Abstract

Pituitary abscess (PA) caused by an infectious process is a rare cause of Sellar mass. The clinical features and radiological appearance of PA as an intra- or supra-sellar mass are similar to many other pituitary lesions, and so they are often misdiagnosed as pituitary tumor.

70% of cases occur in a previously healthy pituitary gland. These are classified as primary pituitary abscesses, persumbly secondary to either hematogenous spread or as an extension from an adjacent infective focus such as meningitis, sphenoid sinusitis, Cavernous sinus thrombophlebitis or contaminated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) fistula.

The rest are secondary abscesses, and arise from pre-existing lesions, such as an adenoma, apoplexy in a tumor, a craniopharyngioma, or a complicated Rathke’s cleft cyst and lymphoma. The risk factors are for PA are immunosuppression, previous irradiation or surgical procedures to the pituitary gland [1].

In almost 50% of cases, the pathogenic microorganism causing the infection is not isolated. A history of recent meningitis sinusitis or head surgery can be the source [2].

Correct diagnosis before surgery is difficult and is usually confirmed intra- or post-operatively. The early surgical intervention allows appropriate antibiotic therapy and hormone replacement resulting in reduced mortality and morbidity. A long term follow-up is recommended because of the high risk of recurrence and of postoperative hormone deficiencies.

Keywords

Pituitary abscess, Papilledema, Panhypopituitarism, Rathke’s cleft cyst, Propionibacterium acnes

Introduction

A pituitary abscess (PA) represents 0.2%-0.6% of all pituitary lesions and can be life threatening. It can have a prolonged disease course. The first case was reported by Heslop in 1848, and so far, <300 cases have been reported worldwide [3]. It is an infectious process that presents as a mass in the Sella. Clinical features and the radiological appearance of the PA as an intra or suprasellar mass are similar to many other pituitary lesions, so it is often misdiagnosed as a cystic pituitary tumor, craniopharyngioma, and Rathke’s cyst. It can be life-threatening if not appropriately diagnosed or treated, and the outcome is difficult to predict. Fortunately, the majority of the cases have a chronic course. The disease has a higher prevalence in females between the age of 12 to 76 years. The average period it takes to diagnose from the onset of symptoms is around 8 years.

PA can occur as a primary disease or can be secondary to infections caused by either hematogenous spread or as an extension from an adjacent infected tissue such as meningitis, sphenoid sinusitis, Cavernous sinus thrombophlebitis or contaminated cerebrospinal fluid fistula 70% of cases occur in a previously healthy pituitary gland. These are classified as primary pituitary abscesses, and the rest are secondary abscesses that arise from pre-existing lesions, such as an adenoma, apoplexy in a tumor, a craniopharyngioma or a complicated Rathke’s cleft cyst and lymphoma [4].

In almost 50% of cases, the pathogenic microorganism causing the infection cannot be isolated. A history of recent meningitis sinusitis or head surgery can be the source [2].

Correct diagnosis before surgery is difficult and is usually confirmed intra- or post-operatively. The early surgical intervention allows appropriate antibiotic therapy and hormone replacement resulting in reduced mortality and morbidity. A long term follow-up is recommended because of the high risk of recurrence and postoperative hormone deficiencies.

We present 2 cases of pituitary abscess in young women. One presented with bilateral papilledema and the other with panhypopituitarism. Both had a sellar mass on an MRI scan, and the diagnosis was made intra-operatively. Microbiological culture in both cases was positive for Propionibacterium acnes (P.acnes). P.acnes is a gram-positive organism, a part of the normal skin microbe. This organism is most commonly isolated from wounds following craniotomies after Staphylococcus aureus and streptococcus epidermidis. Low-grade infections can manifest between 3-36 months.

