DOI: 10.31038/NRFSJ.2018113

Abstract

Consumer acceptance of natural or organic food products are a widely researched area due to its increasing importance to public health and economic/personal wellbeing. Their positive effects have been identified and introduced by several authors and studies, however, the hardest task is always to get reliable knowledge about consumer minds. Getting information about the key factors driving consumer decisions about natural products may help producers and authorities creating better products and increase the consumption of natural products. The presented study introduces a new methodology, a new science, which gives a straightforward workflow and easy-to-interpret results about consumer minds. This new science, called Mind Genomics, uses simple questions (silos) and answers (elements) to create theoretical situations (vignettes) which are rated by respondents recruited online. Three distinct clusters, or mind sets, were found, each having a special mind genome about natural food products. Mind-set C1 (It’s all about the food) responds to food, food freshness, and everyday low prices. Mind-set C1 is the largest mind-set, comprising more than half of the respondents (28 of 51), and shows the lowest additive constant (8). Mind-set C2 (It’s all about customer focus), is much smaller, about one fifth of the respondents. Mind-Set C3 (It’s about convenience and sales), is also much slower, 12 of the 51 respondents. This group does not really respond to strongly to the special attractions of organic products, whether that be a café which serves the store’s products, or the selection. Mind-Set C3 seems to respond most strongly to price and convenience, as if they are shoppers in a hurry. For them, just make it easy.

Keywords

Organic Food; Consumer Segmentation; Conjoint Analysis; Natural Food; Bimileap

Introduction

In the world of natural foods, personalized nutrition, and health, conversations around consumer packaged goods that focus only on the goods themselves are significantly lacking in context. The key concerns tend to focus on the impact on the individual using the product, the physical characteristic of the product, or, perhaps, the sensory characteristics that can be used for the purposes of messaging and sales. However, when researchers focus solely on the product itself, with little connection to the placement of these products within the store that sells them, or how they fit within the marketplace, significant opportunities are lost.

We know that the food trade is enormous – and good groceries make for big business. In most of the world, people buy food products from stores and either prepare the food themselves or purchase the food ready-to-serve. We also know that there are an increasing number of stores which feature ‘good food’ as the core of their business model. In the United States, for example, we have the very successful Whole Foods chain of stores, with a value high enough to warrant a $13.4B acquisition price when they were purchased by Amazon in 2017. The idea at the time of purchase was that the demand for healthy food was so great that only distribution chains like Amazon’s could bring Whole Foods fully to scale. Market expectations were that the power of Amazon’s global network would drive Whole Foods prices down to a level that made the products they carried (including their own ‘generic’ store-brand) more accessible to an even greater number of consumers. While prices have mostly stayed the same over the past year, the wider impact is that Whole Foods is now joined by an increasing number of other, larger natural foods chains in an ever-expanding market– including stores like Mrs. Green’s, Fresh Thyme, and Trader Joe’s – as they fight for the healthfully-focused consumer [1].

Added to this struggle for the grocery dollar in ‘whole’ and ‘health’ food stores, there is a growing interest in what has been called the ‘locavore’ movement – dedicated to local produce, focused on the aim of eating only what can be procured within a specific mile radius of one’s own home. This has resulted in both an expanded interest in the commodification of farmer’s markets and a growing collection of (both ‘real’ and pretentious) community-supported agricultural ventures (or CSAs). These kinds of specialized market interests were a concern among food systems devotees and food trend analysts for decades, but only since the beginning of the twenty-first century has the conversation entered the mainstream discussions about access to healthy foods as a global health concern. As organizations like the World Watch Institute [2], the distance our food travels is a concern of epic proportions – and what was once a niche market has taken up a much more significant aspect of the global conversation about food, leading more of us to question the assumptions that healthy food is truly healthy, and that food labeled as organic or natural is actually better for you, whether it comes right down the road from your local farmer, or not.

Even with these conversations in play on a much wider scale, researchers in the food industry, especially those focusing on the measurement of physical characteristics of food products (e.g., food scientist, food engineers) or those focusing on the biological consequences of such foods (e.g., nutritionists, physiologists), do not pay attention to the so-called ‘trade, ’ because it does not seem to be relevant to them. There is little mental linkage in the minds of these professionals between the stores where the foods are purchased, and the nature of the people or products that they study.

This study attempts to bridge the gap in one way, looking for the existence of different types of people (mind-sets) who would design a natural-products store. We focus on responses of a small group of respondents (51) to different combinations of descriptions of a natural-food store, with the aim of uncovering just what is important. We move away from food and nutrition, per se, and into the nature of where the food items are sold. In a sense, we bridge the gap between product and sales, focusing on where the sales occur.

Method

In order to understand what is important to the consumer with respect to a natural foods store, we used the method of conjoint measurement [3], which presents respondents with combinations of messages, vignettes, and instructs the respondents to rate each combination on a scale. Rather than having the respondent rate each message in the vignette, we force the respondent to integrate all the information, and assign a single number to the vignette. This approach more typically resembles what a consumer might see in the outside world, namely a combination of elements to which the consumer must respond with a single judgment [4].

Underlying the different combinations, the test stimuli, also called vignettes, lies an experimental design, which dictates the composition of the vignettes. That is, although to a respondent the combinations might seem to have been thrown together haphazardly, the reality is that the vignettes have been selected in such a way as to make sure that the different elements, the messages, appear in a statistically independent way. This statistical independence allows us to apply the method of OLS (Ordinary Least-Squares) regression, to the ratings, and from the OLS estimate the part-worth contribution of each of the elements in the vignette. The respondent may not be able to articulate the reason why she or he assigns a rating to the combination, and in fact may not be able to directly compare the elements in the vignette because they are of different types, but the OLS regression will immediately reveal the contribution.

Forcing the respondent to answer at an intuitive, ‘gut level,’ rather than allowing the respondent to edit the answers to be ‘politically correct’ is becoming an increasingly important benefit of conjoint measurement. With the ever-increasing focus on health, many respondents select the answer that they believe will please the interviewer. By mixing and matching the elements or messages in a vignette, the researcher defeats the respondent’s effort to be politically correct. Faced with 48 vignettes of 3-4 messages, the typical respondent soon stops trying to be politically correct, and simply answers in an intuitive, gut way, more typical of what happens when the respondent is faced with these types of combinations in a non-test situation.

Messages – The raw material

The conjoint approach used here, Mind Genomics [5-7], can be considered to be a set of questions and answers. The specific design comprises six questions which tell a story, shown in table 1. Each question generates six answers, for a total of 36 answers. The answers are short, single-minded thoughts.

Table 1 shows the six questions, and the six answers to each question. The answers or elements deal with a range of topics of the shopper experience, ranging from pricing to professionalism to customer-facing amenities and customer convenience. The key question will be which of these aspects, food versus the shopping experience, will be most important for a natural foods store, where the positioning up front is of a store which is a ‘Natural Supermarket’ (not further defined in the respondent instructions)

Table 1. The six questions which tell a story and the six answers (elements, messages) to each question.

|

Question A – How are the products priced?

|

|

A1

|

We have everyday low prices

|

|

A2

|

Weekly sales with extra discounts on popular items

|

|

A3

|

We offer a wide variety of items at competitive prices

|

|

A4

|

We always have what you’re looking for in stock

|

|

A5

|

We guarantee the lowest price or it’s free

|

|

A6

|

You can purchase gift cards as a gift for someone special in your life

|

|

Question B – What products are stocked, and how can consumers discover them?

|

|

B1

|

A wide range of fresh and high-quality products is available

|

|

B2

|

We restock frequently so we always have what you need

|

|

B3

|

We have both organic and non-organic products available

|

|

B4

|

Fresh produce is delivered daily

|

|

B5

|

Free food samples so you can try before you buy

|

|

B6

|

We have a fresh juice stand so you can be hydrated while you shop

|

|

Question C – What is special about the stores?

|

|

C1

|

We have many destinations throughout the country

|

|

C2

|

We’re always nearby and close to your home

|

|

C3

|

All of our stores are powered by solar energy

|

|

C4

|

Special carts for children and toddlers are available

|

|

C5

|

We have special entrances and carts for the disabled

|

|

C6

|

We’re open 24 hours a day and 7days a week

|

|

Question D – What are the features of the loyalty program?

|

|

D1

|

The membership to our rewards program is free

|

|

D2

|

We give exclusive discounts and coupons to members

|

|

D3

|

Points earned from shopping never expire

|

|

D4

|

Points can be used for store credit based on out points to dollar system

|

|

D5

|

We reward customers for using recyclable and non-plastic bags

|

|

D6

|

Monthly gifts are awarded based on how much you spent that month

|

|

Question E – What are the customer-facing amenities?

|

|

E1

|

Our staff is friendly and always ready to help

|

|

E2

|

Free delivery is available for your convenience

|

|

E3

|

We have an easy and simple return/exchange policy

|

|

E4

|

Free parking is available for our customers

|

|

E5

|

Our staff is updated in nutritional and health benefits of our products

|

|

E6

|

We have a café that serves dishes made fresh from our products

|

|

Question F – What makes the store professional?

|

|

F1

|

We support small businesses and local farms

|

|

F2

|

We have a high overall customer service rating

|

|

F3

|

We handle mistakes and recalls in a professional manner

|

|

F4

|

We are serious and efficient in our efforts to ensure quality and service to our customer

|

|

F5

|

We have always passed our health inspections with high marks

|

|

F6

|

We have been successful in the business for 50 years

|

Creating the Test Stimuli – Combinations of Answers

Mind Genomics uses a basic experimental design, i.e., a set of pre-defined combinations. For this particular study, the experimental design comprised 48 vignettes, each vignette specifying either four answers (36 of the 48) or three answers (12 of the 48), respectively. A single vignette is allowed at most one answer from a question, ensuring that a vignette could not present two mutually contradictory answers from the same question.

