DOI: 10.31038/JMG.2019211

1. Abstract

Major scientific advances have recently shown that the 3’-UTR (UnTranslated Regions) of mRNAs play crucial roles in regulating post-transcriptional events, such as translational repression, RNA degradation and RNA intracellular localization. Specifically, the discovery of microRNAs and their ability of silencing genes via translational repression at 3’-UTRs have transformed the way we think about the limited roles of RNAs and are guiding us towards a whole new world of RNA-regulated biological events. Likewise, Ran GTPase is a fascinating molecule that affects diverse biological phenomena including macromolecular nucleocytoplasmic transport, cell cycle progression, and immune response. Mutational difference at the 3’-UTR of Ran, resulting in predictable changes in Ran protein and RNA localization, in its nuclear/ cytoplasmic ratio, and in Ran-mediated biological functions, will provide us a manipulable genetic means for not only understanding Ran-mediated biological functions, but also for treating diseases in which abnormalities in host immune response and Ran-mediated biological processes are the key features.

Key Words

Ran GTPase, NF-κB, Nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio, MicroRNA, siRNA, RNA localization, Nuclear transport, Immune response, Septic shock, Cardiovascular diseases, Cancer, AIDS, Biodefense, Review

2. Introduction

Scientific breakthroughs can transform the way we live, learn, do science and practice medicine. Recent wonders in the RNA world, especially the world of 3’-UTR (UnTranslated Region) of mRNA, have revealed a number of very exciting findings; each of which has the above revolutionary effects. The stories we are going to tell are also extremely revealing in that they represent lessons for budding young scientists to remember – that great discoveries may not get appreciated right away, and they often take time to show their majestic beauty.

When Fire, Mello and coworkers 1] announced the RNA interference (RNAi) technology – injecting worms (nematodes) with double stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) and observing gene silencing effects because of it, the scientific community recognized that it will be extremely useful to use it as an experimental tool for learning gene functions and potentially applying it to medical applications. Highly informative data at an impressive rate have been generated since 1998. Scientific curiosities have led to many questions, one of which is the biological significance of dsRNAs and whether they exist in nature. As it turns out, similar double stranded RNAs do exist in nature. In fact, wonderful surprises there are: 1] Such existence – the microRNAs (or, simply, miRNAs) – are present in living organisms as diverse as plants, bacteria, worms, and all the way up to humans, [2] They exist in abundance! How come they are discovered only now? God only knows! [3] They have great revolution potential, some of which are already evident in challenging or revising dogmas (see below). [4] Gene silencing by miRNA was discovered and reported in plants in 1990 [2, 3], and worms in 1993 [4], a long time ago! The genetic elements through which miRNAs exert their gene silencing effects are predominantly present in 3’-UTRs.

Ran GTPase is a unique member within a large family of G proteins, all of which are membrane associated. Unlike other G proteins, Ran does not associate with the cell membrane when it is present in the cytoplasm, and it prefers to stay in the nucleus at steady state. It is also known to play important roles in diverse biological phenomena, including cell cycle progression, spindle formation during mitosis, nuclear envelope assembly, and macromolecular nuclear transport [5–8]. Extensive studies have been carried out over the last 3 decades trying to understand how Ran plays such important roles in diverse biological phenomena. In 1996, Kang et al. showed that Ran is involved in another important biological phenomenon – host immune response against a bacterial product [9]. Using forward genetics approach, Wong and associates [10–12] further showed that the 3’-UTR of Ran’s mRNA plays a major role in altering the magnitude of host immune response against pathogenic substances. Expression of two Ran mutant alleles, differing from each other by a single nucleotide in the 3’-UTR, results in differential Ran protein and mRNA localization, Ran’s nuclear/ cytoplasmic (N/C) ratio, and hence host immune response. Since Ran is involved in diverse biological phenomena, this manipulable genetic change and hence its predictable corresponding changes in N/C ratio will be invaluable not only in uncovering a unique 3’-UTR mediated mechanism akin to that seen in developing embryos of lower vertebrates, but also in medical applications, as its in vivo delivery produced an efficacious outcome in mice, a problem not yet resolved in RNAi technology, has been demonstrated.

This article highlights important recent advances, especially those in mammalian systems. It is impossible to include all relevant articles, and the advances mentioned in this article have foundations and insights gained from fundamental discoveries using non-mammalian systems, some of which out from necessity are discussed here. Three important RNA regulations at the 3’-UTR of several genes are reviewed here; they include translational suppression, RNA degradation and RNA intracellular localization. Although absolutely clear mechanistic details are absent in any of these three types of RNA regulation, common principles governing each of them are evident. They include [1] the presence within the 3’-UTR of one or tandem repeats of the regulatory element (also called motif) to which more than one factor (RNA-binding proteins or miRNA complementary sequences) recognizes and binds; [2] changes in consensus sequence of the motif affecting the nature of this recognition or interaction; and [3] difference in binding affinity (or base-pairing) of various factors to a particular motif. These principal features dictate the nature and intensities of these molecular interactions and therefore the corresponding biological outcome.

3. Translational Repression

3.1. Conventional – the LOX (lipoxygenase)

Translational repression is the inhibition of protein synthesis without reduction of mRNA levels. One of the clearest examples for this is the regulation of 15- LOX mRNA in reticulocytes – precursors of red blood cells. LOXs are enzymes responsible for lipid degradation. Erythroid 15-LOX degrades phospholipids, hence internal membranes such as those of mitochondria, making room for hemoglobin accumulation during red cell maturation. LOX mRNAs are synthesized in reticulocytes during early erythropoiesis (red blood cell development) but their translation into the enzymes is suppressed until after the reticulocytes move to the blood circulation and mature into red blood cells. This repression has been shown, in reticulocytes and in vitro, to be due to the binding of 10 tandem repeats of a pyrimidine-rich 19-nt motif located within the 3’-UTR erythroid LOX mRNA by a 48kDa protein without reduction of its mRNA levels [13, 14]. The 48kDa protein is a complex of two hnRNPs (heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins) called K and E1. Release of this repression occurs when hnRNP K becomes phosphorylated by Src tyrosine kinase, abrogating its binding to the 19-nt motif [15].

3.2. Unconventional – the RNAi technology

Another very different type of translational repression is related to the discovery of dsRNA, called RNAi, for RNA interference technology. Introduction of long dsRNAs into nematode produces gene silencing effects [1]. How does it work? These dsRNAs are cleaved into short pieces of RNAs, each 20–25 nucleotides (nt) long, principally by an enzyme called Dicer (an RNA III endonuclease). These short RNAs, called siRNAs (small interfering RNAs), along with a protein complex called RISC (RNA induced silencing complex), match the target sequence motifs usually located at the 3’-UTRs of the gene to be silenced. After binding, mainly due to base-pairing via sequence complementation, repression of translation or degradation of target mRNAs ensues.

As pointed out earlier, this RNAi technology led to recognition of interest in miRNAs in terms of their biological significance and potential practical applications [16–19]. The first miRNA, lin-4, was discoved more than a decade ago in the roundworm, C. elegans [4, 20]. It is known to affect the timing and sequence of worm’s embryonic development. Mutant lin-4 worms were arrested at the L1 larval stage and could not develop further [21]. Its 61nt long RNA can form a stem loop (also called a hairpin) structure, which is recognized and processed by the enzyme Dicer to produce a 22-nt RNA. This short RNA has antisense complementarity with multiple sites (or motifs) on the 3’-UTR of lin-14 gene, and its base pairing to these motifs reduces the production of LIN-14 protein. Since reduction of LIN-14 protein triggers the transition from cell divisions of the first larval stage to those of the second, alteration of LIN-14 protein levels explains lin-4 mutant worms arrested at L1 larval stage.

