DOI: 10.31038/JMG.2020313

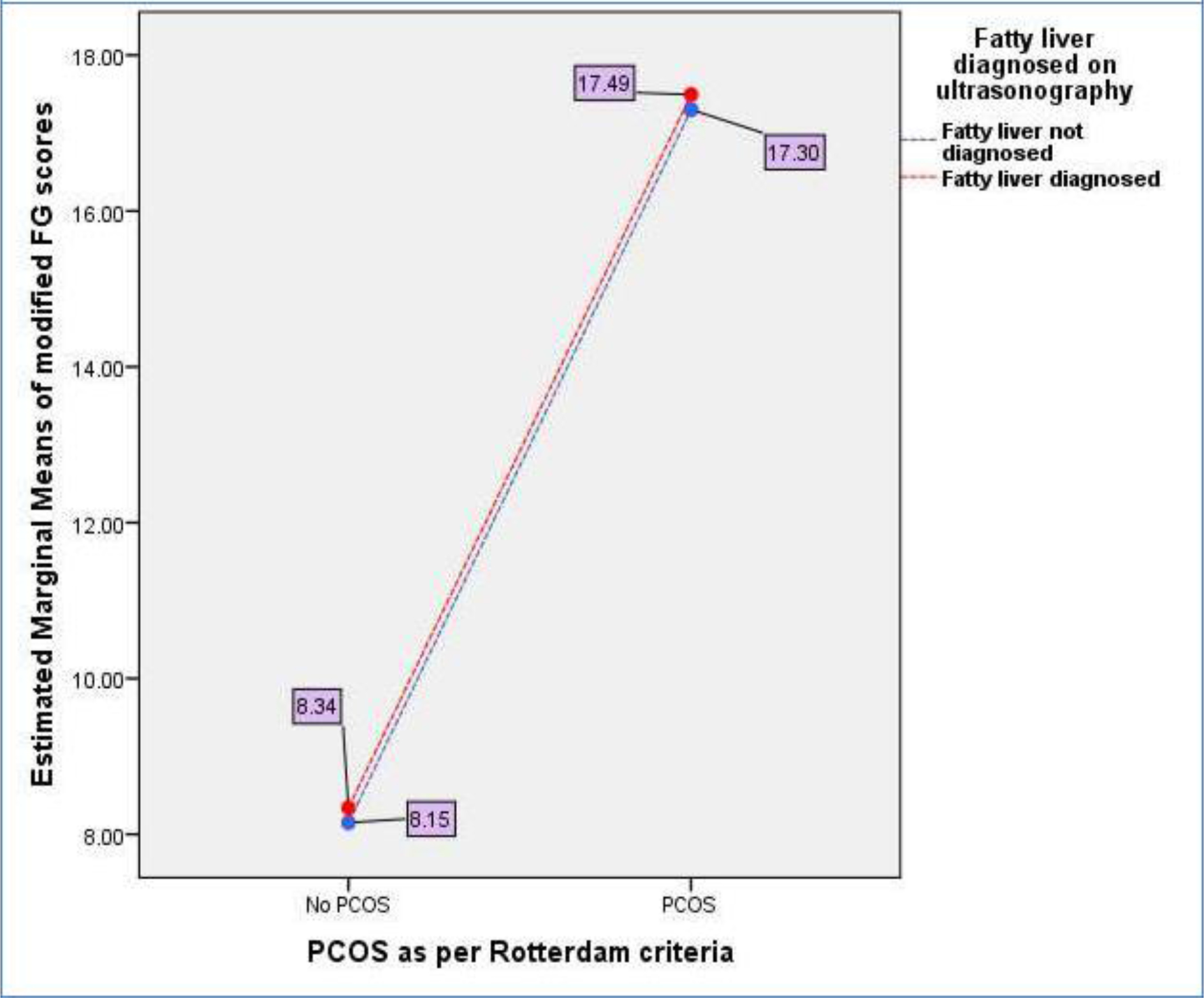

Abstract

Congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) are serious birth defects that occur in ~1:1000 pregnancies. Mutations in ~40 different genes are likely to account for these disorders. However, because mutations in unique genes affect a small number of patients with variable penetrance and expressivity, identification of causative genes has been challenging. We identified six novel candidate CAKUT genes in regions of genomic imbalance and showed pronephric phenotypes when gene expression was reduced in zebrafish.

