DOI: 10.31038/NAMS.2022512

Abstract

The effects of increasing sun light irradiaiton time (30 min, 120 min, 240 and-360 min), increasing photocatalytic power (10 W, 50 and 100 W), increasing graphene oxide (GO) nanoparticle concentrations (2 mg/l, 4 and 8 mg/l), increasing titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticle concentrations (1 mg/l, 3 mg/l, 6 and 9 mg/l), increasing GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposite concentrations (1 mg/l, 2 and 4 mg/l) on the destructions of four hydrophobic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in a real petrochemical industry wastewater in Izmir (Turkey) were investigated. The yields in more hydrophobic PAHs with high benzene rings [benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) and benzo[k]fluoranthene (BkF)] were as high as the less hydrophobic PAHs with lower benzene rings [acenaphthylene (ACL) and carbazole (CRB)] at pH = 7.0, at 22°C after 360 min sun light irradiation time. Maximum 97% ACL, 98%CRB, 98%BaP and 99%BkF PAHs removals was detected at 4 mg/l GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposite concentration, under sun light intensity = 100 mW/cm2, at photocatalytic power = 100 W, at sun light irradiation time = 360 min, at pH = 7.0 and at 22°C, respectively. The effective PAHs concentrations caused 50% mortality in Daphnia magna cells increased from initial EC50 = 342.56 ng/ml to EC50 = 631.05 ng/ml, at pH = 7.0 and at 22°C after 360 min photocatalytic degradation time resulting in a maximum acute toxicity removal of 99.99% at GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocompoasite concentration of 4 mg/l. The Daphnia magna acute toxicity was significantly reduced.

Keywords

Daphnia magna acute toxicity, Graphene oxide, GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposite, Petrochemical industry wastewater, Photocatalytic degradation, Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, titanium dioxide

Introduction

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are an important class of persistent organic pollutants (POPs), and have been ubiquitously found in the environment [1]. Besides the natural sources, PAHs are often from anthropogenic sources such as incomplete combustion of fossil fuels, and accidental spillages of crude and refined oils [2,3]. Due to their persistence and potential harmful impact on the ecosystem and human health, PAHs have been classified as priority pollutants by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) [4].

Wastewater treatment plants, especially those serving industrial areas, consistently receive complex mixtures containing a wide variety of organic pollutants. Groups of compounds present in the petrochemical industries include polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which are listed as US-EPA and EU priority pollutants, and concentrations of these pollutants therefore need to be controlled in treated wastewater effluents [5]. PAHs are ubiquitous environmental pollutants with mutagenic properties, which have not been included in the Turkish guidelines for treated waste monitoring programs [6]. Several hydroxy-PAHs such as hydroxylated derivatives of Benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) and Chrysene (CHR) have been shown to possess estrogenic activity and cause damage to DNA leading to cancer and possibly other effects [7]. As a consequence of their strongly hydrophobic properties and their resistance to biodegradation, PAHs are not always quantitatively removed from wastewaters by activated sludge treatments, which very efficiently relocate them into treated effluents.

Titanium dioxide (TiO2) is the most used photocatalyst due to its environment friendliness, abundant supply and cost-effectiveness [8]. However, due to the wide bandgap (3.2 eV for anatase and 3.0 eV for rutile) [9], TiO2 can only be excited in the ultraviolet (UV) range, which accounts for only 4% of the solar radiation [10]. Therefore, various efforts have been attempted to extend the utilization of TiO2 to the visible light range (>40% of the solar energy), such as metal/non-metal doping, noble metal deposition, semiconductors coupling, and photosensitization [11,12].

Graphene is a flat monolayer of carbon atoms tightly packed into a two-dimensional honeycomb lattice. In recent years, graphene has attracted a great deal of attentions for its potential applications in many fields, such as nano-electronics, fuel-cell technology, supercapacitors, and catalysts [13,14]. Graphene oxide (GO) is one of the most important precursors of graphene, and thus, they share similar sheet structures and properties such as high stability and semiconducting characteristics [15]. GO can enhance the light absorption via expanding the photoresponsive range to visible light and suppress the charge recombination by serving as a photo-generated electron transmitter, when coupled with TiO2. To further enhance the conductivity and reduce the bandgap, noble metals (e.g., gold, palladium and platinum) are often incorporated to the GO-TiO2 nanocomposite by surface deposition [16].

Compared with noble metals, strontium (Sr), as an alkaline earth metal, has much wider and richer sources, and it is the 15th most abundant element in the Earth’s crust with an estimated abundance of nearly 360 mg/l [17]. Sr has been widely employed as a dopant for various semiconductors (e.g., TiO2, zinc oxide and germanium dioxide) to enhance the photocatalytic activities [18]. Moreover, the OH and carbonate forms of Sr (Sr(OH)2/SrCO3) have been reported to have high photocatalytic activity under visible-light irradiation [19-21].

The reactive oxygen species (ROS) formed during TiO2 photocatalysis include the hydroxyl radical (OH●), superoxide anion radical (O2-●), hydroperoxyl radical (HO2●), singlet oxygen (1O2), and their subsequent reactions with the target contaminants occur at or very near the TiO2 surface [22]. OH● radicals, generated on the surface of the catalyst following oxidation of water from the positive holes of TiO2, are non-selective oxidizing species with strong oxidation potential (2.80 V) that rapidly react with most organic compounds with rate constants in the order of 106-1010 1/M.s [23]. Various studies have investigated the degradation of MC-LR in pure solutions or crude extracts with TiO2 photocatalysis to study the effect of specific water quality parameters [24-27] or the properties of the photocatalyst used [28-32]. Solar light activated materials have also been tested to reduce application cost [33]. Herein, sulfate radical generating oxidants were added as a way to reduce the energy requirements of the photocatalytic system for the removal of MC-LR as most of the light activated materials are not currently mass produced. Sulfate radicals (SO4-●) are among the strongest oxidants known for the abstraction of electrons [2.5-3.1 V] [34,35]. They are much stronger than OH● radicals [1.89-2.72 V (Buxton et al., 1988)] and other commonly used in the drinking water industry oxidants, such as permanganate [E = 1.70 V] [36] and hypochlorous acid [E = 1.49 V] [37]. SO4-● radicals can be produced through homolytic dissociation of the oxidants through heat and radiation and e– transfer mechanisms from Fenton-like reagents [38-40] reported that owing to their selectivity, SO4-● radicals are more efficient oxidants for the removal of organic compounds with unsaturated bonds and aromatic constituents than the OH● radicals. Yet there are limited studies on SO4-● based AOPs (compared with OH●) for the degradation of recalcitrant organic contaminants and especially cyanotoxins [41-43]. Even fewer studies have investigated the effect of coupling SO4-● radical generating oxidants with TiO2 on the removal of emerging contaminants with various light sources. Furthermore, simulated solar irradiation (SSI) has been used in the SSI/TiO2/PS treatment [44] and showed higher potential for the removal of the pesticide DEET compared with the SSI/TiO2/H2O2 system. PS was also coupled with TiO2 photocatalysts for the degradation of dyes under solar [45] and UV radiation [46].

The aim of this study was to determine the effects of increasing GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 concentrations (1 mg/l, 2 and 4 mg/l), increasing GO concentrations (2 mg/l, 4 and 8 mg/l), increasing TiO2 concentrations (1 mg/l, 3 mg/l, 6 and 9 mg/l), increasing photocatalytic powers (10 W, 50 and 100 W) and increasing sun light irradiation times (30 min, 120 min, 240 and 360 min) on the photocatalytic degradation of four hydrophobic PAHs namely ACL, CRB, BaP and BkF at pH = 7.0 and at 22°C, respectively. Furthermore, the effects of the operational conditions on the removal of acute toxicity were also determined using Daphnia magna.

Materials and Methods

Material Synthesis

GO was synthesized according to the modified Hummers method [47], and titanium dioxide nanoparticles (Nano-TiO2) were prepared following the approach reported in [48]. Supporting Information (SI) Text S1 provides detailed procedures for the preparation of GO and Nano-TiO2. The GO-TiO2 nanocomposite was then synthesized through the sono-chemical reaction of Nano-TiO2 in the presence of the GO. In brief, 3 g of the mixture of GO and Nano-TiO2 (mass ratio = 2:1) was added to 100 ml of distilled water, and stirred for 0.5 h at room temperature (22 ± 1°C). The suspension was then sonicated for 1 h. The resultant composite was recovered by filtration, rinsed with ethanol and then freeze-dried to yield the GO-TiO2 composites. Subsequently, dispersing known mass of GO-TiO2 (30 wt% of the final mass) in a 500 ml of sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution (1 M), and a pre-determined amount of strontium chloride (SrCl, 0.5 M) was added dropwise to the dispersion at a rate of 2.0 ml/min using a Titronic Universal titrator (SCHOTT, Mainz, Germany). The resulting material, GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3, was then filtered, washed with distilled water until no chloride was detected in the washing water, and then freeze-dried for 48 h. For comparison, a GO-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposite was also prepared by the similar procedure with 20 wt% GO but without TiO2.

Material Characterization

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were performed on a PW1820 X-ray diffractometer (Philips, Amsterdam, Netherlands) using Cu Kα radiation. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were obtained with a JSM-840A electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) micro-analytical system (EDAX, Mahwah, NJ, USA). The EDX analysis was performed at 263.15°C magnification to map the distribution of Sr and Ti on the nanocomposite surface. Fourier transform-infrared (FTIR) measurements were carried out with a Nicolet 560 FTIR spectrometer on KBr wafers (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., MA, USA). The spectra were recorded from 4000 to 400 1/cm at a resolution of 4 1/cm. Nitrogen (N2) adsorption-desorption isotherms were measured using AS1Win (Quantachrome Instruments, FL, USA) at the liquid N2 temperature of 196.15°C, from which Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) specific surface area (SBET), micropore volume (Vmic), total pore volume (Vt), and pore size distribution (PSD) were derived. Potentiometric titration measurements were carried out with a T50 automatic titrator (Mettler Toledo, Columbia, MD, USA) and the total surface charge (Qsurf, mmol/g) of the nanocomposite was then calculated. Differential thermal gravimetric (DTG) analysis was conducted on an STA449F3 instrument (Netzsch, Selb, Germany). Reactive oxydizing agents such as potassium peroxymonosulfate (PMS, HSO5–), potassium persulfate (PS, K2S2O8), and the quenching agent sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Poole, UK).

