Abstract

We present two methods-oriented studies on sexuality, one dealing with the discussion of sexuality in the context of a relationship, the second with the societal protection of sex workers. Both studies used consumer respondents to evaluate systematically varied combinations of messages about the topic, the combinations created by experimental design, following the method of Mind Genomics. Study 1 on discussions of sexual intimacy presents Mind Genomics to understand the way people process information, their criteria for decision-making, and the nature of possibly easy-to-understand mind-sets, i.e., different criteria of importance assigned to the same pieces of information. Study 2 on the protection and recourse given to legal workers shows how to assess the interaction between person and situation as drivers of judgments and drivers of engagement. Both studies point to the emerging science of Mind Genomics as an easy, rapid, and cost-effective ways to create archival databases, to introduce new ways of thinking, and to democratize research world-wide, respectively.

Introduction

During the past three decades the focus of researchers has steadily increased on issues involving intimacy, specifically sexual intimacy between consenting partners (love, romance), as well as sexual intimacy as a business (sex workers.) Sexuality in its many manifestations has always attracted research because of its centrality in daily life, but as society has evolved, issues of sexuality have become intertwined with emotions, with public health (e.g., sexually transmitted disease), and finally with issues of the law (e.g., prostitution and the issues revolving around sex workers.)

The topics of love, sexuality, sexual exploitations, and societal reactions each have spawned enormous literatures. Table 1 shows the number of ‘hits’ for Google® and for Google Scholar®, for each of these topics, at the time of this writing, December 2019,

Table 1. Number of citations dealing with sex and its ramifications.

|

Topic |

Citations–Google® |

Citations–Google Scholar® |

|

Love |

18 billion |

3.34 million |

|

Sexuality |

80 million |

2.47 million |

|

Sexual exploitation |

72 million |

1.03 million |

|

Societal response to sexual exploitation |

59 million |

0.20 million |

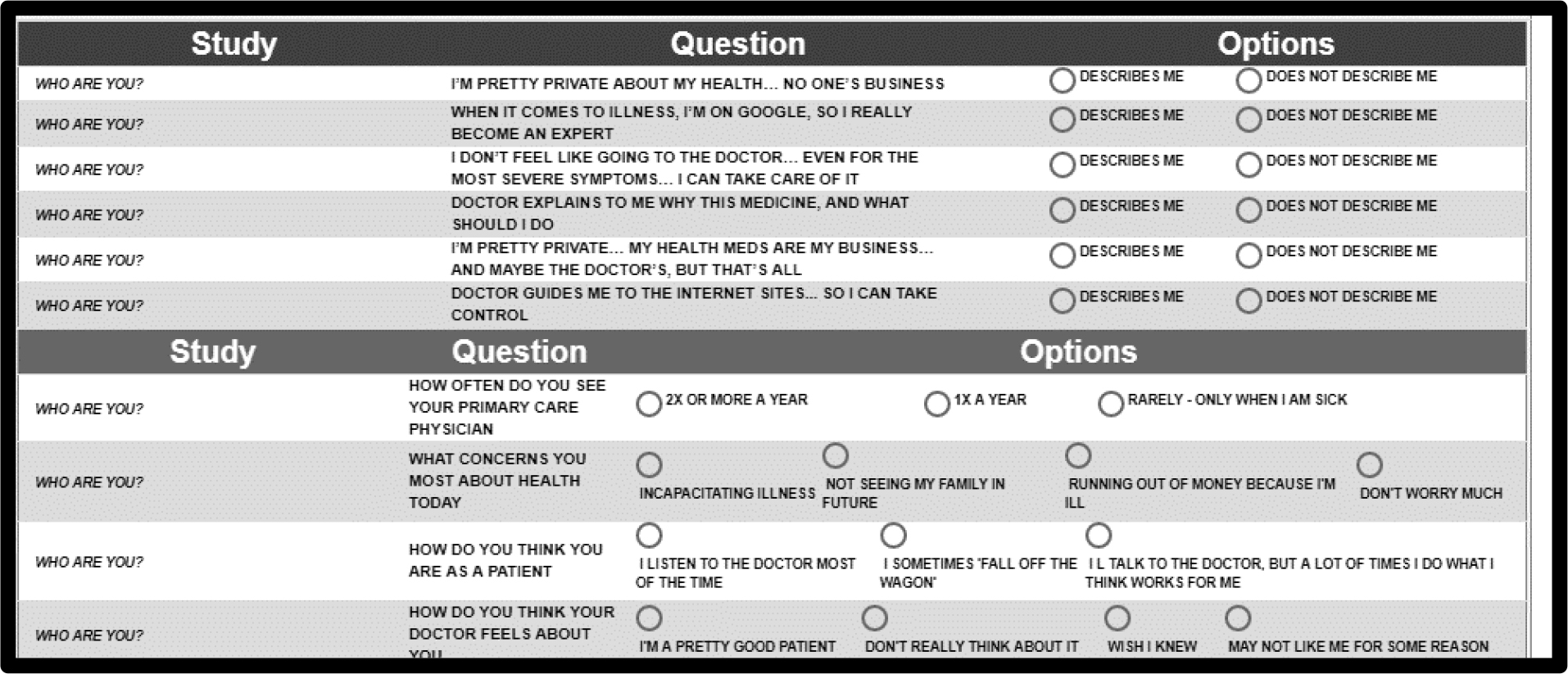

No set of studies can hope to be comprehensive, given the long history of the study of sexuality, the many manifestations in daily life, and the many cultures as well as stages of individual development that must be considered. Rather, we introduce here a new approach to the study of sexuality, the science of Mind Genomics, designed to take small snapshots of a topic, focus in depth on a specific, limited topic, and work with small, affordable samples of respondents.

The worldview of Mind Genomics involves a small, limited topic, investigating the patterns of decision making within that topic. Rather than emerging out of the history of the hypothetico-deductive method, isolating a variable and studying that variable in an experiment, Mind Genomics proceeds in the reverse direction. One might think of the Mind Genomics researcher as a cartographer faced with a new land. The cartographer measures the relevant variables of a topographical area, deduces the nature of the structure below, and maps the land. The cartographer creates maps, not theories. In the case of Mind Genomics, the ‘land’ is the world of sexuality. The cartography of this paper deals with the reactions to issues of sexual intimacy (one set of experiments), and reactions to issues of sex workers (another set of experiments.)

Exploring two topics of sex using Mind Genomics to generate insights and hypotheses

The topic of sexual behavior spans a wide range of topics, from the physical to the emotional to the legal, and to the societal. It is impossible to cover even a very small fraction of the topics with a set of experiments or surveys. The strategy of this paper is to demonstrate how the emerging science of Mind Genomics can generate an affordable, powerful database at the start of a research initiative, using simple ideas, simple thinking, consumer research, and powerful analyses, meaningful even with samples that are traditionally considered ‘small’.

The emerging science of Mind Genomics (Moskowitz & Gofman, 2007) [1], traces its intellectual heritage to the systematized thinking using experimental design to structure the test stimuli, as well as to sociology and consumer research for transforming the ideas into questions to be answered, and finally to the Socratic method to create the system as an inductive knowledge-development technique, easily applied in practice

Experimental design

Experimental design allows a researcher to understand the effects of a variable, either tested along in ‘splendid isolation’ or tested as part of a mixture (Box, Hunter & Hunter, 1978) [2]. Mind Genomics deals with the ordinary situation, wherein a person is presented with a combination of ideas, as the typical situation of daily life. The person responds to the combination, making a decision. But just what specific component of the combination or set of components ‘drive’ that decision? Experimental design sets up efficient combinations of independent variables, messages or elements in the language of Mind Genomics. It is the response to these systematically created mixtures, which, through regression reveals, quite directly the contribution of each Message or Element to the response. The response, in turn, is what the respondent answers.

