DOI: 10.31038/JCCP.2021414

Abstract

The author has undertaken multiple electrocardiographic studies during his academic career; most of these were published in peer-reviewed journals. These studies include, normal Frank and McFee vector-cardiograms in the adolescent, diagnosis by intra-cavitary electrocardiography of Ebstein’s anomaly of the left atrio-ventricular valve in congenital corrected transposition of the great arteries, differentiation of right ventricular hypertrophy from posterobasal left ventricular hypertrophy, electrocardiographic features of tricuspid atresia, mechanism of abnormal superior vector (left axis deviation) in tricuspid atresia, mechanism of alternating failure of mechanical to electrical depolarization (AFORMED) phenomenon, racial variations in electrocardiograms and vectorcardiograms between black and white children, congestive cardiomyopathy due to chronic tachycardia: resolution with medications, electrocardiographic changes following balloon valvuloplasty for pulmonary stenosis, the role of the electrocardiogram in delineating atrial and ventricular situs in patients with dextrocardia and heterotaxy syndromes, and a review of arrhythmias.

Keywords

AFORMED phenomenon, Arrhythmias, Balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty, Congestive cardiomyopathy, Corrected transposition, Dextrocardia, Ebstein’s anomaly, Electrocardiogram, Vector-cardiogram, Ebstein’s anomaly, Intra-cavitary electrogram, Left axis deviation, Pulmonary stenosis, Racial variations, Right ventricular hypertrophy, Tricuspid atresia

Introduction

My fellowship training under the tutelage of Dr. Jerome Liebman, an outstanding electro-cardiographer of the 1970s, at the Babies’ and Children’s Hospital of Cleveland/Case-Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, resulted in my exposure to clinical electrocardiography and research on electro-vector-cardiography. This training was useful in conducting research studies involving electrocardiography. In this review, I will enumerate my contributions in the field of electrocardiography literature.

Normal Frank and McFee Vectorcardiograms in the Adolescent

I actively participated in the study of normal vectorcardiograms (VCGs) in adolescents [1]. Frank and McFee VCGs of 166 normal adolescents were analyzed. Normal values in adolescents were published in 24 tables [1]. The QRS and T magnitudes were higher in the male than in the female subjects; this difference was larger in 11- to 15-year-olds than in 16- to 19-year-old adolescents. This was attributed to females reaching puberty earlier than males. In addition, the male subjects achieved the maximal posterior QRS orientation much sooner than the females. The study also noted significant differences between the Frank and McFee VCG lead systems [1].

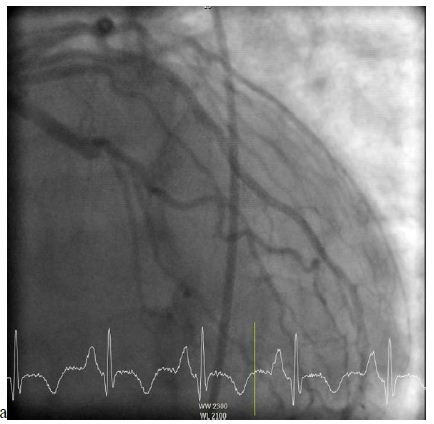

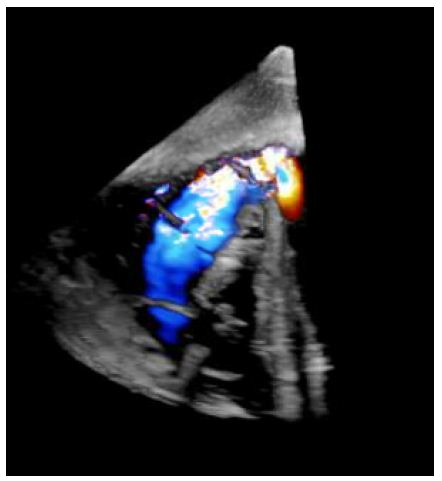

Diagnosis by Intra-cavitary Electrocardiography of Ebstein’s Anomaly of the Left Atrio-ventricular Valve in Congenital Corrected Transposition of the Great Arteries (CCTGA)

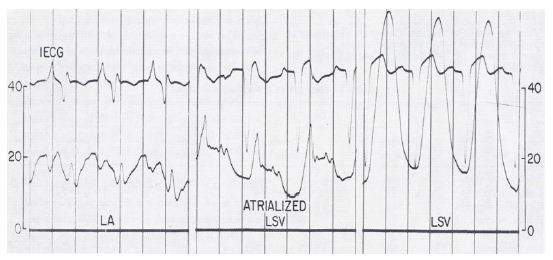

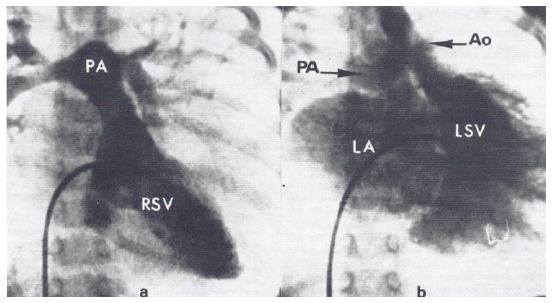

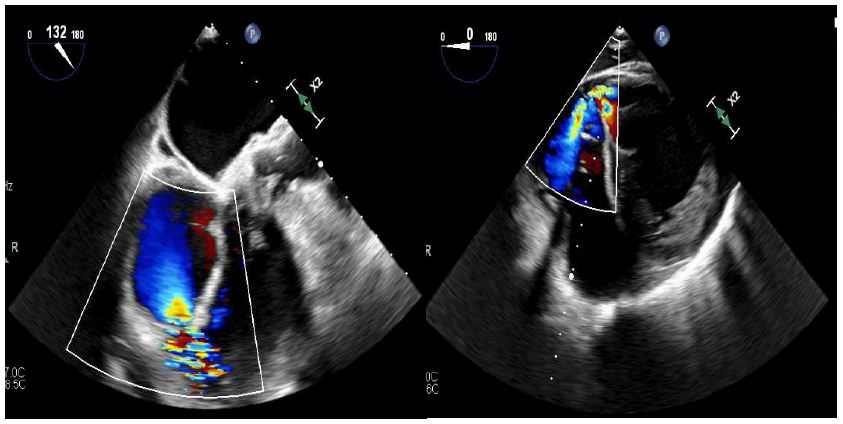

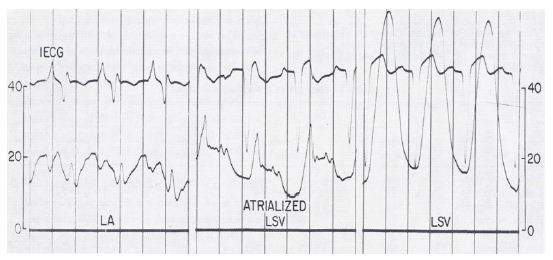

The diagnosis of Ebstein’s anomaly of the tricuspid valve by the simultaneous recording of intra-cavitary electrocardiograms and pressures across the tricuspid valve was a well-established technique as of the mid-1970s. However, such a method has not been used to diagnose Ebstein’s anomaly of the left atrioventricular valve in patients with CCTGA. We made simultaneous intra-cavitary electrocardiographic and pressure recordings across the left atrioventricular valve simultaneously (Figure 1) in a 13-month-old infant with angiographically confirmed CCTGA and left atrioventricular valve insufficiency (Figure 2) [2]. These recordings were similar to those obtained in classic cases of Ebstein’s anomaly of the tricuspid valve.

Figure 1: Simultaneous recording of intra-cardiac electrocardiogram (ECG) and pressures as the electrode/pressure recording catheter is slowly withdrawn from the left atrium (LA) to the left-sided, morphology-right ventricle (LSV). The left panel shows the atrial pressure curve with an atrial electrogram. The middle panel shows the atrial pressure curve with a ventricular electrogram when the tip of the catheter is in the atrialized ventricular chamber. The right panel shows the ventricular pressure curve with a ventricular electrogram when the tip of the catheter is in the ventricular chamber. Pressure is marked in mmHg. The pressure in LSV is damped because of the small diameter of the catheter. Reproduced from Rogers JH, Jr, Rao PS. (1977) Chest 72: 253-256 [2].

Figure 2: a. Selected frame of right-sided ventricular (RSV) cineangiogram demonstrating smooth-walled morphologic left ventricle on the right side with opacification of the pulmonary artery (PA). b. Selected frame of left-sided ventricular (LSV) cineangiogram demonstrating coarsely trabeculated morphologic right ventricle on the left side with opacification of the aorta (Ao). Note the significant left-sided atrioventricular valve insufficiency, resulting in the opacification of the left atrium (LA). The PA is also opacified because of a left-to-right shunt via a ventricular septal defect (not marked). Reproduced from Rogers JH, Jr, Rao PS. (1977) Chest 72: 253-256 [2].

In the discussion section, we reviewed the historical aspects of CCTGA, described the anatomy and typical angiographic findings of the condition, and pointed out the frequent association of Ebstein’s type of malformation of the left-sided, morphologic tricuspid valve in CCTGA, and the usefulness of recognizing this abnormality in the management of CCTGA [2]. The characteristic features of Ebstein’s are 1. atrial pressure with atrial electrogram, 2. atrial pressure with ventricular electrogram, and 3. ventricular pressure with ventricular electrogram, in that order, as the electrode catheter is slowly withdrawn from the left atrium to the left-sided, morphology-right ventricle (Figure 1) [2]. Based on a thorough literature review, we determined that this was the first reported case of intra-cavitary electrocardiogram in a patient with CCTGA with Ebstein’s malformation of the left-sided, morphologic right atrioventricular valve. We emphasized the usefulness of the simultaneous recording of the intra-cavitary electrograms and pressures in the diagnosis of Ebstein’s anomaly of the left atrioventricular valve in patients with CCTGA [2].

Right Ventricular Hypertrophy Vs. Posterobasal Left Ventricular Hypertrophy

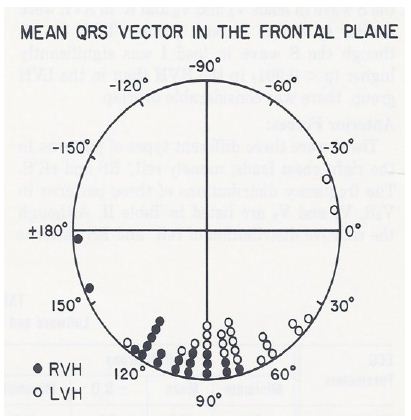

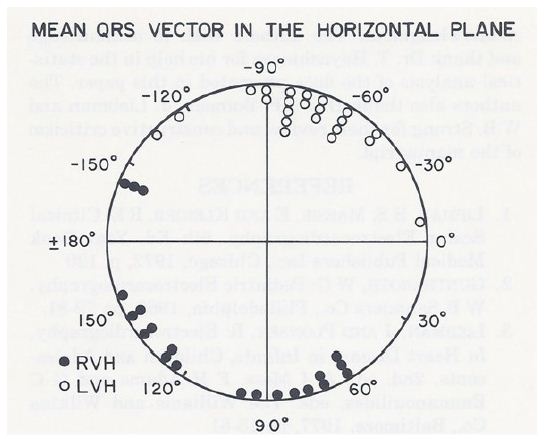

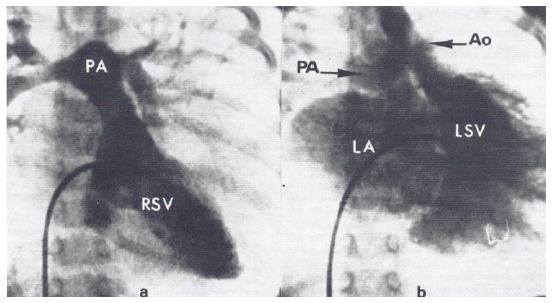

Both right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH) and posterobasal left ventricular hypertrophy (PBLVH) manifest by S waves greater than the 95th percentile in leads V5 and V6. At the time of our paper in 1981 [3], there were no published criteria to differentiate these two entities. To address this issue, we examined the ECGs of 5,240 patients; of these, 445 (8.5%) patients had S waves in lead V5 deeper than 95th percentile for age [3]. From these, the ECGs of 46 patients with cardiac lesions known to cause “isolated” RVH and 38 patients with lesions known to produce PBLVH were selected for further analysis. Criteria other than increased S waves in V5 & V6 were evident in 26 patients in the RVH group and 15 in the PBLVH group. The ECGs of the remaining 21 in the RVH group and 23 in the PBLVH group, which did not have other criteria to diagnose either RVH or PBLVH, were examined in detail. The results were presented in multiple tables and figures in the said paper [3]. There was considerable overlap of the frontal plane mean QRS vector (axis) of both groups (Figure 3).