Introduction

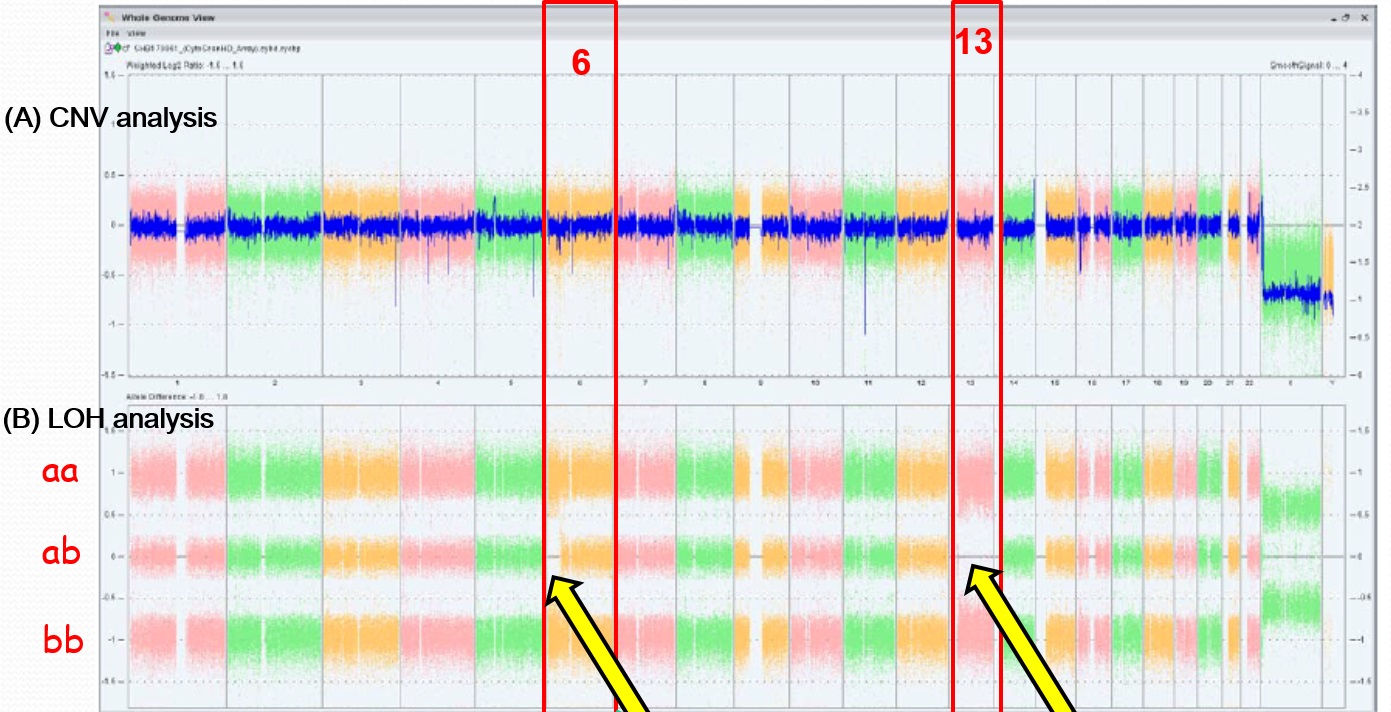

Congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) are the most common cause of chronic kidney disease in children. They account for ~48-59% of childhood chronic kidney disease (CKD) and 34-43% of childhood end stage kidney failure requiring dialysis and transplantation [1]. CKD in infants and children is associated with serious sequelae, including reduced life expectancy, cardiovascular disease, impaired growth and neurocognitive delay. Genetic variants contribute significantly to the pathogenesis of CAKUT [2]. Syndromic forms of CAKUT, often with extra-renal manifestations are typically monogenic disorders with high penetrance that are readily diagnosable. More challenging is identifying the genetic basis for the more common sporadic forms of CAKUT because of the high degree of locus and allelic heterogeneity, reduced penetrance and variable severity. To date, ~40 genes have been implicated in sporadic, non-syndromic CAKUT. However, this only accounts for~25% of CAKUT cases, indicating that many more genes are expected to contribute to this developmental disorder [3, 4]. Moreover, in many of these reports there are no functional data to support the pathogenicity of the candidate gene variants. It has recently been appreciated that 10-17% of CAKUT cases are attributed to copy number variations (CNVs) [5, 6]. Genes contained in these regions of chromosomal imbalance represent novel genetic causes of CAKUT. Chromosomal microarray analyses were used to identify genomic imbalances (deletions or duplications) in two cohorts of children with CAKUT [7]. Here we report results of functional analysis of 12 novel candidate CAKUT genes within regions affected by these structural variants.

