13]. Both embolization and stentgrafts have been used in the management acute or impending carotid blowout. The most common locations or tumor were in the oral cavity and larynx and tho most common bleeding origin was the common carotid artery [14]. Both endovascular treatment were successful technically for immediate bleeding cessation in those with acute hemorrhage, but with a strokerate of around 11%. The risk of procedural stroke was lowest with embolizaion for CBS in the external carotid artery 1.7%, followed by stent graft of internal carotid artery / common carotid artery (ICA/CCA) 2,5% and then embolization of ICA/CCA 10,3% with post-treatment fatal re-bleeding occurring only 3,4% [11]. This compares favorably to the natural history of untreated carotid blowout syndrome, with associated risk of neurological morbidity up to 40% and mortality rate up to 60% [9].

Embolization of the ICA/CCa was generally preceded by the balloon test occlusion and stent graft was more likely to be performed in the presence of contralateral carotid artery occlusion, intolerance of balloon occlusion testing or angiographic evidence of an incomplete circle Willis [15]. Notably, despite the balloon test occlusion, the procedural stroke rate was higher after embolization of the ICA/CCA (10.4%) compared to the stent graft (2,5%). The rebreeding rate after stent graft was higher (31,9%) compared with embolization (9,1%), which may relate to the use of dual antiplatelet agents after stent grafts, which are typically not required after embolization . Importantly, 94% of patients treated for CBS involving the ICA/ACC did not experience fatal re-bleending, with no difference between embolisation and stent grafts [11]. Chang et all. Included 96 patients with CBSof which had lesion in the CCA, ICA, or bifucation: 38 patients were treated with embolization after passing a ballon occlusion test, and 18 patients underwent stent graft. Similarly, procedural stroke rates were similar (embolization 10.5%; stent graft 11,1%) and significantly higher rates of rebleeding in group stent graft 38.9% versus embolization 13,2%.

For embolization of CBS arising from branches of the External Carotid Artery, the procedural stroke rate was <2%. Although there were no fatal re-bleeds, another episode of bleeding did occur in 30% of the patients. This is similar to the largest case series by Chang. et all [15] in which35% of patients had rebleding [16]. The reason for rebleeding is not clear, and was not extractable from the literature. Potential reasonsbforrebleeding may relate to lack of identification of a target vessel, or retrograde flow from the rich collateral network of the external carotid artery when proximal occlusion of a target vessel is performed. Moreover, a new lesion of the ECA cranchmaya rise or the tumor bed could rebleed as the tumor continues to recruit neo-vascularity [16,17]. Moreover these was a higher rate of delayed stroke or TIA after stent grafts compared to embolization of the ICA/CCA. Although this coul relate to delayed stent thrombosis, the majority (two-third) of stent thrombosisi were asymptomatic. In addition, delayed stroke could relate to use post stent graft antiplatelet agents. The most common regimen was clopidogrelans aspirin foe 1-3 months, followed by life-long aspirin use. The antiplatelet regimens used are generally tailored to the clinical presentation, balancing the individual risk of rebleeding and ischemic stroke [11].

In the two cases treated, we first tried to stop the massive bleeding. In the first case where there was a hemorrhagic shock we immediately did the embolization of the external carotid artery not only of the main trunk but also of the branches of division, using spirals. In fact there was no neurological complication of ischemic type, nor new bleeding.in the second case there was no hemodynamic instability linked to bleeding which required to stop the bleeding immediately. Thus it was possible to perform a CT scan of the neck vessels which allowed to identify not only the origin of the bleeding but also the extent of the neoplastic disease. In fact, the simple embolization of the external carotid artery and its own pseudoaneurysm due to neoplastic infiltration of the wall would have temporarily solved the bleeding. In fact, the presence at CT of a neoplastic tissue sleeve around the carotid bifurcation with initial contour alteration would soon lead to a new bleeding. Therefore we changed surgical strategy proceeding both to the embolization of the pseudoanerysm of the external carotid artery and of the main trunk and to a reconstruction endovascular with the Stent graft covered Viabahn (gore) 7 x 10 mm, positioned between the internal carotid artery and the common carotid artery, covering the outer external carotid artery ostium and the neoplastic tissue sleeve around the carotid bifurcation. there was no neurological complication of ischemic type, nor new bleedingTherefore this work exposes a small and limited experience to only two cases but, however reliable, there were no complications and the patients survived the massive bleeding of Carotid Blowout Syndrome. important is the planning of endovascular strategy.

