DOI: 10.31038/PSYJ.2020214

Introduction

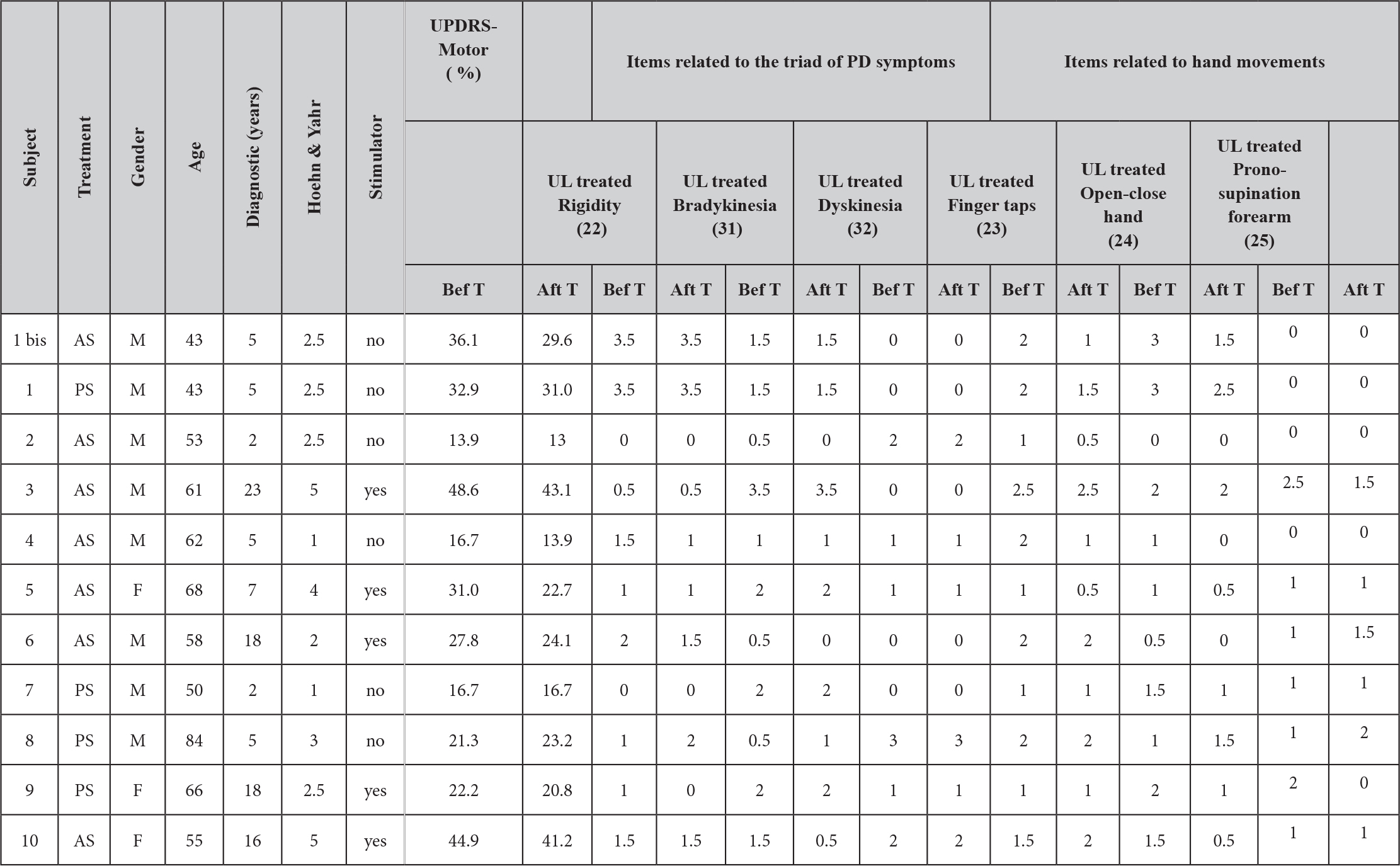

One might not think that the ubiquitous availability of cheap, easy, powerful computing power combined with storage and retrieval of information would produce in its wake better students, better minds, and the benefits of better education. The opposite is the case. As the increasing penetration of consumer electronics continues apace, it is becoming increasingly obvious that students have neither the patience to pay attention, nor the ability to think critically. A good measure of that loss of student capability comes from the popular press, where blog after blog decries the loss of thinking and, in turn, the power of education. Not to be outdone, the academic press as signaled by Google Scholar ® provides us with a strong measure of this electronics-driven loss of thinking and withering of education. Table 1 shows the year by year data.

Table 1. Concern with the loss of critical thinking – a 10-year count (Source: Google Scholar®)

|

Year

|

Loss of critical thinking

|

Experiential Learning

|

|

2010

|

9,970

|

51,300

|

|

2011

|

11,800

|

53,700

|

|

2012

|

12,300

|

58,100

|

|

2013

|

13,800

|

61,400

|

|

2014

|

14,000

|

62,000

|

|

2015

|

15,800

|

57,500

|

|

2016

|

15,300

|

48,000

|

|

2017

|

17,200

|

47,200

|

|

2018

|

17,100

|

39,300

|

|

2019

|

9,800

|

30,100

|

How then can we make education more interesting? This paper is not a review of attempts to make education more involving, more interesting, but rather presents a simple, worked approach to making learning more interesting, but really far deeper. It is obvious that children like to talk to each other about what they are doing, to present information about their discoveries, their developments, themselves. Children like experiences which resemble play, in which they are somewhat constrained, but not very much. And when a child discovers something new, something that is his or hers, the fun is all the greater because the discovery can be shared. The ingoing assumption is that if learning can be made fun, a game, with significant outputs of a practical nature, one might stimulate a love of learning which love seems to have disappeared.

Experiential learning and discovery of the new – A proposed approach based upon the emerging science of Mind Genomics

The emerging science of Mind Genomics can be considered as a hybrid of experimental psychology, consumer research, statistics, and mathematical modeling. The objective of Mind Genomics is the study of how people respond to the stimuli of the ordinary, the every day. We know from common experience that people go about their daily business almost without deeply thinking about things, in a way that Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman called System 1, or ‘thinking fast’ [1]. We also know that there are many different aspects to the same experience, such as shopping. People differ, consistently so, in when they shop, why they shop, how they get to the place where they will make a purchase, the pattern of shopping, what they shop for, and why. The variation is dramatic, the topics not so interesting, the exploration of the topics left to mind-numbing tabulations, which list the facts, rather than penetrating below, into the reasons.

Mind Genomics was developed to understand the patterns of decision making, not so much in artificial laboratory situations to develop hypotheses for limited situations, but rather to understand the decision rules of daily life. Instead of mind-numbing tables of statistics from which one gleans patterns, so-called ‘connecting the dots,’ Mind Genomics attempts to elicit these individual patterns of decision making in easy-to-do experiments. The output, once explained, fascinates the user, converting that user into an involved explorer, looking for novella, insights, and discoveries that are new to the world, discoveries ‘belonging to the student’. The day to day worlds, the ordinary, quotidian aspects of our existence, become grist for the mill of discovery. The result is that discoveries about the ordinary, discoveries that when harnessed by teachers and appreciated by students, combine experiential learning, and learning how to think critically

As noted above, Mind Genomics derives historically from psychology, consumer research, statistics, and modeling. The objective of Mind Genomics is to uncover the specific criteria by which people assign judgments. The topics are unlimited.

The empirical portion of this paper will show how experiential learning and critical thinking may be at the fingertips, with the use of simple computer programs, specifically BimiLeap, freely accessible at www.BimiLeap.com. In this paper we look at how a 14-year-old student can learn about laws and ethics, as well as the issues of daily life. The topic is taken from the way young students in a Yeshiva, a rabbinic school, can learn about the issues underlying property, specifically borrowing property and what happens when the property is somehow ‘lost.’

Experiential learning and discovery of the new

A proposed approach based upon the emerging science of Mind Genomics. Mind Genomics is an emerging science combining experimental psychology, consumer research, experimental design, and statistical modeling. The objective is to explore decision making in the everyday world.

In terms of commercial and social practice, Mind Genomics has been applied in by author HRM to issues as varied as it applies to topics as different as decision making about what we choose to eat, legal cases, and communications in medicine to improve the outcomes during and after hospitalization, respectively. These practical applications along with the ongoing stream of studies suggest Mind Genomics as a simple-to-use but powerful knowledge-creation tool. With Mind Genomics, virtually anyone can become a researcher, explore the world, classify the strategies of decision making, and discover new-to-the-world mind-sets, groups of people who think about the topic in the same way, and who differ from other groups of people thinking about the topic in a different way.

The Mind-Genomics technology has been embedded in easy-to-use computer programs, making the typical Mind Genomics study fast, affordable, and structured. The same simplicity of research, studying what is, may thus find application to educate the non-researcher, the novice, the younger student. Rather than the researcher exploring a topic area with the point of view of a person interested in the specific topic, the notion emerged that the same tool can be used to each a novice how to think, using research as a the tool, and the information and accomplishment as the reward for using the tool.

The Yeshiva approach: Havrutas (groups) studying a topic in depth

This paper presents one of the early attempts to use Mind Genomics to teach legal reasoning to a teenager, helping the teenager to make a specific topic ‘come alive’ as well as imbue experiential learning and critical thinking into the process. The paper will present the approach step by step, as a ‘vade mecum’ or ‘guide’ for the interested reader.

The objective of Mind Genomics is to understand the decision making in a situation. The deliverable is a simple table, which one can adorn in different ways, but which at its heart shows questions and answers about a situation.

We take our approach from the way students in Jewish religious schools study the corpus of Jewish law, commentary and discussion. The notion of using the Bible as a source for teaching modern concepts is not new [3]. created a course on economics, based upon biblical tests, as described in the following paragraph

The author describes a course designed to build the critical thinking skills of undergraduate economics students. The course introduces and uses game theory to study the Bible. Students gain experience using game theory to formalize events and, by drawing parallels between the Bible and common economic concepts, illustrate the pervasiveness of game-theoretic reasoning across topics within economics as well as various fields of study.

We take our source for the course in the way the Talmud is study. The Talmud comprises more than 2700 of pages of explication of basic Jew practice. The origins of the Talmud are, according to Jewish sources, founded in the Oral Law, the law of Jewish practice based in the Old Testament, the Jewish Bible, but expanded considerably. For the reader, the important thing to know is that the Talmud comprises two portions, the Mishna, a short, accessible compilation of Jewish Law and practice, finalized by Rabbi Judah the Prince around the second century CE, and then discussions of that compilations, attempting to find discrepancies to reconcile them, done by Rabbis and their students for about 300–400 years hundred years after the Mishna was finished. This section, discussion and reconciliation among sources, is embodied in difficult, occasionally tortuous material known as the Gemara, the word in Aramaic for‘completing.’

Talmud students who spend years learning the Talmud end up thinking critically [4]. The method is to pair off students with each other, havrutas, usually comprising two students, who read, decipher, debate, and struggle to understand the section together. The approach leads, when successful, to logical thinking, and ability to formulate problems ina way worthy of a lawyer. In the words of [5].

when examined closely, havruta study is a complex interaction which includes steps, moves, norms and identifiable modes of interpretative discussion [5].

Havruta learning or paired study is a traditional mode of Jewish text study. The term itself captures two simultaneous learning activities in which the Havruta partners engage: the study of a text and learning with a partner. Confined in the past to traditional yeshivot and limited to the study of Talmud, Havruta learning has recently made its way into a variety of professional and lay learning contexts that reflect new social realities in the world of Jewish learning [6].

With this very short introduction, the notion emerged from a number of discussions with psychology researchers and with students of the Talmud that perhaps one might use technology inspired by Talmudic style thinking and discussion to teach students to think critically, whether these be Talmud students embedded in the Jewish tradition, or students who could take a topic of the Talmud in an ‘edited’ form, and work with that topic in the way a yeshivastudent might.

Adapting the approach, making it accessible, challenging, interactive, and fun

The situation for this study is simple, based upon a legal case well known to many students of the Talmud, but presented in secular terms. The case concerns an item, the nature of which is unstated but the implication is that the item is something portable. The information available is:

- Who initiated the interaction?

- Why was the interaction initiated?

- Where was the interactioninitiated (viz., request made)?

- What happened to the item?

