Abstract

Even though French sociology has long been interested in Alzheimer’s disease, most studies have been carried out “for” or “in support of” disease treatment, with the aim of analyzing the impact of the disease on the life of patients. This article offers some elements for the sociological study “of” Alzheimer’s disease. Based on a literature analysis centered on the information file on Alzheimer’s disease published by INSERM and on scientific articles and communications addressing the etiology of the disease, this paper aims to show how the entity “Alzheimer’s disease” is constructed today. After examining the way the figures on the disease have been produced, it will show how the etiology is constituted by advances in “diagnostic techniques” and research protocols.

Keywords

Sociologie, Alzheimer, Étiologie, Sociology, Alzheimer, Etiology

Introduction

It is now nearly 30 years since the first studies on Alzheimer’s disease referring to sociology or drawing from its methods were published. Apart from the work of [1], these first articles were often written by doctors working in the field of gerontology and public health [2,3], using methodologies (i.e. focus groups) derived from the social sciences. They focused, among other things, on the way in which the disease impacts the patient’s life course and his/her social network and the way in which he/she learns to cope with the illness. In France, the first sociological publications dealing specifically with Alzheimer’s disease date from the early 2000s [4,5]. After the disease was placed on the political agenda following the 2001 Girard report [6] and with incentives being given to conduct multi- or even inter-disciplinary research, numerous research projects have developed in sociology on the “big issues” model, reflecting the influence of the Anglo-Saxon model on the world of French research.

To obtain funding, sociologists have thus been invited to submit proposals to calls from large associations such as Médéric Alzheimer or France Alzheimer or from public funders such as the Caisse Nationale de Solidarité à l’Autonomie (CNSA – National Solidarity Fund for Autonomy) and the Fondation de Coopération Scientifique pour le plan Alzheimer (Foundation for Scientific Cooperation for the Alzheimer Plan). They have also taken part in programmes led by biomedical science or clinical research laboratories. Patient associations have been largely instrumental in ensuring that research should not confine itself to providing medical answers but should also answer the specific social needs of patients. The third (2004-2007) and fourth (2008-2012) Alzheimer Plan resulted in calls for even more inter-disciplinary research.

In such context, French sociological research has mostly been working “for” or “in support” of disease treatment, rather than dealing with the sociological study “of” the disease : while sociological work “in support” of Alzheimer’s disease treatment mainly aims to shed light on the experience of the patient (which is often little understood by medical professionals), sociology “of” the disease needs to examine the historical, social and scientific construction of what is called Alzheimer’s disease. Despite their theoretical and methodological differences, the former studies shared the common objective of furthering understanding of the disease. They have challenged strictly medical interpretations by showing, among other things, the way in which social context and social status (gender, age, family or professional status) have an impact on the announcement and reception of diagnosis and on adherence to treatment, and, more broadly, on the strategies devised by patients and their relatives to cope with their conditions. They have also shed light on the experience of caretakers and patients which had hitherto been overlooked areas of study [7]. This type of sociological work could also be described as sociological studies of sickness or illness, with “sickness” referring to the social role of sick people as defined by their relatives and professional colleagues and “illness” to the subjective experience of patients.

