Abstract

Biodegradable plastics have caught a lot of attention for their potential to contribute to a more sustainable society. However, mechanical and barrier properties need to be improved to allow for applicability in e.g. food packaging. In the current paper, a composite film material consisting of chitin nanoparticles that can be produced at low cost from e.g. crustacean shells, and polylactic acid is presented.

A novel method was used to make nano-chitin in ethanol suspensions, which prevents polylactic acid hydrolysis during fabrication. With increasing concentration of nano-chitin particles, the film tensile strength and UV-blocking improved. Furthermore, the nanoparticles improved maximum heat tolerance, without altering the processing temperature. All these aspects contribute positively to the development of novel biodegradable packaging materials, and further it is expected that customers’ willingness to pay outweighs costs related to production for which only proven technology is needed, which brings this novel packaging concept a step closer to application.

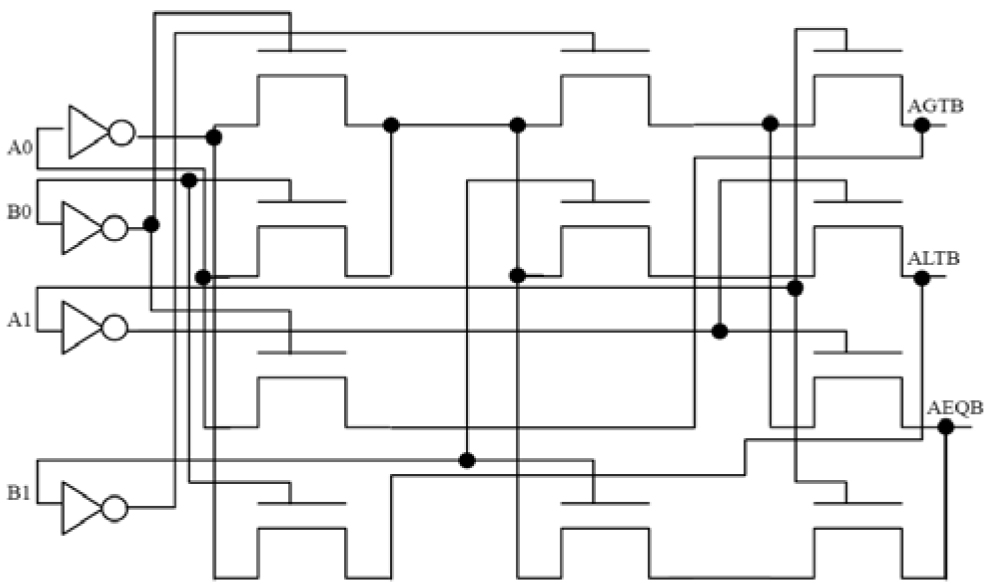

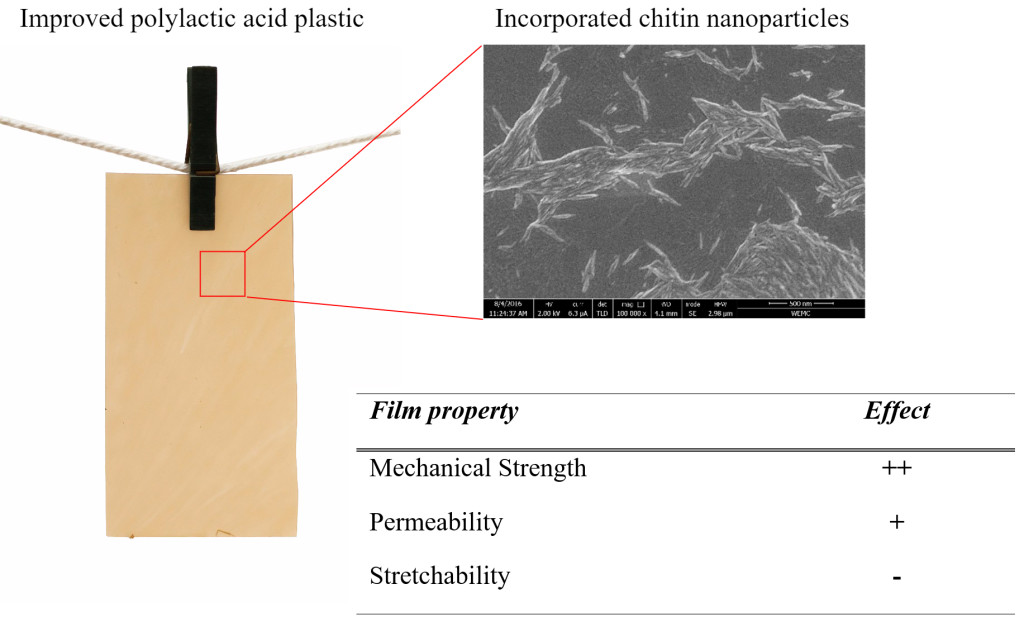

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

- Chitin nanoparticles can effectively be manufactured in ethanol

- Nano-chitin suspensions in ethanol can be used to make composite polylactic acid (PLA) films.

- Addition of chitin nanoparticles to PLA improves film tensile strength and Young’s modulus.

- Addition of chitin nanoparticles to PLA improves UV-blocking.

- Market prospects of PLA composites with chitin nanoparticles look promising.

Key words

Biodegradable plastic, chitin, nanocomposite, polylactic acid, mechanical properties, extrusion.

Introduction

For 2020, it is expected that almost one trillion food and drink packages will be thrown away in Europe alone; the growth rate being three percent on a yearly basis [1]. Most of these packages are made from plastics based on fossil fuels. Since these sources are finite, and the production and waste created by these packages have a large environmental impact, an alternative is needed to secure an economically and environmentally sustainable future.

Plastics that are both biobased and biodegradable provide a promising alternative. These plastics require less or no fossil fuels and their production leads to less greenhouse gas emissions than their petrol-based counterparts [2]. Moreover, biodegradable plastics can fully degrade in several weeks to a few years, compared to a period lasting up to ten centuries for regular plastics. For example, polylactic acid (PLA) is found to decompose within 3 weeks under the right conditions [3]. Additionally, bioplastics can be industrially composted with other biodegradable waste, such as food and garden waste, whilst petrol-based polymers are domestic waste and commonly end up in landfills or incineration ovens [4]. However, the properties of bioplastic packaging materials are not as good as those of their petrol-based counterparts: mechanical properties, thermal stability and barrier properties need to be further improved [5].

One way to meet this challenge is through the use of biodegradable nanoparticles, which are known to be effective structure elements decreasing the gas and water permeability [5] and altering the mechanical properties [6]. Ideally these nanoparticles can be made at low cost; therefore, we considered only proven technology for the investigations presented here. The component of choice for nanoparticle production is chitin, a biodegradable, non-toxic, hydrophobic compound that is the second most abundant polysaccharide in the world [7,8]. It is found in arthropod exoskeletons such as shrimp shells, and fungal cell walls, and it is estimated that one billion tons of chitin are naturally synthesized yearly [9]. Chitin nanoparticles can be formed by acid treatment which causes partial deacetylation, exposing amino moieties. Protonation in the acidic environment provides a positive charge to these moieties, stabilizing the colloidal suspension due to repulsive forces [10]. Part of the world chitin production is readily available, e.g. as waste from shrimp production of which the regular disposal is costly [11].

Research has shown that nano-sized chitin can improve barrier properties when embedded in a polymer matrix [12,13]. This is especially useful for food packaging applications, since barrier properties are related to the shelf life of food, which in turn is linked to a potential decrease of the amount of food that is wasted (currently ~135 kg per capita per year) [14]. In this respect, the effect on reduction of food waste may surpass the effect on plastic waste considerably, thereby also contributing to a sustainable society.

Polylactic acid is currently recognized as the most promising biobased and biodegradable polymer for food packaging applications [3,15,16], although mechanical and barrier properties are still sub- optimal. To improve this, Herrera et al [17] incorporated chitin nanoparticles into PLA, although we expect that the results that were obtained were less favourable due to hydrolysis of PLA at high temperatures [18]. In the current paper, this is circumvented by using ethanol in a novel preparation method for chitin nanoparticles. These particles were incorporated in PLA films produced through compression moulding, and further characterised amongst others for their mechanical and barrier properties, and compared to industrial standards. Lastly the economic feasibility of the new composite is evaluated, and the opportunities for large scale production are touched upon.

Materials & methods

Materials

Practical grade chitin powder (Sigma-Aldrich) was used for synthesis of chitin nanoparticles. For the composites the fabricated nanoparticles, PLA (PLA LX175, Corbion) and the plasticizer GTA (Sigma- Aldrich) were used at the concentrations mentioned in the respective sections.

Preparation of nanoparticles

To obtain chitin nanoparticles (nChit), the method by Revol and Marchessault [19] was adapted to enable a larger yield (typically around 10%) and obtain a suspension in ethanol. The chitin powder was hydrolysed in hydrochloric acid (3 M) using 1 gram per ml HCl, at 100 °C for 90 minutes. The mixture was cooled on ice and then put through several centrifugal steps. Each step consisted of a 5- minute centrifugation (Sorvall RC6+ centrifuge) at 8000 rpm, after which the supernatant was discarded. The tubes were refilled with demi-water and the pellet was resuspended. This procedure was repeated until the supernatant became cloudy at pH 1.8-2.0. At this point the tubes were not decanted but centrifuged again for 25 minutes at 12.000 rpm. The pellet was then oven-dried (Memmert UM100) at 100 °C, and re-suspended in ethanol.

After another 25-minute spin at 12.000 rpm, the five-minute centrifugation steps were repeated, now using ethanol instead of demi-water, until supernatant appeared cloudy. [Please note that freeze-drying of nChit/H2O suspensions was effective in terms of the removal of water, but the particles could not be re-dispersed in ethanol. Decreasing the moisture-content during the nChit production process by oven-drying appeared most efficient and time-saving.] This supernatant was collected (‘wash I’), as well as the supernatant from the following spin (‘wash II’), while the pellet was discarded. Wash I and wash II were concentrated using a rotary evaporator (Heidolph, 175 mbar, 45 °C); the actual concentration was determined by dry weight measurement of 1 mL nchit/EtOH suspension after oven-drying (Memmert UM100) at 100 °C for 2-4 hours.

The average moisture content of the nChit-suspension was measured by Karl Fischer titration (Mettler Toledo DL38) and determined to be 3.5%.