Sociology and consumer research

These social science disciplines rely upon the responses of people to questions about behavior, or upon the measurement of the behavior of people in situations, i.e., upon attitude versus upon behavior, respectively. Where possible a meaningful behavioral measure may be better than an attitude, although the term ‘meaningful’ is important as a qualifier.

Over almost a century there has been a subtle current of belief that implicit measures are better than explicit ones, e.g., that EEG (brain waves) or GSR (activation) or pupil behavior (dilation, pupil motion) somehow are better than simple attitudinal ratings because the former are more objective, more biological (Boring, 1929) [3].

The foregoing use of ‘meaningful’ is not what is meant here. Rather, the term ‘meaningful’ is used in the sense that the measure to be meaningful must be a direct correlate of the mind of the person, whether person in society or an ordinary citizen faced with a choice. Mind Genomics uses the responses to combinations of messages, i.e., combinations of elements as the meaningful measure, since a great deal of behavior in everyday life is responses to mixtures. Mind Genomics goes the additional step by creating combinations of these messages, presenting them to respondents, measuring the reactions, and then estimating the contribution of each message.

The Socratic Method

The approach is grounded empiricism, not in the hypothetico-deductive method. There is no hypothesis to be tested. Rather, there is a topic to be studied. The topic of interest is presented to the researcher, who must create four questions which ‘tell a story’ about the topic. The questions are not necessarily final, but rather represent the way the topic is thought about, either those who are grounded in the topic, or even novices with no idea at all, so-called ‘newbies’. The four questions each motivate four answers, or a total of 16 answers, as shown in the next sections. The researcher then combines these answers into small vignettes, obtains responses to the vignettes, and shows how the different answers shed light on the topic.

The best way to show the Mind Genomics method is through a case history, dealing with a topic relevant to an individual, or even beyond the individual to a group, and to society. This paper focuses on two aspects of sexual behavior, the first dealing with discussions of sexual intimacy and disease protection between consenting partners, the second dealing with protection of the ‘sex’ worker. These are but two of the perhaps hundreds of topics in the rainbow of topics in sexuality. We show how a one-day experiment can produce data for each topic, making it feasible to explore hundreds of topics about sexuality in the time frame of a year, with affordable, rapid, insightful and archival data.

Study 1 – Discussinag disease prevention between two consenting & emotionally-involved partners

A great deal has been written about sexual relations between consenting partners, from issues to measurements (e.g., Fisher et. al., 2013; Montesi, et. al., 2013; Stephenson, et. al., 2010). [4, 5, 6] The topics range from the emotions felt by the participants to the behavior of adolescents versus older individuals, and on to the issues caused by the ravages of sexually transmitted disease (Harvey et al., 2016; Katz et al., 2000; Peplau et. al., 2007; Widman et. al., 2006). [7, 8, 9, 10] Our focus in this experiment is the couple’s discussion of issues around the prevention of sexually transmitted diseases using methods under their control. The study was motivated by author Ortiz’s plan to sponsor a campaign to reduce sexually transmitted disease.

Method

The Mind Genomics study begins with the creation of the four questions and the four answers to each question. These appear in Table 2 and were created by author Ortiz as part of a campaign against sexually transmitted diseases. The important thing to realize from Table 2 is that the study does not exhaust the topic. Indeed, Mind Genomics studies are not designed as single, exhaustive treatments of a subject, treatments which generate a large volume of disparate information. Rather, Table 2 shows a preliminary attempt to understand four aspects of the topic. The reality is that there may be 40 or 400 aspects of the topic. When one attempts to cover a topic thoroughly, the entire endeavor may collapse because, in common folk wisdom ‘the perfect is often the enemy of the good.’ The Mind Genomics strategy is to create a set of such small studies, accrete the results, and identify emergent patterns ‘from the bottom up.’ Mind Genomics represents the inductive way to learn, i.e., by discovering patterns, rather than by confirming or disconfirming ingoing hypotheses.

Table 2. Sexual Intimacy: Four questions and four answers to each question.

|

|

Question A: How do you communicate to your partner that you want to exchange STD results before sexual activity? |

|

A1 |

Discussing STD precautions planning in a phone conversation |

|

A2 |

Discussing STD precautions planning through texting |

|

A3 |

Discussing STD precautions planning in an email |

|

A4 |

Discussing STD precautions planning during lunch |

|

|

Question B: How do you ensure your own safety before, during, and after sex? |

|

B1 |

Using condoms during sex |

|

B2 |

Getting tested regularly |

|

B3 |

Both partners using birth controls |

|

B4 |

Knowing partner’s prior sexual history |

|

|

Question C: When is the best time to have a conversation with your partner about safe sex? |

|

C1 |

Talking about safe sex when you first start dating |

|

C2 |

Talking about safe sex before engaging in sexual activity |

|

C3 |

Talking about safe sex during the first conversation about intimacy |

|

C4 |

Talking about safe sex on the first date |

|

|

Question D: What kind of answers do you think a partner can give your request for safe sex? |

|

D1 |

Partner says: “Let’s get tested” |

|

D2 |

Partner says: “There’s no need for safe sex” |

|

D3 |

Partner says: “Let’s use protection” |

|

D4 |

Partner says: “Safe sex is the best move” |

The researcher combines these elements (the answers A1-D4) into small, easy to read combinations, so-called vignettes. The actual experimental design is created as ‘kernel,’ in which the 16 elements are statistically independent of each other, allowing for subsequent analysis by OLS (ordinary least-squares) regression. The kernel, or basic experimental design is permuted so that the design structure remains the same, but the individual combinations changes in a permutation pattern (Gofman & Moskowitz, 2010.) [11] Table 3 shows the experimental design for one respondent (independent variables in the subsequent analysis), and then the ratings, binary transformation (Bin) and Consideration or response Time (CT) (the dependent variables in the subsequent analysis.)

Table 3. Example of the data from one respondent, prepared for statistical analysis.

|

|

The 16 answers or elements in binary form. |

Ratings & transformation |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Vig |

A1 |

A2 |

A3 |

A4 |

B1 |

B2 |

B3 |

B4 |

C1 |

C2 |

C3 |

C4 |

D1 |

D2 |

D3 |

D4 |

Rating |

Top3 |

CT |

|

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

9 |

100 |

9.0 |

|

2 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

9 |

100 |

6.9 |

|

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

1 |

9.0 |

|

4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

9.0 |

|

5 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

0.7 |

|

6 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

5 |

0 |

0.4 |

|

7 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

100 |

0.3 |

|

8 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

1 |

0.7 |

The structure of the vignettes follows these conventions:

The experimental design, metaphorically a booklet of recipes of the same ingredients to create different dishes. The experimental design specifies the composition of vignettes comprising two elements, three elements, and four elements, respectively.

Each respondent is required to evaluate 24 vignettes, all different from each other. Across the 24 vignettes, each element appears five times and is absent 19 times. A vignette comprises at most one element or answer from any question (Table 3.) This strategy of testing both complete vignettes (one answer from each question) and incomplete vignettes (no answer from either one or two questions) ensures that the analysis of the data by OLS (ordinary least-squares) regression generates coefficients having absolute value, where ratios of coefficients are meaningful.

Each respondent evaluates 24 unique, different vignettes. The underlying experimental design ensures that the 24 vignettes for each respondent differ from the 24 vignettes for any other respondent. The benefit to this permutation scheme is that the Mind Genomics experiment covers a great deal of the so-called ‘design space’. The benefit to the researcher is one need not know ‘what works’ ahead of the study. In contrast, in other research methods using experimental design of messages (so-called conjoint analysis; Green & Srinivasan, 1990), [12] the researcher selects one set of combinations, and tests that set with many people in order to suppress the variation by averaging. Whether averaging out the variation in the typical approach or averaging out the variation by looking at a great deal of the design space ultimately proves to be better is still a matter of dispute.

Table 3 show the 24 vignettes as rows. The 16 elements are shown as A1-D4, corresponding to the four questions and the four answers in each question featured in Table 1.

