DOI: 10.31038/CST.2017274

Abstract

For over 40 years, natural products have served us well in combating cancer. The main sources of these successful compounds are microbes and plants from the terrestrial and marine environments. The microbes serve as a major source of natural products with anti-tumor activity. A number of these products were first discovered as antibiotics. Another major contribution comes from plant alkaloids, taxoids and podophyllotoxins. A vast array of biological metabolites can be obtained from the marine world, which can be used for effective cancer treatment. The search for novel drugs is still a priority goal for cancer therapy, due to the rapid development of resistance to chemotherapeutic agents. In addition, the high toxicity usually associated with some cancer chemotherapy drugs and their undesirable side-effects increase the demand for novel anti-tumor drugs active against untreatable tumors, with a favorable safety profile and/or with greater therapeutic efficacy. This review points out those technologies needed to produce the anti-tumor compounds of the future.

Keywords

Natural products, anti-cancer, plant, marine, angiogenesis, tumor

Introduction

Natural products have offered tremendous benefits to our society as a whole. Not only have these compounds helped reduce pain and suffering but also enabled the transplantation of vital organs. The use of plant and microbial secondary metabolites has aided in doubling of our life span in the 20th century. Since their chemical diversity is based on biological and geographical diversity, the entire globe is explored for bioprospecting by researchers. Researchers have had easy access to terrestrial life from which most of the pharmaceutically successful natural products originate. However, the ocean hosts a vast repertoire of life forms brimming with natural products of potential pharmaceutical importance. New methods are being developed to grow the so-called ‘unculturable’ microbes from both the soil and the sea. Most biologically active natural products are secondary metabolites with complex structures. In some cases, the natural product itself can be used, but in others, derivatives made chemically or biologically are the molecules used in medicine. Biosynthetic pathways are often genetically manipulated to yield the desired product. With the advent of combinatorial biosynthesis, thousands of new derivatives can now be made by this biological technique, which is complementary to combinatorial chemistry.

The production of specialized compounds via secondary metabolism emerged as a result of the pressures (needs and challenges) from the natural environment. Nature has been continually carrying out its own version of combinatorial chemistry [1] for over the three billion years in which bacteria have inhabited the earth [2]. During that time, there has been an evolutionary process going on in which producers of secondary metabolites evolved according to their local environments. If the metabolites were useful to the producing species, the biosynthetic genes were retained and genetic modifications further improved the process. Combinatorial chemistry practiced by nature is much more sophisticated than combinatorial chemistry in the laboratory, yielding exotic structures rich in stereochemistry, concatenated rings and reactive functional groups [1]. As a result, an amazing variety and number of products have been found in nature. This natural wealth is tapped for drug discovery using high-throughput screening and fermentation, mining genomes for cryptic pathways, and combinatorial biosynthesis to generate new secondary metabolites related to existing pharmacophores. The success of the pharmaceutical industry depends on the combination of complementary technologies such as natural product discovery, high-throughput screening, genomics, proteomics, metabolomics and combinatorial biosynthesis.

Of the nearly one million natural products currently known, it is estimated that about half (500,000 – 600,000) are produced by plants [3-4]. The structures of 160,000 natural products were already elucidated by the late 1990s, a value growing by 10,000 per year [5]. There are more than 20,000 microbial secondary metabolites [6]. With regard to biological activity, there are about 200,000 to 250,000 biologically active products (active and/or toxic). About 100,000 secondary metabolites of molecular weight less than 2500 Daltons have been characterized. About half are produced by microbes and the other half by plants [3, 7-9].

Many natural products from terrestrial sources have been successful in clinical trials and have greatly benefited the medical field, some for nearly half a century. Over 60% of approved and pre-NDA (New Drug Applications) candidates are either natural products or related to them, not including biologicals such as vaccines and monoclonal antibodies [10-11]. 6% are natural products, 27% are derivatives of natural products, 5% are synthetic with natural product pharmacophores, and 23% are synthetic mimics of natural products. Almost half of the best-selling pharmaceuticals are natural or are related to natural products. In 2008, there were 225 natural product-based drugs in various testing procedures such as preclinical, clinical phases I to III, and preregistration. [12] Of these, 108 were from plants, 61 were semi-synthetic, 25 were from bacteria, 24 were from animals and 7 were fungal in origin. Of the 18,000 known marine natural products, 22 of these or their chemical derivatives have been in clinical trials.

The approximate number of known isoprenoids (including terpenoids and carotenoids) is 50,000 [13]. Terpenes number 30,500 and as pharmaceuticals, they had a market of $12 billion in 2002 [14-15]. Other major categories include polyketides, including macrolides, non-ribosomal peptides, etc. About 4,000 of the known natural products are halogenated.

Cancer is a complex group of diseases which is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality. In 2016, 1,685,210 new cases of cancer were diagnosed in the USA, of which 595,690 will result in death [16]. Natural products are the most important anti-cancer agents. Three quarters of anti-tumor compounds used in medicine are natural products or related to them. Of the 140 anti-cancer agents approved since 1940 and available for use, over 60% can be traced to a natural product. Of the 126 small molecules among them, 67% are natural in origin [17]. In 2000, 57% of all drugs in clinical trials for cancer were either natural products or their derivatives [18]. From 1981 to 2002, natural products were the basis of 74% of all new chemical entities for cancer. Of the 225 natural product-based drugs in various stages of clinical testing in 2008 mentioned above, [12] the therapeutic categories targeted included 86 for cancer.

A list of compounds which possess anti-neoplastic activity belong to several different structural classes, which include anthracyclines, enediynes, indolocarbazoles, isoprenoids, polyketide macrolides, non-ribosomal peptides (such as glycopeptides), and others. Most of the polyketides are produced by bacteria and fungi [19-20]. They include a number of anti-tumor drugs such as taxol, which is made by both plants and fungi. Halogenated anti-tumor candidates include salinosporamide A and rebeccamycin [21].

The anti-cancer compounds exert their activity through a diverse array of mechanisms. These include inducing apoptosis through DNA cleavage mediated by topoisomerase I or II inhibition, inhibition of critical enzymes involved in signal transduction or cellular metabolism, mitochondrial permeabilization, and inhibition of tumor-induced angiogenesis.

Anti-cancer compounds from microbes

A significant number of compounds with anti-neoplastic activity are natural products, having been produced by microorganisms. In particular, actinomycetes are the producers of a large number of natural products with anti-tumor properties, many of which also have anti-microbial activity. A broad screening of antibiotically-active molecules for antagonistic activity against organisms other than microorganisms was proposed in the 1980s in order to yield new and useful lives for ‘failed antibiotics’. This resulted in the development of a large number of simple in vitro laboratory tests, e.g. enzyme inhibition screens [22-23] to detect, isolate and purify useful compounds. As a result, we entered into a new era in which microbial metabolites were applied to diseases heretofore only treated with synthetic compounds, and much success was achieved. One such area was that of anti-tumor agents.

