Abstract

The study, Telemedicine: Enabling Patients with Arrhythmias in Self-Care Behaviors study is designed for early recognition and treatment of an arrhythmia and optimizing patients’ medication, activity, and arrhythmia self-efficacy. Telemedicine is a method which allows health care professionals to evaluate, diagnose, and treat patients within their homes and remote locations [1]. Connecting with patients via video and telephone visits allows the caregiver access and assists the patient in improving self-care behaviors and self-efficacy in managing arrhythmias [1,2]. This pilot telemedicine study provides earlier diagnosis of abnormal arrhythmias and increased patient involvement and self-efficacy of one’s health care solutions [2]. The Telemedicine: Enabling patients in Self-Care Behaviors study started in February 2020, prior to the onset of the Covid 19 pandemic. The study has been placed on hold since March 17, 2020. In a response to the Covid-19 pandemic (separate from this study) multiple medical and nursing practices have adopted telemedicine to maintain ongoing care appointments [3]. The study displays the complementing use of three survey tools (Medication Understanding and Self-Efficacy Tool, Functioning Self Efficacy Scale, and Arrhythmia Specific questionnaire in Tachycardia an Arrhythmia) with monitoring devices (loop recorders, Kardia-TM, pacemakers and cardioverter defibrillators-ICDs) coupled with telephone and video visits to pinpoint arrhythmia changes and exact patient reactions and discussion to reinforce self-efficacy behaviors.

Keywords

Telemedicine, arrhythmia, self-efficacy, behavior.

Introduction

The purpose of the study, Telemedicine: Enabling Patients with Arrhythmias in Self-Care Behaviors (T:EPASB) is to provide an alternative to in person visits, decreased the time of diagnosis and treatment of an arrhythmia via the internet, and enable patients to improve self-efficacy of arrhythmia care behaviors. Self-efficacy can be defined as the individual’s belief in oneself to handle a set of circumstances or changes in physical or mental well-being [2].

The first outcome of the study is to determine if subjects in a telemedicine program for the care of cardiac arrhythmias have any difference in [1] time of arrhythmia recognition [2], time of arrhythmia diagnosis by a healthcare provider, and [3] time of treatment initiation compared with patients enrolled in standard care for cardiac arrhythmias. The second outcome of the study examines subjects’ self-efficacy of medication use, functional self-efficacy, and arrhythmia self-efficacy. A data collection tool was utilized with a simplistic check off system used to mark when one recognized changes in symptoms such as increased palpitations, fatigue, activity intolerance, shortness of breath, and any other change in symptoms associated with an arrhythmia. The tool allowed for quick responses to these symptoms with self-initiated blood pressure check, heart rate check, increased fluids, or taking an additional beta blocker, sitting down and resting, and calling the electrophysiology (EP) office for advice (Appendix A).

Background Information

University based tertiary care clinics, which treat irregular heart rhythms, are known as arrhythmia clinics and formally called electrophysiology departments [4]. These departments have been in existence prior to the early 1960’s and their technology has continued to evolve over time. The need to meet with patients and discuss their abnormal and irregular heart rhythms has entailed prescribing medications to slow the heart rate, prescribing medications to eliminate abnormal heart rhythms, and implanting devices to further control the heart rhythms, known as pacemakers (PPM) and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) [4]. The continued improvement in technology and expansion of such departments has led to a need for increased numbers of patient appointments, dual appointments for arrhythmia management and pacemaker or ICD management, and coordinated appointments with other cardiology sub-specialties [5]. This increased frequency and duration of appointments places stress upon patients with longer drives, wait times, financial stressors of parking, food, and gas costs in reaching such appointments [6]. With such stressors, a need for computer assisted video visits has evolved [6]. The monitoring of arrhythmias involves home monitoring via external disposable monitors which are affixed on the chest wall, small implanted monitors (loop recorders), and utilizing the monitoring features of permanent pacemakers (PPMs) or implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs).

Review of literature

The T:EPASB is based upon studies showing improved clinical outcomes with the use of telemedicine. The TRUST trial compares the use of a telephone video conference to conventional in person visits with individuals with ICDs. The TRUST trial determined the efficacy and safety for monitoring ICDs and the reduction of in person visits [7,8]. This study displayed an adverse event rates of 10.4 for each group [7,10] and no difference in the telemedicine versus the in person visit group.

The Poniente trial determined there was no difference in arrhythmia detection and functional capacity in monitoring elderly patients with pacemakers via home monitoring compared with in person monitoring [9]. The CHOICE AF was a pilot study to test the feasibility of brief telephone-based program to target improving cardiovascular risk factors and health related quality of life in patients with atrial fibrillation [11], showing great potential for a telephone- based program.

A study by Ryan et. al. (2018) [13] verified the efficacy of theory based Integrated Theory of Health Behavior Change (ITHBC) intervention utilizing a cellular phone application to increase women’s initiation and long-term maintenance of osteoporosis self-management behaviors. This study takes a chronic disease state, osteoporosis, and combines ITHBC prompted behaviors with a cellular phone application to assist women in behavior change. Suter et. al. (2011) [14] used self-efficacy as a key component in managing one’s health noting patient empowerment in the management of chronic disease conditions such as diabetes mellitus and heart failure. The study identified the essence of telemedicine in its ability to empower patients with skills in managing one’s chronic health condition.

Theoretical Framework

Integrated Theory of Health Behavior Change (ITHBC) was used in guiding this study as it notes the importance in assisting individuals in becoming increasingly involved in their own health care [2]. This theory links a relationship between the way one views one’s own health care and an overall sense of wellness. Dr. Ryan’s study of those with chronic health care diagnosis’ and improving specific health care behaviors highlighted the need to 1) have a change in how one reacts followed by 2) one’s resultant behavior with an improved sense of wellness (when assisted with behavior changes). Essential components for behavior change include a desire to change, self- reflection, positive social-influence and support required in creating the change [2].

Methods and Materials

The study is a prospective randomized controlled study, in which informed consent was obtained. Randomization included subjects picking from sealed envelopes which were numbered, labelled with a folded card within each envelop stating either standard versus telemedicine visits. The University of Michigan Hospital IRB number: IRB00001995.

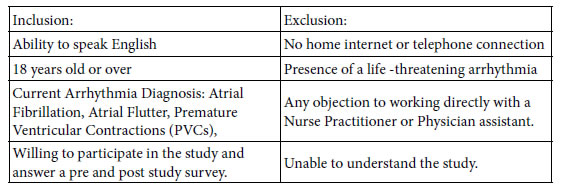

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria:

