Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 diffuses quite easily among humans, causing a variety of symptoms from a mild flu to a fatal illness mostly involving the lungs and sometimes the kidneys or the heart, organs that express high concentration of the ACE2 viral receptor. No vaccine is available, although several are under scrutiny. From the therapeutic side, many different products are being tested, from antiviral to anti inflammatory drugs taken from the repertoire of other diseases, however with variable success. In fact, the death toll of this viral infection remains quite high. Containment of the infection is based on mechanical devices (goggles and masks) that shield the entrance doors of the virus (eyes, nose, mouth), and on tight social restrictions to limit the possibility of contact among people living in a community. Nonetheless, the virus apparently survives for hours on different surfaces and in droplets suspended in the air and dispersed by the micro particulate that is so abundant in industrialized towns, thus reaching further away from the originator, and tricking human defenses. In this situation, a possible complementary – however unspecific – approach to limit the infectivity of the virus could be based on a range of natural compounds which may interfere with the diffusion of the virus within the body, and increase the efficacy of the immune defenses of the organism. This is meant to be a non-toxic, preventive or adjuvant treatment so that in case of infection, the symptoms might not develop to full scale, giving the organism more time and strength to fight it.

Keywords

Covid-19, Computational chemistry, Drugs, Epidemiology, Food supplements, Probiotics, Therapy.

Introduction

The virus SARS-CoV-2 is the cause of the most recent pandemic of flu-like disease COVID-19. Italy has been among the European country most severely hit by the pandemy, with an amount of infected and dead patients even higher than the originator China. The facility of viral diffusion in Italy (but the rest of the world does not seem to behave much differently) and the relative inefficiency of containment measures and of the available drugs to treat Covid-19, has prompted us to figure out alternative and complementary possibilities to approach the diffusion of this viral pandemy, which might apply also to future epidemies. The treatment suggestions that follow are the result of such effort. The mechanism of infection by the SARS-CoV class of viruses apparently occurs via specific interactions between the SARS-CoV spike protein (S) and the host receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), which regulates both cross-species and human-to-human transmission of SARS-CoV [1]. Once the virus has gained entry into the human body, it starts spreading, usually through the respiratory tract, causing sympotms that can be mild, if it stays in the upper respiratory tract, or more severe such to be fatal to the host, if it reaches the lungs and the deep alveoli network [2]. In order to progress into the respiratory tract, the virus has to move against the inverse flow of the mucus, which is continuosly produced by the epithelial cells lining the airways and pushed by their cilia towards the larinx [3]. In this way inhaled pathogens and particulate matter trapped by the airway mucus can be removed by swallowing or coughing. This process is an important self-defense mechanism of the respiratory system and its failure may lead to chronic infections and impaired lung function [4].Furthermore, the virus has to survive to the immune surveillance of the host. Natural and adaptive immunity are alerted, and will start mounting an immune response to the invasive guest. A struggle develops between the speed of virus replication and diffusion, and the inflammatory response trying to contain it. Sometimes the inflammatory response gets out of control, and a cytokine storm may happen, adding further damage to the viral infection, causing acute lung injury and leading the patient to death [5, 6].

The infective process

The SARS-CoV-2 and its interactions

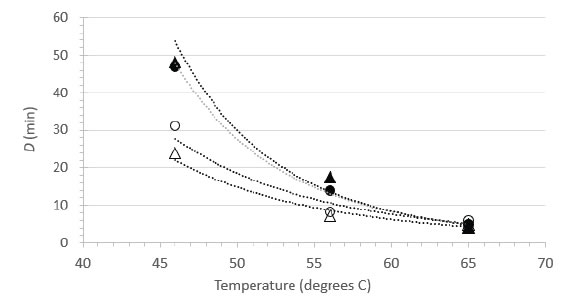

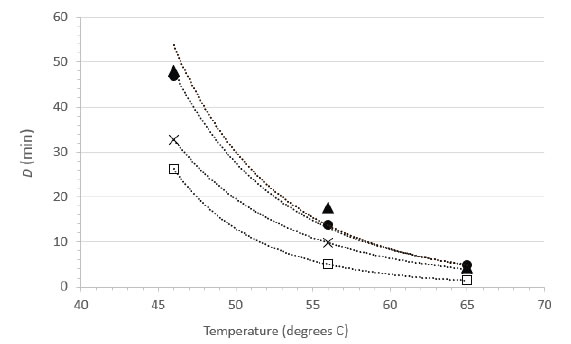

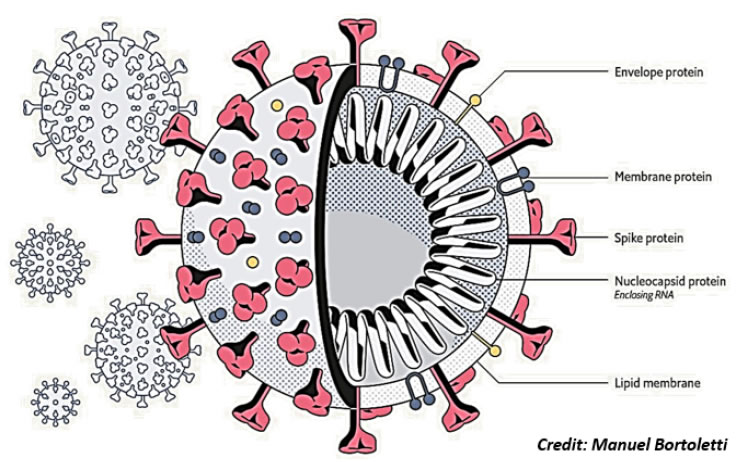

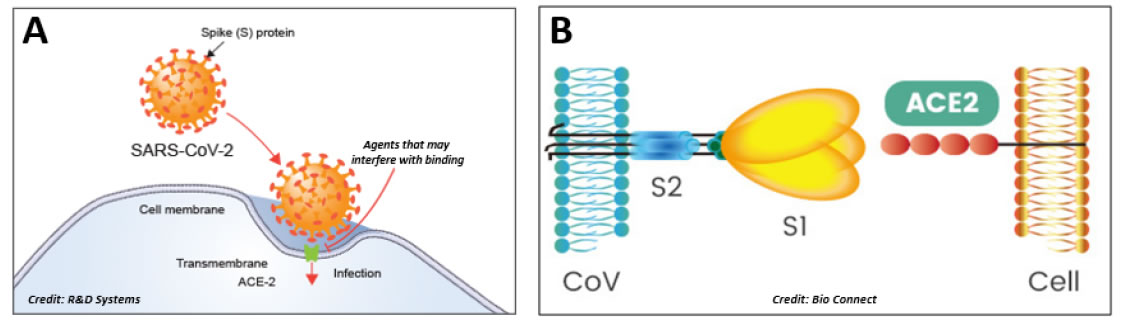

CoVs have a complex organization (Figure 1) containing four or five structural proteins mixed with some minor components that include nonstructural and host cell-derived proteins [7]. All viral particles display on their surface Spike (S), Envelope (E) and Membrane (M) structural proteins [8] (Insert Fig 1).

Figure 1. Virus structure. Schematic structure of a Corona Virus, with the surface proteins spike (S), membrane (M) and envelope (E). The nucleocapsid (N) protein stabilizing the single strand RNA molecule is shown inside.

These surface proteins interact with host cell membranes at the beginning of infection, and the S protein is responsible for the fusion process between viral and host membranes [9], thus defining tissue tropism and host range (Figure 2A). The S protein contains two subunits (Figure 2B): the S1 at the N-terminus has the receptor binding function and the S2 at the C-terminus confers the fusion activity [9]. Host cell proteases cleave the subunits from the S protein. Once the S1 has bound the host cell receptor followed by the uptake into a vesicle, then S2 works to bring in close proximity viral and cellular membranes so that fusion may occur [10] (Insert Fig 2 A & 2B).

Figure 2. Infection mechanism. A: The infective process of SARS-CoV-2. ACE-2 appears to be the host cell receptor responsible for mediating the Covid-19 infective process. B: The spike protein S contains two moieties, S1 and S2. The trimeric S1 moiety contains the receptor binding domain (RBD) responsible of the specific interaction with the ACE2 host cell receptor.

Entrance doors of the virus: an eye on the ocular tissue

While researchers are certain that Corona viruses (CoVs) spread through mucus and droplets expelled by coughing or sneezing, it is likely that the virus can also diffuse via other body fluids, such as tears. Since early 2000, CoVs infection was known to be associated with conjunctivitis and in 2004, CoV RNA has been detected for the first time in tears of SARS-CoV patients, suggesting the possibility of virus transmission through ocular tissues and tears [11]. How CoV eventually gets to the eye from infected droplets (directly, or through the nasolacrimal duct, or the lacrimal gland, etc) remains an unsolved problem. Infact, the end of SARS-CoV epidemic turned off the interest on possible involvement of the ocular tissue in virus infection. The recent SARS-CoV-2 epidemic and the similarity in the receptor that binds both SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV renewed much attention on research into ocular infection as a possible route of SARS-CoV-2 transmission [11,12]. Further investigations concluded that COVID-19 could be indeed transmitted through the ocular route, as suggested by SARS-CoV-2 isolation in the tears of a patient at Rome’s infectious-disease Spallanzani Hospital. The study recently published indicates that the eyes are not only an entrance door for the virus but also “a potential source of contagion” [13]. The additional finding that SARS-CoV-2 is present in conjunctival specimens [14, 15] and that ACE2 has been detected in different eye compartments [16-17] is indicative of the possibility that ocular tissues might represent a source of spread, particularly when higher viral loads are present at the acute stage of ocular complications.

