Abstract

Insulin resistance (IR), obesity and other components of metabolic syndrome [MetS] are highly associated with Alzheimer’s (AD) and Parkinson’s (PD) diseases. Dysregulation of kynurenine (Kyn) pathway (KP) of tryptophan (Trp) metabolism was suggested as major contributor to pathogenesis of AD and PD and MetS. KP, the major source of NAD+ in humans, occurs in brain and peripheral organs. Considering that some, but not all, peripherally originated derivatives of Kyn penetrate blood brain barrier, dysregulation of central and peripheral KP might have different functional impact. Up-regulated Kyn formation from Trp was discovered in central nervous system of AD and PD while assessments of peripheral KP in these diseases yield controversial results. We were interested to compare peripheral kynurenines in AD and PD with emphasis on MetS-associated kynurenines, i.e., kynurenic (KYNA) and anthranilic (ANA) acids and 3-hydroxykynurenine (3-HK). Serum concentrations of KP metabolites were evaluated (HPLC-MS method). In PD patients Trp concentrations were lower, and Kyn: Trp ratio, Kyn, ANA and KYNA were higher than in controls. 3-HK concentrations of PD patients were below the sensitivity threshold of the method. In AD patients. ANA serum concentrations were approximately 3 fold lower, and KYNA concentrations were approximately 40% higher than in controls. Our data suggest different patterns of KP dysregulation in PD and AD: systemic chronic subclinical inflammation activating central and peripheral KP in PD, and central, rather than peripheral, activation of KP in AD triggered by Aβ1–42. Dysregulation of peripheral KP in PD and AD patients might underline association between neurodegenerative diseases and MetS.

Key words

anthranilic acid; kynurenic acid; kynurenine; Parkinson’s disease; Alzheimer’s disease; insulin resistance; obesity

