DOI: 10.31038/JMG.2018113

Abstract

As a sessile organism, many plants have resolved to improve on strategies focused on detecting and resisting many types of stress. Understanding of these strategies and how to add them to sensitive plants have become a necessity in a world with more disadvantage conditions like: extreme temperatures, nutrients starvation, plagues and diseases. The capability of manipulate, enhance, in some cases retard or abolish these processes could help to improves cultivar production. Many plants of Brassicaceae family are some of most important crops worldwide, including Brassica oleracea, B. napus and B. juncea. Currently the genome is sequence and is freely accessible. This is one of many advantages in that molecular marker specific for this species. Moreover, the easy cultivation and accessibility worldwide, as well as the size and life cycle make this species good models to study stress and cell death. Several studies of tolerance and response to different types of stress and cell death have been carried out in many species from this genus. Therefore, some data is accumulating on several pathways.

Keywords

brassica, stress, cell death, apoptosis, stress tolerance

Introduction

As a sessile organism plants take advantage of different strategies that are focused on detecting and resisting many types of stress. Understanding of these strategies has become necessary due to increasingly disadvantage conditions: extreme temperatures, nutrients starvation, plagues and diseases. The capability to manipulate, enhance, overtake or in some cases retard or abolish these processes could help to improves cultivar production. Cell death is a consequence of either cell stress or involved in the lifecycle of the organism, and there is a close relationship of these two events. Moreover, the possibility of manipulating cell death in crops can be a way in which tolerance to crop stress can be improved or even accelerate or delay their maturation.

Brassicaceae family members are some of most important crops worldwide and have become a good model for study of different aspects of plant biology specially stress and cell death. Thanks to new powerful techniques such as proteomics and metabolomics, and a major number of complete genomes publication, it is possible to deepen in particular molecules related with stress and cell death or view a wide perspective of complex events.

1. Stress and cell death (RCD)

All organisms, including plants, are constantly suffering from changing environmental conditions and pathogen attacks which alters cellular homeostasis, causing damage in membranes and proteins structures, in first instance plants sense stress and producing and activating signal transduction pathways, this activates different mechanism under transcription control and try to repair damages [1]. Due to its condition as sessile organisms, plants develop multiple strategies to sense and contend against multiple stresses at the same time [2, 3]. They synthesize various molecules as proteins, amino acids (aa), carbohydrates and phospholipids to initiate an adaptive process to maintain homeostasis [1, 4, 5].

Now is clear that plant stress response is an interconnected network, which facilitates and produces an efficient and fast defense against environmental and biotic menaces and it is mediated by plant hormones and reactive oxygen species (ROS) that are detected through the plant [4, 6, 7]

Stress triggers a higher production of ROS which acts as a signal for the activation of stress response pathways, but when these defense mechanisms are not enough, the stress can result in cell death. Two mutually exclusive models are proposed to explain cell death triggers by stress. The conversion model involves the cessation of inhibitory signals of death after a homeostasis perturbation in a point in time and then it start to occur promoting signals, being the time briefer according to perturbation intensity. The competition model postulates that inhibitory and promoting signals coexist at the same time and the predomination of one of them depends of time and intensity of the perturbation and the successful of the adaptive response [8].

Cell death (CD) is part of the normal development and maturation cycles in living beings and part of many response patterns of tissues to external agents [9]. CD is necessary for plants and animals to develop correctly, for example; during metamorphosis of amphibians and insects, the morphogenesis of organs, and cell turnover required CD of certain cells in order for development to take place. In addition, the abnormal function of CD, as in an occurrence of multiple diseases, includes developmental disorders in plants and animals, as well as degenerative diseases and cancer in humans.

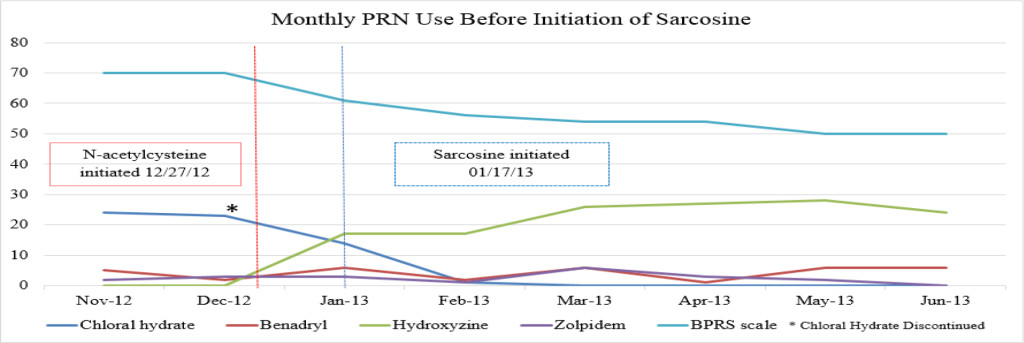

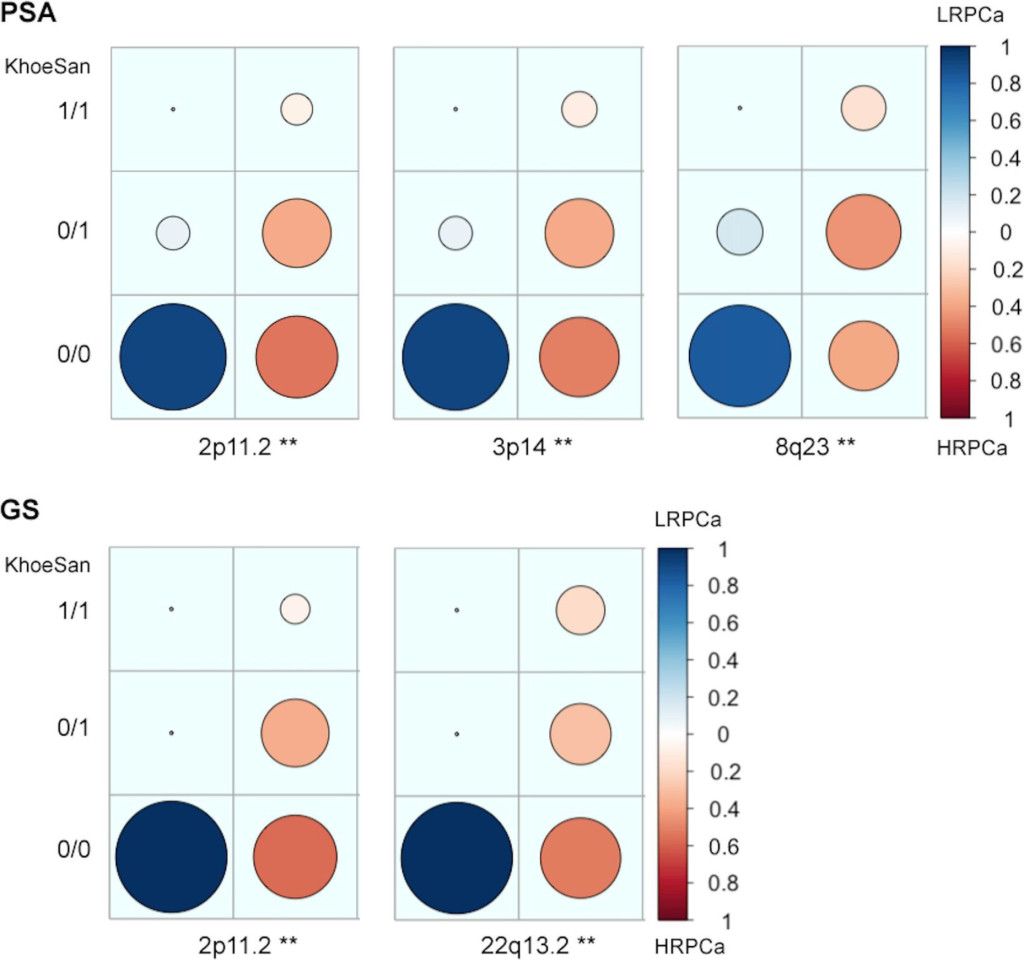

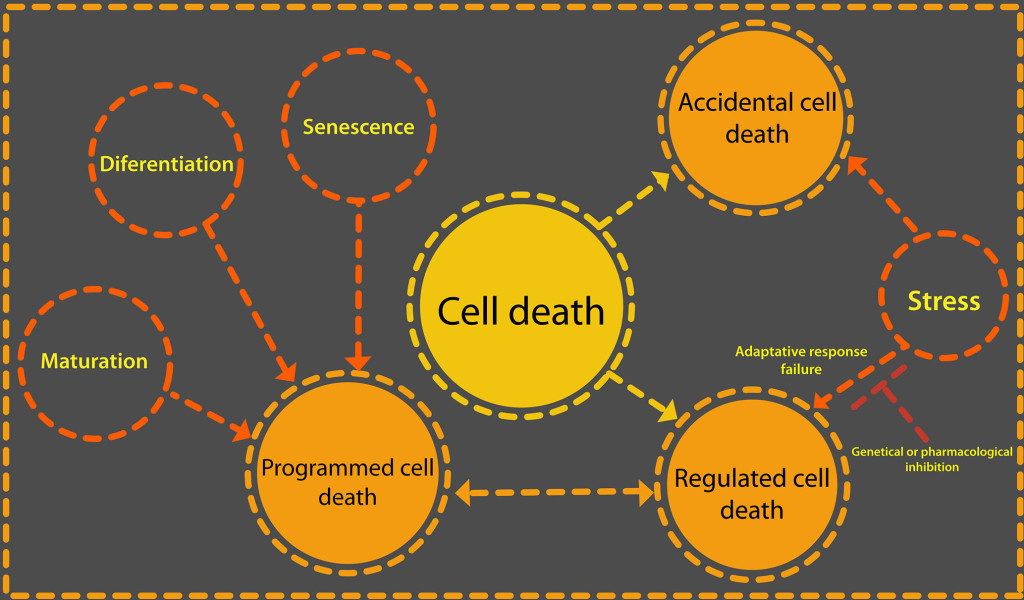

CD is classified as accidental cell death (ACD) and regulated cell death (RCD). RCD can be a programmed cell death (PCD) when it is part of the development cycle of an organism (see Figure 1). The ACD is a passive process that occurs when the intensity of a physical, chemical or mechanical stimulus is so great that cellular integrity deteriorates uncontrollably.