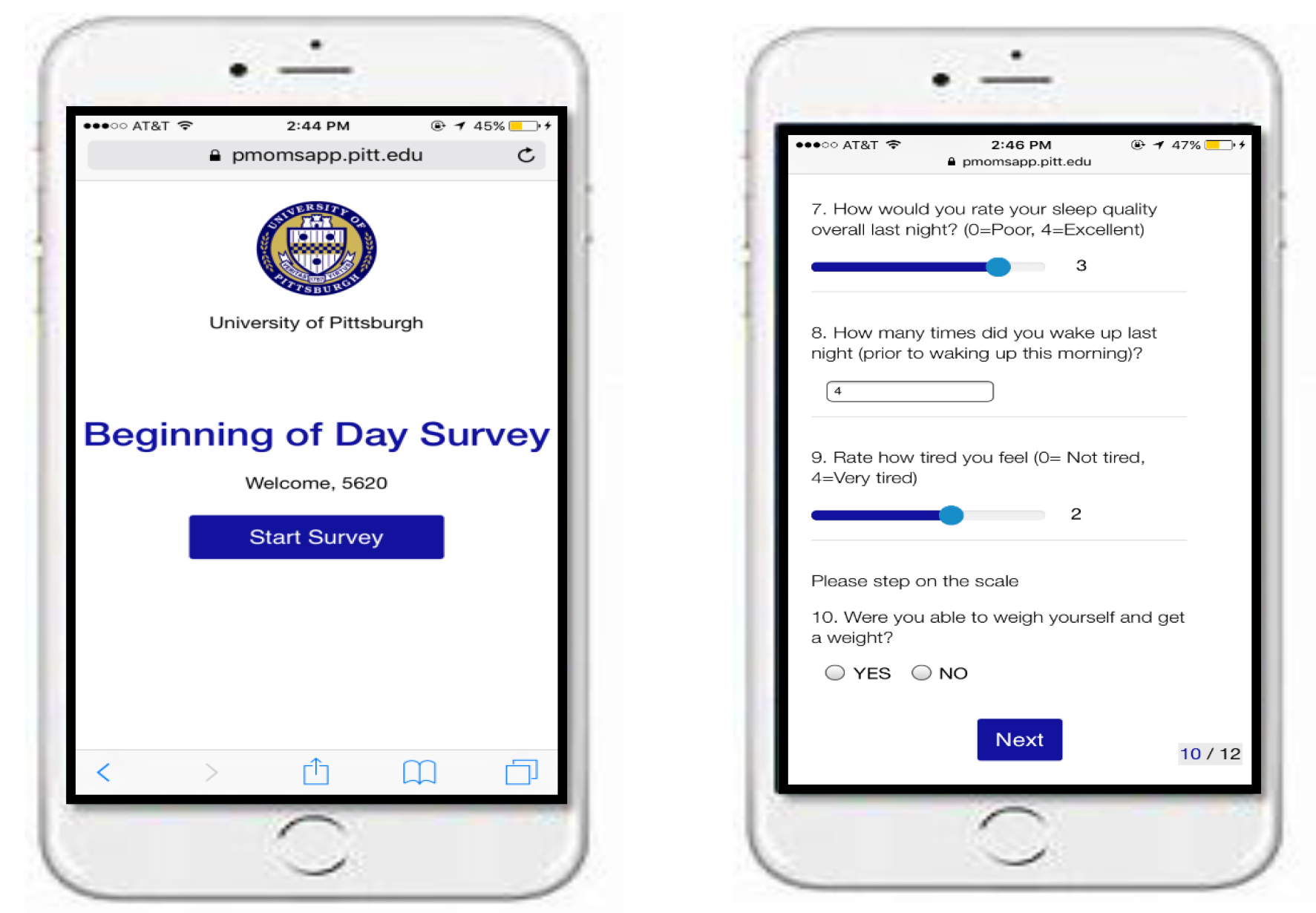

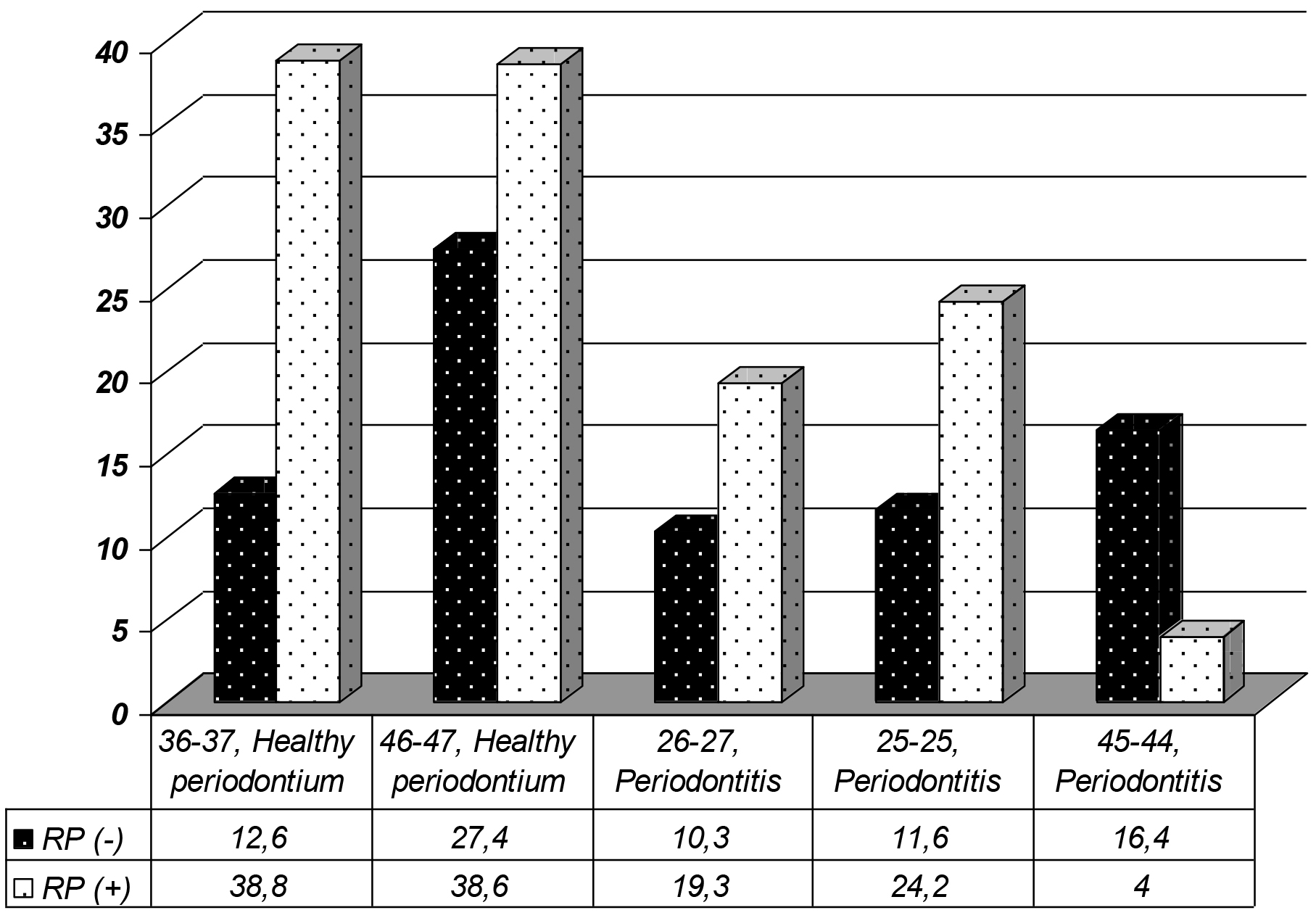

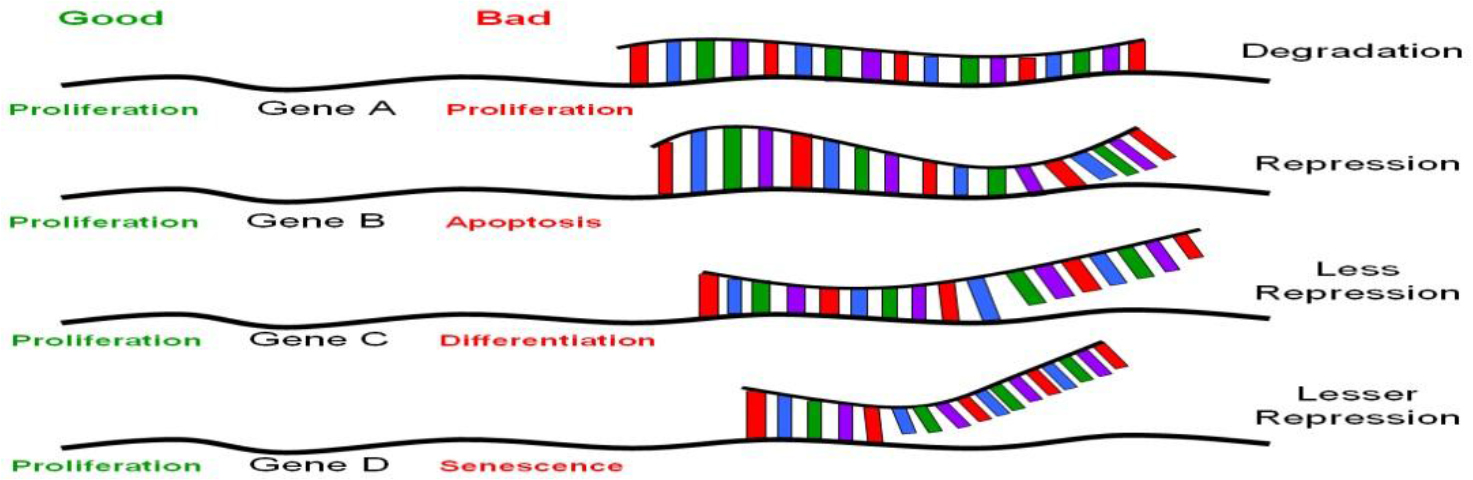

MiRNAs are similar but not identical to siRNAs; the latter are mostly created experimentally, as discussed above; other siRNAs are present in the genome as endogenous siRNAs. MiRNAs differs from endogenous siRNAs in a number of ways. While miRNAs come from (Figure 1) Perfect sequence complementation with target motif results in RNA degradation. Near-perfect sequence complementation results in translational repression, less repression occurs with progressive decrease in sequence complementation. For therapeutic application, the power of RNAi rests on perfect sequence complementation with the target sequence motif. Recent evidence suggests that this may not be so. Therefore, theoretically, a particular siRNA recognizing specific motifs on a set of genes (mRNAs) whose products have similar biological functions would be ideal (such as targeted mRNAs all of which encode for proteins involved in proliferation, marked in green). Conversely, a particular siRNA that targets a mRNAs encoding for proteins involved in various different biological functions would not be good (marked in red).

Figure 1. The nature of translational regulation by miRNAs or siRNAs.

The genome independent from the target genes, endogenous siRNAs often come from the target mRNAs. The processing of miRNAs comes from local hairpin formation of the target transcripts but that of siRNAs long bimolecular RNA duplexes. MiRNAs are single stranded RNAs, each 20–24nt long, and they do not encode for proteins. They have been found in all multicellular organisms, from plants to humans; they are abundant, estimated to be 3,000 – 40,000 molecules per cell. Computational and microarray analyses scanning for short, conserved repetitive sequences capable of forming secondary structures showed that genes encoding miRNAs composed of about 1% of the predicted genes in each species; hence, there are about 250 out of 30,000 genes in human genome, 100 in nematode and 80 in Drosophila [22].

MiRNAs are also unusual in their expression patterns. For example, lin-4 mentioned above is developmentally stage specific, so are many others [23]. Yet some are cell type or tissue-specific. For example, MiR-1 is preferentially expressed in mammalian heart [24], MiR-122 in the liver and MiR-124 in mouse brains, [25, 26], MiR-223 in granulocytes and macrophages of mouse bone marrow [27], and MiR-290 to MiR-295 in mouse embryonic stem cells [28]. Thus it appears that each developmental stage, cell type or tissue may have a distinctive MiR expression profile. Added to these unique expression profiles of MiR is the fact that more than 90% of all known MiR target genes encode for transcription factors, which regulate expression levels of many other structural or functioning genes, in plants and animals. Bartel interpreted these unique MiRs as “micromanagers” for gene transcription [17]. While this makes perfect sense, this unique expression profiling of MiR might pose significant concerns and require serious considerations when the siRNA technology is applied therapeutically. For example, what if the stem cell “micromanagers” are introduced through siRNAs and expressed in granulocytes or in livers? This issue would be related to the issues of true specificity of MiR targets, being discussed in the next paragraph.

Gene silencing via RNAi technology is achieved principally via base-pairing complementarity to target mRNA (some even to genomic DNA affecting transcription, which is beyond the scope of this article). Perfect sequence complementarity, as observed in siRNA-mediated gene silencing, results in degradation of the target mRNA (Figure 1, gene A). On the other hand, near perfect or incomplete complementation, as in the case of miRNA-mediated gene silencing, leads to inhibition without RNA degradation [16, 17, 19] (Figure 1, genes B-D). Mutational analyses on the known miRNAs and their target motifs indicated that the first 2–8nt of these miRNAs are often perfectly complementary to sequence motifs at the 3’-UTR involved in translational repression [29], and appear to be highly conserved among many different species [30, 31]. Unlike siRNAs, which usually target the genes from which they originate, miRNAs target many genes, perhaps a few thousand genes for each miRNA [16, 17]. Given that there are about 200–250 different miRNAs, the number of different species of mRNAs that are regulated by translational silencing can easily be in the thousands [22]. Taken together, there appear to be a set of genes to which a particular miRNA target, with a hierarchy of differential base-pairing affinities, as shown in Figure 1; the higher the complementarity in base-pairing, the more effective translational repression will be. Based on the above picture, introduction of a stem cell “micromanager” into a non-stem cell biological environment, as was raised in the last paragraph, may result in “mismanagement”, as would be the case of therapeutic applications using RNAi technology. This issue is hard to address without extensive knowledge on the nature of the set of genes that are target for any particular miRNA. One would not anticipate major problems if all the target genes of a particular miRs fall into the same category in biological functions. Conversely, major problems could appear if the target genes of a particular MiR are involved in various biological functions. This would not be true if there is a particular MiR that is ubiquitously expressed and is not “micromanaging” any specific cell type, tissue or developmental stage. Concerns have been raised regarding the recent observation of activation of a broad spectrum of non-specific siRNA-mediated immune responses in siRNA-transduced cells [32, 33]. These undesirable effects could be related to the concept of a particular “micromanager” being placed in a “wrong work environment”. The search for a non-micromanger MiR, if it exists, would be an important advancement from the standpoint of medical applications.

4. Rna Degradation

4.1. ARE elements

Messenger RNA turnover is a highly regulated process that involves both cis-acting sequence and trans-acting proteins. One of the ways in which mRNA turnover is controlled is through AU-rich motifs in the 3’UTR. These AU-rich elements (ARE) are comprised of a large class of cis-acting 3’UTR sequence that regulate RNA stability. These elements were first identified in the 3’UTR of mouse and human tumor necrosis factor (TNFa) mRNA, and then subsequently identified in other unstable RNAs [34]. This idea that AU-rich elements enhanced mRNA turnover was further supported when the 51 nucleotide ARE of granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) replaced the 3’UTR of the b-actin gene and caused rapid decay of the mRNA [35].

These ARE elements also appear to be highly conserved, more so than the coding regions of these genes. For example, in the c-fos gene the 3’UTR has 80% homology among diverse species (36). AU elements consist of either U-rich stretches of sequence, the pentamer AUUUA, or the nonamer, UUAUUUA(U/A)(U/A), and have been divided into three classes [see review in 36, 37]. Class I ARE control cytoplasmic deadenylation of mRNAs. All parts of the polyA tail are degraded at the same rate, resulting in intermediates that are completely degraded. They consist of 1–2 copies of AUUUA next to a U-rich region and examples of mRNAs include the transcription factors c-fos and c-myc. Class II ARE elements cause asynchronous cytoplasmic deadenylation resulting in degradation of the polyA tail at different rates in different transcripts. They consist of tandem AUUUA repeats and examples include GM-CSF, IL-2, TNFa, and IFNa. Class III ARE degrade mRNA in a similar mechanism as seen in Class I AREs, however, they do not contain an AU element. Class III elements contain U-rich segments and examples include c-jun and renin mRNA [37].

The exact mechanism by which AREs regulate mRNA stability has been unclear. Multiple repeats of the ARE sequence are necessary and both the structure and sequence in this region may be important for function. Evidence for secondary structure arises from RNA folding predictions of the VPR/VEGF ARES. There is 93 % homology between human and rat in forming two stem loops and hairpin region [38]. The similarity of the folding suggests that the structure is important and extremely conserved throughout diverse organisms.

AREs may also rely on other protein components and factors to regulate instability, and in some cases, stability of RNA transcripts. Evidence that ARE binding proteins play a role in regulating degradation has been seen in pathways that are involved in cellular responses to metabolic changes or environmental factors. These trans-acting proteins regulate decay in both gene specific and function specific mechanisms and are expressed differentially in different tissues at different times during development.

4.2. ARE binding proteins

The ARE binding proteins could influence rapid mRNA turnover by either direct recruitment or activation of RNAses, or through indirectly making contact with factors that bind ARE, independent of nucleases. These binding proteins can have either positive or negative effects, and can regulate stability, translation, or subcellular localization. Most of these experiments to identify putative AU-binding proteins have been performed using UV cross-linking and gel-shift assays [37, 38].

Seventeen proteins have been identified that bind to AU-rich elements. These include the heteronuclear ribonucleoproteins [hnRNP A1, hnRNP C [39], and hnRNP D [AUF-1,40] which bind these elements selectively and with different avidity. There are also RNQA binding proteins that display enzymatic activities, such as GAPDH [41] and AUH [42]. HuR proteins have also been identified and include hel-N1, HuC, HuD, and the ubiquitously expressed HuR [43]. Finally, there are other proteins that bind ARE including AU-A, AU-B, AU-C, tristetraprolin (TTP), butyrate response factor-1, KSRP, TIA-1, and TIAR [44].

The mechanism by which these proteins affect mRNA turnover remains unclear. One possibility is that the proteins bind the deadenylase and modulate degradation in this way. An alternative is that the proteins alter interactions for degradation by influencing the local structure providing better access for the ribonuclease. A third possibility is that these proteins recruit the exosome complex directly. Proteins that stabilize the mRNA trascript may do so by not allowing access of the exosome, while destabilizing AU binding proteins may directly recruit the exosome complex, resulting in rapid degradation [45].

4.3. Examples of proteins involved in mRNA turnover

Tristetraprolin (TTP) is a protein containing CCCH tandem zinc finger motifs [46] and has been demonstrated to destabilize class II ARE of TNFa and GM-CSF [39]. The destabilization requires two zinc fingers for binding activity, and TTP mutants that do not bind the GMCSF or TNFa ARE inhibit RNA turnover. TTP exists in many phosphorylated forms and may be a target in many signaling pathways. TTP is phosphorylated by p42 MAPK, p38, and MAPK activated protein kinase. TTP binds to 14–3-3 protein for cytoplasmic localization and has also been associated with the nuclear shuttle protein HuR in T-lymphocytes. The shuttling properties of this protein may contribute to cytoplasmic and nuclear decay of mRNA [47, 48].

K-homology type splicing regulatory protein (KSRP) binds c-fos and TNFa AREs and may contribute to exosome mediated degradation of mRNA [49]. KSRP is a shuttle protein that contains four copies of an RNA binding K homology domain. These domains are important in that mutations in these regions cause disease or differentiation defects [50].