Each of the 51 respondents evaluated vignettes (viz., combinations) created by different permutations of the basic experimental design [8, 9]. That is, the same experimental design was used throughout but the specific vignettes changed. The mathematics remained the same. Across of the 51 different permuted experimental designs, each respondent evaluated every one of the 36 answers five times, against different background. In the end, for each respondent, every element appeared five times in the 48 vignettes, and was absent 43 times.

The strategy of permuting the experimental design ensures that the research covers a wide range of alternative vignettes (so-called space-filling), and that there need be no initial knowledge about the topic. In contrast, most conjoint studies of this type create a limited, fixed, number of vignettes. These vignettes are then tested by the respondents. The traditional methods cover very little of the available ‘space’ defined by the many vignettes, relying instead on the precise measurement of the limited number of vignettes that are created.

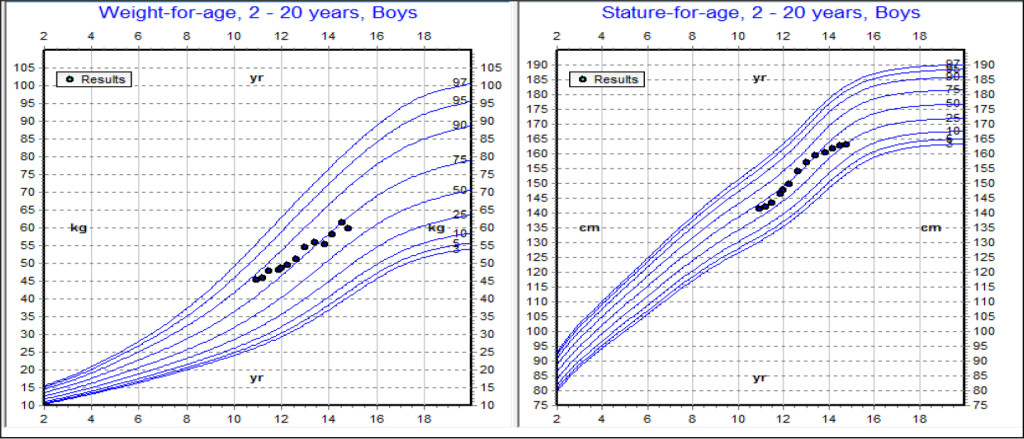

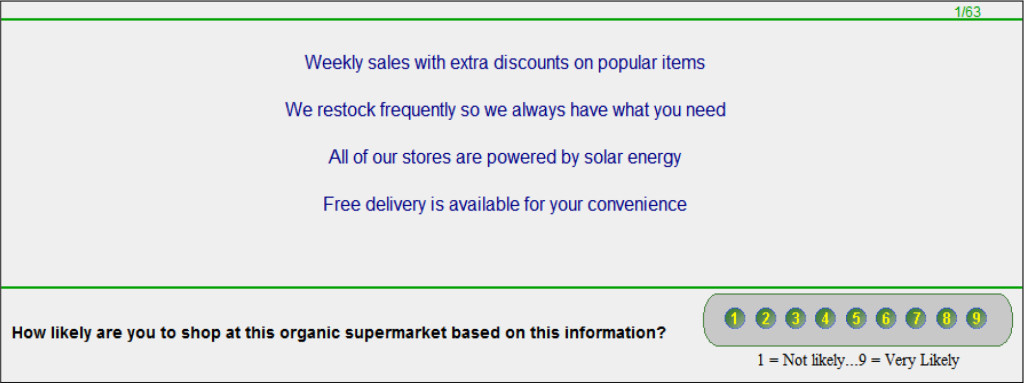

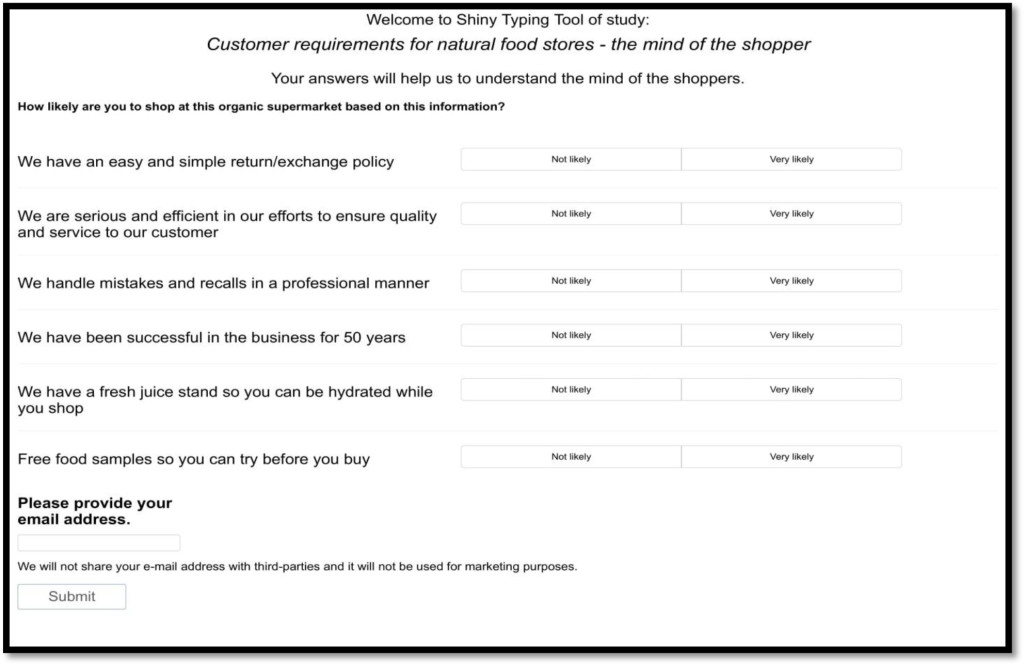

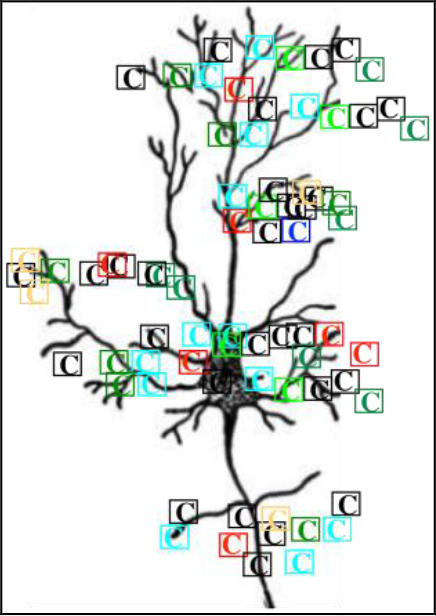

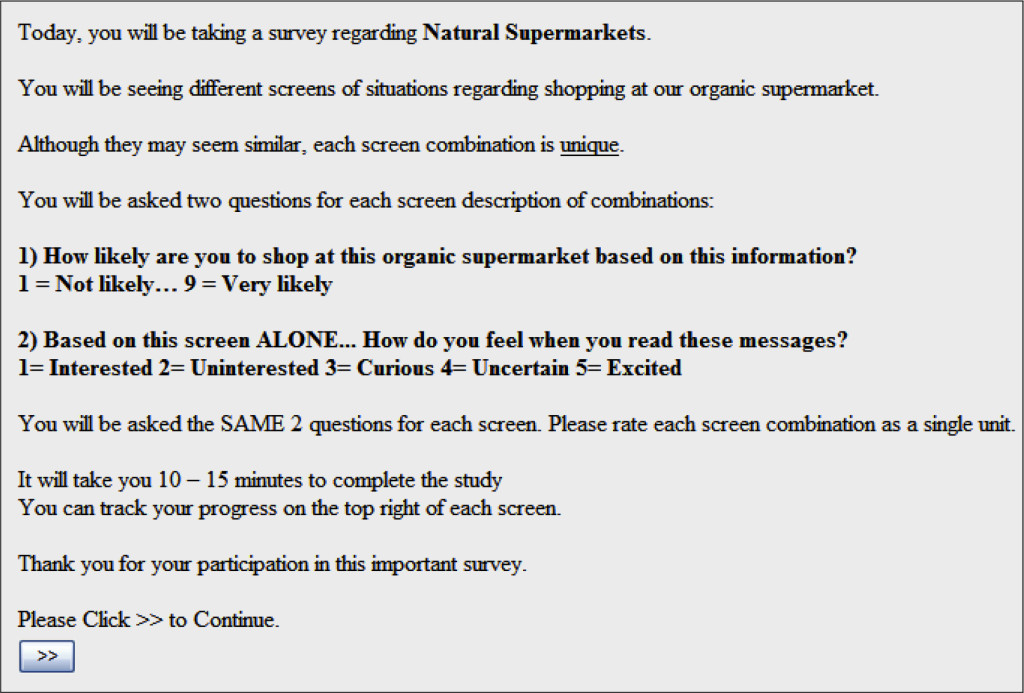

Figure 1 shows an example of a four-element vignette. In the Mind Genomics studies, no effort is made to connect the elements. The elements are presented as single rows of text, centered and double-spaced. This arrangement makes it easy for the respondent to scan the vignette, visually ‘grazing’ and picking up information that is relevant. Respondents exposed to these types of stimuli find it easy, and not onerous. In earlier efforts, none published; respondents were shown vignettes of these elements, but in paragraph form. The respondents found that format to be difficult, and daunting.