Case 1

A 14-year old South Asian girl presented with a one-month history of worsening frontal headaches that occurred daily, associated with vomiting, nausea, lethargy, photophobia, and sleep disturbance. Aside from well-controlled asthma, she has been previously healthy. There was no recent travel history or infectious contacts. On examination, she appeared alert and active. She had bilateral papilledema, suggesting raised intracranial pressure (ICP). She was apyrexial and systemically well. Her cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan revealed a soft tissue mass in the pituitary fossa extending up towards the optic chiasm, with mild edema in the optic nerve and tracts. The scan also showed an enlarged pituitary gland and thickened stalk. The findings suggest an inflammatory process like hypophysitis, particularly Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) because of her age. There were no other features of LCH. She had a normal liver US and skeletal survey. She had no symptoms of Diabetes insipidus. Her pituitary hormones were normal, including the stimulated cortisol. Her Prolactin was elevated. Her serum sodium and osmolality were normal. Her ESR was slightly raised, but autoantibodies, serum tumor markers, ACE, and the Quantiferon tuberculosis test were negative. Her IgG4 subclass was normal (Table 1). The formal ophthalmology review did not show evidence of bilateral papilledema. Her symptoms improved with oral analgesics, and steroid treatment was not initiated.

Table 1: Results at initial presentation.

Short Synacthen test

| Time | T=0 | T-30 | T=60 |

| Cortisol (nmol/L) | 186 | 452 | 594 |

Baseline tests

| Test | Result | Normal range |

| IGF-1(nmol/L) | 47.9 | 18.3 to 63.5 |

| TSH (mU/L) | 1.62 | 0.51-4.3 |

| T4 (pmol/L) | 13.3 | 10.8-19 |

| LH (IU/L) | 4.3 | Follicular phase 2-13

Mid cycle 14-6 Luteal phase 1-11 |

| FSH (IU/L) | 1.8 | Follicular phase 4-13

Mid cycle 5-22 Luteal phase 2-8 Postmenopause>25 |

| ACTH (ng/L) | <3 | 0-50 |

| Prolactin (mU/L) | 806 | 102-496 |

| Serum Na mmol/L | 144 | 133-146 |

| Serum Osmolality mOsmo/Kg | 293 | 282-300 |

| Random Urine Osmolality mOsmo/Kg | 475 | 100-1400 |

| LDH (u/L) | 188 | 120 to 300 |

| HCG (IU/L) | <1 | 0-1 |

| alpha Fetoprotein (kU/L) | 1 | 0-10 |

| C-Reactive protein (mg/L) | 1.5 | 0-5 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 28 | 1-12 |

