DOI: 10.31038/NRFSJ.2020312

Abstract

This mind cartography of craft beers explores what interest’s prospective consumers in a craft beer, and how much they will pay. Each respondent tested unique sets of 48 vignettes, comprising 2-4 elements selected from a set of 36 elements. The permutation strategy enables an individual-level model to be constructed relating the presence/absence of 16 elements (messages) to both rated interest in the beer, and price willing to pay. Clustering the models by individuals revealed two different patterns of mind-sets. The first triple of mind-sets emerges from the interest rating (Homo Emotionalis: Appearance & Beer Story, Flavor & Romance, and Quirky). The second triple of mind-sets emerges from the price selection (Homo Economicus: Quality Package & Flavor; Flavor & Experience; Sensory Decadence). The paper introduces the PVI, personal viewpoint identifier, expanding the findings by assigning new people to a mind-set based upon the response pattern to six question emerging from the segmentation on Question 1 The paper finishes with scenario analysis, an approach to discover how pairs of elements interact in ways that could not have been known at the start of the experiment. The scenario analysis is applied to the interaction of origin to the other elements, both for Homo Emotionalis (ratings of interest, question #1) and for Homo Economicus (selection of price, question #2).

Introduction

Craft beer, a recent development in the word of brewing, has been summarized by Wikipedia as follows:

A craft beer or microbrewery is a brewery which produces small amounts of beer…and is often independently owned. Such are brewers are generally perceived and marketed as having an emphasis on enthusiasm, new flavours and varied brewing techniques. The microbrewing movement began both in the United States and United Kingdom in the 1970’s…

In an age of automation and conformation to production and product specifications in the interest of business, the growth and flowering of the craft beer industry may be symptomatic of a deep of people, viz. to express themselves and their creativity in crafts. In a world where standardization continues relentlessly, and the economics of scale demand conformity, there is a desire for people to express themselves. This expression can be the quotidian act of preparing one’s own food in a creative way, cooking, creating one’s own mixtures of ingredients in smoothies, or creating one’s own beverage by traditional processes, viz., home brewing and the effort of craft brewing. In the world of brewing the appellation of a craft beer may become a strong marketing positive, either because of direct or because of the romanticization of the traditional, the small, and the so-called ‘authentic’ [1-6].

The food and beverage world has welcomed studies about food for more than a century. Food and beverage are important, but of greatest important is the realization that we eat and drink for many reasons, ranging from basic survival to sensory preferences to socially motivated issues like companionship. Furthermore, foods and small, inexpensive items, are purchased not in a strategic way by business specialists, but rather by the ordinary person. Understanding the features of products is important in such a world where freedom of choice is feasible, and indeed a major component with which marketers must contend.

Most of the popular literature, e.g., newspapers, bogs, videos, and so forth, talk about the interesting parts of craft beer, such as the history of the product, the emotions felt in making the product, the emotions of the trade and buyer, and so forth. The stories are ‘happy,’ topical, and of general interest. The science of beer making, and the issues faced by beer makers who are brewing their own craft beers are less interesting, but nonetheless important.

The motivation for this study was the interest in marketing messages about craft beer. The language of craft beer is a romantic one, as one which connotes a rebellion of sorts, and a focus on the ‘arts and crafts’ of brewing. Beers with connections to countries traditional perceived as brewers, e.g., England, Germany, Belgium, etc., are often romanticized as being tasty, and special. Despite the large literature on craft beer from the worlds of marketing, sociology and sensory research, there does not seem to be a systematic analysis readily available of the responses to messages about the nature of craft beer. In the spirit of Mind Genomics, thus study provides a preliminary cartography, focusing on what messages about craft beer drive interest, and what messages drive willingness to pay.

The topic of craft beer, especially the combination of economics and communications, is part of an ongoing project by the authors, focusing on a new approach to understanding of how people make decisions. The general study is Mind Genomics, described below, and the specific focus is an emerging subdiscipline of Mind Genomics, cognitive economics, which fits into the world of behavioral economics. When applied to the topic of ‘what is important’ in craft beer, and what do people say they ‘value economically,’ Mind Genomics provides a contribution both to behavioral economics, and the world of beer.

The Emerging science of Mind Genomics

Mind Genomics is an emerging behavioral science with the objective of studying the decision making of everyday life through simple experimentation. Mind Genomics can be thought as a combination of experimental psychology studying how we make decisions, anthropology to look deeply into behavior, sociology to look at that behavior in the context of life, with influences from the methods consumer research and statistics, respectively. Mind Genomics focuses on a world often overlooked, the world of the everyday, specifically how we make decisions [7-10].

A study on craft beer using Mind Genomics might easily focus on the act of ordering and drinking beer, looking at what is important in the daily acts of choosing to consume, ordering a product, and relaxing with the product. This specific study in Mind Genomics moves beyond that ‘experience-focus’ to a focus on the product per se, to understand how people react to the nature of the craft beer as it is described to them in a small, easy-to read vignettes.

The strategy of Mind Genomics follows a set group of steps, outlined below. To summarize these steps, the objective of Mind Genomics is to understand the nature of the product or experience, doing so by study responses to short, easy to read vignette. The pattern of responses to these vignettes reveals the way the respondent ‘thinks’ about the topic.

The vignettes created by Mind Genomics comprise short descriptions of a product or a service, or even a state-of-mind. The description comprises a series of short phrases, stacked one atop the other in an easy-to-search set of messages. The respondent is instructed to treat this set of disparate messages as one single idea, and to rate this composite as one single idea. The task starts out to be daunting when the first vignette is presented, simply because the vignette seems to be composed in a fashion which seems random, something which disturbs many people. The opposite, however, is true. An underlying ‘experimental design’, viz., a recipe book of specific combinations, guides the composition of each vignette.

When faced with this seeming ‘blooming, buzzing confusion’ in the words of psychologist Wm James, one might think that the respondent would just give up and leave. Most respondents do not, and rather sink down, pay less attention, and respondent to the elements and their combination in a matter that might be construed as guessing. It will be this return to an almost automatic, gut-feel response, which allows Mind Genomics to understand the mind of the consumer, defeating the attempt by people to respond in a way that they believe the researcher wants them to do, defeating the attempt to be ‘politically correct’.

The Process of Mind Genomics

Mind Genomics follows a series of steps to generate the necessary insights and understanding. The steps are straightforward, put together in a way to make research easy to do by being ‘templated’, inexpensive to execute, with deeply analyzed data and reports emerging immediately. The vision is a science which creates a ‘wiki of the mind’ for the ordinary aspects of human behavior, a science which generates databases showing the different aspects of daily life analyzed into its components, and augment with knowledge about what is important to people. We present these steps as a description of responses to craft beer, a topic of increasing interest in markets all around the world.

Step 1: Select a Topic

The topic forces the researcher to think about the issues. Our topic is craft beer. Mind Genomics allows the topic to be broad or narrow. It will not be the topic itself, however, which is important, but rather the specifics as we see in the full set of steps, which, when followed, generate that ‘wiki of the mind’.

Step 2: Select Six Questions which Tell the Story

It is at this step that Mind Genomics departs from many other approaches such as surveys. Mind Genomics begins with a set of questions which allow the research to approach the topic in a granular, ‘micro’ fashion. Rather than focusing on answering ‘big questions’ with the ‘experimentum crucis,’ just the right experiment to answer a question about mechanisms, Mind Genomics uses the questions in the manner of a cartographer, to ‘map out’ a location. The six questions force the researcher to think about what type of information will be relevant about the topic. The questions will be ones answered with a phrase, not with a yes/no or a single word. The researcher ought to think like the proverbial reporter who must focus on information which tells a story. The proper set of questions in the proper order should help that. The reader should note that the two most popular forms of Mind Genomics are the 4×4 (four questions, four answers to each question) and the 6×6 (six questions, six answers to each question, the version used in this study)

Step 3: Formulate Six Separate Answers to Each Question

It is in the selection of answers that Mind Genomics will make its greatest contribution. The iteration towards the most important answers will be the iteration towards deeper understanding of the topic, from the point of view of how people respond to the questions, and thus for our study how people think of craft beer study. At the same time, it is important to stress the simplicity and affordability of iteration, so that Mind Genomics provides a powerful tool to explore, and to learn inductively from patterns, rather than simply a tool to accept or falsify a hypothesis, in the manner of the scientific project as described by philosopher Karl Popper [11].

Table 1 presents the six questions and the six answers for each question. Note that the process is inexpensive, fast, and thus designed to be iterative, to help learning, rather than simply to answer a problem, to ‘plug a hole in the literature,’ in the common parlance of why studies are done.

Table 1: The six questions and the six answers for each question.