Figure 1. Cell death can be due to a failure of the adaptive response to a stimulus or be part of the normal development of an organism. There are two categories of cell death: accidental and regulated. What triggers one or the other is the intensity of an external stimulus or develop. When regulated cell death is part of the normal life cycle of a cell or tissue then it is a programmed cell death. Only regulated cell death could be delayed or stopped through iRNA or protein inhibitors such as Z-VAD-FMK, a caspase inhibitor.

RCD is active processes by which specific cells can pose a threat to a complete organism are eliminated. For this reason in the RCD, the molecular signaling pathways that govern the different forms of it are ordered and are strictly controlled [10].

RCD is caused by external stimuli, that is means stress, but with a lower intensity. In the first instance, the adaptive response of the organism tries to restore homeostasis, but when this cannot be achieved, specific genetic machinery is activated that directs this type of cell death, as long as the external stimulus is not excessive. RCD can be influence by specific pharmacological or genetic means [11]. By making use of specific inhibitors, such as iRNA, caspase inhibitors like Z-VAD-fmk or cyclosporin A and sanglifehrin A, for each particular manifestation of MCR, the events that control the death of the cells can be stopped or delayed.

Cell death can be part of a cell development program and it is then that we talk about PCD [8]. This term refers to the physiological cases of cell death that occur as part of the embryogenic or post embryogenic development in the formation of tissues and organs. Some of these organs and tissues are embryonic suspensors, xylem tracheary elements, roots and lateral roots [12]. PCD also occurs to maintain the homeostasis of a tissue, referring in this case to the balance between death and cell proliferation [12, 13].

2. Tools to the study of stress and cell death in brassica species

Currently there are many techniques to study a great variety of biological phenomena, including cell death and stress. These techniques let us learn about a single gene or molecule, including protein, lipids, and amino acids, among others or see a wide net of molecules interacting at the same time.

New bioinformatics software allows us to take advantage of the information from genes related with stress and cell death, such as BLAST and MEGA, which contains MUSCLE and CLUSTAL or RAxml to perform evolutionary studies between brassica species. Use proteomics, transcriptomic or metabolomics approaches to make new models or refine those that already exist, using bioinformatics tools such as Cutadapt, Trinity and N50 to perform transcriptomic, AMIX, SIMCA, METABOANALIZER for metabolomics and MASCOT, SEQUEST for proteomic analysis. Many databases are currently availables with invaluable information of the main brassica species: B. oleracea, B. rapa, B. napusand B juncea . In these data bases is possible to find molecular markers, genomes, expression sequence tags (EST), metabolic pathways and sequence specific searching tools as well as information about specific genes and the kind of evidence supplied (while bioinformatics level to protein level). This information gives us an excellent point of departure to start the study of specific molecules to look for interactors, novel functions, confirm the homology with others, discover specific mechanisms of each specie, define molecular markers of resistance that help breeders to select the best plants or possible targets of genetic enhancement.

3. Stress in brassica species

Abiotic stress and attacks pests and pathogens represent big challenge for agriculture, because plants spend a large part of their resources coping with these threats, decreasing their performance in the field. Current estimates indicate that arable land will be reduce by >50% for most major crop plants and current climate prediction models indicate that average surface temperatures will rise by 3–5 C in the next 50–100 years [3]. Although arabidopsis is the model, plant par excellence due to the large amount of mutants and wealth of genetic data available. However, many species of brassica used to study stress and CD process, especially in the study of heat stress, because of its sensitivity to heat e.g., temperature is one of the most important parameters for the development of the florets in B.oleracea. In some cases, heat stress benefits plant culture. In B napus microspore in vitro embryogenesis produced by the application of a treatment of 32°C for eight hours [14, 15] or an additional treatment of two hours to 41°C in late bicellular pollen to increase yield [16]. Coupled with this, HSP70 over expression and its nuclear translocation during heat treatments suggest which this protein is necessary for embryogenesis induction [17].

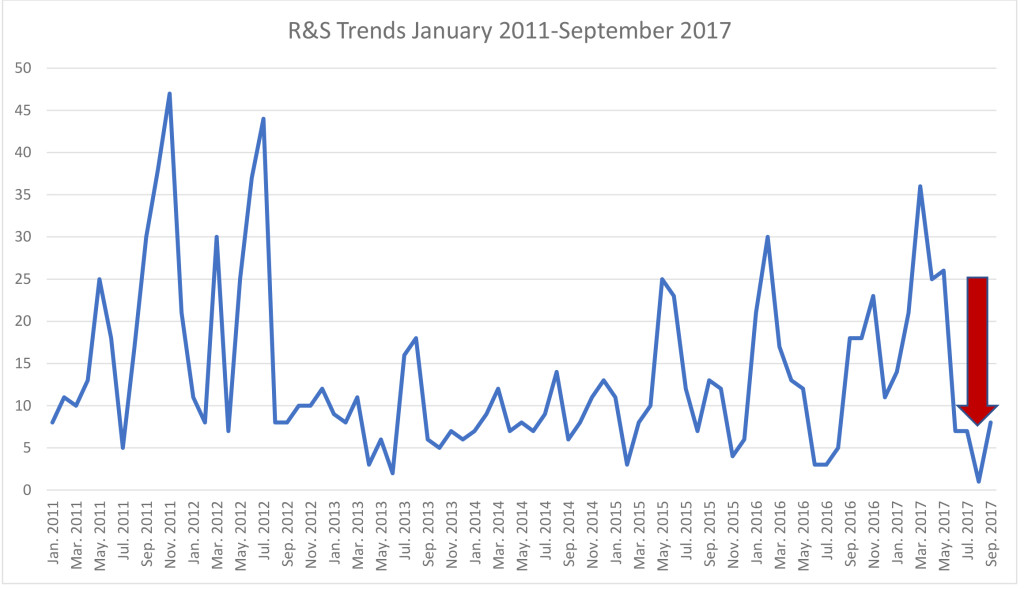

In most cases, heat stress reduce crops yield, causing morphological changes such as abnormal leave shapes due to changes in cell microtubules and microfilaments; injuring or killing plants. In B napus heat stress, reduce flower fertility. Under a treatment of four hours at 35 °C for one and two weeks after flowering ten days), experiments shows a similar number of flowers in control and the two stress periods (six thousand). However, the number of fruits shows a drastically reduction (50%) in one week of stress compared with control, following by a recovery. This recovery let to obtain similar number of fruit in both control and plants with one week of treatment (3.000 silique) and plants under two weeks of heat stress didn’t show recovery. The number of seed and fresh weight, in both stress conditions shows a reduction in 66% and 75% respectively with a light recovery after treatments in a 50% compared with control. At the same time germination reduced in stressed plants (germination rates of 17.5%) in contrast with control plants (germination rates of 59.2%) [18].

Other study shows that B. rapa and B. juncea are sensible too to heat stress, affecting the reproductive development and yield, showing which the first of them are the most sensitive [19]. Under a treatment of 35 oC, B. rapa and B. juncea, reproductive organs was injured, mainly resulted in the reduction of seeds in 80 and 40% respectively in early flowers. Inflorescences of B. oleracea var. italica (broccoli), presents reduction in flowering after a treatment of heat to 35 °C. Buds reduced its size in 50 to 75% in treated plants and the damage caused to buds is bigger in young inflorescences (straight stage) than mature (crown stage) [18].

Kale variety of B. oleracea seedlings under heat stress (32 oC) shows abnormal leave shape, presenting elongation of them and a reduction of fresh weight of a 30% percent, at the same time stomal conductance increase and its size was reduced due its heat stress susceptibility [20]. Due to global warming, high temperatures expected to become a limiting factor for production, so research on tolerance to heat stress will be of great importance [21, 22]. Plants have a higher number of transcription factors related to tolerance to heat stress, than those found in animal cells; this is probably due to the plants, unlike them; they are not able to move to another place to mitigate the high temperatures [23].

A way to know if stress response proteins also produced in brassicas shown by Fabijanski and colaborators. Comparing the differential expression of proteins in plants without and with stress using sulfur 35 (35S) and later comparing the differential proteins found with 1D and 2D gel electrophoresis, with those already known in other models such as tobacco. The typical proteins synthetized by plants in heat and other abiotic stresses are heat shock proteins (hsp) , maintaining proteins correct conformations and prevent the aggregation of non-native proteins [24]. Fourteen of these found in broccoli leaves. After a treatment of 37 oC, in the first two hours a presence of a differential protein expression compared with plants treated with 20 oC, mainly 90 KDa, 88 KDa, 86 KDa, 74 KDa, 69 KDa, 66 KDa, 47 KDa, 43 KDa, 42 KDa, 27 KDa, 23 KDa, 21 KDa, 19 KDa and 18 KDa. Molecular mass proteins. After two hours, there seems to be a reduction in their synthesis; however, this maintained for two hours after [25].