| Complement C3 (g/l) | 1.1 | 0.75-1.65 |

| Complement C4 (g/l) | 0.29 | 0.14-0.54 |

| Antinuclear antibodies | Negative | |

| Angiotensin convert enzyme (U/L) | 42 | 16-85 |

| IgG4 (g/L) | 0.04 | 0-1.3 |

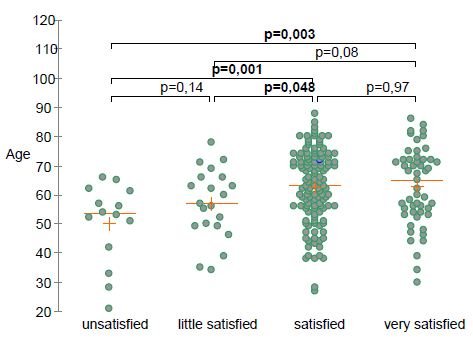

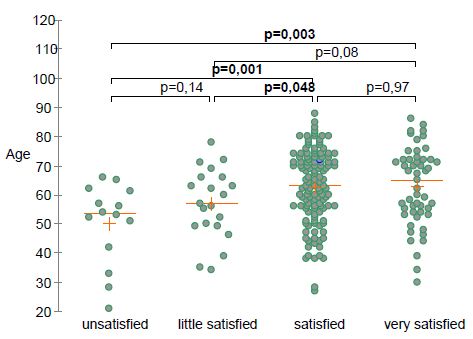

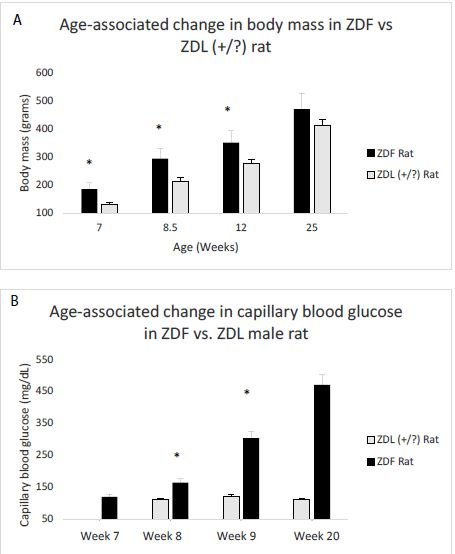

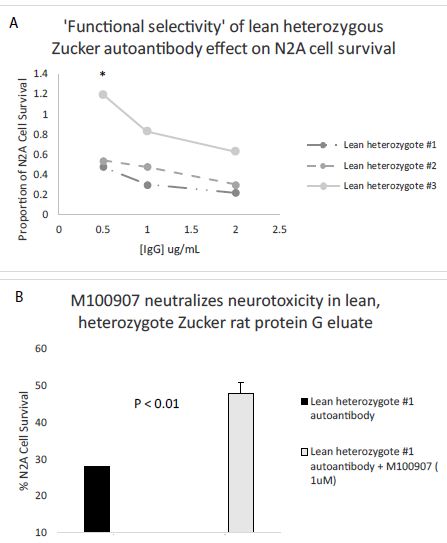

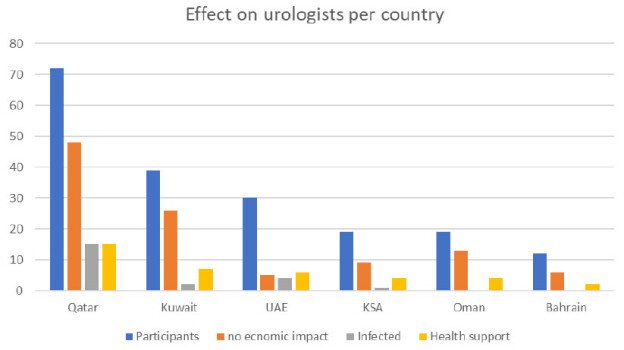

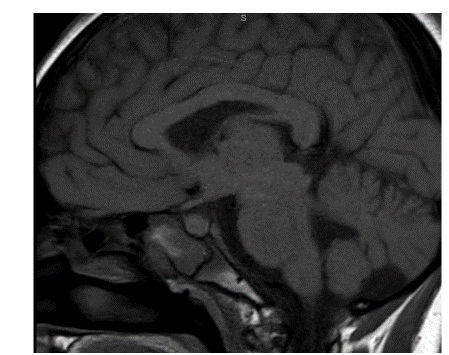

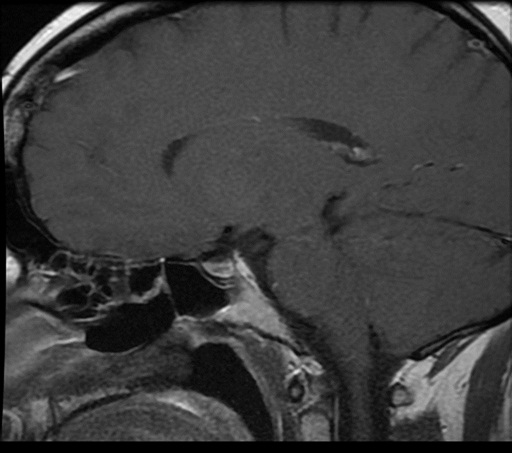

A repeat MRI scan 3 months later discussed in a multidisciplinary meeting was reported to suggest Rathke’s cleft cyst abscess/ Pituitary abscess (Figures 1 and 2). She underwent a trans-sphenoidal endoscopic pituitary biopsy for diagnosis. The appearances suggested a Rathke’s left cyst and a pituitary abscess. Immunostaining for ACTH, FSH, LH, growth hormone, TSH and Prolactin, chromogranin, synaptophysin, and collagen IV was consistent with anterior pituitary tissue. Microbiological culture on prolonged incubation was positive for Propionibacterium with no acid-fast bacilli growth. TB culture was also negative. She received a 6-week course of antibiotics, including 2 weeks of intravenous ceftriaxone and oral metronidazole followed by 4 weeks of oral co-amoxiclav. Her headaches and vomiting deteriorated after biopsy with a peak CRP of 218 mg/L, which resolved following medical treatment. Imaging with MRI and baseline pituitary function blood tests has since been repeated following the 6 weeks to assess the management’s effectiveness, which showed normal results. The patient reported the resolution of headaches and able to resume full-time schooling.