| |

Question 1 – What does the beer TASTE like? |

| A1 |

Earthy … hay-like, grassy, and woody |

| A2 |

Crisp … light and clean tasting |

| A3 |

Spicy … Orange, citrus and coriander aromas |

| A4 |

Hoppy … with a high level of bitterness |

| A5 |

Dark … bittersweet chocolate and coffee flavors |

| A6 |

Sour taste with a fruitiness … dark cherry, plum, currants |

|

Question B: What does the beer LOOK like? |

| B1 |

A little hazy or cloudy |

| B2 |

Pale, clear and light bodied |

| B3 |

Amber colored and medium bodied |

| B4 |

Dark and full bodied |

| B5 |

Dense, long-lasting head … stays until your last sip |

| B6 |

Not too fizzy … just the right amount of carbonation |

|

Question C: What is the drinking experience ? |

| C1 |

Long lingering finish keeps delivering pleasure |

| C2 |

Short finish prepares you for your next sip |

| C3 |

Smooth, creamy mouthfeel |

| C4 |

A mouthfeel that leaves you a little dry and puckering |

| C5 |

So good … should be appreciated without food |

| C6 |

Pairing this beer with your meal … brings out the best in both |

|

Question D: Where is the beer brewed? |

| D1I |

From a local craft brewer … with a great story |

| D2 |

Brewed in the USA |

| D3 |

From Mexico |

| D4 |

Imported from Belgium |

| D5 |

From the UK |

| D6 |

From Germany |

|

Question E: What is the benefit? |

| E1 |

Refreshing and thirst quenching …Hits the spot on a hot summer’s day |

| E2 |

Helps you unwind after a busy day |

| E3 |

A beer for bonding and relaxing with friends |

| E4 |

Savor and enjoy slowly |

| E5 |

Brewed from the heart … authentic, hand-crafted |

| E6 |

A great beer to include in your beer appreciation journey |

| |

Question F: Where do you get it (venue), how do you drink it? |

| F1 |

Best enjoyed with the right type of glass … served at the right temperature |

| F2 |

Drink it straight from the can or bottle |

| F3 |

Fun, irreverent label |

| F4 |

Limited availability … buy from a beer specialty store |

| F5 |

Packaged in a brown glass bottle … to stay fresher longer |

| F6 |

Buy it anywhere beer is sold |

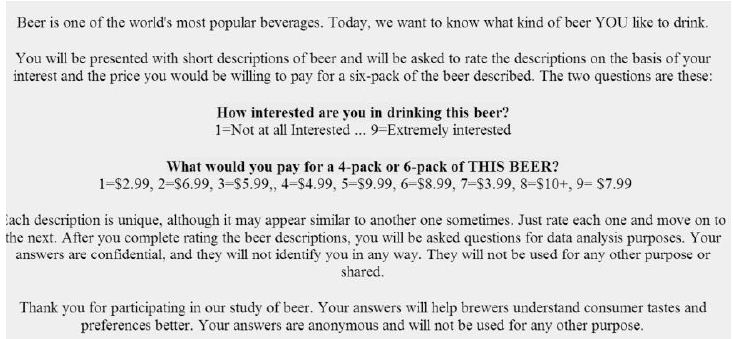

Step 4: Create a Simple Orientation Page to Tell the Respondents about the Study

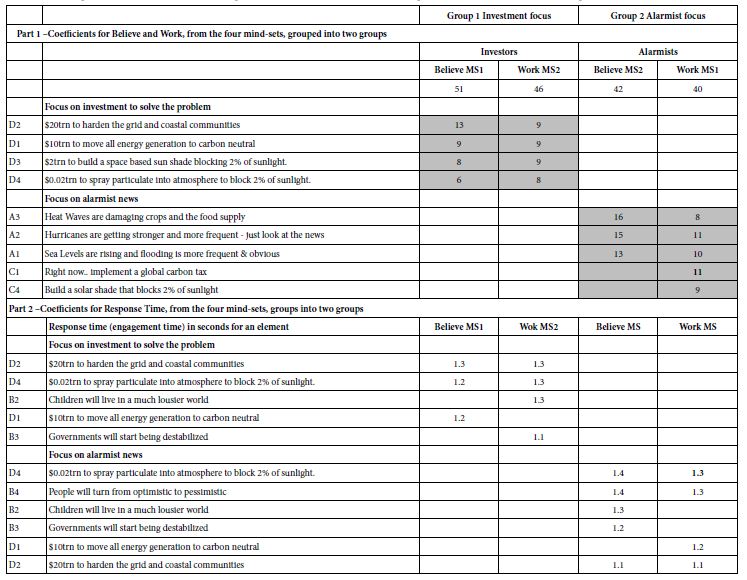

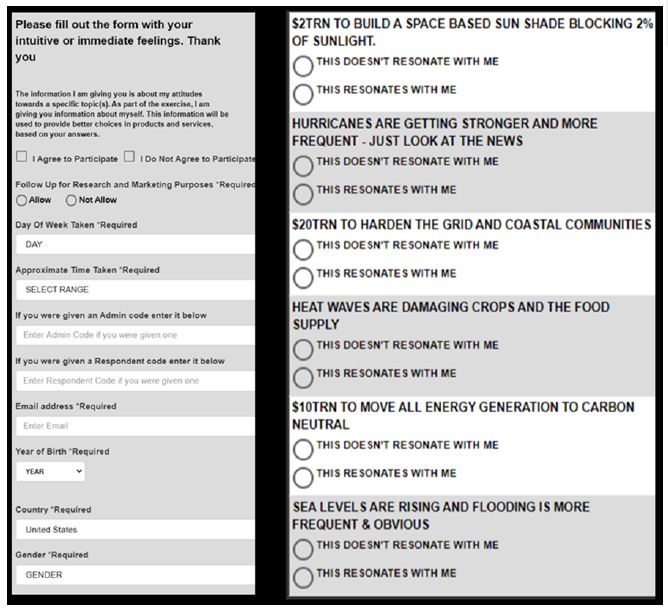

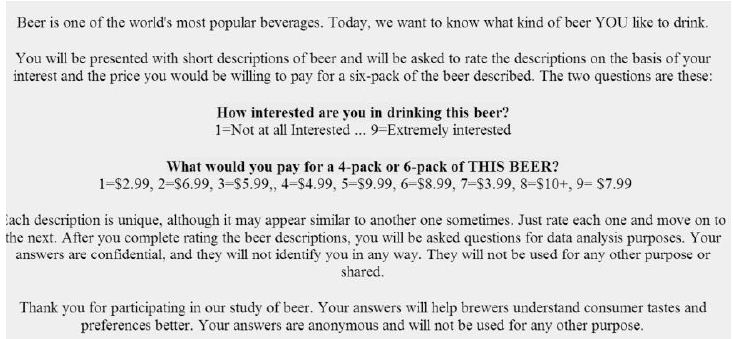

Figure 1 shows the orientation, and the scale. Note that for this version of Mind Genomics there are two scales and 36 elements, the practice appropriate during the years 2010-2016, when the consumers were not over-sampled, and when it was feasible to do studies lasting 15-17 minutes. Those ‘early days’ are now gone, and most studies must be kept to less than five minutes because of the reduced attention time characteristic of today’s over stimulating environment.

Figure 1: The orientation page.

Note in Figure 1 that the interest scale goes from a low of 1 to a high of 9, but the price scale is in irregular order of prices. This irregular order is a precaution to ensure that the price scale does not turn into another interest scale. When assigning prices, the respondent must ‘think’ because the prices are in irregular order. It is also noteworthy that the respondent is given as little information as possible. The paucity of information is relevant when the respondent is familiar with the topic. In other situations, such as studies in the law or in medicine, the orientation page may be a good deal longer, more filled with relevant detail.

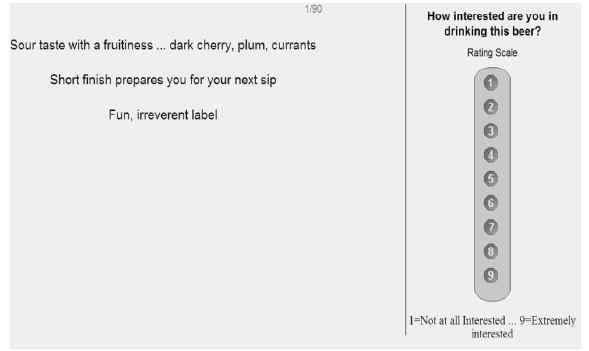

Step 5: Combine the Answers into Small, Easy to Read Combinations, So-called Vignettes

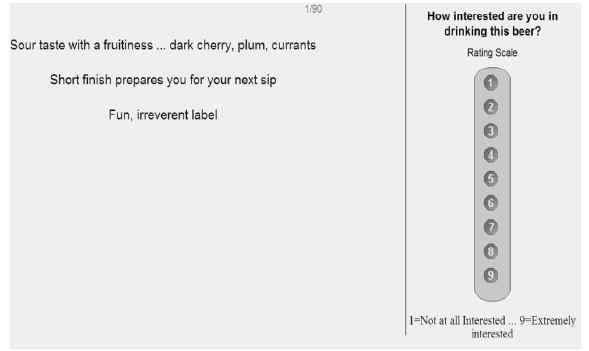

Figure 2 shows the way the vignette appears to the respondent, with the text centered, one answer or ‘element’ atop the other in centered format, with no effort to connect the answers. It is the respondent’s job to read through the information and make a judgment. The effort to connect the elements is counter-productive because the focus is on the individual elements and not on a connected paragraph.

Figure 2: Example of a vignette (left) comprising three elements (left) and the rating scale (right).

The vignettes are created according to an experimental design, which dictates combinations comprising 3-4 elements for the 6×6 design, at most one element or answer from each question. Each respondent evaluates 48 unique vignettes. Each element appears five times, one time in each of five vignettes, and is absent from the remaining 43 vignettes. The experimental design creates combinations ensuring that each respondent will see a full design, but the specific combinations will differ across respondents thus covering a lot of the ‘design’ space. The experimental design is set up so that the 36 elements are statistically independent of each other, allowing for OLS (ordinary leas-squares) regression to relate the presence/absence of the elements to the respondent (interest, price paid).

Each respondent sees a unique set of 48 vignettes, an experimental design for that respondent. This means that the data from each respondent can be analyzed either separately as preparation for mind-set segmentation (see below), or using group data to generate a model (e.g., for all respondents in the study, viz., the total, or for all respondents in a specific mind-set).

The questions themselves do not appear in the vignette. Rather, only the answers appear; it is the answers which convey the specific information. The questions act as guides, to drive the ‘right’ type of answer. The specific information in the answer is left to the researcher, who may use a variety of sources to create the answer. The answer is usually presented as a stand-alone phrase, one emerging from competitive analysis, from published information, or even from one’s imagination in a creativity session.

Finally, the experimental design is set up so that there is absolutely no collinearity possible, and that there are ‘true zeros.’ True zeros, where a question (or so-called variable) is entirely absent from a vignette ensures that the coefficients have absolute values, comparable from study to study.

Executing the Mind Genomics Experiment and Preparing the Data for Analysis

Step 6: Invite Respondents to Participate

With the advent of the Internet, a great deal of research has migrated to online venues, wherein the respondent is invited by an email or pop-up link. At the time of this research (2016) the studies with the 6×6 design took approximately 15-18 minutes to complete, comprising 48 vignettes, each rated on two scales, along with an extensive classification. Six years before, by the year 2010 or so, respondents were tiring of the ever-increasing number of requests to participate, and it was becoming harder to get volunteers. At that point, companies began to enter the business, and provide respondents from their so-called ‘on-line’ panels; groups of individuals who agreed to participate, and were recompensed by the company. The result was an easier-to-execute study, albeit not with paid respondents. For Mind Genomics studies, looking for patterns rather than for single ratings of no/yes, the paid panel was appropriate. The panelists for this study were recruited by Luc.id, Inc.

Step 7: Execute the Study on the Respondent’s Computer, Tablet, or Smartphone

The respondent received the invitation from Luc.id, opened the study (an experiment), read the introduction, evaluated 48 vignettes unique to the respondent (ensured by the strategy of permuted experimental design), and then completed an extensive self-profiling classification.