Photocatalytic Degradation

Simulated sun light was generated using a 94041A solar simulator (Newport Corporation, Irvine, CA). A cylindrical quartz tank reactor with a Pyrex pillar (80 × 70 mm) was fabricated as the photoreactor. The light intensity reached the reactor was 100 mW/cm2. The detailed information on the solar simulator and photoreactor has been reported elsewhere [49]. PAHs were purchased from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA, USA), and a stock solution of 2 g/l was prepared in methanol. Deionized (DI) water (Millipore Co., 18.2 MΩ·cm) was used in preparing all aqueous solutions. Typically, the photocatalytic degradation kinetic tests were conducted under the following conditions: solution volüme = 250 ml, initial PAHs concentration = 1 mg/l, 5 mg/l and 10 mg/l, catalyst dosage = 50 mg/l, pH = 7.0 ± 0.2, and T = 22 ± 1°C. The solution-photocatalyst mixture was first stirred in the dark for 2 h to allow PAHs adsorption to reach equilibrium. Subsequently, photodegradation was initiated by exposing the reactor to the simulated sun light.

Analytical Methods

UV-Visible spectra of solutions were obtained using an HP 8453 UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). PAHs concentration was determined using an HP 1100 HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with a detection limit of 2.5 μg/l at the UV detection wavelength of 250 nm. Photodegradation intermediates were analyzed using an HP7890A/HP5975C gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

The contributions of various reactive oxygen species (ROS) during the photocatalytic degradation process were investigated by adding scavengers to selectively quench radicals, i.e., potassium peroxymonosulfate (PMS, HSO5–), potassium persulfate (PS, K2S2O8), and the quenching agent sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3) were used.

PAHs Measurements

For PAHs and some metabolites (hydroxy-benzoic acid, benzoic acid) analyses the samples were first filtered through a glass fiber filter (47 mm-diameter) to collect the particle-phase in series with a resin column (~10 g XAD-2) and to collect dissolved-phase polybrominated diphenyl ethers. Resin and water filters were ultrasonically extracted for 60 min with a mixture of 1/1 acetone: hexane. All extracts were analyzed for four PAHs (Table 1) gas chromatographically (Agilent 6890N GC) equipped with a mass selective detector (Agilent 5973 inert MSD). A capillary column (HP5-MS, 30 m, 0.25 mm, 0.25 µm) was used. The initial oven temperature was kept at 50°C for 1 min, then raised to 200°C at 25°C/min and from 200 to 300°C at 8°C/min, and then maintained for 5.5 min. High purity He(g) was used as the carrier gas at constant flow mode (1.5 ml/min, 45 cm/s linear velocity). PAHs and their metabolites were identified on the basis of their retention times, target and qualifier ions and were quantified using the internal standard calibration procedure. To determine the degradation intermediates, samples (10 ml each) were collected at 0 min, 30 min, 120 min, 240 min and 360 min. The hydrophobic PAHs (ACL, CRB, BaP and BkF) were performed using a HPLC (Agilent-1100) with a method developed by Lindsey and Tarr [50]. The chromatographic conditions for The hydrophobic PAHs (ACL, CRB, BaP and BkF) determination were as follows: C-18 reverse phase HPLC column (Ace 5C18; 25-cm x 4.6-mm, 5 μm, mobile phase: 50/50 (v/v) methanol/organic-free reagent water). pH, temperature, oxidation-reduction potential (ORP) were monitored following Standard Methods 2550, 2580 and 5220 D [51]. H2O2 was quantified with a colorimetric method following Standard Method 3550.

Table 1: Energy efficiency of photocatalysis with different sun light intensities at ambient conditions after 360 min sun light irradiation time (n=3, mean values, n: deionized water and petrochemical wastewater containing PAHs)

|

Energy efficiency of photocatalysis with different sun light intensities

|

|

Sun light intensity (W/cm2)

|

Power density (W/ml) |

Specific energy (kWh/kg COD-in influent) |

COD removal efficiency (%)

|

|

17

|

0.12 |

8.29 |

47

|

|

38

|

0.91 |

8.90 |

59

|

|

24.03

|

1.34 |

9.26 |

68

|

|

39.09

|

1.71 |

9.91 |

77

|

|

46

|

1.97 |

10.83 |

80

|

|

52.3

|

2.38 |

12.42 |

86

|

Data Analysis

The pseudo-first-order kinetic model was employed to fit the kinetic data:

Where, Ct and C0 are the PAHs concentrations (μg/l) at the reaction time of t and 0 min, respectively, and k is the rate constant (1/min). The integration of UV-Vis absorbance of PAHs was achieved using the software OriginPro 8 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). The correlation fittings between the reaction rate constant and various water quality parameters were conducted by using OriginPro 8 or GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). The fitting models included fourth-order polynomial and sigmoidal (Boltzmann and DoseResp functions) equations.

Daphnia magna Acute Toxicity Test

To test toxicity 24 h old Daphnia magna were used as described in Standard Methods. After preparing the test solution, experiments were carried out using 5 or 10 daphnids introduced into the test vessels. These vessels had 100 ml of effective volume at 7-8 pH, providing a minimum DO concentration of 6 mg/l at an ambient temperature of 20-25°C. Young Daphnia magna were used in the test (≤24 h old). A 24 h exposure is generally accepted as standard for a Daphnia acute toxicity test. The results were expressed as mortality percentage of the Daphnids. Immobile animals were reported as dead Daphnids.

All experiments were carried out three times and the results given as the means of triplicate samplings. Individual PAH concentrations are given as the mean with standard deviation (SD) values.

Statistical Analysis

The regression analysis between y (dependent) and x (independent) variables was carried out using Windows Excel data analysis. An ANOVA test was performed in order to determine the statistical significance between x and y variables.

Results and Discussion

Raw Wastewater

Characterization of raw petrochemical wastewater taken from the influent of the aeration unit of a petrochemical industry wastewater treatment plant was performed. The results are given as the mean value of triplicate sampling. The mean values for pH, ORP were recorded as 7.21 and 28.20 mV, respectively. The mean TSS and TVSS concentrations were measured as 310.3 and 250.6 mg/l, respectively. The mean DO, BOD5, CODtotal, CODdissolved concentrations were 1.78, 584, 1475 and 1127 mg/l while the Total-N, NH4-N, NO3-N, NO2-N, Total-P, PO4-P and oil concentrations were measured as 15.40, 2.20, 1.80, 0.05, 10.60, 6.80 and 206 mg/l, respectively. The less hydrophobic ACL and CRB concentrations were 124.2 ng/ml and 3.60 ng/ml while the more hydrophobic BaP and BkF concentrations were measured as 5.41 and 0.64 ng/ml, respectively, in the petrochemical industry wastewater. Physical and chemical properties of the PAHs studied in this work was shown at Table 2.

Table 2: Physical and chemical properties of the PAHs studied in this work

|

PAHs

|

CAS-No |

MF |

MW

(g/ mol) |

TM

(°C) |

TB

(°C) |

Sw (25°C) (mg/l) |

VP (25°C) (mm Hg) |

H (25°C) (atm m3/mol) |

log KOA

(25°C) |

log KOW |

SORC

|

|

ACL

|

208-96-8

|

C12H8 |

152 |

93 |

280 |

16.1 |

6.68E-03 |

1.14E-04 |

6.34 |

3.94 |

23.56E+10

|

|

CRB

|

86-74-8

|

C12H9N |

167 |

246 |

355 |

1.8 |

7.50E-07 |

1.16E-06 |

8.03 |

3.72 |

24.67E+10

|

|

BkF

|

207-08-9

|

C20H12 |

252 |

217 |

480 |

0.0008 |

9.70E-10 |

5.84E-08 |

11.37 |

6.11 |

0.45E+8

|

|

BaP

|

50-32-8

|

C20H12 |

252 |

177 |

495 |

0.00162 |

5.49E-09 |

4.57E-07 |

11.56 |

6.13 |

0.32 E+8

|

| Acenaphthylene (ACL), Carbazole (CRB), Benzo[k]fluoranthene (BkF), Benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) |

| MF: Molecular Formula, MW: Molecular weight, TM: Melting point (°C), TB: Boiling point(°C), Sw: Solubility in water (mg/l), VP: Vapor pressure (mm Hg), H: Henry’s law constant (atm m3/mol), log KOA: Octanol-air coefficient, log KOW: Octanol-water coefficient, SORC: second-order reaction rate constants (ng/ml.s). |

Characterization of Photocatalysts

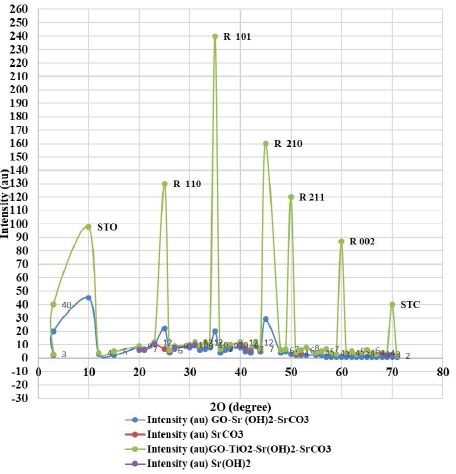

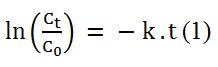

The XRD spectra of the prepared nanocomposites (GO-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 and GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3) (Figure 1). For both composite materials, the diffraction peak at about 10° is attributed to GO (Kyzas et al., 2014). For GO-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3, the broad peaks at 2θ = 25°, 28°, 36° and 43° are assigned to the crystalline phase of SrCO3 (JCPDS Card No. 005-0418), whereas weak peaks for Sr(OH)2, Sr(OH)2·. H2O and Sr (OH)2·. 8H2O were also observed as confirmed by JCPDS Cards Nos. 27- 0847, 28-1222, and 27-1438, respectively [52]. The XRD pattern of GOTiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 showed much sharper peaks than those of GO-Sr (OH)2/SrCO3, indicating well-developed crystalline phases. The peaks at 2θ = 25°, 28°, 36° and 43° are attributed to TiO2 belonging to the rutile phase (JCPDS Card No. 88-1175), while minor peaks from the anatase phase (JCPDS Card No. 84-1268) were also observed [53]. Besides, the peaks at 2θ = 24°, 32.7°, 40.1°, 46.6°, 57.8° and 67.9° can be attributed to the perovskite-type phase of cubic symmetry of SrTiO3 (STO) (JCPDS Card No. 86-0179) [54,55].