The column labelled Rat is the 9-point rating assigned to the vignette by the respondent. Table 3 shows the respondent ratings of all 24 vignettes.

The column labelled Top3 is the ‘binary’ transformation of the 9-point ratings, with ratings of 1–6 transformed to 0, and a very small random number added to the transformed number For ratings 7–9 the rating is transformed to 100, and again a very small random number is added to the transformed number.

The addition of the random number is done so that the regression analysis will not ‘crash’ when the analysis creates individual-level models to generate mind-set segments. When a respondent rates all 24 vignettes between either 1–6 or between 7–9, respectively, then transformed ratings will all become either 0 or 100, respectively for the Top 3 measure, and the regression model using the Top3 measure as the dependent variable will ‘crash.’ Adding a small random number prevents that crash, ensuring that the statistical analysis proceeds without incident.

Finally, the column labelled CT is Consideration Time, or Response Time, defined as the number of seconds elapsing between the presentation of the vignette on the screen and the rating assigned by the respondent. The vignettes are short, so that any Consideration Time longer than 9 seconds is assumed to reflect the respondent’s multi-tasking and is brought to the value 9.0. The use of the term Consideration Time makes the number more meaningful to the reader, because the magnitude of the CT can be associated with the time it takes the respondent to consider the element.

The analysis of Mind Genomics data proceeds in a straightforward manner, enabled by the experimental design for the creation of the different vignettes. The experimental design created for a single individual ensures that the 16 elements or answers for that individual appear independently of each other among the 24 vignettes. Putting together a set of such experimental designs, each different from the others simply by a permutation scheme, maintain the statistical independence of the 16 elements.

An easy-to-interpret analysis (OLS Regression) relates the presence/absence of the 16 elements to the binary rating. OLS regression uses the 16 elements as independent variables, and the binary transformation, Top3, as the dependent variable. The regression incorporates the relevant cases, namely the 24 rows from each respondent who belongs to the subgroup. Thus, when it comes to the model or equation for ‘males,’ only the data from the male respondents are used. Each male respondent contributes 24 cases or observations.

The regression model estimates the parameters of this simple equation: Top3 = k0 + k1(A1) + k2(A2) … + k16(D4). Top3 is defined as ‘comfortable talking about the topic.

The parameters for the total panel and key subgroups appear in Table 4. The table shows total panel, gender, age groups, relationship status, and the response from all respondents, but broken out into the results from Vignettes 1–12 (Half1) and then from Vignettes 13–24 (Half2). This final comparison shows us whether the respondents ‘change their criteria’ as the study proceeds

Table 4. Parameters (additive constant, coefficients) for equations relating the presence/absence of the 16 elements for binary transformed rating ‘comfortable talking about the topic (prevention of sexually transmitted disease.)’. The table is sorted by the coefficients for the total panel.

|

|

Top 3 = Comfortable talking about the topic |

Tot |

Male |

Fem |

A25 Older |

A24 Younger |

Q3 Single |

Q3 Relationship |

Half1 |

Half2 |

|

|

Additive constant (k0) |

61 |

55 |

65 |

73 |

43 |

60 |

62 |

62 |

61 |

|

D3 |

Partner says: “Let’s use protection” |

6 |

5 |

8 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

5 |

6 |

|

A1 |

Discussing STD precautions planning in a phone conversation |

4 |

2 |

6 |

3 |

6 |

6 |

1 |

5 |

3 |

|

D4 |

Partner says: “Safe sex is the best move” |

4 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

3 |

7 |

0 |

9 |

-4 |

|

B2 |

Getting tested regularly |

4 |

8 |

0 |

3 |

4 |

-1 |

9 |

5 |

3 |

|

A2 |

Discussing STD precautions planning through texting |

3 |

-3 |

8 |

-1 |

6 |

1 |

4 |

-10 |

15 |

|

B3 |

Both partners using birth controls |

3 |

8 |

-3 |

-3 |

10 |

-5 |

11 |

13 |

-11 |

|

C2 |

Talking about safe sex before engaging in sexual activity |

3 |

4 |

3 |

-2 |

10 |

6 |

1 |

0 |

6 |

|

B4 |

Knowing partner’s prior sexual history |

3 |

9 |

-2 |

3 |

3 |

-2 |

9 |

5 |

3 |

|

B1 |

Using condoms during sex |

2 |

4 |

1 |

-1 |

6 |

-4 |

8 |

7 |

-4 |

|

C3 |

Talking about safe sex during the first conversation about intimacy |

2 |

8 |

-4 |

-2 |

7 |

3 |

0 |

-2 |

5 |

|

C1 |

Talking about safe sex when you first start dating |

-2 |

1 |

-3 |

-4 |

3 |

-3 |

0 |

-3 |

0 |

|

D1 |

Partner says: “Let’s get tested” |

-2 |

-6 |

2 |

-2 |

-2 |

-4 |

0 |

-1 |

-6 |

|

A4 |

Discussing STD precautions planning during lunch |

-2 |

-8 |

3 |

-1 |

-4 |

-3 |

-2 |

-6 |

2 |

|

A3 |

Discussing STD precautions planning in an email |

-3 |

-2 |

-3 |

-5 |

0 |

-3 |

-3 |

-8 |

3 |

|

C4 |

Talking about safe sex on the first date |

-8 |

-5 |

-10 |

-8 |

-7 |

-8 |

-8 |

-9 |

-6 |

|

D2 |

Partner says: “There’s no need for safe sex” |

-28 |

-22 |

-33 |

-27 |

-29 |

-30 |

-26 |

-25 |

-33 |

The additive constant is a measure of basic comfort talking about the topic, but with no elements in the vignette. The basic comfort for the total panel is 61, meaning that in the absence of any elements, 61% of the responses will be 7–9. That is, about 3 in 5 times the response will be ‘comfortable.’ The only group showing less comfort is the younger respondents (additive constant = 43), whereas their complementary age group, the older respondents, age 25 and older, is more comfortable (additive constant = 73).

There are some elements which ‘stand out’ from the others, topics about which the respondents feel very comfortable discussing. The elements below list the strong performing elements. Although there are strong performing elements, as shown by the coefficient, an underlying theme or story does not appear.

Total – None

Males

Knowing partner’s prior sexual history

Getting tested regularly

Both partners using birth controls

Talking about safe sex during the first conversation about intimacy

Females

Partner says: “Let’s use protection”

Discussing STD precautions planning through texting

Age 25 or older – None

Age 24 or younger

Talking about safe sex before engaging in sexual activity

Both partners using birth controls

Single – None

In a relationship

Both partners using birth controls

Getting tested regularly

Knowing partner’s prior sexual history

Using condoms during sex

First half of the individual’s vignettes (vignette 01- vignette 12)

Both partners using birth controls

Partner says: “Safe sex is the best move”

Second half (vignette 13 – vignettes 24)