Results and Discussion

We analyzed a dataset that identified CNVs in a cohort of 457 CAKUT patients, but were extremely rare or absent in several control cohorts totaling 11,787 individuals. CNVs can identify dosage-sensitive genes that are linked to phenotypes. We used the following criteria to prioritize genes to test in functional assays: expression in the mouse urogenital tract in public databases (GUDMAP, Geo) or our own studies in the mouse embryonic kidney; functional data implicating the gene in kidney formation in a model organism; a biological pathway with a strong link to kidney development. We also considered whether mutations in the gene were associated with a human congenital anomaly syndrome, with or without known urogenital tract anomalies.

We tested whether knockdown of genes disrupted by these rare CNVs in the CAKUT cohort affected formation of the pronephros in zebrafish. We queried the Zebrafish Model Organism Database (ZFIN) to identify orthologs of candidate human CAKUT genes contained within regions of genomic imbalance. We used morpholinos to test if gene knockdown affected pronephric development in transgenic fish that expressed GFP in the glomerulus [Tg(wt1b:egfp)li2] and the pronephric duct [Tg(cdh17:egfp)pt305]. Single cell embryos were injected with morpholino oligonucleotide at 0.0125-0.25 mM and were visualized by epifluorescent microscopy at 48 hours post-fertilization.

Out of twelve genes tested, knockdown of six genes showed a pronephric phenotype (table 1). PCDH15 encodes for a member of the Protocadherin protein family. The gene is mutated in Usher syndrome type 1D/F, which is associated with sensorineural hearing loss and retinitis pigmentosa (OMIM #601067). Studies of the Usher syndrome protein network has revealed important molecular links to ciliopathies, many of which are associated with nephronophthisis, a common cause of childhood chronic kidney disease [8]. HACE1 is a HECT-domain and ankyrin repeat-containing E3 ubiquitin ligase. Homozygous loss of function mutations lead to spastic paraplegia and neuro developmental delay (OMIM #616756). The gene is highly expressed in fetal kidney and its loss of expression may play a role in the pathogenesis of sporadic Wilms tumor [9, 10]. Slc8a1a encodes for a sodium calcium exchanger. Knockdown of the gene in renal epithelial cells destabilized E-cadherin and disrupted canonical Wnt signaling, thereby affecting the mesenchymal to epithelial transition, an essential step in formation of the kidney [11]. Lrp1b encodes for the low-density lipoprotein receptor related-protein 1b. Variants of this this gene are associated with insulin resistance and childhood BMI [12-14]. It has been suggested that maternal hyperglycemia in gestational diabetes results alters DNA methylation at this locus and thereby contributes to fetal metabolic reprogramming [15]. Therefore, LRPB1 may be a candidate gene involved in gene-environment interactions in conditions such as diabetes, which are associated with a higher risk of birth defects. In addition, deletion of LRP1B has been observed in adult Wilms tumor [16].