Preparation of PLA-composites

Nano-chitin (0.5-3 wt%) was mixed with PLA containing 20 wt% glycerol triacetate (plasticizer) using a rheocord kneader (Haake Polylab, Rheomix 3000p) at 180 °C, 50 rounds per minute, for 10 minutes. The resulting mass was pressed into films of about 1 mm thick using a Hot Press (PHI, Los Angeles, USA), at 190 °C and 15000 Pa. Equal distribution of nChit in the films was assessed using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) (FEI, Magellan 400). Before mechanical and permeability testing, the films were conditioned at 20 °C, 55% relative humidity for 5-7 days.

Larger scale composite production was carried out with an extruder (Leistritz ZSE 18 HP-400, Extrusiontechnik GmbH Nurnberg, Germany). Using a plunger pump (Leistritz LSB17, 2016), the nChit in ethanol mixed with GTA was fed to the extruder simultaneously with PLA. Some of the ethanol left the extruder through a vent, or escaped at the backside, but these flows did not contain any nChit, so this did not affect the final product. The extruded strands were cooled in a water bath, pelletized and dried (Gerco DMT 96C, Gerco-Apparatenbau GmbH & Co, Sassenberg Germany) for about 60 hours (48 °C) and pressed into films by compression moulding.

The films were conditioned at 20 °C, and 55% relative humidity for approximately 24 hours before mechanical and optical tests were performed.

Particle characterisation

Dynamic light scattering

The size of chitin nanoparticles (nChit) in ethanol was characterized by dynamic light scattering. The following optical properties were used: refractive indices of 1.560 (chitin) and 1.360 (ethanol) and an absorption index of 0.01 was used (Mastersizer 2000, Malvern Instruments Ltd. v3.50, Malvern, Worcestershire, UK).

Scanning Electron Microscopy

Images of the dried nanoparticle suspension and various PLA nChit composite surfaces were made by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM; FEI-Magellan 400, 2.0 kV, 6.3 pA, 4.1 mm working distance) to investigate nanoparticles and their distribution in the plastics. The nChit suspension was dried at 40 °C for 30 minutes, and all other samples were dried under vacuum for at least 48 hours prior to imaging. Samples were sputter coated with tungsten (~15 nm, Leica EM SCD 500) to avoid charging.

Atomic Force Microscopy

This technique (Bruker Multimode 8-HR, NanoScope Analysis software) was used for 3D-imaging of a dried nChit suspension on silica wafers from which the length and diameter of individual chitin nanoparticles could be deduced.

FTIR

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) (Thermo Scientific, Nicolet iN10 MX Infrared Imaging Microscope) was used to ensure chitin structure was not altered due to the nanoparticle preparation process. Crude chitin powder was compared to dried nano-chitin.

Film characterisation

Optical properties

CIELAB analysis (ASTM E308, Elrepho 2000 datacolor) was performed at three different positions in each sample to assess colour values of the films. Transparency and UV-blocking properties of the films were measured in duplicate by UV/VIS (Beckman Coulter DU720) spectrometry at 200-700 nm.

Mechanical properties

Standard tensile tests (19 °C, 44% relative humidity: ASTM D638) were performed 5-fold using a universal testing machine (Zwick/Roell G80L30, 10 kN cell load, grip distance 80 mm, gauge length 40 mm, speed 200 mm/min). Samples were cut using a bone shaped press mould, and their tensile strength (TS, in MPa), Young’s Modulus (YM, in GPa) and Elongation at break (EAB, in %) were determined. Mean values and standard deviation were corrected for differences in thickness, and compared using ANOVA and Dunnett two-sided t-test assuming equal variance (a=0.05).

Barrier properties

Water vapour transmission (ASTM E96, 21 days at 20 °C, 55% RH) was measured in duplicate with kneader-prepared films. Using silicone sealant, 1.4 mm thick films were fixed in test cells (85 mm diameter) filled with water, leaving a layer of air between the water and the film. Weight loss was measured at least three times a week for 21 days. The water vapour transfer rate, WVTR (g • mm • m-2 • day-1) determined using [17]:

WVTR = (m • l) / A (1-RH)

Where m is the weight loss in g/day; l is the thickness of the film in mm; A is the film area in m2; and

RH is the relative humidity outside the cup. Data was analysed using a one-sided t-test assuming equal variances (a = 0.05).

Thermal properties

Thermal behaviour was studied by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) (ASTM D3418, PerkinElmer DSC 8000). From this test, the melting point (Tm, in °C) of the plastics was calculated.

Antimicrobial properties

Antimicrobial properties of plastic films were tested using an agar diffusion method adapted from Rhim [20] and Fernandez-Saiz [21]. PLA discs (15 mm diameter) were sterilized by submerging in 70% ethanol, and dried in a closed sterilized petri dish. These discs were placed on Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) agar (Becton & Dickinson (BD) BBL BHI, Agar Bacteriological, LP0011, Oxoid) (pH 7.4) streaked with either Escherichia coli W1605 (Gram negative) or Bacillus subtilis (Gram positive), and tested in triplicate. As controls a plate without sample and a plate with dried, agglomerated nChit flakes were used. The plates were incubated at 35 °C for 24 hours, and antimicrobial activity was determined from the inhibition zone diameter.

Biodegradation

To determine whether nChit influences biodegradation of PLA, films (120 × 135 × 1 mm) were buried in a home compost heap (125 × 75 × 75 mm) at a garden site in The Netherlands (latitude 52° 7’ 15” N, longitude 4° 39’ 6” E, altitude -1.5 m). The compost consisted of organic home and garden waste, such as leaves, branches, and vegetable waste. Films were placed vertically in the middle of the compost, with sufficient spacing (10 cm) between samples. Samples consisted of a film with 2 wt% nano-chitin, a film with 2 wt% crude chitin powder, and a control (PLA + 20 wt% GTA). Samples remained in compost for 12 weeks, in the period from October 22 to January 15. Mean outside temperatures dropped from 9.7 °C in October to 3.6 °C in January. Total precipitation ranged from 0.4 mm in October,

75.3 mm in November, to 13.8 mm in December and 48.8 mm in January. Average atmospheric pressure was 1015 mbar, and ambient humidity was approximately 85%. Excavated samples were tissue cleaned, and dried for 8 hours at room temperature prior to weighing.

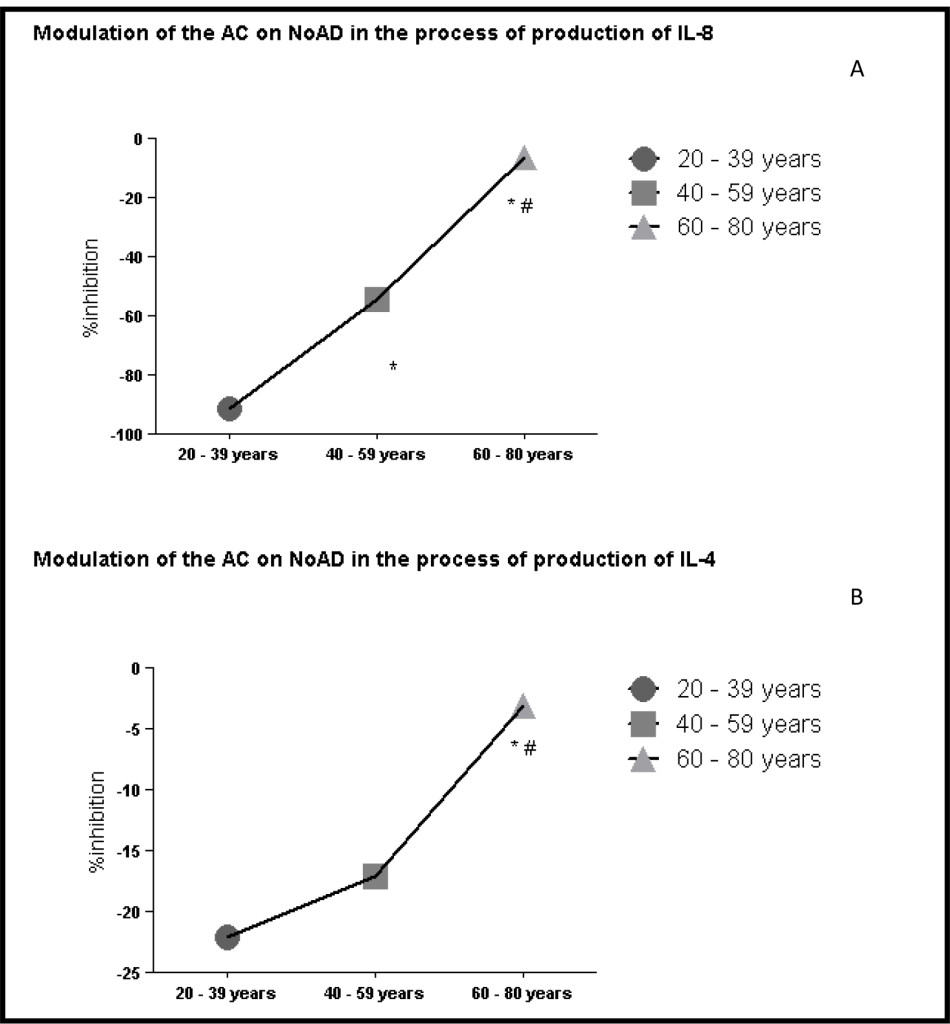

Results and discussion

Morphology and structure

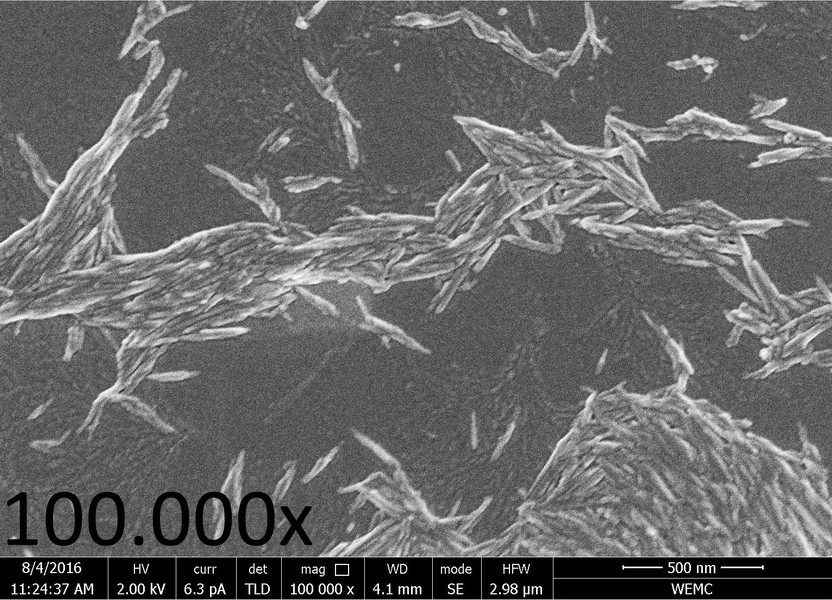

SEM and AFM imaging revealed the rod-shaped morphology (fibres or ‘whiskers’) of nChit (Fig. 1). The average length was 150-200 nm, the diameter is 10-20 nm, as measured by AFM [10].