Figure 1: XRD patterns of GO-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 and GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposites

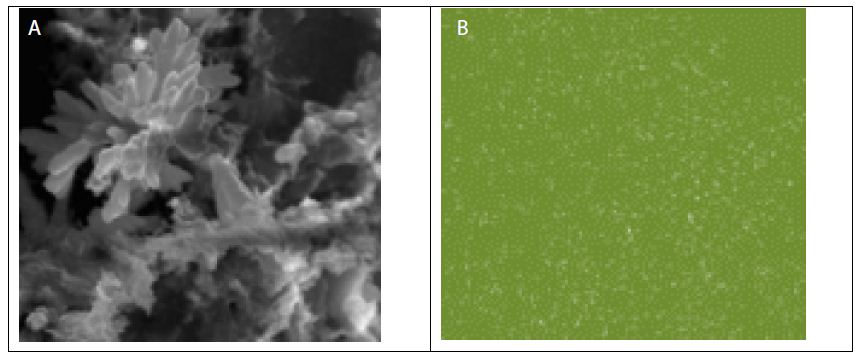

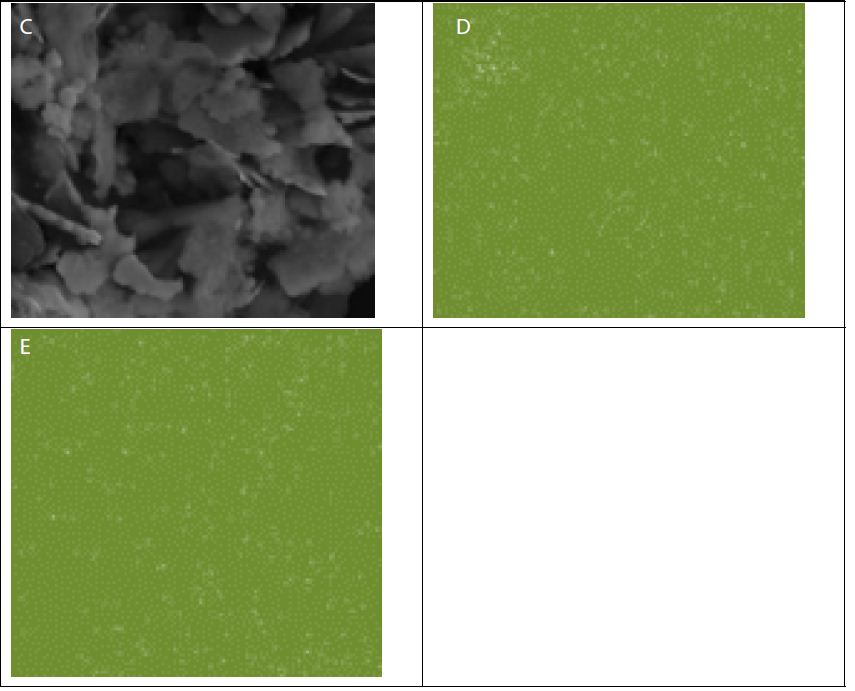

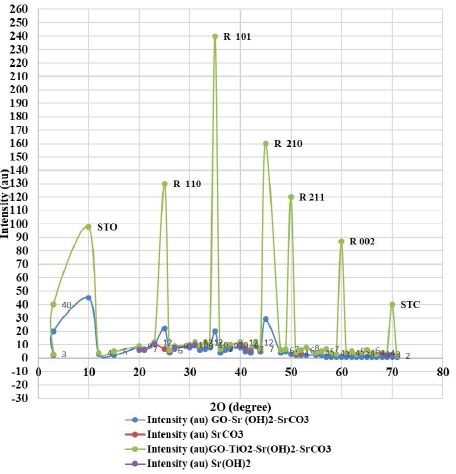

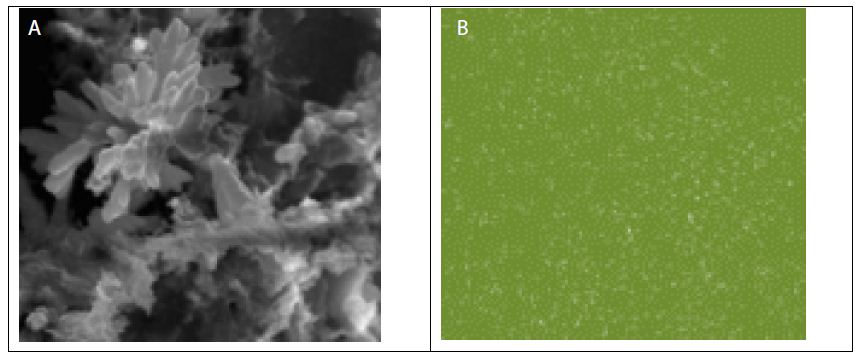

The SEM images along with the EDX maps of the elemental distribution (Figure 2) reveal that Sr and/or Ti are rather uniformly distributed in the GO-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 and GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposite matrices. The nano-rods in Figure (2a) are SrCO3, while the nanospheres on the GO surface in Figure (2c) are likely to be the aggregates of SrTiO3 nanoparticles with an average diameter of about 1 μm [56].

Figure 2: SEM images of (a) GO-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3, (b) Sr distribution map with GO-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3, (c) GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3, (d) Sr distribution map with GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 and (e) Ti distribution map

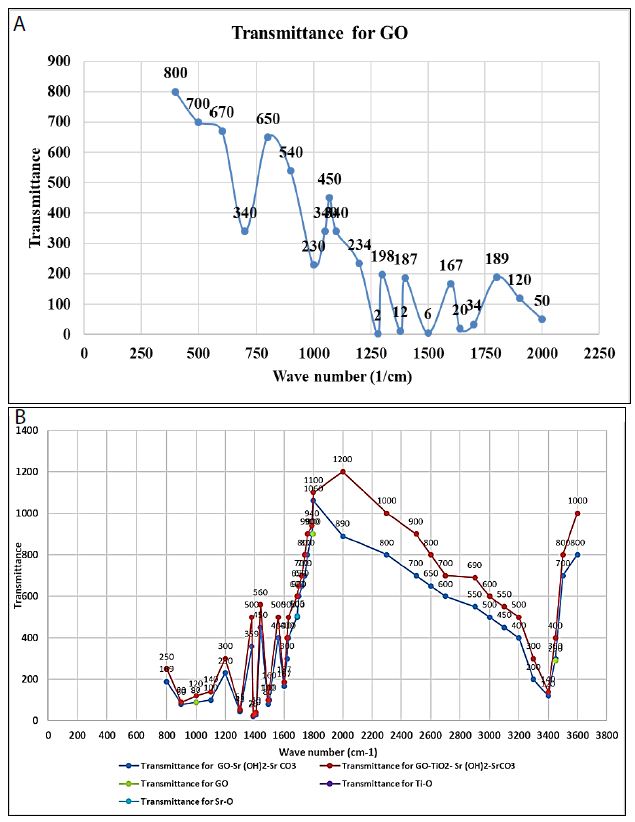

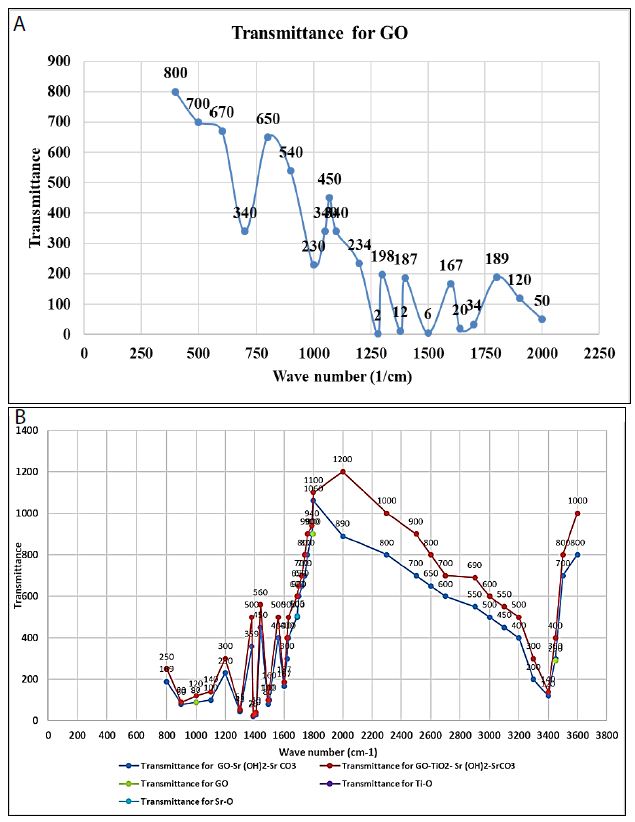

Figure (3a) shows the FTIR spectrum for GO. The characteristic bands are assigned as follows: carboxyl groups at 1070 and 1760 1/cm, C]C stretching vibration of the sp2 carbon skeletal network at 1600 1/cm, OeH groups at 1380 and 1000 1/cm, and epoxy groups at 900 1/cm [57]. The peak at 1240 1/cm can be attributed to the S]O asymmetric stretching vibrations arising from sulfones or sulfates that were formed upon graphite oxidation with H2SO4 (SI Text S1). Figure (3b) presents the FTIR spectra of the nanocomposite materials, i.e., GO-Sr (OH)2/SrCO3 and GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3. The characteristic bands of GO are clearly seen in the spectra of both nanocomposites. For GO-Sr (OH)2/SrCO3, the bands at 1071 and 1760 1/cm are attributed to the asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of the carboxylate groups. The band at 1446 1/cm is attributed to the asymmetric stretching vibration of carbonate anion (CO3 −2) in SrCO3 that has a D3h symmetry, while the bands at 860 and 600 1/cm are assigned to the vibrations of the carbonate anion due to bending out of plane and in plane, respectively (Alavi and Morsali, 2010). The bands at 3200, 1380 and 1000 1/cm are due to stretching mode of -OH groups and can be attributed to Sr(OH)2, Sr(OH)2·. H2O and Sr(OH)2·. 8H2O. For GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3, a new broad peak was observed in the range of 550-780 1/cm, which can be ascribed to the TieO stretching. The bands at 1760 and 1384 1/cm for the carboxylate groups disappeared, indicating that these groups have been bounded to TiO2. The bands at 3200, 1384 and 1020 1/cm were diminished, indicating that less crystalline phases of Sr(OH)2, Sr(OH)2.H2O and/or Sr(OH)2·. 8H2O were formed (Alavi and Morsali, 2010).

