Abstract

Three monosubstituted viologen derivatives: 1-(4-indolylphenyl)-4,4′-bi-pyridine hexafluorophosphate (IV), 1-(4-phenothiazinylphenyl)-4,4′-bipyridine hexa-fluorophosphate (PV) and 1-(4-benzimidazolylphenyl)-4,4′-bipyridine hexafluoro-phosphate 1(BV), were synthesized. The electrochemical and electrochromic properties of these monosubstituted viologen derivatives were investigated. The flexible and rigid electrochromic devices (ECD) were prepared by using the synthesized viologen derivatives as active materials. The structure of the device is ITO-PET (or ITO-glass)/ electrochromic gel film/ITO-PET (or ITO-glass). The flexible and rigid ECDs exhibited reversible color changes under applied voltage. Upon applied voltage from 0.0 V to -1.4 V, IV-based flexible ECD exhibited optical contrast 33.5% at 564 nm, PV-based flexible ECD exhibited optical contrast 37.4% at 564 nm and BV-based flexible ECD exhibited optical contrast 45.8% at 466 nm.

Keywords

Monosubstituted viologen derivatives, Electrochromic, Electrochromic device, Flexible device, Optical contrast

Introduction

Electrochromism refers to the phenomenon that materials can exhibit reversible electrochemical oxidation or reduction and change their color reversibly under the application of appropriate voltage [1-3]. After years of development, the technology of electrochromism has been applied in some fields such as information display device [4], smart window [5] and anti-glare rearview mirror [6]. In general, electrochromic materials can be divided into inorganic and organic electrochromic materials. Inorganic electrochromic materials include transition metal oxides such as WO3 [7], NiO [8,9], MoO3 [10,11] and Prussian blue [12]. Organic electrochromic materials include small molecule optoelectronics materials [13], oligomer [14-16] and conjugated polymers [17-19]. As a typical of organic electrochromic materials, 1,1′-disubstituted-4,4′-bipyridinium salts (viologen) are widely reported due to their good electrochromic properties [20-25]. However, a large number of reports on viologen mainly focus on disubstituted viologen derivatives [26-29], and there are few reports on monosubstituted viologen derivatives [30,31].

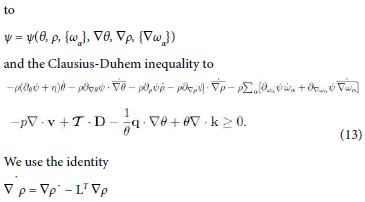

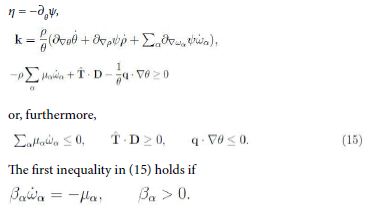

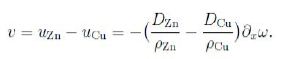

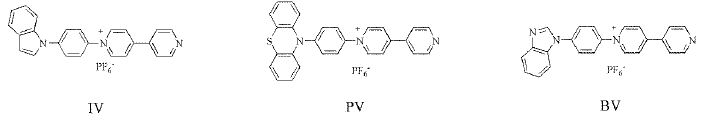

In this paper, three monosubstituted monosubstituted viologen derivatives (Figure 1): 1-(4-indolylphenyl)-4,4′-bipyridine hexafluorophosphate (IV), 1-(4-phenothiazin-ylphenyl)-4,4′-bipyridine hexafluorophosphate (PV) and 1-(4-benzimidazolylphenyl)-4,4′-bipyridine hexafluorophosphate (BV), were synthesized. The electrochromic properties of these monosubstituted viologen derivatives were investigated.

Figure 1: The molecular structural of three monosubstituted viologen derivatives

Materials and Methods

Materials

All the solvents were purified and dried using standard methods. Indole, phenothiazine, benzimidazole, 1-fluoro-4-nitrobenzene, 4,4’-bipyridine, 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene, ammonium hexafluorophosphate (NH4PF6), 10% palladium on carbon (Pd/C), hydrazine hydrate and polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) were purchased from Beijing HWRK Chem Co., Ltd. Ferrocene, tetrahydrofuran (THF), potassium carbonate (K2CO3) and N,N’-dimethylformamide (DMF) were purchased from Shanghai RichJoint Chemical Reagents Co., Ltd. Petroleum ether, ethanol, ethyl acetate, dichloromethane (DCM) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were purchased from Shanghai Titan Scientific Co., Ltd. Methanol, propylene Carbonate (PC) and anhydrous tetra-n-butylammonium perchlorate (TBAP) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Indium tin oxide (ITO) glasses (10 Ω/sq) and ITO polyethylene terephthalate (PET, 30-35 Ω/sq) were purchased from Zhuhai Kaivo Optoelectronic Technology Co., Ltd.

Instrumentation

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded on a Bruker AVANCE-600 NMR spectrometer. Mass spectra were carried out on Bruker Agilent 1290 mass spectrometer. UV-vis spectra of compounds were measured on a Thermo Helios-γ spectrometer. Electrochemical properties of compounds were measured on CHI750A electrochemical workstation. A saturated calomel electrode (SCE), platinum wire, and ITO-glass were used as the reference electrode (RE), counter electrode (CE), and working electrode (WE), respectively. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) of ECDs was measured at a frequency in the range of 0.01 Hz–100 kHz on CHI750A electrochemical workstation to calculate the ionic conductivity of the prepared ion gels. Electrochromic properties of ECDs were measured on CHI750A electrochemical workstation and UV-vis spectrometer integrated with an electrochromic cyclic tester (Zhuhai Kaivo Optoelectronic Technology Co., Ltd.).

Synthesis

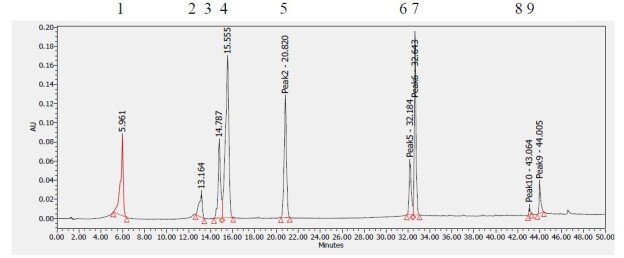

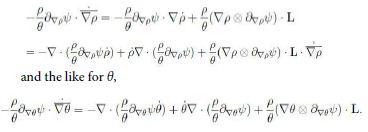

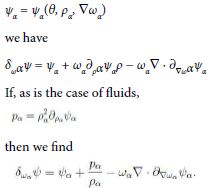

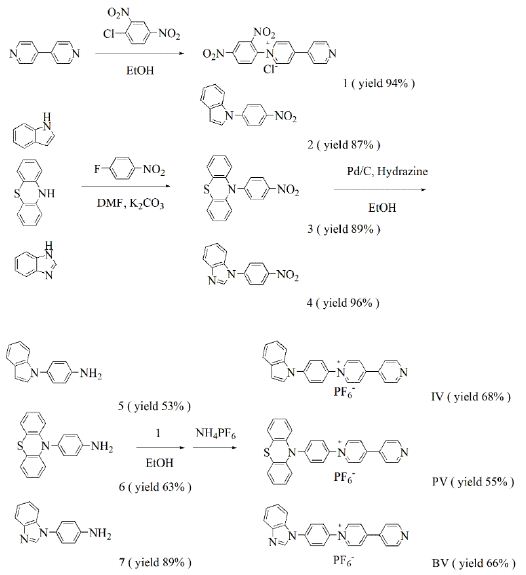

The synthetic routes to IV, PV and BV are shown in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1: Synthetic routes for the viologen derivatives

Compound 1

4,4’-Bipyridine (3.6 g, 23.0 mmol), 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene (2.3 g, 11.7 mmol) and ethanol (60 mL) were added to a three-necked flask. The mixture was stirred at 80℃ in N2 atmosphere for 48 h. After the reaction, solution was cooled to room temperature, evaporated to give a crude product and washed with DCM (100 mL) to obtain grey solid (3.96 g, yield 94%). 1H NMR (D2O, 600 MHz, ppm) δ 9.41 (d, 1H), 9.27 (d, 2H), 8.96 (d, 1H), 8.84 (s, 2H), 8.70 (s, 2H), 8.31 (s, 1H), 8.04 (s, 2H).