Methods

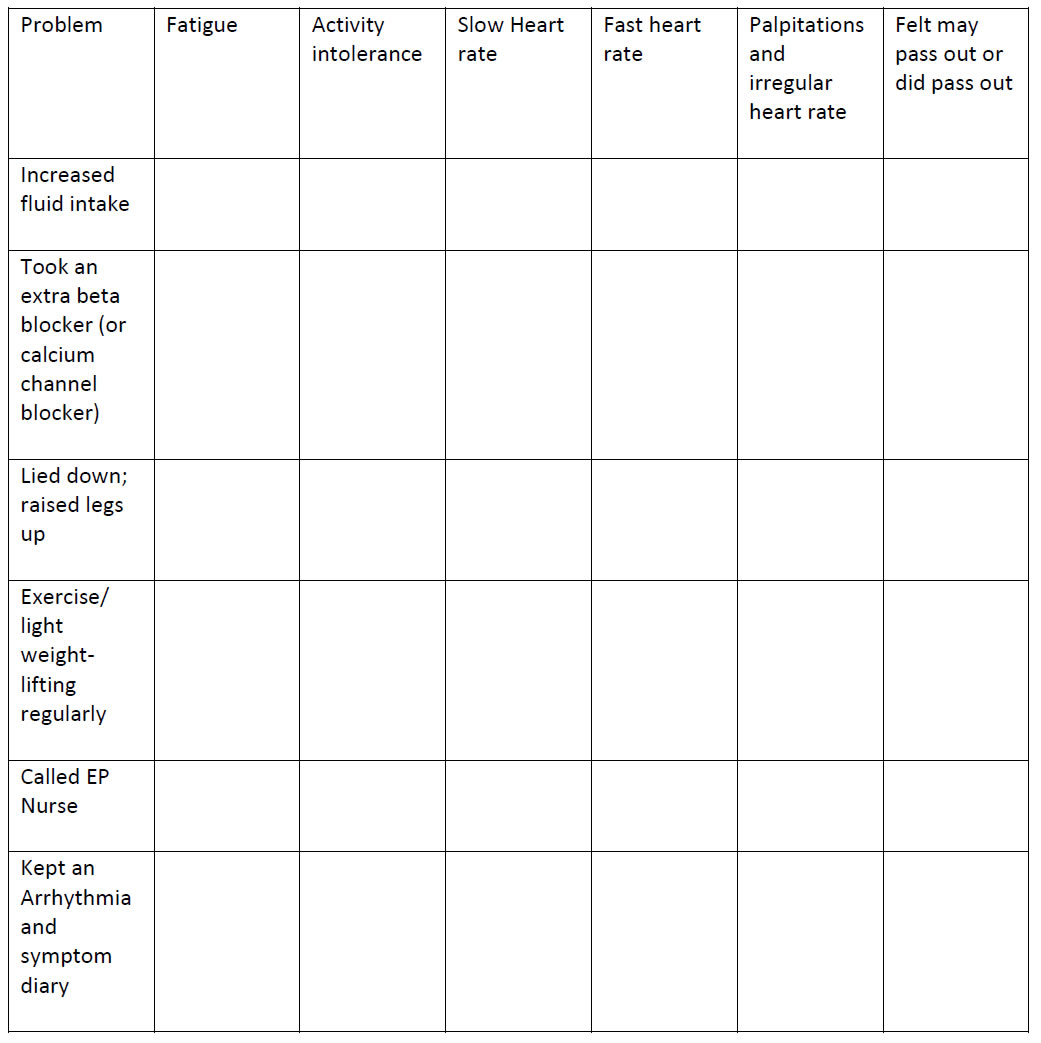

The study was introduced to the subjects during an initial meeting with an explanation of the study and an explanation of the consent. After the informed consent was obtained, the subjects were randomized into telemedicine or standard in person six- month visits.

With the initial visit, surveys were completed with telemedicine and standard visit groups. Telemedicine subjects received monthly visits for three consecutive months and standard received a six month return visits (Appendix B-study schematic). Interventions provided to the telemedicine group included discussion and reinforcement of medication, functional activity and arrhythmia self-efficacy, guided discussion, and social support.