Figure 1: MRI at presentation.

Figure 2: MRI 3 months after transphenoidal surgery.

Case 2

29 years old Caucasian fine arts student presented to the emergency department with fever, headaches, profuse sweating, tiredness, and blurring of vision. Her symptoms, particularly headaches, had worsened over the last 12 months. She had noticed polydipsia and polyuria. She also had amenorrhoea for twelve months. She was treated at her local hospital twice in the preceding 3 years with symptoms of headaches, fever, weight loss, and vomiting. She had a lumbar puncture 3 times to rule out a possibility of central nervous system infection. On both occasions, she was discharged home after empirical treatment with antibiotics for suspected meningitis. There was no other past medical history. There was no recent travel history or infectious contacts. She was not on any regular medications.

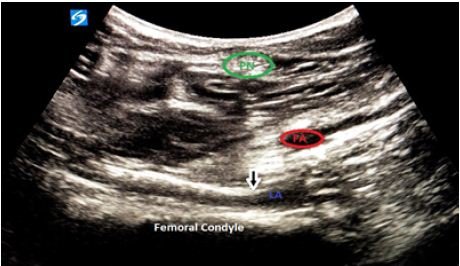

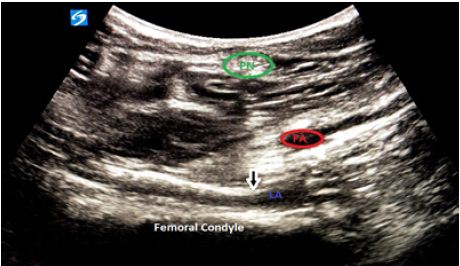

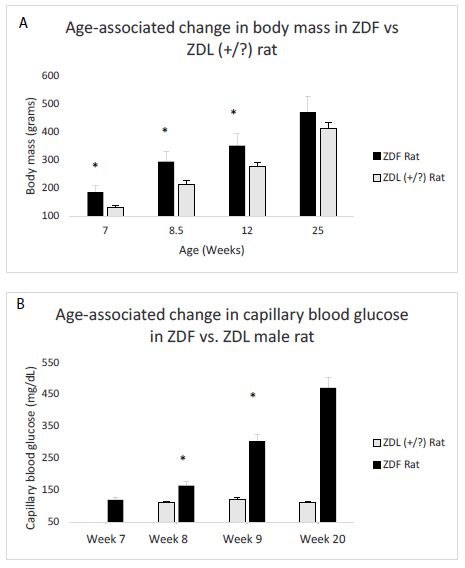

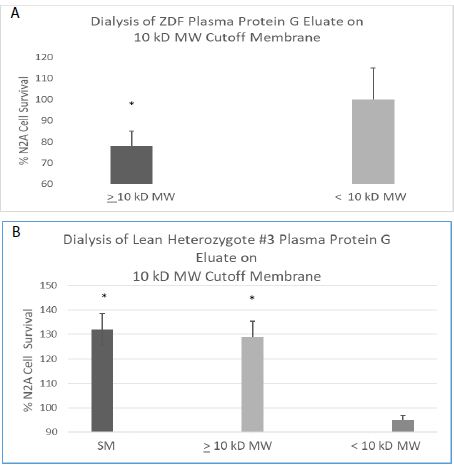

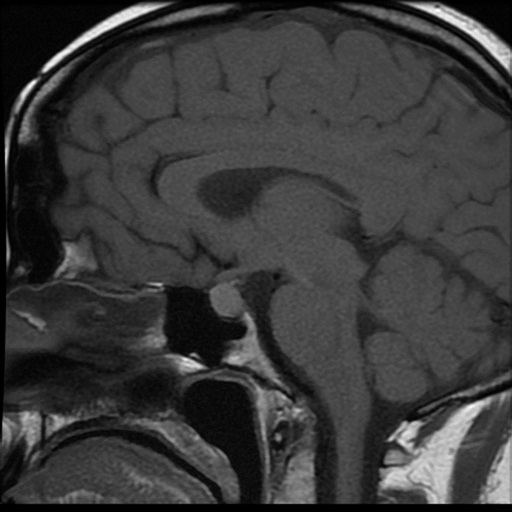

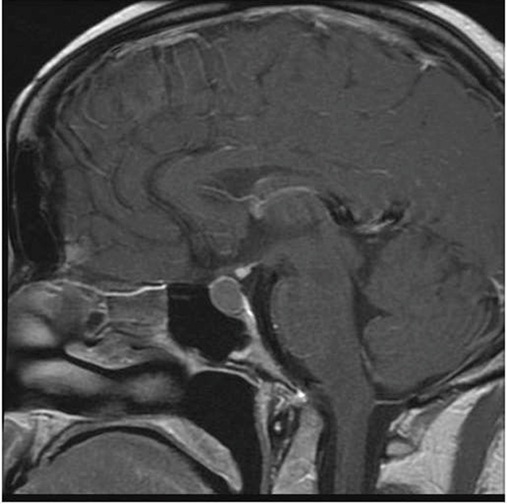

The initial pituitary MRI and contrast-enhanced MRI scan revealed the absence of the posterior pituitary bright spot and a thickened pituitary stalk with a deviation of infundibulum to the right. There was a homogenous hyperintense area within the pituitary gland with no discernable pituitary tissue. This area was hypointense on T2 (Figures 3-5). The differential diagnosis was apoplexy, hypophysitis or a proteinaceous cystic lesion replacing or compressing the pituitary gland. The optic nerves and the chiasm appeared normal. Her investigations confirmed her to have hypopituitarism with Diabetes insipidus (Table 2). Her lumbar puncture showed no CSF abnormality. Her tumor markers and Quantiferon for tuberculosis were negative. The case was discussed in multidisciplinary meeting (MDT) and with empirical diagnosis of hypophysitis, she was started on prednisolone with the replacement of deficient hormones, including Desmopressin. She showed no improvement in her clinical symptoms. A 3 month interval scan showed an increase in the size of the pituitary gland with further thickening of the stalk and optic chiasm displaced superiorly. After the second discussion in MDT, she had a pituitary biopsy. During surgery, soft