Newman and Shapiro made the point that microorganisms have been quite useful in the identification of products with therapeutic efficacy against cancer, based on their ability to prescreen anti-tumor compounds [24]. Most of the important compounds used for chemotherapy of tumors are microbially-produced antibiotics or their derivatives. One of the earliest applications of a microbial product was actinomycin D for Wilm’s tumor in children. Use of this compound against stage I or stage II Wilm’s tumor resulted in a 90% survival rate [25]. Also used for anti-tumor therapy is the enzyme L-asparaginase.

Bleomycin, which is used for the treatment of squamous cell carcinomas, Hodgkin’s lymphomas, and testes tumors, is a glycopeptide produced by Streptoalloteichus hindustanus. A derivative of the bleomycin family, pingyangmycin, has been used in cancer therapy in China since 1978 [26]. Another bleomycin derivative, Blenoxane, is used clinically with other compounds against lymphomas, skin carcinomas and tumors of the head, neck and testicles [27].

Derivatives (analogs) can be made chemically or through the alteration of fermentation conditions. For example, addition of KBr to the rebeccamycin producer, Saccharothrix aerocolonigenes, yielded a brominated rebeccamycin.[28] Addition of DL-fluorotryptopan yielded two new fluorinated rebeccamycins and addition of DL-fluorotryptophan led to a third.[29] Of interest are the rebeccamycin derivative edotecarin and the geldanomycin derivative 17-allylaminogeldanomycin. Interestingly, a fourth-generation tetracycline known as SF 2575, produced by Streptomyces sp., has low antibiotic activity but a high level of activity against P388 leukemia cells in vitro, and many other types of cancer cells [30] . It appears to act against DNA topoisomerases I and II, the target of camptothecins and doxorubicin, respectively.

Metastatic testicular cancer represents a compelling example of how natural products can be used to effectively cure this disease. Although this type of cancer was responsible for only 1% of male malignancies in the USA, it did cause 80 000 cases in the year 2000. Indeed, it is the most common carcinoma in men aged 15–35. The cure rate for disseminated testicular cancer was 5% in 1974; later it was 90%, mainly due to the use of a triple combination of the microbial product bleomycin, the plant compound etoposide, and the synthetic agent cisplatin [31].

Anthracyclines

The anthracyclines are perhaps the most widely-recognized anti-cancer agents, notably daunorubicin (daunomycin), doxorubicin (14-hydroxydaunorubicin), adriamycin, carminemycin, and aclarubicin [32]. By cloning the doxorubicin resistance gene and the aklavinone 11-hydroxylase gene dnrF from Streptomyces peucetius spp. caesius (doxorubicin producer) into the aclacinomycin A producer, a novel anthracycline, 11-hydroxyaclacinomycin A, was made [33]. The hybrid molecule showed greater activity against leukemia and melanoma than aclacinomycin A. Another hybrid molecule produced was 2’-amino-11-hydroxyaclacinomycin Y, which is highly active against tumors [34]. Additional anthracyclines have been made by introducing DNA from Streptomyces purpurascens into Streptomyces galilaeus, both of which normally produce known anthracyclines [35]. Other novel anthracyclines were produced by cloning DNA from the nogalomycin producer, Streptomyces nogalater, into Streptomyces lividans and into an aclacinomycin-negative mutant of S. galilaeus [36]. Cloning of the actI, actIV and actVII genes from Streptomyces coelicolor into the 2-hydroxyaklavinone producer, S. galilaeus 31671, yielded the novel hybrid metabolites, desoxyerythrolaccin and 1-O-methyl-desoxyerythrolaccin [37]. Similar studies yielded the novel metabolite aloesaponarin II [38]. Epirubicin (4¢-epidoxorubicin) is a semi-synthetic anthracycline with less cardiotoxicity than doxorubicin [39]. Genetic engineering of a blocked S. peucetius strain provided a new method to produce it [40]. The gene introduced was avrE of the avermectin-producing Streptomyces avermitilis or the eryBIV genes of the erythromycin producer, Saccharopolyspora erythrea. These genes and the blocked gene in the recipient are involved in deoxysugar biosynthesis.

Enediynes

Enediynes are one of the most potent anti-neoplastic compounds produced naturally, but are quite toxic due to their induction of apoptosis in both normal and cancerous cells. They include calicheamicin, dynemicin A, esparamicin, kerdarcidin and neocarzinostatin. Scientists have tried to design non-toxic enediyne-based anti-tumor drugs [41]. Progress towards this goal has proceeded by merging amidines with the natural enediyne, dynemicin A [42].

Epothilones

Myxobacteria, which are somewhat large Gram-negative rods whose primary means of locomotion is by gliding or creeping, provide an unexpected source of secondary metabolites. They form fruiting bodies and have a very diverse morphology. Over 400 compounds had been isolated from these organisms by 2005, but the first in clinical trials were the epothilones, potential anti-tumor agents, which act like taxol (see Plant anti-tumor agents below) but are active against taxol-resistant tumors [43]. Epothilones are 16-member ring polyketide macrolide lactones produced by the myxobacterium Sorangium cellulosum, which were originally developed as anti-fungal agents against rust fungi [44-45] but have found their use as anti-tumor compounds. They contain a methylthiazole group attached by an olefinic bond. They are active against breast cancer and other forms of cancer [46]. They bind to and stabilize microtubules essential for DNA replication and cell division, even more so than taxol. One epothilone, ixebepilone (Ixempra), produced chemically from epothilone B and which targets microtubules, was approved by FDA. By preventing the disassembly of microtubules, epothilones cause arrest of the tumor cell cycle at the GM2/M phase and induce apoptosis. The mechanism is similar to that of taxol but epothilones bind to tubulin at different binding sites and induce microtubule polymerization. Production of epothilone B by S. cellulosum is accompanied by the undesirable epothilone A. Production of epothilone B over A is favored by adding sodium propionate to the medium. Epothilone polyketides are more water-soluble than taxol. The epothilone gene cluster was cloned, sequenced, characterized and expressed in the faster growing Streptomyces coelicolor, resulting in the production of epothilones A and B [47-48].

