DOI: 10.31038/JCRM.2019253

Abstract

The cross-sectional GYNAUTO-CHAD study compared the acceptability and HPV DNA diagnostic accuracy of clinician-collected endocervical sample with swab (as reference collection) and genital self-collection method with a veil (V-Veil-Up Gyn Collection Device, V-Veil-Up Pharma Ltd., Nicosia, Cyprus) in adult African women. Five of the 10 districts of N’Djamena were randomly selected for inclusion. Peer educators contacted adult women in in community churches and mosques or women association networks to participate to the survey and to come to the clinic for women’s sexual health “La Renaissance Plus”. A clinician performed a pelvic examination and obtained an endocervical specimen using flocked swab. Genital secretions were also obtained by self-collection using veil. Both clinician- and self-collected specimens were tested for HPV and HR-HPV DNA using multiplex real-time PCR. Acceptability of both collection methods was assessed; test positivity was compared by assessing methods agreement, sensitivity and specificity. A total of 253 women (mean age, 35.0 years) was prospectively enrolled. The prevalence of HPV infection was 22.9%, including 68.9% of high risk-HPV (HR-HPV), with unusual HR-HPV genotypes distribution and preponderance (≈70%) of HR-HPV targeted by Gardasil-9® vaccine. Veil-based genital self-collection showed high acceptability (96%), feasibility and satisfaction. Self-collection by veil was non-inferior to clinician-based collection for HR-HPV DNA molecular testing, with “good” agreement between both methods, high sensitivity (95.0%; 95%CI: 88.3–100.0%) and specificity (88.2%; 95%CI: 83.9–92.6%). Remarkably, the rates of HPV DNA and HR-HPV DNA positivity were significantly higher (1.67- and 1.57- fold, respectively) when using veil-based collected genital secretions than clinician-collected cervical secretions by swab. In conclusion, self-collection of genital secretions using the V-Veil-Up Gyn Collection Device constitutes a simple, highly acceptable and powerful tool to collect genital secretions for further molecular testing and screening of oncogenic HR-HPV that could be easily implemented in the national cervical cancer prevention program in Chad.

Keywords

Cervical cancer; HPV detection and genotyping; Self-collection; Clinician-collection; Veil; Sub-Saharan Africa

Introduction

High risk-human papillomavirus (HR-HPV) genotypes are responsible for 7.7% of all cancers in developing countries [1–3]. In sub-Saharan Africa, cervical cancer associated with persistent cervical HR-HPV infection is become the most common cancer in women in many countries, with more than 75,000 new cases and nearly 50,000 deaths registered each year [4–8]. Cervical cancer is a potentially preventable disease, including primary prevention with HPV prophylactic vaccination for women early before the first sexual intercourse, and secondary prevention mainly based on early molecular detection of cervical HR-HPV and cervical smear with Pap test for cytology [7,10]. In order to increase the coverage of screening programs in resource-limited countries, self-sampling of genital samples intended for molecular testing constitutes a promising alternative to Pap smear screening [11–17]. Self-sampling may be easily carry out individually by women at home without special medical qualification and special assistance [18, 19], and allows women to preserve their intimacy [13, 20, 21]. Molecular detection of HR-HPV using self-collected genital secretions (collected at home or at health care center) has proven to be nearly as sensitive as molecular screening performed on samples collected by clinician in specialized health care facility [12, 22–31]. In the African context, self-sampling of genital secretions was generally well accepted and easily feasible [12–14, 16, 17, 30, 32–36], and it may furthermore facilitate the screening of cervical cancer in remote populations far from large health care centers [21, 34–37]. Finally, self-sampling may be especially valuable as an alternative method of cervical cancer screening as a method to enroll women who otherwise would not participate in population-based cervical cancer screening [17], and particularly in resources-constrained areas [10, 28]. Chad is a country of around 15 million people, including more than 3 million women aged more than 25 years [38, 39]. In 2016, Mortier and colleagues reported that HIV-infected Chadian women were at high-risk for low and high-grade cervical lesions, suggesting unsuspected high burden of cervical HPV infection in Chad [40], as further reported in the capital city N’Djamena [41]. However, cervical cancer prevention in Chad remains largely insufficient [40, 42–44]. We recently demonstrated in Chadian women that a novel genital veil (V-Veil-Up Gyn Collection Device, V-Veil-Up Pharma Ltd., Nicosia, Cyprus) constitutes a useful self-collection device to collect female genital secretions for accurate molecular detection of genital bacterial sexually transmitted infections (STIs) [45]. Finally, the main objective of the present study was to assess the acceptability, feasibility and accuracy of the self-sampling V-Veil-Up Gyn Collection Device in adult women living in Chad to collect genital secretions for diagnosing HPV infections by multiplex real-time PCR.

Materials and methods

Study design

The cross-sectional GYNAUTO-CHAD study compared the acceptability and HPV DNA diagnostic accuracy of a clinician-collected endocervical sample with swab and a cervicovaginal self-collection method with veil device in adult women living in N’Djamena, Chad, recruited from the community. The 2015 Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) guidelines were used for reporting the study [46, 47].

Enrolment and selection criteria

Adult asymptomatic women were recruited from the community after randomization of 5 districts selected out of the 10 districts of N’Djamena, as previously in extenso described [41,45]. After oral consent, the selected women were invited, with paid transportation, to come to the clinic “La Renaissance Plus”, N’Djamena, which is one of the main settings for women’s sexual health in Chad, and to participate in the study. Childbearing-aged and older women living in N’Djamena regularly attend the clinic “La Renaissance Plus” for gynecological examinations and for obstetrical services. The inclusion criteria were being a volunteer, having given signed informed consent, being aged between 25–65 years (consistent with current cervical cancer screening recommendations [7]), being sexually active, having no genital troubles at physical examination, being not menstruating, having no sexual intercourse for at least 48 hours (as recommended for HPV molecular testing in female genital secretions [48]) and having completed the questionnaire. Exclusion criteria included age less than 25 years and more than 65 years, having genital troubles, having menstruations, having recent sexual intercourse less than 48 hours, not willing to participate to the study or to answer the face-to-face questionnaire to collect data. Note that the menstrual cycle phases were not taken into account, since it has been previously demonstrated that they do not affect HPV detection in female genital secretions [49].