Inflammation: a double edged sword

Once the virus has reached the airways, the first line of defense is the respiratory epithelium [18]. The human respiratory epithelial layer is made of ciliated cells intermingled by some secretory and basal cells. Secretory cells produce mucins and anti-microbial molecules. Ciliated cells generate a mucin flow helping the removal of foreign particles (micro-organisms included) and debris, sweeping mucus and trapped particles upwards and helping to expel them from the respiratory tract. Different immune cell types are resident in the epithelium, including T lymphocytes and dendritic cell populations acting as sentinel cells. Other immune cell populations including innate lymphoid cells and natural killer cells (NK) are found lining the epithelium. Alveolar macrophages are resident in the alveolar space. Recognition of invading SARS-CoV by intracellular sensors induces rapid production of antiviral interferons and other proinflammatory cytokines. In particular, when leukocytes recognize virus-infected cells or tissues damaged by the virus, these sentinels rapidly initiate an innate immune response that involves cellular activation, signaling cascades and the release of cytokines to guide leukocytes to mount an effective response. Among immune responses against SARS-CoV infection, activation of inflammation and host cell death are crucial in limiting viral infections, replication, and associated pathological damage. On the other hand, inflammatory cascade triggered by viral infection can exacerbate the pathological damage or contribute to viral clearance depending on the context of the infection [5]. There are multiple aspects of inflammation associated with viral infections. In particular, mechanisms underlying the excessive cytokine response deserve further investigations in order to develop strategies to minimize detrimental tissue damage associated with strong inflammation, while maximizing their beneficial anti-viral features.

Respiratory disease due to alveoli failure

When the infection reaches the respiratory tract, then the lining of the respiratory tree becomes injured thus causing an inflammatory state that may spread to the air sac – the gas exchange unit – which becomes unable to get enough oxygen from the blood stream and to efficiently release carbon dioxide. The first organism reaction is to activate the immune system, triggering an inflammatory response able to destroy the virus and limit its replication, however with the risk that an excessive inflammation (either in terms of intensity or duration) may exacerbate the pathological damage. Such mechanisms are very active and ready to respond in young and healthy individuals, but can be impaired in elderly people in which additional pathologies and a weakened immune system, often due to vitamin D deficiency, make it harder to fight the disease, thus accounting for the high number of deaths in elderlies [19]. Although comparably infected, pneumonia-induced death rate in men is higher than in women. This is in line with disproportional affection during additional epidemics caused by CoV. There are several factors that may confer more protection to women: stronger immune system, which, on the other hand, renders women more susceptible to autoimmune diseases, sex hormone estrogen, which appears to play a role in immunity, less prevalent strong smoking habits, less incidence of hypertension and diabetes to mention just a few differences between women and men [20]. In addition to the sex difference revealing that infection in males is more aggressive than in females, another question concerns children, which in fact contract the virus as often as adults, however developing much milder symptoms. Conversely, an inverse relationship has been noted with age, and the younger the child, the higher chance they have of winding up in severe or critical condition. (A. Balbarini, personal communication). Why COVID-19 affects children differently remains unknown although some hypotheses have been proposed. Children may have a more efficient and responsive immune system, and a better protection of the airways by an active production of mucins, rapidly flowing towards the larynx for secretion, all of which could be contributing to a milder disease. The fact that children are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection, but frequently do not develop a symptomatic disease, raises the possibility that children could be facilitators of viral transmission [21]. This whole, though synthetic, picture of the infection pathway indicates nonetheless the possible target mechanisms that should be tackled by drug molecules or by natural products to prevent or at least limit viral infections, including the one by the SARS-CoV-2: i. receptor binding; ii. virus diffusion; iii. inefficient or deranged immune reaction. We will describe now some of these approaches, with a major emphasis on non-pharmacologic ones, explaining their rationale in this context.

Pharmacological approach

Much effort is presently given to the characterization of some therapeutic compounds that could be potentially active against the currently emerging novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. New treatments are being added day by day and their list includes, among others, repurposed flu treatments, malaria treatments, failed ebola drugs, anti-HIV drug combination, immune suppressants and anti-hypertensive drugs. This paragraph is aimed to provide a summary of therapeutic compounds that show potential in fighting the SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Antiviral products

Scientists around the world are racing with time to find a cure for the COVID-19 pandemic. Characterization of the viral structure and physiology is critical to develop effective antiviral drugs. Presently, the virus capsid S and M proteins, the serine protease TMPRSS2 used for S protein maturation, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) necessary for virus replication and the cell receptor ACE2 are the primary targets. Among the antiviral drugs, Favipiravir or Avigan was developed in Japan as an anti-viral agent that inhibits the RdRp of RNA viruses. Its effects appear to improve the lung condition by preventing virus replication, thus shortening the time of virus infection. This drug has been approved as an experimental treatment for mild COVID-19 infections and has been tested with success in 340 individuals from Wuhan and Shenzhen. However a comprehensive picture about the mechanisms underlying its efficacy is still lacking [22]. Chloroquine (CQ) and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) are drugs approved for the treatment of malaria, and inflammatory autoimmune diseases like lupus an rheumatoid arthritis. CQ is a weak base that becomes entrapped in membrane-enclosed low pH organelles thus leading to an increase of lysosomal pH. SARS-CoV-2 entry into the cell requires a correct endocytic trafficking whose impairment, as after CQ administration, would interfere with viral infection [23]. Both CQ and its derivative HCQ are being used against COVID-19 and clinical trials are being organized both in U.S. and China. However, some attention against potential side effects including cardiac arrhythmias has been recently turned on [24]. Due to the severe side effects that can be caused by CQ, HCQ might be preferred, since it shows an antiviral effect comparable to that of CQ, and appears to be able to blunt the severe progression of COVID-19, by decreasing T cell activation, thus inhibiting the dangerous cytokine storm. Beside a safer clinical profile it is also suitable for pregnant patients [25]. Much attention has been recently raised about the efficacy of remdesivir, a drug formerly used against Ebola and now repurposed to conteract COVID-19 infection [26]. Remdesivir belongs to the class of nucleotide analogs known to display some antiviral activity against single stranded RNA viruses. Although used against some cases of the African Ebola epidemic, laboratory experiments with blood sample analysis have failed to demonstrate a correlation between drug assumption and drop in the concentration of viral particles. In addition, serious side effects restrict drug prescription only to severely affected CoVID-19 patients. The antiviral drug kaletra, a combination of lopinavir (LPV) and ritonavir (RTV), is used for the treatment and prevention of HIV/AIDS. Both compounds are protease inhibitors. In particular, RTV acts by slowing down the breakdown of LPV, but both components have been shown to interact with other medications against important diseases as for instance cardiovascular diseases. The antiviral activity of this drug combination has generated early excitement for its use in COVID-19 patients [27], although recent data from chinese patients failed to detect major benefits. In addition, the rather important side effects of this drug combination seems to complicate the possibility of its use although some studies are still ongoing to evaluate drug efficacy. Recently, combination of LPV/RTV with types I and II interferons (IFNbs) has been suggested to efficiently counteract both virus replication and host inflammatory responses [28]. In this respect, clinical trials have been launched to determine whether the combination of LPV/RTV and IFNbs could improve clinical outcomes in MERS-CoV infections (MIRACLE Trial in South Arabia) and in SARS-CoV-2 infections (ChiCTR2000029308 in China).

Anti inflammatory and immune-regulatory products

An interesting therapeutic alternative is to target the cellular components involved in the host inflammatory response to the infection that may trigger the cytokine outburst resulting in acute lung injury which can damage COVID-19 patients even more than the infection itself. Blocking the cellular toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) with specific antibodies that prevent the activation of NF-κB intracellular signaling is a possibility. The TL4 pathway leads to the production of inflammatory cytokines which activate the innate immune system. In this respect, sarilumab and tocilizumab used to treat rheumatoid arthritis are used to quiet the cytokine storm. They are IL-6 inhibitors, and work by blocking the inflammatory cell response to IL-6, thus preventing the inflammatory cascade triggered by its over-abundant release by inflammatory cells [28]. Another immune-active interesting drug, not yet in clinical trials for Covid-19, is Pidotimod. It is a peptide drug active on the stimulation and regulation of the cellular immune response [29]. Pidotimod has shown the ability to decrease the need for antibiotics during respiratory tract infections, increasing the production of immunoglobulins (IgA, IgM, IgG) and T-lymphocytes (CD3+, CD4+) endowed with immunomodulatory activity and involving both innate and adaptive immunity. In vitro studies have shown that Pidotimod triggers in immune cells higher expression of TLR2 and HLA-DR receptor molecules, stimulates dendritic cell maturation and T lymphocyte proliferation and differentiation, thus increasing their release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, as well as an increase of phagocytosis. All these activities are potentially useful for recurrent respiratory tract infections [30]. Its clinical efficacy in children with or without asthma, and in elderlies in terms of reduced reinfection rates and a lesser need for antibiotics has been reported [31, 32]. The overdrive of the immune system following virus infection can damage COVID-19 patients even more than the infection itself. In this respect, immunosuppresants (sarilumab and tocilizumab) used to treat rheumatoid arthritis are used to quiet the cytokine storm. They are IL-6 inhibitors, and work by blocking inflammatory cell response to IL-6, thus preventing the inflammatory cascade triggered by its over-abundant release by inflammatory cells [5, 33, 34].

