Abstract

Currently, novel drug design focused on the searching pharmacological compounds acting via influence on GPCRs heteromers. The strategy allows obtaining highly selective effects since these heteromers appear only on specific cells and tissues. Therefore, human monoclonal scFv antibodies able to recognizing GPCRs heteromers may constitute a valuable tool in modern therapies. Antibody phage display technique together with high throughput screening play a key role in the development of clinically useful immunomolecules. Therefore in the present work we focused on the comparison of various strategies used for biopanning process during phage display procedure, dedicated to isolation scFv antibodies specifically recognizing GPCRs heteromers. Experiments were conducted in two different cell lines (CHO-K1 and HEK 293) and six various selection procedures were described. Elimination of nonspecific bindings constitutes a key point during the process. Results obtained duing selection conducted in the conditions promoting internalization process were the most satisfactory.

Keywords

Phage Display, scFv antibody, GPCRs, Hetromer, Biopanning

1. Introduction

Recently heteromers (receptor heterodimers) formed by human G-Protein Coupled Receptors (GPCRs) constitute extremely important targets in the design of modern treatment strategies [1]. Alteration of pharmacological properties of the receptors included in the heterocomplex have been proven and widely described in the literature [1–3]. Research focused on finding therapeutic compounds able to selective recognition of GPCRs heteromers are currently very popular. Such strategy allows to obtain a tissue-specific acting, since the interaction between receptors engaged in the complex formation can only take place when the receptors are simultaneously expressed on the same cell. Recent data indicate the existence of clinically relevant GPCRs heteromers, important in the treatment of, among others, pain, asthma or Parkinson’s disease [3–7].

Creation of the human monoclonal antibodies with specificity towards membrane GPCRs heteromers still remains sizable challenge. To fulfil its role, the kind of antibody must recognize the structural epitope formed within the GPCRs heteromeric structure and, at the same time, not show specificity for monomeric or homomeric forms of the receptors. The phage display technology provided the best conditions for the isolation of human monoclonal antibody specifically recognizing the spatial epitope formed by GPCRs heteromers.

Currently phage display technology attracts most attention since the methods is a powerful tool, among others, in drug discovery, nanotechnology, immunology, agriculture, diagnostics, neurobiology, molecular imaging etc [8–12]. The technology developed by George P. Smith in 1985 [13] constitutes a very useful tool for the study of protein–protein, protein–peptide, and protein–DNA interactions [14]. The methodology is based on the fact that phage phenotype and genotype are physically linked [14]. A gene encoding a protein of interest inserted into a gene of bacteriophage coat protein is expressed and presented on the phage surface. The concept is simple: a population of phage is engineered to express random-sequence peptides, proteins or antibodies on their surface [8]. From this population, a selection is made of those phage that bind the desired target [8]. Hereby, large proteins libraries can be screened and unique molecules which bind to their targets with high affinity and specificity can be isolated [15]. The advantage of the method is the possibility of the production of monoclonal antibodies recognizing antigens that cannot be used to immunize an animal due to their toxicity, non-immunogenicity or presence in complexes on the surface of cell membranes [16].

ScFvs (Single Chain Variable Fragment) are small monoclonal antibody fragments composed of immunoglobulin-heavy (VH) and light chain-variable (VL) regions with a flexible peptide linker designed to connect the two chains such that the antigen binding site is retained in a single co-linear molecule [17]. The kind of antibodies can be derived from phage display libraries [18,19]. ScFvs are very useful in pharmacology and diagnostic fields as well as in drug delivery issues since they can function as targeting ligands. Functionalization of the surface of drug carriers by scFvs enable controlled transport of pharmacological compounds directly to the desired place of action [20]. ScFvs, in comparison to the much larger Fab, F(ab)2, and IgG forms, are characterized by better tissue penetration, lower retention times in non-target tissues, faster blood clearance and, above all, reduced immunogenicity. These features cause that they are very useful for therapeutic applications [21].

The main purpose of presented work was the description of different strategies which may be used during phage display procedure for the isolation of scFvs antibodies specifically recognizing human GPCRs heteromers. To separate the phages that effectively bind defined heteromer it is extremely important to carry out the selection rounds in conditions most similar to those in which desirable receptors occur naturally in the cells, which allowed to preserve the native spatial conformation of the heteromer. Elimination of nonspecific binding without losing rare specific ones seems a serious challenge. Therefore, in the work several various types of selection were presented. The experiments were independently conducted for two GPCRs pair: dopamine D2 (D2R) and serotonin 5-HT1A (5-HT1AR) receptors as well as dopamine D2 and serotonin 5-HT2A receptors. Similar results were obtained for both cases. For simplicity in the work the outcomes for D2–5-HT1A were presented.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Cell culture and Transfection

CHO-K1 cells (ATCC) were grown in RPMI (Sigma) medium; HEK 293 cells (ATCC) were grown in minimal essential medium (MEM) (Sigma) with 1% L-glutamine. Both medium were supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma). All cells were cultured at 37 °C inside a humidified incubator in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. Transient and stable transfections were made by using the TurboFect reagent (Thermo Sci.) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Early passages of CHO-K1 as well as HEK 293 cells were stably transfected (1.5 µg DNA) with the plasmid pcDNA3.1(+) encoding the human 5-HT1AR or the human D2R (UMR cDNA Resource Centre) separately or cotransfected with both vectors. Stable cell lines expressing D2R and/or 5-HT1AR were obtained after the addition of the selection antibiotic, G418 (Sigma), at a final concentration of 0.75 mg/ml. Cells resistant to the antibiotic and stably expressing investigated receptors were analysed by RT-PCR (data not shown). Forty-eight hours before the selection experiment, stable cell lines were, additionally, transiently transfected with 0.5 µg DNA (per 10 mm plate area) encoding the desired receptors.

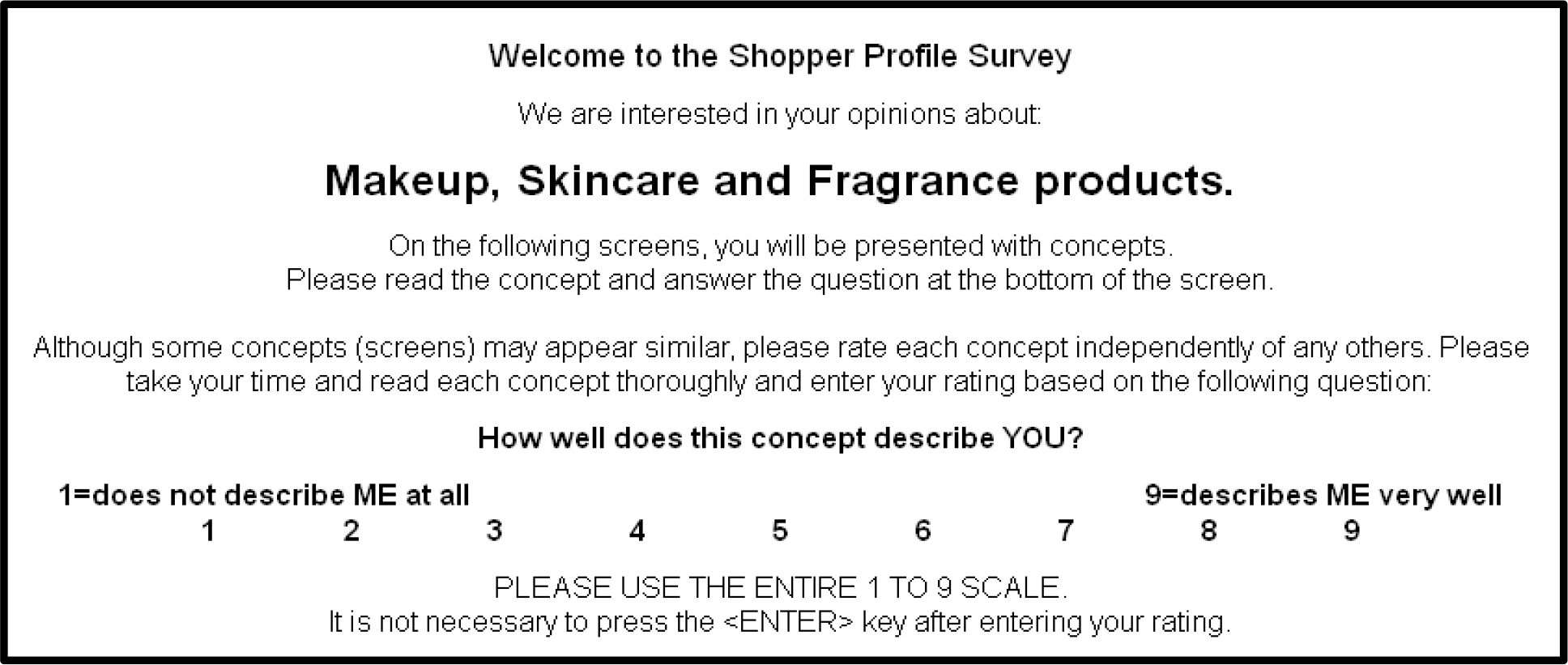

2.2 Screening of phage-displayed scFv libraries

The human antibody scFv phagemid library Tomlinson I+J (Geneservice) was used. The library J was amplified and titrated (used the library size was 1.9×1012 cfu) according to the manufacturer’s protocols using E. coli TG1 cells [18]. Biopanning was performed on positive (+) and negative (-) cells expressing desired receptors. CHO-K1 as well as HEK 293 cell lines were used. CHO+ and HEK+ cells constituted cells expressing D2–5–HT1A heteromers whilst CHO- and HEK- cells expressed separately D2R or 5–HT1AR and were mixed before experiment in a 1:1 ratio. Four – six positive rounds of selection followed by prenegative selection and one final negative selection were performed independently on both mentioned above cell lines. Briefly, during preselection amplified phages were blocked for 2 hr at room temperature (RT) in 3% MPBS (with stirring from time to time) and then were added to the negative cells (growing on 150 mm plates (15x) 95% confluence) or to the cells suspension – 108 cells) for 2 hr at RT (with stirring from time to time). Next, the cells were collected and centrifuged (10 min at 1000 rpm). Supernatant containing unbound phages was used to positive selection. The final negative selection were performed similarly to preselection.

2.2.1 Positive selection – type A and B

Phages derived from preselection were added to the culture medium of positive cells growing on 150 mm plates (10x, 95% confluence) and were incubated with shaking for 2 hr at 37 °C (type A) or at RT (type B). After that time, unbound phages were washed away with PBS buffer. The number of washes after each round of selection has been shown in Table 1. In the next step, the cells were collected, centrifuged and resuspended in PBS containing 1 mg/ml trypsin. The suspension was incubated on the rotator for 10 min at RT and then centrifuged (10 min, 1000rpm, 4 °C). The supernatant containing the desired phages after titration and amplification was used for another round of biopanning.

Table 1. Number of washing steps performer after each round of selection during phage display procedure.

|

NUMBER OF WASHING STEPS |

||||||

|

Selection case |

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

VI |

|

A |

5 |

10 |

20 |

30 |

30 |

30 |

|

B |

5 |

10 |

20 |

30 |

30 |

30 |

|

C |

3 |

6 |

12 |

24 |

30 |

30 |

|

D |

4 |

6 |

8 |

10 |

12 |

15 |

|

E |

4 |

6 |

8 |

10 |

12 |

15 |

|

F |

4 |

6 |

8 |

10 |

12 |

15 |

2.2.2 Positive selection – type C

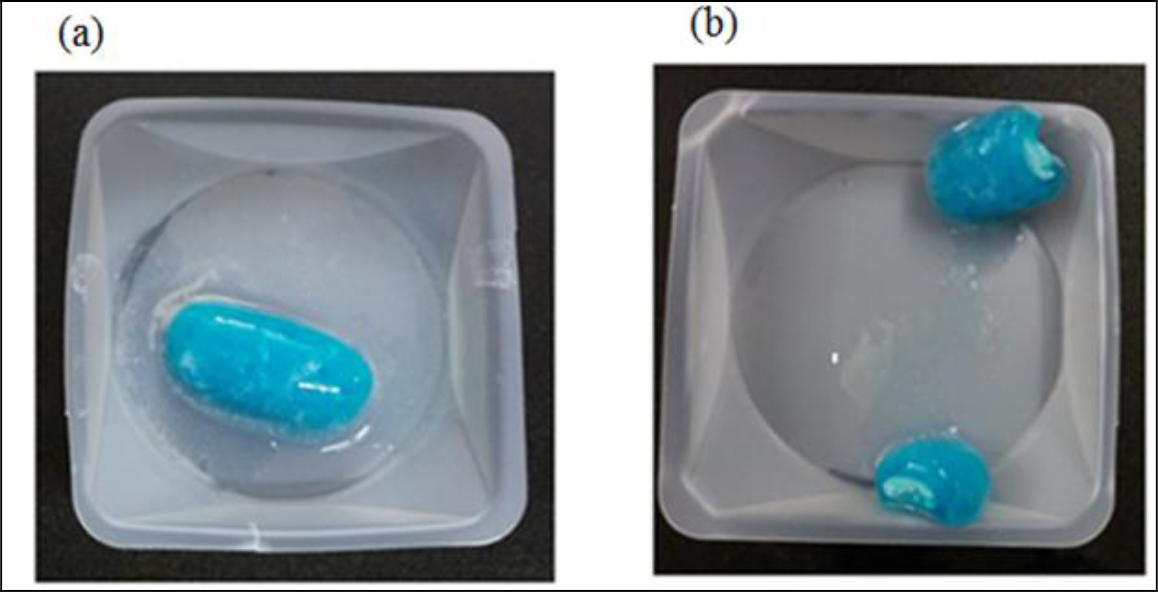

Positive cells growing on 150 mm plates (10x, 95% confluence) were used. Phages after preselection were added to the cell medium for 2 hr (at 0 °C). Then, the medium was removed and cells were washed 3 times with cold PBS. Between washings, RPMI medium was added, and the cells were incubated on ice for 10 min. Then, the temperature of incubation was changed to 37 °C for 20 min. In the next step, the cells were washed 4 times using elution buffer (100 mM glycine, 150 mM NaCl, pH 2.8). The number of washes increased (twice each time) with subsequent rounds of selection. Finally, cells were harvested from the plates and resuspended in PBS containing trypsin (1 mg/ml) for approximately 15 min (until cell lysis). Then, the obtained suspension was centrifuged (10 min, 4000 rpm, 4 °C), and the supernatant containing the desired phages after titration and amplification was used for another round of biopanning.