Figure 1. SEM-image (100.000x magnification, working distance 4.1 mm) of nano-chitin particles, that arranged in typical whiskers.

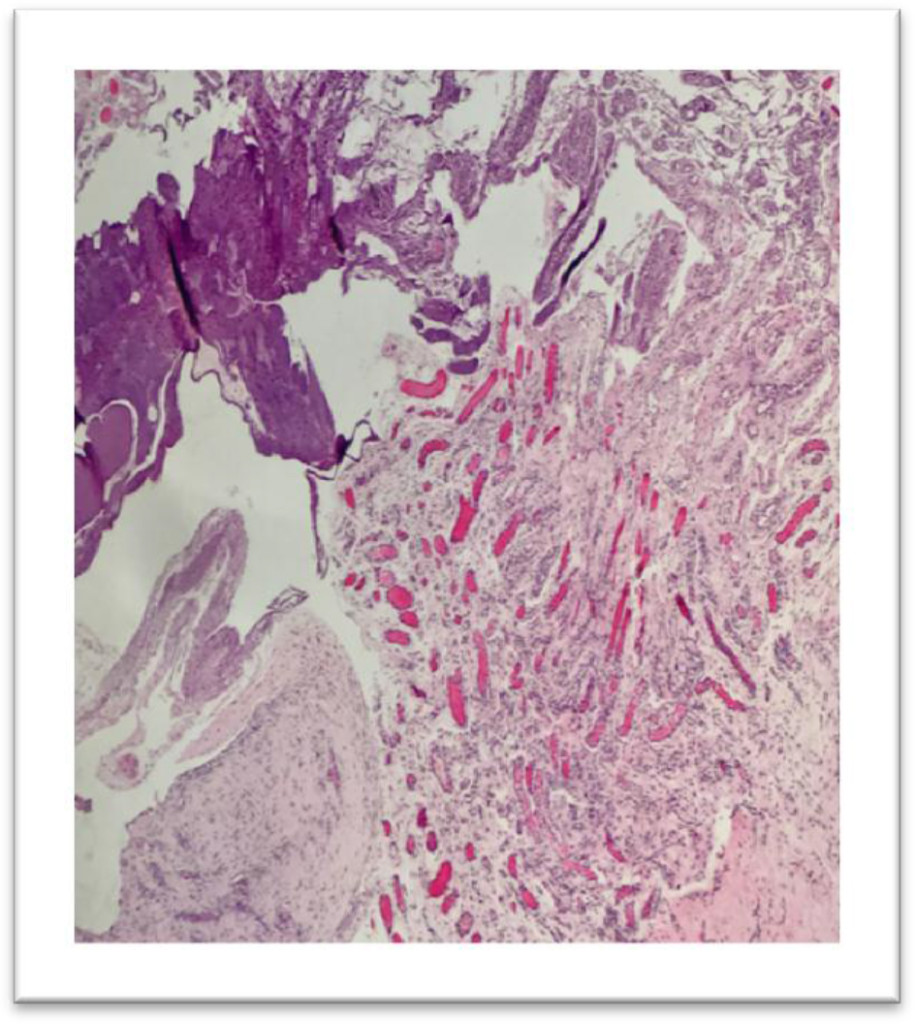

The mixing method used was of great influence on the homogeneity of the films. In kneader prepared films, homogeneity was only found at 0.5% nano-particles while the use of extrusion in combination with compression moulding consistently yielded uniform films (see figure 7 for some impressions). FTIR analysis (details not shown), revealed that the chemical structure of PLA remained intact after processing, indicating that preparation and process conditions used were suitable.

Optical transparency and visual appearance

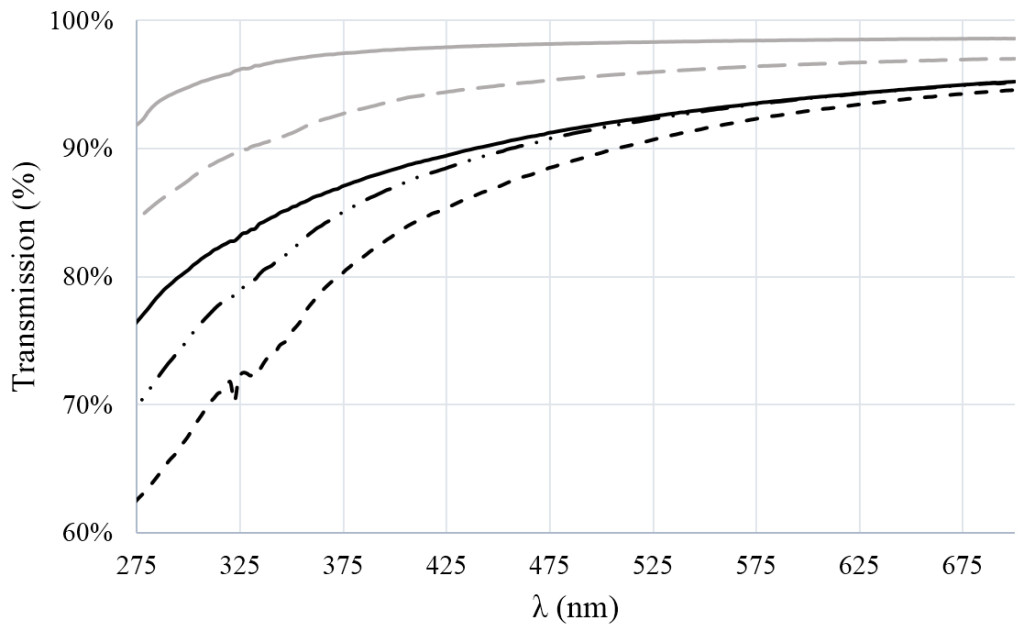

For PLA films, the CIELAB-measurements showed increased transmission at higher wavelength, and this behaviour was also found for films with nano-chitin, albeit at slightly lower values. The effect became stronger when GTA was added, and increased with increasing number of nanoparticles (see figure 2). The biggest effect was found for yellow and magenta transmission, which also lowers transparency of the films, that appear more brown, and opaque.

Figure 2. Transmission (%) in the UV-spectrum of films of 1 mm thickness. Lines indicate (from top to bottom): PLA (solid grey line), PLA + 1% nano-chitin (dashed grey line), PLA + GTA (solid black line), PLA + GTA + 1% nano-chitin (dot-dashed black line), and PLA + GTA + 3% nano-chitin (dashed black line).

Hydrolysis of chitin (N-acetyl-D-glucosamine; see nano-chitin preparation section) results in a high yield of glucosamine products [22], that are believed to be responsible for the colour change through Maillard reactions, similarly as observed in other work for glucosamine-derived products [23][24]. It is good to mention that the brown colour is hardly visible in thin (<0.1mm) films, but it does distinguish the films presented here from low density polyethylene, which show near complete transmission of UV [25]. The UV-blocking effect was also not found for crude chitin powder composites (results not shown). This indicates that through the choice of nano-chitin, e.g. food packaging could be supplied with an intrinsic protective effect that is expected to reduce photochemical processes such as photo-oxidation [26]. However, this is only relevant if the mechanical properties can meet the requirements of food packaging, as discussed next.