Figure 3: FTIR spectra of (a) GO and (b) GO-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 versus GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposites

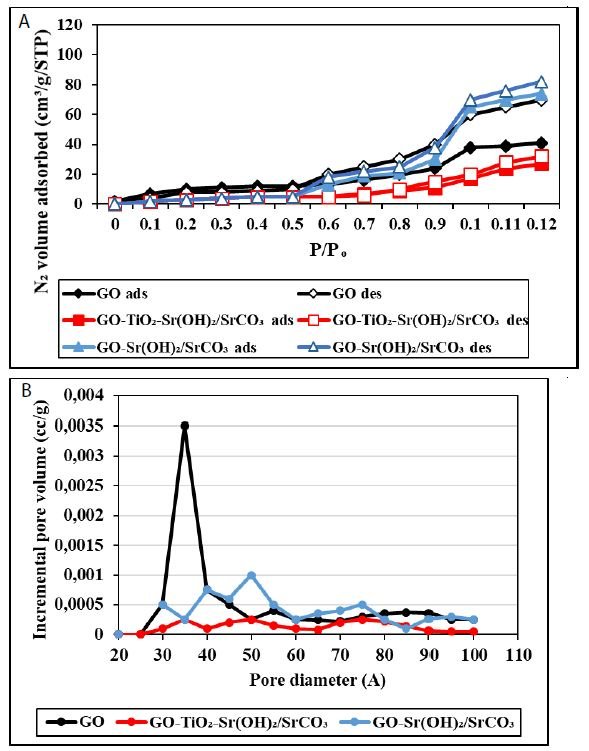

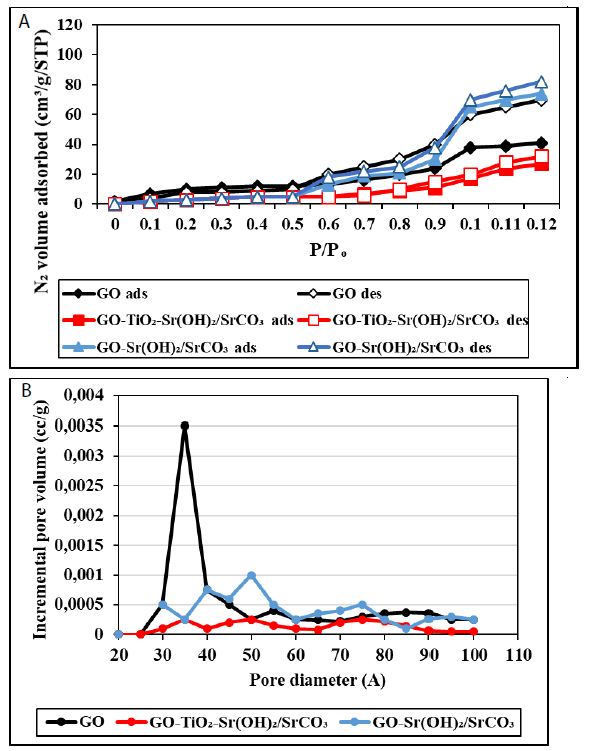

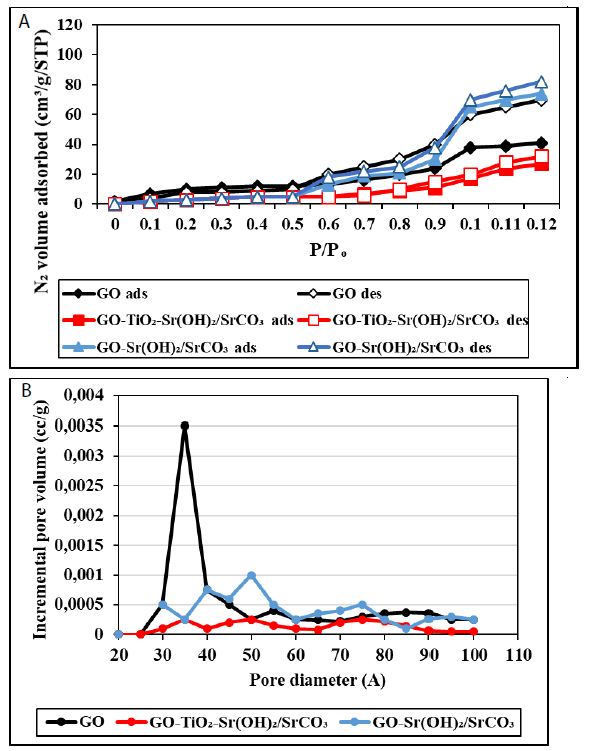

The textural features of the nanocomposites were investigated with the N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms and the results are shown in Figure 4a. According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), the shape of the isotherm for the GO-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposite can be classified as a combination of Type II and Type III, indicating the coexistence of mesopores and macropores [58]. The deviation of the desorption isotherm from the adsorption isotherm (hysteresis) can be attributed to the presence of slit or bottle neck pores. The isotherm displayed a significant increase of N2 uptake at P/Po > 0.95, indicating the presence of external surface area and/or textural porosity. In contrast, the isotherm for GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 conforms to the Type II isotherm, which is characteristic of low-porosity materials or materials with large macropores. The decrease of the mesopores and macropores volume in GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 can be attributed to occupying part of the pores by TiO2 and SrTiO3 reaction products. The inset in Figure 4b presents the pore size distributions for GO, GO-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 and GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 estimated by the density functional theory (DFT) calculations of the N2 adsorption data. The presence of mesopores and macropores is clearly evident in GO, which are then sharply diminished with the addition of Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 and TiO2. Moreover, the specific surface area of GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 (5.64 m2/g) was found 75% less than that of GO-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 (21.47 m2/g), and the pore volume of GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 (0.0319 cm3/g) was 84% less than that of GO-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 (0.1842 cm3/g).

Figure 4: (a) Nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms and (b) pore size distribution of GO, GO-Sr (OH)2/SrCO3 and GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3

Effect of Increasing GO Nanoparticle Concentrations during Hydrophobic PAHs Treatment with Photocatalytic Degradation Under Sun Light İrradiation

Preliminary studies showed that the optimum sun light intensity, irradiation time, pH, and temperature were 100 mW/cm2, 360 min, pH = 7.0 and at 22°C, respectively in the presence of 7 mg/l GO nanocomposite concentration (data not shown). The effects of increasing GO nanoparticle concentrations (2 mg/l, 4 mg/l and 8 mg/l) on the removals of PAHs [less hydrophobic (ACL, CRB) and more hydrophobic (BaP, BkF)] under a sun light intensity of 100 mW/cm2, at a sun light irradiation time of 360 min, at pH = 7.0 and at 22°C, respectively (Table 3; SET 1). The maximum removals of ACL, CRB, BaP and BkF hydrophobic PAHs were 87%, 87%, 85% and 84% at 8 mg/l GO nanoparticle concentration under a sun light intensity = 100 mW/cm2, at a photocatalytic powerof 100 W, at sun light irradiation time of 360 min, at a pHof 7.0 and at 22°C, respectively (Table 3; SET 1). The increasing GO nanoparticle concentrations were positively affect the photocatalytic degradation of hydrophobic PAHs (ACL, CRB, BaP and BkF) (Table 3; SET 1).

Table 3: Effect of increasing experimental parameters on photocatalytic degradation of hydrophobic PAHs in a petrochemical industry wastewater under sun light irradiaiton process, at sun light intensity=100 mW/cm2, at pH=7.0 and at 22°C, respectively (n=3, mean values)

|

Set

|

Parameters |

Hydrophobic PAHs removals (%) |

| Less hydrophobic |

More hydrophobic

|

|

ACL

|

CRB |

BaP |

BkF

|

| 1 |

GO nanoparticle concentrations (mg/l) |

|

|

2 |

54

|

56 |

59 |

58

|

|

4 |

71

|

73 |

70 |

69

|

|

8 |

87

|

87 |

85 |

84

|

| 2 |

TiO2 nanoparticle concentrations (mg/l) |

|

|

1 |

59

|

57 |

64 |

75

|

|

3 |

63

|

66 |

77 |

81

|

|

6 |

76

|

78 |

83 |

86

|

|

9 |

89

|

90 |

91 |

92

|

| 3 |

GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposite concentrations (mg/l) |

|

|

1 |

76

|

75 |

80 |

92

|

|

2 |

89

|

84 |

86 |

97

|

|

4 |

97

|

98 |

98 |

99

|

| 4 |

Sun light irradiation times (min) |

|

|

30 |

56

|

61 |

60 |

65

|

|

120 |

65

|

68 |

65 |

66

|

|

240 |

74

|

76 |

72 |

79

|

|

360 |

81

|

80 |

84 |

84

|

| 2 |

Photocatalytic Powers (W) |

|

|

10 |

56

|

62 |

67 |

69

|

|

50 |

69

|

70 |

78 |

74

|

|

100 |

84

|

86 |

88 |

89

|

Effect of Increasing TiO2 Nanoparticle Concentrations during Hydrophobic PAHs Treatment with Photocatalytic Degradation Under Sun Light Irradiation

The preliminary studies showed that the optimum removals for PAHs [less hydrophobic (ACL, CRB) and more hydrophobic (BaP, BkF)] were obtained at a TiO2 concentration of 8 mg/L under sun light intensity of 98 mW/cm2, at photocatalytic power of 95 W, at sun light irradiation time of 350 min, at pH = 7.1 and at a temperature of 22°C (data not shown). The effects of increasing TiO2 nanoparicle concentrations (1 mg/l, 3 mg/l, 6 mg/l and 9 mg/l) were measured to detect the PAHs yields [less hydrophobic (ACL, CRB) and more hydrophobic (BaP, BkF)] under a sun light intensity of 100 mW/cm2, at photocatalytic power = 100 W, at sun light irradiation time of 360 min, ata pH = 7.0 at 22°C (Table 3; SET 2). The removals of BaP, BkF, ACL and CRB PAHs increased from 75% up to 86% as the TiO2 nanoparticle concentrations was increased from 1 mg/l up to 6 mg/l, whereas 1-3 mg/l TiO2 nanoparicle concentrations dis not significantly contribute to the hydrophobic PAHs (ACL, CRB, BaP and BkF) removals (Table 3; SET 2). The maximum 89%ACL, 90%CRB, 91%BaP and 92%BkF hydrophobic PAHs removals were detected at 9 mg/l TiO2 nanopartilce concentration, under a sun light intensity = 100 mW/cm2, at a photocatalytic powerof 100 W, at sun light irradiation time of 360 min, at a pHof 7.0 and at 22°C, respectively (Table 3; SET 2). The increasing of TiO2 nanoparticle concentrations positively affected the photocatalytic degradation of hydrophobic PAHs (ACL, CRB, BaP and BkF) during sun light irradiation process (Table 3; SET 2).