Introduction

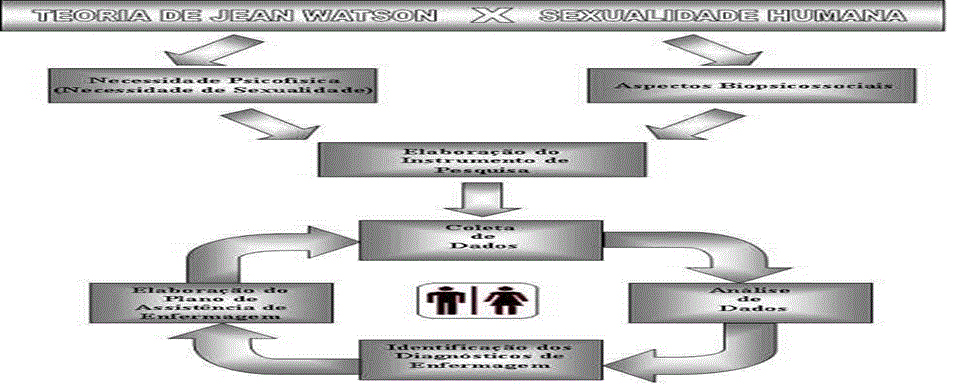

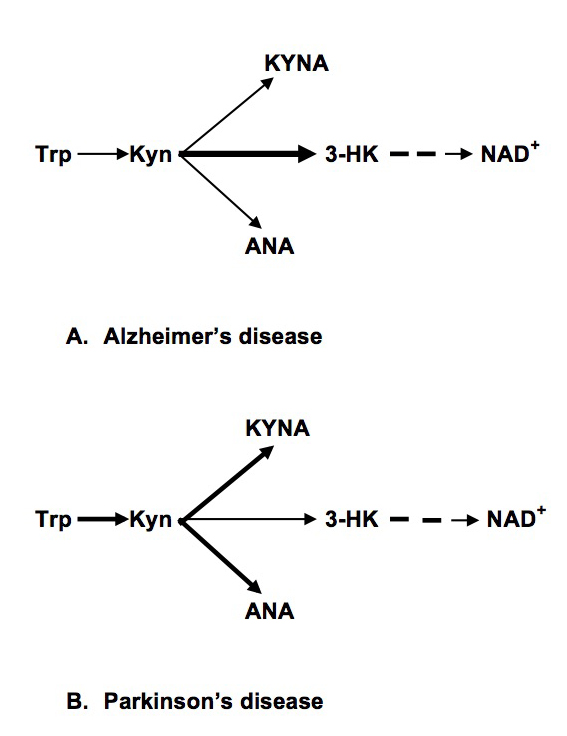

Insulin resistance (IR), obesity and other components of metabolic syndrome [MetS] are highly associated with Alzheimer’s (AD) and Parkinson’s (PD) diseases [1,2]. Dysregulation of kynurenine (Kyn) pathway (KP) of tryptophan (Trp) metabolism was suggested as major contributor to pathogenesis of AD [3], PD [4] and MetS [5,6]. KP, the major source of NAD+ in humans, occurs in brain and peripheral organs (e,g., monocytes/macrophages, liver, pancreas, kidney, intestine, muscles) [7,8]. Initial phase of KR, conversion of Trp into Kyn (via N-formyl-kynurenine), is catalyzed by indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO) or tryptophan-2,3-dioxygenase 2 (TDO); Kyn is further converted into 3-hydroxykynurenine (3HK), kynurenic (KYNA) and anthranilic (ANA) acids; further metabolism of 3-HK resulted in production of NAD+ (Fig.1). Considering that some, but not all, peripherally originated derivatives of Kyn penetrate blood brain barrier (BBB) [9], dysregulation of central and peripheral KP might have different functional impact. Thus, increased production of KYNA in brain was suggested to underline psychotic symptoms [8] while elevation of peripheral KYNA (not penetrating BBB) might contribute to mechanisms of IR and obesity in schizophrenia [10].

Up-regulation of Kyn formation from Trp was discovered in central nervous system of AD and PD [11] while assessments of peripheral KP in these diseases yield controversial results.

In PD patients, elevated serum Kyn: Trp ratio, a clinical index of IDO or TDO activity, was reported [12]. Concentration of KYNA and activity of enzyme, catalyzing Kyn conversion into KYNA, were elevated in red blood cells (but not in plasma) of PD patients [13]). The third available study revealed no differences in Kyn and 3-HK plasma concentrations between PD and control subjects, and elevated KYNA and ANA in PD patients without dyskinesia in comparison with PD patients with dyskinesia [14].

In AD most studies compared concentrations of peripheral kynurenines in serum or plasma of patients with probable AD in comparison with healthy controls (or patients with major depressive disease and subjects with subjective cognitive impairment [15]. Only one study evaluated plasma kynurenines in histopathologically confirmed AD in comparison with age-matched and non-matched healthy subjects [16]. Plasma Trp metabolism was found to discriminate between AD and control group in metabolomic study [17]. Trp concentrations were lower in patients with probable [18-20] and histopathologically confirmed AD [16]. Kyn concentrations were unchanged in probable AD [15,18,20] and significantly lower in histopathologically confirmed AD [16]. Kyn: Trp ratio was higher in probable [18,19] but not in histopathologically confirmed AD [16]. Among derivatives of intermediate KP phase, KYNA concentrations were reduced or unchanged in probable [15,20,21] and histopathologically confirmed [16] AD patients. 3-HK levels were elevated in probable AD patients [15] but lower in plasma of histopathologically confirmed AD patients [16]. Strong tendency to reduced ANA was reported in histopathologically confirmed AD [16]. Notably, significant association of plasma ANA and risk of incident dementia with risk increased by 40% for an increase of one standard deviation was observed in participants of Framingham offspring cohort study [22].

We were interested to compare peripheral kynurenines in AD and PD with emphasis on MetS-associated kynurenines, i.e., KYNA, ANA, 3-HK and xanthurenic acid (XA) [23].

