Archives

Pre-salt Energy Genesis, Brine Streams Replenishing Oil, Gas Salt Diapirs in “Salt Mirror Petroleum Formations” – 40 Years in Retrospect, and Ancient Qanat Karez Mineral Salt Leaching Technology

Inherent Optical Properties Variability in the Bay of Bengal: A Case Study

Civil Initiative for Innovative Wastewater Management, a Case from Israel

The Reconstruction of Metabolic Pathways in Selected Bacterial and Yeast strains for the Production of Bio Ethylene from Crude Glycerol: A Mini Review

Cardiac Tamponade: An Acute and Subacute Clinical Challenge

Background

Pericardial disease resulting in a pericardial effusion is a common clinical finding with numerous etiologies identified including trauma, infection, neoplasm, autoimmune etiology, metabolic cause, or a drug-related process. Once the diagnosis of pericardial effusion has been made, it is important to determine whether the effusion is creating significant hemodynamic compromise resulting in cardiac tamponade. In addition, the timing of accumulation of the pericardial fluid significantly affects the presentation of each case. Typically, a rapid accumulation is seen in acute cases and a delayed accumulation in a subacute presentation. Distinguishing between the diagnoses of pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade is vital in order to treat a patient appropriately. We report two cases of pericardial effusion with differing etiologies, both resulting in cardiac tamponade physiology and exhibiting components of Beck’s triad. Not only did the two cases differ in etiologies, but in the length of fluid accumulation and timeframe of presentation as one presented as a rapidly accumulating pericardial effusion with acute cardiac tamponade and the other as subacute. Despite these differences, both cases were managed similarly with the creation of a pericardial window and drainage of the pericardial fluid to restore normal hemodynamics.

Case series

Case #1: An 80 year-old Caucasian male with a past medical history of a non-ischemic cardiomyopathy with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% and New York Heart Association Class III, left bundle branch block, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, abdominal aortic aneurysm, and previous cerebrovascular accident presented for routine cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator (CRT-D) placement. The left pectoral area was sterilely prepped and the left subclavian vein accessed. A defibrillator lead was fixated with a screw-in technique in the apical septal location of the right ventricle (RV); the lead was repositioned twice due to inappropriate parameters. An atrial-pacing electrode was then advanced and fixed with a similar screw-in technique in the high right atrium. Next, a coronary sinus guiding catheter was advanced into the coronary sinus and into a posterolateral branch. A left ventricle (LV) pacing lead was then advanced to the posterolateral branch; both the guidewire and the lead terminated prematurely in the lateral wall, suggesting a suboptimal position for optimal CRT. The guide catheter was then advanced into a second lateral wall vessel, and then the pacing lead was successfully placed in the mid lateral wall of the LV. All three leads tested adequately and optimized without extracardiac stimulation noted. The leads were connected to a CRT-D generator, and then the pocket was closed. Thirty minutes postoperatively, the patient’s blood pressure dropped to 92/60mmHg with a heart rate of 88bpm. The patient was in no visible distress, but mild jugular venous distention and muffled heart sounds were noted on physical exam. Stat transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) demonstrated a moderate pericardial effusion conferential to the heart, with RV diastolic collapse and respirophasic changes of less than 50% variation in the inferior vena cava, suggesting mild cardiac tamponade (Figure1).

Figure 1. Acute cardiac tamponade with a moderate pericardial effusion anterior and posterior to the heart, with partial right atrial and right ventricular collapse.

Cardiothoracic surgery took the patient directly to the operating room, and an emergent cardiac window for suspected RV perforation was completed. Although no clear perforation was seen interoperatively; 175mL of blood was evacuated with improvement in systolic blood pressure to over 150mmHg. A chest tube was placed and set to suction with an additional 500ml of blood removed over 48 hours. The patient recovered and was discharged with close cardiology follow up.

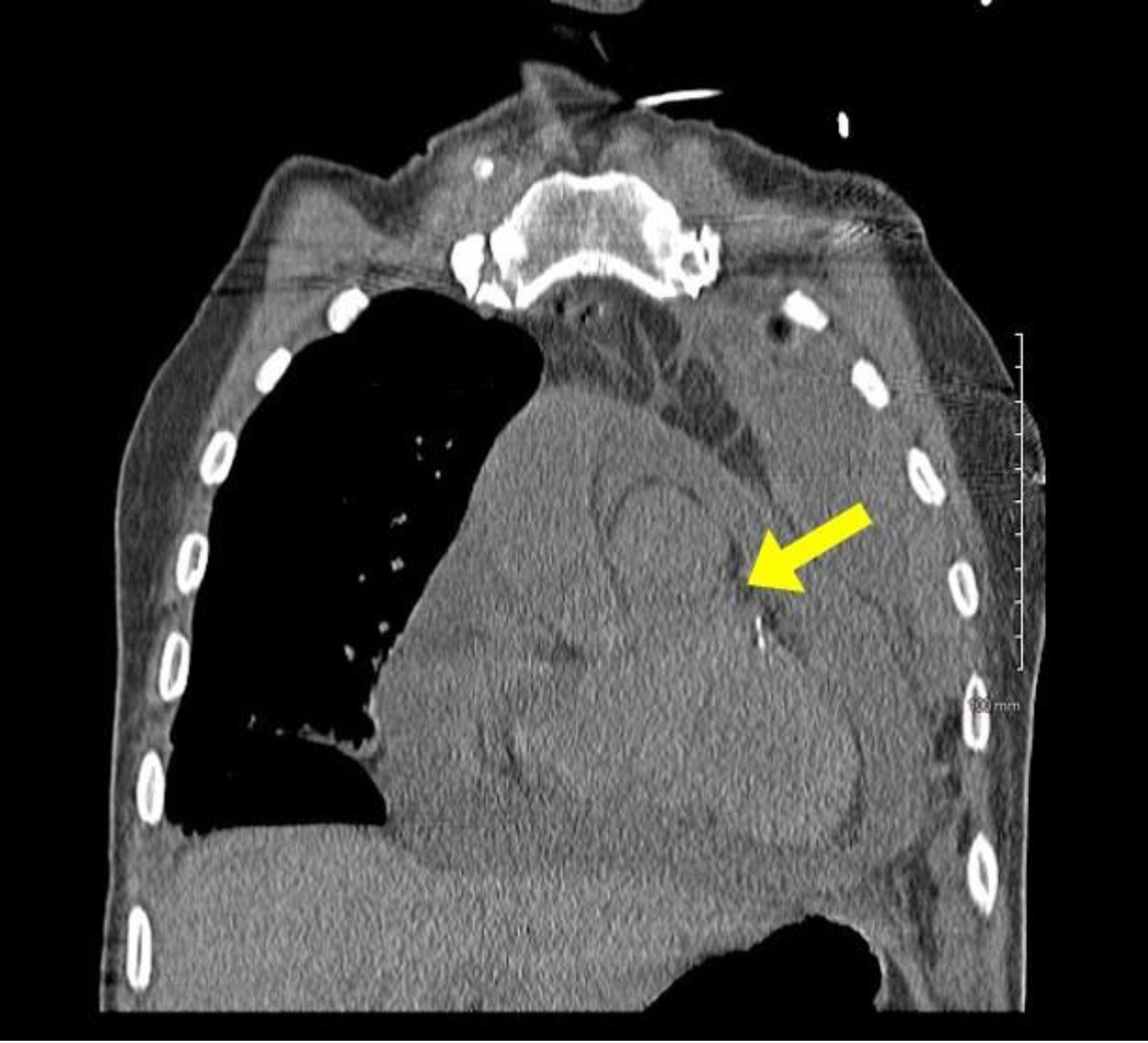

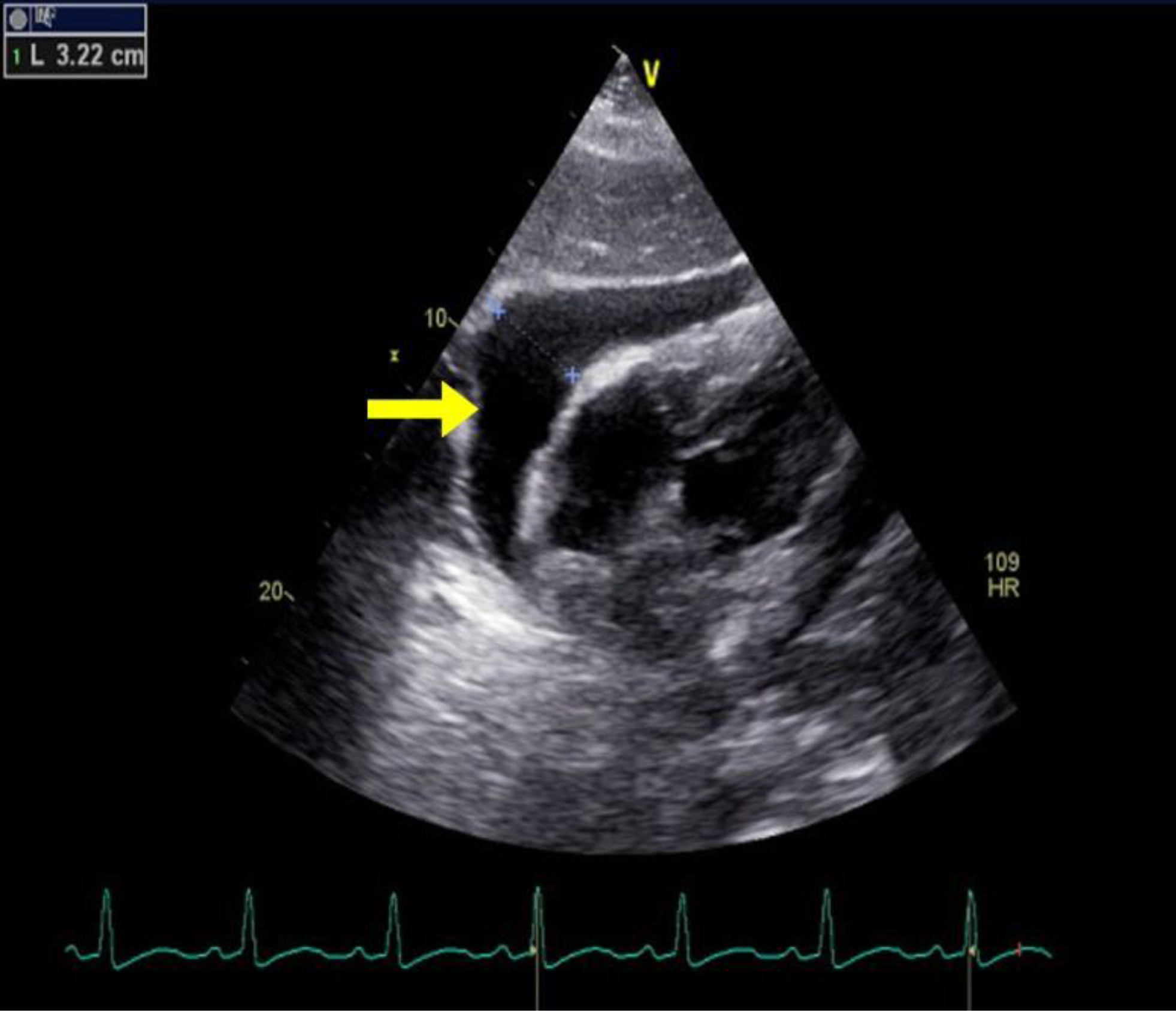

Case #2: A 66 year-old African American male with a past medical history of small cell lung cancer, COPD, tobacco use, and occupational exposure to asphalt presented with a one-day history of a new, tender right clavicular mass and worsening pleuritic chest pain and dyspnea with exertion. The patient was initially diagnosed with a small cell lung cancer in July 2018. He was initially treated with palliative chemotherapy including Etoposide and Cisplatin, and he achieved remission in October 2018. Unfortunately, he subsequently developed a recurrence in the left upper lobe in January 2019. The patient received palliative radiation until he was unable to tolerate treatments. Further mediastinal and osseous metastases were found after the chemotherapy and radiation were discontinued. Nine days prior to this presentation to the hospital, the patient underwent a therapeutic left thoracentesis due to a symptomatic, malignant pleural effusion. On primary assessment in the emergency room, the patient was found to be tachycardiac with a pulse of 121bpm and oxygen saturation of 94% breathing ambient air. The physical examination revealed a large, 7x6cm right clavicular mass extending into the neck. A cardiopulmonary exam revealed sinus tachycardia, jugular venous distention, and decreased breath sounds on the left. An EKG showed sinus tachycardia, a low voltage QRS, and no significant ischemic changes. A chest x-ray and then stat non-contrast CT neck/thorax revealed a new, large pericardial effusion and left greater than right bilateral pleural effusions (Figures 2, 3). Cardiology was consulted and a stat TTE demonstrated a large pericardial effusion, anterior and posterior to the heart, with features consistent with tamponade physiology (Figure 4).