A similar way to give identity to a protein is to use antibodies that recognize homologous proteins already characterized to confirm, through the specific interaction of the antibody with the protein and the expression during the condition evaluated, in this case, stress, identity and participation of the protein in the condition. A study realized by Avice group answer the question if the 19-kD trypsin inhibitor (TI) protein related with the Water-soluble chlorophyll-binding protein (WSCP) BnD22 from B. napus previously detected in leaves.

Using young leaves during leaf nitrogen (N) starvation methyl jasmonate (MeJA) treatments and proteomic technique, this work confirmed the relation between both proteins. Partial sequences from two differential spots in stress and normal conditions, identified by Electrospray ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry (ESI-LC MS/MS) were identical to peptides previously identified by the same method and a search in databases revealed that both also presented 100% homology to BnD22. Prior to this, immunoblot analysis and image analysis software shows that BnD22 and 19-kD (TI) are two isoforms of the same protein, and BnD22is induced 12-fold by MeJA [26].

Proteomic approaches are also useful to find out novel proteins that plants expressed under stress. Following the same strategy, we used two contrasting conditions, but now with two broccoli cultivars, one heat-tolerant TSS-AVRDC-2 and one heat-susceptible B-75, under heat stress and waterlogging. Plants divided into four 20 °C without waterlogging (as control) 20 °C with waterlogging; 40 °C without waterlogging, and 40 °C with waterlogging. With this method, was identified 15 and 16 pivotal proteins in stress tolerance from TSS-AVRDC-2 and B-75 respectively, giving the work a deeper biological context also using physiological parameters such as chlorophyll content and stomal conductance in which the resistant cultivar was better [27]. By combining all the data, it explained that this resistance is due to a better metabolic behavior, in which the ROS levels produced controlled more efficiently.

Other species, such as B. juncea, B. napus, b. carinata and B. campestris, accustomed to tropical climates, studied to better understand the tolerance to stress by drought. Six parameters including water content, epicuticular wax, chlorophyll content, leaf water potential, osmotic potential and content of protein, authors comparing the stress tolerance of both species. B. napus was the one that best supports these conditions and B. carinata was the most sensitive. Although, all the four species decreases in most of parameters, B. napus presents a better production of biomass respect to the others. This behavior also occurs with respect to the chlorophyll content. For all species, except B. campestris, clhorophyl in control condiction was 3 fold higher than in stress treatments, for B campestris clori [28].

B. napus was used again to evaluate the synthesis of aa as a mechanism of drought stress tolerance. Since the increased of solutes to decreased osmotic potential and diminish water loss. This specie was exposed to dehydration to measure changes in the concentration of aa, with an overall increase of 5–9 folds during the four days of treatment. It was later observed that aa levels decreased almost to the initial levels prior to stress. Likewise, the use of radioactive labeled methionine with sulfur 35 (35S) results in an increase in protein synthesis observed on the second day of treatment, to later return to the first day levels. Finally, it was determined that the increase in the amount of aa was due to the synthesis of alanine, aspartate and asparagine precursors, pyruvate and glutamate and not to the enzymatic activity of alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase, two enzymes involved in aa synthesis [29].

3.1. PLC-Phosphoinositide pathway during stress response in Brassica

B. napus served as a model to study the signaling pathways activated in response to drought, salt and cold stress. A work mainly focused in phosphoinositide signaling pathway controlled by the enzyme phospholipase C (PLC) which hydrolyzes phosphatidylinositol (4,5) bisphosphate (PIP2) to generate diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol 1,3,5-trisphosphate (IP3) two second messengers in the cell [30] found the relationship between PLC and the tolerance to abiotic stress as well as the particular differences in each stress.

By cloning of the genes PLC-2, phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase (VPS34) and a phosphatidylinositol synthase (PtdInsS1), as well as relative expression of a phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase (PtdIns 4-K) and phosphatidylinositol -4-phosphate 5-kinase (PtdIns4P-5-K) shows which in cold stress the expression of PLC-2 increased, PtdInsS1 decreased and while the levels of the other genes remains without changes. Under salt stress expression of VPS34 increases, suggesting an important role for other phosphoinositide, phosphatidylinositol 3 phosphate PI(3)P in the tolerance of this stress, acting in an alternative pathway different from the PLC-2, however a slight increase of PLC-2 could be observed. In the same work, plant growth in drought stress exhibit a major number of transcripts of all evaluated genes [31].

B.napus used to evaluate the changes at the metabolic level produced by the overexpression of plc. Since PLC produces an increase in tolerance to abiotic stress, researchers runs a profile of various metabolites in cold stress. 12 metabolites presents significate changes, 9 increased, many of them aa, highlighting b-alanine (1.5 folds); there was also an increase in spermidine (2.5 fold) and a lipid, linoleate (1.66 fold). A very important change in sucrose levels, in which there was an almost 5-fold increase during stress. In plants that over expressed the enzyme could be seen a better recovery after stress. Also, since it is known that biotic and abiotic stress share some signaling pathways [3], using the fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum to test biotic tolerance, authors reports minor severity of symptoms in plants with enhanced expression of PLC-2, however this tolerance appears to be partial [32].

4. Cell death in Brassica species

RCD is divided morphologically into apoptosis, autophagic cell death and necrosis. Apoptosis for many years was considered synonymous with the RCD. During apoptosis occurs fragmentation of the nucleus and formation of apoptotic bodies, phagocytosis and degradation of these bodies by other cells [33].

Autophagic cell death is a mechanism conserved in eukaryotes by which organisms degrade and recycle cellular components [34]. The organelles are sequestered by double membrane vacuoles called autophagosomes and then degraded by various hydrolases [35].

Necrosis was considered for many years, synonymous with accidental cell death, since it was believed that there was no way to regulate it [9]. The necrosis is defined in negative terms, that is, all that death whose morphology does not correspond to autophagy or apoptosis is considered necrosis. However, there is generally a gain in cell volume (oncosis), swelling of the organelles, and the rupture of the plasma membrane results in a consequent loss of intracellular content [36, 37].

Cell death in plants is a phenomenon little studied if compared with animals, where, because of the importance of cell death in various types of cancer have been established more appropriate criteria for the classification and study of CD.

An attempt to establish a morphological classification proposes two categories: autolytic and non-autolytic cell death. The main difference between the two deaths is that in the autolytic death a rapid clearance of the tonoplast occurs, due to the degradation of cellular components through various hydrolases. Hydrolases are released into a large vacuole that occupies most of the volume of the cytoplasm and which is formed by vacuoles of smaller size (very similar to the autophagic cell death), until finally the tonoplast is broken. In non-autolytic type death, the clearance occurs after the tonoplast rupture [38, 39].

Brassica species it is a model widely used to study cell death processes. In several species of the genre, RCD studies were carried out induced by various abiotic stresses such as cold, mechanical or heavy metal stress.

B. oleracea was used to study regulated cell death. The expression of genes related to apoptotic cell death induced by post-harvest management (refrigeration) has been identified, for example, of proteins like serine palmitoyltransferases (BoSPT1) and proteins with caspase 3 activity (Cas3) [40, 41].

In B. napus similar nuclear fragmentation due to MCR was associated with recalcitrance to the regeneration of whole plants in protoplast cultures of B. napus leaves. The MCR induction was attributed to the stress caused by the protoplast isolation process [42].

The lack of iron in protoplast cultures of B. napus induced non-autolytic death. The lack of iron caused the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the activation of a protein with cas3 activity. Also condensation of chromatin and fragmentation of the nucleus was observed [43, 44].

Other cysteine-proteases (CysP) were related with similar observation in B. napus during PCD in seed development [45]. Northern blot analysis of temporal of the CysP, BnCysP1 in B. napus, shows the expression of said gene from the tenth to the sixteenth day after flowering and confirmed later by western blot. Not only that, but, the synthesis of BnCysP1 ocurs in the inner tegument during PCD confirmed by the observation of DNA degradation with a TUNEL assay [46].

In B. oleracea was also found that a CysP, BoCP5 was responsible for florets senescence [47]. In this work authors compared broccoli lines, wild type (wt) and transgenics, transformed with antisense construct for BoCP5under the control of a senescence-induced promoter. During harvest-induced senescence in broccoli floret BoCP5 is induced and synthetized 6 h after harvest. In wt line in which mRNA, protein and protease activity was detected in higher levels. Finally, three transgenic lines shows less florets senescence (more greener) than wt within 72 and 96 h after harvest.

It is very interesting to note that especially B. oleracea and B napus are excellent models to explore the molecular and biochemical similarities between the RCD in plants and animals. In addition they are also suitable models to perform with them different microscopy techniques to characterize biochemistry, molecular and morphologically the RCD in plants. For example, it is clear that different stresses cause morphological changes in the nucleus when the CD is produced. However, it must be studied if these changes are similar in terms of signaling pathways that activate to cause these changes.