Figure 3: The frontal plane mean QRS vectors in degrees, calculated from the scalar ECG, are shown for each of the right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH) (in closed circles) and posterobasal left ventricular hypertrophy (PBLVH) (in open circles) cases. There is considerable overlap of the mean vectors of both the groups. Consequently, the frontal plane mean QRS vector is not useful in distinguishing RVH from PBLVH. Reproduced from Rao PS, Monarrez CN. (1981) J Electrocardiol 14: 25-30 [3].

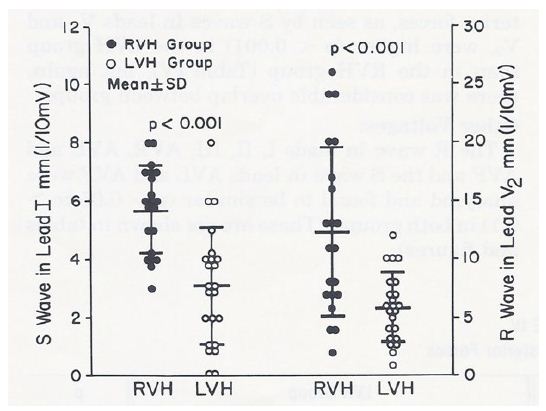

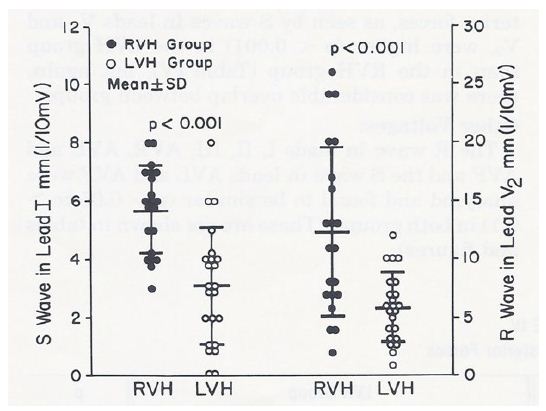

Terminal rightward forces (S waves in leads V5 and V6 and R waves in AVR), leftward forces (R waves in leads V5 and V6), other voltages (R waves in leads I, II, III, AVR, AVL and AVF and S waves in AVL and AVF) and ratio of RV5/SV5 were similar (p > 0.05 to 0.1) for both groups. However, anterior forces (R waves in leads V1 and V2), S wave in lead I and ratio of RV2/SV2 were higher (p < 0.05 to 0.01) in the RVH than in the PBLVH group. Similarly, posterior forces (S waves in leads V1 and V2) were higher (p < 0.001) in the PBLVH than in the RVH group. Despite these statistically significant differences, there was considerable overlap between these values, as shown in Figure 4, and consequently, these differences are not helpful in differentiating RVH from PBLVH.

Figure 4: S waves in lead I and R waves in lead V2 in mm (1/10 mV) are depicted in the left and right panels, respectively. The right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH) cases are shown in closed circles and the posterobasal left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) cases are illustrated in open circles. The mean and standard deviation are marked as horizontal lines. While there are statistically significant differences (p < 0.001) between groups, there is considerable overlap of the voltage magnitudes. Therefore, these voltages are not useful in differentiating RVH from LVH. Reproduced from Rao PS, Monarrez CN. (1981) J Electrocardiol 14: 25-30 [3].

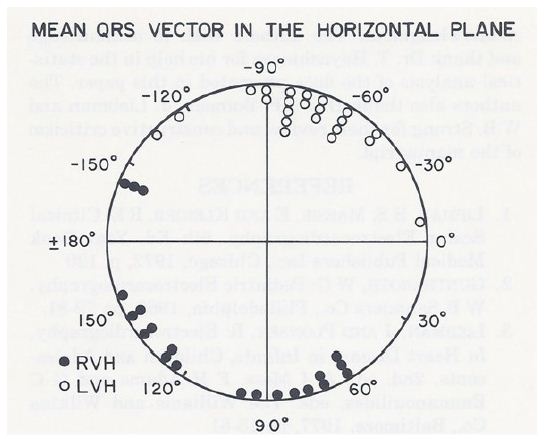

Therefore, the data were subjected to discriminant analysis. The results of this analysis indicated cases of RVH if the S wave in lead I was greater than 5 mm, the R wave in lead V2 was greater than 10 mm and the ratio of the R wave in V2/S wave in V2 was greater than 0.65; and of PBLVH if the S wave in lead I was less than 5 mm, the R wave in V2 was less than 10 mm and the ratio of the R wave in V2/S wave in V2 was less than 0.65. In addition, the mean horizontal plane QRS vector was between +60 degrees to +200 degrees in the RVH cases, while the mean horizontal plane QRS vector was between -10 degrees to -130 degrees in the PBLVH group (Figure 5). In addition, the horizontal plane QRS vector loops had a clockwise or figure of 8 rotation in the RVH group, while they had a counterclockwise loop in the PBLVH group (Table 1).

Figure 5: The horizontal plane mean QRS vectors in degrees, calculated from the scalar ECG, are shown for each of the right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH) (in closed circles) and posterobasal left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) (in open circles) cases. The mean horizontal plane QRS vector is between +60 degrees to +200 degrees in the RVH cases while the mean horizontal plane QRS vector is between -10 degrees to -130 degrees in the LVH cases. Unlike the frontal plane mean QRS vectors, there is no significant overlap of mean vectors between the groups. Consequently, the horizontal plane mean QRS vector is helpful in distinguishing RVH from LVH. Reproduced from Rao PS, Monarrez CN. (1981) J Electrocardiol 14: 25-30 [3].

Table 1: Rotation of QRS Vector Loop in the Differentiation of RVH from PBLVH.

|

Plane

|

RVH Group |

PBLVH Group

|

| Frontal Plane |

CW – 20

CCW – 1 |

CW – 21

CCW – 2 |

| Horizontal Plane |

CW – 16

Figure of 8 – 5 |

CCW – 23 |

CW, clockwise; CCW, counterclockwise; PBLVH, posterobasal left ventricular hypertrophy; RVH, right ventricular hypertrophy.

Modified from Rao PS, Monarrez CN. (1981) J Electrocardiol,14: 25-30 [3].

In summary, the right ventricular outflow tract, posterobasal portion of the left ventricle and superior portion of the interventricular septum are the last portions of the heart to be depolarized both in normal and ventricular hypertrophy patients. Because of this reason, terminal rightward forces (S waves in V5 and V6) above the 95th percentile for age can be seen both in RVH and PBLVH. With regard to the differentiation of these entities, should there be other voltage criteria for the respective ventricular hypertrophy, the diagnosis of RVH or PBLVH may be made accordingly. In the absence of such voltage criteria, RVH may be diagnosed if the RV2 is greater than 10 mm, SI is greater than 5 mm and the mean horizontal plane QRS vector is between +60 degrees to +200 degrees with a clockwise or figure of 8 loop. A diagnosis of PBLVH may be made if the RV2 is less than 10 mm, SI is less than 5 mm and mean horizontal plane QRS vector is between -10 degrees to -130 degrees with a counterclockwise loop. It was concluded that these criteria are helpful in making appropriate diagnosis of RVH vs. PBLVH [3].

Electrocardiographic Features of Tricuspid Atresia

We have reviewed ECG data on 308 tricuspid atresia patients, including our own 37 cases seen at the Medical College of Georgia [4,5]. The ECG features of tricuspid atresia include right atrial enlargement (RAE), abnormal superior QRS vector (popularly called left axis deviation), left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) and diminished right ventricular (RV) electrical forces. The ECG features of the most common muscular type of tricuspid atresia will be reviewed first, followed by the other types of tricuspid atresia. The vectorcardiographic data will not be reviewed since that modality is no longer used.

Right Atrial Enlargement and PR Interval

RAE is manifested by peaked P waves, in excess of 2.5 mm in amplitude (most usually in leads II and V1), is seen in nearly 75% of patients. P waves with double peaks, sometimes referred to as “P tricuspidale” may occasionally be seen; the terminal component is usually explained to be related to left atrial depolarization, but may be due to increased high to low right atrial conduction time. This prolonged high to low atrial conduction time may also produce a prolonged PR interval.

QRS Complex. Major QRS Vector

A frontal plane QRS vector displaced to the left and superiorly between 0° and -90°– formerly called left axis deviation, but more correctly termed abnormal superior vector – was present in 71% of all tricuspid atresia cases and in 83% of Type I tricuspid atresia patients.

Changing Frontal Plane QRS Vector

Some investigators [6] observed a change in the frontal plane QRS vector from +120° on the first day of life to -15° by two weeks of age, and suggested that this may be related to hemodynamic changes in the postnatal period. Documentation in a larger series of patients is needed to confirm these findings.

Ventricular Hypertrophy

Irrespective of the mean frontal plane vector, voltage criteria for LVH are seen in most cases of tricuspid atresia. The LVH is related to multiple factors: 1. Anatomic nature of the lesion, 2. Hemodynamic changes secondary to the defect, and 3. Unopposed RV electrical forces due to RV hypoplasia. The RV voltages (R waves in leads V4R, V1 and V2 and S waves in V5 and V6) are usually decreased and this finding is likely to be related to a small RV.

ST-T Waves

Abnormalities in ST-T waves suggestive of left ventricular (LV) strain are seen in 50% of tricuspid atresia patients; this pattern is more frequent in patients with high LV voltages.

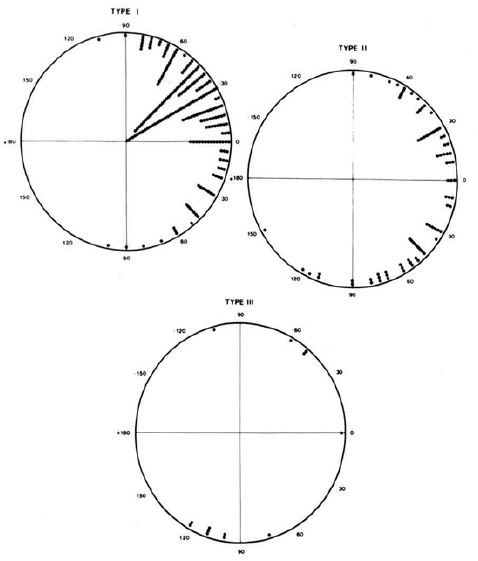

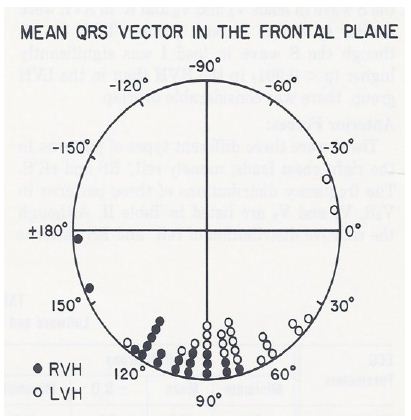

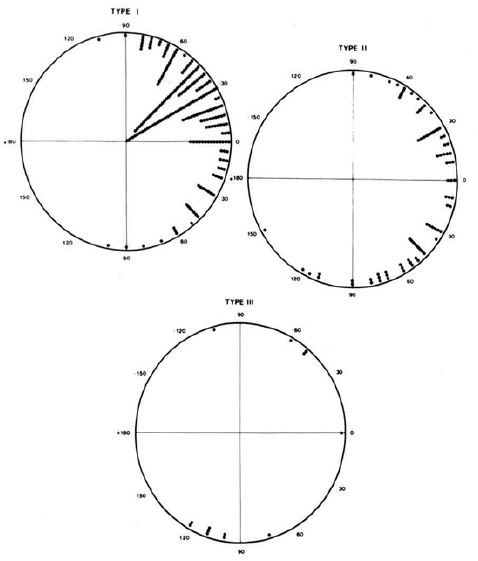

ECG Features Other Types of Tricuspid Atresia

The ECG findings in different types of tricuspid atresia do differ. The frontal plane QRS vectors in 308 patients that we have examined are shown in Figure 6 [4,5]. While 83% of Type I (normally related great arteries) patients have an abnormally superior vector, only 46% of Type II (transposition of the great arteries) patients have such a vector. In Type III, they are even more diverse (Figure 6). While LVH is typical for Type I patients, biventricular hypertrophy on the ECG is likely to be seen in Type II patients. The reported ECG findings in rare forms of tricuspid atresia were reviewed in detail and tabulated in Tables II and III of the second edition of our book on tricuspid atresia [5] and the interested reader is referred to this publication.

Figure 6: QRS vectors in the frontal plane in 308 tricuspid atresia patients are shown separately for Types, I, II and III. The majority of patients with Type I have an abnormally superior vector while only one half of patients with Type II have such a vector. Also, note that most patients with Type III (subtype A) have an inferiorly oriented frontal plane mean vector. Reproduced from Reference [4].