Figure 2. Chest x-ray revealing a flask-shaped cardiac silhouette as evidenced in pericardial effusions, as well as a large, left-sided pleural effusion.

Figure 3. Stat CT chest with a coronal view demonstrating a large pericardial effusion.

Figure 4. TTE with parasternal long axis view demonstrating large pericardial effusion measuring 3.22cm.

Cardiothoracic surgery was then consulted and a therapeutic pericardial window was performed with 700cc of bloody fluid drained. In addition, a portion of the pericardium was resected and sent to pathology. Cytology revealed a malignant pericardial effusion consistent with small cell carcinoma. In addition, the patient underwent left thoracentesis and placement of a chest tube intra-operatively. He tolerated the procedures well and was transferred out of the ICU to the medical-surgical floor the day following surgery. Two days later, he underwent a right thoracentesis for a symptomatic, right-sided pleural effusion. On post-operative day 5, the patient acutely decompensated and was transferred to the ICU. Vital signs upon transfer showed a blood pressure of 67/51mmHg, heart rate of 118bpm, respiratory rate of 45, and pulse oximetry of 60%. An arterial blood gas was obtained that showed pH of 7.153, pCO2 of 54.7, pO2 of 29, and bicarbonate of 19.2. A stat EKG and TTE were obtained, with the EKG revealing atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular rate, premature ventricular or aberrantly conducted complexes, and a low voltage QRS. Bedside TTE revealed a recurrent, circumferential, small pericardial effusion without signs of tamponade or RV strain. In addition, no recurrence of left pleural effusion was identified. Due to the patient’s condition, the patient’s family made the decision to proceed with comfort measures only and further hospice care. Unfortunately, the patient passed away on post-operative day 7 due to complications related to the underlying small cell carcinoma and the associated malignant pleural and pericardial effusions.

Discussion

The presentation of cardiac tamponade depends on the timing over which the pericardial effusion accumulates. Acute cardiac tamponade occurs within minutes, and this physiology is seen in our first case. It resembles cardiogenic shock, and an emergent reduction in intrapericardial pressure (IPP) is required for treatment [1]. The second type, subacute cardiac tamponade, occurs over days to weeks. This is seen in our second case. Patients initially may be asymptomatic until the IPP reaches a critical limit, at which time symptoms such as chest pain or dyspnea ensue [1]. The pericardium is a fibroelastic sac that encases the heart and proximal great vessels [2]. It is composed visceral and fibrous parietal layers, typically containing 50ml or less of serous fluid which serves as a lubricant to reduce the friction on the epicardium [2,3]. Any processes causing this volume to exceed the typical amount, thus raising the IPP, is known as a pericardial effusion [2]. Pericardial effusions are classified based upon onset, size, location, hemodynamic changes, and composition [3]. Pericardial effusions can be loculated or circumferential and can be composed of transudative fluid, exudative fluid, pus, air, or blood [3]. Inflammatory causes can include viral, bacterial, fungal, or protozoal infections. A pericardial effusion can also be related to autoimmune disease, drug hypersensitivity, or post cardiac procedure syndromes as seen in our first case [2]. Non-inflammatory causes include hypothyroidism, trauma, or a reduction in lymphatic drainage from heart failure, cirrhosis, nephrotic syndrome, or malignancy [2] as seen in the second case.

Under normal physiologic conditions the pericardial pressures are low, and systolic and diastolic changes cause little interventricular interaction. Inspiration causes a decreased pulmonary vascular resistance, leading to an increase in venous return to the right ventricle and a small drop in the pulmonary capillary wedge and left ventricular end diastolic pressures. This leads to a decrease in systolic blood pressure of approximately 5mmHg [2]. An increase in the fluid collection in the pericardial space causes right and left ventricular pressures to increase and equalize. In addition, with the normal increasing pressure in the right ventricle with inspiration, the rigid pericardium prevents the free wall from expanding, leading to bulging of the interventricular septum into the left ventricle [2]. During inspiration in a patient with cardiac tamponade, the drop in pulmonary venous pressure leads to a drop in left atrial and pulmonary capillary wedge pressures. The left ventricular diastolic pressure remains elevated due to a leftward bowing of the interventricular septum and reduced left ventricular compliance. This exacerbates a decline in left ventricular filling pressures, and ultimately leads to a decrease in stroke volume [2].

Beck’s triad of hypotension, elevated jugular venous pressure, and muffled heart sounds are significant for severe cardiac tamponade, and components of this triad are seen on both our cases [4,5]. Patients often appear uncomfortable, with additional signs of cardiogenic shock including tachypnea, cool extremities, diaphoresis, and altered mental status [5]. Hypotension is typically present in acute tamponade, but some patients who initially present with subacute tamponade may be hypertensive on admission [5]. Tachycardia is frequent unless the patient is on a medication which may dampen this response [5]. Pulsus paradoxus is another hallmark of pericardial tamponade, defined by an inspiratory decrease in systolic blood pressure greater than 10mmHg due to a combination of a reduction in intrathoracic pressure, left ventricular stroke volume and pulse pressures [2,6,7]. A differential for these symptoms includes decompensated heart failure, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary hypertension, and a right ventricular myocardial infarction [5].

EKG abnormalities in cardiac tamponade include electrical alternans and reduced voltage, which we saw in the second case. Electrical alternans is more specific, but less sensitive, and is caused by the anterioposterior swinging of the heart during systole and diastole [5]. With larger pericardial effusions, a chest x-ray may show an enlarged cardiac silhouette with a flask-like appearance [5]. The standard non-invasive method for detecting a pericardial effusion is M-mode and two- dimensional Doppler TTE. Small pericardial effusions are typical seen over the posterobasal left ventricle, which with increasing size become circumferential [5]. These are graded in diastole as small (<10mm), moderate (10–20mm), and large (>20mm) [5,8]. Tamponade is distinguished first by early diastolic right ventricular and late diastolic or early systolic right atrial collapse when the IPP transiently exceeds the intracavitary pressures [5,8–10]. Exaggerated interventricular size variability can be appreciated throughout the cardiac cycle, with an interventricular septal bounce towards the left ventricle [8]. IVC plethora can be seen with dilation of the IVC greater than 20mm, and collapse with inspiration less than 50%, which has a 92% sensitivity for cardiac tamponade [8]. Changes in Doppler velocities across the mitral, tricuspid, right/left ventricular outflow tracks, and hepatic/pulmonary veins may add additional clues to this diagnosis [8]. A TTE provides better quality images, but is typically impractical to coordinate due to the need for urgent intervention. A CT or MRI may provide more details on loculated effusions and coexistent pleural effusions [5].

Definitive treatment of cardiac tamponade is through the reduction of IPP by removing pericardial fluid. In early cardiac tamponade where there is no hemodynamic compromise, conservative treatment with close hemodynamic monitoring and serial TTEs may be considered [11]. Acute cardiac tamponade is a medical emergency when hemodynamic compromise is present. Per the European Heart Journal 2015 guidelines [1,11], a pericardiocentesis is the treatment of choice, and the catheter is left in the pericardial space until the fluid return is less than 25ml per day [1,11]. A pericardial window is a surgical alternative requiring anesthesia, and it is used for loculated, malignant, or recurrent pericardial effusions [2,9]. An example of this procedure was seen during both of our cases. A pericardial window is also preferred if a biopsy is desired [2,9]. Intravenous hydration and rarely inotropic support or mechanical ventilation may be required depending on the clinical situation. Surgical drainage is preferred if a pericardial biopsy is needed for recurrent or loculated pleural effusions, or if a coagulopathy is present [1,11]. Pleural fluid studies can help identify the cause of the effusion. Post-operative monitoring includes telemetry for 24–48 hours, and a follow up TTE in 1–2 weeks and then in 6- 12 months [1].

Conclusion

Pericardial effusions can accumulate quickly resulting in acute cardiac tamponade, as seen in our first case, or in a subacute fashion with an insidious onset as evidenced by our second case. Beck’s triad of hypotension, elevated jugular venous pressure, and muffled heart sounds is the classic finding of acute tamponade; however, these clinical findings may not always be present. The diagnosis is typically made by physical findings and echocardiographic evidence. It is important to establish the size and hemodynamic effect of a pericardial effusion. The first line treatment for cardiac tamponade is pericardial drainage, either by pericardiocentesis or pericardial window.

Consent

Both patients provided informed consent.

Disclaimer

This research was supported (in whole or in part) by HCA and/or an HCA affiliated entity. The views expressed in this publication represent those of the author(s) do not necessarily represent the official views of HCA or any of its affiliated entities.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Hartmuth Bittner for his surgical expertise.

References

- Leimgruber P, Klopfenstein H, Wann L, Brooks H (1983) The Hemodynamic Derangement Associated with Right Ventricular Diastolic Collapse in Cardiac Tamponade: An Experimental Echocardiography Study. Circulation 68: 612–620.

- Vakamudi S, Ho N, Cremer P (2017) Pericardial Effusions: Causes, Diagnosis, and Management. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases 59: 380–388.

- Reddy P, Curtiss E, Uretsky B (1990) Spectrum of Hemodynamic Changes in Tamponade. The American Journal of Cardiology 66: 1487–1491.

- Beck C (1935) Two Cardiac Compression Triads. Journal of the American Medial Association 104(714).

- Reddy P, Curtiss E, O-Toole J, Shaver J (1978) Cardiac Tamponade: Hemodynamic Observations in Man. Circulation 58: 265.

- Hoit B (2017) Pericardial Effusion and Cardiac Tamponade in the New Millennium. Current Cardiology Reports 19(57).