Anti-hypertensive products

The fact that SARS-CoV-2 binds ACE2 receptor and that ACE2 receptor plays a critical role in regulating blood pressure has raised the possibility to use anti-hypertensive drugs such as losartan to protect target cells from virus infection. Losartan is an agiotensin II receptor antagonist and acts by reducing the response to angiotensin II, ultimately decreasing blood pressure by lowering vessel peripheral resistance and cardiac venous return. Blocking ACE2 receptors might possibly prevent the virus from infecting cells by locking the doorway to virus entrance. There are, however, conflicting opinions on the use of anti-hypertensive drugs against virus infection. Complicating things are the recent findings that losartan and other angiotensin II receptor blockers may actually stimulate ACE2 production, thus increasing the possibility of the virus to enter the cells [35]. Therefore, on the one hand ACE2 antagonists could compete with the binding of the virus spike protein, but on the other hand the increase of ACE2 expression stimulated by the antagonist drug could increase susceptibility to virus infection and spreding [36]. In this respect, hypertension has been considered a risk factor for SARS-CoV-2 infection and mortality [37, 38] and a Chinese study on cardiopatic patients affected by Covid-19 found a higher mortality risk among this cohort [39], and an Italian study on 355 patients dead for COVID-19 found that most of them had hypertension, thus associating their anti-hypertensive medication with their increased susceptibility (A. Balbarini, personal communication). All of the above medications were first developed years ago for different diseases. New drugs and vaccines are strongly and urgently needed. Their development strictly depends on basic research aimed to clearly identify and exploit the receptor binding domain (RBD) within the spike protein, that allows the fusion of viral and host membranes. Similarly to SARS-CoV, also the S spike coat protein of SARS-CoV-2 recognizes ACE2 as its host receptor. Therefore, univocal molecular modeling of the RBD in SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is a critical step for the development of new inhibitors of virus attachment and entry, either neutralizing antibodies or vaccines [40].

Tailored drug design by computational chemistry

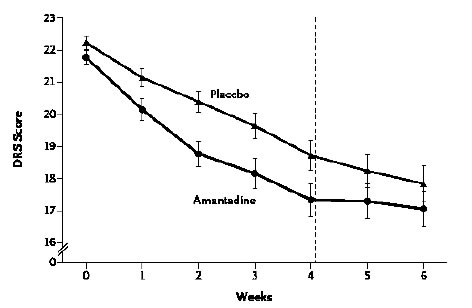

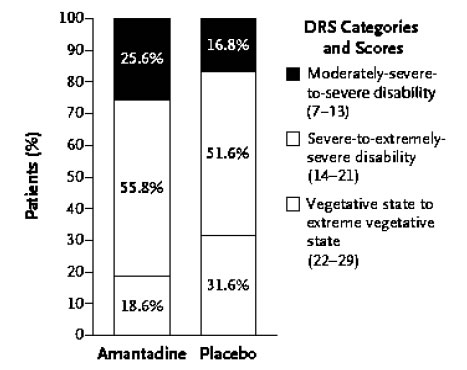

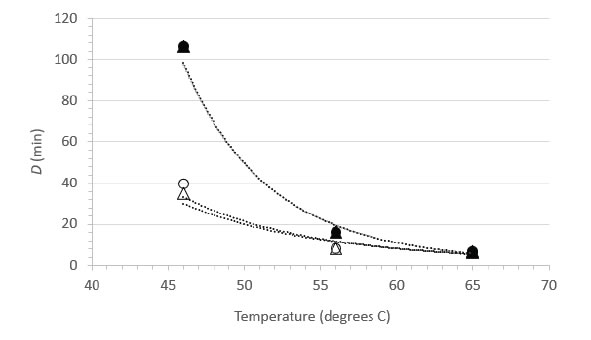

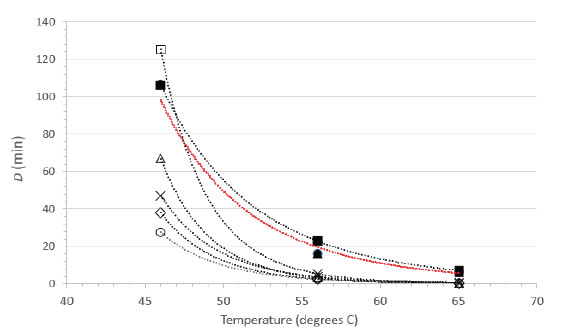

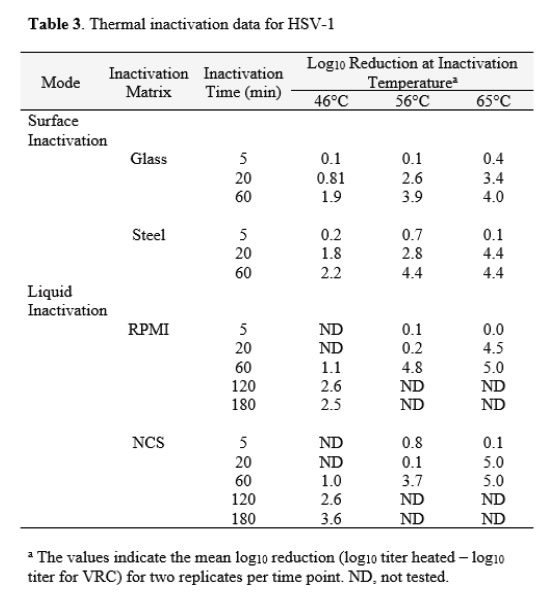

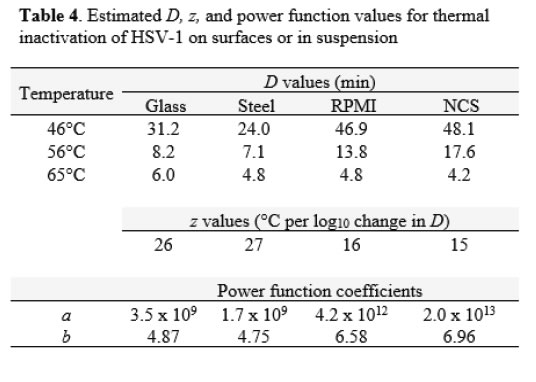

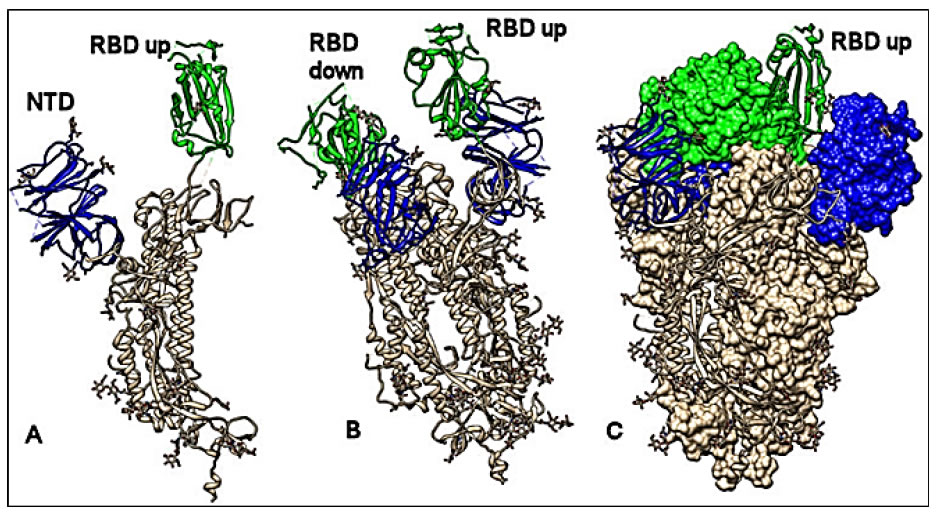

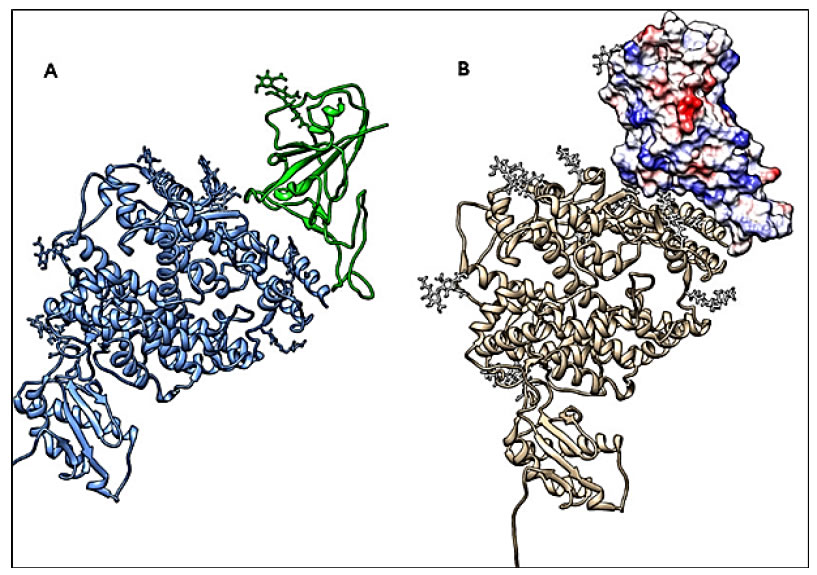

A much better and more detailed view of the structure of the S protein and its possible interactions with the host receptor is given by the emerging techniques of Computational Chemistry and Molecular Modeling. These techniques have raised exponentially during the last decades and showed their power in accelarating the discovery of new drugs with target specificity. In fact, they are widely used for rational drug design and discovery processes, where the molecular interaction mechanism must be deeply understood and the structural factors related with the bioactivity of each inhibitor must be clearly defined. Therefore, in order to design specific targeting drugs using these in silico techniques, the full knowledge of the three-dimensional (3D) structure of the macromolecular targets is the first step. This necessary information determines the success or failure of the further computational study. Luckily, the structure-solving of even the highest complex molecular targets can take advantage of the dramatic progress of spectroscopic techniques such as high resolution X-ray crystallography and Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM). This latter technique allows to easily solve huge and complex macromolecular structures such as membrane receptors and other supramolecular associations. Indeed, it also strongly contributed to the elucidation of the structural molecular features of the SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) protein, which is presently the elective target for the development of monoclonal therapeutic antibodies, inhibitors of virus entry into cells and vaccines. The S protein is densely glycosylated and can be classified as a trimeric class I fusion protein that exists in a metastable prefusion conformation, able to change its spatial disposition to promote the fusion of the viral membrane with the host cell membrane [41, 42].The S1 protein domain (Figure 2B) 3D structure has been resolved by Cryo-EM and deposited in the RCS protein data bank in February 2020 [43] (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/:pdb code 6VSB) (Figure 3). Moreover, also the Receptor Binding Domain (RBD) of the SARS-CoV-2 S protein has been elucidated, showing that it binds tightly to either the human or bat ACE2 receptors [44], with a binding affinity significantly higher than the one determined for the SARS-CoV RBD [45, 46]. The kinetics of this interaction has been quantified by surface plasmon resonance showing that ACE2 binds to the SARS-CoV-2 S ectodomain with ~15 nM affinity, which is ~10 to 20 fold higher than ACE2 binding to the SARS-CoV S protein [43, 47]. The 3D structure of the complex of ACE2 bound to the SARS-CoV-2 RBD (pdb code 6M17) has been elucidated by high resolution Cryo-EM and resembles the complex formed between SARS-CoV S and ACE2 (pdb code 2AJF) [48]. In order to engage the host cell receptor, the RBD of the S1 moiety of the spike protein (Figure 2B) undergoes hinge-like conformational movements that transiently hide or expose the determinants of receptor binding. These two states are referred to as the “down” conformation and the “up” conformation, where down corresponds to the receptor-inaccessible state and up corresponds to the receptor accessible state, which is thought to be less stable (Figure 3: images obtained by the CHIMERA software [49]) (Insert Fig 3).