2.2.3 Positive selection – type D

The experiment was performed in the cells suspension expressing both desired receptors (positive cells). The number of used cells (in the first round was 2 × 107) increased twice with subsequent rounds of selection. Phages were incubated with the cells for 2 hr with shaking at RT. Then unbounded phages were eliminated by washing (PBS) and centrifugation (10 min, 1000 rpm, RT) (Table 1). In the next step cell pellet was resuspended in PBS containing trypsin (1 mg/ml) for approximately 5 min. Then the suspension was centrifuged (10 min, 4000 rpm, RT), the supernatant was collected and after titration and amplification was used for another round of biopanning.

2.2.4 Positive selection – type E and F

In case E and F experiments were performed similarly to type D. Differences appeared at the stage of acquiring bounded phages. In type E, after washing steps cell pellet was incubated with H2O (caused cell lysis) for 10 min with shaking at RT. Then trypsin (1 mg/ml) in PBS was added to the suspension for 10 min incubation at RT. Finally, the desired phages were obtained from the supernatant after centrifugation (10 min, 4000 rpm, RT).

In case F, after washing steps the cell pellet was incubated for 15 min at RT with clozapine (10–9 M). Then, after centrifugation (10 min, 1000 rpm, RT) the supernatant was collected and the trypsin (1 mg/ml) in PBS was added. Obtained phages after titration and amplification were used for another round of biopanning.

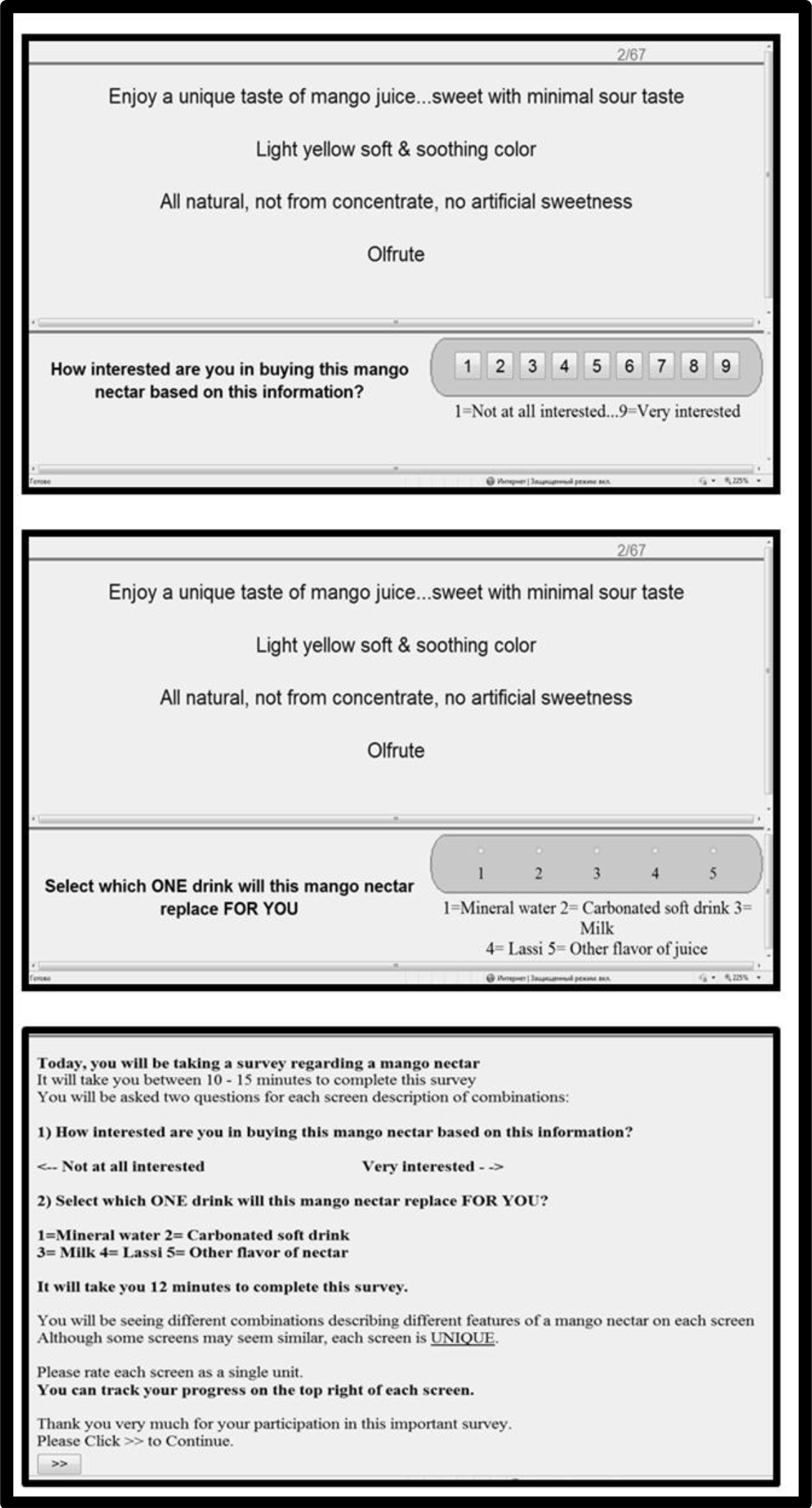

2.3 Polyclonal phage ELISA

The quality of the biopanning process was monitored using polyclonal phage ELISA. Amplificated phages (50 µl) obtained after selection rounds were incubated with 50 µl of 4% MPBS for 2 hr at 37 °C. Then, 1.5 × 105 cells (resuspended in 50 µl of medium with 5% FBS) were mixed with previously blocked phages. Both the positive (CHO+ or HEK+ cells expressing D2–5-HT1A heteromers) and the negative (CHO- or HEK- cells expressing a single type of receptor mixed at the 1:1 ratio) probes were used. After 1 hr ice incubation, the washing step was conducted 3 times at 4 °C using 200 µl cold PBS. Each washing round ended with centrifuging (1000 rpm x g, 10 min, 4 °C), and the supernatant rejection. Detection of bound phages were determined by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-M13 monoclonal antibodies (GE Healthcare). Briefly, after washing, the probes were incubated with the antibody resuspended in a 1:5000 ratio in 3% MPBS for 30 min on ice and then washed 4 times as described above. Finally, 100 µl of TMB substrate (GE Healthcare) and 100 µl of 1 M HCl (per well) were used to induce the reaction. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.4 Monoclonal phage ELISA

Based on the results of polyclonal phage ELISA, phage clones from rounds characterized by the highest affinity against positive cells (CHO+ or HEK+) cells were randomly selected for monoclonal phage ELISA experiments. Individual bacterial colonies were inoculated into 96-well plates containing 100 µl 2xTYAG (2xTY (Bioshop) with 100 μg/ml ampicillin (Sigma) and 1% glucose (Bioshop)) medium per well and cultured overnight at 37 °C (250 rpm shaking). Then, 5 µl of the culture (from each well) was added to fresh 200 µl 2xTYAG medium and cultured with shaking (250 rpm) at 37 °C for 2 hr. Next, 109 helper phages were added to the each well and incubated for 1 hr and at 37 °C with shaking at 250 rpm. After centrifugation (1800 x g, 10 min), the supernatants were removed, and bacterial pellets were resuspended in 200 µl 2xTYAKG (2xTY containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin, 50 µg/ml kanamycin (Sigma) and 1% glucose) medium and incubated overnight at 30 °C (250 rpm). Finally, after plates centrifugation (1800 x g, 10 min), the 50 µl of supernatants (containing monoclonal phages) were used in the phage ELISA as described above (2.3).

3. Results and Discussion

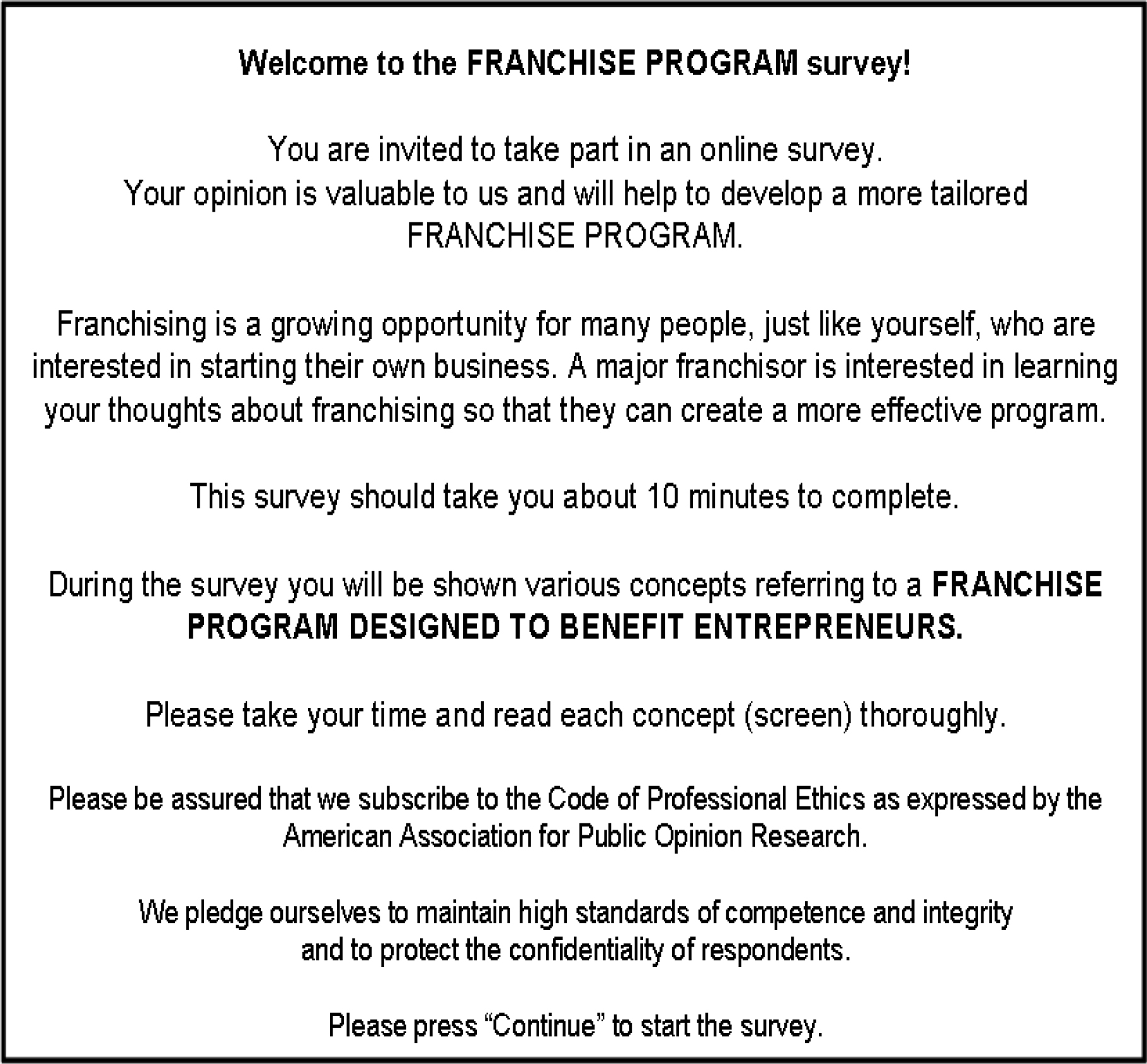

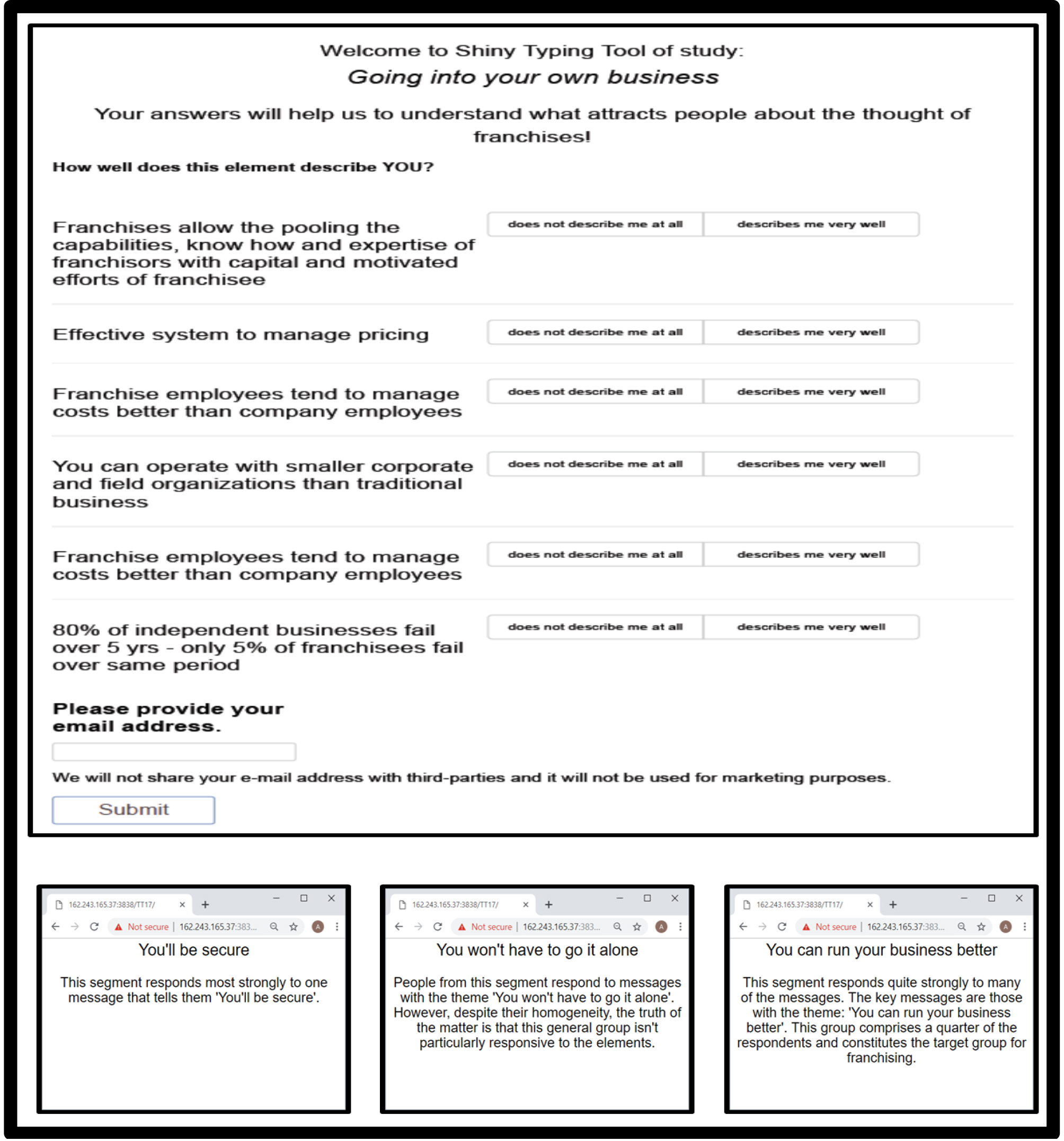

The phage display technology has provided the ability to create antibody libraries that contain a great number of phage particles, from which each one encodes and displays different molecules (106–1011 different ligands in a population of > 1012 phage molecules) [14]. Finding the most suitable molecule that reflects desired properties depends largely on proper conduction of biopanning experiments. It is extremely important especially in case of isolation of monoclonal scFv antibodies directed towards GPCRs heteromers. Because the kind of antibody must recognize spatial epitope that naturally occurs within heteromer structure, the key issue constitute such choice of experimental conditions which would ensure a natural environment in which heteromers may be formed. Generally the biopanning method is based on repeated cycles of incubation, washing, amplification and reselection of bound phage [14]. The target molecule may be immobilized on solid support as microtiter plate wells, PVDF membrane column matrix or immunotubes magnetic beads and even on whole cells [14]. In our case target antigen (defined heteromer) was presented on the surface of living cells. This kind of biopanning process is more complicated than in case when purified antigen is immobilized on the plate surface. A large number of variables can affect the behaviour of cells, which can translate into the quality of expressed heteromers and the key parameter here is the presentation of the ideal heteromer structure for the selection.