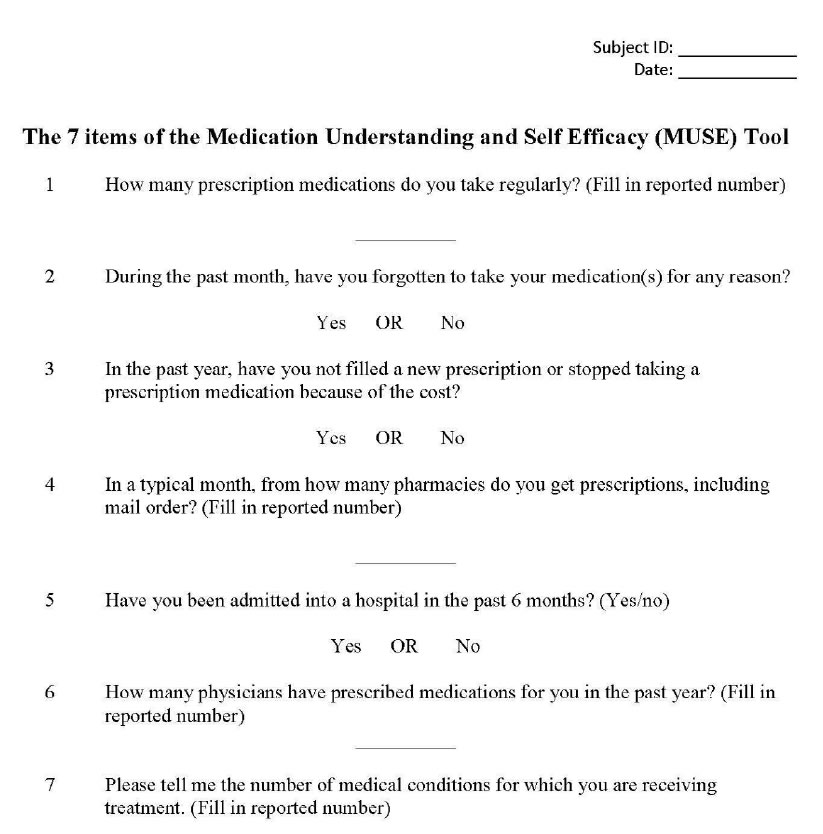

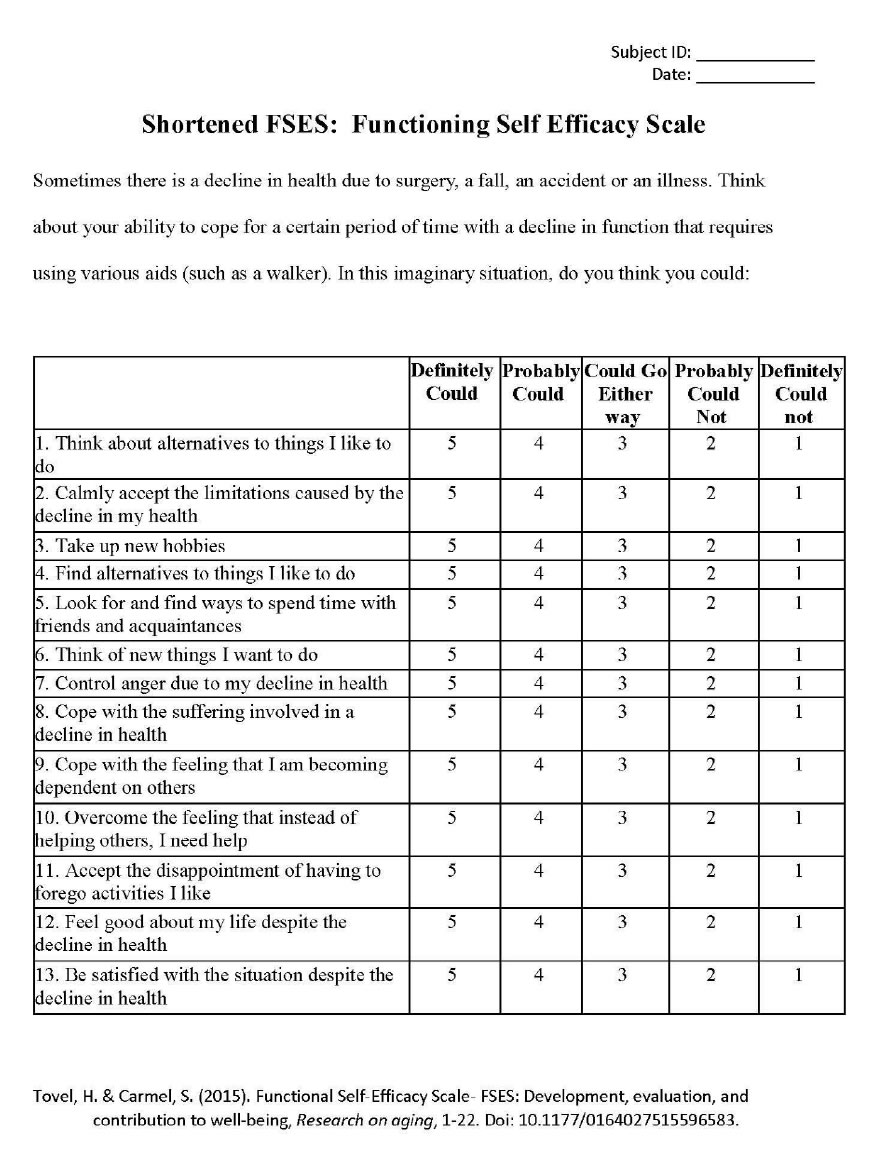

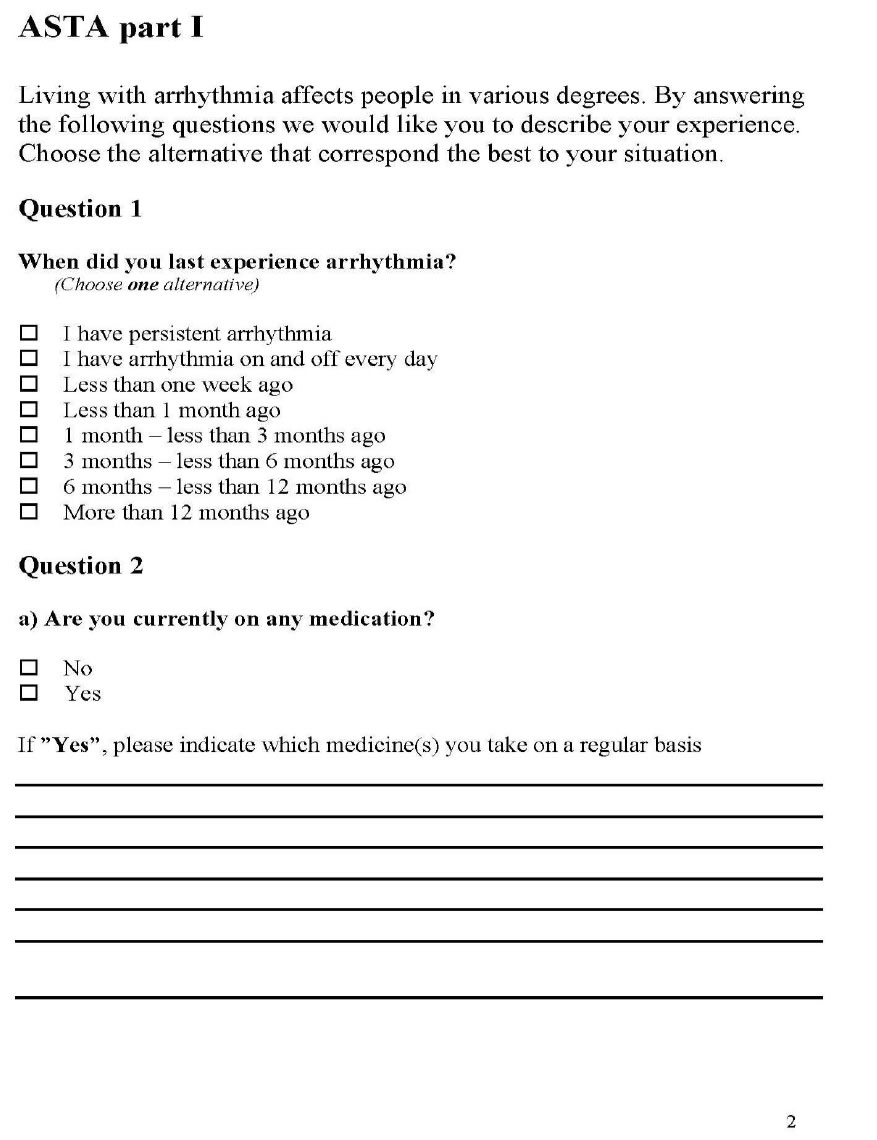

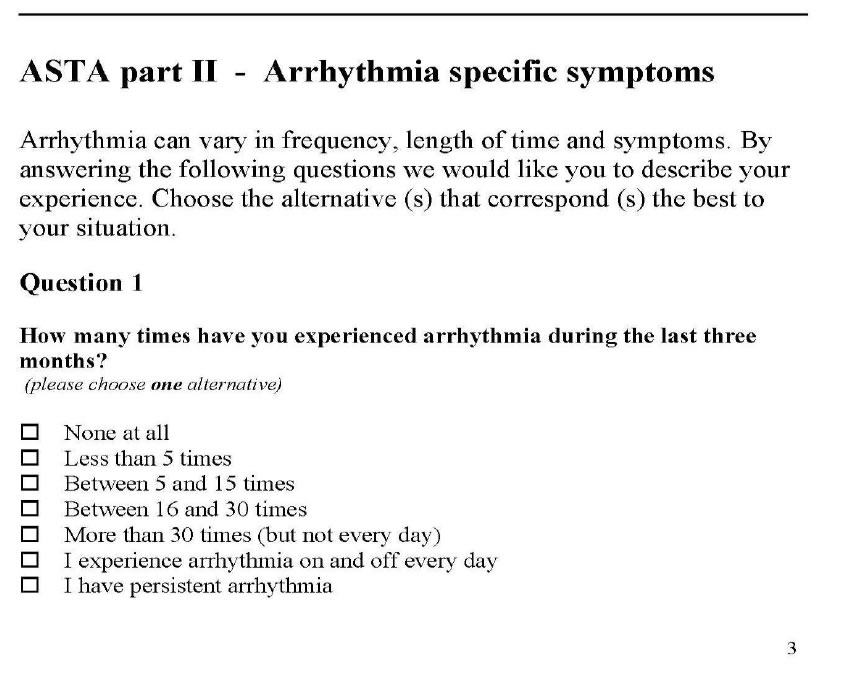

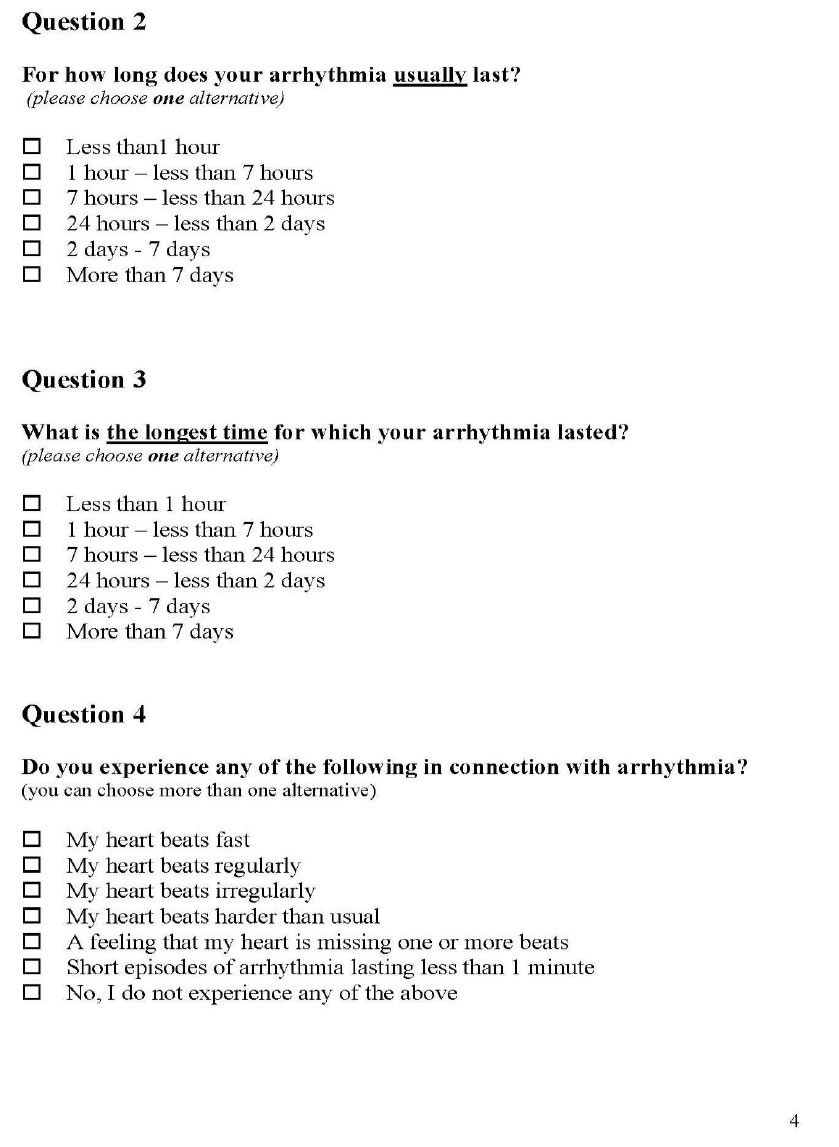

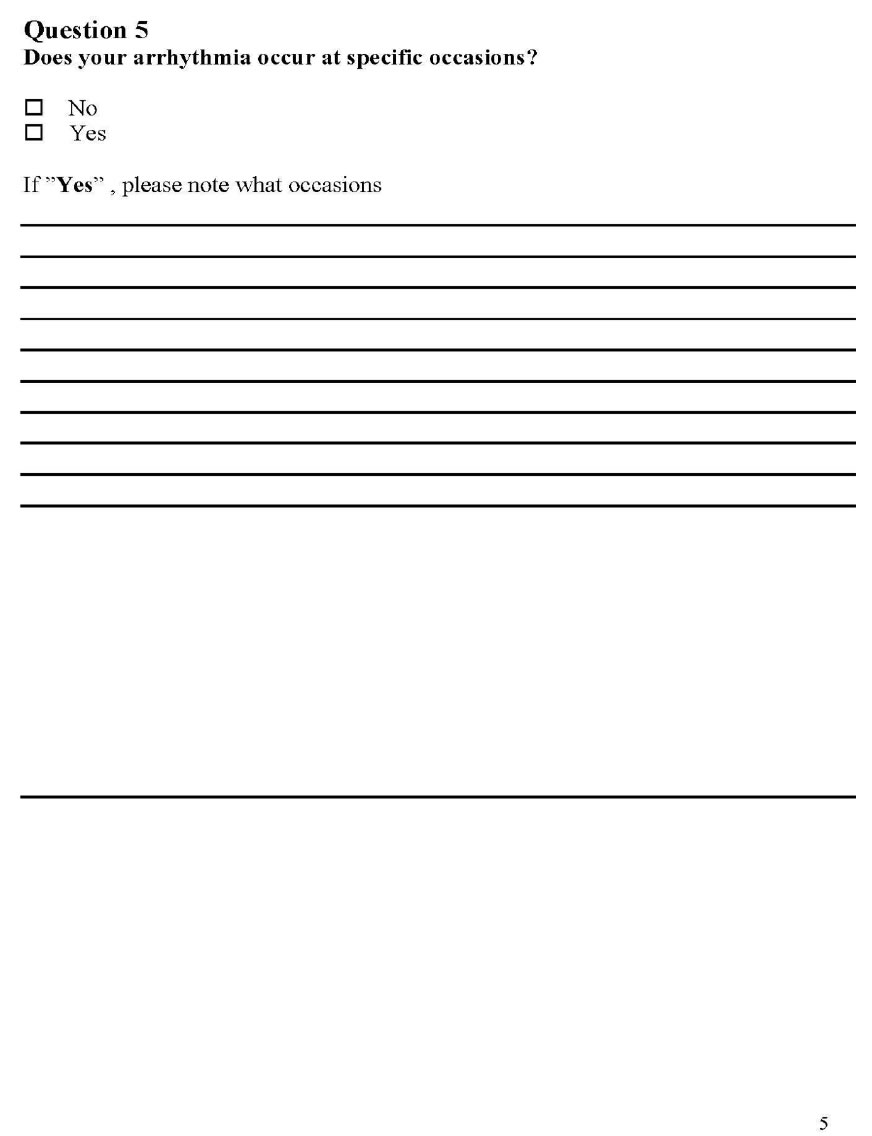

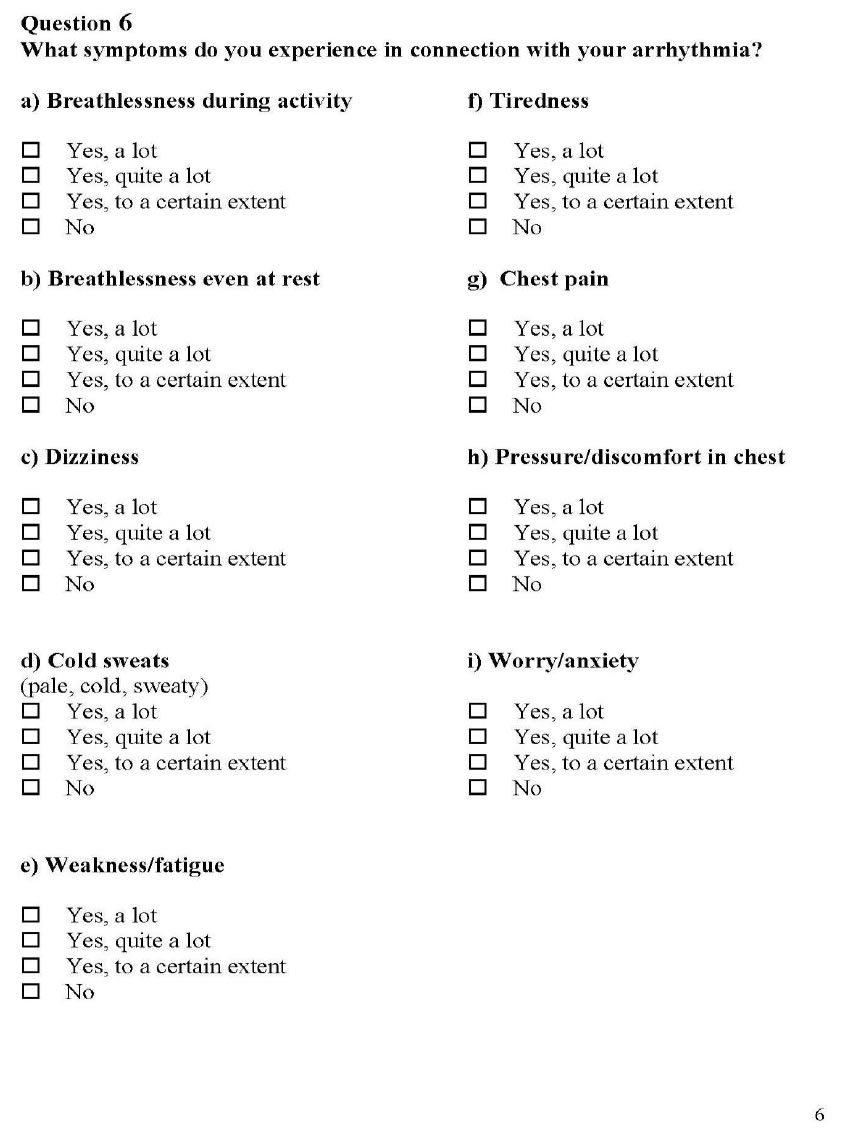

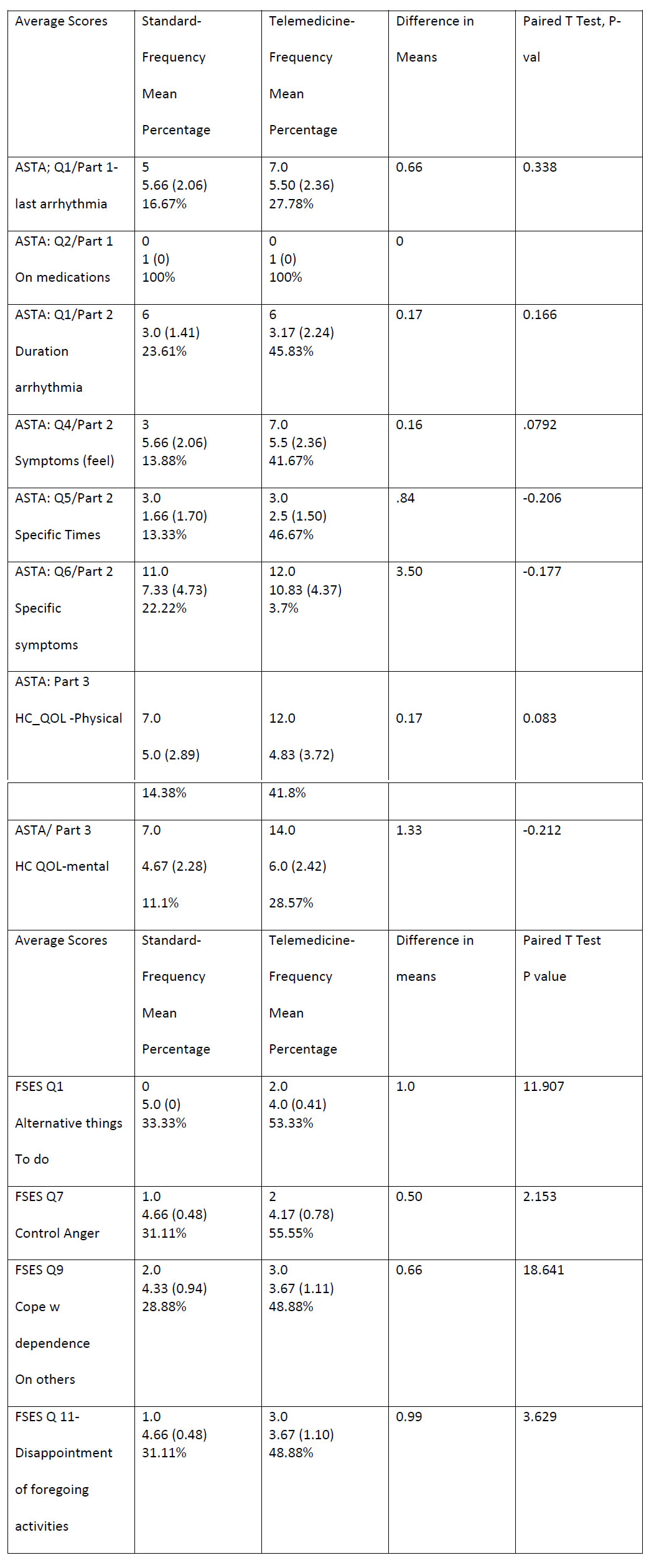

The surveys utilized were the Medication Understanding and Self-Efficacy Tool, Functioning Self Efficacy Scale, and Arrhythmia Specific questionnaire in Tachycardia an Arrhythmia (MUSE, FSES, ASTA) surveys. All three surveys were provided on the first day of the study to each study group subject and on the last day of the study for each study group subject. Key questions were compared with a calculation of the mean for these questions, comparing the standard group with the telemedicine group. (Appendix C, D, E– MUSE, FSES, and ASTA surveys).