Compound 2

Indole (1.1 g, 9.4 mmol), 1-fluoro-4-nitrobenzene (1.4 g, 9.9 mmol), K2CO3 (1.3 g, 9.4 mmol) and DMF (20 ml) were added to a three-necked flask. The mixture was stirred at 110°C for 24 h under a N2 atmosphere. After the reaction, solution was cooled to room temperature, cold water was added, precipitated and filtered to obtain crude product. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography using ethyl acetate/petroleum ether (1:10, v/v) to obtain a yellow powder (1.96 g, yield 87%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz, ppm): δ 8.41 (d, 2H), 7.92 (d,2H), 7.83 (d,1H), 7.76 (d,1H), 7.70 (d, 1H), 7.29 (t, 1H), 7.21 (t, 1H), 6.83 (d, 1H).

Compound 3

Phenothiazine (2.0 g, 10.0 mmol), 1-fluoro-4-nitrobenzene (1.5 g, 10.6 mmol), K2CO3 (1.4 g, 10.1 mmol) and DMF (35 ml) were added to a three-necked flask. The mixture was stirred at 110°C for 24 h under a N2 atmosphere. After the reaction, solution was cooled to room temperature, cold water was added, precipitated and filtered to obtain crude product. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography using DCM/petroleum ether (1:10, v/v) to obtain a yellow powder (2.85 g, yield 89%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz, ppm): δ 8.12 (d, 2H), 7.64 (d, 2H), 7.58 (d, 2H), 7.49 (t, 2H), 7.36 (t, 2H), 7.05 (d, 2H).

Compound 4

Benzimidazole (2.5 g, 21.1 mmol), 1-fluoro-4-nitrobenzene (3.3 g, 23.7 mmol), K2CO3 (3.3 g, 23.8 mmol) and DMF (60 mL) were added to a three-necked flask. The mixture was stirred at 110°C for 24 h under a N2 atmosphere. After the reaction, solution was cooled to room temperature, cold water was added, precipitated and filtered to obtain crude product. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography using ethyl acetate/petroleum ether (1:2, v/v) to obtain a yellow powder (4.91 g, yield 96%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz, ppm) δ 8.75 (s, 1H), 8.47 (d, 2H), 8.04 (d, 2H), 7.80 (dd, 2H), 7.39 (dt, 2H).

Compound 5

2 (1.0 g, 4.2 mmol), 10% Pd/C (0.15 g), hydrazine hydrate (3.5 mL) and ethanol (65 ml) were added to a three-necked flask. The mixture was stirred at 80℃ in N2 atmosphere for 15 h. After the reaction, solution was filtered while hot, and the filtrate was evaporated to give a crude product. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography using acetate/petroleum ether (1:4, v/v) to obtain a brown oily liquid (0.46 g, yield 53%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz, ppm): δ 7.61 (d, 1H), 7.44 (d, 1H), 7.37 (d, 1H), 7.17 (d, 2H), 7.15-7.11 (m, 1H), 7.09 – 7.04 (m, 1H), 6.72 (d, 2H), 6.59 (d, 1H), 5.30 (s, 2H).

Compound 6

3 (1.5 g, 4.7 mmol), 10% Pd/C (0.16 g), hydrazine hydrate (4 ml) and ethanol (40 ml) were added to a three-necked flask. The mixture was stirred at 80℃ in N2 atmosphere for 15 h. After the reaction, solution was filtered while hot, and the filtrate was evaporated to give a crude product. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography using acetate/petroleum ether (1:10, v/v) to obtain a white solid (0.86 g, yield 63%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz, ppm): δ 7.00 (t,4H), 6.92 – 6.87 (m, 2H), 6.79 (t,4H), 6.21 (d, 2H), 5.43 (s, 2H).

Compound 7

4 (3.0 g, 12.7 mmol), 10% Pd/C (0.31 g), hydrazine hydrate (10 mL) and ethanol (60 ml) were added to a three-necked flask. The mixture was stirred at 80℃ in N2 atmosphere for 15 h. After the reaction, solution was filtered while hot, and the filtrate was evaporated to give a crude product. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography using acetate/petroleum ether (1:1, v/v) to obtain a red oily liquid (2.37 g, yield 89%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz, ppm) δ 8.35 (s, 1H), 7.75 (dd, 1H), 7.46 (dd, 1H), 7.31-7.24 (m, 4H), 6.79-6.74 (m, 2H), 5.45 (s, 2H).

1-(4-Indolylphenyl)-4,4′-Bipyridine Hexafluorophosphate (IV)

1 (0.4 g, 1.1 mmol), 5 (0.3 g, 1.4 mmol) and ethanol (40 mL) were added to a three-necked flask. The mixture was stirred at 80℃ in N2 atmosphere for 48 h. After the reaction, solution was cooled to room temperature, evaporated to give a crude product and washed with DCM (100 mL) to give orange solid. The crude product was dissolved in water/methanol (1:1, v/v) to obtain saturated solution. NH4PF6 (1.7 g) was added to the solution. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 0.5h, and then the mixture was filtered to obtain yellow solid (0.38 g, yield 68%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz, ppm) δ 9.63 (d, 2H), 8.93 (d, 2H), 8.87 (d, 2H), 8.20 (dd, 4H), 8.04 (d, 2H), 7.83 (d, 1H), 7.72 (d, 2H), 7.30 (t, 1H), 7.21 (t, 1H), 6.83 (d, 1H). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 151 MHz, ppm) δ 153.6, 151.6, 145.9, 141.8, 141.1, 140.1, 135.3, 130.1, 128.9, 127.0, 125.8, 124.9, 123.4, 122.6, 121.7, 121.4, 110.9, 105.4. HRMS (ESI) C24H18N3+ found [M]+: 348.1509, calcd. 348.1495.