Several parameters affect biopanning efficiency, including antigen concentration, temperature, washing stringency (washing number and composition of wash buffer) as well as blocking and elution buffer composition [22]. Therefore, in the present work six various strategies (types A-F) of selection were described. Experiments were performed depending on the temperature (0 oC, RT, 37 oC), in the conditions that promote internalization process (type C), in the conditions where heteromer-bounded phages were isolated from interior of the cells after water lysis (type E), in the conditions where heteromer-bounded phages were displaced by clozapine (type F). Moreover during experiments washing stringency was maintained (Table 1). Additionally, two different cell line (CHO-K1 and HEK 293) were adopted to the procedure. Experiments were performed for attached cells as well as in the cells suspension. CHO-K1 cells are well attached to the surface than HEK 293 cells which makes them better for experiments conducted on plates where rigours washing steps are made. Comparison both used cell lines indicate that results obtained for such experiments using HEK 293 cells were definitely worse (Table 2 A,B). Probably most phages were lost during washing steps which was related to the easy detachment of cells from the plate.

Table 2. Titre of phages after each selection round (I-VI positive selection followed by negative preselection, VII – negative selection). Procedure performed on A) CHO-K1 cells, B) on HEK 293 cells.

|

A) CHO-K1 cell line |

|||||||

|

Selection type |

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

VI |

VII |

|

A |

1,4 ×105 |

2,3 ×107 |

2,8 ×108 |

4,4 ×108 |

– |

– |

6,1 ×109 |

|

B |

2,6 ×105 |

1,2 ×107 |

3,1 ×108 |

2,4 ×108 |

– |

– |

6,7 ×109 |

|

C |

4,0 ×103 |

2,1 ×106 |

1,9 ×106 |

3,2 ×108 |

– |

– |

6,4 ×109 |

|

D |

2,9 ×104 |

2,6 ×106 |

1,5 ×107 |

3.2 ×107 |

– |

– |

4,7 ×108 |

|

E |

1,9 ×103 |

0,5 ×106 |

0,9 ×106 |

1,2 ×107 |

– |

– |

2,1 ×107 |

|

F |

6,8 ×104 |

4,7 ×106 |

2,8 ×107 |

4,8 ×107 |

– |

– |

5,2 ×108 |

|

B) HEK 293 cell line |

|||||||

|

Selection type |

