Abstract

The rationale for the treatment and management of periodontal disease has varied over the last three to four decades and as such the clinician should be aware of these changes to manage the condition effectively. For the example, the recognition that the modification and/or removal of the dental biofilm on the tooth surface is key to reducing the impact of the oral microflora on both the hard and soft tissues of the mouth rather than concentrate on the concept of the removal of ‘calculus removal and diseased cementum of the root to achieve success. The understanding of the role of the oral flora has also changed particularly with the emergence of the key pathogen hypothesis and this concept may have an impact on how the condition is managed. The improvement in instrumentation and surgical techniques together with the adjunctive use of antimicrobials in both non-surgical and surgical procedures has also impacted on our treatment philosophy. The aim of this paper, therefore, is to provide an overview on the dynamic changes in philosophy in the treatment and management of periodontal disease.

Keywords

Periodontitis, Dysbiosis, Dental biofilm, Key pathogen hypothesis, Antimicrobial therapy, Debridement

Introduction

Periodontitis is a chronic multifactorial inflammatory disease associated with a dysbiotic biofilm that results in loss of the periodontal attachment [1]. An aberrant immune response or exaggerated dysbiotic host inflammatory reaction can lead to the destruction of the periodontium [2]. This inflammatory condition is modified by genetics, lifestyle, and environmental factors [3]. Periodontitis is a disease affecting susceptible individuals to a greater extent [4] with its severest form affecting around 11.2% globally which is the sixth-most prevalent condition in the world [5]. According to Grazaini et al. [6], periodontal treatment aims to prevent disease progression, minimize symptoms of the disease, restore lost periodontal tissue, and facilitate patients to maintain healthy periodontium. Biofilm control has however, remained an important strategy to halt disease progression and restore periodontal health [7]. Successful periodontal treatment requires significant ecological changes throughout the oral cavity, leading to the conversion from dysbiosis to a homeostasis ecology. It has been highlighted that increasing the proportion of bacteria associated with health and reducing the level and proportion of bacteria associated with the disease is the key to achieving periodontal stability [8]. Recently, the new 2017 periodontal classification had been proposed which allows for a multidimensional diagnostic classification by providing more detail on the classification of periodontal disease [9,10]. Staging describes the severity of the disease and the anticipated complexity of treatment, whereas grading describes the rate of progression of periodontal disease, susceptibility to disease or case phenotype as well as the presence of risk factors [9].

The Dental Biofilm and Calculus Formation

The dental biofilm is a microbial community associated with a hard, non-shedding surface and enclosed in an extracellular polymeric substance matrix. Teeth in the oral cavity provide non-shedding surfaces and a moist environment which are essential requirements for bacterial colonization and the formation of dental biofilms [11]. Biofilm formation starts with the adsorption of a conditioning film (acquired pellicle) that is coated by biologically active proteins, phosphoproteins, and glycoproteins. Early bacterial colonizers (Streptococci species) have adhesins that allow them to attach with the receptors found on the acquired pellicle. Co-adhesion or attachment between the bacteria is promoted by Fusobacterium nucleatum since this specific species can co-adhere to most oral bacteria. Consequently, multiplication of the attached cells leads to an increase in biomass and synthesis of exopolymers forming a biofilm matrix. This matrix is more than just a scaffold for the biofilm since it can bind and retain molecules, including enzymes, and it could also retard the penetration of charged molecules thereby protecting bacteria in the biofilm. Detachment of the attached cells in the late stage allows the matured biofilm to colonize further elsewhere with more favorable environments [8]. The early colonizers (e.g., Streptococcus and Actinomyces spp.) consume oxygen and lower the redox potential of the environment, which favors the growth of anaerobic species. Several of the gram-positive early colonizers utilize sugars as their energy source. The bacteria that predominate in mature plaque are anaerobic and asaccharolytic (e.g., they do not break down sugars), and use amino acids and small peptides as their energy sources instead. Furthermore, it is recognized that while a pathogenic biofilm is a prerequisite for disease formation it does not in itself necessarily cause periodontal disease [3]. The overgrowth of commensal organisms rather than the acquisition of exogenous pathogens is supported as a key mechanism for developing periodontal disease [12]. Comparison between supragingival and subgingival biofilms showed a difference in several aspects due to the different habitats and environment(s). The “Keystone pathogen hypothesis” is a concept in which specific periodontal pathogens could evade the host response and remodel the microbial community promoting dysbiosis [13]. Keystone species are found in low abundance yet have a profound impact on the biofilm community. Their main function(s) in impairing the host defense are to inhibit IL-8 function, complement subversion, and TLR4 antagonism [14]. Consequently, the host-protective mechanisms are impaired, allowing the overgrowth of the entire community. P. gingivalis has been recognized as the main keystone pathogen since it contains lipopolysaccharide (LPS), gingipains, and fimbriae which allow them to interact with TLR, cleave complement, attach to a cell, and invade intracellularly [14,15].

Dental calculus is a mineralized biofilm composed primarily of calcium phosphate mineral salts and covered by an unmineralized bacterial layer [16]. Following the mineralization process, dental calculus loses its microbial virulence. Early studies revealed that autoclaved calculus did not elicit pronounced inflammation or abscess formation [17]. There is also evidence suggesting that a normal epithelial attachment can be formed on calculus previously treated with chlorhexidine [18]. However, dental calculus provides a roughened surface that harbors a living, nonmineralized biofilm. It increases the rate of biofilm formation, reduces the drainage of GCF, and serves as a secondary retentive site for toxic bacterial products. The rate of calculus formation may differ depending on location (e.g., proximity to a salivary gland), diet (alkaline foods), and salivary content (higher level of calcium, phosphate, and lower levels of potassium in heavy calculus formers) [19]. The mineralization process appears to be almost completed within 12 days, but half of the mineralization process occurs during the first two days [20].

There is a positive correlation between the presence of dental calculus and the prevalence of gingivitis, however; no cause-effect relationship between calculus and disease initiation and progression has been established. It has been demonstrated that signs of chronic inflammation were also observed when subgingival calculus was presented [21]. Furthermore, the intensity of inflammation was more intense with the presence of remnant dental calculus [22]. Mombelli et al. [23] compared a thoroughly root surface planing to only chipping off large calculus deposits during a surgical procedure. Clinical and microbiological parameters showed similar improvements one year after therapy. The conclusion was that the reduction of subgingival microorganisms was more critical for the success of the treatment than the removal of contaminated root cementum and mineralized deposits by root planing. The concept of intentional removal of cementum was therefore abandoned as this was considered unnecessary for successful treatment.