Step 8 – Acquire the Ratings and Transform the Data

The ratings for interest were converted to two binary scales:

Top3, focusing on what interested the respondent. Ratings of 1-6 were converted to 0, to show little or no interest. Ratings of 7-9 were converted to 100, to show active interest. A random number(< 10-5) was added to each transformed rating to ensure variation in the dependent variable in case the respondent selected ratings all lying between 1 and 6 or all lying between 7 and 9.

Bot3, focusing on what actively disinterested the respondent (viz., anti-interest). Ratings of 1-3 were converted to 100, to show active disinterest. Ratings of 4-9 were converted to show little or no disinterest. Again, the small random number was added for the same prophylactic reason, viz., to ensure variation in the dependent variable.

The prices were converted to dollar values. The Mind Genomics program measured the Response Time (RT), defined as the number of seconds to the nearest tenth of seconds elapsing between the appearance of the vignette on the respondent’s screen and the first response (question #1, interest)

Step 9: External Analyses – Distribution of Ratings

Mind Genomics studies generate a great deal of data, providing a rich bed of results for analysis. The basic data, without knowledge of the composition of the stimulus vignette, are the ratings and the response times, along with external information, such as the position of the vignette in the set of 48, the respondent who assigned the rating, etc.

The analysis of these data is called ‘external analysis’, so-called because we do not know anything about the nature of the stimulus, other than the number and source of elements. There is not yet any linkage between the responses and the meaning of the elements. This is the type of data with which most researchers work, looking for patterns, but forced to work with data which themselves have no intrinsic meaning. The pattern of data emerging from this analysis tells us a great deal about how the respondent thinks about the topic, in terms of ratings, in terms of response times, and in terms of changing responses with repeated evaluation of vignettes, but without any understanding of the ‘meaning’ of the test stimuli and the differences among the feelings toward these stimuli traceable to the nature of the difference stimuli.

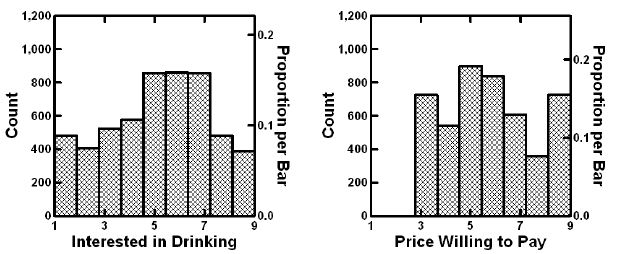

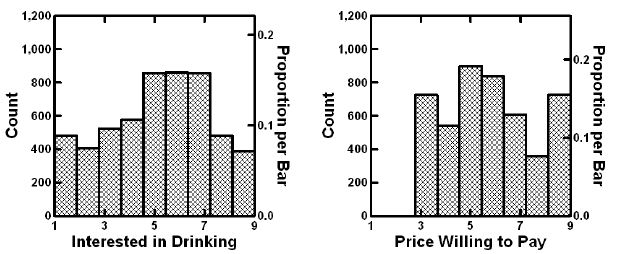

The first external analysis assesses the distribution of the ratings, and the response times. Figure 3 shows two histograms, the left showing the distribution of the ratings on the 9-point scale, the right showing the distribution of the prices the respondent is willing to pay. Keep in mind the prices were converted to the appropriate dollar value.

Figure 3: External analysis showing the distribution of ratings for interest (left) and for price that one would pay (right). Data from the total population.

The ratings of interest describe a reasonable, but certain far from ideal inverted U curve, which could be interpreted as a ‘somewhat’ normal distribution. The only problem is the excessive number of ratings at level 1, the lowest interest. The price willing to pay shows no consistent patterns.

It is important to keep in mind that without deeper knowledge of what the elements mean (viz., their exact language), the researcher has nothing to analyze except for these externalities. There are no insights yet, despite the substantial amount of data used to create the graphs in Figure 3.

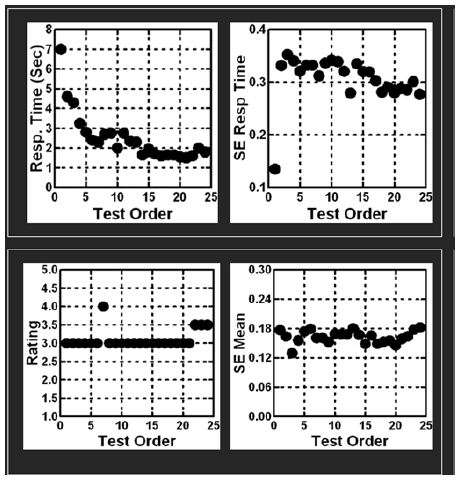

Step 10: External Analyses: Stability vs. Instability across the 18-Minute Experiment with 48 Vignettes

Our second ‘external analysis’ measures the change in the average rating across the 48 positions. Recall that each respondent tested a unique set of 48 combinations. One of the questions that we might ask is whether over time, and with these many combinations, do people change their criteria of judgment in a general fashion, becoming more critical, less critical, and so forth. That is do people increase their rating or decrease their rating as they evaluate the set of 48 vignettes?

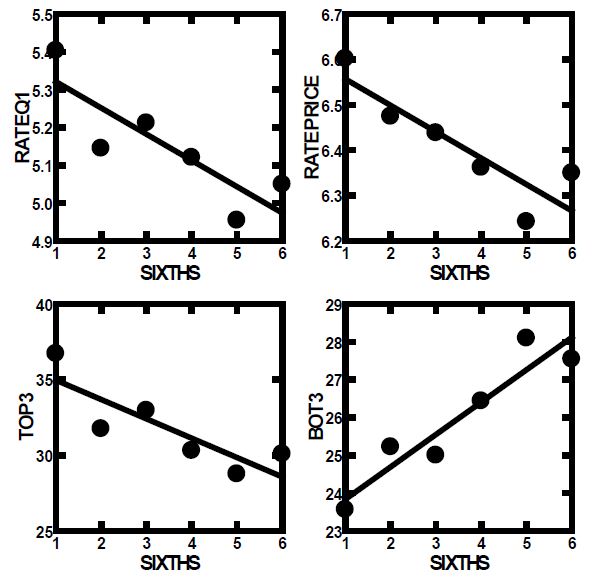

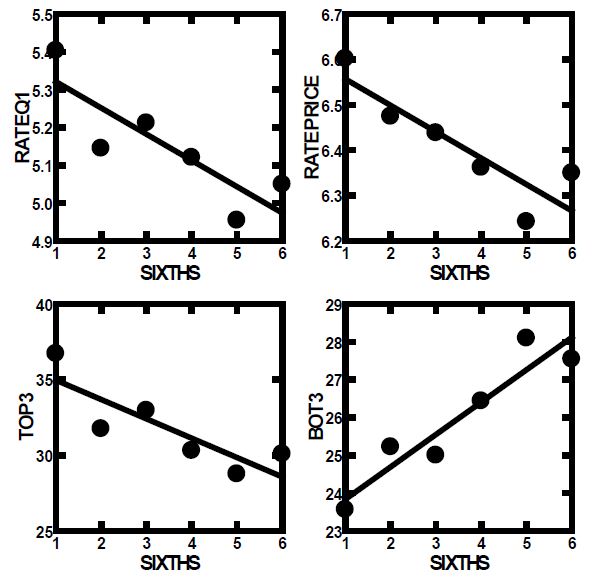

The set of 48 ratings was divided into six strata, each stratum comprising data from eight positions, viz., 1-8, 9-16, 17-24, 25-32. 33-40, 41-48. The averages were computed for each position and plotted in Figure 4. The plots are linear, suggesting a systematic but modest drop in the positive ratings, a complementary but slightly steeper pattern of increase in the negative ratings, and a sharper drop in price of almost 50 cents. The pattern is sharply linear, and reaffirms the value of completely rotating the combinations, in addition to create a unique design permutation for each respondent.

Figure 4: How the average rating and price paid change during the evaluation. Each point represents the average rating from a set of six positions in the 48 vignettes (viz., 1-8, 9-16 etc.).

Step 11: External Analyses: An Emergent Linear Relation between Interest and Price Willing to Pay

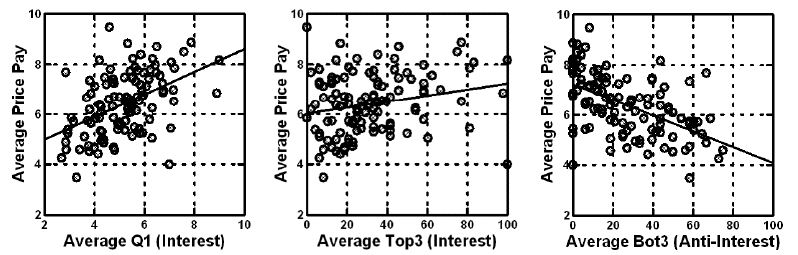

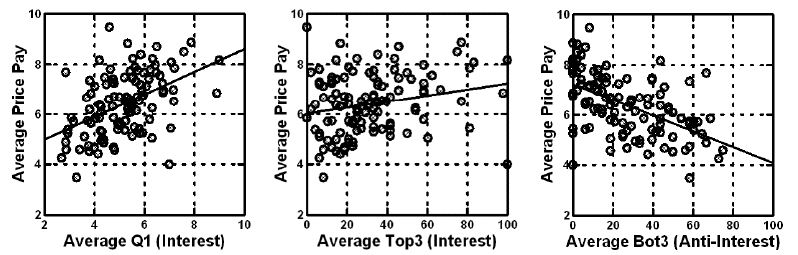

We expect that people will pay more for what they like, although we have no direct data from studies. People can be asked whether they like something, and what they are willing to pay for this. The analysis has been called ‘hedonic pricing’ [12]. The pattern will not appear from the raw data comprising 113 respondents x 48 vignettes/respondent or 5424 data points. There are so many observations that a clear pattern cannot easily emerge.

When one does this analysis by averaging the interest ratings of respondents across the 48 vignettes, and the price willing to pay across the same 48 vignettes, one has a value both for average interest and another value for average price. Across the 113 respondents there are thus 113 pairs of averages. Figure 5 shows a pattern which is linear when the independent variable is either average rating on the interest scale (question 1), average Top3 (interest), or average Bot3 (anti-interest. It is important to note that we use individual averages to get a sense of liking vs. price, an analysis that economists call ‘cross sectional analysis’.

Figure 5: Relation between average price willing to pay (ordinate) and rating (Question 1, left panel), Top3 (interest, middle panel), and Bot3 (anti-interest, right panel). Each circle corresponds to one of the 113 respondents.