yellow-white pus-like material was drained after dural incision. The microscopy showed necrotic material with a little amount of compressed anterior pituitary gland, chronic inflammation, and no evidence of adenoma or granuloma or giant cells was found. No acid-fast bacilli or organisms were seen on gram staining, and the culture for TB was negative. There was scanty growth of Propionibacterium acneformis. Her interval scan 3 months later showed complete resolution of the non-enhancing T1 hypertense pituitary tissue with a further decrease in the size of the pituitary gland. She remains on full hormones replacement. She had an insulin tolerance test that confirmed her growth hormone deficiency, and she is now on growth hormone replacement. She remains on hydrocortisone, Thyroxine, female hormone replacement, and Desmopressin.

Figure 3: MRI at presentation.

Figure 4: MRI 3 months later.

Figure 5: MRI post-surgery.

Table 2: Results at initial presentation.

Short Synacthen test

| Time | T=0 | T-30 |

| Cortisol (nmol/L) | 148 | 169 |

Baseline tests

| Test | Result | Normal range |

| IGF-1(nmol/L) | 12.7 | 11.9-40.7 |

| TSH (mU/L) | 1.35 | 0.27-4.20 |

| T4 (pmol/L) | 5.3 | 10.8-25.5 |

| LH (IU/L) | 3.1 | Follicular phase 2-13

Mid cycle 14-96 Luteal phase 1-11 |

| FSH (IU/L) | 5.1 | Follicular phase 4-13

Mid cycle 5-22 Luteal phase 2-8 Postmenopause>25 |

| Oestradiol (pmol/L) | <92 | 92-1462 |

| Prolactin (mU/L) | 577 | 102-496 |

| Serum Na mmol/L | 142 | 133-146 |

| Serum Osmolality mOsmo/Kg | 301 | 275-295 |

| Random Urine Osmolality mOsmo/Kg | 154 | 100-1400 |

| CSF-b HCG (IU/L) | <2 | <2 |

| CSF-alpha fetoprotein (µg/L) | <1 | <1 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 1.4 | 0-5 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 3 | 1-12 |

| Antinuclear antibodies | Negative | |

| IgG4 (g/L) | <0.01 | 0-1.3 |

Discussion

A pituitary abscess is an infectious process characterized by the accumulation of purulent material in the sella turcica. It is rare, and can be a life-threatening condition unless promptly diagnosed and treated. We report 2 cases of secondary pituitary abscess in young women. The first case was due to abscess in the Rahtke’s cleft cyst (RCC), and the second was Pituitary gland abscess with a history of otitis media and repeated lumbar punctures for presumed meningitis.