Non-surgical Periodontal Therapy

Non-surgical periodontal therapy together with self-performed plaque control aims to control the biofilm and level of inflammation and subsequently restore periodontal health. Previously, non-surgical periodontal therapy was considered only a preparatory measure for periodontal surgery and was not performed as a solo treatment. Results from studies from the Minnesota group [24], however, provided a better understanding of the role of non-surgical treatment. These findings provided a comparison between surgical and non-surgical approaches where it was shown that in pockets up to 6 mm, non-surgical treatment could provide a similar clinical outcome compared to surgical treatment. Nevertheless, in deep sites (>7 mm), additional surgical procedures could lead to an improvement in pocket reduction. From this point, scaling, and root planning as part of non-surgical periodontal treatment could be considered as a solo effective treatment for the treatment of mild to moderate periodontitis cases. Clinical studies attempting to assess clinical outcomes following non-surgical treatment indicated that significant improvement could be observed after one month following non-surgical treatment. This finding suggested that the need for periodontal surgery could not be properly assessed until the hygienic phase has been accomplished [25]. Non-surgical periodontal treatment is, therefore, considered to be a prerequisite and the fundamental step before any type of surgical periodontal therapy [7]. Furthermore, only deep pockets (>6 mm) in periodontal surgery procedures (open flap debridement) resulted in more PPD reduction and CAL gain, indicating that periodontal surgery appeared to be beneficial only in deep sites. In addition, the concept of ‘critical probing depth’ could also be applied to facilitate the decision-making process of when to treat specifically with non-surgical periodontal treatment or when additional surgical invention is required [26]. This concept demonstrated that only pockets more than 5.5 mm would benefit from periodontal surgery (Modified Widman flap) whereas in shallower pockets (≤5.5 mm), only non-surgical periodontal treatment could achieve a similar clinical outcome.

Recent Changes in the Diagnosis and Management of Periodontal Disease

According to the recent S3 level clinical guidelines for the treatment of stage I-III periodontitis [27], the first step in therapy focuses on guiding behavior change of the patient to control the supragingival biofilm and risk factors together with oral hygiene instruction, professional mechanical plaque removal (PMPR), smoking cessation, and improving diabetic control. For example, patients who managed to quit smoking showed improved outcomes of non-surgical treatment compared to oscillators or non-quitters [28].

The Role of Instrumentation in the Management of Periodontal Disease

Subgingival instrumentation is an accepted part of the cause-related therapy or the second step of therapy. This step aims to control the subgingival biofilm and calculus by various mechanical instruments and may additionally use chemical agents, host-modulating agents, or local and systemic antimicrobials as an adjunct. The second step is usually preceded by or delivery simultaneously with the first step in therapy, depending on the severity of the disease to prevent abscess formation. Subgingival instrumentation performed either by hand or ultrasonic instruments aim to alter the subgingival ecological environment by disrupting the dental biofilm and removing the hard deposits [29]. The first and second steps in therapy should be implemented for all periodontitis patients, emphasizing that non-surgical periodontal treatment must be completed before considering periodontal surgery as part of the third step of therapy [27].

Different approaches have been utilized for instrumentation, namely hand instruments, magneto-strictive ultrasonic scalers, and piezoelectric ultrasonic scalers. The advantages of hand instruments are due to their good tactile sensation and provide a smoother root surface after instrumentation [30]. The disadvantages of hand instruments are due to the 20-50% longer clinical time to match the similar clinical outcomes obtained by power scalers such as ultrasonic scalers. Furthermore, hand instruments may be considered an aggressive modality with a limited number of curette strokes before damaging the root cementum [31]. Hand instruments require sharpening every 5-20 stokes, which may not be practical for daily practice and could potentially damage the original contour of the instrument [32]. Magneto-strictive ultrasonic scalers operate by an elliptical movement with 18,000-45,000 cycles per second with amplitude of 10-100 microns. According to Krishna and De Stefano [30], linear vibratory movement with 25,000-50,000 cycles per second and amplitude of 12-72 microns were observed in Piezoelectric ultrasonic scalers. These ultrasonic instruments were showed to be less aggressive by removing less root surface and causing less soft tissue trauma compared to hand instruments [33]. Piezoelectric ultrasonic scalers also require less clinical time with a 37% reduction compared to hand instrumentation, thus reducing operator fatigue as well as being less dependent on the clinical skill of the operators [34]. The production of acoustic turbulence streaming, and cavitation promotes the enhancement of the disruption of the dental biofilm. In addition, slimline tip designs allow these devices to have an improved access in the furcation areas and deep vertical defects. The drawbacks of these ultrasonic instruments may be due to the rougher surfaces that may be created, as well as the production of a contaminated aerosol spray, and generation of pain/discomfort during treatment [35].

When comparing the clinical outcomes from using ultrasonic and hand instrumentation, it was evident from previous studies that both treatment modalities resulted in similar clinical and microbiological outcomes [36]. Furthermore, both modalities appeared to yield a similar degree of subgingival calculus removal and provided comparable healing responses. The major advantages of ultrasonic scalers are that they required less time as well as enhanced cleaning around the furcation areas and deeper pockets [37]. Wennström et al. [38] also showed that a higher efficiency as described with the number of minutes of instrumentation used to close one pocket was significantly higher in the ultrasonic groups compared to the hand instrumentation group. A more recent systematic review addressed the question on the efficacy of subgingival instrumentation compared with the different modalities. The systematic review only included randomized controlled trials with more than three months duration and observed no significant differences in terms of the clinical outcomes between sonic/ultrasonic and hand instrumentation [39]. It was also noted that a large heterogeneity was evident in terms of the instrument manufacturer, design, and technology employed across the different studies. In addition, clinicians often use both hand and power-drive instruments in their clinical practice.

The complete removal of dental calculus may be challenging and not straightforward. Several factors could affect the efficacy of calculus removal during instrumentation despite the different treatment modalities used. These factors are pocket depth, tooth type and surface, proper access, instruments designs, and operator experience. It was demonstrated from the observation of extracted teeth following subgingival scaling and root planning, that a deeper initial pocket depth resulted in more residual calculus [40]. Under scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of extracted teeth, it was also observed that the residual biofilm and calculus were detected primarily at the line angles, grooves, and depression of the root surfaces [41]. The detection of calculus after subgingival instrumentation had a high false-negative up to 77.4%, indicating difficulties in detecting the completeness of instrumentation [42]. Despite treated root surfaces that were judged as calculus-free after instrumentation under 3.5x magnification and assessed with a dental explorer. The remaining calculus was not uncommon and was shown as micro islands under a videoscope [43]. Dental calculus can bind directly to the hydroxyapatite structure of cementum in which its attachment is stronger than the cohesive strength that binds calculus together. Thus, a complete removal of calculus is difficult and residual micro islands often remain after instrumentation. Scaling and root planing with direct surgical access and with experienced operators was shown to be significant factors in achieving improved calculus removal in molars with furcation involvement. Caffesse et al. [44] demonstrated that periodontal flaps could provide better access for scaling and root planing resulting in an improved calculus free surface. Complete calculus removal in the furcation areas, however, was a rare outcome, possibly due to the tooth’s anatomical features and the conventional instruments used in that earlier study [45].