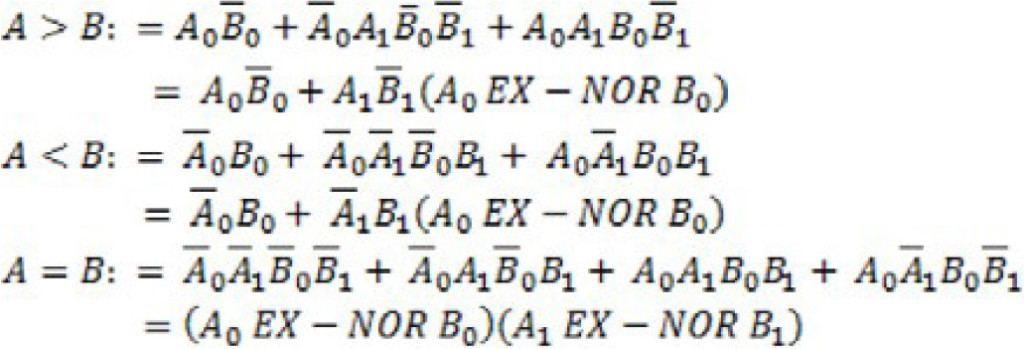

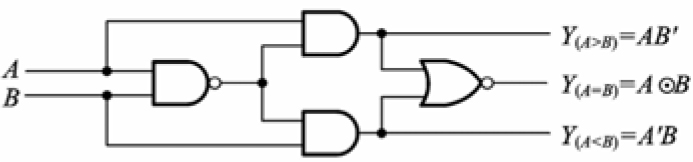

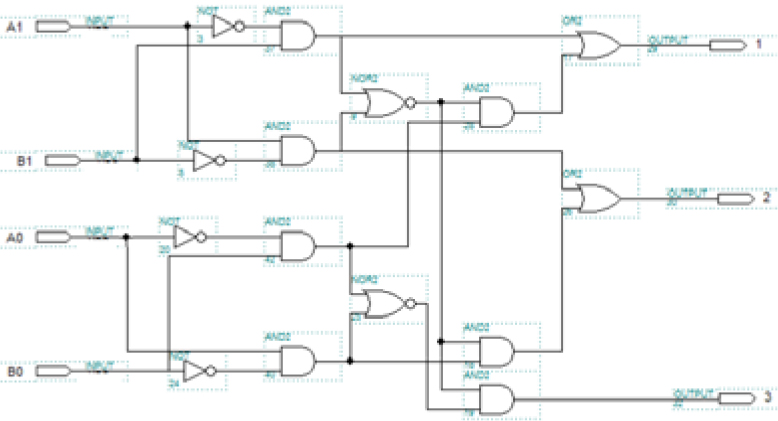

Mechanical properties

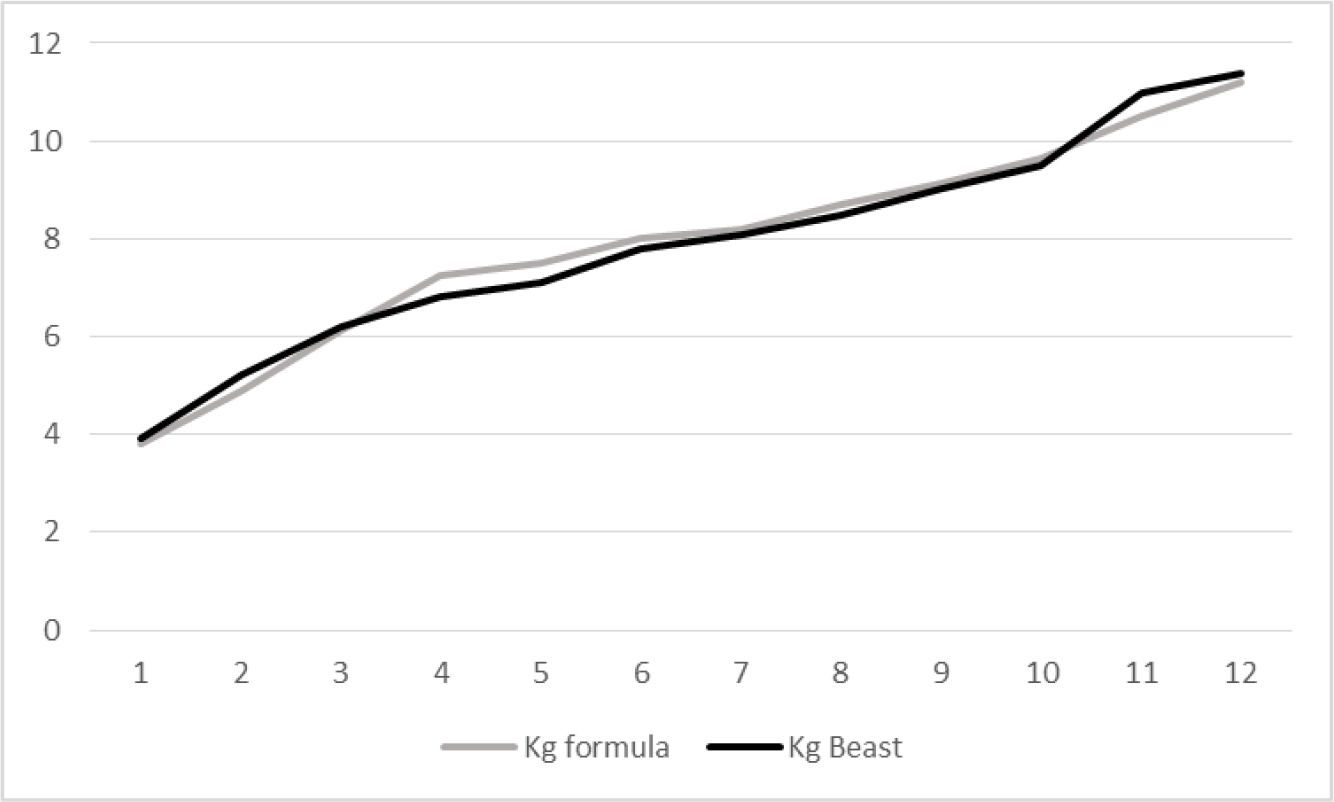

Tensile strength

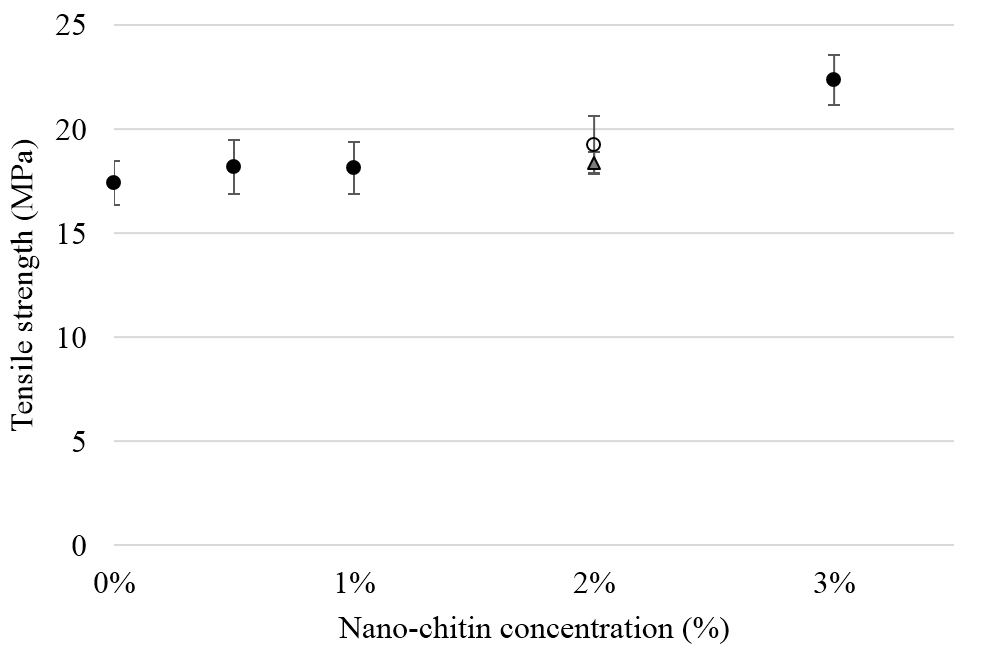

The tensile strength of PLA was not negatively affected by addition of nChit (Fig. 3); at 3% nChit there was even a significant increase compared to PLA without nChit (+4.9 MPa (±1.05), p<0.05). For most films, no necking behaviour was observed, indicating homogeneity at the scale of a few hundred nm3 [27].

Figure 3. Tensile strength (MPa) of PLA composites for various nano-chitin concentrations. Solid dots indicate the composites prepared using the kneader, the open dot indicates the composite made using the extruder. Triangular marker indicates film with 2% crude chitin powder. Values are averaged for five independent sample measurements.