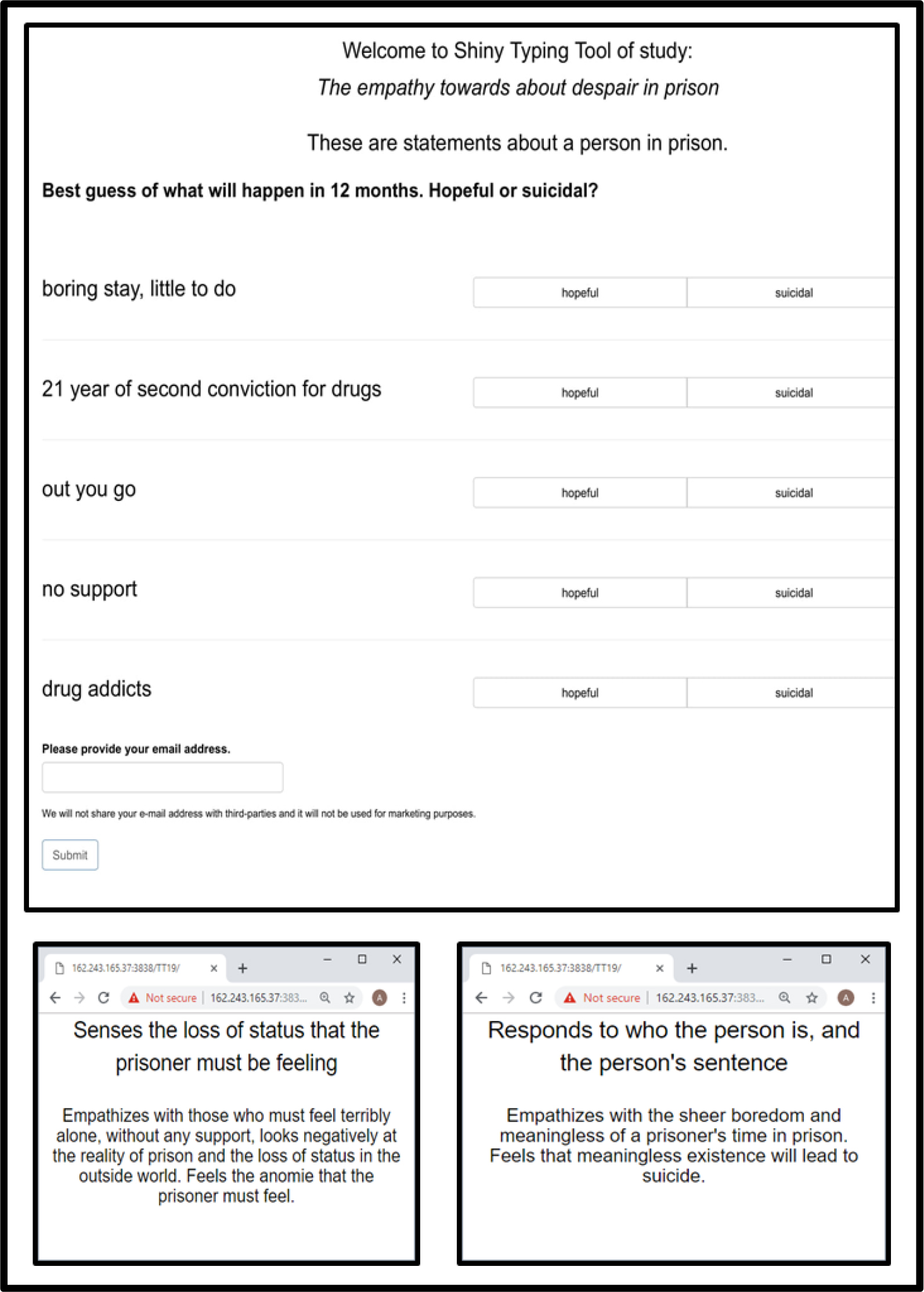

In order to make the system easy, but keep the tone serious, the design for the computer interface was created to be simple.