Figure 1. Shows an example of the vignette for a four-element vignette.

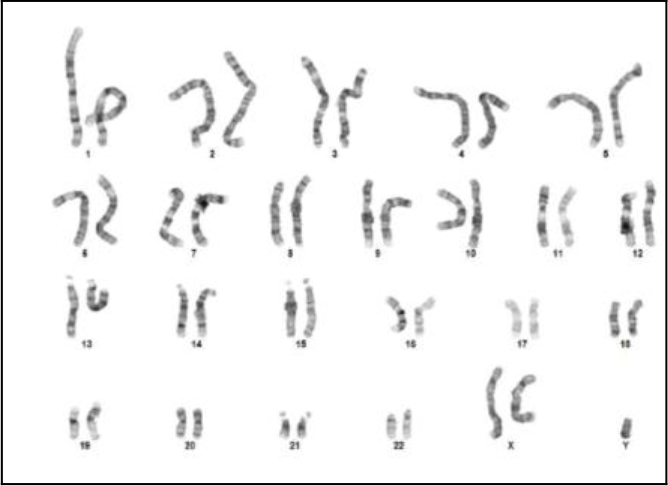

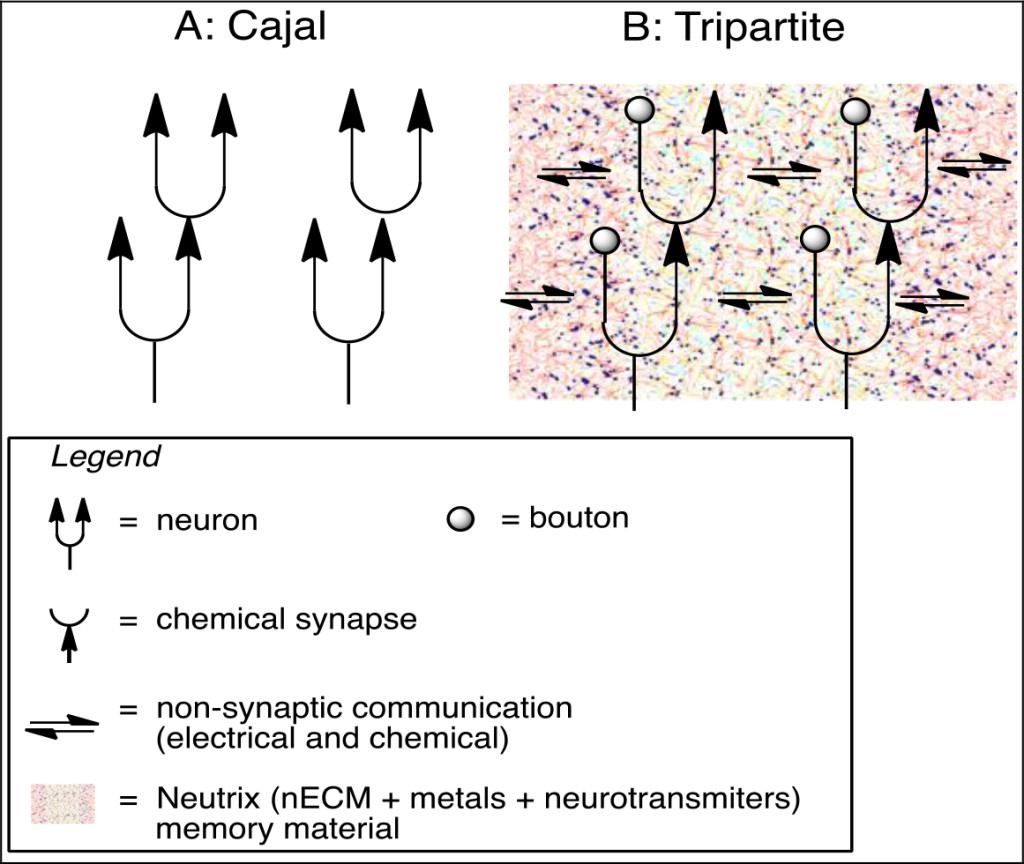

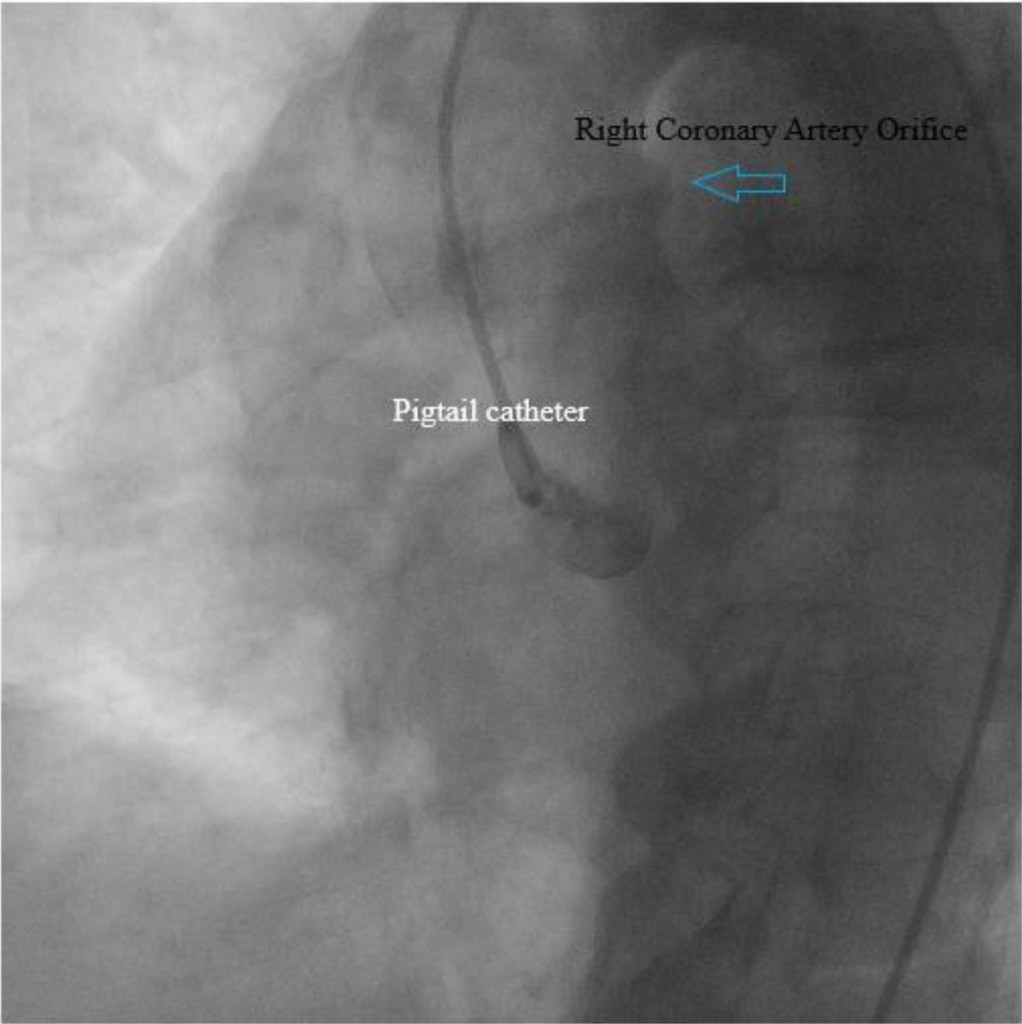

The vignette alone only provides information. It is the job of the researcher to focus the mind of the respondent on a specific issue. In this study the research focused on two issues. The first issue involves interest in shopping at the organic supermarket. The second issue involves the emotion that the respondent experiences. Emotions are becoming a key focus in consumer research [10, 11]. Mind Genomics deals with emotions by linking the emotions to the specific answers, the test messages. Figure 2 presents the two questions. The computer program constructed the vignette, and presented the respondent with the first question, likelihood to shop. The respondent answered the question. Immediately upon transmitting the rating, the Mind Genomics program changed the rating question but kept the vignette, allowing the respondent to rate the vignette on the second question, dealing with emotion.

Figure 2. The orientation page.

The Classification Questionnaire

At the end of the on-line interview, the respondent completed a self-profiling questionnaire, dealing with WHO the respondent is, and HOW the respondent shops. This data allows us to look at subgroups defined by how the respondents describe themselves. With 51 studies, the classification questionnaire revealed that most subgroups were too small to analyze by themselves, other than males versus females, complementary subgroups that we will consider below.

Running the Study

The respondents were recruited from Amazon Mechanical Turk [12] Mechanical Turk represents a ready pool of respondents, who act as test subjects. They represent a good source of respondents for Mind Genomics studies because the focus of these studies is the discovery of basic mind-sets in the population, linked to a specific topic. A good analogy is the discovery of color primaries, red, yellow, and blue, which can be done from most colored objects, where the objects are multi-colored. One does not need a so-called representative sample to discover these color primaries, although one does need a representative sample to determine the distribution of these color primaries in population of interest. The same logic applies to the ‘primaries’ or mind-sets to be uncovered by Mind Genomics. It suffices for a so-called convenience sample to uncover the nature of these primaries, but not to estimate their distribution in a target population.