Figure 3. Conformational analysis. Structure of the spike S protein of the SARS-CoV-2 in the prefusion conformation. A: protomer with the RBD up (green); N terminal domain in blue. B: protomer with the RDB up and down (green); N terminal domain in blue. C: Spike trimer complex; two protomers with RBD down (shown by molecular surface) and one with RBD up (shown by ribbons); N terminal domain in blue. All structures are referred to 6VSB pdb code. The CHIMERA software has been used for molecular visualization and analysis [49].

The overall structure of SARS-CoV-2 S and SARS-CoV S proteins (pdb code 5WRG) [50] is quite similar, with a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 3.8 Å over 959 Ca atoms [43]. A minor difference between these two structures is the position of the RBDs in their respective down conformations. Despite this, the alignment of the individual structural domains of the SARS-CoV-2 S and the corresponding one from SARS-CoV S, show a high degree of structural homology, with the exception of some aminoacidic changes located on the subdomain that binds to the ACE2-receptor, thus justifying the observed differences in the binding affinities (Figure 4) [43] (Insert Fig 4).

Figure 4. Conformational analysis. The RBD of the spike S1 moiety is shown in a complex with its receptor ACE2. A: Ribbons, S-protein RBD in green and ACE2 in blue. B: RBD by molecular surface showing charge distribution (blue positive, red negative), and ACE2 by grey ribbons. All structures are referred to 6M17 pdb code. The CHIMERA software has been used for molecular visualization and analysis [49].

Because of the indispensable function of the S protein in the infection process, it represents a target for antibody-mediated neutralization (Figure 2A), and characterization of the prefusion S structure would provide atomic-level information to guide both vaccine design and drug design development. Starting from these structural considerations, we have begun to study in silico a strategy to “capture” the S-protein RBD domain in its up conformation using natural-derived molecules; this involves the design of conformational restricted compounds that can “trap” the binding domain in an antibody-antigen fashion. Another strategy involves the search for ligands able to tightly bind and cross-link the RBD and the flexible part of the protein that controls the changes between its “up” and “down” spatial orientations; this should lead the RBD conformation to a permanent inactive state, unable to bind to its “natural” host cell receptor ACE2. However, the binding of the spike S protein to its ACE2 target is not optimal and it appears to be even less efficient than the binding ability shown by the SARS-Cov S protein [51]. Most recent evidence suggests that sialic acids (abundantly present in the respiratory tract) are also necessary for SARS-CoV-2 binding and infection [52]. Therefore, other computationally-driven strategies are being developed considering another CoV surface protein named M-protein (pdb code 6lu7) [53], as a possible drug-target. High Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS) from libraries of natural compounds or other databases including FDA approved drugs, aim to identify lead-compounds with inhibitory activity and low toxicity. A specific project has already started with funds by the European Commission within the H2020 framework. Within this project, it is worth mentioning the Exscalate (EXaSCale smArt pLatform Against paThogEns). Exscalate (exscalate.eu) has the power to screen a “chemical library” of 500 billion molecules, thanks to a processing capacity of more than 3 million molecules per second and using the proprietary software LiGen.

The role of food supplements

While research is working hard to find and produce specifically tailored pharmaceutical solutions (natural or synthetic vaccines and drugs) to fight this new pest, an easily approachable and already marketed possibility is given by food supplements. Food supplements do not pretend to cure the disease, but they can boost the organism to give it the necessary strength to mount an efficient and sometimes resolutive response to the infection, either preventing it from becoming a serious illness, or collaborating with pharmaceutical treatments to help the organism to finally get rid of the infective agents. Here follows the description of some natural products that have been chosen among many possible ones, based on the available literature and our own familiarity with the field. It is not and it cannot be an exhaustive list, but it gives an idea of what natural food supplements may contribute to our wellbeing also in the fighting against this pandemic infection.

Probiotics

Beside working on the outside, interfering with viral infectivity, it is also possible to work on the inside, for instance by strengthening the immune system. Epidemiological data show that the majority of Covid-19 infected people (likely more than 80%), especially the young, develop only very mild disease (ECDC, Corona virus disease 2019 in the EU/EEA and the UK; ninth update, 23 April 2020), most likely because their immunity can efficiently control the infection. We know that both genetic and environmental factors- mostly influenced by the lifestyle- may affect the function of the immune system, and the microbiota is a prominent one among these factors. Recent research has shown that the gut microbiota plays an essential role in the body’s immune response to infection and in maintaining overall health [54]. Normal development of the immune system and maturation of immune cells are dependent on signals coming from the microbiota [55]. For instance, in mucosal immunity the secretory IgA response involved in virus inactivation is stimulated by the microbiota [56]. Moreover, the microbiota releases signaling molecules actively shaping the host systemic immune response by regulating haematopoesis, hence potentiating the response to infection [57]. As well as mounting a response to infectious pathogens like coronavirus, a healthy gut microbiome also helps to avoid potentially dangerous immune over-reactions that might damage the lungs and other vital organs. Such deranged immune responses can cause respiratory failure and death. Therefore, it is important to use strategies that “support” rather than “boost” the immune system, because an overactive immune response can be as deleterious as an underactive one. The molecular mechanism governing the interactions between the gut microbiota and the immune system are only partially understood. For instance, it is known that the gut microbiota can metabolize hormones, and thus it may contribute to the regulation of cortisol levels in blood [58], which is tightly linked to the functioning of the immune system, since too much cortisol decreases the immunity. Moreover, a link between diet, microbiota and inflammation is evident [59]. In order to nourish an heterogeneous and thus efficient microbiota, the best way is eating a wide range of fiber-rich plant-based foods, avoiding refined, ultra-processed foods. The Mediterranean diet (based on the eating of plenty of fruit, vegetables, nuts, seeds and whole grains; healthy fats like high-quality extra virgin olive oil; and lean meat or fish) is known to improve the gut microbiota diversity and reduce inflammation. Such diet-modulated microbiota was associated with an increase in short/branch chained fatty acid (SCFA) production [60], and many studies have indicated that SCFAs possess immune regulatory functions in different tissues and organs, and may thus influence the outcome of micro-organism infections [61]. However, the relationship between the intestinal microbiota and the lungs is not yet fully understood. The respiratory tract has its own microbiota, but patients with respiratory infections generally have gut dysfunction or secondary gut dysfunction complications, which are related to a more severe clinical course of the disease, thus indicating gut–lung crosstalk [62, 63]. This occurrence has also been reported in COVID-19 patients [64]. It has been shown that modulating the gut microbiota can reduce enteritis and ventilator-associated pneumonia, because the gut microbiota may increase IFNα/β receptor expression in lung epithelia thus making the lung environment refractory to influenza virus replication [65]. A direct effect of probiotics administration on viral infection has been reported in several instances. Probiotics containing Lactobacillus plantarum (Lp) and Leuconostoc mesenteroides (Lm) showed efficacy in infected mice against the seasonal and avian influenza viruses H1N1 and H7N9. The plaque size reduction in treated mice was evidence of significantly restrained viral replication in lungs, with the effect of increasing the mean days and rates of survival of infected mice [66]. Oral administration of lyophilized Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) and Lactobacillus gasseri TMC0356 (TMC0356) to BALB/c mice 15 days before and 4 days after intranasal infection with the flu virus H1N1 resulted in a significant improvement of clinical symptom scores and reduction of pulmonary virus titres compared to those of control mice [67]. Lactobacillus plantarum Probio-38 and Lactobacillus salivarius Probio-37 isolated from the porcine gastrointestinal tract were found to inhibit replication in vitro of the transmissible gastroenteritis (TGE) coronavirus without any cytopathic effect [68]. The potential antiviral activity of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) was tested in vitro on human and animal intestinal and macrophage cell line models challenged with rotavirus (RV) and transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV). Results indicated that the best protection was obtained with Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and Lactobacillus casei Shirota against both virus types. A less specific, but still detectable antiviral activity was also found with Enterococcus faecium, Lactobacillus fermentum, Lactobacillus pentosus and Lactobacillus plantarum [69]. Finally, a probiotic with Lactobacillus plantarum DK119 [70] showed protective antiviral effects on influenza virus infected mice. Intranasal or oral administration of this strain resulted indose-dependent protection against further lethal infection with influenza A viruses, lowering the lung viral load. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluids of virally infected mice previously treated with DK119 showed high levels of cytokines IL-12 and IFN-γ and a low degree of inflammatory elements. The protective effect of DK119 apparently depended on modulation of dendritic and macrophage cells belonging to the host innate immunity. In fact, depletion of these elements in lungs and bronchoalveolar lavages completely abrogated cytokine production and the protection elicited by DK119 administration [70]. Although no clinical trials have been reported concerning the use and the effects of probiotics on the Covid-19 infection, clinically significant results on Covid-19 infected patients have been obtained by an integrated, multidisciplinary, personalized approach coupling pharmacological therapy and traditional chinese medicine, also including nutritional support and application of prebiotics and probiotics [71]. Therefore, even though the antiviral effect cannot be guaranteed, it is possible to support the intestinal microbiota by regularly eating natural yoghurt and artisan cheeses, which contain live microbes. Another source of natural probiotics are bacteria and yeast-rich drinks like kefir (fermented milk) or kombucha (fermented tea). Fermented vegetable-based foods, such as Korean kimchi (and German sauerkraut) are other good options. Alternatively, many different brands of probiotics containing a wide collection of bacteria that have been shown to produce beneficial effects on the organism, also on the antiviral side, are available on the market. Some of these commercial products also contain prebiotics (facilitating their engraftment in the intestines), or group B vitamins, that contribute to the reinforcing of the organism resistance to infections (see below).