AUF-1 is an AU-binding protein that is present as four isoforms. P42 and p45 are nuclear, while p37 and p40 are cytoplasmic [51]. The protein complex of p37 and p40 are able to destabilize c-myc in vitro. Phosphorylation appears to be involved as p38 inhibition stabilizes ARE through inactivation of AUF-1 [52]. Of these isoforms, in p37, two non-identical recognition motifs have been identified, an octameric RNP-1, and a hexameric RNP-2. Both are essential for the binding activity of AUF-1.

HuR is an AU-binding protein that stabilizes transcripts. It is a member of a family of proteins whose expression is developmentally regulated and tissue specific. HuR is ubiquitiously expressed. HuR is a nuclear/cytoplasmic shuttle protein that is predominantly nuclear. HuR contains RNA recognition motifs that bind RNA and shuttle it from the nucleus to cytoplasm. It may be this shuttling and the associated nuclear and cytpolasmic proteins that determine the stability of the RNA that is bound by HuR [43].

The regulation of these proteins is dependent on conditions and stimuli. In the cases of TTP and HuR, phophorylation by p38 (a mitogen activated protein kinase) could direct mRNA decay. PI-3 kinase and p38 MAPK independently stabilize IL-3 in NIH 3T3 cells. It may be the dynamic equilibrium between stabilization/degradation by TTP and HuR that determine the fate of this transcript. AUF-1 may act in a similar way with HuR. The exosome also plays an important role in degradation of transcripts and may be affected by accessibility and local topology of the 3’UTR ARE and the proteins that are bound [53].

5. Intracellular Localization

5.1. Cell motility and mobility

One way polarized cells establish their asymmetry is to localize mRNA transcripts to specific subcellular localization. RNA subcellular localization has been observed in oocytes and developing embryos of Frogs (Xenopus) and flies (Drosophila) [54–58]. In mammalian system, b-actin is expressed abundantly in all cells and it has many biological functions, including polarity and motility, protein synthesis, and various enzymatic biological processes. In motile chicken embryonic fibroblasts, b-actin mRNA has been shown to be highly expressed at the leading lamellae [59]. Rapid changes in actin polymerization at the leading edge drive extension of the lamellipodia, hence cell movement. Likewise, b-actin protein and mRNA colocalize to the leading lamellae of endothelial cells in response to wounding [60]. A 54-nt segment, called “zip-code” motif, located at the 3’-UTR of b-actin mRNA, is found to be responsible for such subcellular localization; this motif is thought to be distinct from those that mediate RNA stability or translational repression, as treatment of antisense oligonucleotides specific to the zip-code affected delocalization of b-actin mRNA but not RNA stability or suppression of actin synthesis. [61].

This zip code motif is highly conserved in primary sequence within b-actin mRNA from all species analyzed, including those of humans. Unlike the AU-rich sequence motif that affects RNA stability, there is, however, little sequence conservation among localization motifs that are present within the 3’-UTR of different mRNAs. Further studies identified ZBP1 (zip code binding protein) that binds to this zip-code with high affinity [62]. ZBP1 also colocalize with b-actin mRNA at the leading edge during cell movement, suggesting its involvement in binding b-actin mRNA, anchoring the mRNA to this region. To identify various components of the machinery responsible for this cell movement caused by polymerization of b-actin protein, similar co-localization studies of suspected molecules have been conducted. Elongation factor 1a(EF1a), involved in protein synthesis, and F-actin, a component of microtubule, have been shown to be involved in the binding and co-localization of b-actin mRNA at leading lamellae [63]. These studies suggest the involvement of an active protein translation apparatus and cytoskeleton in anchoring b-actin mRNA to the protrusion in crawling cells.

While the 54-nt zip code motif is clearly involved in its localization of b-actin mRNA to the leading edge of embryonic fibroblast, deletion of part or whole zip code reduces but does not eliminate its targeted localization activity, suggesting the involvement of additional motif other than the zip code motif [61]. Indeed, there is a homologous 43-nt zip code like element that also contributes to the full activity, albeit its activity is significantly less than that of the zip code. These results also suggest the presence of a number of genetic elements, within or outside the 3’-UTR, that are interacting with one another during localization of the target mRNA. The consequence of these interactions could be localized synthesis of proteins with optimal and effective execution of a function required at that location, such as the polymerization of b-actin being synthesized at leading edge of motile fibroblasts and myocytes, and growth cone of neuronal cells (see below). Consistent with this idea is that extremely intriguing observations are those reported by Elizabeth Gavis, who showed that in Drosophila oocytes, about 96% nanos mRNAs are unlocalized and distributed thoroughout the cytoplasm of the oocytes, and only the remaining portion of the mRNAs that are localized in the posterior end of the oocytes, via a 90-nt localization motif, are translationally active and functioning [64].

Not only more than one zip code motif can be involved in intracellular localization, more than one motif-binding protein can also be involved, each with different binding affinity to the target sequence. Recent work done by Singer and co-workers showed that as many as 5 proteins bind to the 54-nt zip code [65, 66]. ZBP1 binds with high affinity; mutational analyses showed that the protein contains domains responsible for granule formation, microtubule association, and of course, b-actin mRNA binding. Another protein is ZBP2, also an hnRNP protein like ZBP1, and has a human homologue. Unlike ZBP1, which contains a nuclear export signal and is predominantly cytoplasmic, ZBP2 contains a 47aa nuclear localization signal and is predominantly nuclear but it does shuttle in and out of the nucleus. Therefore mRNA localization process could begin in the nucleus: ZBP2 brings the b-actin mRNA out of the nucleus, and then ZBP1 takes over and escort the mRNA to the leading lamellae, through the microtubule assembly, where translation would begin. After protein synthesis, polymerization of b-actin would drive lamillipodia directionally and the cells move forward.

5.2. Neural transmission

Synaptic plasticity is a complex biological phenomenon that is associated with long-term potentiation (LTP), hence long-term memory storage in the brain. The strength of synapses appears to change in response to activation of neurotransmitter receptors present on cell surfaces of dendrites, and modulation of synaptic strength has been shown to be dependent on de novo protein synthesis, or localized protein synthesis in dendrites or synaptic sites as a function of synaptic activity [67–69]. Therefore, local protein synthesis within dendrites associated with mRNA intracellular localization represents an extremely interesting mechanism that can explain this activity dependent synaptic plasticity. Evidence supporting this model is quite clear.

In neurons, the majority of mRNAs are located in the cell body; however, a number of them are specifically located to the dendrites. Using high resolution in situ hybridization and image processing methods, Singer, Bassell and associates [70] showed that while b-actin mRNA and protein are distributed uniformly throughout the cytoplasm, b-actin mRNA and protein are localized in dendrites and growth cones of neurons. Likewise, the Arc mRNA and protein are also found to be localized to the synapse only in response to synaptic activation [71, 72].

The zip code motif has been shown to be responsible for b-actin mRNA localization in dendrites [65, 70, 73] Transport of specific mRNAs to dendrites is achieved through microtubules in the form of granules that apparently contain an active transport unit and translational machinery. The association of the zip code binding proteins, including ZBP1, with granules on microtubules has been shown to be dynamically dependent on KCl-induced neural depolarization and there is a rapid efflux of ZBP1 from the cell body to the dendrites [74]. This activity dependent trafficking of ZBP1 suggests selective targeting of b-actin mRNA to postsynaptic sites within dendrites in response to synaptic activity.

Localized mRNA and translational activation of protein kinases are also found to be present in dendrites or synaptic sites. One example is CaMKIIa (Calcium/ calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II alpha), whose induction and maintenance in LTP is known, and it has been implicated in dendritic mRNA transport. By in situ hybridization, CaMKIIa mRNA is localized in dendrites, and using GFP (green fluorescent protein) fusion constructs in the studies for visualization, CaMKIIa 3’-UTR has been shown to be responsible for such localization [75, 76]. The CaMKIIa mRNA is also found in microtubule granules, and synaptic activity, reflected by the degree of neuronal depolarization, increase the number of granules in the dendrites [76]. These data are consistent with in vivo observations. Mice lacking the CaMKIIa 3’-UTR exhibit disruption of CaMKIIa mRNA localization, reduced expression of this protein in dendrites, diminishing long-term potentiation and impairments of several forms of associative learning, suggesting that localized protein synthesis contributes to synaptic plasticity [77]. Full characterization of this localization motif and trans-acting factors binding to it has yet to be defined.

Another example in which localized translational activation is linked to synaptic sties is PKMz (protein kinase M zeta). PKMz is an atypical protein kinase C and is known to be involved in synaptic activity-dependent LTP and memory storage in the brain. Its mRNA has been shown to be rapidly transported and localized to synaptodendritic neuronal domain after induction [78]. Two localization motifs, called dendritic targeting elements (DTE), have been identified. One is at the 5’-UTR (DTE1) and the other is at the 3’-UTR (DTE2). DTE1 appears to direct somato-dendritic export of the mRNA, whereas DTE2 appears to deliver the mRNA to the dendrites.

