Introduction

Intermetatarsal neuromas, known by their eponym as Morton’s neuromas, are a common painful forefoot pathology seen in the foot and ankle clinic. The nomenclature of this condition is misleading. The term “neuroma” refers to a non-degenerative nerve injury. The condition clinicians most often describe in a “Morton’s neuroma” is more accurately described as a perineural fibrosis of the plantar interdigital nerve leading to entrapment of this nerve [1]. Surgical treatment varies from entrapment release to full neurectomy [2]. Post-operative pathology review of neurectomized tissue rarely demonstrates axonal degeneration and collagen proliferation [3]. Those changes are the pathophysiological markers associated with nerve injury that lead to true neuroma formation. The authors, therefore, recommend changing the common name of the condition from “intermetatarsal neuroma” to interdigital nerve entrapment to better define the disease. The aim of this review is to present treatment schemes seen in “Morton’s” diagnosis, and to suggest an algorithm which may improve patient outcome.

Anatomy and Biomechanics

Intermetatarsal nerve entrapment is classically found in the third intermetatarsal space, but this condition can affect any of the four intermetatarsal nerves in the foot [4]. The rate of occurrence in the third metatarsal space is higher due to the anatomy of the foot [5]. First, the innervation of the foot begins with the tibial and common fibular (peroneal) nerves [6]. As the tibial nerve courses distally past the knee joint, its motor fibers to the posterior compartment of the leg and enters the tarsal tunnel at the level of the medial malleolus [7]. The tibial nerve then typically bifurcates just distal to the laciniate ligament at the tarsal tunnel to form both the medial and lateral plantar nerves [8]. Those two nerves work in tandem to provide sensation to the plantar aspect of the foot form their proper digital branches distally. At the most common area between the medial and lateral plantar nerves, there is a medial communicating branch between them at the level of the third intermetatarsal space. This is the actual nerve which becomes entrapped and that causes the clinical signs and symptoms for this condition [9].

There are certain foot types which are more likely to become entrapped. The medial longitudinal arch height typically defines whether a foot is in pes planus or pes cavus, clinically [10]. As the medial longitudinal arch is depressed, this is usually in compensation for a rearfoot valgus [11]. There is increased congruity of the three facets of the subtalar joint with rearfoot valgus positioning. This in turn increases the flexibility of all joints about the midfoot. The increase in flexibility is an evolutionary advantage for the foot so it may adapt against uneven terrain. There is an unfortunate consequence for this adaptability. There is increased motion in-between the medial and lateral columns of the foot.

The medial column of the foot is defined as the combination of the medial, intermediate and lateral cuneiform bones and their associated first, second and third rays of the forefoot. The lateral column of the foot is defined as the cuboid bone and its articulation with the fourth and fifth rays of the forefoot. In flexible pes planus conditions, there is an increase in motion in-between the third and fourth metatarsals [12]. This motion becomes pathological when the medial communicating branch between the medial and lateral plantar nerves becomes entrapped. The entrapment results in perineural fibrosis as compensation to prevent axonal damage [13]. Due to the nature of the pathological mechanics and the common occurrence of pes planus, it is more common to see third intermetatarsal nerve incarceration versus the surrounding intermetatarsal spaces.

Physical Examination of Intermetatarsal Nerve Entrapment

Third intermetatarsal space nerve entrapment is known to be found in 50-87 out 100,000 people, and women are more commonly affected versus men [14]. Typical symptoms the patient may present in cases of Morton’s intermetatarsal/ interdigital nerve entrapment are often described by the patient as a burning, shooting pain or numbness/ paresthesia between the third and fourth metatarsal heads that may radiate distally toward the corresponding toes in up to 60% of cases and may also radiate proximally [15]. The patient may also be described as one feeling as though they are stepping on a pebble or have the sensation of a “rolled up sock” in the proximal forefoot area.