Moving from External Analyses of Patterns to Deeper Understanding through Vignette Structure

The external analysis can bring our understanding to an appreciation of possible relations between variables. Indeed, much of behavioral science stops at the observation of these observed relations, leaving the rest for conjecture. At some point during the inquiry into the topic, one or another enterprising researcher may pick up problem, and precede somewhat further, usually with a different viewpoint, different tools. The direct line is lost, viz., the line connecting the research of the problem, and the subsequent research inspired by the original investigation, usually, the research is conducted by an entirely different group, with different motivations, tools, and world views. As an aside, the inevitable is that the scientific project is often metaphorically compared to an object with many holes, many gaps, many ‘calls for further work’, and so forth.

The motive for this slight detour is the ability of Mind Genomics to move from the study of external patterns into the immediacy of the mind, at least with respect to the topic. Beyond that simple migration from the ‘external’ to the ‘internal’ is the ability of Mind Genomics to iterate through repeated and evolving studies while the topic is studied, viz. ‘to strike when the iron is hot’.

With that in mind, we move now to the beginning of the internal analysis, and the introduction of cognitive meaning. The first internal analysis looks at the general content of the vignettes, and how the content covaries with estimated Top3 (interest), estimated Bot3 (anti-interest) and estimated Price.

There are three ways to understand the relation between the surface structure of the vignette and the rating.

a. What is the relation between the number of elements in the vignette and the response? That is, are we likely to get lower or higher ratings with vignettes comprising three elements versus vignettes comprising four elements? The approach here is to relate the number of elements to the ratings, without knowing which specific elements are present in the vignette. The statistics use regression to estimate the parameters of the equation: Rating = k1(Number of elements). We can estimate the equation for the total panel, and then estimate the equation as the respondent moves through the 48 vignettes. Is there a change in the pattern as the respondent moves from the first eight vignettes, to the second eight vignettes, until the sixth of the eight vignettes?

Table 2 shows the number of scale points corresponding to each element in the vignette. We do not know what is contained in the vignette. We just know the number of elements in the vignette, either three or four, respectively. We are beginning to get a sense that longer vignettes comprising four elements are better than shorter vignettes comprising three elements for emotion-relevant responses. As a worked example, consider the Total panel. For vignettes comprising three questions we expect to have a 9-point rating scale of 3×1.36 or 4.08. When we look at the expected rating but at the beginning of the evaluations (vignettes 1-8) we expect a rating of 3×1.42, or 4.26. When we look at the expected rating, but at the end of the evaluations, vignettes 41-48, we expect a rating of 3.99. The data in Table 2 suggests that there will be little change in the ratings, but when we look at the Top3 we expected a lower rating, when we look at the Bot3 we expect a higher rating (more negative), and when we look at price we expect little change.

Table 2: The number of points added by each element in the vignette, independent of the nature of the questions or the specific elements.

|

Number of points on scale corresponding to each element in the vignette |

| Question #1 |

TOP3 |

BOT3 |

PRICE |

| Total |

1.36 |

8.41 |

6.81 |

$1.69 |

| Vignettes # 1-8 |

1.42 |

9.72 |

6.26 |

$1.74 |

| Vignettes # 9-16 |

1.36 |

8.37 |

6.56 |

$1.71 |

| Vignettes # 17-24 |

1.37 |

8.75 |

6.56 |

$1.70 |

| Vignettes # 25-32 |

1.35 |

8.05 |

6.95 |

$1.68 |

| Vignettes # 33-40 |

1.31 |

7.66 |

7.31 |

$1.65 |

| Vignettes # 41-48 |

1.33 |

7.91 |

7.21 |

$1.66 |

a. On average, what does each question contribute to the rating? This question can be answered by determining which specific questions are present in each vignette and relate the presence/absence of the type of question (Taste, Appearance, etc.) to the rating. To answer this, we create a simple model for total panel, and for each set of six vignettes. The model is expressed as: Rating = k1(Taste) = K2(Appearance) + k3(Experience ) + k4(Origin) + k5(Benefit) + k6(Venue).

Table 3 shows that the most important driver of Top3 (interest) and Bot3 (anti-interest) is Taste. Appearance is a driver of interest, but not a driver of anti-interest, which makes sense from other information about food. People do not form polarizing love/hate relationships with appearance in the same way that they do with taste/flavor. Homo Emotionalis, emerging from likes and dislikes of a sensory and experiential nature, is far more expansive than is Homo Economicus, which is constricted. We know what we like, but we don’t know the value of what we like or dislike.

Table 3: The number of points added by each question in the vignette, independent of the nature of the specific element.

| Top3 |

Total |

Vig. 1-8 |

Vig. 9-16 |

Vig. 17-24 |

Vig. 25-32 |

Vig. 33-40 |

Vig. 41-48 |

| Taste |

9.9 |

9.6 |

11.5 |

8.6 |

8.6 |

9.5 |

9.9 |

| Appearance |

9.3 |

10.2 |

9.6 |

7.6 |

7.6 |

10.1 |

7.3 |

| Origin |

8.8 |

6.5 |

6.5 |

9.5 |

9.5 |

8.4 |

11.0 |

| Venue |

8.0 |

9.8 |

3.2 |

8.5 |

8.5 |

9.6 |

6.5 |

| Experience |

7.7 |

11.1 |

10.5 |

6.5 |

6.5 |

2.9 |

10.3 |

| Benefit |

6.8 |

11.0 |

9.2 |

7.7 |

7.7 |

5.4 |

2.3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bot3 |

Total |

Vig. 1-8 |

Vig. 9-16 |

Vig. 17-24 |

Vig. 25-32 |

Vig. 33-40 |

Vig. 41-48 |

| Taste |

12.1 |

9.2 |

13.0 |

11.3 |

11.3 |

14.6 |

14.3 |

| Experience |

6.6 |

8.4 |

6.8 |

3.7 |

3.7 |

8.8 |

7.8 |

| Venue |

6.3 |

4.0 |

9.8 |

7.0 |

7.0 |

8.4 |

5.3 |

| Origin |

5.7 |

5.7 |

4.9 |

6.5 |

6.5 |

4.7 |

3.5 |

| Benefit |

5.4 |

7.1 |

2.3 |

7.5 |

7.5 |

2.9 |

6.9 |

| Appearance |

4.7 |

3.2 |

2.2 |

5.6 |

5.6 |

4.5 |

5.7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Price |

Total |

Vig. 1-8 |

Vig. 9-16 |

Vig. 17-24 |

Vig. 25-32 |

Vig. 33-40 |

Vig. 41-48 |

| Taste |

$1.72 |

$1.75 |

$1.73 |

$1.73 |

$1.73 |

$1.64 |

$1.58 |

| Appearance |

$1.72 |

$1.91 |

$1.73 |

$1.63 |

$1.63 |

$1.78 |

$1.68 |

| Origin |

$1.71 |

$1.72 |

$1.69 |

$1.62 |

$1.62 |

$1.69 |

$1.72 |

| Experience |

$1.67 |

$1.50 |

$1.85 |

$1.76 |

$1.76 |

$1.48 |

$1.72 |

| Benefit |

$1.67 |

$1.69 |

$1.72 |

$1.76 |

$1.76 |

$1.67 |

$1.62 |

| Venue |

$1.66 |

$1.86 |

$1.54 |

$1.56 |

$1.56 |

$1.65 |

$1.66 |

a. On average, which structure of the vignette drives the rating? There are 35 different structures of vignettes in the Mind Genomics design. Comprising six questions and six answers for each question. There are 20 different structures comprising three questions out of the six, and 15 different structures comprising four questions out of the six. Each vignette can be coded as being one of these 35 design structures. Do any of these design structures perform noticeably better or worse than others, in terms of Top3 (interest), Bot3 (anti-interest) or Price? Each of these 35 design structures became its own variable, taking on the value 1 for a vignette when the vignette conformed to that specific structure, and taking on the value 0 for a vignette when the vignette did not conform to that structure. A vignette could be coded ‘1’ for only one structure.

Table 4 shows that there is a large range of interest (Top3), from a high of 40 (Appearance, Experience, Origin; Top 3 = 40), to a low of 15 (Experience, Benefit, Venue). There is a similar range for Bot3 (anti-interest), but hardly any range for price. Once again, Homo Emotionalis is far more expansive than Homo Economicus.

Table 4: The number of points added by each design structure of a vignette, independent of the nature of the specific elements in the design.