There were chart reviews and analysis of monitored data from devices revealing onset of arrhythmias, times of diagnosis’ and treatments in the telemedicine group compared with the standard group. The T:EPASB utilizes the null hypothesis to demonstrate no difference in time of recognition of an arrhythmia, time to diagnosis and treatment of the arrhythmia, between the telemedicine group as compared with the standard group. The null hypothesis is be used in the Medication Understanding and Use Self- Efficacy (MUSE), ASTA (Arrhythmia Specific questionnaire in Tachycardia and Arrhythmia) and FSES (Shortened Functional Self Efficacy Scale) surveys. A paired T test with the difference in the means of answers to survey questions was utilized in calculating a P value for select survey questions (Appendix C).

Measures

Arrhythmias can be multifactorial and can cause no perceived symptoms versus serious symptoms such as palpitations, fast and pounding heart beats, sweating, chest pain and or pressure, anxiety, fear, and depression [15]. One single survey may not capture the data experienced by the subject and not every survey relates to the self- efficacy of these perceived events. The MUSE survey gives information on medication compliance, cost barriers, number of medications, physicians and pharmacies and hospitalizations. The FSES gives a scale of the subject’s self- efficacy to cope with the arrhythmia and day to day functioning. The ASTA survey is the most specific survey to arrhythmias and the symptoms associated with arrhythmias; but does not reflect the medications or functional capabilities.

The MUSE survey was tested for validity and reliability in measuring patients’ self- efficacy in understanding and using prescription medications [12]. FSES displayed good internal consistency and satisfactory criterion and convergent validity in assessing the degree of confidence self-functioning while facing decline in health and function [16]. ASTA, displayed content validity for all items, and internal consistency [17].

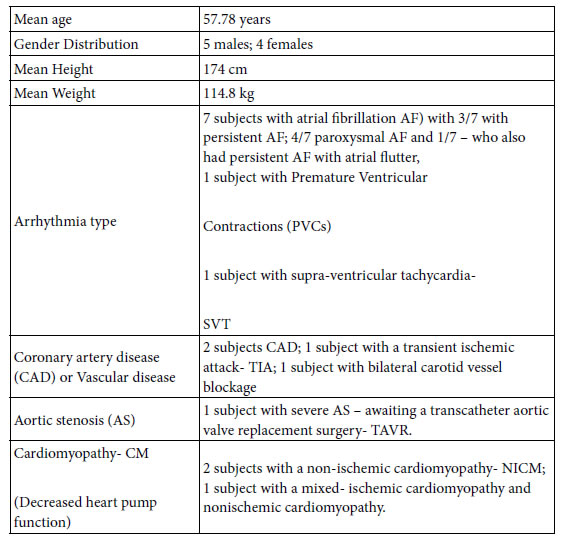

Data Collection Sheet and Demographics:

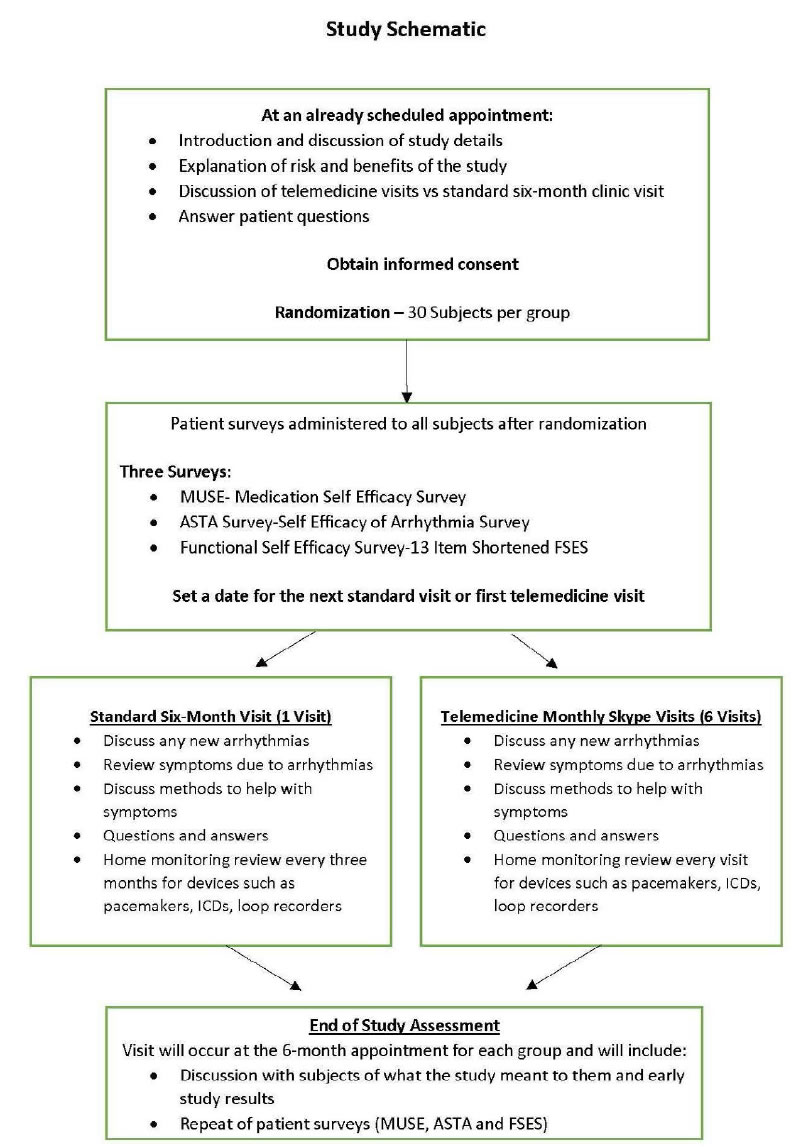

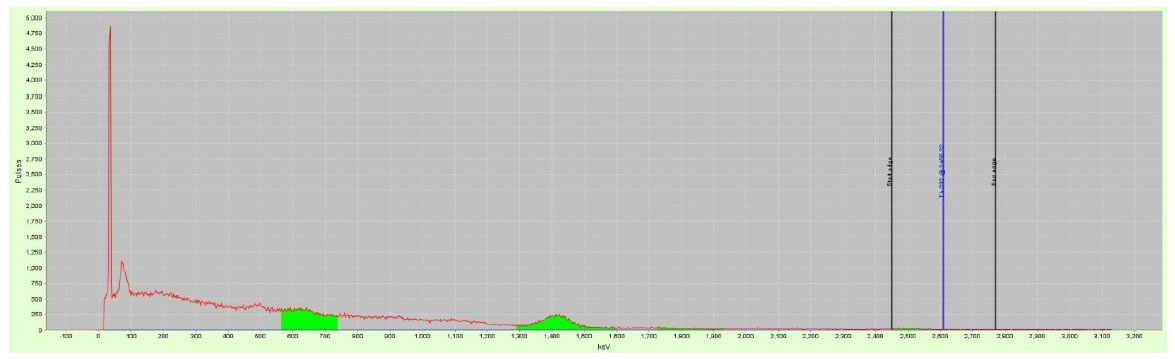

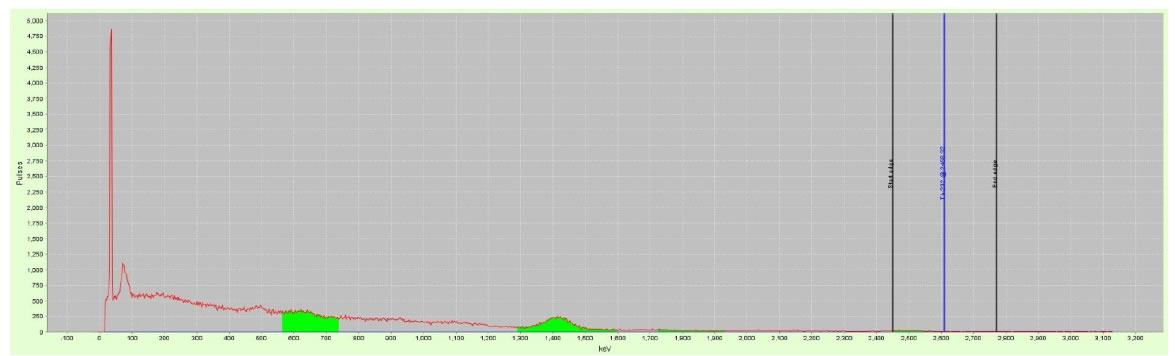

Pilot Study Results

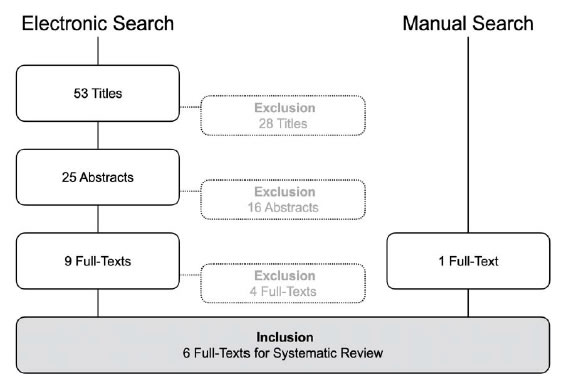

From late February 2020 to March 2020, 9 patients were enrolled in the Telemedicine study and randomized to either standard visits or telemedicine visits. Three patients declined the study, one patient noted he would join the study, but only if he received a Kardia monitoring device (he was not enrolled in the study as this could not be guaranteed and he noted his intention of simply gaining the Kardia device) and was not enrolled due to ethical concerns.