1-(4-Phenothiazinylphenyl)-4,4′-Bipyridine Hexafluorophosphate (PV)

1 (0.2 g, 0.5 mmol), 6 (0.2, 0.7 mmol) and ethanol (50 mL) were added to a three-necked flask. The mixture was stirred at 80℃ in N2 atmosphere for 48 h. After the reaction, solution was cooled to room temperature, evaporated to give a crude product and washed with DCM (100 mL) to give orange solid. The crude product was dissolved in water/methanol (1:1, v/v) to obtain saturated solution. NH4PF6 (0.8 g) was added to the solution. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 0.5 h, and then the mixture was filtered to obtain yellow solid (0.12 g, yield 55%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz, ppm) δ 9.57 (d, 2H), 8.92 (d, 2H), 8.85 (d, 2H), 8.20 (d, 2H), 8.04 (d, 2H), 7.53 (d, 2H), 7.38 (d, 2H), 7.25 (t, 2H), 7.14 (t, 2H), 6.90 (d, 2H). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 151 MHz, ppm) δ 153.3, 151.5, 145.8, 145.7, 142.5, 141.1, 139.2, 128.4, 128.1, 127.4, 126.6, 125.8, 125.4, 124.9, 122.6, 122.0. HRMS (ESI) C28H20N3S+ found [M]+: 430.1388, calcd. 430.1372.

1-(4-Benzimidazolylphenyl)-4,4′-Bipyridine Hexafluorophosphate (BV)

1 (0.9 g, 2.5 mmol), 7 (0.9 g, 4.3 mmol) and ethanol (40 mL) were added to a three-necked flask. The mixture was stirred at 80℃ in N2 atmosphere for 48 h. After the reaction, solution was cooled to room temperature, evaporated to give a crude product and washed with DCM (100 mL) to give yellow solid. The crude product was dissolved in water/methanol (1:1, v/v) to obtain saturated solution. NH4PF6 (4.0 g) was added to the solution. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 0.5 h, and then the mixture was filtered to obtain yellow solid (0.58 g, yield 66%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 600 MHz, ppm) δ 9.62 (d, 2H), 8.93 (d, 2H), 8.87 (d, 2H), 8.76 (s, 1H), 8.23 (d, 2H), 8.20 (d, 2H), 8.16 (d, 2H), 7.80 (dd, 2H), 7.41 (dt, 2H). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 151 MHz, ppm) δ 153.81 (s), 151.61 (s), 146.05 (s), 144.44 (s), 143.82 (s), 141.34 (s), 141.04 (s), 138.75 (s), 133.13 (s), 127.27 (s), 125.76 (s), 125.13 (s), 124.46 (s), 123.49 (s), 122.57 (s), 120.69 (s), 111.23 (s). HRMS (ESI): [C23H17N4+]+: 349.1452, calcd. For 349.1448.

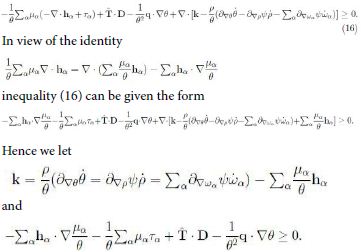

The Fabrication of Electrochromic Devices

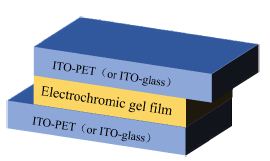

Two ITO-PET (2 cm × 5 cm, or ITO-glass: 2 cm × 3 cm) were used as the working electrode and the counter electrode, respectively. Electrochromic gel (TBAP: PMMA: PC=3:7:90, w/w) contain 0.01 M monosubstituted viologen derivatives and 0.01 M ferrocene was injected into the sealing device. The thickness of the electrochromic gel film is 1 mm. The structure of the device was ITO-PET (or ITO-glass)/electrochromic gel film/ITO-PET (or ITO-glass). EIS of rigid ECDs based on IV, PV and BV are shown in Figure S17(a)-(c). Figure S17(d) is the corresponding analog equivalent circuit. Rs is resistance of the gel electrolyte. Rct is charge transfer resistance. CPE is double-layer capacitance. Zw is Warburg impedance. According to formula (1), ionic conductivity (σ) of IV, PV and BV-based gel were 1.21×10-5 S/cm, 1.59×10-5 S/cm and 1.88×10-5 S/cm, respectively. S is area of gel film (Scheme 2).

σ=d/(Rs×S) (1)

