Abstract

Background: Post-weaning diarrhea (PWD) in pigs is a worldwide economically important disease, which is frequently controlled using antibiotics. However, emergence of antimicrobial resistance in E. coli strains urges the need for alternative control measures, such as adapted feeding strategies, pre- and probiotics, organic acids, MCFAs or immunization. Different alternative control strategies such as active immunization of piglets against PWD with an E. coli F4 vaccine combined with different feeding strategies, addition of nutraceuticals (medium chain fatty acids (MCFAs), organic acids and additional fibers) or supplementation of ZnO were evaluated for their efficacy against PWD due to F4 enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (F4-ETEC) under field conditions.

Results: ZnO-supplemented piglets had a lower overall end weight and lower average daily weight gain, as compared to E. coli vaccinated piglets or piglets fed a diet with additional nutraceuticals. Piglets fed a ZnO-supplemented diet had optimal fecal and general clinical scores and the lowest number of individual antibiotic treatments. All E. coli vaccinated groups had intermediate clinical scores and a relatively low number of antibiotic treatments. However, clinical scores were much higher in the nutraceutical group, indicating more severe clinical diarrhea, which needed additional antibiotic intervention. Mortality was also significantly increased in the nutraceutical-supplemented group. The present study demonstrated the efficacy of an oral live non-pathogenic E. coli F4 vaccine (Coliprotec® F4; Elanco) for active immunization of piglets against PWD due to F4-ETEC under field conditions. Different feeding strategies (1-, 2-, and 3-phase feeding) had no significant effect on the clinical outcome and performance parameters of E. coli vaccinated piglets.

Conclusions: In many parameters, E. coli vaccination performed equal compared to the ZnO-supplemented group. In contrast, the alternative control strategy combining MCFAs, organic acids and additional fibers resulted in significant clinical diarrhea and mortality, requiring additional antibiotic treatment to control, although many other performance parameters were very similar to E. coli vaccination or ZnO supplementation. Therefore, E. coli vaccination could be one of the future preventive options to protect piglets against PWD due to pathogenic E. coli.

Keywords

F4-ETEC, PWD, E. coli F4 vaccine, performance, antibiotic reduction

Introduction

Post-weaning diarrhea (PWD) in pigs is a worldwide economically important disease [1], characterized by increased mortality, weight loss, retarded growth, increased treatment costs, higher use of antibiotics and batch variation [2-8]. Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) is regarded the most important cause of PWD. The ETEC pathotype is typically characterized by the presence of fimbrial adhesins, which mediate attachment to porcine intestinal enterocytes, and enterotoxins, which disrupt fluid homeostasis in the small intestine.

This results in mild to severe diarrhea within a few days post-weaning, associated with clinical signs of dehydration, loss of body condition (= disappearance of muscle volume) and mortality [9]. The adhesive fimbriae most commonly occurring in ETEC from pigs with PWD are F4 (K88) and F18 [9]. Other fimbriae such as F5 (K99), F6 (987P) and F41 rarely occur in E. coli isolates from PWD [9-13]. The main enterotoxins associated with porcine ETEC are heat-labile toxin (LT), heat-stable toxin a (STa) and heat-stable toxin b (STb). In some cases, both enterotoxins and a Shiga toxin (Stx2e) are produced by the pathogenic stains [9].

The disease is currently controlled using antimicrobials, although the emergence of antimicrobial resistance in E. coli strains isolated from cases of PWD urges the need for alternative control measures [14-18].

Several alternative strategies have been explored to increase intestinal health and decrease incidence of PWD due to E. coli in post- weaned piglets [19-21]. Overall, inclusion of additional dietary fiber and reduction of crude protein levels in post-weaning diets seemed to be an effective nutritional strategy that may counteract the negative effects of protein fermentation in the pig gut [20, 22-24]. Although specific fermentable carbohydrates combined with reduced crude protein content altered the microflora and fermentation patterns in the gastro-intestinal tract of post-weaned piglets, these favorable effects did not necessarily result in increased growth performance [25]. Other feeding strategies were more focused on feed consistency, thereby feeding more coarsely ground meal to the post-weaned piglets [26]. Coarsely ground feed meals change the physico-chemical conditions in the stomach, thereby increasing concentrations of organic acids which lower the pH. This promoted growth of anaerobic lactic acid bacteria and reduces survival of E. coli during passage through the stomach [26]. Fermentation of undigested dietary protein and endogenous proteins in the large intestines yield putative toxic metabolites that can impair epithelial integrity and promote enteric disorders such as PWD [27]. Incidence and severity of PWD may also be influenced by addition of probiotics to the diet, which may change the fermentation profile and thus promote gut health [28]. Furthermore, medium chain fatty acids (MCFAs) can neutralize bacterial metabolites in the small intestine [29].

From the late 1980’s onwards, several studies on zinc supply to post-weaned piglets have been performed. Several nutritional studies demonstrated the effects of dietary zinc oxide (ZnO) in the prevention and healing of PWD [30]. Therefore, ZnO has been admitted in the prevention and control of PWD at levels up to 3,000 parts per million (ppm) through the feed for a maximum of 14 days post-weaning. However, Committee for Veterinary Medicinal Products (CVMP) has recently decided that the use of ZnO in post-weaning diets should be phased out the latest by 2022 throughout the EU [31].

Therefore, other preventive strategies have recently been explored [1,32]. For an E. coli vaccination against PWD due to F4- and F18- ETEC, the prerequisite is that active mucosal immunity against F4 and F18 is mounted. This implies the local production of F4- and/or F18- specific sIgA antibodies, which prevent pathogenic F4- and F18-ETEC to attach to the intestinal F4- and F18-receptors and thus reduce clinical signs of PWD [32]. Recently, vaccination with a live non-pathogenic E. coli F4 or E. coli F4 and F18 vaccine has demonstrated efficacy against PWD due to F4-ETEC and F4- and F18-ETEC [33,34]. Immunization against the F4- and F18-ETEC pathogens resulted in decreased severity and duration of PWD clinical signs and fecal shedding of F4- and F18- ETEC [33,34]. Moreover, increased weight gain was demonstrated in piglets vaccinated with E. coli F4 vaccine [33].