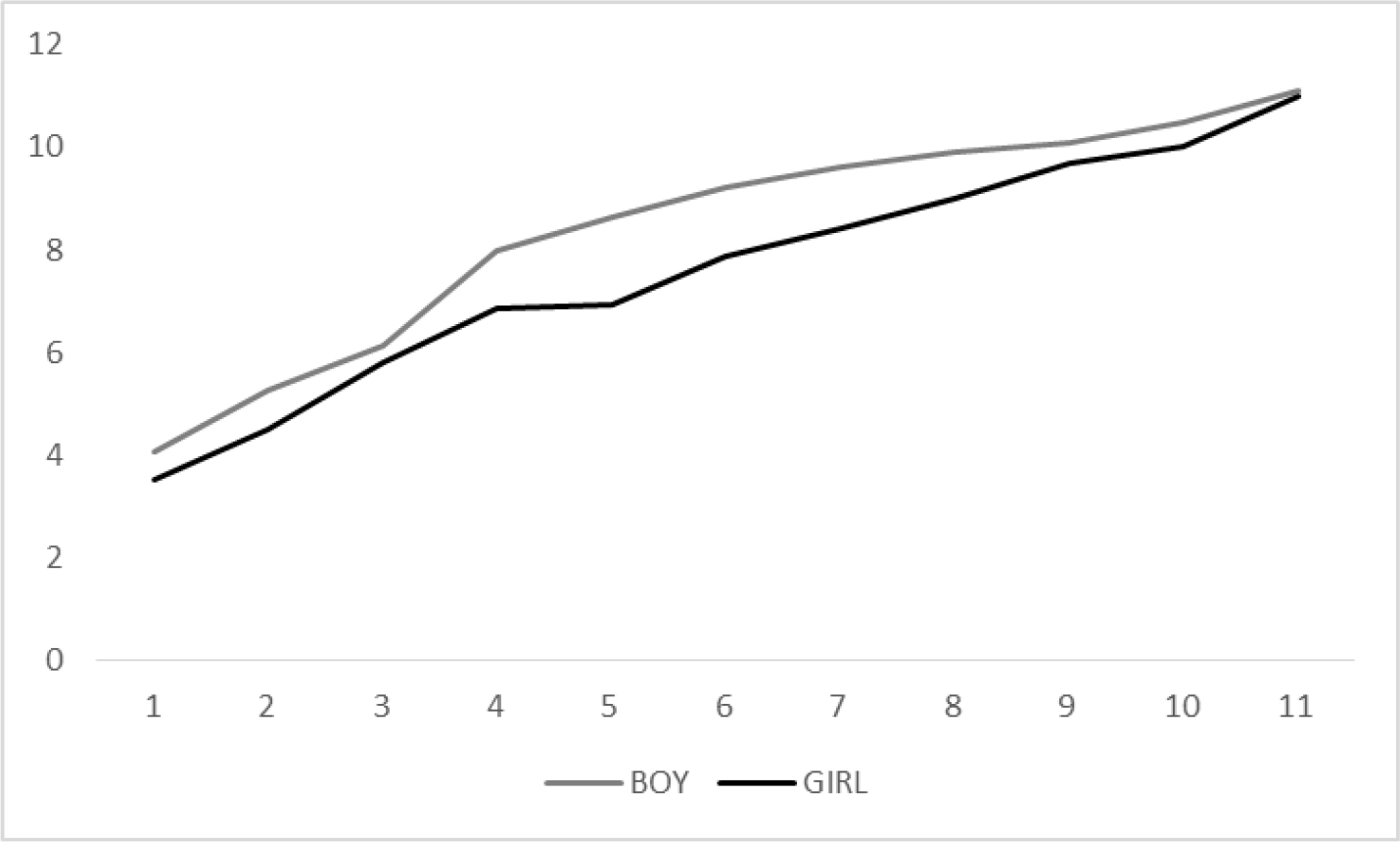

Elongation at break

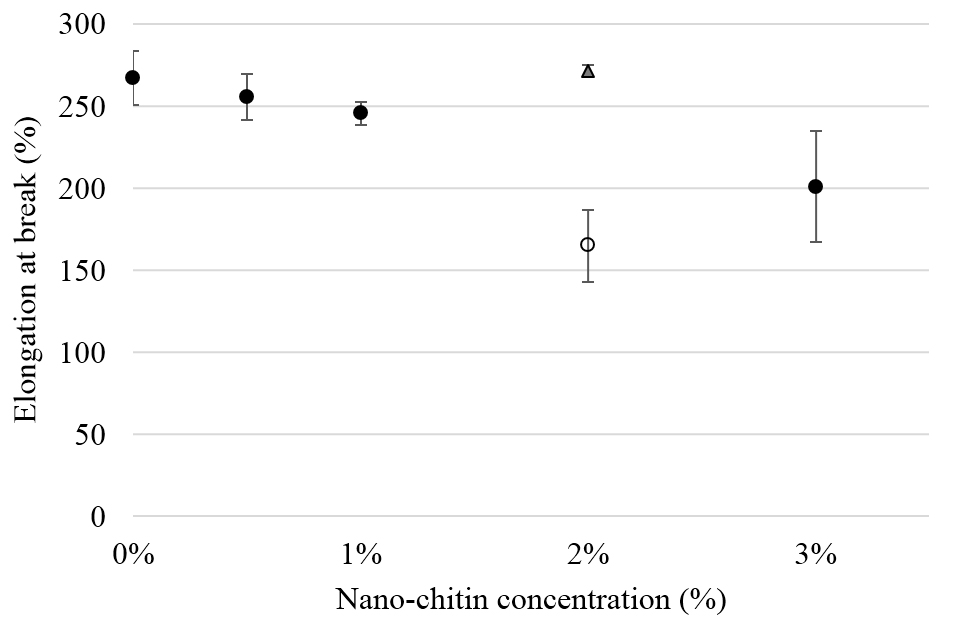

In figure 4, the elongation at break is shown for various nChit concentrations. For the films produced with the kneader, the difference was not significant but the 2% nChit composite manufactured by extrusion was less deformable ~40% (p<0.05); while a 2% crude chitin PLA composite had the same elongation at break as the PLA films. This may be caused by a difference in dispersion of the nanoparticles in the PLA [28]. Nonetheless, a decrease in EAB upon addition of nanoparticles has been frequently reported [28-30] and the results found in our study are still within the range of what otherwise has been reported in literature [17].

Figure 4. Elongation at break (%) of PLA composites with various nChit concentrations. Solid dots indicate the composites prepared using the kneader, the open dot indicates the composite made using the extruder. Triangular marker indicates film with 2% crude chitin powder. Values are averaged for five independent sample measurements.

We previously observed that in the 2% film produced by extrusion, the nanoparticles are much more homogenously distributed, and this is corroborated by the fact that no necking occurred during the tensile test, which is typical for films homogeneously mixed at a scale of a few hundred nm3 [31]. Possibly, the nanoparticles induce stress concentration points, causing crazes that ultimately result in break at the interface between PLA matrix and nanoparticles [32]. In films with crude chitin powder, in which the number of particles is much lower, behaviour similar to PLA was found.

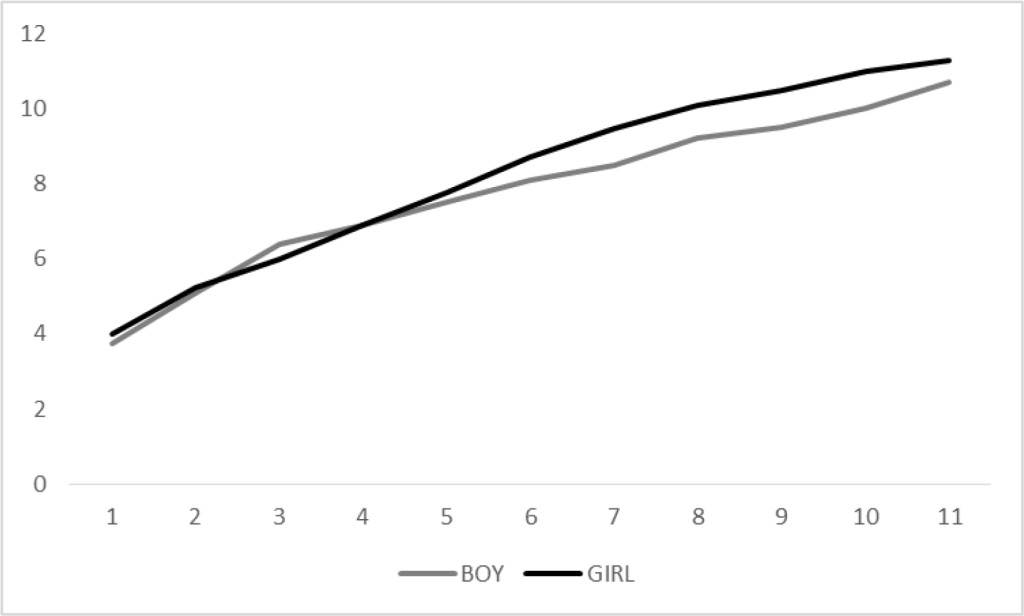

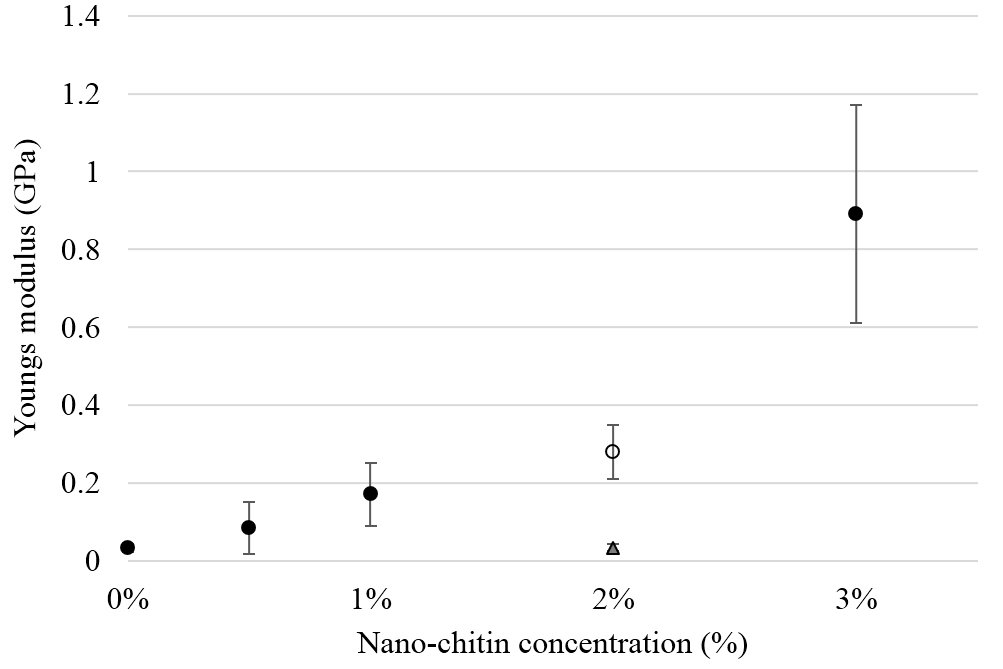

Young’s Modulus

Since the Young’s Modulus (YM), increased with increasing nChit concentration (Fig. 5), it can be concluded that a more rigid PLA composite is formed. Compared to LDPE, the industrial standard, of which the average YM is 0.24 GPa [33], the nano-chitin composites compare well, with the 3% composite even exceeding LDPE considerably (average YM 0.89 ± 0.28 GPa, p<0.05).

Figure 5. Young’s Modulus as function of nano-chitin concentration. Solid dots indicate the composites prepared using the kneader, the open dot indicates the composite made using the extruder. Triangular marker indicates film with 2% crude chitin powder. Values are averaged for five independent sample measurements.