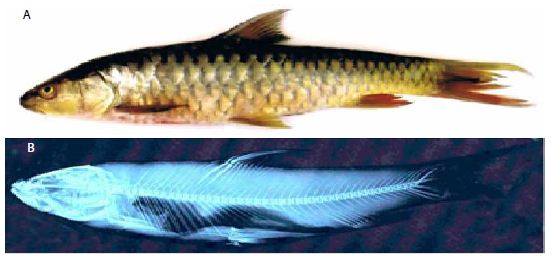

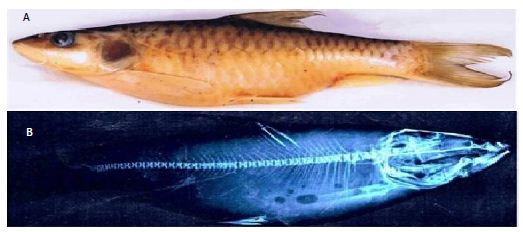

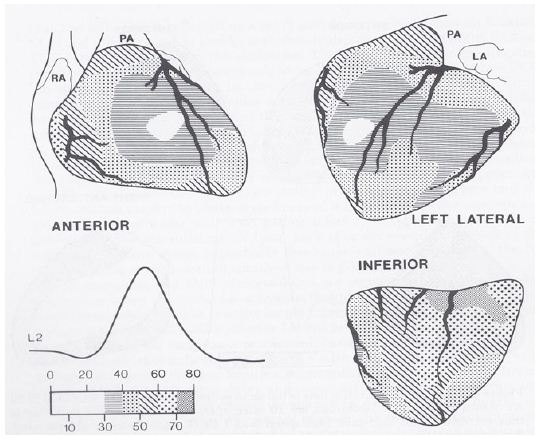

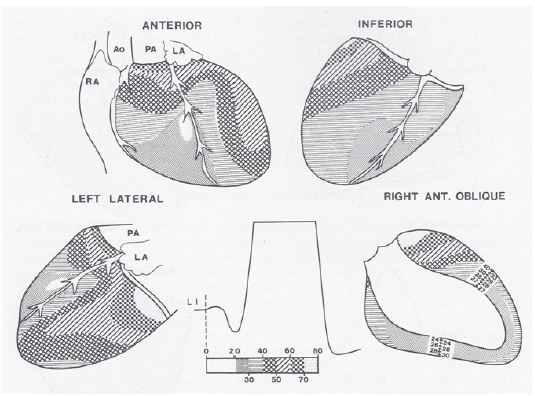

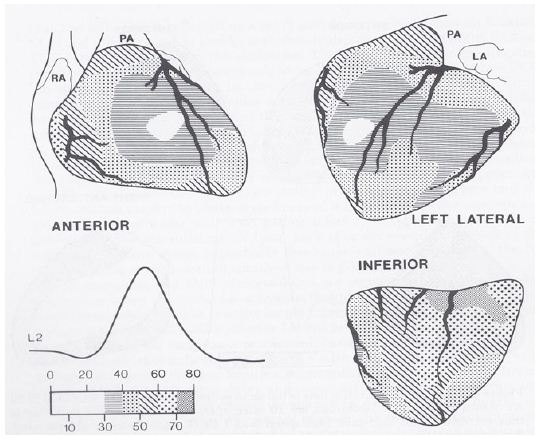

Mechanism of Abnormal Superior Vector (Left Axis Deviation)

A number of hypotheses to explain the abnormal superior vector in tricuspid atresia have been proposed and include large left ventricle, small right ventricle, fibrosis or interruption of the left anterior bundle branch, early origin of the left bundle along with elongated course of the right bundle, and others as reviewed elsewhere [4,5]. In an attempt to define the mechanism of the abnormal superior vector in tricuspid atresia, my colleagues at the Medical College of Georgia and I undertook epicardial mapping and intramural activation studies in three children with tricuspid atresia [4,5,7]. These studies were conducted following approval by the local Institutional Review Board (IRB) and informed consent from the parents. The epicardial ventricular activation sequence from a patient with a normal QRS vector (Figure 7) and that of a patient with tricuspid atresia with an abnormal superior vector (Figure 8) are shown.

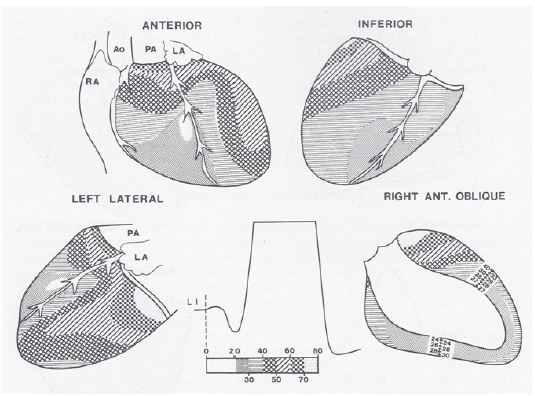

Figure 7: Sequence of ventricular activation in a child with a normal QRS complex. Anterior, left lateral and inferior views are demonstrated. The location of the coronary arteries is superimposed on ventricular activation maps. The isochrones are set 10 msec apart and related to the lead II (L2) of the electrocardiogram. The earliest epicardial breakthrough occurs on the right ventricle at 27 msec and the last epicardial activation occurs at the inferior surface of base of the heart. LA, left atrium; PA, pulmonary artery; RA, right atrium. Reproduced from Reference [5].

Figure 8: Sequence of ventricular activation in a child with tricuspid atresia with an abnormal superior vector. The format is similar to that shown in figure 7, but anterior, inferior, left lateral and right anterior oblique views are shown. The earliest breakthrough occurs in the anterior right ventricle at 18 msec and is similar to normal, but the RV activation is completed within 65 msec – much earlier than normal. The latest epicardial activation area is located on the anteriolateral aspect of left ventricle at the base. Ao, aorta; LI, lead I; LA, left atrium; PA, pulmonary artery; RA, right atrium. Reproduced from Reference [5].

The data are similar in all three children with tricuspid atresia and appear to suggest that the QRS abnormalities of tricuspid atresia are related to: a. right-to-left phase asynchrony of the ventricular activation with early onset and completion of RV activation along with delayed left LV activation, b. early onset of epicardial breakthrough of the inferior LV, c. delayed activation of the superior aspect of the basal portion of the LV, presumably secondary to the asymmetric enlargement of the LV (tower effect), and d. a lack of apposition of the LV wave fronts (delayed activation of the thickened LV) by the early and small RV activation wave fronts [4,5,7]. The geometric and volume conductor effects of a hypoplastic RV and enlarged LV with a more horizontal base to apex orientation of the cardiac axis may also contribute to the expression of an abnormal superior vector. For additional details and discussion, the reader is referred to these publications [4,5,7]. In summary, the ventricular activation data from our studies [4,5,7] suggested that this distinctive abnormal superior vector of the QRS complex in tricuspid atresia is produced by the interaction of multiple factors, the most important of which appear to be right-to-left ventricular disproportion and an asymmetric distribution of the left ventricular mass favoring the superior wall.

Alternating Failure of Mechanical to Electrical Depolarization (AFORMED) Phenomenon

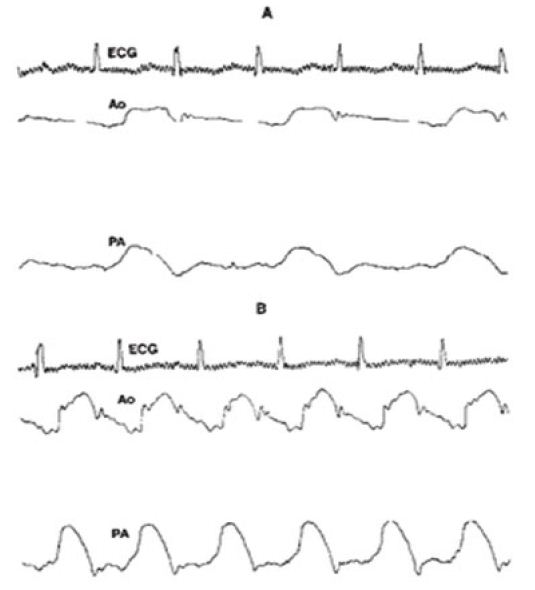

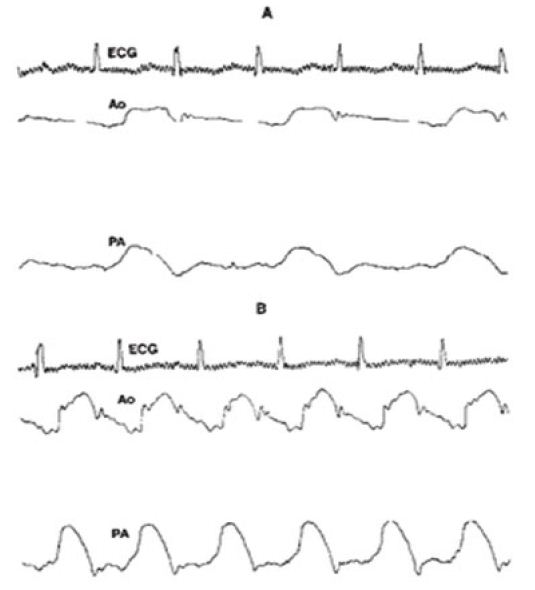

The AFORMED phenomenon was first described in the late 1960s. However, its cause has not been elucidated as of 1983. While studying the mechanism of hypoxic pulmonary hypertension, we observed the AFORMED phenomenon (Figure 9A) in three experimental open-chest dogs [8]. The AFORMED occurred during the tachycardia phase following recovery from cardiac arrest. Administration of intravenous calcium gluconate promptly abolished the AFORMED, but it recurred 10 to 15 minutes later. Administration of lanoctoside-C abolished the AFORMED in 30 minutes with no further recurrence during 2 to 3 hours of observation. However, when rapid acting digitalis preparation (G. strophanthin) was given intravenously, the AFORMED reverted to normal immediately (Figure 9B). We surmised that the lack of availability of calcium to the myofilament may be the cause of the AFORMED because the phenomenon could be abolished by increasing the calcium concentration or by augmenting its influx by cardiac glycosides. We recommended detailed studies of ionic fluxes to further clarify the role of calcium in causing the AFORMED phenomenon [8].

Figure 9: A. Recording of the electrocardiogram (ECG), aortic (Ao) and pulmonary artery (PA) pressures showing that every other ECG complex is not followed by the PA and Ao pulse pressure during the AFORMED phenomenon. B. After administering G. strophanthin all ECG complexes are followed by the Ao and PA pulse traces. Reproduced from Rao PS, Thapar MK. (1983) Am J Cardiol 52: 655 [8].

Racial Variations in Electrocardiograms and Vectorcardiograms between Black and White Children

While it is generally thought that the ECGs of black and white children differ from each other, none of the normal standards in children have taken race into consideration in establishing the norms as of the mid-1980s. Therefore, we examined large groups of black and white children to see if any such differences exist, and if so, to investigate the reason for such differences [9,10]. A total of 244 normal children were studied; 124 were black and 120 were white. 125 were male and 119 were female. 144 measured parameters and 57 computed variables from these subjects were examined. In these studies, the children were divided into age groups of 3-5, 6-10, 11-14, and 15-17 years old. The number of teenagers between 15-17 was small (N=20) and therefore, their data were not analyzed in the initial study [9]. Subsequently, additional teenagers (N = 39) were added; this gave a total of 59 teenagers (28 black and 31 white adolescents between 15 and 19 years old) and were studied [10] in a manner similar to the first study [9]. These data were presented in multiple tables and figures [9,10].