Here, we report results demonstrating the efficacy of an oral live non-pathogenic E. coli F4 vaccine (Coliprotec® F4; Elanco; Greenfield, IN) for active immunization of piglets against PWD caused by F4-ETEC with different feeding strategies under field conditions. We also included a group using the current approach of 3,000 ppm ZnO during 14 days post-weaning and a group with addition of a nutraceutical concept containing MCFAs, organic acids and additional fibers.

Materials and Methods

Experimental farm description

The field trial was performed on a conventional farrow-to-finish pig farm with 600 DanBred sows in Flanders (Belgium). The farm was managed in a 4-week batch-management system (with alternately weaning) with 120 sows per production batch. This management approach has been shown to improve the health status for several respiratory pathogens [35]. Piglets were weaned at 23 days of age and housed in specifically equipped post-weaning facilities, where they were raised for 7 weeks (50 days post-weaning). The post-weaning facility was equipped with 40 pens, which could each house 16 post- weaned piglets. Dry feeders with two waterers, one on each side, were located at the pen division, thus feeding two pens with a total of 32 piglets. The pens were further equipped with fully slatted plastic floors and were heated with hot water tubes on the side walls near the air inlet. Ventilation was performed through 3 ventilation tubes and fresh air entered into the compartment directly from the outside.

ETEC diagnosis and characterization at experimental farm

The farm was selected following ETEC diagnostics during the post-weaning period. Therefore, untreated piglets (n = 10) with typical clinical signs of PWD, such as watery feces, thin belly and signs of dehydration, were sampled using rectal swabs (Sterile Transport Swab Amies with Charcoal medium; Copan Italia S.p.A., Brescia, Italy). All sampled piglets were between 3 and 5 days post-weaning. The diagnostic samples were sent to the laboratory (IZSLER, Brescia, Italy) under cooled conditions for further processing.

Specimen were processed using standard procedures for isolation and characterization of intestinal E. coli [18]. Briefly, samples were plated on selective media and on tryptose soy agar medium supplemented with 5% of defibrinated ovine blood and incubated aerobically overnight at 37°C. Haemolytic activity was evaluated and single coliform colonies were further characterized.

DNA samples were prepared from one up to five haemolytic and/ or non-haemolytic E. coli colonies and used to perform a multiplex PCR for the detection of fimbrial and toxin genes, including those encoding for F4 (K88), F5 (K99), F6 (987P), F18, F41, LT, STa, STb

and Stx2e, but not discriminating between F4ab, F4ac and F4ad. The methodology used for the identification of these virulence genes has been described previously [36]. All collected samples were positive for F4 in combination with STa, STb and LT. No other virulence factors could be detected.

Vaccination with a live non-pathogenic E. coli F4 vaccine

In order to vaccinate piglets at least 7 days before the clinical signs to mount sufficient protective local immunity in the gut [33], piglets were vaccinated at 18 days of age (5 days prior to weaning), during the suckling period. The live non-pathogenic E. coli F4 vaccine has a rapid onset of immunity (7 days) and a duration of immunity of 21 days post-vaccination, which covers the most critical period of PWD [1]. An efficacy trial using an experimental E. coli F4 challenge at 3 days post-vaccination showed reduction of the severity and duration of PWD and reduction in fecal shedding of pathogenic F4-ETEC [33]. Sows were randomly assigned to treatment (Coliprotec® F4; Elanco, Greenfield, IN) or control group based on their parity and sow number. Parities were equally distributed to both treatment groups. Piglets from sows assigned to the treatment group were vaccinated orally through drenching with 2 ml of a live non-pathogenic E. coli F4 vaccine (Coliprotec® F4; Elanco, Greenfield, IN). Piglets from sows in the control group were not treated nor vaccinated. No antibiotics were administered to piglets from 15 days of age onwards, in order to omit interference with development of protective local immunity by the E. coli F4 vaccine during the 7 days following vaccination.

Experimental design

At weaning, E. coli vaccinated piglets were randomly assigned to three groups with a different feeding strategy. The unvaccinated control piglets were randomly assigned to two groups with different preventive measures supplemented to the feed against PWD due to E. coli. Each treatment group consisted of 128 piglets divided over 8 pens with 16 piglets each. Sexes were distributed equally within and between different treatment groups. The treatment groups were randomly allocated to the different pens within the compartment in order to evenly distribute all treatments for potential interaction with specific climatic subzones within the compartment (outer walls, air inlet, central part). Details on the experimental design in relation to feeding strategies and preventive measures are given in Table 1. Piglets were weighed per pen (n = 16 piglets) at three different time-points: d0 (start), d21 (mid-term) and d50 (end). Average piglets weights were calculated based on pen weight and number of piglets present at the moment of weighing. Piglet treatment identification was blinded to both farmer and veterinarian involved in trial follow-up by letter codes (A, B, C, D, and E).

|

Table 1. Schematic description of experimental trial set-up including treatment groups and their short comprehensive description and the respective differences in feeding strategies (weaning starter, starter and grow starter; blocks in the same colour have identical compositions), addition of ZnO (3,000 ppm), supplementary nutraceuticals (MCFAs, organic acids and additional fibers) and vaccination with a live non-pathogenic E. coli F4 vaccine. |

|||||

| Treatment groups | |||||

| A | B | C | D | E | |

|

Treatment description |

1-phase / vaccine | 2-phase / vaccine | 3-phase / vaccine | 3-phase / nutriceutical | 3-phase + ZnO |

|

Weaning starter |

… | 2 kg | 5 kg | 5 kg | 5 kg |

|

Starter |

… | 8 kg | 8 kg | 8 kg | |

|

Grow starter |

… | … | … | ||

|

ZnO (14d) |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3,000 ppm |

|

Nutraceuticals |

0 | 0 | 0 | 2 kg / tonne | 0 |

|

E. coli F4 vaccine |

yes | yes | yes | no | no |

Feeding strategies

Feeding strategies were based on practical field situations, where a limited number of different feeding phases can be fed to piglets during the post-weaning period. Therefore, we decided to test 1-phase, 2-phase and 3-phase feeding strategies in combination with E. coli F4 vaccination. Unvaccinated control group were also fed the 3-phase strategy. One unvaccinated group was designed to resemble the current field situation with addition of 3,000 ppm ZnO to the feed during the first 14 days post-weaning, whereas the other unvaccinated group was formulated with 2 kg of extra protective nutritional supplements, i.e. nutraceuticals, consisting of a combination of MCFAs, organic acids and additional fibers.