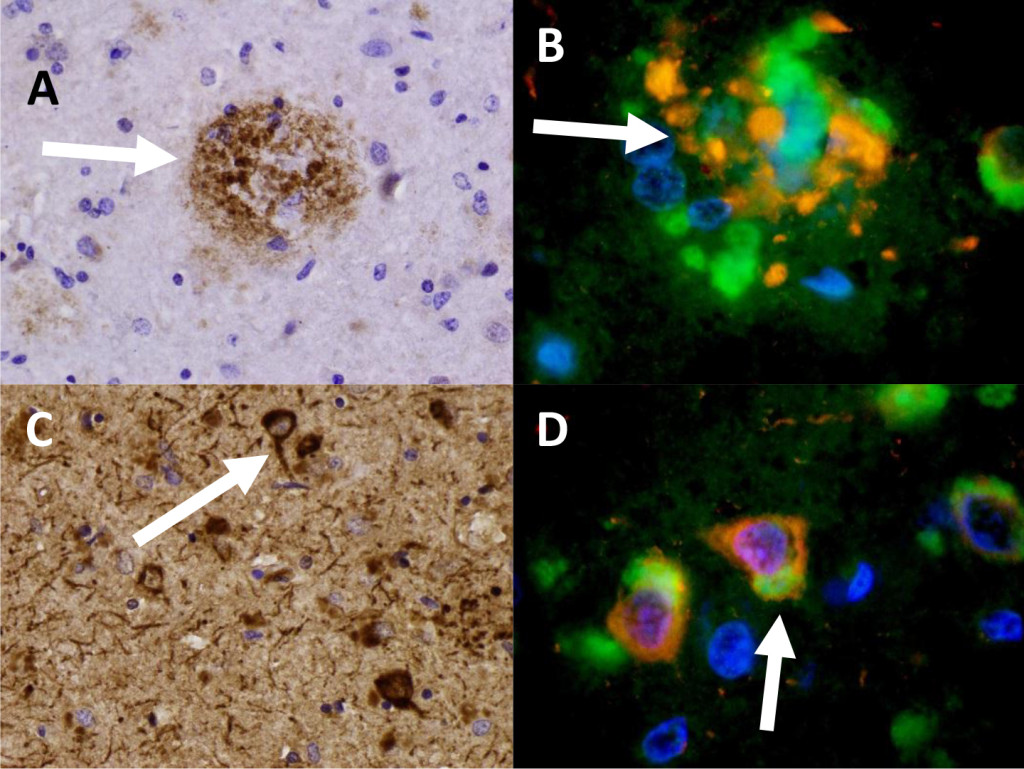

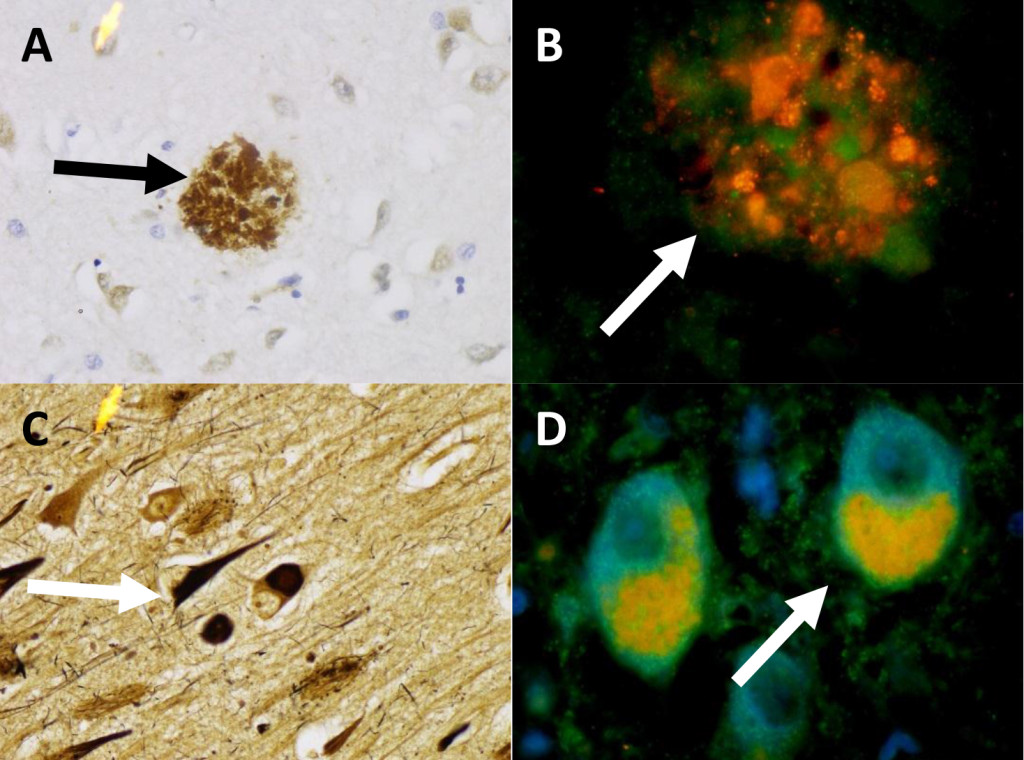

Agents which target angiogenesis

Tumors rely heavily on angiogenesis, which is the production of new blood vessels, in order to get their oxygen and nutrients. Tumors actively secrete growth factors, which trigger angiogenesis. The concept of angiogenesis was established by Professor Judah Folkman [49]. He proposed that tumor growth depends on angiogenesis and proposed the use of angiogenesis inhibitors as anti-tumor agents, i.e. to target activated endothelial cells. He further proposed that the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is involved in angiogenesis and that it could be a target for anti-angiogenic drugs. Fumagillin, produced by Aspergillus fumigatis, was one of the first agents found to act as an anti-angiogenesis compound. Next to come along were its oxidation product ovalacin and the fumagillin analog TNP470 (= AGM-1470).[50-51] TNP470 binds to and inhibits type 2 methionine aminopeptidase (MetAP2) [52-53]. This interferes with amino-terminal processing of methionine, which may lead to inactivation of enzymes essential for growth and migration of endothelial cells [54-55]. In animal models, TNP470 effectively treated many types of tumors and metastases [56-58].

Avastin (bevacizumab), which is a monoclonal antibody and angiogenesis inhibitor, is a first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. Anti-angiogenic agents Pegaptanib (Macugen) and ranibizumab (Lucentis) were approved by FDA. Macugen is an aptomer of the VEGF and Lucentis is an anti-VEGF antibody. By the end of 2007, 23 anti-angiogenic drugs were in Phase III clinical trials and more than 30 were in Phase II. By 2008, ten anti-angiogenesis drugs had been approved. Eight are used against cancer and two are employed for treatment of age-related macular degeneration. Anti-angiogenesis therapy is now known as one of the four major types of cancer treatment.

Derivatives of Rapamycin (sirolimus)

Rapamycin is a polyketide anti-fungal agent with a limited spectrum of activity which first gained recognition as an immuno-suppressive agent commonly used for organ transplantation. Rapamycin’s mode of action is that of inhibiting the mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) phosphatidylinositol lipid kinase. Interestingly, it was also found to have anti-tumor activity [59] by interfering with angiogenesis [60-61] and inducing apoptosis. Rapamycin was the basis of chemical modification and these efforts yielded important products such as temsirolimus (CCI-779; (Torisel), everolimus and deforolimus (A23573) [62] Temsirolimus, an mTOR protein kinase inhibitor, was approved by the FDA for renal cell carcinoma [63].