Clinical visit procedures and genital samples collection

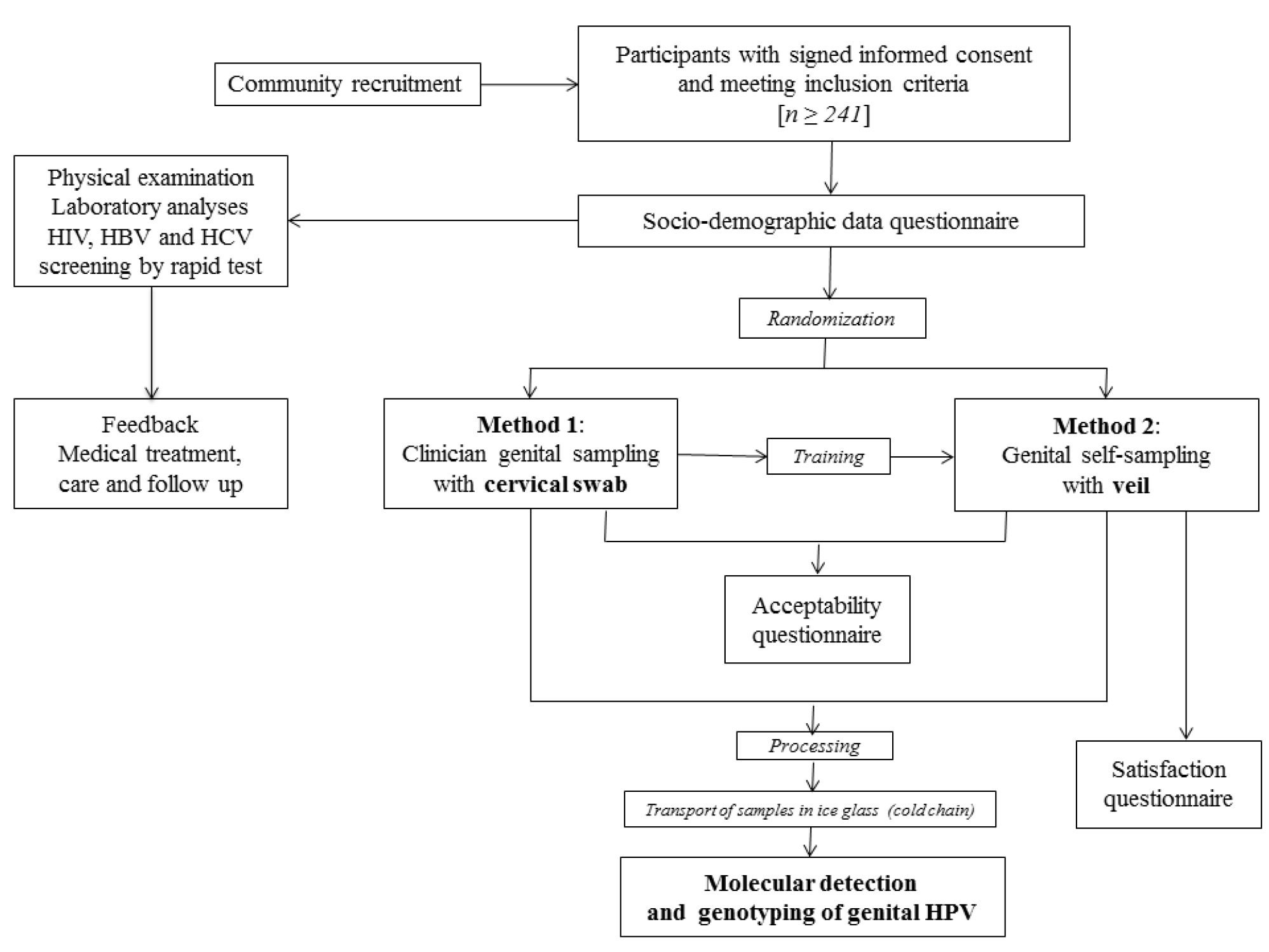

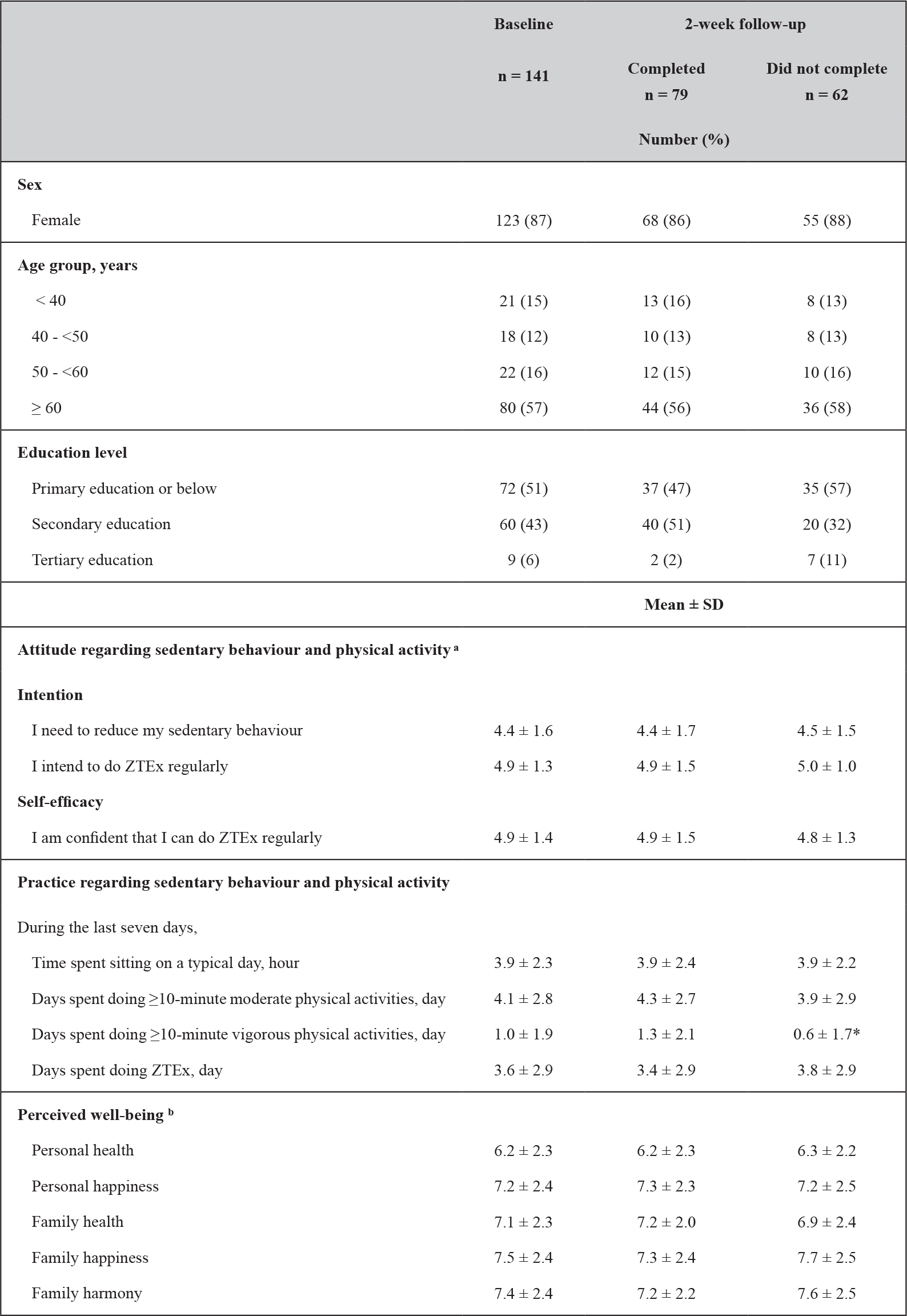

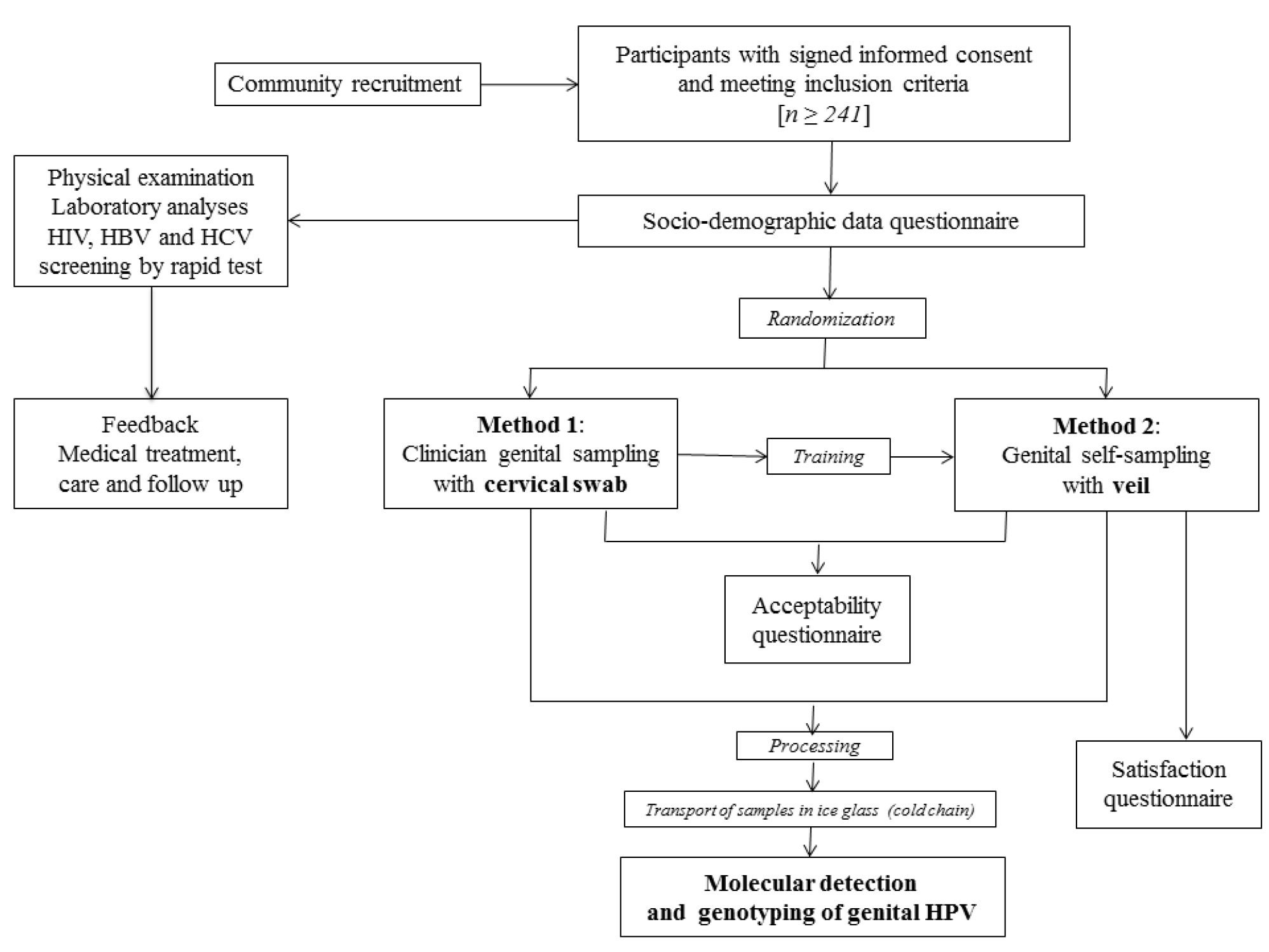

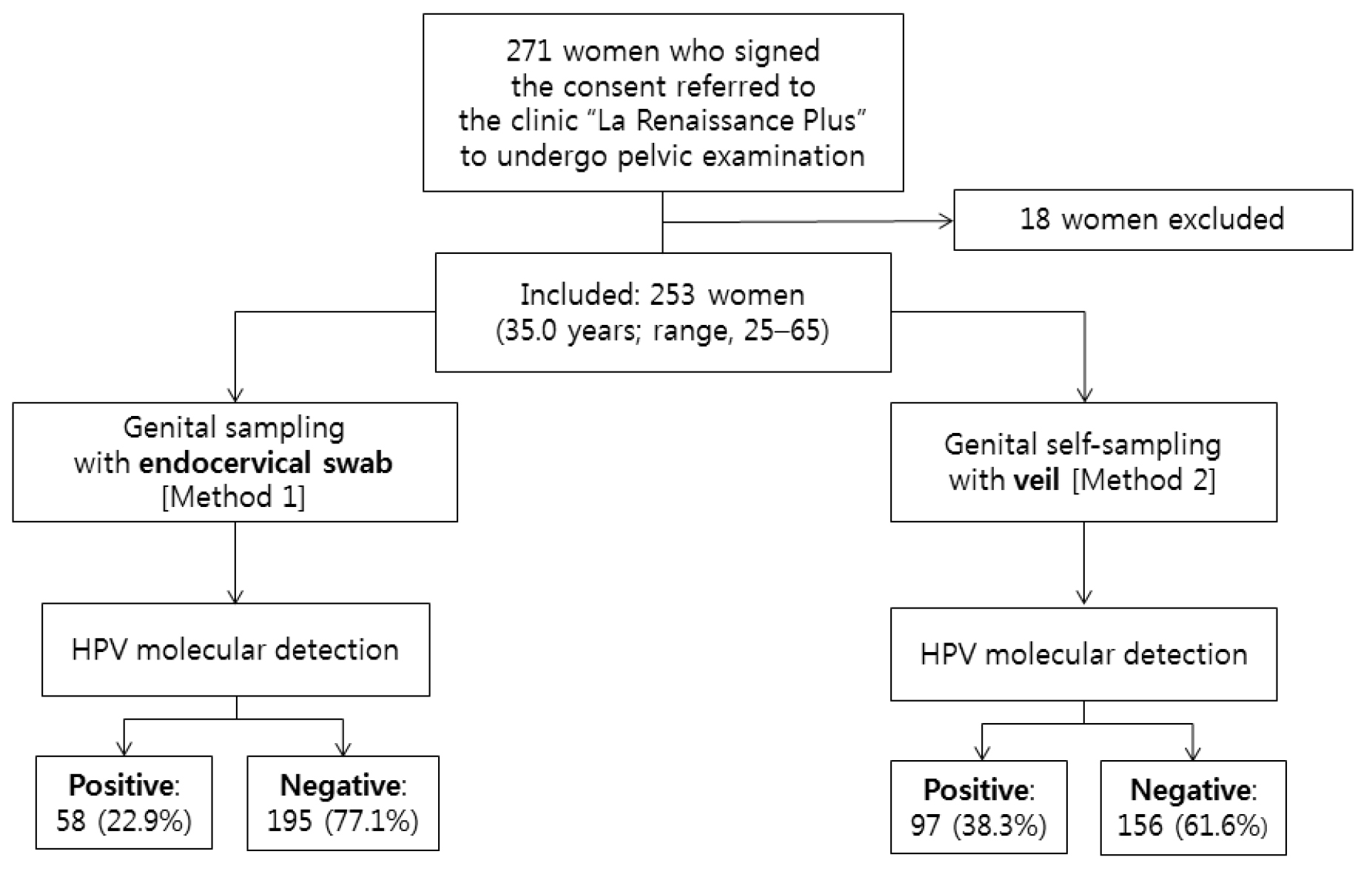

The Figure 1 depicts the overview of the one-time clinical visit procedures of the GYNAUTO-CHAD study.Women eligible for the study were received by a medical staff (preferably nurse) who explained the progress of the step-by-step protocol and had them to sign the informed consent (Figure 1). After having signed the informed consent form, the selected women benefited from free HIV and hepatitis B (HBV) and C (HCV) testing, by multiplex HIV/HCV/HBsAg immunochromatographic rapid test (Biosynex, Strasbourg, France) [50], clinical services including gynecological examination, family planning counseling, STIs diagnosis, laboratory analysis when necessary and appropriate treatment for those suffering from gynecologic disorders, HIV or other genital infections. All women received an information session on HIV and STIs. At inclusion, a standardized interview was conducted at the clinic “La Renaissance Plus”, by experienced counselors, using a face-to-face questionnaire, to collect socio-demographic characteristics and behavioral data, including age, marital status, social occupation, education level, residence location in N’Djamena, history of STI, HIV status, birth control method, genital hygiene during menses, sexual behavioral characteristics such as the number of lifetime sexual partners and the age at first sexual intercourse, and assessment of knowledge regarding cervical cancer. In order to eliminate any possible bias of sampling method and timing, the participants were further randomly selected to collect the genital secretions by clinician-based swab sampling first, followed by the veil-based self-sampling after the nurse-training, or by the veil-based self-sampling first followed by the clinician-based swab sampling. Thus, after completion of the socio-demographic questionnaire, all the biological specimen were sampled and processed in the following order: i) Samples specific for each patient for medical exams according to the medical prescription following the consultation; ii) Endocervical swab collected by a doctor [Method 1] or self-collection of genital secretions using the V-Veil-Up Gyn Collection Device [Method 2] according to the randomization. The gold standard Method 1 was carried out by a doctor using a flocked swab (Copan Diagnostic Inc., California, USA). Briefly, after placing the speculum (without lubricant prior to insertion), the physician used the swab to perform cervical sampling by introducing it into the cervical canal and performing 5 rotations before being removed and immediately placed in its plastic container. The swab was then placed in the cold (ice pack).

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the GYNAUTO-CHAD study. The GYNAUTO-CHAD study consisted in community-based recruitment of at least 261 adult women to be referred to the gynecologic clinic “La Renaissance Plus”, N’Djamena, Chad. The participants meeting the inclusion criteria were subjected to physical examination and care when needed, and tested for 3 chronic viral infections endemic in Chad (HIV, HBV and HCV) by capillary-based immunochromatographic rapid test, and filled in the face-to-face socio-demographic questionnaire. Afterwards, the participants were trained for self-sampling collection using the V-Veil-Up Gyn Collection Device (V-Veil-Up Pharma Ltd.) and randomly submitted to the sampling procedure with Method 1 (clinician-based collection of cervical secretions by swab, as gold standard) followed by the Method 2 (self-collection by veil) or inversely. The acceptability and satisfaction questionnaire were then administrated to the study women and collected samples were processed before molecular detection and genotyping of genital HPV infection.

For the self-collection Method 2, the study participant firstly received from a nurse a 15-minutes training on how to use the V-Veil-Up Gyn Collection Device for vaginal self-sampling, as previously reported [45]. After instructing the participant, the nurse leaved the sampling room and the participant then performed herself the self-sampling, without any help from the nurse. The participant followed the instructions for use of the V-Veil-Up Gyn Collection Device. Briefly, the study woman inserted the veil into her vagina, leaved it in-place for one hour; then removed it with the string, and returned it to the nurse. The study nurse did not witness veil insertion and removal. The nurse placed the veil impregnated with genital secretions into the dedicated collection box and closed it correctly with the cap. The veil collection box consisted of a 15 mL plastic box that contained 10 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution to prevent drying of the sample. The nurse verified that the PBS buffer completely submerged the veil and checked that the identification number in the label on the collection box corresponded effectively to the participant. The veil in its box was then placed in the cold (ice pack). After returning the veil specimen, a second nurse administered acceptability and satisfaction questionnaires on the woman’s experiences about the pelvic examination and clinician-based collection and the veil-based self-collection. To minimize bias, the study nurse who performed the pelvic examination was in another room and did not participate in the post-test questionnaire administration. The objectives of the acceptability questionnaire was to evaluate the study women’s experiences related to the perception of care, comfort, privacy, embarrassment, or pain associated to each collection method. The satisfaction questionnaire consisted in questions regarding the ability to understand the instructions for use of the V-Veil-Up Gyn Collection Device and its component and to perform self-collection, including home collection, and also assessed difficulties encountered during veil-collection.

Genital samples processing

Each genital sample was transported in ice packs within an hour after collection to be stored at -80°C at the virology laboratory of the hôpital Général de Référence Nationale, N’Djamena, Chad. Swabs and veils were further transported in frozen ice packs to the virology laboratory of the hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou, Paris, France, for molecular analyses.

Nucleic acid extraction

DNA was extracted from the tip of swab specimens using the DNeasyBlood and Tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), as recommended by the manufacturer. After extraction, DNA was concentrated in 100 μL of the elution buffer provided in the extraction kit and stored at -80°C before HPV DNA detection and genotyping, as described previously [51]. Veil samples soaked with genital secretions within PBS buffer were carefully removed from their collection box and placed into a syringe to be drained by pulling the syringe’s plunger into a 15 mL tube. The whole genital secretions were then vigorously vortexed to homogenize the fluids and finally aliquoted in 1.5 mL cryotubes (Eppendorf, Hambourg, Germany) and store at -80°C before the nucleic acid extraction procedure. In order to avoid any contamination between different specimens, the working area was sterilized between the processing of each specimen and all the consumables including gloves, syringe, forceps were for single use and were immediately discarded together with the box container. Finally, the nucleic acid extraction procedure was carried out with the DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen), in 1 mL of the concentrated cervicovaginal veil-collected specimen and extracted DNA was placed in 100 μL of the elution buffer provided in the extraction kit and stored at -80°C before HPV DNA detection and genotyping.

HPV detection and genotyping

HPV detection and genotyping was performed on both the clinician- and self- collected specimens using the CE IVD-marked multiplex real-time PCR assay Anyplex™ II HPV28 (Seegene, Seoul, South Korea), as described previously [52]. The kit contains specific primers targeting 28 HPV, and is based on Seegene’s proprietary DPO™ and MuDT™ technologies [53], which allow to avoid mismatch priming and to quantify each target in a single fluorescence channel, respectively. According to the HPV classification nomenclature provided by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) [54] Anyplex™ II HPV28 technology allows to detect 28 HPV genotypes in a single specimen, including 13 high-risk types (HR-HPV -16, -18, -31, -33, -35, -39, -45, -51, -52, -56, -58, -59, and -68), 9 low-risk (LR) types (LR-HPV -6, -11, -40, -42, -43, -44,-53, -54 and -70) and then, 6 genotypes classified as possibly carcinogenic (HPV-26, -61, -66, -69, -73 and -82). Briefly, 5µL of swab- or veil- extracted DNA were added into two reaction mixtures (20 µL) containing each other, one of the primers sets A and B [52]. The DNA amplification and the genotyping process were carried out in 2 reactions performed on the CFX96™ real-time PCR instrument (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France) [52]. The Anyplex™ II HPV28 genotyping test has been found to be suitable for HPV detection and genotyping in cervical secretions [52, 55–58]. Data recording and interpretation were automated with Seegene viewer software (Seegene), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A sample was considered positive for any HPV if containing any of the 28 types targeted by the Anyplex™ II HPV28 detection test; positive for multiple HPV when containing at least 2 types of the 28 HPV types included in genotypic test; HR-HPV positive and multiple HR-HPV positive when containing respectively at least 1 HR-HPV type and at least 2 high-risk types belonging to the 13 high-risk types targeted by the Anyplex™ II HPV28 detection test, irrespective of the presence of LR-HPV. The virology laboratory was accredited in 2013 by the Comité Français d’Accréditation (COFRAC) according to the ISO 15189 norma for the biological markers “HPV detection” and “HPV genotyping”.

Sample size

We hypothesized that Method 2 (self-sampling) would be non-inferior to Method 1 (flocked swab as gold standard), with a tolerated difference of Δ in the detection rate of HPV infections by molecular analysis between the two methods of collection. The requested minimum number (n) of subject to include was obtained by using Epi Info version 3.5.4 (CDC, Atlanta, USA), and by setting 95% confidence level, 80% statistical power, and considering estimated HPV prevalence of two methods in Chad. There are no data on the prevalence of genital HPV infections among women living in the Chad. In order to estimate the HPV DNA positivity in our study population, we used prevalences of genital HPV detection from comparable populations of women living in other Central African countries previously published in the literature, including 12.5% in Democratic Republic of the Congo [59], 18.5% and 34.0% in Cameroon [60, 61], and 22.2% in Rwanda [62]. Based on this assumption, we estimated the mean prevalence (P1) of HPV DNA test results to be 21.7% in the clinician-collected arm. We conducted a non-inferiority comparison with the hypothesis that the difference in HPV DNA positivity between the veil-based self-collection and clinician-collection methods would be less than 10%. With Δ of 10%, the requested minimum number (n) of subject to include was at least 241 participants.

Statistical analyses

Data was entered into an Excel database and analyzed using IBM® SPSS® Statistics 20 software (IBM, SPSS Inc, Armonk, New York, USA). Means and standard deviations (SD) were calculated for quantitative variables and proportions for categorical variables. The results were presented along with their 95% confidence interval (CI) using the Wilson score bounds for categorical variables. The overall prevalences of HPV DNA detection [any genotypes, HR-genotypes and HPV genotypes targeted by the 9-valent Gardasil-9® vaccine (Merck & Co. Inc., New Jersey, USA)] between the two collection methods were compared using the Mac Nemar’s test for paired data. The Wilcoxon’s test of paired data was used for comparison of the mean notes according to the Likert scale of acceptability of the two methods (veil-based self-collection versus swab-based clinician-collection). The agreement between the two collection methods was estimated by Cohen’s κ coefficient, and the degree of agreement was determined as ranked by Landlis and Koch [63]. Percent agreement corresponded to the observed proportion of identical results between veil-based self-collection compared to swab-based clinician-collection. Note that the acceptability of the clinician-based collection by swab and that of the veil self-collection were assessed using an arbitrary quantitative Likert scale [64] based on four different scale ranging from 1 (most difficult), 2 (difficult), 3 (easy) to 4 (= very easy or comfortable). Similarly, the satisfaction regarding the veil self-collection method was assessed using another arbitrary quantitative Likert scale based on four different scale ranging from 1 (less favorable), 2 (moderately favorable), 3 (favorable) to 4 (= most favorable). The mean and standard deviation for Likert scale data were calculated for each acceptability and satisfaction item using face-to-face questionnaires. The clinician-collected HPV DNA test results were used as the reference standard to estimate the sensitivity and specificity, with corresponding 95%CI, of the veil-collection method.