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

VI |

VII |

|

A |

0,9 ×104 |

5,3 ×105 |

1,8 ×106 |

1,2 ×106 |

2,3 ×106 |

1,7 ×106 |

6,8 ×106 |

|

B |

7,6 ×103 |

1,6 ×105 |

3,9 ×105 |

2,7 ×106 |

2,9 ×106 |

1,9 ×106 |

3,7 ×106 |

|

C |

3,0 ×103 |

2,7 ×104 |

1,9 ×105 |

2,3 ×105 |

2,7 ×106 |

1,9 ×106 |

5,4 ×106 |

|

D |

2,1 ×103 |

4,2 ×104 |

5,4 ×106 |

1,4 ×107 |

4,1 ×108 |

3,8 ×108 |

1,8 ×109 |

|

E |

0,9 ×103 |

2,1 ×103 |

4,5 ×104 |

6,7 ×104 |

9,5 ×103 |

1,2 ×105 |

4,8 ×105 |

|

F |

2,9 ×103 |

5,1 ×105 |

7,1 ×106 |

8,3 ×107 |

9,7 ×107 |

4,3 ×107 |

1,9 ×108 |

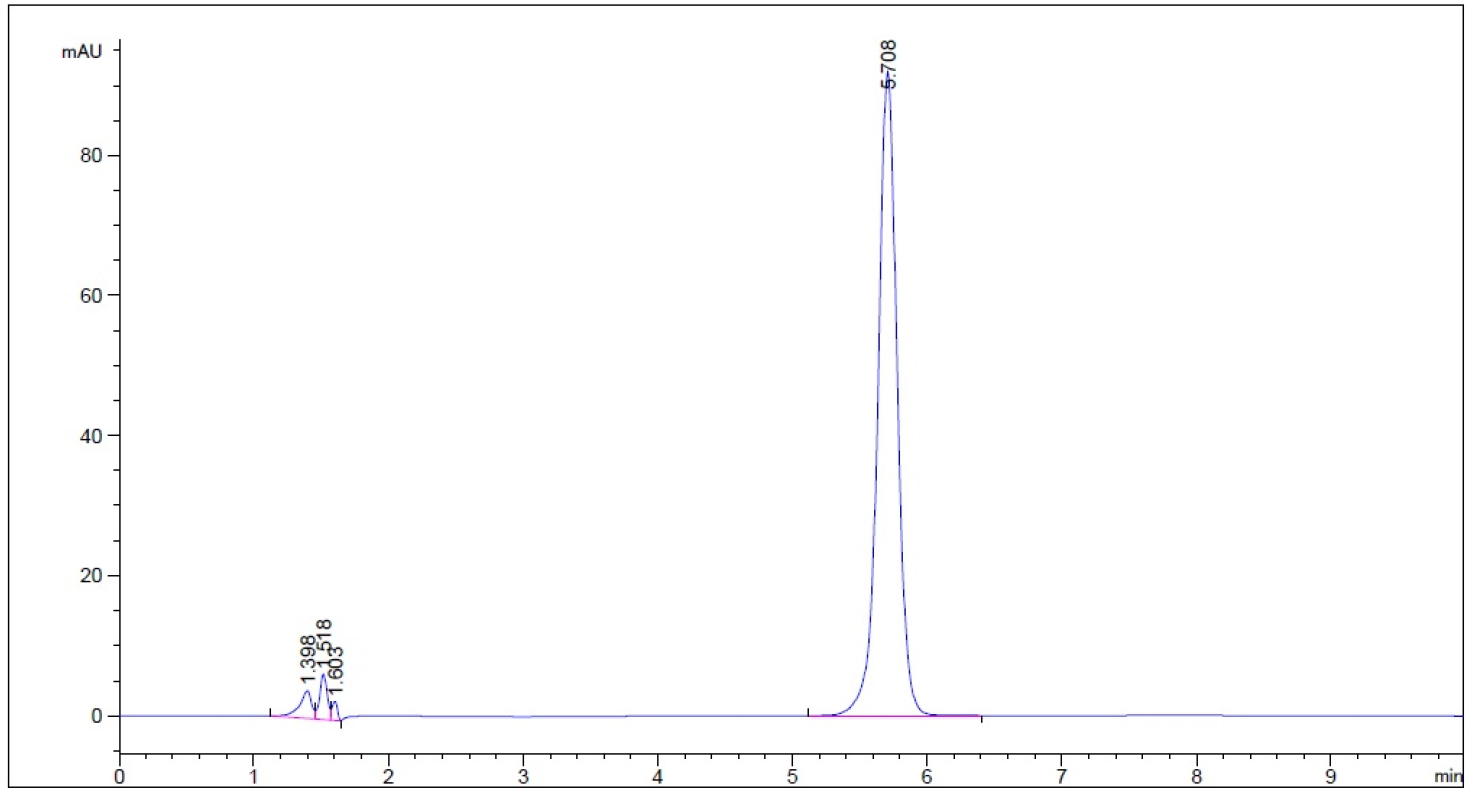

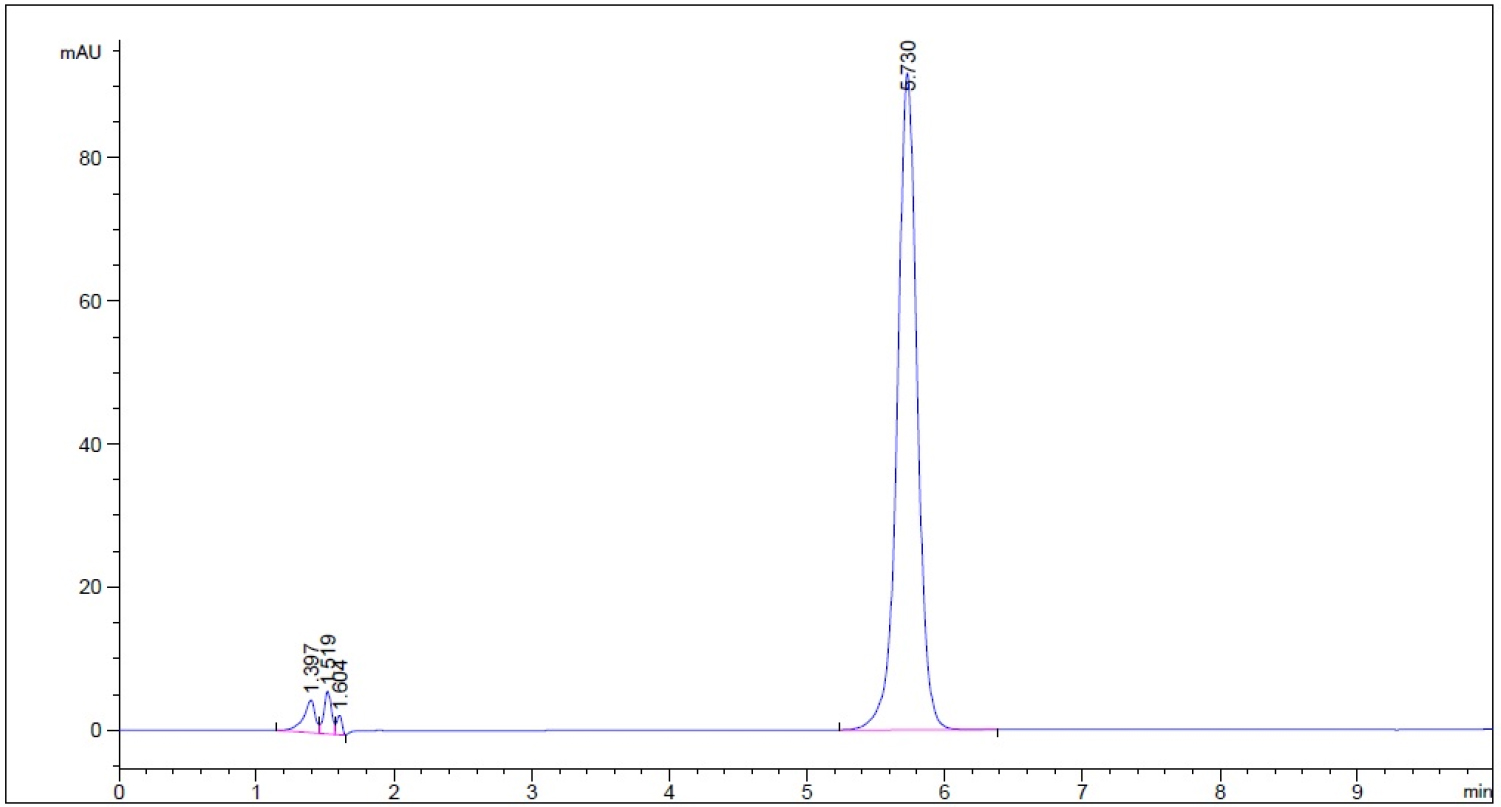

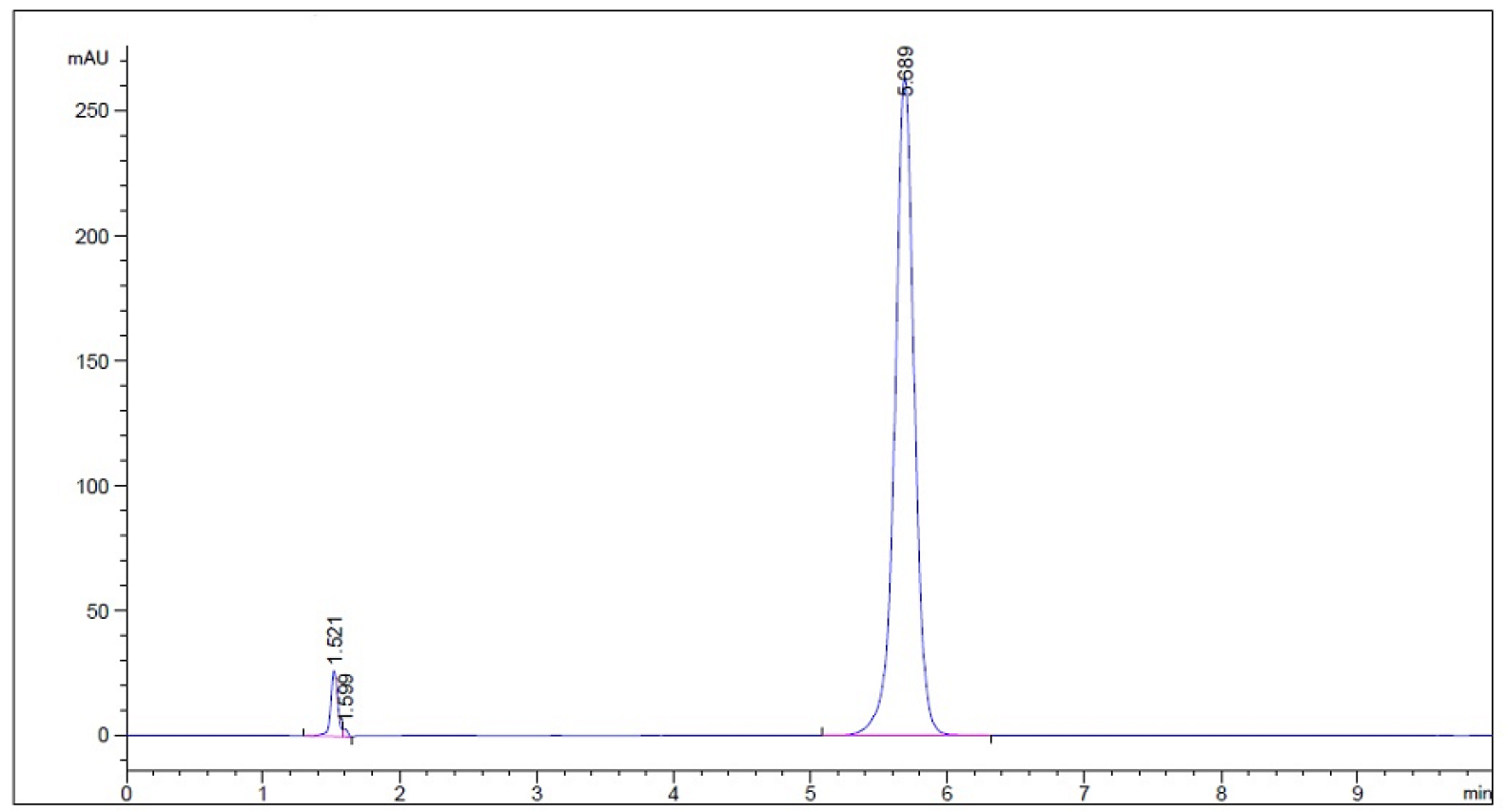

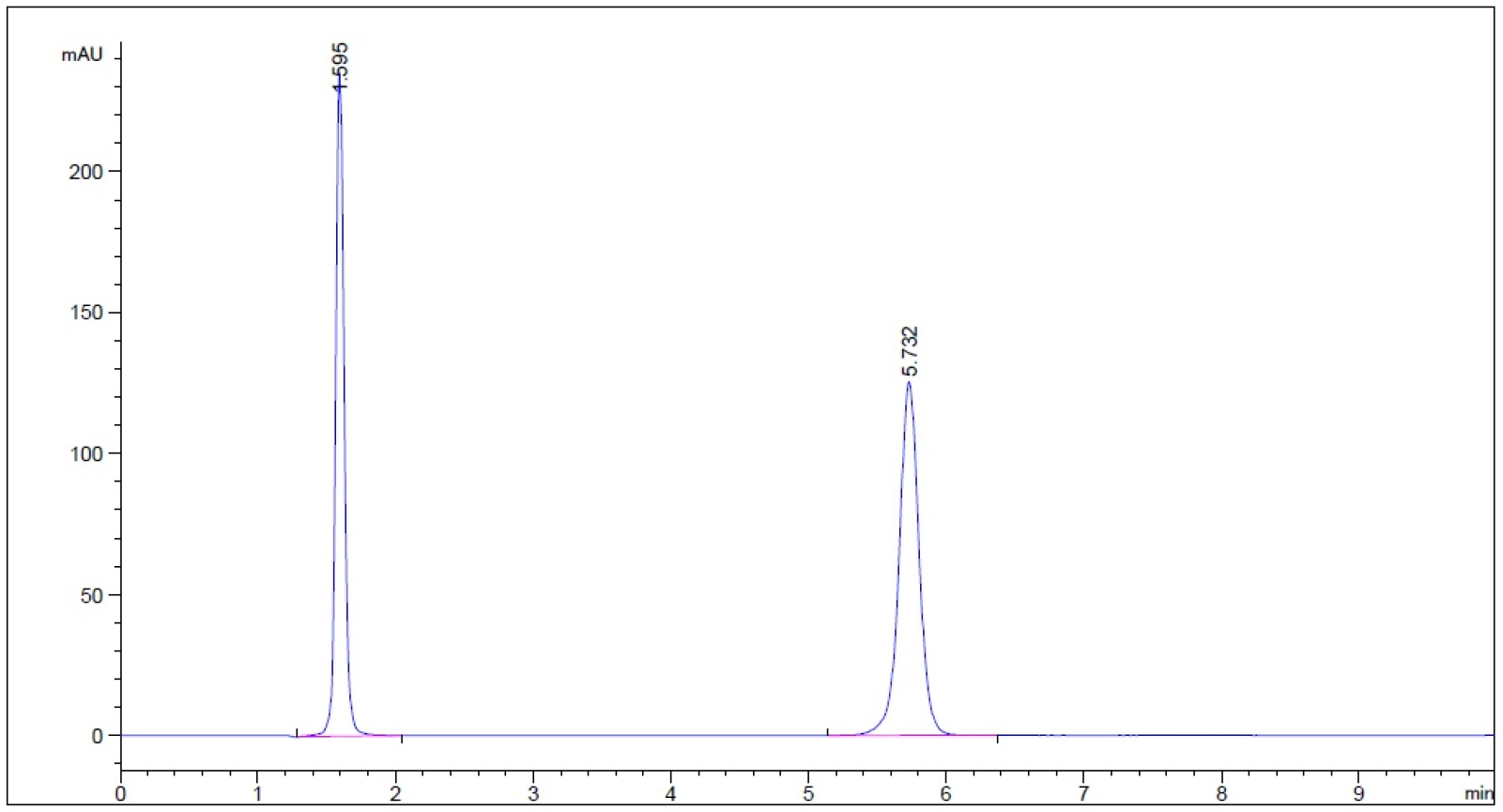

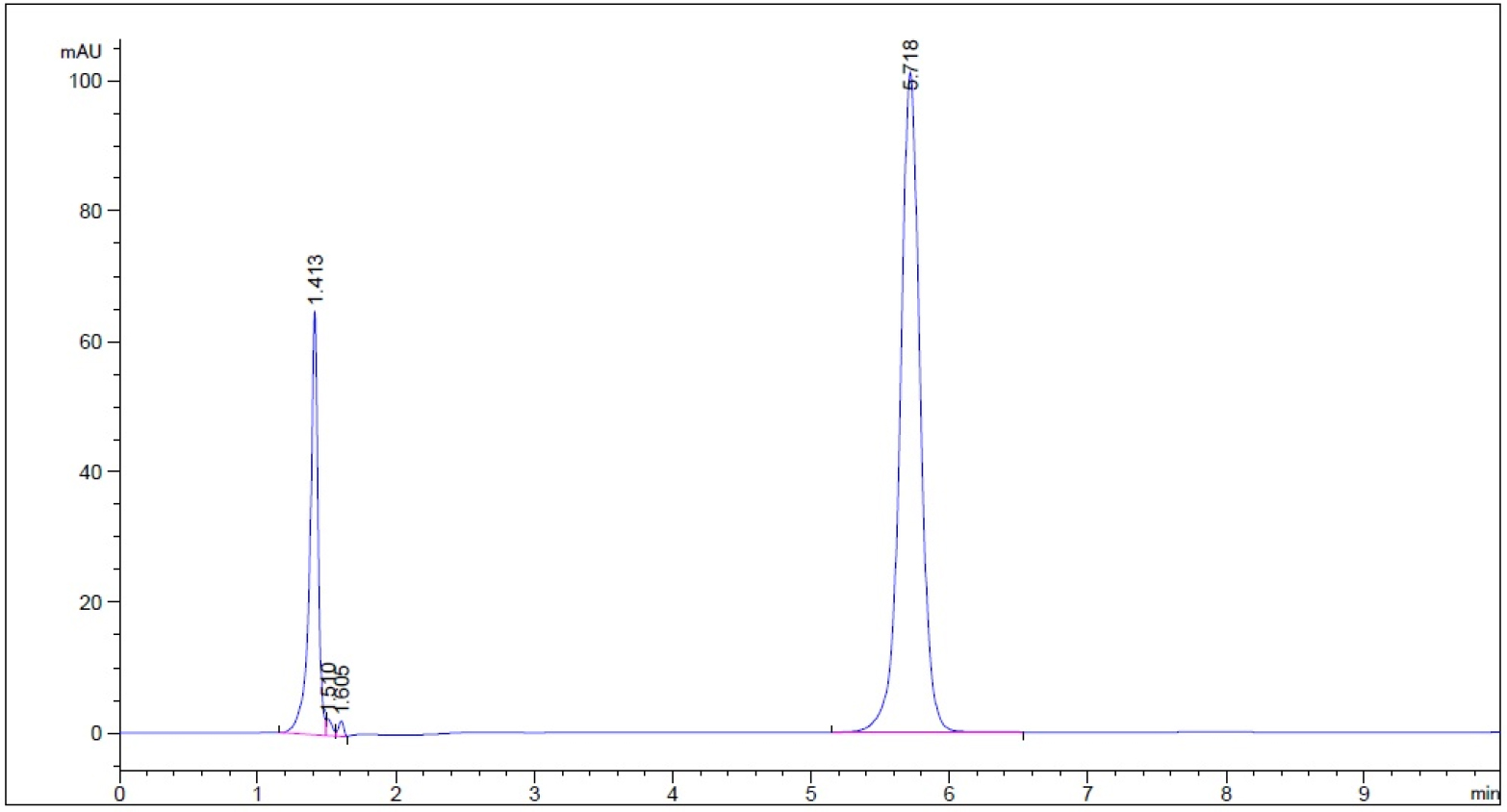

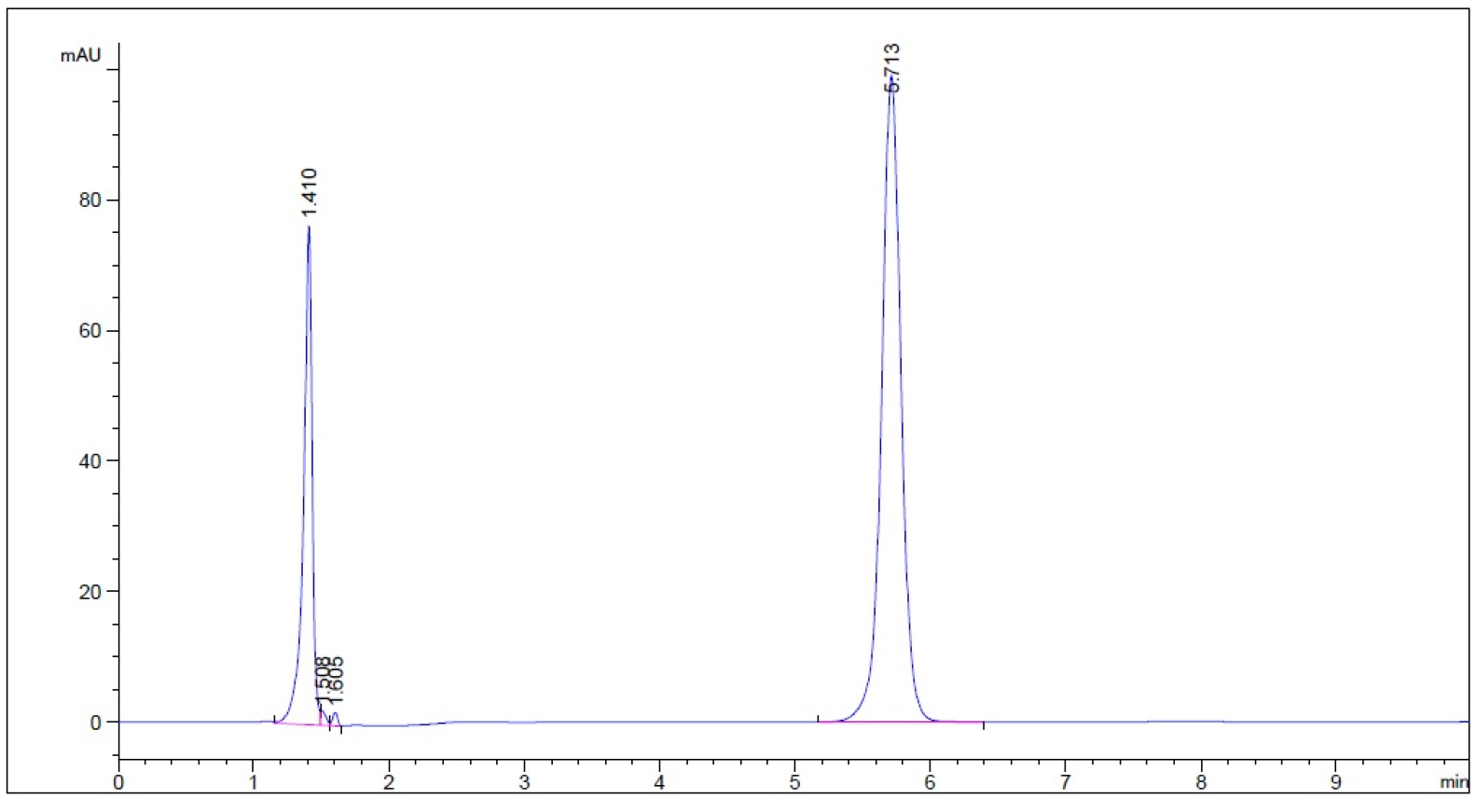

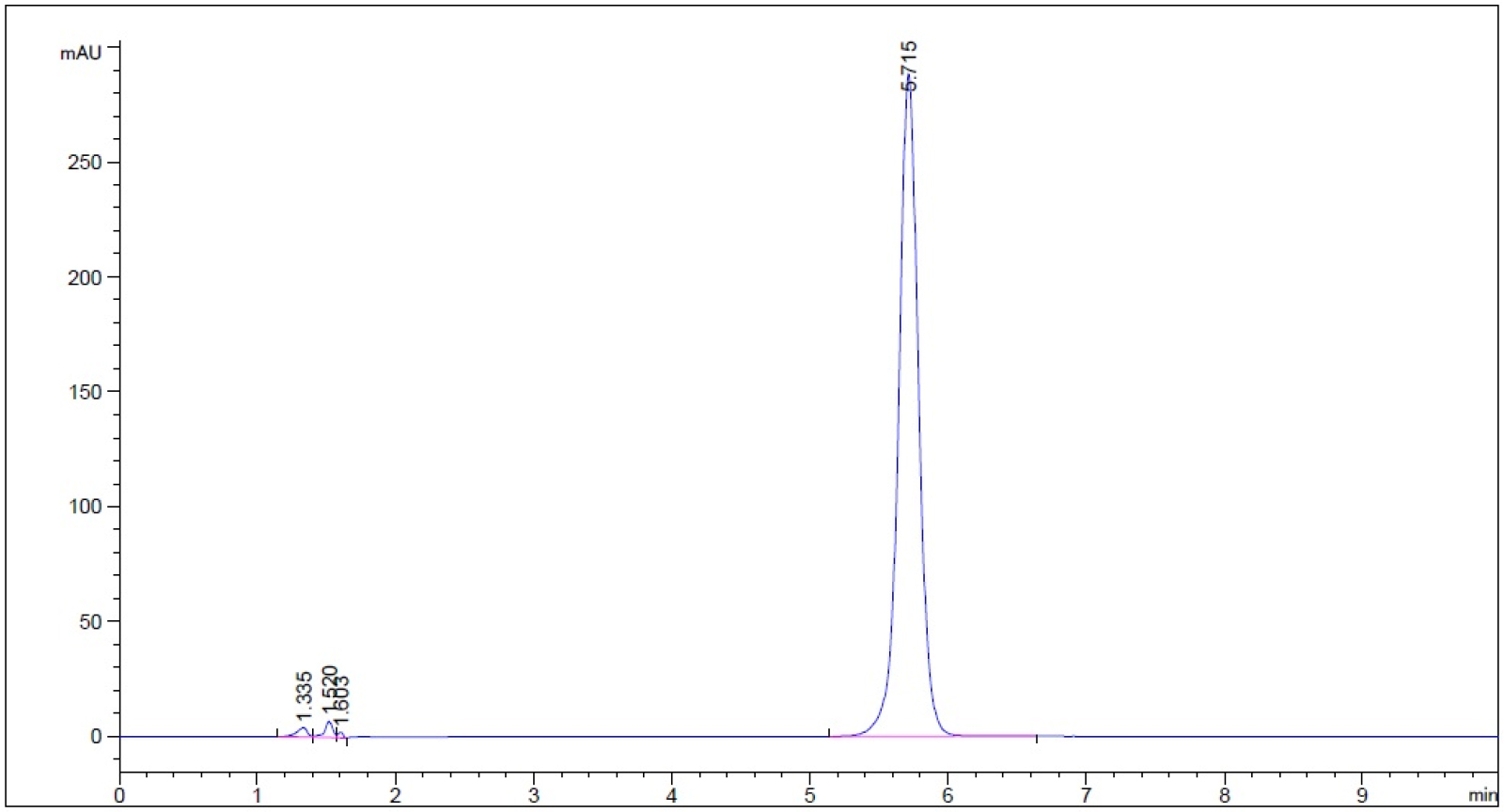

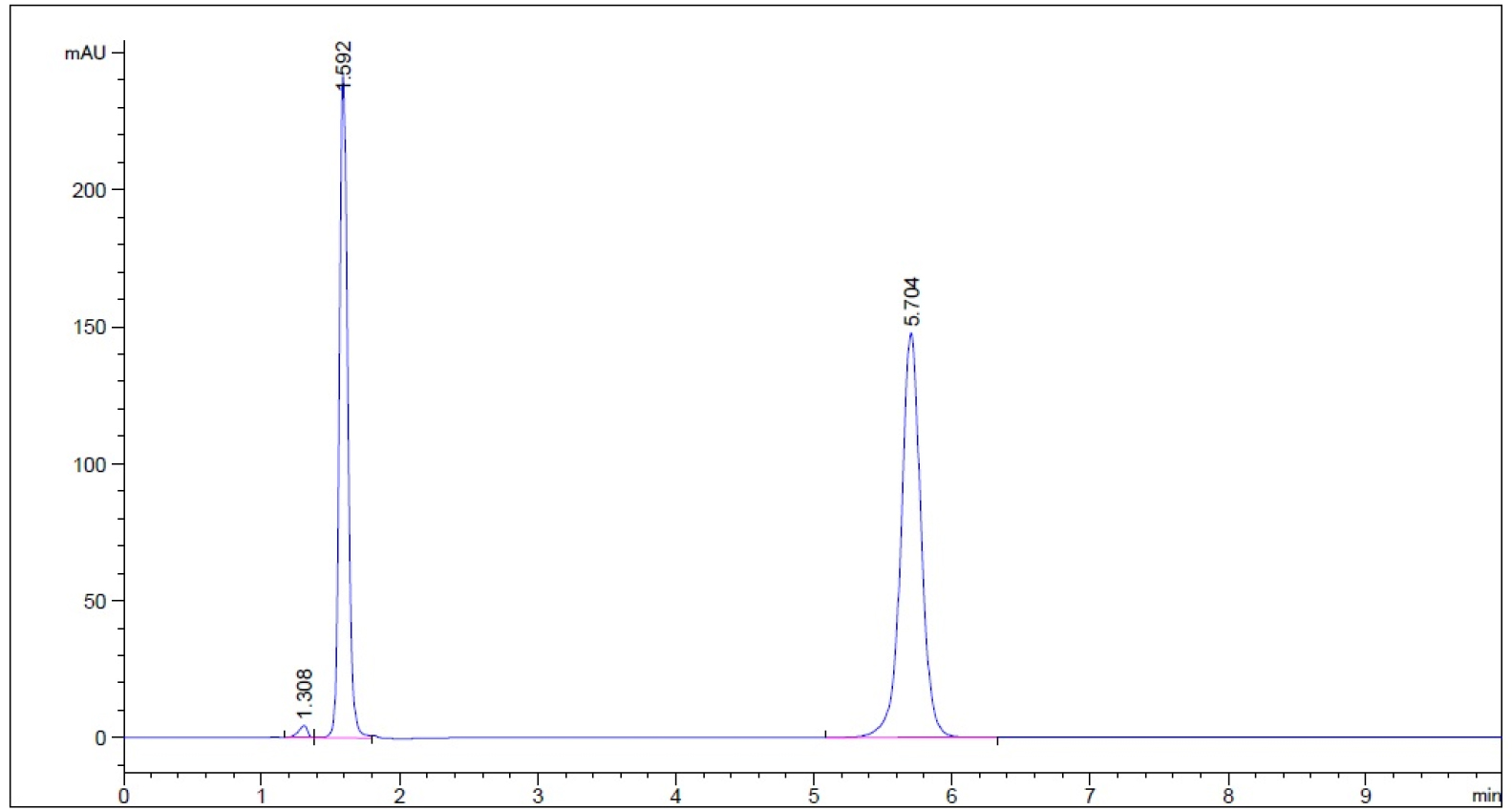

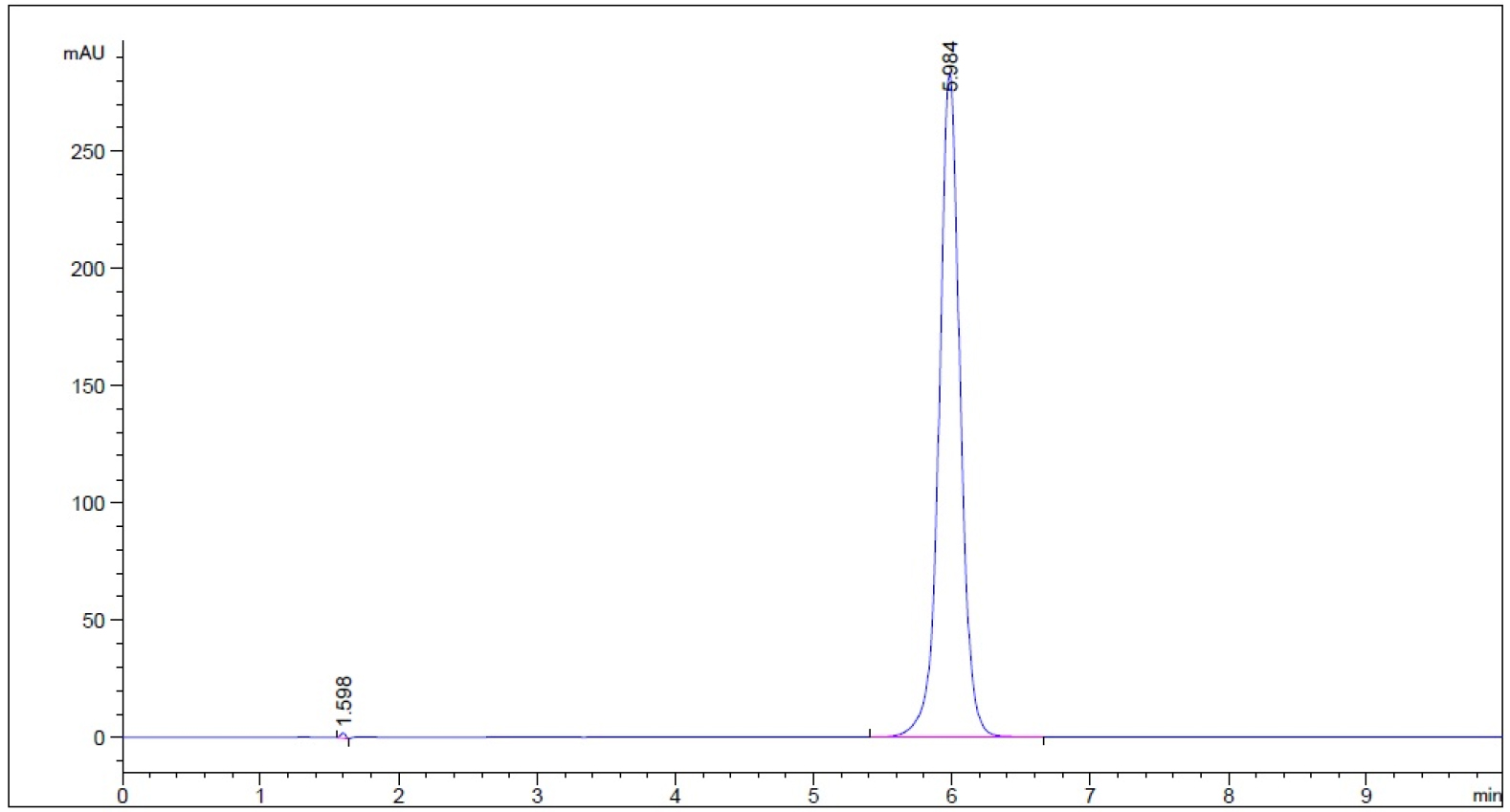

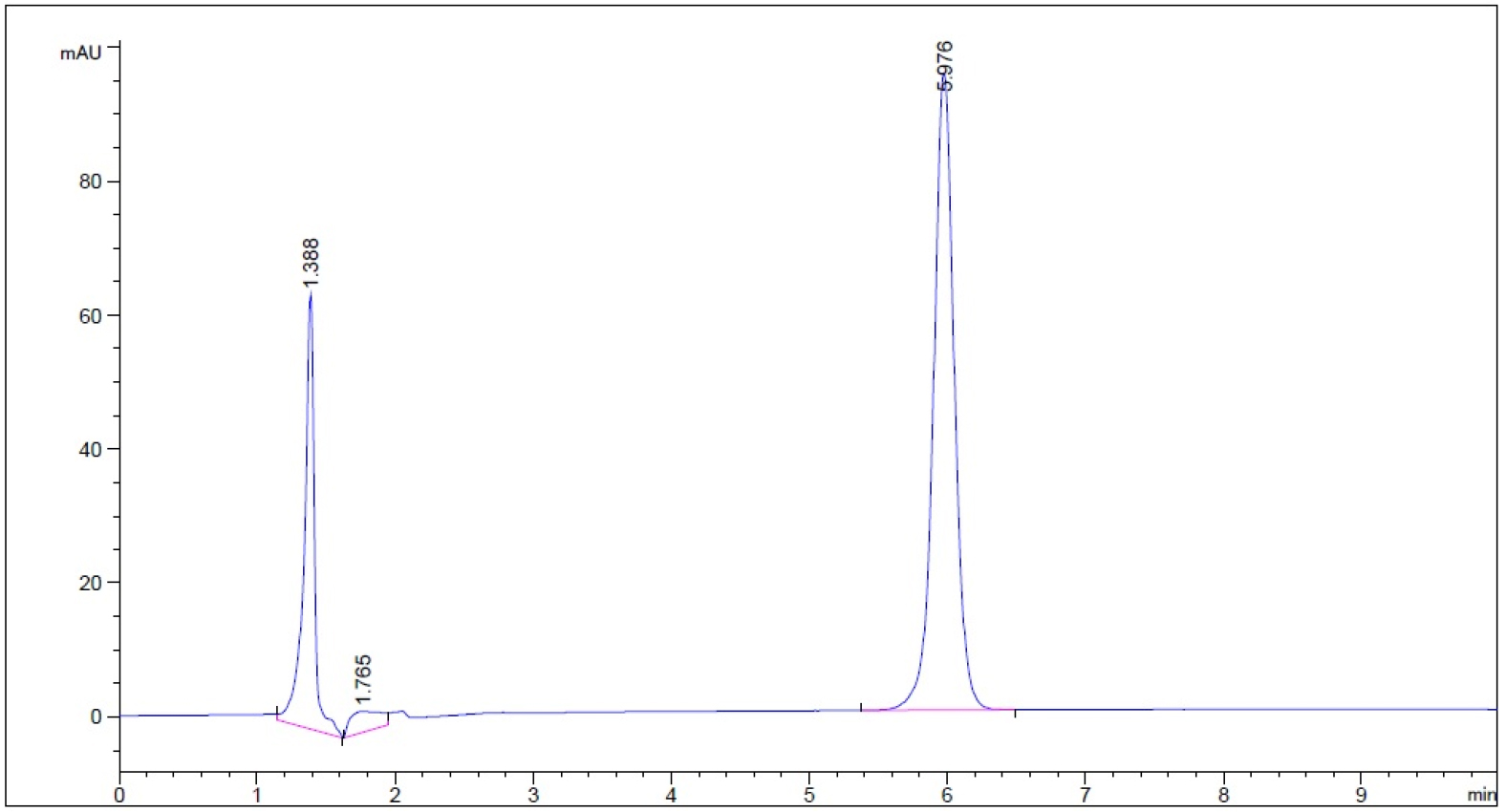

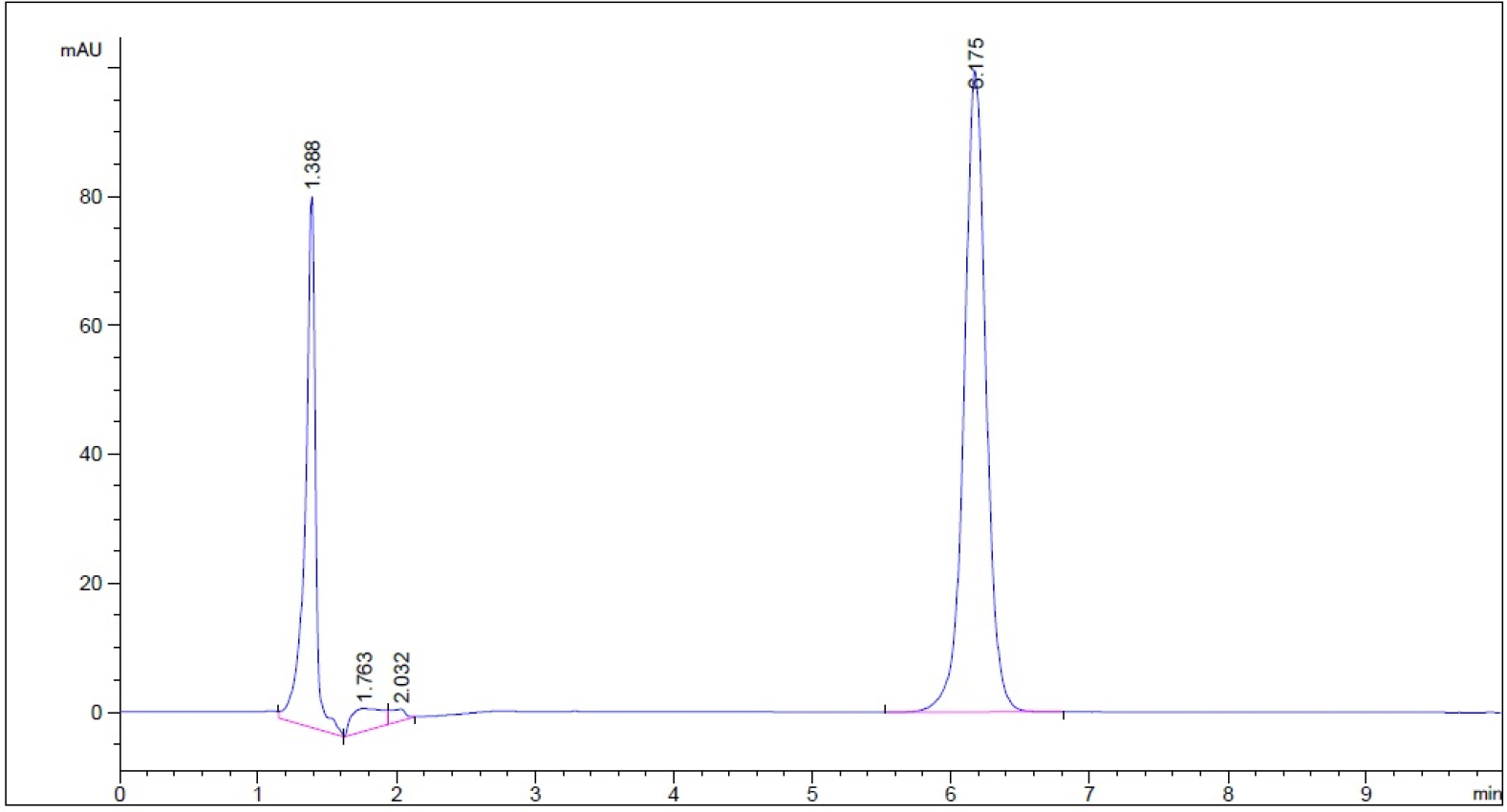

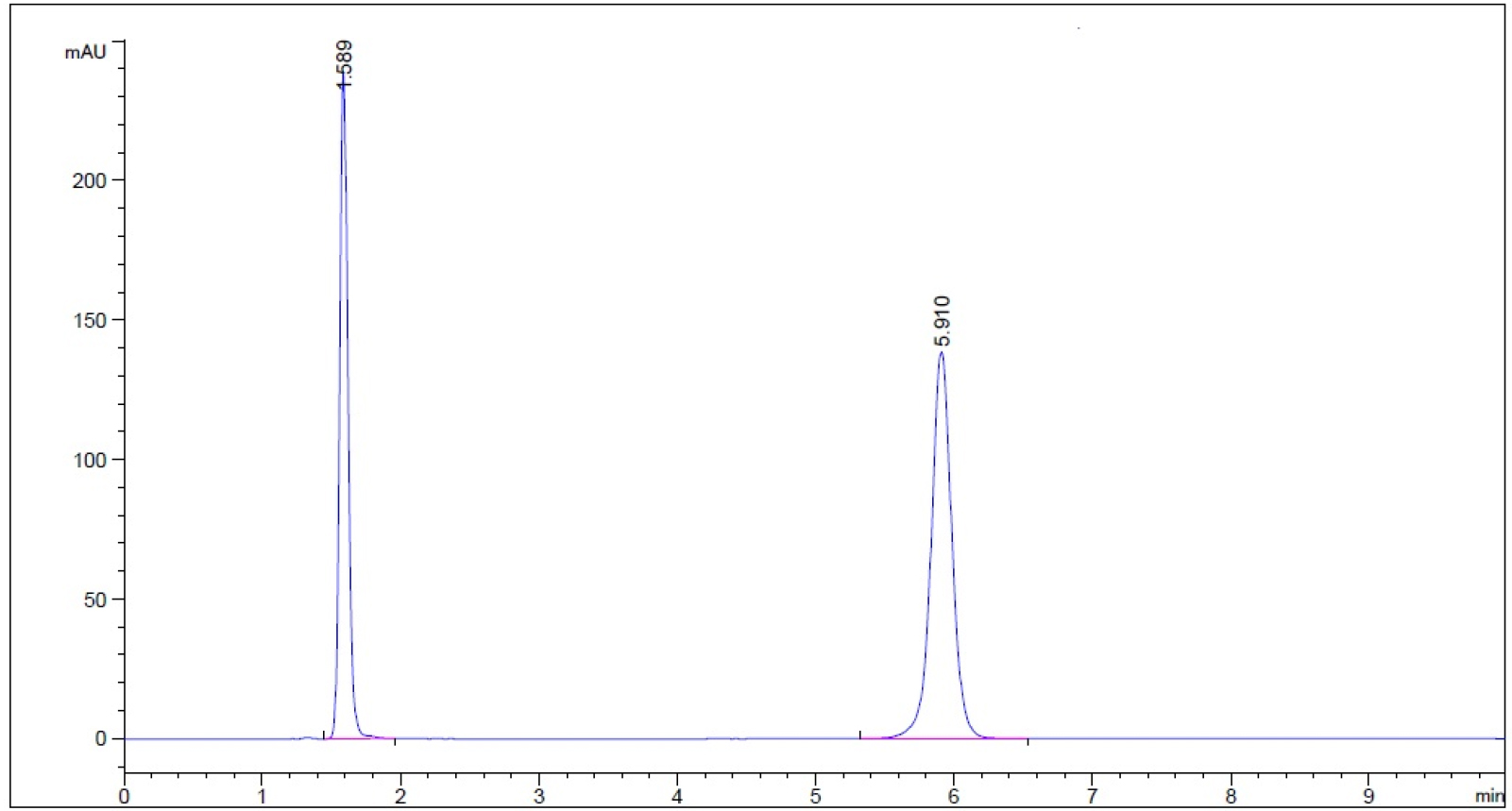