All subjects signed the informed consent and received copies of the protocol and consent, including the clause that they may drop out of the study. Each subject was given instruction on filling out surveys and were given the opportunity to answer questions by the nurse practitioner (NP) in clinic and the research assistant. The surveys were reviewed and scored by the research assistant and double scored with the author of the study. The surveys pinpointed the overall arrhythmia burden, degree to which subjects felt the arrhythmia, and physical and mental coping levels in relation to the arrhythmia. The surveys gave the caregiver (Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants within the EP clinic) specific areas to discuss, reinforce, and empower the subject in arrhythmia behavior change. The time of recognition, diagnosis and treatment of arrhythmias was deferred due to the Covid 19 pandemic and this monitoring data is attained only for daily arrhythmia management.

Appendix D gives the overview of all survey results for T:EPASB. The overview gives the researcher a quick glimpse of any problem areas such with decreased self-efficacy of medication use, or functional capacity or arrhythmia knowledge and understanding.

Results of the MUSE survey show near complete compliance in medication use with only one missed dose of medications from one subject. MUSE tallied results also show no financial constraints to medication obtainment in all nine subjects. There was a 0.8679:1 ratio with number of number of physicians treating to number of medical diagnosis; with a mean of 2.89 physicians prescribing medications to a mean of 3.33 medical diagnosis for the 9 subjects evaluated (Appendix B). When combining the surveys, key data becomes clear. The subjects scoring the lowest functional status self-efficacy, subject 5a and subject 9a with scores of 43 and 44 respectively, scored 37 and 54 respectively on the ASTA arrhythmia burden survey. One can note poor functional self-efficacy, but not necessarily related to arrhythmia burden in subject 5a, while poor functional self-efficacy may be related to a higher arrhythmia burden in subject 9a. Another complementing data point will be specific arrhythmia logs within monitoring- devices; once this deferred data is allowed within the study. Another interesting finding is the subject 8a who has a high arrhythmia burden noted with ASTA of 46, but a very good FSES score of 64.

Discussion

The T:EPASB pilot study has shown the importance of offering an alternative to conventional in person visits, offering counseling in managing one’s self-efficacy for arrhythmia care, and providing reinforcement and social support in managing one’s arrhythmia care. The study illustrates the importance of gathering complementing data on arrhythmia management including medication use and understanding, functional self-efficacy, and arrhythmia self-efficacy. The triad of these surveys provides an excellent overview of one’s arrhythmia self-efficacy. With such data, the medical and nursing provider may offer patient specific counseling. There is an advantage of having a specifically timed event, match a corresponding subject’s complaint. The use of implanted and portable monitoring data gives an excellent overview of the subject’s associated heart rhythm abnormality. The MUSE survey used alone gives a false sense that there may not be any need for any reinforcement of self-efficacy of medication or arrhythmia understanding. When this survey is coupled with the FSES and ASTA, trends begin to develop and specific areas of intervention, such as improved daily activity levels, decreased arrhythmia burdens via medications or activity, utilization of beta or calcium channel blockers, increased fluids, and or activity training to improve arrhythmias may be discussed. The surveys when used together display specific areas to improve subject’s knowledge, one’s confidence and self-efficacy in arrhythmia management. Those with higher arrhythmia burdens in which the subject feels palpitations, fatigue, and side effects have a greater need for intervention which strengthen self-efficacy and social support for medication use, functional activities and arrhythmia management [16,17]. This pilot T:EPASB study continues to show great potential and will likely mimic the TRUST, CHOICE-AF and Poinete trials in identifying, diagnosing, and treating arrhythmias with no difference in timing of these events with telemedicine compared with in person follow up visits with prompt device monitoring. The study has already helped to pinpoint areas of difficulties with arrhythmias, medications, and functional capacity. Via interventions such as affirming knowledge, counselling medication usage, and validating activity and exercise efforts and knowledge, the caregiver may help improve the subjects’ overall functional capacity in coping with one’s arrhythmia. The study’s evaluated questions have not reached significant p values, as the study has been Anecdotally, the overall response to telemedicine has been very positive with comments like, “this is so much better”, “I can concentrate on what you are teaching me, without the long drive” and “this information seems to stick much better, when I learn it at home” and “can we make more telemedicine appointments”. The T:EPASB study can in no way be fully assessed at this early point, but its potential to assist in improving patients’ self-efficacy via increased patient interaction, reinforcement of arrhythmia details, and social support will surely lead to further studies using telemedicine and a triad of survey tools.

Authorship:

Kathleen Fasing, DNP-c, MS,

ACNP Madonna University,

Livonia MI

University of Michigan, Staff ACNP, Ann Arbor, Michigan

DNP Project Chair: Patricia Clark, DNP, RN, ACNP-BC,

ACNS- BC, CCRN, Madonna University,

DNP Project Member: Rachel Mahas, PhD, MS, MPH,

Madonna University, rmahas@madonna.edu

DNP Project Member: Vicki Ashker, DNP, MSA, RN,

CCRN, Madonna University, vashker@madonna.edu

Milwaukee- Self Management Science for your great research on self- efficacy and your ITHBC theory and allowing its use.

Sara Carmel- Ben Gurion University of Negev- Public Health Faculty Member- for your behavior research and functional self- efficacy tool and allowing its use.

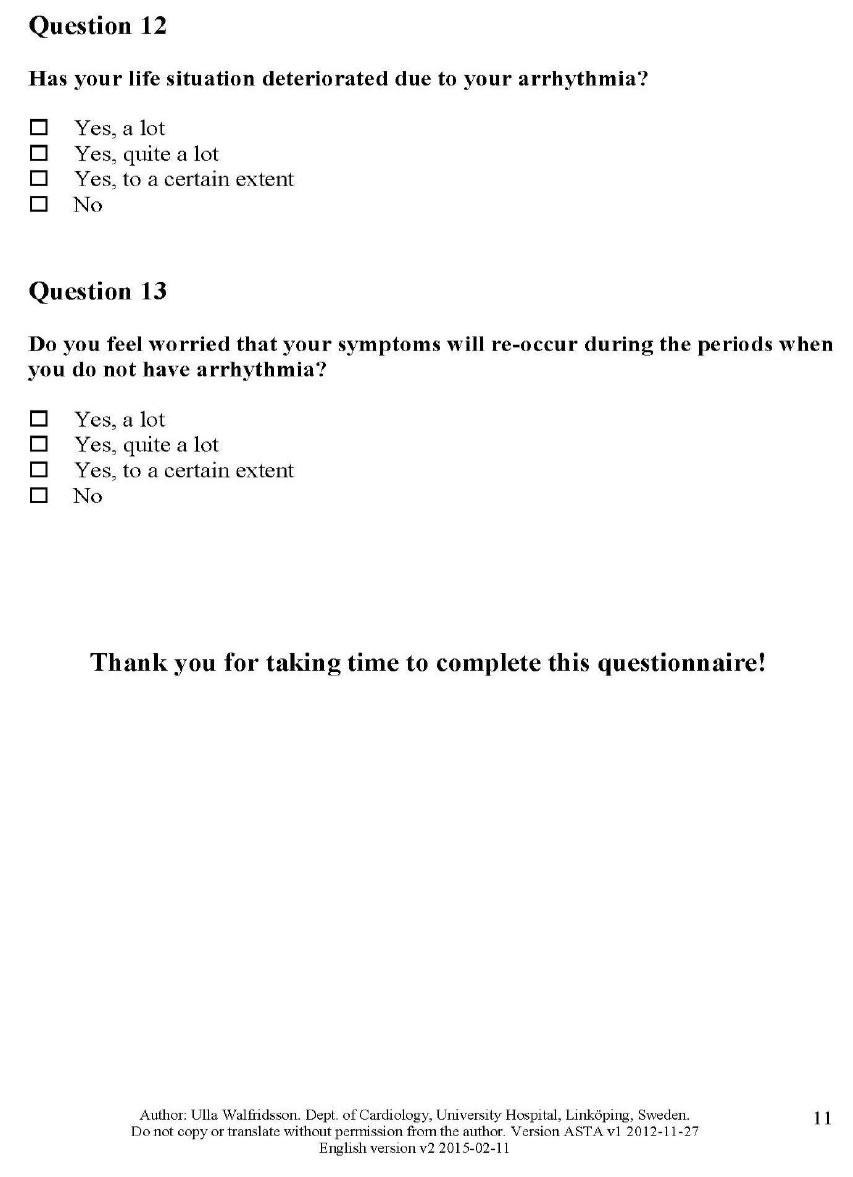

Ulla Walfridsson RN, PhD-Division of Nursing Science; Dept of Medicine & Health Sciences, Linkping, Sweeden- for sharing your incredible arrhythmia assessment tool and allowing its use.