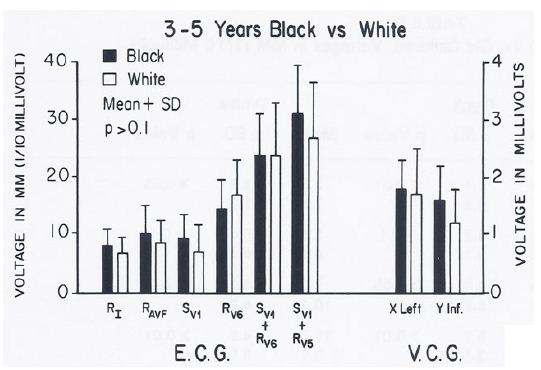

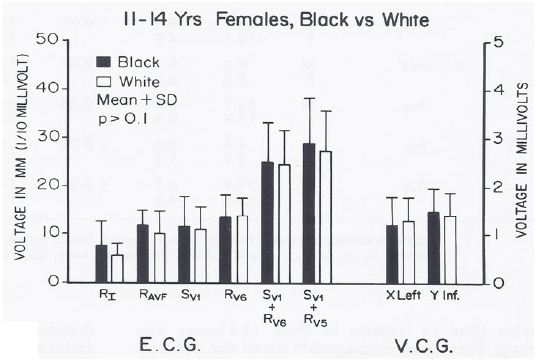

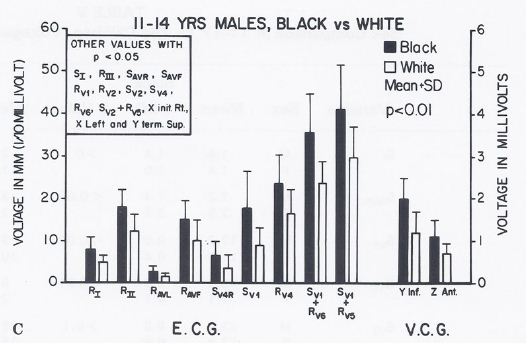

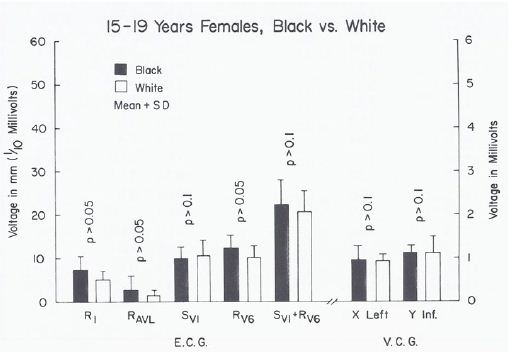

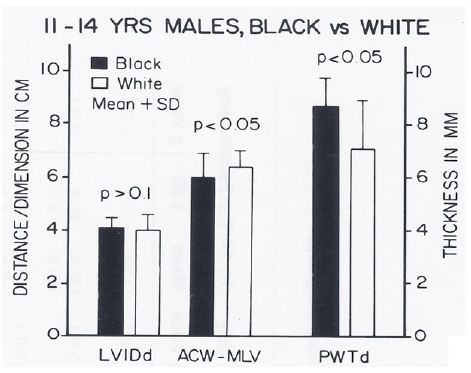

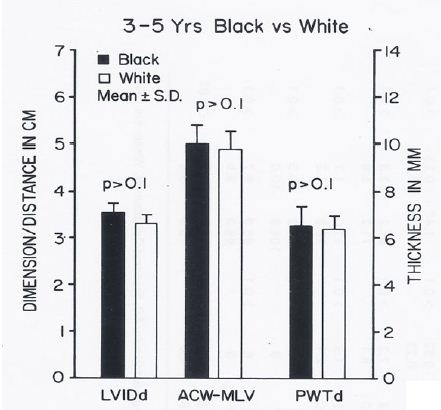

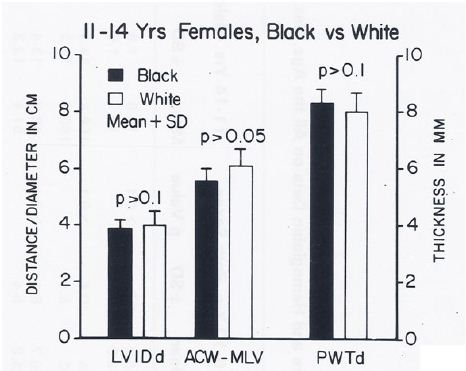

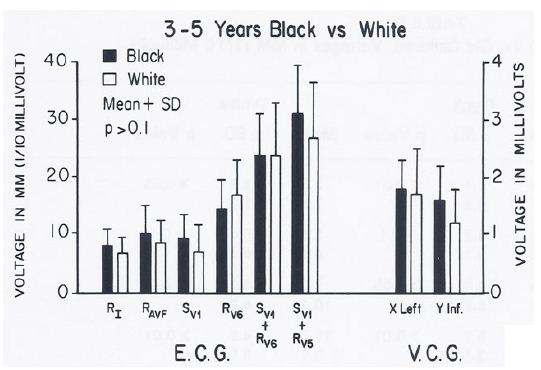

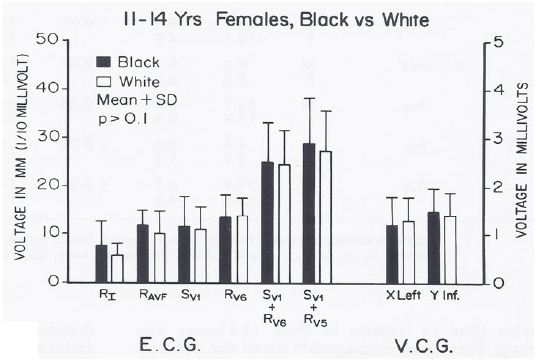

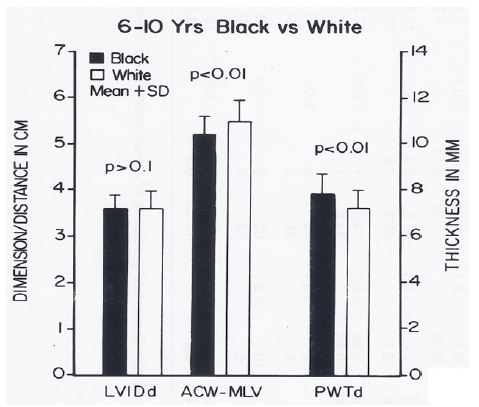

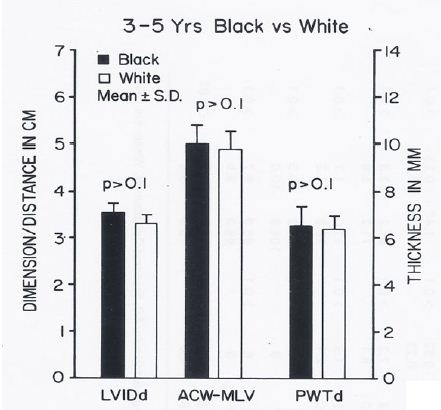

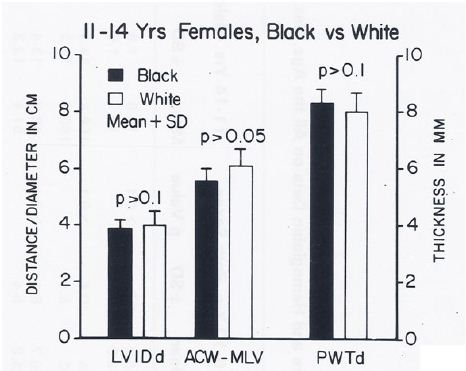

No sex-related or race-related (Figure 10) differences (p > 0.1) in the ECGs/VCGs were detected in the 3- to 5-year-old children. Similarly, no race-related differences (p > 0.1) were seen in the 11- to14-year-old girls (Figure 11).

Figure 10: Bar diagram illustrating the comparison of selected voltage amplitudes of the QRS complex of the electrocardiograms (E.C.G.) and vectorcardiograms (V.C.G.) between 3- to 5-year-old black and white children; filled bars represent black children and unfilled bars represent white children. Note that there were no statistically significant differences (p > 0.1) between the groups. Reproduced from Rao PS, et al. (1984) J Electrocardiol 17: 239-252 [9].

Figure 11: Bar diagram illustrating the comparison of selected voltage amplitudes of the QRS complex of the electrocardiograms (E.C.G.) and vectorcardiograms (V.C.G.) between 11- to 14-year-old black and white females; filled bars represent black girls and unfilled bars represent white girls. Note that there were no statistically significant differences (p > 0.1) between the groups. Reproduced from Rao PS, et al. (1984) J Electrocardiol 17: 239-252 [9].

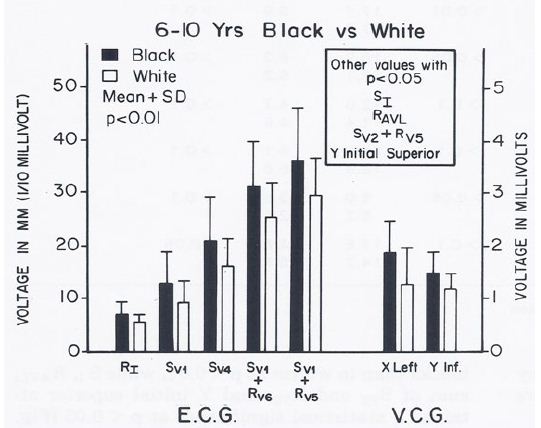

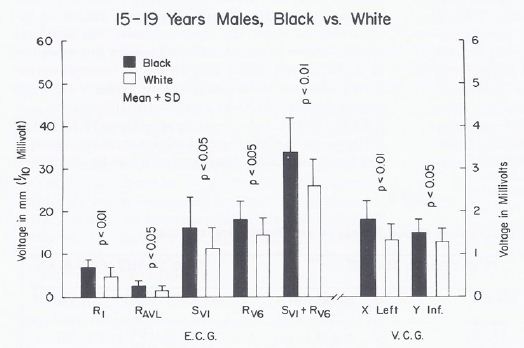

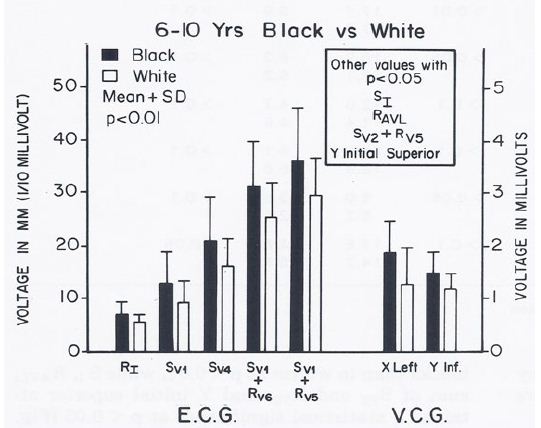

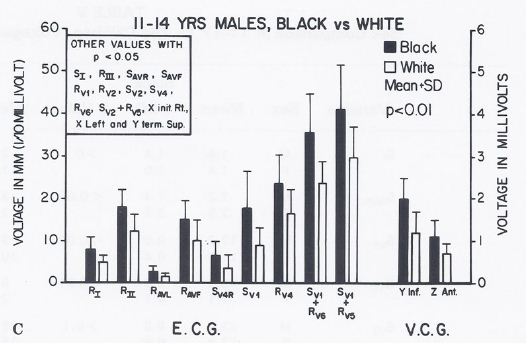

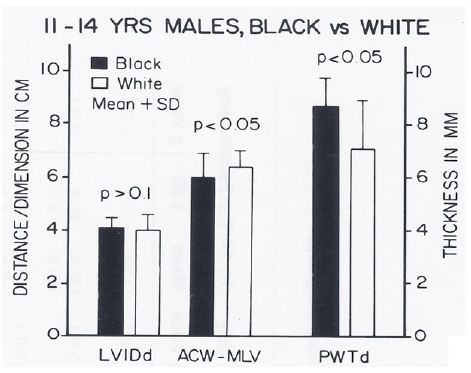

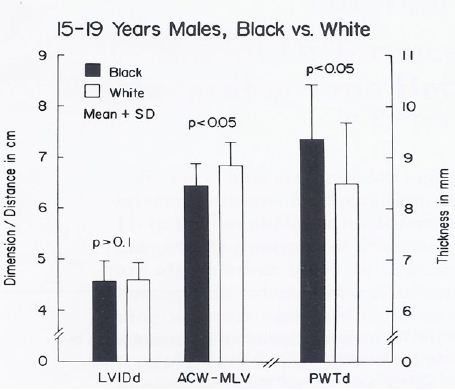

However, higher voltages (p < 0.05 to < 0.01) to the left, posterior and inferior were detected in the ECGs and VCGs of blacks than those of whites in the group of 6- to10-year-old children (Figure 12) and in the 11- to 14-year-old boys (Figure 13). In the 15- to 19-year-old adolescents, the male teenagers had higher (p < 0.05 to 0.001) leftward, inferior and/or posterior voltages than the females; this was true for both black and white adolescents (see Table I of Reference 10 for actual values) [10].

Figure 12: Bar diagram illustrating the comparison of selected voltage amplitudes of the QRS complex of the electrocardiograms (E.C.G.) and vectorcardiograms (V.C.G.) between 6- to 10-year-old black and white children; filled bars represent black children and unfilled bars represent white children. Note that there were statistically significant differences (p < 0.01) between the groups. Other parameters with p values < 0.05 are shown in the insert. Reproduced from Rao PS, et al. (1984) J Electrocardiol 17: 239-252 [9].

Figure 13: Bar diagram illustrating the comparison of selected voltage amplitudes of the QRS complex of the electrocardiograms (E.C.G.) and vectorcardiograms (V.C.G.) between 11- to 14-year-old black and white males; filled bars represent black boys and unfilled bars represent white boys. Note that there were statistically significant differences (p < 0.01) between the groups. Other parameters with p values < 0.05 are shown in the insert. Reproduced from Rao PS, et al. (1984) J Electrocardiol 17: 239-252 [9].