Scheme 2: Structure diagram of electrochromic device

Results and Discussion

Optoelectrochemical Properties of Monosubstituted Viologen Derivatives

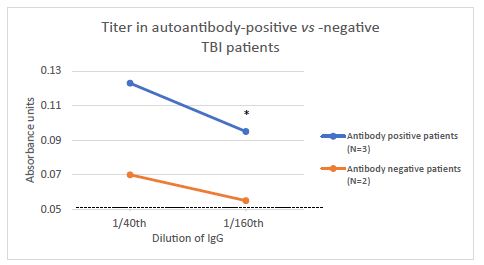

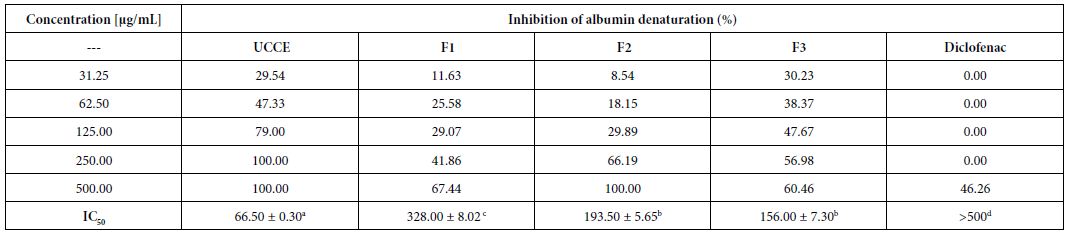

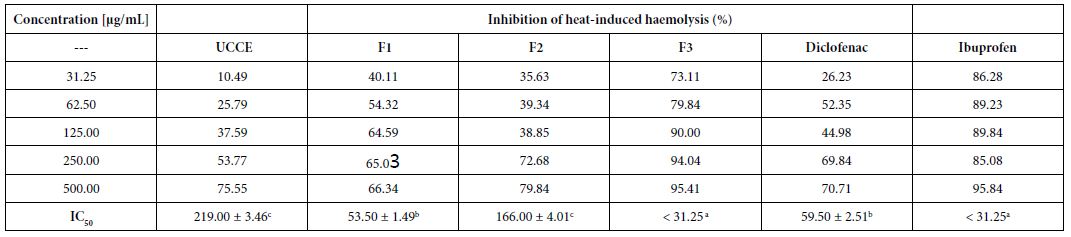

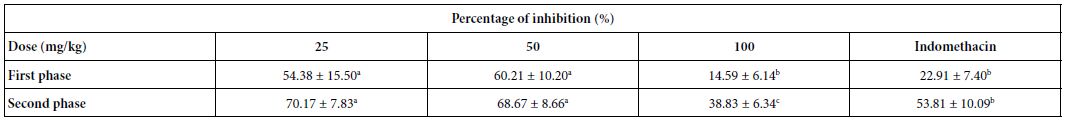

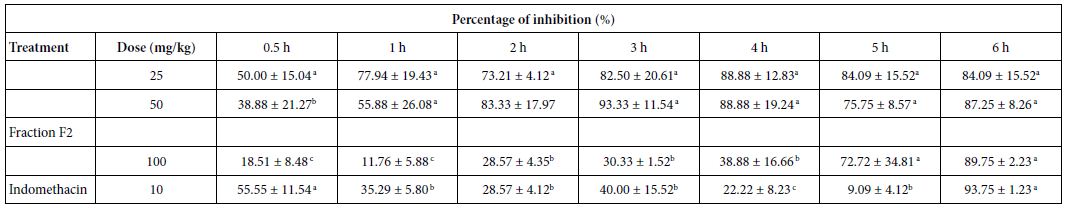

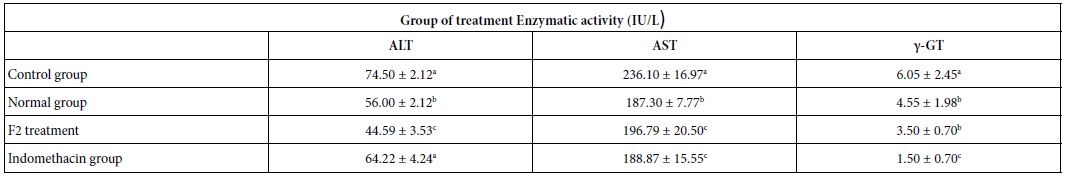

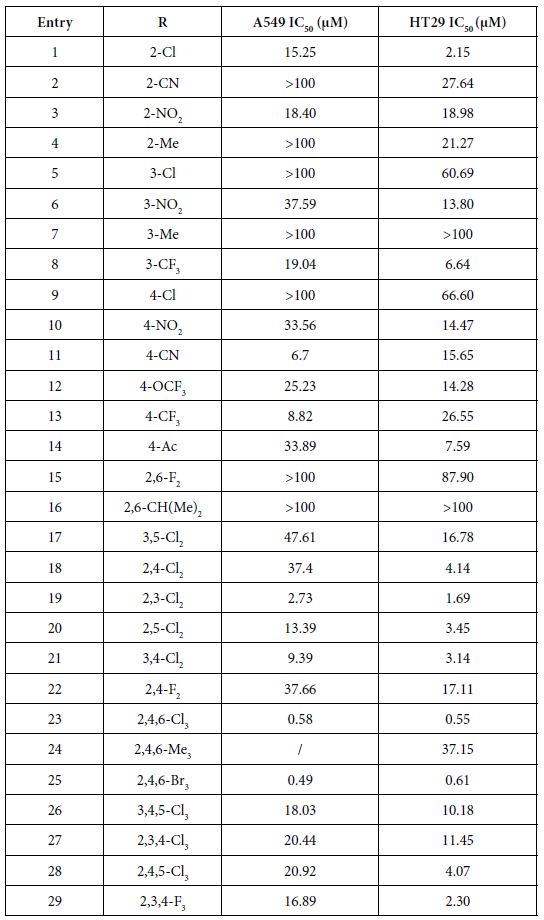

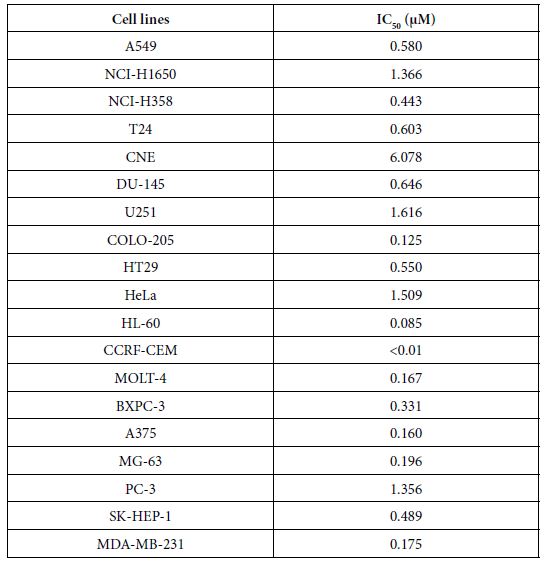

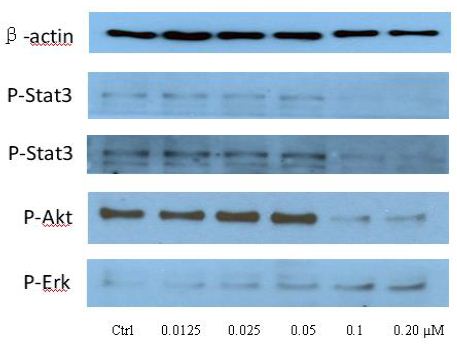

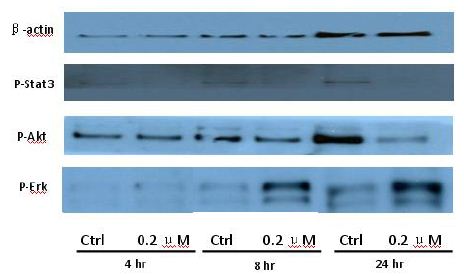

Cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of IV, PV and BV were recorded at a scan rate of 50 mV/s in PC solution containing 0.1 M TBAP. As is shown in Figure S18, the initial reduction potentials (Eredonset) of IV, PV and BV were -0.64 V, -0.19 V and -0.24 V, respectively. UV-Vis absorption spectra of IV, PV and BV in PC solution are shown in Figure S19. The absorption peaks(λmax)of IV, PV and BV were located at 361, 394/424 and 333/421 nm, respectively. The band edge wavelength (λedge) of IV, PV and BV were 496, 564 and 434 nm respectively. According to formula (2), (3) and (4), optical band gap (Egopt), HOMO energy levels (EHOMO) and LUMO energy levels (ELUMO) of monosubstituted viologen derivatives were calculated. Table S1 shows the optoelectrochemical properties of IV, PV and BV.

Egopt = 1240/λedge (2)

ELUMO=-e(Eredonset+4.4) (3)

EHOMO=ELUMO-Egopt (4)