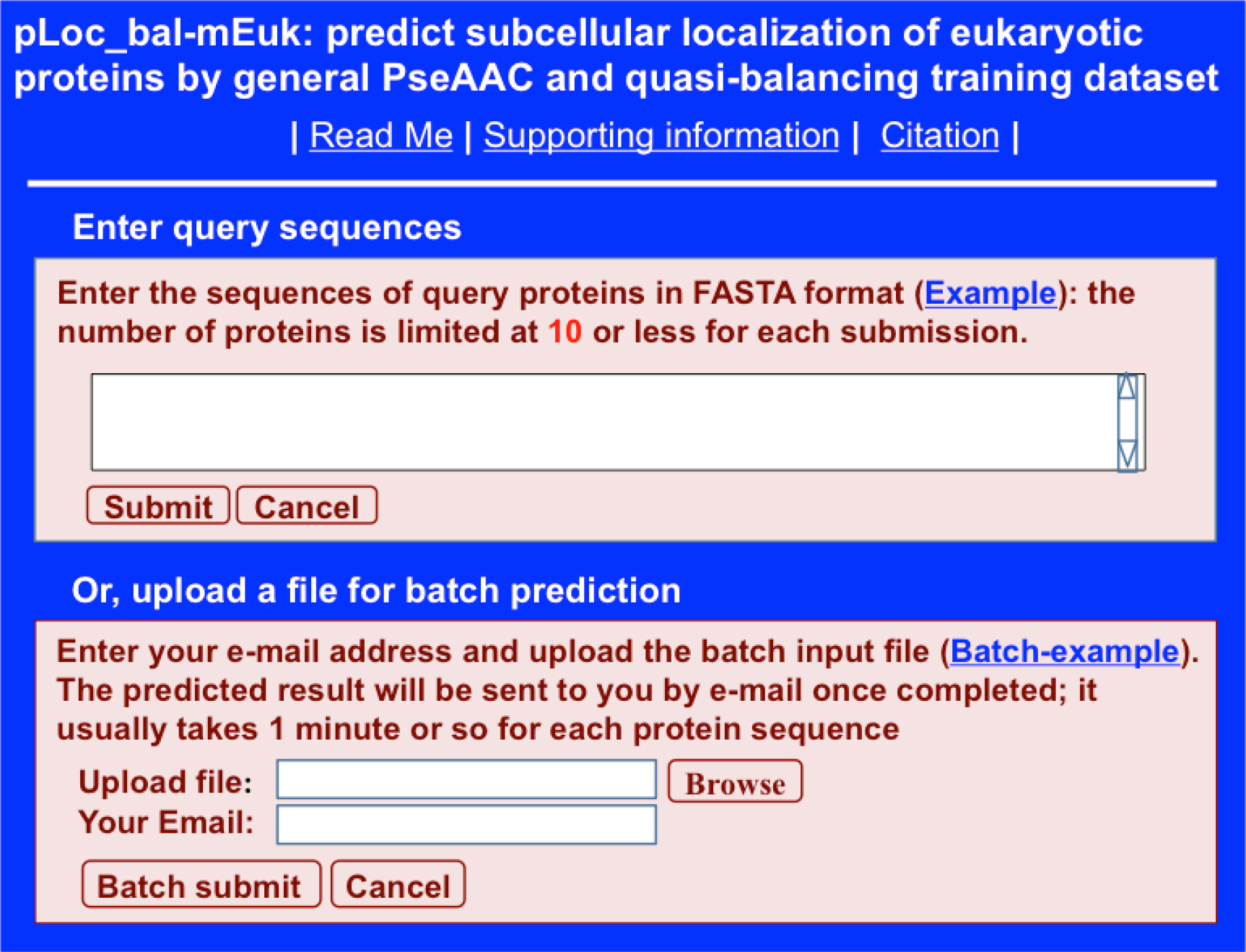

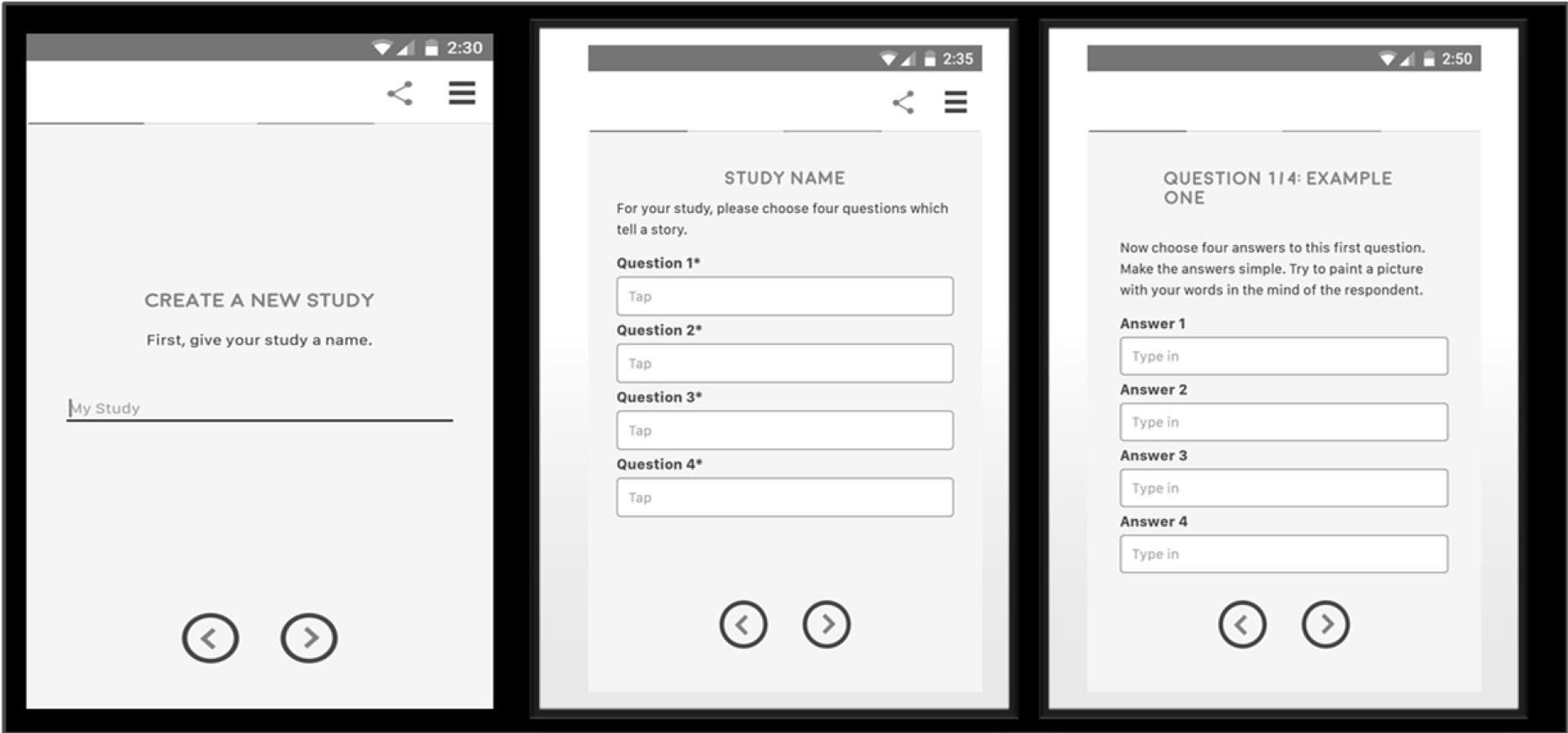

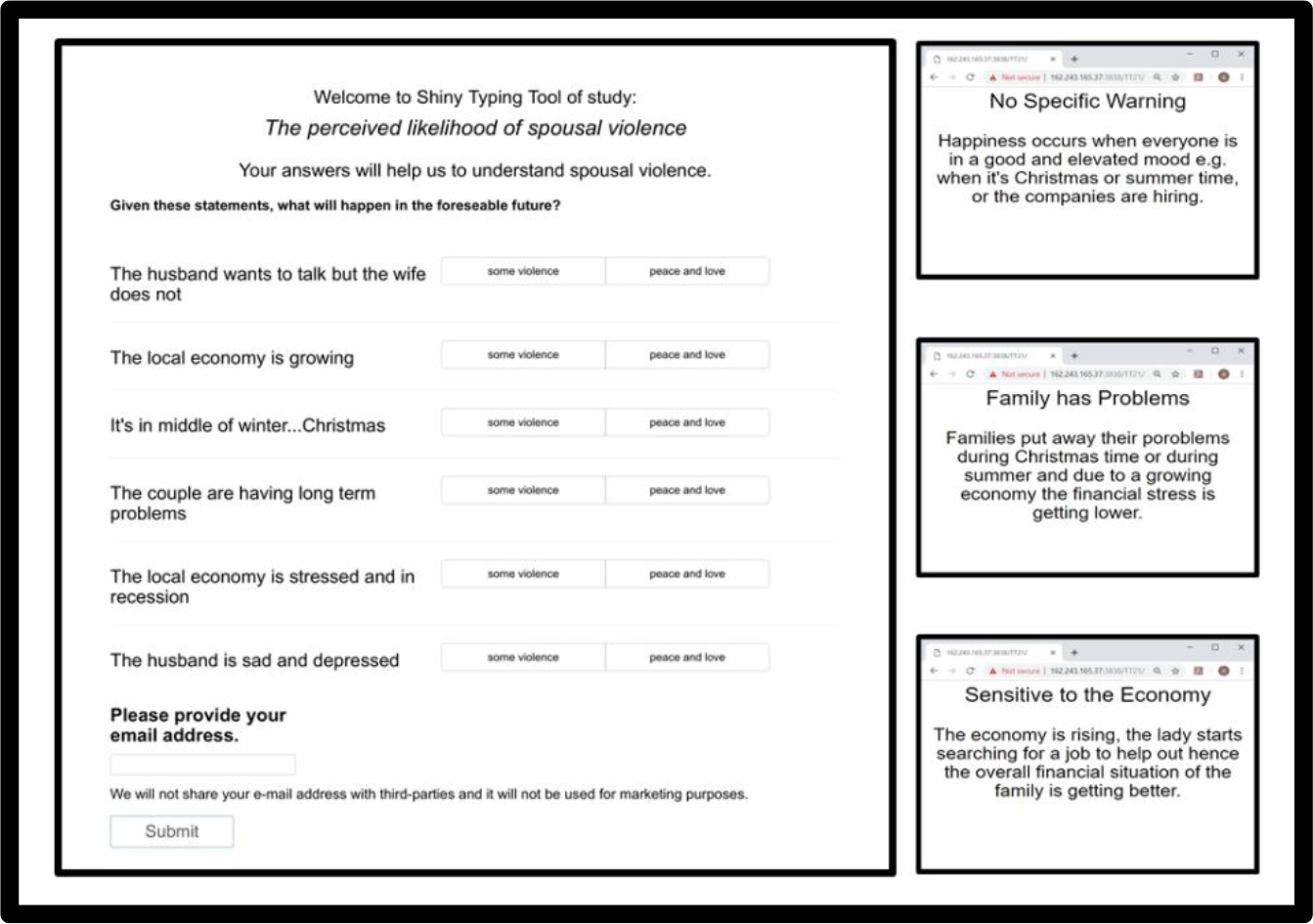

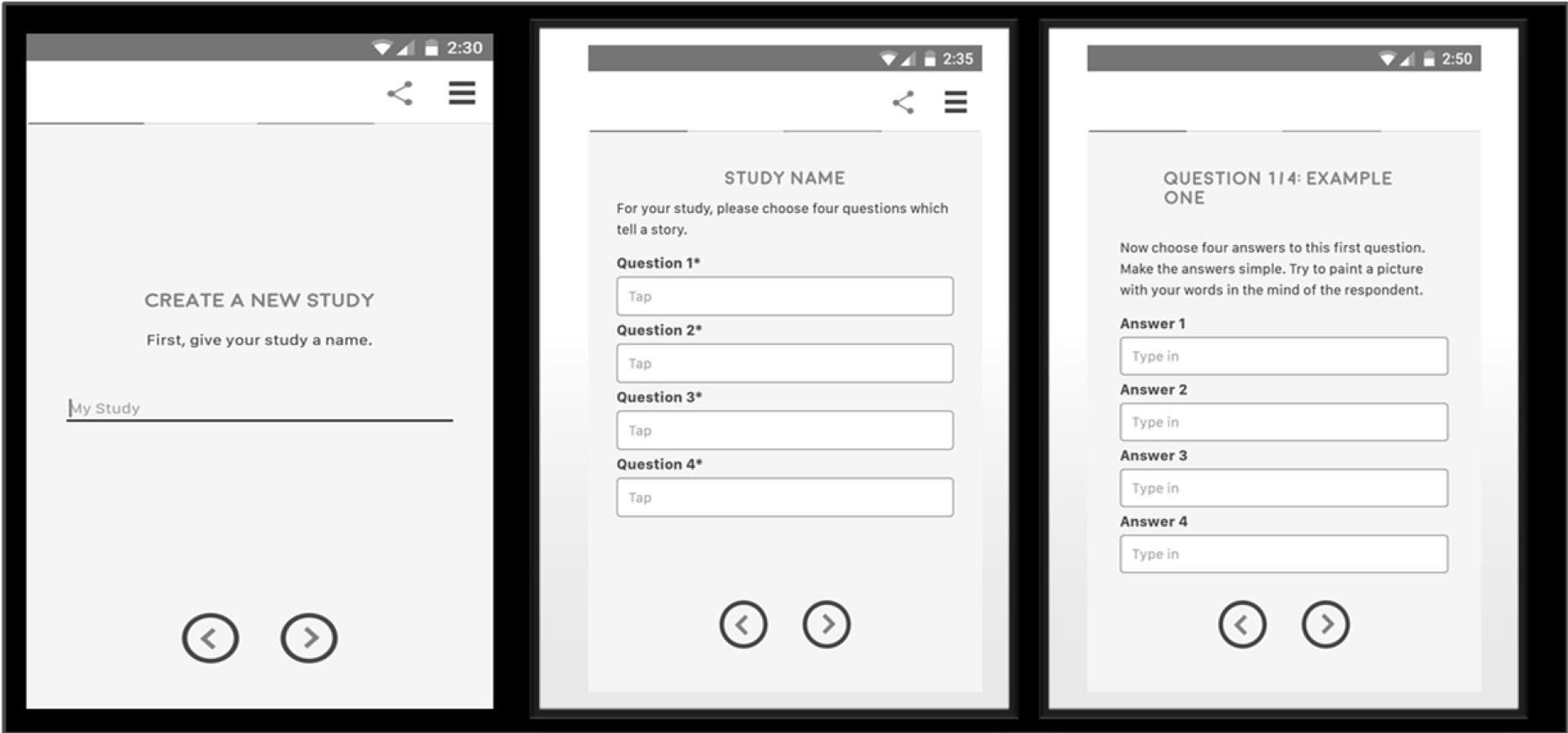

Figure 1 shows the three key screen shots.

Figure 1. The setup showing the three panels which force the student to think in an analytic yet creative and participatory fashion

The left panel shows the requirement that the student(s) select a name for the study. It may seem simple, but it will be the name of the study which drives much of the thinking.

The middle panel shows the requirement to create four questions dealing with the topic, with the questions ‘telling a story.’ It is here, at this second stage, beyond the name of the topic, where students encounter problems, and must ‘rewire’ their thinking. Students are taught to understand, to remember, to regurgitate. Students are not taught to ask a series of questions to elucidate a topic. Eventually, the students will learn how to ask these questions, but it will be much later, when the student is introduced to research in the upper grades, and when the student becomes a professional, especially a lawyer. We are creating the opportunity to bring that disciplined thinking to the junior high school or even to grade school.

The right panel shows the requirement to provide four answers to one of the questions. There is no hint, no guidance, about what the answers should be, but simply the question repeated to guide the student. Typically, this third panel is easy to complete once the student has gone through the pain of thinking through the four questions. That is, the questions are hard to formulate; the answers are easy to come by after the hard thinking has been done.

Engaging the student in the creation of questions and answers

The key to the approach is the set of questions, and secondarily the set of answers. As noted above, the demand on the participant is to conceptualize the topic at the start, rather than being trained to deconstruct the topic when it is fully presented. The approach thus is synthetic, requiring imagination on the part of the student.

Table 2 presents the four questions and the four answers to each question. The questions and the answers do not emerge simply from the mind of the student, at least not at first. There are the inevitable false steps, the recognition that that the questions do not make sense, do not tell a story, do not flow to create a sequence, etc. These false steps are not problems, but rather part of the back and forth learning how to reason, how to tell a coherent story, and how to discard false leads.

Table 2. The four questions, and the four answers to each question

|

Question 1 – Who initiated?

|

|

A1

|

Initiated by: Young neighbor (14 years old)

|

|

A2

|

Initiated by: Older neighbor (29 years old)

|

|

A3

|

Initiated by: School friend in high school

|

|

A4

|

Initiated by: Uncle of person

|

|

Question 2 – What was the action

|

|

B1

|

Action: To borrow item for use in project

|

|

B2

|

Action: To use item as part of a charity event

|

|

B3

|

Action: To guard item while the owner went away

|

|

B4

|

Action: To try to sell the item at a garage sale

|

|

Question 3 – How or where was the request made?

|

|

C1

|

Request made: On telephone

|

|

C2

|

Request made: In a group meeting

|

|

C3

|

Request made: In a house of worship

|

|

C4

|

Request made: At a dinner party

|

|

Question 4 – What eventually happened?

|

|

D1

|

What eventually happened: Item lost

|

|

D2

|

What eventually happened: It destroyed in accident

|

|

D3

|

What eventually happened: Item stolen on bus

|

|

D4

|

What eventually happened: Item given away by error

|

The answers in Table 2 are simple phrases, with the introduction to the answer being a phrase to reinforce the story. Various efforts at making the approach simply continue to reveal that for those who are beginning a topic, it is helpful to consider the answers as continuations of the questions. That specification, such as ‘initiated by’ will also make the respondent’s effort easier.

It is important to keep in mind that the process of topic/question/answer will become smoother with practice, the topics will become more interesting, the questions will move beyond simple recitation of the order of events, and the answers will become more like a literary sentence, and less like a menu item.

In the various experiences with this system, it is at this point, the four questions, that most people have difficulties. Indeed, even with practice, people find it hard to organize their thinking to bring a problem into sufficiently clear focus that they can make it into a story. When the researcher finally ‘understands the task’ the response is often a statement about ow they feel their ‘brains have been rewired.’ Never before did the researcher have to think in such a structured, analytic way, yet with no guidance about ‘what is right.’

One of the more frequent questions asked at this point is ‘Did I do this right?’ Most people are unaccustomed to structured thinking. After creating the questions, and on the second or third effort, after the first experiment, the researcher begins to feel more comfortable, and is able to move around the order of questions, changing them to make more sense. This flexibility occurs only after the researcher feels comfortable with the process.

Creating ‘meaningful’ stimuli by means of an underlying experimental design

As students, we are typically taught the ‘scientific method,’ namely to isolate a variable, and understand it. Our mind is attuned to dissecting a situation, focusing on one aspect. We lose sight of the fact that the real world comprises mixtures, and that an understanding of the real world requires us to deal with the way mixtures behave. An observation of our daily actions quickly reveals that virtually all of the situations in which we mind ourselves comprises many variables, acting simultaneously. Indeed, much of the problem of learners is their experienced difficulties in organizing the multi-modal stimuli impinging on themand learning to focus and to prioritize. It is to this skill we now turn as we look at the student experience.