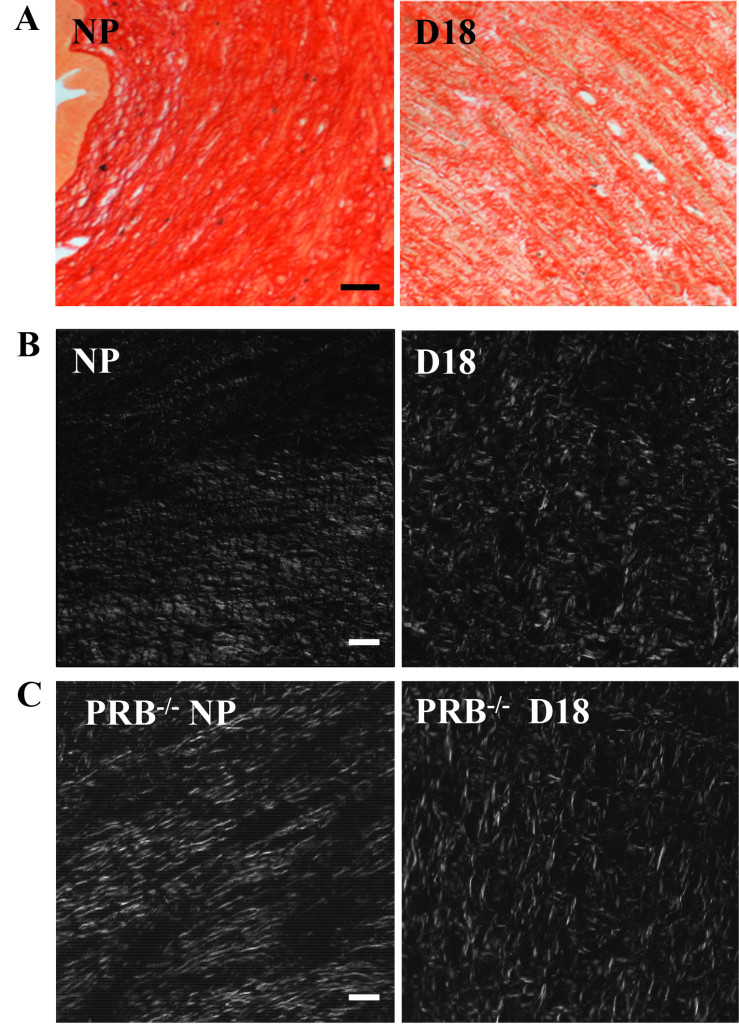

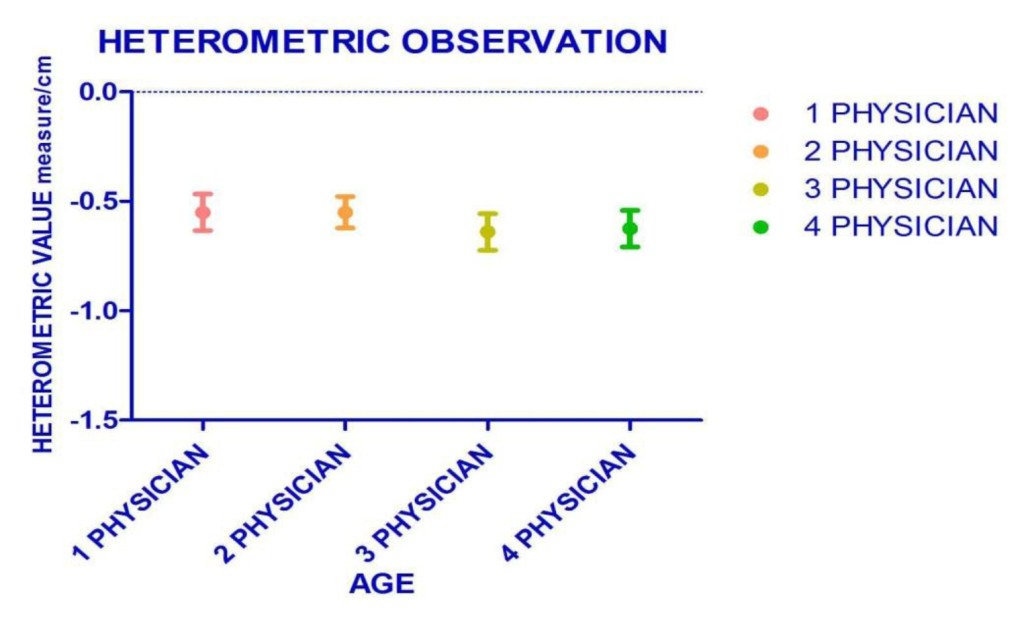

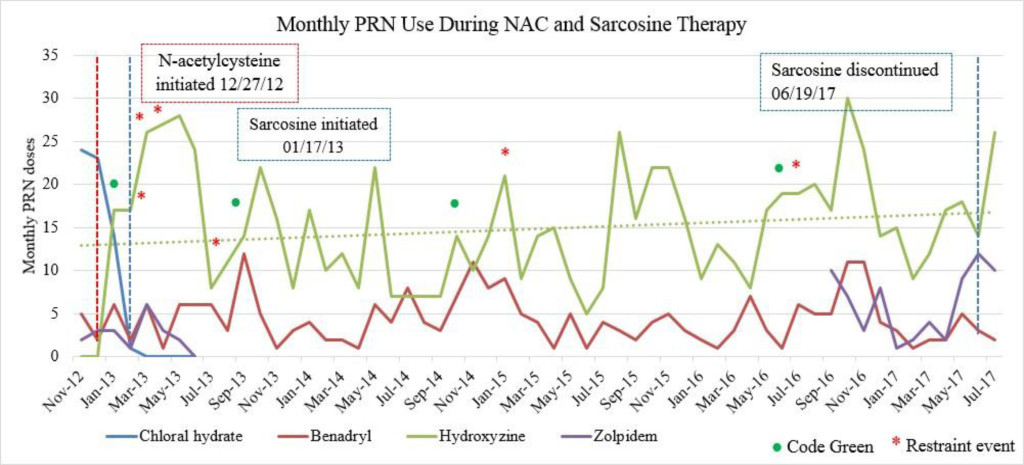

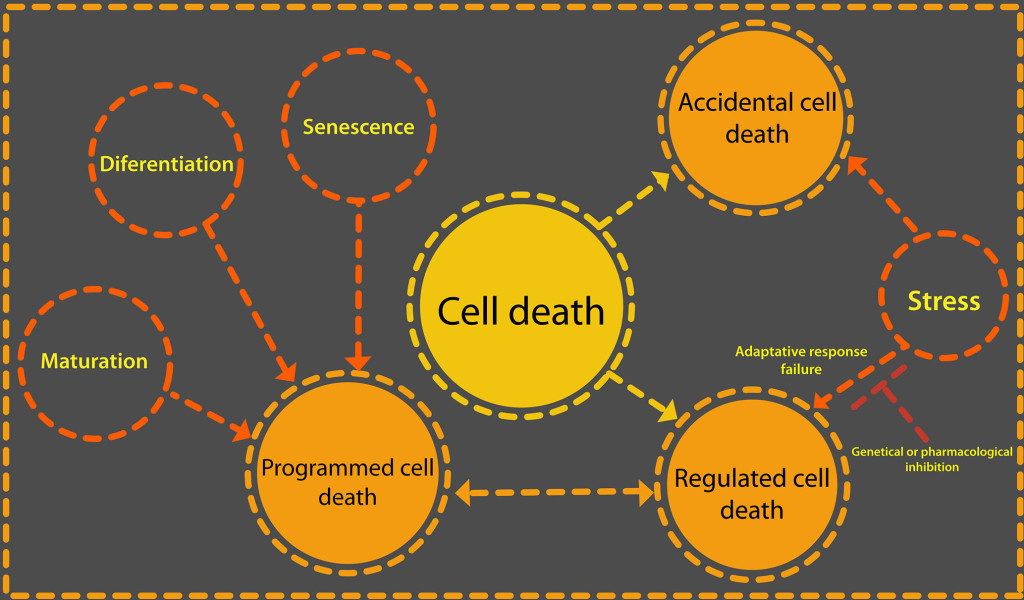

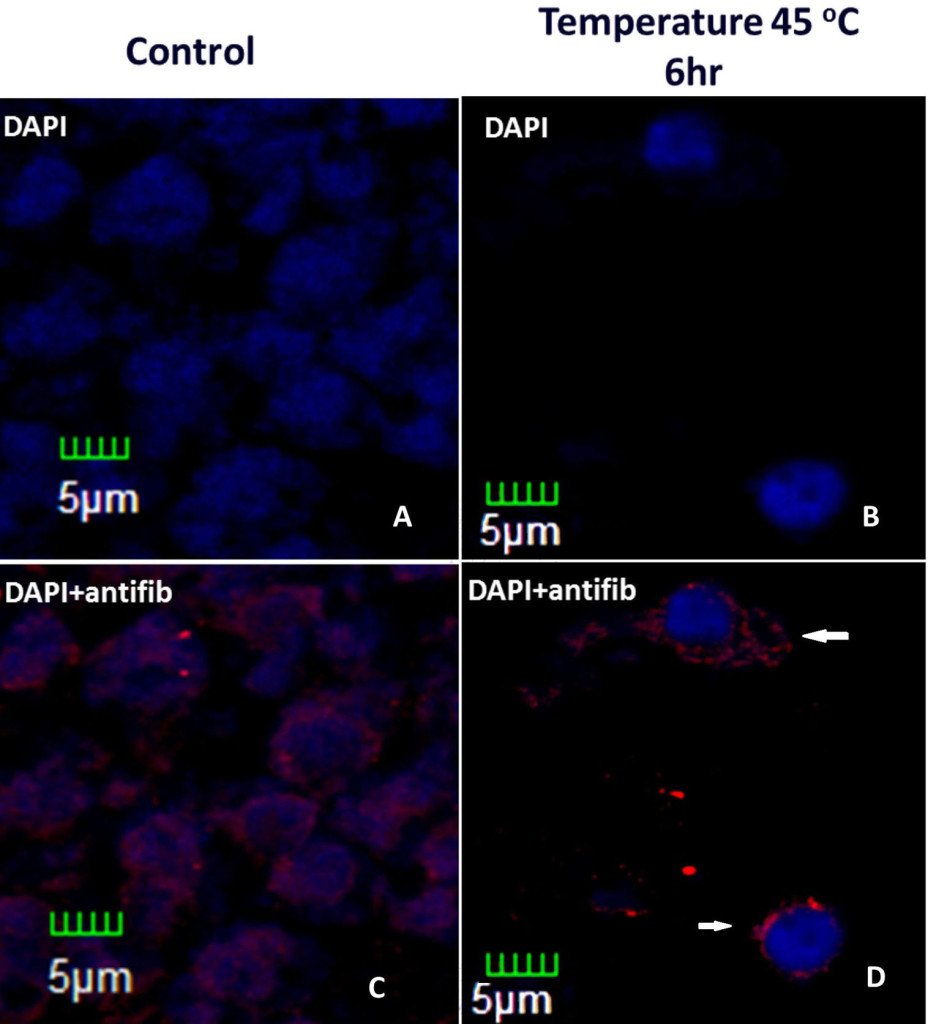

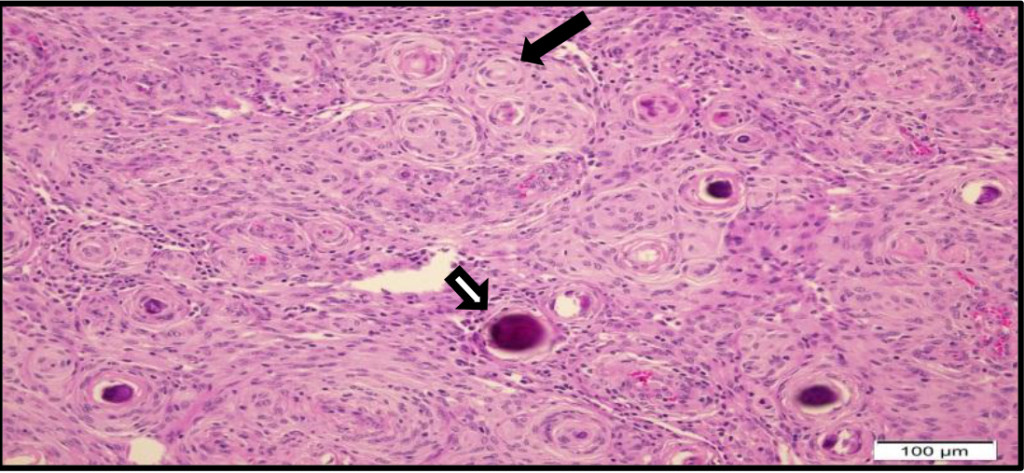

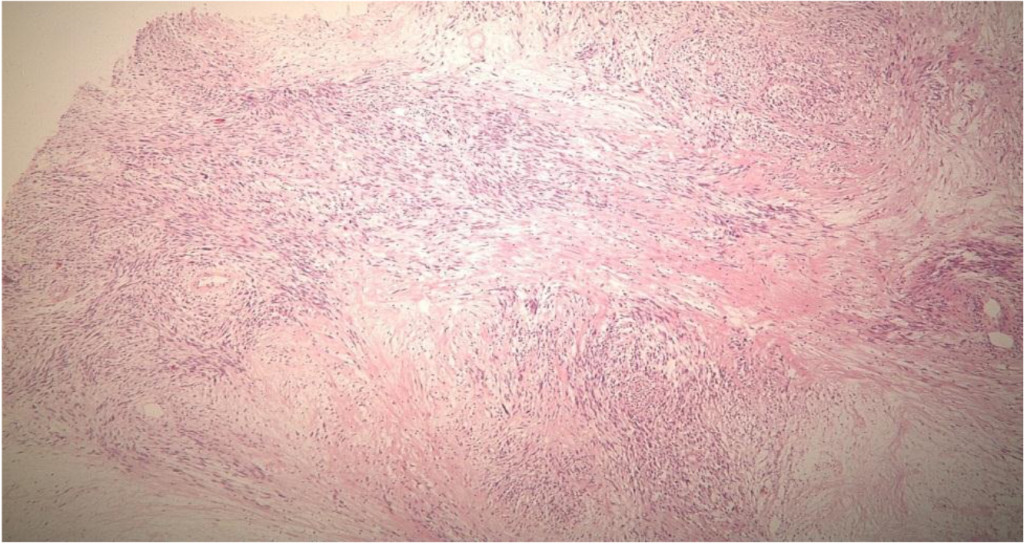

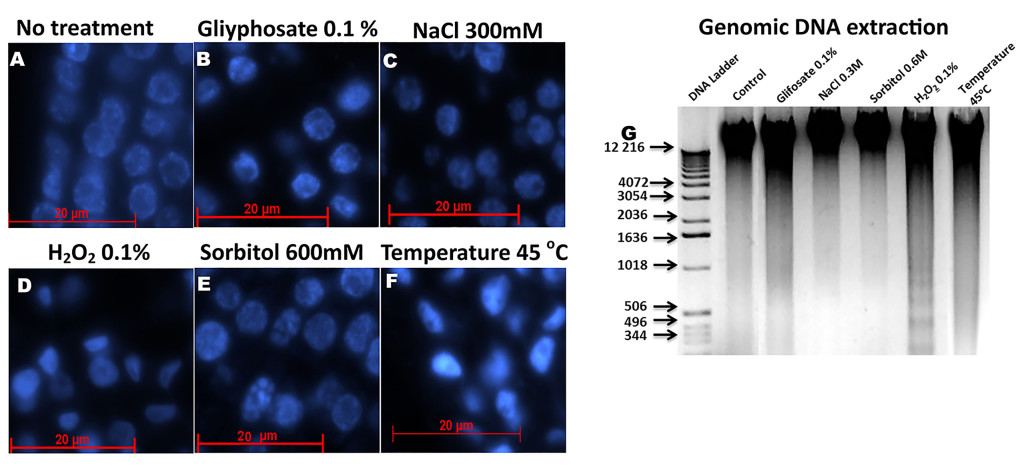

In of B. oleracea florets for example, whose nucleuses have a larger size because they are very active, several confocal microscopy studies have been carried out [48]. A simple analysis using different stress inducers shows how the nucleus changes its shape differentially in each treatment (Figure 2). This may mean that it activates different mechanisms or moon greater or less sensitivity to each stress.

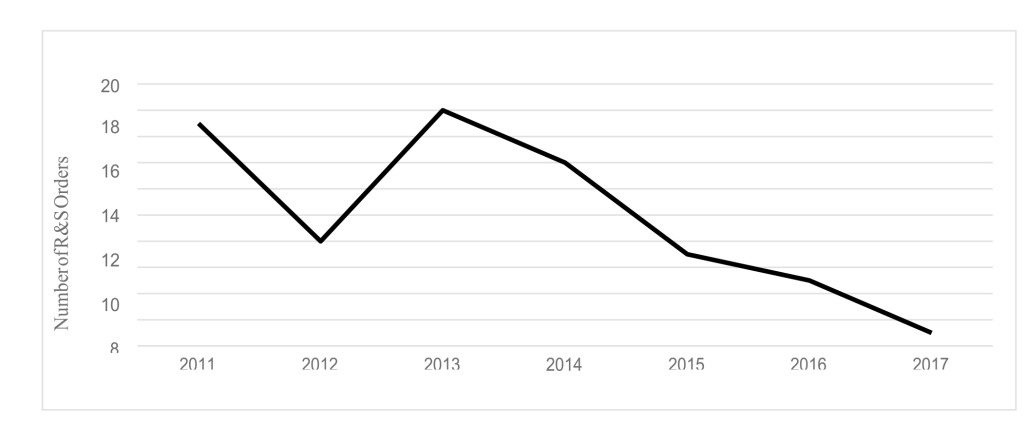

Figure 2. Histological slices of Brassica oleracea inflorescences stained with Dapi a observed with a fluorescence microscope. A): Control, without stress treatment. B): Nuclei of B. oleracea treated with 0.1% glyphosate. C): Nuclei of B. oleracea treated with 300 mM NaCl. D): Nuclei of B. oleracea treated with 0.1% H2O2. E): Nuclei of B. oleracea treated with 600 mM of sorbitol. F): Nuclei of B. oleracea treated at 45 oC. all treatments was applied for six hours, except for H2O2 for 26 hours. G): DNA extraction of in fluoresces after stress. Each lane contains 1 mg of DNA. Nuclear morphology of stressed samples differs from control, especially in C-F. In sorbitol treatments observed a clearly nuclear fragmentation, less in NaCl stress, whereas in D and F a major condensation is observed.

5. p53 protein in Brassica species

Protein p53 acts as a link between cell proliferation, stress and cell death. Is a transcription factor induced in many stress signals responsive to such as oxidative stress, cold and heat stress, nutrition deprivation, apoptosis, phagocytosis, apoptosis and cell cycle arrest [49–51] . also is named as genome guardian due its implication in DNA repair caused e.g. uv radiation and genotoxic drugs such as Danthron, Lansoprazole and Phenolphthalein [52], in human cells, mutation or reduction in p53 gene results in many types of cancer [51, 53, 54].