Results

Characteristics of study population

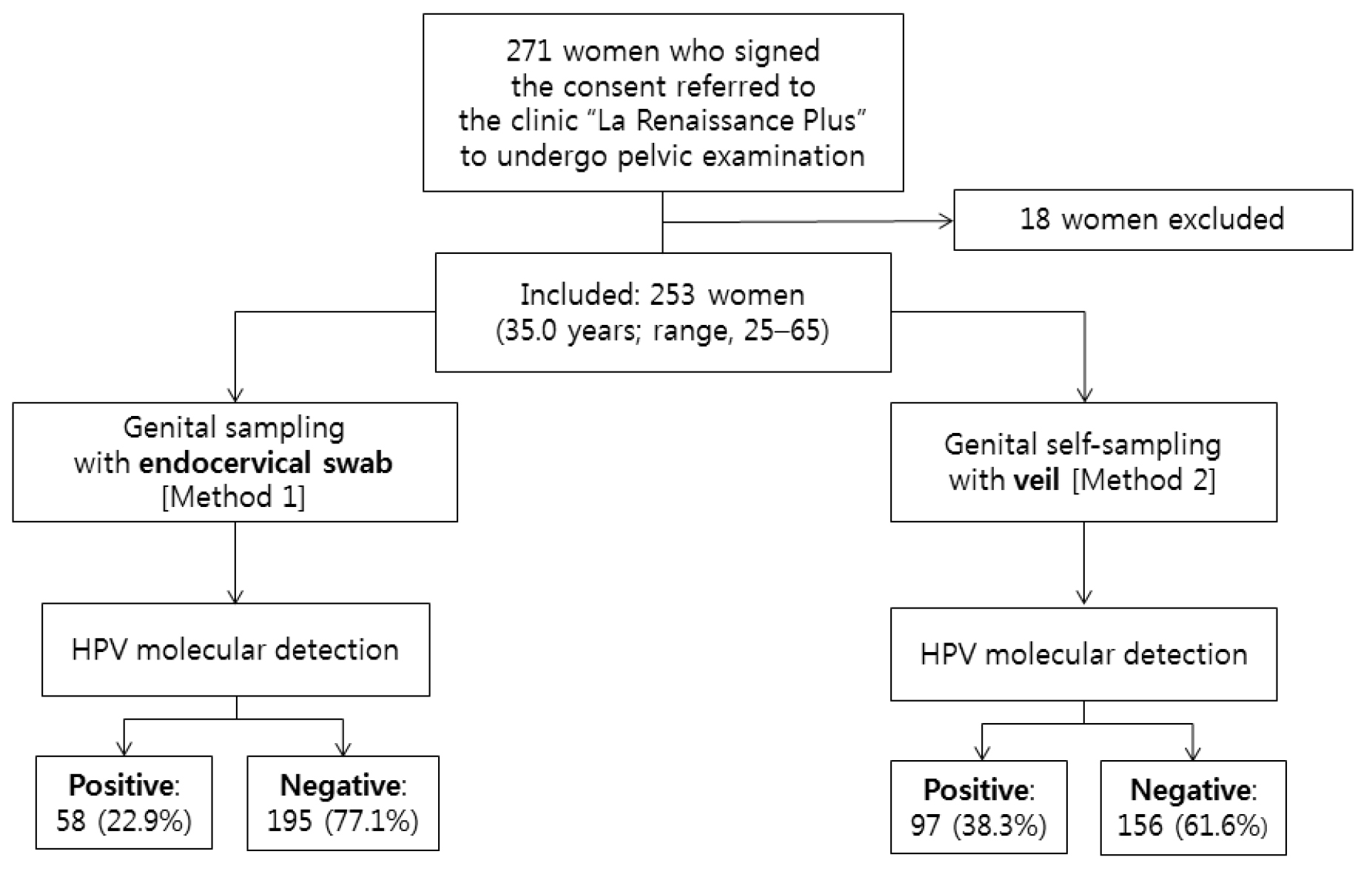

A total of 271 women from the 23 inclusion sites accepted to participate to the study, as previously reported [41,45] (Figure 2). After physical examination, 18 women were excluded because of genital troubles (vaginal discharge: 5; suspicion of STI: 3; genital bleeding: 5; sexual intercourse less than 2 days: 5). Finally, a total of 253 women (mean age, 35.0 years; range, 25–65) referred to the clinic “La Renaissance Plus” were consecutively and prospectively included in the study. Their socio-demographic characteristics, past history of STIs, sexual behavior, contraception and practices of feminine hygiene during menstruation and genital toilet have previously reported [45]. Using multiplex HIV/HCV/HBsAg rapid test, 9 study women (3.5%; 95% CI: 1.3–5.8) were infected by HIV-1, 19 (7.5%; 95% CI: 4.3–10.8) by HBV (positivity for HBsAg) and 8 (3.2%; 95% CI: 1.1–5.3) were seropositive for HCV. Most women (31.6%; 95% CI: 25.9–37.4) were young, aged from 25 to 29 years, engaged in life couple with a male partner (78.3%; 95% CI: 73.2–83.3), with a relatively high education level (32.1%; 95% CI: 26.3–37.7 and 30.4%; 95% CI: 24.7–36.1, in high school level and university, respectively); but most of them were unemployed (54.2%; 95% CI: 48.1–60.3). The majority of study women (82.2%; 95% CI: 77.5–86.9) reported having only one regular sexual partner in their life, while about 20% reported to have had up to 5 different sexual partners. Generally, the study women began sexual activity at 16 to 20 years (56.2%; 95% CI: 50.1–62.3), whereas some of them (13.8%; 95% CI: 9.6–18.1) started their sexual life earlier, before the age of 16 years. The vast majority of women (74.4%) did not take any birth control methods. Concerning the feminine hygiene during menstruation, most women (90.3%) were using sanitary napkins, while a minority (13.0%) used commercially available tampons. Genital (vulva or vagina) toilet was the rule, including post-coital toilet with water and finger in 90.3%. Finally, none of the women included in the GYNAUTO-CHAD study had ever been screened for cervical cancer and nor vaccinated against HPV infection.

Figure 2. Flow diagram of study recruitment, specimen collection, and HPV test results by multiplex real-time PCR.

Acceptability of collection methods

Participants reported feeling much better cared for during the veil-based self-collection (mean note of 3.1 according to the Likert scale of acceptability) compared to swab-based clinician-collection (mean note of 1.4; P < 0.02) and also more in privacy handled during self-collection (mean note of 3.1) compared to clinician-collection (mean note of 1.4; P < 0.005) (Table 1). There were no other significant differences in embarrassment, discomfort or genital pain between the two collection methods (Table 1). When asked to choose one collection method, 243 (96.0%) of study women responded that they would prefer the self-collection method. Furthermore, most participants (237; 89.7%) reported that they would be willing to perform veil-collection at home and bring the specimen with them to clinic.

Table 1. Acceptability of veil-based self-sampling using the V-Veil-Up Gyn Collection Device (V-Veil-Up Pharma Ltd.) compared to swab-based clinician-collection for HPV DNA testing among 253 study women living in N’Djamena, Chad.

|

Acceptability items*

|

Veil-based self-collection [mean (SD)]

|

Swab-based clinician-collection [mean (SD)]

|

P-value**

|

|

How well cared for did you feel?

|

3.1 (0.8)

|

1.4 (0.5)

|

0.011

|

|

How well was your privacy handled during the test?

|

3.1 (0.5)

|

1.4 (0.5)

|

0.003

|

|

Did you feel embarrassed?

|

3.3 (1.2)

|

3.1 (1.4)

|

0.835

|

|

Did the test cause you any genital discomfort?

|

3.1 (1.3)

|

3.1 (1.2)

|

1.000

|

|

Did the test cause you any genital pain?

|

2.9 (1.4)

|

2.5 (1.4)

|

0.700

|

* The scale of acceptability was assessed by a Likert scale ranging from 1 (most difficult) to 4 (= most favorable); the results are mean ± 1 standard deviation (SD);

** Statistical comparisons were assessed by Wilcoxon’s test for paired data.

Satisfaction of self-sampling using the V-Veil-Up Gyn Collection Device

The results of the face-to-face satisfaction questionnaire regarding veil-based self-sampling using the V-Veil-Up Gyn Collection Device are shown in the Table 2. In addition, most women (231; 91.3%) reported that the instructions for use written in French were easy to read and to understand, while the verbal explanations on how to use the collection device showed higher mean note according to the Likert scale of satisfaction (written versus oral explanation: 2.9/4 and 3.6/4, respectively). A significant number of participants (76; 30.0%) reported difficulties in correctly interpreting schemas. The large majority of women (245; 96.8%) were able to recognize correctly the component’s device, with high notes (3.6/4). In addition, the veil was generally (243; 97.6%) correctly placed with the applicator and removed with the string. Difficulties on understanding how to place the veil deep within the vaginal cavity were frequently encountered in one-third of participants (86; 33.9%) with a low mean note of 0.9/4. All items concerning the general satisfaction of the V-Veil-Up Gyn Collection Device showed high mean notes from 2.9 to 3.3. Discomfort when carrying the veil concerned only urges to urinate. Genital pain when placing or wearing the veil was reported in a minority of women (10; 3.9%), all being more than 45 years-old. Finally, only 12 (4.7%) women reported some difficulties with performing the self-collection.

Table 2. Satisfaction questionnaire regarding veil-based self-sampling using the V-Veil-Up Gyn Collection Device (V-Veil-Up Pharma Ltd.) among 253 study women living in N’Djamena, Chad.

|

Variables*

|

Veil-based

self-collection

[mean (SD)]

|

95%CI

|

|

Understanding of instruction for use

|

|

Instruction for use in French language

|

2.9 (1.1)

|

[2.7-3.0]

|

|

Verbal explanation of instruction for use

|

3.6 (0.5)

|

[3.5-3.7]

|

|

Anatomic sketches

|

2.4 (1.1)

|

[2.2-2.5]

|

|

Understanding of component’s device

|

|

Device has three components (veil ; applicator and string)

|

3.6 (0.4)

|

[3.6-3.7]

|

|

Veil includes pocket for drug or cream

|

3.6 (0.5)

|

[3.6-3.7]

|

|

Correct use of the veil

|

|

Applicator to be placed in the pocket

|

3.7 (0.5)

|

[3.6-3.7]

|

|

String to be used to remove the veil after use

|

3.8 (0.4)

|

[3.8-3.7]

|

|

Place the veil deep within the vaginal cavity

|

0.9 (0.1)

|

[0.9-1.0]

|

|

General satisfaction

|

|

Keeping the veil into the vagina for 60 minutes

|

3.1 (0.8)

|

[3.0-3.2]

|

|

Removing the veil impregnated with genital secretions with the string

|

3.3 (0.7)

|

[3.2-3.4]

|

|

Comfort when carrying the veil

|

3.3 (1.2)

|

[3.2-3.5]

|

|

Genital pain when placing or wearing the veil

|

2.9 (1.4)

|

[2.7-3.1]

|

|

General opinion about veil-based self-sampling

|

3.1 (0.5)

|

[3.0-3.1]

|

* The scale of satisfaction was asses by a Likert scale ranging from 1 (= less favorable) to 4 (= most favorable); the results are mean ± 1 standard deviation (SD); 95% confidence intervals (CI) are given in brackets.