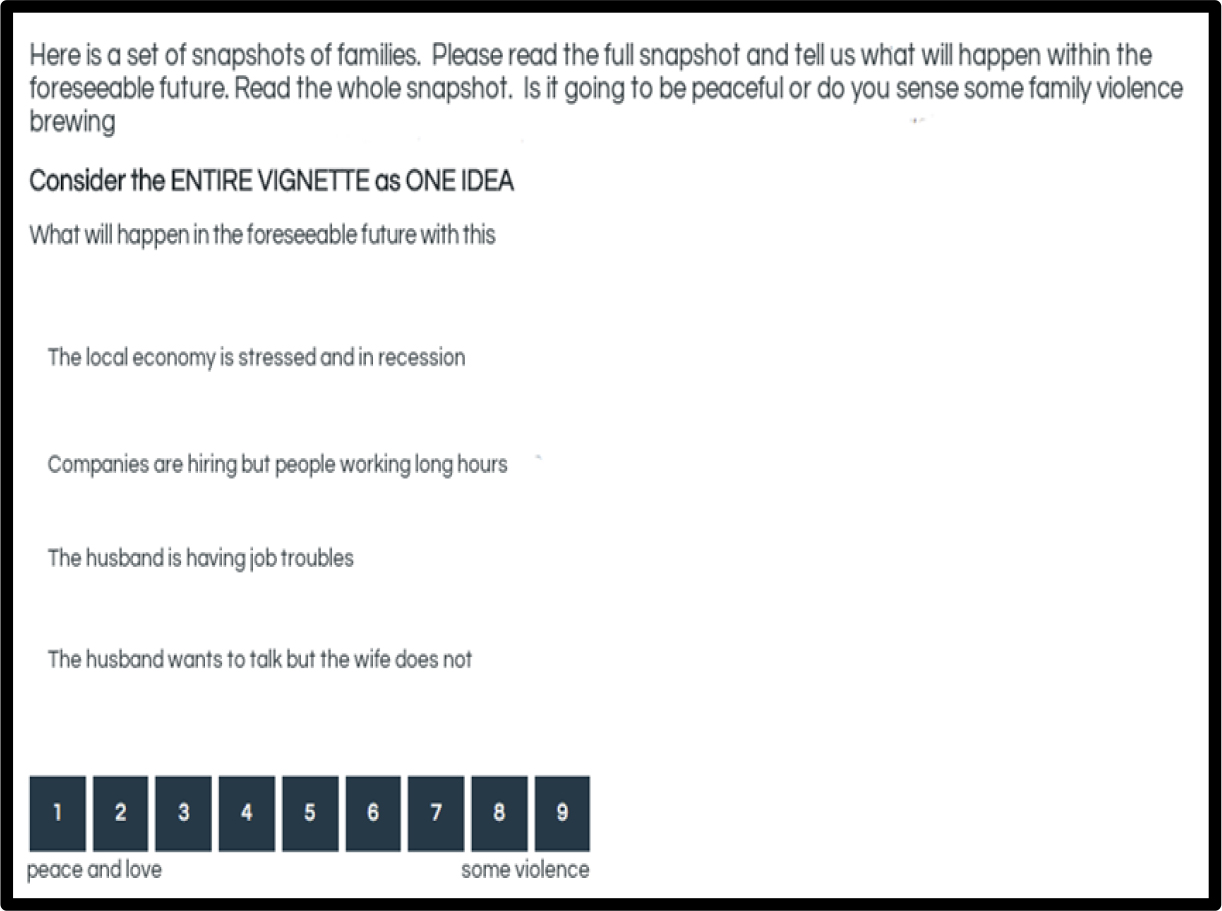

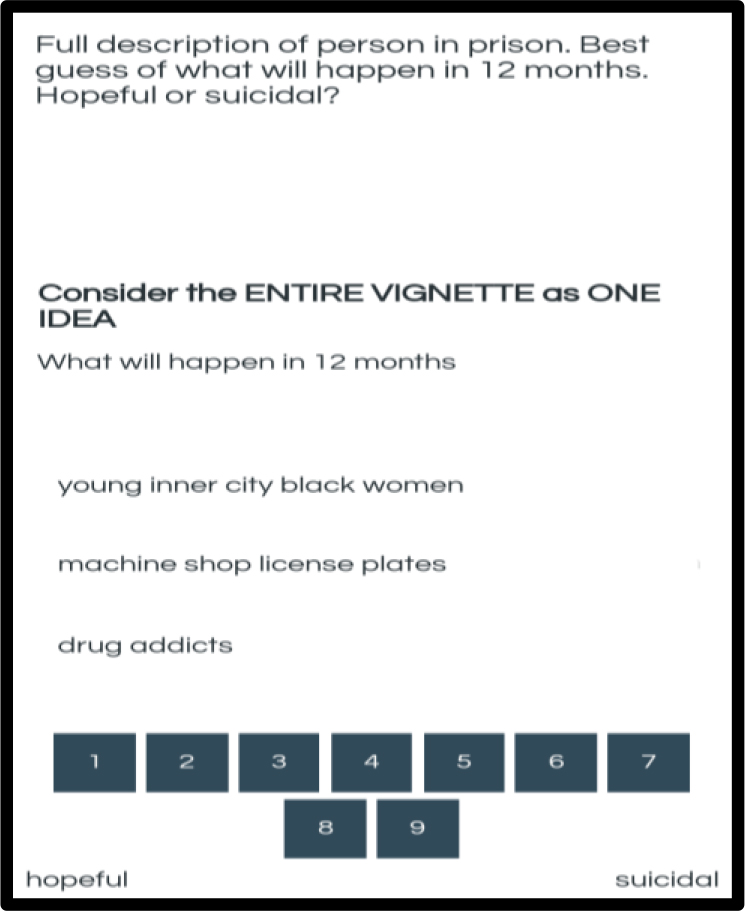

The computer program combines alternative answers to these four questions, creating short vignettes, presents them to respondents, gets a rating of ‘must repay’ vs ‘does not need to repay’.’

The above-mentioned approach seems, at first glance, to be dry, almost overly academic. Yet, the Mind Genomics approach makes the ‘case’ into something that the students themselves can create, investigated, and report, with a PowerPoint® presentation of the study, something that will be part of their portfolio for life, and can be replicated on many different topics.

Each respondent evaluates a unique set of vignettes, created by a systematic permutation of the combinations. The mathematical rigor of the underlying experimental design is maintained, but the different combinations ensure that across all the respondents a wide number of potential combinations are evaluated.

The underlying experimental design and indeed all of the mathematics for the analysis are shielded from the respondent, who is forced to ‘think’ about the topic, and the meaning of the data, rather than getting lost in deep statistics.

The composition of the vignettes is strictly determined by an underlying specification known as an experimental design [7]. Each vignette comprises either two, or three or four answers, at most one answer from a question, but sometimes no answer from a question. The experimental design ensures that the 16 elements appear as statistically ‘independent of each other,’ so knowing that one answer appears in a vignette does not automatically tell us whether another answer will appear or not appear.

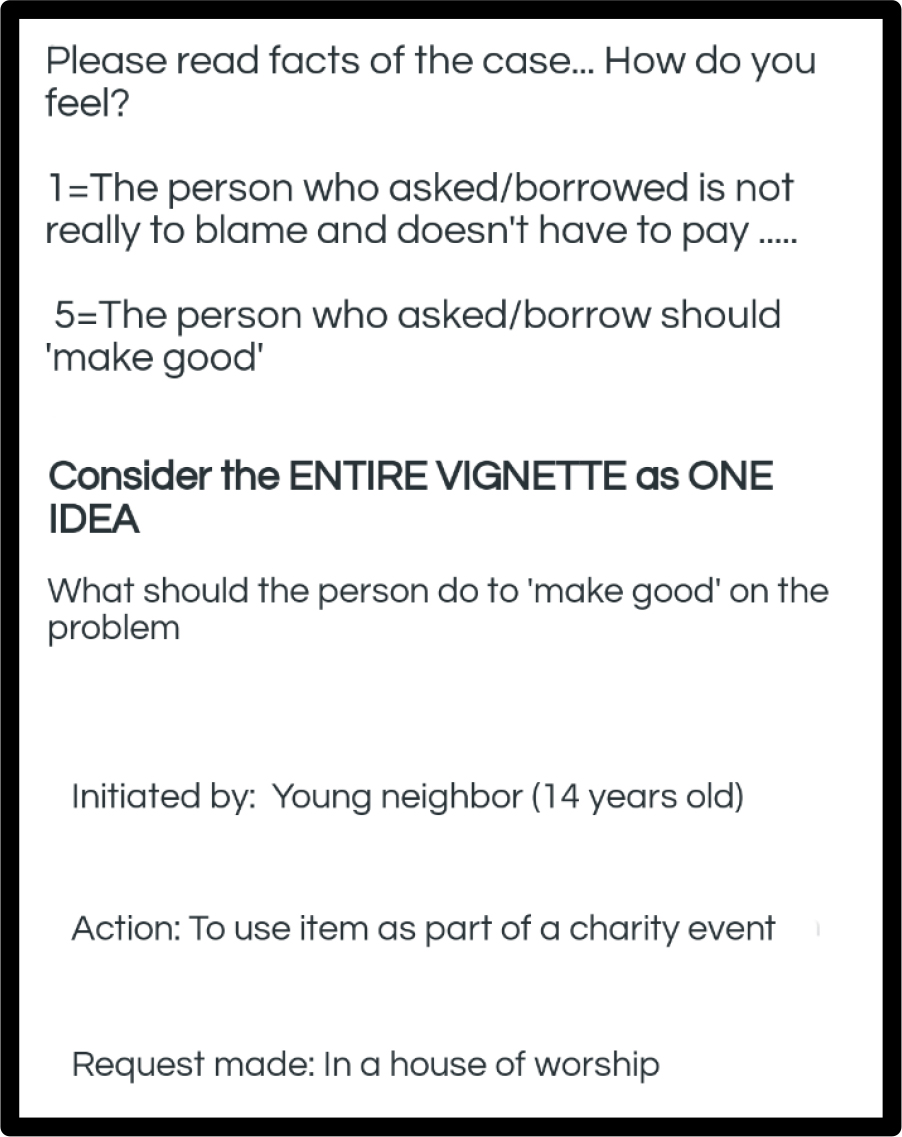

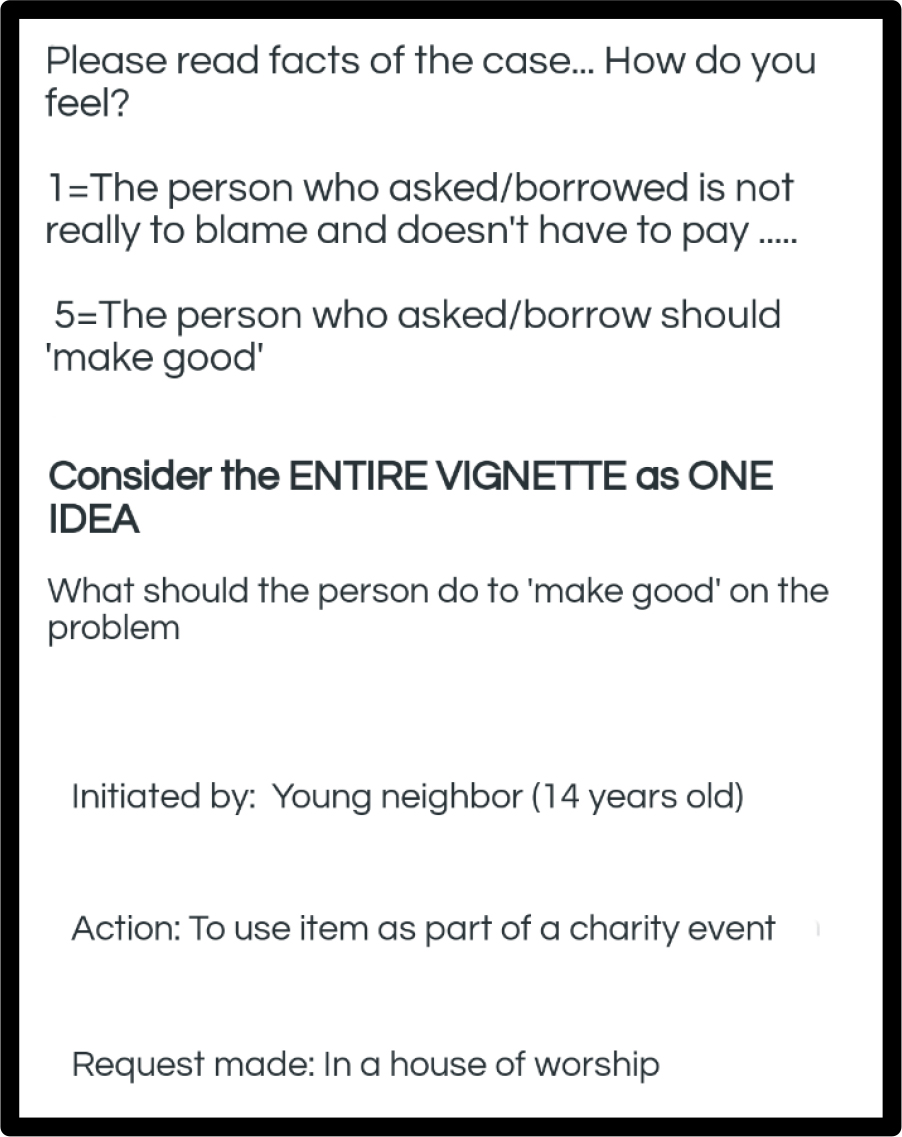

Figure 2 shows an example of a vignette created according to the underlying design. The respondent does not know that the computer has systematically varied the combinations.The vignette is created by an underlying experimental design which prescribes the composition of each vignette. Each respondent evaluates 24 different vignettes, or combinations of answers, and answers only. No questions leading to the answers are presented directly, although for this case the question is embodied at the beginning of the answer.

Figure 2. Example of a vignette comprising three answers or elements, one answer from three of the four questions. Most vignettes comprise four answers, some comprise three answers, and a few comprise two answers.

An important challenge in Mind Genomics is to come up with a meaningful rating question. The rating question links the test stimuli, our vignettes, and the mind of the respondent. Without a meaningful test question all we have are a set of combinations of messages. The test question focuses the respondent’s mind on how to interpret the information in the vignette.

The test question is posed simply as either a unipolar scale (none vs a lot) or a bipolar scale (strong on one dimension vs strong on the opposite dimension, such as hate/love). To the degree that the researcher can make the rating question meaningful, the researcher will have added to the power of the Mind Genomics exercise.

Our topic here concerns the loss of property occasioned by one person giving property to another person, after being asked to do so, or after being motivated to do so, that motivation coming from within. A reasonable rating question is whether the person in whom the property is placed, for whatever reason, is required to ‘make good byreplacing the property’ or ‘not required to replace the property.’ Rather than requiring a yes/no answer, we allow the respondent to assign a graded value, using a Likert Scale:

1 = The person who asked/borrow is not really to blame and doesn’t

have to pay ….

5 = The person who asked/borrowed should ‘make good.’

The phrasing of the question and the simple 5-point rating scale make the evaluation easy, and remove the stress from the respondent. By allowing the student a chance to assign a graded rating, the student can begin to understand gradations of guilt and innocence. Furthermore, the answers are not so clear cut, so straightforward that they prevent the student from thinking. The requirement to take the facts of the case into account and rate the feeling of guilt vs innocence on a graded scale forces the student to think. The very ‘ordinariness’ of the case encourages the student to become engaged, since the case is something that no doubt the student has either experienced personally, or at least has heard about at one or another time.