Treatment

No group treatments were performed during the entire study period. Individual piglets with severe clinical signs of PWD were treated with an injectable antimicrobial, i.e. lincomycine. Other disorders were treated by the farmer, following consultation of the veterinarian, with the appropriate antimicrobial where needed. All individual treatments were registered with date, pen, product type and reason for treatment.

Performance parameters

The following performance parameters were collected during the trial: piglet weight at d0, d21 and d50, feed intake during period 1 (0- 21 days), period 2 (22-50 days) and period 3 (0-50 days), individual treatments with specific reason for treatment, mortality with date of death (number of days in trial) and piglet weight. Average daily weight gain (ADWG) was calculated based on piglet weight and number of days in trial for period 1 (0-21 days), period 2 (22-50 days) and period 3 (0-50 days). Feed conversion rate (FCR), the amount of feed to add one kg of bodyweight, was calculated based on average daily weight gain and feed intake for period 1 (0-21 days), period 2 (22-50 days) and period 3 (0-50 days). Treatment incidence 50 (TI50) was calculated based on the number of individual injections per treatment for a total of 100 piglets over the

trial duration of 50 days.

Pen fecal clinical score and general clinical score

Piglet feces consistency was scored daily from d0 to d21 using pen fecal clinical score (FCS) as described in Table 2. FCS was performed by the same person throughout the entire duration of the trial observation (0-21 days). Piglets were also scored on general appearance using a general clinical score (GCS), ranging from 0 (= severe clinical condition) to 10 (= excellent clinical condition). For both pen FCS and GCS, one score per pen was attributed daily in the morning at 9 am. For analysis, area under the curve (AUC) and time to maximal score was calculated per pen for both pen FCS and GCS. Clinical assessment of piglets with diarrhea was performed based on appearance of fluid watery stools in the anal and perineal region. The number of piglets per pen with these clinical signs was counted daily from d0 to d21 and reported as total number of piglets with diarrhea per treatment group over the entire observation period (0-21 days).

|

Table 2. Comprehensive description of the pen fecal clinical score with its interpretation and the clinical aspect of the fecal clinical score. |

||

|

Score |

Interpretation |

Clinical aspect |

|

0 |

Normal |

Normal fecal consistency |

|

1 |

Pasty |

Soft pasty consistenty |

|

2 |

Mild |

Presence of fluid, but more particles than fluid |

|

3 |

Moderate |

More fluid than particles |

|

4 |

Severe |

Fluid watery faeces |

Statistical analysis

For the continuous data, effect of treatment was assessed using pairwise comparison using t-test with pooled standard deviations. For the ordinal outcomes, effect of treatment was assessed using pairwise comparison using Wilcoxon rank sum test. The P-values were adjusted with the Bonferroni method for multiple comparison. All tests were performed at the nominal level of 5%.

Results

Piglet weight and average daily weight gain

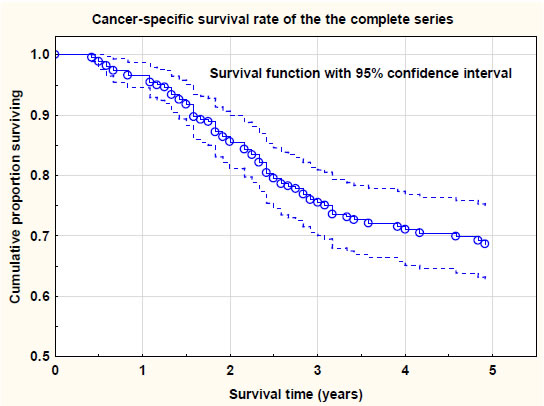

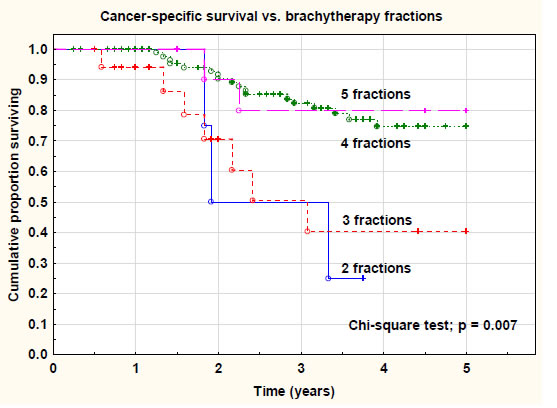

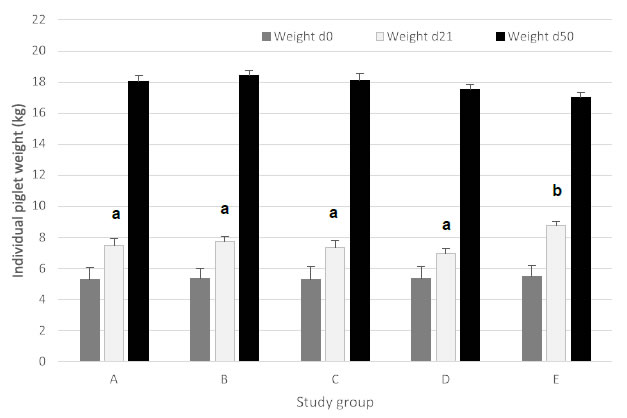

On d0, average individual piglet weight was not significantly different among treatment groups, indicating an equal starting weight in all groups. At the mid-point weighing (d21), group E (ZnO) had a significantly higher (P < 0.05) weight as compared to the other treatment groups. In contrast with its higher mid-point weight at d21, group E (ZnO) had the lowest numerical average individual piglet weight at d50, although no significant differences (P > 0.05) were present between all treatment group (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Average individual piglet weight (expressed in kg; mean ± SEM) for piglets at d0 (start of trial), d21 (mid-point weighing) and d50 (end of trial). Different treatment groups differed in feeding strategy and vaccination status against E. coli F4. Groups A, B, and C were vaccinated with Coliprotec® F4 at 18 days of age and combined with a 1, 2, or 3-phase feeding strategy. Group D was fed a 3-phase feeding strategy combined with additional nutraceutical protection, and Group E was fed a 3-phase feeding strategy with supplementation of 3,000 ppm ZnO for the first 14 days post-weaning. Different superscript letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