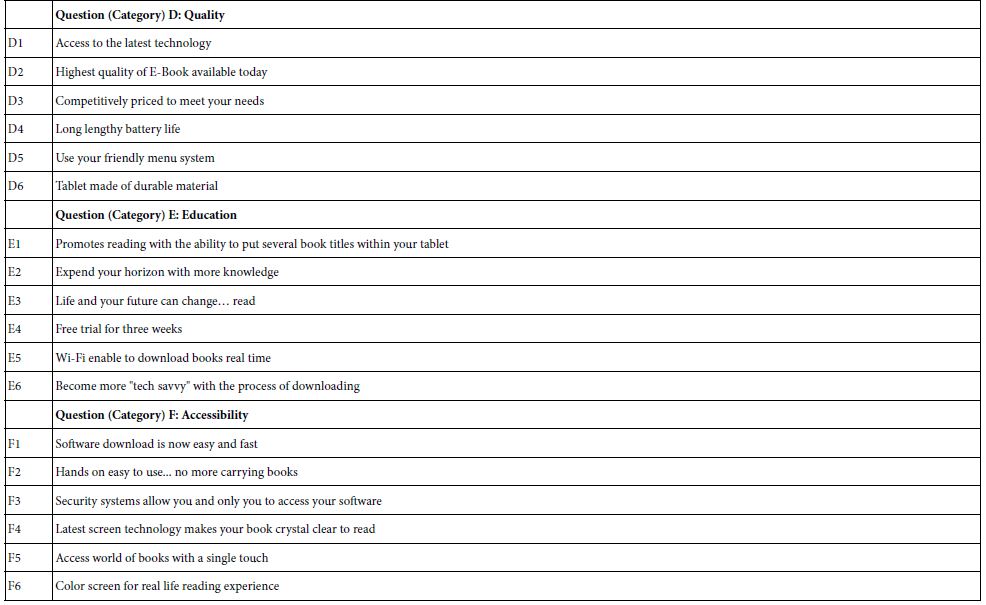

This paper, on the other hand, undertakes a sociological analysis of Alzheimer’s disease in the sense that it aims to question the way “Alzheimer’s disease” – a disease with biological and/or clinical specificities – has been constituted. Its approach is inspired by the sociology of science approach taken by [8] and Lock [9]. Based on the idea that “the facts of science are made, constructed, modeled and refined to produce data and a stable meaning” [8] p. 182) and that the sociologist’s role is to describe and decode them (Pestre, Ibid), I wish here to examine a few elements related to the etiology of the disease. In order to do so, I use the information file on Alzheimer’s disease published by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM- National Institute of Health and Medical Research). This file synthetizes the scientific knowledge on the disease and is mainly, though not exclusively, based on French research. As it is produced by the leading health research centre in France and signed by prominent French specialists in the field, it qualifies as scientific authority [10]. The aim of this paper is to examine the information presented in this report using scientific publications and presentations and show what data and hypotheses it rests on. I will first take a look at the figures (the prevalence) of the disease and the links with age. This will shed light on the way the figures have been “constructed” and suggest the way age has been used as one of the “explanatory” factors of the disease. Then I will discuss the issues raised, among other things, by advances in “diagnostic techniques” as to the etiology of the disease. Finally, I will suggest that some of the methodological limitations in the clinical investigation of sporadic forms result in the development of scientific protocols that ultimately reinforce the idea of biological and genetic causality.

Age and the Number of Patients

Age is very often used in the literature on Alzheimer’s disease to account for the prevalence of the disease among different age groups as well as to generate hypotheses as to its etiology.

Estimated Prevalence of the Disease by Age

After a short introduction, the section “understanding the disease” in the INSERM file opens with the following paragraph:

Rare before the age of 65, Alzheimer’s disease begins with loss memory, followed over the years by more general and disabling cognitive disorders (…) After 65, the incidence rate of the disease rises from 2 to 4% of the general population. It rises rapidly to reach 15% of the population at age 80. About 900,000 people suffer from Alzheimer’s disease in France today. The number should reach 1, 3 million in 2020, given the increase in life expectancy.

It should first be observed that there are no explanations given for the two age limits chosen – 65 and 80 – which merely seem to refer to the distinction that is commonly made in everyday language between senior citizens and elderly dependents. Age is only considered here in a chronological way. This understanding of age thus seems to derive from convention rather than scientific results or hypotheses about biological deterioration or the effects of social or psychological aging.

As for prevalence, the reading of scientific papers helps trace the way the figures have been established. The most widely cited paper [11] (i.e. cited about 150 times) estimated the proportion of sick people to be 17,8% among people aged 75 or more in 2003, which amounted to 769,000 people. A later, also much cited (47 times), paper [12] indicated that there were about 850,000 cases of Alzheimer’s disease and related syndromes at the time. To support these figures, the second paper referred to the same source as the first one, a survey entitled Personne âgée quid (Paquid). This population-based cohort study, initiated in 1988, targeted 3,777 people aged 65 or more in towns and villages of the Gironde and Dordogne departments and consisted in an epidemiological study of cognitive and functional aging. Dementia and its level of severity were measured using a clinical test, the Mini Mental State (MMS). The number of sick people given by the Paquid survey was then estimated through a projection by age to the general population. The 900,000 cases announced in the INSERM report thus do not correspond to diagnosed cases – I will come back to the meaning of this term below – but to estimates based on a clinical test carried out on a limited sample as pointed out by [13].