Effect of Increasing GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 Nanocomposite Concentrations during Hydrophobic PAHs Treatment with Photocatalytic Degradation under Sun Light Irradiation

Based on the preliminary studies the optimum removals of some less hydrophobic (ACL, CRB) and more hydrophobic (BaP, BkF)] PAHs were researched at a sun light intensity of 100 mW/cm2, at photocatalytic power = 100 W, at sun light irradiation time = 360 min, at pH = 7.0 and at 22°C, respectively at a GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 concentrations of 3 mg/l (Table 3; SET 3). The removals in BaP, BkF, ACL and CRB increased from 92%, up to 99% as the GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposite concentration was increased from 1 up to 4 mg/l, at a sun light intensity = 100 mW/cm2, at a photocatalytic power = 100 W, ata sun light irradiation time = 360 min, at 22°C (Table 3; SET 3). The maximum 97%ACL, 98%CRB, 98%BaP and 99%BkF hydrophobic PAHs removals were found at 4 mg/l GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposite concentration under a sun light intensity = 100 mW/cm2, at a photocatalytic powerof 100 W, at sun light irradiation time of 360 min, at a pHof 7.0 and at 22°C, respectively. The increasing GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposite concentrations were found to be positively affect for the photocatalytic degradation of hydrophobic PAHs (ACL, CRB, BaP and BkF) (Table 3; SET 3).

An optimum GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposite concentration of 4 mg/l increase the ionic strength of the aqueous phase, driving the PAHs to the bulk-bubble interface in a photocatalytic reactor. This, increases the partitioning of the PAH species upon radical scavengers in a photocatalytic reactor. Beyond the partitioning enhancement, the presence of salt reduces the vapor pressure and increases the surface tension of the PAHs [59]. Therefore, the solubility of the solution decreases and the diffusion of solutes decreases from the bulk solution to the bubble-liquid interface with administration of decreasing GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposite concentrations in the photocatalytic reactor [60]. The high PAH removals in raised GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposite concentrations can be explained by the fact that a higher amount of GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposite will create more salting out effect than the lower amount and thus increase the interfacial concentration of the PAHs. In our study, no contribution of GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposite >4 mg/l to the PAH yields could be attributed to the sinergistic and antagonistic effects of the by-products and to the more hydrophobic (BaP, BkF) and less hydropholic (ACL, CRB) nature of PAHs present in petrochemical industry wastewaters (Table 3; SET 3).

Effect of Increasing Sun Light Irradiation Times during Hydrophobic PAHs Treatment with Photocatalytic Degradation Under Sun Light Irradiation

The effects of increasing sun light irraditiaon times (30 min, 120 min, 240 min and 360 min) were measured in PAHs [less hydrophobic (ACL, CRB) and more hydrophobic (BaP, BkF)] under sun light intensity = 100 mW/cm2, at photocatalytic power = 100 W, at pH = 7.0 at 22°C, respectively (Table 3; SET 4).

The removals of BaP, BkF, ACL and CRB increased from 56-65% up to 72-79% as the sun light irradiation times was increase from 30 min up to 240 min, whereas 30-120 min sun light irradiation times dis not significantly contribute to the hydrophobic PAHs (ACL, CRB, BaP and BkF) removals was not observed (Table 3; SET 4). The maximum 81%ACL, 80%CRB, 80%BaP and 84%BkF hydrophobic PAHs removals were indicated at 360 min sun light irradiaiton time, under sun light intensity = 100 mW/cm2, at photocatalytic power = 100 W, at pH = 7.0 and at 22°C, respectively (Table 3; SET 4). The increasing sun light irradiaiton times were affected positively effect for the photocatalytic degradation hydrophobic PAHs (ACL, CRB, BaP and BkF) during sun light irradiation process (Table 3; SET 4).

Effect of Increasing Photocatalytic Powers During Hydrophobic PAHs Treatment with Photocatalytic Degradation Under Sun Light Irradiation

The effects of increasing photocatalytic powers (10 W, 50 W and 100 W) were measured in PAHs [less hydrophobic (ACL, CRB) and more hydrophobic (BaP, BkF)] under sun light intensity = 100 mW/cm2, at sun light irradiation time = 360 min, at pH = 7.0 at 22°C, respectively (Table 3; SET 5).

The removals of BaP, BkF, ACL and CRB increased from 56-69% up to 69-78% as the photocatalytic powers was increase from 10 W up to 50 W, whereas 10-50 W photocatalytic powers dis not significantly contribute to the hydrophobic PAHs (ACL, CRB, BaP and BkF) removals was not obtained (Table 3; SET 5). The maximum 84%ACL, 86%CRB, 88%BaP and 89%BkF hydrophobic PAHs removals were indicated at 100 W photocatalytic power, under sun light intensity = 100 mW/cm2, at sun light irradiation time = 360 min, at pH = 7.0 and at 22°C, respectively (Table 3; SET 5). The increasing photocatalytic powers were affected positively effect for the photocatalytic degradation hydrophobic PAHs (ACL, CRB, BaP and BkF) during sun light irradiation process (Table 3; SET 5).

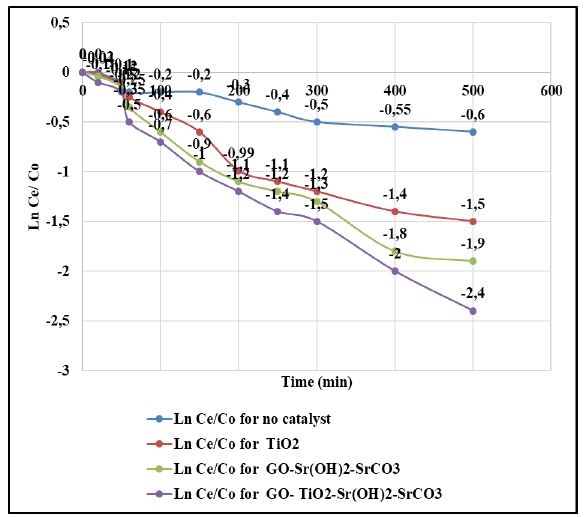

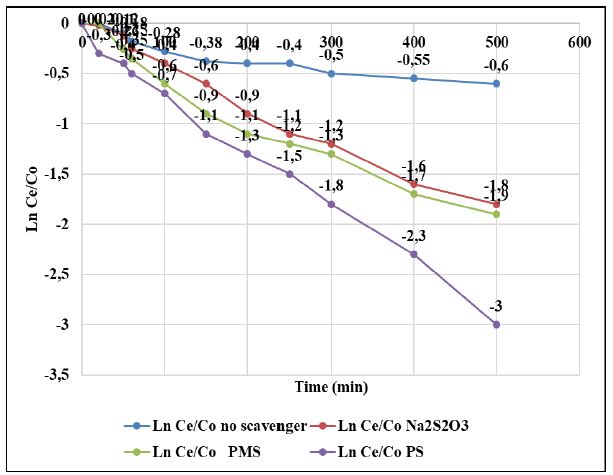

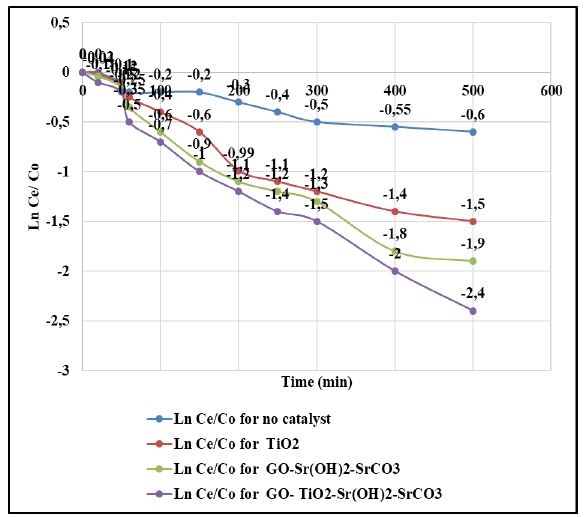

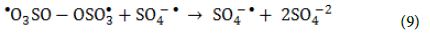

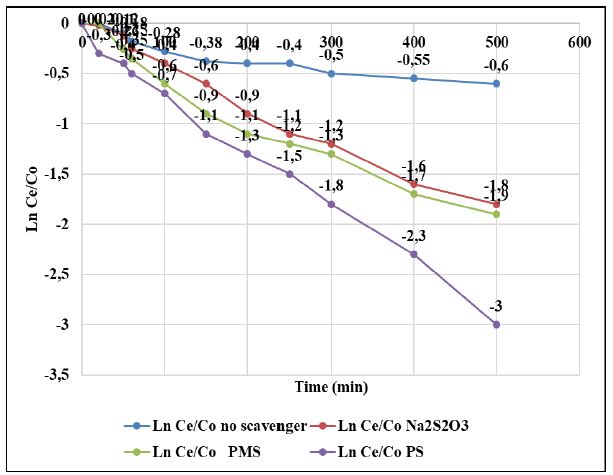

Photocatalytic Activity

PAHs is resistant to photolysis under sun light [61]. The control tests showed that nearly 85% of PAHs still retained in the solution after 360 min sun irradiation time (Table 4 and Figure 5) and the pseudo-first-order rate constant was k = 0.0006 ± 0.0001 1/min. The addition of TiO2 nanoparticle enhanced the photodegradation rate by 3 folds (k = 0.0016 1/min) (Table 4 and Figure 5). The addition of GO increased the photodegradation yield (k = 0.0019 ± 0.0001 l/min) (Table 4 and Figure 5). The UV light in the sun light irradiation is the main driving energy for the photocatalytic activity of TiO2. The synthesized GO-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 showed a slightly better photocatalytic activity (k = 0.0021 ± 0.0001 1/min) than TiO2 and GO nanoparticle (Table 4 and Figure 5). As expected, the GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposite exhibited the highest photocatalytic activity and greatly accelerated the photocatalytic degradation rate. It was shown a synergistic interaction among the three nanocomponents, i.e., GO, TiO2 and Sr(OH)2/SrCO3, which can facilitate utilization of both UV and visible light energy in the sun light irradiation.