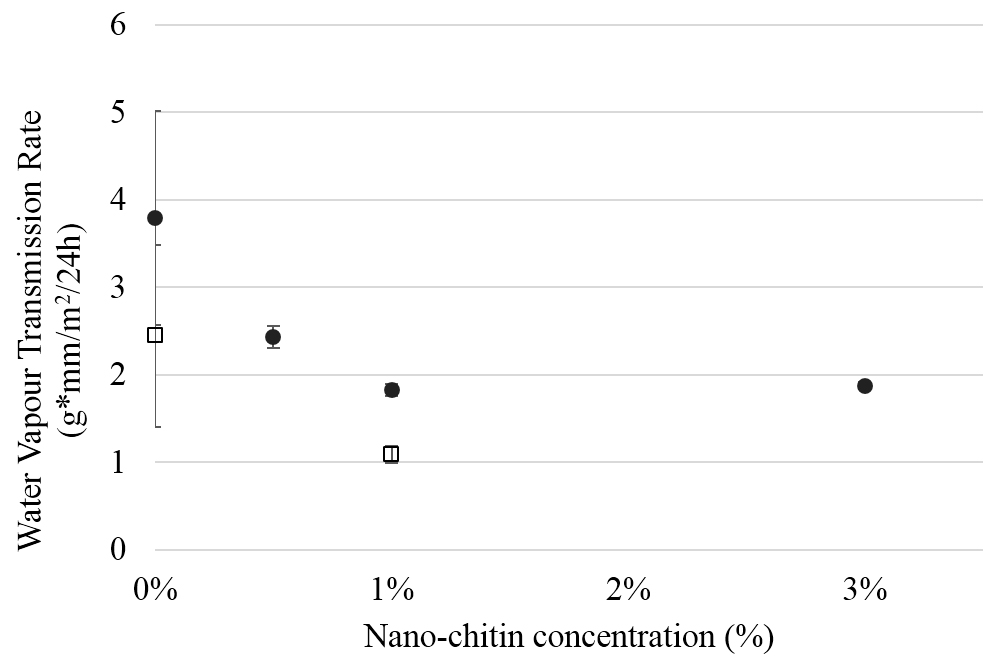

Barrier properties

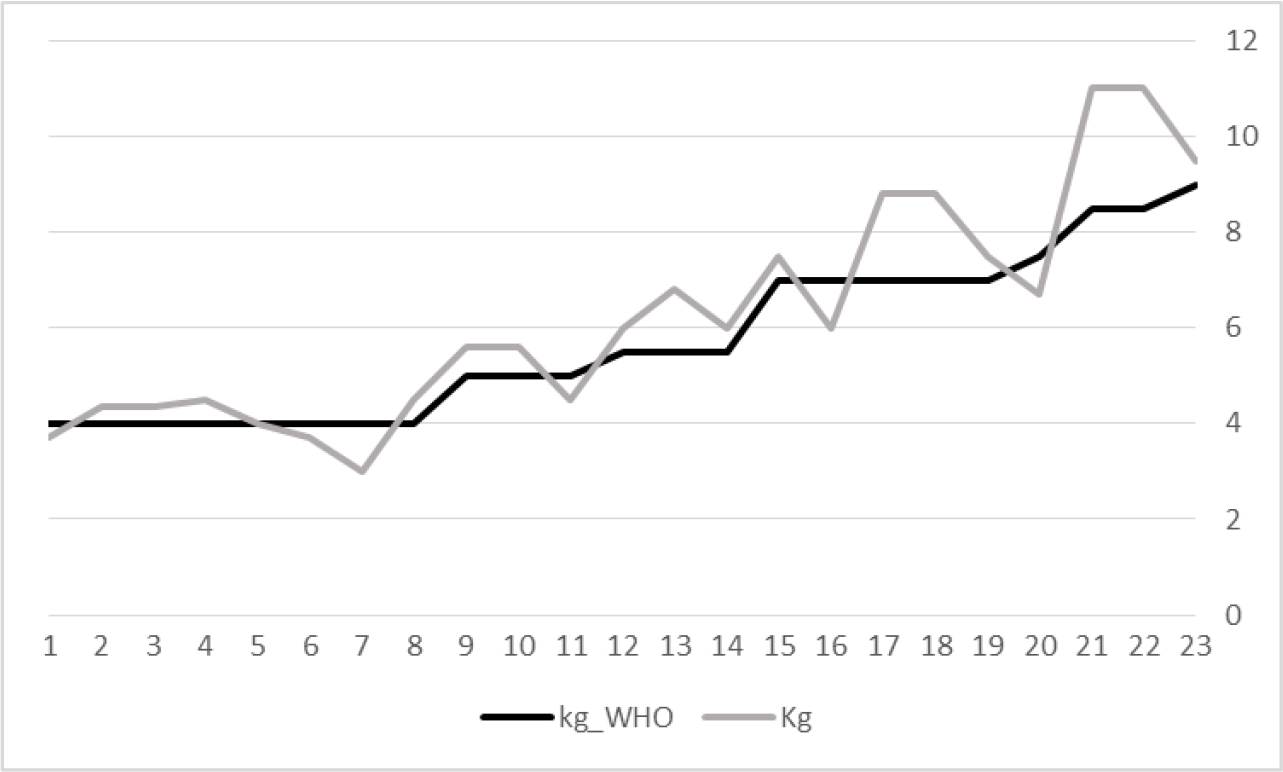

The Water Vapour Transmission Rate (WVTR) was assessed over a period of three weeks and seems to show a slight decrease with increasing nanoparticle concentration (Fig. 6). In literature, this is connected to tortuous pathway theory, predicting a greater effective water vapour diffusion length with nanoparticle incorporation [34, 35], although it should be kept in mind that the amounts of particles used are very low, and that other effects may have played a role.

Figure 6. Water vapour transmission rate measured at 20.0 °C, and 45 % relative humidity, for films -with different nano- chitin concentration. The solid dots indicate samples containing PLA and 20%plasticizer. The open squares indicate samples without plasticizer.

The films prepared at low nChit concentration (0.5 wt%), had significantly higher water vapour transmission rate compared to films containing 1 or 3% nChit (p<0.05). Research carried out elsewhere, found no significant effect on WVTR upon 1% nChit addition to PLA [17], hence the results presented in the current paper are favourable. We were aware of the negative effects connected to PLA hydrolysis, and adjusted the fabrication method to bypass these effects.

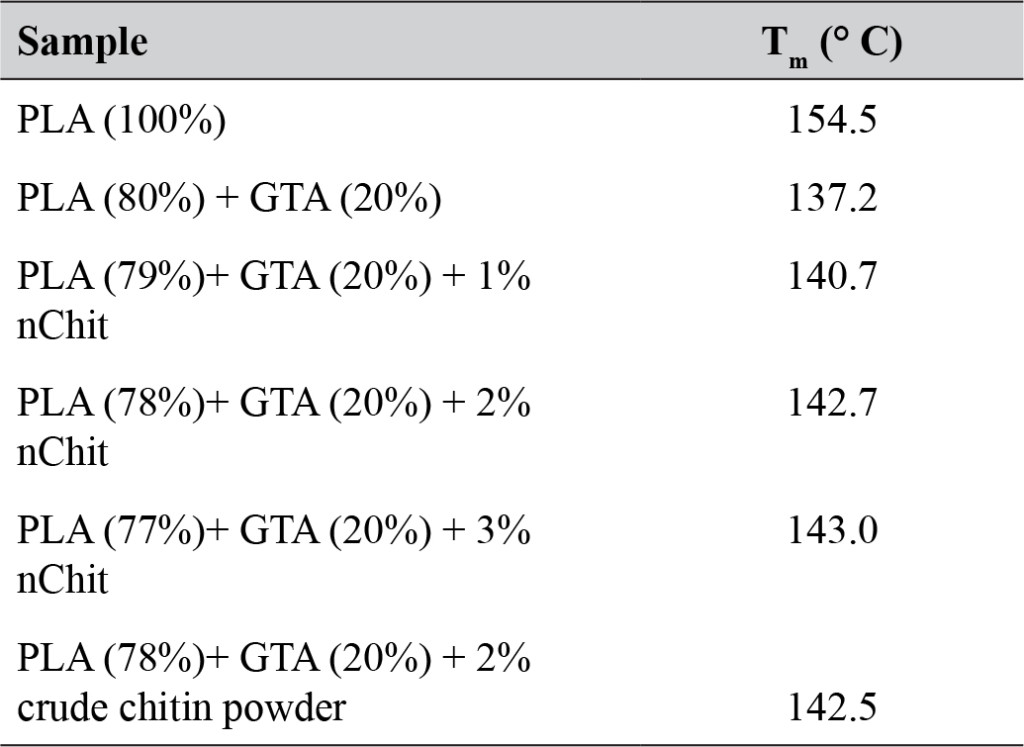

Thermal properties

The melting temperature (Tm) of the films decreased with addition of GTA, but increased slightly upon addition of nChit (Table 1).

Table 1. Melting temperature (Tm) of PLA films with added glycerin triacetate (GTA) and different percentages of chitin nanoparticles (nChit) or crude chitin powder.

Antimicrobial test

All kneader-prepared films in addition to a dried nChit flakes were subjected to a 24-hour agar diffusion test to assess antimicrobial activity. No inhibition zones were observed with any of the samples, which is in contrast to findings by others, who found a bacteriostatic effect of nano-chitin on Gram-negative bacteria [36] and a fungistatic effect on Aspergillus niger [37,38]. Most probably, the nano-chitin has very low mobility and solubility [39], and as diffusion is a prerequisite for antimicrobial effects this most probably did not occur, which in turn is positive news in regard to film integrity, and for application in food in which packaging material diffusion is mostly not appreciated.