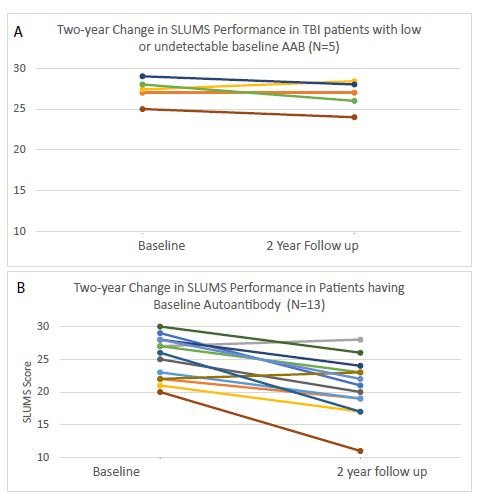

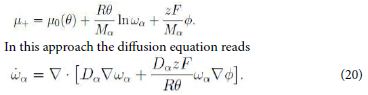

Electrochromic Properties of ECDs based on Monosubstituted Viologen Derivatives

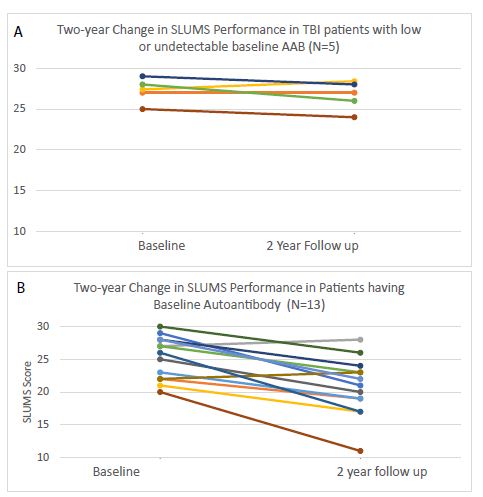

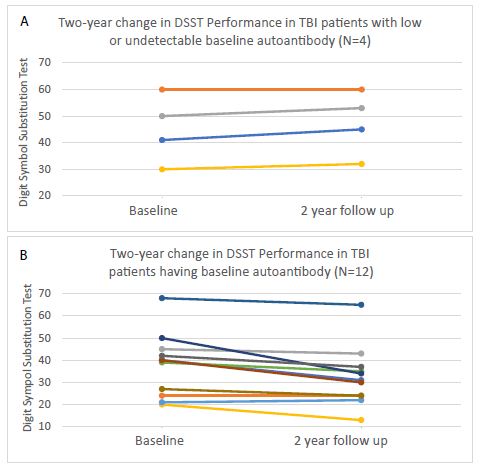

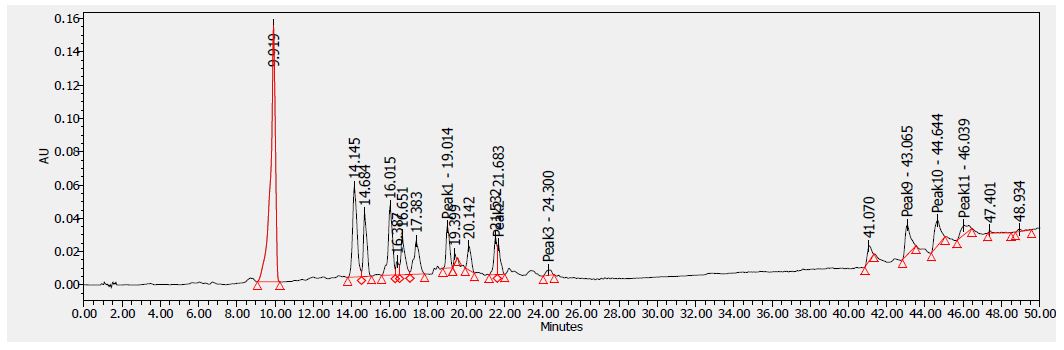

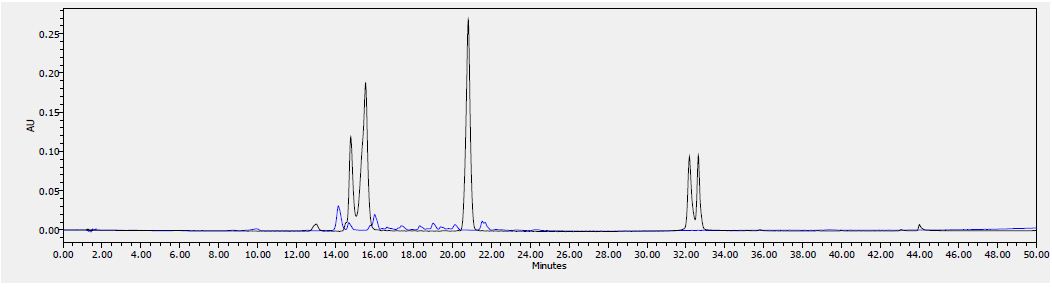

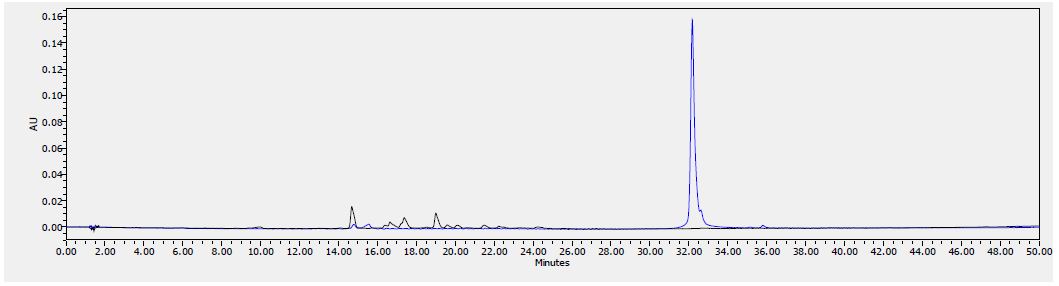

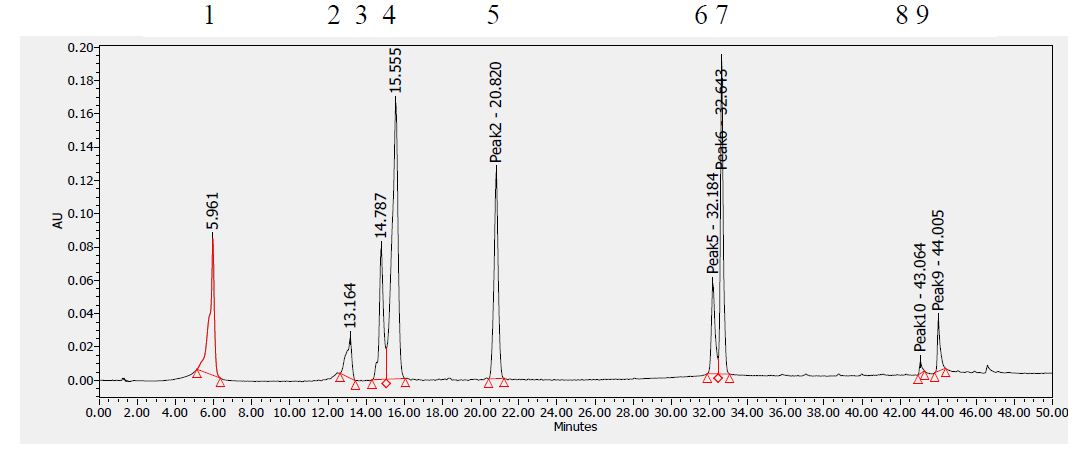

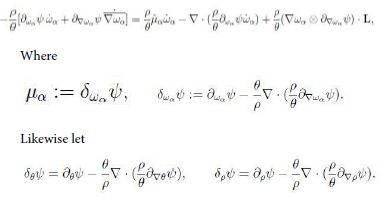

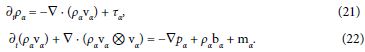

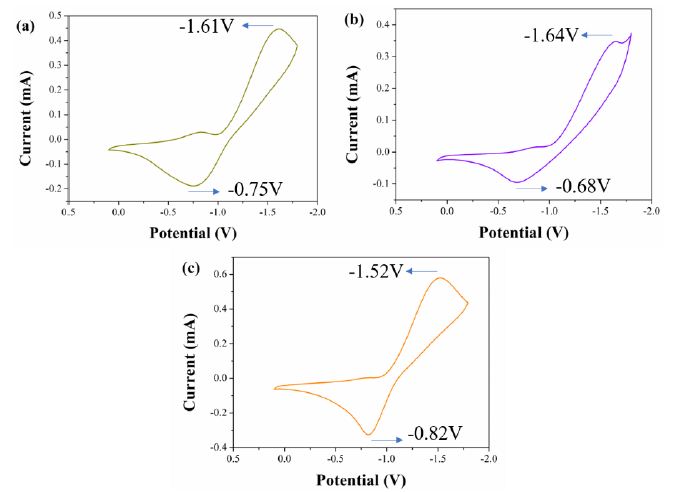

Figure 2 shows CVs of flexible ECDs based on the monosubstituted viologen derivatives at a scan rate of 50 mV/s. All CVs of flexible ECDs exhibited one pair of redox peaks during the redox process which corresponded to the redox processes of monosubstituted viologen derivatives. The reduction peaks of flexible ECDs based on IV, PV and BV were -1.61, -1.64 and -1.52 V, respectively, which correspond to the reduction of cations to neutral state of monosubstituted viologen derivatives. Rigid ECDs based on monosubstituted viologen derivatives were fabricated by using ITO-glass instead of ITO-PET. As is shown in Figure S20, flexible and rigid ECDs based on monosubstituted viologen derivatives exhibited the same redox behavior.