- Perez-Caseres A, Cesar S, Brunet-Garcia L, Sanchez-de-Toledo (2017) Echocardiogenic Evaluation of Pericardial Effusion and Cardiac Tamponade. Frontiers in Pediatrics 5(79).

- Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, Badano L, Baron-Esquivias G, (2015) 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European Heart Journal 36: 2921–2964.

- Gilliam L, Guyer D, Gibson T, King M, Marshall J et al (1983) Hydrodynamic Compression of the Right Atrium: A New Echocardiographic Sign of Cardiac Tamponade. Circulation 68: 294–301.

- Hoit B (2019) Cardiac Tamponade. In B. C. Downey (Ed.), UpToDate. Retrieved August, 8, 2019, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/cardiac-tamponade#H3809498843.

- Zipes D, Libby P, Bonow R, Mann D, Braunwald E (2019) Braunwald’s heart disease: A textbook of cardiovascular medicine (Eleventh edition). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

Treatment of Orofacial Pain using Fascial Manipulation: a Case Report

Abstract

Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD) are the most prevalent cause of facial pain without a clear etiopathogenesis and gold standard treatment. There is not an agreement on treatments which involve surgical or conservative interventions. Between the different types of conservative treatments the Fascial Manipulation® could be a promising therapy. Here we describe the case of a patient with orofacial pain that was treated successful with three single sessions of Fascial Manipulation®.

Keywords

TMJ, Fascial Manipulation®, Orofacial pain.

Introduction

Orofacial pain is a heterogeneous group of musculoskeletal and neuromuscular conditions involving the temporomandibular joint complex, surrounding musculature and osseous components [1]. Between these, Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD) are the most prevalent cause of orofacial pain. TMD are highly prevalent and debilitating conditions involving the head and face, with pain affecting the jaw, ears, eyes and frequently causing headache and neck pain [2]. The etiology of chronic TMD is multifactorial and include structural, functional, environmental, social and psychological factors [3]. The prevalence of orofacial pain is between 3% and 12% and is, at least, twice as prevalent in women as men [4]. Musculoskeletal structures disorders include myalgia, usually presents as a dull aching pain due to continued muscle tension, Myofascial Pain (MFP) also presents as a dull, continuous aching pain that varies in intensity. MFP produces pain upon palpation that is local and may refer to other sites, as mapped out by Simons [5]. MFP tends to be seen in muscle pain conditions of a more chronic nature, in which the tension is unremitting. Trigger points can often be seen in MFP and may be localized to a taut band of muscle.

In the literature, treatments for TMD include patient education, home care programs, physical therapy, musculoskeletal manual approach, pharmacotherapy, Non Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), local anesthetics, intracapsular injection of corticosteroids, muscle relaxants, antidepressants, occlusal appliance therapy, occlusal adjustment. Surgical care is only indicated when non-surgical therapy has been ineffective [6]. However, the multifactorial pathophysiology of TMJ related pain is far from being completely understood and effective management of pain has not been established yet [7]. Unfortunately, despite the evidence of two systematic reviews that support manual therapy to produce favorable outcomes in TMD [8, 9] the real effectiveness of different types of manual therapy in TMD remains unclear. A manual therapy named Fascial Manipulation® is shown in a preliminary study to be effective in improving tmj disorder when compared to botulin toxin [10]. Here we present to case of a patient with chronic tmd disorder treated successfully treated with Fascial Manipulation.

Case report

A 65 years old woman, mixed race, Brazilian was assessed and treated at the TMD clinic of the Faculty of Dentistry, State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ). She complained of orofacial pain and difficulties chewing and eating for the last 25 months, with concomitant neck pain and an history of headache lasting more than 5 years. She referred a history of whiplash following a car accident that occurred 7 years ago.

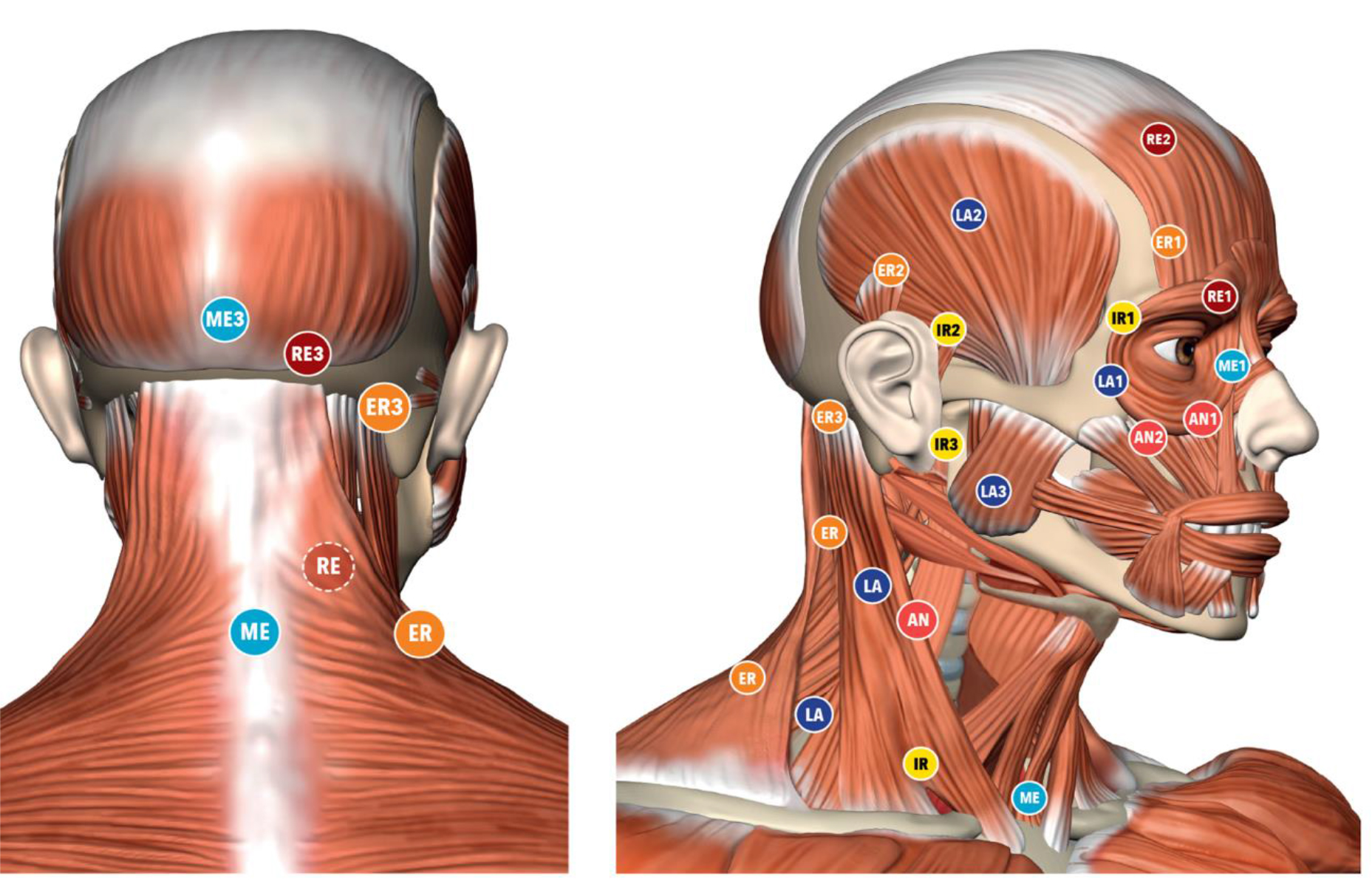

The patient has undergone many months of physical therapy without significative improvement and she has been using an Oral Appliances (OAs) (also known as flat plane stabilization appliance, Michigan splint, muscle relaxation appliance or gnathologic splint) for the last 6 months. Pain was described as constant, burning sensation severe enough to affect sleeping. Perceived pain was assessed with the Visual Analogue Scale (Vas) and scored as 9 on a 0–10 scale (Table 1) The RDC/TMD was utilized as the gold-standard instrument and performed by a sole examiner, trained and calibrated according to specifications established by the International RDC/TMD Consortium. At the initial examination it was recorded the occurrence of TMJ clicking, crepitus, or jaw opening interferences with or without pain. The clinician viewed the patient’s opening and closing patterns to note any mandibular deviations. The evaluation of mandibular ROM consisted of measuring comfort opening, unassisted opening, assisted opening, with a millimeter ruler while noting the severity and location of pain with jaw movement (Table 2) The EMG evaluation of the temporalis and masseter muscles during maximum voluntary contraction (tooth clenching) were carried out using the New miotool (MiotecEquipamentosbiomédicosltda, Petrópolis, Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil) with 14-bit resolution and a sampling frequency of 2000 Hz, IRMC > 126 dB and signal noise rate < 2 LSB, Security insulation 3000 V(rms) (table 3). All procedures were performed three times, with a thirty seconds interval between isometric contractions to avoid muscle fatigue. After electromyography signal acquisition, all the data were processed in Miotec Suite (MiotecEquipamentosbiomédicosltda, Petrópolis, Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil) to analyse the root square mean (RMS) in µV. All the evalution were carried out before the Treatment (T0), after the treatment (T1) and at 3 months follow up (T2). On physical examination the range of motion of the neck (ROM) was limited in the sagittal plane (neck flexion) and on the frontal plane (lateral flexion). The palpatory verification of the CC and CF was carried out according to the Stecco’s method (reference) on the following segments: thorax (TH), Scapula (SC), Neck (CL), Head (CP2, CP3) to identify the densified points (Figure 1). The points are selected after a specific assessment process, guided by a specific chart (FM chart) [11] involving medical record, clinical examination of specific movements and palpatory verifications. Palpation evaluates patient pain rate, radiation and most important, the presence of tissue stiffness, call “densification” [12]. During the clinical history, the segments in dysfunction are identified with an emphasis on the chronology to permit the development of an hypothesis based on the current symptomatology of patients and previous musculoskeletal events, which may be causing compensations. In Fascial manipulation the therapist use the elbow and knuckles generating a deep friction for 3–5 minutes over each point.

Figure 1. Location of the Center of Coordination points

The treatment are applied over specific points, call Center of Coordination (CCs) and Center of Fusion (CFs), that are anatomically safe because do not overlie major superficial nerves and veins. Additional guidance for point selection includes avoiding the patients’ excessively painful areas where inflammation, lesions or even fractures could be present. The patient underwent three weekly session of Fascial Manipulation® of 1 hour. The VAS scale, between initial condition (T0) and after the treatment (T1) was maintained at 3 month follow up (T2) (Table 1). The patients passed from the symptomatic condition (VAS 9) to asymptomatic (VAS 1) after the treatment. The comfortable without pain opening of the mounts improved (Table 2). Un-assistant and assistant opening improved after treatment, at T1 and T2 follow up. In the table 3 are presented the value of the isometric contraction which improved for the masseter and temporalis muscles bilaterally.