As with diagnosis of other nerve entrapments, Morton’s intermetatarsal nerve entrapment is largely clinically based. The high variability of presentation between patients encourages a clinical diagnosis based on symptoms and physical examination findings, rather than staunch guidelines. Symptoms may include focal tenderness and tinel’s sign. The presence of Mulder’s sign clicking (compression of forefoot while plantar interspace is palpated) and pain with interspace compression while performing this test are often positive findings [16]. A Lachman’s test is often used for evaluation of the differential diagnoses of capsulitis and plantar plate rupture versus intermetatarsal nerve entrapment [17].

A thorough biomechanical evaluation and physical examination are warranted with presence of Morton entrapment symptoms to help identify biomechanical influences as well as elucidate other pathologies that may be unrecognized yet contributing to symptoms, such as tarsal tunnel syndrome. As with any pathology, complete diagnosis and treatment of underlying conditions will help to prevent unnecessary recurrence. Radiographic evaluation with particular emphasis of weightbearing views of the foot should be utilized to further rule out other pathologies contributing towards metatarsalgia, such as an abnormal elongated metatarsal parabola or possible contribution of cavus foot and equinus deformity. Varying options have been noted on the effectiveness of MRI findings in symptomatic patients. Ultrasound is highly recommended and may be optimal for diagnosis of neuromas smaller than 5mm [18], however it is noted that this imaging technique is operator dependent. A recent meta-analysis has concluded that ultrasonography has been found equivalent to MRI for diagnostic value in Morton’s intermetatarsal entrapments [19]. Although these visual modalities have been advocated, one study comparing preoperative imaging with surgical findings noted approximately half of the neuromas were missed by ultrasound and MRI.

Differentials to consider may include degenerative changes to the metatarsal phalangeal joint, plantar pad, Metatarsal stress fracture, Freiberg’s infarction, other foot nerve pathologies, such as lateral or medial plantar nerve lesions and tarsal tunnel syndrome as well as presence of soft tissue masses, tumors and cystic changes.

Conservative Treatment for Morton’s Entrapment

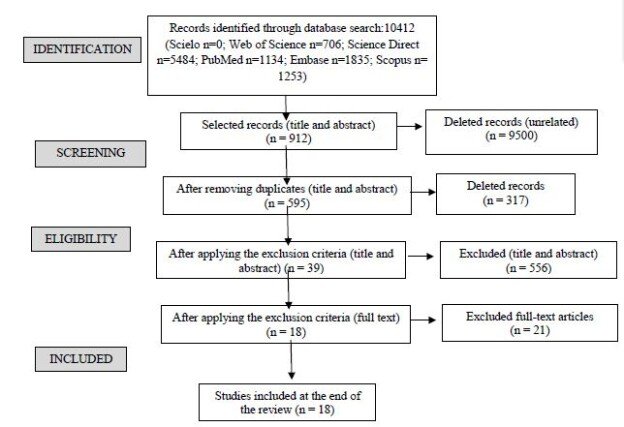

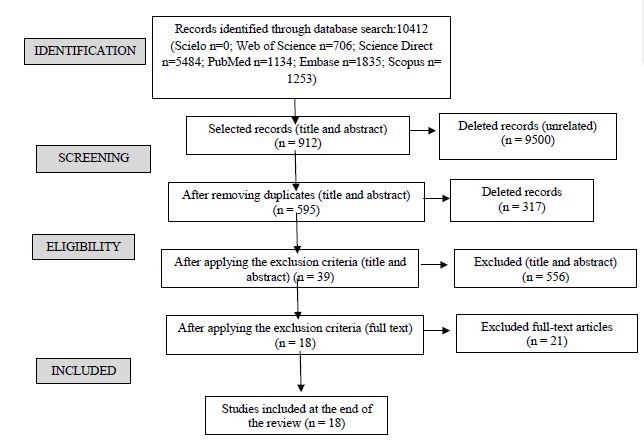

Conservative (non-surgical) interventions for treatment of Morton’s entrapment include orthoses and shoe gear modification, corticosteroid and alcohol injection, extracorporeal shockwave therapy, radiofrequency ablation, cryoablation, capsaicin injection, botulinum toxin, and laser therapy [20]. A systematic review for treatment of Morton’s neuroma reveals conservative treatment can be effective. Use of orthoses leads to improvement in nearly 50% of patients. Radiofrequency ablation was found to be more effective as well as associated with less frequent complications compared to injections including alcohol and corticosteroids. This review concluded however, that most successful treatments included operative treatment [21].