Figure 2: CVs of (a) IV-based flexible ECD, (b) PV-based flexible ECD and (c) BV-based flexible ECD at a scan rate of 50 mV/s

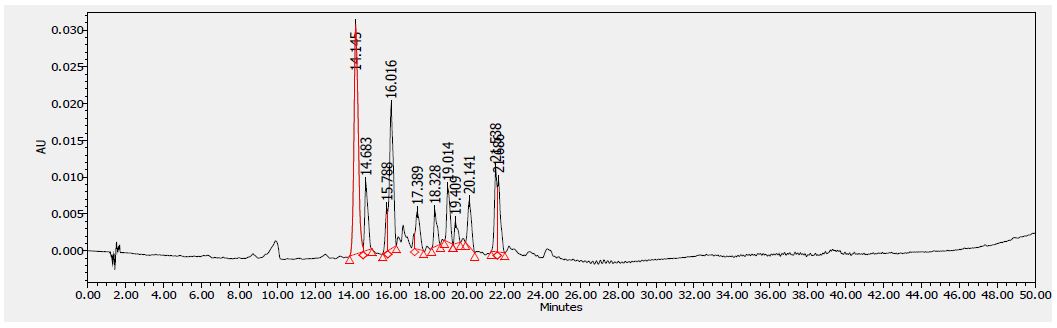

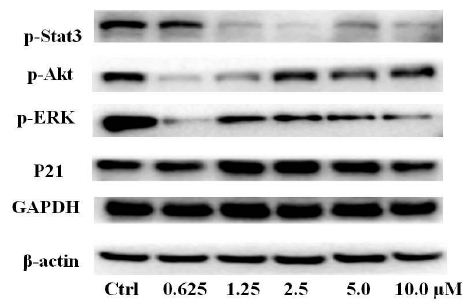

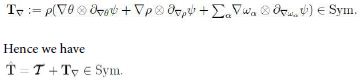

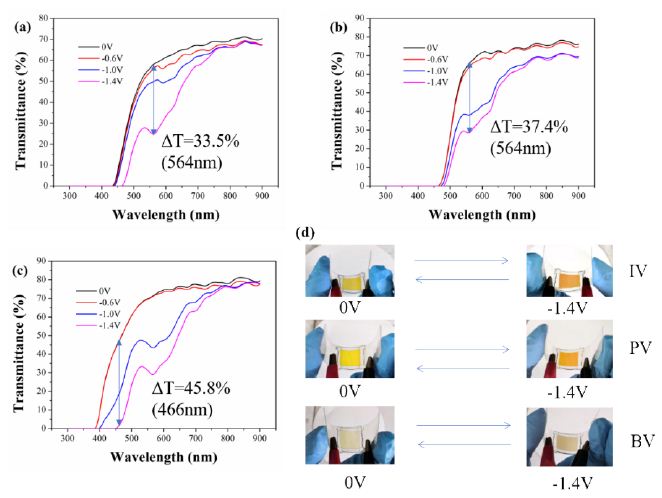

The spectroelectrochemistry of flexible ECDs based on viologen derivatives under different applied voltages and the color change of flexible ECDs are shown in Figure 3. With the increase of applied voltage, the transmittance of flexible ECDs based on synthesized viologen derivatives in the visible region decreased. For flexible ECD based on IV, it was yellow under no voltage applied. When the applied voltage was -1.4 V, it exhibited a color change from yellow to orange. For flexible ECD based on PV, it was yellow under no voltage applied. When the applied voltage was -1.4 V, it exhibited a color change from yellow to orange red. For flexible ECD based on BV, it was light yellow under no voltage applied. When the applied voltage was -1.4 V, it exhibited a color change from light yellow to light brown. The spectroelectrochemistry of flexible ECDs based on monosubstituted viologen derivatives showed that three kinds of flexible ECDs had reversible color change, which indicated the introduction of groups of indole, phenothiazine and benzimidazole can effectively adjust the electrochromic properties of viologen derivatives. In addition, under the bending state, the flexible ECDs still exhibited reversible color change under the applied voltage.

Figure 3: Spectroelectrochemistry of (a) IV-based flexible ECD, (b) PV-based flexible ECD and (c) BV-based flexible ECD under different applied voltages and the image of corresponding devices

The optical contrast is defined as difference of transmittance under different applied voltage at the same wavelength. According to Figure 3, the optical contrast of the flexible ECDs based on IV, PV and BV reached 33.5% (564 nm), 37.4% (564 nm) and 45.8% (466 nm) , respectively. As is shown in Figure S21, the electrochromism of rigid ECDs was consistent with that of flexible ECDs. The optical contrast of the rigid ECDs based on IV, PV and BV reached 42.4% (582 nm), 44.1% (584 nm) and 44.0% (568 nm), respectively.