Statins

The statins are essential for the reduction of cholesterol levels in humans specifically by targeting and inhibiting blood cholesterol, which is produced in the liver. They are microbially-produced enzyme inhibitors, inhibiting 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-coenzyme A reductase, the regulatory and rate-limiting enzyme of cholesterol biosynthesis in the liver. As a result, they are a leading group of pharmaceuticals. One of the most useful statins is lovastatin (monocolin K, mevinolin) produced by Monascus ruber [64] and Aspergillus terreus [65] Statins also have anti-cancer activity, i.e., they inhibit in vitro and in vivo growth of pancreatic tumors. They also sensitize tumors to cytostatic drugs such as gemcitabrine, which is used for pancreatic cancer [66] It has been shown that there is over a 50% reduction in risk of metastatic or fatal prostate cancer among people taking statins and an 80% reduction in pancreatic cancer among people using statins for 4 years. It has been found that lovastatin has anti-tumor activity against Lewis Lung Carcinoma cells [67].

The hunt for new and promising agents

Salinomycin was determined to be the most effective agent identified from high-throughput screening of 16,000 compounds for selective inhibition of cancer stem cells [68] In fact, it was 100 times more active than taxol. Salinomycin is used as a coccidiostat in poultry and in other livestock, and as an agent increasing feed efficiency in ruminant animals. Also active were etoposide, abamectin and nigericin. Both salinomycin and nigericin are structurally- related polyether potassium ionophores.

Modification of an organism’s genome offers a promising method to generate unique anti-tumor agents. This is carried out by expressing biosynthetic gene clusters from anti-tumor pathways in other organisms. This has resulted in the formation of some novel hydroxylated and glycosylated anti-tumor agents [69].

Following the discovery of the S. coelicolor genome, which contained 22 gene clusters encoding the production of secondary metabolites, the notion of genome mining was established. The technique is useful for identifying genetic units with potential for synthesizing new drugs and has yielded many new antibiotics and anti-tumor agents [70-72]. One anti-cancer compound developed by Thallion Pharmaceuticals is ECO-4601. It inhibits the Ras-mitogen-activated phosphokinase (MAPK) pathway and binds selectively to the PBR (peripheral benzodiazapine receptor), which is over-expressed in many types of tumors. As a result of genome mining with Micromonospora sp., a new anti-tumor drug was discovered [73]. The compound, ECO-04601, is a farnesylated dibenzodiazapene, which induces apoptosis.

Within the drainage of an abandoned mine, a co-culture yielded a compound with anti-neoplastic activity. The specific nutrient conditions in the mine likely contributed to an extreme environment [74]. Such an environment results in defensive and offensive microbial interactions for survival of microbes. The two members of the co-culture were the bacterium Sphingomonas sp. strain KMK-001, and the fungus A. fumigatus strain KMC-901. A diketopiperazine disulfide, glionitrin A, was isolated from the co-culture but was not detected in monoculture broths of KMK-001 or KMC- 901. Glionitrin A is a (3S, 10aS) diketopiperazine disulfide containing a nitro aromatic ring. It displayed significant antibiotic activity against a series of microbes including methicillin-resistant S. aureus. An in vitro MTT cytotoxicity assay revealed that it has potent sub-micromolar cytotoxic activity against four human cancer cell lines: HCT-116, A549, AGS and DU145.

Plant anti-tumor agents

Many promising anti-tumor compounds that have been approved are actually plant-derived [75]. Various groups are described below.

Alkaloids

The Madagascar periwinkle plant (Catharanthus roseus) is the source of vinca monoterpene indole alkaloids, such as vinblastine and vincristine. Vinblastine is commonly used to treat cancers such as Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Vinblastine and vincristine have important pharmacological activities but are synthetically challenging. Metabolic engineering of alkaloid biosynthesis can provide an efficient and environmentally friendly route to analogs of these pharmaceutically valuable natural products. The enzyme at the entry point of the pathway, strictosidine synthase, has a narrow substrate range and thus limits a pathway engineering approach. However, it was demonstrated by Bernhardt and colleagues [76] that with a different expression system and screening method, it is possible to rapidly identify strictosidine synthase variants that accept tryptamine analogs not utilized by the wild-type enzyme. The variants are used in a stereoselective synthesis of beta-carboline analogs and are assessed for biosynthetic competence within the terpene indole alkaloid pathway. These results presented an opportunity to explore metabolic engineering of ‘unnatural’ product production in the plant periwinkle.

Serpentines, which are also made by the Madagascar periwinkle plant, have demonstrated encouraging anti-cancer activity. Other plant-produced compounds have shown pharmacological activities including anti-cancer activity, but are too toxic for use in humans. However, researchers have been able to produce a range of halogenated alkaloids [77]. This strategy could help expand the range of available drug candidates for cancer.

Certain seed-producing plants (angiosperms) make camptothecin, a cytotoxic quinoline alkaloid [78] It also is produced by the endophytic fungus, Entrophospora infrequens, from the plant Nathapodytes foetida. In view of the low concentration of camptothecin in tree roots and poor yield from chemical synthesis, the fungal fermentation is very promising for industrial production. Camptothecin is used for recurrent colon cancer and has unusual activity against lung, ovarian, and uterine cancers [79]. Colon cancer is the second leading cause of cancer fatalities in the USA and the third most common cancer among US citizens. Camptothecin is known commercially as Camptosar and Campto and achieved sales of $1 billion in 2003 [80]. Camptothecin’s water-soluble derivatives irinotecan and topotecan are also used clinically.

Camptothecin exhibits its anti-cancer activity by inhibiting type 1 DNA topoisomerase. When patients become resistant to irinotecan, its use can be prolonged by combining it with the monoclonal antibody Erbitux (Cetuximab). Erbitux blocks a protein that stimulates tumor growth and the combination helps metastatic colorectal cancer patients expressing epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). This protein is expressed in 80% of advanced metastatic colorectal cancers. The drug combination reduces invasion of normal tissues by tumor cells and the spread of tumors to new areas.

The diterpene alkaloid, Taxol (paclitaxel), has shown great promise as an anti-cancer drug [81]. It was originally discovered in plants but was also found to be a fungal metabolite [82]. Fungi, such as Taxomyces adreanae, Pestalotiopsis microspora, Tubercularia sp. and Phyllosticta citricarpa, produce taxol [82-84]. Production by P. citricarpa is rather low, i.e. 265 µg l-1.[85] However, it is claimed that another fungus, Alternaria alternata var monosporus from the bark of Taxus yunanensis, after ultraviolet and nitrosoguanidine mutagenesis, produces taxol at the high level of 227 mg l-1 [86]. Originally isolated from the bark of the Pacific yew tree (Taxus brevifolia), taxol showed anti-tumor activity but it took six trees of 100 years of age to treat one cancer patient [87]. Later, it was produced by plant cell culture or by semi-synthesis from taxoids made by Taxus species. These species make more than 350 known taxoid compounds [88].