Table 1. VAS T0 = VAS before treatment; T1 = VAS after treatment; T2 = VRS after 3 months

|

|

VAS |

|

T0 |

136.56 |

|

T1 |

264.60 |

Discussion

In the light of our case report, Fascial Manipulation® can improve pain, function and myoelectrical activity in patient with orofacial pain. FM was able to diminish the articular loading on the TMJ which translate in a better mandibular kinematics with less muscle pain. Even if FM share some similarity with other techniques, it presents a different rationality and clinical approach. While the deep friction can be compared to other techniques, the reasoning behind the choice of points treated presents major differences. The points are selected after a specific assessment process involving clinical history taking, a clinical examination of specific movements as well as palpatory verifications [12, 11]. Apart from the use of clinical procedures (palpation, auscultation, measuring of active and passive mandibular mobility), FM requires additional orthopedic tests that implies a modern, biomedical approach, thanks to the knowledge of the human fascial system, but, at the same time, uses an individual approach to the patient as recommended by many Authors [13–15].

Table 2. Assisted: maximum opening with help, unassisted: maximum opening without help. T0 = before treatment; T1 = after treatment; T2 = 3 months;

|

|

Comfortable |

Unassisted opening |

Assisted opening |

|

T0 |

32,51 |

45,30 |

49,23 |

|

T1 |

42,33 |

51,14 |

54,08 |

|

T2 |

40.1 |

48,18 |

50,75 |

Table 3. EMG evaluations of the masticatory muscles in isometric contraction T0= before treatment; T1= after treatment; T2= 3 months

|

|

Right |

Left Masseter |

Right Temporal |

Left |

|

T0 |

136.56 |

176.27 |

154.45 |

127.50 |

|

T1 |

264.60 |

260.75 |

221.47 |

159.61 |

|

T2 |

411.61 |

427.30 |

279.65 |

215.82 |

Conclusion

FM could be used as an effective method for facial pain being a rapid, safe and cost effective approach to reduce pain and gain function and mouth opening that can be used before occlusion stabilization appliance. We suggest further studies that compare the combined treatment of FM with temporomandibular disorder treatment in patient with TMD in a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT).

References

- McNeill C (1993) Temporomandibular Disorders: Guidelines for Classification, Assesment, and Management (2nded.). Chicago, IL: QuintessencePublishingCo, Inc.

- Germain L, Malcmacher L (2017) Frontline Temporomandibular Joint/Orofacial Pain Therapy for Every Dental Practice. Compend Contin Educ Dent 38: 299–305. [crossref]

- Fillingim RB, Ohrbach R, Greenspan JD, Knott C, Diatchenko L et al. (2013) Psychological factors associated with development of TMD: the OPPERA prospective cohort study. J Pain 14: T75–T90. [crosssref]

- Okeson JP (2005) Bell’s Orofacial Pains. The Clinical Management of Orofacial Pain (6th ed.). Carol Stream, IL: Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc.

- Simons DG, Travell JG (1999) Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual. Vol 1. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

- Romero-Reyes M, Uyanik JM (2014) Orofacial pain management: current perspectives. J Pain Res 7: 99–115. [crossref]

- Lin CS (2014) Brain signature of chronic orofacial pain: a systematic review and metaanalysis on neuroimaging research of trigeminal neuropathic pain and temporomandibular joint disorders. PloS One 9: e94300. [crossref]

- McNeely ML, Armijo Olivo S, Magee DJ (2006) A systematic review of the effectiveness of physical therapy interventions for temporomandibular disorders. Phys Ther 86: 710–725. [crossref]

- Medlicott MS, Harris SR (2006) A systematic review of the effectiveness of exercise, manual therapy, electrotherapy, relaxation training, and biofeedback in the management of temporomandibular disorder. Phys Ther 86: 955–973. [crossref]

- Guarda-Nardini L, stecco A, Stecco C, Masiero S, Manfredini D (2012) Myofascial Pain of Jaw Muscles: Comparison of Short-Term Effectiveness of Botulinum Toxin Injections and Fascial manipulation technique. The Journal of Craniomandibular Practice 30: 95–102. [crossref]

- Pintucci M, Simis M, Imamura M, Pratelli E, Stecco A et al. (2017) Successful treatment of rotator cuff tear using Fascial Manipulation® in a stroke patient. Journal of Bodywork & Movement Therapies 21 653–657. [crossref]

- Day JA, Copetti L, Rucli G (2012) From clinical experience to a model for the human fascial system. J Bodyw Mov Ther 16: 372–80.

- Kordaß B, Fasold A (2012) ManuelleStrukturanalyse. Teil 1: Grundlagen und klinischeUntersuchung. ZWR 212: 8–11.

- Badel T, Krapac L, Kraljević A (2012) The role of physical therapy in patients with temporomandibular joint disorder. FizRehabil Med 24: 21–33.

- Hoffmann RG, Kotchen JM, Kotchen TA, Cowley T, Dasgupta M et al. (2011) Temporomandibular disorders and associated clinical comorbidities. Clin J Pain 27: 268–274.

- Schulze W. Therapeutic communication with CMD patients – Part 2. J Craniomandib Funct 2010; 2: 149–60.

Management of Diabetes Patients across the Peri- Operative Pathway: A Systematic Review

Abstract

Peri-operative environments are a hazardous setting for diabetes patients. A systematic review of literature regarding the management of diabetes patients across the peri-operative pathway has been undertaken to assess if the management of patients within this pathway is suitable and effective for patients.

Methods

A database search of Google Scholar, CINAHAL, Embase, OVID, Cochrane Library, Joanna Briggs institute and PUBMED was undertaken from 15th of March 2019 to 30th of March 2019. A total of 57 papers were found and reduced down to 11 final papers that answered the review question and met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria were: Full text, English language, human subjects, adult patients only and studies that focused on diabetes care in a section of the peri-operative pathway. Exclusion criteria: children or adults and children, studies that looked a one particular intervention or type of surgery. No date limit was set. PICO tool was used to frame the study question.

Results

Three main themes emerged from the literature. 1. Poor patient outcomes; 2. Longer length of stay (LOS); 3. Lack of adherence to guidance and or protocols and glycaemic control. Elective patients had advantageous outcomes compared to emergency surgical patients. Hyperglycaemia still remained a problem with an increase in other medical complications for diabetes patients. LOS in hospital was found to have increased due to medical complications. Adherence to protocols and guidance was found to be beneficial in monitoring and managing hyperglycaemia. However, this review found that best practice guidance and hospital protocol is not always adhered to. A liberal approach to glycaemic control is beneficial.

Conclusion

This systematic review investigated the management of diabetes patients across the peri-operative pathway. Three main themes emerged from the literature: poor patient outcomes; length of stay; and lack of adherence to guidance and or protocols and glycaemic control. We concluded the peri-operative environment is a hazardous setting for a diabetes patients. Elective patients had slightly more advantageous outcomes than emergency patients. Hyperglycaemia still remains a problem which leads to poor patient outcomes and longer LOS. Adherence to protocols and guidance was found to be beneficial in monitoring and managing hyperglycaemia.

Introduction

The Department of Health and Social Care (DOH) (2001) state that diabetes patients undergoing surgery carry a greater clinical risk than non-diabetes patients. This is due a number of complex factors such as reduced food intake due to a starvation period, and cessation of normal diabetes medications [1]. In addition, the body’s stress response and inhibition of insulin secretion increases the potential for hyperglycaemia [2]. The Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland [3] state that diabetes affects 10–15% of the surgical population, with these patients carrying a greater risk of complication rates, mortality rates and Length of stay (LOS).

Despite these findings, there is very little guidance and research surrounding diabetes management across the peri-operative pathway. There are currently no standardised worldwide guidelines for use by theatre or PACU practitioners [4] and globally, diabetes management during the peri-operative period is widely debated [5]. The aim of this systematic review was to investigate the management of diabetes patients across the peri-operative pathway.

Methodology

A systematic and comprehensive search of databases was carried out between the 15th of March 2019 and the 30th of July 2019. The search involved Google Scholar, CINAHAL, Embase, OVID, Cochrane Library, Joanna Briggs institute and PUBMED. Combinations of key words were inputted into each database. Further restrictions were then applied to reduce the number of papers, such as; English language, full text and used adult human patients as the participants. Studies which examined the care and management of diabetes patients across the peri-operative pathway were included. Studies into specific interventions or surgeries were excluded due to the broadness of the review question. Exclusion criteria: children participants and studies that looked a one particular intervention or type of surgery. No date limit was set.

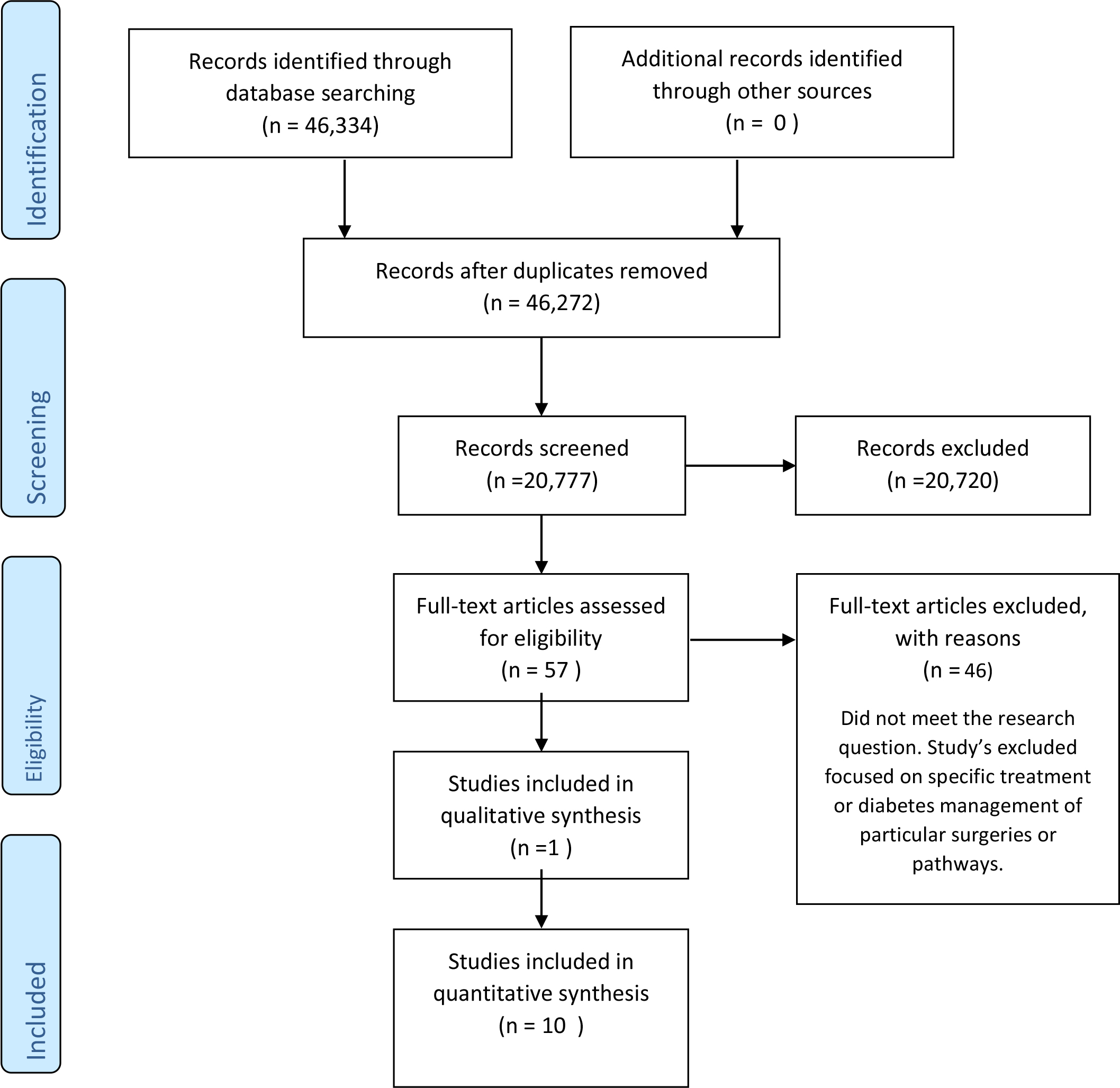

This review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to ensure systematic transparency of report [6]. After duplications were removed, 57 papers were read to determine their relevance to the review question.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram of Studies included in quantitative synthesis

The Cauldwell, Henshaw and Taylor (2011) framework was utilised for assessing the meaningfulness or generalisability of qualitative and quantitative research in contemporary nursing practice, which enabled a structured approach to the assessment of each study’s quality, validity and reliability (Clarke, 2011). The final 11 papers were RAG (red amber green) rated [7] to reflect the answer to each of the questions from the tool. Dates ranged from 1983- 2019 and included studies from various countries. 9 of the 11 studies focused on the peri-operative period. 1 study focused on intra-operative and post-operative diabetes management. 1 study looks at diabetes management in the pre-operative period. Full text was then read to extract the results from each paper for the formation of themes.