Table 4: The rate constants of GO, TiO2 and GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 after photocatyalytic degradation with sun light irradiation process

|

Sun light irradiaiton time (min)

|

k (1/min) |

| Control |

GO |

TiO2 |

GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3

|

|

30

|

0.0001 ± 0.00001

|

0.0005 ± 0.0001 |

0.0004 ± 0.0001 |

0.0009 ± 0.0001

|

| 120 |

0.0003 ± 0.0001 |

0.0011 ± 0.0001 |

0.0009 ± 0.0001 |

0.0013 ± 0.0001

|

|

240

|

0.0005 ± 0.0001 |

0.0014 ± 0.0001 |

0.0012 ± 0.0001 |

0.0017 ± 0.0001 |

| 360 |

0.0006 ± 0.0001 |

0.0019 ± 0.0001 |

0.0016 ± 0.0001 |

0.0021 ± 0.0001

|

Figure 5: Photocatalytic degradation of PAHs by various synthesized catalysts, at light intensity = 100 mW/cm2, at solution volume = 250 ml, at initial PAHs concentration = 1 mg/l, catalyst dosage = 50 mg/l, at sun light irradiation time = 360 min, at pH=7.0 and at 22°C

In the photocatalytic activity of GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 firstly, the hybridization of the two coupling semiconductors (TiO2 and Sr(OH)2/SrCO3) shifted the optical absorption to the higher wavelength region and impel the transfer of photo-excited electron and holes to opposite directions (data not shown) [62]. Secondly, the GO sheets can further promote the transport of the photo-excited electrons, and thus inhibit the recombination of electrons and holes. And thirdly, the reaction product SrTiO3 has high photocatalytic activity and can also contribute to the enhanced photodegradation of PAHs.

Contribution of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) on the Photocatalytic Yields of PAHs

In generally, photocatalytic oxidation processes, ROS (potassium peroxymonosulfate (PMS, HSO5–), potassium persulfate (PS, K2S2O8) and the quenching agent sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3) generated during the photocatalytic reactions are mainly responsible for the degradation of organic pollutants [63]. Preliminary studies showed that among the concentrations studied with 1.1 mg/l PMS, 0.9 mg/l PS and 0.79 mg/l Na2S2O3 highest photooxidaton yields was detected.

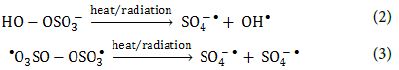

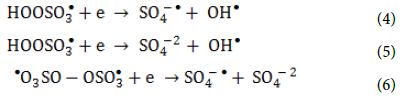

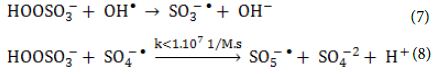

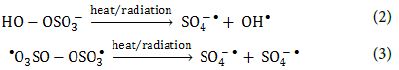

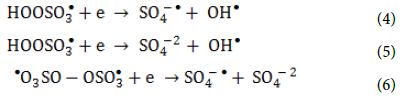

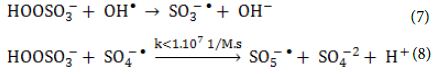

PS and PMS can undergo homolytic dissociation of the peroxide bond from radiation or thermal activation and give SO4-● radicals, and sulfate and OH● radicals, respectively (Equation 2 and Equation 3).

The oxidants can also act as electron acceptors of the photo-excited electron from the conduction band of the GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 and through electron transfer mechanisms to give additional sulfate and hydroxyl radicals based on the reactions listed below (Equation 4, Equation 5 and Equation 6) [64-66].

Heat activation of oxidants did not contributed on radical formation because of the temperature in the reactor and the relatively short treatment times compared to what was reported needed in the literature. On the other hand, homolytic dissociation of the peroxide bond of the oxidants through radiation seems to be a more probable mechanism. Even though, both oxidants have low absorption in the UVA range, the adsorption of PS at λ = 365 nm is four times the one of PMS, when measured in solutions of the same concentration of active species. This indicates that PS has a better ability to adsorb photons compared to PMS and therefore, more radicals can be formed. The remaining PMS and form peroxymonosulfate radicals (SO5-●) (Equation 7 and Equation 8) that have significantly reduced oxidation ability and higher selectivity (redox potential 1.1 V, at pH = 7.0) to SO4-● radicals (Table 5).

On the other hand, reaction of PS with a SO4-● radical will cause the formation of another SO4-● radical (Equation 9) which leaves the oxidative capacity of the system unaltered. The effects of (PMS, HSO5–), (PS, K2S2O8) and Na2S2O3 on the photocatalytic degradation rates of the studied BkF PAH were tabulated (Table 5).

Table 5: Contributions of ROS to photocatalytic degradation of BkF PAH by GO-TiO2-Sr (OH)2/SrCO3 under simulated solar irradiation

|

Scavengers

|

Scavenging radicals |

k (1/min)

|

| None (Only GO-TiO2-Sr (OH)2/SrCO3) |

–

|

0.0061

|

| PMS |

HSO5 –

|

0.0062

|

| PS |

K2S2O8

|

0.0067

|

| Na2S2O3 |

SO4-2

|

0.0063

|

Photodegradation Pathway

At Table 6 and Figure 6 presents the reaction intermediates during the photocatalytic degradation of hydrophobic PAHs (ACL, CRB, BaP and BkF) by GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 under sun light irradiation process. It is noteworthy that the reaction rate and selectivity can be altered by the reaction matrix. For example, using dimethyl carbonate instead of water as the medium, the selectivity of TiO2 for the partial photooxidation of hydrophobic PAHs (ACL, CRB, BaP and BkF) was enhanced.

Table 6: By-products of BkF, BaP and ACL PAHs at sun light intensity = 100 mW/cm2, at solution volume= 250 ml, at initial PAHs concentration = 1 mg/l, at pH=7.0 ± 0.2, at 22°C, at 360 min sun light irradiaiton time, respectively (n=3, mean ± SD)

|

PAHs name

|

Initial PAH concentration (ng/ml) |

Photocatalytic degradation metabolites (ng/ml)

|

| BkF |

0.804 ± 0.001

|

benzoic acid: 0.21 ± 0.002

FL: 0.59 ± 0.005

|

| BaP |

0.077 ± 0.003 |

benzoic acid: 0.028 ± 0.001

PY: 0.0040 ± 0.00014 |

| ACL |

53.42 ± 0.05 |

NAP: 44.13 ± 0.07 |

Figure 6: Photocatalytic degradation of PAHs by GOTiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 in the various radical scavengers, at sun light intensity = 100 mW/cm2, at solution volume= 250 ml, at initial PAHs concentration = 1 mg/l, at catalyst dosage = 50 mg/l, at pH=7.0 ± 0.2, T=22 ± 1°C, at TBA dosage = 200 mg/l, at NaN3 dosage = 200 mg/l, at BQ dosage = 200 mg/l and at CAT dosage = 4000 U/ml, respectively

Determination of the Acute Toxicity of Studied PAHs on Daphnia magna before and after Treatment of Hydrophobic PAHs Under Photocatalytic Degradation at Different Experimental Conditions

The raw petrochemical industry wastewater samples induced 95% motility inhibition to Daphnia magna cells (Table 7). This inhibition could be attributed to the mixed reacalcitrant carcinogenic hydrophobic PAHs with high benzene rings and to the synergistic effects of the aforementioned more hydrophobic PAHs with less hydrophobic PAHs in petrochemical industry wastewaters. When Daphnia magnas were exposed to the effluent samples treated withonly photolysis without catalyst at 22°C for 360 min sun light irradiaiton time a significant reduction in inhibition (10.01%) was not observed (the inhibition decreased from initial 98% to 88%). In other words, photolysis alone was not sufficient to remove the toxicity of recalcitrant by-products from the petrochemical wastewater (Table 7). The maximum removals in inhibition were observed in photocatalytic degraded petrochemical wastewater containing 8 mg/l GO nanoparticle, 9 mg/l TiO2 nanoparticle and 4 mg/l GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposite concentrations at a neutral pH = 7.0 after 360 min sun light irradiation time at 22°C. A decreasing toxicity trend due to long sun light irradiaiton time with catalyst can be explained by the formation of less toxic by-products over time. The petrochemical wastewater containing TiO2 nanoparticles >10 mg/l displayed toxicity to Daphnia magna after 360 min sun light irradiation time. Similarly, GO nanoparticle and GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposite concentrations >10 mg/l and >6 mg/l caused inhibition to Daphnia magna motility after 360 min sun light irradiation time at 22°C. A significant corrrelation between Daphnia manga acute toxicity and TiO, GO and GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposite concentrations was observed after 360 min sun light irradiation time according to multiple regression analysis (R2 = 0.87, F = 17.99. p = 0.001).