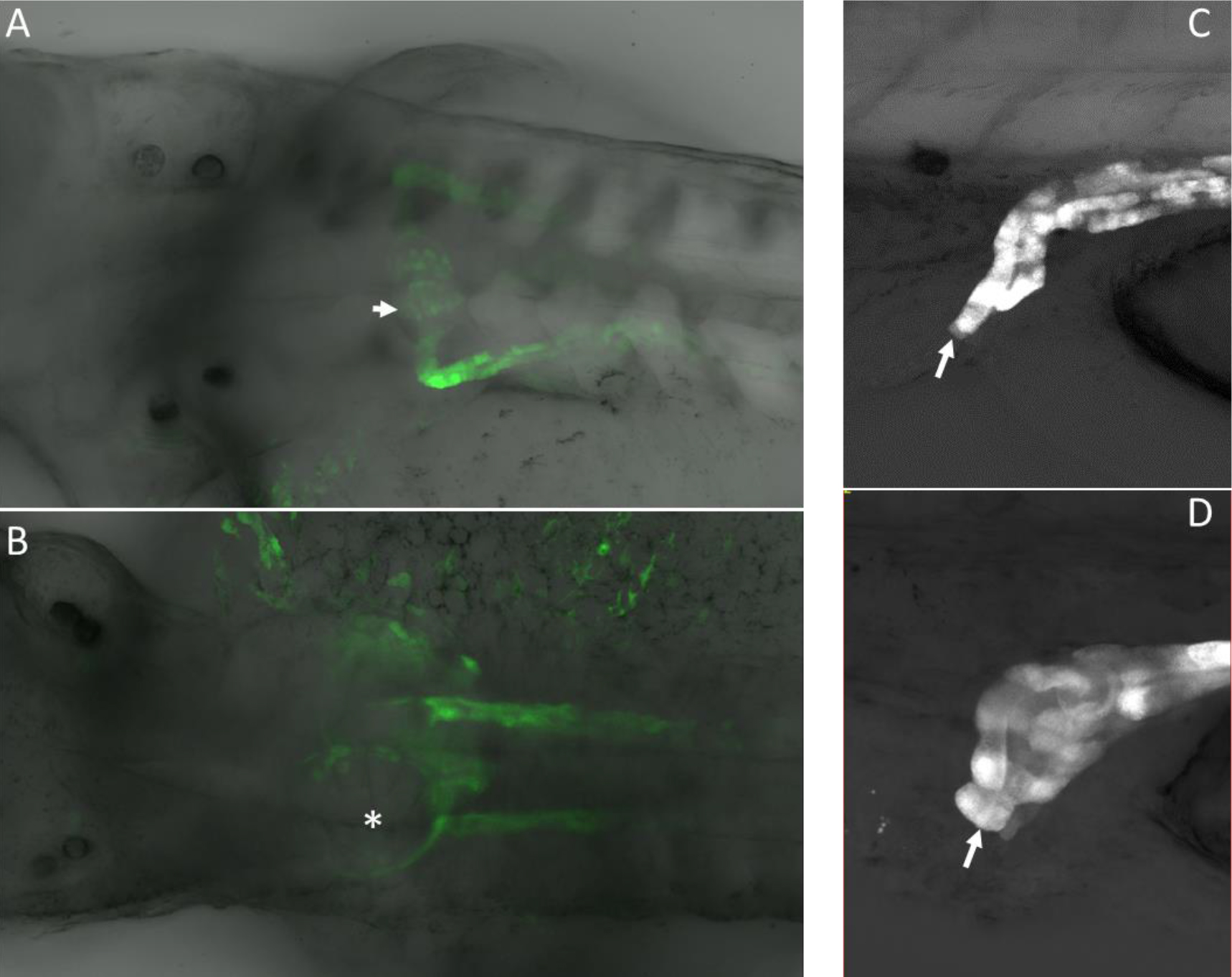

Two of the genes were studied in more detail because they are both inhibitors of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling, a pathway that is critical for kidney development in mice and humans [17]. Knockdown of Spred1 and Sprouty2 (Spry2) produced similar, dosage-sensitive phenotypes with two independent morpholinos. The observed phenotype included glomerular cysts and lack of extension of the pronephric duct leading to the absence of a patent opening at the cloaca (Figures 1, 2). Defective growth and branching of the nephric duct and ureteric bud are characteristic of mutations in the c-Ret receptor tyrosine kinase, which is essential for normal development of the mammalian kidney and lower urinary tract [17]. Spry2 plays a critical role in regulating c-Ret in developing kidney [18, 19]. Spred1 encoding for the Sprouty1-related gene product is a negative regulator of Ras-Mitogen Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) activity. Point mutations in c-RET that disrupt MAPK signaling lead to congenital anomalies affecting the kidney and lower urinary tract [20]. Mutations in SPRED1 causes Neurofibromatosis type I (Legius syndrome) which is associated with childhood renal cancer (OMIM#611431).