The clinical presentation of PA is nonspecific, such as headaches, pituitary hypofunction, and visual disturbances, whereas the infection can be discreet and inconstant [5,6]. Symptoms can be acute, subacute, or chronic, explaining the late diagnosis; in some cases. Visual disturbance, including hemianopia, can be present in 50% of cases. Headache without a particular pattern is a regular feature (70-90%) and can be debilitating. Anterior pituitary hypofunction due to destruction and necrosis of the gland is the commonest presentation resulting in fatigue and amenorrhoea (54-85%). In one series, 28 out of the 33 patients had anterior pituitary hypofunction. Pituitary hormone deficiencies persist in the majority of patients following treatment Up to 70% of patients with PA can have central Diabetes insipidus. In contrast, fever with signs of meningeal irritation is reported in 25% of cases [5].

MRI is the imaging of choice for the pituitary lesions. PA can present as a suprasellar mass (65%) or as an intrasellar mass (35%). A typical PA appears as a single cystic or partially cystic mass that is hypointense on T1-weighted image and hyperintense in T2-weighted image. It can show a rim of enhancement after contrast gadolinium. The posterior pituitary bright spot is mostly absent in majority of the cases (Wang et al.). The lesion’s signal depends on protein, water, lipid content, and whether there is hemorrhage. Imaging can also show the invasion of an adjacent anatomical structure, peripheral meningeal enhancement, thickening of the pituitary stalk, and paranasal sinus enhancement [6].

Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DWI) is widely used to differentiate cerebral abscess from other necrotic masses. Brain abscesses typically show high intensity on DWI with decreased apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) value in their central region. The high intensity on DWI is useful but not specific to PA because pituitary apoplexy can also exhibit high intensity on DWI [7]. The accuracy of DWI in PA remains controversial. In the Wang et al. case series, PA was misdiagnosed in one-third of the case [6]. The radiological differential diagnosis includes, Rathke’s cleft cyst, cystic pituitary adenoma, arachnoid, and dermoid cysts, metastases, glioblastoma multiforme, chronic hematoma, and multiple sclerosis [8]. Rathke’s cleft cyst mainly can mimic a pituitary abscess [9]. RCC is the second most common incidentaloma after adenomas and accounts for 20% of incidental pituitary lesions at autopsy. The incidence of RCCs in children was reported to be much lower than in adults. However, the prevalence is now believed to be much higher, especially among those with the endocrine-related disorder [10]. Gunes et al. reported the radiological appearance of RCC on MRI in 13.5% of the children who underwent MRI for the investigation of endocrine-related disorders. Patients with RCC are usually asymptomatic, but symptomatic RCC is more common in females in both adult and pediatric populations [11]. RCC can cause significant morbidity such as headache, visual disturbances, chemical meningitis, endocrine dysfunction (hypothyroidism, menstrual abnormalities, diabetes insipidus, adrenal dysfunction, and very rarely apoplexy). Short stature, growth deceleration, delayed puberty are also reported in children and adolescents.

The diagnosis of PA in most cases can only be confirmed after surgical exploration, due to overlapping of clinical signs, symptoms, imaging, and laboratory findings with other sellar lesions. Signs of inflammation are present in less than a third of the patients. The PA should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients with headaches or signs of pituitary dysfunction and patients with pituitary mass who develop signs of meningeal inflammation.

The main treatment for PA in patients with mass effect is Transsphenoidal excision (TSS) with decompression of sella and antibiotic therapy. This can result in the resolution of visual abnormalities. Treatment is effective for typical symptoms such as fever, headache, and visual changes. Patients with shorter duration of symptoms and those with primary abscess have better improvement in their pituitary dysfunction. Majority of the patients remain with pituitary dysfunction even after the treatment.