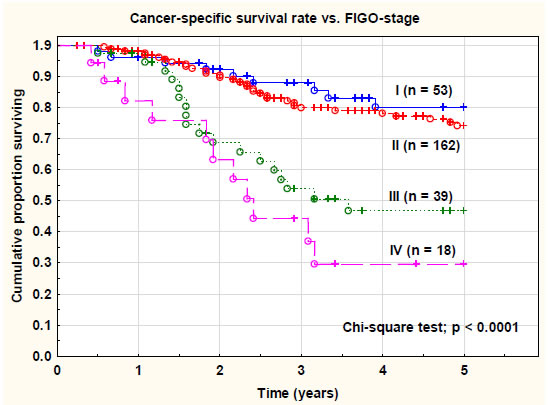

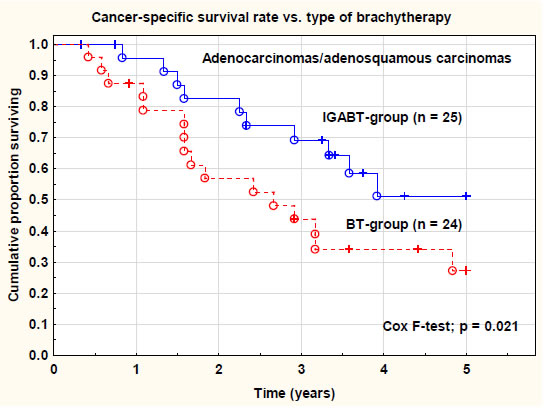

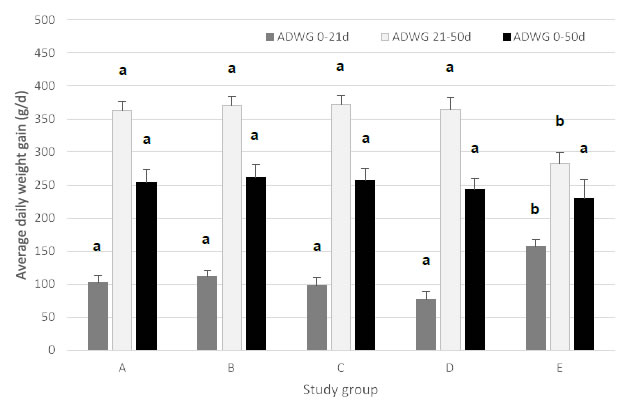

For period 1 (0-21 days), group E (ZnO) had a significantly higher (P < 0.05) ADWG as compared to the other treatment groups. The piglets vaccinated with the E. coli F4 vaccine grew equally well, whereas group D (nutraceuticals) slightly, though not significantly, underperformed, as compared to the E. coli vaccinated groups A, B, and C. For period 2 (22-50 days), group E had a significantly lower (P < 0.05) ADWG of 283 g/day compared to all other treatment groups, whereas E. coli vaccinated piglets in group A, B, and C grew 363 to 372 g/day. During this period, group E also had a significantly lower (P < 0.05) ADWG as compared to group D. Overall ADWG (0-50 days) was not significantly different among the different treatment groups (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Average daily weight gain (ADWG; expressed in g/d; mean ± SEM) for piglets during period 1 (0-21 days post-weaning), period 2 (22-50 days post-weaning) and period 3 (0-50 days post-weaning). Different treatment groups differed in feeding strategy and vaccination status against E. coli F4. Group A, B, and C were vaccinated with Coliprotec® F4 at 18 days of age and combined with a 1, 2, or 3-phase feeding strategy, respectively. Group D was fed a 3-phase feeding strategy combined with additional nutraceutical protection, and Group E was fed a 3-phase feeding strategy with supplementation of 3,000 ppm ZnO for the first 14 days post-weaning. Different superscript letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

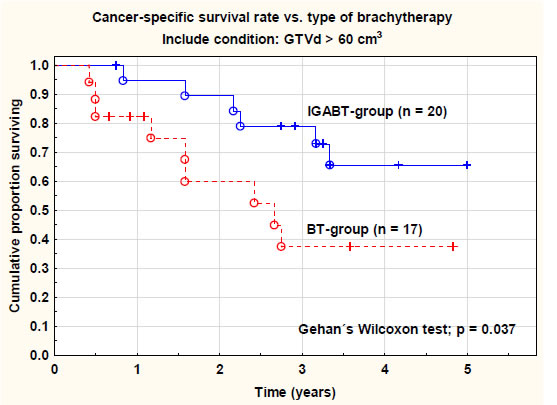

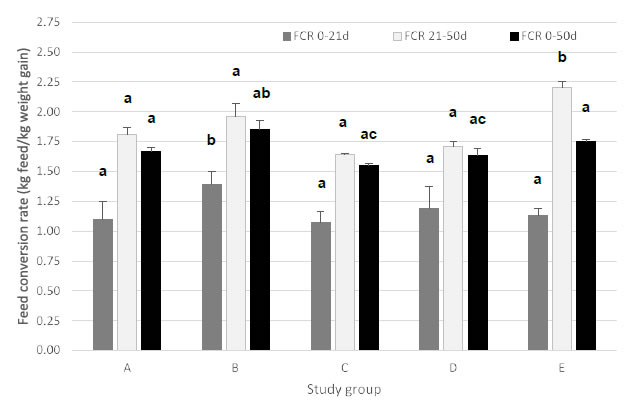

Figure 3. Feed conversion rate (FCR; expressed in kg of feed per kg of weight gain; mean ± SEM) for piglets during period 1 (0-21 days post-weaning), period 2 (22-50 days post- weaning) and period 3 (0-50 days post-weaning). Different treatment groups differed in feeding strategy and vaccination status against E. coli F4. Group A, B, and C were vaccinated with Coliprotec® F4 at 18 days of age and combined with a 1, 2, or 3-phase feeding strategy, respectively. Group D was fed a 3-phase feeding strategy combined with additional nutraceutical protection and Group E was fed a 3-phase feeding strategy with supplementation of 3,000 ppm ZnO for the first 14 days post-weaning. Different superscript letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

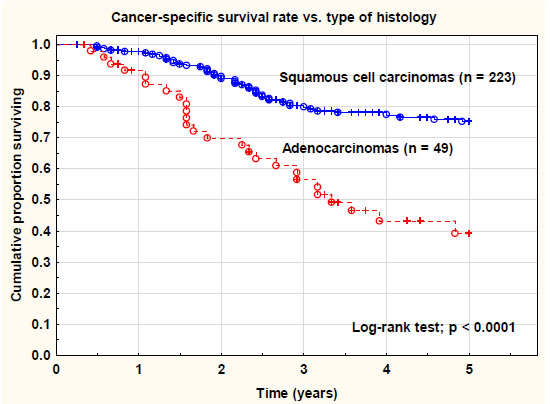

Feed conversion rate

For period 1 (0-21 days), group B (2-phase feeding) had a significantly higher (P < 0.05) FCR as compared to the other treatment groups. During period 2 (22-50 days), both group B (2-phase feeding) and group E (ZnO) had a significantly higher (P < 0.05) FCR as compared to groups A, C, and D. Overall FCR (0-50 days) was significantly higher (P < 0.05) in group B (2-phase feeding) as compared to group C (3-phase feeding) and group D (nutraceuticals). None of the other groups was significantly different from each other.