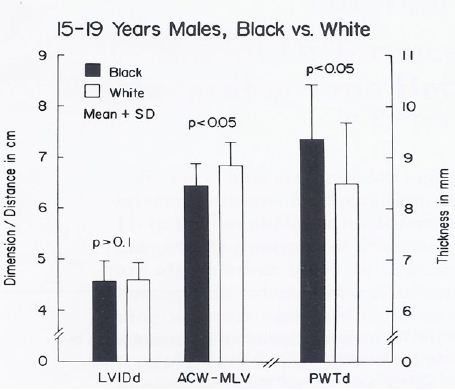

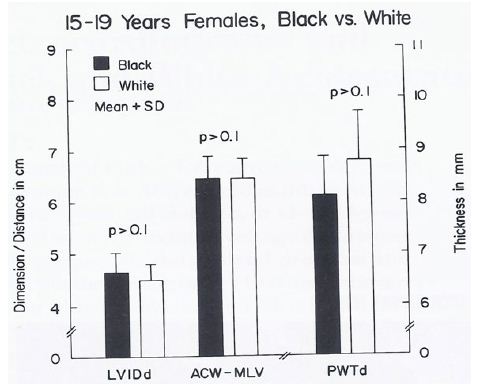

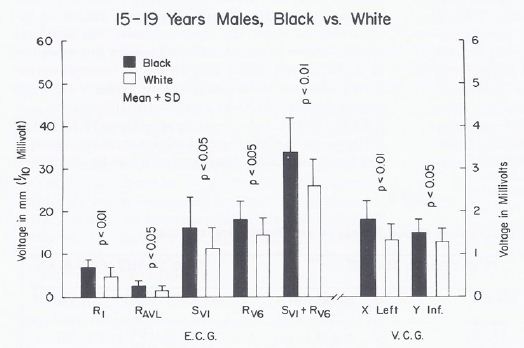

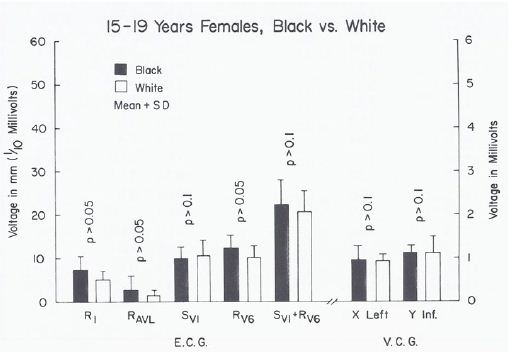

When a racial comparison was made in black 15- to 19-year-olds, the males had higher (p < 0.05 to 0.01) leftward, posterior, inferior voltages than white adolescents (Figure 14) while no such differences (p > 0.05 to > 0.1) were observed in the female subjects (Figure 15).

Figure 14: Bar diagram illustrating a comparison of selected voltage amplitudes of the QRS complex of the electrocardiograms (E.C.G.) and vectorcardiograms (V.C.G.) between 15- to 19-year-old black and white males; filled bars represent black boys and unfilled bars represent white boys. Note that there were statistically significant differences (p < 0.05 to 0.01) between the groups. Reproduced from Rao PS. (1985) J Electrocardiol 18: 309-313 [10].

Figure 15: Bar diagram illustrating a comparison of selected voltage amplitudes of the QRS complex of the electrocardiograms (E.C.G.) and vectorcardiograms (V.C.G.) between 15- to 19-year-old black and white females; filled bars represent black girls and unfilled bars represent white girls. Note that there were no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05 to 0.1) between the groups. Reproduced from Rao PS. (1985) J Electrocardiol 18: 309-313 [10].

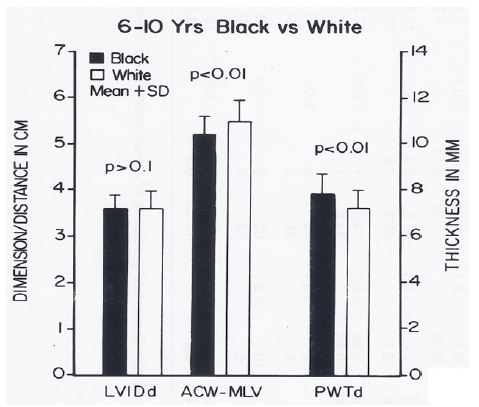

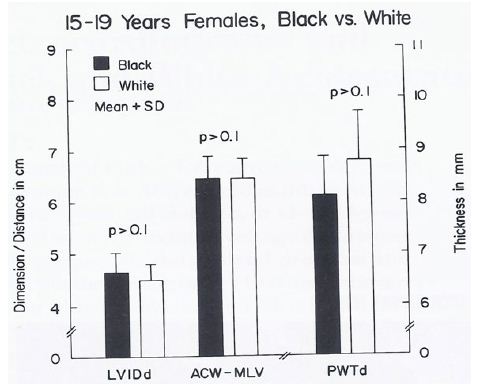

The body surface area, height, weight, AP diameter and circumference of the chest, and systolic and diastolic blood pressures were similar (p > 0.1) in black and white children for all age groups. The hemoglobin and hematocrit values were lower (p < 0.05) in black than in white children. Yet, this difference was seen in all age-sex subgroups, indicating that hemoglobin/hematocrit levels are unlikely to explain the ECG-VCG differences. The left ventricular end-diastolic dimensions were similar (p > 0.1). But, on echocardiographic measurement, the left ventricular posterior wall in diastole was thicker (p < 0.05 to < 0.01) and the distance between the anterior chest wall to mid-left ventricle was shorter (p < 0.05 to < 0.01) in black than in white children in the age-sex subgroups in which the ECG-VCG differences were noted (Figures 16 through 18) while these differences were not seen in the groups in which the ECG differences were not observed (Figures 19 through 21).

Figure 16: Bar diagram comparing the left ventricular internal dimension in diastole (LVIDd), anterior chest wall (ACW) to mid-left ventricular (MLV) distance and left ventricular posterior wall thickness in diastole (PWTd) in 6- to 10-year-old black and white children; filled bars represent black children and unfilled bars represent white children. Note that the LVIDd is similar (p> 0.1) while the ACW to MLV distance is shorter (p < 0.01) and PWTd thicker (p < 0.01) in black than in white children. Reproduced from Rao PS, et al. (1984) J Electrocardiol 17: 239-252 [9].

Figure 17: Bar diagram comparing the left ventricular internal dimension in diastole (LVIDd), anterior chest wall (ACW) to mid-left ventricular (MLV) distance and left ventricular posterior wall thickness in diastole (PWTd) in 11- to 14-year-old black and white male children; filled bars represent black children and unfilled bars represent white children. Note that the LVIDd is similar (p> 0.1) while the ACW to MLV distance is shorter (p < 0.05) and PWTd thicker (p < 0.05) in black than in white children. Reproduced from Rao PS, et al. (1984) J Electrocardiol 17: 239-252 [9].

Figure 18: Bar diagram comparing the left ventricular internal dimension in diastole (LVIDd), anterior chest wall (ACW) to mid-left ventricular (MLV) distance and left ventricular posterior wall thickness in diastole (PWTd) in 15- to 19-year-old black and white male teenagers; filled bars represent black teenagers and unfilled bars represent white teenagers. Note that the LVIDd is similar (p> 0.1) while the ACW to MLV distance is shorter (p < 0.05) and PWTd thicker (p < 0.05) in black than in white teenagers. Rao PS. (1985) J Electrocardiol 18: 309-313 [10].

Figure 19: Bar diagram comparing the left ventricular internal dimension in diastole (LVIDd), anterior chest wall (ACW) to mid-left ventricular (MLV) distance and left ventricular posterior wall thickness in diastole (PWTd) in 3- to 5-year-old black and white children; filled bars represent black children and unfilled bars represent white children. Note that the LVIDd, ACW to MLV distance and PWTd are similar (p > 0.1) in both groups. Reproduced from Rao PS, et al. (1984) J Electrocardiol 17: 239-252 [9].

Figure 20: Bar diagram comparing the left ventricular internal dimension in diastole (LVIDd), anterior chest wall (ACW) to mid-left ventricular (MLV) distance and left ventricular posterior wall thickness in diastole (PWTd) in 11- to 14-year-old black and white female children; filled bars represent black children and unfilled bars represent white children. Note that the LVIDd, ACW to MLV distance and PWTd are similar (p > 0.05 to > 0.1) in both groups. Reproduced from Rao PS, et al. (1984) J Electrocardiol 17: 239-252 [9].

Figure 21: Bar diagram comparing the left ventricular internal dimension in diastole (LVIDd), anterior chest wall (ACW) to mid-left ventricular (MLV) distance and left ventricular posterior wall thickness in diastole (PWTd) in 15- to 19-year-old black and white female teenagers; filled bars represent black teenagers and unfilled bars represent white teenagers. Note that the LVIDd, ACW to MLV distance and PWTd are similar (p > 0.1) in both groups. Reproduced from Rao PS. (1985) J Electrocardiol 18: 309-313 [10].

In the discussion following the presentation of the results, a review of the sexual and racial differences in the ECGs was presented. The sex-based differences (higher precordial voltages in males than females in children above 11 years of age) that we found in our study were similar to those observed by other workers as reviewed in our papers [9,10]. With regard to racial differences, higher leftward, posterior and inferior voltages were found in black children than in white children; these began to appear in 6- to 10-year-olds and became more pronounced during adolescence. These differences during adolescence were largely confined to the male subjects. Some earlier studies were in line with our observations, while other studies could not document such differences as reviewed in our papers [9,10].

In summary, the causes for the racial differences had not been adequately investigated prior to our study. Our thorough review indicated no differences in the specialized ventricular conduction system, ventricular activation patterns, duration of QRS complex or size of the left ventricle. Similarly, the body surface area, height, weight, AP diameter and circumference of the chest, and the systolic and diastolic blood pressures did not seem to vary in such a way that might explain the differences. The lower hemoglobin levels that we found in black children may, to some degree, explain the racial difference, but this difference was small, and more importantly, the lower hemoglobin levels were found in all age groups, including those groups in whom no ECG/VCG differences were observed, making hemoglobin an unlikely causative factor. In black children in the groups in which ECG-VCG differences were seen, a thicker left ventricular posterior wall and shorter anterior chest wall to mid-LV distance were observed than in white children in the same groups, and these factors are likely to be responsible for this difference. Based on these observations, we recommended that separate normal standards are needed for males and females beyond 11 years of age and for black and white children beyond six years of age [9,10].

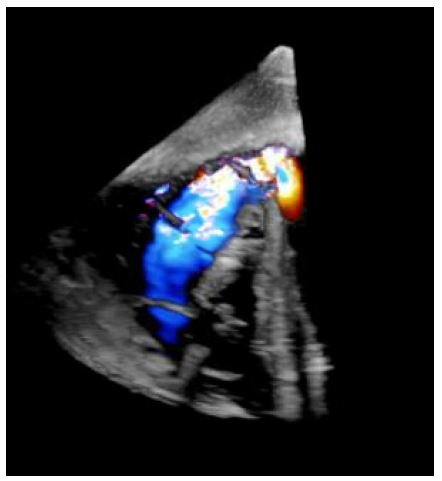

Congestive Cardiomyopathy Due to Chronic Tachycardia (Resolution with Medications)

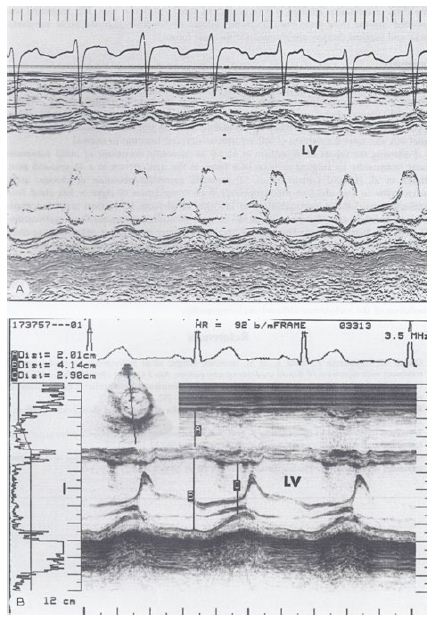

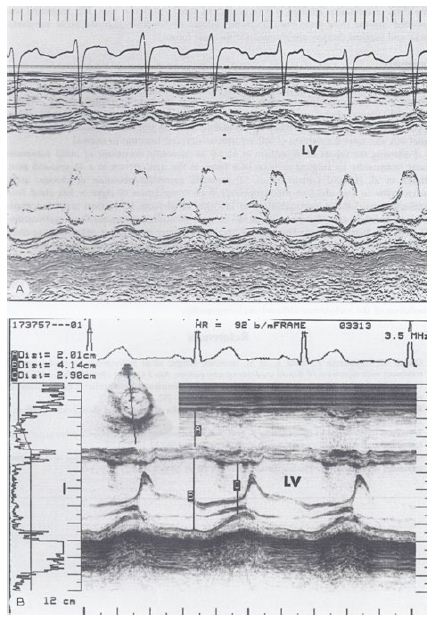

As of the mid-1980s, the importance of treatment of tachycardia by surgical or catheter-based ablation was emphasized to prevent arrhythmia-induced cardiomyopathy. We hypothesized that the reduction of the ventricular rate to normal by drug therapy would result in the regression of arrhythmia-induced cardiomyopathy. To support this hypothesis, we presented the case of a three-year-old child who developed arrhythmia-induced cardiomyopathy (Figure 22A) and who improved (Figure 22B) with drug therapy [11]. Treatment with medications (Digoxin and Verapamil) resulted in the immediate relief of symptoms, and was followed by a gradual improvement in cardiac size and function (Table 2) with a subsequent return of normal cardiac size and function (Figure 22).