The Adjunctive Use of Systemic Antimicrobials in Non-surgical Periodontal Therapy

For the management of periodontitis, systemic antimicrobials can provide additional clinical benefits in specific cases. The main advantages of systemic antimicrobials are the ability to reach all oral surfaces and fluids, eliminating periodontal pathogen that invades the soft tissues. For instance, the eradication of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (A.a) was reported to be difficult because of its ability to invade the periodontium. Systemic antimicrobials can also reach inaccessible areas such as concavities, furcation areas [6]. This modality can be delivered in cause-related therapy (the second step of therapy), and after the optimal control of the supragingival biofilm has been achieved [27]. Previously, the use of adjunctive use of systemic antimicrobials in non-surgical periodontal treatment was recommended in severe periodontitis cases (PPD > 6 mm) or aggressive form of periodontitis [29]. Guerrero and co-workers demonstrated that the administration of systemic amoxicillin and metronidazole in non-surgical treatment could significantly improve the clinical outcomes (PPD reduction, CAL gain) in patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis [46]. Despite the notion that the adjunctive benefit of antimicrobial may be greater in an aggressive form of periodontitis [47,48], the recent evidence, however, does not support any differences of the antimicrobial effect between aggressive and chronic periodontitis [49]. It was demonstrated that the patients with A.a did not receive any additional benefits from the use of systemic antimicrobials.

According to Teughel et al. [49] the evidence was consistent in confirming that the adjunctive use of systemic antibiotics could improve the clinical outcomes of non-surgical periodontal therapy The combination use of amoxicillin and metronidazole provided the most significant outcome in PPD reduction, a higher percentage of pocket closure, and a higher reduction in bleeding on probing (BoP) [49,50]. The additional effect of the use of antibiotics for PPD reduction and CAL gain were approximately 0.5 mm and 0.3-0.4 mm, respectively. The adjunctive effect was shown to be more pronounced in initially deep pockets with additional benefits in terms of the percentage of pocket closure was 14.5% and 12% at 6 and 12 months, respectively [49]. However, due to the awareness of the emergence of specific-drug-resistant and multidrug-resistant bacterial species that could potentially lead to serious socio-economic and health problems, the use of antibiotics should be limited to those patients who would experience a clinically relevant difference [51,52]. The clinical guidelines recommend that the routine use of systemic antibiotics as an adjunct to subgingival debridement in patients with periodontitis is not recommended. However, the adjunctive use of specific antibiotics may be considered for specific patient categories (e.g., generalised periodontitis Grade C in healthy young adults with good oral hygiene and a documented high rate of progression) [27,53].

The Adjunctive Use of Subgingival Locally Delivered Antimicrobials (LDAs) in Non-surgical Periodontal Therapy

In cases of localised residual pockets, locally delivered antimicrobials (LDAs) may be an alternative adjunct to non-surgical periodontal therapy. It provided a high level and sustained release of the active agent in GCF, providing fewer side effects, limits the development of microbial antibiotic resistance, and was independent of patient compliance [8]. Clinical indications for the use of LDAs included the management of non-responding sites or disease recurrence during supportive periodontal care, residual periodontal pockets in the esthetic zone where surgery may compromise esthetics, pocket disinfection prior to regenerative periodontal surgery, and the control of periodontal disease among patients with relative or absolute contraindications for surgery [8,54]. The previous recommendations from the American Academy of Periodontology (AAP) in 2006 stated that the use of LDAs can be considered when localised recurrent and/or residual PPDs > 5 mm with inflammation is still present following conventional therapies [55]. Whereas in the presence of multiple sites with PPD >5 mm in the same quadrant, or the presence of anatomical defects (e.g., intrabony defects), additional surgical therapies may be considered. Despite the difficulty to define an evidence-based protocol, the recent S3 level clinical guidelines have indicated that this type of antimicrobial intervention may be considered as an adjunct to subgingival instrumentation in patients with periodontitis as part of the second step of therapy [27].

A recent systematic review reported that statistically significant clinical differences in the adjunctive use of LDAs when compared with subgingival debridement alone or plus a placebo, providing addition short term (6-9 months) effect of 0.365 mm and 0.263 mm for PPD reduction and CAL gain, respectively. Minor improvements in additional PPD reduction (0.19 mm) in long-term studies with no statistically significant difference for CAL were also reported [56]. The largest reported clinical benefits were observed in doxycycline or tetracycline-based products such as Atridox, Actisite, and Ligosan.

The Adjunctive Use of Antiseptics in Non-surgical Periodontal Therapy

Adjunctive chemotherapeutics or antiseptics may be considered in periodontal therapy as adjuncts to mechanical debridement to manage the level of gingival inflammation in specific cases [27,57]. This personalized treatment approach would facilitate in controlling gingival inflammation among patients who were unable to effectively remove the supragingival biofilm by mechanical procedures alone. The adjunctive use of antiseptics may also slightly improve the clinical outcome of subgingival instrumentation in terms of PPD reduction during non-surgical periodontal therapy and may also be considered during supportive periodontal care to control inflammation [27,58]. Mouth rinses containing chlorhexidine or essential oils were shown to be the most effective in controlling gingival inflammation and the dental biofilm [58]. Chlorhexidine, for example, is a cationic agent of the bisbiguanide class that could provide an antimicrobial and plaque inhibitory effect as well as maintaining high substantively [8]. Nevertheless, the medical status of the patient, patient preference, the level of dexterity, economical costs, local anatomical factors, and unwanted adverse effects such as staining, and taste alteration may also be considered somewhat negative and unwanted, compared to the potential benefits of these agents. Also, due to the ability of these chemical agents to reduce gingivitis, it is essential that an adequate biofilm control has been established prior to considering the adjunctive use of antiseptics. The absence of gingival bleeding, following the use of these agents, may mislead the patient into thinking that their periodontal problem has been resolved and as such they may fail to consider the seriousness of the underlying periodontal disease if further professional treatment is not re-established [59].