Pen fecal clinical score and general clinical score

Pen FCS was collected daily for each individual pen from 0 to 21 days post-weaning. Pen FCS, expressed as AUC, was not significantly different (P > 0.05) among E. coli vaccinated groups (A, B and C). However, pen FCS of group E (ZnO) was significantly lower (P < 0.05) as compared to group D (nutraceuticals). Pen FCS of group E (ZnO) was significantly lower (P < 0.05) as compared to all E. coli vaccinated groups (Table 3). Although some numerical differences in time to maximal FCS occurred among different treatment groups, no significant differences (P > 0.05) could be observed in the time to maximal FCS (Table 3).

|

Table 3. Area under the curve (AUC) of pen fecal clinical score and pen general clinical score (GCS), time to maximal FCS and GCS (mean ± SEM) for piglets during the first 21 days post-weaning and treatment incidence 50 (TI50; # individual treatment/100 piglets/50 days in trial; mean ± SEM). Pen FCS was scored daily on a score from 0 (= normal) to 4 (= watery diarrhea) and GCS was scored daily on a score from 0 (= very bad) to 10 (= excellent). Different treatment groups differed in feeding strategy and vaccination status against E. coli F4. Group A, B, and C were vaccinated with Coliprotec® F4 at 18 days of age and combined with a 1-2 or 3-phase feeding strategy, respectively. Group D was fed a 3-phase feeding strategy combined with additional nutraceutical protection and Group E was fed a 3-phase feeding strategy with supplementation of 3,000 ppm ZnO for the first 14 days post-weaning. Different superscript letters indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05). |

|||||

|

Treatment group |

|||||

|

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

|

|

Pen FCS |

42.9 ± 2.97 a |

41.6 ± 2.08 ac |

43.1 ± 2.18 ad |

52.6 ± 1.84 ad |

15.8 ± 1.72 b |

|

Time to maximal FCS |

6.25 ± 0.59 |

6.50 ± 0.68 |

7.25 ± 0.56 |

6.62 ± 0.60 |

5.62 ± 0.65 |

|

Pen GCS |

175 ± 3.96 a |

187 ± 1.55 ac |

176 ± 2.76 a |

164 ± 3.04 ac |

204 ± 1.79 bd |

|

Time to maximal GCS |

8.12 ± 0.61 a |

6.12 ± 0.66 a |

7.12 ± 0.61 a |

7.62 ± 0.75 a |

5.50 ± 0.38 a |

|

# piglets with diarrhea (0-21 d) |

76 a |

73 a |

105 a |

315 b |

11 c |

|

TI50 |

1.21 ± 0.18 a |

1.16 ± 0.14 ab |

1.67 ± 0.30 ab |

5.00 ± 1.05 c |

0.17 ± 0.01 b |

The number of piglets with clinical signs of diarrhea was significantly higher (n = 315; P < 0.05) in group D (nutraceuticals) as compared to the E. coli vaccinated groups. No significant differences were observed among the E. coli vaccinated groups (A, n = 76; B, n = 73; C, n = 105). Group E (ZnO) had a significantly lower number (n = 11; P < 0.05) of piglets with clinical diarrhea as compared to all E. coli vaccinated groups (A, B, and C) (Table 3).

Pen GCS was collected daily for each individual pen from 0 to 21 days post-weaning. AUC of pen GCS was significantly better (P < 0.05) in group E (ZnO) as compared to all other treatment groups. Group B (2-phase feeding) had a significantly better (P < 0.05) pen GCS as compared to group A (1-phase feeding), C (3-phase feeding) and D (nutraceuticals) (Table 3). Although some numerical differences in time to maximal GCS occurred between the different treatment groups, no significant differences (P > 0.05) could be observed (Table 3).

Treatment incidence 50

TI50 was calculated as the total number of individual treatments per 100 piglets per group over 50 days of trial. In group D (nutraceuticals), TI50 was significantly higher (P < 0.05) as compared to the other treatment groups. Group E (ZnO) had the lowest TI50, although the addition of 3,000 ppm ZnO was not taken into account in this calculation (Table 3). All E. coli vaccinated groups had equally low and non-significantly different (P > 0.05) TI50 values.

Mortality

Data related to mortality are given in Table 4. In summary, group D (nutraceuticals) had the highest percentage of overall mortality with 12.5%, which was nearly double the mortality percentage of group E (ZnO) and triple the mortality percentage in the vaccinated groups (A, B, and C). Moreover, piglets in group D (nutraceuticals) died early post-weaning (9.83 days post-weaning), mostly due to acute to subacute PWD. Mortality in group E (ZnO) occurred in period 2 (22- 50 d), after removal of 3,000 ppm ZnO from the diet at 14 days post- weaning. This was characterized by the highest mortality weight (11.56 kg) for period 2 (22-50 d). Mortality in the E. coli vaccinated groups (A, B, and C) was equally distributed among both periods and was very limited in numbers (n = 4-6 dead piglets per group) compared to both other groups (D and E).