Obtaining additional information from the respondent

Quite often, those who teach do not pay much attention to WHO the respondent actually is, or even the different ways that people think. The academies where the Talmud was created did pay attention to the way people think, coming up with different opinion about the same topic. These different opinions were enshrined in discussions. The intellectual growth coming from thinking about the problem was maintained over the millennium and a half through the discussions of students about different points of a topic, and the study of those who commented on the law, and gave legal opinions about cases. The back and forth discussions about why the same ‘facts on the ground’ would lead to different opinions became a wonderful intellectual springboard for better thinking. Few people, however, went beyond that to think, in a structured way about how ordinary people might think of the problem, people who were not trained as legal scholars, nor empaneled in a judicial panel.

Part of the effort of the Mind Genomics project is to show to the student the way different people think about the topic, and how there is not necessarily ‘one right answer.’ Thus, at the start of the experiment, before the evaluation of the 24 vignettes by the respondent, the respondent is asked three questions:

- Year of birth, to establish age

- Gender

- A third question, chosen by the researcher. Here is the third question for this study.

How do you feel about mistakes that are made in everyday life, by ‘accident’

1=I believe that the law is the law 2=I believe in being lenient 3=I want to know the facts of the case more

Running the study for educational purpose – Mechanics

During the past several decades, and as the Mind Genomics technology evolved and was refined, a key stumbling point, i.e., a ‘friction point’ in today’s language, continued to emerge. This was the deployment of the study in a way that could be quick, inexpensive, and thus have an effect within a short time. Two decades ago as the Internet was being developed, a great deal of the effort of a Mind Genomics study was expended getting the respondents to participate, typically by having them come into a central location, such as a shopping mall, and spending ten or 15 minutes. The result was slow, and the pace was such that it would not serve the purposes of education. The process was slow, tedious, expensive, and not at all exciting to anyone but a serious researcher.

During the formative years of the technology, 2010–2015, efforts were put against making the system fast, with very fast feedback. The upshot was that a study could be set up in 30 minutes or faster and deployed on the internet with simply a credit card to pay for the cost of respondents, usually about 3.00$ per respondent for what turned out to be a 4 minute study. A field service, specializing in on-line ‘recruiting’ would provide the appropriate respondents, sending them to the link, and obtaining their completed, and motivated answers. The respondent motivation was there because they were part of the panel.

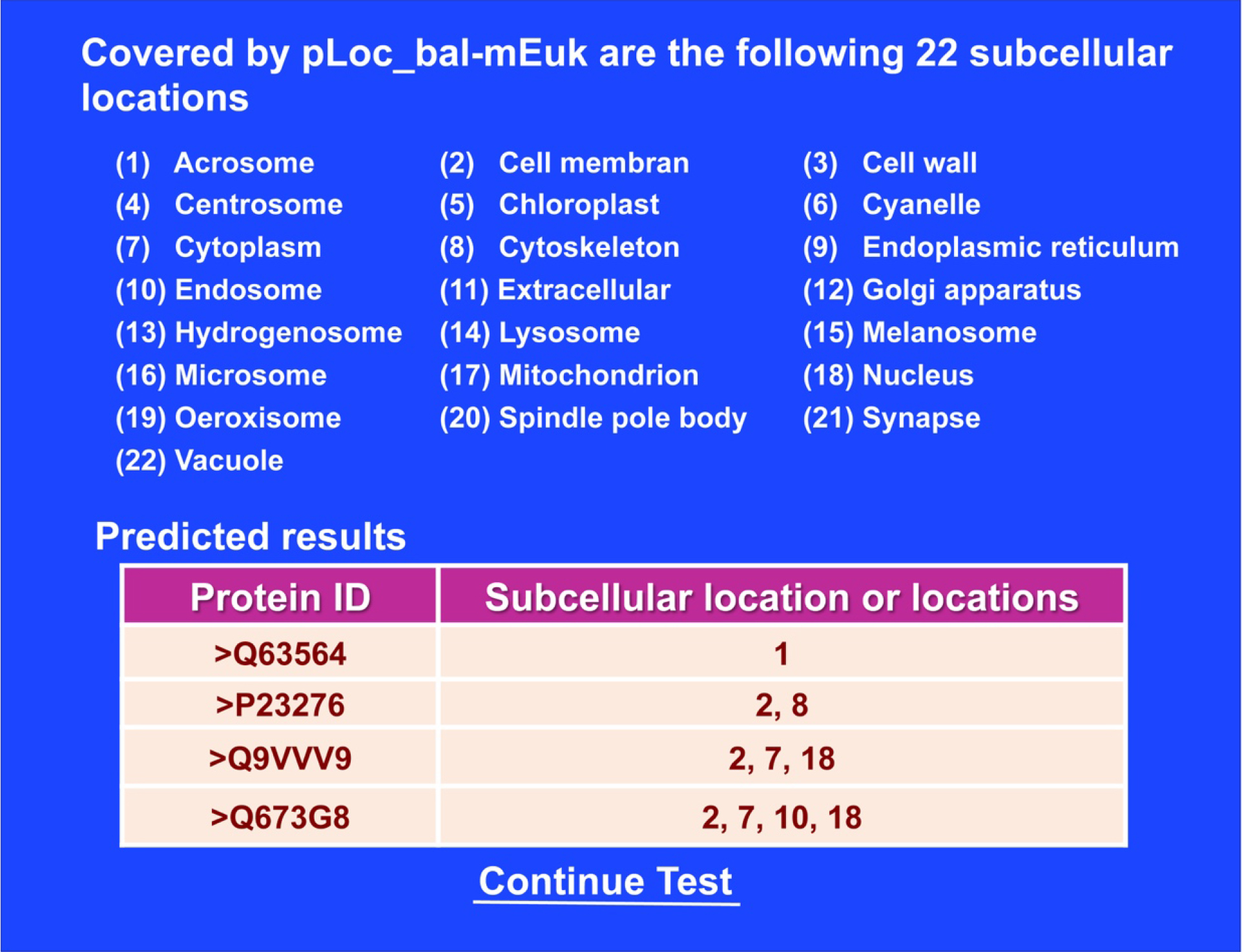

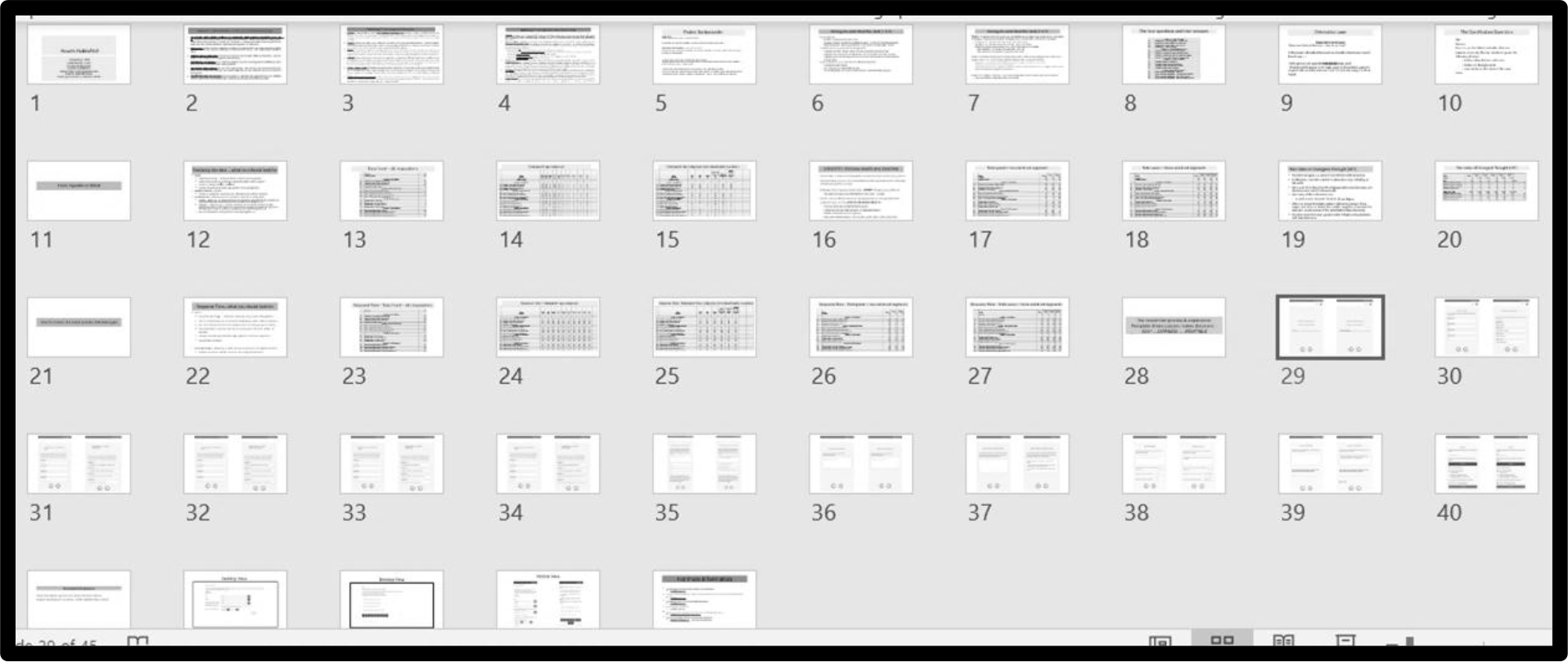

The mechanics were such that the entire study in the field would come back in less than one hour and one minute. The total analysis, including the preparation of the report in PowerPoint(r), ready for the student presentation, took less than one minute from the end of the field. Figure 3 shows an example of the PowerPoint(r), expanded to the slide sort format, showing the systematic presentation of the results.

Figure 3. Example of the PowerPoint® report for the study, shown inlide-sort format. The respondent receives the PowerPoint® report and the accompany Excel® data sheet one minute after the end of the data acquisition.The report is in color, and ‘editable.’

- The title page, showing the study name, the researcher, the date

- Information about the BimiLeap vision

- The raw material – elements, rating question

- How the data are analyzed, showing the transformation from a rating scale to a binary rating, as well as introducing the concept of ‘regression modeling’ …. This explanatory information is presented in a short, simplistic manner, yet sufficient to show the nature of mathematical (STEM) thinking

- Tables of data showing the results from the total panel, key subgroups

- Mind Sets – a short introduction to how people can think differently about the topic, and a short introduction to the calculations. Once again, the focus is on the findings, not on the method

- Results from dividing the respondents into two mind-sets and three mind-sets

- IDT – Index of Divergent Thought – showing how many elements have strong positive coefficients, when the data are considered in terms of total panel, two mind-sets and three mind-sets, respectively. The IDT can be used to understand how well the researcher has ‘dived in’ to the topic, to uncover different ways of thinking about the topic. The IDT can be used to ‘gamify’ the research process, by providing an operationally defined, objective measure, of ‘winning ideas.’

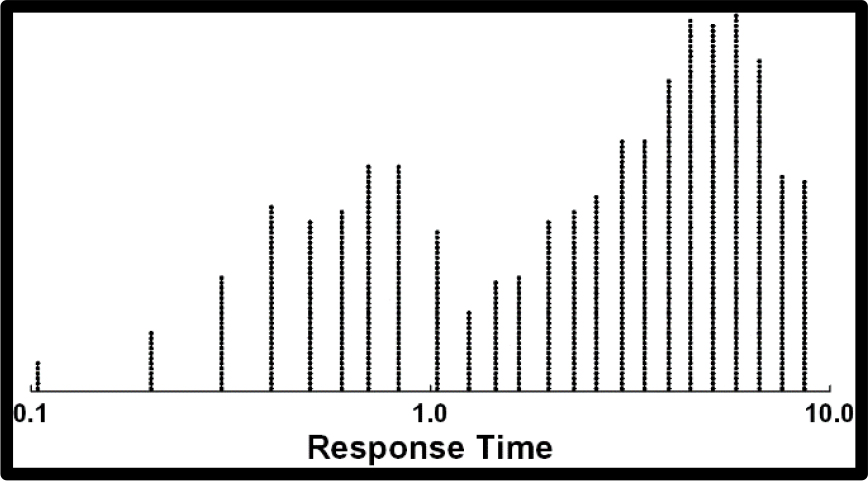

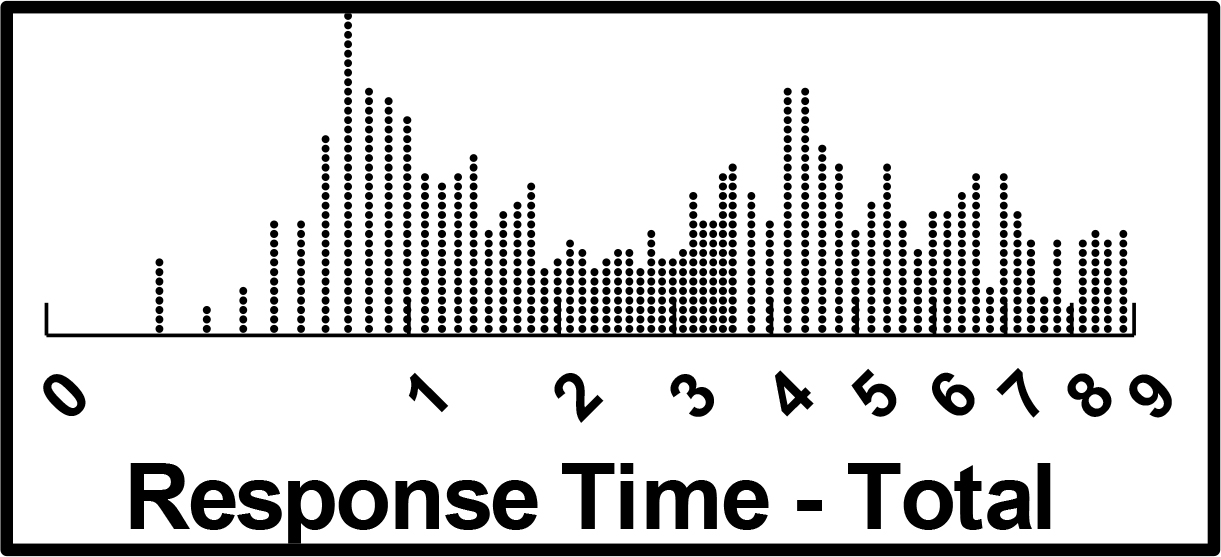

- Introduction to ‘response time’ – how long it takes the respondent to ‘process’ the ideas

- Tables of data showing the results from the total panel, key subgroups, and mind-sets

- Screen shots of the respondent experience

The report is accompanied by an Excel book with the data, set up for further analysis, if the student wishes.