Population and Diagnostic Differences Behind Age

As Ankri pointed out, the epidemiological studies giving the incidence and prevalence rates of the disease by age present strong methodological limitations. Apart from the fact that it is difficult to constitute representative samples, they are based on very different patient populations. Ankri explains that the estimated rates often result from the collection of data from surveys of populations affected by very different physio-pathological types of dementia. Moreover, the diagnoses and measurement tools differ depending on the protocols used:

Estimates are most frequently based on nonrepresentative samples and case identification procedures vary with the evolution of diagnostic criteria and the availability of imaging or biological markers. Moreover, whether studies of mild or severe forms of dementia or residents of institutions are included or not can have a strong impact on the results (Ankri, op.cit. p. 458)

While age groups are considered as uniform categories, they include people suffering from different degrees and sometimes even types of dementia. Under chronological age are subsumed different cases, as if people from the same age group were “medically comparable” even though there can be a great number of different risk factors associated to different types of dementia (vascular, Lewy Body, Alzheimer). Moreover, from a methodological point of view, the motivations for taking part (or refusing to take part) in a survey are known to be diverse and to have an impact on the results of clinical tests. When age – merely viewed in its chronological aspect – is used to constitute groupings, researchers lose sight of its social dimension and of its potential influence on the data collected.

Age: A Mere Variable or a Risk Factor?

When these epidemiological data are used, chronological age is considered as a risk factor since incidence rate seems to increase with age. In statistical terms, age even appears to be the main risk factor. Let us look more closely at the findings of epidemiology [14]. The works based on cohort analysis confirm that age is the main risk factor and add that incidence doubles “practically for every five-year age group after 65” (Ibid., p. 738). They also confirm that the incidence rate is higher among women, while indicating that “In the Paquid survey, the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease was higher among men than women before 80, whereas the reverse was true after 80” (Ibid., p. 739). The difference between men and women is accounted for in the following way:

Life expectancy, which is higher for women than men, might explain the results, assuming that men, with increased longevity, are more resistant to neurodegenerative diseases. It can be observed that in some countries like the United States where the gap between life expectancy for men and women is smaller, there is no gender difference in the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease. (Ibid., p. 739)

This is a classical hypothesis in longevity research, which suggests that the selection effect might be stronger for men and that, as a result only the most physically and cognitively strong might reach advanced age [15].

Moreover, interpreting these age-related findings is a complex task because a risk factor means a notable frequency of simultaneous occurrence of two variables, here age and a negative result in a clinical and/or neuropsychological test like the MMS. The risk factor is measured for a population but implies no causality at the individual level. In order to interpret this correlation as causality, other aspects of age must be considered beside its mere chronological reality.

Age as a Cause of the Disease?

Since the literature on Alzheimer’s disease is mostly based on medical and biological research, age is viewed from a physiological point of view. The passage of time is considered as responsible for physiological wear and tear and biogenetic damage and alterations of the human body and brain. It is believed, then, that alterations multiply with age, which is why the prevalence of dementia is understood to increase with chronological age. According to some researchers [16], most of the clinical studies that have investigated the cognitive capacities of centenarians have concluded that 50 to 75% of them suffered from “cognitive impairments”. Although they are a rapidly growing population, centenarians have so far rarely been considered as subjects for the study of Alzheimer’s disease. There are many reasons for this. First, they are considered to be statistically too few in number and to have too short a life expectancy for cohort analysis, and, second, they seem difficult to study. [13] drew the following conclusion:

Finally, because of the increase of prevalence and incidence with age, another source of uncertainty lies in the low representation of the very elderly (over 90 years old) in epidemiological studies, which makes estimation of prevalence and incidence at the most advanced ages uncertain. (…) the lack of data about the very elderly leaves two questions open: either there is an exponential increase of incidence in dementia with age, which means for some that it is an aging-related phenomenon rather than a disease; or the decrease of incidence beyond a certain age, after quasi-exponential growth, shows that it is rather an age-related disease.

The quasi-linear increase of dementia prevalence with age remains a major focus of reflection since it raises questions about the very essence of what is called “Alzheimer’s disease”. According to some researchers [17], what is called Alzheimer’s disease is not in fact a disease (i.e. a clearly defined pathology with a proven etiology), but rather a syndrome, i.e. a set of more or less unified symptoms grouped under the same generic term. These symptoms might then simply be an effect of senescence and manifest themselves with great interindividual variety. This hypothesis stands all the more if the diagnosis – and the subsequent labelling process [18] – rests on clinical tests in which failure is correlated with senescence. As [19], this hypothesis questions the social and political construction of the disease, which is based on a distinction between Alzheimer’s disease, senility and senescence.