Air-polishing Applications in Non-surgical Periodontal Therapy

Air polishing was introduced as a professional tooth cleaning method as an alternative to rubber cup instrumentation [60]. This cleaning method generates a mixture of pressurized air and abrasive particles [61]. Several studies have confirmed its effectiveness in removing the dental biofilm and stain with less operator fatigue time-efficient management [62,63]. Air polishing offers more comfort and patient acceptance compared to subgingival instrumentation with hand instruments or ultrasonic scalers [64]. Different powders are used in air-polishing procedures, for example, sodium bicarbonate, glycine, erythritol, and bioactive glasses powders. Glycine was reported to be safe effective in biofilm removal when applying on both dentine and root cementum, unlike sodium bicarbonate [61,65]. Air polishing using glycine powder resulted in less patient discomfort compared to hand instrumentation [66], as well as being safer to use on the periodontal tissues [67]. Erythritol is also safe to be applied subgingivally and could achieve similar clinical outcomes in periodontal treatment compared to ultrasonic debridement [68]. The introduction of a subgingival nozzle design also offered a safer approach for effective subgingival biofilm removal [69]. In fact, between maintenance visits, the dental biofilm may be relatively immature and unmineralized, and as such is easily removed thereby avoiding any unnecessary aggressive instrumentation that damages the tooth surfaces [70]. Several clinical studies have reported that the application of air-polishing was more efficient in removing the dental biofilm without any unnecessary discomfort compared to conventional modalities [64,68,71]. Air-polishing also offers a promising benefit as an alternative, more conservative procedure, for debridement during supportive periodontal care (SPC) a part of a professional mechanical plaque removal (PMPR) intervention [27]. Also, a recent clinical trial demonstrated that the adjunctive use of erythritol air-polishing in combination with a full-mouth disinfection protocol could result in greater pocket depth reduction in moderate and deep pockets and a higher percentage of pocket closure over 6 months when compared to conventional protocol [72].

Photodynamic Therapy in Non-surgical Periodontal Therapy

Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) is an adjunctive treatment modality in non-surgical periodontal therapy [7,73]. The combined use of a low-level light and a photosensitizer leads to the production of singlet oxygen energy and free radicals which are cytotoxic to microorganisms [74]. A local effect of this treatment is due to the inability of the generated cytotoxic oxygen species to migrate more than 0.02 μm [75]. This application aimed to reduce both the bacterial load and periodontal pathogens in the periodontal pockets [73]. A previously published systematic review reported on the limited clinical value of this treatment modality as either an independent or adjunctive treatment [76]. The clinical benefits were also shown to be minimal and provided only short-term benefits [77]. Despite some reported improvement in the published clinical studies, this treatment was shown to be inferior, compared to the use of systemic antibiotics [73,78]. The existing limited evidence also showed considerable heterogeneity among studies; therefore, no strong clinical recommendations could be recommended [77]. Furthermore, no conclusive evidence on the effect in reducing bacteria load and the level of inflammation could be drawn [74]. A recent systematic review confirmed that the adjunctive use of aPDT failed to achieve a statistically significant periodontal improvement in terms of PPD reduction [79]. Therefore, the recent guidelines would suggest that adjunctive aPDT should not be used for the treatment of patients with periodontitis [27].

Re-evaluation after Non-surgical Periodontal Therapy

After the recommended two steps of treatment, the periodontal condition should be allowed to heal sufficiently prior to any clinical re-evaluation. However, this evaluation should not be delayed too long since the subgingival microbial recolonization by pathogenic bacteria may occur [80]. Six to eight weeks after initial therapy has been suggested before reevaluating the periodontal condition following periodontal treatment [81,82]. This re-evaluation will be mainly assessing sites presenting with PPD >4 mm with BOP or having deep pockets (PPD >6 mm), which indicates that the endpoints of the therapy have not yet been achieved [83]. Patients who have not responded well from the initial stages will receive further treatment as part of the third step of therapy aiming to treat those non-responding sites. The treatment options at this point can be varied, ranging from repeated subgingival instrumentation with or without adjunctive therapies, access flap surgery, resective surgery, or regenerative surgery.

Wennström et al. [38] demonstrated that the percentage of closed pockets at three months after an initial round of subgingival instrumentation was 58-66%. Multilevel analysis indicated that the factors associated with an inferior outcome following non-surgical periodontal treatment was as follows: smoking, the presence of plaque at the tooth site, molars, and the initial pocket. In other words, smokers with deep pockets and the presence of plaque in molars sites were expected to have the poorest treatment response [84]. The evaluation of the efficacy of subgingival instrumentation has been shown to be an efficacious treatment in the reduction of gingival inflammation, probing pocket depth (PPD), and a number of disease sites [39]. The overall proportion of closed pockets (PD< 4 mm and absence of BOP), which is a relevant clinical outcome, was 74% at 6-8 months. Furthermore, a mean reduction of PPD 1.7 mm at 6-8 months and a greater PPD reduction of 2.6 mm in deep sites (> 6 mm) was observed. In terms of the reduction in gingival inflammation, a mean reduction of 62.7% in BOP scores was also observed. The findings from this systematic review indicated that subgingival instrumentation should be considered a key part of periodontal surgery to achieve infection control as it may also limit the need for additional therapy, which can be more expensive and cause further patient morbidity. The recent systematic review by Citterio et al. [85] also confirmed that non-surgical periodontal treatment was effective in reducing the number of periodontal pockets (between one-half and two-thirds of the depth of the pocket).

Adverse Effects following Non-surgical Periodontal Therapy

Non-surgical periodontal treatment often leads to significant clinical improvement and has remained the cornerstone in periodontal therapy [7]. Nevertheless, this treatment could potentially damage the periodontium as well. There are several adverse effects following non-surgical and surgical procedures that the clinician should be aware of. For example, sensitivity to hot and cold stimuli (dentine/root sensitivity), gingival trauma, inflammation (oedema, bleeding), infection (gingival or periapical abscess) following non-surgical procedures.

Pain and discomfort during regular scaling or instrumentation with an ultrasonic scaler may be an unpleasant experience that may deter a patient from attending for periodontal treatment [86]. Pain could be elicited by frictional forces and heat which are generated during treatment, as well as dentine hypersensitivity that is induced by cold irrigation from an ultrasonic scaler. The degree of post-operative discomfort may also be due to several factors such as 1) the length and complexity of the procedure, 2) poor tissue handling, 3) poor infection control and 4) experience and expertise of the operator [86,87]. Post-operative pain may also increase in intensity during the first few days following the procedure and then diminishes during the first week.