The results, embedded in a pre-formatted PowerPoint® presentation, and with supporting full data in Excel®, are immediately dispatched by email and can always be retrieved from the researcher’s account, when, for example, the data are ‘updated’ with the ratings assigned by new panel participants. This process compresses the entire time, from set-up to data reporting, so that the results can be discussed within 1–3 hours after the official start the entire process, viz., entering the questions and answers into the BimiLeap programming and getting the panel provider to provide respondents.

The vision behind the PowerPoint® report is that it provides a tangible record of the student’s effort, a measure of what the student has achieved in the growth to learning. By creating different groups of students who work together, and working together for 90 minutes in the afternoon, once per week, the typical student can generate 20–30 or so PowerPoint® in a year, a collection the quality of whose contents, study by study, will demonstrably improve as each study is designed, and executed with real people, the respondents.

What the student receives and how the student learns

Table 3 presents the unadorned results, a table. To interpret the table is straightforward, despite the fact that it has simply numbers. The researcher who is doing the study need not know the mechanics of how the numbers are computed, at least not in the beginning, in order to enjoy the benefits of Mind Genomics, and in order to participate in experiential learning.

Table 3. Output from a Mind Genomics on a simple legal case. The data is from the total panel

|

|

Found responsible and must make good

|

Total

|

|

|

Base Size

|

30

|

|

|

Additive Constant (Estimated percent of the times the initiator must repay in the absence of any information)

|

60

|

|

|

Question A: Who initiated

|

|

|

A2

|

Initiated by: Older neighbor (29 years old)

|

0

|

|

A4

|

Initiated by: Uncle of person

|

-8

|

|

A1

|

Initiated by: Young neighbor (14 years old)

|

-10

|

|

A3

|

Initiated by: School friend in high school

|

-10

|

|

|

Question B: What was the action

|

|

|

B2

|

Action: To use item as part of a charity event

|

5

|

|

B4

|

Action: To try to sell the item at a garage sale

|

-5

|

|

B1

|

Action: To borrow item for use in project

|

-6

|

|

B3

|

Action: To guard item while the owner went away

|

-11

|

|

|

Question C: Where was the request made

|

|

|

C1

|

Request made: On telephone

|

4

|

|

C2

|

Request made: In a group meeting

|

3

|

|

C3

|

Request made: In a house of worship

|

2

|

|

C4

|

Request made: At a dinner party

|

-2

|

|

|

Question D: What happened

|

|

|

D2

|

What eventually happened: It was destroyed in accident

|

6

|

|

D3

|

What eventually happened: Item stolen on bus

|

-8

|

|

D1

|

What eventually happened: Item lost

|

-10

|

|

D4

|

What eventually happened: Item given away by error

|

-10

|

The question what is the initiator (Question A) required to do. At the low end, the initiator does not have to ‘make good’ (innocent, i.e., not pay.) At the top end, the initiator has ‘make’ good (guilty, i.e., pay.)

Base Size: The table shows us that there are 30 different people who participated in the study. This is the base size.

Additive Constant: This is the expected number of times out of 100 people that the verdict will be ‘guilty’, i.e., must repay. What is special is that the additive constant is a baseline, corresponding to the likelihood that a person will say ‘guilty’ even in the absence of information. Our additive constant is 60. It means that when someone requests from another to do something with the item, 3 out of 5 (60%) the onus is on the person who does the requesting to take responsibility and pay if something happens to the item.

Coefficient: Ability of Each Element to drive Guilty (must repay). Let’s look at the power of Question A: Who initiated. The four answers or alternatives, which appeared in the vignette, are either 0 (nothing) or negative. The negative means that when we know who initiated, we are likely to forgive. We forgive most when the action is initiated by a young neighbor or, or school friend in high school. The value is -10. That value -10 means the likelihood of guilty (must make good) goes from 60 (no information about the initiator) to 50, when the one piece of information about the initiator is presented as part of the case (specifically, initiated by: School friend in high school.) Of course, when the initiator is an older neighbor (29 years old), the coefficient is no longer -10 as it was before, but now 0. We (and of the course the student) have just discovered that it makes a difference WHO the initiator is.

The same thinking can be done for the other questions and answers. Some, like D2 (What eventually happened: It was destroyed in accident) increase the likelihood of being judged responsible, and forced to make good, i.e., to repay.

The process from the vantage point of the researcher (e.g., the student)

As presented above, the process is simple, although quite uninteresting, except perhaps to the subject matter expert interested in lawor in thinking processes. How can the student be engaged to participate? Otherwise, what we have here is simply another ‘dry process’ with some interesting but unexciting results.

The three aspects of the process are involvement, ease, and fast/clear results. Absent those, and the process will remain in the domain of the expert, to be used occasionally when relevant, and otherwise to be relegated to process. The excitement of thinking and learning will not be experienced.

Let us proceed with the process. The process follows a series of steps designed to make the researcher think. The process is structured, not particular hard after the first few experienced, but sufficiently challenging at the start so that the researcher realizes the intellectual growth which is taking place at the time of the research set up.

Experimental Designs – mixtures of answers

The actual test stimuli comprise mixtures of answer, without the questions. One can go to Table 2, and randomly pick out one answer from each of the four questions, present these answers together, on separate lines, and instruct the respondent to read the vignette, the combination, and rate the combination as a single entity. The task may seem ‘strange’ to those who are accustomed to reading properly constructed paragraphs in their native language, but to those who are selected from random individuals to be study participants, there is no problem whatsoever. People follow instructions. The problem with evaluating a few unconnected combinations is that there are no explicit patterns waiting to be discovery, and a discovery in turn which can teach systematic and critical thinking.

As noted above several times, the Mind Genomics paradigms works with an explicitly developed experimental design, which makes it easy for the equipped research to discover the pattern. Table 4 shows an example of the experimental design for a single respondent. There is a total of 16 answers and 24 vignettes, or combinations. The number and arrangement of the vignettes are not accidental, nor haphazard, and certainly not random, although it is tempting to say that the combinations are randomly arranged. Nothing could be further from the truth. The design, i.e., the combinations are precisely defined ahead of time , so that each of the 16 elements or answers appears exactly five time, that any vignette of combination has at most four answers (without their questions), that some combinations comprises two, others comprise three answers, and that the answers are systematically varied. Finally, each of the experimental design is mathematically identical to every other design, but the specific combinations are different.

Table 4. The experimental design for 7 of the 24 vignettes for a respondent, as well as the rating, the binary expansion of the rating, and the consideration time

|

Order

|

A1

|

A2

|

A3

|

A4

|

B1

|

B2

|

B3

|

B4

|

C1

|

C2

|

C3

|

C4

|

D1

|

D2

|

D3

|

D4

|

Rating

|

Top2

|

|

7

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

4

|

100

|

|

8

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

|

9

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

3

|

0

|

|

10

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

5

|

100

|

|

11

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

3

|

0

|

|

12

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

3

|

0

|

|

13

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

3

|

0

|

Different points of view for the same argument – Mind-Sets and exciting discoveries

Students who ask questions to engage discussion are generally appreciated by their teachers. The questions show involvement. Sometimes the questions spark lively discussions, especially when they are offered in the spirit of ‘looking at the problem in different ways.’

A foundation stone of Mind Genomics is the recognition and elicitation of different points of view about the same topic. The ingoing rationale is that in matters of everyday life there are facts, but often radically different opinions. Sometimes more learning emerges from the discussion of the topic from these different viewpoints than could ever emerge from rote learning of the ‘facts.’

One of the computations of Mind Genomics is the discovery of different mind-sets, groups of people with these individuals in one group looking at the topic differently from individuals in another group. The computational machinery of Mind Genomics enables these mind-sets to be discovered rapidly and inserted into the PowerPoint® report as simply new groups to consider and to discuss.