In such context, diagnosis is a crucial stage to distinguish between “Alzheimer’s disease” and other possible causes of dementia. Yet diagnostic procedures are intrinsically linked to the etiology of the disease: they depend one on the other.

The Etiology and Diagnosis of the Disease

To understand “diagnostic procedures” and the etiological issues they raise, it is useful to trace the history of the way the disease was defined.

Senile or Presenile Dementia?

One of the oldest and most famous debates about the etiology of Alzheimer’s disease also has to do with the link between age and disease. In his history of Alzheimer’s disease, [20] charts the process of construction of what is called “Alzheimer’s disease” and points out that it was first considered as “presenile dementia”. There were many reasons for this. Continuing the work of Aloïs Alzheimer on the “first patient” Auguste D, Perusini observed correspondences as well as morphological (cerebral modifications) and symptomatic differences with senile dementia. Yet this is not what really motivated the distinction. Berrios (1989, quoted by Gzil. Op. cit.) points out that the anatomopathological features (amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles) that Aloïs Alzheimer considered to be possible specificities had already been identified by Ficher and that he considered them to be relatively frequent occurrences in dementia in elderly people. He therefore proposed the name of “presbyophrenic dementia” for all types of senile and presenile dementia in which plaques and sometimes fibrillary alterations could be observed. The reasons why Alzheimer’s disease was distinguished from senile dementia lie first in the fact that Aloïs Alzheimer had no occasion to conduct histological examinations of elderly patients (as he himself recognized). Another reason was the then popular conception of mental illness, inherited from Kahlnaum (Krepelin’s mentor, Krepelin being himself Alzheimer’s mentor), according to which there were specific diseases for every stage of life. As Gzil points out, in the 19th century, many psychiatrists believed that mental disease was related to age.

The table presented by [20] listing the cases of Alzheimer’s disease published between 1907 and 1914 can provide further insights. The table lists 22 cases, with the youngest patient having been diagnosed at 32 and the oldest at 63. The average age at diagnosis was 57 and, apart from 3 cases, they were all diagnosed after 48. Today most of these people would be considered as young patients, but what did these ages mean in the early 19th century in biological, demographic and social terms? In demographic terms, with life expectancy at birth being about 50 at the time, it is debatable whether these patients could be described as young. If the average age at diagnosis were 7 years higher than life expectancy at birth today, it would be 87. Would the people diagnosed at that age be considered as young patients? Moreover, biologically (wear and tear) and sociologically (status and role in society) speaking, were these people young? It is quite difficult to answer this question, which in turn raises the issue of how to define old age [21].

Whether Alzheimer’s disease is a form of senile or presenile dementia was not decided on the basis of age but of the anatomopathological features of the disease. While clinicians believed there were two separate diseases, at the end of the 1960s, anatomopathologists justified the “merging” of the two on account of their biological manifestations. [19] showed that community and pharmaceutical lobbying also supported this classification under a single label. Today, the only age-related distinction is based on genetic arguments and establishes a separation between autosomal (genetic) and sporadic forms.

Biological Markers: The Causes of the Disease?

The features that Aloïs Alzheimer identified in Auguste D (and Fischer in other patients), i.e. amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary degeneration, are still considered today as the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease. The INSERM file indicates that:

Study of the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease shows the presence of two types of lesions which make diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease a certainty: amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary degeneration.

It is important to insist on the fact that these biological features are what makes diagnosis certain because diagnosing the disease is not an easy task as Pr. Philippe Amouvel, one of the French experts of the disease, explained: “Today, we are used to referring to any memory disorder as Alzheimer’s disease while in reality, it takes a very long, very complex work to make a diagnosis” [22]. While in Aloïs Alzheimer’s time, such “alterations” (amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles) could only be identified post mortem, new medical techniques have been developed in order to trace the lesions at the root of cognitive disorders that can then be identified through the use of clinical tests. Two main types of “diagnostic techniques” can be distinguished: the identification of biological and/or genetic markers thanks to lumbar puncture and medical imaging. These examinations are performed on living subjects, either subjects experiencing clinically assessed health problems, or healthy subjects being tested for research purposes. As underlined by some publications [23], the possibilities offered by these technical advances have reinforced a biological understanding of the disease, in which biomarkers are considered both as signs and causes of the disease. This so-called improvement in diagnosis certainty actually results in enhancing the biological aspects of “Alzheimer’s disease” and supporting an etiology based on the “amyloid cascade” hypothesis. This hypothesis posits that the deposition of amyloid-beta peptide in the brain leads to brain disorders. Although this hypothesis is sometimes debated [24], the causal process it describes constitutes the focus of most of the research today. The INSERM file specifies that:

Amyloid beta protein, naturally present in the brain, accumulates over the years under the influence of various genetic and environmental factors, until it forms amyloid plaques (also called “senile plaques”). According to the “amyloid cascade” hypothesis, it would seem that the accumulation of this amyloid peptide induces toxicity in nerve cells, resulting in increased phosphorylation. (…) Hyperphosphorylation of tau protein leads to a disorganization of neuron structure and so-called “neurofibrillary” degeneration which will itself lead, in the long run, to the death of the nerve cell.

While a few years ago, diagnosis was based on the clinical signs of the disease, today clinical-biological criteria are used, leading to an ATN classification system. The deposition of amyloids (A), Tau protein (T) and Neurodegeneration (N) (cerebral modifications) are considered as both biomarkers and causes of the disease. Medical neuroimaging (magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography) makes it possible to visualize cerebral atrophies and hypometabolism which are considered as signs of neuronal and synaptic dysfunction [25].

From a clinical point of view, it is important to detect the biomarkers at an early stage in order to identify “the people who have these biomarkers and are worried about their memory and to offer them, long before they decline, long before they enter the clinical disease stage, strategies to avoid cognitive decline” (Dr. Audrey Gabelle, Pr. of neurology and neuroscience, University of Montpellier, 01/04/2021).

Biological Lesions and Clinical Disorders: An Etiological Paradox?

The significance of early detection rests on the theory that there is a prodromal stage of Alzheimer’s disease in which biological signs are present in the brains of the “patients” even though they do not experience any problem or present any clinically identifiable symptom. Yet some studies have suggested that there is no such clear link between biomarkers and clinically assessed disorders:

Several studies have shown that the extent of neuropathological changes and the degree of cognitive impairment were poorly related in the very elderly. In examinations conducted on centenarians it has been shown that several subjects did not present any cognitive impairment despite extensive neuropathological abnormalities and conversely, that several subjects who presented significant cognitive impairment did not have neuropathological abnormalities. In this context, even beyond the issue of correct interpretation of the epidemiological data, some have raised the conceptual question of whether dementia should be considered as an age-related phenomenon (generally occurring around a specific age) or a normal consequence of aging [26].

On this point, the “Nun Study” sparked considerable discussion in the scientific literature, especially the case of Sister Mary [27]. The study was based on a population of 678 nuns aged from 75 to 103. It focused on nuns in order to better control the environmental (social status) and behavioral (tobacco and alcohol consumption) factors that can have an impact on cognitive impairment. Sister Mary died at 101. Until her death, she had had high scores in cognitive tests and appeared to be “cognitively intact”. Yet the autopsy (the currently used “diagnostic techniques” were not as advanced then as they are now) of her brain revealed large numbers of neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques. Sister Mary is not, in fact, an isolated case. Several studies based on post mortem anatomopathological data have shown that in a significant number of cases, there is no link between the presence or absence of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary degeneration and the presence or absence of cognitive disorders. The study conducted by Zekri et al. (2005) on 209 autopsied subjects (100 demented and 109 non-demented subjects) indicated that “even more surprising were the observations made in 109 non-demented subjects: in 33% of the cases, the density of neurofibrillary degeneration of the isocortex was equivalent to that of demented subjects” (p. 253). In this study, the brains of 1/3 of the subjects with no clinical sign of dementia had the same biophysiological markers as those of subjects with Alzheimer’s disease.

While the idea that there is a pre-symptomatic stage of the disease has been challenged by these studies, on account of the mismatch between the number of lesions and the presence of cognitive disorder, some suggest that this paradox might be explained through the notions of brain plasticity and cognitive reserve. They believe that some brains have the ability to offset or stave off lesions and continue to function “in a normal way”.

Towards a “Geneticization” of Alzheimer’s Disease?

Another explanation is also used to account for this paradox, whose effect is to redefine the etiology and reinforce the idea that the disease might have genetic origins.

Genetic Causes for the Appearance of Biological Lesions?