Antibiotic therapy should to started promptly even in the patients who are waiting for microbiology and histological confirmation for about 4–6 weeks [1,12]. Empirical treatment with ceftriaxone is indicated until the results are available. Hormone replacement is commenced depending on the hormone deficits including stress dose glucocorticoid therapy. Hypocortisolemia should be recognized among patients presenting with sellar masses, as early diagnosis and treatment improve survival and endocrinological outcome. Patients who suffer from the pituitary abscess may eventually have a good quality of life if they are diagnosed and treated early. A craniotomy is reserved for larger lesions with the suprasellar extension or where transsphenoidal surgery is ineffective [13]. In a series published with 66 patients, 81.8% of patients recovered completely, 12.1% of patients had at least one operation for recurrence, and only one patient had died [14].

There are widespread pathogenic microorganisms in abscesses. These include Gram-positive bacteria, Gram-negative bacteria, anaerobes, and fungi [8,11]. Streptococcus and Staphylococcus are the most predominant Grampositive bacteria, whereas Escherichia coli, Mycobacterium, and Neisseria have also been reported [3,10,11]. Aspergillus fumigatus is mostly isolated in cases of secondary PA. Immunosuppressed patients mostly have Candida and Histoplasma. Cultures are positive only in 50% of cases; therefore, broad-spectrum antibiotics are given as empirical treatment. The pathogen identification is important for the therapeutic management [15].

Both patients had culture-positive for Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes). This organism is seated deeply in the pilosebaceous glands, mainly in the scalp and face. It is a slow-growing, pleomorphic, non-spore-forming gram-positive anaerobic bacillus that is a universal component of the normal skin microbiota. It is usually considered a contaminant of blood cultures but occasionally can cause serious infections, including postoperative central nervous system (CNS) infections. P. acnes are the most commonly isolated organism after Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis following craniotomies. In the presence of heavy infiltrates, the Gram stain is not reliable. Gram stain is only positive in about 10.5% of clinically significant infections with moderate growth. P. acnes behave in a less aggressive manner than other postsurgical organisms and only accounts for a small fraction of CNS infections [16]. P. acnes abscesses typically follow craniotomy, shunts, access to reservoirs, trauma, and foreign bodies. Granulomatous responses have been documented in the CNS following P. acnes infections.

P. acnes grow slowly in the laboratory. This can cause in a delay in diagnosis, missed diagnosis, or delay in treatment if specimens are not cultured for an extended period. Cultures may not grow for as long as 14 days, so samples should be held beyond the usual 5 to 7 days. Gram stain may not be a reliable technique for the rapid diagnosis of P. acnes infections. When there is evidence of an abundant inflammatory response in the Gram-stained smear, a more careful evaluation of cultures must be performed. Polymerase chain reaction for the 16S rRNA or mass spectrometry can be a useful tool for rapid identification and typing of P. acnes following recovery in culture. Propionibacterium is susceptible to antibiotics used for the treatment of anaerobic infections, including penicillin, erythromycin, lincomycin, and clindamycin, but not metronidazole, which is notably ineffective against P. acnes [17].

Patients with PA should be followed up with serial MRI of the pituitary, hormonal profile and visual fields at 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery. The recurrence rate is variable and depends on the nature of the abscess (primary or secondary. The majority of relapses are associated with either an immunological defect or previous pituitary surgery [12,18].

Conclusion

We presented 2 cases of unusual sellar mass from an abscess in an adolescent and a young adult due to P. acnes, both responded well to treatment.

The pituitary abscess should be included as the differential diagnosis of patients with a sellar or a suprasellar mass, headaches, pituitary dysfunction, and meningeal inflammation.

The diagnosis is difficult before surgery because of overlapping clinical signs, radiological and laboratory findings with other sellar lesions.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be started empirically even before the culture results are available.

Culture is positive only in 50% of cases, and in case of unusual bacteria like P. acnes, an extended culture is required for the confirmation of the diagnosis.

Pituitary dysfunction should be recognized and appropriately treated particularly glucocorticoid replacement.