Sangeeta Lathkar-Pradhan- Research Assistant for ongoing support and patience.

Rachel Wessel- Research Assistant for exacting perseverance.

Hakan Oral, MD- University of Michigan EP Director- thanks for believing in me.

Dr. Patricia Clark- DNP committee lead and advisor and patience extraordinaire.

My husband- Gregory Fasing BSN, RCIS- for his forever support.

Acknowledgements

Thank you so much for all who assisted in this project including and in equal acknowledgement.

Polly Ryan PhD, RN, CNS-BC – University of Wisconsin

References

- Kay, Misha, Santos, Takane (2010) Telemedicine opportunities and development in member states, Global observatory for eHealth series, virtualhospital.org.uk. (1,2). [crossref]

- Ryan, P. (2009) Integrated theory of health behavior change: Background and intervention development, Clinical Nurse Specialist, 23 (3): 161-172. (3, 5,18,19). [crossref]

- Lovett-Rockwell, K. & Gilroy, A. (2020) Incorporating telemedicine as part of COVID-19 Outbreak response systems, The American Journal of Managed Care, 26 (4): 147-148. Doi.org/10.37765/ajmc.,(4). [crossref]

- Fozzard (2011) History of basic science in cardiac electrophysiology, Cardiac electrophysiologycinics, 3, 1, 1-10. Doi:10.1016/j.ccep.2010.10.010,(6,7). [crossref]

- Phend, C. (2020) Telehealth shaping up for Covid-19- Cardiology illustrates what specialties can do to be ready, Medpage today.,(8).

- Maffei, R., Hudson, Y. & Skim Dunn, M. (2008) Telemedicine for urban uninsured: A pilot Framework for specialty care planning sustainability, J E health, 14(9), 925- 931 [crossref]

- Dalouk, K., Gandhi, N., Jessel, P., MacMurdy, K. et. al. (2017) Outcomes of telemedicine videoconferencing clinic versus in-person clinic follow-up for implantable cardioverterdefibrillator recipients, Circulation arrhythmia electrophysiology, 10, (11,13).

- Varma, N., Epstein, A., Irimpen, A., Schweikert, R., & Love, C. (2010) Efficacy and safety of automatic remote monitoring for implantable cardioverter-defibrillator follow-up: The Lumos-T safely reduces routine office device follow-up, TRUST trial, Circulation, 122: 325332.,(12). [crossref]

- Lopez-Villegas, A., Catalan-Matamoros, D., Robles-Musso, E., & Peiro, S. (2015) Effectiveness of pacemaker tele-monitoring on quality of life, functional capacity, event detection and workload: The PONIENTE trial, Geriatrics and gerontology international, 16 (11).,(14). [crossref]

- Varma, N. & Ricci, R. (2013) Telemedicine and cardiac implants: what is the benefit? European heart journal, 34 (25), 1885-1895.(15).

- Lowres, N., Redfern, J., & Freedman, S. (2014) Choice of health options in prevention of cardiovascular events for people with atrial fibrillation (CHOICE AF): A pilot study, European journal of cardiovascular nursing, doiorg.proxy.lib.umich. edu/10.1177/14745114549687. (16). [crossref]

- Cameron, K., Ross, E., Clayman, M., Bergeron, A., et. al. (2010) Measuring patients’ self-efficacy in understanding and using prescription medication, PatientEducation Couns, 80 (3); 372376. Doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.06.029.,(17,21). [crossref]

- Ryan, P., Papanek, P., Csuka, M., Brown, M., et. al. (2018) Background and method of the striving to be strong study, a RCT test the efficacy of a mhealth self-management intervention, Contemporary Clinical Trials, 71, 80-87.,(16). [crossref]

- Suter, B., Suter, W. N., & Johnston, D. (2011) Theory-based telehealth and patient empowerment, Population Health Management, 14 (2).,(19). [crossref]

- Withers, K., Wood, K., Carolan-Rees, G, Patrick, H., et.al. (2015) Living on a knife edge- the daily struggle of coping with symptomatic cardiac arrhythmias, Health quality life outcomes, 13:86.,(20). [crossref]

- Tovel, H. & Carmel, S. (2015) Functional Self-Efficacy Scale- FSES: Development, evaluation, and contribution to well-being, Research on aging, 1-22. Doi: 10.1177/0164027515596583. (16,22,24). [crossref]

- Walfridsson, U., Arestedt, K., & Stromberg, A. (2012) Development and validation of a new arrhythmia-specific questionnaire in tachycardia and arrhythmia (ASTA) with focus on symptom burden, Health quality life outcomes, 10-44, doi: 10.1186/1477- 7525-10-44.,(23,25). [crossref]

Appendix A. Data Collection Tool- Aid for patient at home.

2 points each for every activity noted along the vertical axis; showing an activity taken due to the symptom noted on the horizontal axis. Subject to keep weekly log of number of symptoms and number of points for response activities.

Walfridsson, U., Arestedt, K., & Stromberg, A. (2012) Development and validation of a new arrhythmia-specific questionnaire in tachycardia and arrhythmia (ASTA) with focus on symptom burden, Health quality life outcomes, 10-44, doi: 10.1186/1477- 7525-10-44.,(23,25).

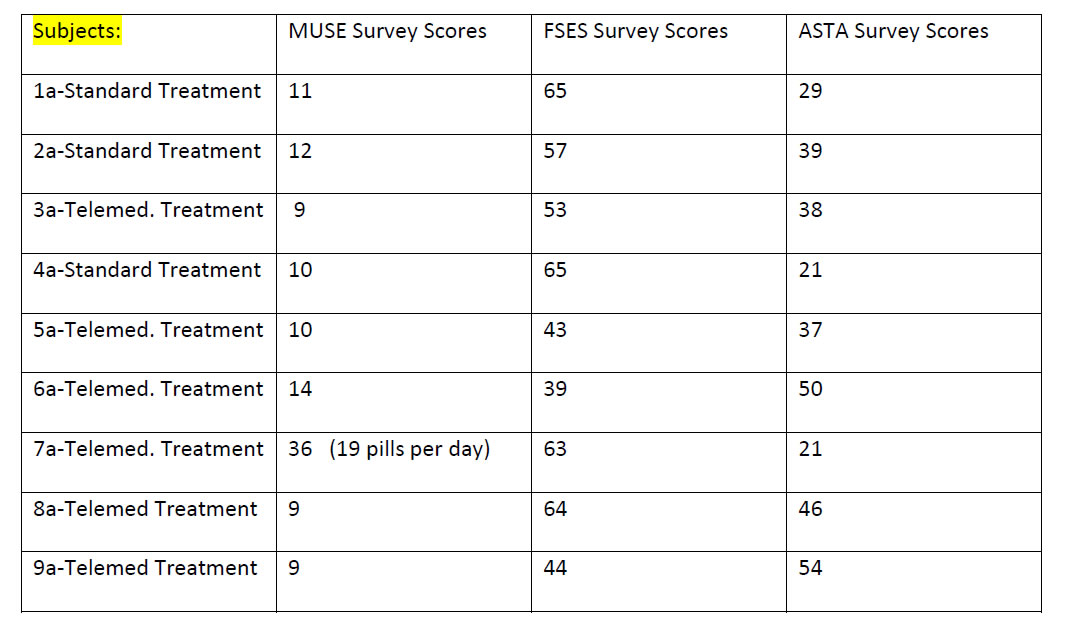

Appendix D: Scores of completed surveys:

Survey Scores: Key- Muse– Shows any difficulty in taking; or understanding medications. FSES–

highest the better functional status; highest possible =65. ASTA– the highest the worse arrhythmia burden, symptoms, and mental and physical QOL.