6. The Uniqueness of Ran Gtpase

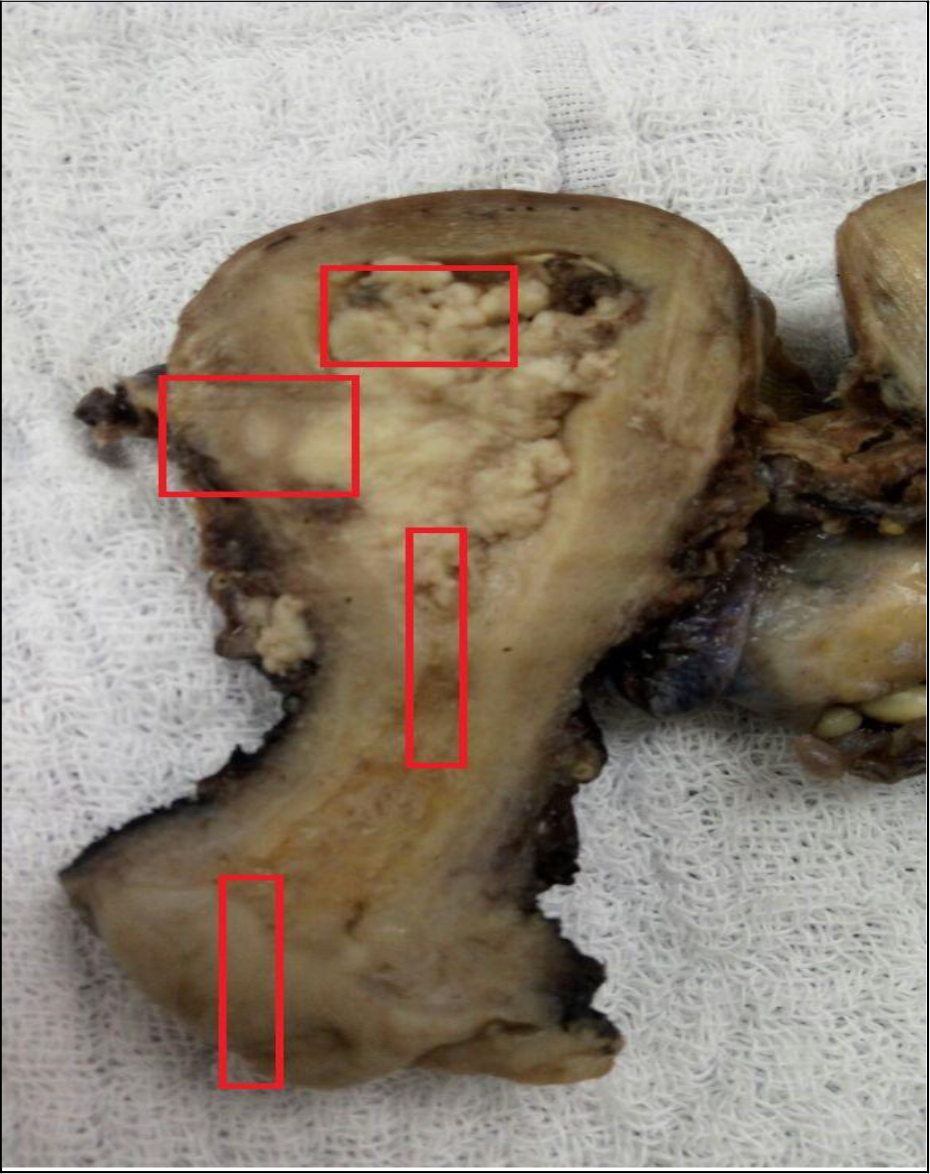

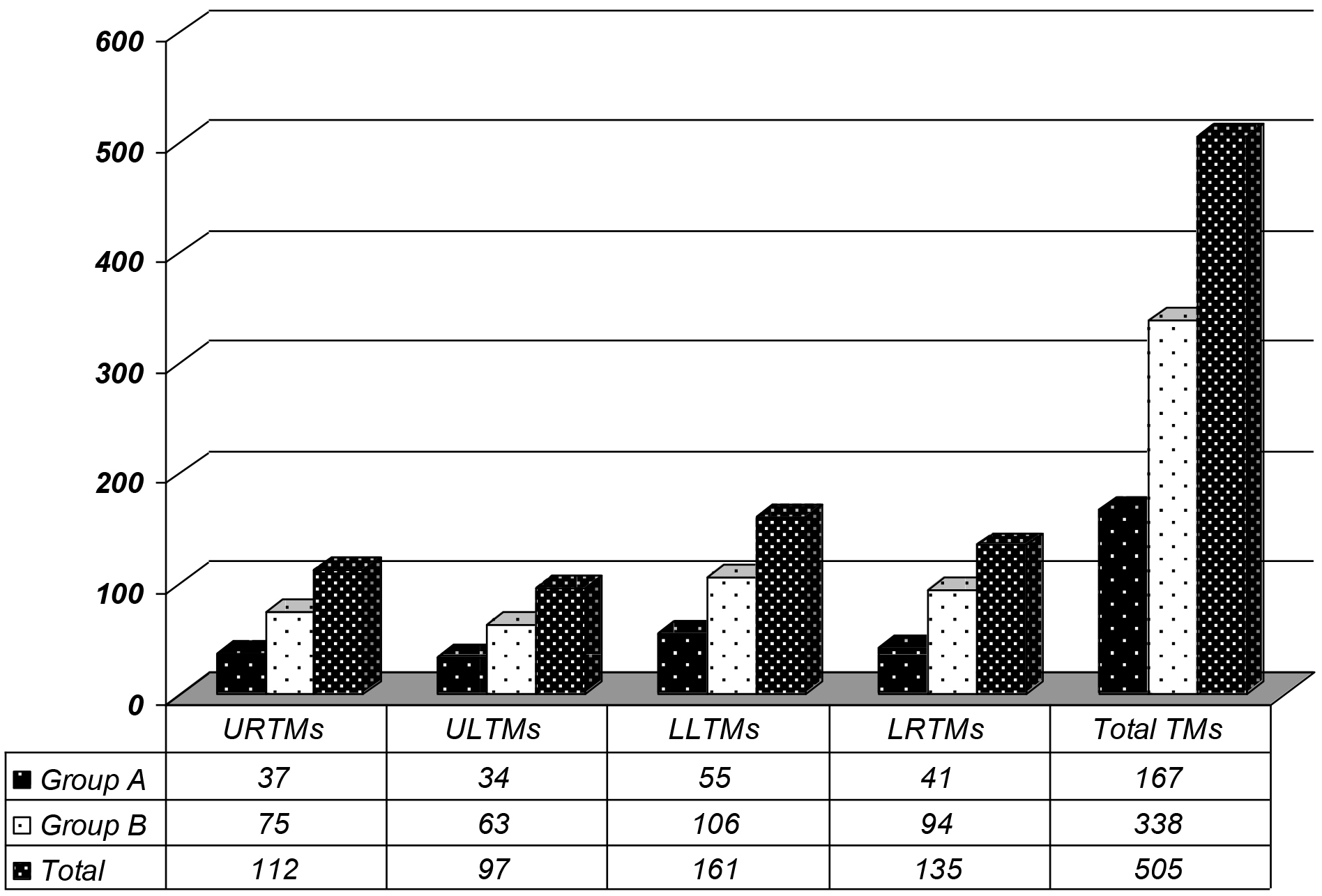

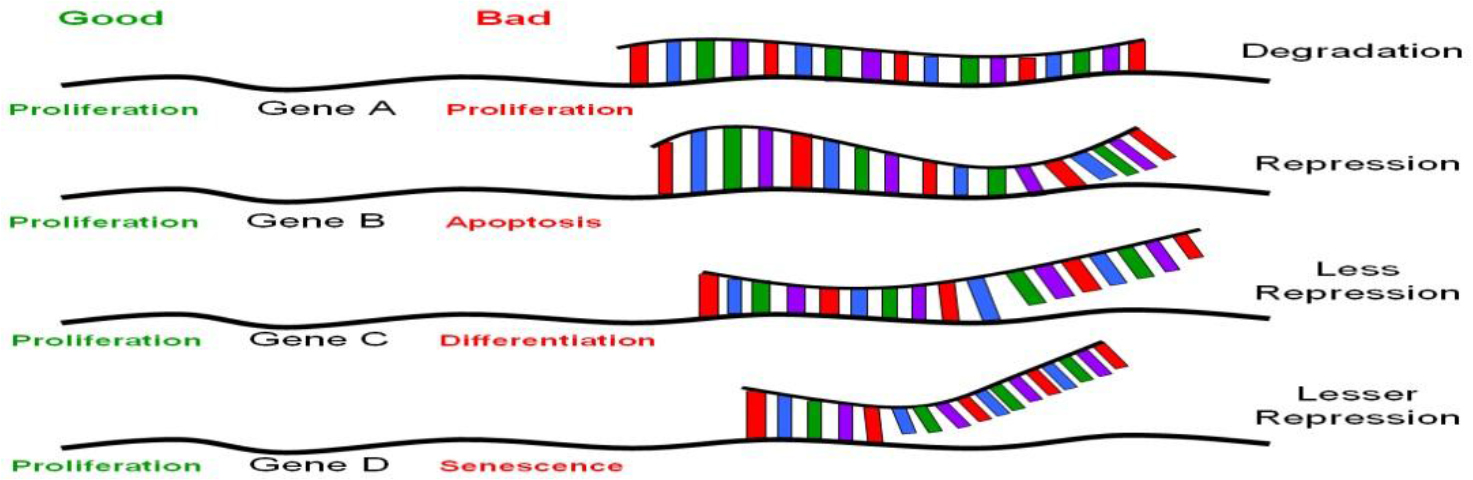

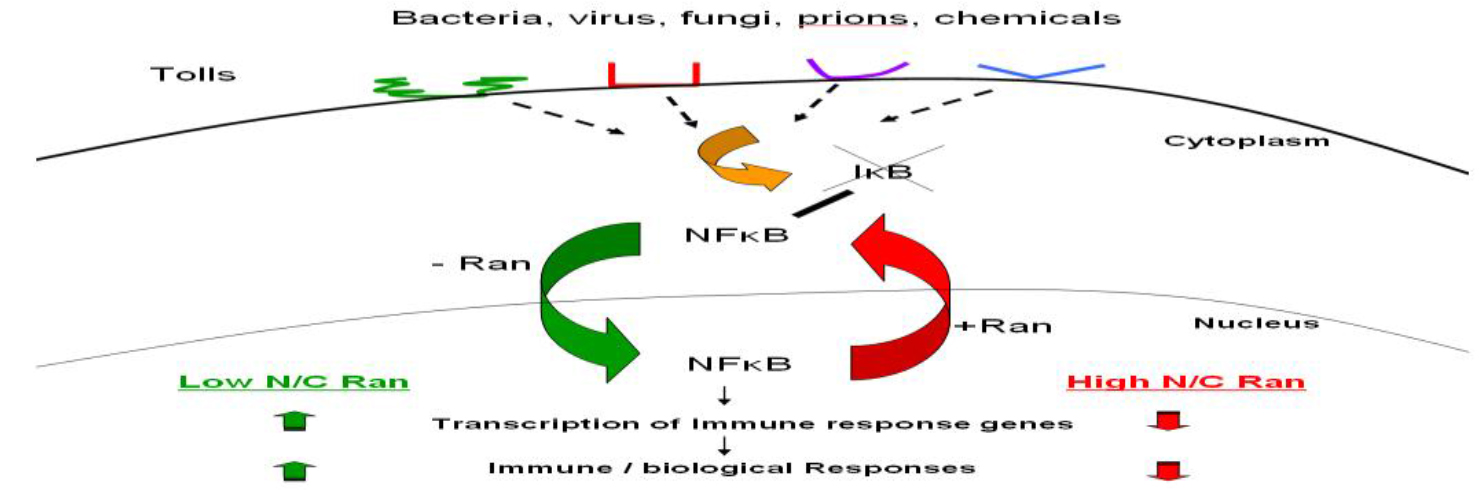

Ran GTPase is a unique member of a large family of G-proteins. It is expressed abundantly in all nucleated mammalian cells, and at steady state, most but not all of them reside in the nucleus. Ran GTPase is also (Figure 2) Various microbial pathogens invade cells using different Toll-like receptors (TLR) or other receptors on the cell surface, initiating one or more signaling transduction pathways many of which act through biochemical modification of NF-κB inhibitor IκB. This results in the release and activation of NF-κB, which translocates into the nucleus without the need to associate with Ran, binds to DNA sequence of immune response genes and activates transcription of these genes that encode for pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNFa, IL-1 and IL-6. More nuclear Ran or higher N/C ratio of Ran, as in RanC/d-transduced cells, would enhance nuclear export of NF-κB via the Ran/Exp1 complex, reducing NF-κB transcriptional activation, hence down-modulating immune response. Conversely, more cytoplasmic Ran, hence lower N/C, as in RanT/n-transduced cells, would discourage nuclear export of NF-κB, hence no reduction of NF-κB transcriptional activity in the nucleus. More cytoplasmic Ran would also directly stimulate signal transduction pathways involved in immune response through binding to adaptor molecules such as RanBPM (see text).

Figure 2. Ran-mediated immune modulation of host immune response.

Intimately involved in several very fundamental processes in cell cycle progression [5–7]. At interphase, it is a key molecule involved in the transport of a majority of all macromolecules in and out of the nuclear membrane. During mitosis, Ran is required for mitotic microtubule spindle formation and nuclear envelope assembly. It also prevents DNA re-replication during S phase [79]. Obviously then, it is amazing how Ran gets itself involved in all these important molecular events and how all these crucial regulatory events translate to biological phenomena. At the cellular and organismic levels in mammalian system, the clue comes from the identification of genetic changes at the 3’-UTR of Ran, producing corresponding and predictable changes in Ran’s RNA structure, in Ran’s nuclear/ cytoplasmic ratio, and in modulating Ran-mediated host immune response [8–10].

6.1. Single nucleotide change in 3’-UTR of Ran leading to changes in protein and RNA localization and other biological changes

By functional cDNA expression cloning, followed up with forward genetic analyses, we identified two Ran alleles, RanC/d and RanT/n, that differ from each other only by a single nucleotide, located at the 3’-UTR [8–12, 80–82]. This single base change leads to striking changes in RNA structure (12). As a result of this RNA structural change, we demonstrated difference in protein and RNA intracellular localization. Expression of RanC/d leads to a rapid nuclear localization and down-modulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine production, correlated with protection of mice from endotoxin-induced shock. Conversely, expression of the other allele, RanT/n, results in a predominant cytoplasmic localization of Ran proteins and an up-regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine production, correlated with increase susceptibility to endotoxic shock. Subsequent studies provide more detailed biological changes in mechanistic terms as a result of this single nucleotide change and these details are strengthened by several other findings in the literature.