The respondents who agreed to participate clicked on a link embedded in the email invitation, and were taken to the first page, the orientation page, shown in Figure 2. The orientation page shows only the name of the study, and then what is expected from the respondent. The important things to notice are:

- The only information provided about the topic is the name of the study. This paucity of information is deliberate because we want all the information about the natural supermarket to come from the vignettes that the respondents will evaluate. The words ‘natural supermarket’ is, however, included in every question, to remind the respondent about the context of the question.

- The orientation page provides the respondent information relevant to the process. One of the most important sentences in the orientation page concerns the fact that all the vignettes differ from each other. It is a natural thing for respondents to feel that they have ‘seen these vignettes’ before in the evaluation, since the same messages or elements repeat. The sentences assuage this response, often an irritated response.

- The orientation page then presents the two rating questions and the answers, but does not explain the meaning of the questions. The lack of explanation is deliberate, to prevent biasing the respondent by possibly leading with expected answers.

- The last section tells the respondent the expected time for the interview. This is an important piece of information. Respondents do not like interviews which last a long time. It is better for a respondent to drop immediately when the respondent knows that the interview time is 15 minutes. When the respondent moves through the interview and then drops in the middle, the result is a very disgruntled panelist, who is less likely to participate in the future, in any interview, no matter how short. Telling the respondent that the study will last 15 minutes is simply good research policy in terms of the ongoing relationship with the respondent.

Data Analysis and Results for Question 1 (Likelihood of Shopping)

The fundamental analysis in Mind Genomics is uncovering the relation between the set of the 36 answers, the independent variables, and the rating assigned by the respondent.

First, a Binary transformation is necessary: For each tested vignette, the 9-point rating is replaced by either 0 (ratings 1-6) or 100 (ratings 7-9). This binary transformation traces its heritage to the world of consumer research. Most researchers do not know what the points on the scale mean. The reality in consumer research is that the focus on a simple response, either ‘no’ or ‘yes.’ Managers understand that. The only issue afterwards is to identify the region of the scale corresponding to the ‘no, ’ and complementary region of the scale corresponding to the ‘yes.’ Historically, we have divided the scale into these two specific regions, although on occasion, for countries and respondents who use the upper part of the scale very frequently, the practice may be to divide the scale into two parts as follows: 1-7 transformed to 0, 8-9 transformed to 1. That is not the case here.

A small random number is added to each transformed rating, with the number around 10-5. This random number ensures that the subsequent analysis by regression will not ‘crash, ’ even when the respondent limits the ratings to the low portion of the scale, 1-6, or limits the ratings to the high portion of the scale, 7-9. The random number does not materially affect the results.

The statistical method of OLS (Ordinary Least-Squares) regression is used, which relates the presence/absence of the 36 elements (coded as 1 when present, coded as 0 when absent), to the binary rating. The OLS regression is done at the respondent by respondent level. The OLS regression always ‘runs’ because the experimental design ensures that the 36 answers or elements, our independent variables, are statistically independent of each other, and because adding the small random number to every binary value ensures that there is the requisite variation in the dependent variable.

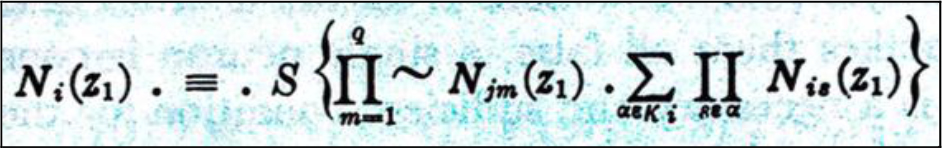

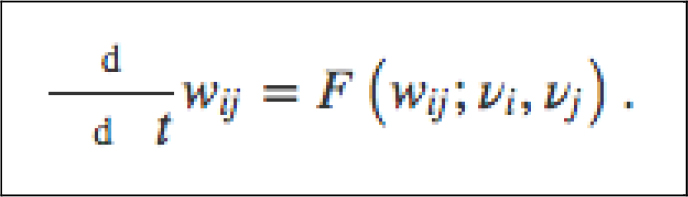

For each respondent an equation of the form:

Binary Value = k0 + k1(A1) + k2(A2) … k36(F6) is generated.

The corresponding parameters are averaged, either across the total panel, or across the relevant respondents, which for our study will be, respectively, gender (male vs female), and three mind-set segments emerging from the clustering.

Table 2 presents the results for the total panel, and for males versus females. The 36 answers, the independent variables, are sorted in descending order by total.

Table 2. Parameters of the additive model for Natural Supermarket, for Total Panel, and Gender (Male versus Female). The numbers of in the body of the table are the average coefficients from the relevant individuals that the model comprises.

|

|

Natural Supermarket

|

Total

|

Male

|

Female

|

|

Base Size

|

51

|

22

|

29

|

|

Additive constant

|

16

|

29

|

5

|

|

A5

|

We guarantee the lowest price or it’s free

|

34

|

39

|

29

|

|

B5

|

Free food samples so you can try before you buy

|

25

|

24

|

26

|

|

B6

|

We have a fresh juice stand so you can be hydrated while you shop

|

21

|

20

|

21

|

|

E6

|

We have a café that serves dishes made fresh from our products

|

19

|

14

|

23

|

|

A1

|

We have everyday low prices

|

18

|

12

|

22

|

|

B3

|

We have both organic and non-organic products available

|

17

|

14

|

20

|

|

B1

|

A wide range of fresh and high-quality products is available

|

17

|

6

|

25

|

|

B2

|

We restock frequently so we always have what you need

|

17

|

7

|

24

|

|

A4

|

We always have what you’re looking for in stock

|

15

|

11

|

18

|

|

C6

|

We’re open 24 hours a day and 7days a week

|

15

|

6

|

21

|

|

F6

|

We have been successful in the business for 50 years

|

14

|

8

|

20

|

|

E2

|

Free delivery is available for your convenience

|

14

|

13

|

15

|

|

F4

|

We are serious and efficient in our efforts to ensure quality and service to our customer

|

14

|

8

|

18

|

|

E1

|

Our staff is friendly and always ready to help

|

13

|

4

|

21

|

|

C3

|

All of our stores are powered by solar energy

|

13

|

8

|

17

|

|

D6

|

Monthly gifts are awarded based on how much you spent that month

|

12

|

6

|

17

|

|

A2

|

Weekly sales with extra discounts on popular items

|

11

|

7

|

13

|

|

F5

|

We have always passed our health inspections with high marks

|

11

|

6

|

14

|

|

F1

|

We support small businesses and local farms

|

10

|

2

|

17

|

|

F3

|

We handle mistakes and recalls in a professional manner

|

10

|

8

|

11

|

|

D3

|

Points earned from shopping never expire

|

9

|

5

|

11

|

|

C2

|

We’re always nearby and close to your home

|

8

|

7

|

9

|

|

E3

|

We have an easy and simple return/exchange policy

|

8

|

8

|

9

|

|

F2

|

We have a high overall customer service rating

|

8

|

-1

|

15

|

|

B4

|

Fresh produce is delivered daily

|

8

|

8

|

7

|

|

E4

|

Free parking is available for our customers

|

7

|

4

|

10

|

|

E5

|

Our staff is updated in nutritional and health benefits of our products

|

6

|

5

|

7

|

|

D2

|

We give exclusive discounts and coupons to members

|

6

|

12

|

2

|

|

A3

|

We offer a wide variety of items at competitive prices

|

6

|

-3

|

12

|

|

D5

|

We reward customers for using recyclable and non-plastic bags

|

4

|

5

|

4

|

|

D4

|

Points can be used for store credit based on out points to dollar system

|

4

|

2

|

6

|

|

A6

|

You can purchase gift cards as a gift for someone special in your life

|

3

|

-3

|

7

|

|

C5

|

We have special entrances and carts for the disabled

|

2

|

8

|

-3

|

|

C4

|

Special carts for children and toddlers are available

|

2

|

7

|

-2

|

|

D1

|

The membership to our rewards program is free

|

2

|

-1

|

4

|

|

C1

|

We have many destinations throughout the country

|

-4

|

-6

|

-2

|

The examination begins with the additive constant. The additive constant tells us the estimated percent of respondents who would rate a vignette 7-9 in the absence of elements, i.e., the 36 answers. Of course, all 48 vignettes comprised either three or four answers, by design. The additive constant is thus an estimated baseline. It is 16 for the total panel, meaning that only one out of six respondents might rate the basic idea of a natural supermarket 7-9. It is what the supermarket carries and does which makes the difference.

Continuing with the total panel, we see many of the answers or elements enjoying very high coefficients, several elements with coefficients of 15 or higher. Historically, these are extremely high, suggesting real interest in these features of the store. As we see below these very strong performers convey different types of messages, ranging from price to convenience to freshness. There is no single theme uniting the winning elements, but as we will see below, the themes emerge when we cluster the respondents on the basis of their response patterns. For right now, we need simply recognize that despite the low additive constant, it is the specifics which are important to drive interest in shopping. The simple notion of a natural market is not, by itself, compelling, and certainly not to women, as we will see.