Transsphenoidal surgery is the treatment of choice and this is followed by pronged 4-6 weeks of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy.

Early and efficient surgical and medical management results in lower mortality and higher recovery of pituitary hormone function.

Patients should be followed up with MRI imaging, assessment of the hormone replacement if required, and visual field assessment because of a chance of recurrence.

References

- Lin Y, Lin F, Liang Q, Li Y, Wnag Z, et al. (2017) Pituitary abscess: report of two cases and review of the literature. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 13: 1521-1526. [crossref]

- Furnica RM, Lelotte J, Duprez T, Maiter D, Alexopoulou O, et al. (2018) Recurrent pituitary abscess: case report and review of the literature. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep 17-0162. [crossref]

- Kummaraganti S, Bachuwar R, Hundia V, et al. (2013) Pituitary abscess: A rare cause of pituitary mass lesion. Endocrine Abstracts 31: 1. [crossref]

- Al Salamn JM, Al Agha RAMB, Helmy M, et al. (2017) Pituitary abscess. BMJ Case Rep 2016-217912. [crossref]

- Nordjoe YE, Igombe SRA, Laamrani FZ, Jroundi L, et al. (2019) Pituitary abscess: two case reports. J Med Case Rep 13: 342.

- Wang Z, Gao L, Zhou X, Guo X, Wang Q, Lian W, Wang R, Xing B, et al. (2018) Magnetic resonance imaging characteristics of pituitary abscess: a review of 51 cases. World Neurosurg 114: e900-e902. [crossref]

- Xu XX, Li B, Yang HF, Du Y, Li Y, Wang WX, et al. (2014) Can diffusion-weighted imaging be used to differentiate brain abscess from other ring-enhancing brain lesions? A meta-analysis. Clin Radiol 69: 909-915. [crossref]

- Corsello SM, Paragliola1 RM, et al. (2017) Differential diagnosis of pituitary masses at magnetic resonance Imaging. Endocrine 58: 1-2.

- Coulter IC, Mahmood S, Scoones D, Bradey N, Kane PJ, et al. (2014) Abscess formation within a Rathke’s cleft cyst. J Surg Case Rep 11: 105. [crossref]

- Vasilev V, Rostomyan1 L, Daly AF, Potorac J, Zacharieva S, et al. (2016) Bonneville JF and Becker A. Pituitary ‘incidentaloma’: neuroradiological assessment and differential diagnosis. European Journal of Endocrinology 175: R171-R18. [crossref]

- Güneş A, Güneş SO (2020) The neuroimaging features of Rathke’s cleft cysts in children with endocrine-related diseases. Diagn Interv Radiol 1: 61-67. [crossref]

- Vates GE, Berger MS, Wilson CB, et al. (2001) Diagnosis and management of pituitary abscess: a review of twenty-four cases. J Neurosurg 95: 233-241. [crossref]

- Karagiannis AKA, Dimitropoulou F, Papatheodorou A, Lyra S, Seretis A, Vryonidou A, et al. (2016) Pituitary abscess: a case report and review of the literature. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep [crossref]

- Ling X, Zhu T, Luo Z, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Zhao P, Si Y (2017) A review of pituitary abscess: our experience with surgical resection and nursing care. Transl Cancer Res 6(4): 852-859.

- Achermann Y, Goldstein EJC, Coenye T, Shirtliff ME, et al. (2014) Propionibacterium acnes: from Commensal to Opportunistic Biofilm-Associated Implant Pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev 27: 419-440. [crossref]

- Chung S, Kim JS, Seo SW, Ra EK S, Joo SI, Kim SY, Park SS, Kim EC, et al. (2011) A Case of Brain Abscess Caused by Propionibacterium acnes 13 Months after Neurosurgery and Confirmed by 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing. Korean J Lab Med 31(2): 122-126. [crossref]

- Yacoub AT, Khwaja S, Daniel L, et al. (2015) Propionibacterium acnes Causing Central Nervous System Infections: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Infectious Diseases in Clinical Practice 23: 60-65. [crossref]

- Batool SM, Mubarak F, Enam SA, et al. (2019) Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging may be useful in differentiating fungal abscess from malignant intracranial lesion: Case report. Surg Neurol Int 10: 13. [crossref]