Discussing STD precautions planning through texting

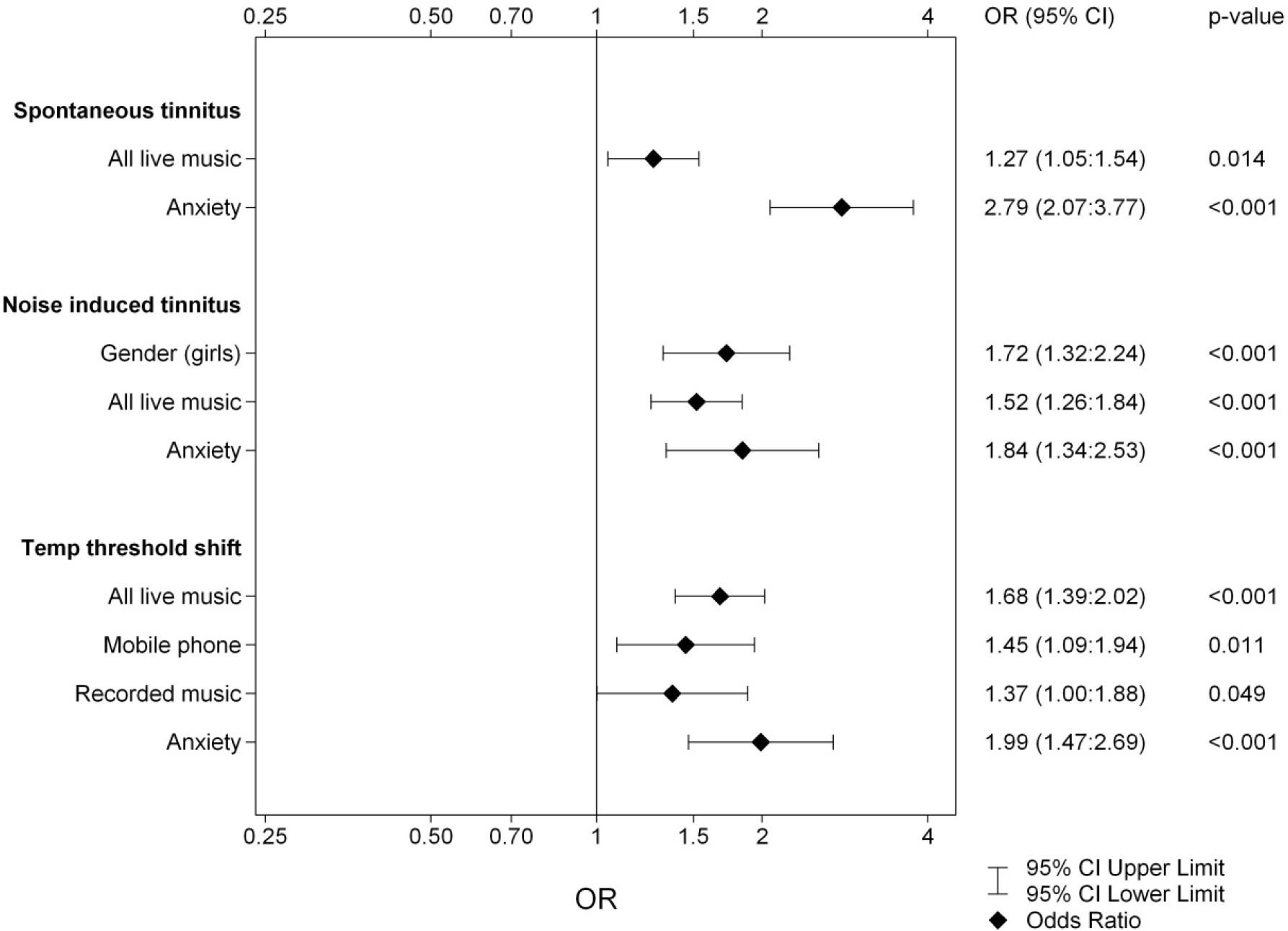

An increasing focus of Mind Genomics is upon Consideration Time (CT). In experimental psychology the term Consideration Time may be replaced by either Reaction Time or Response Time. CT is defined as the number of seconds (to the nearest tenth of second) between the presentation of the test stimulus, the vignette, and the rating assigned by the respondent. The term Consideration Time’ is used to underscore that the response is not only the time to perceive and react, but to read and consider.

The computation of response time is straightforward. The Mind Genomics algorithm relates the response time to the presence/absence of the elements, using the same form of equation as done for the Top3 value (comfort, in Table 3). The only difference is that the equation for consideration time has no additive constant. That is, the ingoing assumption is that without any elements in the vignette, the consideration time should be 0.

Table 5 shows the six elements with long consideration times in at least one group of responses or in either the first half or the second half of the Mind Genomics experiment, respectively. In turn, Table 6 shows the Consideration Times for the full set of elements across the different subgroups.

Table 5. The six elements showing long (estimated) consideration times of 1.5 seconds or longer.

|

|

Elements showing long consideration times (1.5 seconds +) |

Groups |

|

C3 |

Talking about safe sex during the first conversation about intimacy |

4 |

|

C2 |

Talking about safe sex before engaging in sexual activity |

3 |

|

B3 |

Both partners using birth controls |

2 |

|

A4 |

Discussing STD precautions planning during lunch |

1 |

|

D4 |

Partner says: “Safe sex is the best move” |

1 |

|

B4 |

Knowing partner’s prior sexual history |

1 |

To give a perspective, the typical consideration time of a full vignette for less serious topics may be 1–2 seconds. People make up their mind quickly for topics considered to be of minor import, perhaps System 1 in the language of Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman in his book Thinking Fast, Thinking Slow (Kahneman, 2011) [13] In contrast, topics of sexual discussion may involve System 2, the slower, more deliberate thinking which is the hallmark of a serious topic.

Table 6. The full set of consideration times for the total panel and key subgroups.

|

|

Consideration Time |

Total |

Male |

female |

Age 25+ |

Age 24 Younger |

Single |

Relationship |

First Half |

Second Half |

|

B3 |

Both partners using birth controls |

1.4 |

1.4 |

1.4 |

1.5 |

1.4 |

1.6 |

1.2 |

1.5 |

1.0 |

|

C2 |

Talking about safe sex before engaging in sexual activity |

1.4 |

0.8 |

1.9 |

1.3 |

1.5 |

1.0 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

1.2 |

|

C3 |

Talking about safe sex before engaging in sexual activity |

1.4 |

1.4 |

1.5 |

1.3 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

1.3 |

1.6 |

1.4 |

|

A4 |

Discussing STD precautions planning during lunch |

1.3 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

0.9 |

1.8 |

1.1 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

|

B1 |

Using condoms during sex |

1.3 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

1.4 |

1.0 |

|

A2 |

Discussing STD precautions planning through texting |

1.2 |

1.1 |

1.2 |

1.1 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

1.1 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

|

B4 |

Knowing partner’s prior sexual history |

1.2 |

1.0 |

1.3 |

1.0 |

1.4 |

1.4 |

0.9 |

1.6 |

0.7 |

|

C1 |

Talking about safe sex when you first start dating |

1.1 |

0.8 |

1.4 |

0.9 |

1.4 |

1.2 |

1.1 |

1.4 |

0.9 |

|

D4 |

Partner says: “Safe sex is the best move” |

1.1 |

1.0 |

1.2 |

0.9 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

1.1 |

1.5 |

0.8 |

|

A1 |

Discussing STD precautions planning in a phone conversation |

1.0 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

0.8 |

0.6 |

1.3 |

|

A3 |

Discussing STD precautions planning in an email |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.1 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.1 |

1.0 |

|

C4 |

Talking about safe sex on the first date |

1.0 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

1.1 |

|

B2 |

Getting tested regularly |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

0.6 |

|

D3 |

Partner says: “Let’s use protection” |

0.9 |

0.6 |

1.2 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

1.0 |

0.8 |

1.4 |

0.3 |

|

D2 |

Partner says: “There’s no need for safe sex” |

0.8 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

1.0 |

0.7 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

0.6 |

|

D1 |

Partner says: “Let’s get tested” |

0.7 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

1.4 |

0.2 |

Three emergent mind-sets

One of the ongoing tenets of Mind Genomics is that within any topic where human judgment plays a role, there are usually at least two different groups of people, having different criteria about the same topic. That is, for those topics involving judgment, people disagree. The disagreement may be minor, or major, depending upon the people, the topic, and the information presented.

Researchers have uncovered these differences as a matter of course when studying the criteria for human judgment. The differences themselves exist, but Mind Genomics goes one step further beyond noting the differences. Mind Genomics attempts to uncover, classify and then understand the nature of these differences, creating a set of mind-sets embodying the different criteria for judgment. Mind Genomics can go one step further, creating a tool, the PVI (personal viewpoint identifier), to predict the way new people will respond to the information, i.e., an assignment tool. The analogy is to color science and colorimetry. Mind Genomics creates the ‘color science’ for a topic, and then crafts the tool to identify these mind-sets in the population at large. In the interest of length, the PVI for these data are not presented in this paper.