|

Table 4. Mortality results per treatment group and study period with number of dead piglets per group (percentage of total piglets enrolled in the group), average weight of the dead piglets (kg; |

||||||

|

Study period |

||||||

|

Period 1 (0-21 d post-weaning) |

Period 2 (22-50 d post-weaning) |

|||||

|

Treatment group |

Mortality – number (%) |

Average weight dead piglets (kg; avg ± SEM) |

Average days post- weaning (d; avg ± SEM) |

Mortality – number (%) |

Average weight dead piglets (kg; avg ± SEM) |

Average days post-weaning (d; avg ± SEM) |

|

A |

2 (1.56%) |

6.00 ± 1.00 |

21.0 ± 0.0 |

4 (3.13%) |

8.75 ± 1.11 |

35.2 ± 1.9 |

|

B |

2 (1.56%) |

4.50 ± 0.50 |

14.0 ± 5.0 |

3 (2.34%) |

13.00 ± 5.00 |

40.7 ± 4.6 |

|

C |

3 (2.34%) |

4.00 ± 0.58 |

17.3 ± 2.7 |

1 (0.78%) |

8.00 ± 0.00 |

25.0 ± 0.0 |

|

D |

12 (6.67%) |

4.17 ± 0.34 |

9.8 ± 1.6 |

4 (3.12%) |

7.00 ± 3.67 |

30.4 ± 3.8 |

|

E |

0 (0.00%) |

N/A |

N/A |

9 (7.03%) |

11.56 ± 1.32 |

39.8 ± 2.3 |

Discussion

From the current study, we can conclude that active immunization of piglets against PWD caused by F4-ETEC performed at an acceptable level as compared to the standard approach under field conditions with addition of 3,000 ppm ZnO during the first 14 days post-weaning. Although average individual piglet weight at 22 days post-weaning was significantly lower as compared to the ZnO-supplemented group (E), piglets vaccinated with the E. coli F4 vaccine were numerically heavier (1.0 to 1.4 kg extra) at the end of the nursery period (d50). Under field conditions, an extra kg of piglet weight during the nursery period is considered to result in at least 2-3 kg extra weight during the fattening period. This implies earlier slaughter at the same weight or heavier fattening pigs at the same slaughter age. Both scenarios mean economic benefit to the swine farmer. Average daily weight gain behaved in the same trend, although the ADWG for period 2 (22-50 d) was significantly lower in the ZnO-supplemented group (E). Under field conditions, most farmers only have access to start and end-point data related to post-weaning performances, therefore the significantly higher mid-term performance in the ZnO-supplemented group (E) is not considered relevant to practice. Nevertheless, the higher weight and better ADWG indicate that piglets supplemented with ZnO at 3,000 ppm for 14 days post-weaning might have a stable intestinal integrity and pathogenic E. coli bacteria have less impact on the performance of these piglets during the early post-weaning phase [30]. However, CVMP has recently decided that the use of ZnO in post-weaning diets should be phased out the latest by 2022 throughout the EU [31]. Therefore, alternative approaches to control PWD due to pathogenic E. coli should be explored. Several alternative strategies, such as adapted nutritional strategies (feed consistency, lower crude protein, digestible fibers and other dietary fibers), prebiotics, probiotics, organic acids, MCFAs, specific IgA antibodies and oral vaccination have been explored [19-29,33,34,37-40].

In the current study, a nutraceutical approach, including a mixture of MCFAs, organic acids and additional fiber, was evaluated. Although performance parameters (weight, ADWG and FCR) were in line with the E. coli vaccinated groups and supplementation of ZnO, other parameters related to health (pen FCS, mortality and TI50) were significantly worse, indicating this approach did not provide as much

protection as ZnO supplementation or E. coli F4 vaccination. Indeed, intestinal pathogens have many different mechanisms to interact with the host, which makes complete inhibition of their pathogenesis through specific feed additives or a combination of these additives quite challenging [21,41].

Recently, vaccination with a live non-pathogenic E. coli F4 or E. coli F4 and F18 vaccine has demonstrated efficacy against PWD due to F4-ETEC, and F4- and F18-ETEC [33,34]. Immunization against the F4- and F18-ETEC pathogens resulted in decreased severity and duration of PWD clinical signs and fecal shedding of F4- and F18- ETEC [33,34]. Moreover, increased weight gain was demonstrated in piglets vaccinated with E. coli F4 vaccine [33]. Our results are in line with these observations, indicating that feeding regime (1-, 2- or 3-phase feeding strategy) had no impact on results induced by immunization with an E. coli F4 vaccine under field conditions. This implies that farms suffering from PWD due to F4-ETEC do not have to alter their specific feeding strategy. This is an advantage, since in most cases there are limitations in the number of available feed bins for the on-farm post-weaning facilities. From an economical point of view, however, 3-phase feeding strategies provide optimal performance parameters related to FCR.

As expected, supplementation of ZnO resulted in the lowest pen FCS and TI50 although time to maximal fecal clinical score did not differ among treatment groups. Nevertheless, from 14 days post-weaning onwards, at removal of the ZnO from the feed, pen FCS increased again, in contrast to the other groups, where pen FCS remained stable during that specific period. In practice, this phenomenon is referred to as ‘post-ZnO diarrhea’ and sometimes even needs antibiotic treatment to control. E. coli vaccinated piglets had similar pen FCS and GCS, which remain important evaluation parameters in practice, due to lack of many other directly available data for evaluation of preventive or clinical interventions to prevent or control PWD due to E. coli.

Another important evaluation parameter to assess the success of different intervention strategies in relation to PWD due to E. coli is mortality [33]. Mortality data were different among treatment groups, with acceptable levels (3.12 to 4.69%) in E. coli vaccinated piglets, and much higher levels of 7.03% to 12.5% in ZnO-supplemented and nutraceutical-supplemented groups, respectively. Analysis of mortality data per period showed early death in the nutraceutical- supplemented piglets, whereas ZnO-supplemented piglets died much later during the post-weaning period, i.e. after the removal of ZnO at 14 days post-weaning. In the E. coli vaccinated piglets, mortality was more equally distributed throughout the entire study period and significantly lower as compared to both other alternative treatments (nutraceutical- and ZnO-supplementation).

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated the efficacy of an oral live non-pathogenic E. coli F4 vaccine (Coliprotec® F4; Elanco) for active immunization of piglets against PWD due to F4-ETEC. Different feeding strategies had no significant impact on the clinical outcome and performance parameters of these vaccinated piglets. In many parameters, E. coli vaccination performed equally or better as compared to the ZnO- supplemented group. However, this approach is no longer future-proof due to EU-regulations on total ban of ZnO by 2022. Therefore, E. coli vaccination could be one of the preventive options to protect piglets against PWD due to E. coli in the near future. In contrast, the alternative strategy combining MCFAs, organic acids and additional fibers resulted in significant clinical diarrhea and mortality, requiring additional antibiotic treatment to control the disease. Nevertheless, in the nutraceutical-supplemented group, other performance parameters were similar to E. coli vaccination or ZnO supplementation.