Conclusion

The endovascular approach appears to be, in our opinion, the gold standard for the treatment of bleeding from neoplasms, perhaps relapses, of head and neck after tumor removal with associated lymphadenectomy, or chemotherapy and subsequent radiotherapy. In fact, both the embolization of the external carotid artery or ICA / CCA, and the placement of a covered stent have proved and are reliable for the immediate control of the acute hemorrhage in progress. Complications can possibly be controlled if proper operative intervention is planned based on the location of the source of the bleeding and the extent of the neoplastic disease. For this reason it is fundamental to perform a CT scan of the neck vessels, if the patient’s haemodynamic conditions allow it, in order to evaluate the type of endovascular intervention to be carried out to not only stop bleeding but reduce the risk of perioperative complications.

References

- Ubogagu E, Harris DG (2012) Guideline for the management of terminal Hemorrhage in palliative care patients with advanced cancer discharged home for end-to-life care. BMJ Support Palliat Care2: 294-300. [Crossref]

- Harris DG, Noble SI (2009) Management of terminal hemorrhage in patients with advanced cancer; a systematic literature review. J Pain Symptom Manag38: 913-927. [Crossref]

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Elizabeth Ward (2010) Cancer Statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin60: 277-300. [Crossref]

- Pai SI, WestraWH (2009) Molecular Pathology of head and neck cancer: implications for diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Ann Rev. Pathol4: 49-70.[Crossref]

- Ringash J (2015) Survivorship and quality of life in head and neck cancer. J ClinOncol33: 3322-3327. [Crossref]

- Self EM, Bunpous J, Ziegler C, Liz Wilson, Kevin Potts (2013) Risk factors for hemorrahage after chemoradiation for oropahryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg139: 356-361. [Crossref]

- HessénSoderman AC, Ericson E, Hemlin C, ClaesHemlin, Elisabeth Hultcrantz, IngemarMånsson, et al. (2011) Reduced risk of primary postoperartivehemorrhage after tonsil surgery in Sweden: results from The National Tonsil Surgery Register in Swedwe covering more tha 10 years and 54696 operations. Laryngoscope121: 2322-2326. [Crossref]

- Upile T, Triaridis S, Kirland P, Daniel Archer, Adam Searle, et al. (2005) The management of carotid artery rupture. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol262: 555-560. [Crossref]

- Chaloupka JC, Putman CM, Citardi MJ, D A Ross, C T Sasaki (1996) Endovascular Therapy for the carotid blowout syndrome in head and neck surgical patientsdiagnostic and managerial considerations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 17: 843-852. [Crossref]

- McDonald MW, Moore MG, Johnstone PA (2012) Risk of carotid blowout after reirradiation of the head and neck: a systematic review. Int J RadiatOncol Bio Phys 82: 1083-1089. [Crossref]

- Wong DJY, Donaldson C, Lai LT, Andrew Coleman, Charles Giddings,et al. (2017) Safety and effectiveness of endovascular embolization or stent-graft reconstruction for treatment of acute carotid blowout syndrome in patients with head and neck cancer: case series and systematic review of observational studies. Head & Neck40:846-854. [Crossref]

- Cohen J, Rad I (2004) Contemporary Management of carotid blowout. CurrOpinOtolaryngol Head Neck Surg 12:110-115. [Crossref]

- Morrisey DD, Andersen PE, Nesbit GM, S L Barnwell, E C Everts, et al. (1997) Endovascular management of hemorrhage in patients with head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg123: 15-9. [Crossref]

- Liang NL, Guedes BD, Duvvuri U, Michael J Singh, Rabih A Chaer,et al. (2016) Outcomes of interventions for carotid blowout syndromein patients with head and neck cancer.J Vascsurg63:1525-1530. [Crossref]

- Lesley WS, Chaloupka JC, Weigele JB, SundeepMangla, Mohammad A Dogar(2003) Preliminary experience with endovascular reconstruction of the management of carotid blowout syndrome. AJNR AmJNeuroradiol 24: 975-981. [Crossref]

- Chang FC, Luo CB, Lirng JF, Chung-Jung Lin, Han-Jui Lee, et al. (2015) Endovascular management of post-irradiated carotid blowout syndrome. PLoS One 10: e0139821. [Crossref]

- Behzad SF, DongHlee, Ahmed Khalil, Sunil Abrol, Lucio Flores (2014) Carotid Blowout Syndrome: Endovascular management of acute Hemorrhage with Tapering Overlapped Covered Stents. Ann. VascSurg 28:1934.e7-11. [Crossref]