Fatty acids

No specific probiotic indications exist as yet to improve the immune system performance to fight the Covid-19 infectious disease. However, food supplements containing a patented mixture of poly-unsaturated-fatty-acids (PUFAs), referred as Fatty Acid Group (FAG®), have been used to blunt the chronic inflammatory response generated by the immune system in animal models of macular degeneration [72] and optic nerve neuropathy [73]. The acronym FAG indicates diverse different mixtures produced by a calibrated mixing of long and short chain FAs given to sustain the metabolism of macrophages involved in the inflammatory reaction with the aim of facilitating its resolution and the shift of macrophages to the non-pro-inflammatory phase [74]. These products are commercially available in Italy under the trade name of Macular-FAG™ and Neuro-FAG™. Given their ability to control inflammatory cytokine production and the activation state of macrophages, it is likely that they might also beneficially influence and control the inflammatory state due to the over-reactive immune response in the lungs of Covid-19 patients.

Colostrum

Colostrum is the first nutrient secretion spilling from the mammary glands during the first hours after delivery of the newborn [75]. Since the newborn does not have efficient immune defenses, colostrum delivers the major components of the innate immune system, such as lactoferrin, lysozyme, lactoperoxidase and complement [76]. Several cytokines can also be found in colostrum, such as interleukins and tumor necrosis factor [77, 78]. Lactoferrin and lactoperoxidase contained in colostrum used as functional food are very promising, naturally occurring antimicrobials. Moreover, colostrum contains lipids (which generate during the digestion process degradation products with anti-infective capacity) and antimicrobial peptides present in casein molecules [79]. Colostrum also contains a collection of immunoglobulins (IgA, IgG and IgM) among which neutralizing antiviral IgA against the poliovirus and the reovirus have been described [80]. Mice fed for 14 days with bovine colostrum and subsequently infected with the human respiratory syncytial virus (hRSV) developed a milder disease with a lower lung titer of the virus with respect to saline fed mice. Such response correlated with a higher CD8 T lymphocyte titer in colostrum fed mice [81].Therefore, bovine colostrum, which is commercially available, could be used through different ways of administration (usually orally for systemic effects, but formulations would be possible also for eye or nose administration, to catch the virus at its entrance doors).

Micronutrients and vitamins

Many nutrients are involved in the normal functioning of the immune system and a healthy balanced diet should be enough to support the immune function. Micronutrients such as vitamins A, group B, C, D, E, zinc, iron, selenium, copper and magnesium are necessary for a correct and efficient immune response [82, 83, 84]. However, if there is a serious or even marginal deficiency of these micronutrients, this can negatively affect the immune function and decrease the resistance against infections [84]. Oxidative stress largely occurs during the inflammatory reaction to pathogen invasion and immune system activation, and represents a mechanism by which the organism gets rid of the undesired guests, however inflicting some damage to its own structures as well. Antioxidants enzymes are necessary to keep the phenomenon under control, and avoid excessive damage to the organism itself. All antioxidant enzymes have metal ions at their catalytic site (Mn++, Cu++, Zn++, Fe++ and Se++). All vitamins are essential for the correct development of innate and adaptive immunity in the body. Moreover, vitamins A, C, and E are required to maintain the skin epithelium barrier function [85]. Vitamin A sustains mucin production in the respiratory tract contributing to its barrier function versus pathogen infections [86]. Vitamin A is also important in the process of antibodies manufacturing. It plays an important role in the correct migration of T lymphocytes to the site of inflammation or infection, allowing a correct immune response of IgA producing cells localized in the mucous membranes [87]. Recently, it has been shown that retinoic acid (a derivative of vitamin A) can blunt the attack of hepatitis C virus (HCV) to the liver, and it does so by cooperating with interferons in the activation of immune defense genes [88, 89]. Vitamins C and E are antioxidants, and mop up the free radicals generated by the inflammatory process; free radicals and lipid peroxidation are immune-suppressive, hence these vitamins act to maintain or even to enhance – when necessary – the immune response. Vitamin C stimulates human immunity against viral infections by increasing phagocytosis, lymphocyte proliferation and neutrophil chemotaxis. Its high concentration within leukocytes falls rapidly due to its utilization during infections, and restores back to normal after healing, thus proving its involvement in taking care of infective agents during the response against exogenous pathogens [90, 91]. Vitamin E also plays a relevant role in enhancing immune reactions by inactivation and inhibition of free radicals [85]. Vitamin E oral supplementation improves T cell response and macrophage activity against infective agents [92, 93], and decreases the risk of upper respiratory tract infections in the elderly [94].

Members of B group vitamins are: thiamine (B1), riboflavin (B2), niacin (B3), pantothenic acid (B5), pyridoxine (B6), biotin (B7), folic acid (B9) and cobalamins (B12). The vitamins B6, B9 and B12 have a key role in enhancing the reactivity of the immune system, and influence the production and activity of natural killer (NK) cells [95]. Vitamin B6 contributes to the correct functioning of the immune response and antibodies production, by improving the communication between immune cells, cytokines and chemokines, and the gut microbiota [96]. Vitamin B6 deficiency impairs lymphocyte growth and proliferation, T-cell activity and antibody formation [97], and a clinical trial on 51 critically ill patients hospitalized in the intensive care unit has shown that vitamin B6 supplementation may help to increase their immune reactivity[98]. Vitamin B9 is relevant for the maintenance of immunologic homeostasis. Vitamin B9 is a survival factor for regulatory T cells (Treg), which express high levels of vitamin B9 receptor [96]. Treg cells have a critical role in the prevention of excessive immune response [99]. Therefore, a deficiency of vitamin B9 may result in an insufficient Treg cell population, thus increasing the organism susceptibility to paroxystic inflammation [100], as it appears to happen during the fatal illness of Covid-19 patients. Vitamin B12 cannot be naturally synthesized by human cells, but is produced by the gut microbiota. In terms of host immunity, in case of dietary vitamin B12 deficiency, the amount of cytotoxic T cells is decreased, so as NK cell activity; such condition can be improved with vitamin B12 dietary supplementation [101], thus indicating that this vitamin sustains the immune response via cytotoxic T cells and NK cells. A prominent role among vitamins is played by vitamin D (25 hydroxy vitamin D). Indeed, several lines of evidence support the role of vitamin D(normal circulating values between 20 and 40 ng/ml) in helping the organism to fight infections. Low values of vitamin D increase the risk of osteoporosis in the elderly, and are associated with a series of pathological conditions (tumors, cardiovascular, neurological and auto-immune diseases, diabetes, hypertension, chronic respiratory diseases) [102, 103] that make the individual less resistant to infections, and the organism unable to fight properly the infective state, thus increasing the morbidity of the infection and its mortality, as it happens in the case of Covid-19 disease. Epidemiological and clinical studies indicate that a deficit of vitamin D increases the risk of influenza and respiratory tract infection and the susceptibility to HIV infection. Individuals with low vitamin D status have been reported to have a higher risk of respiratory tract viral infections [104]. In vitro experiments with receptive cells suggest that vitamin D has direct anti-viral effects predominantly against enveloped viruses. Such effect might be linked to the ability of vitamin D to trigger macrophages to synthesize the anti-microbial peptides LL-37 and human beta defensin 2, and to stimulate macrophages and polymorphonuclear (PMN) leukocytes to produce cathelicidins, a family of lysosomal polypeptides functioning in innate immune defense, and contributing to the suppression of several pathogens infection, including URIs. The increased winter incidence of common cold and pneumonia has been related, at least partially, to decreased synthesis of vitamin D because of decreased exposure to sunlight [105]. An interesting study recently published, has linked Vitamin D, URIs and bowel disease. In patients affected by inflammatory bowel disease and with vitamin D below 20 ng/ml, the oral supplementation of 500 U/day of vitamin D while not decreasing the incidence of influenza, significantly decreased the incidence of URIs [106]. More evidence derives from an epidemiological study showing that vitamin D values higher than 38 ng/ml correlate with a two-fold decrease of the risk of getting acute respiratory tract infections, and with a shorter duration of the disease in those infected [107]. A meta analysis of 25 randomized, controlled clinical trials evaluating more than 10,000 subjects, concluded that oral supplementation of vitamin D to individuals with values lower than 26 ng/ml may decrease by 2/3 the incidence of acute respiratory infections [108]. A very recent, still unpublished paper [109] debates the three possible ways by which vitamin D might work in the prevention and treatment of viral infectious disease, including the Covid-19: i. Maintenance of epithelial tight junctions and the pulmonary barrier [110]; ii. Killing of enveloped viruses through the induction of cathelicidin and defensins [111, 112]; iii. Decreased production by the innate immune system of proinflammatory cytokines [113, 114], thus reducing the risk of the cytokine storm that may lead to severe pneumonia, insufficient blood oxygenation and death, such as it happens in Covid-19 disease [2].