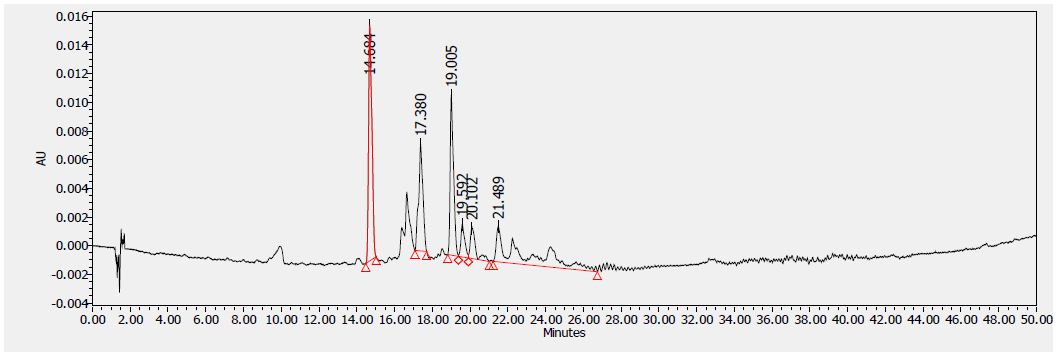

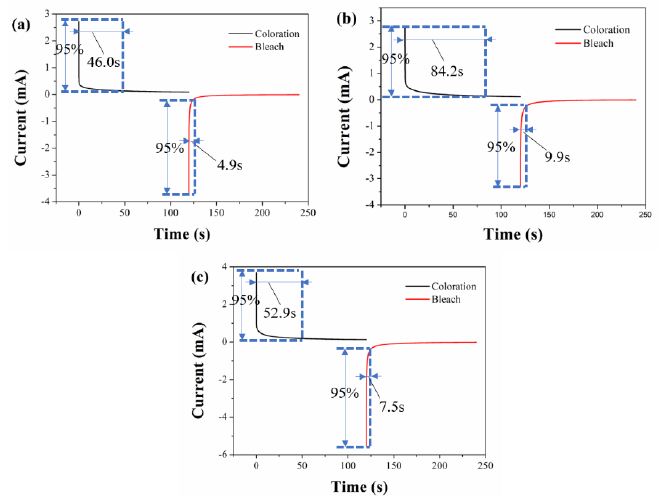

Switching time is defined as time required for the current to change by 95% under the applied voltage. Switching time includes response time from bleached state to colored state (coloring time) and response time from colored state to bleached state (bleaching time), which was measured using double-step chronoamperometry. The current-time curves of flexible ECDs based on IV, PV and BV are shown in Figure 4. For flexible ECD based on IV, the coloring and bleaching times were 46.0 s and 4.9 s, respectively. For flexible ECD based on PV, the coloring and bleaching times were 84.2 s and 9.9 s, respectively. For flexible ECD based on BV, the coloring and bleaching times were 52.9 s and 7.5 s, respectively. The current-time curves of rigid ECDs based on IV, PV and BV are shown in Figure S22. The results showed that the coloring times of flexible ECDs were longer than those of rigid ECDs. The reason may be that ITO-PET has higher surface resistance than that of ITO-glass, which makes it difficult for cations to get electrons at the cathode.

Figure 4: Current-time curves of (a) IV-based flexible ECD, (b) PV-based flexible ECD and (c) BV-based flexible ECD (switched upon voltages between 0.0 V and -1.4 V with a switching interval of 120 s)

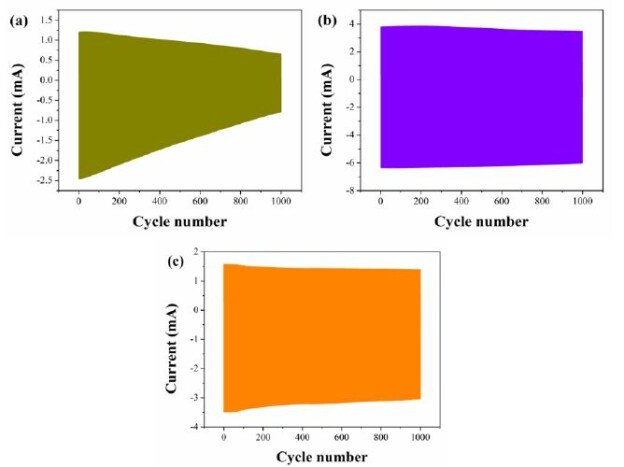

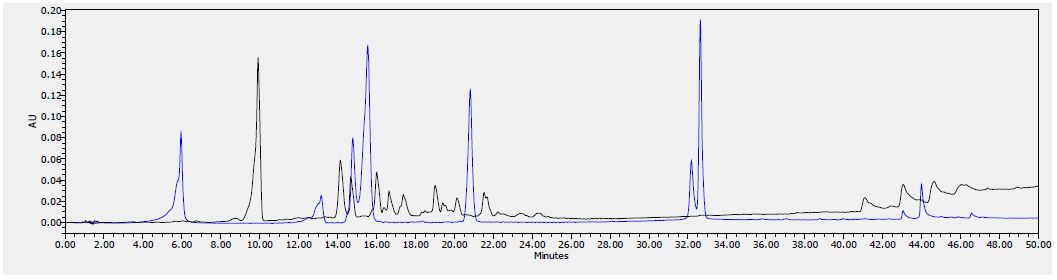

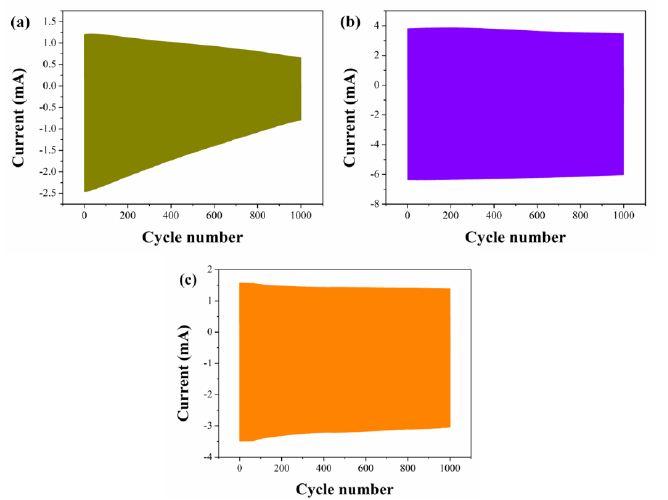

The stability of flexible ECDs based on 2IV, 2PV and 2BV were also measured using chronoamperometry. As is shown in Figure 5, the flexible ECD based on IV, PV and BV remained 51.1%, 97.6% and 72.7% of the original electric charge after 1000 cycles, respectively. The stability of rigid ECDs based on 2IV, 2PV and 2BV was shown in Figure S23. All the ECDs exhibited suitable cyclic stability.

Figure 5: Properties in write-erase ability of (a) IV-based flexible ECD, (b) PV-based flexible ECD and (c) BV-based flexible ECD

The coloration efficiency (η) refers to the ratio of the change of optical density to charge at a specific wavelength which is used to measure the charge utilization of the device. According to Formula (5), coloration efficiency of ECDs based on IV, PV and BV was calculated. Flexible ECDs based on IV, PV and BV have coloration efficiency of 129.67 cm2/C (564 nm), 87.78 cm2/C (564 nm) and 107.22 cm2/C (466 nm), respectively. Rigid ECDs based on IV, PV and BV have coloration efficiency of 197.84 cm2/C (582 nm), 198.70 cm2/C (584 nm) and 201.50 cm2/C (568 nm), respectively. Electrochromic properties of ECDs based on 2IV, 2PV and 2BV are presented in Table S2.

η = ΔOD/Q; ΔOD = log (Tb/Tc) (5)

ΔOD is the change in optical density; Q is the amount of charge injected (or extracted) per unit area (C/cm2); Tc is the transmittance (%) of the colored state; Tb is the transmittance (%) of the bleached state.

Conclusion

In summary, three monosubstituted viologen derivatives IV, PV and BV were synthesized and corresponding flexible and rigid electrochromic devices were fabricated. All flexible and rigid ECDs exhibited reversible color changes upon applied voltage. In addition, flexible ECDs still exhibited reversible color change under bending state. IV-based flexible ECD exhibited reversible color changes from yellow to orange upon applied voltage from 0.0 V to -1.4 V, and it exhibited optical contrast 33.5% at 564 nm. PV-based flexible ECD exhibited reversible color changes from yellow to orange red upon applied voltage from 0.0 V to -1.4 V, and it exhibited optical contrast 37.4% at 564 nm. BV-based flexible ECD exhibited reversible color changes from light yellow to light brown upon applied voltage from 0.0 V to -1.4 V, and it exhibited optical contrast 45.8% at 466 nm. All ECDs exhibited suitable switching time and suitable coloration efficiency.

Author Contributions

Weijie Ye: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing-original draft, Conceptualization, Software, Data curation. Xu Guo: Visualization. Peng Wang and Chao Qian: Validation. Ping Liu: Resources, Writing-review and editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the NSFC (Grant no. 20674022, 20774031, and 21074039), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong (Grant no. 2014A030313241, 2014B090901068, 2016A010103003, and 2021A1515010929), and the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (Grant no. 20090172110011).