Mind Genomics follows these steps to identify the emergent mind-sets, with all the information needed present in the data from the basics study:

- Create the data matrix, with the rows corresponding to the respondents, and the columns corresponding to the elements. For the data presented here, the data matrix comprises 16 columns, one for each element. (The additive constant is not used). The data matrix comprises 50 rows, one row for each respondent.

- Define the distance between rows (respondents) by a single number. The choice of the number can range from the simple Euclidean distance to a distance between patterns, defined as (1-Pearson correlation between two rows). Mind Genomics uses the latter (1 – Pearson Correlation, or 1-R).

- The distance metric (1-R) ranges from a low of 0 when two rows are perfectly correlated, to a high of 2 when two rows are perfectly but inversely correlated.

- The program, k-means clustering (Dubes & Jain, 1980), [14] creates complementary and exhaustive groups, called clusters or segments.

- Mind Genomics creates two clusters and assigns each respondent to one of the two clusters.

- Mind Genomics then creates three clusters, and assigns every respondent to one of the three clusters

- The data from respondents in each cluster are analyzed separately, first for the model for comfort (Top3) and then for the model for Consideration Time.

- The strongest performing elements for each set of clusters are used to determine whether there is a coherent story (interpretability), and whether the number of clusters is as few as necessary (parsimony). It is important to have as few clusters (mind-sets) as possible, provided that the clusters are interpretable, i.e., make sense.

Table 7 suggests three mind-sets, based upon the clustering using the coefficients for comfortable. Recall that the ingoing coefficients come from the data wherein the response (1–9 scale) was converted to 0 (ratings 1–6) or 100 (ratings 7–9.).

Table 7. Coefficients for ‘Comfortable with talking about the topic of preventing sexually transmitted disease,’ as well as Consideration Time, for three emergent mind-sets.

|

|

|

Top 3 = Comfortable talking about the topic |

|

Consideration |

||||

|

|

|

MS1 |

MS2 |

MS3 |

|

MS1 |

MS2 |

MS3 |

|

|

Additive constant (k0) |

59 |

69 |

52 |

|

NA |

NA |

NA |

|

|

Mind-Set 1 – Actual conversation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

D3 |

Partner says: “Let’s use protection” |

17 |

2 |

-2 |

|

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

|

D4 |

Partner says: “Safe sex is the best move” |

10 |

3 |

-9 |

|

1.3 |

1.0 |

1.1 |

|

B2 |

Getting tested regularly |

9 |

0 |

-5 |

|

0.9 |

1.0 |

0.7 |

|

D1 |

Partner says: “Let’s get tested” |

9 |

-6 |

-14 |

|

1.0 |

0.5 |

0.8 |

|

|

Mind-Set 2 – Discuss safe sex as prelude to intimacy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A1 |

Discussing STD precautions planning in a phone conversation |

1 |

7 |

-4 |

|

0.5 |

1.9 |

-0.3 |

|

C2 |

Talking about safe sex before engaging in sexual activity |

-1 |

7 |

-2 |

|

1.2 |

1.6 |

0.9 |

|

C3 |

Talking about safe sex during the first conversation about intimacy |

-2 |

5 |

0 |

|

1.5 |

1.6 |

1.0 |

|

|

Mind-Set 3 – Safe sex the responsibility of both partners |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

B3 |

Both partners using birth controls |

4 |

0 |

5 |

|

1.3 |

1.8 |

0.7 |

|

|

Not- comfortable for any segment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

C1 |

Talking about safe sex when you first start dating |

-6 |

-1 |

4 |

|

1.3 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

|

B4 |

Knowing partner’s prior sexual history |

6 |

0 |

1 |

|

1.5 |

1.3 |

0.5 |

|

A2 |

Discussing STD precautions planning through texting |

1 |

4 |

0 |

|

0.9 |

1.7 |

0.3 |

|

B1 |

Using condoms during sex |

4 |

2 |

-1 |

|

1.4 |

1.4 |

0.6 |

|

A4 |

Discussing STD precautions planning during lunch |

-11 |

1 |

-1 |

|

0.8 |

2.0 |

0.2 |

|

A3 |

Discussing STD precautions planning in an email |

-1 |

-7 |

-4 |

|

0.3 |

2.0 |

0.0 |

|

C4 |

Talking about safe sex on the first date |

-13 |

-6 |

-5 |

|

0.9 |

1.2 |

0.6 |

|

D2 |

Partner says: “There’s no need for safe sex” |

-13 |

-50 |

-7 |

|

0.8 |

1.1 |

0.5 |

The three mind-sets can be really divided into one group which feels comfortable with actual conversation as shown by quotation marks (Mind-Set 1), and the remaining two groups, which are less responsive to the elements. We might be satisfied with two mind-sets, not three, one responsive to conversation (Mind-Set 1), and others. On the other hand, the differences between Mind-Set 2 (Discuss safe sex as a prelude to intimacy) and Mind-Set 3 (Safe sex as the responsibility of both partners) points to some key differences between these two groups. That difference between Mind-Sets 2 and 3 is underscored by the differences between the mind-sets in terms of Consideration Time. Mind-Set 2 (discuss safe sex) spends a lot longer than Mind-Set 3 (focuses on responsibility) when reading and rating the vignettes.

Study 2 – Recourse & Protection for the sex worker

The recent literature is replete with discussions of sex trafficking, and other offenses (Van der Meulen, et. al., 2018; Kempadoo & Doezema, 2018) [15, 16] Those stories talk about the system which creates and benefits from the sex worker, and not generally about the sex worker in terms of emotions and personal development (Bekteshi et. al., 2012; McClain & Garrity, 2011.) [17, 18].