Table 1:

|

Morpholino |

Injection [ ] |

fish tg line |

n injected |

n affected |

96 phenotype |

phenotype description |

|

Spry2 #1 |

0.25mM |

Cdh17 |

61 |

30 |

49.2 |

CD, TR |

|

Spry2 #1 |

0.125mM |

Cdh17 and Wt1b |

180 |

26 |

14.4 |

CD, GC |

|

Spry2 #2 |

0.25mM |

Cdh17 and Wt1b |

182 |

30 |

16.5 |

CD, GC, GM |

|

Spred1 #1 |

0.125mM |

Cdh17 and Wt1b |

44 |

11 |

25.0 |

CD, GC, GM |

|

Spred1 #2 |

0.125mM |

Cdh17 and Wt1b |

12 |

2 |

16.7 |

CD |

|

Spred1 #2 |

0.0625mM |

Wt1b |

47 |

7 |

14.9 |

GC, SD |

|

Spred1 #2 |

0.0125mM |

Cdh17 and Wt1b |

33 |

17 |

51.5 |

GC, GM |

|

Pcdh15 |

0.25mM |

Cdh17 and Wt1b |

182 |

39 |

21.4 |

GC, TR, OT, SD |

|

Hace1 |

0.25mM |

Cdh17 and Wt1b |

79 |

9 |

11.4 |

GC, GM |

|

Lrp1b |

0.25mM |

Cdh17 and Wt1b |

23 |

17 |

73.9 |

CD, GC, SD |

|

Lrp1b |

0.125mM |

Cdh17 and Wt1b |

3A |

13 |

38.2 |

CD, SD |

|

SIc8a1a |

0.25mM |

Cdh17 and Wt1b |

44 |

2 |

4.5 |

GC |

CD (tubules don’t exit fish at cloacal duct), GC (glomerular cyst), GM(glomerular malformation), SD(severe developmental defect), TR(truncated tubule), OT(obstructed/enlarged tubule)

Figure 1.A. Low power images of pronephric phenotypes. Bi-transgenic fish expressing GFP under the control of the Wt1 promoter in the glomerulus and in the pronephric duct under control of the Cdh17 promoter. Uninjected fish displayed normal formation of the glomerulus and pronephric duct. B. Morpholino knockdown of Spred1 (Spred1 MO) resulted in glomerular cyst seen in Wt1 transgenic mice. C. Morpholino knockdown of Sprouty2 (Spry2 MO) resulted in a shortened pronephric duct in Cdh17 transgenic fish.

Figure 2. A. High power confocal images of pronephric phenotypes. Normal glomerulus in a control (uninjected) embryo that expressed GFP from the Wt1 promoter. B. Spred1 morpholino knockdown caused glomerular cyst formation (asterisk). C. Pronephric duct shown exiting at the cloaca (arrow). D. Blunted pronephric duct that fails to exit at the cloaca due to morpholino knockdown of Spry2 (arrow). Note the dilatation at the distal end of the pronephric duct that occurred because the duct is not patent.

In conclusion, we have identified six novel candidate CAKUT genes by combining CNV data and functional analysis in zebrafish. Validation of these genes as causative of human CAKUT awaits discovery of additional affected individuals with mutations in these genes using whole exome sequencing.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Ms Denise Smith for technical support. . We also would like to thank Drs. Tomoko Obara (Univ. Oklahoma), Christoph Englert (Fritz Lipmann Inst.) and Neil Hukriede (Univ. Pittsburgh) for sharing their wt1b and cdh17 transgenic fish lines. This work was supported by grants to M.R. from the March of Dimes (#6-FY-13–127) and NIDDK (DK098563), and President’s Research Award from Saint Louis University to M.R. and M.V.

References

- Ingelfinger JR, Kalantar Zadeh K, Schaefer F, World Kidney Day Steering Committee (2016) Averting the legacy of kidney disease:focus on childhood. Future Sci. OA.; 2(2)FSO112.

- Vivante A, Hildebrandt F (2016) Exome Sequencing Frequently Reveals the Cause of Early-Onset Chronic Kidney Disease. Nat Re Nephrol 12: 133–146. (Crossref)

- Vivante A, Hwang D-Y, Kohl S, Chen J, Shril S, et al. (2017) Exome Sequencing Discerns Syndromes in Patients from Consanguineous Families with Congenital Anomalies of the Kidneys and Urinary Tract. J Am Soc Nephro 28: 69–75. (Crossref)

- Nicolaou N, Pulit SL, Nijman IJ, Monroe GR, Feitz WF, et al. (2016) Prioritization and burden analysis of rare variants in 208 candidate genes suggest they do not play a major role in CAKUT. Kid Int 89: 476–486. (Crossref)