Methods

PD patients

Overnight fasting blood samples were collected from 7 female and 11 male PD patients (age range: 50 to 74). At the time of sampling five patients did not take any anti-Parkinson’s medications; and thirteen patients were treated with L-dopa.

AD patient

Blood samples from 12 female and 8 male patients (age range 60 to 75) with probable AD were studied. All AD patients had MMSE between 20 and 23. They were treated with Aricept or Namenda.

Healthy Subjects (Controls)

There were 24 age- and gender- matched (12 females and 12 males) healthy subjects. Study was approved by Tufts Medical Center IRB.

Assessment of Kynurenine metabolites

Plasma samples were stored at −80°C until analysis. Trp, Kyn, ANA, KYNA and 3-HK concentrations were analyzed by high performance liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) as described elsewhere [10].

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean ± standard error (Trp and Kyn in μM and ANA, KYNA and 3-HK in nM). Statistical significance was assessed by unpaired t test with Welch correction, two-tailed.

Results

PD patients

There was no difference in plasma concentrations of Trp, Kyn and all studied Kyn metabolites of not treated and treated with L-DOPA patients (data not shown). Therefore, combined data of not-treated and L-DOPA – treated PD patients were used for the further analysis. Trp concentrations were lower, and Kyn: Trp ratio was higher in PD patients than in controls (Table 1). Serum concentrations of Kyn, and its down-stream metabolites, ANA and KYNA, were approximately two fold higher than in control subjects (Table 1). 3-HK concentrations of PD patients were below the sensitivity threshold of the method. XA concentrations were not different between PD and control group (11.87 ± 1.3 and 11.74 ± 1.25, resp).

Table 1. Tryptophan – kynurenine metabolites in serum of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease patients.

| Means ± sem |

Trp (μM) |

Kyn (μM) |

Kyn: Trp (x100) |

ANA (nM) |

KYNA (nM) |

3-HK (nM) |

| Control (n=24) |

68.9 ± 2.49 | 1.76 ± 0.09 | 2.55 ± 0.14 | 70.54 ± 17.9 | 35.78 ± 3.59 | 19.55 ± 3.14 |

| PD (n=18) |

48.56 ± 2.4* | 2.34 ± 0.11# | 4.82 ± 0.18* | 156.68 ± 20.46# | 65.97 ± 7.2# | Not detectable |

| AD (n=20) |

64.64 ± 3.4 | 1.77 ± 0.11 | 2.74 ± 0.15 | 19.51 ± 3.5* | 34.35 ± 2.59 | 27.52 ± 2.3# |

| *p<0.001 in comparison with all other groups; #) p<0.001 in comparison with control (except for 3HK p=0.04). Unpaired t test with Welch correction, two tailed. Abbreviations: Trp: tryptophan; Kyn: kynurenine; KYNA: kynurenic acid; ANA: anthranilic acid; 3-HK: 3-hydroxykynurenine; PD: Parkinson’s disease; AD: Alzheimer’s disease |

||||||

AD patients

ANA serum concentrations were approximately 3 fold lower, and KYNA concentrations were approximately 40% higher in AD than in controls (Table 1). XA concentrations were not different between AD and control group (10.97 ± 1.07 and 11.74 ± 1.25, resp).

Discussion

Serum levels of KP metabolites might reflect the activity of their formation in peripheral organs [4,8]. Notably, KP in fatty tissue does not express kynurenine-2-monooxygenase (KMO), enzyme converting Kyn into 3-HK, and, therefore, KYNA and ANA are the end products of KP in fatty tissue [24].

Literature data suggested increased conversion of Kyn into 3-HK in PD-related brain structures with consequent formation of neurotoxic metabolites [4]. Present results suggest an increased conversion of Kyn into KYNA and ANA in peripheral organs (in difference with KP in PD-related brain structures [25,26].