Table 2: Cardiac Rate, Size and Function Prior to and Following Drug Treatment.

|

At initial presentation

|

After conversion |

One-year follow-up |

Two-year follow-up |

Last follow-up (5.5 years)

|

| Ventricular rate, ECG |

200

|

67 |

85 |

96 |

69

|

| CT ratio, X-ray |

0.6

|

0.58 |

0.51 |

0.45 |

0.43

|

| LVEDD, mm, echo |

48

|

50 |

41 |

40 |

41

|

| LVEDD/m2, mm, echo |

87

|

91 |

65 |

53 |

54

|

| LV shortening fraction |

13

|

24 |

24 |

32 |

29

|

| PEP /LVET ratio |

0.74

|

0.51 |

0.39 |

0.24 |

0.24

|

| LA/Ao ratio |

1.5

|

1.4 |

1.3 |

1.0 |

1.1

|

Ao, aorta; CT, cardiothoracic; echo, echocardiogram; ECG, electrocardiogram; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension; LVET, left ventricular ejection time; PEP, pre-ejection period.

Reproduced from Rao PS, Najjar HN. (1987) International J Cardiol 17: 216-220 [11].

Figure 22: A. M-mode echocardiogram of a 3-year-old child who developed arrhythmia-induced cardiomyopathy; note the markedly dilated left ventricle (LV) with poor function (calculated shortening fraction was 13%). B. M-mode echocardiogram of the same patient following successful drug therapy (5.5 years later); note the normal-sized LV with normal function (calculated shortening fraction was 29%). Reproduced from Rao PS, Najjar HN. (1987) International J Cardiol 17: 216-220 [11].

This case demonstrated that reducing the ventricular rate by medication may result in resolving arrhythmia-induced cardiomyopathy and that the surgical excision or catheter ablation of the atrial automatic focus is not necessary in all cases, at least as of the late 1980s. However, it should be noted that enormous advances in pediatric electrophysiology and catheter-based ablation techniques have taken place since the time of our publication [11], and catheter-based ablation of the inciting focus may be an excellent choice at the present time, once the acute symptoms have been controlled by drug therapy.

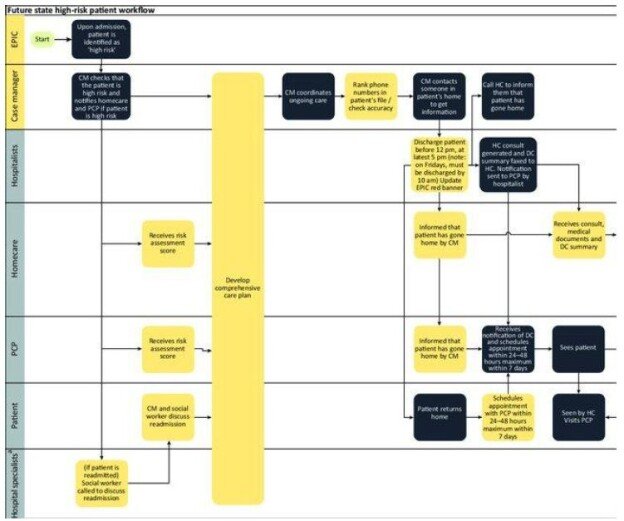

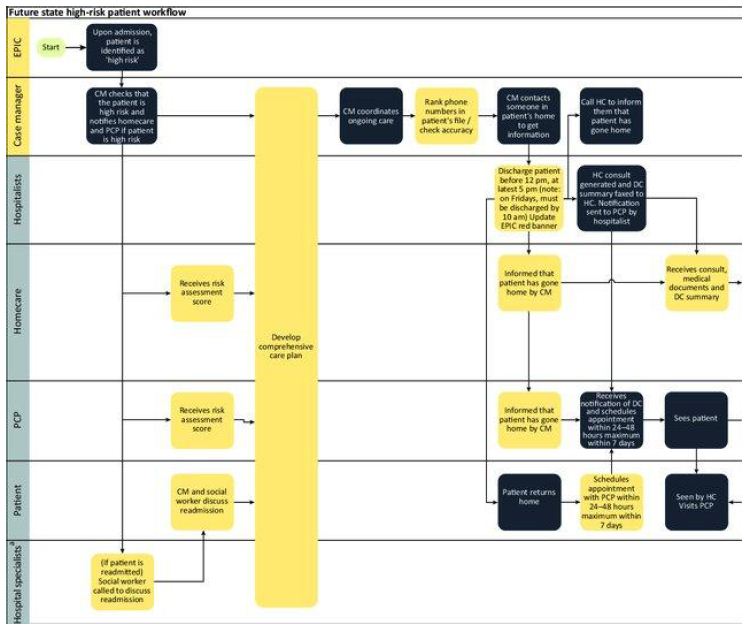

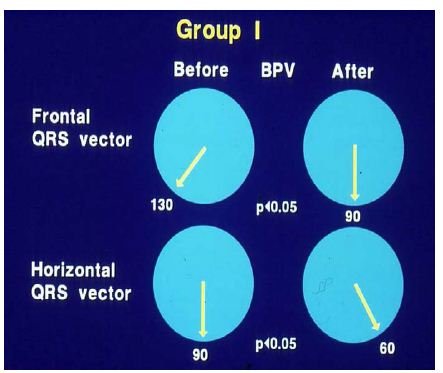

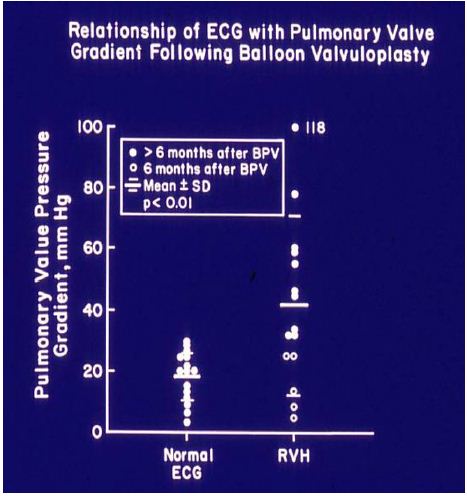

Electrocardiographic Changes Following Balloon Valvuloplasty for Pulmonary Stenosis

While the evaluation of the follow-up results of balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty by echo-Doppler have been found useful, there was sparse data on the utility of the ECG in the assessment of the results of balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty as of the mid-1980s. Therefore, we sought to examine ECG changes subsequent to balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty for pulmonary valve stenosis and to scrutinize whether ECG changes reflect an improvement in the pressure gradient across the pulmonary valve at follow-up [12].

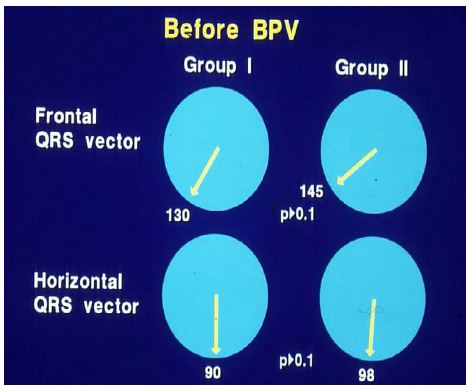

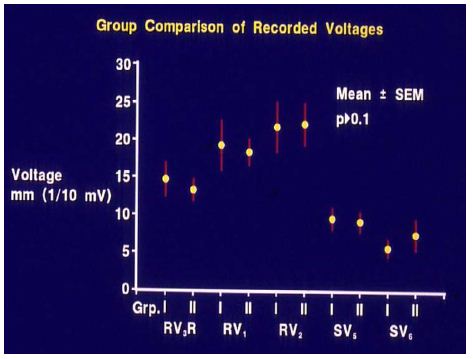

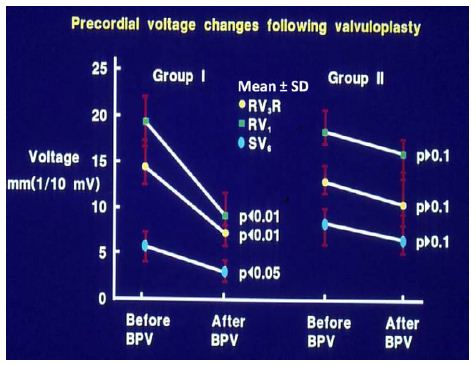

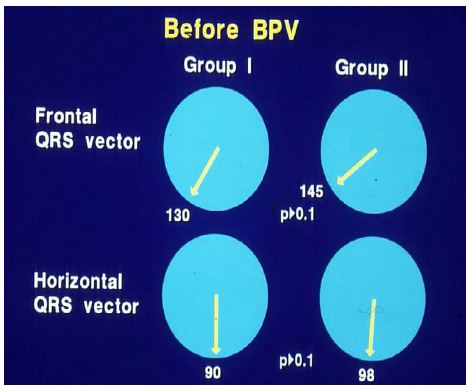

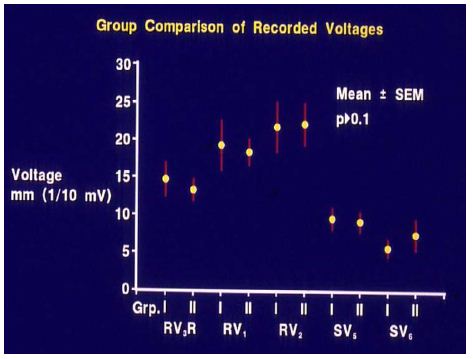

Of the 41 patients – aged seven days to 20 years – who had balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty, 35 patients had ECGs available for review and comparison both prior to and at three to 34 months (mean 11 months) follow-up. On the basis of cardiac catheterization and echo-Doppler systolic pressure gradients across the pulmonary valve at follow-up, the study subjects were divided into two groups: group I, with good results (N = 30) and group II, with poor results (N = 5). There was no difference (p > 0.1) in any ECG parameters (Figures 23 and 24) between the groups prior to balloon valvuloplasty [12].

Figure 23: Plots of mean QRS vectors (axis) in the frontal (top) and horizontal (bottom) planes in group I (with good results) (left circles) and group II (with poor results) (right circles) prior to balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty (BPV) are shown. Note that no significant (p > 0.1) difference was seen between groups I and II. Reproduced from reference [13].

Figure 24: Anterior (R waves in leads V3R, V1 and V2) and terminal rightward (S waves in leads V5 and V6) voltages in the electrocardiograms prior to balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty are compared between group I (with good results) and group II (with poor results). Mean and standard error of mean (SEM) are shown. Note that no significant (p > 0.1) difference is shown between groups I and II. Reproduced from reference [13].

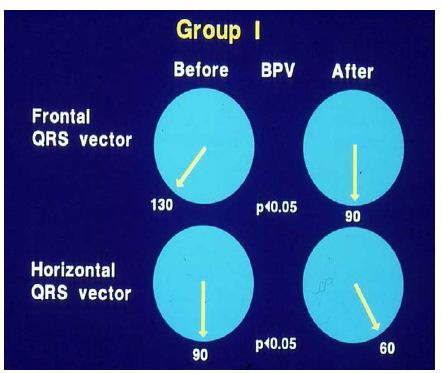

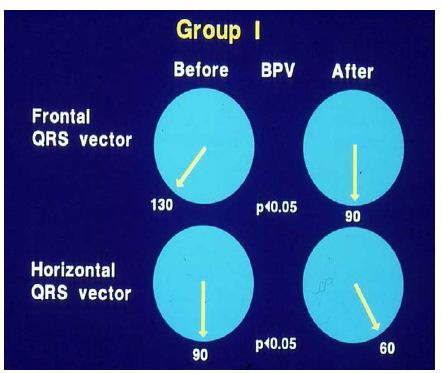

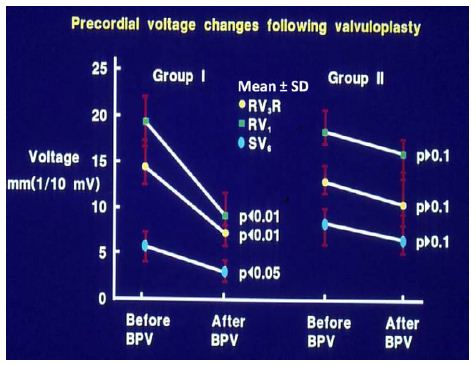

In group I (with good results), the frontal plane mean QRS vector moved toward the left from 127 ± 25° to 81 ± 47°, as did the horizontal plane mean QRS vector, which moved from 88 ± 36° to 57 ± 31° (Figure 25) at follow-up; this change is statistically significant (< 0.05). The anterior (R waves in leads V3R, V1 and V2) and terminal rightward (S waves in lead V5 and V6) electrical forces decreased (Figures 26, left panel). However, there was no change (p > 0.1) in the frontal (145 ± 27° vs. 145 ± 27°) and horizontal (98 ± 19° vs. 112 ± 29°) vectors and in precordial voltages (Figures 26, right panel) in group II (with poor results).