- Caruana G, Wong MN, Walker A, Yves Heloury Y, Webb N, et al. (2015) Copy-number variation associated with congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. Pediatr Nephol 30: 487–495. (Crossref)

- Verbitsky M, Sanna Cherchi S, Fasel DA, Levy B, Kiryluk K, et al. (2015) Genomic imbalances in pediatric patients with chronic kidney disease. J Clin Invest 125: 2171–2178. (Crossref)

- Sanna-Cherchi S, Kiryluk K, Burgess KE, Bodria M, Sampson MG, et al. (2012) Copy-number disorders are a common cause of congenital kidney malformations. Am J Hum Genet 91: 987–997. (Crossref)

- Sorusch N,Wunderlich K, Bauss K, Nagel-Wolfrum K, Wolfrum U (2014) Usher syndrome protein network functions in the retina and their relation to other retinal ciliopathies. Adv Exp Med Biol 801: 527–533. (Crossref)

- Anglesio MS, Evdokimova V, Melnyk N, Zhang L, Fernandez CV, et al. (2004) Differential expression of a novel ankyrin containing E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase, Hace1, in sporadic Wilms’ tumor versus normal kidney. Hum Mol Genet 13: 2061–2074. (Crossref)

- Jia W, Deng Z, Zhu J, Fu W, Zhu S, et al. (2017) Association between HACE1 Gene Polymorphisms and Wilms’ Tumor Risk in a Chinese Population. Cancer Invest 35: 633–638. (Crossref)

- Balasubramaniam SL, Gopalakrishnapillai A, Petrelli NJ, Barwe SP (2017) Knockdown of sodium- calcium exchanger 1 induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in kidney epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 292:11388–11399. (Crossref)

- Burgdorf KS, Gjesing AP, Grarup N, Justesen JM, Sandholt CH et al. (2012) Association studies of novel obesity-relatedgene variants with quantitative metabolic phenotypes in a population-based sample of 6,039 Danish individuals. Diabetologia 55: 105–113. (Crossref)

- Cornelis MC, Rimm EB, Curhan GC, Kraft P, Hunter DJ, et al. (2014) Obesity susceptibility loci and uncontrolled eating, emotional eating and cognitive restraint behaviors in men and women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 22: E135–E141. (Crossref)

- Namjou B, Keddache M, Marsolo K, Wagner M, Lingren T et al. (2013) EMR-linked GWAS study: Investigation of variation landscape of loci for body mass index in children. Front Genet 4. (Crossref)

- Houde AA ,Ruchat SM, Allard C, Baillargeon JP, St-Pierre J, et al. (2015) LRP1B, BRD2 and CACNA1D: new candidate genes in fetal metabolic programming of newborns exposed to maternal hyperglycemia. Epigenomics 7:1111–1122. (Crossref)

- Karlsson J, Holmquist Mengelbier L, Elfving P, Gisselsson Nord D (2011) High-resolution genomic profiling of an adult Wilms’ tumor: evidence for a pathogenesis distinct from corresponding pediatric tumors. Virchows Arch 459: 547–553. (Crossref)

- Costantini F (2010) GDNF/Ret signaling and renal branching morphogenesis: From mesenchymal signals to epithelial cell behaviors. Organogenesis 6: 252–262. (Crossref)

- Miyamoto R, Jijiwa M, Asai M, Kawai K, Ishida-Takagishi M, et al. (2011) Takahashi M. Loss of Sprouty2 partially rescues renal hypoplasia and stomach hypoganglionosis but not intestinal aganglionosis in Ret Y1062F mutant mice. Dev Biol 349: 160–168. (Crossref)

- Chi L, Zhang S, Lin Y, Prunskaite-Hyyryläinen R, Vuolteenaho R, et al. (2004) Sprouty proteins regulate ureteric branching by coordinating reciprocal epithelial Wnt11, mesenchymal Gdnf and stromal Fgf7 signalling during kidney development. Development 131: 3345–3356.(Crossref)

- Chatterjee R, Ramos E, Hoffman M, VanWinkle J, Martin DR, et al. (2012) Traditional and targeted exome sequencing reveals common, rare and novel functional deleterious variants in RET-signaling complex in a cohort of living US patients with urinary tract malformations. Hum Genet 131: 1725–1738. (Crossref)