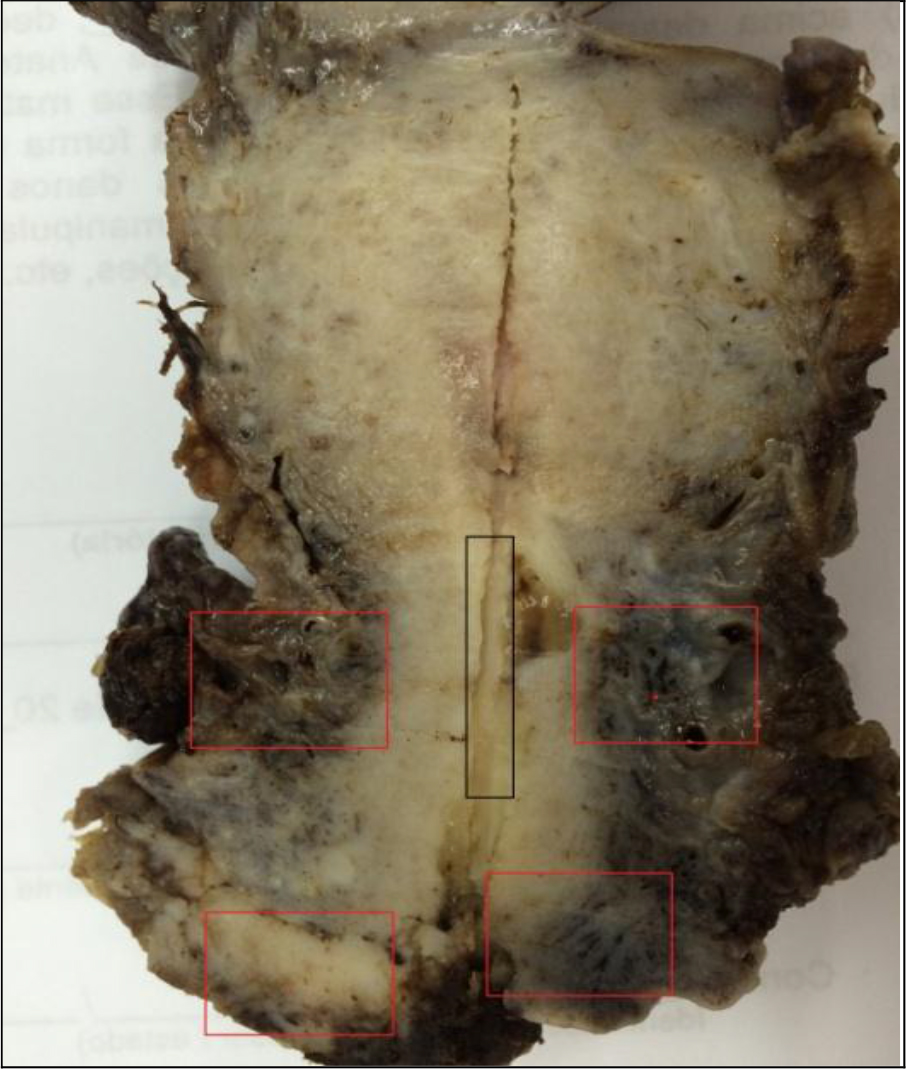

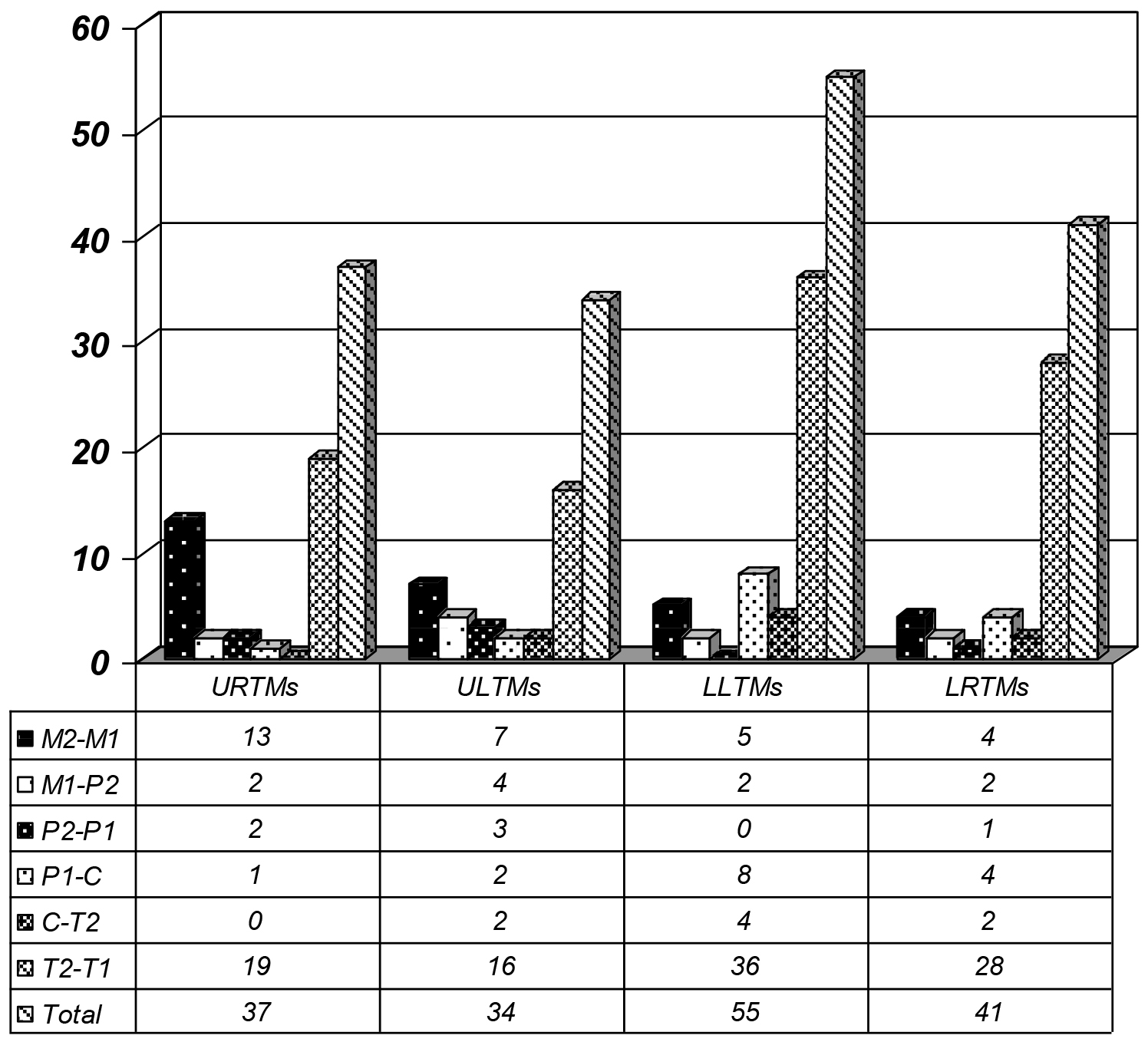

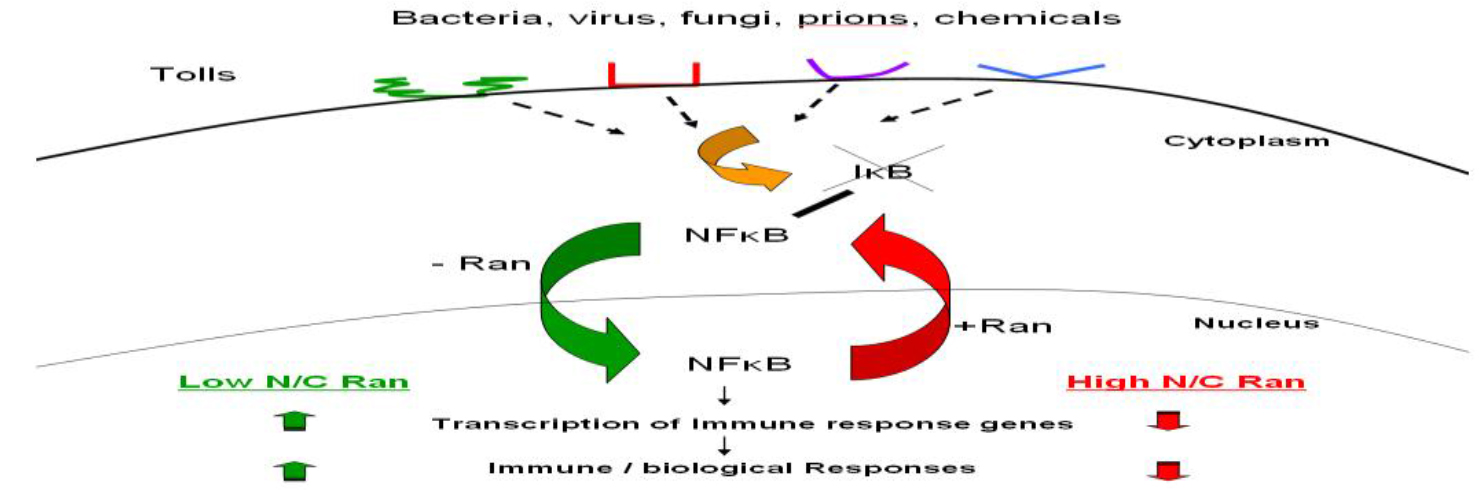

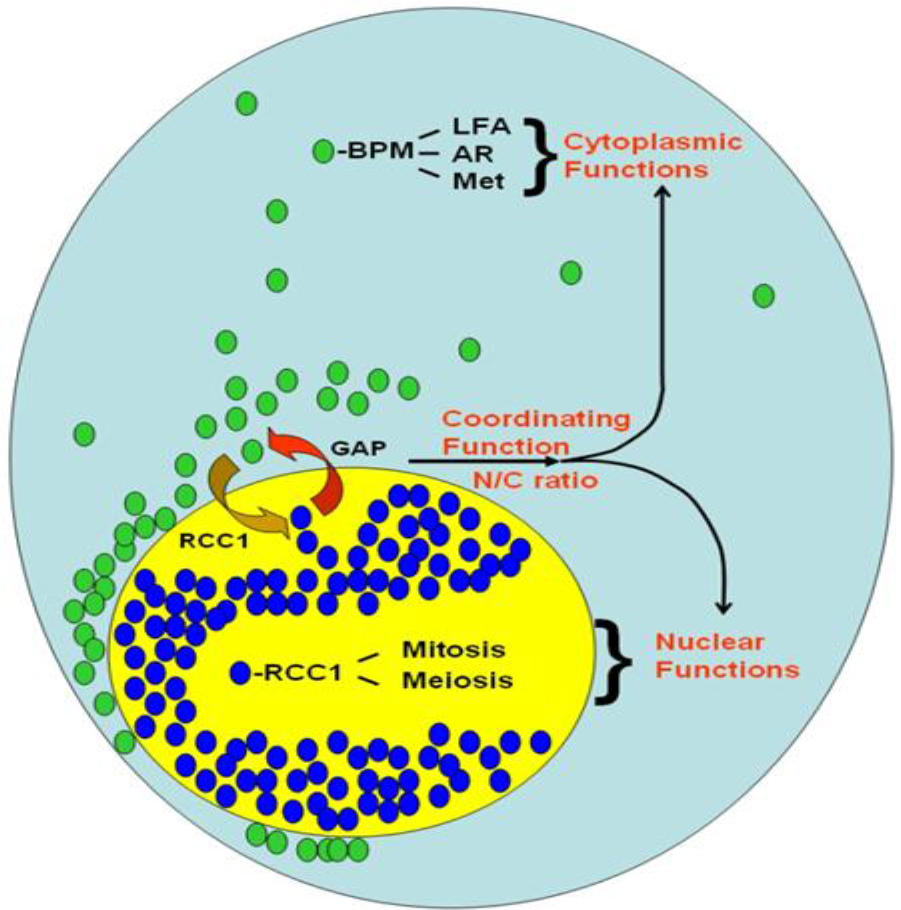

First, this single nucleotide change in Ran 3’-UTR correlates with changes in proteins and Ran RNA intracellular localization and is entirely consistent with the existence of localization sequence motif, the majority of which are located within the 3’-UTRs [54–56, 58]. Second, this difference in Ran intracellular localization results in changes in Ran’s nuclear/cytoplasmic (N/C) ratio Figure 2. In RanC/d-transduced cells, more nuclear Ran (Figure 3) The main principle of this model is the same as we predicted before – cytoplasmic Ran can initiate signal transduction events independent of nuclear Ran, by association with other signaling molecules in the cytoplasm [M and B in Figure 3 of [82]. Green ovals are RanGDP, blue ovals are RanGTP, BPM = Ran-BPM, GAP = RanGAP, LFA = LFA-1, AR = androgen receptor, Met = Met receptor for hepatic growth factor, RCC1 = Regulator of chromosome condensation, N/C ratio = nuclear/ cytoplasmic ratio. At steady state, most Ran GTPases reside in the nucleus, and some are located outside the nucleus by virtue of sumoylation of Ran-GAP that hydrolyses RanGTPs as soon as they are exported from the nucleus. Most cytoplasmic Ran there cycle back into the nucleus, some remain in the cytoplasm. Complex formation of cytoplasmic Ran, BPM and other molecules initiates signaling for cell motility and migration, proliferation, cell adhesion, modulation of immune response and other cytoplasmic functions. Complex formation of nuclear Ran and RCC1, or perhaps other molecules, would encourage nuclear events such as mitotic spindle formation, nuclear envelope assembly or DNA re-replication. These two sets of events could be opposing to each other; the final outcome is dictated by the absolute amounts of Ran in each compartment, as well as their relative amount, which is the N/C ratio of Ran.

Figure 3. A model of Ran GTPase-mediated biological response.

Increases the N/C ratio; more nuclear Ran also increases the export of NF-κB from the nucleus to the cytoplasm because nuclear export of NF-κB is completely Ran dependent [8, 83–86]. Increase nuclear export of NF-κB results in decrease in its transcriptional activation of immune response genes, including those encoding for pro-inflammatory cytokines (manuscript submitted). Conversely, in RanT/n-transduced cells, more cytoplasmic Ran decreases the N/C ratio, resulting in reduced nuclear export of NF-κB, enhanced transcriptional activity of NF-κB, increased immune response and sensitivity to endotoxic shock. Third, the observed biological changes did not correlate perfectly with the N/C ratio of Ran, over-expression of either Ran allele did not result in overt growth damage (manuscript in preparation), yet in cells or mice transduced with RanT/n cDNA, increased immunological sensitivity as a result of RanT/n expression is apparent. More than likely, therefore, cytoplasmic Ran, in the form of RanGDP, possesses a function independent of the N/C ratio and that this function enhances the biological outcome induced by the change of N/C ratio. Indeed, cytoplasmic Ran has been shown to bind to Ran-BPM [87,88], an adaptor molecule that binds between Ran and a number of molecules involved in modulation of host immune response, cell migration, cell fate and wound healing; they include androgen receptor [89], LAF-1 [90], Met kinase receptor for hepatic growth factor [91,92], and others.

We propose that this interdependence between the absolute amount of Ran in each cellular compartment and their relative amount, i.e. N/C ratio, is the key to Ran’s role in the regulation of many fundamental aspects of mammalian cell growth and differentiation, a model we previously proposed [82], and is now more refined in (Figure 3). Because of this interdependent relationship, the interactions of Ran with other molecules must be characteristically dynamic. The abundance and ubiquity of Ran in all cells attest to the validity of this concept, as the endogenous Ran would be acting as a very strong buffer, biochemically speaking. Extension of this principle points to the immense potential of applying Ran as a genetic therapeutic vaccine in a variety of clinical applications in which the key fundamental molecular defect is Ran-dependent, be it a change in Ran nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio, or in RanGTP/GDP ratio. This clinical potential is further support by our recent data showing that over-expression of either RanT/n or RanC/d allele results in similar transient growth alterations but is non-toxic (manuscript in preparation).

6.2. The issue of C versus T

Sequence alignments have been performed in the past indicating that Ran GTPAse protein is highly conserved [9, 93–95]. Alignment of 3’-UTR Ran sequences from various species reveal the presence of a C residual at position 870 and the corresponding position for sequences of other species. What then is the origin of the RanT/n allele? RanT/n was first isolated and cloned from a cDNA library made from mRNAs of endotoxin-induced splenic B cells of C3H/HeOuJ, an LPS (lipopolysaccharide) responsive inbred mouse strain [9]. Identification of such cDNA was accomplished via functional conversion of B cells of C3H/HeJ, an LPS resistant mouse strain, from a state of hypo-responsiveness to a state of responsiveness upon LPS stimulation. Did RanT/n come from the genome of C3H/HeOuJ mice, or not? (Table 1).