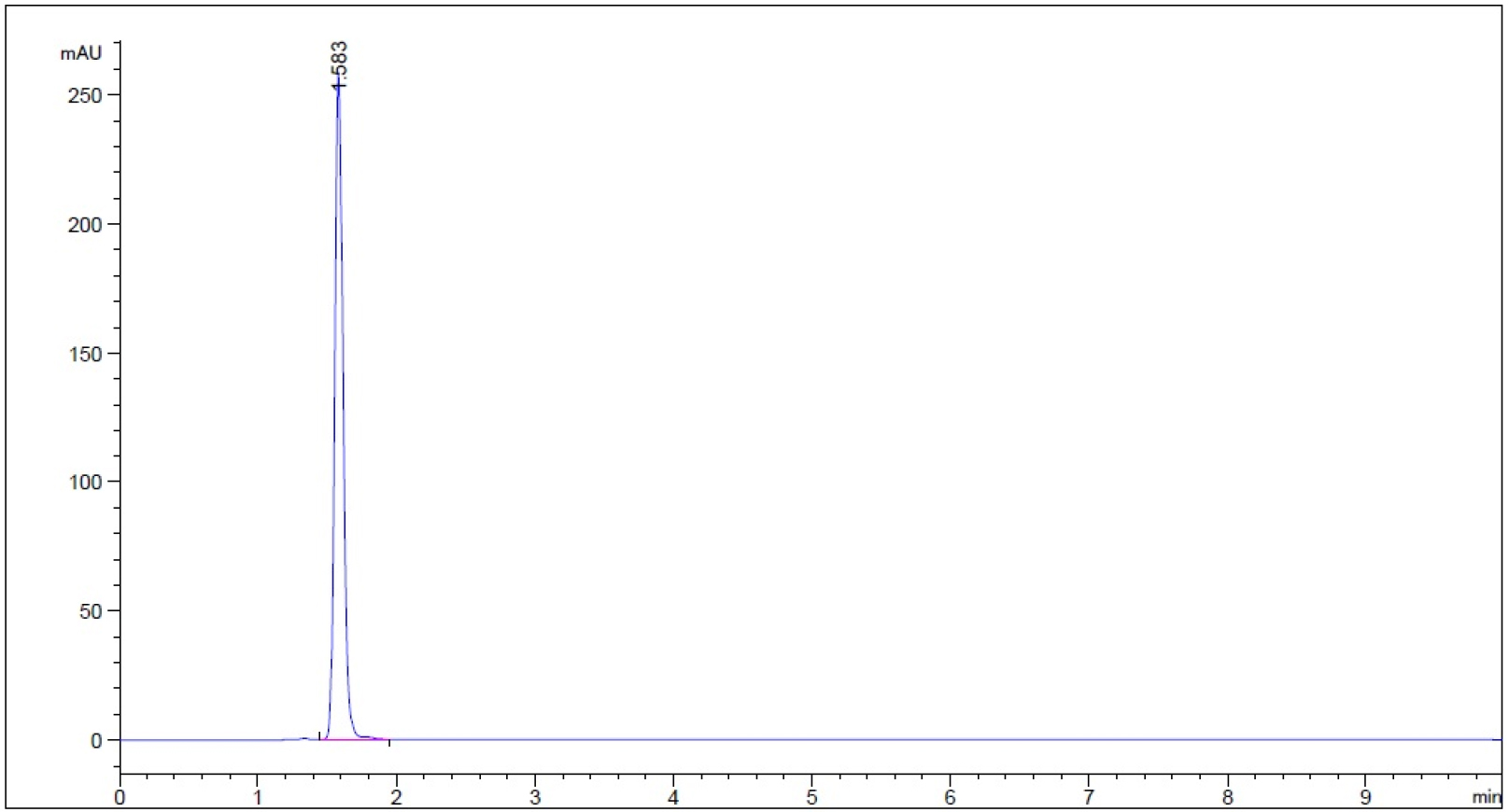

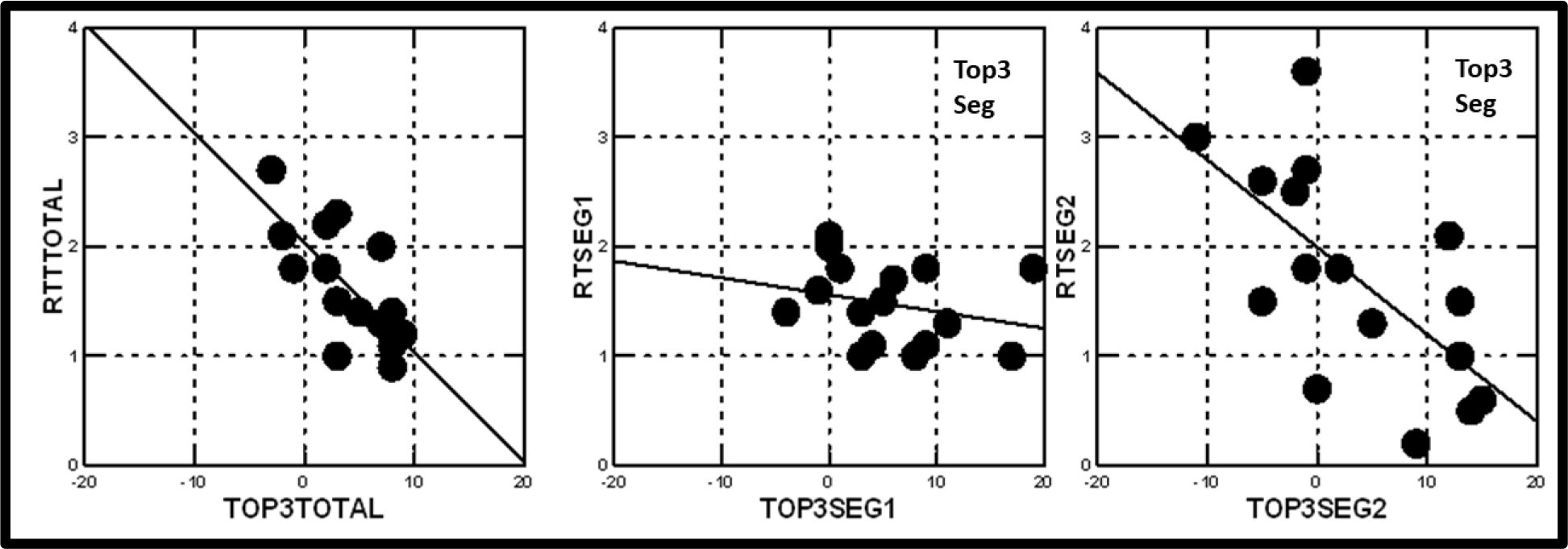

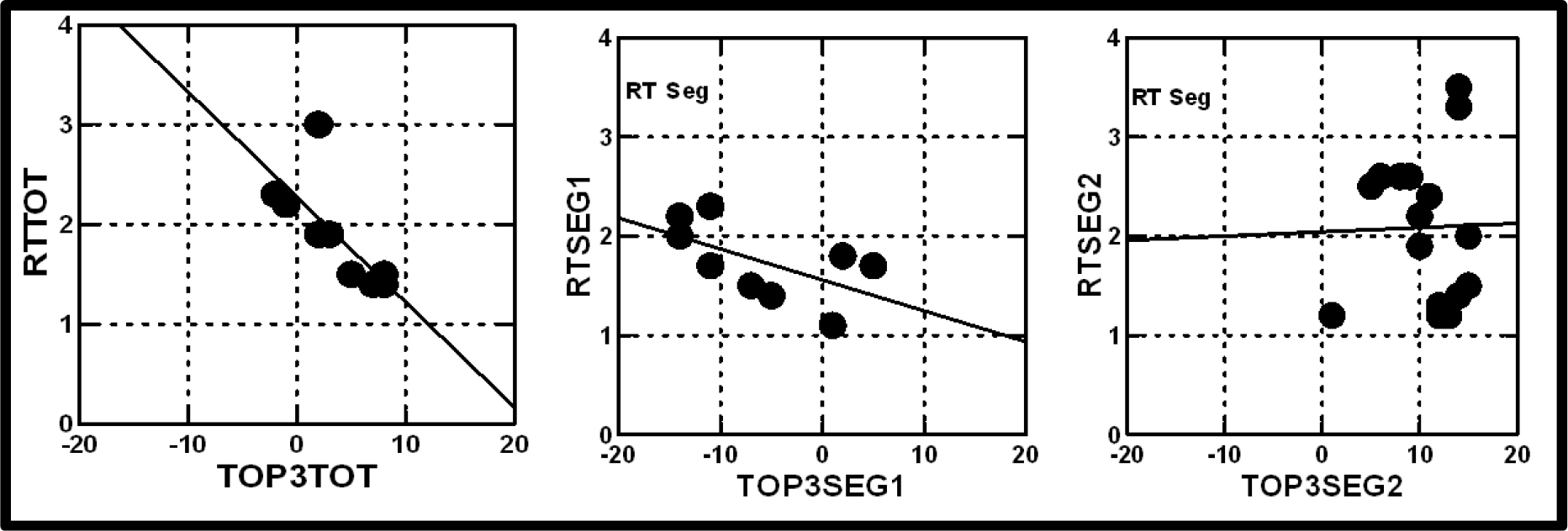

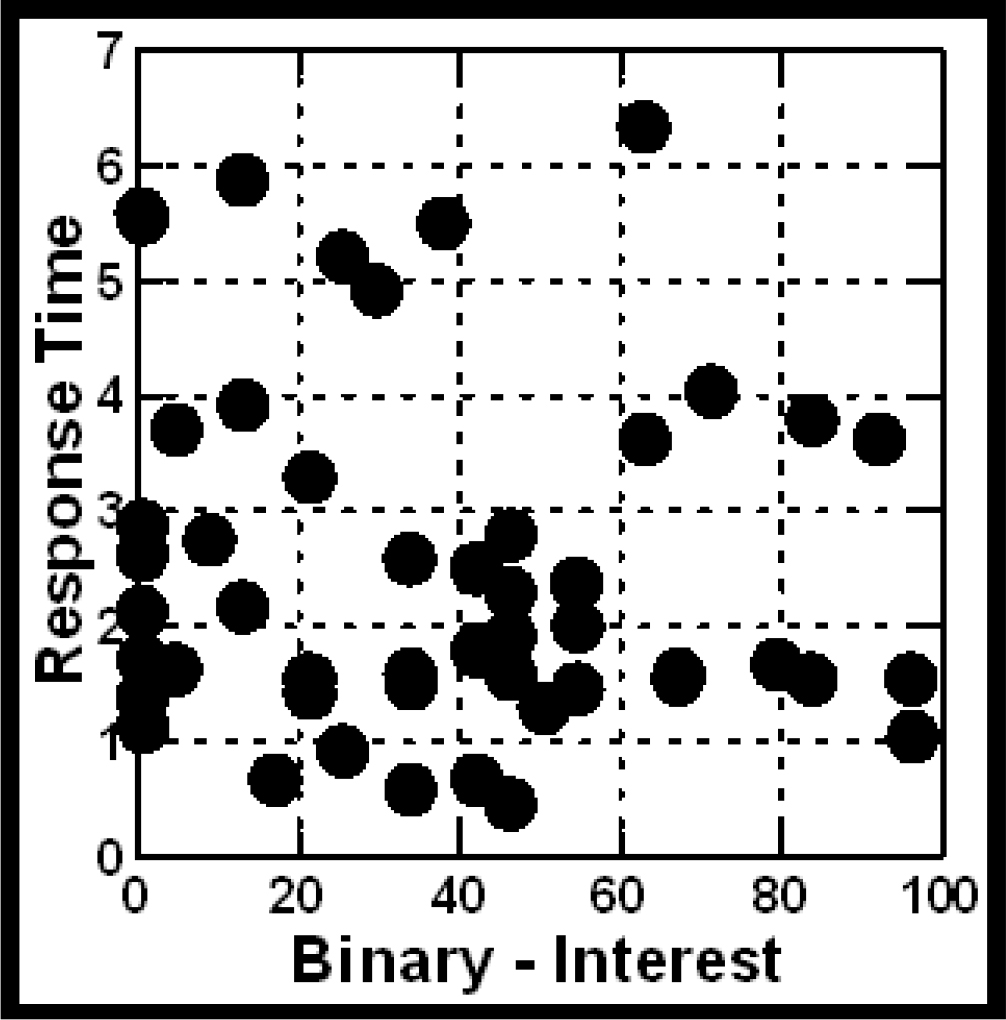

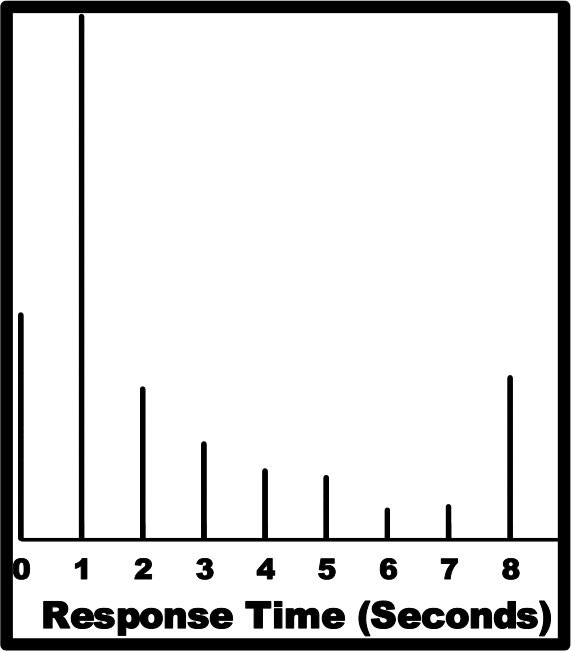

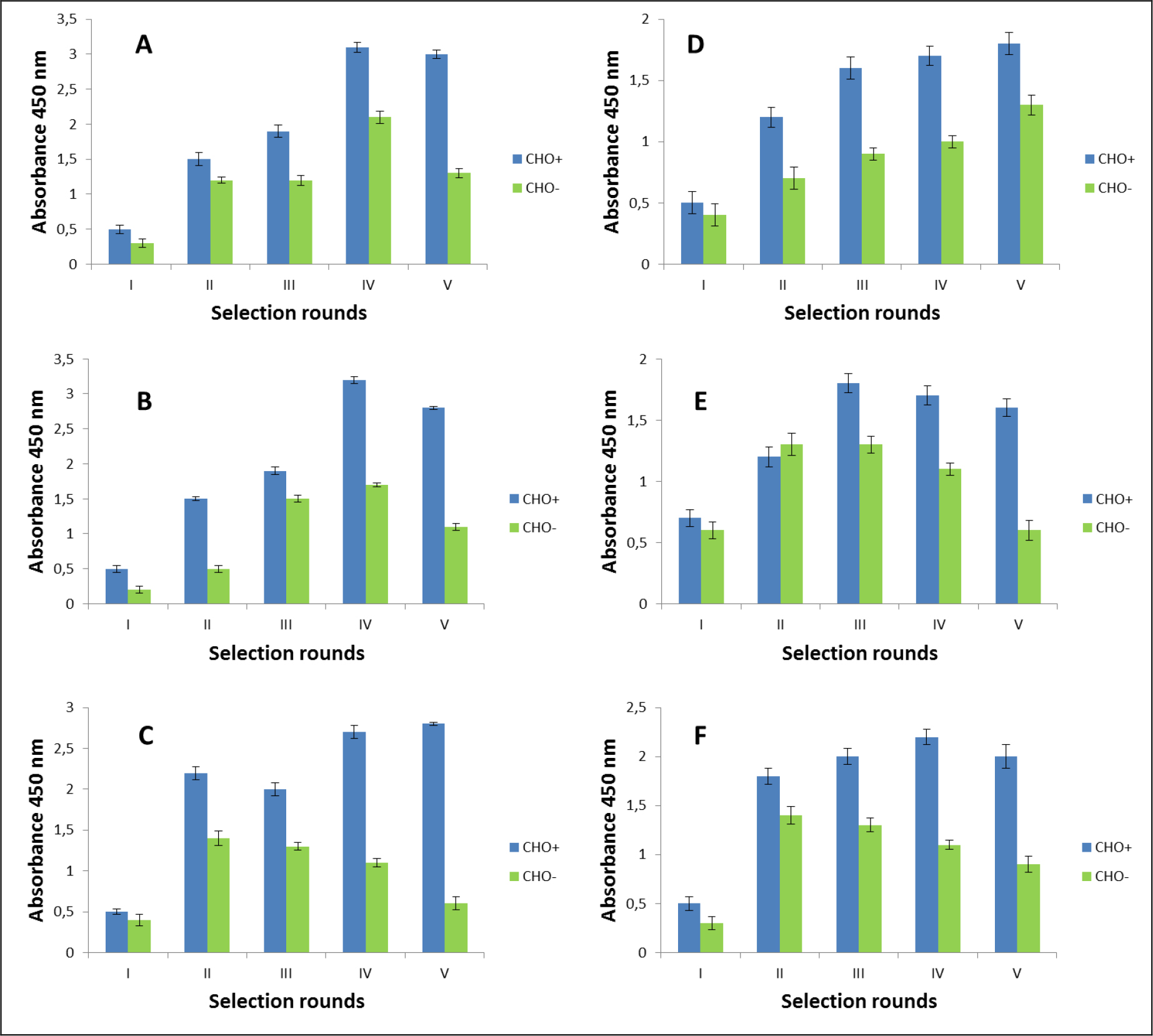

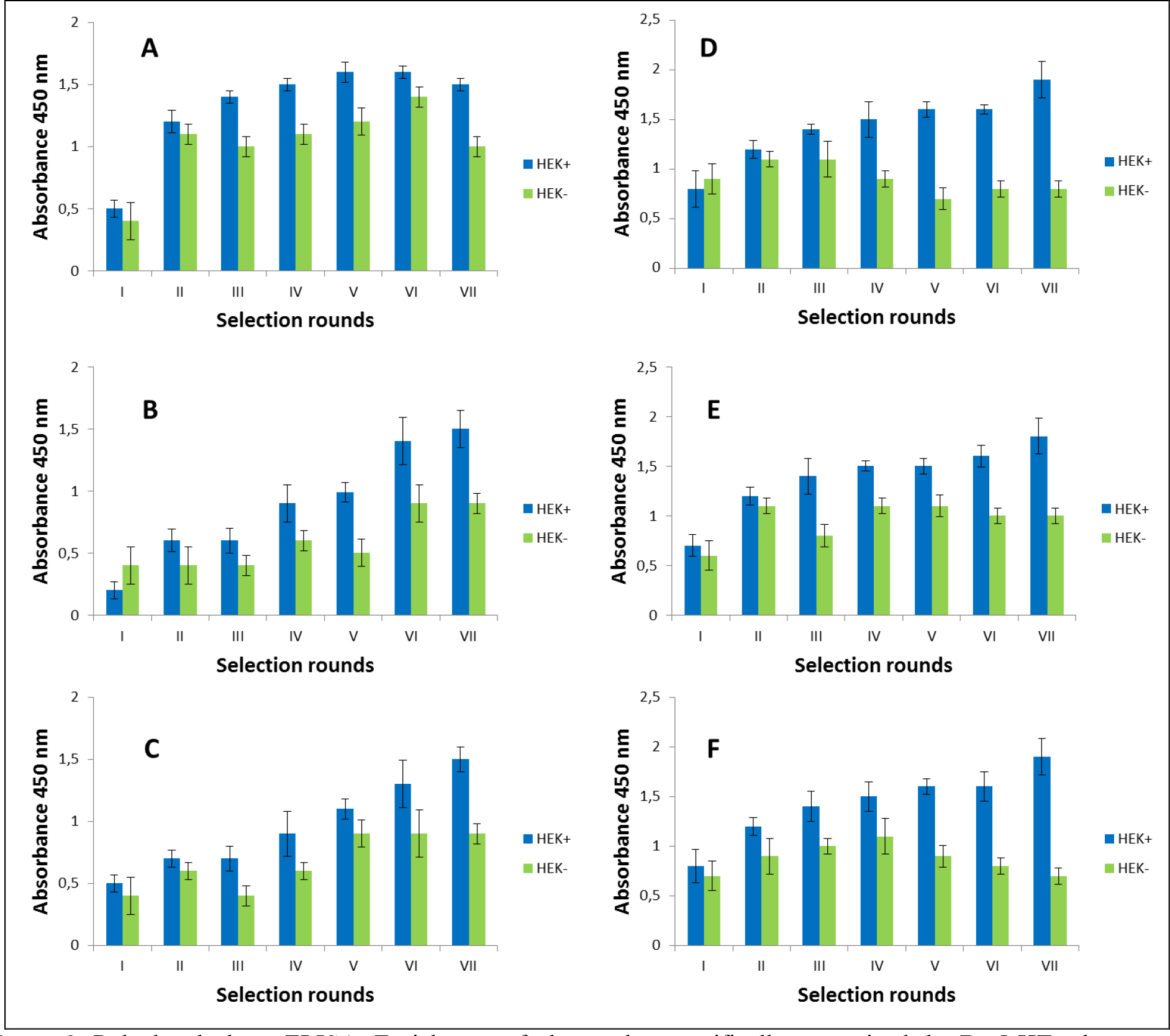

The selection process was assessed by monitoring the enrichment ratio and polyclonal phage ELISA. The increasing titre of phages as well as polyclonal phages ELISA results indicates the correctness of the biopanning process and corresponds with the enrichment of phages that specifically recognized the defined heteromer. Preselection conducted on negative cells provided initial elimination of phages exhibited binding affinity towards monomeric forms of receptors included into D2–5-HT1A heteromers as well as towards other molecules presented on the cell surface. It was very important and critical move because it enrich the amount of phages acquiring potentially, desired binding properties before the actual positive selection. Results obtaining during experiments performed without negative preselection was not as satisfying as expected (data not shown). The biopanning rounds were repeated until the obtained results (phages titre and polyclonal ELISA) related to positive (specific to defined heteromer) phages reached a plateau or started to decline (Figure 1,2, Table 2A,B). In case of experiments performed on CHO-K1 cells the plateau was achieved faster (after 4 round of selection) (Table 2A). For both cell lines. the level of polyclonal phages binding to positive cells increase with the number of selection. Moreover, in the initial rounds the difference between “phages” binding affinity to positive vs. negative cells was much smaller than in case of further rounds. Similarly to preselection, the last, only negative selection plays also an important role in the elimination of nonspecific bounded phages. As we can see the phages titre as well as binding specificity significantly increased after the last negative selection. Conducting further, only negative selection did not caused further increase of phages titre and binding affinity (data nor shown).