Acknowledgements

The authors greatly acknowledge the technical staff of Innsolpigs (Aalter) for their assistance in randomization, weighing and data collection.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Field trial with Veterinary Medicinal Product approved for use in swine. No additional ethical approval needed. Consent to participate was obtained following full information of farmer on the protocol to be carried out.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Availability of data and material: The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author’s contributions: FV coordinated the entire study from study design to data collection and analysis to the manuscript. OT was involved in data analysis and manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements: The author greatly acknowledges the swine farmer and his swine veterinarian participating in the study.

Author’s information: FV is currently a Sr. Technical Advisor Swine for Benelux / UK&ROI within Elanco Animal Health. He holds a DVM, a Master in Veterinary Public Health and Food Safety, a PhD in Veterinary Sciences and a PhD in Applied Biological Sciences, oxide and is a Diplomate in the European College of Porcine Health Management. He has a specific interest in swine intestinal health and the specific approach to improve intestinal health through non- antibiotic solutions.

Abbreviations

AUC: area under the curve

CVMP: Committee for Veterinary Medicinal Products

ETEC: enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli

EU: European Union

FCS: fecal clinical score

GCS: general clinical score

LT: heat-labile toxin

MCFAs: medium chain fatty acids

ppm: parts per million

PWD: post-weaning diarrhea:

STa: heat-stabile toxin a

STb: heat-stabile toxin b

Stx2e: shiga-toxin 2e

ZnO: zinc oxide

References

- Fairbrother JM, Nadeau É, Gyles CL (2005) Escherichia coli in postweaning diarrhea in pigs: an update on bacterial types, pathogenesis, and prevention strategies. Anim Heal Res Rev 6:17-39. [crossref]

- Hoa NX, Kalhoro DH, Lu C (2013) Distribution of serogroups and virulence genes of E. coli strains isolated from porcine post weaning diarrhea in Thua Thien Hue province Vietnam. Tạp chí Công ngh Sinh học 11:665-672. [crossref]

- Lyutskanov M (2011) Epidemiological characteristics of post-weaning diarrhea associated with toxin-producing Escherichia coli in large intensive pig farms. Trakia J Sci 9:68-73.

- Svensmark B, Jorsal SE, Nielsen K, Willeberg P (1989) Epidemiological studies of piglet diarrhoea in intensively managed Danish sow herds. I. Pre-weaning diarrhoea. Acta Vet Scand 30:43-53. [crossref]

- Svensmark B, Nielsen K, Willeberg P, Jorsal SE (1989) Epidemiological studies of piglet diarrhea in intensively managed Danish sow herds. II. Post-weaning diarrhea. Acta Vet Scand 30:55-62. [crossref]

- Tubbs RC, Hurd HS, Dargatz D, Hill G (1993) Preweaning morbidity and mortality in the United States swine herd. Swine Heal Prod 1:21-28.

- USDA. Part II. Reference of Swine Health and Health Management in the United States, 2000. USDA:APHIS:VS, CEAH, National Animal Health Monitoring System, Fort Collins, CO. 2002;vol. #N355.0202.

- Zhang W, Zhao M, Ruesch L, Omot A, Francis D (2007) Prevalence of virulence genes in Escherichia coli strains recently isolated from young pigs with diarrhea in the US. Vet Microbiol 123:145-152. [crossref]

- Fairbrother JM, Gyles CL (2012) Chapter 53: Colibacillosis. In: Diseases of Swine. 10th Edition. Eds. Zimmerman JJ, Karriker LA, Ramirez A, Schwartz KJ, Stevenson GW. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 723-749.

- Chen X, Gao S, Jiao X, Liu XF (2004) Prevalence of serogroups and virulence factors of Escherichia coli strains isolated from pigs with postweaning diarrhoea in eastern China. Vet Microbiol 103:13-20. [crossref]

- Frydendahl K (2002) Prevalence of serogroups and virulence genes in Escherichia coli associated with postweaning diarrhoea and edema disease in pigs and a comparison of diagnostic approaches. Vet Microbiol 85:169-182. [crossref]

- Luppi A, Gibellini M., Gin T, Vangroenweghe F, Vandenbroucke V, Bauerfeind R, Bonilauri P, Labarque G, Hidalgo Á (2016) Prevalence of virulence factors in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolated from pigs with post-weaning diarrhea in Europe. Porcine Health Manag 2:20-25. [crossref]

- Vu-Khac H, Holoda E, Pilipcinec E, Blanco M, Blanco JE, Mora A, Dahbi G, Lopéz C, González EA, Blanco J (2006) Serotypes, virulence genes, and PFGE profiles of Escherichia coli isolated from pigs with postweaning diarrhoea in Slovakia. BMC Vet Res 2:13-20. [crossref]

- Abraham S, Trott DJ, Jordan D, Gordon DM, Groves MD, Fairbrother JM, Smith MG, Zhang R, Chapman TA (2014) Phylogenetic and molecular insights into the evolution of multidrug-resistant porcine enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in Australia. Int J Antimicrob Agents 44:105–111. [crossref]

- Abraham S, Jordan D, Wong HS, Johnson JR, Toleman MA, Wakeham DL, Gorden DM, Turnidge JD, Mollinger JL, Gibson JS, Trott DJ (2015) First detection of extended-spectrum cephalosporin- and fluoroquinoloneresistant Escherichia coli in Australian food-producing animals. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 3:273-277.

- Boyen F, Vangroenweghe F, Butaye P, De Graef E, Castryck F, Heylen P, Vanrobaeys M, Haesebrouck F (2010) Disk prediffusion is a reliable method for testing colistin susceptibilitys in porcine E. coli strains. Vet Microbiol 144:359-362. [crossref]

- Jahanbakhsh S, Smith MG, Kohan-Ghadr HR, Letellier A, Abraham S, Trott DJ, Fairbrother JM (2016) Dynamics of extended-spectrum cephalosporin resistance in pathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from diseased pigs in Quebec, Canada. Int J Antimicrob Agents 48:194-202. [crossref]

- Luppi A, Bonilauri P, Dottori M, Gherpelli Y, Biasi G, Merialdi G, Maioli G, Martelli P (2013) Antimicrobial resistance of F4+ Escherichia coli isolated from swine in Italy. Transbound Emerg Dis 62:67–71. [crossref]

- Jha R, Berrocoso JD (2015) Review: dietary fiber utilization and its effects on physiological functions and gut health of swine. Animal 9:1441-1452. [crossref]

- Jha R, Berrocoso JFD (2016) Dietary fiber and protein fermentation in the intestine of swine and their interactive effects on gut health and on the environment: a review. Anim Feed Sci Technol 212:18-26.