Dentine Hypersensitivity (Root Sensitivity)

The definition for dentine hypersensitivity (DH) is a “short, sharp pain arising from exposed dentin in response to stimuli typically thermal, evaporative, tactile, osmotic or chemical and which cannot be ascribed to any other form of dental defect or disease” [87]. The term root sensitivity is used to describe sensitivity associated with periodontal disease and therapy. It is estimated to occur in almost 50% of patients following periodontal treatment, and the intensity increases during the first week or so and then diminishes [88]. Dentine hypersensitivity after periodontal treatment has been showed to be transient in nature with associated mild to moderate pain [89]. Von Troil et al. [90] performed a systematic review to assess the prevalence of dentine hypersensitivity following periodontal therapy and reported that this condition occurred in approximately half of the patients following periodontal treatment. This high prevalence could be explained by the fact that instrumentation with various types of instruments led to cementum removal and loss of root structure, therefore increasing dentine permeability and sensitivity. This emphasizes that the patient should be informed of the potential risk of this complication following non-surgical periodontal treatment as the treatment may impact on the patient’s quality of life (QoL). A recent clinical study suggested that the use of warmed water (36°C) as an irrigation in conjunction with a piezoelectric scaler, which has its own reservoir of water, could reduce the pain perception during instrumentation and improve patient acceptance of the procedure [91]. Pristine plaque control following periodontal treatment was also suggested to help alleviate dentine hypersensitivity. This is possibly due to the promotion of mineral depositions around the dentinal tubules when root surfaces are kept free of a dental biofilm [92]. Moreover, all surgical procedures, particularly flap surgeries with osseous resection, have been shown to produce more dentine hypersensitivity than non-surgical periodontal therapy [93].

The management of dentine hypersensitivity is, therefore, to eliminate any predisposing factor that causes exposure of dentine and the opening of dentinal tubules [94]. Two main treatment approaches based on the hydrodynamic theory are tubule occlusion and nerve blocking by means of ionic diffusion. These agents can be classified according to their mode of action into a) over the counter (OTC) or b) In-office products. However, the existing evidence suggests that no desensitizing agent has been the ideal product for relieving the symptoms from dentine hypersensitivity [95]. Furthermore, the choices of professional, home use treatment, or the combination of both are mainly arbitrary depending on the practitioner’s understanding and experience of the problem [96]. Fluoride varnishes and gels, glutaraldehyde/2-hydroexethylmethacrylate (HEMA), potassium nitrates, and bonding agents are most often used to treat dentine hypersensitivity among dentists (97). Systematic reviews and meta-analysis suggest that there is sufficient evidence to support the use of potassium-, stannous fluoride-, potassium and stannous fluoride-, calcium sodium phospho-silicate-, and arginine-containing desensitizing toothpaste. Strontium-containing desensitizing toothpastes, however, were reported to have no statistically significant desensitizing effect [97,98].

Gingival Recession

Gingival recession is commonly observed among patients with a high standard of oral hygiene with overzealous toothbrushing but also identified in patients with poor oral hygiene [99]. Buccal gingival recession, especially in teeth or roots with a prominent position in the jaw, occurs frequently in those of high standard of oral hygiene and the severity tends to increase with age [100]. Once the root surface is left exposed to the oral cavity, the cementum can be lost and subsequently result in root sensitivity and root caries [96]. Incorrect tooth brushing methods, particularly excessive pressure while brushing, combined with a highly abrasive toothpaste can further contribute to the progression of the condition [101]. Patients should be informed that a good brushing technique rather than using an excessive force is crucial for good plaque control [94]. Several investigators have indicated that using a surgical root coverage procedure for patients complaining of dentine hypersensitivity showed a mean reduction of dentine hypersensitivity of 77.83%, following the procedure, however recent systematic review concluded that there was insufficient evidence to suggest that this surgical procedure predictably reduced dentine hypersensitivity [102]. Gingival recession together with a missing cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) due to tooth wear may also be observed. CEJ reconstruction can be performed using a resin composite prior to a surgical root coverage procedure with the aim of increasing the intimate contact and stability of the flap/graft as well as improving the final gingival margin contour which in turn may reduce dentine hypersensitivity by covering the previously exposed root surface [103,104].

Conclusions

Periodontitis is a multifactorial inflammatory disease affecting susceptible individuals. There has however been a fundamental shift in philosophy in the management of the condition due to an improvement in our understanding of the role and function of the oral flora indicating that the dysbiosis of the commensal microorganisms rather than any acquisition of exogenous pathogens are key in the development of any future disease progression. The control of the dental biofilm is therefore considered to be an important treatment strategy to halt the progression thereby achieving periodontal stability. Non-surgical and surgical periodontal debridement procedures together with self-performed biofilm control, therefore, is a prerequisite for managing inflammation and restoring periodontal health. Adjunctive treatment modalities as indicated in this overview may also be of benefit when incorporated into the management of the condition.

References

- Papapanou PN, Sanz M, Buduneli N, Dietrich T, Feres M, et al. (2018) Periodontitis: Consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri‐Implant Diseases and Conditions. Journal of Periodontology. 89: 173-182. [crossref]

- Bartold PM, Van Dyke TE (2013) Periodontitis: a host‐mediated disruption of microbial homeostasis. Unlearning learned concepts. Periodontology 2000 62: 203-217. [crossref]

- Cekici A, Kantarci A, Hasturk H, Van Dyke TE (2014) Inflammatory and immune pathways in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. Periodontology 2000 64: 57-80. [crossref]

- Fine DH, Patil AG, Loos BG (2018) Classification and diagnosis of aggressive periodontitis. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 45: 95-111. [crossref]

- Kassebaum N, Bernabé E, Dahiya M, Bhandari B, Murray C, et al. (2014) Global burden of severe periodontitis in 1990-2010: a systematic review and meta-regression. Journal of Dental Research 93: 1045-1053. [crossref]

- Graziani F, Karapetsa D, Alonso B, Herrera D (2017) Nonsurgical and surgical treatment of periodontitis: how many options for one disease? Periodontology 2000 75: 152-188. [crossref]

- Lang NP, Salvi GE, Sculean A (2019) Nonsurgical therapy for teeth and implants-When and why? Periodontol 2000 79: 15-21. [crossref]

- Berglundh T, Giannobile WV, Sanz M, Lang NP (2021) Lindhe’s Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry: John Wiley & Sons.