Prevalences of HPV detection and genotypes distribution by collection methods

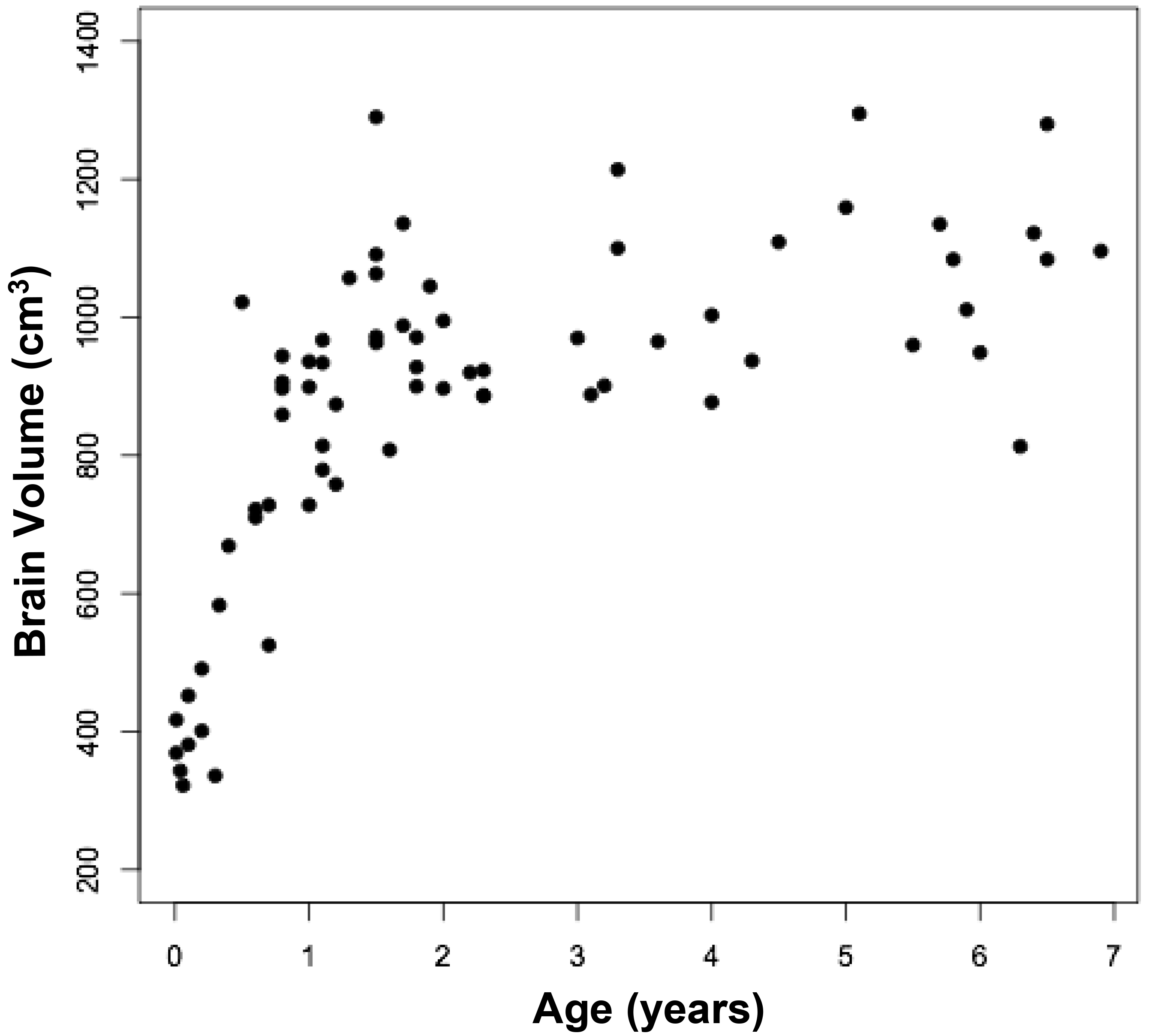

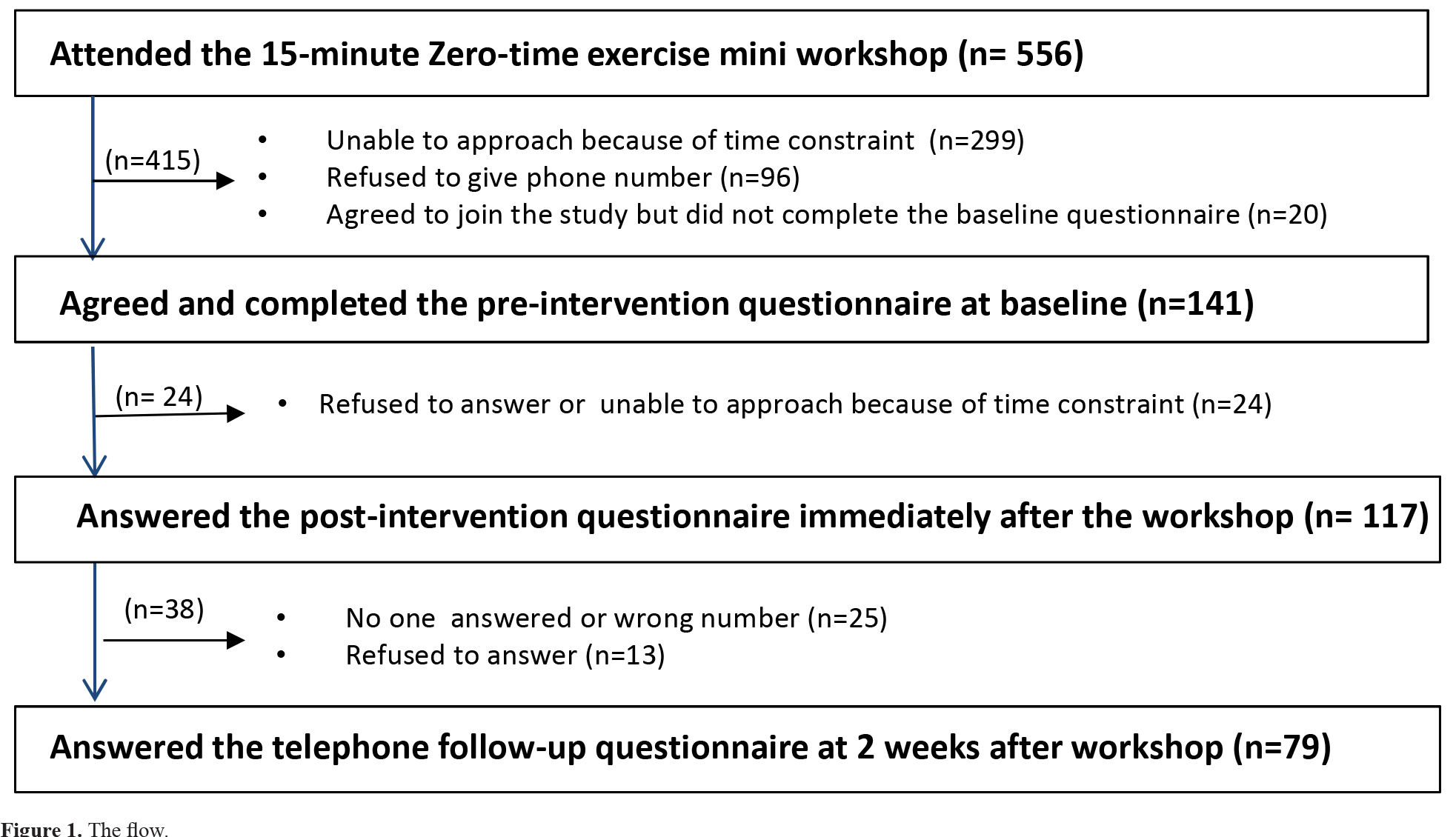

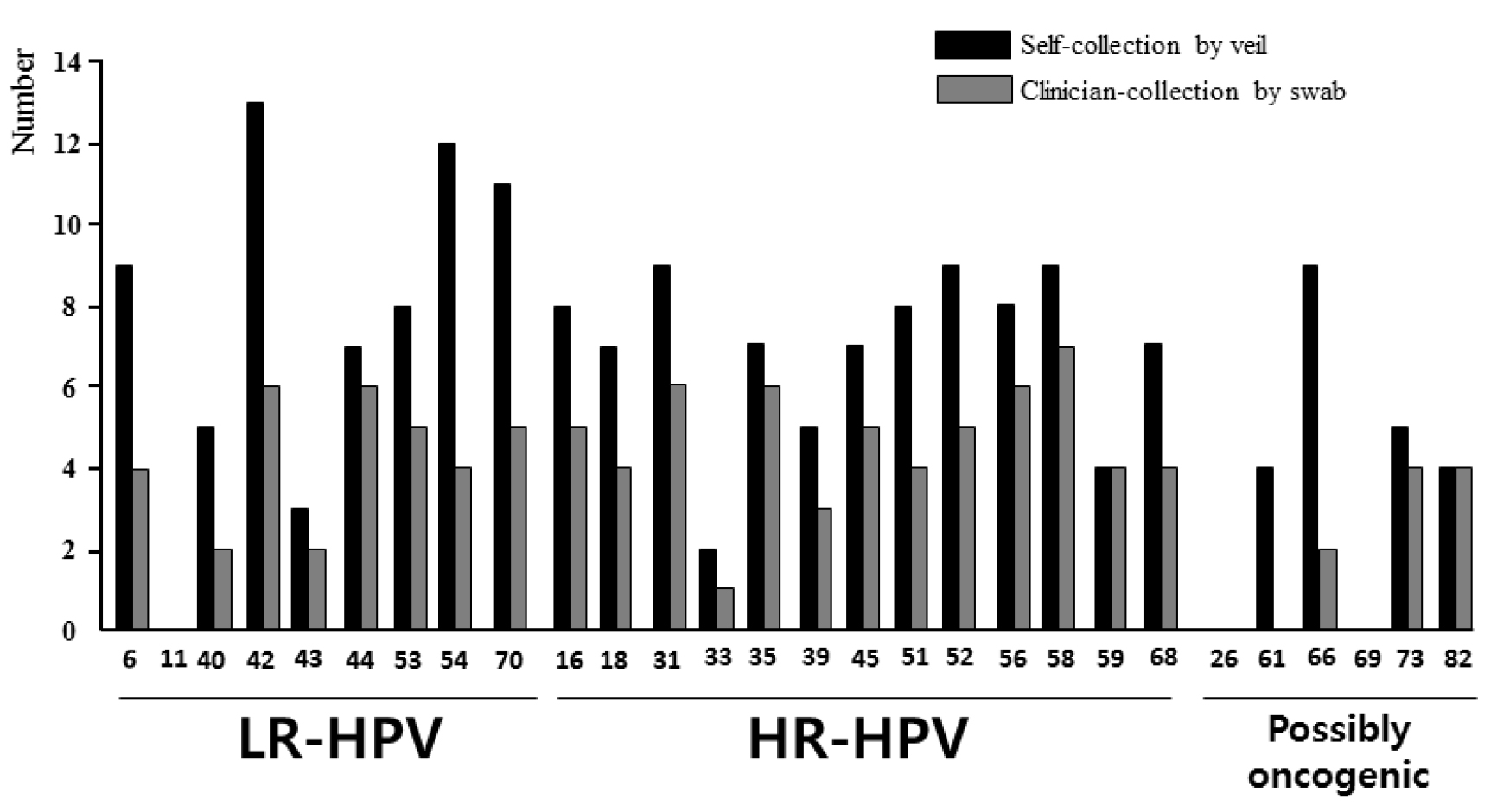

All 253 study participants had paired clinician-collected and self-collected specimens obtained for laboratory testing. All secretions from swab and veil specimens were positive for the ubiquitous b-globin gene, used as internal control of cell sampling of the Anyplex™ II HPV28 kit. Results from each of the collection method are presented in Tables 3, 4, 5 and 6 and in Figures 3, 4 and 5. Of the clinician-collected specimens included in the analysis, 58 women were positive for genital HPV DNA giving a total HPV prevalence of 22.9% (95% CI: 17.8–28.1), with 68.9% (40/58; 95% CI: 57.1–80.8) harboring cervical HR-HPV infection, providing a total HR-HPV prevalence of 15.8% (95% CI%: 11.3–20.3), as shown in the Table 3. The whole distribution of HPV genotypes in HPV-DNA positive cervical samples is detailed in the Figure 3. The Gardasil-9® vaccine HR-HPV type 58 was the predominant genotype (7/58; 12.1%), followed by the HR-HPV types 31, 35 and 56 and the LR-HPV types 42 and 44 with a prevalence of 10.3% (6/58). The 9-valent vaccine HR-HPV types 16, 45 and 52 and also the LR-HPV types 53 and 70 were present [prevalence of 8.6% (5/58)]. These HPV genotypes were followed by the HR-HPV types 18 and 51, 59 and 68 and the LR-HPV types 6 and 54 and finally the possibly oncogenic HPV types 73 and 82 with a prevalence of 6.8% (4/58). The HR-HPV-39 was present only in 3 women (5.2%) and none of the HPV positive samples was simultaneously positive for HPV-16 and HPV-18.

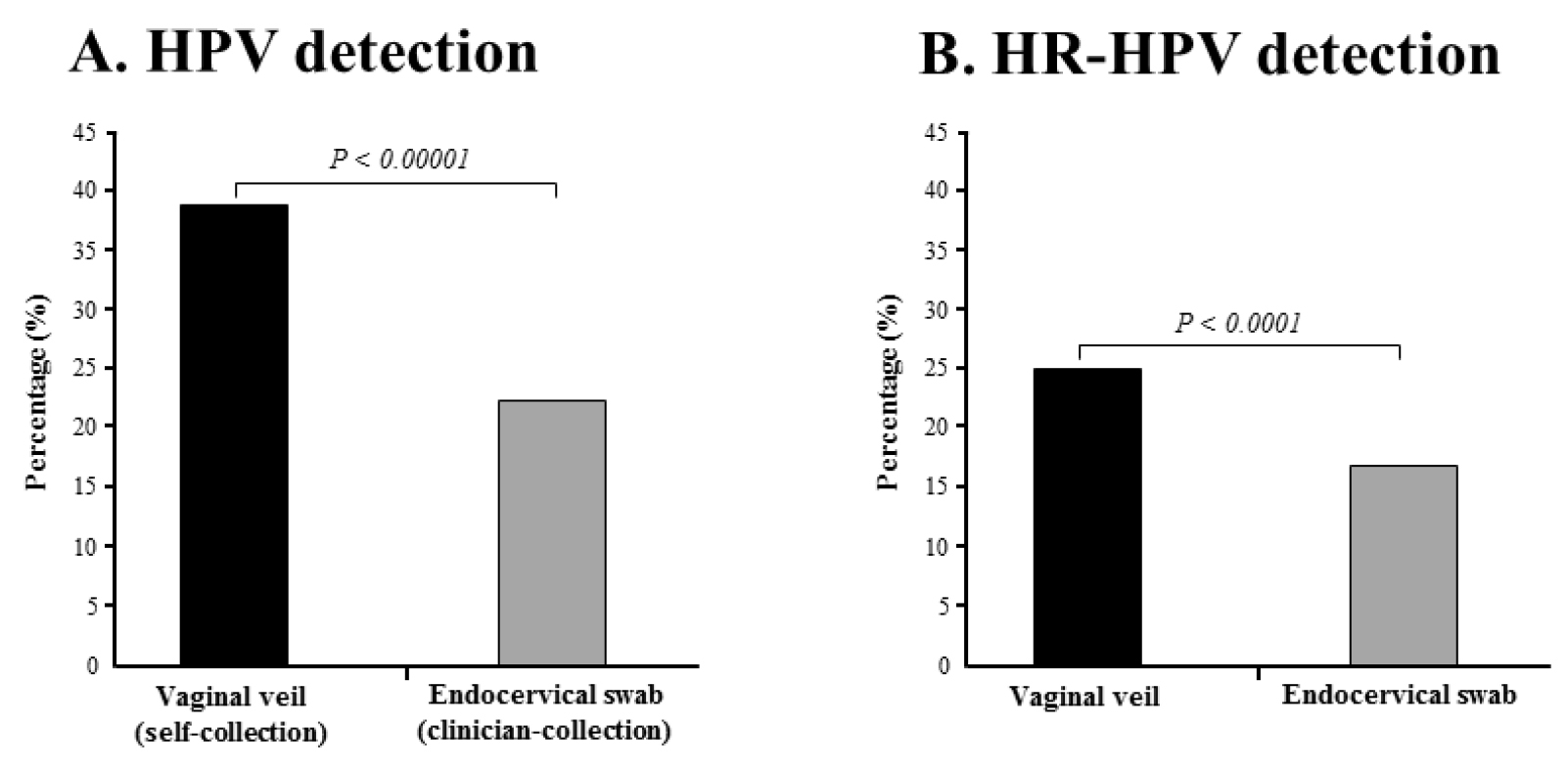

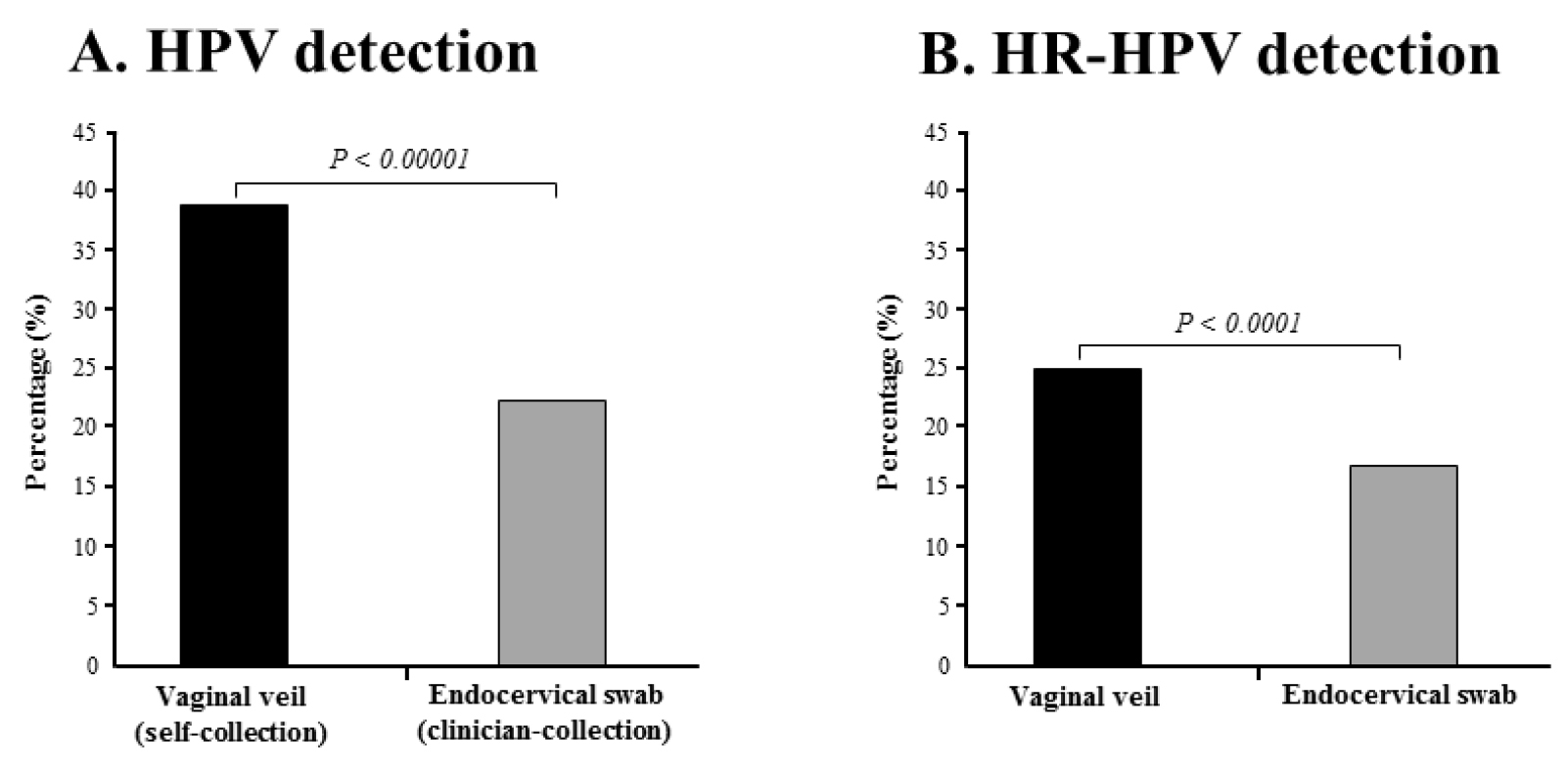

Figure 3. Percentages of detection by multiplex real-time PCR assay Anyplex™ II HPV28.

HPV DNA (A) and HR-HPV DNA (B) in paired genital secretions obtained by gold standard clinician-collected endocervical swab and by self-collection using the V-Veil-Up Gyn Collection Device (V-Veil-Up Pharma Ltd.) among 253 study women living in N’Djamena, Chad. P-values of the comparison between the two collection methods using the Mac Nemar’s test for paired data are indicate in italic.

Table 3. HPV DNA detection by clinician-collected swab and by self-collected veil among the 253 study adult women living in N’Djamena, in Chad, and included in GYNAUTO-TCHAD study.

|

|

|

Study women

(N=253)

|

|

Characteristics

|

n (%) [95%CI]*

|

|

HPV DNA detection using endocervical swab**

|

|

HPV DNA

|

58 (22.9) [17.8-28.1]

|

|

HR-HPV DNA

|

40 (15.8) [11.3-20.3]

|

|

Multiple types of any HPV among HPV-positive swabs

|

16 (27.6) [16.1–39.1]

|

|

Multiple types of HR-HPV among HR-HPV-positive swabs

|

10 (25.0) [11.6–38.4]

|

|

Any 9-valent vaccine types*** among HPV-positive swabs

|

29 (50.0) [37.1–62.9]

|

|

9-valent vaccine HR-HPV types among HR-HPV-positive swabs

|

27 (67.5) [52.9–82.1]

|

|

HPV DNA detection using self-collected veil****

|

|

HR-HPV DNA

|

97 (38.3) [32.4-44.3]

|

|

HR-HPV DNA

|

63 (24.9) [19.6-30.2]

|

|

Multiple types of any HPV among HPV-positive veils

|

42 (43.3) [33.4–53.2]

|

|

Multiple types of HR-HPV among HR-HPV-positive veils

|

16 (25.4) [14.6–36.2]

|

|

Any 9-valent vaccine types*** among HPV-positive veils

|

48 (49.5) [39.5–59.4]

|

|

9-valent vaccine HR-HPV types among HR-HPV-positive veils

|

43 (68.3) [56.8–79.7]

|

* The frequency of each variable is presented with their 95% confidence interval in brackets;

** HPV testing using endocervical secretions obtained by clinician-collected flocked swab;

*** The 9-valent Gardasil-9® vaccine (Merck & Co. Inc.) is effective against HPV genotypes 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58;

**** HPV testing using cervicovaginal fluid collected from self-administered veil (V-Veil-Up Gyn Collection Device, V-Veil-Up Pharma Ltd.) introduced within the vaginal canal during 60 minutes.

95%CI: 95% confidence interval; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus; STI: Sexual transmitted infection; HPV: Human papillomavirus; HR-HPV: High-risk human papillomavirus: SD: Standard deviation.

Of the veil-based self-collected specimens included in the analysis, 97 women showed genital shedding of HPV DNA that represented an overall HPV prevalence of 38.3% (95% CI: 32.4–44.3). Among these HPV positive women, 64.9% [(63/97); 95% CI: 55.45–74.4] were positive for HR-HPV genotypes giving a total HR-HPV prevalence of 24.9% (95% CI: 19.6–30.2) (Table 3). The whole distribution of HPV genotypes in HPV-DNA positive cervical samples collected by veil is detailed in the Figure 3. The distribution of HPV genotypes in the HPV DNA-positive women revealed that the LR-HPV genotype 42 (13/97; 13.4%) was the predominant genotype, followed by the HPV54 (12/97; 12.4%), HPV70 (11/97; 11.3%). The Gardasil-9® vaccine HR-HPV type 58, 52 and 31 were the predominant HR-HPV genotypes (9/97; 9.3%), followed by HPV16 (8/97; 8.2%), HPV18, HPV35, HPV45 and HPV68 (7/97; 7.2%), HPV39 (5/97; 5.2%) and finally HPV33 (2/97; 2.1%). The percent agreements between the two collection methods to detect any HPV, HR-HPV and 9-valent vaccine HPV genotypes were 83.0%, 89.3% and 91.7%, respectively, and all Cohen’s κ coefficients were between 0.61 to 0.80, demonstrating “good” agreement [56] (Table 4).

Table 4. Two-by-two tables of cervicovaginal specimens self-collected using the V-Veil-Up Gyn Collection Device (V-Veil-Up Pharma Ltd.) compared to clinician-collected endocervical swab specimens for the detection by multiplex real-time PCR of any HPV genotypes, HR-HPV genotypes and HPV genotypes targeted by the 9-valent Gardasil-9® vaccine (Merck & Co. Inc.).

|

|

|

Any HPV genotypes

|

|

HR-HPV

genotypes

|

|

9-valent vaccine HPV genotypes

|

|

|

|

Clinician-collected

swab specimen

|

Clinician-collected

swab specimen

|

Clinician-collected

swab specimen

|

|

|

|

Positive

(n=58)

|

Negative

(n=195)

|

Positive

(n=40)

|

Negative

(n=213)

|

Positive

(n=29)

|

Negative

(n=224)

|

|

Veil-based self-collected specimen

|

Positive

(N*=97)

|

56

|

41

|

Positive

(N***=63)

|

38

|

25

|

Positive

(N$=48)

|

28

|

20

|

|

Negative

(N**=156)

|

2

|

154

|

Negative

(N****=190)

|

2

|

188

|

Negative

(N£=205)

|

1

|

204

|

|

|

Estimate

|

95% CI

|

|

Estimate

|

95% CI

|

|

Estimate

|

95% CI

|

|

Sensitivity (%)

|

96.5

|

91.8–100.0

|

|

95.0

|

88.3–100.0

|

|

96.5

|

89.8–100.0

|

|

Specificity (%)

|

78.9

|

73.3–84.7

|

|

88.2

|

83.9–92.6

|

|

91.1

|

87.3–94.8

|

|

Agreement (%)

|

83.0%

|

|

89.3%

|

|

91.7%

|

|

Cohen’s κ coefficientµ

|

0.611

|

|

0.675

|

|

0.682

|

* : Total number of veil based-self collected specimens positive for any HPV;

** : Total number of based-self collected specimens negative for any HPV;

*** : Total number of veil based-self collected specimens positive for HR-HPV;

**** : Total number of veil based-self collected specimens negative for HR-HPV;

$ : Total number of veil based-self collected specimens positive for any HPV genotypes targeted by the 9-valent Gardasil-9® vaccine (Merck & Co. Inc.) (HPV -6, -11, -16, -18, -31, -33, -45, -52 and -58);

£ : Total number of veil based-self collected specimens negative for any HPV genotypes targeted by the 9-valent Gardasil-9® vaccine;

µ : The Cohen’s k coefficient was interpreted according the Landis and Koch scale [56]: For k value 0, the agreement is considered to be less than what would be expected by chance; for º values 0.01 0.20, only a slight agreement is present; for º values 0.21 0.40, the agreement is considered to be fair; for º values 0.41 0.60, the agreement is said to be moderate; for º values 0.61 0.80, the agreement is considered good; and finally, for º values 0.81 0.99, the agreement is said to be almost perfect.