In their analysis of the origins of Alzheimer’s disease, some researchers [28] underline the fact that while there is no correlation between the presence of amyloid peptide and the existence of symptoms, the symptoms are correlated with neuronal death which they believe is caused by an abnormal amount of Tau protein. This leads to a rather different causal pattern. In this perspective, genetic factors – particularly the APOE gene [29] – and environmental factors are believed to be responsible for the amyloid cascade and the abnormal production of amyloid peptide affecting Tau protein and leading to neuronal death. This gives rise to a much clearer causal pattern with the following successive, rather than concomitant, stages: genetic (and environmental) factors à amyloid à Tau à neuronal death à clinical symptoms. It should be said that this causal pattern is causing debate among researchers for several reasons. First, some studies [30] point out that the causal succession of amyloid plaques and Tau phosphorylation must be reexamined since Tau protein can appear before the plaques do. Moreover, accumulated Tau protein can also be found in “the brains of elderly and cognitively healthy subjects but in relatively moderate quantities” (Wallon, op. cit). Yet these observations do not call into question the idea that there is a pre-symptomatic stage during which the disease develops in invisible ways. There have been much cited hypotheses and models [31] to describe this development process but researchers do not have sufficient longitudinal data to confirm them yet.

From Genetic Models to Sporadic Forms

Faced with this methodological problem which makes it difficult to confirm or refute the hypotheses and models being discussed, some researchers have turned to genetic models. The first genetic model is based on autosomal Alzheimer’s disease. According to the INSERM file: “Hereditary forms of Alzheimer’s disease account for 1,5% to 2% of the cases. They almost always occur before 65, often around 45 years old. In half of the cases, rare mutations have been identified as the root of the disease”. Researchers have been able to follow the evolution of the disease in these patients carrying a rare genetic marker causing the development of lesions (amyloid and Tau), leading them to think that the pathology might begin 15 years before the clinical signs appear. On this basis, the genetic forms of the disease have been considered as a model to approach sporadic forms. Yet this approach can be questioned since in the general population, 50% of the study subjects with biomarkers (amyloid and Tau) of the disease did not develop any symptom over a ten years’ period [32].

The other genetic model used is an animal model. Several studies of Alzheimer’s disease, including those which gave rise to the amyloid cascade hypothesis [33], are based on in vitro experiments conducted on the brains of mice or other marsupials such as mouse lemurs. They rely on the assumption that the results obtained from mouse brains can be “transferred” to the human brain. Yet comparing the two is by no means easy since mice do not “naturally” develop Alzheimer’s disease as it is today defined and it is debatable whether clinical tests performed on animals can be assimilated to those used to make a diagnosis on human subjects. The mice used in laboratories are “models”, i.e. they have been genetically modified so as to develop Alzheimer’s disease. The studies in immunotherapy carried out by [34] made this point very clear. The mice used, APPswe/PS1ΔE9 models, overexpressed mutated forms of the human APP gene and the human PSEN1 gene and were compared to so-called “wild-type” mice from the Jackson Laboratory.

In addition to the fact that this model appears to be far removed from the reality of sporadic Alzheimer’s disease, it is also questionable whether its results can be used because it completely overlooks “environmental” risk factors in order to promote an exclusively genetic explanation. The limitations inherent in investigations of human and sporadic forms of the disease thus result in the construction of models which are based on comparison and end up eliminating one of the factors that was initially considered as responsible for the disease. This paper suggests that the development of such models is to be understood within a broader movement towards defining the elderly as biologically specific individuals.

Conclusion

Through analysis of the etiological construction of Alzheimer’s disease, this paper provides some insights for a sociological study of Alzheimer’s disease, following previous work in anthropology [35] and sociological studies of other biomedical subjects such as procreation [36]. This approach reveals that natural sciences – however hard they may be considered to be – also construct their research subjects on the basis of technical advances and out of the necessity of bypassing existing methodological obstacles.

This paper has shown that the way age is understood and used in research on Alzheimer’s disease can result in shortcuts, whereby statistical correlations are transformed into causal links, and in classification of the patients into falsely unifying categories. It has also questioned the boundaries between early dementia, late dementia and senescence by showing that the difficult interpretation of chronological age and the almost total lack of data about certain age groups are barriers to reflection and raise questions as to the very nature of what we call “Alzheimer’s disease”.