Results and discussion

A systematic review as undertaken to establish the management of diabetes patients across the peri-operative pathway. Three key themes emerged from the review: poor patient outcomes, length of stay (LOS) which were commonly reported jointly and adherence to guidance and or protocols and standards for glycaemic control.

Poor patient outcomes

8 out of 11 studies reported on the outcomes of patients with diabetes. Studies 2, 3,5,6,8,9,10 and 11 discussed surgical outcomes directly related to diabetes management. McCavert, Monem and Dooher, et al [8] found that best practice of glycaemic control, in-line with hospital protocols, saw a 25.4% reduction of peri-operative complications. Overall complications being 29% (out of 69 patients). Elective patients with T2DM were more prone to complications. 5 out of 17 (29.4%) of T2DM elective patients experienced complications; in contrast, only 4 out of 21 (19.0%) of elective patients with T1DM developed a complication such as wound infection or peritonitis. For emergency patients, the rate of complications was slightly higher for those with T1DM (5 out of 14; 35.7%) versus 6 out of 17 patients (35.3%) with T2DM. Complications such as; Wound dehiscence, septicaemia, wound infection, wound infection, confusion, deep vein thrombosis and lower respiratory tract infection were reported as a complication. Frisch, Chandra, Smiley, et al [9] similarly analysed outcomes of mobility contrasting both diabetes and non-diabetes patients. Outcomes such as pneumonia (12.1 vs 5.4%; p=0.001), wound and skin infections (5 vs 2.3%; p<0.001), systematic blood infection (3.6 vs 1.1%; p<0.001), urinary tract infections (4.5vs 1.4%, p<0.001) acute myocardial infarction (2.6 vs 1.2 %; p< 0.001) were reported. Patients who experienced complications had a strong affiliation with high blood glucose levels pre and post-operatively.

“Haemoglobin A1c, often abbreviated as A1C, is a form of haemoglobin (a blood pigment that carries oxygen) that is bound to glucose” [10]. Underwood, Askari, Hurwitz et al [11] linked to various A1C categories to patient outcomes. It showed that, like McCavert et al and Frisch et al, [8, 9] diabetes patients (specifically group A1C ≤6.5%) had a higher incidence of LOS, acute renal failure death within 30 days and wound class (dirty). Groups ≤6.5%, A1C> 8-10% and A1C > 10% was significantly longer compared with the control subjects (p<0.001,p<0.008, and p=0.002, respectively).

Wang, Chen, Li, et al (2019) found that patients over 65-years old, male, high mean post-operative blood glucose (BG), diabetes complications, abnormal kidney function and have underwent general surgery were the highest risk category for poor patient outcomes. The study compared surgery type and patient outcomes. Of the 301 (19.8%) of all patients with diabetes complications, 295, (98.0%) had major vascular complications, 8 (27. %) had diabetes nephropathy, 3 (0.7%) had diabetes retinopathy, 5 (1.7%) had diabetes foot post-operatively. Post-operative adverse events occurred in 118 (7.7%) including 43 (36.4%) delayed extubation caused by surgery-related respiratory failure or muscle weakness. 15 (12.7%) patients had circulatory disorders, 23 (19.5%) had respiratory and circulatory abnormalities. 11 (9.3%) had non-healing of the incision. 15 (12.7%) had infections at other sites. 8 (6.8%) patients with other complications. 3 (2.5%) patients died due to pulmonary embolism and two cases of septic shock. Kotgal, Symods, Hirsch, lrl, et al [12] did not correlate BG management with patient outcomes, but results showed that patients had a greater chance of poorer outcomes with any level of hyperglycaemia versus those who had better diabetes control.

In contrast, Sathya, Davis, Taveria, et al [13] found that stroke, atrial fibrillation and wound infection were the most significant complications from pooled results of 6 studies. Mixed results were noted; 2 pooled results found that the incidence of post-operative stroke was reduced by liberal glycaemic regimes, but pooled results from a further 3 studies suggested that there was no significant difference between the effect of moderate vs strict control on stroke outcomes (odds ratio, 18.5, 95% CI 0.72-4.74, p=0.020). Sathya et al [13] also examined the relationship between atrial fibrillation as a patient outcome and diabetes control. Again, pooled estimates from 2 pooled studies found that moderate versus liberal control had no direct effect on atrial fibrillation as an outcome (Odds ratio 0.54, 95% CI 0.17-1.76, p =0.31). In addition, pooled results from 3 other studies found that there was no significant difference between strict versus moderate control in relation to atrial fibrillation (odds ratio: 0.71, 95% CI0.39-1.30, p=0.27). Wound infection was also not found to have a significant link to the effects of moderate versus glycaemic control from the results of 2 pooled studies.

Length of stay

LOS was a significant finding in studies 2, 3, 6 and 8. Although not a complication in itself, LOS was linked to or reported alongside poor patient outcomes.

McCavert et al [8] found that Emergency patients had a significantly longer LOS in hospital than the elective groups. Frisch et al (2010) [9] also reports that diabetes patients had a higher rate of complications than non-diabetes counterparts (p=0.105). Patients with diabetes were found to have a greater LOS (and LOS in ICU) than non- diabetes patients. It was also noted that African American patients were not at an increased risk of mortality than other races. No other study compared likelihood of surgical outcomes and race.

Patients with diabetes were also more likely to have greater complications including LOS. Underwood et al, 2014 [11] however, reported that patients with A1C levels >6.5-8% had a similar LOS to the control group. Patients with higher A1C ≤6.5 up to greater than 10% had a significantly longer LOS compared to control subjects. This was the most significant difference of the various A1C groups compared in the study. Higher A1C level was more significant than any other variable such as a diabetes patient’s race, gender or type of surgery in relation to LOS. Longer LOS in the hospital was found by Hommel et al [14] to be associated with higher dissatisfaction of patients regarding patient centred-ness in their assessment of results.

Lack of adherence to guidance and or protocols and glycaemic control

The third key theme that emerged from the literature was adherence to guidance, such as hospital protocols and national guidelines and glycaemic control. This theme was disused in studies 1,2,5,7 and 10.

McCavert et al [8] studied both elective and emergency surgical patients. 60% of elective patients with T1DM were not treated according to hospital protocol. Elective patients who were treated according to protocol had a complication rate of 6.3 %. For emergency surgical patients, 7.3% of T1DM patients who were treated as per protocol developed a complication. 12.3% of scheduled blood glucose measurement were not completed. 11.1% of T1DM elective patients did not have their blood glucose checked, and 6.8% of emergency T1DM patients. For T2DM, blood glucose was not checked in 17.4% of elective patients and 12.7% in emergency cases.

Similarly, Coan, Schlinkert, Brandon et al [15] note that capillary BG was taken in 89% of cases in the pre-operative area, and only52% of patients had a HBA1C. Intra-operatively, 33% of patients had a BG check, and the post- operative figure was 87%. 90% of pre-operative BG was point of care (POC), and 4% was venous sampling. Intraoperatively, 10% of patients had POC BG values, 16% had POC blood gas sampling. In the PACU, 86% of BG were obtained by POC and 1% was venous. Similarly, Jackson, Patvardhan et al (2015) reported that only 71% of patients had a HBA1C recorded pre-operatively and 56% intra-operatively via CBG. 73% of patients had a CBG performed in recovery (PACU) contrary to national guidance. Hommel, Van Gurp, Tack et al’s [16] quality indicators suggest that best-practice involved measuring BG 4 hours pre-operatively, every 2 hours intra-operatively, and 1 hour post-operatively. Hommel et al [14] reported that in relation to patient satisfaction and person centeredness, 20% of 362 patients were not informed about intra-operative BG level and its effect. 15% were also not informed that insulin was administered during surgery. This correlated to overall low score from patients’ involvement in the survey. Sathya et al [13] report that patients undergoing a liberal target for glycaemic control had significantly better post-operative outcomes (less or no complications) than other groups. No difference with wound infection or atrial fibrillation were found. Bibble (1983) commented from the 3 case studies that protocols for glycaemic control were directed towards managing ‘average’ diabetes patients rather than complex ones, making guidance non-beneficial.

Future recommendations would be to undertake extensive quantitative and qualitative research across the peri-operative pathway with staff who have direct responsibility for diabetes patients undergoing surgery. The views and attitudes of staff members regarding diabetes management may shed light on the barriers as to why this is still a problem despite being highlighted by several studies seen in this review since 1983. Any further research conducted needs to be influential on practice in order to drive change.

Conclusion

This systematic review examined the management of diabetes patients across the peri-operative pathway. Three main themes emerged: poor patient outcomes; longer length of stay; and lack of adherence to guidance and or protocols and glycaemic control. We concluded the peri-operative environment can be a hazardous setting for diabetes patients. Elective patients had slightly more advantageous outcomes than emergency patients. Hyperglycaemia still remains a problem which leads to poor patient outcomes and longer LOS. Adherence to protocols and guidance was found to be beneficial in monitoring and managing hyperglycaemia.

Table 1. Characteristics of studies

References

- McAnulty GR, Robertshaw HJ, Hall GM (2000) Anaesthetic Management of patients with diabetes mellitus. British Journal of Anaesthesia 85: 80-90.

- Dagogo-Jack S, Alberti KGMM (2002) Management of Diabetes Mellitus in Surgical Patients. Diabetes Spectrum 15: 44-48 [online].

- Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. (2015) Peri-operative management of the surgical patient with diabetes 2015. Anaesthesia 70: 1427-1440.

- Coan KE, Apsey HA, Schlinkert RT, Stearns, JD Cook, CB (2014) Managing diabetes mellitus in the surgical patient. Diabetes management 4: 515-526.

- Duggan EW, Carlson K, Umpierrez GE (2017) Perioperative Hyperglycaemia management: an update. Anesthesiology 126: 547-560.

- Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, et al. (2015) Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 4: 1.

- Webster V, Webster M (2019) How to Use RAG Status Ratings to Track Project Performance. [online]. Available at: https://www.leadershipthoughts.com/rag-status-definition/ (Accessed 12 June 2019).