HPV: Human papillomavirus; HR-HPV: high-risk human papillomavirus.

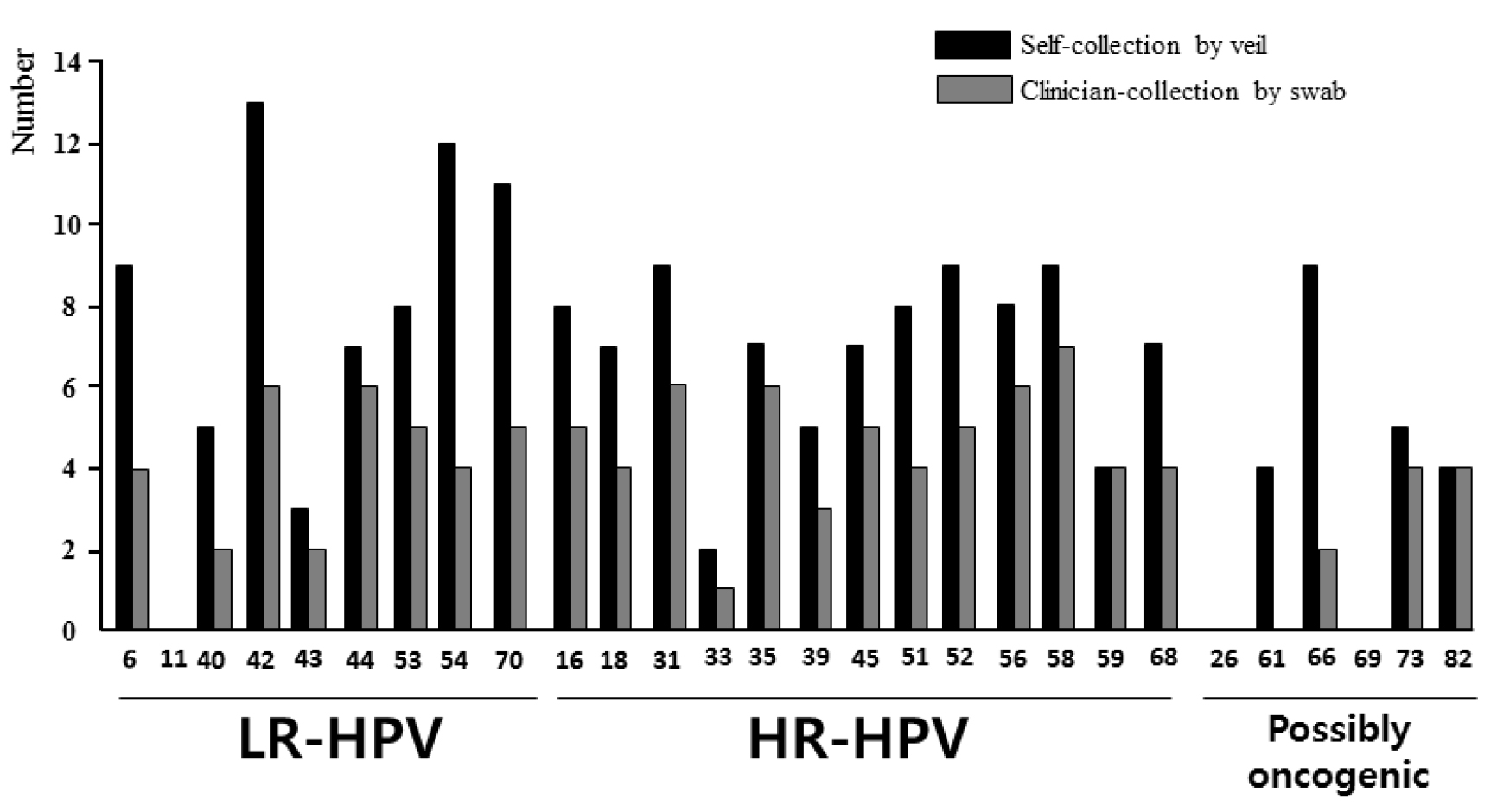

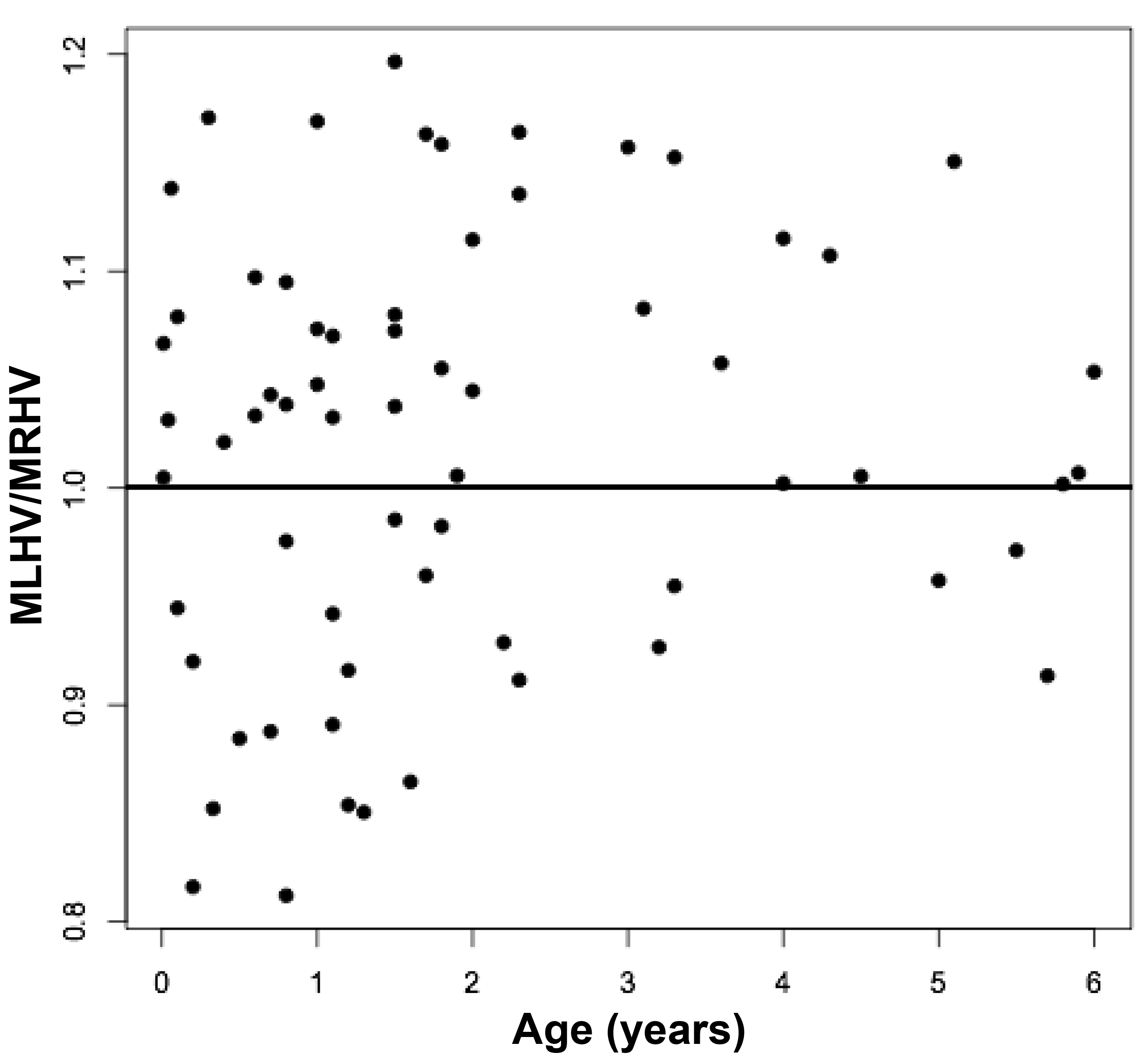

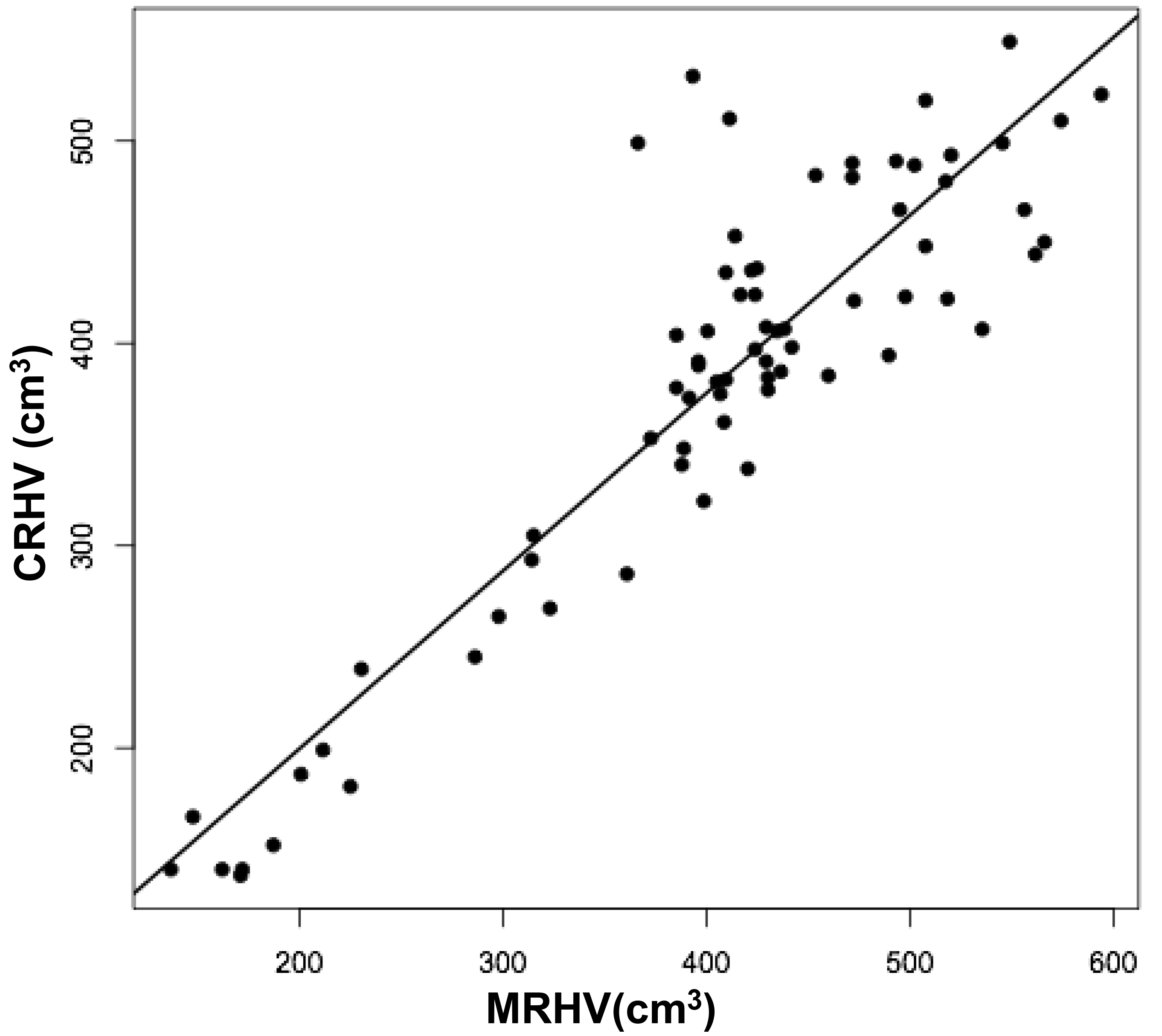

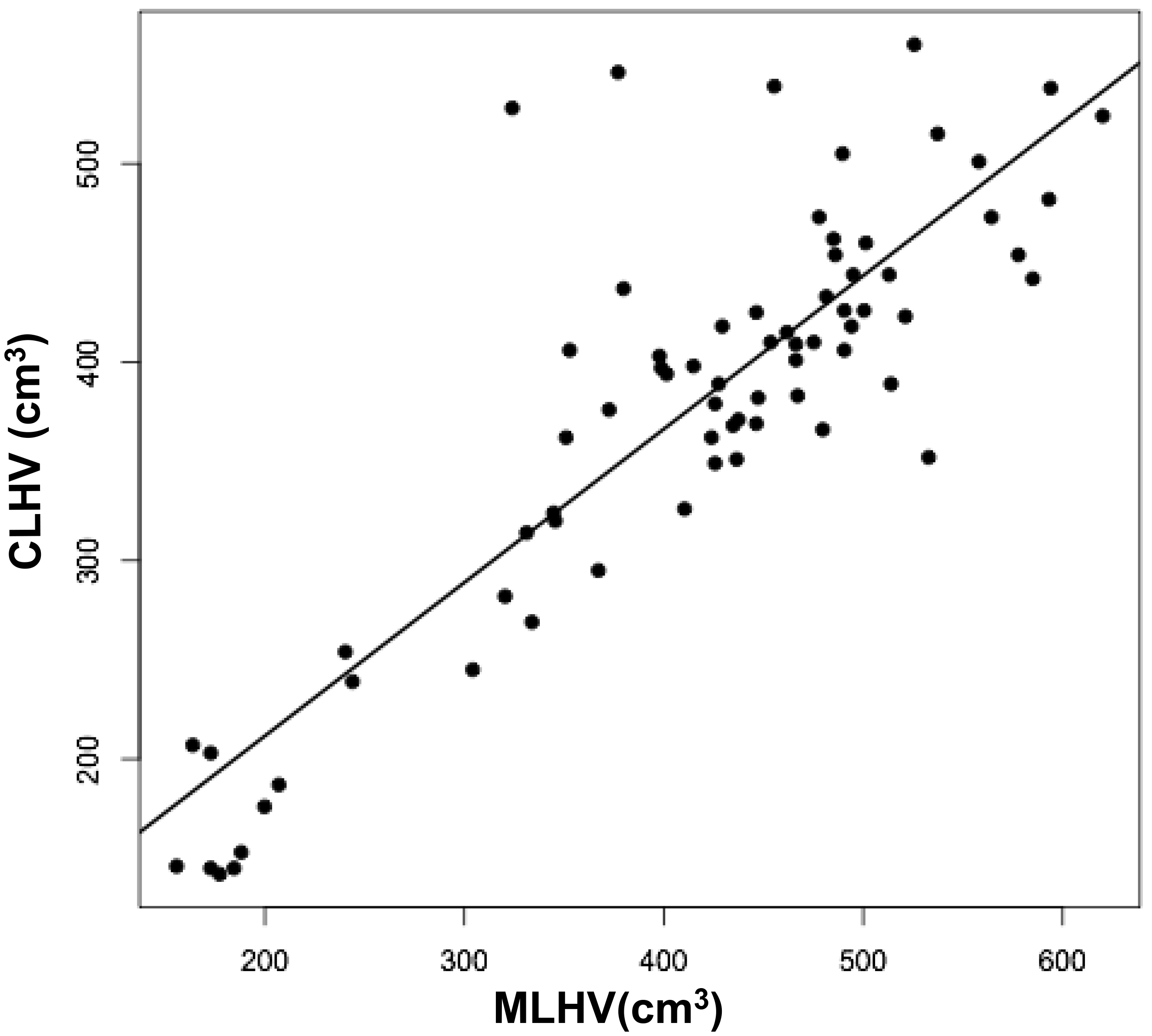

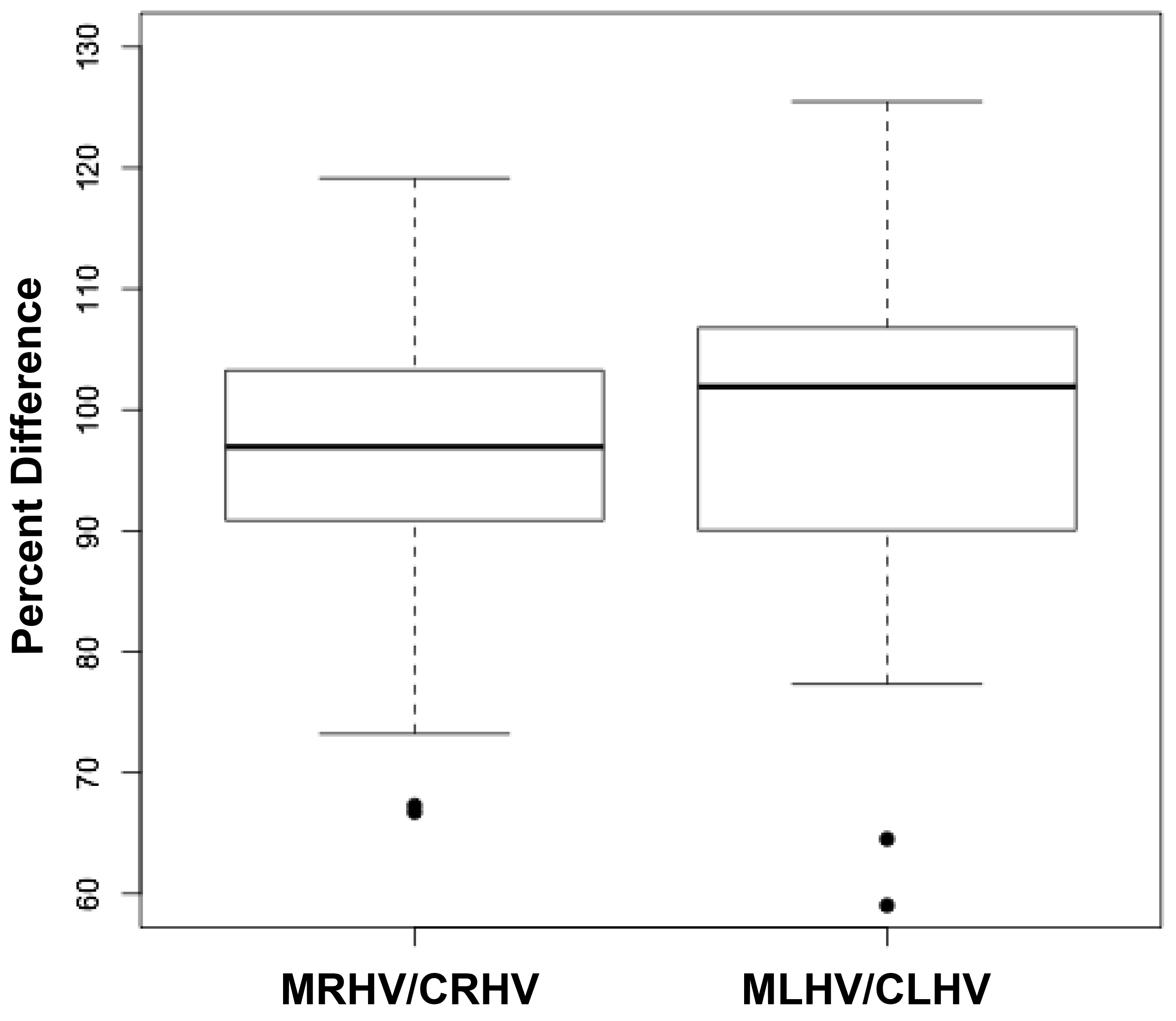

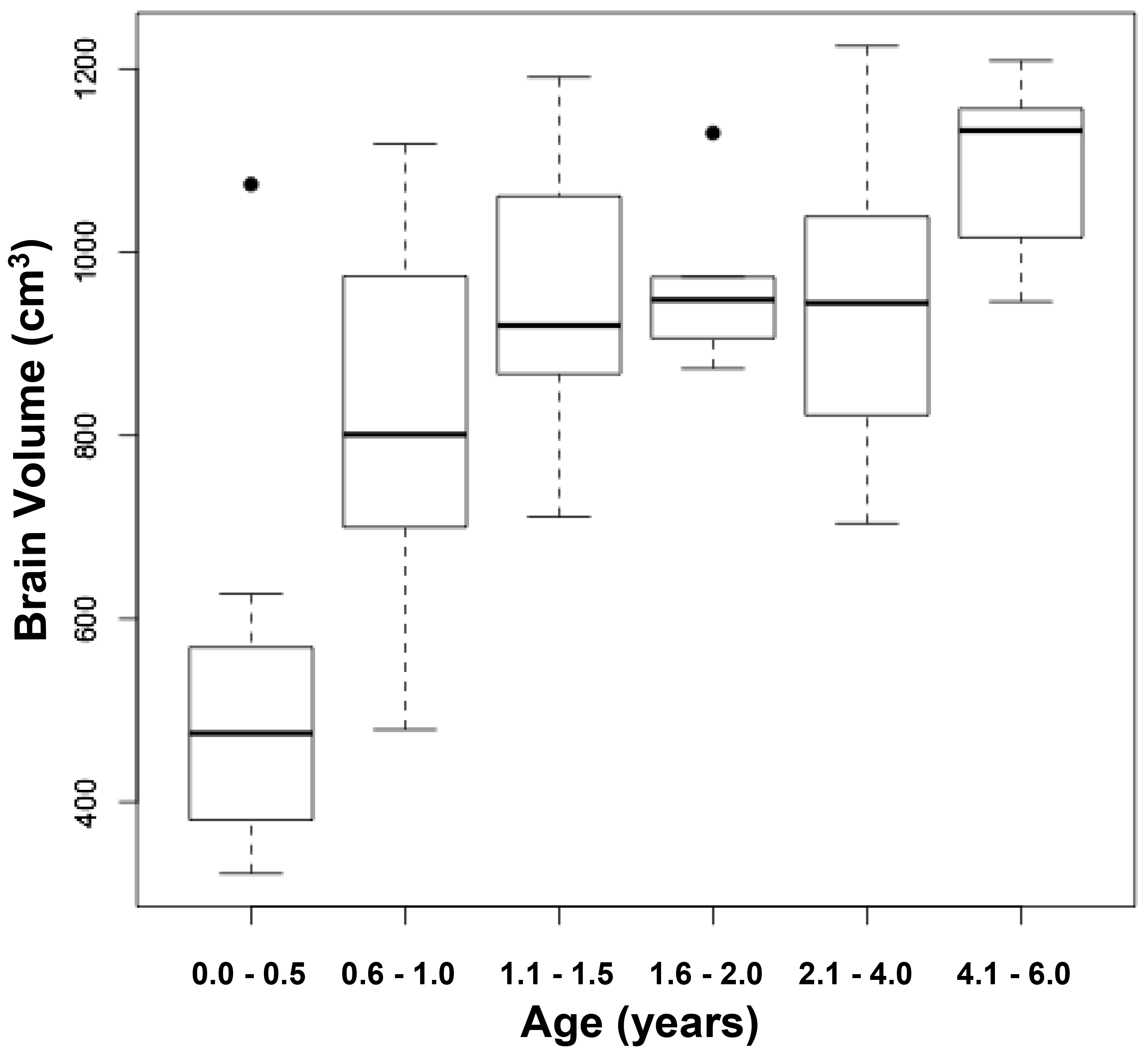

Using clinician-collected swab as the reference collection method, the sensitivities and specificities of the self-collected veil to detect HPV, HR-HPV and 9-valent vaccine HPV genotypes were 96.5% (95% CI: 91.8 – 100.0%) and 78.9% (95% CI: 73.3 – 84.7%), 95.0% (95% CI: 88.3 – 100.0%) and 88.2% (95% CI: 83.9 – 92.6%), and 96.5% (95% CI: 89.8 – 100.0%) and 91.1% (95% CI: 87.3 – 94.8%), respectively (Table 4). Overall, the percentage of test positivity for HPV DNA was 1.67-fold higher in self-collected specimens than in clinician-collected specimens (38.3% versus 22.9%; P-value < 0.00001) (Figure 3A). The percentage of test positivity for HR-HPV DNA was 1.57-fold higher in self-collected specimens than in clinician-collected specimens (24.9% versus 15.8%; P-value < 0.0001) (Figure 3B). When considering the distribution of the 28 HPV