Taxadiene (the taxol precursor) was not able to be produced through the genetic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae due to the fact that only a small amount of the intermediate, geranylgeranyl diphosphate, was formed. When the Taxus canadensis geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase gene was introduced into S. cerevisiae,1 mg l-1 of taxadiene was obtained [81]. Later, metabolic engineering yielded a S. cerevisiae strain producing over 8 mg l-1 taxadiene and 33 mg l-1 of geranyl geraniol.

The technical means by which Taxol is made is dependent on the use of plant cells from Taxus chinensis. The addition of methyl jasmonate, a plant signal transducer, increased production from 28 to 110 mg l-1[89]. The optimum temperature for growth of T. chinensis is 24°C and that for taxol synthesis is 29°C. Shifting from 24°C to 29°C at 14 days gave 137 mg l-1 at 21 days [90]. Later, a 6-week process yielding 153 mg l-1 with T. chinensis, was developed [91]. Mixed cultures of Taxus plant cells and taxol-producing endophytic fungi were also examined [92].

Taxol, which inhibits depolymerization of microtubules and is approved for the treatment of breast and ovarian cancer, had sales of $1.6 billion in 2005. In addition, taxol promotes tubulin polymerization and inhibits rapidly dividing mammalian cancer cells [93]. Taxanes and camptothecins alone accounted for approximately one-third of the global anti-cancer market in 2002, with a market value of over $2.75 billion. An analog of taxol, docetaxel (Taxotere), had sales of $3 billion in 2009 [94].

Taxol also possesses anti-fungal activity against oomycetes via the same process of blocking the depolymerization of microtubules [95-96]. Oomycetes are water molds exemplified by plant pathogens, such as Phytophthora, Pythium and Aphanomyces.

Etoposide and teniposide

Two semi-synthetic derivatives of podophyllotoxin are etoposide and teniposide. Podophyllotoxin is actually an anti-mitotic metabolite of the plant, Podophyllum peltatam [97-98]. The mayapple plant is an old herbal remedy. Etoposide is a topoisomerase II inhibitor. This essential enzyme is involved in eukaryotic cell growth by regulating levels of DNA super-coiling [99]. Etoposide was approved for lung cancer, choriocarcinoma, ovarian and testicular cancer, lymphoma, and acute myeloid leukemia. Teniposide was approved for tumors of the central nervous system, malignant lymphoma and bladder cancer.

Other compounds

Cell culture of the plant Lithospermum erythrorhizon yields the naphthoquinone pigment, shikonin. Shikonin is a herbal medicine used mainly for cosmetic purposes. Unexpectedly, shikonin and two derivatives were found to inhibit tumor growth in mice bearing Lewis Lung Carcinoma [100]. Other plant natural products such as the isoflavone genistine, indole-3-carbinol (I3C), 3,3’-diindolemethane, curcumin (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate, resveratrol and lycopene are known to inhibit the growth of cancer cells [101]. These natural compounds appear to act by interference in multiple cellular signaling pathways, activating cell death signals, and inducing apoptosis of cancer cells without negatively affecting normal cells.

Anti-cancer products from the marine environment

The biological diversity of the ocean represents 34 of 37 phyla of life compared to 17 phyla on land. Because of this, searching marine environments and resources for the purpose of drug discovery is an endeavor of interest. Marine microorganisms encompass a complex and diverse assemblage of microscopic life forms, of which it is estimated that only 1% have been cultured or identified. Coral reefs and other highly diverse ecosystems, such as mangroves and sea grass, have been targeted for bioprospecting, because they host a high level of biodiversity and are often characterized by intense competition for space, leading to chemical warfare among sessile organisms. Marine sponges produce numerous bioactive compounds with promising pharmaceutical properties. Cytarabine (Cytostar), used for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, was originally derived from a sponge.[102] Sponges have been frequently hypothesized to contain compounds of bacterial origin and the bacterial symbionts have long been suspected to be the true producers of many drug candidates. A number of marine products have anti-tumor activity.

Paederus fuscipes beetles are host to an uncultured Pseudomonas sp. symbiont, which appears to be the most likely source of the defensive anti-cancer polyketide, pederin. Scientists were able to determine this based on cloning of the presumed biosynthetic genes. Closely related genes have also been isolated from the highly complex metagenome of the marine sponge Theonella swinhoei, which is the source of the onnamides and theopederins, a group of polyketides that structurally resemble pederin. Sequence features of the isolated genes clearly indicate that they may belong to a prokaryotic genome and are responsible for the biosynthesis of almost the entire portion of the polyketide structure that is correlated with anti-tumor activity. Besides providing further proof for the role of the related beetle symbiont-derived genes, these findings raise intriguing ecological and evolutionary questions and have important general implications for the sustainable production of otherwise inaccessible marine drugs by using biotechnological strategies [103].

Approximately 32% of the effective marine natural products are used for inflammation, pain, asthma, and Alzheimer’s disease, while the remaining 68% are used for cancer treatment. Global sales of marine biotechnology products including anti-cancer compounds exceeded $3.2 billion in 2007. The marine alkaloid trabectedin (Yondelis) was approved by the FDA [62]. A major problem in this field is that less than 1% of the commensal microbiotic consorta of marine invertebrates are culturable.

Curacin A was isolated from a marine cyanobacterium, Lyngbya majuscula in Curacao, and has demonstrated strong anti-cancer activity [104]. Other anti-tumor agents derived from marine sources include eleutherobin, discodermolide, bryostatins, dolastatins and cephalostatins.

Marine invertebrate animals are host to many different symbionts which are the source of compelling natural products [105]. Variants of the toxic dolastin from the sea hare Dolabella auricalaria seem promising against cancer. These include soblidofin (T2F 1027), against soft tissue sarcoma, and synthadotin (tasidotin, 1LX 651), against melanoma, prostate and non-small cell lung cancers. These are thought to be produced by cyanobacteria sequestered by the marine invertebrates in their diet.

In order to identify new and useful products with anti-cancer activity, there is a need to continue to explore the rich biological diversity of the marine environment [106]. The actinomycete genus Salinispora and its two species, Salinospora tropica and Salinospora arenicola, have been isolated around the world. These require seawater for growth. S. tropica makes a novel bicyclic gamma-lactone beta-lactam called salinosporamide A, which is a proteasome inhibitor [107] and has activity against multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma. Also, the genus Marinophilus contains species that produce novel polyenes, which have no anti-fungal activity but display potent anti-tumor activity.