Table 7: Effect of sun light irradiaiton times during photocatalytic degradation process on the acute toxicity (EC50) removal efficiencies at different operational conditions at pH=7.0, at 22°C (n=3, mean values)

|

Sets

|

IAT

|

Operational conditions

|

| |

PDA at 22 °C (Control)

|

GO |

TiO2 |

GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3

|

|

EC50

t=0

|

ATRi |

SLIT a |

EC50

|

ATR |

GO b |

EC50

t=360 |

ATRe |

TiO2 c |

EC50 t=360 |

ATRe |

GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3d |

EC50

t=360 |

ATRe

|

|

1

|

342.56

|

98 |

30 |

359.04 |

2.01 |

2 |

631.05 |

99.99 |

1 |

484.67 |

67 |

1 |

590.56 |

97.00 |

| 2 |

342.56 |

98 |

120 |

364.78 |

6.23 |

4 |

604.67 |

90.00 |

3 |

545.56 |

78 |

2 |

626.56 |

99.00

|

|

3

|

342.56 |

98 |

240 |

377.67 |

8.34 |

8 |

540.78 |

76.99 |

6 |

587.45 |

94 |

4 |

630.45 |

99.94 |

| 4 |

342.56 |

98 |

360 |

380.12 |

10.01 |

|

|

|

9 |

504.67 |

70 |

|

|

|

| IAT: Initial acute toxicity; a: sun light irradiation times (min); b: GO concentration (mg/l); c: TiO2 nanoparticle concentrations (mg/l); d: GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposite concentration (mg/l); PDA: Photocatalytic degradation alone without additives (Control); EC50 t=0 : Initial acute toxicity before photocatalytic degradation (ng/ml); ATRi: Initial inhibition percentage before photocatalytic degradation; EC50 : Acute toxicity after photocatalytic degradation in control versus sun light irradiation time (ng/ml); ATR: Acute toxicity removal (%) in control versus sun light irradiation time; ATRe: Acute toxicity removal (%) after 360 min sun light irradiation time; EC50 t=360 : acute toxicity after 360 min sun light irradiaiton time (ng/ml). |

Toxicity results showed that both high concentrations of GO, TiO2 and GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 influence the toxicity of PAH mixtures which may interact with the PAHs and their degraded metabolites to form different by-products during photocatalytic degradation. These by-products exhibit synergistic and antagonistic toxicity effects on Daphnia magna as well. The effective PAH concentrations caused 50% mortality in Daphnia magna cells (EC50 value as ng/ml) increased from initial 342.56 ng/ml to EC50 = 631.05 ng/ml, at pH = 7.0 and at 22°C after 360 min sun light irradiation time resulting in a maximum acute toxicity removal of 99.99% at 1 mg/l GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocompoasite concentration (Table 7; SET 1). The EC50 value increased from initial 342.56 ng/ml to EC50 = 587.45 ng/ml at a TiO2 concentration of 6 mg/l after 360 min sun light irradiation time, at pH = 7.0 and at 22°C resulting in a maximum acute toxicity removal of 94.00% (Table 7; SET 3). The EC50 value increased from initial 342.56 ng/ml to EC50 = 630.45 ng/ml at 8 mg/l GO nanopartilce concentration was measured to 99.94% maximum acute toxicity removal, at pH = 7.0, at 22°C after 360 min sun light irradiation time, respectively (Table 7; SET 3). In this acute toxicity reduction the EC50 value of petrochemical industry wastewater increased to EC50 = 631.05 ng/ml. Low acute toxicity removals found at high GO nanoparticle concentrations could be attributed to their detrimental effect on the Daphnia magna cells (Table 6; SET 1).

A strong significant correlation between EC50 values and PAH removals showed that the Daphnia magna acute toxicity test alone can be considered aa a reliable indicator of petrochemical wastewater toxicity (R2 = 0.87, F = 17.99. p = 0.001). Similarly, a strong linear correlation between threshold concentrations of GO, TiO2, GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 and decrease in inhibitions was observed (R2 = 0.91, F = 3.89, p = 0.001) while the correlation between the inhibition decrease and GO, TiO2 and GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposite concentrations above the threshold values was weak and not significant (R2 = 0.38, F = 3.81, p = 0.001). In this study, the Daphnia magna acute toxicity test alone can be considered a reliable indicator of petrochemical industry wastewater toxicity.

Conclusion

The results of this study showed that the hydrophobic PAHs in a petrochemical industry wastewater with high benzene rings could be removed as successfully as the less hydrophobic PAHs (ACL and CRB) and more hydrophobic PAHs (BaP and BkF) with photocatalytic degradation under sun light irradiation process. The maximum removals of ACL, CRB, BaP and BkF hydrophobic PAHs were 87%, 87%, 85% and 84% at 8 mg/l GO nanoparticle concentration under a sun light intensity = 100 mW/cm2, at a photocatalytic powerof 100 W, at sun light irradiation time of 360 min, at a pHof 7.0 and at 22°, respectively. The maximum 89%ACL, 90%CRB, 91%BaP and 92%BkF hydrophobic PAHs removals were detected at 9 mg/l TiO2 nanopartilce concentration, under a sun light intensity = 100 mW/cm2, at a photocatalytic powerof 100 W, at sun light irradiation time of 360 min, at a pHof 7.0 and at 22°C, respectively. The maximum 97%ACL, 98%CRB, 98%BaP and 99%BkF hydrophobic PAHs removals were found at 4 mg/l GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposite concentration under a sun light intensity = 100 mW/cm2, at a photocatalytic powerof 100 W, at sun light irradiation time of 360 min, at a pHof 7.0 and at 22°C, respectively.

The addition of TiO2 nanoparticle enhanced the photodegradation rate by 3 folds (k = 0.0016 1/min). The addition of GO increased the photodegradation yield (k = 0.0019 ± 0.0001 l/min). The synthesized GO-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 showed a slightly better photocatalytic activity (k = 0.0021 ± 0.0001 1/min) than TiO2 and GO nanoparticle. As expected, the GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposite exhibited the highest photocatalytic activity and greatly accelerated the photocatalytic degradation rate. It was shown a synergistic interaction among the three nanocomponents, i.e., GO, TiO2 and Sr(OH)2/SrCO3, which can facilitate utilization of both UV and visible light energy in the sun light irradiation. 1.1 mg/l PMS, 0.9 mg/l PS and 0.79 mg/l Na2S2O3 highest photooxidaton yields was detected.

The effective PAH concentrations caused 50% mortality in Daphnia magna cells (EC50 value as ng/ml) increased from initial 342.56 ng/ml to EC50 = 631.05 ng/ml, at pH = 7.0 and at 22°C after 360 min sun light irradiation time resulting in a maximum acute toxicity removal of 99.99% at 1 mg/l GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocompoasite concentration. In sum, GO-TiO2-Sr(OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposites holds the potential to serve as a highly effective and robust photocatalyst for energy-effective photodegradation of PAHs (and potentially other persistent organic pollutants) in complex water matrices, and the multiplicative model is a useful tool for predicting the photocatalytic performances under several experimental conditions.

Acknowledgements

This research study was undertaken in the Environmental Microbiology Laboratury at Dokuz Eylül University Engineering Faculty Environmental Engineering Department, Izmir-Turkey.

References

- Fu J, Sheng S, Wen T, Zhang Z-M, Wang Q, et al. (2011a) Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in surface sediments of the Jialu River. Ecotoxicology 20: 940-950. [crossref]

- Fu J, Gong Y, Zhao X, O’Reilly SE, Zhao D (2014) Effects of oil and dispersant on formation of marine oil snow and transport of oil hydrocarbons. Environmental Science & Technology 48: 14392-14399. [crossref]

- Gong Y, Fu J, O’Reilly SE, Zhao D (2015) Effects of oil dispersants on photodegradation of pyrene in marine water. Journal of Hazardous Materials 287: 142-150. [crossref]

- Fu J, Ding Y-H, Li L, Sheng S, Wen T, et al. (2011b) Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and ecotoxicological characterization of sediments from the Huaihe River, China, Journal of Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 13: 597-604. [crossref]

- Banjoo DR and Nelson PK (2005) Improved ultrasonic extraction procedure for the determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in sediments. Journal of Chromatography A, 1066: 9-18. [crossref]

- Sponza DT and Oztekin R (2010) Effect of sonication assisted by titanium dioxide and ferrous ions on Poly aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and toxicity removals from a petrochemical industry wastewater in Turkey. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology 85: 913-925

- Quesada-Peñate I, Julcour-Lebigue C, Jáuregui-Haza U.-J, Wilhelm A-M, et al. (2009) Sonolysis of levodopa and paracetamol in aqueous solutions. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 16: 610-616.

- Hoffmann MR, Martin ST, Choi W, Bahnemann DW(1995) Environmental applications of semiconductor photocatalysis. Chemical Reviews 95: 69-96.

- Sannino F, Pernice P, Imparato C, Aronne A, D’Errico G, et al. (2015) Hybrid TiO2-acetylacetonate amorphous gel-derived material with stably adsorbed superoxide radical active in oxidative degradation of organic pollutants. RSC Advances, 5: 93831-93839.

- Zeng P, Zhang Q, Zhang X, Peng T (2012) Graphite oxide-TiO2 nanocomposite and its efficient visible-light-driven photocatalytic hydrogen production. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 516: 85-90.

- Di Paola A, Garcia-López E, Ikeda S, Marcı G, Ohtani B. (2002) Photocatalytic degradation of organic compounds in aqueous systems by transition metal doped polycrystalline TiO2. Catalysis Today 75: 87-93.

- Zhao K, Zhao SL, Qi J, Yin HJ, Gao C, et al. (2016) Cu2O clusters grown on TiO2 nanoplates as efficient photocatalysts for hydrogen generation. Inorganic Chemistry Frontiers 3: 488-493.

- Qu L, Liu Y, Baek JB, Dai L (2010) Nitrogen-doped graphene as efficient metal-free electrocatalyst for oxygen reduction in fuel cells. ACS Nano 4: 1321-1326. [crossref]

- Liang Y, Li Y, Wang H, Zhou J, Wang J. (2011) Co3O4 nanocrystals on graphene as a synergistic catalyst for oxygen reduction reaction. Nature Materials 10: 780-786. [crossref]

- Guo J, Zhu S, Chen Z, Li Y, Yu Z (2011) Sonochemical synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles on graphene for use as photocatalyst, Ultrasonics Sonochemistry.18: 1082-1090. [crossref]

- Stengl V, Henych J, Vomáčka P and Slušná M (2013) Doping of TiO2-GO and TiO2-rGO with noble metals: synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic performance for azo dye discoloration. Photochemistry and Photobiology 89: 1038-1046.

- Turekian KK, Wedepohl KH (1961) Distribution of the elements in some major units of the Earth’s crust. Geological Society of America Bulletin 72: 175.

- Yousefi R, Jamali-Sheini F, Cheraghizade M, Khosravi-Gandomani S, Sáaedi A, et al. (2015)Enhanced visible-light photocatalytic activity of strontium-doped zinc oxide nanoparticles. Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 32: 152.

- Song L, Zhang S, Chen BA (2009) novel visible-light-sensitive strontium carbonate photocatalyst with high photocatalytic activity. Catalysis Communications 10: 1565-1568.

- Momenian HR, Gholamrezaei S, Salavati-Niasari M, Pedram B, Mozaffar F, et al. (2013) Sonochemical synthesis and photocatalytic properties of metal hydroxide and carbonate (M: Mg, Ca, Sr or Ba) nanoparticles. Journal of Cluster Science 24: 1031-1042.