- McCavert M, Mone F, Dooher M, Brown R, O’Donnell ME (2010) Peri-operative blood glucose management in general surgery-a potential element for improved diabetes patient outcomes- An observational cohort study. International Journal of Surgery 8: 494-498.

- Frisch A, Chandra P, Smiley D, Peng L, Rizzo M, (2010) Prevalence and clinical outcome of hyperglycaemia in the peri-operative period in noncardiac surgery. Diabetes care 33: 1783-1788.

- Stöppler MC (2019) Shiel WC (eds.) Haemoglobin A1c Test (HbA1c) [online]. Available at: https://www.emedicinehealth.com/hemoglobin_a1c_hba1c/article_em.htm#facts_and_definition_of_hemoglobin_a1c_hba1c (Accessed 19 June 2019).

- Underwod P, Askari R, Hurwitz S, Chamarthi B, Garg R (2014) Preoperative A1C and clinical outcomes in patients with diabetes undergoing major noncardiac surgical procedures. Diabetes care 37: 611-616.

- Kotagal M, Symons RG, Hirsch IB, Umpierrez GE, Dellinger EP, et al. (2015) Perioperative hyperglycaemia and risk of adverse events among patients with and without diabetes. Annals of surgery 261: 97-103.

- Sathya B, Davis R, Taveria T, Whitlach H, WU WC (2013) Intensity of peri-operative glycaemic control and postoperative outcomes in patients with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes research and clinical practice 102: 8-15.

- Hommel I, Van Gurp PJ, Tack CJ, Lifers J, Mulder J, et al. (2014) Peri-operative diabetes care: room for improving the person centredness. Diabetes Medicine 32: 561-568.

- Coan KE, Schlinkert AB, Beck BR, Haakinson DJ, Castro JC, et al (2013) Perioperative management of patients with diabetes undergoing ambulatory elective surgery. Journal of diabetes science and technology 7: 983-989.

- Hommel I, Van Gurp PJ, Tack CJ, Wollersheim H, Hulscher MEJL (2015) Perioperative diabetes care: development and validation of quality indicators throughout the entire hospital care pathway. British Medical Journal BMJ 25: 525-534.

- Coan, K.E., Schlinkert , A.B., Beck, B.R., Haakinson, D.J ., Castro, J.C., Schlinkert, R.T., Cook, C.B (2013) Perioperative management of patients with diabetes undergoing ambulatory elective surgery. Journal of diabetes science and technology. 7 (4) pp: 983-989.

- Department of Health and Social Care (2008) National service framework for diabetes [online]. Accessed: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-service-framework-diabetes [Accessed 15 March 2019].

- Diabetes UK (2010) Key statistics on diabetes. Available at: https://www.diabetes.org.uk/resources-s3/2017-11/diabetes_in_the_uk_2010.pdf (Accessed 15 March 2019).

- Diabetes UK (2018) Diabetes Prevalence 2018. Available at: https://www.diabetes.org.uk/professionals/position-statements-reports/statistics/diabetes-prevalence-2018 (Accessed 29 May 2019).

- Diabetes.co.uk (2019) ISO Standards for Blood Glucose Meters [online]. Available at: https://www.diabetes.co.uk/blood-glucose-meters/iso-accuracy-standards.html (Accessed 19 June 2019).

- Gandhi, G.Y., Nutthall, G.A ., Mullany C.J., Schaff H.V., Williams B.A .,Schrader L.M., Rizza R.A and McMahon M.M (2005) Intraoperative hyperglycaemia and peri-operative outcomes in cardiac surgery patients. Mayo clinic. Proc. 80 (7) pp: 862-866.

- Godby, M.E (2019) Control Group Science. [online]. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/science/control-group (Accessed 08.06.2019).

- Gov.uk (2019) Ethnicity facts and figures: UK population by ethnicity. [online]. Available at: https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/uk-population-by-ethnicity (Accessed: 04.06.2019).

- Herman, W.H (2010) Are there clinical implications of racial differences in HbA1c? Yes, to not consider can do great harm! Diabetes Care. 2016; (39) pp: 1458–146 [online]. Available at: http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/diacare/39/8/1458.full.pdf (Accessed 11 June 2019).

- Kang, H (2013) The prevention and handling of the missing data. Korean Journal of Anesthesiology. 64(5)pp: 402–406. [online]. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3668100/ (Accessed 19 June 2019).

- Kendall, J.M (2018) Designing a research project: randomised controlled trials and their principles. Emergency Medicine Journal. 20 (0) pp: 164-168. [online]. Available at: https://emj.bmj.com/content/20/2/164.info (Accessed 19 June 2019).

- Kumar PR ., Bhansali A., Ravikiran M., Bhansali , S., Dutta., Thakur, J.C., Sachdeva, N., Bahdada, S.K and Walia, R (2010)Utility of glycated hemoglobin in diagnosing type 2 diabetes mellitus: a community-based study. Journal of endocrinology and metabolism. 95 pp: 2832–2835.

- Leung, V and Ragbir-toolsie (2017) Perioperative management of patients with diabetes. Health serv insights .:2017 10. [online]. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5692120/ (Accessed 29 May 2019).

- Moher, D, Liberati, A.,Tetzlaff J and Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Medicine.6:(7). [online]. Available at: http://prisma-statement.org/PRISMAStatement/FlowDiagram.aspx (Accessed 20.03.2019).

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney diseases (2019) Diabetes overview : what is Diabetes? [online]. Available at:https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview/what-is-diabetes (Accessed 08 June 2019).

- National Health Service NHS (2016) Diabetes [online]. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/diabetes (Accessed 15 March 2019).

- National Health Service NHS (2017) Next steps on the five-year forward view [online]. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/NEXT-STEPS-ON-THE-NHS-FIVE-YEAR-FORWARD-VIEW.pdf (Accessed 15 March 2019).

- New York University NYU libraries (2019) Health (Nursing, Medicine, Allied Health): Search Strategies: Framing the question (PICO) Guide to locating health evidence. [online]. Available at: https://guides.nyu.edu/c.php?g=276561&p=1847897 (Accessed 15 June 2019).

- Pal Singh, A (2015) Bone and Spine : What is Hierarchy of Evidence? [online]. Available at : https://boneandspine.com/what-is-hierarchy-of-evidence/ (Accessed 01 July 2019).

- Pimentel M.P.T., Choi, S ., Fiumara, K., Kachalia, A and Urman, R.D (2017) Safety Culture in the Operating Room: Variability Among Perioperative Healthcare Workers. Journal of patient safety. [online]. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28574955 (Accessed 12 May 2019).

- Preston, N. Gregory, M (2012) Patient recovery and post-anaesthesia care unit (PACU). Anaesthesia and intensive care medicine. 13: (12) pp: 591–593. [online]. Available at: https://www.anaesthesiajournal.co.uk/article/S1472-0299(12)00234-2/fulltext [Acessed:15.03.2019].

- Public health England press release (2016) 3.8 million people in England now have diabetes. [online]. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/38-million-people-in-england-now-have-diabetes (Accessed 15 March 2019).

- Quesada, I ., Tudurı´,E ., Ripoll, C and Nadal, A (2008) Physiology of the pancreatic a-cell and glucagon secretion: role in glucose homeostasis and diabetes. Journal of Endocrinology. (199) pp: 5–19 [online]. Available at: https://joe.bioscientifica.com/view/journals/joe/199/1/5.xml (Accessed 08 June 2019).

- Royal College of Nursing RCN (2019) Peri-operative Care. [online]. Available at: https://www.rcn.org.uk/library/subject-guides/perioperative-care (Accessed 08 June 2019).

- Sargis, R.M (2015) An Overview of the Pancreas: Understanding Insulin and Diabetes. [online]. Available at: https://www.endocrineweb.com/endocrinology/overview-pancreas (Accessed 12 June 2019).

- Shuttleworth, M and Wilson, L.T (2019) Scientific Control Group. [online]. Available at: https://explorable.com/scientific-control-group (Accessed 26 June 2019).

- Smiley, DD,. Umpierrez, GE. (2006) Perioperative glucose control in the diabetes or nondiabetes patient. South Med J. 99 (6) pp: 580-9; quiz 590-1. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16800413 (Accessed 15 March 2019).

- Swenne, C.L and Alexandrén, K (2012) surgical team members’ compliance and knowledge of basic hand hygiene. Journal of infection and prevention control. 2 (3) pp: 114-119. [online]. Available at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/cd6d/e40147cef4e4010ddb1912fb8c3f3fd00345.pdf (Accessed 12 June 2019).

- World Health Organisation WHO (2018) Diabetes. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes (Accessed 29 May 2019).

- Ziemer, DC,., Kolm. P., Weintraub W.S., Vaccarino. V., Rhee, M.K., Twombly, J.G., Narayan, K.M., Koch, D.D and Philips, L.S (2010) Glucose-independent, black-white differences in hemoglobin A1c levels: a cross-sectional analysis of 2 studies. Ann Intern Med. 152 pp:770–777 [online]. Avalible at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20547905 (Accessed : 04 June 2019)

A LIFE IN UROLOGY: Privilege, Obligation and Reward

Abstract

A life of an urologist, who thrived in academia after early postgraduate training in the US, was presented. Through this somewhat “game-changing” pathway lessons learned and advices were given for young generation of urologists.

Keywords

Urology, Pathway, Game-changing, Academia

Introduction

My pathway in urology is unusual as described below. The president of Western Society of Japanese Urological Association 2020 meeting (Professor Seichi Saitoh, Ryukyu University) thought this game-changing in a way, and asked me to deliver the lecture based on this life to inspire and advise next generation of urologists. The following is its excerpt.

Early Postgraduate Training:

After medical school Hokkaido University in 1964 and a year of internship I went to the US in 1965. US Educational Commission funded travel grant as a Fulbright scholar. As my internship was not approved in the US I had to take another one and a year of surgery residency in Chicago before eligible for urology program in the US. Hard reality was waiting for this foreign medical graduate with no pulling strings for the well-approved programs. Almost all favored their native sons. Nonetheless I made a tour of interviewing several from mid-west to north-east looking for a glimmering hope. When I received a letter of acceptance from the University of Michigan it was an eureka moment.

Urology training at University of Michigan:

The year 1967 when I started the residency training UM was at the midpoint of century old history [1]. The helm was transiting from Reed M. Nesbit to Jack Lapides. By virtue of happenstance I was lucky to receive training by these two legendary urologists. Dr. Nesbit insisted that he is a clinician and that his close friend and roommate during internship, Nobel Laureate Dr. Charles Huggins, is the true researcher. He knows that basic concept and new ideas could be evolved in the clinic and on the ward without necessity of going to the animal laboratory, which should be volitional and not compulsory [2]. (Fig.1 Reed M. Nesbit (1898~1979) Dr. Lapides always believed that practice of medicine should be based on physiological principle and that unsustainable “facts” should always be questioned. He abhorred simple accumulation of knowledges and insisted on deep thinking or “cerebration” and shrewd skepticism [3]. (Fig.2 Jack Lapides (1914~1995)

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Under their auspices this neophyte, who knew nothing about urology when he came to UM, grew to a confident one toward the end of residency. If mentors are the ones worthy of gratitude for the warmth vital for the growth, I have no hesitation to name both as my true ones. Appreciating his insight to pick me up as a sole FMG Japanese resident of UM’s long history I wrote a thanking note to Dr. Nesbit just before the completion of residency. His reply came back promptly. (Fig.3 Nesbit’s hand written letter dated May 14, 1970) He described how I served well and consoled me for withstanding hardship of the training. He concluded by stating that “I hope also that you will enjoy the stimulating privilege of training other young men in your field of specialization. That is one of our obligation as well as caring for the afflicted, and also one of the most rewarding that can come to a man.” With these inspiring words (privileges obligation and reward) in my heart as a leading guide I returned to my alma mater HU in 1970.