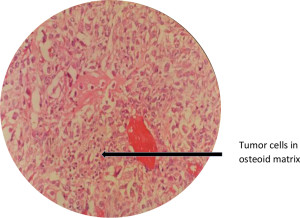

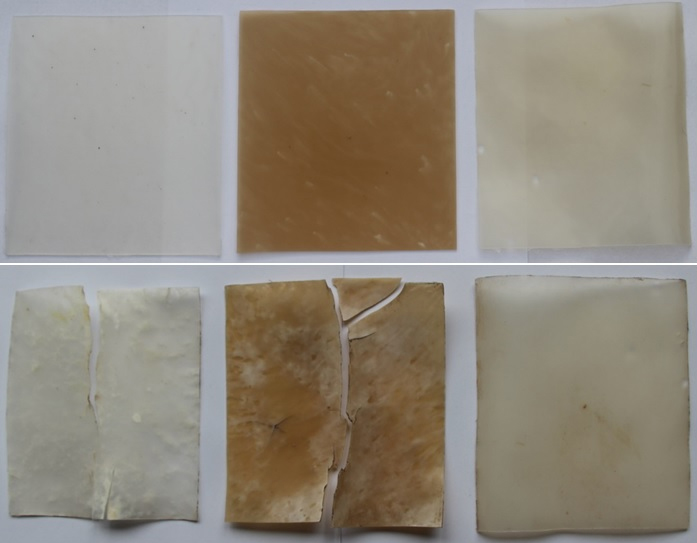

Biodegradability

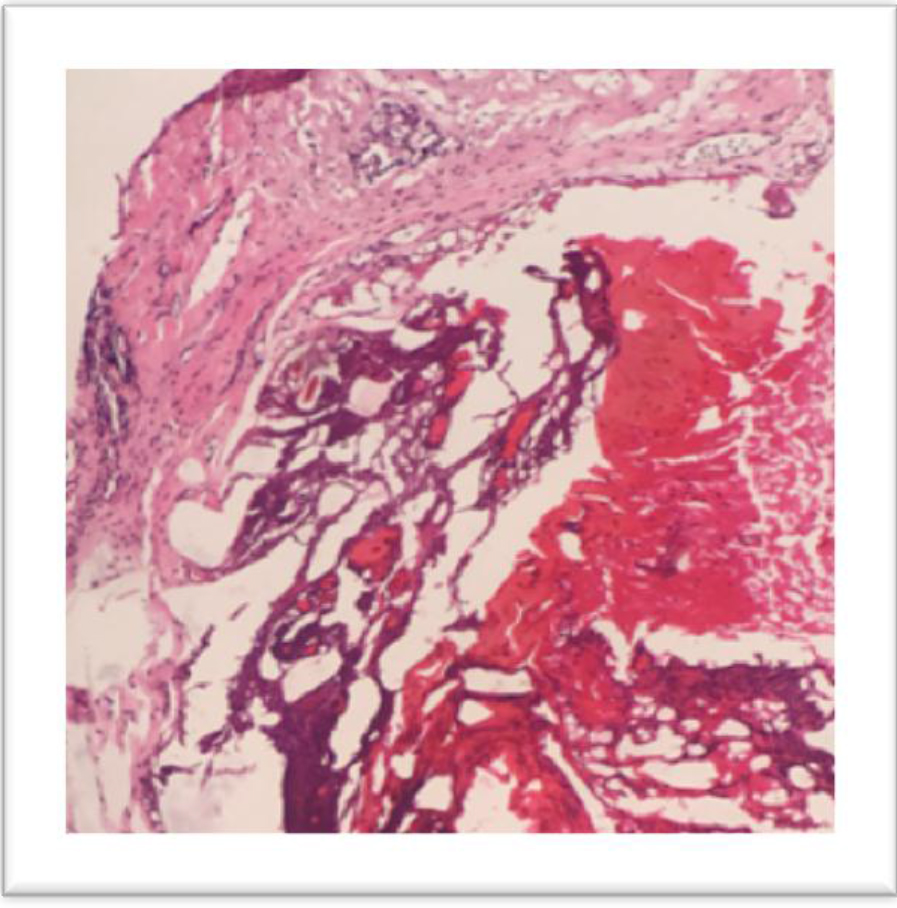

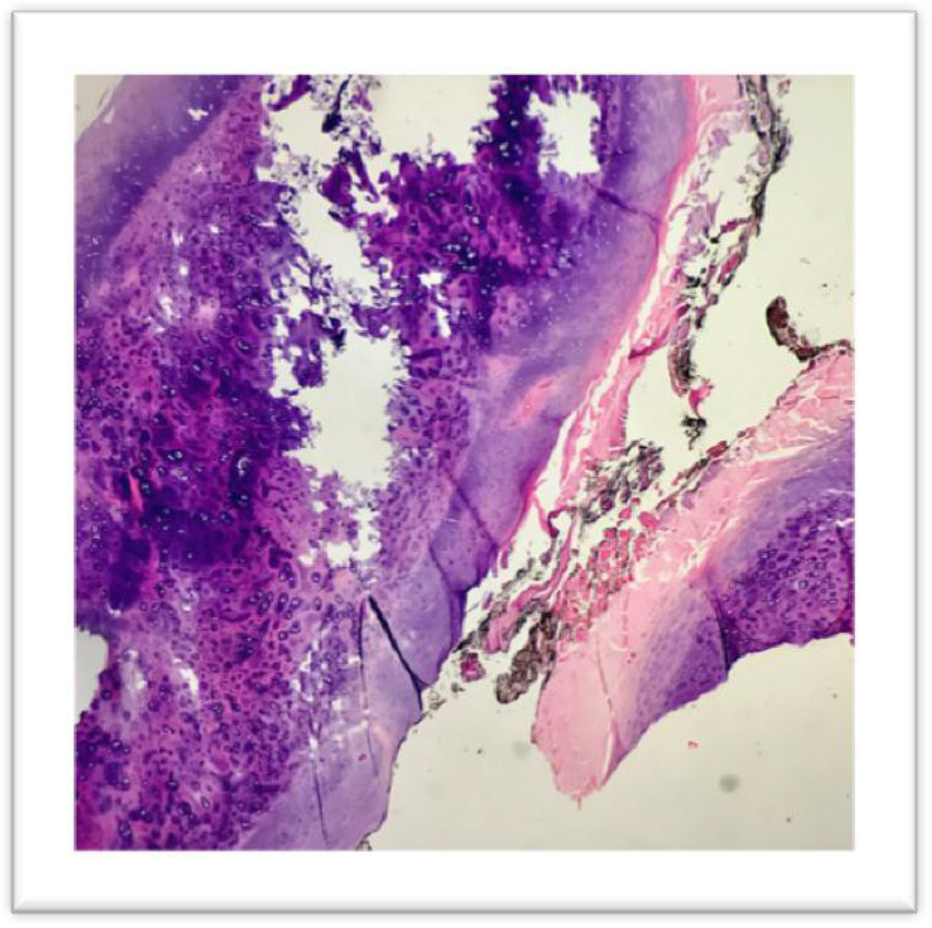

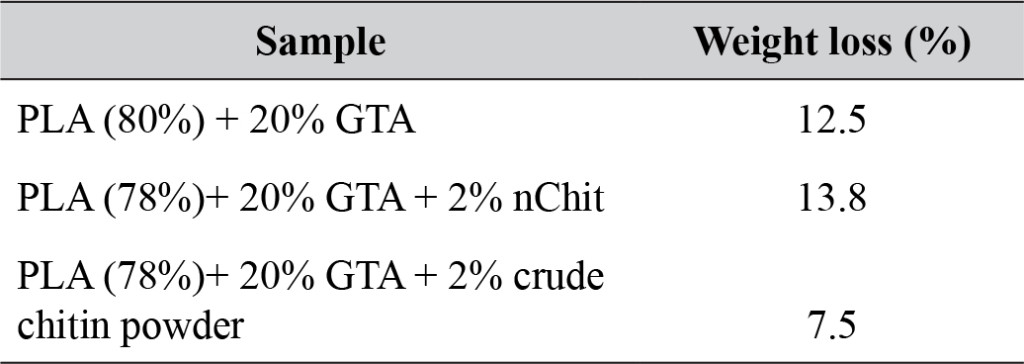

After 12 weeks in a compost heap, the plastic films showed weight reduction, discoloration, and breakage (Fig. 7, Table 2). The control (PLA+GTA), nChit composite and crude chitin powder composite showed 12.5%, 13.8% and 7.5% weight reduction respectively. In addition, the nChit film showed more discolouration and breakage compared to the other films, of which the crude chitin film showed highest integrity.

The exact mechanisms by which nanoparticles affect polymer biodegradation are poorly understood [39]. Fortunati et al (2014) [40] found an inhibiting effect of cellulose nanocrystals on PLA degradation, which was explained by increased crystallinity and decreased water diffusion. Calcium alginate composites with chitin nanowhiskers have shown accelerated biodegradation under in vitro conditions [41], which was attributed to the catalysing effect of hydroxyl groups [42], in which chitin is rich. It is clear these effects are of great relevance for practical application of nano-composite materials, and will decide the overall sustainability of the approach, which is part of follow-up research.

Figure 7. PLA films before and after 3 months in a compost heap. From left to right: PLA+GTA, PLA+GTA+2% nano-chitin, PLA+GTA+2% crude chitin powder.

Table 2. Weight loss of PLA films incorporated with 2 wt% (nano)chitin after 12 weeks of composting.

Economic and technical feasibility

From the previous sections, it is clear that PLA with chitin nanoparticles has promising properties, and the fact that we explored only proven technologies brings technical production closer. Whether this also holds for economic feasibility is to a large extent decided by consumer perception, which is discussed next, including a short outlook on technical feasibility.

Nowadays, conventional plastics are cheap due to the relatively low oil price, that is still recovering from a 10-year low of 27.96 dollars per barrel in February 2016 [43]. PLA producers find it difficult to compete against conventional plastic producers, as the costs of producing PLA are substantially higher. Nevertheless, the global demand for bioplastics packaging is expected to grow to over 2 million tons by 2020, with a compound annual growth rate of ~ 25% [1]. This growth can be explained by increased consumers’ awareness of the negative environmental impact of petrol-based plastics.

In the composite materials presented here, also nano-particles are present, and consumer’s attitude towards the application of nanotechnology in the food industry is somewhat ambiguous. According to Giles et al. (2015) [44] consumers find agri-food related nanotechnology acceptable when clear benefits could be identified and perceived benefits would outweigh perceived risks. Furthermore, they concluded that consumers are more likely to accept nanotechnology when it is used for food packaging compared to integration in food products. The additional production costs need to be covered by consumers’ willingness to pay more for biobased and biodegradable food packaging compared to petroleum-based packaging. This willingness has been confirmed in several studies and even reached 86% in Swedish consumers[45-47].

While production costs of PLA are higher, disposal costs are lower, since PLA can be industrially composted for around €45 per ton [48]. Common methods to process post-consumer petrol-based plastics waste are much more expensive; recycling does not take place because the costs transcend those of making new plastics [49]. Furthermore, costs of incineration and landfills reach and transcend €100 per ton due to taxes in Western and Northern Europe [48], whereas for Southern and Eastern Europe this is between zero and €60 [50]. This makes Western and Northern Europe a great market for biodegradable composites, where the quality of waste management is already high.

Regarding technical feasibility of the process, some comments need to be made. Although a considerable amount of ethanol is used in the process, this has been verified to be recyclable. Furthermore, high pressure homogenization can be considered since it has shown effective in obtaining chitin nanoparticles [51], and could even be more effective than the techniques used here. For both nanoparticle synthesis as well as film preparation, the necessary equipment such as stirring tank reactors, decanting centrifuges and extruders is proven technology on an industrial level [52], but compression moulding is not. Instead, film blowing can be used, which is even expected to better align the chitin whiskers within the PLA matrix, therewith positively affecting the permeability characteristics.

Conclusions

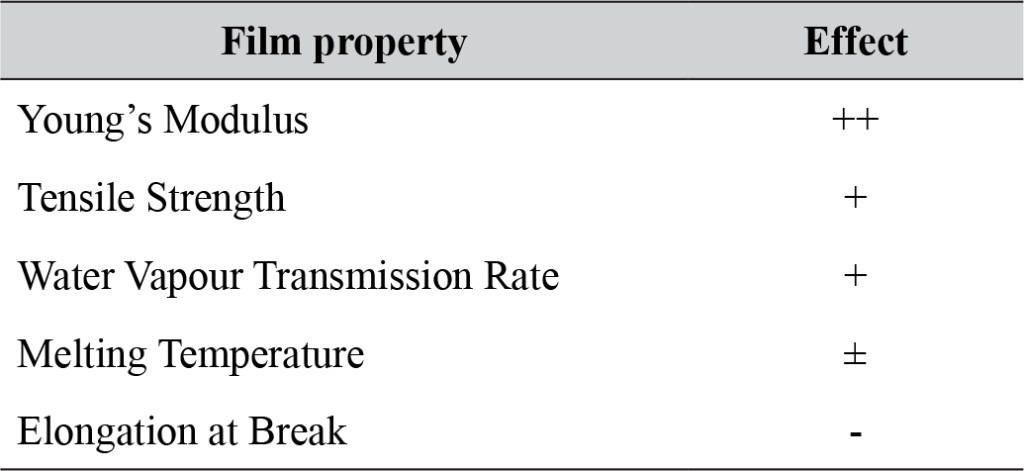

The nanocomposite biodegradable plastics presented in this paper mostly compare favourably to PLA-films without nano-chitin (table 3). The novel production method based on ethanol prevents PLA hydrolysis, which has greatly contributed to the positive effects that were found. In principle, the approach can technically be carried out at larger scale, and consumer perception seems to be boosting the bioplastics market which helps tackling socio-environmental challenges.

Table 3. Summary ofproperties of PLA films with GTA and nChit compared to PLA films with GTA. + + : consistent improvement with increasing nChit concentration, +: general improvement, ±: no significant change, -: general decline.