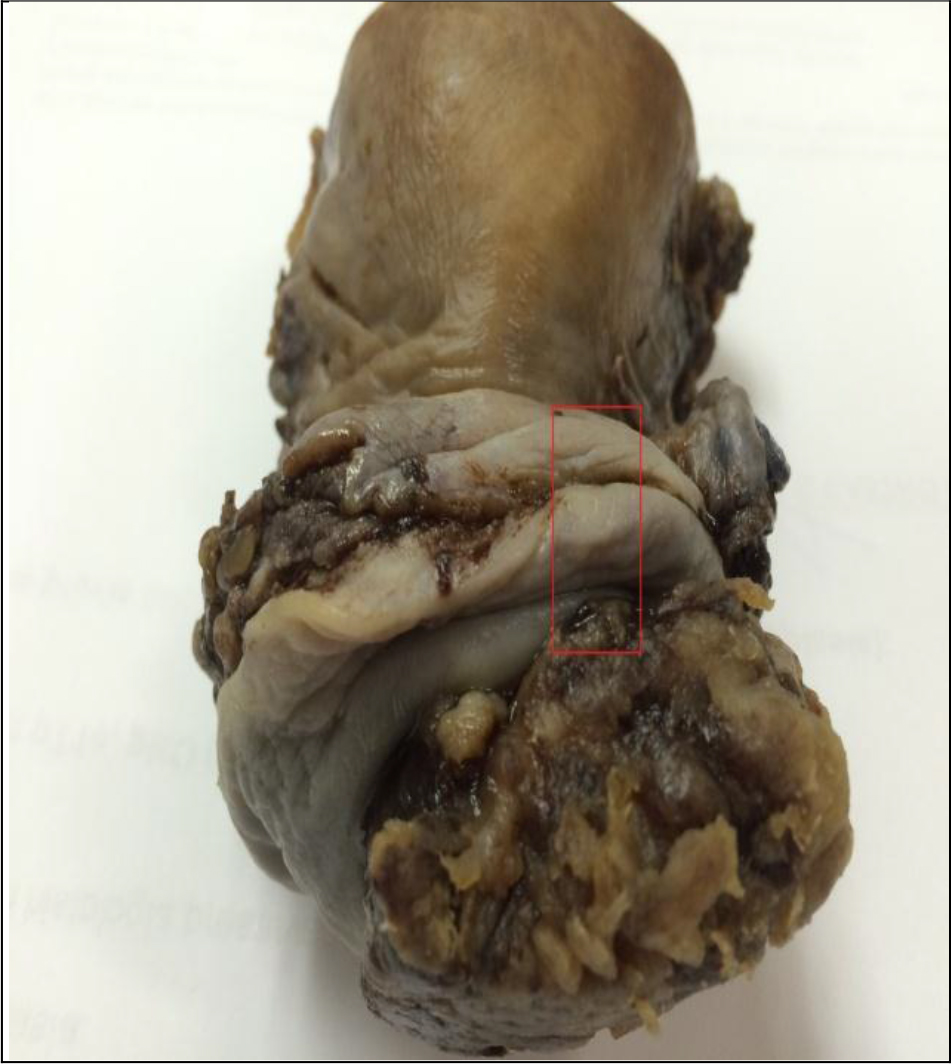

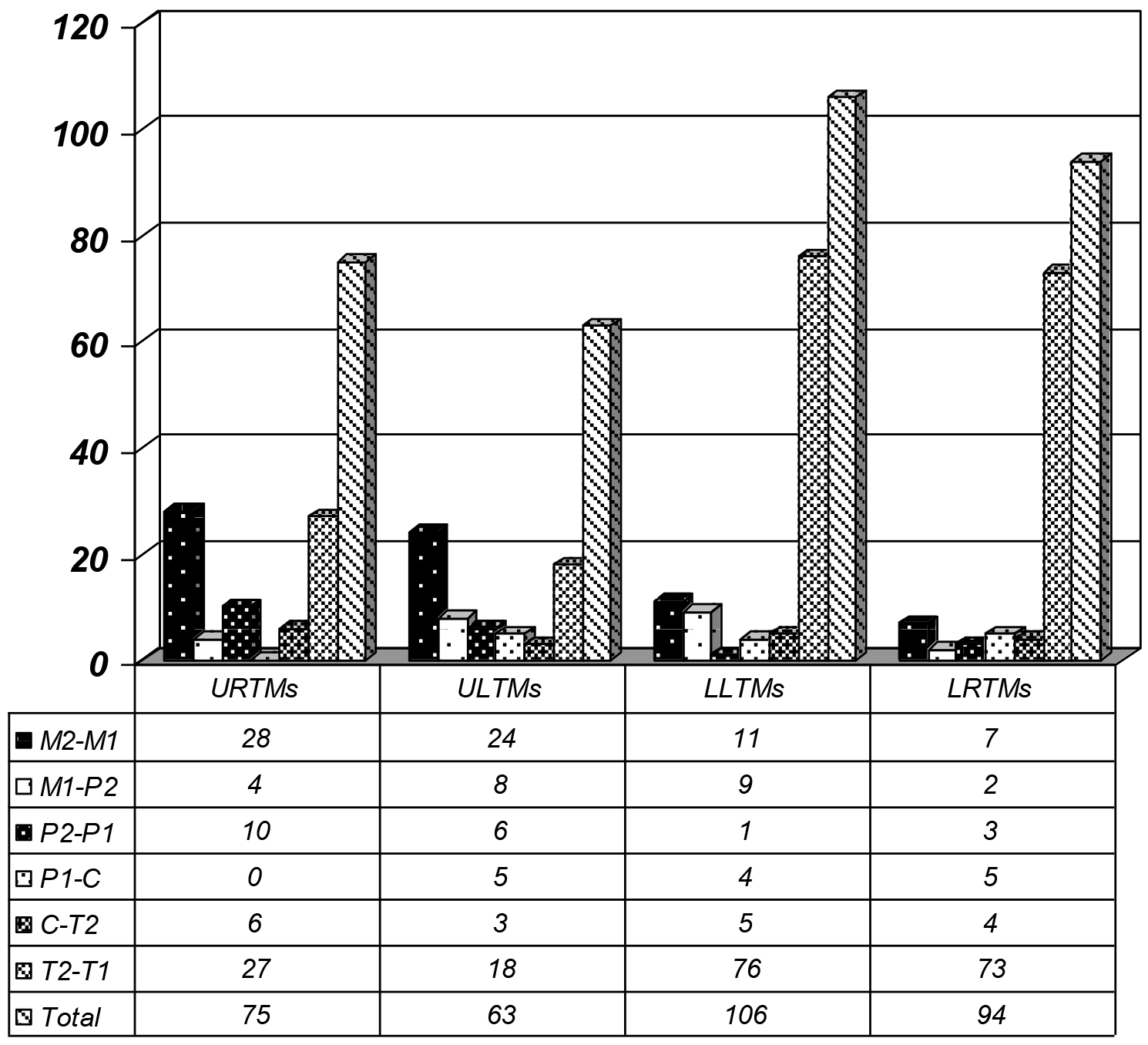

Nucleotide position indicates the nucleotide regions in the 3’UTR that were mutagenized with single base pair substitutions. These regions are also indicated in the (figure 4). Significant structural changes were scored arbitrarily as being structure predictions determined by the M-fold program that disrupted the original structure of the region (i.e. alteration of the stem loop and bulge regions). Nucleotide clustering indicates the regions or specific nucleotides that were most apparent in altering the predicted secondary structure. This table is not intended to give a complete analysis of the 3’UTR, but rather a mean for modeling where single base changes may affect local secondary structure. The numbers in parentheses indicate the number of structures found in that particular region.

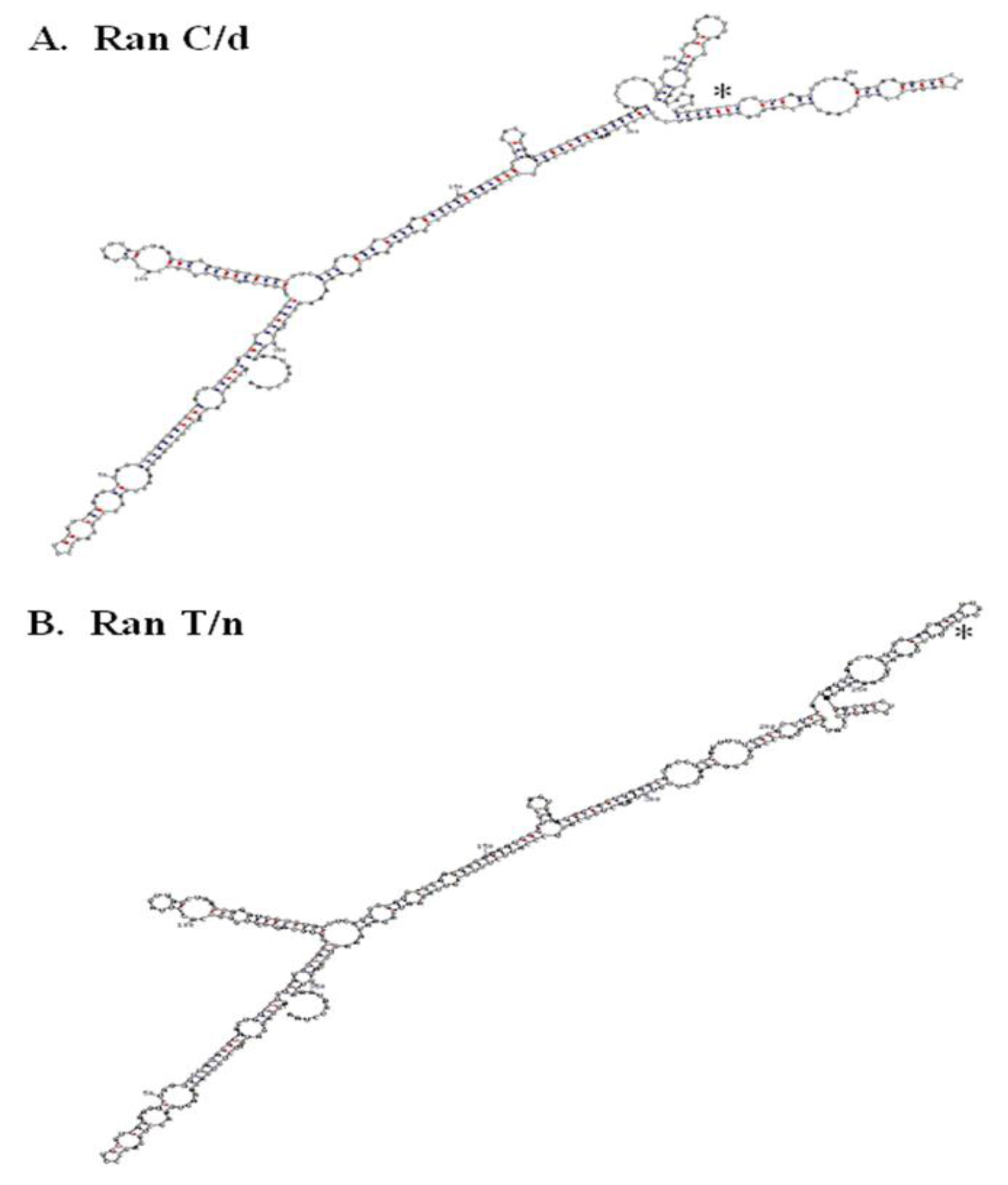

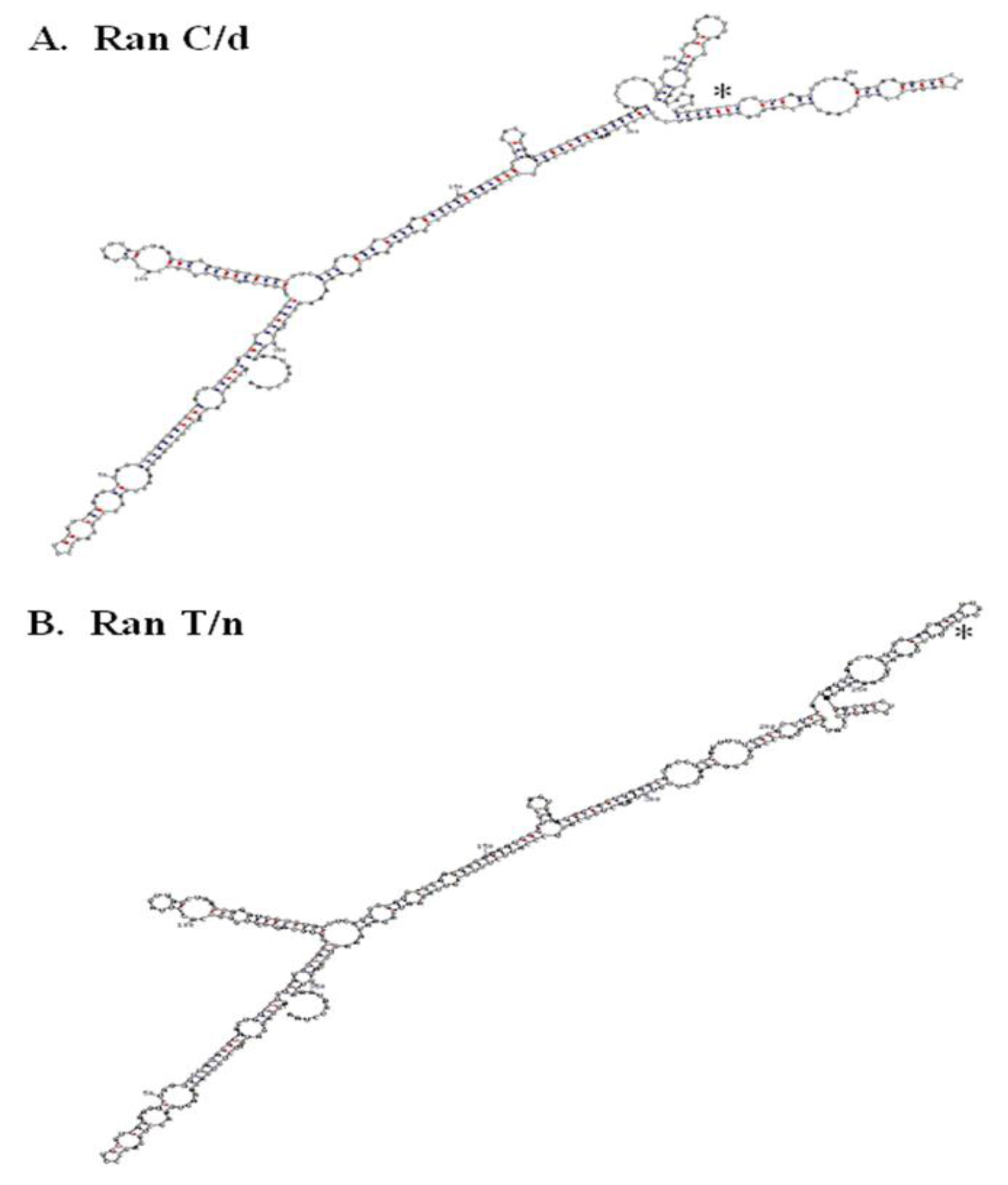

Figure 4. RNA secondary structure of RanC/d and RanT/n 3’-UTR. A.