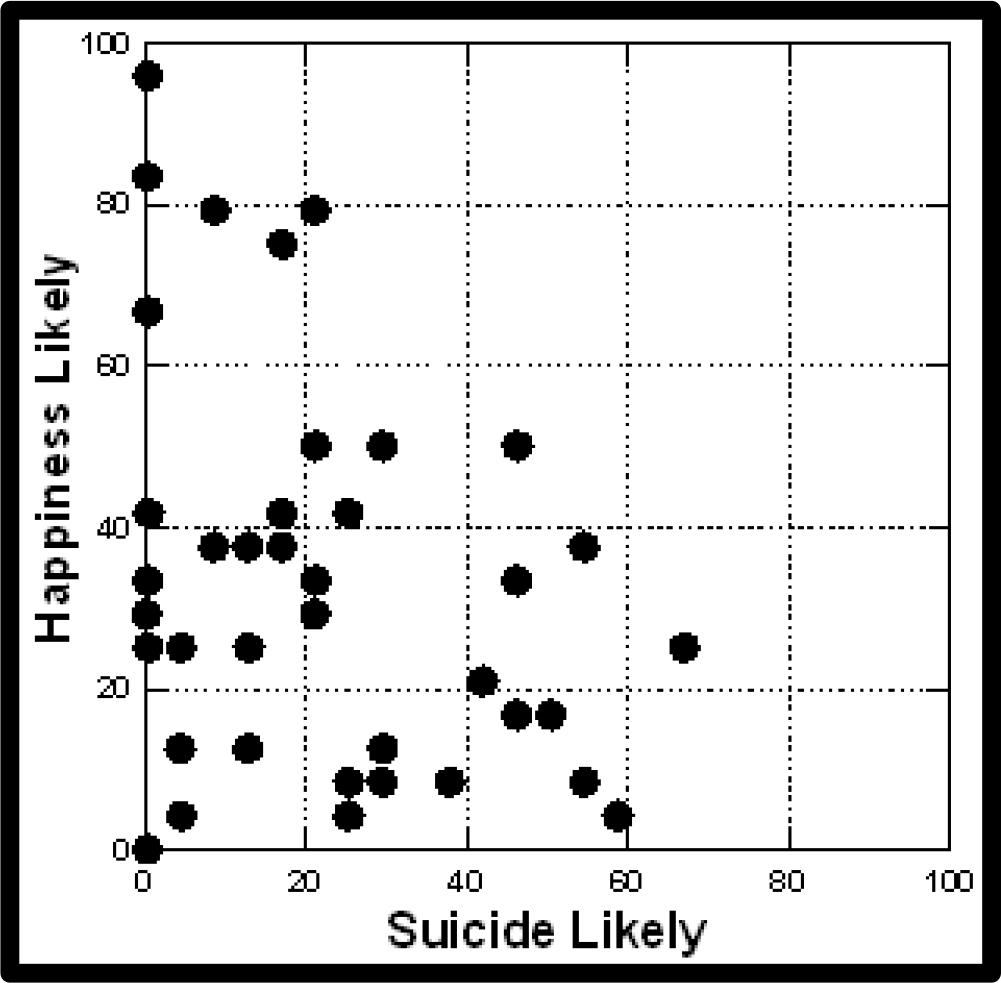

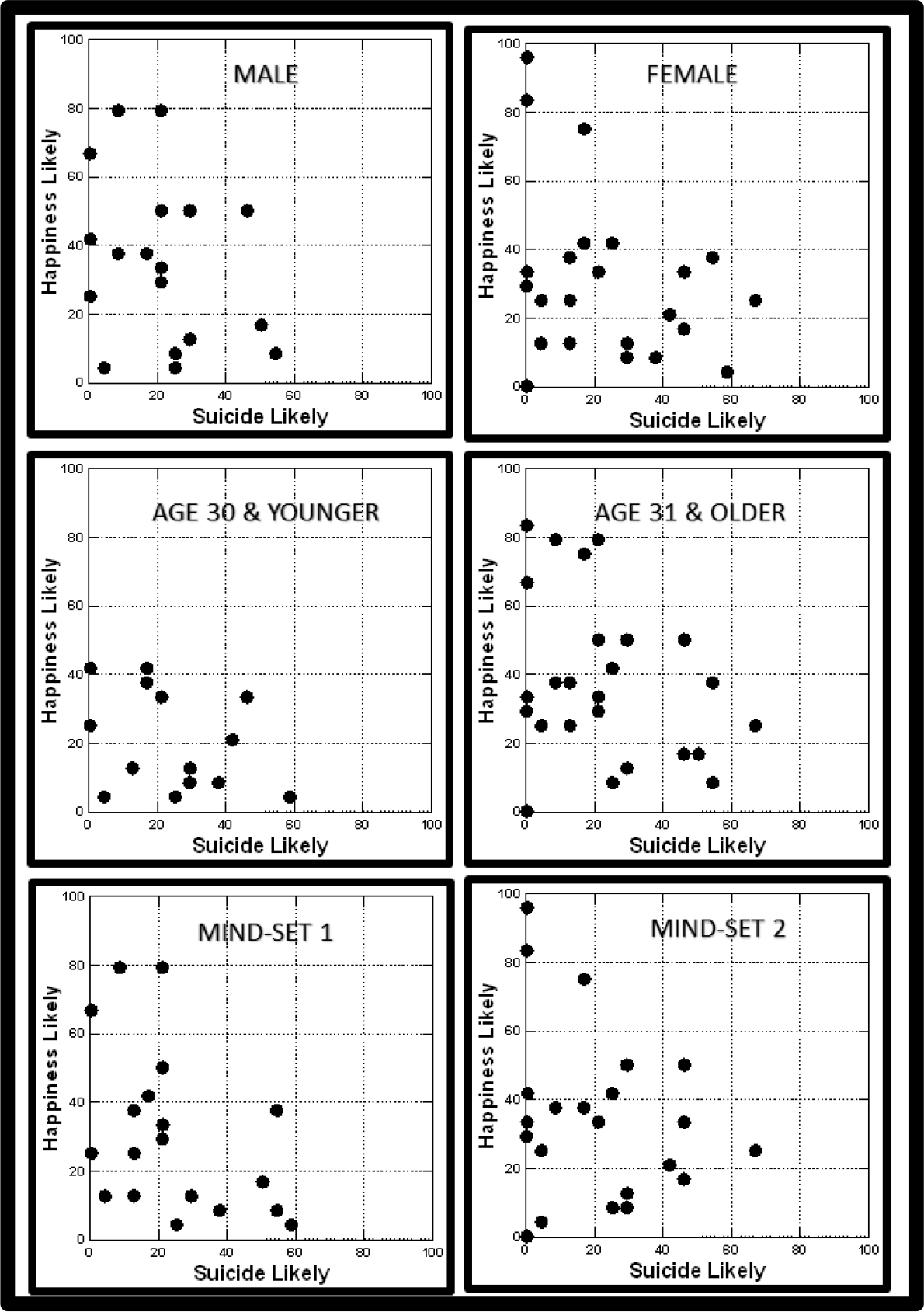

Table 5 shows the additive constant and coefficients for total (already discussed), gender, age, and two mind-sets. The students who participate in the study, indeed those who may have come up with the elements, can now see how the simplest of facts can be interpreted in different ways.

Table 5. The pattern of coefficients for ‘make good’, generated by key demographic groups (total, gender, age) and newly uncovered mind-sets.

|

|

|

|

Gender

|

Age

|

Mind-Set

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rating 4–5 transformed to 100;

Ratings 1–3 transformed to 0

Focus on ‘make good’ (guilty)

|

Tot

|

Male

|

Female

|

A16–19

|

A20–23

|

MS1

|

MS2

|

|

|

Additive constant (percent of times a rating will be 4–5 in the absence of any elements (i.e., a baseline)

|

51

|

53

|

66

|

40

|

63

|

56

|

48

|

|

|

Elements driving ‘guilty’ – Mind-Set 1

(Focus on action)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

B2

|

Action: To use item as part of a charity event

|

10

|

-15

|

10

|

17

|

1

|

20

|

-5

|

|

B1

|

Action: To borrow item for use in project

|

5

|

-13

|

5

|

11

|

-4

|

16

|

-15

|

|

C1

|

Request made: On telephone

|

-2

|

0

|

-6

|

1

|

-6

|

11

|

-18

|

|

B4

|

Action: To try to sell the item at a garage sale

|

0

|

-25

|

-11

|

14

|

-16

|

10

|

-17

|

|

C4

|

Request made: At a dinner party

|

-3

|

-12

|

-6

|

-5

|

-2

|

8

|

-18

|

|

|

Elements driving ‘guilty’ – Mind-Set 2

(Focus on what happened, and who, specifically, initiated)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

D2

|

What eventually happened: It destroyed in accident

|

1

|

-6

|

-7

|

1

|

3

|

-6

|

14

|

|

D1

|

What eventually happened: Item lost

|

-4

|

-4

|

-9

|

-10

|

0

|

-14

|

14

|

|

D4

|

What eventually happened: Item given away by error

|

-5

|

-10

|

-10

|

-9

|

0

|

-17

|

13

|

|

A1

|

Initiated by: Young neighbor (14 years old)

|

-1

|

-2

|

-6

|

-5

|

2

|

-12

|

10

|

|

A2

|

Initiated by: Older neighbor (29 years old)

|

0

|

-3

|

5

|

1

|

1

|

-10

|

9

|

|

A4

|

Initiated by: Uncle of person

|

-4

|

-4

|

-7

|

0

|

-5

|

-14

|

8

|

|

|

Elements not driving guilty for any key group

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

D3

|

What eventually happened: Item stolen on bus

|

-5

|

-6

|

-10

|

-10

|

-2

|

-13

|

7

|

|

A3

|

Initiated by: School friend in high school

|

-5

|

0

|

-8

|

-3

|

-6

|

-14

|

6

|

|

C3

|

Request made: In a house of worship

|

-2

|

-9

|

-8

|

1

|

-4

|

1

|

-6

|

|

C2

|

Request made: In a group meeting

|

-1

|

6

|

-1

|

-6

|

4

|

4

|

-9

|

|

B3

|

Action: To guard item while the owner went away

|

-5

|

-4

|

-5

|

3

|

-13

|

4

|

-22

|

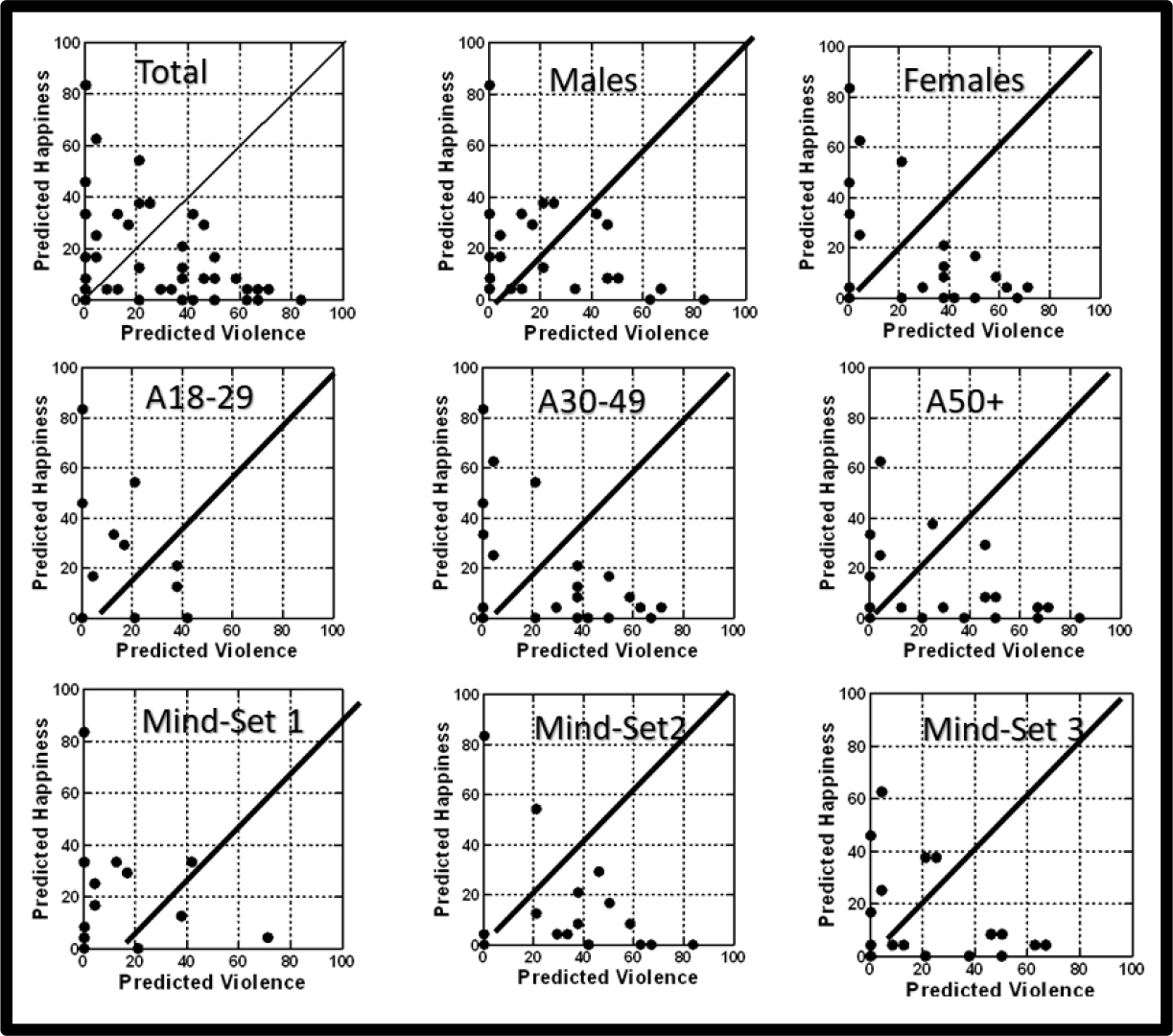

What should emerge from Table 5 is the charge to the students to ‘tell a story about the mind of each group,’ about whether the mind of the group seems to hold strong views or weak views about what makes a person guilty. There is no right nor wrong answer, but simply the requirement that the student abstract from these data some narrative of how the group thinks. The difference in coefficient is most dramatic for the two mind-sets, but what is the MEANING of the difference? In that short question lies a great deal of opportunity for the students to think creatively, to see patterns, and indeed perhaps even to make new-to-the-world discoveries. Furthermore, the excitement can be maintained by challenges to the students to create personas of the mind-sets, and to suggest and executed follow-up experiments with Mind Genomics to explore hypotheses about these mind-sets.

Learning to think even more deeply – Is justice blind, and how can the student prove or disprove it?

We finish off the data section by a new way of thinking, and two exercises can be done manually with available statistical programs, planned to be programmed into the next generation of the Mind Genomics report. These are called ‘scenario analyses.’ The logic behind them is simple. The thinking emerging from them is far from simplistic, however. The struggle to understand the new patterns from this level of analysis helps to move the motivated student into a more profound way of thinking, in a subtle, easy, virtually painless way.

When people look at the ‘facts of the case’ they are often cautioned not to pay attention to the nature of the individuals, but simply the ‘facts on the ground,’ on what happened. Such caution is easy to givebut may or may not be followed. One of the opportunities afforded to the student of Mind Genomics is to understand clearly the interaction between WHO the person IS in the case, and the response. For example, in our case we have four people who initiate the request, ranging from a young neighbor, an old neighbor, the uncle, school friend in high school.

We can learn a lot by sorting the data into five different strata, depending upon who does the requesting, and ten building the model. We don’t know what exactly happened to the item, but we do know who did the requesting. We build the model based upon the five strata. Each stratum corresponds to one person who requested. The independent variables are the three other aspects (action: where request was made; what happened.).

The original set up of the Mind Genomics process was to create four questions, and for each question develop four answers. As described above, the underlying experimental design mixed and matched the combinations according to a plan. Each respondent, i.e., test participant, evaluated 24 different vignettes. Furthermore, unknown to the respondents, an underlying system created different sets of 24 vignettes, a unique set of combinations for each respondent.

It makes no difference to the respondent about the way the combinations are created. Whether the same 24 combinations are tested by 30 different people (the ordinary way), or whether the systemic variation produces 720 different combinations (24 different combinations x 30 different people), is irrelevant to the individual respondent. What happens, however, to the judgments when we look at five different groups of vignettes, varying, say, by WHO DOES THE INITIATION. We have vignettes with no mention of who does the initiation, as well as vignettes specifying the initiation by the younger neighbor (14 years old), the older neighbor (29 years old), by a school friend in high school, and by the person uncle.