| Code |

Vignette comprises one element from: |

Est Top3 |

Est Bot3 |

Est Price |

| |

Three-element vignettes |

|

|

|

| BCD |

Appearance Experience Origin |

40 |

22 |

$6.32 |

| ABD |

Taste Appearance Origin |

37 |

21 |

$6.31 |

| ABF |

Taste Appearance Venue |

36 |

31 |

$6.09 |

| BCF |

Appearance Experience Venue |

34 |

23 |

$6.60 |

| ADE |

Taste Origin Benefit |

33 |

24 |

$6.12 |

| ACF |

Taste Experience Venue |

32 |

30 |

$6.44 |

| BEF |

Appearance Benefit Venue |

32 |

17 |

$6.44 |

| ADF |

Taste Origin Venue |

31 |

26 |

$6.46 |

| ACD |

Taste Experience Origin |

30 |

27 |

$6.80 |

| ABE |

Taste Appearance Benefit |

29 |

32 |

$6.13 |

| ABC |

Taste Appearance Experience |

28 |

25 |

$6.18 |

| BCE |

Appearance Experience Benefit |

28 |

28 |

$6.29 |

| ACE |

Taste Experience Benefit |

27 |

24 |

$6.54 |

| BDF |

Appearance Origin Venue |

27 |

32 |

$6.11 |

| CDF |

Experience Origin Venue |

27 |

26 |

$5.88 |

| CDE |

Experience Origin Benefit |

24 |

41 |

$5.82 |

| AEF |

Taste Benefit Venue |

23 |

30 |

$6.52 |

| DEF |

Origin Benefit Venue |

20 |

29 |

$5.81 |

| BDE |

Appearance Origin Benefit |

16 |

39 |

$5.91 |

| CEF |

Experience Benefit Venue |

15 |

35 |

$6.14 |

| |

Four element vignettes |

|

|

|

| ACDE |

Taste Experience Origin Benefit |

36 |

30 |

$6.56 |

| ADEF |

Taste Origin Benefit Venue |

36 |

25 |

$6.59 |

| ABCD |

Taste Appearance Experience Origin |

35 |

26 |

$6.52 |

| ABDE |

Taste Appearance Origin Benefit |

35 |

26 |

$6.64 |

| ABEF |

Taste Appearance Benefit Venue |

35 |

25 |

$6.35 |

| BCEF |

Appearance Experience Benefit Venue |

35 |

18 |

$6.60 |

| ABCF |

Taste Appearance Experience Venue |

34 |

30 |

$6.29 |

| BCDE |

Appearance Experience Origin Benefit |

34 |

20 |

$6.70 |

| ABDF |

Taste Appearance Origin Venue |

33 |

30 |

$6.40 |

| ACEF |

Taste Experience Benefit Venue |

33 |

31 |

$6.42 |

| BCDF |

Appearance Experience Origin Venue |

33 |

20 |

$6.43 |

| CDEF |

Experience Origin Benefit Venue |

31 |

21 |

$6.50 |

| ACDF |

Taste Experience Origin Venue |

27 |

31 |

$6.18 |

| BDEF |

Appearance Origin Benefit Venue |

26 |

22 |

$6.45 |

| ABCE |

Taste Appearance Experience Benefit |

21 |

32 |

$6.16 |

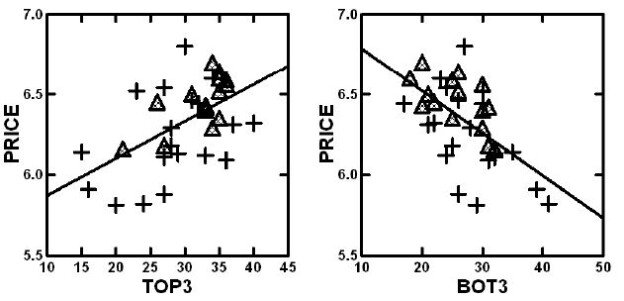

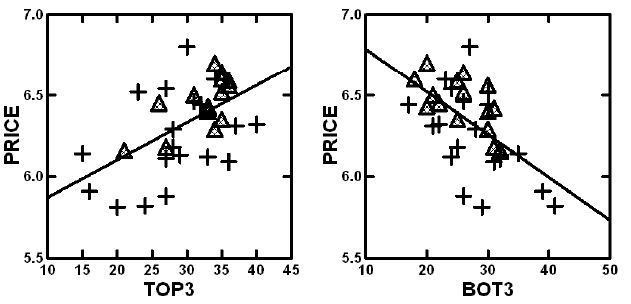

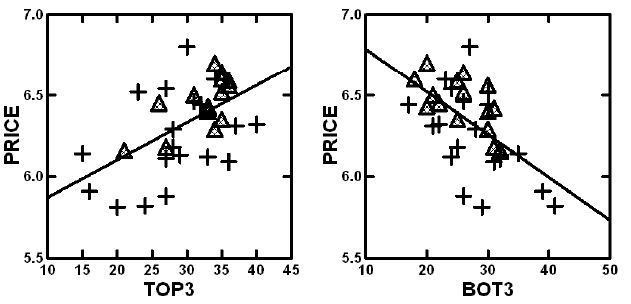

A scattergram plot from the price structure (Table 4) of Estimated Price (ordinate) versus estimated Top3 (interest) or Bot3 (anti-interest) (abscissa) show a clear relation between price willing to pay (ordinate) and either interest or anti-interest. The triangles correspond to the vignettes comprising four elements; the crosses correspond to the vignettes comprising three elements. Figure 6 suggests a clear linear, yet somewhat noisy relation between price and interest or anti-interest.

Figure 6: Plot of the estimate price to be paid versus the estimated Top3 (interest, left panel) or Bot3 (anti-interest, right panel). Data from Table 4, showing the estimated values for different vignette structures.

Internal Analysis: Moving from Vignette Structure to the Impact of the Individual Element

Up to now the analysis has focused primarily on the externalities of the data, the averages and distributions of the ratings, and relations between variables. There is no deep understanding of what the data mean. Indeed, we have no idea about the topic of the data, other than knowing that the data pertain to responses to messages about craft beer. We have been able to learn a lot, and in fact may even be able to create hypotheses about what might be occurring. Our hypotheses deal with the behavior of what is occurring, focusing both regularities in the data, and on emergent patterns, respectively. To reiterate, however, we would have no idea about how people describe the specifics of the craft beer experience.

It is at this point that we return to the fact that we really do ‘know’ what these elements mean, at least in a superficial way. The researcher might well have asked the respondent to rate the interest in beer and the price of the beer, after exposing the respondent to each element, one elements at a time. The answers would be ‘strained’ because it is hard to make a judgment based on one element, but the data emerging from that question and answer would, in fact, provide deeper knowledge, data which are ‘internal,’ rather than external, data which deal with the ‘meaning’ of the element.

The Mind Genomics process moves from evaluation of single elements in a question-and-answer format to the evaluation of systematically varied combinations of elements, so-called test vignettes. Respondents have an easier time reacting to a combination of elements which tell a story, even when the combination or ‘story’ emerges out of an experimental design, an underlying set of combinations fabricated according to statistical considerations, rather than dictated by the desire to tell a story.

Step 12: Lay Out the Data for OLS (Ordinary Least-Squares) Analysis

With 113 respondents, the data comprises one row for each vignette for each respondent (113 x 48 =5424 rows). The data matrix just created comprises one column for each of the elements, or precisely 36 columns to ‘code’ the independent variables, the 36 elements.

The matrix contains the number ‘1’ when the element is present in the vignette, and the number ‘0’ when the element is absent from the vignette.

At the end of the input matrix are five columns, corresponding to the dependent variables.

The first pair of response data columns are the two ratings, for interest, and for actual price, and the second pair of response data columns are the two transformed variables, Top3 (either 0 or 100) and Bot3 (either 0 or 100), respectively.

Step 13: Create 113 Individual Models for Top3, and 113 Individual Models for Price, One per Respondent

This is a preparatory step. The individual level models can be readily created because the original experimental design ensured that each respondent would evaluate 48 unique vignettes, created according to a full experimental design. That provision enables the researcher to create an individual-level model for a respondent. The subsequent analysis clusters the 113 respondents twice, first by the pattern of the 36 coefficients of Top3, and then the pattern of the 36 coefficients for price. The clustering is done by k-Means, a well-accepted statistical process which created groups of respondents whose patterns of coefficients are maximally similar within a cluster, and whose patterns of averages of coefficients within a cluster maximally different from cluster to cluster. These clusters are created by k-means clustering, using the distance metric (1-Pearson Correlation). Two respondents are most similar, perfectly related to each other and in the same cluster when the Pearson Correlation calculated from the 36 coefficients is 1.0. Two respondents are most different from each other, and in different clusters, when the Pearson Correlation between them calculated from the 36 coefficients is -1 (perfectly opposite). Three clusters emerged from the clustering of the Top3, and three other clusters emerged from the (separate) clustering of the Price [13,14].

We call these clusters ‘mind-sets’ because they represent the way the respondent thinks about the topic. The respondent may or may not be able to tell the researcher her or his own mind-set, but it will become clear from the study, or later from a tool called the PVI, personal viewpoint identifier.

Step 14 – Extract Three Mind-sets for Top3 (What Interests), and Three Parallel Mind-sets for Price (Pattern of What They will Pay)

Create two sets of models or equations, one for Top3, and one for Price, respectively. The models look the same, except the Price model does not have an additive constant.

Top3 = k0 + k1(A1) + k2(A2) … k36(F6)

Price = k1(A1) + k2(A2) … k36(F6)

Step 15: Uncover the Mind-sets Based on What Interests the Respondent about Craft Beer

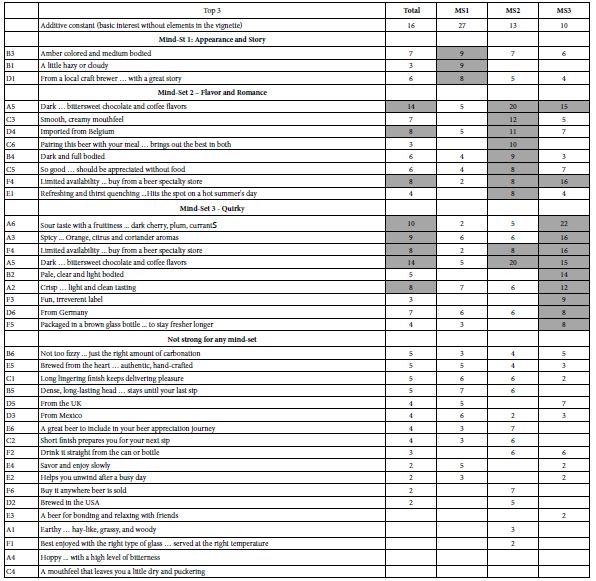

Lay out the coefficients for the Top3 model, but do not put in any of the negative coefficients which are 0 or negative. Furthermore, highlight the coefficients which are +8 or above. The rationale for showing only partial data is to ensure that the pattern of coefficients emerges clearly, allowing the researcher to identify the elements which ‘drive’ interest. Putting in 0 and negative coefficients hinders the ability identify the patterns. Furthermore, sort the table by the three mind-sets.

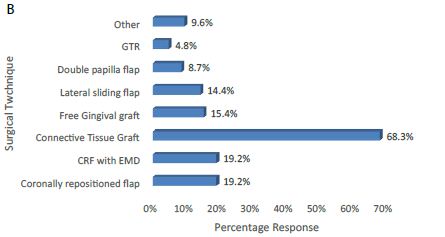

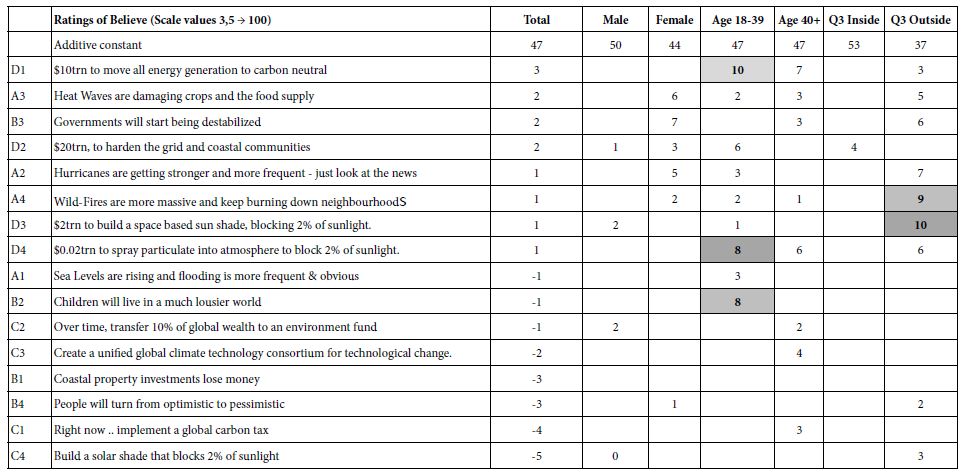

Table 5 shows the additive constant and the coefficients for the total panel and the three emergent mind-sets. For the Total Panel, two elements emerge: A5 (Dark…bittersweet chocolate and coffee flavors, coefficient = 14) and A6 (Sour taste with fruitiness … dark cherry, plum, currants, coefficient =10). One might think that these two KEY elements for craft beer. They are certainly strong elements, but the division of the respondents into three mind-sets reveals different groups with varying preference, and many more opportunities when these groups can be identified and receive the proper advertising for craft beer. The opportunity for business as well as learning will be enhanced by understanding how the respondents divide in the pattern of their preferences, especially when the rating scale is ‘interest’ (question 1).