Table 1. Summary of single base substitutions influencing change in predicted RNA secondary structures of mouse and human Ran 3’UTR.

|

Nucleotide Position (Mutagensis Regions)

|

Significant Structural Changes

|

Nucleotide Clustering

|

|

Mouse

|

|

767–807

|

5

|

767–807 (1)

|

|

787–805 (4)

|

|

832–867

|

13

|

832–844 (8)

|

|

859–867 (5)

|

|

Human

|

|

756–775

|

2

|

765, 771

|

|

825–925

|

20

|

887, 899, 902, 905,

|

|

908, 913–925, 993

|

The above alignment analysis would have provided a very clear answer had Ran gene existed in the mouse genome in single copy. This is obviously not the case. Blasting our Ran sequence deposited in GenBank (accession number AF159256) against the mouse genome showed that there are as many as 7 Ran isoform genes, each is located on a different chromosome. Existence of at least 7 Ran isoform genes was reported by D’Eutaschio, Rush and colleagues at NYU some years ago [93–95]. Among the 7 isoform genes, 4 sequences contain the “C” residue at position 870, one has a “G”, and two do not have sufficient information. Strictly speaking, therefore, the origin of RanT/n could not be ascertained one way or another until all Ran isoform sequences in the mouse genome have been clarified. Regardless of its origin, RanT/n was identified using functional cDNA expression cloning, where RanT/n expression in B cells from LPS-resistant C3H/HeJ mice restored their LPS responsiveness [9].

6.3. More sequence analysis predicting RNA structure

The single point mutation in Ran’s 3’-UTR studies suggest the presence of zip code motif to which specific proteins bind and escort the mRNA to specific intracellular locations. More RNA analysis will be helpful along this direction. Folding the whole 3’UTR of both ran alleles (870C and 870T) using the M-fold program and default parameters [96, 97] suggest that a single nucleotide change may change the folding in the local region (Figure 4). Previous folding using the GCG Squiggles program also suggests that there is a change in the secondary structure [12]. Such prediction of striking RNA structural difference between RanT/n and RanC/d was confirmed by digestion of in vitro transcribed RNAs from T/n and C/d templates with RNase T1, an RNA endonuclease that cleaves single-stranded RNA but not double stranded RNA portions preserved by stem-loops or hairpin structures [12].

Additional RNA secondary structures of Ran 3’UTRs were also generated by mutating, base by base, approximately 100 nucleotides 5’of the 870 position in both mouse and human Ran. Single nucleotide substitutions were inserted into the sequence and folded using the M-fold server [97]. The data from these analyses suggest that the region around 870 is very susceptible to single nucleotide changes in both human and mouse Ran mRNA (Table 1). Phylogenetic comparison of 3’UTR sequences from more organisms would help in identifying consensus motifs and to generate a consensus secondary structure. As reviewed earlier, since “RNA localization element” within the 3’-UTRs is not well conserved and multiple elements may exist in orchestrating localization of Ran to the nucleus periphery, systematic site-directed mutagenesis would aid in the identification of this Ran PNLE – “peri-nuclear localization element”.

6.4. Conserved regulatory element in 3’UTRs of “family member”

Conservation in the 3’UTR has also been observed in another ras family member, Rab1a. It is a regulatory protein necessary for the transport of vesicles from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi apparatus. Sequence analysis of the 3’UTR in 27 different species yielded a 92% similarity between the most distant species (man and turtle), and 95% or greater between more closely related organisms such as mammals [98]. However, this sequence is not homologous to other Rab genes or Ras family members. This observation, along with the high sequence conservation of the 3’UTR of Rab1a, suggests that it has a specific function for location and/or stability of its RNA.

Alignment of the 3’UTR of Ran to other Ras family members does not yield a significant amount of homology (not shown). The Ran 3’UTR aligns best (~50% similar) to human n-Ras 3’UTR sequence as described by Hall & Brown [99]. This also suggests that the 3’UTR has a function specific for Ran mRNA localization. This lack of alignment does not preclude any undefined elements that may be present in the Ras family members that are present in their respective 3’UTR elements. This information will be used to identify potential motifs and tested for changes in localization of mRNA.

6.5. Ran 3’UTR has it all

The 3’-UTR has been thought of as a repository of many post-transcriptional regulators. Indeed, when the 3’-UTR of Ran was blasted against the UTR database, it provided two interesting observations. Plant and mouse Ran 3’-UTR contained an IRES element (internal ribosome entry site) whose functions is to allow independent translation of downstream sequences from this point on. Its role in Ran biology is presently unknown. In addition to the presence of IRES in the 3’- (Figure 4) A. RanC/d, B, RanT/n. The T/C change at position 870 in both structures is indicated with an asterisk. RNA structure was determined using the M-fold program with default parameters. C-G base pairing is indicated with red dots, while U-A base pairing is indicated with blue dots.

UTR region, mouse, human and songbird Ran 3’-UTRs also contain K box consensus sequences, TGTGAT. K boxes are highly conserved and ubiquitous, often found in 3’-UTR regions, and in genes affecting cell growth and development. It was initially found in the 3’-UTR of genes that regulate Notch receptors, which have been shown to play important roles in the development of neural and hematopoietic system. Genetic analyses in Drosophila show that a sequence motif negatively regulates translation of the mRNA in which K box resides, and deletion of this motif results in a gain of function [100,101]. Therefore, K box appears to function through translational repression. The significance of K box in the context of Ran biology is presently unknown.

Ran’s 3’-UTR therefore clearly has many post-transcriptional regulatory elements. Given that Ran GTPase is abundantly expressed and is expressed ubiquitously, the functions of these elements may operate in a coordinated yet flexible fashion to accommodate Ran’s diverse biological roles. Research emphasis on Ran’s 3’-UTR will certainly uncover important and fundamental principles illuminating its roles in cell cycle progression, nucleocytoplasmic transport, DNA re-replication, signal transduction, and Ran-mediated immune responses. Extension of these principles to clinical medicine will be highly beneficial. One example is our discovery of mutational changes within Ran’s 3’-UTR, resulting in predictable modulated host immune response.

7. Conclusion

The discovery of miRNAs and its renewed intense studies has revealed new roles of small RNAs in regulating cell growth and development. The “micromanagers” of miRNAs in specific tissues or cells during a particular stage of development attest to their important roles in many aspects of biology. Understanding of the significance of these biological regulations and how they work have been greatly facilitated by RNAi technology. Therapeutic applications of this technology, however, require more thorough understanding regarding the nature and the specificity of target genes, especially with the knowledge that 2–8nt of any particular miRNA, and therefore, very possibly, any particular siRNA, can have any where in the genome sequence complementation with recognition motifs of the intended target genes.

The 3’-UTR of Ran GTPase contains regulatory motifs involved in translational repression, RNA degradation and RNA intracellular localization. This unique feature emphasizes the importance of post-transcriptional regulation of Ran GTPase. This unique feature is consistent with its many important roles in many aspects of cell cycle progression, nucleocytoplasmic transport and immune response functions, but has apparent contradiction with its abundant and ubiquitous expression, which is more in line with functions of housekeeping proteins. Further over-expression appears to exert only a temporary growth alteration effects (manuscript in preparation). Mechanisms therefore must exist in adjusting not only its absolute levels within the cells through proteolytic degradation, but also its relative amount in each cellular compartment, reflected by either the nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio or the Ran GTP/GDP ratio. On this basis, the discovery of genetic mutants at its 3’-UTR capable of altering both the absolute and relative amounts of Ran, with expected corresponding and predictable functional and biological changes at the molecular, cellular and organismic levels, is invaluable. Such value has already been supported by the demonstration that RanC/d expression can down-modulate host immune response and confer resistance to septic shock, and that RanT/n expression has opposite effects. More such genetic studies in Ran will reveal more of its majestic beauty and its immense clinical applications including but not limited to cancer, AIDS, cardiovascular disorders, infectious diseases, neurologic, metabolic and genetic disorders.

8. Acknowledgement

Work done on Ran GTPase in our laboratory has been supported by NIH RO1 grants from NCI and NIAID.

References

- Fire A, S Xu, MK Montgomery, SA Kostas, SE Driver, et al. (1998) Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 391: 806–811.

- Napoli C, C Lemieux, R Jorgensen (1990) Introduction of a chimeric chalcone synthase gene into Petunia results in reversible co-Suppression of homologous genes in trans. Plant Cell 2: 279–289.

- van der Krol AR, Mur LA, Beld M, Mol JN, Stuitje AR (1990) Flavonoid genes in petunia: addition of a limited number of gene copies may lead to a suppression of gene expression. Plant Cell 2: 291–299. [crossref]

- Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V (1993) The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 75: 843–854. [crossref]

- Dasso M (2001) Running on Ran: nuclear transport and the mitotic spindle. Cell 104: 321–324. [crossref]

- Hetzer M, O. J. Gruss, IW Mattaj (2002) The Ran GTPase as a marker of chromosome position in spindle formation and nuclear envelope assembly. Nat Cell Biol 4: E177–184.

- Weis K (2003) Regulating access to the genome: nucleocytoplasmic transport throughout the cell cycle. Cell 112: 441–451.

- Wong PMC, SW Chung (2003) A functional connection between RanGTP, NF-?B and septic shock. J Biomed Sci 10: 468–474.

- Kang AD, PMC Wong, H Chen, R Castagna, SW Chung (1996) Restoration of lipopolysaccharide-mediated B-cell response after expression of a cDNA encoding a GTP-binding protein. Infect Immun 64: 4612–4617.

- Wong PMC, A Kang, H Chen, Q Yuan, P Fan, et al. (1999) Lpsd/Ran of endotoxin-resistant C3H/HeJ mice is defective in mediating lipopolysaccharide endotoxin responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 11543–11548.

- Yuan Q, F Zhao, SW Chung, P Fan, BM Sultzer, et al. (2000) Dominant negative down-regulation of endotoxin-induced tumor necrosis factor alpha production by Lpsd/Ran. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 2852–2857.

- Wong PMC, Q Yuan, H Chen, BM Sultzer, SW Chung (2001) A single point mutation at the 3’-untranslated region of Ran mRNA leads to profound changes in lipopolysaccharide endotoxin-mediated responses. J Biol Chem 276: 33129–33138.

- Ostareck DH, A Ostareck-Lederer, M Wilm, BJ Thiele, M Mann, et al. (1997) mRNA silencing in erythroid differentiation: hnRNP K and hnRNP E1 regulate 15-lipoxygenase translation from the 3’ end. Cell 89: 597–606.

- Ostareck-Lederer A, D H Ostareck, N Standart , BJ Thiele (1994) Translation of 15-lipoxygenase mRNA is inhibited by a protein that binds to a repeated sequence in the 3’ untranslated region. EMBO J 13: 1476–1481.

- Ostareck-Lederer A, D H Ostareck, C Cans, G Neubauer, K Bomsztyk, et al. (2002) c-Src-mediated phosphorylation of hnRNP K drives translational activation of specifically silenced mRNAs. Mol Cell Biol 22: 4535–4543.

- Novina CD, PA Sharp (2004) The RNAi revolution. Nature 430: 161–164.

- Bartel DP (2004) MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116: 281–297. [crossref]

- Bartel DP, CZ Chen (2004) Micromanagers of gene expression: the potentially widespread influence of metazoan microRNAs. Nat Rev Genet 5: 396–400.

- He Z, Sontheimer EJ (2004) “siRNAs and miRNAs”: a meeting report on RNA silencing. RNA 10: 1165–1173. [crossref]

- Wightman B, I Ha, (1993) G Ruvkun Posttranscriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C. elegans. Cell 75: 855–862.

- Rougvie AE (2001) Control of developmental timing in animals. Nat Rev Genet 2: 690–701. [crossref]

- Lim LP, Glasner ME, Yekta S, Burge CB, Bartel DP (2003) Vertebrate microRNA genes. Science 299: 1540. [crossref]

- Ambros V (2004) The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature 431: 350–355. [crossref]

- Lee RC1, Ambros V (2001) An extensive class of small RNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 294: 862–864. [crossref]

- Lagos-Quintana M, R Rauhut, A Yalcin, J Meyer, W Lendeckel, et al. (2002) Identification of tissue-specific microRNAs from mouse. Curr Biol 12: 735–739.

- Lagos-Quintana M, R Rauhut, W Lendeckel, T Tuschl (2001) Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science 294: 853–858.

- Chen CZ, L Li, HF Lodish, DP Bartel (2004) MicroRNAs modulate hematopoietic lineage differentiation. Science 303: 83–86.

- Houbaviy HB, Murray MF, Sharp PA (2003) Embryonic stem cell-specific MicroRNAs. Dev Cell 5: 351–358.

- Lai EC (2002) Micro RNAs are complementary to 3’ UTR sequence motifs that mediate negative post-transcriptional regulation. Nat Genet 30: 363–364.

- Stark A, Brennecke J, Russell RB, Cohen SM (2003) Identification of Drosophila MicroRNA targets. PLoS Biol 1: E60. [crossref]

- Lewis BP, IH Shih, MW Jones-Rhoades, DP Bartel, CB Burge (2003) Prediction of mammalian microRNA targets. Cell 115: 787–798.

- Bridge AJ, Pebernard S, Ducraux A, Nicoulaz AL, Iggo R (2003) Induction of an interferon response by RNAi vectors in mammalian cells. Nat Genet 34: 263–264. [crossref]

- Sledz CA, Holko M, de Veer MJ, Silverman RH, Williams BR (2003) Activation of the interferon system by short-interfering RNAs. Nat Cell Biol 5: 834–839. [crossref]

- Caput D, B Beutler, K Hartog, R Thayer, S Brown-Shimer et al. (1986) Identification of a common nucleotide sequence in the 3’-untranslated region of mRNA molecules specifying inflammatory mediators. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 83: 1670–1674.