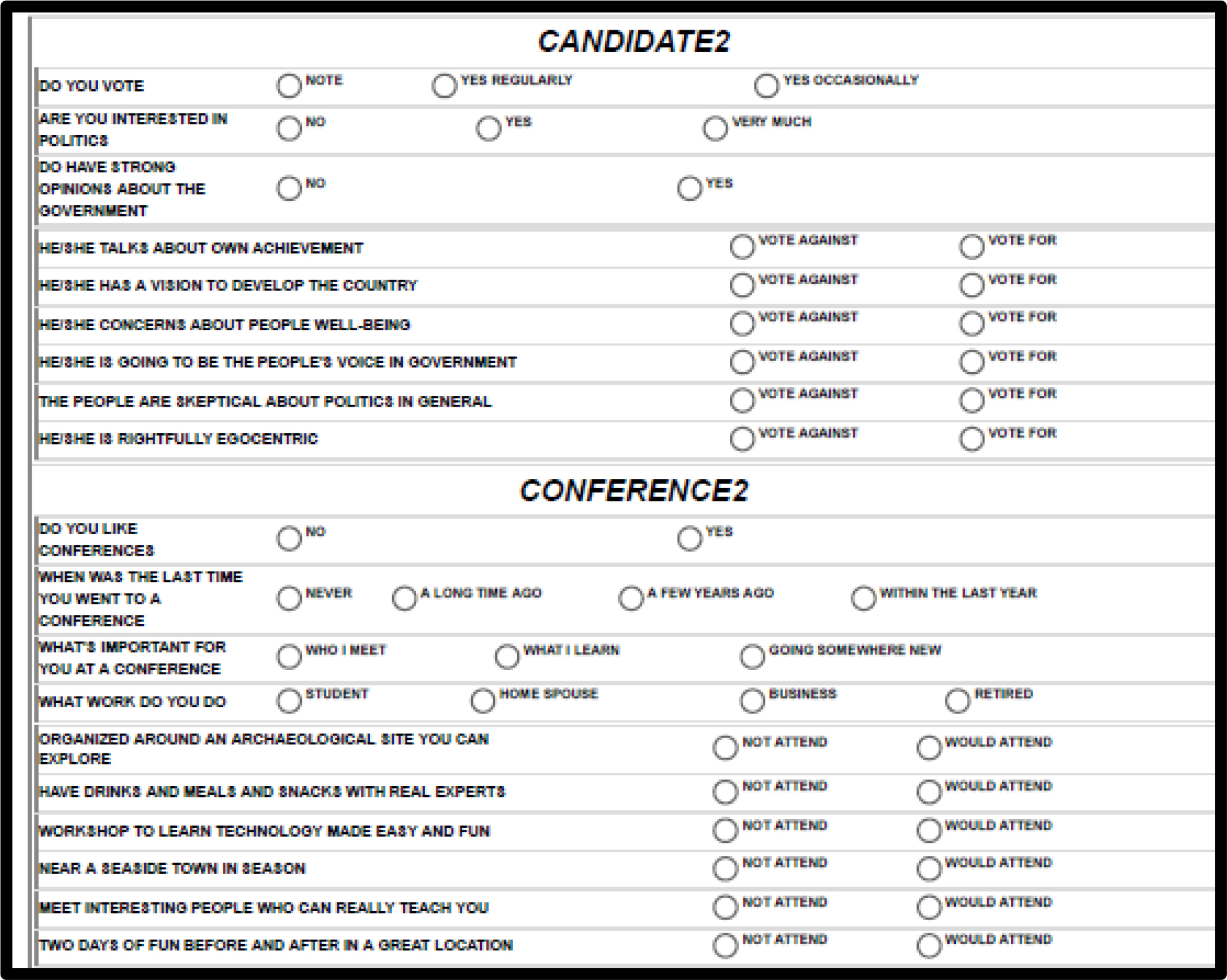

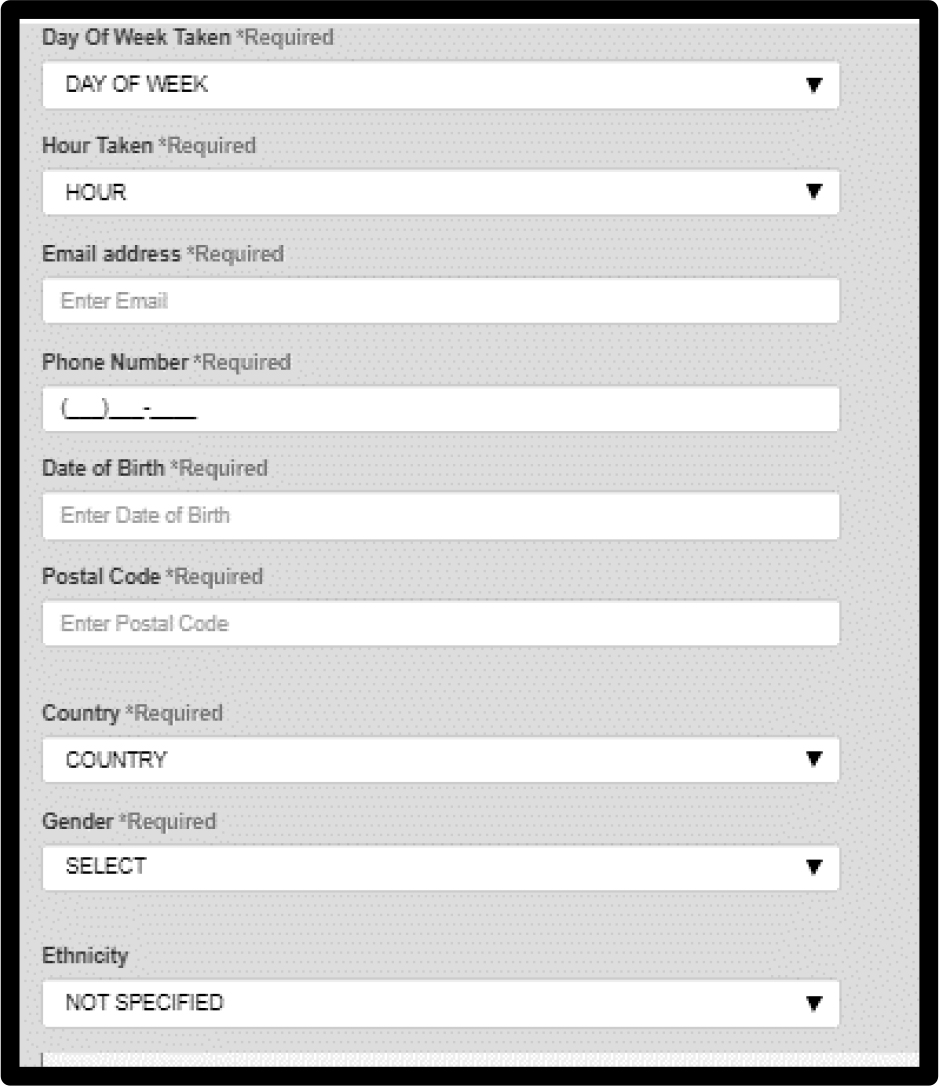

This second study was inspired by the interests of marketing students in a graduate course in Bogota, Colombia. The students under the instruction of a8uthor Herrera, investigated the nature and magnitude of the interaction between the WHO (who is the sex worker), the DANGER (what is the danger facing a sex worker in Colombia), as they drive the response of ‘protection of’ and ‘legal recourse available to’ the sex worker. Over the past decades there has been a recognition that prostitution and allied activities constitute a profession with the workers deserving he benefits and protection due to any person who works in a job. The study approach was the same, in terms of creating the four questions, developing four answers to each question (Table 8), and then presenting the vignettes to the respondents. The 24 students themselves offered to be respondents, and so we present this second study as a methodological advancement within the emerging science of Mind Genomics.

Table 8. Sex worker – Four questions and four answers to each question.

|

|

Question A: Who is the person who is the sex worker? |

|

A1 |

Worker: A young woman who is just starting out in life |

|

A2 |

Worker: An older woman who has gone bankrupt |

|

A3 |

Worker: A young, very handsome, male student who needs money |

|

A4 |

Worker: A young, very beautiful, female student who needs money |

|

|

Question B: What is a danger which confront a sex worker? |

|

B1 |

Danger: Getting beaten up and robbed |

|

B2 |

Danger: Not getting paid |

|

B3 |

Danger: Shunned as undesirable person |

|

B4 |

Danger: Shame and disgraceful feelings inside |

|

|

Question C: How do we institute ongoing physical safety for the sex worker? |

|

C1 |

Protection: Have officers assigned to red light districts |

|

C2 |

Protection: Register them and give them safety electronic alarms |

|

C3 |

Protection: Have the local newspaper write positive articles about sex workers |

|

C4 |

Protection: Have a special legal office to deal with those hurt sex workers |

|

|

Question D: What legal recourse can we create for the sex worker? |

|

D1 |

Legal Recourse: Special attorneys for sex workers |

|

D2 |

Legal Recourse: Steep fines for those who cheat sex workers |

|

D3 |

Recourse: Special “shaming” notices for those who hurt sex workers |

|

D4 |

Legal Recourse: Union for sex workers, to increases rights |

Creating scenarios to uncover interactions among answers

The first study presented in the previous sections treated all 16 answers as independent variables, which in fact they are. In this second study, we created the study specifically to comprise a WHO (the sex worker), the danger that the person would face (DANGER), and then two different types of protection (ongoing physical safety, legal recourse, respectively.) Thus, the first two answers are really ‘set-ups’ to frame the information, that information given by protection and recourse. The objective was to identify how different ‘set-ups,’ i.e., combinations of WHO and DANGER, drive the response to protections and to recourse, respectively. The analysis below explicates the approach to study interactions, using two sets of vignettes. The first set comprises a single sex worker exposed to four different dangers. The second set comprises four sex workers, each facing the same danger.