genotypes detected by multiplex real-time PCR assay Anyplex™ II HPV28 detected in paired genital specimens, all genotypes but two (HPV-59 and HPV-82), were more frequently detected by self-collection using the V-Veil-Up Gyn Collection Device than by clinician-collected endocervical swab (Figure 4).

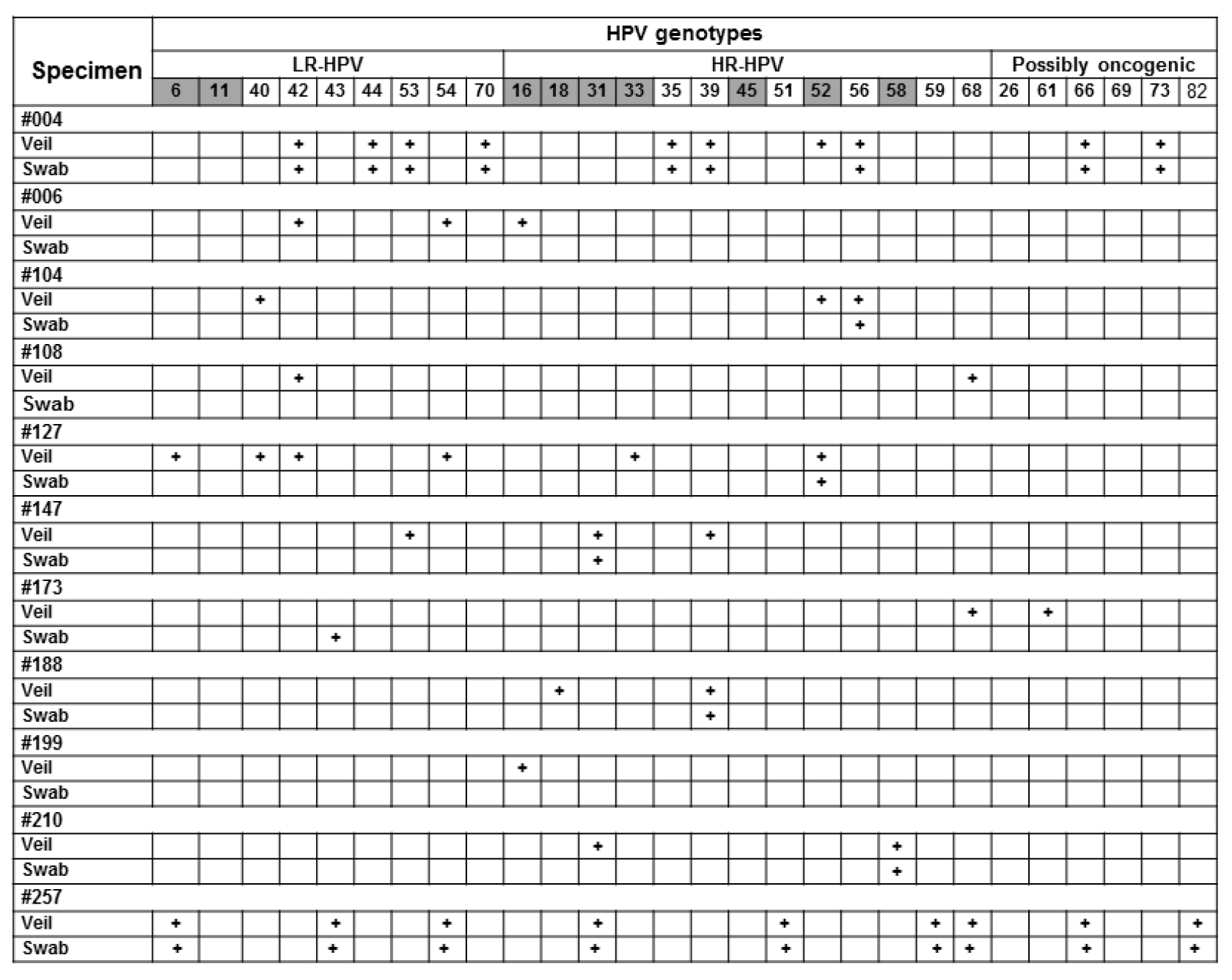

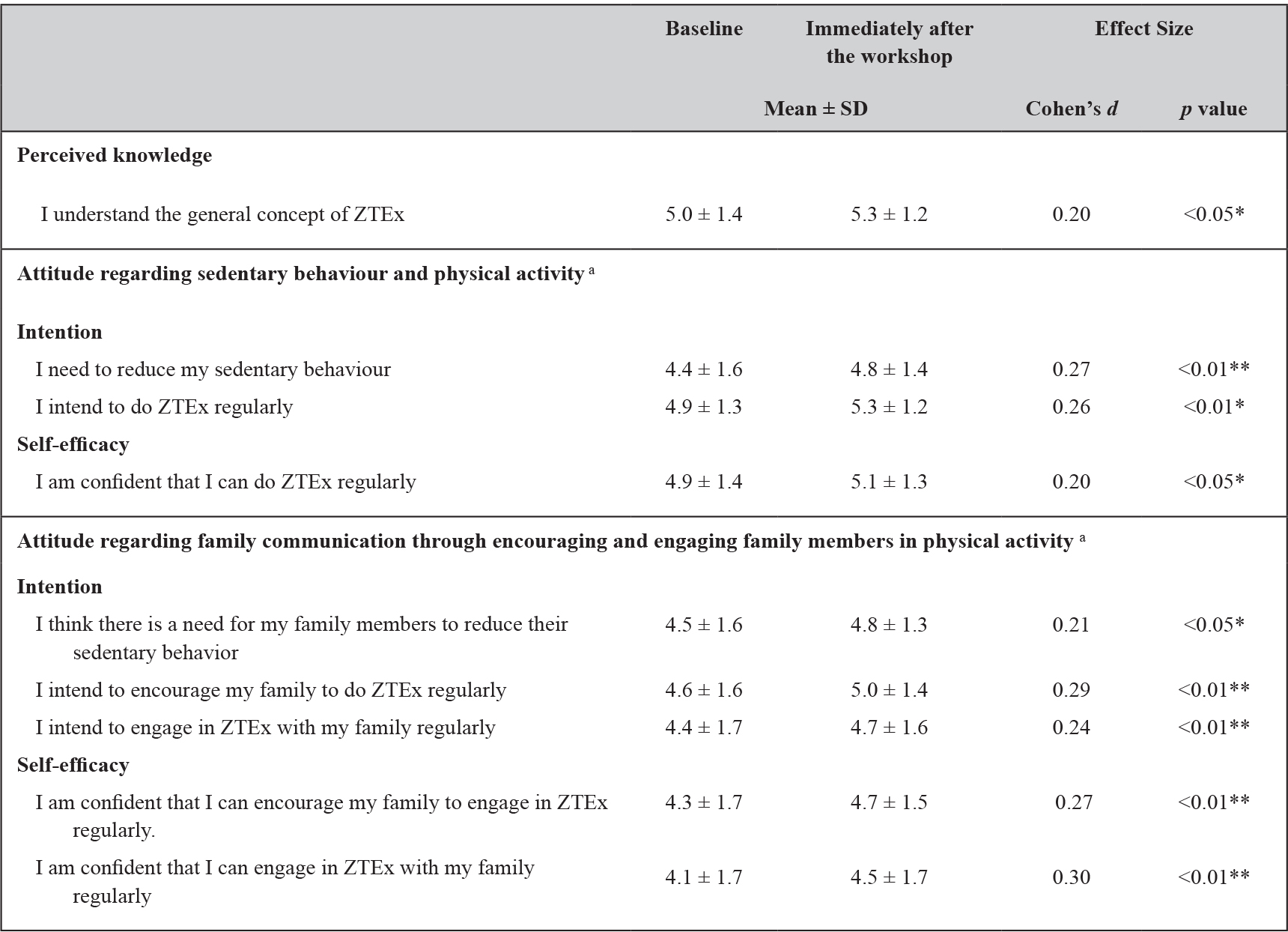

Figure 4. Distribution of the 28 HPV genotypes detected by multiplex real-time PCR assay Anyplex™ II HPV28.

The HPV DNA detection was carried out in paired genital secretions obtained by clinician-collected endocervical swab and by self-collection using the V-Veil-Up Gyn Collection Device (V-Veil-Up Pharma Ltd.) among 253 study women living in N’Djamena, Chad. LR-HPV: Low risk- human papillomavirus; HR-HPV: High-risk human papillomavirus.

The 28 HPV genotypes detected by the Anyplex™ II HPV28 kit include 9 low-risk types (LR-HPV), 13 high-risk types (HR-HPV) and 6 genotypes classified as possibly carcinogenic. The HPV genotypes -6, -11, -16, -18, -31, -33, -45, -52 and -58 which are targeted by the 9-valent Gardasil-9® vaccine (Merck & Co. Inc.) are highlighted in grey.