Injection efforts are often utilized when the patient presents with high levels of pain and symptoms and may help relieve symptoms temporarily and are quite effective in the short term. The most common utilized agents include alcohol and corticosteroids. Injectables have been described as particularly useful while concomitantly addressing biomechanical contributions, which includes shoe gear modification and use of custom orthoses. The use of corticosteroids is associated with plantar plate rupture as well as deterioration of the joint capsule and is typically recommended to have a limitation of three treatments per year. Ethanol injection has poor success rates reported and has even been determined as not an effective treatment for interdigital neuroma but has the noted advantage of available repetition of procedure when compared to corticosteroid [22].

Morton’s intermetatarsal nerve entrapment has been likened to carpal tunnel syndrome in the upper extremity, a similar nerve entrapment condition of the median nerve. Conservative efforts for treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome with wrist splinting and steroid injections are effective in the short term and recommended if symptom duration is less than 3 months with absence of sensory impairment, but only 10% remain asymptomatic within one year [23]. Additionally, a retrospective study has demonstrated that increased utilization of corticosteroid application has led to worse long-term outcome in surgical carpal tunnel release [24,25]. Controversy remains in direct to surgery vs local corticosteroid injection with multiple elements to consider [26].

Surgical Approaches and Considerations for Morton’s Entrapment

Surgical treatment for intermetatarsal nerve entrapment should be considered when painful symptoms have not been adequately relieved by conservative methods. The underlying pathologic etiology contributing to developed condition must be considered for optimal outcome. Of particular note, the forefoot loading effects of equinus as well as the influence of the metatarsal parabola potential for increased plantar pressures should be evaluated for potential effects leading to chronic repetitive microtrauma to the forefoot. Bauer has been previously advocated for adjunctive metatarsal osteotomies to be performed with release of deep transverse intermetatarsal ligament, however this should only be performed as necessary and in some cases peak plantar forefoot pressures and contact time remain unaffected and are not elevated [27].

Surgical external neurolysis of the common plantar interdigital nerve (decompression of nerve) should be considered following correction of biomechanics. This procedure has a noted high success and low complication rate. This has been described in both open and endoscopic release techniques. The endoscopic approach results with 86% of patients having excellent or good results and allows for the advantage of minimal tissue disruption and possible earlier return to activity as demonstrated by Barrett and Walsh [28]. The approach to an open external neurolysis of the intermetatarsal nerve will be discussed further. Plantar and dorsal incisions have been described, with the dorsal linear approach providing the advantage of decreased painful scar formation as well as early ambulation of the patient. The plantar approach can be performed in a transverse or longitudinal incision. The plantar transverse may be performed on the non-weightbearing aspect of the foot, allowing for ideal visualization for nerve identification, exposure for adjacent intermetatarsal nerve procedures, and allows for immediate weightbearing.