We guarantee the lowest price or it’s free

Free food samples so you can try before you buy

We have a fresh juice stand so you can be hydrated while you shop

We have a café that serves dishes made fresh from our products

We have everyday low prices

We have both organic and non-organic products available

A wide range of fresh and high-quality products is available

We restock frequently so we always have what you need

We always have what you’re looking for in stock

We’re open 24 hours a day and 7 days a week

In many of these studies, we find few differences by gender, and the differences which emerge are minor. When we deal with the natural supermarket, however, we find dramatic differences between the genders, both in terms of the additive constant, and in terms of the particular answers or elements which perform well.

We begin our comparison with the additive constant. It is 5 for women, and 29 for men, a difference which tells us that for women there is no interest in the market without specification, whereas for the men there is some interest. Specification of the market features is far more important for women in order to interest them, and far less important for men. For women, the vignette which achieves a score off 70, for example, must comprise answers which add to 65 points, with the remaining 5 points contributed by the additive constant. Not so for men. The same score can be achieved by combining answers which add to 41 points, not 65.

Men and women show similar strong responses to two messages. The common message is ‘free’

We guarantee the lowest price or it’s free

Free food samples so you can try before you buy

One more element drives the men’s response. Women show a strong response to this element as well

We have a fresh juice stand so you can be hydrated while you shop

Women respond strongly to many more elements. There is no single theme among these very strong performing answers. The answers range from statements about price (we guarantee the lowest price or it’s free), to social consciousness (Our staff is friendly and always ready to help), to assortment (We always have what you’re looking for in stock), to ecology-minded (All of our stores ae powered by solar energy.)

We guarantee the lowest price or it’s free

Free food samples so you can try before you buy

A wide range of fresh and high-quality products is available

We restock frequently so we always have what you need

We have a café that serves dishes made fresh from our products

We have everyday low prices

We’re open 24 hours a day and 7days a week

Our staff is friendly and always ready to help

We have both organic and non-organic products available

We have been successful in the business for 50 years

We always have what you’re looking for in stock

We are serious and efficient in our efforts to ensure quality and service to our customer

All of our stores are powered by solar energy

Monthly gifts are awarded based on how much you spent that month

We support small businesses and local farms

Free delivery is available for your convenience

We have a high overall customer service rating

The patterns of coefficients differ dramatically across the genders. It’s not just that women begin with a lower additive constant, and show a constant increase in their coefficient versus the comparable coefficients emerging from the men’s data. Rather, the patterns are not correlated. What women find to be most important men may or may not find to be as important. The correlation between the two sets of 36 coefficients is only, lower than the correlation often observed when we compare the pattern of coefficients across genders.

Mind-Sets in the Population – The Contribution of Mind Genomics Thinking

We have seen that there are certainly differences among the elements based upon the data from the total panel, as well as substantial differences between genders on the same message. We also have seen that there is no single overriding description of what drives a strong positive coefficient. Rather, the data suggests a mélange of different answers, or different ideas.

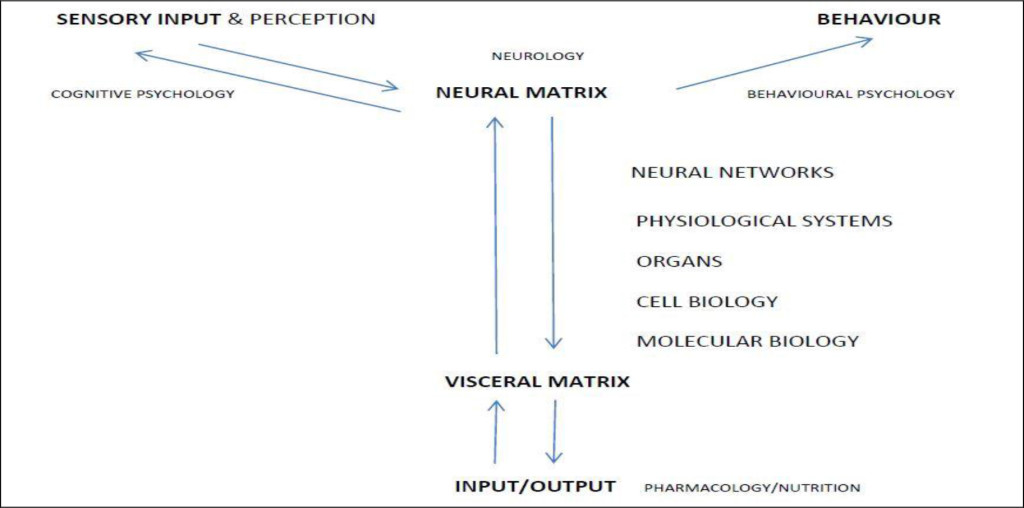

The premise of Mind Genomics is that within any aspect of human experience we can dimensionalize the experience to define different aspects, which we call ‘questions.’ The aspects or questions (also called silos) tell a story. The task of Mind Genomics research is to provide reasonable answers to those questions, and then determine the degree to which each ‘answer’ drives the rating, doing so at the level of the individual respondent. We have seen how this approach generates estimates of the contribution of each answer, when we look at the total panel, as well as males versus females.

Mind Genomics makes its major contribution by identifying different groups of people, clustered together by the way they respond to these answers. That is, Mind Genomics uncovers possibly hitherto-unexpected groups of people, similar in the way they respond to a situation, rather than considered to be similar by the pattern of WHO THEY ARE, or by the pattern of WHAT THEY DO, or WHAT THEY BELIEVE. In a sense, the metaphor we use is mental genomes and mental alleles. Mind Genomics creates a world of mental genomes, each mental genome comprising alternative ways of responding to the same elements, i.e., mental alleles.

The process to uncover these mental genomes follows well-accepted statistical methods, encompassed by the methods know as clustering [13], and specifically k-means clustering [14]. The Mind Genomics philosophy to uncover the aforementioned clusters or mind-sets is presented as follows.

An array of 36 coefficients emerging from the modeling is created. Each respondent generates an equation with an additive constant (not considered), and 36 coefficients, one coefficient corresponding to each answer or element.

A measure of distance between pairs of respondents is defined. Clustering algorithms use many different measures of distance. Our selection is the quantity (1-Pearson R). The Pearson R assesses the degree of a linear relation between two sets of observations. The Pearson correlation varies from a high of 1 when there is a perfect linear relation between the two sets of observations. This highest correlation, +1, corresponds to a perfect relation, and thus to a 0 distance between the two respondents (1 – 1 = 0.)

The full set of respondents (here 51)is divided into two groups, with the property that the variability within the group is small, and the variability across groups is large. There are specific mathematical criteria for establishing the best division.

The mean coefficients for each group, or cluster are examined (here also referred to as mind-set) to determine:

Interpretability: Do the clusters tell; a coherent story, or does it seem that there are too many different ‘stories’ which define the cluster. Interpretability is a subjective criterion, left up to the researcher.

Parsimony: The fewer the number of clusters, the “better” the segmentation. It is always desirable to have a simpler solution with fewer groups than a more complex solution with more groups. However, parsimony must be considered along with interpretability.

The results of this study suggested that two clusters generated an unclear segmentation. The clusters seemed too diffuse. A three-cluster solution seemed far better, as shown in table 3. We show the clusters, i.e., mind-sets, sorted by the winning elements of each cluster.

Table 3. Parameters of the additive model for Natural Supermarket, for Total Panel, and the three Mind-Set segments. The numbers of in the body of the table are the average coefficients from the relevant individuals that the model comprises

|

Natural Supermarket

|

Total

|

Mind-set C1

|

Mind-set C2

|

Mind-set C3

|

|

Base Size

|

51

|

28

|

11

|

12

|

|

Constant

|

16

|

8

|

13

|

35

|

|

We guarantee the lowest price or it’s free

|

34

|

35

|

32

|

33

|

|

Mind-set 1 – It’s about the food

|

|

|

|

|

|

Free food samples so you can try before you buy

|

25

|

43

|

-5

|

11

|

|

We have a fresh juice stand so you can be hydrated while you shop

|

21

|

34

|

1

|

7

|

|

We have everyday low prices

|

18

|

22

|

4

|

19

|

|

We have both organic and non-organic products available

|

17

|

20

|

16

|

11

|

|

A wide range of fresh and high-quality products is available

|

17

|

20

|

26

|

2

|

|

We restock frequently so we always have what you need

|

17

|

19

|

15

|

13

|

|

We have a café that serves dishes made fresh from our products

|

19

|

19

|

33

|

8

|

|

All of our stores are powered by solar energy

|

13

|

18

|

5

|

10

|

|

Mind-set 2 – It’s about trust and customer focus

|

|

|

|

|

|

We are serious and efficient in our efforts to ensure quality and service to our customer