- Márquezherrera A, Ovandomedina V, Castilloreyes B, Zapatatorres M, Meléndezlira, M, et al. (2016) J. Facile synthesis of SrCO3-Sr(OH)2/PPy nanocomposite with enhanced photocatalytic activity under visible light. Materials 9: 30. [crossref]

- Pichat PA (2007) brief overview of photocatalytic mechanisms and pathways in water. Water Science and Technology 55: 167-173. [crossref]

- Buxton GV, Greenstock CL, Helman WP, Ross AB (1988) Critical review of rate constants for reactions of hydrated electrons, hydrogen atoms and hydroxyl radicals in aqueous solution. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data 17: 513-886.

- Robertson PKJ, Lawton LA, Münch B, Rouzade J (1997) Destruction of cyanobacterial toxins by semiconductor photocatalysis. Chemical Communications 393-394. [crossref]

- Feitz AJ, Waite TD, Jones GJ, Boyden BH, Orr PT (1999) Photocatalytic degradation of the blue green algal toxin microcystin-LR in a natural organic-aqueous matrix. Environmental Science and Technology 33: 243-249.

- Lawton LA, Robertson PKJ, Cornish BJPA, Marr IL, Jaspars M (2003) Processes influencing surface interaction and photocatalytic destruction of microcystins on titanium dioxide photocatalysts. Journal of Catalysis 213: 109-113 [crossref]

- Pelaez M, de la Cruz AA, O’Shea K, Falaras P, Dionysiou DD (2011) Effects of water parameters on the degradation of microcystin-LR under visible light-activated TiO 2 photocatalyst. Water Research 45: 3787-3796. [crossref]

- Choi H, Antoniou MG, Pelaez M, De La Cruz AA, Shoemaker JA, et al. (2007) Mesoporous nitrogen-doped TiO2 for the photocatalytic destruction of the cyanobacterial toxin microcystin-LR under visible light irradiation. Environmental Science and Technology 41: 7530-7535 [crossref]

- Pelaez M, Falaras P, Likodimos V, Kontos AG, de la Cruz AA, et al. (2010) Synthesis, structural characterization and evaluation of sol-gel-based NF-TiO2 films with visible lightphotoactivation for the removal of microcystin-LR. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 99: 378- 387.

- Andersen J, Han C, O’Shea K, Dionysiou DD. (2014) Revealing the degradation intermediates and pathways of visible light-induced NF-TiO2 photocatalysis of microcystin-LR. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 154-155: 259-266.

- Fotiou T, Triantis TM, Kaloudis T, Hiskia A (2015) Evaluation of the photocatalytic activity of TiO2 based catalysts for the degradation and mineralization of cyanobacterial toxins and water off-odor compounds under UV-A, solar and visible light. Chemical Engineering Journal 261: 17-26.

- Fotiou T, Triantis TM, Kaloudis T, O’Shea KE, Dionysiou DD, et al. (2016) Assessment of the roles of reactive oxygen species in the UV and visible light photocatalytic degradation of cyanotoxins and water taste and odor compounds using C-TiO2. Water Research 90: 52-61. [crossref]

- Pelaez M, Falaras P, Kontos AG, De la Cruz AA, O’shea K, et al. (2012) A comparative study on the removal of cylindrospermopsin and microcystins from water with NF-TiO 2-P25 composite films with visible and UV- vis light photocatalytic activity. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 121-122: 30-39.

- Eberson L (1982) Electron-Transfer Reactions in Organic Chemistry, Advances in Physical Organic Chemistry 18: 79-185.

- Neta P, Huie RE, Ross AB (1988) Rate constants for reactions of inorganic radicals in aqueous solution. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data 17: 1027-1284.

- Wang Y, Hong C (1999) Effect of hydrogen peroxide, periodate and persulfate on photocatalysis of 2- chlorobiphenyl in aqueous TiO2 suspensions. Water Research.33: 2031-2036.

- Legrini O, Oliveros E, Braun AM (1993) Photochemical processes for water treatment. Chemical Reviews 93: 671-698. [crossref]

- Anipsitakis GP, Dionysiou DD (2004) Transition metal/UV-based advanced oxidation technologies for water decontamination. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 54: 155-163.

- Anipsitakis GP, Dionysiou DD, MA Gonzalez (2006) Cobalt-mediated activation of peroxymonosulfate and sulfate radical attack on phenolic compounds, Implications of chloride ions. Environmental Science and Technology 40: 1000-1007. [crossref]

- Antoniou MG, de la Cruz AA, Dionysiou DD (2010a) Degradation of microcystin-LR using sulfate radicals generated through photolysis, thermolysis and e- transfer mechanisms. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 96: 290-298.

- Antoniou MG, De La Cruz AA, Dionysiou DD (2010b) Intermediates and reaction pathways from the degradation of microcystin-LR with sulfate radicals. Environmental Science and Technology.44: 7238-7244.

- He X, de la Cruz AA, O’Shea KE, Dionysiou DD (2014) Kinetics and mechanisms of cylindrospermopsin destruction by sulfate radical-based advanced oxidation processes. Water Research 63: 168-178

- He X, de la Cruz AA, Hiskia A, Kaloudis T, O’Shea K, et al. (2015) Destruction of microcystins (cyanotoxins) by UV-254 nm-based direct photolysis and advanced oxidation processes (AOPs): Influence of variable amino acids on the degradation kinetics and reaction mechanisms. Water Research.74: 227-238. [crossref]

- Antonopoulou M and Konstantinou IK (2014) Effect of oxidants in the photocatalytic degradation of DEET under simulated solar irradiation in aqueous TiO2 suspensions. Global NEST Journal 16: 507-515.

- Augugliaro V, Baiocchi C, Prevot AB, García-López E, Loddo V, et al. (2002) Azo-dyes photocatalytic degradation in aqueous suspension of TiO2 under solar irradiation. Chemosphere .49: 1223-1230. [crossref]

- Saquib M and Muneer M (2003) TiO2/mediated photocatalytic degradation of a triphenylmethane dye (gentian violet), in aqueous suspensions. Dyes and Pigments 56: 37-49.

- Hummers Jr WS and Offeman RE (1958) Preparation of graphitic oxide. Journal of the American Chemical Society 80: 1339.

- Xu Z, Li Q, Gao S, Shang JK (2010) As(III) removal by hydrous titanium dioxide prepared from one-step hydrolysis of aqueous TiCl4 solution. Water Research 44: 5713-5721. [crossref]

- Fu J, Gong Y, Cai Z, O’Reilly SE, Zhao D (2017) Mechanistic investigation into sunlight- facilitated photodegradation of pyrene in seawater with oil dispersants. Marine Pollution Bulletin 114: 751-758.

- Lindsey ME and Tarr MA (2000) Quantitation of hydroxyl radical during Fenton oxidation following a single addition of iron and peroxide. Chemosphere 41: 409-417. [crossref]

- Eaton AD, Clesceri LS, Rice EW, Greenberg AE, Franson MAH. (2005) Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater’, Ed. by Franson MAH, (21th ed.), American Public Health Association (APHA), American Water Works Association (AWWA), Water Environment Federation (WEF), American Public Health Association (APHA)

- Alavi MA, Morsali A (2010) Syntheses and characterization of Sr(OH)2 and SrCO3 nanostructures by ultrasonic method. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 17: 132-138. [crossref]

- Thamaphat K, Limsuwan P, Ngotawornchai B (2008) Phase characterization of TiO2 powder by XRD and TEM Kasetsart. Journal of Natural Sciences 42: 357-361.

- Huang S.-T, Lee WW, Chang J-L, Huang W-S, Chou S.-Y(2014) Hydrothermal synthesis of SrTiO3 nanocubes: characterization, photocatalytic activities, and degradation pathway. Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers 45: 1927-1936.

- Wysmulek K, Sar J, Osewski P, Orlinski K, Kolodziejak K, et al. (2017) SrTiO3-TiO2 eutectic composite as a stable photoanode material for photoelectrochemical hydrogen production. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 206: 538-546

- He Z, Sun X-Y, Gu X (2017) Electrospinning fabrication of SrTiO3: Er3+ nanofibers and their applications of upconversion properties. Ceramics International 43: 7378-7382.

- Kyzas GZ, Travlou NA, Deliyanni EA (2014) The role of chitosan as nanofiller of graphite oxide for the removal of toxic mercury ions. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces113: 467-476.

- Lowell S (1979) Introduction to Powder Surface Area. John Wiley & Sons

- Chakinala AG, Gogate PR, Chand R, Bremner DH, Molina R, et al. (2008) Intensification of oxidation capacity using chloroalkanes as additives in hydrodynamic and acoustic cavitation reactors. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 15: 164-170. [crossref]

- Fu J, Kyzasc GZ, Cai Z, Deliyanni EA, Liu W, et al. (2018) Photocatalytic degradation of phenanthrene by graphite oxide-TiO2-Sr (OH)2/SrCO3 nanocomposite under solar irradiation: Effects of water quality parameters and predictive modelling. Chemical Engineering Journal 335: 290-300.

- Chen J, Peijnenburg WJGM, Quan X, Chen S, Martens D, et al. (2001) Is it possible to develop a QSPR model for direct photolysis half-lives of PAHs under irradiation of sunlight? Environmental Pollution 114: 137-143. [crossref]

- Kanagaraj T and Thiripuranthagan S (2017) Photocatalytic activities of novel SrTiO3-BiOBr heterojunction catalysts towards the degradation of reactive dyes. Applied Catalysis B Environmental 207: 218-232.

- Cavalcante RP, Dantas RF, Bayarri B, González O, Giménez J, et al. (2016) Photocatalytic mechanism of metoprolol oxidation by photocatalysts TiO2 and TiO2 doped with 5% B: primary active species and intermediates. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 194: 111-122.

- Anipsitakis GP and Dionysiou DD (2003) Degradation of organic contaminants in water with sulfate radicals generated by the conjunction of peroxymonosulfate with cobalt. Environmental Science and Technology 37: 4790-4797. [crossref]

- Konstantinou IK and Albanis TA (2004) TiO2-assisted photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes in aqueous solution: Kinetic and mechanistic investigations: A review. Applied Catalysis B Environmental 49: 1-14.

- Antoniou MG, Nicolaou PA, Shoemaker JA, de la Cruz AA, Dionysiou DD (2009) Impact of the morphological properties of thin TiO2 photocatalytic films on the detoxification of water contaminated with the cyanotoxin, microcystin-LR. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 91: 165-173.