In PD patients we confirmed literature data on decreased Trp and increased Kyn concentrations, and, consequently, increased Kyn: Trp ratio, suggesting activation of the initial phase of KP, i.e., conversion of Trp into Kyn [12]. Some discrepancies between literature data (see Introduction) and present results may depend on studied tissues, i.e., serum VS plasma VS RBC; and analytical methods; as well as differences in the other factors potentially affecting KP such as length of disease and age of patients [2,27].

In PD patients we found as increased (about two-fold) plasma concentrations of KYNA and ANA. Considering that KYNA, ANA and 3-HK compete for Kyn as a common substrate in both central and peripheral organs (Figure 1), our data suggest a shift of down-stream Kyn metabolism from 3-HK production towards formation of ANA and KYNA.

Figure 1. Abbreviations: Trp: Tryptophan; Kyn: kynurenine; KYNA: Kynurenic Acid; ANA: Anthranilic acid; 3-HK: 3-hydroxykynurenine; NAD+: Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide

In AD patients, we found no differences in Trp, Kyn concentrations and Kyn: Trp ratios. Present data are in agreement with the study of histopathologically confirmed AD and age-matched controls that did not find changes of Kyn: Trp ratio [16]. We found elevated 3-HK serum concentration that might suggest decreased availability of Kyn as a substrate for formation of KYNA and ANA in agreement with present results of drastic reduction of ANA concentrations. Peripheral production of ANA deserves further studies, especially considering significant association of plasma ANA and risk of incident dementia in Framingham offspring cohort study [22].

Present study suggested different patterns of dysregulation of the intermediate phase of peripheral KP in PD and AD: increased formation of KYNA and ANA (and reduced production of 3-HK) in PD and reduced formation of ANA (and increased production of 3-HK) in AD (Figure 1). Our data suggest different mechanisms of KP dysregulation in PD and AD: systemic chronic subclinical inflammation activating central and peripheral KP in PD, and central, rather than peripheral, activation of KP in AD triggered by Aβ 1–42 [28]. Notably, there was no association between KP changes and plasma concentrations of neopterin, KP related marker of inflammation, in AD patients [16].

Literature and our data suggest that up-regulation of peripheral KYNA, ANA and Kyn production might contribute to development of obesity and IR, conditions highly associated with early (contrary to late) stages of PD [2,27]. KYNA concentrations positively correlated with BMI in clinical studies [29]. We reported elevation of blood concentrations of KYNA, ANA and Kyn in Zucker obese rats (ZFR) [30]. KYNA elevation in obesity may be a consequence of KMO deficiency in fatty tissue that does not express KMO genes rending KYNA and ANA as the end products of KP in human fatty tissue [24]. KYNA, ANA and Kyn might promote the development of obesity via activation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) that regulates xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes. ANA, KYNA and Kyn are the endogenous human AHR ligands [31,32]. Over-activation of AHR promoted [33] while AHR deficiency protected mice from diet-induced obesity [34].

PD is highly associated not only with obesity but with IR. Increased risk of PD among subjects with T2D was independent from obesity (BMI) [35]. We have previously reported elevation of serum KYNA and ANA in T2D [36,37] and correlation of Kyn with HOMA-IR in HCV patients [38]. Metabolomics analysis revealed 1.8 fold increase of urine KYNA in spontaneously and naturally diabetic rhesus macaques [39]. Successful treatment of IR was associated with down-regulation of KP, including inhibition of KYNA production [40]. One of the possible mechanisms of KYNA involvement in diabetes is activation of G-protein-coupled receptor 35 (GPR35) located primarily in peripheral, including pancreas, tissues [41]. KYNA is an endogenous agonist of GPR35 [41]. Exogenous GPR35 agonists were patented as agents reducing blood glucose levels in oral glucose tolerance tests, stimulate glucose uptake in differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes [42].