Figure 3.

An early Academic Life at HU:

Working together with young men at HU became a core activity of early academic life. The following are some from these activities.

Pediatric Urology

1.1 Vesicoureteral reflux: Association of bladder dysfunction (uninhibited bladder) with VUR in children with urinary tract infection was reported very first in the world in 1977 [4], preceding two years ahead of the similar work by Koff and Lapides [5]. When I made an appeal for their mis-stated priority Dr. Lapides was apologetic about Koff’s writing “to be the first” in his reply dated 12/2/79. (Fig.4 Hand-written letter (dated December 2, 1979) from Jack Lapides, Apologizing sentence was encircled in red, and typed out below)

1.2 Disorders of UVJ other than VUR: The role of ureteral sheath in megaureter, be it in refluxing MU or primary MU, was addressed both morphologically and functionally [6]. In view of USh involved in the structure of ureteral hiatus, the role of differences in the hiatus, be it common(C), intermediate (I) and/or separate (S) in duplex anomaly was analyzed [7]. In ectopic ureter this was more relevant than ectopic orifice in associated renal anomaly and also in its surgical management [8]. Duality of USh was confirmed in the study of muscular development of the urinary tract in the human embryo [9].

Figure 4.

…Steve Koff was embarrassed to learn of your excellent article and offers his apology. He learned a good lesson in that one should always prefix a positive statement about being the first with “To my knowledge”.…

Neurourology, Urodynamic and BPH

2.1 Sympathetic innervation of the lower urinary tract: In neurogenic bladder the bladder respond supersensitively to para-sympathomimetic, while the urethra not, but rather to sympathomimetic. This is also the very first report of the denervation supersensitivity of the urethra [10]. The mechanism was found to be in the short adnergic system, the activity of which is increased as freed from an inhibitory parasympathetic postganglionic synapse [11] This is the reason for its failure to relax or augmenting activity (DSD) in neurogenic bladder [12]. DS was also confirmed in the refluxing ureter of spinal subjects confirming neural control in the function of UVJ [13]. All these clinical findings are compatible with contemporary basic studies which unfolded intricate innervation pattern of lower urinary tract distinctly different from the traditional one [14, 15].

2.2 Surgical application of neurourology in TURP: TURP is a technique learned at UM. I wanted it not to be a mere operative technique in BPH but also to be applicable in male spinal cord injured. Meanwhile revised concept of the prostate and prostatic urethra was proposed by McNeal [16]. In view of abundant adrenergics in peripheral zone in our study [17] radical TURP by resecting PZ as well was proposed as a manner of surgical sympathectomy to relieve DSD [18]. This surgical application of neurourology in TURP in spinal subjects was a success. Urodynamic confirmations as to relieving voiding dysfunction while not jeopardizing continence were presented [19, 20]. Application of radical TURP in BPH not only yielded high success rate [21], but also shed light on the role of external urethral sphincter [22]. It should be stressed that all these early studies are clinical ones to answer the spectrum of questions from daily practice, literally abiding Nesbit’s admonition. At the same time they exemplify my role as an academic urologist which, I believe, is to bridge basic science and clinical urology.

New Fields in late Academic Life:

In 1982 I was endowed helmsmanship of the department. I focused on two fields to light a way forward. Development of one-stage hypospadias repair (OU) was addressed as ACU lecture on the occasion of 2018 JUA/UAA meeting [23]. The experience in renovacular and renal surgery was presented [24, 25] and addressed as a presidential lecture at JUA meeting in 2000 [26]. Along with reconstructive surgery in kidney transplantation of children [27] stressed that these are the new fields to be tackled by the next generation to make urology a true discipline of surgery.

Lessons and Advices to be heeded:

- Study abroad while young to broaden your scope.

- Pathway is there to be built not to be walked on.

- Seek mentor of your life time.

- Have a healthy skepticism for the dogma.

- Clinical work is demanding as both intellectually and physically as any basic research.

- The role of academic urologist is to bridge the basic science and clinical urology.

- Stay tuned to daily clinical problem where study themes are abundant.

- Publish preferably in leading journals.

- Have working colleagues in the field.

- You did well when surpassed by the young generation. These are the words to be heeded albeit the one from by-gone era.

Summary

Early sojourn to US, urology training at UM, and an academic life at HU were reflected personally. Through these lessons learned and advices were given. I was privileged in that my education and trainings (medical school and US training) were supported by the public fund (Japanese and US government, respectively). Subsequently it was a natural obligation to serve as an academic urologist at HU. It was also rewarding in that I was able to train many next generation of urologists who surpass me both surgically and scientifically. By practicing Nesbit’s admonition (privilege, obligation and reward) I may say the life is well lived.

Abbreviations

JUA- Japanese Urological Association

US- United States

FMG- Foreign Medical Graduate

UM- University of Michigan

HU- Hokkaido University

VUR- Vesicoureteral Reflux

UVJ- Ureterovesical Junction

USh- Ureteral Sheath

MU- Megaureter

DS- Denervation Supersensitivity

TURP- Transurethral Resection of Prostate

DSD- Detrusor Sphincter Dyssynergia

BPH-Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy

OU- One stage Urethroplasty

ACU-Asia Congress of Urology

UAA- Urologic Association of Asia

References

- Konnak JW, Pardanani DS. A history of urology at the University of Michigan 1920–2001 (2002) Historical center for the health sciences monograph series No.7.

- Lapides J, Reed M. Nesbit. His Biography. The University of Michigan Medical Center Journal (1973) 39: 99–100.

- Kogan BA (1990) Jack Lapides Clinician, Teacher, Investigator and Innovator. J Urol 144: 514–516.

- Koyanagi T, Ishikawa T, Tsuji I (1977) Vesicoureteral reflux and uninhibited neurogenic bladder. Int Urol & Nephrol 9: 217–224.

- Koff SA, Lapides J. Piazza DH (1979) Association of urinary tract infection and reflux with uninhibited bladder contractions and voluntary sphincteric obstruction. J Urol 122: 373–376. [crossref]

- Tokunaka S, Koyanagi T (1982) Morphologic study of primary non-reflux megaureters with particular emphasis on the role of the ureteral sheath and ureteral dysplasia. J Urol 128: 399–402. [crossref]

- Koyanagi T, Tsuji I (1979) Experience of complete duplication of the collecting system. Int Urol & Nephrol 11: 27–38.

- Koyanagi T, Hisajima S, Goto T, Tokunaka S, Tsuji I (1980) Everting ureteroceles: Radiographic and endoscopic observation, and surgical management. J Urol 123: 538–543. [crossref]

- Matsuno T,Koyanagi T, Tokunaka S (1984) Muscular development in the urinary tract. J Urol 132: 148–152. [crossref]

- Koyanagi T (1978) Denervation supersensitivity of the urethra to α-adrenergics in the chronic neurogenic bladder. Urol Res 6: 89–93. [crossref]

- Koyanagi T (1979) Further observation on the denervation supersensitivity of the urethra in patients with chronic neurogenic bladder. J Urol 122: 348–351. [crossref]

- Koyanagi T, Arikado K, Takamatsu T, Tsuji I (1982) Relevance of sympathetic dyssynergia in the region of external urethral sphincter: Possible mechanism of voiding dysfunction in the absence of somatic sphincter dyssynergia. J Urol 127: 277–282. [crossref]

- Koyanagi T, Tsuji I (1981) Study of ureteral reflux in neurogenic dysfunction of the bladder: The concept of neurogenic ureter and the role of periureteral sheath in the genesis of reflux and supersensitive response to autonomic drugs. J Urol 126: 210–217. [crossref]

- Elbadawi A (1982) Neuromorphologic basis of vesicourethral function: Histochemistry, ultrastructure, and function of intrinsic nerves of the bladder and urethra. Neurourol & Urodyn 1: 3–50.

- Norlen LJ (1982) Influence of sympathetic nervous system on the lower urinary tract and its clinical implications. Neurourol & Urodyn 1: 129–148.

- McNeal JE (1972) The prostate and prostatic urethra: A morphologic synthesis. J Urol 107: 1008–1016. [crossref]

- Kobayashi S, Demura T, Nonomura K, Koyanagi T (1991) Autoradiographic localization of the adrenoceptors in human prostate: Special reference to zonal difference. J Urol 146: 887–890. [crossref]

- Koyanagi T, Arikado K, Tsuji I (1981) Radical transurethral resection of the prostate for neurogenic dysfunction of the bladder in male paraplegics. J Urol 125: 521–527. [crossref]

- Koyanagi T, Morita H et al. (1987) Radial transurethral resections of the prostate in male paraplegics revisited: Further clinical experience and urodynamics considerations for its effectiveness. J Urol 137: 72–76.

- Shinno Y, Koyanagi T, Kakizaki H, Kobayashi S, Ameda K et al. (1994) Urinary Control after radical transurethral resection of the prostate in male paraplegics: Urodynamic evaluation of its effectiveness in relieving incontinence. Int J Urol 1: 78–84. [crossref]

- Machino R, Kakizaki H, Ameda K, Shibata T, Tanaka H et al. ( 2002) Detrusor instability with equivocal obstruction: A predictor of unfavorable symptomatic outcomes after transurethral prostatectomy. Neurourol & Urodynamics 21: 444–449. [crossref]

- Koyanagi T (1980) Studies of the sphincteric system located distally in the urethra: The external urethral sphincter revisited. J Urol 124: 400–406. [crossref]

- Koyanagi T (2018) ACU lecture: One-stage hypospadias repair- Future is Asia the East. Int J Urol 25: 314–317. [crossref]

- Seki T, Koyanagi T, Togashi M, Chikaraishi T, Tanda K et al (1997) Experience with revascularizing renal artery aneurysms: Is it feasible and worth attempting? J Urol 158: 357–362. [crossref]

- Nobuo Shinohara, Katsuya Nonomura, Tohru Harabayashi, Masaki Togashi, Satoshi Nagamori et al. (1995) Nephron sparing surgery for renal cell carcinoma in von Hippel Lindau disease. J Urol 154: 2016–2019.

- Koyanagi T, Nonomura K, Takeuchi I, Watarai Y, Seki T et al. (2002) Surgery for renovascular diseases: A single center experience in revascularizing renal artery stenosis and aneurysm. Urol Int 68: 24–31. [crossref]

- Chikaraishi T, Nonomura K, Kakizaki H, Seki T, Morita K et al. (1998) Kidney transplamtation in patients with neurovesical dysfunction. Int J Urol 5: 428–435. [crossref]

The First Step to Solving any Problem is Recognizing there is one!