Food supplements with antiviral effects

1 Echinacea

Three species are commonly used medicinally: Echinacea purpurea, E. angustifolia and E. pallida. Preparations of the root and of the aerial parts of the 3 Echinacea species are all used as immune stimulants. It has been suggested that Echinacea preparations may be useful in the treatment of URIs: (e.g. colds and flu). In healthy individuals, natural immunity appears to be potentiated, due to a significant (21%) increase in complement properdin [115]. However, more than for prevention, E. purpurea extracts are most often used to relieve colds and other URIs symptoms. Numerous randomized controlled clinical trials have examined the role of Echinacea preparations in the treatment of acute URIs after the onset of symptoms. Several of these studies have shown a significant reduction of the duration and/or severity of URIs following Echinacea treatment [116]. A systematic review of clinical studies with Echinacea extracts including both treatment and prevention designs corroborated the efficacy of treatments, although the lack of their standardization represented a serious bias to the conclusion [117]. A more recent meta analysis evaluating the effect of Echinacea on the incidence and duration of the common cold in randomised placebo-controlled studies confirmed Echinacea’s benefit in decreasing the incidence and duration of the common cold [118]. Echinacea extracts are best known as immune stimulant, increasing both innate and specific immunity [116]. The molecular characterization has shown that E. purpurea polysaccharide enriched extracts trigger phenotypic and functional maturation of dendritic cells by modulation of p38 MAPK, NF-kB and JNK pathways [119, 120] and the modulation of the latter can favour M1 macrophage polarization [121]. Moreover, also direct anti-inflammatory and anti-viral activities of Echinacea extracts have been reported [122, 123, 124]. Finally, a recent review has analyzed 82 clinical reports on the efficacy of micronutrients and Echinacea during common cold disease, extrapolating the useful doses, and reaching the conclusion that current evidence of efficacy for zinc, vitamins D and C, and Echinacea is so appealing that patients may be encouraged to use them in the treatment or prevention of their viral disease [124]. Apart from allergic reactions, in a recent large clinical trial Echinacea treatment has been shown to be safe, with a favorable risk to benefit ratio [125].

Ginseng

Panax ginseng is the most prominent and best-studied among the 3 known ginseng species. It has shown immunomodulatory properties in preclinical studies. Ginseng activated macrophages in vitro to produce cytotoxic reactive nitrogen species [126] and in vivoto defend mice from Candida albicans infection [127]; it also enhanced basal immunity, by stimulating NK cells activity in immune suppressed mice [128, 129]. In a clinical study, ginseng extracts improved the phagocytic activity and chemotaxis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells [130]. Although different immune functions may be activated by ginseng [131], it looks that the immunologic effects are mainly mediated by NK cell activity [129, 132]. For instance, the efficacy of a flu vaccine was significantly improved if an oral ginseng extract was co-administered, and the effect on the reduction of URIs was apparently to be ascribed to an increased amount of NK cell activity [133]. Very low level of adverse reactions are known for ginseng. It is not advised in case of hypertension and use of warfarin because of drug interaction [134, 135]. Because of its anti-fatigue effects it might interfere with sleeping when taken in the evening [136].

Astragalus

Astragalus is a widely used plant in Traditional Chinese Medicine. In recent years, particularly some species of the Astragalus family have been exploited in folk medicine for their pharmacological properties such as anti-inflammatory, immunostimulant, antioxidative, anti-cancer, antidiabetic, cardioprotective, hepatoprotective, and antiviral. The active constituents for the above-mentioned effects were proved to be polysaccharides, saponins, and flavonoids [137]. Astragalus polysaccharides have been shown to exhibit antiviral activities against the avian coronavirus and it has been suggested that they may represent a potential therapeutic agent for inhibiting its replication and to treat the avian infectious bronchitis [138].

Curcumin

Curcumin is the major component and the main bioactive substance of the rhizome of the plant Turmeric (Curcuma longa, belonging to the family of ginger: Zingiberaceae). It is present in the Indian and Chinese Traditional Medicine, where the curcuma longa rhizome has been used as antimicrobial agent as well as an insect repellant. Several studies have reported the broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity for curcumin including antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal, and antimalarial activities [139,140]. More specifically, antiviral activity was observed against several different viruses including parainfluenza virus type 3 (PIV-3), feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV), vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), flock house virus (FHV), and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), hepatitis viruses, influenza viruses and emerging arboviruses like the Zika virus (ZIKV) or chikungunya virus (CHIKV). Interestingly, it has also been reported that the molecule inhibits the sexually transmitted human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2) and human papillomavirus (HPV). A molecular target for this potent antiviral activity appears to be the inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH), which is a rate-limiting enzyme in the de novo synthesis of guanine nucleotides [141]. Most interestingly, curcumin is also an inhibitor of the 3CL protease activity (necessary for virus replication) of the SARS-CoV [142], and therefore shows inhibitory effects on this type of viruses, tightly related to the present pandemic infection by the SARS-CoV-2. Moreover, curcumin also possesses potent anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory properties [143], which may turn useful in controlling the strong inflammatory reaction happening in the lungs of patients infected with corona viruses. Curcumin oral supplementation has very low toxicity, and phase I clinical studies have indicated that curcumin doses up to 3.6-8.0 g/day for 4 months did not result in discernible toxicities except occasional mild nausea and diarrhea [144].

Ginger

Zingiber officinale belongs to the same family of Zingiberaceae that includes Curcuma longa. Like curcumin, it is also endowed with properties that might be useful to fight the Covid-19 infection. It contains diverse chemical components, such as phenolic derivatives, terpenes, lipids, polysaccharides, organic acids, and raw fibers. It is mainly the amount of phenolic compounds (gingerols and shogaols) that promotes the health benefits of ginger[145, 146]. Several studies have revealed the multiple biological activities of ginger root extract. These include immune modulation of lymphocytic (T and B) and macrophage response [147], antioxidant and anti-inflammatory [148], antimicrobial [149], cardiovascular [150] and respiratory [151] protective effects, all specifically relevant to the Covid-19 infection process. The antiviral efficacy of ginger has been further shown by in vitro experiments with the human respiratory syncytial virus (HRSV). Viral attachment and internalization of the virus into receptive cells was inhibited in a dose-dependent fashion by fresh ginger extracts, which could also stimulate interferon-beta secretion by mucosal cells, thus giving a further contribute to counteract viral infection. Therefore, HRSV-induced plaque formation on airway epithelium might be blocked by fresh, but not dried ginger extracts [152].

Elderberry

The most common elderberries are Samubucus nigra. A standardized elderberry liquid extract showed antimicrobial activity against both Gram-positive bacteria of Streptococcus pyogenes and group C and G Streptococci, and the Gram-negative bacterium Branhamella catarrhalis in liquid cultures. The liquid extract also displayed inhibitory effects on the propagation of human pathogenic influenza viruses [153]. Elderberry’s antiviral activity may be due to its high concentration of flavonoids, specifically the anthocyanins cyanidin 3-glucoside (C3G) and cyanidin 3-sambubioside, which have been shown to regulate the immune function and exhibit anti-viral effects [154]. A study recently published [155] addressed the efficacy of elderberry and its prevalent anthocyanin compound, C3G, on influenza virus infectivity. Study results showed that the whole elderberry extract, but not C3G alone, had inhibitory effects at all stages of influenza infection, though significantly stronger effects were most evident at late rather than at early stage of infection. Furthermore, the antiviral activity of elderberry was strongest when used during the whole course of the infection, rather than when used solely during the acute phase. The study confirmed that elderberry exerts its antiviral activity on influenza through several mechanisms of action, including suppressing the entry of the virus into cell (interfering with cell receptor binding), modulating the inflammatory post-infectious phase, and preventing viral diffusion to neighbouring cells. Elder berry also upregulated IL-6, IL-8 and TNF alpha, thus suggesting an effect on the immune response. Black elderberry extract has been shown to inhibit human influenza A (H1N1) infection in vitro by binding to H1N1 virions, thereby blocking the ability of the viruses to infect host cells. Ten more strains of influenza virus were also similarly inhibited [156]. Clinical evidence of the effects of elderberry supplementation on acute URIs derives from a meta-analysis study of 4 randomized controlled trials evaluating a total of 180 participants considering both the vaccination status of participants and the cause of their upper respiratory symptoms. Results showed that supplementation with elderberry significantly reduced upper respiratory symptoms [157].

Licorice

Glycyrrhiza glabra and Glycyrrhiza uralensis (licorice) are members of the pea family (Leguminosae). Licorice has well-documented immune-stimulant and antiviral, antibacterial and antifungal properties [158]. In Traditional Chinese Medicine it is used for a multitude of conditions, such as alleviating pain, tonifying spleen and stomach, eliminating phlegm, and relieving cough [159]. Among the 20 triterpenoids and almost 300 flavonoids contained in licorice, the triterpenoids glycyrrhizin (GL) and glycyrrhizic acid (GA) are those mainly active against viral infections [158]. Recent studies have shown that GL may inhibit hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection by interfering with its propagation. GL appears to be endowed with a membrane-stabilizing effect thus reducing cell membrane fluidity. Since HCV needs to use the host cell membrane in its lifecycle, it could be speculated that this could be the mechanism by which licorice stops the diffusion of the virus [160]. When GL was given by chronic intravenous injection to treat hepatitis C in Japan, few side effects and a marked reduction of the progression toward cirrhosis and hepatocarcinoma was reported [161]. GL and GA are known to have other useful pharmacological effects, including anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor and anti-allergic. Mechanisms of the GL-induced anti-inflammatory effect appear to result from inhibition of thrombin-induced platelet aggregation, inhibition of prostaglandin E2 production and inhibition of phospholipase A2 (PLA2) [162]. Such anti-inflammatory properties become evident with the efficacy of GL in alleviating allergic asthma in the experimental mouse model, by increasing IL-4 and IL-5 levels, whilst decreasing eosinophil counts and IgE levels, finally upregulating total IgG2a in serum. GL administration resulted in decreased hyper-reactivity of the immune system and pulmonary inflammation, hence in relief of airway constriction [163]. Flavonoids extracted from licorice root quenched pulmonary inflammation by inhibiting the recruitment of neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes, and by suppressing the mRNA expression of TNF-α [164]. Moreover, lung inflammation and mucus production also resulted attenuated by GL [165]. Finally, the isolated licorice root flavonoid, isoliquiritigenin, was shown to relax the tracheal smooth muscle of guinea pigs both in vitro and in vivo[166]. Among the other viruses shown to be responsive to licorice treatment are: herpes simplex type 1 (HSV-1), varicella-zoster virus (VZV), hepatitis A virus (HAV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus, Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), human cytomegalovirus (CMV) and influenza virus [158]. As a final caveat, it has to be noted that licorice is a potent inhibitor of the metabolic pathway breaking down cortisol in liver cells, thus increasing its level in circulation, and chronic licorice ingestion is associated with an increase in blood pressure and a drop in plasma potassium, even at modest doses [167]. This is of particular relevance for individuals with hypertension and cardiovascular disease, who should definitely limit their consumption of licorice.