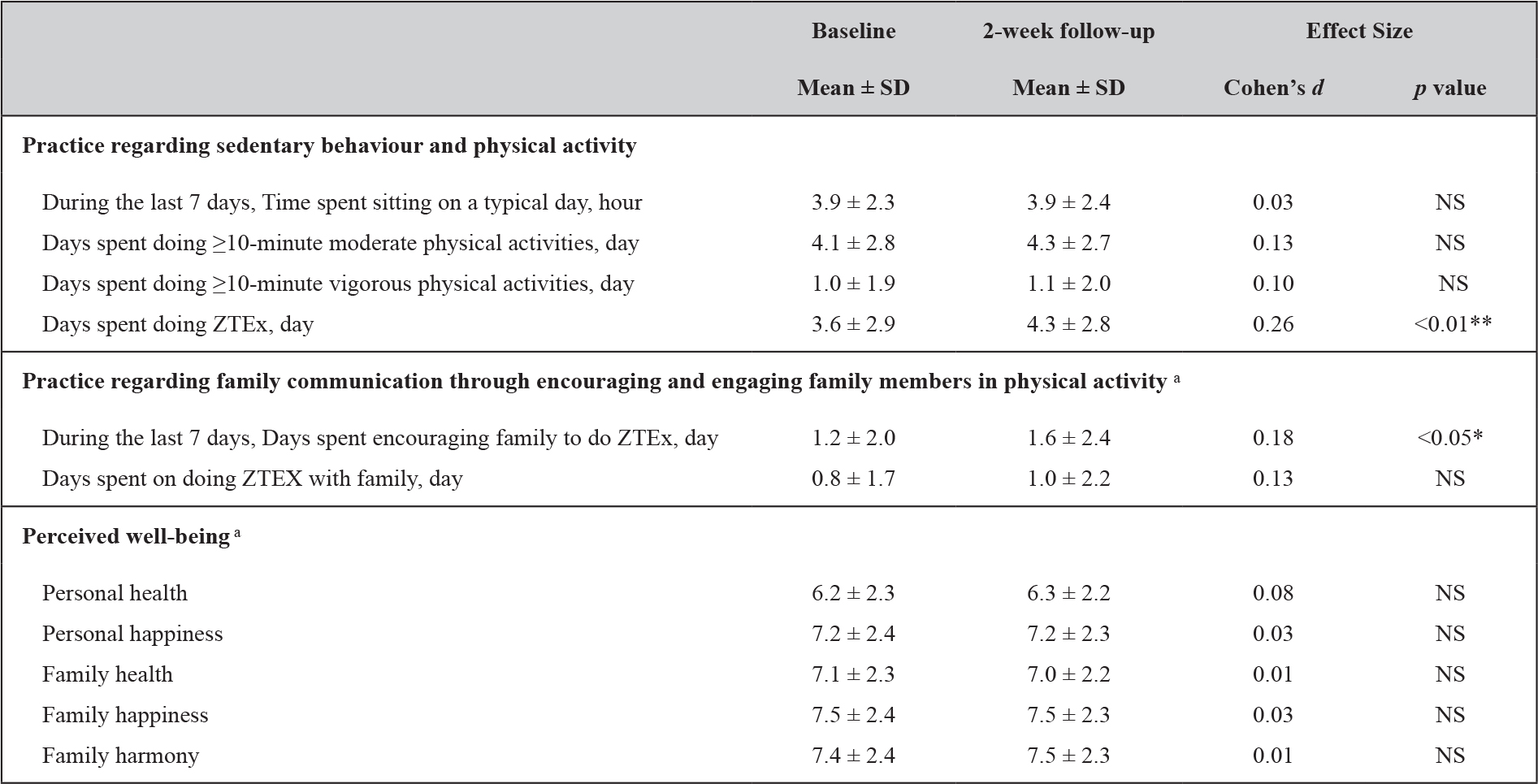

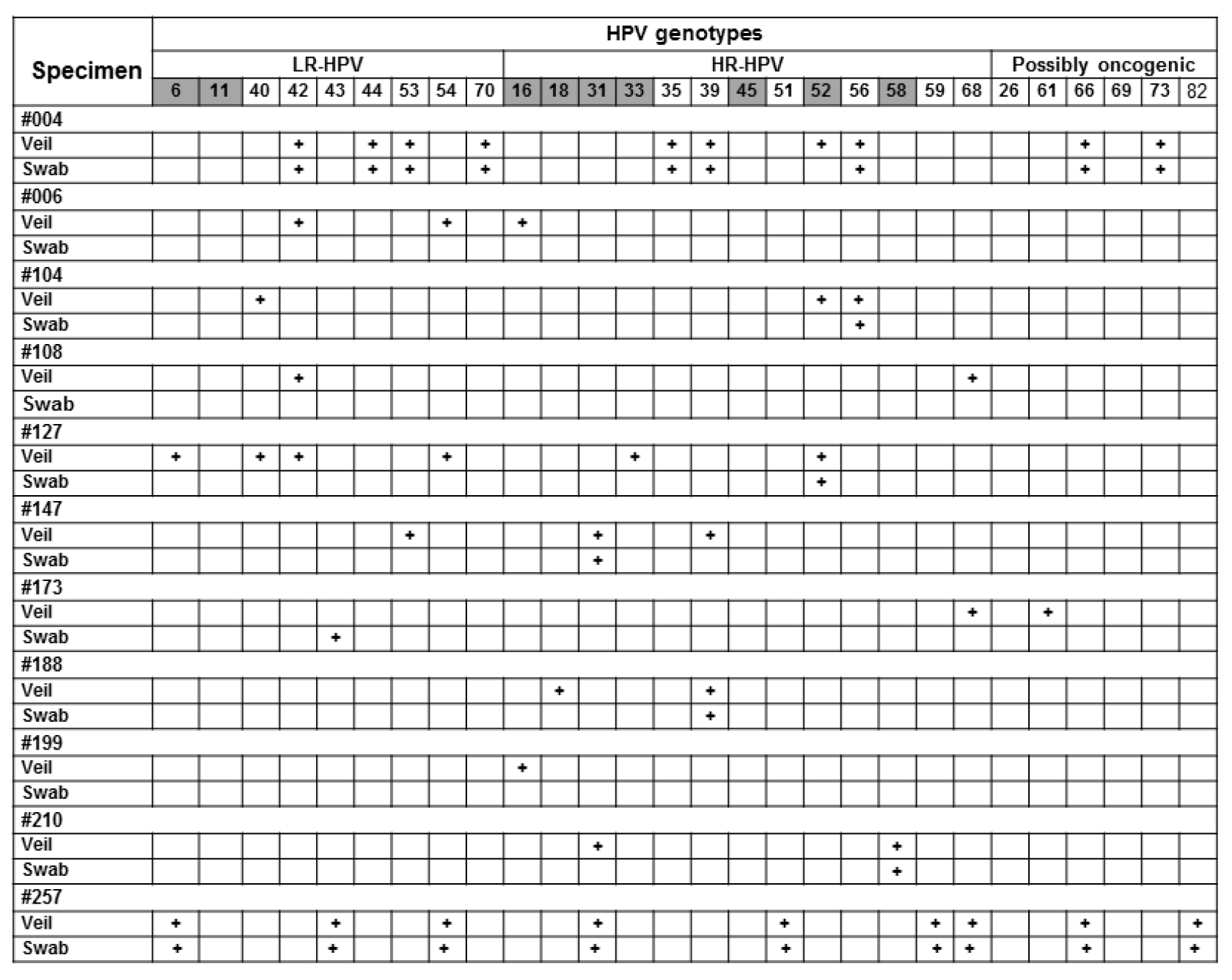

Among the 253 study participants, the mean numbers (± 1 SD) of HPV and HR-HPV detected when using the self-collected veil [1.84±0.96 (range, 1–10) and 1.43±0.64 (range, 1–5), respectively] were similar to those obtained when using the swab-collection [1.79±1.14 (range, 1–9) and 1.5±0.75 (range: 1–5), respectively]. The differential efficiency of detecting HPV and HR-HPV between the two collection methods was better evidenced when considering paired results by genotype. Thus, the correspondence between the 7,084 (=253 x 28) results obtained from the 253 paired swab-collected and veil-collected genital specimens to detect the 28 HPV genotypes included in Anyplex™ II HPV28 kit was further analyzed, genotype by genotype, and depicted in Table 5. The use of self-collection by veil allowed detecting 101 (84+17) additional HPV of all types by reference to the use of swab in 89 (35.2%) participants, while the use of swab allowed detecting only 7 additional HPV in 7 participants (2.8%) by comparison to the use of veil. When considering only the correspondence between the 3,289 (=253 × 13) paired results for oncogenic HR-HPV (Table 6), the use of veil allowed detecting 38 (34+4) additional HR-HPV in 35 (13.8%) study women, while the use of swab allowed detecting only 3 additional HPV in 3 participants (1.2%) by comparison to the use of veil. The Figure 5 depicts some relevant examples of paired results obtained by clinician-collected endocervical swab and self-collected veil using the multiplex real-time PCR assay Anyplex™ II HPV28, showing the capacity of the veil to allow the detection of oncogenic HR-HPV that could not be detected from the paired swab specimens. Finally, genital infections with multiple HPV genotypes were more frequently detected using the veil collection device than swab collection [43.3% (42/97); 95% CI: 33.4–53.2 versus 27.6% (16/58); 95% CI: 16.1–39.1; P < 0.001], while the mean number of HR-HPV detected using positive genital secretions collected by veil was quite similar to that of cervical secretions collected by swab [1.7 HR-HPV genotypes (range, 1 to 5) versus 2.3 HR-HPV (range, 1 to 5)].

Table 5. Correspondence between the 7,084 (= 253 × 28) results obtained from the 253 paired swab-collected and veil-collected genital specimens to detect the 28 HPV genotypes included in Anyplex™ II HPV28 kit (Seegene).

|

|

|

LR-HPV

|

HR-HPV

|

Possibly oncogenic

|

|

|

|

|

6

|

11

|

40

|

42

|

43

|

44

|

53

|

54

|

70

|

16

|

18

|

31

|

33

|

35

|

39

|

45

|

51

|

52

|

56

|

58

|

59

|

68

|

26

|

61

|

66

|

69

|

73

|

82

|

|

|

Swab

|

Veil

|

Number of cases per genotype

|

Total

|

|

Negative

|

Negative

|

244

|

253

|

248

|

240

|

248

|

244

|

245

|

241

|

242

|

244

|

246

|

244

|

250

|

246

|

248

|

246

|

245

|

244

|

244

|

244

|

249

|

245

|

253

|

249

|

244

|

253

|

248

|

249

|

6,891

|

|

Positive

|

Positive with same genotype*

|

4

|

0

|

2

|

6

|

0

|

4

|

5

|

4

|

5

|

4

|

4

|

6

|

0

|

6

|

3

|

5

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

7

|

4

|

3

|

0

|

0

|

2

|

0

|

4

|

4

|

97

|

|

Positive

|

Positive with different genotypes **,a

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1b

|

2c

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1d

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

4

|

|

Negative

|

Positive

|

5

|

0

|

3

|

7

|

3

|

3

|

3

|

8

|

6

|

4

|

3

|

3

|

2

|

1

|

2

|

2

|

4

|

4

|

3

|

2

|

0

|

4

|

0

|

4

|

7

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

84

|

|

Positive

|

Negative

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

2

|

2

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

7

|

* i.e., positivity using veil for the same HR-HPV genotype using swab;

** i.e., positivity using veil for at least one another HR-HPV genotype using swab;

a A total of 17 additional HPV genotypes were detected using veil collection;

b Additional HPV genotypes detected using veil collection were HPV -16, -52, -53, -54, -70 and -73;

c Additional HPV genotypes detected using veil collection were HPV -43 and -54;

d Additional HPV genotypes detected using veil collection were HPV -6, -31, -43, -51, -54, -59, -66, -68 and -66.

NA: Not attributable; HPV: Human papillomavirus; HR-HPV: high-risk human papillomavirus; LR-HPV: low-risk human papillomavirus.

Figure 5. Relevant examples of paired results obtained by gold standard clinician-collected endocervical swab and self-collected veil.

Participants #006, #108, #199 and #257 were negative by clinician-collected swab, whereas they were positive by paired self-collected veil, with supplementary detection by veil of oncogenic HR-HPV, including HPV-16 in #006 and #199, HPV-68 in #108, and HPV-31, HPV-51 and HPV-68 in #257. Participants #004, #104, #127, #147, #173, #188 and #210 were positive by clinician-collected swab, and paired self-collected veil allowed supplementary detection of several oncogenic HR-HPV (HPV-18 in #188; HPV-31 in #210; HPV-33 in #127, HPV-39 in #147, HPV-52 in #004 and #104; HPV-68 in #173). Interestingly, all positive HR-HPV detections by clinician-collected swab were also detected by self-collected veil. Positive result for a given genotype is indicated by cross; negative result by white box. All swab and veil specimen were positive for b-globin internal control of the Anyplex™ II HPV28 kit (not shown).

Table 6. Correspondence between the 3,289 (= 253 × 13) results obtained from the 253 paired swab-collected and veil-collected genital specimens to detect the 13 HR-HPV genotypes included in Anyplex™ II HPV28 kit (Seegene).

|

|

|

HR-HPV genotypes

|

|

|

|

|

16

|

18

|

31

|

33

|

35

|

39

|

45

|

51

|

52

|

56

|

58

|

59

|

68

|

|

|

Swab

|

Veil

|

Number of cases per genotype

|

Total

|

|

Negative

|

Negative

|

244

|

246

|

244

|

250

|

246

|

248

|

246

|

245

|

244

|

244

|

244

|

249

|

245

|

3,195

|

|

Positive

|

Positive with same genotype*

|

4

|

4

|

6

|

0

|

6

|

3

|

5

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

7

|

4

|

3

|

57

|

|

Positive

|

Positive with different genotypes**,a

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1b

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

|

Negative

|

Positive

|

4

|

3

|

3

|

2

|

1

|

2

|

2

|

4

|

4

|

3

|

2

|

0

|

4

|

34

|

|

Positive

|

Negative

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

3

|

* i.e., positivity using veil for the same HR-HPV genotype using swab;

** i.e., positivity using veil for at least one another HR-HPV genotype using swab;

a A total of 4 additional HR-HPV genotypes were detected using veil collection;

b Additional HR-HPV genotype detected using veil collection was HR-HPV -31, -51, -59 and -68.

NA: Not attributable; HPV: Human papillomavirus; HR-HPV: high-risk human papillomavirus.

Discussion

In the present study, the acceptability and HPV DNA diagnostic accuracy of a novel genital veil (V-Veil-Up Gyn Collection Device) was assessed as female genital self-sampling device to collect cervicovaginal secretions. Interestingly, all specimens collected by the veil were found positive for the ubiquitous b-globin gene, demonstrating that they contained cellular DNA, which made HPV detection possible by molecular testing. The results showed high acceptability (96%), feasibility and satisfaction of the veil-based genital self-collection, which was non-inferior to clinician-based collection as reference for HPV DNA molecular testing, with “good” agreement between the two collection methods, high sensitivity of 95.0% and specificity of 88.2%. Outstandingly, the rates of HPV DNA and HR-HPV DNA positivities were significantly higher when using veil-based collected genital secretions than clinician-collected cervical secretions by swab. The self-collection by veil allows detecting 12.7-fold more additional oncogenic HR-HPV in 1 of 8 (12.5%) participants than the detection allowed by the swab-based collection, likely originating from non-cervical areas of the vaginal cavity, including vaginal cul-de-sacs, vaginal walls and vulva. Taken together, our observations highlight that veil-based self-collection of genital secretions appears a convenient tool to collect in a gentle way genital secretions for accurate molecular HPV detection and genotyping that could be easily implemented in the cervical cancer prevention program in Chad.

Most previous studies conducted in sub-Saharan African countries depict high HR-HPV prevalences and wide heterogeneity in the distribution of the main HR-HPV in women [59–62, 65–79]. Our observations confirm that women living in Chad also form a neglected high-risk group for cervical HR-HPV infection and consequently for cervical cancer. The very high prevalence of cervical HR-HPV in adult women clearly demonstrates that cervical HR-HPV infection in Chad constitutes a major public health problem, which remains largely unsuspected. Therefore, there is an urgent need for implementing a cervical cancer prevention program in Chad, as recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) [80]. According to Mortier and colleagues, the cytology-based cervical cancer screening in women in Chad is feasible with low cost and easy to interpret visual technics; and could be integrated in existing healthcare structures [40]. For these women carrying cervical HR-HPV infection, only secondary prevention with regular screening for precancerous lesions by cytology and the monitoring of the viral persistence by HPV molecular testing, remains the only alternative to prevent the disease progression into invasive cervical cancer. However, in the context of Chad, a very low-income country, there is a serious lack of pathologist specialists, thereby making conventional cytology not suitable and reinforcing on the other hand the great necessity to implement HPV DNA testing with molecular technologies [7]. Indeed, HPV DNA testing constitutes an alternative to cytology for cervical cancer screening, which is furthermore highly sensitive and reproducible [7]. HPV DNA molecular testing could promote the “screen-and-treat” strategy recommended by the WHO to prevent cervical cancer in developing countries [80], thus allowing to maximize the medical support in a single visit and avoiding the loss of women positive for HR-HPV.

Taking into account that most adult Chadian women are living in remote rural areas, or far away of adequate healthcare facilities, self-collection of genital specimen carried out at home by women themselves could represent a relevant alternative allowing increasing the coverage of screening when coupled with adapted HPV DNA testing by molecular biology [7]. In the GYNAUTO-CHAD study, we have had the opportunity to evaluate the acceptability and HPV DNA diagnostic accuracy of a novel genital veil (V-Veil-Up Gyn Collection Device) as female genital self-sampling device to collect cervicovaginal secretions, previously found accurate for the molecular detection of cervicovaginal bacterial infections [45]. Veil-based self-collection proved to be a particularly well acceptable method easily collecting genital secretions within our cohort of community-recruited adult Chadian women. Thus, the veil was in the vast majority of participants (97.6%) correctly placed with the applicator and removed with the string, without any difficulties. When asked to choose one collection method, the vast majority (96.0%) of study women responded that they would prefer the self-collection method, demonstrating high acceptability of the genital sampling using the V-Veil-Up sampler device. Although most women (91.3%) reported that the instructions for use in French were easy to read and to understand, with correct recognizing of the component’s device, the verbal explanations by the nurse on how to use the collection device were better appreciated, particularly to correctly interpret the schemas of the instructions for use, and how placing the veil deep within the vaginal cavity. These observations are in keeping with the frequent ignorance of female genital anatomy in study participants (not shown), who were not generally taking any birth control method, and were not using tampons for feminine hygiene during menstruation. However, in practice, the manipulation of the veil was almost correct, perhaps in relationship with the very frequent usage of genital toilet in study women. Thus, while the majority of participants were not already familiar with using tampons (only 13% in our study population), the genital manipulations during veil-based self-collection were easy to carry out, which might lead to greater preference for the veil much over than other unfamiliar methods, such as a brush or a swab. These findings are reminiscent to the high acceptability of the use of vaginal tampons for self-collection reported in African women living in South Africa [13, 30]. These observations suggest that a large proportion of African women might actually prefer self-collection methods not necessitating good knowledge of the female genital anatomy to other self-collection methods such as brush or swab, for which the women must specifically target their cervix. Furthermore, the answers of study participants demonstrated high satisfaction of the V-Veil-Up Gyn Collection Device. Thus, very few women reported difficulties when performing the veil-based collection and nearly all women reported positive experiences with collection. Only a minority (4.7%) of participants reported some difficulties with performing the self-collection, most frequently genital pain when placing or wearing the veil in a minority of women (3.9%), all being more than 45 years-old, likely because of vaginal dryness in women being in the menopause period.