Appendix D. – Answers to the above scores

Muse Survey Answers

Question 1– How many prescriptions medications do you take regularly?

Mean= 5.33 medications; Median 4 Medications; Mode 5 medications with a low answer of 2 and high answer of 19 medications.

Question 2– During the past have you forgotten to take any medication? “Only 1 yes.

Question 3– In the past did you not fill or stop taking the prescription due to cost? All answered no.

Question 4– In a typical month how many pharmacies do you use; including mail order? Six subjects answered 1/ 3 subjects answered 2.

Question 5– Have you been admitted to the hospital in the past six months? –Three subjects -yes.

Question 6– How many physicians prescribed medications for you in the past year? – mean answer 2.89.

Question 7– How many medical conditions which you are receiving treatment? – mean answer 3.33

FSES Shortened Survey * Higher scores showing better functional status

This survey gained very differing results for patient. Two subjects scored the total possible of 65 points indicating the best functional status and answered 5 (maximal score) for all 13 questions. One subject answered 3 for each of the 13 questions with a score of 39 and indicating day to day function was exactly in the middle of the survey. Other subjects gave a variable scoring with specific areas and gave a scattered response, depending upon the question. Two of the subjects gave responses in the 2 range, or lower level of functional capabilities. Scores listed in 1a-9a order: 65/ 57/ 53/ 65/ 43/ 39/ 63/ 64/ 44.

ASTA Survey The survey is scored into three categories- presence of arrhythmia, symptoms associated with the arrhythmia and Health related Quality of life (QOL)- both mental and physical. Higher the score- the higher the arrhythmia burden, more symptoms and more impact on the health related QOL. Scores listed in 1a- 9a order: 39/39/38/21/37/50/21/46/54.

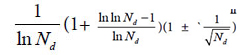

Average Scores Pre and Post (n=9)

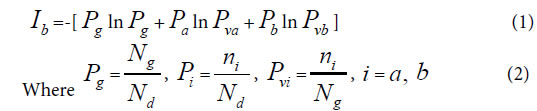

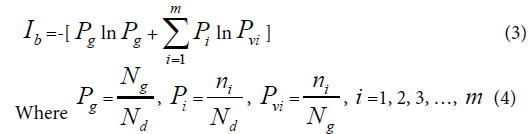

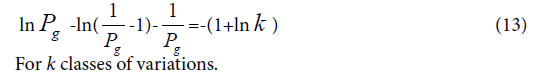

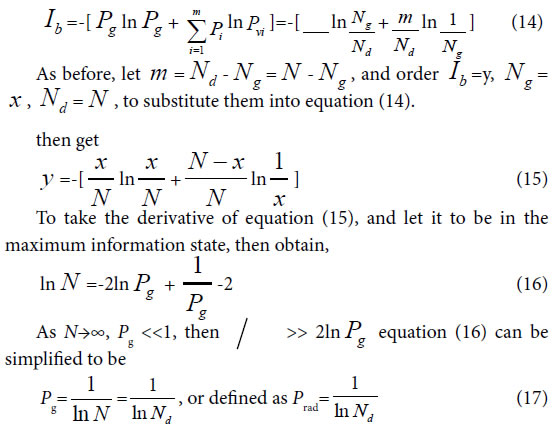

, or is precisely equal to

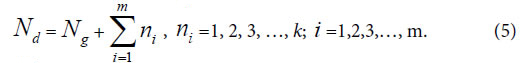

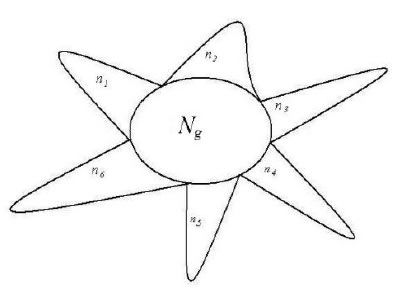

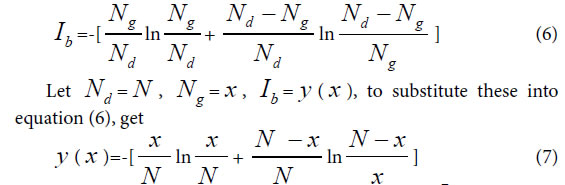

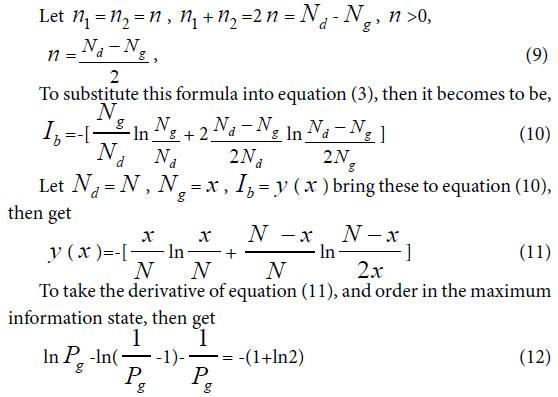

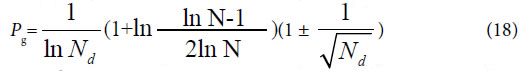

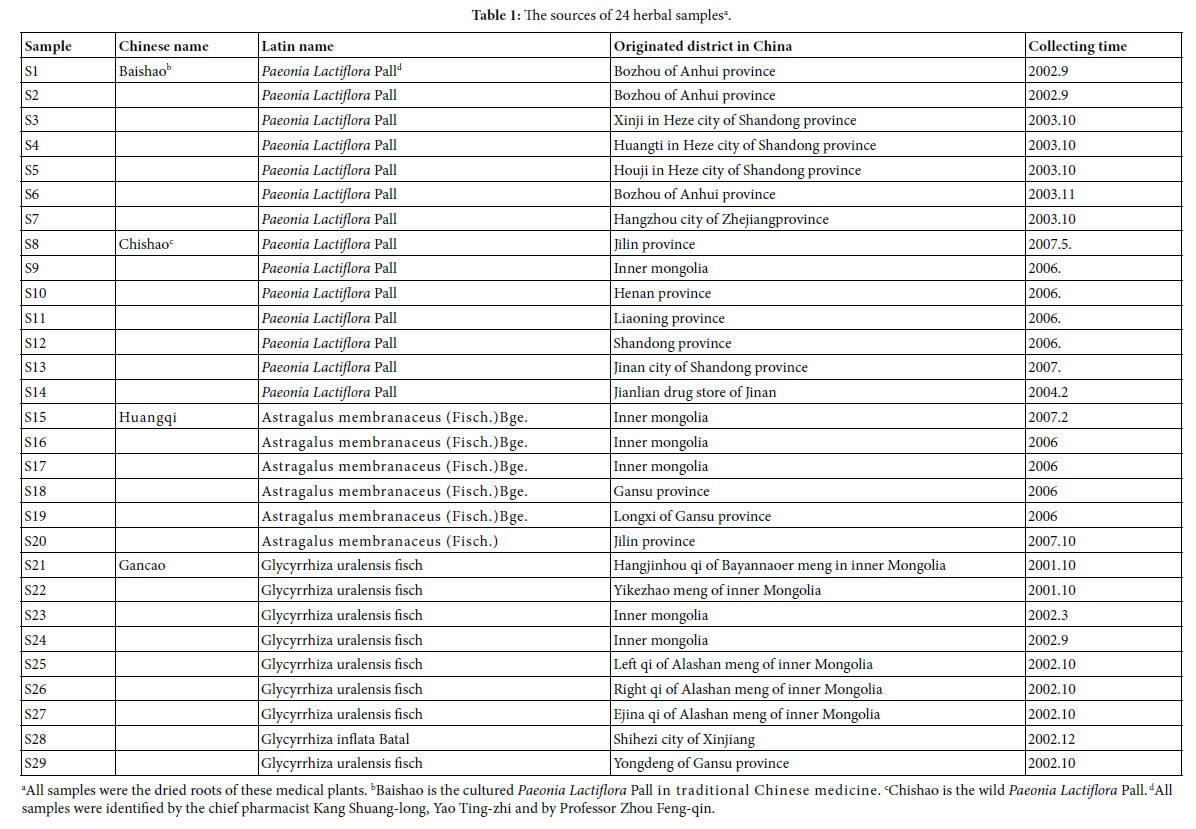

, or is precisely equal to  was derived from generally biological heredity and variation information equation. It can be used as a strong tool for determining close relatives.

was derived from generally biological heredity and variation information equation. It can be used as a strong tool for determining close relatives.