The medicalization of society which has long been observed by health sociologists is today compounded, in the case of Alzheimer’s disease (but not only), by increasingly biological [37] and genetic interpretations of the human being. Yet, while study of the biomarkers triggering amyloid cascade can yield helpful results, this line of research needs to be carefully scrutinized just as research seeking to identify prognostic biomarkers for psychiatric disorder in children has been [38]. Individuals in the asymptomatic phase are not, clinically speaking, sick. The desire to prevent development of the disease should not blind researchers to the possible social and human consequences. Similarly, advances in genetics should not cause unquestioning acceptance of genomic medicine [39-42] and its probabilistic interpretations of individual fates. I believe that, even before looking at the possible social and political effects of biomedical paradigms and practices on society and individuals, a sociology of Alzheimer’s disease should focus its attention on the research being conducted and show its historicity, constructions and controversial issues as a way to shed light on the modern forms of biopower. Yet, this type of work doesn’t appear to be in line with funders’ and research institutes’ demand for interdisciplinary research. Multi-disciplinary research, which means looking at the same subject from different points of view based on specific epistemological principles, certainly needs to be pursued; on the other hand, inter-disciplinary research, which means orienting different types of disciplinary research towards the same direction, appears to me to be highly counter-productive while trans-disciplinarity (which blurs or erases historical and epistemological differences between disciplines) can be considered as dystopian.

References

- Bury M (1988) Arguments about ageing: long life and its consequences in N. WELLS, C. FREER (dir.), The Ageing Population, London, Palgrave 17-31.

- Barnes Rf, Raskind MA, Scott M, Murphy C (1981) Problems of families caring for Alzheimer patients: Use of a support group. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 29: 80-85. [crossref]

- Lazarus LW, Stafford B, Cooper K, Cohler B, Dysken M (1981) A pilot study of an Alzheimer patients’ relatives discussion group. The Gerontologist 4: 353-358.

- SOUN E (1999) Des trajectoires de maladie d’Alzheimer, Thèse de doctorat en sociologie, Brest, Université de Bretagne.

- Ngatcha-Ribert L (2007) La sortie de l’oubli: la maladie d’Alzheimer comme nouveau problème public. Sciences, discours et politiques, Thèse de doctorat de sociologie, Paris, Université Paris-Descartes.

- Ngatcha-Ribert L (2012) Alzheimer : la construction sociale d’une maladie, Paris, Dunod.

- Chamahian A, Caradec V (2014) Vivre « avec » la maladie d’Alzheimer : des expériences en rupture avec les représentations usuelles de la maladie. Retraite et Société 3: 17-37.

- Pestre D (2001) Études sociales des sciences, politique et retour sur soi éléments. Revue du MAUSS 1: 180-196.

- Lock M, Gordon D (2012) Biomedicine examined, New York, Springer Science & Business Media.

- Bourdieu P (1975) La spécificité du champ scientifique et les conditions sociales du progrès de la raison. Sociologie et sociétés 7 : 91-118.

- Ramaroson H, Helmer C, Barberger-Gateau P, Letenneur L, Dartigues JF (2003) Prévalence de la démence et de la maladie d’Alzheimer chez les personnes de 75 ans et plus: données réactualisées de la cohorte Paquid. Revue Neurologique 159: 405-411.

- Helmer C, Pasquier F, Dartigues JF (2003) Épidémiologie de la maladie d’Alzheimer et des syndromes apparentés. Médecine/sciences 22: 288-296.

- Ankri J (2016) Maladie D’Alzheimer, l’enjeu des données épidémiologiques. Bulletin Hebdomadaire d’Epidémiologie 458-459.

- Dartigues JF, Berr C, Helmer C, Letenneur L (2002) Épidémiologie de la maladie d’Alzheimer. Médecine/sciences 18 : 737-743.

- Balard F (2013) Des hommes chênes et des femmes roseaux : hypothèse de recherche pour expliquer le paradoxe du genre au grand âge », in I. VOLERY, M. LEGRAND (dir.), Genre et parcours de vie, vers une nouvelle police des corps et des âges 100-106.

- Poon LW, Jazwinski M, Green RC, Woodard JL, Martin P, et al. (2007) Methodological considerations in studying centenarians: lessons learned from the Georgia centenarian studies. Annual review of gerontology & geriatrics 27: 231-264.

- Whitehouse PJ, George D, Van Der Linden ACJ, Vander Linden M (2009) Le mythe de la maladie d’Alzheimer : ce qu’on ne vous dit pas sur ce diagnostic tant redouté, Louvain la Neuve, Éditions Solal.