Significance of ANA elevation has been explored only in a few papers. Serum ANA was positively associated with neopterin, Kyn, Kyn: Trp ratio, and negatively with Trp in healthy young adults [43]. ANA was reported to significantly increase glucose uptake and inhibited 14CO2 production from [U-14C] glucose in in vitro studies [44].

On the other hand, AD is characterized by developing of brain IR [45] while weight loss preceded the diagnosis of dementia in community-dwelling older adults even after controlling for other factors associated with weight [46]. It was suggested that decline in BMI that precedes the diagnosis of AD may be related to neurodegeneration in areas of the brain involved in homeostatic weight regulation [1].

Therefore, we suggest that up-regulated peripheral formation of KYNA, ANA and Kyn contribute to increased risk of PD among subjects with diabetes, and, that contrary to PD, central, rather than peripheral, KP dysregulation contribute to association of IR with AD.

Present data warrant further studies of dysregulations of peripheral KP in PD and AD patients as one of the mechanisms (and potential biomarkers) of association between neurodegenerative disease and MetS.

Acknowledgement

GF Oxenkrug is a recipient of MH104810. Paul Summergrad is a non-promotional speaker for CME outfitters, Inc., and consultant and non-promotional speaker for Pri-med, Inc. Authors appreciate Bioreclamation IVT, NY, USA, for help in collection of serum samples.

References

- Alford S, Patel D, Perakakis N, Mantzoros CS (2017) Obesity as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease: weighing the evidence. Obes Rev. [crossref]

- Vikdahl M, Carlsson M, Linder J, Forsgren L, Håglin L (2014) Weight gain and increased central obesity in the early phase of Parkinson’s disease. Clin Nutr 33: 1132–1139. [crossref]

- Baran H, Jellinger K, Deecke L (1999) Kynurenine metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 106: 165–181. [crossref]

- Lim C, Fernández-Gomez FJ, Braidy N, Estrada C, Costa C, et al. (2017) Involvement of the kynurenine pathway in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Prog Neurobiol 155: 76–95. [crossref]

- Oxenkrug GF (2010) Metabolic syndrome, age-associated neuroendocrine disorders and dysregulation of tryptophan – kynurenine pathway metabolism. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1199: 1–14.

- Mangge H, Summers LL, Meinitzer A, Zelzer S, Almer G, et al. (2014) Obesity-related dysregulation of the Tryptophan–Kynurenine metabolism: Role of age and parameters of the metabolic syndrome. Obesity.

- Paluszkiewicz P, Zgrajka W, Saran T, Schabowski J, Piedra JL, et al. (2009) High concentration of kynurenic acid in bile and pancreatic juice. Amino Acids 37: 637–641. [crossref]

- Schwarcz R, Bruno JP, Muchowski PJ, Wu HQ (2012) Kynurenines in the mammalian brain: when physiology meets pathology. Nat Rev Neurosci 13: 465–477. [crossref]

- Fukui S, Schwarcz R, Rapoport SI, Takada Y, Smith QR (1991) Blood-brain barrier transport of kynurenines: implications for brain synthesis and metabolism. J Neurochem 56: 2007–2017.

- Oxenkrug G, van der Hart M, Roeser J, Summergrad P. Peripheral kynurenine-3-monooxygenase deficiency as a potential risk factor for metabolic syndrome in schizophrenia patients Interg Clin Med 2017: 1: 1–3

- Török N, Majláth Z, Fülöp F, Toldi J, Vécsei L (2016) Brain Aging and Disorders of the Central Nervous System: Kynurenines and Drug Metabolism. Curr Drug Metab 17: 412–429. [crossref]

- Widner B, Leblhuber F, and D. Fuchs. Increased neopterin production and tryptophan degradation in advanced Parkinson’s disease. J Neural Transm, 2002; 109: 181–189

- Hartai Z, Klivenyi P, Janaky T, Penke B, Dux L, et al. (2005) Kynurenine metabolism in plasma and in red blood cells in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci 239: 31–35. [crossref]

- Havelund JF, Andersen AD, Binzer M, Blaabjerg M, et al. (2017) Changes in kynurenine pathway metabolism in Parkinson patients with L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia. J Neurochem. [Epub ahead of print]

- Schwarz M, Guillemin GJ, Teipei SJ, Buerger K, Hampei H (2013) Increased 3-hydroxykynurenine serum concentrations differentiate Apzheimer’s disease patients from controls. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurisci 263: 345–352.