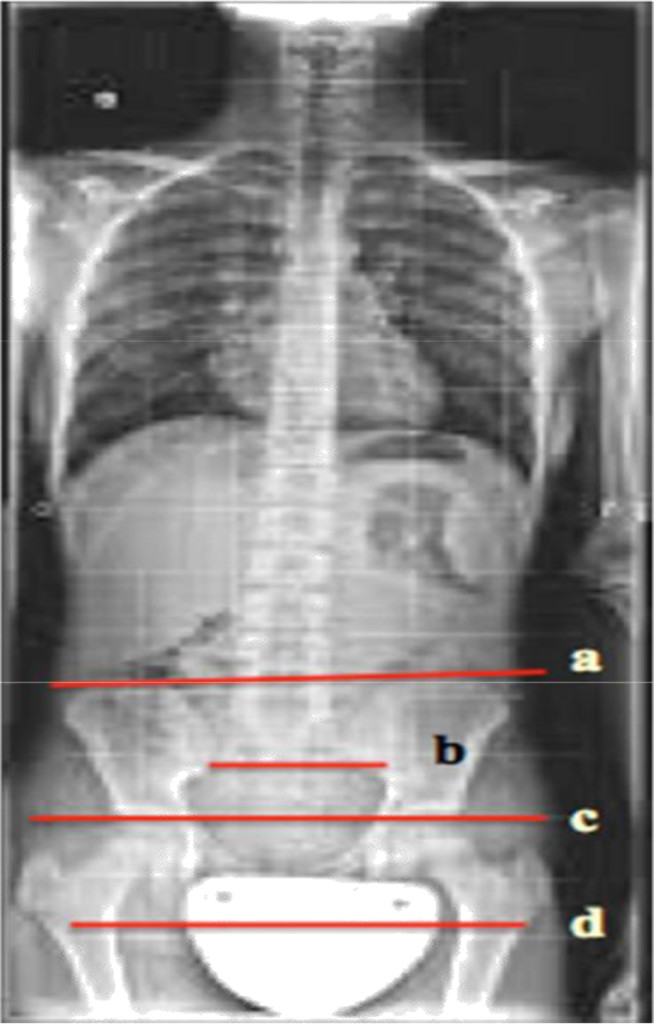

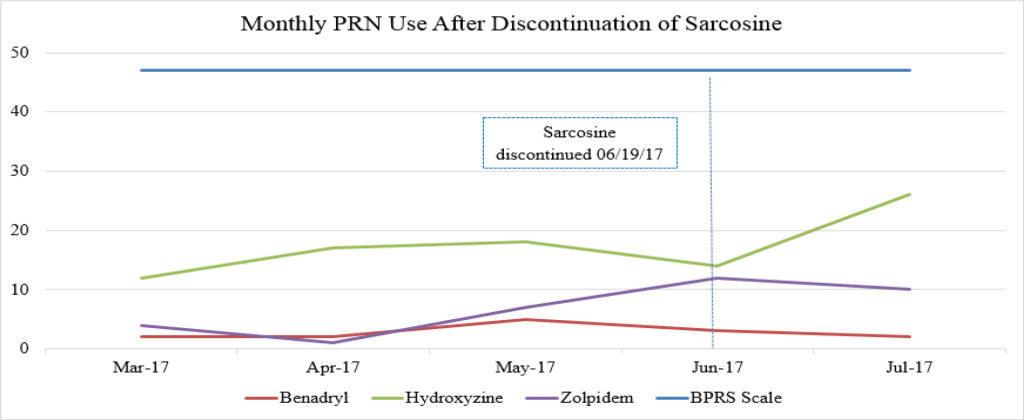

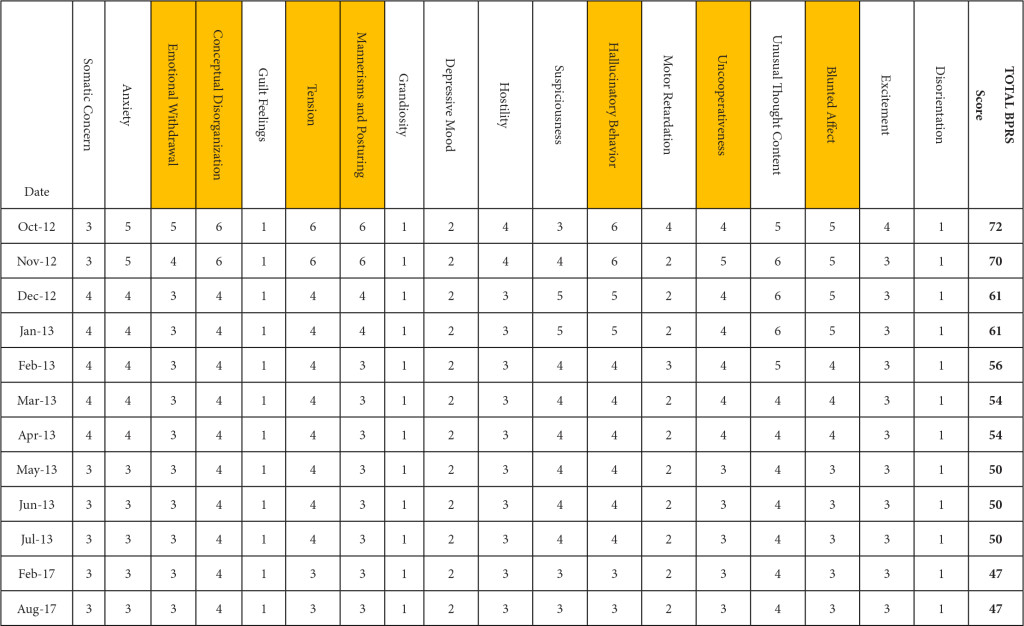

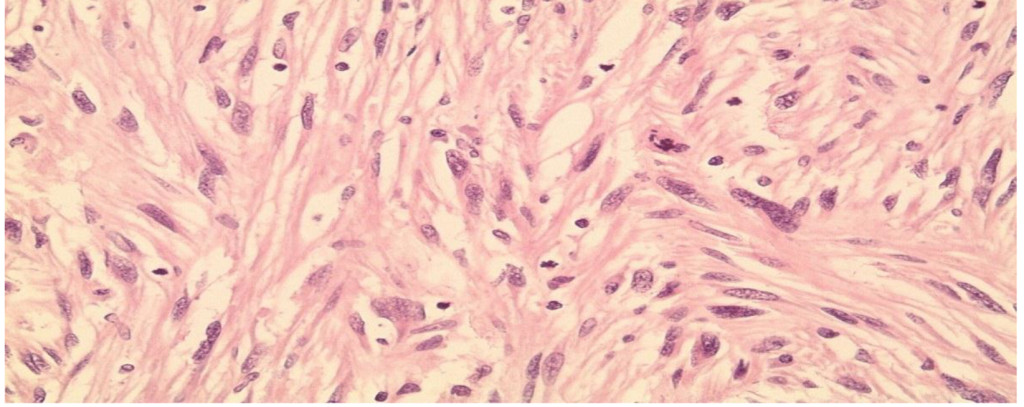

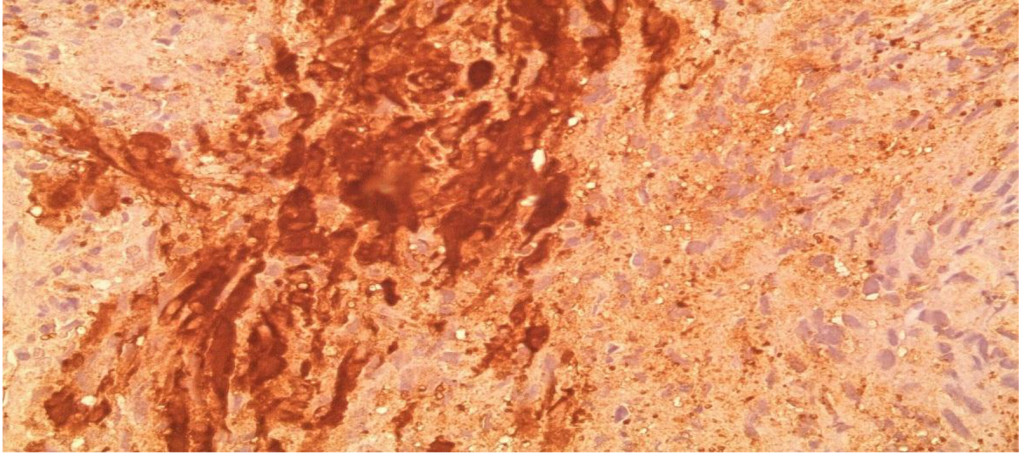

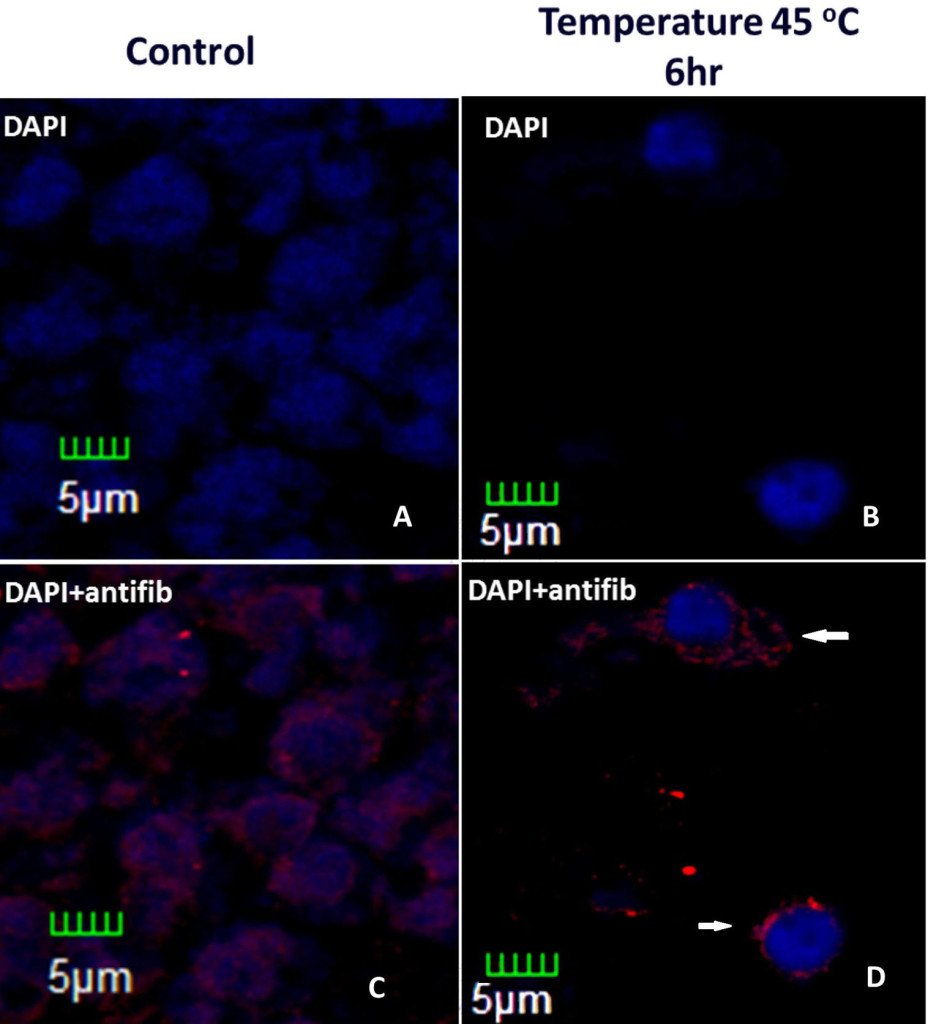

One way of p53 to inhibit tumor formation is by the negative transcriptional regulation of fibrillarin (fib), a nucleolar protein with metyltransferase activity, which processes ribosomal RNA (rRNA) maturation and assemble of ribosomes [48, 55–58] , and has been related with virus movement and systemic infection in plants [59, 60]. Partial silencing of p53 in immortalized human mammary epithelial cells (HME) produces overexpression of fib, leading to changes in the methylation of rRNA that results in changes of translation fidelity, showed by the bypass of added stop codon addition in rRNA and amino acid miss incorporation and alter translation initiation[53]. In Brassica oleracea fibrillarin alters its localization during heat stress as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Histological slices of Brassica oleracea inflorescences under heat stress. Control (without stress) and stressed inflorescences stained with DAPI and incubated with anti-fib antibody. Treatment was six hour longer. In stressed nuclei, fibrillarin are outside the nucleus, which presents condensation (white arrows).

Expression of human p53 in Arabidopsis thaliana induce early senescence and exhibited fascinated phenotype (fused or distorted organs along a plant stem) including thick stems causing by elevated homologous DNA recombination, also shows more secondary inflorescences (twice compared with wt plants) and clustered siliques. NPR1–1 INDUCIBLE 1 (SNI1) a p53 inhibitor in plants, not present in human cells, expressed in in human osteosarcoma U2OS cancer cells, reduce homologous recombination in DNA damage cells by UV radiation and hydroxyurea treatments to induce DNA repair [61].

In brassica, p53 has been detected during Alternaria pathotoxin- and nutritional depletion treatments using human p53 antibodies [Khandelwal, 2002 #106]. In proliferating callus, the amount of p53 is less than decaying callus (induced by nutrient starvation) and pathotoxin treated callus in 2.2 fold and 1.88 fold respectively. Similar results shows p53 in leaves. Senescent and Pathotoxin·treated presents twice the concentration observed in healthy leaves [62].

Transformed B. juncea calli with osmotin gene, a pathogenesis related protein, presents tolerance against Alternaria toxin compared with wt calli. This tolerance correlates with lower levels of p53 protein. With 0.5 and 1.0 units of toxin treatment, non-transformed calli levels of p53 increase 1.85 and 3.3-fold compared with control conditions (no toxin) whilst the levels increase 1.41 and 1.89-fold in transformed calli. This observation seems to be result of a delay in PCD triggers by hypersensitive response (HR) [63].

P53 is very interesting, although there are only these two examples, very similar to the possible role of p53 in stress and cell death, although in other organisms the link between different metabolic and signaling pathways. In this way, p53 covers almost all the phenomena present in plants, from the metabolic state, to RCD.

Many interaction partners need to be confirmed in most pathways, including apoptosis, p53 signaling pathway and senesce. This is confirmed by the fact that in databases such as KEGG there are no those that are specific to plant species, and the evidence of the presence of homologous proteins is generally reached just by bioinformatics

Conclusion

Brassica species have served as an important source of knowledge regarding stress and cell death, even finding in them, the first evidences of the role of certain molecules, e.g. p53 in these events.

All these discoveries have been carried out using “classic” and “modern” techniques, which has provided a broad background that serves as a firm basis for new discoveries in these fields of research. Much remains to be contributed to them, since most of the efforts in these issues are aimed at human health and for this reason represent a great opportunity for future research.

Abbreviations

aa – amino acids

ACD – Accidental cell death