Set 1 – sex worker constant, danger varies

Select one person to study. It does not matter which one, since we are interested in the method. For the sake of simplicity, we study one specific sex worker; an older woman who has gone bankrupt. We create five different strata, varying by the danger to which the individual (older woman) can be exposed. Each stratum thus can be defined as having one type of worker (the older woman), and one type of danger. Each individual danger and ‘no danger’ jointly define the stratum. For each stratum we run a simple model using the eight elements as predictors, the four elements describing physical protection, and the four elements describing legal recourse. Our model has no additive constant, because the rating is ‘agree/disagree.’ The additive constant makes no intuitive sense. We create this model for the rating question, again converted to binary (Top2, for agree), and then for consideration time. Table 9 presents the coefficients for agree (coefficients of 60 or higher shown in shaded cells, bold type.) Table10 presents the coefficients for consideration time (5 seconds and higher shown in shaded cell, bold type.) Both tables also show the average coefficient across all eight elements.

Table 9. Interactions between Sex Worker, Danger as stratifying variables, and legal recourse and protection as variables to be considered when disagreeing or agreeing.

|

|

Person constant, danger varies |

Worker: An older woman who has gone bankrupt |

||||

|

|

Agree (Top2 on the 5-point rating scale) |

Danger: Absent from vignette |

Danger: Not getting paid |

Danger: Shunned as undesirable person |

Danger: Getting beaten up and robbed |

Danger: Shame and disgraceful feelings inside |

|

|

Average Agree Coefficient |

31 |

25 |

22 |

22 |

21 |

|

D1 |

Legal Recourse: Special attorneys for sex workers |

64 |

35 |

66 |

20 |

101 |

|

C3 |

Protection: Have the local newspaper write positive articles about sex workers |

61 |

40 |

45 |

14 |

-14 |

|

C1 |

Protection: Have officers assigned to red light districts |

46 |

9 |

12 |

47 |

-114 |

|

C2 |

Protection: Register them and give them safety electronic alarms |

40 |

51 |

12 |

26 |

8 |

|

C4 |

Protection: Have a special legal office to deal with those hurt sex workers |

21 |

4 |

-20 |

12 |

-59 |

|

D3 |

Recourse: Special “shaming” notices for those who hurt sex workers |

16 |

41 |

37 |

25 |

114 |

|

D2 |

Legal Recourse: Steep fines for those who cheat sex workers |

1 |

44 |

49 |

60 |

80 |

|

D4 |

Legal Recourse: Union for sex workers, to increases rights |

0 |

-27 |

-23 |

-30 |

49 |

The coefficients are high because two of the variables are not considered in the model. Thus, the binary transformed rating, ‘agree’ (4–5), must be allocated across eight elements, not 16 elements, even though the vignettes still comprised 2–4 elements.

What is remarkable about the table is the dramatic interaction among the ingoing facts of the case, specifically WHO the sex worker is, and the DANGER the sex worker faces, and the specific protections and recourses selected.

- On average across the eight elements (four protection, four recourse), the level of agreement is similar close across all four Dangers for the single person (older woman)

- Yet, the specific interactions are dramatic. For example, when the Danger is shame and disgraceful feelings inside’ the sex worker, the strongest Recourse is: Special “shaming” notices for those who hurt sex workers. In contrast, when the Danger is getting beaten up and robbed, the strongest performing else is the legal Recourse: Steep fines for those who cheat sex workers.

When we move to Consideration Time (Table 10), we see that with an older woman who has gone bankrupt, we emerge with dramatically different Consideration Times. The longest Consideration Time comes from the combination of the older woman with ‘not getting paid’ and with ‘shunned as undesirable person’, both an average of 4.6 seconds.

Table 10. Interactions between Sex Worker, Danger as stratifying variables, and legal recourse and protection as variables driving ‘Consideration Time’ when rating disagree vs agree.

|

|

Person constant, danger varies |

Worker: An older woman who has gone bankrupt |

||||

|

|

Consideration Time |

Danger: Absent from vignette |

Danger: Not getting paid |

Danger: Shunned as undesirable person |

Danger: Getting beaten up and robbed |

Danger: Shame and disgraceful feelings inside |

|

|

Average Consideration Time across C1-D4 |

3.5 |

4.6 |

4.6 |

3.6 |

2.0 |

|

C4 |

Protection: Have a special legal office to deal with those hurt sex workers |

7.1 |

3.6 |

4.9 |

2.3 |

0.5 |

|

C1 |

Protection: Have officers assigned to red light districts |

5.8 |

6.0 |

7.4 |

-3.7 |

-6.4 |

|

C2 |

Protection: Register them and give them safety electronic alarms |

5.5 |

5.4 |

4.2 |

-1.2 |

-2.1 |

|

C3 |

Protection: Have the local newspaper write positive articles about sex workers |

4.6 |

7.3 |

3.9 |

1.1 |

-1.6 |

|

D1 |

Legal Recourse: Special attorneys for sex workers |

3.8 |

3.5 |

3.3 |

6.1 |

0.6 |

|

D3 |

Recourse: Special “shaming” notices for those who hurt sex workers |

0.8 |

2.3 |

6 |

7.8 |

7.7 |

|

D2 |

Legal Recourse: Steep fines for those who cheat sex workers |

0.5 |

4.2 |

4.1 |

7.9 |

9.1 |

|

D4 |

Legal Recourse: Union for sex workers, to increases rights |

0.2 |

4.5 |

3.2 |

8.2 |

8.1 |

There is also a noticeable interaction between the person (older woman who has gone bankrupt), the nature of the danger from the outside (not getting paid / shunned as undesirable), versus from the inside (‘’shame and disgraceful feelings.”). The outside actions / dangers generate longer Consideration Times.

The Consideration Times do not generate as clear a pattern as do the Agreement coefficients. So-called ‘objective measures’ in research may be attractive because of a belief that they are ‘tapping something real,’ but the interpretation of what they are tapping may be harder, and undoubtedly problematic.

Set 2 – danger constant, person varies

Select one danger to study. It does not matter which danger is held constant for purposes of explicating the approach. For simplicity, we focus on an emotional danger from the person’s self-image, ‘shame disgraceful feeling inside.’ As before, we create five different strata anew, varying by the sex worker. Thus, each of five strata has one danger (shame disgraceful feeling inside) and one of four sex workers, as well as the case of ‘no sex worker’.

For each of the five strata we run a simple model using the eight elements as predictors, as we did before, the four for physical protection, and the four for legal protection, respectively Our model has no additive constant. Table 11 presents the coefficients for agree (coefficients of 60 or higher shown in shaded cells, bold type.) Table 12 presents the coefficients for consideration time (5 seconds and higher shown in shaded cell, bold type.) Both tables also show the average coefficient across all eight elements.

- On average, for a given danger, the average coefficients vary, from a high achieved by vignettes featuring the young woman who is just starting out (average coefficient = 35), to a low achieved by vignettes featuring an older woman who has gone bankrupt (average = 21).

- When the danger is ‘shame and disgraceful feelings inside’), most of the strong performing elements are plausible, i.e., legal recourse, rather than protection. The shame and disgraceful feelings do not present danger.