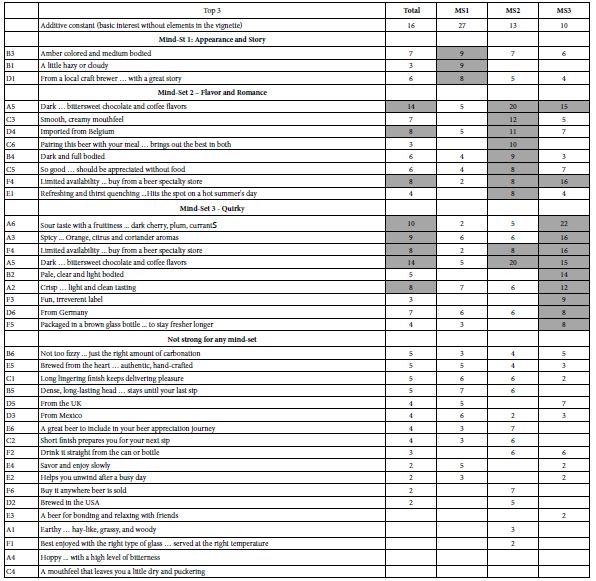

Table 5: Positive coefficients for the 36 elements for Total Panel and for three mind-sets. Data based on the coefficient for the Top3 value from all respondents in the group.

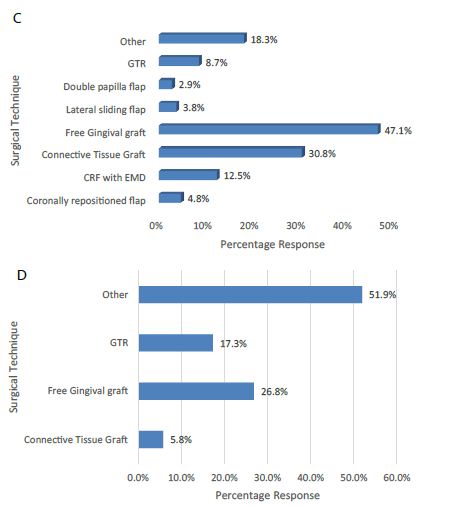

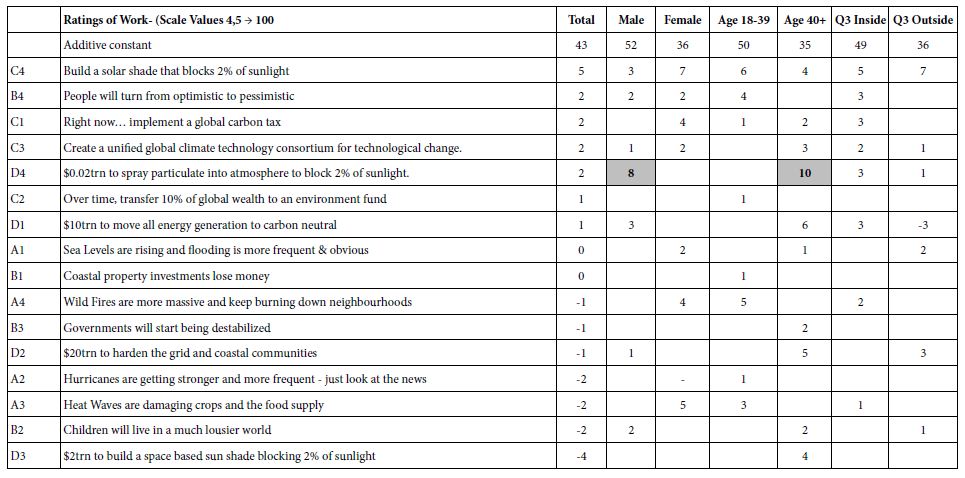

Step 16: Uncover the Patterns for Mind-Sets Based on Price the Respondent is Willing to Pay

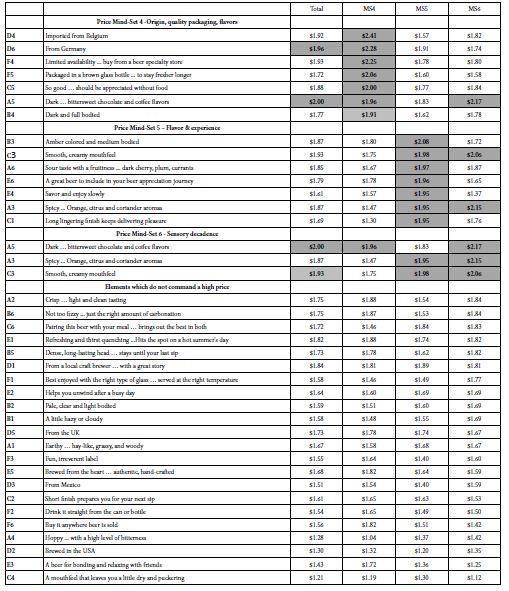

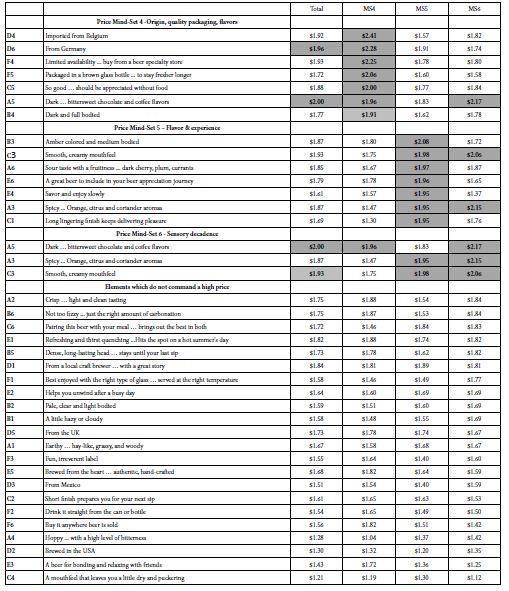

Lay out the 36 elements for price, sorted by the three emergent mind-sets based on clustering using the price coefficients. Table 6 shows these results. In contrast to Table 5, all prices are shown; although for the patterns one might eliminate a low price, such as $1.60 or less. The choice of what constitutes an irrelevant element is left to the researcher.

Table 6: Coefficients for the 36 elements for Total Panel and for three mind-sets. Data based on the coefficient for Price from all data from respondents in the group.

Table 6 suggests three groups of respondents whose preferences are less polarized when the groups are constructed based upon the patterns of price (Homo Economicus). The groups certainly different in the price that they are willing to pay for the feature. On the other hand, within a mind-set (homogeneous with respect to price), the nature of the specific elements driving the high price is not clear. The groups are more similar than they are different, based upon the ‘meaning ‘of the elements. This leads us to the conclusion that clustering or segmenting people based economic aspects, such as price, will ‘work’ in terms of delivering statistically meaningful clusters. That is accepted because the clustering is assumed to be done correctly. What is surprising, however, is the difficulty of seeing the dramatically different patterns across the clusters created by the price coefficients. Homo Economicus does exist, and can be demonstrated, but is clearly less interpretable.

Step 17: Create a Method to Discover these Mind-sets in the Population

Mind Genomics reveals mind-sets based upon the pattern of responses to granular information about relatively small, minor topics. As such, the conventional methods used by researchers to create ‘personas’ in the population and assign an individual to one of these persona’s is limited, both by the reality that the topic is usually too small to invest in, and that the research may often be investigating the topic as the first person to do so.

The value of the mind-set is knowledge, which simply remains within the data, but the larger value is to assign NEW PEOPLE to mind-sets, whether to understand people, or more ambitiously to link together behaviors and markers (biological, sociological, behavioral, respectively). All are possible, once there emerges a simple, cost-effective method to assign new people to the mind-sets already discovered.

Table 6 shows a cross-tabulation of mind-sets by gender, and mind-sets by each other (Top3 or acceptor mind-sets versus Price mind-sets vs. Bot3 or rejector mind-sets). The mind-sets cannot be easily predicted from each. Knowing a person’s gender will not predict to which mind-set a person will belong. Table 6 suggests that a male or a female show similar but not identical distributions of membership in the three mind-sets emerging from clustering the coefficients for Top3. Furthermore, looking at the bottom of Table 6 we see three mind-sets separately created for Bot3, the anti-interest pattern, viz., the elements which clearly DO NOT interest the respondent. The membership patterns differ from the membership patterns of Top3, meaning that knowing something about a respondent does not easily predict knowing their mind-set. A different approach needs to be created to assign new people to the mind-sets.