This procedure should be performed under loupe magnification to allow for optimal visualization of nerve tissue. The patient is placed on the operative room table in a supine position with placement of a well-padded ankle tourniquet. Utilizing aseptic technique, the lower extremity is scrubbed, prepared and draped. Next, topographic anatomic landmarks are drawn including the heads of the third and fourth metatarsals at the metatarsal phalangeal joint and their respective metatarsal shafts. The surgical incisional site should be planned midline between these structures, extended distally to the corresponding webspace. Utilizing a #15 blade, the longitudinal incision is performed to the level of dermis, and next tenotomy scissors with blunted tips are utilized with careful dissection utilizing atraumatic technique is performed with care to avoid injury to superficial nerve branches and vascular structures. Bipolar electrocautery is utilized as necessary to assist with hemostasis to help reduce hematoma formation, as well as provides a more controlled and limited destruction of tissue with cauterization. Retraction to obtain optimal surgical field visualization should be performed by an assistant or with an atraumatic Weitlander or lamina spreader placed deep to the metatarsal heads. The dorsal fascia is then incised, and deeper dissection is performed until the transverse intermetatarsal ligament is identified. This structure is then isolated and elevated with assistance of placing a curved hemostat or Senn retractor deep to this structure, which is then incised along its entire length, in an effort to protect deeper structures. The intermetatarsal nerve lies deep to the transverse intermetatarsal ligament. Other constricting structures should be evaluated visually as well as palpated digitally, and the nerve should be freed from adhesions both distally as well as proximally to the bifurcation with careful blunt dissection efforts. This is continued throughout the entire surgical field to maximally reduce contributing factors of nerve entrapment. The surgical site is re-evaluated to ensure all constricting elements have been removed, and then irrigated with normal sterile saline. If biological adjunctive products, such as amniotic membrane, are utilized they should be placed along the released structure. Minimal subcutaneous tissue closure with an absorbable suture should be performed and primary skin closure is then performed with nonabsorbable suture and dry sterile dressing is then applied. Of note, in the event of suboptimal patient satisfaction with use of neurolysis (decompression) as a first line of surgical treatment, excisional neurectomy should be considered in subsequent treatment of the surgical algorithm.

Excisional neurectomy (denervation) proximal to the deep transverse intermetatarsal ligament has been well described and it is the authors’ opinion that this procedure should be considered following the decompression efforts. Wolfort and Dellon have advocated for treatment with nerve resection in combination with the implantation of the proximal end of the intermetatarsal nerve into muscle belly, reporting 80% excellent relief of symptoms29. This is most often performed with the dorsal longitudinal incisional approach. A lazy S type incision may be considered for cases with adjacent identified nerve entrapment, in an effort to increase exposure of surgical sites with a single incision. Layered anatomic dissection should be performed in a similar manner as described for neurolysis. Upon freeing the nerve, attention is directed to the proximal portion of the operative site. Mild tension is placed distally and at this point is excised just proximal to the metatarsal head utilizing a sterile tongue depressor cut in a transverse/perpendicular manner with a new blade to ensure sharp and clean transection of nerve with the goal of limiting axonal growth. Next, the freed proximal portion of the intermetatarsal nerve is then transposed proximally and placed into adjacent intrinsic muscle belly with minimal tension. The nerve is then loosely affixed via a windowing technique into the muscle created with hemostats and secured via an epineurial stitch. Excision may lead to formation of a true “stump neuroma”. Nerve excision has varying success reported up to 85%, however good or excellent long term results have been noted in only 50% of patients in a large retrospective cohort study by Womack, and 40% of patients obtaining poor results [29,30].

Revisional Surgical Approaches

Revisional surgeries often have less than optimal results; consideration of contributing factors to symptoms should be considered. These symptoms can take up to one year following surgical excision. There is a high prevalence of tarsal tunnel syndrome in conjunction with painful recurrent interdigital neuromas [29], and through physical examination is warranted when addressing recurrent neuromas.

Due to the increased likelihood of suboptimal results in cases of recurrence, in cases of poor surgical candidates, a less invasive approach to consider may be use of radiofrequency ablation. This destructive process includes use of radiofrequency energy which provides thermic electrocoagulation to the tissue surrounding the tip of the probe. Three cycles of treatment is advocated to increase efficacy when compared to two [30].

Surgical intervention, which may be selected often, includes the plantar approach surgical neurectomy of the intermetatarsal nerve. In this procedure, care should be taken to ensure eversion of incisional closure to minimize painful scarring with delayed weight bearing to avoid dehiscence. The use advanced techniques and modalities include nerve capping with the goal to reduced size and number of axons sprouting from transection of nerve, nerve transposition and implantation into muscle, nerve grafting, peripheral nerve stimulator with possible use of amniotic products.