Authorship

Layla Broers, Sjoerd van Dongen, Veerle de Goederen, Marijn Ton, and Joep Spaen all contributed to the conception and design of the study. The first three authors contributed in data collection, interpretation, and analysis. The first four authors contributed in writing of the article. The last three mentioned authors contributed significantly in article revision. All authors approved the final version of the article.

Acknowledgements

The authors like to thank: Guus Frissen, Herman de Beukelaer, Sharon Chu, Jos Sewalt and Maurice Strubel who helped out during the practical work in the laboratories of FBR and the FPE group, and Frans Kappen, who assisted us in the Innovation Plant. Mieke Kleijn and Jacqueline Donkers, who helped us with AFM and SEM measurements. Philippe Puylaert, who provided material to perform antimicrobial tests. Peter de Goederen, who provided space and materials for biodegradation tests. Corbion for providing the polylactic acid.

This research was financially supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), through a Top Sector Chemistry Student Competition 2016 grant (700.001.516.56.11). There were no conflicts of interest.

List of abbreviations

Materials

nChit Nano-chitin

GTA Glycerol triacetate (plasticizer)

PLA Polylactic acid

Tests

AMT Anti-Microbial Test

EAB Elongation at Break

TS Tensile Strength

WVTR Water Vapor Transmission Rate

YM Young’s Modulus

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding information: This research was financially supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), through a Top Sector Chemistry Student Competition 2016 grant (700.001.516.56.11). There were no conflicts of interest and no involvement in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

References

- Smithers Pira (2015) The Future of Bioplastics for Packaging to 2020.

- Weiss M, Haufe J, Carus M, et al. (2012) A Review of the Environmental Impacts of Biobased Materials. J Ind Ecol 16: S169–81.

- Madhavan Nampoothiri K, Nair NR, John RP (2010) An overview of the recent developments in polylactide (PLA) research. Bioresour Technol 101: 8493–8501. [crossref]

- Webb HK, Arnott J, Crawford RJ, et al. (2013) Plastic degradation and its environmental implications with special reference to poly(ethylene terephthalate). Polymers (Basel) 5: 1–18.

- Reddy MM, Vivekanandhan S, Misra M, et al. (2013) Biobased plastics and bionanocomposites: Current status and future opportunities. Prog Polym Sci 38: 1653–89.

- Tjong SC. Structural and mechanical properties of polymer nanocomposites. Mater Sci Eng 15.

- Muzzarelli R, Jeuniaux C, Gooday GW (1986) Chitin in Nature and Technology. New York Springer US.

- Dutta PK, Duta J, Tripathi VS. Chitin and Chitosan: Chemistry, properties and applications. J Sci Ind Res (India) 63: 20–31.

- Singh DK, Ray AR (2000) Biomedical Applications of Chitin, Chitosan, and Their Derivatives. J Macromol Sci Part C Polym Rev 40: 69–83.

- Marchessault RH, Morehead FF, Walter NM (1959) Liquid Crystal Systems from Fibrillar Polysaccharides. Nature 184: 632–3.

- Yan N, Chen X (2015) Sustainability: Don’t waste seafood waste. Nature 524: 155–157. [crossref]

- Cordeiro de Azeredo HM, Mattoso LHC, Mchugh TH (2011) Nanocomposites in Food Packaging – A Review. In: Advances in Diverse Industrial Applications of Nanocomposites. InTech 57–78.

- Mincea M, Negrulescu A, Ostafe V (2012) Preparation, modification, and applications of Chitin Nanowhiskers: A Review. Rev Adv Mater Sci 30: 225–42.

- Stenmark A, Jensen C, Quested T (2016) IVL-report C 186: Estimates of European food waste levels. Stockholm

- Mukherjee T, Kao N (2011) PLA Based Biopolymer Reinforced with Natural Fibre: A Review. J Polym Environ 19: 714–25.

- Wahit MU, Akos NI, Laftah WA (2012) Influence of natural fibers on the mechanical properties and biodegradation of poly(lactic acid) and poly(å-caprolactone) composites: A review. Polym Compos 33: 1045–53.

- Herrera N, Roch H, Salaberria AM, et al. (2016) Functionalized blown films of plasticized polylactic acid/chitin nanocomposite: Preparation and characterization. Mater Des 92: 846–52.

- Itävaara M, Karjomaa S, Selin JF (2002) Biodegradation of polylactide in aerobic and anaerobic thermophilic conditions. Chemosphere 46: 879–885. [crossref]

- Revol JF, Marchessault RH (1993) In vitro chiral nematic ordering of chitin crystallites. Int J Biol Macromol 15: 329–335. [crossref]

- Rhim JW, Hong SI, Park HM, Ng PK (2006) Preparation and characterization of chitosan-based nanocomposite films with antimicrobial activity. J Agric Food Chem 54: 5814–5822. [crossref]

- Fernandez-Saiz P, Ocio MJ, Lagaron JM (2010) Antibacterial chitosan-based blends with ethylene– vinyl alcohol copolymer. Carbohydr Polym 80: 874–84.

- Lv YM, Laborda P, Huang K, et al. (2017) Highly efficient and selective biocatalytic production of glucosamine from chitin. Green Chem 19: 527–35.

- Oyaizu M (1986) Studies on Products of Browning Reaction Antioxidative Activities of Products of Browning Reaction Prepared from Glucosamine. Japanese J Nutr Diet 44: 307–15.

- Xavier M (2006) Standardization of Optimum Conditions for the Production of Glucosamine Hydrochloride from Chitin.

- Auras R, Harte B, Selke S (2004) An overview of polylactides as packaging materials. Macromol Biosci 4: 835-864. [crossref]

- Tian F, Decker EA, Goddard JM (2013) Controlling lipid oxidation of food by active packaging technologies. Food Funct 4: 669–680. [crossref]

- Murariu M, Da Silva Ferreira A, Alexandre M, et al. (2008) Polylactide (PLA) designed with desired end-use properties: 1. PLA compositions with low molecular weight ester-like plasticizers and related performances. Polym Adv Technol

- Fortunati E, Armentano I, Zhou Q, et al. (2012) Microstructure and nonisothermal cold crystallization of PLA composites based on silver nanoparticles and nanocrystalline cellulose. Polym Degrad Stab 97: 2027–36.

- Armentano I, Bitinis N, Fortunati E, et al. (2013) Multifunctional nanostructured PLA materials for packaging and tissue engineering. Prog Polym Sci 38: 1720–47.

- El-Hadi AM (2017) Increase the elongation at break of poly (lactic acid) composites for use in food packaging films. Sci Rep 7: 46767. [crossref]

- Nair KG, Dufresne A (2010) Crab Shell Chitin Whisker Reinforced Natural Rubber Nanocomposites.

- Ebadi-Dehaghani H, Khonakdar HA, Barikani M, et al. (2015) Experimental and theoretical analyses of mechanical properties of PP/PLA/clay nanocomposites. Compos Part B Eng 69: 133–44

- MatWeb L (2016) Overview of materials for Low Density Polyethylene (LDPE), Film Grade. MatWeb Mater. Prop. Data.

- Peelman N, Ragaert P, De Meulenaer B, et al. (2013) Application of bioplastics for food packaging. Trends Food Sci Technol 32: 128–41.

- Duncan T V (2011) Applications of nanotechnology in food packaging and food safety: Barrier materials, antimicrobials and sensors. J Colloid Interface Sci 363: 1–24.

- Benhabiles MS, Salah R, Lounici H, et al. (2012) Antibacterial activity of chitin, chitosan and its oligomers prepared from shrimp shell waste. Food Hydrocoll 29: 48–56.

- Herrera N, Roch H, Salaberria AM, et al. (2015) Functionalized blown films of plasticized polylactic acid/chitin nanocomposite: Preparation and characterization. Mater Des 92: 846–52.

- Salaberria AM, Diaz RH, Labidi J, et al. (2014) Role of chitin nanocrystals and nanofibers on physical, mechanical and functional properties in thermoplastic starch films. Food Hydrocoll 2015;46: 93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2014.12.016

- Souza VGL, Fernando AL (2016) Nanoparticles in food packaging: Biodegradability and potential migration to food—A review. Food Packag Shelf Life 8: 63–70.

- Fortunati E, Luzi F, Puglia D, et al. (2014) Investigation of thermo-mechanical, chemical and degradative properties of PLA-limonene films reinforced with cellulose nanocrystals extracted from Phormium tenax leaves. Eur Polym J 56: 77–91.

- Watthanaphanit A, Supaphol P, Tamura H, et al. (2008) Fabrication, structure, and properties of chitin whisker-reinforced alginate nanocomposite fibers. J Appl Polym Sci.

- Ray SS, Yamada K, Okamoto M, et al. (2003) New polylactide-layered silicate nanocomposites. 2. Concurrent improvements of material properties, biodegradability and melt rheology. Polymer (Guildf) 44: 857–66.

- UK Exchange Rates (2017) Crude Oil Price History.

- Giles EL, Kuznesof S, Clark B, et al. (2015) Consumer acceptance of and willingness to pay for food nanotechnology: a systematic review. J Nanoparticle Res 17: 467.

- Koutsimanis G, Getter K, Behe B, et al. (2012) Influences of packaging attributes on consumer purchase decisions for fresh produce. Appetite 59: 270–80.

- Lindh H, Olsson A, Williams H (2016) Consumer Perceptions of Food Packaging: Contributing to or Counteracting Environmentally Sustainable Development? Packag Technol Sci 29: 3–23.

- Rokka J, Uusitalo L (2008) Preference for green packaging in consumer product choices – Do consumers care? Int J Consum Stud 32: 516–25.

- Hogg D, Favoino E, Nielsen N, et al. (2002) Economic Analysis of Options for Managing Biodegradable Municipal Waste – Final Report. Bristol.

- PlasTech (2016) Current prices of polymers in Central Europe by method Plastixx. PlasticPortal.eu.

- FhG-IBP (Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der angewandten Forschung e.V).(2014) D 2.2 Waste Profiling.

- Salaberria AM, Fernandes SCM, Diaz RH, et al. (2015) Processing of á-chitin nanofibers by dynamic high pressure homogenization: Characterization and antifungal activity against A. niger. Carbohydr Polym 116: 286–91.

- Deeslie WD, Cheryan M (1981) A CSTR-hollow fiber system for continuous hydrolysis of proteins. Performance and kinetics. Biotechnol Bioeng 23: 2257–71.