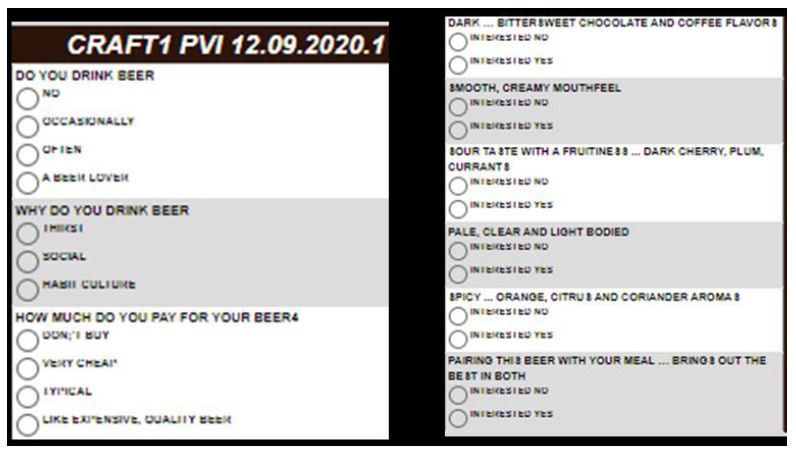

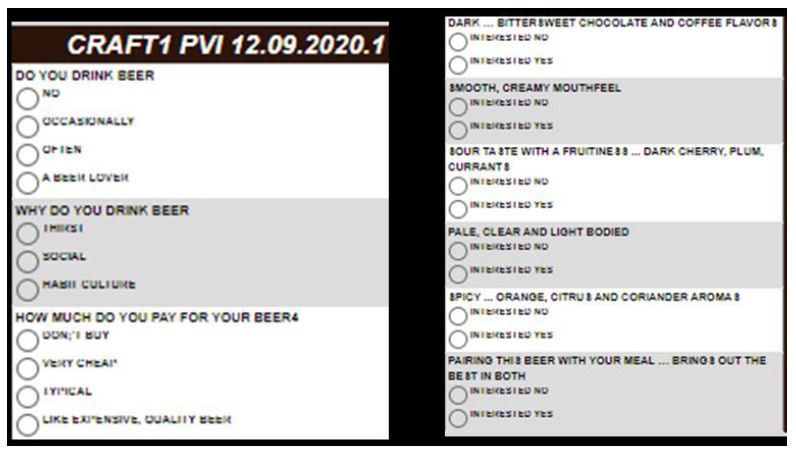

Recent, the authors have suggested that one can create a small set of six questions, based upon the summary data from the study. This is called the PVI, the personal viewpoint identifier. The respondent answers six questions, the questions using the same or similar language to that used to create the mind-sets, the answers presented as a binary scale (NO vs. YES, or similar language). The pattern of the six answers enables the PVI to assign the respondent to the most likely mind-set. The PVI is set up ahead of time, with the underlying mathematics comprising a Monte-Carlo simulation system with added variability to ensure a robust assignment mechanism. The output of the system is feedback to either the researcher or to the user as to the membership in the specific mind-set, as well as the nature of the three mind-sets. Figure 7 shows the web-based form filled out by the respondent. The web-link as of this writing (Winter, 2020) is https://www.pvi360.com/TypingToolPage.aspx?projectid=1262&userid=2018

Figure 7: The PVI for craft beer, showing the three classification questions on the left panel (not used by the PVI for assignment), and the six questions on the right panel used for assignment to one of the three mind-sets emerging from Top3 cluster analysis.

Step 18: Discover Pairwise Interactions Using ‘Scenario Analysis’

An ongoing issue in messaging, one which has never been successfully resolved, is to demonstrate on a repeatable basis that ideas interact with each other, either enhancing each other, or suppressing each other. The notion of interaction makes sense when we think about products, especially foods and beverages, where it is the combination that is liked, not the individual ingredients.

In experimental design, and in the approaches used here, the basic notion is that each element is an independent ‘actor’ in the combination. The independence is assured, at least at a statistical level, by creating vignettes where the same elements appear in different combinations so that they are statistically independent of each other. Does the Mind Genomics systemized permutation covering a great deal of the so-called ‘design space’ (potential combinations), enable the researcher to uncover hitherto unexpected synergies or suppressions of pairs of elements?

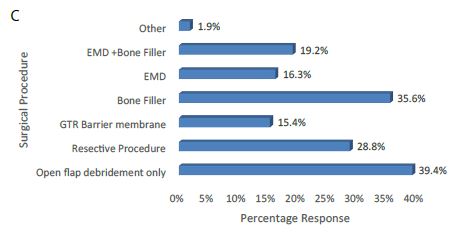

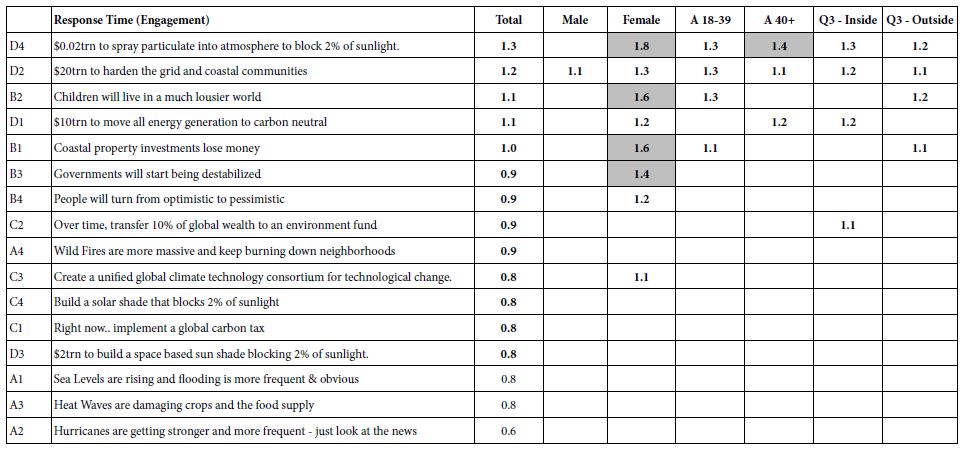

A simple way to discover these interactions builds them in at the start, creating a design which comprises both linear terms (single elements) and known combinations of elements. With six questions and six answers per question, there are 15 pairs of questions, each pair of questions responsible for 36 combinations. This comes to 540 pairwise combinations in the 6×6 Mind Genomics design used here. For the more recent, preferred 4×4 design (four questions, four answers per question) there are 6 pairs of questions, and 16 possible pairs of answers for each pair of questions, viz., 96 pairwise combinations to create and test. The design effort is simply too great, and the typical conjoint approaches cannot deal with the discovery and evaluation of pairwise interactions (Table 9).

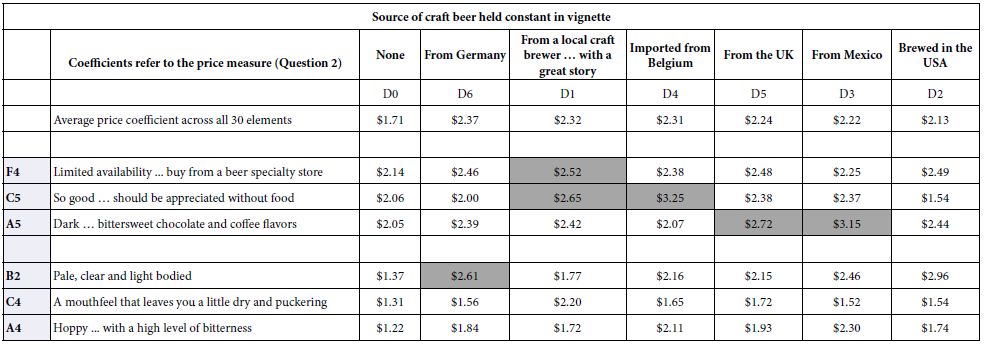

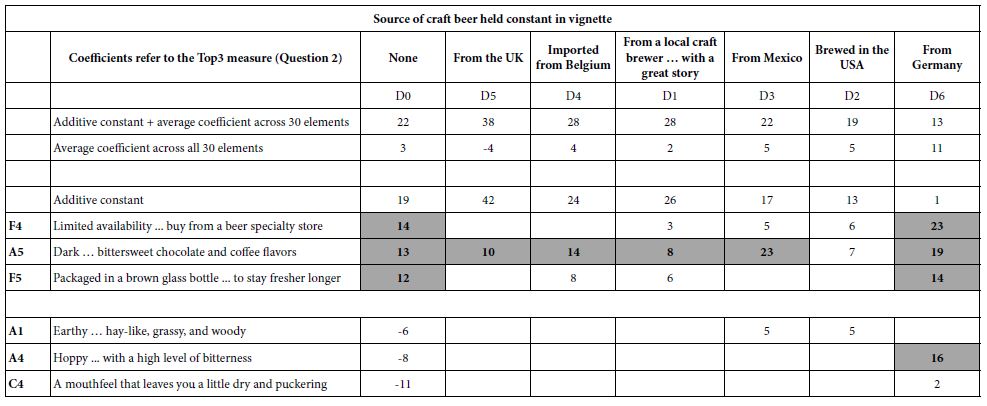

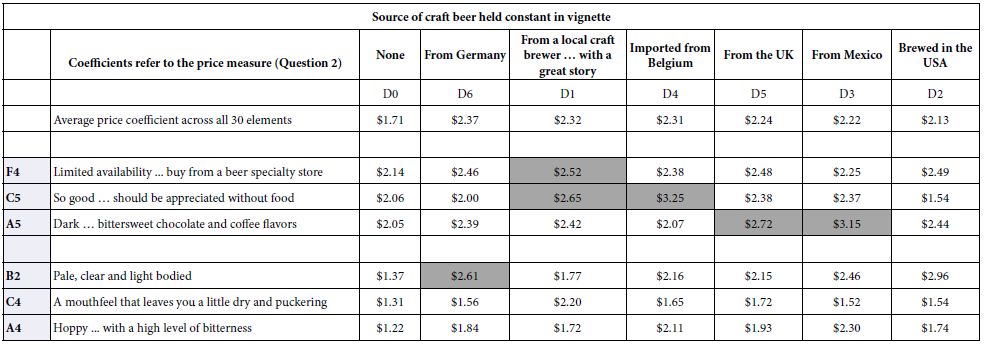

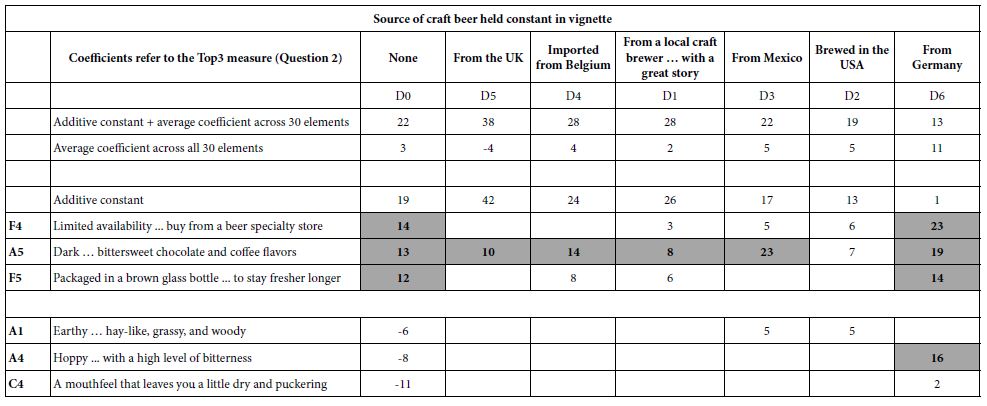

Table 9: Scenario analysis showing how the coefficients of the elements change in terms of Price (Question 2) when the vignette with the element is constructed to have a specific origin provided by Question D.