Conclusion

Interdigital/intermetatarsal nerve entrapment or Morton’s neuromas are common forefoot pathologies that are most often attributed to an underlying entrapment condition of the nerve. This can be described as interdigital /intermetatarsal nerve neuralgia secondary to perineural fibrosis. Persisting symptoms warrant through physical examination, with emphasis on biomechanical contribution. Imaging may be helpful in diagnosis, particularly the use of radiographs and ultrasonography. Both conservative and surgical means of treatment have been recommended for the treatment of intermetatarsal/ interdigital entrapment, which remains somewhat controversial. Multiple studies have been conducted to ascertain the effectiveness of non-surgical versus surgical treatment of this condition [1,3,7]. Many studies have demonstrated improvement in symptoms over 80% with surgical intervention. Non-surgical efforts should be attempted prior to any surgical intervention to avoid possible complications, with surgery to be attempted upon failure of non-surgical intervention.

Excision remains the most common surgical management in treatment of Morton’s intermetatarsal nerve entrapment [31]. Due to the true nature of this condition having an underlying compression syndrome, neurolysis efforts are warranted and should strongly be considered in the first line of surgical procedures to address this issue. Similar outcomes have been established with both neurolysis and excisional efforts.

References

- Matthews BG, Hurn SE, Harding MP, Henry RA, Ware RS (2019) The effectiveness of non-surgical interventions for common plantar digital compressive neuropathy (Morton’s neuroma): A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Foot Ankle Res 12: 12. [crossref]

- Kasparek M, Schneider W (2016) Transection of the deep metatarsal transverse ligament in Morton’s neuroma surgery does not increase risk of splayfoot development. International Orthopaedics (SICOT) 40: 953-957. [crossref]

- Bhatia M, Thomson L (2020) Morton’s neuroma-Current concepts review. Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma 11: 406-409. [crossref]

- Levitsky KA, Alman BA, Jevsevar DS, Morehead J (1993) Digital nerves of the foot: Anatomic variations and implications regarding the pathogenesis of interdigital neuroma. Foot & Ankle 14: 208-214. [crossref]

- Matsumoto T, Chang SH, Izawa N, Ohshiro Y, Tanaka S (2016) Interdigital neuroma in the second intermetatarsal space associated with metatarsophalangeal joint instability. Case Reports in Orthopedics 2016: 1-6. [crossref]

- Andreasen Struijk LNS, Birn H, Teglbjærg PS, Haase J, Struijk JJ (2010) Size and separability of the calcaneal and the medial and lateral plantar nerves in the distal tibial nerve. Anat Sci Int 85: 13-22.

- Meares C, Dusseldorp J (2020) Review of the efficacy of tibial nerve decompression in the management of diabetic feet. Clinical Neurophysiology 131: 1-2.

- Iborra A, Villanueva M, Sanz-Ruiz P (2020) Results of ultrasound-guided release of tarsal tunnel syndrome: A review of 81 cases with a minimum follow-up of 18 months. J Orthop Surg Res 15: 30. [crossref]

- Govsa F, Bilge O, Ozer MA (2005) Anatomical study of the communicating branches between the medial and lateral plantar nerves. Surg Radiol Anat 27: 377-381. [crossref]

- Lee JH, Cynn HS, Yoon TL, Choi SA, Kang TW (2016) Differences in the angle of the medial longitudinal arch and muscle activity of the abductor hallucis and tibialis anterior during sitting short-foot exercises between subjects with pes planus and subjects with neutral foot. BMR 29: 809-815. [crossref]

- Tang SFT, Chen CH, Wu CK, Hong WH, Chen KJ, et al., (2015) The effects of total contact insole with forefoot medial posting on rearfoot movement and foot pressure distributions in patients with flexible flatfoot. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 129: 8-11. [crossref]