Table 11. Interactions between Danger and Worker as stratifying variables, and legal recourse and protection as variables to be considered when disagreeing or agreeing.

|

|

Danger constant, person varies |

Danger: Shame and disgraceful feelings inside |

||||

|

|

Agree: Needs social intervention below |

Worker: Absent from vignette |

Worker: A young woman who is just starting out in life |

Worker: A young, very beautiful, female student who needs money |

Worker: A young, very handsome, male student who needs… |

Worker: An older woman who has gone bankrupt |

|

|

Average coefficient C1-D4 |

40 |

35 |

31 |

30 |

21 |

|

D4 |

Legal Recourse: Union for sex workers, to increases rights |

67 |

67 |

120 |

-28 |

49 |

|

D2 |

Legal Recourse: Steep fines for those who cheat sex workers |

60 |

11 |

-8 |

70 |

80 |

|

D1 |

Legal Recourse: Special attorneys for sex workers |

49 |

50 |

54 |

19 |

101 |

|

D3 |

Recourse: Special “shaming” notices for those who hurt sex workers |

44 |

-21 |

33 |

41 |

114 |

|

C1 |

Protection: Have officers assigned to red light districts |

36 |

49 |

37 |

33 |

-114 |

|

C3 |

Protection: Have the local newspaper write positive articles about sex workers |

34 |

33 |

22 |

28 |

-14 |

|

C2 |

Protection: Register them and give them safety electronic alarms |

34 |

47 |

-19 |

48 |

8 |

|

C4 |

Protection: Have a special legal office to deal with those hurt sex workers |

-3 |

42 |

9 |

29 |

-59 |

Finally, Table 12 shows the how Consideration Time for each of the protection and recourse elements vary with the single fixed danger (shame and disgrace inside), the four different types of sex workers, and the Consideration Time. All Consideration Times are high (4.2- 4.8) except for the older woman who has gone bankrupt (2.0). For the younger sex workers, the focus is protection. For the older sex worker, the focus is legal recourse.

Table 12. Interactions between Danger and Worker as stratifying variables, and legal recourse and protection as variables affecting Consideration Time when assigning a rating of disagree agree for legal recourse and protection.

|

|

Danger constant, person varies |

Danger: Shame and disgraceful feelings inside |

||||

|

|

Consideration Time |

Worker: Absent from vignette |

Worker: A young woman who is just starting out in life |

Worker: A young, very beautiful, female student who needs money |

Worker: A young, very handsome, male student who needs |

Worker: An older woman who has gone bankrupt |

|

|

Average Consideration Time C1-D4 |

3.9 |

4.6 |

4.8 |

4.2 |

2.0 |

|

C1 |

Protection: Have officers assigned to red light districts |

9.4 |

7.0 |

8.8 |

2.3 |

-6.4 |

|

C4 |

Protection: Have a special legal office to deal with those hurt sex workers |

9.2 |

6.7 |

9.1 |

2.9 |

0.5 |

|

C3 |

Protection: Have the local newspaper write positive articles about sex workers |

7.9 |

5.0 |

5.7 |

4.5 |

-1.6 |

|

C2 |

Protection: Register them and give them safety electronic alarms |

6.7 |

3.0 |

4.3 |

3.5 |

-2.1 |

|

D4 |

Legal Recourse: Union for sex workers, to increases rights |

0.6 |

7.4 |

4.7 |

4.3 |

8.1 |

|

D3 |

Recourse: Special “shaming” notices for those who hurt sex workers |

-0.4 |

0.1 |

5.3 |

5.6 |

7.7 |

|

D2 |

Legal Recourse: Steep fines for those who cheat sex workers |

-1.0 |

1.9 |

-0.1 |

6.6 |

9.1 |

|

D1 |

Legal Recourse: Special attorneys for sex workers |

-1.2 |

5.3 |

0.9 |

3.7 |

0.6 |

Discussion – Mind Genomics as a tool to map and to understand relationships

As suggested by the introduction, the field of sexuality, and especially the sexual behavior of intimate couples and the issues involved with sex workers have created in their wake an enormous literature. This paper does not address that literature, and especially does not attempt to answer questions raised by previous studies. Such an effort requires an encyclopedia of papers, not a single short research note. Rather, the objective here is to introduce a way to understand a topic from the inside-out, from the mind of the person, from a combination of psychological ‘thinking’ and consumer research methods.

The tradition of today’s science can be summarized by the term ‘hypothetico-deductive.’ The term means that we create a hypothesis about the nature of behavior, and then perform the requisite experiments either to falsify the hypothesis, or to not-falsify it. Not falsifying a hypothesis does not mean that the hypothesis is correct, but rather that for the time-being the hypothesis may be accepted. The focus of today’s research thus becomes increasingly narrow. The rigors of scientific research demand an almost superhuman concentration to focus the research on the specific problem. Little is left to the exploration of new ideas.

When it comes to the study of human behavior, the many aspects, the nuances, and the impossible-to-remove interactions among the variables make the hypothetico-deductive system interesting, but not particularly productive. One has pieces of information, some convincing than others. Yet, one is missing a narrative, not necessary spun from narratives and stories, but rather emerging from easy-to-do studies. The sheer difficulty of doing inexpensive, comprehensive, focused experiments with people force the researcher either to rely on questionnaires (self-reports), or to weave a story from interviews, or a limited number of experiments.

The approach presented here, Mind-Genomics, demonstrates the opportunity to create a new archival literature on people, personal relations, focusing either on specifics, on limited topics, or on a set of topics which bring into focus a bigger picture. What we see in these two studies is the relative ease of doing computer-aided experiment with messaging in order to identify how the person thinks about a topic. The experiments are short, iterative, yet generate information emerging from the structure of the experiment. The test stimuli are cognitively rich. The richness means that beyond the emergent patterns (what other studies discover) lies the responses to individually, meaningful, relevant, and possible important stimuli. The responses to the individual stimuli teach, rather than having value simply because they are part of an emergent pattern.

Acknowledgement

Attila Gere wishes to acknowledge and thank the Premium Postdoctoral Research Program of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

References

- Moskowitz HR, Gofman A, (2007) Selling blue elephants: How to make great products that people want before they even know they want them. Pearson Education.

- Box GE, Hunter WG, Hunter JS (1978) Statistics for experimenters, New York, John Wiley.

- Boring EG (1929) A History of experimental psychology. The Century Company, New York.

- Fisher TD, Davis CM, Yarber WL (2013) Handbook of sexuality-related measures. Routledge.

- Montesi JL, Conner BT, Gordon EA, Fauber RL, Ki KH, et al. (2013) On the relationship among social anxiety, intimacy, sexual communication, and sexual satisfaction in young couples. Archives of Sexual Behavior 42: 81–91. [Crossref]

- Stephenson KR, Meston CM (2010) When are sexual difficulties distressing for women? The selective protective value of intimate relationships. The Journal of Sexual Medicine 7: 3683–3694. [Crossref]

- Harvey SM, Washburn I, Oakley L, Warren J, Sanchez D (2017) Competing priorities: Partner-specific relationship characteristics and motives for condom use ang at-risk young adults. The Journal of Sex Research 54: 665–676. [Crossref]

- Katz BP, Fortenberry JD, Zimet GD, Blythe MJ, Orr DP (2000) Partner-specific relationship characteristics and condom use among young people with sexually transmitted diseases. Journal of Sex Research 37: 69–75.

- Peplau LA, Rubin Z, Hill CT (1977) Sexual intimacy in dating relationships. Journal of Social Issues 33: 86–109.

- Widman L, Welsh DP, McNulty JK, Little KC (2006) Sexual communication and contraceptive use in adolescent dating couples. Journal of Adolescent Health 39: 893–899. [Crossref]

- Gofman A, Moskowitz H (2010) Isomorphic permuted experimental designs and their application in conjoint analysis. Journal of Sensory Studies 25: 127–145.

- Green PE, Srinivasan V (1990) Conjoint analysis in marketing: New developments with implications for research and practice. The Journal of Marketing 54: 3–19.

- Kahneman D (2011) Thinking fast and slow. Macmillan.

- Dubes R, Jain AK (1980) Clustering methodologies in exploratory data analysis. Advances in Computers 19: 113–238.

- Van der Meulen E, Durisin EM, Love V (2013) Selling sex: Experience, advocacy, and research on sex workers in canada. (eds.). UBC Press.

- Kempadoo K, Doezema J (eds.), (2018) Global sex workers: Rights, resistance, and redefinition. Routledge.

- Bekteshi V, Gjermeni E, Van Hook M (2012) Modern day slavery: Sex trafficking in Albania. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 32: 480–494.

- McClain NM, Garrity SE (2011) Sex trafficking and the exploitation of adolescents. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing 40: 243–252. [Crossref]