CD – Cell death

CysP – cysteine protease

Fib – fibrillarin

MeJa – methyl jasmonate

PCD – Programmed cell death

PLC – phospholipase C

ROS – Reactive oxygen species

rRNA – ribosomal RNA

RCD – Regulated cell death

WT – wild type

References

- Wang W, Vinocur B, Altman A (2003) Plant responses to drought, salinity and extreme temperatures: towards genetic engineering for stress tolerance. Planta 218: 1–14. [crossref]

- Fujita M, Fujita Y, Noutoshi Y, Takahashi F, Narusaka Y, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, et al. (2006) Crosstalk between abiotic and biotic stress responses: a current view from the points of convergence in the stress signaling networks. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 9: 436–42.

- Atkinson NJ, Urwin PE (2012) The interaction of plant biotic and abiotic stresses: from genes to the field. J Exp Bot 63: 3523–3543. [crossref]

- Petrov V, Hille J, Mueller-Roeber B, Gechev TS (2015) ROS-mediated abiotic stress-induced programmed cell death in plants. Frontiers in Plant Science.

- Mittler R (2002) Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci 7: 405–410. [crossref]

- Baxter A, Mittler R, Suzuki N (2014) ROS as key players in plant stress signalling. J Exp Bot 65: 1229–1240. [crossref]

- Verma V, Ravindran P, Kumar PP (2016) Plant hormone-mediated regulation of stress responses. BMC Plant Biol 16: 86. [crossref]

- Galluzzi L, Bravo-San Pedro JM, Vitale I, Aaronson SA, Abrams JM, et al. (2015) Essential versus accessory aspects of cell death: recommendations of the NCCD 2015. Cell Death Differ 22: 58–73. [crossref]

- Kanduc D, Mittelman A, Serpico R, Sinigaglia E, Sinha AA, Natale C, et al. (2002) Cell death: Apoptosis versus necrosis (Review) International Journal of Oncology 21: 165–70.

- Ashkenazi A, Salvesen G (2014) Regulated cell death: signaling and mechanisms. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 30: 337–356. [crossref]

- Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Vandenabeele P, Abrams J, Alnemri ES, et al. (2009) Classification of cell death: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2009. Cell Death Differ 16: 3–11. [crossref]

- Van Hautegem T, Waters AJ, Goodrich J, Nowack MK (2015) Only in dying, life: programmed cell death during plant development. Trends in Plant Science 20: 102–13.

- Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Abrams JM, Alnemri ES, Baehrecke EH, Blagosklonny MV, et al. (2012) Molecular definitions of cell death subroutines: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2012. Cell Death and Differentiation 19: 107–20.

- Pechan PM, Keller WA (1988) Identification of potentially embryogenic microspores in Brassica napus. Physiologia Plantarum 74: 377–84.

- Telmer CA, Newcomb W, Simmonds DH (1995) Cellular changes during heat shock induction and embryo development of cultured microspores ofBrassica napus cv. Topas. Protoplasma 185: 106–12.

- Binarova P, Hause G, Cenklová V, Cordewener JHG, Campagne MML (1997) A short severe heat shock is required to induce embryogenesis in late bicellular pollen of Brassica napus L. Sexual Plant Reproduction 10: 200–8.

- Cordewener JHG, Hause G, Görgen E, Busink R, Hause B, Dons HJM, et al. (1995) Changes in synthesis and localization of members of the 70-kDa class of heat-shock proteins accompany the induction of embryogenesis inBrassica napus L. microspores. Planta 196: 747–55.

- Young L, W Wilen R, C Bonham-Smith P (2004) High temperature stress of Brassica napus during flowering reduces micro- and megagametophyte fertility, induces fruit abortion, and disrupts seed production. 485–95 p.

- Angadi SV, Cutforth HW, Miller PR, McConkey BG, Entz MH, Brandt SA, et al. (2000) Response of three Brassica species to high temperature stress during reproductive growth. Canadian Journal of Plant Science 80: 693–701.

- Rodríguez VM, Soengas P, Alonso-Villaverde V, Sotelo T, Cartea ME, Velasco P (2015) Effect of temperature stress on the early vegetative development of Brassica oleracea L. BMC Plant Biology 15: 145.

- Uchida A, Jagendorf AT, Hibino T, Takabe T, Takabe T (2002) Effects of hydrogen peroxide and nitric oxide on both salt and heat stress tolerance in rice. Plant Science 163: 515–23.