Mullein flower

Verbascum thapsus L. is the most important species of its genus [168]. Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anticancer, antimicrobial, antiviral, antihepatotoxic and anti-hyperlipidemic activity have been ascribed to this plant. In traditional medicine, it is used to treat tuberculosis, ear-ache and bronchitis. In the ancient Rome and Ireland it was called “lungwort” because it was used to treat lung disease in humans and farm animals [169, 170]. Different pharmaceutical forms prepared from the extract of V. thapsus, such as capsules, tablets, or infusions have been used for the treatment of lung conditions or other age-related degenerative conditions because of their antioxidant activities [171, 172]. The in vitro antiviral activity against Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and influenza virus A have been reported [173, 174].

Conclusion

By the end of April 2020, the WHO global report of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic registers almost 3,000,000 positive people worldwide, with a mortality rate of approximately 7% (https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ ), which we know is mostly due to individuals with pre-existing health problems. Women – though equally affected – appear to be less susceptible to develop a serious or fatal disease. During the worst days in Italy the death toll of the Covid-19 infection has almost touched 1,000 individuals per day, over a positive infected population of 100,000. A recent epidemiological study [175] has calculated that the rate of asymptomatic individuals (healthy carriers of the SARS-CoV-2) is around 50%, though it is suspected that they might be even higher than 80% [176]. These numbers prompt some thoughts. The existing drug therapies show very little effect on previously unhealthy patients infected with the SARS-CoV-2, thus resulting in the observed high death rate. Young and/or healthy individuals have much better chances of either being asymptomatic, or to develop only mild, treatable symptoms. Healing from the infection is finally due to the immune system wiping out all the infective agents (drugs may facilitate this task).Therefore, considering all the evidence illustrated in this paper, we might speculate that those people, either young, or – if aged – living a healthy life, eating a healthy diet providing at the right time and the right age all the nutrients necessary to maintain an excellent homeostasis of their organism, possess an immune system and defense mechanisms able to control and fight properly most of the infections, developing mild symptoms, or none at all. However, since the present lifestyle in the majority of world countries (though for different, sometimes opposite reasons) is often far from healthy standards, there is an increased risk of getting serious infections hardly treatable by existing drugs. Moreover, it is highly probable that the present Covid-19 disease will indeed recede in few months, however it will not disappear for long, with periodic recurrent epidemic peaks, like the seasonal flu. Therefore, although no direct clinical data with the Covid-19 yet exist to support the hypothesis, we want to suggest a possible preventive strategy in order to enable those people who cannot run a perfectly healthy lifestyle, to reduce their risk of developing a serious or fatal illness due to either this SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, but also to different viruses or ailments that might arise in the future. In fact, nurturing a healthy organism is a general, unspecific defense against different kind of pathologies, which may weaken our immune system and our ability to respond to various infective diseases. Such strategy is based on the cultivation of a proper and various gut microbiota, using, when needed, the adequate pre- and probiotics, and searching for advise, when required, by diet specialists. Integration of even a normal and varied diet with food supplements providing extra doses of micronutrients, and/or with a varied mix of the natural products listed above, might give additional protection, either direct or indirect, to prevent or limit the diffusion of infective micro-organisms.

Final note

The COVID-19 emergency is prompting a huge research effort all over the world, tackling the many different aspects linked to a viral epidemy. In order to stay up-to-date on the different related topics, it is possible to freely access online the growing reference book by Bernd Sebastian Kamps and Christian Hoffmanneng “COVID reference” on the web site: www.CovidReference.com.

References

- Wan Y, Shang J, Graham R, Baric RS, Li F (2020) Receptor recognition by the novel coronavirus from Wuhan: an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS coronavirus. J Virol.

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, et al. (2020) Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395: 497-506. [crossref]

- Matsui H, Randell SH, Peretti SW, Davis CW, Boucher RC (1998) Coordinated clearance of periciliary liquid and mucus from airway surfaces. J Clin Invest 102: 1125-1131. [crossref]

- Houtmeyers E, Gosselink R, Gayan-Ramirez G, Decramer M (1999) Regulation of mucociliary clearance in health and disease. Eur Respir J 13 :1177-1188. [crossref]

- Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, et al. (2020) HLH Across Speciality Collaboration, UK. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet.

- Fu Y, Cheng Y, Wu Y (2020) Understanding SARS-CoV-2-Mediated Inflammatory Responses: From Mechanisms to Potential Therapeutic Tools. Virol Sin. [crossref]

- Dent SD, Xia D, Wastling JM, Neuman BW, Britton P, et al. (2015) The proteome of the infectious bronchitis virus Beau-R virion. J Gen Virol 96: 3499-3506. [crossref]

- Masters PS (2006) The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv Virus Res 66: 193-292. [crossref]

- Belouzard S, Millet JK, Licitra BN, Whittaker GR (2012) Mechanisms of coronavirus cell entry mediated by the viral spike protein. Viruses 4: 1011-1033 [crossref]

- J Alsaadi EA, Jones IM (2019) Membrane binding proteins of coronaviruses. Future Virol 14: 275-286. [crossref]

- Seah I, Agrawal R (2020) Can the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Affect the Eyes? A Review of Coronaviruses and Ocular Implications in Humans and Animals. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. [crossref]

- Reviglio VE, Osaba M, Reviglio V, ChiaradiaP, Kuo IC, et al. (2020) 2019-nCoV and Ophthalmology: A New Chapter in an Old Story. Med Hypothesis Discov Innov Ophthalmol 9: 71-73.

- Colavita F, Lapa D, Carletti F, Lalle E, Bordi L, et al. (2020) SARS-CoV-2 Isolation From Ocular Secretions of a Patient With COVID-19 in Italy With Prolonged Viral RNA Detection. Ann Intern Med. [crossref]

- Xia J, Tong J, Liu M, Shen Y, Guo D (2020) Evaluation of coronavirus in tears and conjunctival secretions of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Med Virol. [Crossref]

- Wu P, Duan F, Luo C, Liu Q, Qu X, et al. (2020) Characteristics of Ocular Findings of Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Ophthalmol. [crossref]

- Senanayake Pd, Drazba J, Shadrach K, Milsted A, Rungger-Brandle E , et al. (2007) Angiotensin II and its receptor subtypes in the human retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 48: 3301-3311. [crossref]

- Sun Y, Liu L, Pan X, Jing M (2006) Mechanism of the action between the SARS-CoV S240 protein and the ACE2 receptor in eyes. International Journal of Ophthalmology 6: 783-786.

- Denney L, Ho LP (2018) The role of respiratory epithelium in host defence against influenza virus infection. Biomed J 41: 218-233. [crossref]

- Mendes MM, Charlton K, Thakur S, Ribeiro H, Lanham-New SA (2020) Future perspectives in addressing the global issue of vitamin D deficiency. Proc Nutr Soc [crossref]

- Cai H (2020) Sex difference and smoking predisposition in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med.

- Brodin P (2020) Why is COVID-19 so mild in children?. Acta Paediatr.

- Dong L, Hu S, Gao J (2020) Discovering drugs to treat coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Drug Discov Ther 14:58–60. [crossref]

- Hu TY, Frieman M, Wolfram J (2020) Insights from nanomedicine into chloroquine efficacy against COVID-19. Nat Nanotechnol.

- Gawałko M, Balsam P, Lodziński P, Grabowski M, Krzowski B, et al. (2020) Cardiac Arrhythmias in Autoimmune Diseases. Circ J. [crossref]

- Zhou D, Dai SM, Tong Q (2020) COVID-19: a recommendation to examine the effect of hydroxychloroquine in preventing infection and progression. J Antimicrob Chemother.

- Al-Tawfiq JA, Al-Homoud AH, Memish ZA (2020) Remdesivir as a possible therapeutic option for the COVID-19. Travel Med Infect Dis. [crossref]

- Callaway E, Cyranoski D (2020) China coronavirus: Six questions scientists are asking. Nature 577:605–607. [crossref]

- Martinez MA (2020) Compounds with Therapeutic Potential against Novel Respiratory 2019 Coronavirus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. [crossref]

- Ferrario BE, Garuti S, Braido F, Canonica GW (2015) Pidotimod: the state of art. Clin Mol Allergy [crossref]

- Puggioni F, Alves-Correia M, Mohamed MF, Stomeo N, Mager R et al. (2019) Immunostimulants in respiratory diseases: focus on Pidotimod. Multidiscip Respir Med. [crossref]

- Mahashur A, Thomas PK, Mehta P, Nivangune K, Muchhala S, et al. (2019) Pidotimod: In-depth review of current evidence. Lung India 36: 422-433. [crossref]

- Zhao N, Liu C, Zhu C, Dong X, Liu X (2019) Pidotimod: a review of its pharmacological features and clinical effectiveness in respiratory tract infections. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 17: 803-818. [crossref]

- Conti P, Ronconi G, Caraffa A, Gallenga CE, Ross R, et al. (2020) Induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1 and IL-6) and lung inflammation by Coronavirus-19 (COVI-19 or SARS-CoV-2): anti-inflammatory strategies. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. [crossref]

- Favalli EG, Ingegnoli F, De Lucia O, Cincinelli G, Cimaz R, et al. (2020) COVID-19 infection and rheumatoid arthritis: Faraway, so close!. Autoimmun Rev.