Concluding remarks

To meet the growing demand for new anti-cancer compounds in the future, what is the best and most productive way to go about doing this? Although it was thought that high-throughput screening and combinatorial chemistry would generate a significant number of high-quality leads, unfortunately this has not been the case. Combinatorial chemistry mainly yields minor modifications of present day drugs and absolutely requires new scaffolds, such as natural products, on which to build. Although comparative genomics is capable of disclosing new targets for drugs, the number of targets is so large that it requires tremendous investments of time and money to set up all the screens necessary to exploit this resource. This can only be handled by high-throughput screening methodology which demands libraries of millions of chemical entities. It is clear that future success depends not only on high-throughput screening and combinatorial chemistry, but also on the combining of complementary technologies, such as natural product discovery, genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, metagenomics, structure-function drug design, semi-synthesis, recombinant DNA methodology, genome mining and combinatorial biosynthesis. In addition, ‘intelligent screening’ methods, such as robotic separation with structural analysis, metabolic engineering and synthetic biology offer exciting technologies for new natural product drug discovery and the future development of anti-tumor compounds.

Competing Interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding Information: The authors declare that they have no specific funding for this manuscript.

References

- Verdine GL (1996) The combinatorial chemistry of nature. Nature 384: 11–13.

- Holland HD (1998) Evidence for life on earth more than 3850 million years ago. Science 275: 38–39.

- Berdy J (1995) Are actinomycetes exhausted as a source of secondary metabolites? Biotechnologia 7–8: 13–34.

- Mendelson R, Balick MJ (1995) The value of undiscovered pharmaceuticals in tropical forests. Econ Bot 49: 223–227.

- Henkel T, Brunne RM, Mueeller H, Reichel F (1999) Statistical investigation into structural complementarity of natural products and synthetic compounds. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 38: 643–647.

- Knight V, Sanglier JJ, DiTullio D, Braccili S, et al. (2003) Diversifying microbial natural products for drug discovery. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 62: 446–458.

- Fenical W, Jensen PR (1993) Marine microorganisms: a new biomedical resource. New York, USA: Plenum Press 419–457.

- Roessner CA, Scott AI (1996) Achieving natural product synthesis and diversity via catalytic networking ex vivo. Chem Biol 3: 325–330.

- Roessner CA, Scott AI (1996) Genetically engineered synthesis of natural products: from alkaloids to corrins. Annu Rev Microbiol 50: 467–490.

- Cragg GM, Newman DJ, Snader KM (1997) Natural products in drug discovery and development. J Nat Prod 60: 52–60.

- Newman DJ, Cragg GM, Snader KM (2003) Natural products as sources of new drugs over the period 1981–2002. J Nat Prod 66: 1022–1037.

- Harvey AL (2008) Natural products in drug discovery. Drug Discov Today 13: 894–901.

- McCaskill D, Croteau R (1997) Prospects for the bioengineering of isoprenoid biosynthesis. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol 55: 107–146.

- Verpoorte R (2000) Pharmacognosy in the new millennium: leadfinding and biotechnology. J Pharm Pharmacol 52: 253–262.

- Raskin I, Ribnicky DM, Komarnytsky S, Nebojsa I, et al. (2002) Plants and human health in the twenty-first century. Trends Biotechnol 20: 522–531.

- National Cancer Institute (2017) Statistics at a glance: the burden of cancer in the United States.

- Cragg GM, Newman DJ (2005) Plants as a source of anti-cancer agents. J Ethnopharmacol 100: 72–79.

- Cragg GM, Newman DJ (2000) Antineoplastic agents from natural sources: achievements and future directions. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 9: 2783–2797.

- Rawls RL. Modular enzymes (1998) Chem Eng News 76: 29–32.

- Xue J, Duda LC, Smith KE, Fedorov AV, et al. (1999) Electronic structure near the Fermi surface in the quasi-one-dimensional conductor Li0.9Mo6O17. Phys Rev Lett 83: 1235–1238.

- Neumann CS, Fujimori DG, Walsh CT (2008) Halogenation strategies in natural product biosynthesis. Chem Biol 15: 99–109.

- Umezawa H (1972) Enzyme Inhibitors of Microbial Origin. London, UK: University Park Press.

- Umezawa H (1982) Low-molecular-weight enzyme inhibitors of microbial origin. Annu Rev Microbiol 36: 75–99.

- Newman DJ, Shapiro S (2008) Microbial prescreens for anticancer activity. SIM News 58: 132–150.

- Chung KT. H. Boyd Woodruff (2009) antibiotics hunter and distinguished soil microbiologist. SIM News 59: 178–185.

- Zhen YS, Li DD (2009) Antitumor antibiotic pingyangmycin: research and clinical use for 40 years. Chin J Antibiot 34: 577–580.

- Tao M, Wang L, Wendt-Pienkowski E, Zhang N, et al. (2010) Functional characterization of tlmH in Streptoalloteichus hindustanus E465-94 ATCC 31158 unveiling new insight into tallysomycin biosynthesis and affording a novel bleomycin analog. Mol Biosyst 6: 349–356.

- Lam KS, Schroeder DR, Veitch JK, Matson JA, et al. (1991) Isolation of a bromo analog of rebeccamycin from Saccharothrix aerocolonigenes. J Antibiot 44: 934–939.

- Lam KS, Schroeder DR, Veitch JM, Colson KL, et al. (2001) Production, isolation and structure determination of novel fluoroindolocarbazoles from Saccharothrix aerocolonigenes ATCC 39243. J Antibiot 54: 1–9.

- Pickens LB, Kim W, Wang P, Zhou H, et al. (2009) Biochemical analysis of the biosynthetic pathway of an anticancer tetracycline SF2575. J Am Chem Soc 131: 17677–17689.

- Einhorn L, Donohue J (2002) Cis-diamminedichloroplatinum, vinblastine, and bleomycin combination chemotherapy in disseminated testicular cancer. J Urol 167: 928–932.

- Strohl WR, Dickens ML, Rajgarhia VB, Walczak R, et al. (1998) Biochemistry, molecular biology and protein-protein interactions in daunorubicin/ doxorubicin biosynthesis. Dev Ind Microbiol – BMP’ 97 97: 15–22.

- Hwang CK, Kim HS, Hong YS, Kim YH, et al. (1995) Expression of Streptomyces peucetius genes for doxorubicin resistance and aklavinone 11-hydroxylase in Streptomyces galilaeus ATCC 31133 and production of a hybrid aclacinomycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 39: 1616–1620.

- Kim HS, Hong YS, Kim YH, Yoo OJ, et al. (1996)New anthracycline metabolites produced by the aklavinone 11-hydroxylase gene in Streptomyces galilaeus ATCC 3113. J Antibiot 49: 355–360.

- Niemi J, Mäntsälä P (1995) Nucleotide sequences and expression of genes from Streptomyces purpurascens that cause the production of new anthracyclines in Streptomyces galilaeus. J Bacteriol 177: 2942–2945.