- Shaw G, R Kamen A (1986) conserved AU sequence from the 3’ untranslated region of GM-CSF mRNA mediates selective mRNA degradation. Cell 46: 659–667.

- Dalgleish G, Veyrune JL, Blanchard JM, Hesketh J (2001) mRNA localization by a 145-nucleotide region of the c-fos 3’–untranslated region. Links to translation but not stability. J Biol Chem 276: 13593–13599. [crossref]

- Mignone F, Gissi C, Liuni S, Pesole G (2002) Untranslated regions of mRNAs. Genome Biol 3: REVIEWS0004. [crossref]

- Levy NS, MA Goldberg, AP Levy (1997) Sequencing of the human vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) 3’ ubtranslational region (UTR) conservation of fice hypoxia-inducible RNA-protein binding sites. Biochem Biophys Acta 1352: 167–173.

- Hamilton BJ, E Nagy, JS Malter, BA Arrick, WF Rigby (1993) Association of heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 and C proteins with reiterated AUUUA sequences. J Biol Chem 268: 8881–8887.

- Zhang w, BJ Wagner, K Ehrenman, AW Schaefer, CT DeMaria, et al. (1993) Purification, characterization and cDNA cloning of an AU-rich element RNA-binding protein, AUF1. Mol Cell Biol 13: 7652–7665.

- Nagy E, WFC Rigby (1995) Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase selectively binds AU-rich RNA in the NAD+-binding region (Rossmann fold). J Biol Chem 270: 2755–2763.

- Nakagawa J, H Waldner, S Meyer-Monard, J Hofsteenge, P Jeno, (1955) AUH, a gene encoding an AU-specific RNA binding protein witn intrinsic enoyl-CoA hydratase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 2051–2055.

- Brennan CM, Steitz JA (2001) HuR and mRNA stability. Cell Mol Life Sci 58: 266–277. [crossref]

- Piecyk M, Wax S, Beck AR, Kedersha N, Gupta M, et al. (2000) TIA-1 is a translational silencer that selectively regulates the expression of TNF-alpha. EMBO J 19: 4154–4163. [crossref]

- Chen CY, Gherzi R, Ong SE, Chan EL, Raijmakers R, et al. (2001) AU binding proteins recruit the exosome to degrade ARE-containing mRNAs. Cell 107: 451–464. [crossref]

- Carballo E, WS Lai, PJ Balckshear (1998) Feedback inhibition of macrophage tumor necrosis factor alpha production by tristetraprolin. Science 281: 1001–1005.

- Tchen CR, Brook M, Saklatvala J, Clark AR (2004) The stability of tristetraprolin mRNA is regulated by mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 and by tristetraprolin itself. J Biol Chem 279: 32393–32400. [crossref]

- Brooks SA, JE Connolly, WFC Rigby (2004) The role of mRNA turnover in the regulation of tristetraprolin expression: Evidence for an extracellular signal-regulated kinase-specific, AU-rich element-dependent, autoregulatory pathway. J Immunol 172: 7263–7271.

- Min H, CW Turck, JM Nikolic, DL Black (1997) A new regulatoru protein, KSRP, mediates exon inclusion through an intrionic splicing enhancer. Genes Dev 11: 1023–1036.

- Gherzi R, Lee KY, Briata P, Wegmüller D, Moroni C, et al. (2004) A KH domain RNA binding protein, KSRP, promotes ARE-directed mRNA turnover by recruiting the degradation machinery. Mol Cell 14: 571–583. [crossref]

- Wagner BJ, CT deMaria, Y Sun, GM Wilson, G. Brewer (1998) Structure and genomic organization of the human AUF1 gene: alternative pre-mRNA splicing generated four protein isoforms. Genomics 1: 195–202.

- Wilson GM, J Lu, K Sutphen, Y Sun, Y Huynh, et al. (2003) Regulation of A + U-rich element-directed turnover involving reversible phosphorylation of AUF1. J Biol Chem 278: 33029–33038.

- Dean JLE, G Sully, AR Clark, J Saklatvala (2004) The involvement of AU-rich element-binding proteins in p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway-mediated mRNA stabilization. Cell Signal 16: 1113–1121.

- Kloc M, Zearfoss NR, Etkin LD (2002) Mechanisms of subcellular mRNA localization. Cell 108: 533–544. [crossref]

- Jackson RJ (1993) Cytoplasmic regulation of mRNA function: the importance of the 3’ untranslated region. Cell 74: 9–14. [crossref]

- Hazelrigg T (1998) The destinies and destinations of RNAs. Cell 95: 451–460. [crossref]

- Mowry KL, Cote CA (1999) RNA sorting in Xenopus oocytes and embryos. FASEB J 13: 435–445. [crossref]

- Kuersten S, Goodwin EB (2003) The power of the 3’ UTR: translational control and development. Nat Rev Genet 4: 626–637. [crossref]

- Lawrence JB, R. H (1986) Singer Intracellular localization of messenger RNAs for cytoskeletal proteins. Cell 45: 407–415.

- Hoock TC, PM Newcomb, IM Herman (1991) Beta actin and its mRNA are localized at the plasma membrane and the regions of moving cytoplasm during the cellular response to injury. J Cell Biol 112, 653–664.

- Kislauskis, E H, X Zhu, R H. (1994) Singer Sequences responsible for intracellular localization of beta-actin messenger RNA also affect cell phenotype. J Cell Biol 127: 441–451.

- Ross AF, Oleynikov Y, Kislauskis EH, Taneja KL, Singer RH (1997) Characterization of a beta-actin mRNA zipcode-binding protein. Mol Cell Biol 17: 2158–2165. [crossref]

- Liu G, Grant WM, Persky D, Latham VM Jr, Singer RH, et al. (2002) Interactions of elongation factor 1alpha with F-actin and beta-actin mRNA: implications for anchoring mRNA in cell protrusions. Mol Biol Cell 13: 579–592. [crossref]

- Bergsten SE, Gavis ER (1999) Role for mRNA localization in translational activation but not spatial restriction of nanos RNA. Development 126: 659–669. [crossref]

- Gu W, F Pan, H Zhang, GJ Bassell, RH Singer (2002) A predominantly nuclear protein affecting cytoplasmic localization of beta-actin mRNA in fibroblasts and neurons. J Cell Biol 156: 41–51.

- Farina KL, S Huttelmaier, K Musunuru, R Darnell, RH Singer (2003) Two ZBP1 KH domains facilitate beta-actin mRNA localization, granule formation, and cytoskeletal attachment. J Cell Biol 160: 77–87.

- Nguyen PV, Abel T, Kandel ER (1994) Requirement of a critical period of transcription for induction of a late phase of LTP. Science 265: 1104–1107. [crossref]

- Frey U, M Krug, KG Reymann, H Matthies (1988) Anisomycin, an inhibitor of protein synthesis, blocks late phases of LTP phenomena in the hippocampal CA1 region in vitro. Brain Res 452: 57–65.

- Stanton PK, Sarvey JM (1984) Blockade of long-term potentiation in rat hippocampal CA1 region by inhibitors of protein synthesis. J Neurosci 4: 3080–3088. [crossref]

- Bassell GJ, Zhang H, Byrd AL, Femino AM, Singer RH, et al. (1998) Sorting of beta-actin mRNA and protein to neurites and growth cones in culture. J Neurosci 18: 251–265. [crossref]

- Steward O, PF Worley (2001) Selective targeting of newly synthesized Arc mRNA to active synapses requires NMDA receptor activation. Neuron 30: 227–240.

- Steward O, Worley P (2001) Localization of mRNAs at synaptic sites on dendrites. Results Probl Cell Differ 34: 1–26. [crossref]

- Bassell GJ, Singer RH, Kosik KS (1994) Association of poly(A) mRNA with microtubules in cultured neurons. Neuron 12: 571–582. [crossref]

- Tiruchinapalli DM, YOleynikov, S Kelic, SM Shenoy, A Hartley, et al. (2003) Activity-dependent trafficking and dynamic localization of zipcode binding protein 1 and beta-actin mRNA in dendrites and spines of hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci 23: 3251–3261.

- Mayford M, D Baranes, K Podsypanina, ER Kandel (1996) The 3’-untranslated region of CaMKII alpha is a cis-acting signal for the localization and translation of mRNA in dendrites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 13250–13255.

- Rook MS, M Lu, KS Kosik (2000) CaMKIIalpha 3’ untranslated region-directed mRNA translocation in living neurons: visualization by GFP linkage. J Neurosci 20: 6385–6393.

- Miller S, M Yasuda, J K Coats, Y Jones, M E Martone, et al. (2002) Disruption of dendritic translation of CaMKIIalpha impairs stabilization of synaptic plasticity and memory consolidation. Neuron 36: 507–519.

- Muslimov IA, V Nimmrich, A I Hernandez, A Tcherepanov, TC Sacktor, et al. (2004) Dendritic transport and localization of protein kinase Mzeta mRNA: Implications for molecular memory consolidation. J Biol Chem 279: 52613–52622.

- Yamaguchi R, Newport J (2003) A role for Ran-GTP and Crm1 in blocking re-replication. Cell 113: 115–125. [crossref]

- Chung SW, XY Huang, J Song, R Thomas, PMC Wong (2004) Genetic immune medulation of Ran GTPase against different microbial pathogens. Front BioSci 9: 3374–3383.

- Wong PMC (2002) Hypothesis: Ran GTPase-based potential therapeutic interventions against lethal microbial infections. The Scientific World JOURNAL 2: 684–689.

- Zhao F, Q Yuan, BM Sultzer, SW Chung, PMC Wong (2001) The involvement of Ran GTPase in lipopolysaccharide endotoxin-induced responses. J Endo Res 7: 53–56.

- Askjaer P, Jensen TH, Nilsson J, Englmeier L, Kjems J (1998) The specificity of the CRM1-Rev nuclear export signal interaction is mediated by RanGTP. J Biol Chem 273: 33414–33422.

- Lee SH, M Hannink (2001) The N-terminal nuclear export sequence of IkappaBalpha is required for RanGTP-dependent binding to CRM1. J Biol Chem 276: 23599–23606.

- Turpin P, RT Hay, C Dargemont (1999) Characterization of IkappaBalpha nuclear import pathway. J Biol Chem 274: 6804–6812.

- Tam WF, L H Lee, L Davis, R Sen (2000) Cytoplasmic sequestration of rel proteins by IkappaBalpha requires CRM1-dependent nuclear export. Mol Cell Biol 20: 2269–2284.

- Nakamura M, H Masuda, J Horii, K Kuma, N Yokoyama, et al. (1998) When overexpressed, a novel centrosomal protein, RanBPM, causes ectopic microtubule nucleation similar to gamma-tubulin. J Cell Biol 143: 1041–1052.

- Nishitani H, E Hirose, Y Uchimura, M Nakamura, M Umeda, et al. (2001) Full-sized RanBPM cDNA encodes a protein possessing a long stretch of proline and glutamine within the N-terminal region, comprising a large protein complex. Gene 272: 25–33.

- Rao MA, H Cheng, AN Quayle, H Nishitani, CC Nelson, et al. (2002) RanBPM, a nuclear protein that interacts with and regulates transcriptional activity of androgen receptor and glucocorticoid receptor. J Biol Chem 277: 48020–48027.

- Denti S, Sirri A, Cheli A, Rogge L, Innamorati G, et al. (2004) RanBPM is a phosphoprotein that associates with the plasma membrane and interacts with the integrin LFA-1. J Biol Chem 279: 13027–13034. [crossref]

- Wang D, Li Z, Messing EM, Wu G (2002) Activation of Ras/Erk pathway by a novel MET-interacting protein RanBPM. J Biol Chem 277: 36216–36222. [crossref]

- Wang D, Z Li, SR Schoen, EM Messing, G Wu (2004) A novel MET-interacting protein shares high sequence similarity with RanBPM, but fails to stimulate MET-induced Ras/Erk signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 313: 320–326.

- Drivas G, Massey R, Chang HY, Rush MG, D’Eustachio P (1991) Ras-like genes and gene families in the mouse. Mamm Genome 1: 112–117. [crossref]

- Drivas GT, Shih A, Coutavas E, Rush MG, D’Eustachio P (1990) Characterization of four novel ras-like genes expressed in a human teratocarcinoma cell line. Mol Cell Biol 10: 1793–1798. [crossref]

- Coutavas EE, Hsieh CM, Ren M, Drivas GT, Rush MG, et al. (1994) Tissue-specific expression of Ran isoforms in the mouse. Mamm Genome 5: 623–628. [crossref]

- Mathews DH, J Sabina, M Zuker, DH Turner (1999) Expanded sequence dependence of thermodynamic parameters improves prediction of RNA secondary structure. J Mol Biol 288: 911–940.

- Zuker M (2003) Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res 31: 3406–3415. [crossref]

- Wedemeyer N, T Schmitt-John, D Evers, C Thiel, D Eberhard, et al. (2000) Conservation of the 3’-untranslated region of the Rab1a gene in amniote vertebrates: exceptional structure in marsupials and possible role for posttranscriptional regulation. FEBS Lett 477: 49–54.

- Hall A, Brown R (1985) Human N-ras: cDNA cloning and gene structure. Nucleic Acids Res 13: 5255–5268. [crossref]

- Lai EC, C Wiel, GM Rubin (2004) Complementary miRNA pairs suggest a regulatory role for miRNA: miRNA duplexes. RNA 10: 171–175.

- Lai EC, C Burks, JW Posakony (1998) The K box, a conserved 3’ UTR sequence motif, negatively regulates accumulation of enhancer of split complex transcripts. Development 125: 4077–4088.