- Giil LM, Midttun Ø, Refsum H (2017) Kynurenine Pathway Metabolites in Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis 60: 495–504. [crossref]

- Trushina E, Dutta T, Persson XM, Mielke MM, Petersen RC (2013) Identification of altered metabolic pathways in plasma and CSF in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease using metabolomics. PLoS One 20: 8(5): e63644.

- Widner B, Leblhuber F, Walli J, Tilz GP, Demel U, et al. (2000) Tryptophan degradation and immune activation in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 107: 343–353. [crossref]

- Greiberger J, Fuchs D, Leblhuber F, Greoberger M, Wintersteiger R, et al. (2010) Carbonyl proteins as a clinical marker in Alzheimer’s diasease and its relation to tryptophan degradation and immune activation. Clin Lab 56: 441–448.

- Gulaj E, Pawlak K, Bien B, Pawlak D (2010) Kynurenine and its metabolites in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Adv Med Sci 55: 204–211. [crossref]

- Hartai Z, Junasz A, Rimannocyz A, Janaky T, Donko T, Dux L, Penke B, Toth GK, Janka Z, Kalman J. Decreased serum and red blood cells kynurenic acid levels in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Int, 2007, 50: 308–13

- Chouraki V, Preis SR, Yang Q, Beiser A, Li S, et al. (2017) Association of amine biomarkers with incident dementia and Alzheimer’s disease in the Framingham Study. Alzheimers Dement. S1552-5260(17)30200–5.

- Oxenkrug G (2015) 3-hydroxykynurenic acid and type 2 diabetes: implications for aging, obesity, depression, Parkinson’s disease and schizophrenia. In: Engin A, Engin EB (eds) Tryptophan Metabolism: Implications for Biological Processes, Health and Diseases, Molecular and Integrative Toxicology pp.173–195.

- Favennec M, Hennart B, Caiazzo R, Leloire A, Yengo L, et al. (2015) The Kynurenine Pathway is Activated in Human Obesity and Shifted Toward Kynurenine Monooxygenase Activation. Obesity 23: 2066–2074.

- Ogawa T, Matson WR, Beal MF, Myers RH, Bird ED, et al. (1992) Kynurenine pathway abnormalities in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology 42: 1702–1706. [crossref]

- Lewitt PA, Li J, Lu M, Beach TG, Adler CH, Guo L; Arizona Parkinson’s Disease Consortium (2013) 3-hydroxykynurenine and other Parkinson’s disease biomarkers discovered by metabolomic analysis. Mov Disord 28(12): 1653–1660.

- Hu G, Antikainen R, Jousilahti P, Kivipelto M, Tuomilehto J (2008) Total cholesterol and the risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology 70: 1972–1979. [crossref]

- Guillemin GJ, Smythe GA, Veas LA, Takikawa O, Brew BJ (2003) A beta 1-42 induces production of quinolinic acid by human macrophages and microglia. Neuroreport 14: 2311–2315. [crossref]

- Zhao J, Shen D, Djukovic C, Daniel-MacDougall H, Gu X, et al. (2016) Metabolomics identified metabolites associated with body mass index and prospective weight gain among Mexican American women. Obes Sci Pract 2: 309–317

- Oxenkrug G, Cornicelli J, van der Hart M, Roeser J, Summergrad P (2016) Kynurenic acid, an aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligand, is elevated in serum of Zucker fatty rats. Integr Mol Med 3(4): 761–763.