- Ylihonko K, Hakala J, Kunnari T, Mäntsälä P (1996) Production of hybrid anthracycline antibiotics by heterologous expression of Streptomyces nogalater nogalamycin biosynthesis genes. Microbiology 142: 1965–1972.

- Strohl WR, Bartel PL, Li Y, Connors NC, et al. (199) Expression of polyketide biosynthesis and regulatory genes in heterologous streptomycetes. J Ind Microbiol 7: 163–174.

- Bartel PL, Zhu CB, Lampel JS, Dosch DC, et al. (1990) Biosynthesis of anthraquinones by interspecies cloning of actinorhodin genes in streptomycetes: clarification of actinorhodin gene functions. J Bacteriol 172: 4816–4826.

- Arcamone F, Penco S, Vigevani A, Redaelli S, et al. (1975) Synthesis and antitumor properties of new glycosides of daunomycinone and adriamycinone. J Med Chem 18: 703–707.

- Madduri K, Kennedy J, Rivola G, Inventi-Solari A, et al. (1998) Production of the antitumor drug epirubicin (4?-epidoxorubicin) and its precursor by a genetically engineered strain of Streptomyces peucetius. Nat Biotechnol 16: 69–74.

- Kraka E, Cremer D (2000) Computer design of anti- cancer drugs. A new enediyne warhead. J Am Chem Soc 122: 8245–8264.

- Kraka E, Tuttle T, Cremer D (2008) Design of a new warhead for the natural enediyne dynemicin A. An increase of biological activity. J Phys Chem B 112: 2661–2670.

- Kowalski RJ, Giannakakou P, Gunasekera SP, Longley RE, et al. (1997) The microtubule-stabilizing agent discodermolide competitively inhibits the binding of paclitaxel (Taxol) to tubulin polymers, enhances tubulin nucleation reactions more potently than paclitaxel, and inhibits the growth of paclitaxel-resistant cells. Mol Pharmacol 52: 4613–4622.

- Gerth K, Bedorf N, Hoefle G, Irschik H, et al. (1996) Epothilones A and B: antifungal and cytotoxic compounds from Sorangium cellulosum (myxobacteria); production, physico-chemical and biological properties. J Antibiot 49: 560–563.

- Gerth K, Steinmetz H, Hoefle G, Reichenbach H (2000) Studies on biosynthesis of epothilones: the biosynthetic origin of the carbon skeleton. J Antibiot 53: 1373– 1377.

- Chou TC, Zhang XG, Harris CR, Kuduk SD, et al. (1998) Desoxyepothilone B is curative against human tumor xenografts that are refractive to paclitaxel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 9642–9647.

- Julien B, Shah S, Ziermann R, Goldman R, et al. (2000) Isolation and characterization of the epothilone biosynthetic gene cluster from Sorangium cellulosum. Gene 16: 153–160.

- Tang L, Shah S, Chung L, Carney J, et al. (2000) Cloning and heterologous expression of the epothilone gene cluster. Science 287: 640–642.

- Cao Y, Langer R (2008) A review of Judah Folkman’s remarkable achievements in biomedicine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 13203–13205.

- Ingber D, Fujita T, Kishimoto S, Sudo K, et al. (1990) Synthetic analogues of fumagillin that inhibit angiogenesis and suppress tumour growth. Nature 348: 555–557.

- Corey EJ, Guzman-Perez A, Noe MC (1994) Short enantioselective synthesis of (-)-ovalicin, a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis, using substrate-enhanced catalytic asymmetric dihydroxylation. J Am Chem Soc 116: 12109–12110.

- Griffith EC, Su Z, Turk BE, Chen S, et al. (1997) Methionine aminopeptidase (type 2) is the common target for angiogenesis inhibitors AGM-1470 and ovalicin. Chem Biol 4: 461–471.

- Sin N, Meng L, Wang MQW, Wen JJ, et al. (1997) The anti-angiogenic agent fumagillin covalently binds and inhibits the methionine aminopeptidase, MetAP-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 6099–6103.

- Antoine N, Greimers R, De Roanne C, Kusaka M, et al. (1994) AGM-1470, a potent angiogenesis inhibitor, prevents the entry of normal but not transformed endothelial cells into the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Cancer Res 54: 2073–2076.

- Turk BE, Griffith EC, Wolf S, Biemann K, et al. (1999) Selective inhibition of amino-terminal methionine processing by TNP-470 and ovalicin in endothelial cells. Chem Biol 6: 823–833.

- Yanase T, Tamura M, Fujita K, Kodama S, et al. (1993) Inhibitory effect of angiogenesis inhibitor TNP-470 on tumor growth and metastasis of human cell lines in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res 53: 2566–2670.

- Tanaka T, Konno H, Matsuda I, Nakamura S, et al. (1995) Prevention of hepatic metastasis of human colon cancer by angiogenesis inhibitor TNP-470. Cancer Res 55: 836–839.

- Sasaki A, Alcalde RE, Nishiyama A, Lim DD, et al. (1998) Angiogenesis inhibitor TNP-470 inhibits human breast cancer osteolytic bone metastasis in nude mice through the reduction of bone resorption. Cancer Res 58: 462–467.

- Brown VI, Fang J, Alcorn K, Barr R, et al. (2003) Rapamycin is active against B-precursor leukemia in vitro and in vivo, an effect that is modulated by IL-7-mediated signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 15113–15118.

- Guba M, von Breitenbuch P, Steinbauer M, Koehl G, et al. (2002) Rapamycin inhibits primary and metastatic tumor growth by anti-angiogenesis: involvement of vascular endothelial growth factor. Nat Med 8: 128–135.

- Pray L (2002) Strange bedfellows in transplant drug therapy. Scientist 16: 36.

- Bailly C (2009) Ready for a comeback of natural products in oncology. Biochem Pharmacol 77: 1447–1457.

- Rini B, Kar S, Kirkpatrick P (2007) Temsirolimus. Nat Rev Drug Discov 6: 599–600.

- Endo A (1979) Monacolin K, a new hypocholesterolemic agent produced by a Monascus species. J Antibiot 32: 852–854.

- Alberts AW, Chen J, Kuron G, Hunt V, et al. (1980) Mevinolin. A highly potent competitive inhibitor of hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase and a cholesterol-lowering agent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 77: 3957–3961.

- Mistafa O, Stenius U (2009) Statins inhibit Akt/PKB signaling via P2X7 receptor in pancreatic cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol 78: 1115–1126.

- Ho BY, Pan TM (2009) The Monascus metabolite monacolin K reduces tumor progression and metastasis of Lewis lung carcinoma cells. J Agric Food Chem 57: 8258–8265.

- Gupta P, Onder T, Jiang G, Tao K, et al. (2009) Identification of selective inhibitors of cancer stem cells by high-throughput screening. Cell 138: 645–659.