- Tonetti MS, Greenwell H, Kornman KS (2018) Staging and grading of periodontitis: Framework and proposal of a new classification and case definition. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 45: 149-S61. [crossref]

- Caton JG, Armitage G, Berglundh T, Chapple IL, Jepsen S, Kornman KS, et al. (2018) A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri‐implant diseases and conditions–Introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification. Wiley Online Library 48: 1-8. [crossref]

- Marsh PD, Devine DA (2011) How is the development of dental biofilms influenced by the host? Journal of Clinical Periodontology 38: 28-35. [crossref]

- Curtis MA, Diaz PI, Van Dyke TE (2020) The role of the microbiota in periodontal disease. Periodontology 2000 83: 14-25. [crossref]

- Hajishengallis G, Darveau RP, Curtis MA (2012) The keystone-pathogen hypothesis. Nature Reviews Microbiology 10: 717-725. [crossref]

- Hajishengallis G (2014) Immunomicrobial pathogenesis of periodontitis: keystones, pathobionts, and host response. Trends in Immunology 35: 3-11. [crossref]

- Hajishengallis G, Lamont RJ (2012) Beyond the red complex and into more complexity: the polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis (PSD) model of periodontal disease etiology. Molecular Oral Microbiology 27: 409-419. [crossref]

- Roberts-Harry E, Clerehugh V (2000) Subgingival calculus: where are we now? A comparative review. Journal of Dentistry. 28: 93-102. [crossref]

- Allen DL, Kerr DA (1965) Tissue response in the guinea pig to sterile and non‐sterile calculus. The Journal of Periodontology 36: 121-126. [crossref]

- Listgarten M, Ellegaard B (1973) Electron microscopic evidence of a cellular attachment between junctional epithelium and dental calculus. Journal of Periodontal Research 8: 143-150. [crossref]

- Jepsen S, Deschner J, Braun A, Schwarz F, Eberhard J (2011) Calculus removal and the prevention of its formation. Periodontology 2000. 55: 167-88. [crossref]

- Schroeder H (1963) Inorganic content and histology of early dental calculus in man. Helv Odont Acta 7: 17-30.

- Wilson Jr TG, Carnio J, Schenk R, Myers G (2008) Absence of histologic signs of chronic inflammation following closed subgingival scaling and root planing using the dental endoscope: Human biopsies–A pilot study. Journal of Periodontology 79: 2036-2041. [crossref]

- Fujikawa K, O’Leary TJ, Kafrawy AH (1988) The effect of retained subgingival calculus on healing after flap surgery. Journal of Periodontology 59: 170-175. [crossref]

- Mombelli A, Nyman S, Brägger U, Wennström J, Lang NP (1995) Clinical and microbiological changes associated with an altered subgingival environment induced by periodontal pocket reduction. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 22: 780-7. [crossref]

- Pihlstrom BL, McHuon RB, Oliphant TH, Ortiz‐Campos C (1983) Comparison of surgical and nonsurgical treatment of periodontal disease A review of current studies and additional results after 6 1/2 years. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 10: 524-541. [crossref]

- Morrison E, Ramfjord S, Hill R (1980) Short‐term effects of initial, nonsurgical periodontal treatment (hygienic phase). Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 7: 199-211. [crossref]

- Lindhe J, Socransky S, Nyman S, Haffajee A, Westfelt E (1982) “Critical probing depths” in periodontal therapy. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 9: 323-336. [crossref]

- Sanz M, Herrera D, Kebschull M, Chapple I, Jepsen S, Beglundh T, et al. (2020) Treatment of Stage I‐III Periodontitis–The EFP S3 Level Clinical Practice Guideline. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 47: 4-60. [crossref]

- Preshaw P, Heasman L, Stacey F, Steen N, McCracken G, Heasman P (2005) The effect of quitting smoking on chronic periodontitis. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 32: 869-789. [crossref]

- Heitz‐Mayfield LJ, Lang NP (2013) Surgical and nonsurgical periodontal therapy. Learned and unlearned concepts. Periodontology 2000 62: 218-231. [crossref]

- Krishna R, De Stefano JA (2016) Ultrasonic vs. hand instrumentation in periodontal therapy: clinical outcomes. Periodontology 2000. 71:113-127. [crossref]

- Coldiron NB, Yukna RA, Weir J, Caudill RF (1990) A quantitative study of cementum removal with hand curettes. Journal of Periodontology. 61: 293-299. [crossref]

- Zappa U, Smith B, Simona C, Graf H, Case D, Kim W (1991) Root substance removal by scaling and root planing. Journal of Periodontology 62: 750-754. [crossref]

- Tunkel J, Heinecke A, Flemmig TF (2002) A systematic review of efficacy of machine‐driven and manual subgingival debridement in the treatment of chronic periodontitis. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 29: 72-81. [crossref]

- Cobb CM (1996) Non‐surgical pocket therapy: Mechanical. Annals of Periodontology 1: 443-490. [crossref]

- Cobb CM (2002) Clinical significance of non‐surgical periodontal therapy: an evidence‐based perspective of scaling and root planing. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 29: 22-32. [crossref]

- Badersten A, Nilveus R, Egelberg J (1984) Effect of nonsurgical periodontal therapy: II. Severely advanced periodontitis. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 11: 63-76. [crossref]

- Claffey N, Polyzois I, Ziaka P (2004) An overview of nonsurgical and surgical therapy. Periodontology 2000. 36: 35-44. [crossref]

- Wennström JL, Tomasi C, Bertelle A, Dellasega E (2005) Full‐mouth ultrasonic debridement versus quadrant scaling and root planing as an initial approach in the treatment of chronic periodontitis. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 32: 851-859. [crossref]

- Suvan J, Leira Y, Moreno Sancho FM, Graziani F, Derks J, Tomasi C (2020) Subgingival instrumentation for treatment of periodontitis. A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 47: 155-175. [crossref]

- Rabbani GM, Ash MM, Caffesse RG (1981) The effectiveness of subgingival scaling and root planing in calculus removal. Journal of Periodontology. 52: 119-123. [crossref]

- Rateitschak‐Plüss EM, Schwarz JP, Guggenheim R, Duggelin M, Rateitschak KH (1992) Non‐surgical periodontal treatment: Where are the limits? An SEM study. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 19: 240-244. [crossref]

- Sherman P, Hutchens Jr L, Jewson L, Moriarty J, Greco G, McFall Jr W (1990) The effectiveness of subgingival scaling and root planing I. Clinical detection of residual calculus. Journal of Periodontology 61: 3-8. [crossref]

- Harrel SK, Wilson Jr TG, Tunnell JC, Stenberg WV (2020) Laser identification of residual microislands of calculus and their removal with chelation. Journal of Periodontology 91: 1562-1568. [crossref]

- Caffesse RG, Sweeney PL, Smith B (1986) Scaling and root planing with and without periodontal flap surgery. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 13: 205-210. [crossref]

- Fleischer HC, Mellonig JT, Brayer WK, Gray JL, Barnett JD (1989) Scaling and root planing efficacy in multirooted teeth. Journal of Periodontology 60: 402-409. [crossref]

- Guerrero A, Griffiths GS, Nibali L, Suvan J, Moles DR, Laurell L, et al. (2005) Adjunctive benefits of systemic amoxicillin and metronidazole in non‐surgical treatment of generalized aggressive periodontitis: a randomized placebo‐controlled clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 32: 1096-107. [crossref]

- Herrera D, Sanz M, Jepsen S, Needleman I, Roldán S (2002) A systematic review on the effect of systemic antimicrobials as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in periodontitis patients. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 29: 136-159. [crossref]