- Ehrenhberg A (2004) Remarques pour éclaircir le concept de santé mentale. Revue française des affaires sociales 1: 77-88.

- Fox P (1989) From senility to Alzheimer’s disease: The rise of the Alzheimer’s disease movement. The Milbank Quarterly 67: 58-102. [crossref]

- Gzil F (2009) La maladie d’Alzheimer : problèmes philosophiques, Paris, Presses universitaires de France.

- Bourdelais P (1993) L’Âge de la vieillesse, Paris, Odile Jacob.

- AMOUYEL P (2020) Avons-nous les outils pour faire un diagnostic dès les premiers signes de la maladie d’Alzheimer ? Troisième conférence de la fondation Alzheimer, le 01/04/2021.

- Burnham SC, Colona PM, Li QX, Collins S, Savage G, et al. (2019) Application of the NIA-AA research framework: towards a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease using cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in the AIBL study. The journal of prevention of Alzheimer’s disease 6: 248-255. [crossref]

- Chételat G (2013) Reply: The amyloid cascade is not the only pathway to AD. Nature Reviews Neurology 9: 356. [crossref]

- Chételat G, Arbizu J, Barthel H, Garibotto V, Law I, et al. (2020) Amyloid-PET and 18F-FDG-PET in the diagnostic investigation of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. The Lancet Neurology 19: 951-962. [crossref]

- Ankri J (2006) Epidémiologie des démences et de la maladie d’Alzheimer. La santé des personnes âgées 42: 42-44.

- Snowdon DA (1997) Aging and Alzheimer’s disease: lessons from the Nun Study. The Gerontologist 37: 150-156. [crossref]

- Wallon D (2020) Avons-nous les outils pour faire un diagnostic dès les premiers signes de la maladie d’Alzheimer? Troisième conférence de la fondation Alzheimer, le 01/04/2021.

- Genin E, Hannequin D, Wallon D, Sleegers K, Hiltunen M, et al. (2011) APOE and Alzheimer disease: a major gene with semi-dominant inheritance. Molecular psychiatry 16: 903-907. [crossref]

- Morris GP, Clark IA, Vissel B (2018) Questions concerning the role of amyloid-β in the definition, aetiology and diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta neuropathologica 136: 663-689. [crossref]

- Jack jr CR., Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Shaw LM, Aisen PS, et al. (2010) Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer’s pathological cascade. The Lancet Neurology 9: 119-128. [crossref]

- Stomrud E, Minthon L, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Hansson O (2015) Longitudinal cerebrospinal fluid biomarker measurements in preclinical sporadic Alzheimer’s disease: A prospective 9-year study. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring 1: 403-411. [crossref]

- Janus C, Pearson J, Mclaurin J, Mathews PM, Jiang Y, et al. (2000) Aβ peptide immunization reduces behavioural impairment and plaques in a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 408: 979-982. [crossref]

- Alves S, Churlaud G, Audrain M, Michaelsen-Preusse K, Fol R, et al. (2017) Interleukin-2 improves amyloid pathology, synaptic failure and memory in Alzheimer’s disease mice. Brain 140: 826-842. [crossref]

- Droz Mendelzweig (2009) Constructing the Alzheimer patient: Bridging the gap between symptomatology and diagnosis. Science & Technology Studies 2 : 55-79.

- Déchaux JH (2019) L’individualisme génétique: marché du test génétique, biotechnologies et transhumanisme. Revue française de sociologie 60 : 103-115.

- Rose N (2013) The human sciences in a biological age. Theory, culture & society 30: 31-34.

- Singh I, Rose N (2009) Biomarkers in psychiatry. Nature 460: 202-207.

- Déchaux JH (2018) Le gène à l’assaut de la parenté ? Revue des politiques sociales et familiales 126: 35-47.

- Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger Tl, Fagan Am, Goate A, et al. (2012) Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 367: 795-804. [crossref]

- Gabelle A (2020) Avons-nous les outils pour faire un diagnostic dès les premiers signes de la maladie d’Alzheimer ? Troisième conférence de la fondation Alzheimer, le 01/04/2021.

- TREMBLAY MA (1990) L’anthropologie de la clinique dans le domaine de la santé mentale au Québec. Quelques repères historiques et leurs cadres institutionnels, 1950-1990. Anthropologie et sociétés 14: 125-146.