- Gougoulias N, Lampridis V, Sakellariou A (2019) Morton’s interdigital neuroma: Instructional review. EFORT Open Reviews 4: 14-24. [crossref]

- Wang ML, Rivlin M, Graham JG, Beredjiklian PK (2019) Peripheral nerve injury, scarring, and recovery. Connective Tissue Research 60: 3-9. [crossref]

- DeHeer PA, Nanrhe AP, Michael SR, Standish SN, Bhinder CD, et al., (2020) Gender correlation to the prevalence of pedal neuromas in various interspaces-a retrospective study. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association. [crossref]

- Owens R, Gougoulias N, Guthrie H, Sakellariou A (2011) Morton’s neuroma: Clinical testing and imaging in 76 feet, compared to a control group. Foot and Ankle Surgery 17: 197-200. [crossref]

- Cloke DJ, Greiss ME (2006) The digital nerve stretch test: A sensitive indicator of Morton’s neuroma and neuritis. Foot and Ankle Surgery 12: 201-203.

- Bergeron MC, Ferland J, Malay DS, Lewis SE, Burkmar JA, et al., (2019) Use of metatarsophalangeal joint dorsal subluxation in the diagnosis of plantar plate rupture. The Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery 58: 27-33.

- Fazal MA, Khan I, Thomas C (2012) Ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of morton’s neuroma. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association 102: 184-186.

- Bignotti B, Signori A, Sormani MP, Molfetta L, Martinoli C, et al., (2015) Ultrasound versus magnetic resonance imaging for Morton neuroma: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol 25: 2254-2262. [crossref]

- Thomson L, Aujla RS, Divall P, Bhatia M (2020) Non-surgical treatments for Morton’s neuroma: A systematic review. Foot and Ankle Surgery 26: 736-743. [crossref]

- Valisena S, Petri GJ, Ferrero A (2018) Treatment of Morton’s neuroma: A systematic review. Foot and Ankle Surgery 24: 271-281. [crossref]

- Espinosa N, Seybold JD, Jankauskas L, Erschbamer M (2011) Alcohol sclerosing therapy is not an effective treatment for interdigital neuroma. Foot Ankle Int 32: 576-580 [crossref]

- Graham RG, Hudson DA, Solomons M, Singer M (2004) A prospective study to assess the outcome of steroid injections and wrist splinting for the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 113: 550-556. [crossref]

- Vahi PS, Kals M, Kõiv L, Braschinsky M (2014) Preoperative corticosteroid injections are associated with worse long-term outcome of surgical carpal tunnel release: A retrospective study of 174 hands with a mean follow-up of 5.5 years. Acta Orthopaedica 85: 102-106. [crossref]

- Bland JDP, Ashworth NL (2016) Does prior local corticosteroid injection prejudice the outcome of subsequent carpal tunnel decompression? J Hand Surg Eur Vol 41: 130-136. [crossref]

- Naraghi R, Slack-Smith L, Bryant A (2018) Plantar pressure measurements and geometric analysis of patients with and without morton’s neuroma. Foot Ankle Int 39: 829-835. [crossref]

- Barrett SL, Walsh AS (2006) Endoscopic decompression of intermetatarsal nerve entrapment. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association 96: 19-23.

- Womack JW, Richardson DR, Murphy GA, Richardson EG, Ishikawa SN (2008) Long-Term evaluation of interdigital neuroma treated by surgical excision. Foot Ankle Int 29: 574-577. [crossref]

- Wolfort SF, Lee Dellon A (2001) Treatment of recurrent neuroma of the interdigital nerve by implantation of the proximal nerve into muscle in the arch of the foot. The Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery 40: 404-410. [crossref]

- Brooks D, Parr A, Bryceson W (2018) Three cycles of radiofrequency ablation are more efficacious than two in the management of morton’s neuroma. Foot & Ankle Specialist 11: 107-111. [crossref]

- Villas C, Florez B, Alfonso M (2008) Neurectomy versus Neurolysis for Morton’s Neuroma. Foot Ankle Int 29: 578-580. [crossref]