- Haffajee AD, Socransky SS, Gunsolley JC (2003) Systemic anti‐infective periodontal therapy. A systematic review. Annals of Periodontology 8: 115-181. [crossref]

- Teughels W, Feres M, Oud V, Martín C, Matesanz P, Herrera D (2020) Adjunctive effect of systemic antimicrobials in periodontitis therapy. A systematic review and meta‐ Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 47: 251-281. [crossref]

- Sgolastra F, Petrucci A, Gatto R, Monaco A (2012) Effectiveness of systemic amoxicillin/metronidazole as an adjunctive therapy to full‐mouth scaling and root planing in the treatment of aggressive periodontitis: A systematic review and meta‐ Journal of Periodontology 83: 731-743. [crossref]

- Elias C, Moja L, Mertz D, Loeb M, Forte G, Magrini N (2017) Guideline recommendations and antimicrobial resistance: the need for a change. BMJ open 7: 016264. [crossref]

- Mombelli A, Cionca N, Almaghlouth A (2011) Does adjunctive antimicrobial therapy reduce the perceived need for periodontal surgery? Periodontology 2000 55: 205-216. [crossref]

- Kebschull M, Chapple I (2020) Evidence-based, personalised and minimally invasive treatment for periodontitis patients-the new EFP S3-level clinical treatment guidelines. British Dental Journal 229: 443-449. [crossref]

- Tomasi C, Koutouzis T, Wennström JL (2008) Locally delivered doxycycline as an adjunct to mechanical debridement at retreatment of periodontal pockets. Journal of Periodontology 79: 431-439. [crossref]

- Periodontology AAo (2006) American Academy of Periodontology statement on local delivery of sustained or controlled release antimicrobials as adjunctive therapy in the treatment of periodontitis. J Periodontol 77: 1458. [crossref]

- Herrera D, Matesanz P, Martín C, Oud V, Feres M, Teughels W (2020) Adjunctive effect of locally delivered antimicrobials in periodontitis therapy: A systematic review and meta‐ Journal of Clinical Periodontology 47: 239-256. [crossref]

- Chapple IL, Van der Weijden F, Doerfer C, Herrera D, Shapira L, Polak D, et al. (2015) Primary prevention of periodontitis: managing gingivitis. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 42: 71-76. [crossref]

- Figuero E, Herrera D, Tobías A, Serrano J, Roldan S, Escribano M, et al. (2019) Efficacy of adjunctive anti‐plaque chemical agents in managing gingivitis: A systematic review and network meta‐ Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 46: 723-739. [crossref]

- Tonetti MS, Jepsen S, Jin L, Otomo‐Corgel J (2017) Impact of the global burden of periodontal diseases on health, nutrition and wellbeing of mankind: A call for global action. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 44: 456-462. [crossref]

- Willmann DE, Norling BK, Johnson WN (1980) A new prophylaxis instrument: effect on enamel alterations. The Journal of the American Dental Association 101: 923-925. [crossref]

- Petersilka GJ, Bell M, Mehl A, Hickel R, Flemmig TF (2003) Root defects following air polishing: An in vitro study on the effects of working parameters. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 30: 165-70. [crossref]

- Graumann SJ, Sensat ML, Stoltenberg JL (2013) Air polishing: a review of current literature. American Dental Hygienists’ Association. 87: 173-180. [crossref]

- Cobb CM, Daubert DM, Davis K, Deming J, Flemmig T, Pattison A, et al. (2017) Consensus conference findings on supragingival and subgingival air polishing. Compend Contin Educ Dent 38: 1-4. [crossref]

- Moene R, Decaillet F, Andersen E, Mombelli A (2010) Subgingival plaque removal using a new air-polishing device. J Periodontol 81: 79-88. [crossref]

- Petersilka GJ, Bell M, Häberlein I, Mehl A, Hickel R, Flemmig TF (2003) In vitro evaluation of novel low abrasive air polishing powders. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 30: 9-13. [crossref]

- Petersilka GJ, Steinmann D, Haberlein I, Heinecke A, Flemmig TF (2003) Subgingival plaque removal in buccal and lingual sites using a novel low abrasive air-polishing powder. J Clin Periodontol 30: 328-333. [crossref]

- Buhler J, Amato M, Weiger R, Walter C (2016) A systematic review on the effects of air polishing devices on oral tissues. Int J Dent Hyg. 14: 15-28. [crossref]

- Muller N, Moene R, Cancela JA, Mombelli A (2014) Subgingival air-polishing with erythritol during periodontal maintenance: randomized clinical trial of twelve months. J Clin Periodontol 41: 883-889. [crossref]

- Flemmig TF, Arushanov D, Daubert D, Rothen M, Mueller G, Leroux BG. Randomized controlled trial assessing efficacy and safety of glycine powder air polishing in moderate-to-deep periodontal pockets. J Periodontol. 2012;83(4):444-452. [crossref]

- Mombelli A (2019) Maintenance therapy for teeth and implants. Periodontol 2000 79: 190-199. [crossref]

- Wennstrom JL, Dahlen G, Ramberg P (2011) Subgingival debridement of periodontal pockets by air polishing in comparison with ultrasonic instrumentation during maintenance therapy. J Clin Periodontol 38: 820-827. [crossref]

- Stein JM, Yekta‐Michael SS, Schittenhelm F, Reichert S, Kupietz D, Dommisch H, et al. (2021) Comparison of three full‐mouth concepts for the non‐surgical treatment of stage III and IV periodontitis: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 48: 1516-1527. [crossref]

- Sculean A, Aoki A, Romanos G, Schwarz F, Miron RJ, Cosgarea R (2015) Is photodynamic therapy an effective treatment for periodontal and peri-implant infections? Dental Clinics 59: 831-858. [crossref]

- Cobb CM (2017) Lasers and the treatment of periodontitis: the essence and the noise. Periodontology 2000.;75(1):205-295. [crossref]

- Moan J, Berg K (1991) The photodegradation of porphyrins in cells can be used to estimate the lifetime of singlet oxygen. Photochemistry and photobiology. 53: 549-53. [crossref]

- Azarpazhooh A, Shah PS, Tenenbaum HC, Goldberg MB (2010) The effect of photodynamic therapy for periodontitis: A systematic review and meta‐ Journal of Periodontology 81: 4-14. [crossref]

- Sgolastra F, Petrucci A, Severino M, Graziani F, Gatto R, Monaco A (2013) Adjunctive photodynamic therapy to non‐surgical treatment of chronic periodontitis: a systematic review and meta‐ Journal of Clinical Periodontology 40: 514-526. [crossref]