The question which emerges, one provoking a great of discussion, is whether justice is blind. That is, the intended actions can be the same, the place where the request was made can be the same, and the outcome can be the same. Presumably, it does not matter WHO initiates the request. Justice should be blind. Is it?

We can sort the data into five strata, five groups, with each group comprising one of the five alternatives of ‘initiated by.’ There are five groups or strata because on group has NO mentionof ‘Initiated by:’ The next step is to estimate the coefficients, this time using only the remaining 12 elements. A1-A4 are absent from the regression because the regression is done on a stratum-by-stratum basis, where the element ‘Initiated by:’ is held constant.

After this effort the excitement increases when the students realize how strongly the initiator ‘drives’ the rating of ‘make good’ (i.e., rating of 4–5 converted to 100.) Table 6 shows this analysis when the strata are based upon Question A (Who Initiated?). Table 7 shows the comparable analysis when the strata are based upon Question B (Action or Purpose). In both cases there is plenty of space for discovery and for an ah ha experience, as the student uncovers truly new findings, itself motivating, and struggles to explain what she or he has revealed to the world.

Table 6. Coefficients for the models relating presence/absence of elements to the binary transformed rating ‘make good’ (i.e., guilty). The table shows the contribution of each of the elements to ‘make good’ when the ‘Initiated by’ was constant.

|

|

Rating 4–5 transformed to 100;

Ratings 1–3 transformed to 0

Focus on ‘make good’ (guilty)

|

No mention of Initiated

|

Initiated by: Older neighbor (29 years old)

|

Initiated by: Young neighbor (14 years old)

|

Initiated by: Uncle of person

|

Initiated by: School friend in high school

|

|

|

|

A0

|

A2

|

A1

|

A4

|

A3

|

|

|

Additive constant (percent of times a rating will be 4–5 when the ‘initiated by’ is the text at the head of each column

|

74

|

66

|

41

|

39

|

34

|

|

B2

|

Action: To try to sell the item at a garage sale

|

23

|

8

|

20

|

-10

|

7

|

|

B3

|

Action: To guard item while the owner went away

|

17

|

9

|

-11

|

-24

|

-11

|

|

B1

|

Action: To borrow item for use in project

|

4

|

8

|

19

|

-12

|

14

|

|

D1

|

What eventually happened: Item lost

|

-1

|

-9

|

7

|

0

|

4

|

|

B4

|

Action: To use item as part of a charity event

|

-4

|

9

|

-3

|

-3

|

-2

|

|

D3

|

What eventually happened: Item stolen on bus

|

-5

|

-10

|

-5

|

-3

|

-5

|

|

D4

|

What eventually happened: Item given away by error

|

-9

|

-16

|

-13

|

2

|

17

|

|

D2

|

What eventually happened: It destroyed in accident

|

-14

|

-6

|

6

|

3

|

7

|

|

C4

|

Request made: At a dinner party

|

-22

|

-17

|

-6

|

19

|

7

|

|

C3

|

Request made: In a house of worship

|

-28

|

-17

|

0

|

10

|

2

|

|

C2

|

Request made: In a group meeting

|

-33

|

-29

|

-1

|

26

|

8

|

|

C1

|

Request made: On telephone

|

-39

|

-16

|

19

|

28

|

-8

|

Table 7. Coefficients for the models relating presence/absence of elements to the binary transformed rating ‘make good’ (i.e., guilty). The table shows the contribution of each of the elements to ‘make good’ when the ‘Action’ or purpose was constant.

|

|

Rating 4–5 transformed to 100;

Ratings 1–3 transformed to 0

Focus on ‘make good’ (guilty)

|

Action: Not mentioned

|

Action: To borrow item for use in project

|

Action: To try to sell the item at a garage sale

|

Action: To guard item while the owner went away

|

Action: To use item as part of a charity event

|

|

|

|

B0

|

B1

|

B4

|

B3

|

B2

|

|

|

Additive constant (percent of times a rating will be 4–5 when the ‘initiated by’ is the text at the head of each column

|

-11

|

32

|

41

|

68

|

80

|

|

C2

|

Request made: In a group meeting

|

46

|

1

|

-16

|

10

|

-24

|

|

C4

|

Request made: At a dinner party

|

41

|

7

|

-7

|

-3

|

-12

|

|

C3

|

Request made: In a house of worship

|

38

|

16

|

-19

|

-5

|

-15

|

|

C1

|

Request made: On telephone

|

37

|

7

|

15

|

-14

|

-19

|

|

A4

|

Initiated by: Uncle of person

|

24

|

0

|

19

|

-27

|

-22

|

|

A1

|

Initiated by: Young neighbor (14 years old)

|

9

|

17

|

0

|

-29

|

1

|

|

D3

|

What eventually happened: Item stolen on bus

|

7

|

-4

|

-1

|

-15

|

-3

|

|

A3

|

Initiated by: School friend in high school

|

7

|

14

|

-2

|

-23

|

-15

|

|

D2

|

What eventually happened: It destroyed in accident

|

6

|

12

|

5

|

-7

|

1

|

|

D1

|

What eventually happened: Item lost

|

5

|

7

|

5

|

-19

|

7

|

|

A2

|

Initiated by: Older neighbor (29 years old)

|

5

|

11

|

12

|

-3

|

-17

|

|

D4

|

What eventually happened: Item given away by error

|

2

|

-2

|

6

|

-7

|

-6

|

IDT – Index of Divergent Thinking: Making the Mind Genomics into a game

As of this writing (early 2020), the world of students is awash with games, with fun, with a shortened attention span, and with the competition of different forms of entertainment. How do we convert Mind Genomics to entertainment or at least to that over-used neologism ‘edu-tainment?’

The notion of converting critical thinking to ‘games’ requires that there be criteria on which people can complete, and that these criteria be objective, rather than subjective. That is, to make Mind Genomics into a ‘game’ with points means to create an easy-to-understand scoring system, and specifically a system within which everyone can compete. Furthermore, in the spirit of critical thinking and experiential learning, the system should reward creative thought.

During the past three years author H Moskowitz has worked on criteria to ‘measure’ critical and creative thought within the framework of Mind Genomics. A key aspect of Mind Genomics is that it automatically estimates the degree of linkage between each of the 16 elements and the rating scale, after the rating is converted to a binary score, 0 or 100. This linkage is the coefficient from the model relating the presence/absence of the elements to the binary transformed rating. It will be the linkage, the coefficient, which provides the necessary data to create a gaming aspect to the Mind Genomics exercise.

Consider the tabulation of coefficients in Table 8. Table 8 presents the distribution of POSITIVE coefficients for six different groups which always appear in the Mind Genomics reports. The six groups are total panel, Mind Sets 1 and 2 from the two Mind-Set solutions, and then Mind Sets 1, 2 and 3 from the three Mind-Set solution. We saw the total panel and the results from the two mind-sets, but not from the three mind-sets.

We tabulate the frequencies of coefficients between 0 and 5, 5 and 10, 10 and 15, 15 and 20, and finally higher than 20. This tabulation generates a distribution of coefficients. We can either work with the absolute number of coefficients of a certain size (Computation 1) or weight the number of coefficients by the relative size of the subgroupsshowing the particular magnitude of coefficients (Computation 2.)

The summaries in Table 8 provide a quantitative, objective measure of ‘how good the elements are’ as they drive the response. When a student produces elements that score well across the different mind-sets, this is evidence of good thinking on the part of the study, thinking which is sufficiently powerful and expansive as to appeal to different-minded groups,

Table 8. Computation for the IDT, Index of Divergent Thought, a prospective gamifying metric to make Mind Genomics more interesting by being ‘gamified.’

|

Computation 1 – count the number of coefficients within the defined ‘range’, without accounting for the number of respondents showing the coefficient in their mind-set

Computation 1 does not account for the size of the mind-set

|

|

Group

|

Total

|

|

MS 1 of 2

|

MS 2 of 2

|

|

MS 1 of 3

|

MS 2 of 3

|

MS 3 of 3

|

|

Summary

|

|

Weight

|

1.0

|

|

0.6

|

0.4

|

|

0.4

|

0.3

|

0.3

|

|

|

|

Base

|

30

|

|

17

|

13

|

|

12

|

8

|

10

|

|

|

|

Regression Coefficient 0–9.99

|

6

|

|

3

|

4

|

|

3

|

1

|

1

|

|

18

|

|

Regression Coefficient 10–14.99

|

0

|

|

3

|

0

|

|

1

|

0

|

4

|

|

8

|

|

Regression Coefficient 15–19.99

|

0

|

|

0

|

3

|

|

3

|

1

|

0

|

|

7

|

|

Regression Coefficient 20+

|

0

|

|

2

|

2

|

|

1

|

4

|

3

|

|

12

|

|

Computation 2 – count the number of coefficients within the defined ‘range’, but weight each counted value by the proportion of all respondents (3xTotal) showing that coefficient. Computation 2 accounts for the size of the mind-set.

|

|

Group

|

Total

|

|

MS 1 of 2

|

MS 2 of 2

|

|

MS 1 of 3

|

MS 2 of 3

|

MS 3 0f 3

|

|

Summary

|

|

Weight (Base/Total)

|

0.33

|

|

0.19

|

0.14

|

|

0.13

|

0.09

|

0.11

|

|

|

|

Regression Coefficient 0–9.99

|

2.00

|

|

0.60

|

0.60

|

|

0.40

|

0.10

|

0.10

|

|

3.80

|

|

Regression Coefficient 10–14.99

|

0.00

|

|

0.60

|

0.00

|

|

0.10

|

0.00

|

0.40

|

|

1.10

|

|

Regression Coefficient 15–19.99

|

0.00

|

|

0.00

|

0.40

|

|

0.40

|

0.10

|

0.00

|

|

0.90

|

|

Regression Coefficient 20+

|

0.00

|

|

0.40

|

0.30

|

|

0.10

|

0.40

|

0.30

|

|

1.50

|

A one-year educational plan for Mind-Genomics to develop the student mind

- Goal: A one-year plan to create massive intellectual development among students through a once/week exercise using Mind Genomics through the BimiLeap program. The outcome… for each person, an individual portfolio of 20–30 studies showing topics investigated by the student … a portfolio to be shown proudly at interviews, and in school to be shared with fellow students, creating a virtuous circle of learning & knowledge

- The benefit to the education system: Create a school system which produces first rate creative thinking in younger students ages 7–13, high school students, and university students, each developing far beyond who they are today. Use the BiMiLeap program in the classroom or after school, once/week, to do a study in a topic area of intellectual interest, making it a social process which combines learning, true discovery, and competition,

- Process: Four students work together. The younger students work with an older ‘docent.’ The docent records the material, prepares input for BimiLeap, ensures that the input is correctly submitted to the APP, and reviews the automated report with the students in the group after the data are obtained. Each week, the composition of the group changes, allowing different students to collaborate.

- Mechanics: The actual mechanics of the approach are presented in this paper. Mind Genomics studies concern a single topic area and collects data by obtaining reactions through an experiment, albeit an experiment which looks like a survey, but is not. Each group will get a topic from school, create the materials, run the study, get the PowerPoint® report, discuss, add insights to the PowerPoint, present it in class to the other groups, incorporate the report into one’s personalized portfolio, and then repeat the process the following week with a reconstituted group.

- Specifics – Number of topics: We believe that one good policy is to select a set of 10 topic areas, so each topic is treated 2–3 times a year by the students. Each time, the group addresses one of the topics afresh, encouraged to think critically about it and not just accept or replicate prior knowledge. They are freed to create new knowledge on the topic by re-using, updating, or adding new content.

- Specifics – The ‘sweet spot’ for users: The older students focus on different aspects of a single general topic, with each student creating 8–12 reports on research about the mind of people responding to different aspects of the topic … Worthy of a PhD at the age of say 15, all while having fun, learning to think, collaborate, present.

- The BimiLeap program can be found at www.BimiLeap.com

References

- Kahneman D (2011) Thinking, Fast and Slow. Macmillan.

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A, Beckley J, Ashman H (2006) Founding a new science: Mind genomics. Journal of sensory studies 2: 266–307.

- Mc Cannon BC (2007) Using game theory and the Bible to build critical thinking skills. The Journal of Economic Education 38: 160–164.

- Lehman M, Kanarek J (2011) Talmud: Making a case for Talmud pedagogy—the Talmud as an educational model. In International Handbook of Jewish Education, Springer, Dordrecht, 581–596.

- Kent O (2006) Interactive text study: A case of havruta learning. Journal of Jewish Education 72: 205–232.

- Holzer E, 7 Kent O, (2011) Havruta: What do we know and what can we hope to learn from studying in havruta? In International handbook of Jewish education, Springer, Dordrecht, 404–417.

- Box GE, Hunter WG, Hunter JS (1978) Statistics for Experimenters, New York, John Wiley