- Tran THT, Everaert N, Bindelle J (2018) Review on the effects of potential prebiotics on controlling intestinal enteropathogens Salmonella and Escherichia coli in pig production. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 102:17-32. [crossref]

- Heo JM, Kim JC, Hansen CF, Mullan BP, Hampson DJ, Pluske JR (2009) Feeding a diet with decreased protein content reduces indices of protein fermentation and the incidence of postweaning diarrhea in weand piglets challenged with an enterotoxigenic strain of Escherichia coli. J Anim Sci 87:2833-2843. [crossref]

- Hermes RG, Molist F, Ywazaki M, Nofrarias M, Gomes de Segura A, Gasa J, Pérez JF (2009) Effect of dietary level of protein and fiber on the productive performance and health status of piglets. J Anim Sci ;87:3569-3577. [crossref]

- Pieper R, Villodre Tudela C, Taciak M, Bindelle J, Pérez JF, Zentek J (2016) Health relevance of intestinal protein fermentation in young pigs. Anim Health Resh Rev 17:137-147. [crossref]

- Bikker P, Dirkzwager A, Fledderus J, Trevisi P, le Huërou-Luron I, Lallès JP, Awati A (2006) The effect of dietary protein and fermentable carbohydrates levels on growth performance and intestinal characteristics in newly weaned piglets. J Anim Sci 84:3337-3345. [crossref]

- Mikkelsen LL, Naughton PJ, Hedemann MS, Jensen BB (2004) Effects of physical properties of feed on microbial ecology and survival of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium in the pig gastro-intestinal tract. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:3485-3492. [crossref]

- Htoo JK, Araiza BA, Sauer WC, Rademacher M, Zhang Y, Cervantes M, Zijlstra RT (2007) Effect of dietary protein content on ileal amino acid digestibility, growth, performance, and formation of microbial metabolites in ileal and cecal digesta of early-weaning pigs. J Anim Sci 85:3303-3312. [crossref]

- Escobar Garcia K, Reis de Souza TC, Mariscal Landin G, Aguilera Barreyro A, Guadalupe Bernal Santos M, Guadalupe Gomez Soto J (2014) Microbial fermentation patterns, diarrhea incidence and performance in weaned piglets fed a low protein diet supplemented with probiotics. Food Nutr Sci 5:1776-1786.

- Zentek J, Buchheit-Renko S, Männer K, Pieper R, Vahjen W (2012) Intestinal concentrations of free and encapsulated dietary medium-chain fatty acids and effects on gastric microbial ecology and bacterial metabolic products in the digestive tract of piglets. Arch Anim Nutr 66:14-26. [crossref]

- Poulsen HD (1995) Zinc oxide for weanling pigs. Acta Agric Scand 45:159-165.

- European Medicinal Agency (2017) Questions and answers on veterinary medicinal products containing zinc oxide to be administered orally to food producing species. Outcome of a referral procedure under Article 35 of Directive 2001/82/EC (EMEA/ V/A/118). EMA/394961/2017.

- Melkebeek V, Goddeeris BM, Cox E (2013) ETEC vaccination in pigs. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 152:37-42. [crossref]

- Fairbrother JM, Nadeau E., Bélanger L, Tremblay C-L, Tremblay D, Brunelle M, Wolf R, Hellmann K, Hidalgo A (2017) Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a single-dose live non-pathogenic Escherichia coli oral vaccine against F4-positive enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli challenge in pigs. Vaccine 35:353-360. [crossref]

- Nadeau E, Fairbrother JM, Zentek J, Bélanger L, Tremblay D, Tremblay C-L, Röhe I, Vahjen W, Brunelle M, Hellmann K, Cvejíc D, Brunner B, Schneider C, Bauer K, Wolf R, Hidalgo A (2017) Efficacy of a single oral dose of a live bivalent E. coli vaccine against post-weaning diarrhea due to F4 and F18-positive enterotoxigenic E. coli. Vet J 226:32-39. [crossref]

- Vangroenweghe F, Suls L, Van Driessche E, Maes D, De Graef E (2012) Health advantages of transition to batch management system in farrow-to-finish pig herds. Veterinarni Medicina, 57:83-91.

- Casey TA, Bosworth BT (2009) Design and evaluation of a multiplex polymerase chain reaction assay for the simultaneous identification of genes for nine different virulence factors associated with Escherichia coli that cause diarrhea and edema disease in swine. J Vet Diagn Invest 21:25–30. [crossref]

- Delisle B, Calinescu C, Mateescu MA, Fairbrother JM, Nadeau É (2012) Oral immunization with F4 fimbriae and CpG formulated with Carboxymethyl Starch enhances F4-specific mucosal immune response and modulates Th1 and Th2 cytokines in weaned pigs. J Pharm Pharm Sci 5:642-656. [crossref]

- Nguyen UV, Melkebeek V, Devriendt B, Goetstouwers T, Van Poucke M, Peelman L, Goddeeris BM, Cox E (2015) Maternal immunity enhances systemic recall immune responses upon oral immunization of piglets with F4 fimbriae. Vet Res 46:72-79. [crossref]

- Rutter JM, Jones GW (1973) Protection against enteric disease caused by Escherichia coli—a model for vaccination with a virulence determinant? Nature 242:531-532. [crossref]

- Virdi V, Palaci J, Laukens B, Ryckaert S, Cox E, Vanderbeke E, Depicker A, Callewaert N (2019) Yeast-secreted, dried and food-admixed monomeric IgA prevents gastrointestinal infection in a piglet model. Nat Biotechnol. 37:527–530. [crossref]

- Daudeling J-F, Lessard M, Beaudoin F, Nadeau E, Bissonnette N, Boutin Y, BrousseauJ-P, Lauzon K, Fairbrother JM (2011) Administration of probiotics influences F4 (K88)-positive enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli attachment and intestinal cytokine expression in weaned pigs. Vet Res 42:69-79. [crossref]