- Arweiler NB, Pietruska M, Pietruski J, Skurska A, Dolińska E, Heumann C, et al. (2014) Six-month results following treatment of aggressive periodontitis with antimicrobial photodynamic therapy or amoxicillin and metronidazole. Clinical oral investigations 18: 2129-2135. [crossref]

- Salvi GE, Stähli A, Schmidt JC, Ramseier CA, Sculean A, Walter C (2020) Adjunctive laser or antimicrobial photodynamic therapy to non‐surgical mechanical instrumentation in patients with untreated periodontitis: A systematic review and meta‐ Journal of Clinical Periodontology 47: 176-198. [crossref]

- Magnusson I, Lindhe J, Yoneyama T, Liljenberg B (1984) Recolonization of a subgingival microbiota following scaling in deep pockets. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 11(3): 193-207. [crossref]

- Cobb CM, Sottosanti JS (2021) A re‐evaluation of scaling and root planing. Journal of Periodontology 92: 1370-1378. [crossref]

- Segelnick SL, Weinberg MA (2006) Reevaluation of initial therapy: when is the appropriate time? Journal of Periodontology 77: 1598-601. [crossref]

- Loos BG, Needleman I (2020) Endpoints of active periodontal therapy. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 47: 61-71. [crossref]

- Tomasi C, Leyland AH, Wennström JL (2007) Factors influencing the outcome of non‐surgical periodontal treatment: a multilevel approach. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 34: 682-690. [crossref]

- Citterio F, Gualini G, Chang M, Piccoli GM, Giraudi M, Manavella V, et al. (2022) Pocket closure and residual pockets after non‐surgical periodontal therapy: A systematic review and meta‐ Journal of Clinical Periodontology.;49(1): 2-14. [crossref]

- Matthews DC, McCulloch CA (1993) Evaluating patient perceptions as short‐term outcomes of periodontal treatment: A comparison of surgical and non‐surgical therapy. Journal of Periodontology 64: 990-997. [crossref]

- Canadian Advisory Board on Dentin H (2003) Consensus-based recommendations for the diagnosis and management of dentin hypersensitivity. J Can Dent Assoc 69: 221-226. [crossref]

- Sanz M, Addy M (2002) Group D summary. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 29: 195-196.

- Lin Y, Gillam D (2012) The prevalence of root sensitivity following periodontal therapy: a systematic review. International Journal of Dentistry 2012.

- Von Troil B, Needleman I, Sanz M (2002) A systematic review of the prevalence of root sensitivity following periodontal therapy. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 29: 173-177. [crossref]

- Daly S, Newcombe RG, Claydon NC, Seong J, Davies M, West NX (2020) A randomised controlled trial to determine patient experience of a magnetostrictive stack scaler as compared to a piezoelectric scaler, in supportive periodontal therapy. Journal of Dentistry. 93: 103279. [crossref]

- Tammaro S, Wennström JL, Bergenholtz G (2000) Root‐dentin sensitivity following non‐surgical periodontal treatment. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 27: 690-697. [crossref]

- Canakci CF, Canakci V (2007) Pain experienced by patients undergoing different periodontal therapies. The Journal of the American Dental Association. 138: 1563-1573. [crossref]

- Gillam DG, Chesters RK, Attrill DC, Brunton P, Slater M, Strand P, et al. (2013) Dentine hypersensitivity–guidelines for the management of a common oral health problem. Dental update 40: 514-524. [crossref]

- Gillam D, Orchardson R (2006) Advances in the treatment of root dentine sensitivity: mechanisms and treatment principles. Endodontic Topics. 13: 13-33.

- Dababneh R, Khouri A, Addy M (1999) Dentine hypersensitivity—An enigma? A review of terminology, mechanisms, aetiology and management. British Dental Journal 187: 606-611. [crossref]

- Cunha-Cruz J, Wataha JC, Zhou L, Manning W, Trantow M, Bettendorf MM, et al. (2010) Treating dentin hypersensitivity. The Journal of the American Dental Association. 141: 1097-1105.

- Bae JH, Kim YK, Myung SK (2015) Desensitizing toothpaste versus placebo for dentin hypersensitivity: a systematic review and meta‐ Journal of Clinical Periodontology 42: 131-141. [crossref]

- Löe H, Ånerud Å, Boysen H. (1992) The natural history of periodontal disease in man: prevalence, severity, and extent of gingival recession. Journal of Periodontology 63: 489-95. [crossref]

- Serino G, Wennström JL, Lindhe J, Eneroth L (1994) The prevalence and distribution of gingival recession in subjects with a high standard of oral hygiene. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 21: 57-63. [crossref]

- West NX. (2008) Dentine hypersensitivity: preventive and therapeutic approaches to treatment. Periodontology 2000. 48: 31-41. [crossref]

- Douglas de Oliveira DW, Oliveira‐Ferreira F, Flecha OD, Gonçalves PF (2013) Is surgical root coverage effective for the treatment of cervical dentin hypersensitivity? A systematic review. Journal of Periodontology. 84: 295-306. [crossref]

- Santamaria MP, Silveira CA, Mathias IF, Neves FLdS, Dos Santos LM, Jardini MAN, et al. (2018) Treatment of single maxillary gingival recession associated with non‐carious cervical lesion: Randomized clinical trial comparing connective tissue graft alone to graft plus partial restoration. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 45: 968-976.

- Zucchelli G, Gori G, Mele M, Stefanini M, Mazzotti C, Marzadori M, et al. (2011) Non‐carious cervical lesions associated with gingival recessions: A decision‐making process. Journal of Periodontology 82: 1713-1724. [crossref]

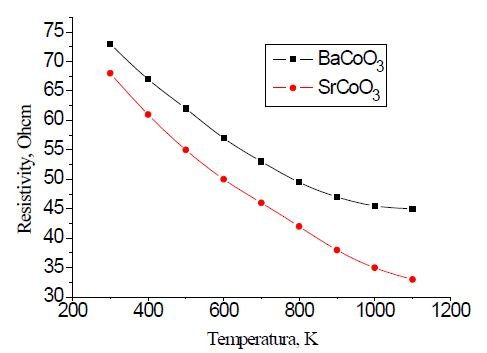

, where σ = 5.67 × 10-8 W/m2K is the Stefan Boltzmann constant, corresponded to the temperature of the heated body 1900°C. At this temperature, the sample melted. Melt droplets fell into water and cooled at a rate of 103 deg/s. Such cooling conditions made it possible to fix the high-temperature structural states of the material.

, where σ = 5.67 × 10-8 W/m2K is the Stefan Boltzmann constant, corresponded to the temperature of the heated body 1900°C. At this temperature, the sample melted. Melt droplets fell into water and cooled at a rate of 103 deg/s. Such cooling conditions made it possible to fix the high-temperature structural states of the material.