Figure 1. Polyclonal phage ELISA. Enrichment of phages that specifically recognized the D2–5-HT1A heteromer. Experiments performed in CHO-K1 cell line. A-F various selection types.

Figure 2. Polyclonal phage ELISA. Enrichment of phages that specifically recognized the D2–5-HT1A heteromer. Experiments performed in HEK 293 cell line. A-F various selection types.

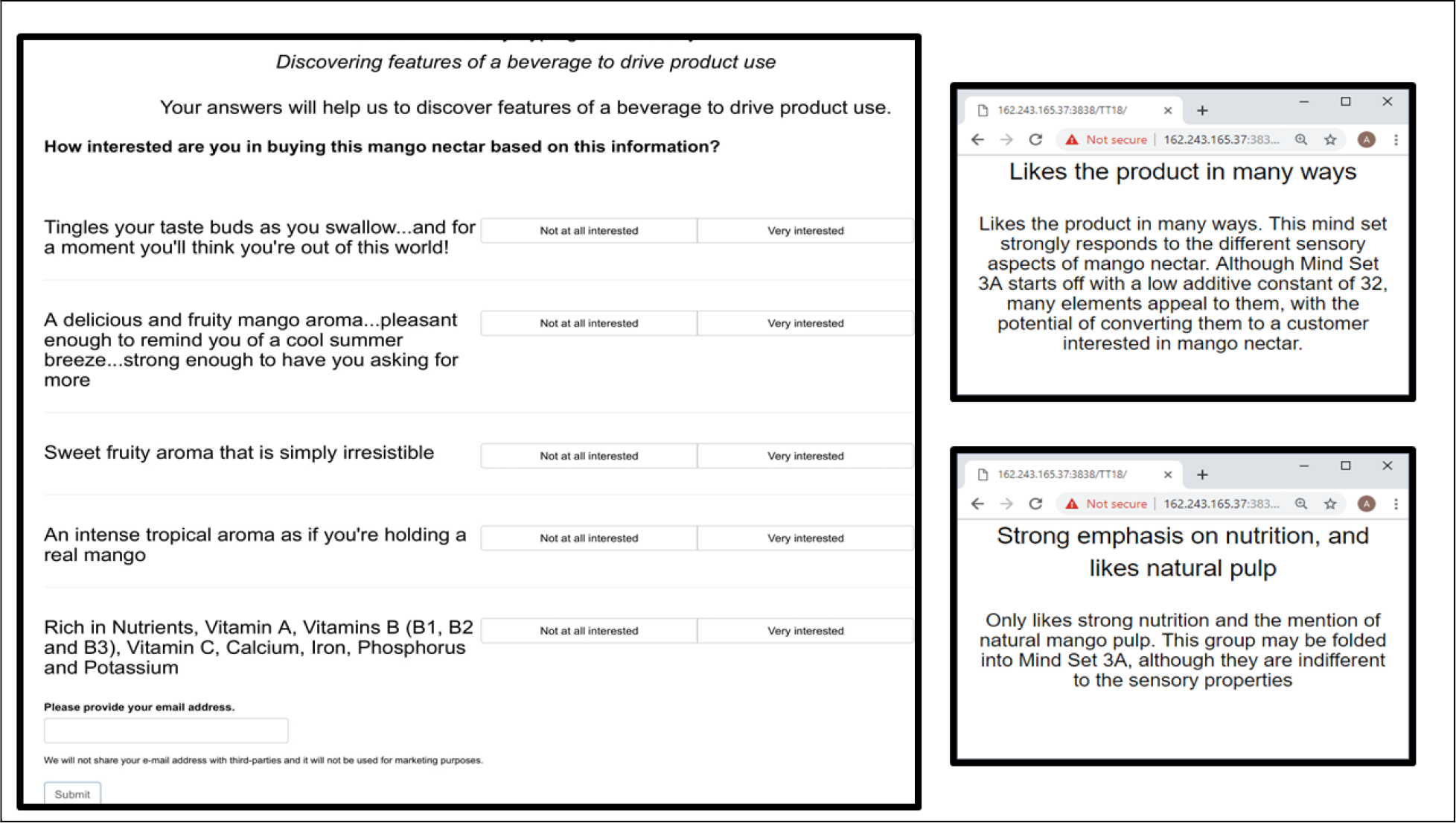

After the selection process, the specific binding of individual monoclonal phages to cells presenting defined heteromers was determined by monoclonal phage ELISA techniques. Such tests were conducted on various cell lines (CHO-K1, HEK293) expressing desired receptors in pairs or individually. The kind of experiment enable real identification of monoclonal phages displaying desired scFv molecules on the surface. About 1000 phages obtained after each type of selection were tested. Table 3 presents the results obtained for the three best phages for a given type of selection. The most satisfactory results (the highest heteromer specificity) were obtained in case of selection in conditions conducive to internalisation (type C) as well as in case of selection F where phages were displaced by clozapine. Clozapine is a pharmacological compounds which well-known affinity towards both D2R and 5-HT1AR [23–25]. Moreover its influence on various GPCRs heteromer formation has been documented [26–27]. As we can see here (Fig 1,2, Table 2), the titre of phages after final selection round (type F) was not as higher as in C case, however, the quality of isolated scFvs were very promising (Table 3).

Table 3. Binding level of various monoclonal phages specific to D2–5HT1A heteromer (results for 3 the best phages) presented on positive cells (CHO+ or HEK+ cells) in relation to: CHO-K1, CHO- cells – or HEK 293, HEK- , determined by ELISA technique. [R] –ratio of positive (absorbance 450nm positive cells) vs negative signal (absorbance 450nm negative cells).

|

Phage code |

CHO-K1 |

CHO- |

Phage |

HEK 293 |

HEK- |

|

Selection A |

|||||

|

5E/5r1 |

4.44 |

4.67 |

experiments were not carried out due to the poor results of polyclonal ELISA |

||

|

1F/5r4 |

3,54 |

3,21 |

|||

|

1G/5r3 |

5,26 |

4,31 |

|||

|

Selection B |

|||||

|

1E/5r1 |

5,01 |

5,76 |

experiments were not carried out due to the poor results of polyclonal ELISA |

||

|

10F/5r1 |

4,87 |

4,56 |

|||

|

2G/5r2 |

6,89 |

7,02 |

|||

|

Selection C |

|||||

|

10G/5r1 |

38.81 |

36.82 |

experiments were not carried out due to the poor results of polyclonal ELISA |

||

|

6H/5r2 |

16.87 |

16.32 |

|||

|

2D/5r4 |

22.57 |

23.86 |

|||

|

Selection D |

|||||

|

2C/5r2 |

6,77 |

7,32 |

1G/7r4 |

10,54 |

11,23 |

|

1E/5r3 |

3,73 |

4,77 |

1H/7r3 |

4,67 |

3,32 |

|

1G/5r3 |

5,21 |

4,88 |

1G/7r3 |

5,32 |

4,54 |

|

Selection E |

|||||

|

6D/5r1 |

2,32 |

2,76 |

10G/7r1 |

2,13 |

2,44 |

|

1C/5r3 |

3,91 |

2,98 |

1D/5r2 |

2,67 |

1,87 |

|

6F/5r2 |

3,76 |

1,76 |

4E/7r3 |

2,31 |

1,76 |

|

Selection F |

|||||

|

2H/5r4 |

16,21 |

14,32 |

4G/7r3 |

14,36 |

14,21 |

|

6D/5r4 |

15,44 |

13,21 |

5B/7r2 |

9,37 |

7,32 |

|

3C/5r1 |

10,17 |

10,09 |

7G/6r2 |

7,67 |

6,88 |

Comparison of the results obtained for both used cell lines indicates that in case of experiments performed on HEK 293 cells, effects were not as promising as in case of CHO-K1 cells. The visible differences appeared only at the monoclonal phages analysis stage. Phages, isolated based on selection on HEK 293 cells were less specific to desired heteromer (Table 3). The phenomenon, beyond the quality of the experiment itself, may be correlated with endogenous expression of D2R on the HEK 293 cell surface.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion presented results indicate the phage display technique as a valuable tool for isolation of human monoclonal scFv antibodies towards GPCRs heteromers. At the same time, they point to the key role of appropriate conditions during biopanning process. Based on our experience the best binding parameters were obtained for phages isolated after selection in the conditions promoting internalization process. A very important is also a proper choice of cell line dedicated to such procedure. Elimination of nonspecific bindings by negative preselection as well as the last round of the only negative selection constitutes a key point during the biopanning process.

5. Acknowledgment

The Faculty of Biochemistry, Biophysics and Biotechnology is partner with the Leading National Research Centre (KNOW) supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education. The work was also co-financed from European Union within Regional Development Fund – Grants for innovation – PARENT/BRIDGE Programme – POMOST/2011–4/5 and N N401 009640 project.

References

- Gomes I, Ayoub MA, Fujita W (2016) G Protein-Coupled Receptor Heteromers. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 56: 403–425. [crossref]

- Rozenfeld R, Devi LA (2011) Exploring a role for heteromerization in GPCR signalling specificity. Biochem J 433: 11–18. [crossref]

- Albizu L, Moreno JL, González-Maeso J, Sealfon SC (2010) Heteromerization of G protein-coupled receptors: relevance to neurological disorders and neurotherapeutics. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 9: 636–650.

- Fujita W, Gomes I, Devi LA (2014) Revolution in GPCR signalling: opioid receptor heteromers as novel therapeutic targets: IUPHAR review 10. Br J Pharmacol 171: 4155–4176.

- Derouiche L, Massotte D (2018) G protein-coupled receptor heteromers are key players in substance use disorder. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 29: 0149–7634.

- Kamal M, Jockers R (2011) Biological Significance of GPCR Heteromerization in the Neuro-Endocrine System. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 1 2: 2.

- Carriba P, Ortiz O, Patkar K (2007) Striatal adenosine A2A and cannabinoid CB1 receptors form functional heteromeric complexes that mediate the motor effects of cannabinoids. Neuropsychopharmacology 32: 2249–2259.

- Hamzeh-Mivehroud M, Alizadeh AA, Morris MB, Church WB, Dastmalchi S (2013) Phage display as a technology delivering on the promise of peptide drug discovery. Drug Discov Today 18: 1144–1157.

- Kushwaha R, Payne CM, Downie AB (2013) Uses of phage display in agriculture: a review of food-related protein-protein interactions discovered by biopanning over diverse baits. Comput Math Methods Med 2013: 653759.

- Hairul Bahara NH, Tye GJ, Choong YS, Ong EB, et al. (2013) Phage display antibodies for diagnostic applications. Biologicals 41: 209–216.

- Bradbury AR (2010) The use of phage display in neurobiology. Curr Protoc Neurosci Apr;Chapter 5:Unit 5.12.

- Cochran R, Cochran F (2010) Phage display and molecular imaging: expanding fields of vision in living subjects. Biotechnol Genet Eng Rev 27: 57–94.

- Smith GP (1985) Filamentous fusion phage: novel expression vectors that display cloned antigens on the virion surface, Science 228: 1315–1317.

- Bazan J, Calkosinski I, Gamian A (2012) Phage display-a powerful technique for immunotherapy: 1. Introduction and potential of therapeutic applications. Hum Vaccin Immunother 8: 1817–1828.

- Tan Y, Tian T, Liu W, Zhu Z, J Yang C (2016) Advance in phage display technology for bioanalysis. Biotechnol J 11: 732–745. [crossref]

- Pansri P, Jaruseranee N, Rangnoi K, Kristensen P, Yamabhai M (2009) A compact phage display human scFv library for selection of antibodies to a wide variety of antigens. BMC Biotechnol 9: 6. [crossref]

- Bird RE, Hardman KD, Jacobson JW, Johnson S, Kaufman BM, et al. (1988) Single- chain antigen-binding proteins, Science 242: 423–426.

- Barbas CF (2001) Phage display: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

- Lee CM, Iorno N, Sierro F, Christ D (2007) Selection of human antibody fragments by phage display. Nat Protoc 2: 3001–3008. [crossref]

- Lockman PR, Mumper RJ, Khan MA, Allen DD (2002) Nanoparticle technology for drug delivery across the blood-brain barrier. Drug Dev Ind Pharm 28: 1–13. [crossref]

- Frenzel A, Hust M, Schirrmann T (2013) Expression of recombinant antibodies. Front Immunol 4: 217. [crossref]

- Rahbarnia LL, Farajnia S, Babaei H, Majidi J, Veisi K, et al. (2016) Invert biopanning: A novel method for efficient and rapid isolation of scFvs by phage display technology, Biologicals 44:567–573.

- Newman-Tancredi A, Kleven MS (2011) Comparative pharmacology of antipsychotics possessing combined dopamine D2 and serotonin 5-HT1A receptor properties. Psychopharmacology 216: 451–473.

- Lukasiewicz S, Blasiak E, Szafran-Pilch K, Dziedzicka-Wasylewska M (2016) Dopamine D2 and serotonin 5-HT1A receptor interaction in the context of the effects of antipsychotics – in vitro studies. J Neurochem 137: 549–560.

- Meltzer HY, Huang M (2008) In vivo actions of atypical antipsychotic drug on serotonergic and dopaminergic systems. Prog Brain Res 172: 177–197. [crossref]

- Lukasiewicz S, Faron-Górecka A, Kedracka-Krok S, Dziedzicka-Wasylewska M (2011) Effect of clozapine on the dimerization of serotonin 5-HT(2A) receptor and its genetic variant 5-HT(2A)H425Y with dopamine D(2) receptor. Eur J Pharmacol 659: 114–123.

- Lukasiewicz S, Polit A, Kedracka-Krok S, Wedzony K, Mackowiak M, Dziedzicka-Wasylewska M. Hetero-dimerization of serotonin 5-HT(2A) and dopamine D(2) receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2010) 1803:1347–1358.