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

References

- Liu W, Zhang X, Liu J, Ma X, Zeng J, et al. (2017) Electrochromic properties of organic-inorganic composite materials. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 718: 379-385.

- Li M, Wei Y, Zheng J, Zhu D, Xu C (2014)Highly contrasted and stable electrochromic device based on well-matched viologen and triphenylamine. Organic Electronics 15: 428-434.

- Wang Z, Wang X, Cong S, Geng F, Zhao Z (2020) Fusing electrochromic technology with other advanced technologies: A new roadmap for future development. Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports 140.

- Zhang W, Wang X, Wang Y, Yang G, Gu C, et al. (2019) Bio-inspired ultra-high energy efficiency bistable electronic billboard and reader. Nature Communications.10: 1559.[crossref]

- Song R, Li G, Zhang Y, Rao B, Xiong S, He G (2021) Novel electrochromic materials based on chalcogenoviologens for smart windows, E-price tag and flexible display with improved reversibility and stability. Chemical Engineering Journal 422: 130057.

- Rosseinsky DR, Mortimer RJ (2001) Electrochromic Systems and the Prospects for Devices. Advanced Materials 13: 783-793.

- Chen J, Wang Z, Chen Z, Cong S, Zhao Z (2020) Fabry–Perot Cavity-Type Electrochromic Supercapacitors with Exceptionally Versatile Color Tunability. Nano Letters 20: 1915-1922.[crossref]

- Kim KH, Jeong SJ, Koo BR, Ahn HJ (2021) Surface amending effect of N-doped carbon-embedded NiO films for multirole electrochromic energy-storage devices. Applied Surface Science 537: 147902.

- Ma D, Shi G, Wang H, Zhang Q, Li Y (2013) Hierarchical NiO microflake films with high coloration efficiency, cyclic stability and low power consumption for applications in a complementary electrochromic device. Nanoscale 5: 4808-4815.[crossref]

- Novak TG, Kim J, Tiwari AP, Kim J, Lee S, et al. (2020) 2D MoO3 Nanosheets Synthesized by Exfoliation and Oxidation of MoS2 for High Contrast and Fast Response Time Electrochromic Devices. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering.8: 11276-11282.

- Santhosh S, Nanda Kumar AK, Kennedy J, Subramanian B (2020)Electrochromic response of pulsed laser deposited oxygen deficient monoclinic β-MoO3 thin films.Electrochimica Acta 354: 136745.

- Li X, Chu J, Cheng Y, Yang F, Xiong S (2020) Novel prussian blue@Carbon-dots hybrid thin film: The impact of carbon-dots on material structure and electrochromic performance. Electrochimica Acta 355: 136659.

- Zhang X, Zeng J, Xu Z, Zhu M, Liu P (2021) A fast-response electrochromic device based on a composite gel film comprising triphenylamine derivatives and WO3. New Journal of Chemistry 45: 5503-5508.

- Wan Z, Zeng J, Li H, Liu P, Deng W (2018) Multicolored, Low-Voltage-Driven, Flexible Organic Electrochromic Devices Based on Oligomers. Macromolecular Rapid Communications 39: 1700886.[crossref]

- Zeng J, Wan Z, Zhu M, Ai L, Liu P.et al. (2019) Flexible electrochromic energy-saving windows with fast switching and bistability based on a transparent solid-state electrolyte. Materials Chemistry Frontiers 3: 2514-2520.

- Zeng J, Zhang X, Zhu X, Liu P (2017) Synthesis and Electrochromic Properties of Star-Shaped Oligomers with Phenyl Cores. Chemistry – An Asian Journal 12: 2202-2206.[crossref]

- Zeng J, Li H, Wan Z, Ai L, Liu P, et al. (2019)Colorless-to-black electrochromic materials and solid-state devices with high optical contrast based on cross-linked Poly(4-vinyltriphenylamine) Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 195: 89-98.

- Zeng J, Wan Z, Li H, Liu P, Deng W (2018) Visible and near-infrared electrochromic properties of polymers based on triphenylamine derivatives with acceptor groups.Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 178: 223-233.

- Zeng J, Yang H, Zhong C, Rajan K, Sagar RUR, et al. (2021)Colorless-to-black electrochromic devices based on ambipolar electrochromic system consisting of cross-linked poly(4-vinyltriphenylamine) and tungsten trioxide with high optical contrast in visible and near-infrared regions. Chemical Engineering Journal 404: 126402.

- Zhu M, Zeng J, Li H, Zhang X, Liu P (2020) Multicolored and high contrast electrochromic devices based on viologen derivatives with various substituents. Synthetic Metals 270: 116579.

- Oh H, Seo DG, Yun TY, Kim CY, Moon HC (2017) Voltage-Tunable Multicolor, Sub-1.5 V, Flexible Electrochromic Devices Based on Ion Gels. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 9: 7658-7665.[crossref]

- Kim KW, Oh H, Bae JH, Kim H, Moon HC, et al. (2017) Electrostatic-Force-Assisted Dispensing Printing of Electrochromic Gels for Low-Voltage Displays. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 9: 18994-19000.

- Shah KW, Wang SX, Soo DX, Xu J (2019) Viologen-Based Electrochromic Materials: From Small Molecules, Polymers and Composites to Their Applications. Polymers[crossref]

- Xiao S, Zhang Y, Ma L, Zhao S, Wu N, et al. (2019) Easy-to-make sulfonatoalkyl viologen/sodium carboxymethylcellulose hydrogel-based electrochromic devices with high coloration efficiency, fast response and excellent cycling stability. Dyes and Pigments.

- Shi Y, Wang G, Chen Q, Zheng J, Xu C (2020) Electrochromism and electrochromic devices of new extended viologen derivatives with various substituent benzene. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 208: 110413.

- Shi Y, Liu J, Li M, Zheng J, Xu C (2018) Novel electrochromic-fluorescent bi-functional devices based on aromatic viologen derivates. Electrochimica Acta 285: 415-423.

- Qian Y, Yang H, Wang Y (2020) A novel bis(terpyridine) with π−conjugated phenyl viologen and its met allo- supramolecular polymers: Synthesis and electrochromism. Dyes and Pigments 176: 108251.

- Sydam R, Ghosh A, Deepa M (2015) Enhanced electrochromic write–erase efficiency of a device with a novel viologen: 1,1′-bis(2-(1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl)-4,4′-bipyridinium Organic Electronics 17: 33-43.

- Yu HF, Chen KI, Yeh MH, Ho KC (2019)Effect of trifluoromethyl substituents in benzyl-based viologen on the electrochromic performance: Optical contrast and stability. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 200: 110020.

- Zhu CR, Long JF, Tang Q, Gong CB, Fu XK (2018) Multi-colored electrochromic devices based on mixed mono- and bi-substituted 4,4′-bipyridine derivatives containing an ester group. Journal of Applied Electrochemistry 48: 1121-1129.

- Liu S, Huang ZJ, Li F, Zhang WJ, Zhu CR, et al. (2020) Star-shaped monosubstituted 2,6-diphenyl-4,4′-bipyridinium salts with good electrochromic switching stability. Synthetic Metals 262: 116330.