Figure 25: Plots of mean QRS vectors (axis) in the frontal (top) and horizontal (bottom) planes in group I (with good results) prior to balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty (BPV) (left circles) and at follow-up (right circles) are shown. Note the significant (p < 0.05) improvement at follow-up. Reproduced from reference [13].

Figure 26: Precordial ECG voltages (R waves in leads V3R and V1 and S waves in V6) prior to and at follow-up after balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty (BPV) in group I (with good results) (left panel) and group II (with poor results) (right panel) are depicted. The mean and standard deviation (SD) are shown. Note the significant (p < 0.05 to 0.01) decrease in the voltages in group I while there was no significant (p > 0.1) change in group II. Reproduced from reference [13].

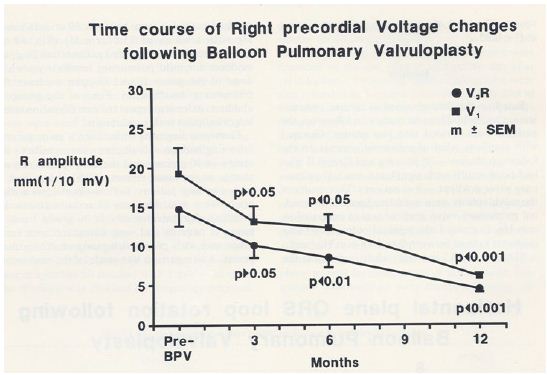

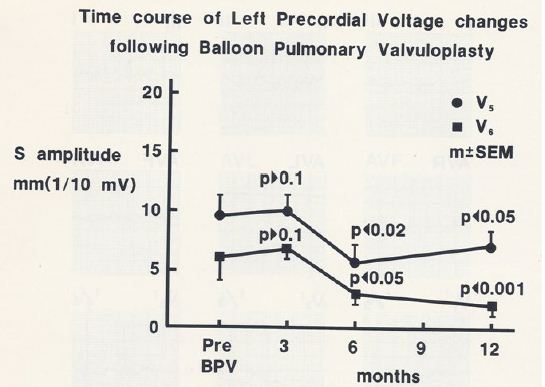

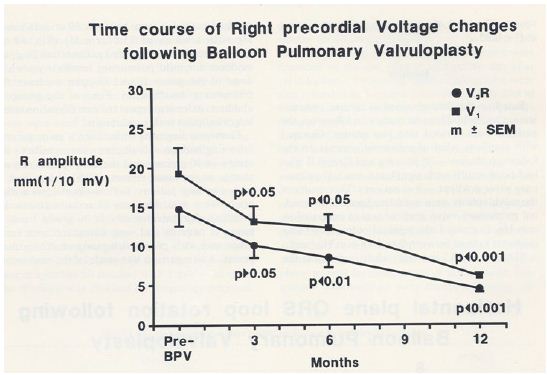

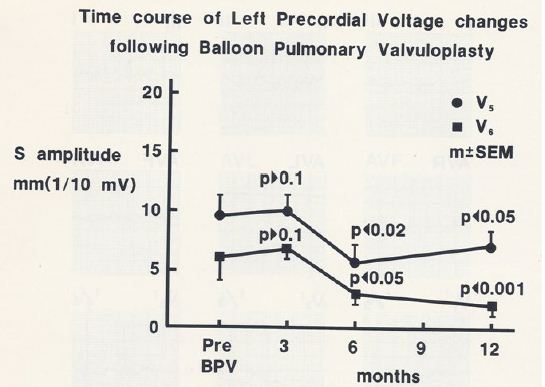

When the time courses of the ECG voltage changes in group I were examined, a gradual improvement was noted; at three-month follow-up, there was no statistically significant decrease (p > 0.05), but at six and 12 months, a significant (p< 0.05 to 0.001) decrease in the voltages was observed (Figures 27 and 28).

Figure 27: Precordial ECG voltages (R waves in leads V3R [circles] and V1 [squares]) prior to and at three, six, and 12 months following balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty (BPV) in group I patients (with good results). Note that a gradual improvement was shown; at three month follow-up, there was no statistically significant decrease (p > 0.05), but at six and 12 months, a significant (p< 0.05 to 0.001) decrease was observed. The mean and standard error of mean (SEM) are shown. Reproduced from Rao PS, Solymar L. (1988) J Interventional Cardiol 1: 189-197 [12].

Figure 28: Precordial ECG voltages (S waves in leads V5 [circles] and V6 [squares]) prior to and at three, six, and 12 months following balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty (BPV) in group I patients (with good results). Note that a gradual improvement was shown; at three month follow-up, there was no statistically significant decrease (p > 0.05), but at six and 12 months, a significant (p< 0.05 to 0.001) decrease was observed. The mean and standard error of mean (SEM) are shown. Reproduced from Rao PS, Solymar L. (1988) J Interventional Cardiol 1: 189-197 [12].

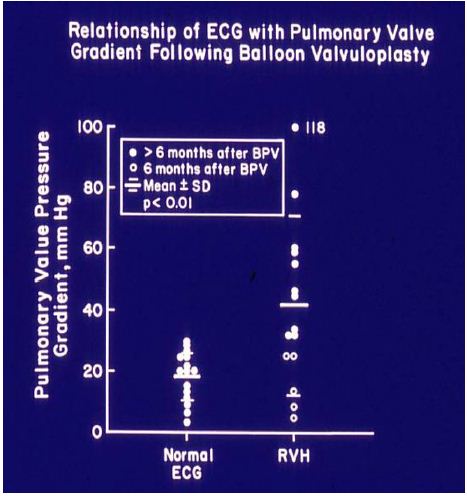

After concluding that the ECG gets better after successful balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty, we sought to determine whether the post valvuloplasty ECG reflects a residual valve gradient at follow-up. We analyzed thirty pairs of ECGs and trans-pulmonary valve systolic pressure gradients acquired within 24 hours of each other. The ECGs were interpreted as normal or right ventricular hypertrophy on the basis of standard criteria [12]. In fifteen patients with normal ECGs, the pulmonary valve peak systolic pressure gradients were 18.3 ± 8.2 mmHg (with a range of 4 to 30 mmHg) (Figures 29): these simultaneous ECGs/pulmonary valve gradients were secured seven to 28 months (12.0 ± 5.5 mo) after the balloon procedure. Five ECGs obtained within 6 months of balloon valvuloplasty, though improved, still showed RVH even though the gradients were low (15.2 ± 9.4; range 5 to 25 mmHg). The final 10 ECGs showed RVH and had high (55.8 ± 26.4; range 32 to 118 mmHg) residual gradients (Figures 29) at follow-up after 10 ± 5 months. These data suggest that 1. A normal ECG implies a minimal residual pulmonary valve gradient, 2. RVH indicates a significant residual gradient, and 3. Patients whose ECGs are recorded earlier than six months after balloon valvuloplasty may not have had time for the complete resolution of RVH, despite reduced gradients.

Figure 29: The relationship of residual pulmonary valve gradients at follow-up after balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty (BPV) and electrocardiogram (ECG) is plotted. Note that a normal ECG is found in patients with minimal residual pulmonary valve gradients (left panel) while RVH indicates a significant residual gradient, or that the ECGs were recorded earlier than six months after BPV. The mean and standard deviation (SD) are shown. Filled circles – ECGs recorded six months after BPV. Open circles – ECGs recorded prior to six months after BPV. ECGs recorded prior to six months after BPV exhibited RVH, despite reduced gradients; this may in part be related to not yet having had a chance for the complete resolution of RVH. Reproduced from reference [13].

On the basis of these data, we concluded that the ECG is a good indicator of the improvement in gradients following balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty, but reduced valve gradients may not be reflected by the ECG until six months after balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty [12,13].

The Role of the ECG in Delineating Atrial and Ventricular Situs in Patients with Dextrocardia and Heterotaxy Syndromes

Early on we utilized the ECG to delineate atrial and ventricular situs in patients with asplenia/polysplenia syndromes and dextrocardia [14,15]. Atrial and ventricular situs determination was appraised.

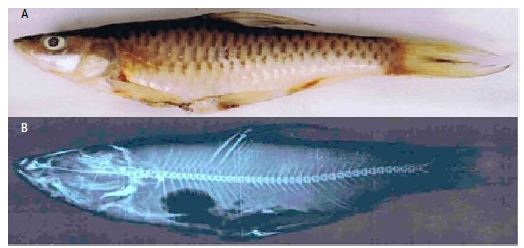

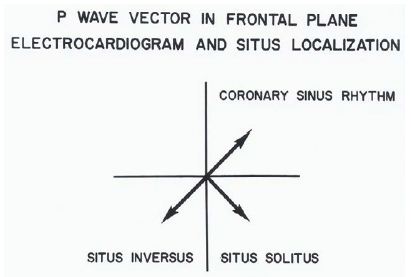

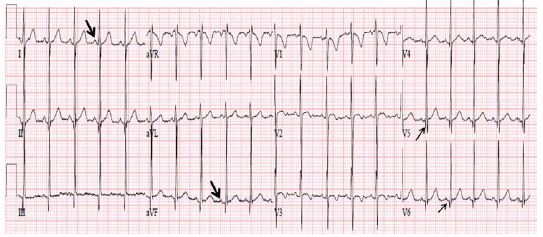

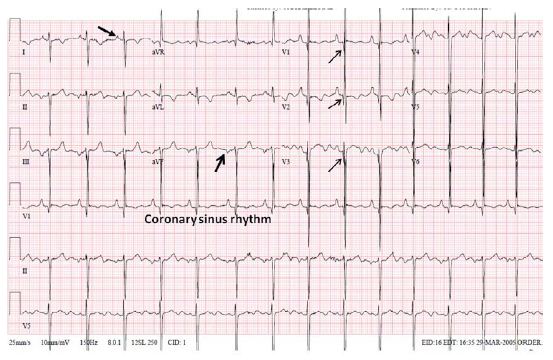

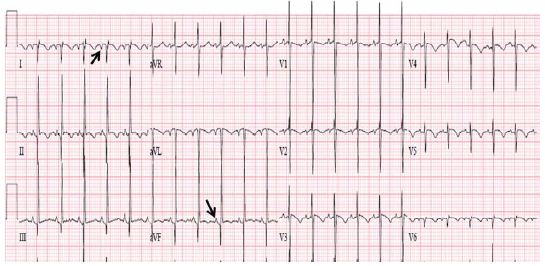

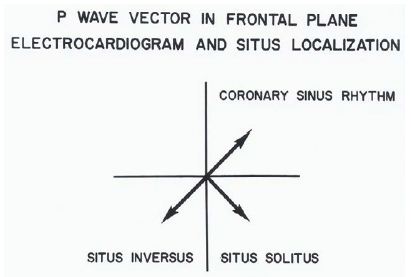

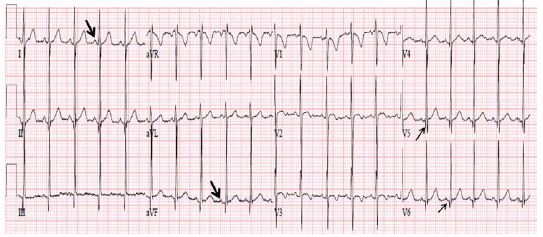

Atrial Situs

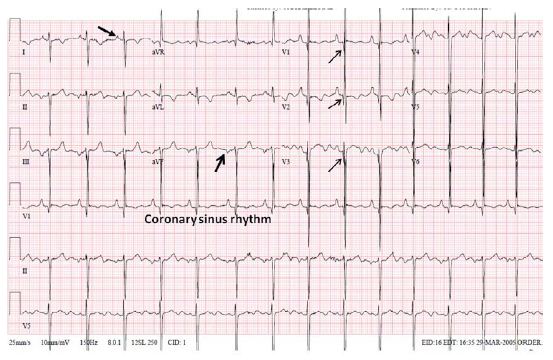

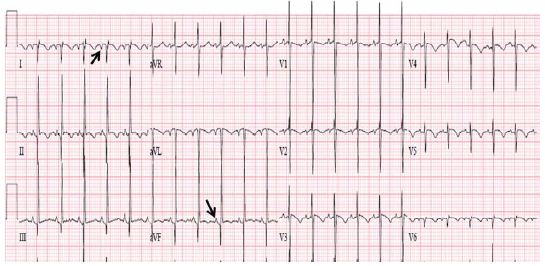

There are multiple ways in which the atrial situs may be determined, and the ECG is one of the least invasive and easy methods to make such a determination [14-18]. Because the sinoatrial node is normally located at the superior vena cava (SVC)-right atrial (RA) junction, the atrial depolarization traverses leftward and inferiorly and produces “P” waves with a vector (axis) of +45° in the frontal plane (Figure 30). This results in upright P waves in leads I and AVF (Figure 31). With atrial inversion (situs inversus) the P vector is around +135° (Figure 30) with an inverted P wave in lead I and an upright P wave in lead AVF (Figure 32). If the P vector is -45° with upright P waves in lead I and inverted P waves in lead AVF (Figures 30 and 33), it may be called coronary sinus rhythm (or low atrial rhythm), and such a P vector is not helpful in determining atrial situs. However, coronary sinus rhythm is frequently associated with systemic venous anomalies (persistent left superior vena cava and infrahepatic interruption of the inferior vena cava) which are frequently seen with asplenia/polysplenia syndromes.