|

14

|

4

|

49

|

5

|

|

We have been successful in the business for 50 years

|

14

|

11

|

46

|

-6

|

|

We handle mistakes and recalls in a professional manner

|

10

|

11

|

35

|

-16

|

|

We support small businesses and local farms

|

10

|

5

|

34

|

0

|

|

Our staff is friendly and always ready to help

|

13

|

10

|

33

|

2

|

|

Monthly gifts are awarded based on how much you spent that month

|

12

|

8

|

31

|

5

|

|

Points can be used for store credit based on out points to dollar system

|

4

|

-5

|

27

|

5

|

|

Free parking is available for our customers

|

7

|

4

|

20

|

2

|

|

Points earned from shopping never expire

|

9

|

6

|

17

|

7

|

|

We have a high overall customer service rating

|

8

|

2

|

16

|

14

|

|

We’re always nearby and close to your home

|

8

|

7

|

15

|

5

|

|

Fresh produce is delivered daily

|

8

|

13

|

15

|

-12

|

|

We reward customers for using recyclable and non-plastic bags

|

4

|

-1

|

15

|

8

|

|

Mind-set 3 – It’s about convenience and sales

|

|

|

|

|

|

We have an easy and simple return/exchange policy

|

8

|

-3

|

9

|

33

|

|

We always have what you’re looking for in stock

|

15

|

12

|

9

|

29

|

|

Free delivery is available for your convenience

|

14

|

14

|

3

|

26

|

|

We’re open 24 hours a day and 7days a week

|

15

|

13

|

8

|

24

|

|

Weekly sales with extra discounts on popular items

|

11

|

6

|

8

|

24

|

|

You can purchase gift cards as a gift for someone special in your life

|

3

|

4

|

-13

|

17

|

|

Not very strong for any group

|

|

|

|

|

|

Our staff is updated in nutritional and health benefits of our products

|

6

|

8

|

-2

|

10

|

|

We offer a wide variety of items at competitive prices

|

6

|

7

|

-2

|

8

|

|

We have always passed our health inspections with high marks

|

11

|

12

|

13

|

5

|

|

The membership to our rewards program is free

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

4

|

|

We give exclusive discounts and coupons to members

|

6

|

6

|

9

|

4

|

|

We have special entrances and carts for the disabled

|

2

|

3

|

-2

|

4

|

|

Special carts for children and toddlers are available

|

2

|

13

|

-24

|

0

|

|

We have many destinations throughout the country

|

-4

|

4

|

-21

|

-5

|

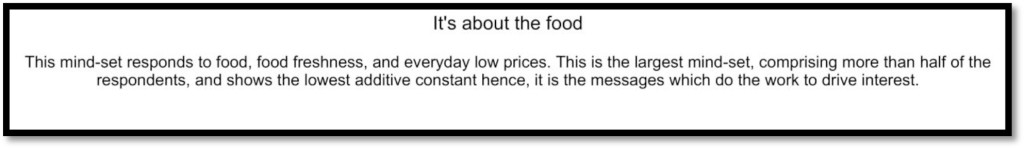

Before we look in detail at the three mind-sets, we should note that one answer does extremely well among all mind-sets, ‘We guarantee the lowest price or it’s free.’ We have pulled that out of the segmentation. Mind-set C1 (It’s all about the food) responds to food, food freshness, and everyday low prices. Mind-set C1 is the largest mind-set, comprising more than half of the respondents (28 of 51), and shows the lowest additive constant (8). For Mind-set C1, it is the messages which do the work to drive interest.

Wants everyday low prices

Excited by free food samples and juice stands

Likes a selection of both organic and non-organic products

Don’t care about rewards and point systems

Not concerned with special services

Mind-set C2 (It’s all about customer focus), is much smaller, about one fifth of the respondents. This segment also shows a low additive constant (8). The coefficients for this mind-set are exceptionally large, six in the 30’s and 40’s. Those coefficients are some of the largest ever observed in a Mind Genomics study. It is not clear about the degree to which the study taps into the ‘hot topic’ of natural and shopping.

Wants efficient service

Professionalism is very important

Not concerned with child accessibility

Don’t care about multiple locations

Not interested in buying gift cards

Prefers small business tactics over large companies

Mind-Set C3 (It’s about convenience and sales), is also much slower, 12 of the 51 respondents. The additive constant for this mind-set is much large, 35, so that they are similar to typical shoppers. This group does not really respond to strongly to the special attractions of organic products, whether that be a café which serves the store’s products, or the selection. Mind-Set C3 seems to respond most strongly to price and convenience, as if they are shoppers in a hurry. For them, just make it easy.

Wants a clear simple return/exchange policy

Product availability for low prices is very important

Prefers convenient store hours and delivery

Not interested how mistakes are handled

Not concerned with fresh produce

The segments are not correlated at all as:

Pearson correlation Mind-set C1-C2 = -0.04

Pearson correlation Mind-set C1-C3 = +0.16

Pearson correlation Mind-set C2-C3 = -0.18

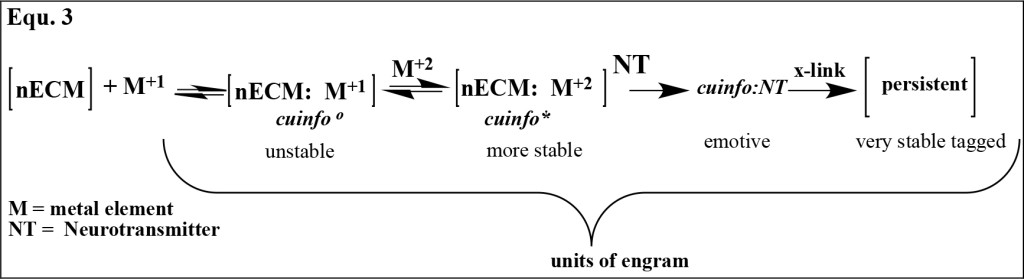

Linking Answers/Elements to Emotions

The experienced advertising professionals and consumer research professionals have recently discovered that beyond the messages themselves to which consumers respond, there are also emotions to be understood. Simply knowing that one of our answers appeals to a person, a gender, or a mind-set does not tell us the emotion which may be operating. Understanding the emotions and linking the emotions to the messages comprises one of the next big opportunities for sensory and consumer research.

Mind Genomics addresses the topic of emotion by instructing the respondent to select one of a limited number of feelings/emotions to describe the response to a vignette. Admittedly, the selection of 5-9 emotions is a limited number, compared the large number of emotions that have been enumerated in the literature [10, 11]. On the other hand, with 48 vignettes to evaluate, and the need to find a linkage between each emotion and each of the 36 answers/elements, it is prudent to reduce the number of feelings/emotions to a reasonable set. Five suffices to begin the process

Our objective here is to link each of the emotions to each of the messages. Following is presented our approach to establish the numerical value of the linkage.

Question 2 required the respondent to select one of the five emotions as appropriate for the particular vignette. A respondent had to select one of the emotions, and could not continue unless the selection was made. The five-point scale of emotion is not one of the typical numerical scales one encounters in research, but is an example of the so-called nominal scale, where each number corresponds to a (possibly) unrelated choice. There is no need for the five points to have any relation whatsoever. The single scale is expanded to five binary scales, one scale for each emotion. For the one emotion selected for the vignette, we put in the number ‘100’ plus a small random number (<10-5). For the four emotions not selected for the vignette, we put in the number ‘0’ plus a small random number.

All of the data are then combined into one file. The data comprises the 36 independent variables, the five dependent variables, across 2448 cases, one per vignette (48 vignettes x 51 respondents = 2448). OLS (ordinary least-squares) regression is used to estimate the coefficients of the equation below. Each of the 36 answers or elements is an independent variable, which generates a coefficient. The equation does not have an additive constant. The assumption is that without any elements there is no emotion selected.

Emotion Selected = k1(A1)+k2(A2)…k36(F6)

The coefficient shows the ‘linkage’ between the element and the selection of the emotion. Our norms suggest values around 10 as indicating a meaningful linkage.

Table 4 shows the elements sorted by linkage to the five emotions. For example, when we look at the feeling/emotion ‘curious’ we find the following strong linkages, and possible insights into the mind of the respondent that would not have emerged from the coefficients for interest (Question #1.) Although three of these seven answers/elements are the normal messages that a store might advertise (e.g., c, d, e), the other four are relatively unique.,

- Fresh produce is delivered daily

- We are serious and efficient in our efforts to ensure quality and service to our customer

- Our staff is friendly and always ready to help

- Free parking is available for our customers

- The membership to our rewards program is free

- We have a fresh juice stand so you can be hydrated while you shop

- We have a café that serves dishes made fresh from our products

Table 4. Likage of the five feelings/emotions to the 36 answers/elements. Linkages of 10 or higher are considered to be strong and relevant.