The task of uncovering pairwise and even higher order interactions can be made simpler, virtually straightforward in the Mind Genomics paradigm [15-17]. Let us illustrate it by looking for interactions of elements with question D, Source of the craft beer. There are six Sources (D1-D6), and a seventh Source (D0) where no Source is mentioned). We create a new variable, called ByD. The new variable, ByD, takes on the values 0 when the vignette has no mention of a source (viz., D does not contribute an element), and takes on the value 1-6 depending upon which specific element appears in the vignette. Thus, the variable ByD stratifies the data matrix.

One sorts data matrix according to the newly created variable, ByD. One then performs seven OLS regressions, one OLS regression for each of the seven strata, respectively. The independent variables are the remaining elements, viz., all starting elements except elements D1-D6. Thus, the independent variables are 30, rather than 36 (A1-A6; B1-B6; C1-C6; E1-E6; F1-F6).

The OLS regression returns with estimates of the 30 coefficients, for each stratum, specifically the stratum where D=0 (does not appear), where D=1 (local brewery with a great story) …D6 (from Germany). The OLS regression estimates the additive constant and the 30 coefficients when the dependent variable is Top3 (interested), and the 30 coefficients without the additive constant when the dependent variable is Price. Synergisms and suppressions appear when one compares the performance of an element in the absence of source (viz., D=0) vs. the performance of the same element in the presence of a specific source (viz., D=1). Synergism emerges when the coefficient with a source is ‘higher’ than the coefficient estimated in the absence of source (viz., D=0).

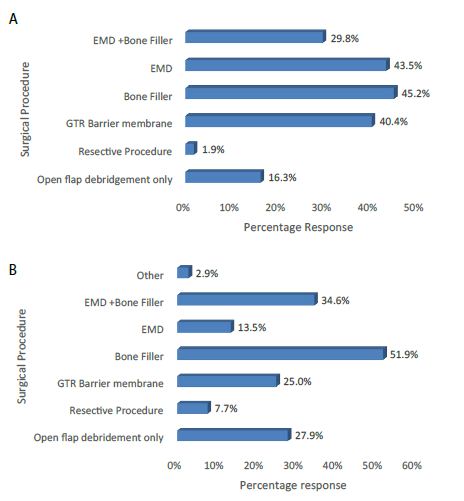

Tables 7 and 8 show the three strongest performing elements and the three weakest performing elements for the total panel, first for the dependent variable being Top3 (interest; Table 7) and for the dependent variable being Price (Table 8).

Table 7: Distribution of respondents into mind-sets based upon gender, by Top3 (what interests them), by Bot3 (what does not interest them), and by Price (what they are willing to pay). The patterns of membership differ.

|

|

Total |

Top M3S1 |

Top3 MS2 |

Top3 MS3 |

| |

Total |

113 |

38 |

40 |

35 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Gender |

Male |

62 |

19 |

24 |

19 |

| Gender |

Female |

51 |

19 |

16 |

16 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Mind-Set |

Top3 MS1 |

38 |

38 |

0 |

0 |

| Mind-Set |

Top3 MS2 |

40 |

0 |

40 |

0 |

| Mind-Set |

Top3 MS3 |

35 |

0 |

0 |

35 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Mind-Set |

Price MS4 |

35 |

6 |

18 |

11 |

| Mind-Set |

Price MS5 |

37 |

25 |

4 |

8 |

| Mind-Set |

Price MS6 |

41 |

7 |

18 |

16 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Mind-Set |

Bot3S7 |

47 |

14 |

21 |

12 |

| Mind-Set |

Bot3S8 |

32 |

11 |

8 |

13 |

| Mind-Set |

Bot3S9 |

34 |

13 |

11 |

10 |

Table 8: Scenario analysis showing how the coefficients of the elements change in terms of Top3 (interest, Question 1) when the vignette with the element is constructed to have a specific origin provided by Question D.

a. The ‘strongest’ performers and the weakest performers are defined by the performance when the coefficients are estimate for the stratum where D=0 (no mention of origin).

b. The columns are sorted by the sum of the additive constant (for Top3, not for price) and the arithmetic average of the 30 coefficients. The first column is always the coefficients for the case when the source is absent from the vignette.

The scenario analysis generates many numbers. It is easiest to see patterns and interactions by eliminating the zero and negative coefficients, to focus on the effect of the different ‘origins’ shown in the columns on a single element (shown in a row). Tables 7 and 8 show evidence of quite strong interactions in some cases, and quite weak interactions in other cases. It is important to keep in mind that these are only estimates of the possible interactions. The negative coefficients are eliminated so we can see cases when the interactions can be very power in the positive direction (Hoppy … with a high level of bitterness, a basically anti-interest element by itself) synergizing with source (Germany).

The synergisms are clearly far stronger for the elements evaluated on interest (question #1), and far weaker for elements evaluate on price. A cursory look at the six elements studied for price (Table 8) reveals, however, that all six of the elements increase in dollar value when they are associated with country of origin. It is discoveries like this, unexpected, which can lead to a new appreciation of craft beer, especially the way people think about it.

Discussion and Conclusions

The sequence of steps presented here produces an exceptionally rich database of information about the mind of the respondent, a database which is obtained within hours and days, a database whose information is achievable, and who metrics, the coefficients, have ratio-scale values, and are comparable from study to study, from topic to topic, so long as the rating scales are same.

In the spirit of Mind Genomics, the discussion is brief. The data essentially present the whole story. There is no need to plug holes in the literature, to falsify hypotheses and conjectures. There may be hypotheses to be tested with the data, but the data serves as an exploration of a topic, as an understanding of the mind of people respect to something from their ‘everyday’ experience.

Of interest from the point of view of science of the mind and decision making is the difference within the same person when the person deals with price versus when the person deals with emotion. The former, Homo Economicus, is well recognized as an entity in the scientific literature. The latter, Homo Emotionalis, is just beginning to be studied (although consumer researchers have long known about the importance of Homo Emotionalis in decision making. Those in government and public policy are just now beginning to understand the role of emotion and feeling in policy, although it has always been present, recognized perhaps but not acknowledged [18-20].

The logical next steps for Mind Genomics vary by the goal and vision of the researcher. The world of beer, of alcoholic beverages lies open for a concerted research effort. Beyond the world of the knowledge of beer is the marketing, and the benefits conferred on the marketer by knowing the three mind-sets, and how to assign a new person to a mind-set using the PVI. Inserting the PVI into digital marketing, e.g., as a game, might allow the marketer to drive the respondent’s online inquiry into a landing page appropriate for the mind-set.

At the level science, however, we have a paradigm to acquire and analyze data, and a template to store and present the results. One might imagine the happy day in a few years when these studies are done as the standard way of exploring new topics, not so much in a piecemeal way to falsify or not falsify hypotheses, but rather simply to create the aforementioned ‘wiki of the mind’ as a living, dynamic encyclopedia of life as it is experienced.

References

- Acitelli T, Magee T (2017) The audacity of hops: The history of America’s craft beer revolution. Chicago Review Press.

- Chapman NG, Lellock JS, Lippard CD (2017) Untapped: Exploring the cultural dimensions of craft beer. West Virginia University Press.

- Elzinga KG, Tremblay CH, Tremblay VJ (2015) Craft beer in the United States: History, numbers, and geography. Journal of Wine Economics 10: 242.

- Lamertz K, Foster WM, Coraiola DM, Kroezen J (2016) New identities from remnants of the past: An examination of the history of beer brewing in Ontario and the recent emergence of craft breweries. Business History 58: 796-828.

- Orth UR, Lopetcharat K (2006) Consumer-based brand equity versus product-attribute utility: A comparative approach for craft beer. Journal of Food Products Marketing 11: 77-90.

- Rice J (2016) Professional purity: Revolutionary writing in the craft beer industry. Journal of Business and Technical Communication 30: 236-261.

- Moskowitz HR (2012) ‘Mind genomics’: The experimental, inductive science of the ordinary, and its application to aspects of food and feeding. Physiology & behavior 107: 606-613. [crossref]

- Moskowitz HR, Silcher M (2006) The applications of conjoint analysis and their possible uses in Sensometrics. Food Quality and Preference 17: 145-165.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A, Beckley J, Ashman H (2006) Founding a new science: Mind genomics. Journal of Sensory Studies 21: 266-307.

- Porretta S, Gere A, Radványi D, Moskowitz H (2019) Mind Genomics (Conjoint Analysis): The new concept research in the analysis of consumer behaviour and choice. Trends in Food Science & Technology 84: 29-33.

- Shareff R (2007) Want better business theories? Maybe Karl Popper has the answer. Academy of Management Learning & Education 6: 272-280.

- Hargrave M (2018) Hedonic pricing. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/h/hedonicpricing.asp

- Kaufman L, Rousseeuw PJ (2009) Finding groups in data: an introduction to cluster analysis (Vol. 344). John Wiley & Sons.

- Tuma MN, Decker R, Scholz SW (2011) A survey of the challenges and pitfalls of cluster analysis application in market segmentation. International Journal of Market Research 53: 391-414.

- Ewald J, Moskowitz H (2007) The push-pull of marketing and advertising and the algebra of the consumer’s mind. Journal of sensory studies 22: 126-175.

- Gofman A, Moskowitz H (2010) Isomorphic permuted experimental designs and their application in conjoint analysis. Journal of Sensory Studies 25: 127-145.

- Gofman A (2006) Emergent scenarios, synergies and suppressions uncovered within conjoint analysis. Journal of Sensory Studies 21: 373-414.

- Archer MS (2013) Homo economicus, Homo sociologicus and Homo sentiens. In Rational choice theory 46-66.

- Markwica R (2018) Emotional choices: How the logic of affect shapes coercive diplomacy. Oxford University Press.

- Meier AN (2018) Homo Oeconomicus Emotionalis?: Four Essays in Applied Microeconomics (Doctoral dissertation, Wirtschaftswissenschaftliche Fakultät der Universität Basel).