- Salas JA, Mendez C (1998) Genetic manipulation of antitumor-agent biosynthesis to produce novel drugs. Trends Biotechnol 16: 475–482.

- Wilkinson B, Micklefield J (2007) Mining and engineering natural-product biosynthetic pathways. Nat Chem Biol 3: 379–386.

- Gross H (2009) Genomic mining – a concept for the discovery of new bioactive natural products. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel 12: 207–219.

- Zerikly M, Challis GL (2009) Strategies for the discovery of new natural products by genome mining. Chembiochem 10: 625–633.

- Zazopoulos E, Huang K, Staffa A, Liu W, et al. (2003) genomics-guided approach for discovering and expressing cryptic metabolic pathways. Nat Biotechnol 21: 187–190.

- Park HB, Kwon HC, Lee CH, Yang HO (2009) Glionitrin A, an antibiotic-antitumor metabolite derived from competitive interaction between abandoned mine microbes. J Nat Prod 72: 248–252.

- Dholwani KK, Saluja AK, Gupta AR, Shah DR (2008) A review on plant-derived natural products and their analogs with anti-tumor activity. Indian J Pharmacol 40: 49–58.

- Bernhardt P, McCoy E, O’Connor SE (2007) Rapid identification of enzyme variants for reengineered alkaloid biosynthesis in periwinkle. Chem Biol 14: 888–897.

- Duflos A, Fahy J, Thillaye du Boullay V, Barret JM, et al. (2000) Vinca alkaloid antimitotic halogenated derivatives US Patent 6127377.

- Wall ME, Wani MC (1996) Camptothecin and taxol: from discovery to clinic. J Ethnopharmacol 51: 239–254.

- Amna T, Puri SC, Verma V, Sharma JP, et al. (2006) Bioreactor studies on the endophytic fungus Entrophospora for the production of an anticancer alkaloid camptothecin. Can J Microbiol 52: 189–196.

- Lorence A, Nessler CL (2004) Camptothecin, over four decades of surprising findings. Phytochemistry 65: 2735–2749.

- Dejong JM, Liu Y, Bollon AP, Long RM, et al. (2005) Genetic engineering of taxol biosynthetic genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol Bioeng 93: 212–224.

- Stierle A, Strobel G, Stierle D (1993) Taxol and taxane production by Taxomyces andreanae, an endophytic fungus of Pacific yew. Science 260: 214–216.

- Li JY, Strobel G, Sidhu R, Hess WM, et al. (1996) Endophytic taxol-producing fungi from bald cypress, Taxodium distichum. Microbiology 142: 2223–2226.

- Wang JF, Li GL, Lu HY, Zhang ZH, et al. (2000) Taxol from Tubercularia sp. Strain TF5, an endophytic fungus of Taxus mairei. FEMS Microbiol Lett 193: 249–253.

- Kumaran RS, Muthumary JP, Hur BK (2008) Taxol from Phyllosticta citricarpa, a leaf spot fungus of the angiosperm Citrus medica. J Biosci Bioeng 106: 103–106.

- Duan LL, Chen HR, Chen JP, Li WP, et al. (2008) Screening the high-yield paclitaxel producing strain Alternaria alternate var monosporus. Chin J Antibiot 33: 650–652.

- Horwitz SB. Taxol (paclitaxel): mechanisms of action. Ann Oncol 5(Suppl. 6): S3–S6.

- Baloglu E, Kingston DGI (1999) The taxane diterpenoids. J Nat Prod 62: 1448–1472.

- Yukimune Y, Tabata H, Higashi Y, Hara Y (1996) Methyl jasmonate-induced overproduction of paclitaxel and baccatin III in Taxus cell suspension cultures. Nat Biotechnol 14: 1129–1132.

- Choi HK, Kim SI, Son JS, Hong SS, et al. Intermittent maltose feeding enhances paclitaxel production in suspension culture of Taxus chinensis cells. Biotechnol Lett 22: 1793–1796.

- Bringi V, Kadkade PG (1993) Enhanced production of taxol and taxanes by cell cultures of Taxus species.

- Li YC, Tao WY, Cheng L (2009) Paclitaxel production using co-culture of Taxus suspension cells and paclitaxel-producing endophytic fungi in a co-bioreactor. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 83: 233–239.

- Manfredi J, Horowitz S (1984) Taxol: an antimitotic agent with a new mechanism of action. Pharmacol Ther 25: 83–125.

- Thayer A (2010) More than a supplier. Chem Eng News 88: 25–27.

- Strobel GA, Long DM (1998) Endophytic microbes embody pharmaceutical potential. ASM News 64: 263–268.

- Strobel GA (2002) Rainforest endophytes and bioactive products. Crit Rev Biotechnol 22: 315–333.

- Deorukhkar A (2007) Back to basics: how natural products can provide the basis for new therapeutics. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 16: 1753–1773.

- Nobili S, Lippi D, Witort E, Donnini M, et al. (2009) Natural compounds for cancer treatment and prevention. Pharmacol Res 59: 365–378.

- Bender RP, Jablonksy MJ, Shadid M, Romaine I, et al. (2008) Substituents on etoposide that interact with human topoisomerase IIa in the binary enzyme-drug complex: contributions to etoposide binding and activity. Biochemistry 46: 4501–4509.

- Lee HJ, Lee HJ, Magesh V, Nam D, et al. (2008) Shikonin, acetylshikonin, and isobutyroylshikonin inhibit VEGF-induced angiogenesis and suppress tumor growth in Lewis lung carcinoma-bearing mice. Yakugaku Zasshi 128: 1681–1688.

- Sarkar FH, Li Y, Wang Z, Kong D (2009) Cellular signaling perturbation by natural products. Cell Signal 21: 1541–1547.

- Rayl AJS (1999) Oceans: medicine chests of the future? Scientist 13: 1.

- Piel J, Hui D, Wen G, Butzke D, et al. (2004) Antitumor polyketide biosynthesis by an uncultivated bacterial symbiont of the marine sponge Theonella swinhoei. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 16222–16227.

- Blokhin AV, Yoo HD, Geralds RS, Nagle DG, et al. (1995)Characterization of the interaction of the marine cyanobacterial natural product curacin A with the colchicine site of tubulin and initial structure-activity studies with analogues. Mol Pharmacol 48: 523–531.

- Dunlap WC, Battershill CN, Liptrot CH, Cobb RE, et al. (2007) Biomedicinals from the phytosymbionts of marine invertebrates: a molecular approach. Methods 42: 358–376.

- Jensen PR, Mincer TJ, Williams PG, Fenical W (2005) Marine actinomycete diversity and natural product discovery. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 87: 43–48.

- Macherla VR, Mitchell SS, Manam RR, Reed KA, et al. (2005) Structure-activity relationship studies of salinosporamide A (NPI-0052), a novel marine derived proteasome inhibitor. J Med Chem 48: 3684–3687.