|

|

Interested

|

Uninterested

|

Curious

|

Uncertain

|

Excited

|

|

Interested

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A2

|

Weekly sales with extra discounts on popular items

|

13

|

4

|

3

|

3

|

4

|

|

B5

|

Free food samples so you can try before you buy

|

12

|

0

|

7

|

2

|

6

|

|

A1

|

We have everyday low prices

|

11

|

5

|

6

|

3

|

2

|

|

A5

|

We guarantee the lowest price or it’s free

|

11

|

-3

|

-3

|

8

|

16

|

|

D4

|

Points can be used for store credit based on out points to dollar system

|

11

|

2

|

10

|

3

|

1

|

|

A3

|

We offer a wide variety of items at competitive prices

|

10

|

6

|

5

|

4

|

4

|

|

C2

|

We’re always nearby and close to your home

|

10

|

6

|

3

|

4

|

2

|

|

Disinterested

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

C1

|

We have many destinations throughout the country

|

3

|

17

|

6

|

1

|

0

|

|

A6

|

You can purchase gift cards as a gift for someone special in your life

|

2

|

14

|

4

|

4

|

3

|

|

F3

|

We handle mistakes and recalls in a professional manner

|

3

|

13

|

3

|

8

|

1

|

|

C4

|

Special carts for children and toddlers are available

|

1

|

11

|

6

|

8

|

-1

|

|

Curious

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

B4

|

Fresh produce is delivered daily

|

6

|

2

|

16

|

2

|

0

|

|

F4

|

We are serious and efficient in our efforts to ensure quality and service to our customer

|

1

|

4

|

12

|

5

|

6

|

|

E1

|

Our staff is friendly and always ready to help

|

4

|

3

|

12

|

4

|

1

|

|

E4

|

Free parking is available for our customers

|

4

|

8

|

11

|

6

|

-2

|

|

D1

|

The membership to our rewards program is free

|

7

|

2

|

11

|

3

|

3

|

|

B6

|

We have a fresh juice stand so you can be hydrated while you shop

|

7

|

2

|

10

|

5

|

4

|

|

E6

|

We have a café that serves dishes made fresh from our products

|

3

|

0

|

10

|

5

|

7

|

|

Excited

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

E2

|

Free delivery is available for your convenience

|

1

|

0

|

8

|

5

|

11

|

|

C6

|

We’re open 24 hours a day and 7days a week

|

8

|

0

|

2

|

5

|

10

|

|

Answers not strongly linked to any emotion

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

D5

|

We reward customers for using recyclable and non-plastic bags

|

7

|

2

|

8

|

4

|

7

|

|

D6

|

Monthly gifts are awarded based on how much you spent that month

|

8

|

2

|

4

|

6

|

7

|

|

B3

|

We have both organic and non-organic products available

|

3

|

8

|

7

|

4

|

6

|

|

F1

|

We support small businesses and local farms

|

3

|

5

|

9

|

5

|

5

|

|

B2

|

We restock frequently so we always have what you need

|

6

|

4

|

7

|

5

|

5

|

|

E3

|

We have an easy and simple return/exchange policy

|

5

|

4

|

7

|

4

|

5

|

|

D3

|

Points earned from shopping never expire

|

9

|

3

|

7

|

2

|

5

|

|

C3

|

All of our stores are powered by solar energy

|

7

|

4

|

9

|

3

|

4

|

|

A4

|

We always have what you’re looking for in stock

|

7

|

1

|

8

|

6

|

4

|

|

F5

|

We have always passed our health inspections with high marks

|

8

|

8

|

4

|

3

|

4

|

|

B1

|

A wide range of fresh and high-quality products is available

|

7

|

5

|

8

|

4

|

3

|

|

D2

|

We give exclusive discounts and coupons to members

|

7

|

5

|

7

|

4

|

3

|

|

F2

|

We have a high overall customer service rating

|

9

|

8

|

3

|

5

|

3

|

|

F6

|

We have been successful in the business for 50 years

|

7

|

6

|

2

|

8

|

2

|

|

E5

|

Our staff is updated in nutritional and health benefits of our products

|

3

|

5

|

9

|

5

|

1

|

|

C5

|

We have special entrances and carts for the disabled

|

6

|

9

|

4

|

6

|

0

|

Further Use of the Obtained Knowledge

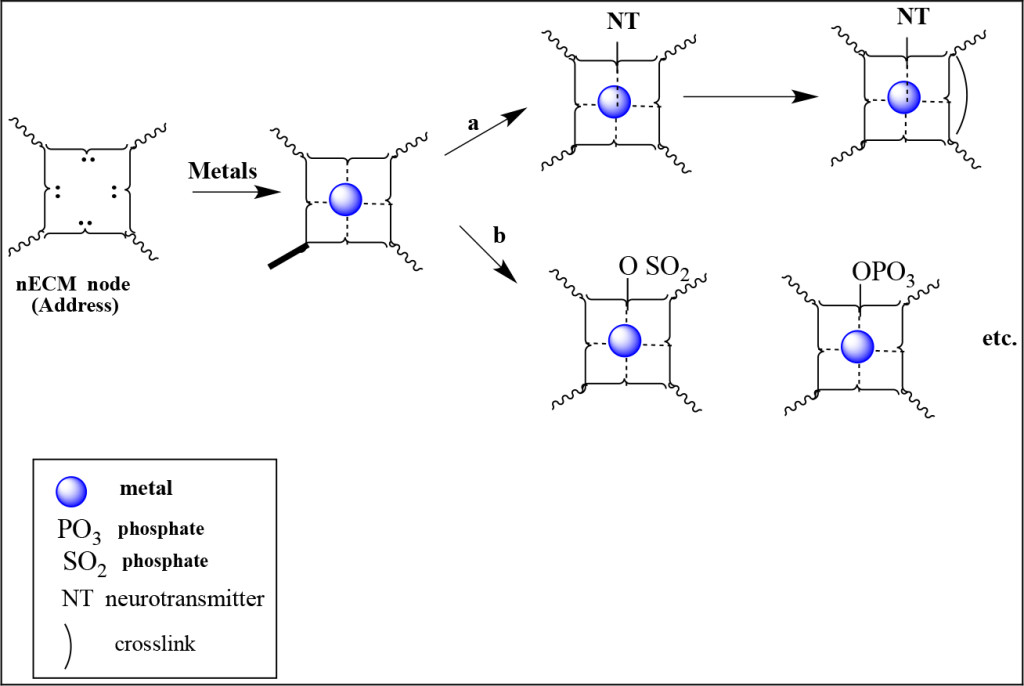

Similarly to many scientific fields, results of Mind Genomics studies are also ready to be used as the input data of prediction models. Prediction models are generally used in every scientific area to forecast unknown qualitative or quantitative information from some measured variables using a predefined model. In our case, the raw data of the presented study gives two important information:

- The coefficients of the respondents

- The known memberships of the respondents

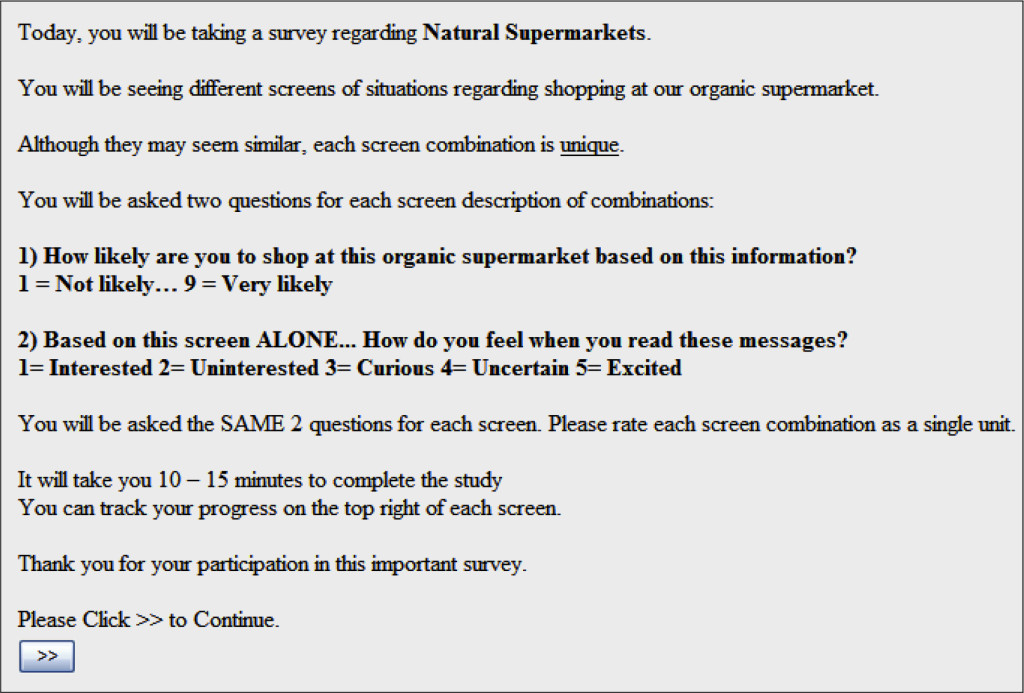

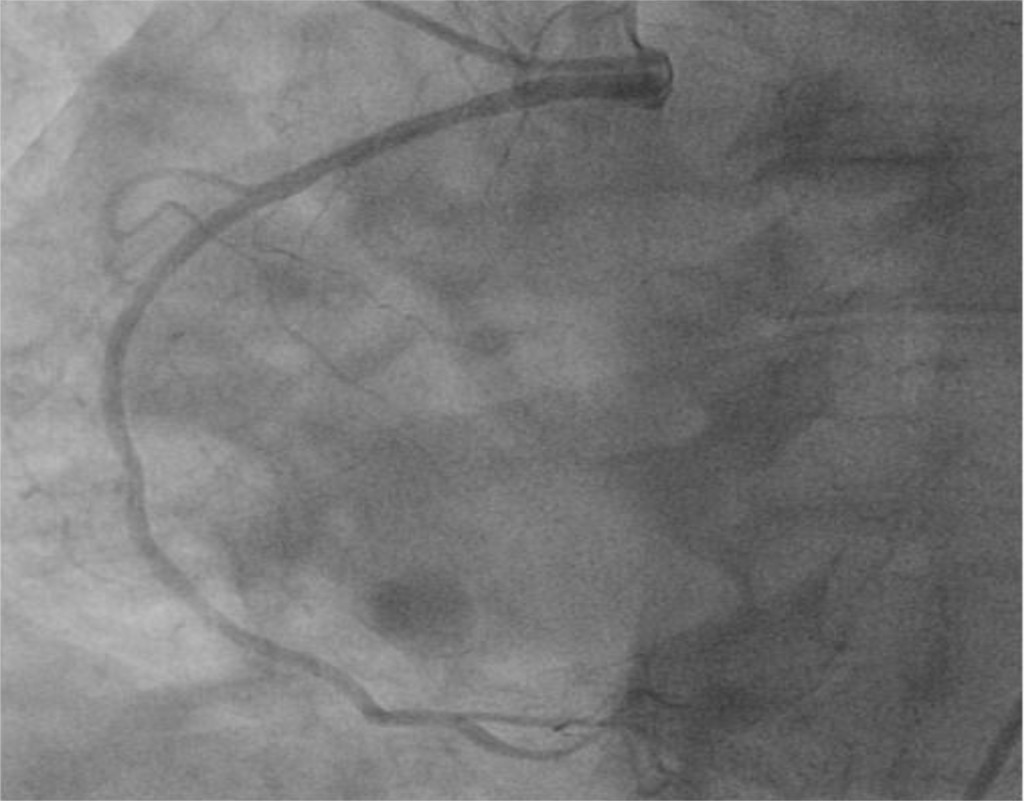

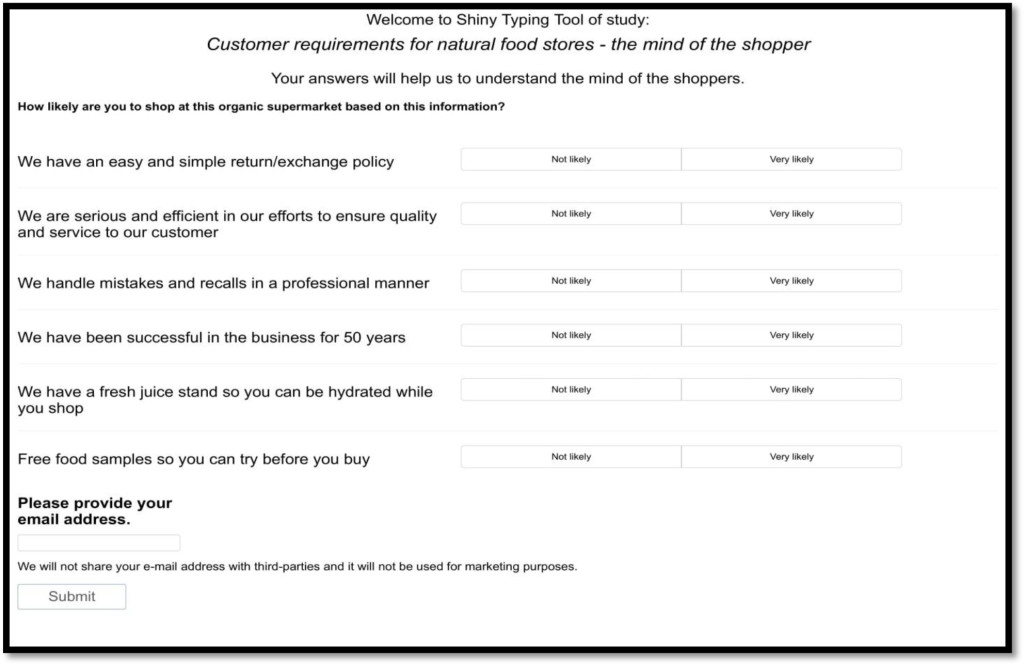

These information enables us to create so-called classification models which need continuous data to classify (or predict) the segment membership of the participants. The presented data is used for model training, e.g. to create the classification model. This classification model defines the 6 most important elements, which differentiate the segments the most. The 6 key elements are defined by so-called distance measures and the highest between-group distances are calculated. The obtained 6 key elements are then collected and ordered under each other on a newly created webpage (Figure 3). New participants, who never took part in this test before, then are asked to answer one question about the six elements using a binary scale with tow endpoints named “not likely” and “very likely”. The obtained answers are then passed to the classification model which is able to predict the most likely segment membership of this new participant.

Figure 3. Personal viewpoint identification opening screen. Participants are forced to answer each six questions and need to add their e-mail addresses before submitting their answers.

Here, the personal viewpoint identification process can be divided. In our case, we use the segment membership as information presented to the respondent (Figure 4). However, the segment memberships can be also used to suggest personalized products, advertisements or services. Possible usage of this information is almost endless due to the vast opportunities of the World Wide Web.

Figure 4. Result screen of personal viewpoint identification. In this example, the segment membership (It’s all about the food) and a small description of it are presented to the participants.

Discussion and Conclusion

As we consider the results of this study, it’s clear that consumers place a premium value on price, which has been identified by other authors [15]. All factors being equal, freshness will be sacrificed for price – convenience will be sacrificed for price – and features like universal access, customer convenience, and even positive aspects of store service will be sacrificed for price. However, it has been shown that consumers usually prefer local food or food originated from a geographically closer country [16], our study raises the attention to the significant effect of price; hence our results are not surprising. It would be reasonable to expect that economic drivers would be a high priority, if not the highest priority, for a consumer. However, it’s the factors that came in under price that create the greatest opportunity for exploration. If price is equal – or at least comparable – then what consumers want is freshness, convenience, and rewards for consumer loyalty. A new study from Istanbul, Turkey reports that retailer innovativeness and perceived food healthiness positively affect both store prestige and store trust [17]. In a market, then, where stores like Whole Foods offer a nationally recognized brand, a wider distribution channel, and a sense of convenience (online ordering, consistency from store to store, and loyalty programs), those who are dedicated to healthful eating will likely look first for the best “deal” first – and then for other factors like freshness and national brand recognition, even if they are more inclined to tell others that they seek quality first.

For the same reason, CSAs and farmer’s markets exist more in the mindset of consumers as an opportunity that serves either a quaint or exotic space than they serve as legitimate competitors to groceries that offer healthful or local foods. Simply put, if a consumer can get their groceries (including reasonably healthful foods) in the same location as their other household supplies, they will choose first by overall pricing and value, even if that means foods that aren’t quite as fresh, or stores that aren’t specifically known for having a national presence.

The presented methodology is suitable to scale up the presented results. A newly developing app, called BimiLeap (needs a reference or a link !!), aims to bring the presented research methodology to every mobile phone user all around the world. Using BimiLeap, users will be able to create a series of studies all dealing with organic food acceptance. By collecting the results of numerous studies dealing with organic products, mapping of consumer minds about organic food products will be available in a short time.

Acknowledgement

AG thanks the support of Premium Postdoctoral Research Program of Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

References

- Bustillos B, Sharkey JR, Anding J, McIntosh A (2009) Availability of more healthful food alternatives in traditional, convenience, and nontraditional types of food stores in two rural Texas counties. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 109: 883–889.

- Halweil B (2002) Home grown: The case for local food in a global market. (T. Prugh, Ed.). Washington D.C.: Worldwatch Institute.

- Green PE, Srinivasan V (1990) Conjoint Analysis in Marketing: New Developments with Implications for Research and Practice. Journal of Marketing 54: 3-19.

- Gofman A, Moskowitz H (2010) Isomorphic Permuted Experimental Designs and their Application in Conjoint Analysis. Journal of Sensory Studies 25: 127-145.

- Milutinovic V, Salom J (2016) Mind Genomics – A Guide to Data-Driven Marketing Strategy. Springer International Publishing.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A, Itty B, Katz R, Manchaiah M, Ma Z (2001) Rapid, inexpensive, actionable concept generation and optimization: the use and promise of self-authoring conjoint analysis for the food service industry. Food Service Technology 1: 149-167.

- Porretta S, Gere A, Radványi D, Moskowitz H (2018) Mind Genomics (Conjoint Analysis): The new concept research in the analysis of consumer behaviour and choice. Trends in Food Science and Technology, in press.

- Bell GH, Ledolter J, Swersey AJ (2006) Experimental design on the front lines of marketing: Testing new ideas to increase direct mail sales. International Journal of Research in Marketing 23: 309-319.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A, Beckley J, Ashman H (2006) Founding a New Science: Mind Genomics. Journal of Sensory Studies 21: 266-307.

- King SC, Meiselman HL (2010) Development of a method to measure consumer emotions associated with foods. Food Quality and Preference 21: 168-177.

- King SC, Meiselman HL, Carr BT (2013) Measuring emotions associated with foods: Important elements of questionnaire and test design. Food Quality and Preference, 28: 8-16.

- Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling SD (2011) Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A New Source of Inexpensive, Yet High-Quality, Data? Perspect Psychol Sci 6: 3-5. [crossref]

- Likas A, Vlassis N, Verbeek JJ (2003) The global k-means clustering algorithm. Pattern Recognition 36: 451-461.

- Mucherino A, Papajorgji P, Pardalos PM (2009) A survey of data mining techniques applied to agriculture. Operational Research 9: 121-140.

- Janssen M (2018) Determinants of organic food purchases: Evidence from household panel data. Food Quality and Preference 68: 19-28.

- Pedersen S, Aschemann-Witzel J, Thøgersen J (2018) Consumers’ evaluation of imported organic food products: The role of geographical distance. Appetite 130: 134-145.

- Konuk FA (2018) The impact of retailer innovativeness and food healthiness on store prestige, store trust and store loyalty. Food Research International.