- Li XC, Zhang J, Zhuo JL (2017) The vasoprotective axes of the renin-angiotensin system: Physiological relevance and therapeutic implications in cardiovascular, hypertensive and kidney diseases. Pharmacol Res. 125: 21-38. [crossref]

- Wan Y, Shang J, Graham R, Baric RS, Li F (2020) Receptor Recognition by the Novel Coronavirus from Wuhan: an Analysis Based on Decade-Long Structural Studies of SARS Coronavirus. J Virol.

- Hanff TC, Harhay MO, Brown TS, Cohen JB, Mohareb AM (2020) Is There an Association Between COVID-19 Mortality and the Renin-Angiotensin System-a Call for Epidemiologic Investigations. Clin Infect Dis.

- Fang L, Karakiulakis G, Roth M (2020) Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection?. Lancet Respir Med. [crossref]

- Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, Cai Y, Liu T et al. (2020) Association of Cardiac Injury With Mortality in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. [crossref]

- Tai W, He L, Zhang X, Pu J, Voronin D, et al. (2020) Characterization of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of 2019 novel coronavirus: implication for development of RBD protein as a viral attachment inhibitor and vaccine. Cell Mol Immunol. [crossref]

- Li F (2016) Structure, Function, and Evolution of Coronavirus Spike Proteins. Annu. Rev. Virol 3: 237-261. [crossref]

- Bosch B. J., van der Zee R., de Haan C. A., Rottier P. J. (2003) The Coronavirus Spike Protein Is a Class I Virus Fusion Protein: Structural and Functional Characterization of the Fusion Core Complex. J Virol 77: 8801-8811. [crossref]

- Wrapp D, Wang N, Corbett KS, Goldsmith JA, Hsieh CL, et al. (2020) Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 367: 1260-1263. [crossref]

- Tai W., He L., Zhang X, Pu J, Voronin D, et al. 2020. Characterization of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of 2019 novel coronavirus: implication for development of RBD protein as a viral attachment inhibitor and vaccine. Cell Mol Immunol.

- Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Krüger N, Müller M, Drosten C, et al. (2020) Pöhlmann S. The novel coronavirus 2019 (2019-nCoV) uses the SARS-coronavirus receptor ACE2 and the cellular protease TMPRSS2 for entry into target cells. BioRxiv.

- Wan J, Shang R, Graham R S, Baric F, Li J (2020) Receptor Recognition by the Novel Coronavirus from Wuhan: an Analysis Based on Decade-Long Structural Studies of SARS Coronavirus. Virol J .

- Kirchdoerfer RN, Wang N, Pallesen J, Wrapp D, Turner HL et al. (2018) Stabilized coronavirus spikes are resistant to conformational changes induced by receptor recognition or proteolysis. Sci Rep. [crossref]

- Song W, Gui M, Wang X, Xiang Y (2018) Cryo-EM structure of the SARS coronavirus spike glycoprotein in complex with its host cell receptor ACE2. PLOS Pathog. [crossref]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM (2004) UCSF Chimera–a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 25: 1605-1612. [crossref]

- Gui M, Song W, Zhou H, Xu J, Chen S, et al. (2017) Cryo-electron microscopy structures of the SARS-CoV spike glycoprotein reveal a prerequisite conformational state for receptor binding. Cell Res.

- Andersen KG, Rambaut A, Lipkin WI, Holmes EC, Garry RF (2020) The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Med. [crossref]

- Milanetti E, Miotto M, Rienzo L, Monti M, Gosti G, et al. (2020) In-Silico evidence for two receptors based strategy of SARS-CoV-2. bioRxiv.

- Jin Z, Du X, Xu Y, Yongqiang Deng, Meiqin Liu, et al. 2020. Structure of Mpro from COVID-19 virus and discovery of its inhibitors. bioRxiv.

- Lazar V, Ditu LM, Pircalabioru GG, Gheorghe I, Curutiu C,et al. (2018) Aspects of Gut Microbiota and Immune System Interactions in Infectious Diseases, Immunopathology, and Cancer. Front Immunol.

- Kosiewicz MM, Zirnheld AL, Alard P (2011) Gut microbiota, immunity, and disease: a complex relationship. Front Microbiol. [crossref]

- Rolhion N, Chassaing B (2016) When pathogenic bacteria meet the intestinal microbiota. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. [crossref]

- Van Den Elsen LWJ, Poyntz HC, Weyrich LS, Young W, Forbes-Blom EE (2017) Embracing the gut microbiota: the new frontier for inflammatory and infectious diseases. Clin Transl Immunology. [crossref]

- Farzi A, Fröhlich EE, Holzer P (2018) Gut Microbiota and the Neuroendocrine System. Neurotherapeutics. 15: 5-22. [crossref]

- Telle-Hansen VH, Holven KB, Ulven SM (2018) Impact of a Healthy Dietary Pattern on Gut Microbiota and Systemic Inflammation in Humans. Nutrients. [crossref]

- Ghosh TS, Rampelli S, Jeffery IB, Santoro A, Neto M, et al. (2020) Mediterranean diet intervention alters the gut microbiome in older people reducing frailty and improving health status: the NU-AGE 1-year dietary intervention across five European countries. Gut. [crossref].

- Ohira H, Tsutsui W, Fujioka Y (2017) Are Short Chain Fatty Acids in Gut Microbiota Defensive Players for Inflammation and Atherosclerosis?. J Atheroscler Thromb. 24: 660-672. [crossref]

- Budden KF, Gellatly SL, Wood DL, Cooper MA, Morrison M, et al. (2017) Emerging pathogenic links between microbiota and the gut-lung axis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 15: 55-63. [crossref]

- Dumas A, Bernard L, Poquet Y, Lugo-Villarino G, Neyrolles O (2018) The role of the lung microbiota and the gut-lung axis in respiratory infectious diseases. Cell Microbiol. [crossref]

- Gao QY, Chen YX, Fang JY (2020) 2019 Novel coronavirus infection and gastrointestinal tract . J Dig Dis [crossref]

- Bradley KC, Finsterbusch K, Schnepf D, Crotta S, Llorian M, et al. (2019) Microbiota-Driven Tonic Interferon Signals in Lung Stromal Cells Protect from Influenza Virus Infection. Cell Rep 28: 245-256. [crossref]

- Bae JY, Kim JI, Park S, Yoo K, Kim IH, et al. (2018) Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum and Leuconostoc mesenteroides Probiotics on Human Seasonal and Avian Influenza Viruses. J Microbiol Biotechnol 28: 893-901. [crossref]

- Kawase M, He F, Kubota A, Harata G, Hiramatsu M (2010) Oral administration of lactobacilli from human intestinal tract protects mice against influenza virus infection. Lett Appl Microbiol 51: 6-10. [crossref]

- Kumar R, Seo BJ, Mun MR, Kim CJ, Lee I, et al. (2010) Putative probiotic Lactobacillus spp. from porcine gastrointestinal tract inhibit transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus and enteric bacterial pathogens. Trop Anim Health Prod 42: 1855-1860. [crossref]

- Maragkoudakis PA, Chingwaru W, Gradisnik L, Tsakalidou E, Cencic A (2010) Lactic acid bacteria efficiently protect human and animal intestinal epithelial and immune cells from enteric virus infection. Int J Food Microbiol. [crossref]

- Park MK, Ngo V, Kwon YM, Lee YT, Yoo S, et al. (2013) Lactobacillus plantarum DK119 as a probiotic confers protection against influenza virus by modulating innate immunity. PLoS One. [crossref]

- Xu K, Cai H, Shen Y, Ni Q, Chen Y, et al. (2020) [Management of corona virus disease-19 (COVID-19): the Zhejiang experience]. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. [crossref]

- Cammalleri M, Dal Monte M, Locri F, Lardner E, Kvanta A, et al. (2017) Efficacy of a Fatty Acids Dietary Supplement in a Polyethylene Glycol-Induced Mouse Model of Retinal Degeneration. Nutrients. [crossref]

- Dal Monte M, Cammalleri M, Locri F, Amato R, Marsili S, et al. (2018) Fatty Acids Dietary Supplements Exert Anti-Inflammatory Action and Limit Ganglion Cell Degeneration in the Retina of the EAE Mouse Model of Multiple Sclerosis. Nutrients. [crossref]

- Locri F, Cammalleri M, Pini A, Dal Monte M, Rusciano D, et al. (2018) Further Evidence on Efficacy of Diet Supplementation with Fatty Acids in Ocular Pathologies: Insights from the EAE Model of Optic Neuritis. Nutrients. [crossref]

- Ballard O, Morrow AL (2013) Human milk composition: nutrients and bioactive factors. Pediatr Clin North Am 60: 49-74. [crossref]

- Palmeira P, Carneiro-Sampaio M (2016) Immunology of breast milk. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 62: 584-593. [crossref]

- Hagiwara K, Kataoka S, Yamanaka H, Kirisawa R, Iwai H (2000) Detection of cytokines in bovine colostrum. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 76: 183-190. [crossref]

- Rudloff HE, Schmalstieg FC Jr, Mushtaha AA, Palkowetz KH, Liu SK, et al. (1992) Tumor necrosis factor-alpha in human milk. Pediatr Res 31: 29-33. [crossref]