- Wang P, Zhao L, Hou H, Zhang H, Huang Y, et al. (2015) Epigenetic Changes are Associated with Programmed Cell Death Induced by Heat Stress in Seedling Leaves of Zea mays. Plant Cell Physiol 56: 965–976. [crossref]

- Panchuk II, Volkov RA, Schöffl F (2002) Heat Stress- and Heat Shock Transcription Factor-Dependent Expression and Activity of Ascorbate Peroxidase in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 129: 838–53.

- Wang W, Vinocur B, Shoseyov O, Altman A (2004) Role of plant heat-shock proteins and molecular chaperones in the abiotic stress response. Trends in Plant Science 9: 244–52.

- Fabijanski S, Altosaar I, Arnison PG (1987) Heat Shock Response of Brassica oleracea L. (Broccoli). Journal of Plant Physiology 128: 29–38.

- Desclos M, Dubousset L, Etienne P, Le Caherec F, Satoh H, Bonnefoy J, et al. (2008) A Proteomic Profiling Approach to Reveal a Novel Role of <em>Brassica napus</em> Drought 22 kD/Water-Soluble Chlorophyll-Binding Protein in Young Leaves during Nitrogen Remobilization Induced by Stressful Conditions. Plant Physiology. 147: 1830.

- Lin H-H, Lin K-H, Chen S-C, Shen Y-H, Lo H-F (2015) Proteomic analysis of broccoli (Brassica oleracea) under high temperature and waterlogging stresses. Botanical Studies 56: 18.

- Ashraf M, Mehmood S (1990) Response of four Brassica species to drought stress. Environmental and Experimental Botany 30: 93–100.

- Good AG, Zaplachinski ST (1994) The effects of drought stress on free amino acid accumulation and protein synthesis in Brassica napus. Physiologia Plantarum 90: 9–14.

- Runkel F, Hintze M, Griesing S, Michels M, Blanck B, et al. (2012) Alopecia in a viable phospholipase C delta 1 and phospholipase C delta 3 double mutant. PLoS One 7: e39203. [crossref]

- Das S, Hussain A, Bock C, Keller WA, Georges F (2005) Cloning of Brassica napus phospholipase C2 (BnPLC2), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (BnVPS34) and phosphatidylinositol synthase1 (BnPtdIns S1)—comparative analysis of the effect of abiotic stresses on the expression of phosphatidylinositol signal transduction-related genes in B. napus. Planta 220: 777–84.

- Nokhrina K, Ray H, Bock C, Georges F (2014) Metabolomic shifts in Brassica napus lines with enhanced BnPLC2 expression impact their response to low temperature stress and plant pathogens. GM Crops & Food 5: 120–31.

- Kerr JFR, Wyllie AH, Currie AR (1972) Apoptosis: A Basic Biological Phenomenon with Wide-ranging Implications in Tissue Kinetics. British Journal of Cancer 26: 239–57.

- Duprez L, Wirawan E, Vanden Berghe T, Vandenabeele P (2009) Major cell death pathways at a glance. Microbes Infect 11: 1050–1062. [crossref]

- Galluzzi L, Maiuri MC, Vitale I, Zischka H, Castedo M, Zitvogel L, et al. (2007) Cell death modalities: classification and pathophysiological implications. Cell Death Differ 14: 1237–43.

- Golstein P, Kroemer G (2007) Cell death by necrosis: towards a molecular definition. Trends Biochem Sci 32: 37–43. [crossref]

- Vanden Berghe T, Linkermann A, Jouan-Lanhouet S, Walczak H, Vandenabeele P (2014) Regulated necrosis: the expanding network of non-apoptotic cell death pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15: 135–147. [crossref]

- Van Doorn WG, Beers EP, Dangl JL, Franklin-Tong VE, Gallois P, et al. (2011) Morphological classification of plant cell deaths. Cell Death Differ 18: 1241–1246. [crossref]

- Van Doorn WG (2011) Classes of programmed cell death in plants, compared to those in animals. J Exp Bot 62: 4749–4761. [crossref]

- Coupe SA, Sinclair BK, Watson LM, Heyes JA, Eason JR. Identification of dehydration-responsive cysteine proteases during post-harvest senescence of broccoli florets. J Exp Bot 54: 1045–56.

- Coupe SA, Watson LM, Ryan DJ, Pinkney TT, Eason JR (2004) Molecular analysis of programmed cell death during senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana and Brassica oleracea: cloning broccoli LSD, Bax inhibitor and serine palmitoyltransferase homologues. Journal of Experimental Botany 55: 59–68.

- Watanabe M, Setoguchi D, Uehara K, Ohtsuka W, Watanabe Y (2002) Apoptosis-like cell death of Brassica napus leaf protoplasts. New Phytologist 156: 417–26.

- Tewari RK, Hadacek F, Sassmann S, Lang I (2013) Iron deprivation-induced reactive oxygen species generation leads to non-autolytic PCD in Brassica napus leaves. Environmental and Experimental Botany 91: 74–83.

- Tewari RK, Bachmann G, Hadacek F (2015) Iron in complex with the alleged phytosiderophore 8-hydroxyquinoline induces functional iron deficiency and non-autolytic programmed cell death in rapeseed plants. Environmental and Experimental Botany 109: 151–60.

- Wan L, Xia Q, Qiu X, Selvaraj G (2002) Early stages of seed development in Brassica napus: a seed coat-specific cysteine proteinase associated with programmed cell death of the inner integument. The Plant Journal 30: 1–10.

- Gavrieli Y, Sherman Y, Ben-Sasson SA (1992) Identification of programmed cell death in situ via specific labeling of nuclear DNA fragmentation. J Cell Biol 119: 493–501. [crossref]

- Eason JR, Ryan DJ, Watson LM, Hedderley D, Christey MC, Braun RH, et al. (2005) Suppression of the cysteine protease, aleurain, delays floret senescence in Brassica oleracea. Plant Molecular Biology. 57: 645–57.

- Loza-Muller L, Rodríguez-Corona U, Sobol M, Rodríguez-Zapata LC, Hozak P, Castano E (2015) Fibrillarin methylates H2A in RNA polymerase I trans-active promoters in Brassica oleracea. Frontiers in Plant Science. 6: 976.

- Perwez Hussain S, Harris CC (2006) p53 Biological Network: At the Crossroads of the Cellular-Stress Response Pathway and Molecular Carcinogenesis. Journal of Nippon Medical School 73: 54–64.

- Levine AJ, Oren M (2009) The first 30 years of p53: growing ever more complex. Nat Rev Cancer 9: 749–758. [crossref]

- Brady CA, Attardi LD (2010) p53 at a glance. J Cell Sci 123: 2527–2532. [crossref]

- Brambilla G, Mattioli F, Martelli A (2010) Genotoxic and carcinogenic effects of gastrointestinal drugs. Mutagenesis 25: 315–326. [crossref]

- Marcel V, Ghayad Sandra E, Belin S, Therizols G, Morel A-P, Solano-Gonzàlez E, et al. p53 Acts as a Safeguard of Translational Control by Regulating Fibrillarin and rRNA Methylation in Cancer. Cancer Cell. 24: 318–30.

- Joerger AC, Fersht AR (2016) The p53 Pathway: Origins, Inactivation in Cancer, and Emerging Therapeutic Approaches. Annual Review of Biochemistry 85: 375–404.

- Cerdido A, Medina FJ. Subnucleolar location of fibrillarin and variation in its levels during the cell cycle and during differentiation of plant cells. Chromosoma 103: 625–34.

- Newton K, Petfalski E, Tollervey D, Cáceres JF. Fibrillarin Is Essential for Early Development and Required for Accumulation of an Intron-Encoded Small Nucleolar RNA in the Mouse. Molecular and Cellular Biology 23: 8519–27.

- Amin MA, Matsunaga S, Ma N, Takata H, Yokoyama M, Uchiyama S, et al. Fibrillarin, a nucleolar protein, is required for normal nuclear morphology and cellular growth in HeLa cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 360: 320–6.

- Rodriguez-Corona U, Pereira-Santana A, Sobol M, Rodriguez-Zapata LC, Hozak P, Castano E. Novel Ribonuclease Activity Differs between Fibrillarins from Arabidopsis thaliana. Frontiers in Plant Science.

- Canetta E, Kim SH, Kalinina NO, Shaw J, Adya AK, Gillespie T, et al. (2008) A Plant Virus Movement Protein Forms Ringlike Complexes with the Major Nucleolar Protein, Fibrillarin, In Vitro. Journal of Molecular Biology. 376: 932–7.

- Li Z, Zhang Y, Jiang Z, Jin X, Zhang K, et al. (2018) Hijacking of the nucleolar protein fibrillarin by TGB1 is required for cell-to-cell movement of Barley stripe mosaic virus. Mol Plant Pathol 19: 1222–1237. [crossref]

- Ma H, Song T, Wang T, Wang S (2016) Influence of Human p53 on Plant Development. PLoS One 11: e0162840. [crossref]

- Khandelwal A, Kumar A, Banerjee M, Garg GK (2002) Effect of alternaria pathotoxin(s) on expression of p53-like apoptotic protein in calli and leaves of Brassica campestris. Indian journal of experimental biology. 40: 89–94.

- Taj G, Kumar A, Bansal KC, Garg GK (2004) Introgression of osmotin gene for creation of resistance against Alternaira blight by perturbation of cell cycle machinery. Indian Journal of Biotechnology. 3: 291–8.