Figure 30: The location of the P vector (axis) in the frontal plane is shown for situs solitus (+450) and situs inversus (+1350). A P vector between 00 and -900 is called coronary sinus rhythm and is not helpful in atrial situs assignment. Reproduced from Rao PS, Leonard T. (1976) Cardiology Digest 11(3): 14-22 [14].

Figure 31: ECG demonstrating a normal P vector (+450) with positive P waves in leads I and AVF (arrows in leads I and AVF) suggesting atrial situs solitus. Also, note that there are no Q waves in leads V1 and V2 and Q waves are present in leads V5 and V6 (arrows in V5 and V6), indicating a normal left-to-right ventricular relationship. Reproduced from Reference [17].

Figure 32: ECG demonstrating an abnormal P vector (+1350) with a negative P wave in lead I and a positive P wave in lead AVF (arrows in leads I and AVF) suggesting atrial situs inversus. Reproduced from Reference [17].

Figure 33: ECG demonstrating an abnormal P vector (-450) with positive P waves in lead I and negative P waves in lead AVF (arrows in leads I and AVF) suggesting coronary sinus rhythm; this pattern is not useful in assigning atrial situs. Also note the Q waves in leads V1, V2 and V3 (arrows in V1 V2 and V3), and that there are no Q waves in leads V5 and V6, indicating ventricular inversion. Modified from Reference [17].

Ventricular Situs

The ECG may also be helpful in determining the ventricular situs. While it is generally thought that the qRs pattern of the QRS complex is seen over the left ventricle and the rS pattern over the right ventricle, this concept is not necessarily correct because most dextrocardia and heterotaxy syndrome patients have complex congenital heart disease causing right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH), or they may have a single ventricle. Therefore, it is frequently difficult to distinguish RV (rS pattern) from LV (qRs pattern) of QRS complexes. However, an initial QRS vector may be more helpful. The depolarization of the ventricular septum takes place from both the right and left sides of the septum, with slightly earlier depolarization on the left than on the right side. The sum total initial ventricular forces are directed to the right, anterior and slightly superiorly, resulting in Q waves in leads V5 and V6, no Q waves in leads V1 and V2 , and a small Q wave in lead AVF (Figure 31). In patients with ventricular inversion, the conduction system is also inverted and the initial QRS vector is directed to the left and posteriorly. Consequently, there will be Q waves in leads V1 and V2, no Q waves in leads V5 and V6 (Figure 33), and may have deep Q waves in leads II, III and AVF. These principles are equally applicable, irrespective of the heart’s position in the chest (levocardia, mesocardia or dextrocardia). While this type of analysis appears simple and logical, sometimes it may not be reliable because of variable degrees of rotation and hypertrophy of the ventricles.

The concepts, detailed in our early publications [13-15], appear to have stood the test of time, and we were thus able to reaffirm them in our recent publications [16-19].

Review of Arrhythmias

In Conn’s Current Therapy [20,21], we presented a detailed review of the identification and management of arrhythmias in the pediatric patient in the 1980s. The presentation included descriptions of normal rhythms (sinus arrhythmia, wandering atrial pacemaker, sinus tachycardia, sinus bradycardia), premature contractions (premature atrial beats, premature junctional contractions, premature ventricular beats), supraventricular (paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia [SVT], atrial flutter, atrial fibrillation, junctional tachycardia, automatic atrial tachycardia) and ventricular (ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation and “torsade de point”) tachycardias, sick sinus syndrome, and heart blocks (first-degree heart block, second-degree heart block [Wenchebach (Mobitz Type I) and fixed (Mobitz Type II)] and third-degree heart block [complete heart block]), and their diagnosis and management. An alphabetical list of drugs commonly used in the management of pediatric patients with heart disease, with particular attention to the drugs used in the management of arrhythmias in infants and children, was included in these publications [20,21]. The material was presented to many groups of pediatric cardiology fellows, pediatric residents and pediatricians. In addition, examples of the arrhythmia ECG tracings were published in our book, Pediatric Cardiology, Medical Examination Review [22], in questions 1115 through 1167 and 1197 to 1200; the interested reader may review these.

Summary and Conclusions

A number of studies were conducted investigating the utility of ECGs in the assessment of clinical issues in children. Study of Frank and McFee vector-cardiograms in the adolescent established normal vectorcardiographic values in adolescents. Recording intra-cavitary electrocardiograms along with pressures in a patient with Ebstein’s anomaly of the left atrio-ventricular valve in CCTGA helped establish the diagnosis in a manner similar to Ebstein’s anomaly in children with normally related ventricles and great arteries. Investigation to differentiate right ventricular hypertrophy from posterobasal left ventricular hypertrophy resulted in developing criteria (RVH – RV2 greater than 10 mm, SI greater than 5 mm, and the mean horizontal plane QRS vector between +60 degrees to +200 degrees with a clockwise or figure of 8 loop; PBLVH – RV2 less than 10 mm, SI less than 5 mm and mean horizontal plane QRS vector between -10 degrees to -130 degrees with a counterclockwise loop) to distinguish them from each other. A detailed description of electrocardiographic features of tricuspid atresia was presented. The mechanism of abnormal superior vector (left axis deviation) in tricuspid atresia was studied with the resulting conclusion that distinctive abnormal superior vector of the QRS complex is produced by the interaction of multiple factors, the most important of which appear to be right-to-left ventricular disproportion and an asymmetric distribution of the left ventricular mass favoring the superior wall. The mechanism of AFORMED phenomenon was studied in experimental animal model with the conclusion that the lack of availability of calcium to the myofilament may be the cause of the AFORMED phenomenon. We have investigated racial variations in ECGs and VCGs between black and white children and these studies demonstrated: 1. Gender-based differences with higher precordial voltages in males than females in children above 11 years of age, 2. Racial differences with higher leftward, posterior and inferior voltages in black children than in white children; these began to appear in 6- to 10-year-olds and became more pronounced during adolescence. However, such differences were largely confined to the male subjects, and 3. In the groups in which ECG-VCG differences were seen, the black children had a thicker left ventricular posterior wall and shorter anterior chest wall to mid-LV distance than in white children, signifying that these factors are likely to be responsible for this difference. On the basis of these observations, we concluded that separate normal standards are needed for males and females beyond 11 years of age and for black and white children older than six years of age. Resolution of arrhythmia-induced congestive cardiomyopathy with medications in a child indicated that all such patients may not need surgical or transcatheter ablation of arrhythmogenic focus, given the state of the art in mid 1980s; however, currently available ablation techniques are likely to be more favorable. Electrocardiographic changes following balloon valvuloplasty for pulmonary stenosis were described which pointed out that the RVH in the ECG gets better during follow-up and the ECG is a good indicator of the improvement in pulmonary valve gradients following balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty, but reduced valve gradients may not be reflected by the ECG until six months after balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty. The role of the ECG in delineating atrial and ventricular situs in patients with dextrocardia and heterotaxy syndromes was reviewed; these concepts initially proposed the late 1970s and early 1980s remain true in the current era. Reviews of arrhythmias and their management in children, advocated in the 1980s, still remain true although new array of drug and transcatheter therapy by specially trained pediatric electro-physiologists have emerged in recent times.

References

- Liebman J, Lee MH, Rao PS, Mackay W (1973) Quantitation of the normal Frank and McFee Parungao orthogonal electrocardiogram in the adolescent. Circulation 48: 735-752. [crossref]

- Rogers JH, Rao PS (1977) Ebstein’s Anomaly of the left atrioventricular valve with congenital corrected transposition of the great arteries: Diagnosis by intracavitary electrocardiography. Chest 72: 253-256. [crossref]

- Rao PS, Monarrez CN (1981) Electrocardiographic differentiation of posterobasal left ventricular hypertrophy from right ventricular hypertrophy. J Electrocardiol 14: 25-30. [crossref]

- Kulangara RJ, Boineau JP, Rao PS (1982) Electrovectorcardiographic features of tricuspid atresia. In: Rao PS (ed). Tricuspid Atresia. Futura Publishing Co., Mount Kisco, New York, Chapter 9.

- Rao PS, Kulangara RJ, Boineau JP, Moore HV (1992) Electrovectorcardiographic features of tricuspid atresia. In: Rao PS (ed). Tricuspid Atresia, 2nd Edition, Futura Publishing Co, Mt. Kisco, NY, Chapter 9.

- Fuster Siebert M, García-Bengochea JB, Rubio J, et al. (1982) [Tricuspid atresia and interatrial communication of the ostium primum type: changes in the QRS electrical axis. Physiopathologic implications]. Rev Esp Cardio l35: 377-381.

- Kulangara RJ, Boineau JP, Moore HV, Rao PS (1981) Ventricular activation and genesis of QRS in tricuspid atresia. Circulation 64: VI-225.

- Rao PS, Thapar MK (1983) The AFORMED phenomenon: A proposed etiology. Am J Cardiol 52: 655. [crossref]

- Rao PS, Thapar MK, Harp RJ (1984) Racial variations in electrocardiograms and vectorcardiograms between black and white children and their genesis. J Electrocardiol 17: 239-252. [crossref]

- Rao PS (1985) Racial differences in electrocardiograms and vectorcardiograms between black and white adolescents. J Electrocardiol 18: 309-313. [crossref]

- Rao PS, Najjar HN (1987) Congestive cardiomyopathy due to chronic tachycardia: resolution of cardiomyopathy with antiarrhythmic drugs. International J Cardiol 17: 216-220. [crossref]

- Rao PS, Solymar L (1988) Electrocardiographic changes following balloon dilatation of valvar pulmonic stenosis. J Interventional Cardiol 1: 189-197.

- Rao PS (2015) Balloon valvuloplasty for pulmonary stenosis. In: Vijayalakshmi IB, , Cardiac Catheterization and Imaging (From Pediatrics to Geriatrics), Jaypee Publications, New Delhi, India, 2015:149-174.

- Rao PS, Leonard T (1976) Polysplenia syndrome. Cardiology Digest 11: 14-22.

- Rao PS (1981) Dextrocardia: Systematic approach to differential diagnosis. Amer Heart J 102: 389-403. [crossref]

- Rao PS (2015) Cardiac malpositions including heterotaxy syndromes. In: Rao PS, Vidyasagar D. (editors), Perinatal Cardiology: A Multidisciplinary Approach, Minneapolis, MN, Cardiotext Publishing, Chapter 36.

- Rao PS (2015) Cardiac malposition. In: Gupta P, Menon PSN, Ramji S, Lodha R (eds). PG Textbook of Pediatrics. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd., New Delhi, India, 2015:1807-16.

- Rao PS (2018) Cardiac malposition. In: Gupta P, Menon PSN, Ramji S, Lodha R (eds). PG Textbook of Pediatrics. Second Edition, Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd., New Delhi, India.

- Rao PS (2021) Cardiac malpositions including heterotaxy syndromes. In: Rao PS, Vidyasagar D. (editors), A Multidisciplinary Approach to Perinatal Cardiology, Volume 2, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, New Castle Upon Tyne, UK, 2021: 433-466.

- Rao PS and Strong WB (1981) Congenital heart disease. In: Current Therapy 1981. Conn HF (Ed), W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia, PA. 1981: 185-209.

- Rao PS (1989) Congenital heart disease. In: Conn’s Current Therapy, 1989 Rakel RE (Ed), W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 1989: 201-13.

- Rao PS, Miller MD (1980) Medical Examination Review, Pediatric Cardiology, Medical Examination Publishing Co., Inc., Garden City, New York, U.S.A., 1980.