- DiNatale BC, Murray IA, Schroeder JC, Flaveny CA, Lahoti TS, et al. (2010) Kynurenic acid is a potent endogenous aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligand that synergistically induces interleukin-6 in the presence of inflammatory signaling. Toxicol Sci 115: 8997

- Schrenk D, Riebniger D, Till M, Vetter S, Fiedler HP (1999) Tryptanthrins and other tryptophan-derived agonists of the dioxin receptor. Adv Exp Med Biol 467: 403–408. [crossref]

- Kerley-Hamilton JS, Trask HW, Ridley CJ, Dufour E, Ringelberg CS, et al. (2012) Obesity is mediated by differential aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling in mice fed a Western diet. Environ Health Perspect 120: 1252–1259.

- Moyer BJ, Rojas IY, Kerley-Hamilton JS, Hazlett HF, Nemani KV, et al. (2016) Inhibition of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor prevents Western diet-induced obesity. Model for AHR activation by kynurenine via oxidized-LDL, TLR2/4, TGFß, and IDO1. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 300: 13–24.

- Gang H, Jousilahti P, Bidel S, et al. Type 2 diabetes and the risk of Parkinson’s disease. Diabetes Care 2007; 30(4): 843–7. Format: Abstract Diabetes Care. 2007;30(4):842-7. J Neurochem. 2017 Jun 19. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14104.

- Oxenkrug GF (2015) Increased plasma levels of xanthurenic and anthranilic acids in type 2 diabetes. Mol Neurobiol 52;805-810

- Oxenkrug G, van der Hart M, Summergrad P (2015) Elevated anthranilic acid plasma concentrations in type 1 but not type 2 diabetes mellitus. Integr Mol Med 2(5): 365–368.

- Oxenkrug GF, Turski WA, Zgrajka, J. V. Weinstock, and P. Summergrad (2013). Tryptophan-Kynurenine Metabolism and Insulin Resistance in Hepatitis C Patients. Hepatitis Research and Treatment, (Vol. 2013), Article ID 149247, 4 pages http: //dx. doi.org/10.1155/2013/149247

- Patterson AD, Bonzo JA, Li F, Krausz KW, Eichler GS, Aslam S, et al. (2017) Metabolomics reveals attenuation of the SLC6A20 kidney transporter in nonhuman primate and mouse models of type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Biol Chem 286(22): 19511–22.

- Muzik O, Burghardt P, Yi Z, Kumar A, Seyoum B, et al. (2017) Successful metformin treatment of insulin resistance is associated with down-regulation of the kynurenine pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Comm 488: 29–32

- Wang J, Simonavicius N, Wu X, Swaminath G, Reagan J, et al. (2006) Kynurenic acid as a ligand for orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR35. J Biol Chem 281: 22021–22028. [crossref]

- Leonard JN, Chu ZL, Unett DJ, Gatlin JE, Gaidarov I, et al. (2007) GPR35 and modulators thereof for the treatment of metabolic-related disorders. United States 20070077602

- Deac OM, Mills JL, Gardiner CM, Shane B, Quinn L, et al. (2015) Neopterin and Interleukin-10 Are Strongly Related to Tryptophan Metabolism in Healthy Young Adults. J Nutr 145(4): 701–7.

- Schuck PF, Tonin A, da Costa Ferreira G, Viegas CM, Latini A, et al. (2007) Kynurenines impair energy metabolism in rat cerebral cortex. Cell Mol Neurobiol 27(1): 147–160.

- Talbot K (2014) Brain insulin resistance in Alzheimer’s disease and its potential treatment with GLP-1 analogs. Neurodegener Dis Manag 4: 31–40. [crossref]

- Barrett-Connor E, Edelstein SL, Corey-Bloom J, Wiederholt WC (1996) Weight loss precedes dementia in community-dwelling older adults. J Nutr Health Aging 44: 1147–1152.