DOI: 10.31038/PEP.2020111

Short Communication

Since the introduction of the Inflammation and Heart Disease Theory [1–3], a shift from a cholesterol only etiology for coronary artery disease (CAD) has occurred. Unfortunately, hundreds if not thousands of research studies – involving millions of dollars in vested funding – have focused on measuring changes in blood tests rather than measuring actual changes in CAD itself [4,5].

The consequence has been an amalgam of misinformation fueled by opposing factions of scientists and pseudo-scientists resembling more of a schoolyard brawl than scientific search for the truth. From this brawl both the media and social scientific neophytes vie for attention – a demonstration of true social desperation and not scientific discourse.

Fundamental questions about the impact of diet and drug treatment [6–9] remain poorly addressed due to this deeply flawed approach – thus the role diet and lifestyle play in preventing CAD remain unanswered.

While we have some information about what may be happening to people [8] who change their diets – the truth is we do not know and we will not know until we decide to scientifically any the question by measuring [5–7] the changes in CAD, which diets and medications [9] have on people with and without underlying CAD. The first step to solving this question of dietary epidemiology and prevention of CAD is to recognize we haven’t been measuring the problem – CAD – itself. The first step to solving any problem is recognizing there is one.

Acknowledgments: FMTVDM issued to first author. Figures expressly reproduced with permission of first author.

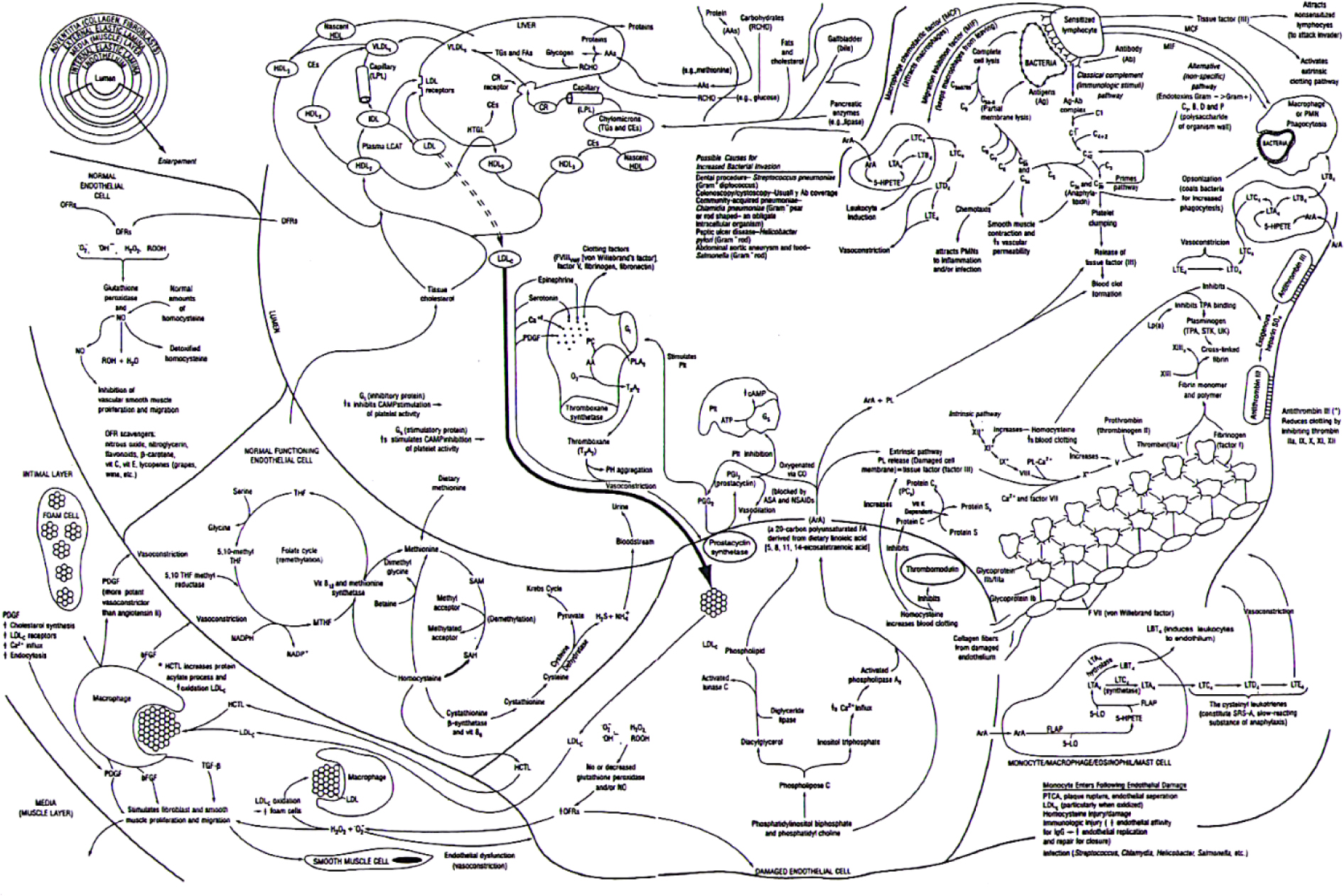

Figure 1. Coronary artery disease is an inflammatory process precipitated by more than a dozen variables. Each variable contributes to inflammation within the blood vessels of the body, including the coronary arteries to varying degrees in different individuals [1].

Figure 1. Fleming Inflammation and Vascular Disease Theory [2].

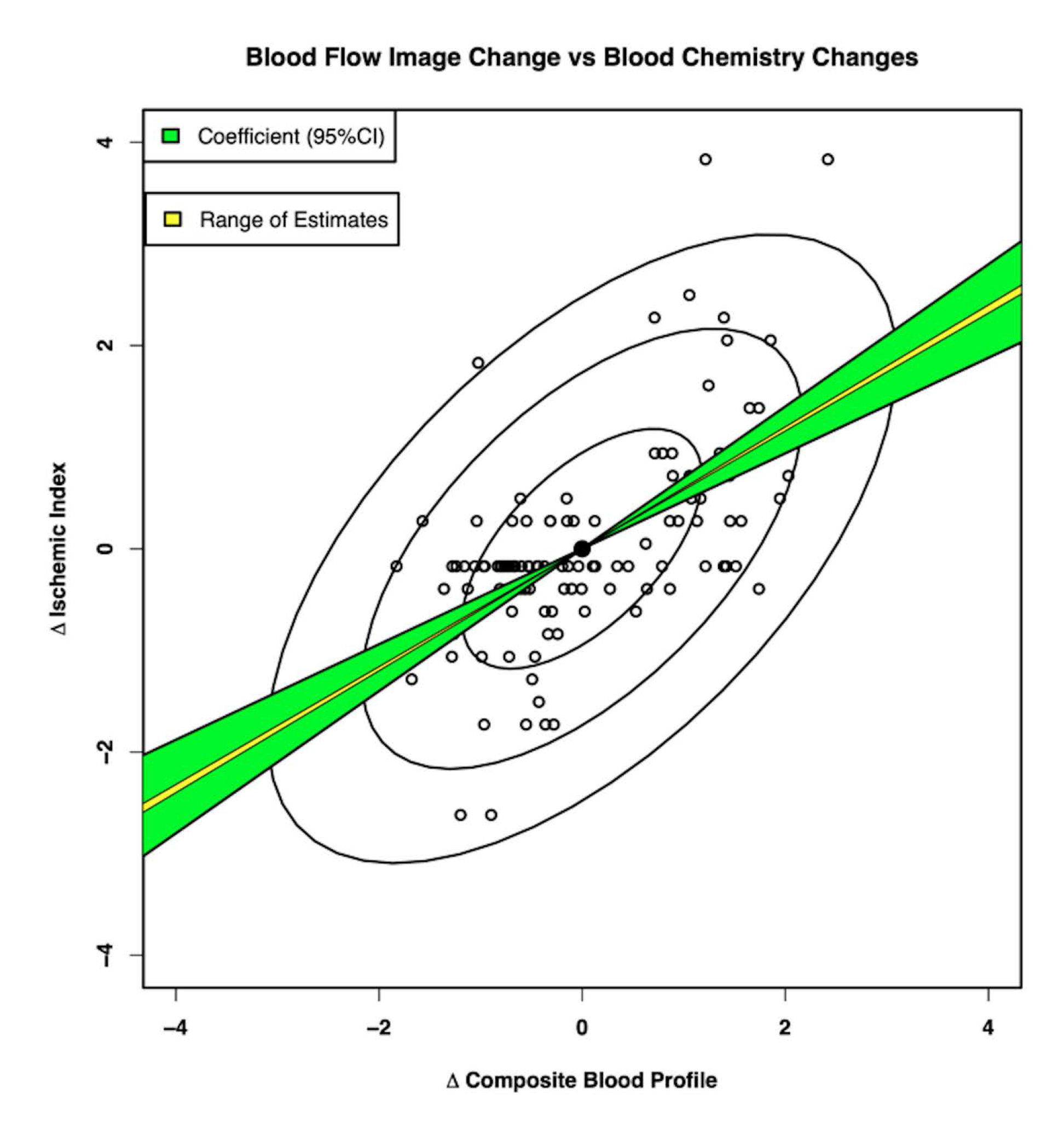

Figure 2. The X-axis displays the composite blood profile including TC, fat, low HDL, IL-6, Lp, and Fib. The Y-axis displays changes in ischemia as measured by nuclear imaging. The standard regression analysis shows both the range of estimates (yellow) and the 95% confidence intervals (green). HDL, high-density lipoprotein; IL-6, interleukin-6; Lp-a, lipoprotein-a; Fib, fibrinogen; Tc, total cholesterol [4].

Figure 2. Standardized regression of coronary blood flow on composite blood profile [6].

References

- Fleming RM. Chapter 64. The Pathogenesis of Vascular Disease. Textbook of Angiology. John C. Chang Editor, Springer-Verlag New York, NY. 1999, pp. 787–798.

- Fleming RM. Stop Inflammation Now! with Tom Monte. Published by Putnam Books and Avery Books. December 2003. ISBN: 0399151117

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hvb_Ced7KyA&t=22s

- Fleming RM, Harrington GM. “What is the Relationship between Myocardial Perfusion Imaging and Coronary Artery Disease Risk Factors and Markers of Inflammation?” Angiology 2008;59:16–25.

- The Fleming Method for Tissue and Vascular Differentiation and Metabolism (FMTVDM) using same state single or sequential quantification comparisons. Patent Number 9566037. Issued 02/14/2017.

- Fleming RM, Fleming MR, McKusick A, Chaudhuri TK. The Diet Wars Challenge Study: Insulin Resistance, Cholesterol and Inflammation. ACTA Scientific Pharm Sci. 2019;3(6). ISSN: 2581–5423.

- Fleming RM, Fleming MR, McKusick A, Ayoob KT, Chaudhuri TK. A Call for the Definitive Diet Study to End the Diet Debate Once and for All. Gen Med. 2019;7(1):322. DOI: 10.24105/2327-5146.7.322.

- Fleming RM, Fleming MR, Chaudhuri TK, Harrington GM. Cardiovascular Outcomes of Diet Counseling. Edel J Biomed Res Rev. 2019;1(1):20–29.

- Fleming RM, Fleming MR, Chaudhuri TK. How Beneficial are Statins and PCSK9-Inhibitors? Scho J Food & Nutr 2019;2(3):213–218.DOI:10.32474/SJFN.2019.02.000136.