Otherwise, our observations also point the potential interest of using a supervised self-collection strategy among African women, in which oral counselling processes are aided at all times by a healthcare or non-healthcare professional as a counsellor to understand the instructions for use, the genital anatomy, and provide counselling with a very high rate of acceptability and satisfaction of self-collection. The evidence of high acceptability for supervised strategies was previously reported for another self-collection of capillary blood or saliva during HIV self-testing, especially in resource-constrained settings [81]. Other advantages of veil are that it is inexpensive and easily accessible. Finally, providing options for self-collection based upon women’s preferences is likely to increase screening coverage, and our data suggest that veil is an acceptable option. The percent agreements between clinician-based collection and veil-based self-collection to detect any HPV, HR-HPV and 9-valent vaccine HPV genotypes were above 80%, and all Cohen’s κ coefficients were between 0.61 to 0.80 demonstrating “good” agreement between collection methods [63]. Although it exists no data on the performance of self-collected specimens by veil for HPV DNA testing for which to compare our results, several previous reports evaluating the use of self-collection by vaginal tampons and vaginal lavages for HPV DNA or HR-HPV mRNA may be useful to contextualize our results, since tampons and lavage as well as veil do not target particularly the cervix but are the reflect of the whole secretions of the vaginal cavity [82]. Thus, our findings of agreement between the two collection methods with the kappa-statistic are relatively similar to previous reports evaluating HR-HPV DNA detection by self-collection using vaginal tampons with clinician-collection as reference, with Cohen’s κ coefficients ranging from 0.49 [83], 0.55 [84], 0.50 [12], 0.63 [49], 0.70 [85], 0.75 [84] to 0.76 [86] or vaginal lavage with Cohen’s κ coefficients ranging from 0.47 [18], 0.53 [18], 0.64 [87], 0.65 [88], 0.71 [89] to 0.78 [88], thus indicating “moderate” to “good” agreements [63]. Similarly, the performances of HR-HPV mRNA testing using self-collected vaginal tampons by reference to clinician-collected specimens, with Cohen’s κ coefficient of 0.54 indicating “moderate” agreement [30], were slightly below to the agreement of the veil.

Out of 40 HR-HPV-positive clinician-collected specimens, 38 veil-collected specimens were also positive for HR-HPV, corresponding to a sensitivity of 95.0%. Using vaginal tampon, Adamson and colleagues reported much lower sensitivity of 77.4% of vaginal tampons to detect HR-HPV mRNA by reference to clinician collection by swab [30]. A wide range of sensitivities of tampon collection using clinician-collection as the reference were reported to detect HR-HPV DNA, ranging from 59% to 94% [12, 21, 23, 84, 90–94] and always lower than the sensitivity of the veil observed in our hands. Similarly, the reported sensitivities of vaginal lavage to detect HR-HPV ranged from 88% to 90% [88]. It remains unclear whether these differences are due to different duration of collection time, different order of specimen collection, or whether they reflect the differences in testing methods. One reason for the lower sensitivity of the tampon-based collection might be due to sampling location. The clinician-collected specimen, obtained directly from the cervix, preferentially collects cervical cells in the transformation zone, whereas the tampon-method provides a mix of cells from both the cervix and vagina, and therefore might not collect enough cells from the transformation zone [82]. In contrast, the high sensitivity with the veil to detect cervical HR-HPV demonstrates that the veil likely retains significant amount cells originating from the cervix and more than a simple vaginal tampon. It is possible that extending the time of holding the veil might increase the sensitivity, but it also might lead to decreased acceptability [21]. Finally, it is important to note that the reported sensitivities of self-sampling by vaginal tampons in addition with our own sensitivity with the veil are only for molecular detection of HPV, since no pathological data were recorded to predict dysplastic or pre-invasive lesions such as CIN 2+.

Likewise, of the 213 clinician-collected specimens negative for HR-HPV DNA, 188 veil-collected specimens were also negative for HR-HPV DNA, corresponding to a specificity of 88.2%. The specificity of the veil is of the same order to those previously reported for self-collection to detect cervical HR-HPV DNA by vaginal tampons, ranging from 80% to 92% [12, 21, 84, 90, 91], but higher than that previously reported for self-collection by tampons to detect cervical HR-HPV mRNA (77.7%) [30]. The difference in sampling location between the clinician-based collection using swab targeting the endocervix and the self-collection by veil or tampons collecting global cervicovaginal secretions might explained the higher rate of positive results by veil or tampons than by swab, since the veil as well as vaginal tampons might have picked up vulvovaginal HPV infections, which do not necessarily coincide with cervical infections [82, 94].

Because clinical management and research usually depend on single-point detection of HPV, it is important to use the collection method the most capable to detect HPV by molecular biology. The cumulative presence of HPV in female genital tract is always greater than its point prevalence, suggesting that single-point sampling is less than 100% sensitive [49]. Otherwise, the vaginal epithelium represents a much greater surface area than the cervical epithelium and as such offers a greater number of potentially HPV-infected cells to collect. Thus, the self-sampling approach using veil might not only sample the cervix, but it will also sample the vaginal epithelium, with a potentially greater likelihood of detecting HPV. Indeed, vaginal epitheliums together with the cervix epithelium provides a potentially higher number of HPV-infected cells than the cervix alone. Remarkably, in the present study, the percentages of test positivity for HPV DNA and HR-HPV DNA were 1.67-fold and 1.57-fold higher, respectively, in self-collected specimens by veil than in clinician-collected specimens. Furthermore, when considering the distribution of the 28 HPV genotypes detected by multiplex real-time PCR assay Anyplex™ II HPV28 in paired genital specimens, the vast majority (92.8%) of genotypes were more frequently detected by self-collection using the V-Veil-Up Gyn Collection Device than by clinician-collected endocervical swab. In more than one-third (35.2%) of participants, the self-collection by veil allowed detecting nearly 14.4 (101/7)-fold more additional HPV (not detected by swab) than those detected using the clinician-collection by swab. Likewise, the use of veil allowed detecting 12.6 (38/3)-fold more additional HR-HPV in 1 of 8 (13.8%) participants than the use of swab. These findings suggest that the veil is able significantly releasing genital cells for HPV molecular testing, likely better than vaginal tampon. Indeed, cell clusters embedded in a rayon-covered cotton core tampon are not easily separated from the sampling device [48]. Our observations also demonstrate the high capacity of the veil to allow the detection of oncogenic HR-HPV present within the vaginal cavity that could not be detected from the paired swab specimens. Finally, the veil was more efficient to detect oncogenic HR-HPV in whole cervicovaginal secretions than the swab used to collect cervical secretions. Indeed, the veil collects all types of cervicovaginal secretions of the vaginal cavity, not exclusively the cervical secretions, and thus allows detecting non-cervical HPV. Non-cervical HPV are a priori located at non-cervical vaginal areas (vaginal cul-de-sacs, vaginal walls and vulva). Another possibility may be also to consider that cervicovaginal HPV could also come from the male sexual partner, as previously envisaged [48]. Indeed, recent unprotected vaginal intercourse might affect HPV detection because false-positive tests could result from detecting another person’s HPV DNA, or false- negative tests could occur because vaginal penetration could mechanically remove HPV-infected cells. However, we had verified as an exclusion criterion that participants had not had sexual intercourse for at least 48 hours, as recommended for HPV molecular testing in female genital secretions to exclude the risk to catch semen-associated HPV or male-derived exfoliated HPV-infected epithelial cells [48, 49]. Nevertheless, the detection of HR-HPV in vaginal secretions constitutes strong biological evidence that the woman is exposed to oncogenic HPV, which is the basis of molecular HPV screening. Women screened positive for HR-HPV by veil should then be referred for new cervical molecular testing or cervical Pap smear. Indeed, it is well known that an HPV-positive result, regardless of the cytology result, may cause anxiety, stress and concern [95], making mandatory the triage of women found HPV-positive using veil-collected vaginal secretions

Study limitations

Our study had several strengths. First, we tried to limit the selection bias of the study population in order to make this survey as much representative as possible of the female population in Chad. Howver, the prevalences for HIV-1, HBV and HCV in study population was in accordance with the high endemicity of these three major chronic viral infections in Chad [96, 97]. Second, we recruited and screened a large sample of community-recruited women who represent a high-risk primary screening population. Third, both collection methods were performed sequentially on the same day, allowing for direct comparison of the samples collected. Fourth, we were able to assess both the acceptability as well as the performance of the veil-collection method for HPV DNA testing. However, our study has limitations. Thus, the participants could be not completely representative of the adult women community of Chad, especially regarding the prevalences of HIV and cervical HR-HPV, and the genotypes distribution of cervical HPV. Another limitation is that we were not able to directly evaluate which collection method could be the most favorable to further care HPV-positive women. Finally, we did not perform any pathological evaluation, including Pap smear or cervical biopsies on study participants and do not know the true disease status of these women.

Conclusion

Our observations confirm the high burden of cervical oncogenic HR-HPV infection in Chadian women, and point the potential risk of further development of HPV-associated cervical precancerous and neoplastic lesions in a large proportion of women in Chad. Cervical cancer, its diagnosis and prevention, is thus one of the most important public health challenges that Chad has to face in a near future. Self-collection of genital secretions using the V-Veil-Up Gyn Collection Device constitutes a simple, highly acceptable and powerful tool to collect genital secretions for further molecular testing and screening of oncogenic HR-HPV that could be easily implemented in the national cervical cancer prevention program in Chad. In regions of the world where access to care is limited due to socioeconomic reasons or clinician-collected samples may be limited due to personal and/or sociocultural concerns, self-collection method by veil may provide a way to extend screening to an underserved population.

Abbreviations

COFRAC: Comité Français d’Accréditation; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HPV: Human papillomavirus; HR-HPV; High risk-HPV; LR-HPV; Low risk-HPV; STI: Sexually transmitted infection; WHO: World Health Organization

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was formally approved by the Scientific Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences of the University of N’Djamena, constituting the National Ethical Committee. All included women gave their informed signed consent to participate to the study. For each included woman, the record of the consent to participate to the study was documented on each questionnaire. This consent procedure was formally approved by the Ethical Committee. All individual results of HPV detection and genotyping as well as HIV, HBV and HCV serologies were given to each study participant, and women harboring cervical HR-HPV were further retained at the clinic “La Renaissance Plus”, screened for cervical lesions and women showing positive cervical cytology were cared. Furthermore, the study results have been in extenso reported to health authorities of Chad during the national congress of gynecologists and midwives, held from 13 to 17 of November 2018 in the Centre d’Etudes et de Formation pour le Développement (CEFOD), N’Djamena, Chad.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding

No grant was received for the study.

Authors’ contributions

ZAN, DS, RSMB, DK and LB have conceived and designed the research; DS and AMM carried out the ethical issues; RSMB, LR, MMT and DV carried out the experiments; ZAN, RSMB and STW performed statistical analyses; ZAN, RSMB, STW and HP analyzed the results; ZAN, RBMB, CA, HP, DV and LB drafted the manuscript.

Acknowledgement

Zita Aleyo Nodjikouambaye is a PhD student from the Ecole Doctorale en Infectiologie Tropicale, Franceville, Gabon. Ralph-Sydney Mboumba Bouassa is a PhD student from the Ecole Doctorale en Infectiologie Tropicale, Franceville, Gabon, benefiting from a scholarship of the Gabonese Government and is holder of merit from the Agence Universitaire de la Francophonie.The authors are grateful to Bernard Chaffringeon, V-Veil-Up Pharma Ltd., Nicosia, Cyprus, for providing the V-Veil-Up Gyn Collection Devices and the multiplex PCR kits for the study. We are greatly appreciative to all women who participated in our study.

References

- Scheurer ME, Tortolero-Luna G, Adler-Storthz K. (2005) Human papillomavirus infection: biology, epidemiology, and prevention. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 15(5): 727–46. [Crossref]

- Parkin DM. (2006) The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002. Int J Cancer. 118(12): 3030–44. [Crossref]

- Subramanya D, Grivas PD. (2008) HPV and cervical cancer: : updates on an established relationship. Postgrad Med. 120(4): 7–13. [Crossref]

- De Vuyst H, Alemany L, Lacey C, Chibwesha CJ, et al. (2013) The burden of human papillomavirus infections and related diseases in sub-saharan Africa. Vaccine. 31 Suppl 5: F32–46. [Crossref]

- Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, et al. (2015) Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 136(5): E359–86. [Crossref]

- World health Organization, 2015. Projections of mortality and causes of death, 2015 and 2030. (Last accessed July 2018). Available at: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/projections/en/

- Mboumba Bouassa RS, Prazuck T, Lethu T, Jenabian MA, et al. (2017) Cervical cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: a preventable noncommunicable disease. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 15(6): 613–627. [Crossref]

- Finocchario-Kessler S, Wexler C, Maloba M, Mabachi N, et al. (2016) Cervical cancer prevention and treatment research in Africa: a systematic review from a public health perspective. BMC Womens Health. 16: 29. [Crossref]

- Adegoke O, Kulasingam S, Virnig B. (2012) Cervical cancer trends in the United States: a 35-year population-based analysis. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 21(10): 1031–7. [Crossref]

- Kuhn L, Denny L, Pollack A, Lorincz A, et al. (2000) Human papillomavirus DNA testing for cervical cancer screening in low-resource settings. J Natl Cancer Inst 92(10): 818–25. [Crossref]

- Petignat P, Faltin DL, Bruchim I, Tramèr MR, et al. (2007) Are self-collected samples comparable to physician-collected cervical specimens for human papillomavirus DNA testing? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 105(2): 530–5. [Crossref]

- Alidjinou EK, Ebatetou-Ataboho E, Sané F, Moukassa D, et al. (2013) Cervical samples dried on filter paper and dried vaginal tampons can be useful to investigate the circulation of high-risk HPV in Congo. J Clin Virol. 57(2): 161–4. [Crossref]

- Mahomed K, Evans D, Sauls C, Richter K, et al. (2014) Human papillomavirus (HPV) testing on self-collected specimens: perceptions among HIV positive women attending rural and urban clinics in South Africa. Pan Afr Med J. 17: 189. [Crossref]

- Tamalet C, Halfon P, Retraite LL, Grob A, et al. (2016) Genotyping and follow-up of HR-HPV types detected by self-sampling in women from low socioeconomic groups not participating in regular cervical cancer screening in France. J Clin Virol. 78: 102–7. [Crossref]

- Mbatha JN, Galappaththi-Arachchige HN, Mtshali A, Taylor M, et al. (2017) Self-sampling for human papillomavirus testing among rural young women of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. BMC Res Notes. 10(1): 702. [Crossref]

- Modibbo F, Iregbu KC, Okuma J, Leeman A, et al. (2017) Randomized trial evaluating self-sampling for HPV DNA based tests for cervical cancer screening in Nigeria. Infect Agent Cancer. 12: 11. [Crossref]

- Campos NG, Tsu V, Jeronimo J, Njama-Meya D, et al. (2017) Cost-effectiveness of an HPV self-collection campaign in Uganda: comparing models for delivery of cervical cancer screening in a low-income setting. Health Policy Plan. 32(7): 956–968. [Crossref]

- Nobbenhuis MA, Helmerhorst TJ, van den Brule AJ, Rozendaal L, et al. (2002) Primary screening for high risk HPV by home obtained cervicovaginal lavage is an alternative screening tool for unscreened women. J Clin Pathol. 55(6): 435–9. [Crossref]

- Garland SM, Tabrizi SN. (2004) Diagnosis of sexually transmitted infections (STI) using self-collected non-invasive specimens. Sex Health. 1(2): 121–6. [Crossref]

- Jones HE, Wiegerinck MA, Nieboer TE, Mol BW, et al. (2008) Women in the Netherlands prefer self-sampling with a novel lavaging device to clinician collection of specimens for cervical cancer screening. Sex Transm Dis. 35(11): 916–7. [Crossref]

- Gravitt PE, Belinson JL, Salmeron J, Shah KV. (2011) Looking ahead: a case for human papillomavirus testing of self-sampled vaginal specimens as a cervical cancer screening strategy. Int J Cancer. 129: 517–527. [Crossref]

- Harper DM, Noll WW, Belloni DR, Cole BF. (2002) Randomized clinical trial of PCR-determined human papillomavirus detection methods: self-sampling versus clinician-directed–biologic concordance and women’s preferences. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 186(3): 365–73. [Crossref]

- Herrington CS. (2002) Self testing for human papillomaviruses. J Clin Pathol. 55(6): 408–9. [Crossref]

- Bidus MA, Zahn CM, Maxwell GL, Rodriguez M, et al. (2005) The role of self-collection devices for cytology and human papillomavirus DNA testing in cervical cancer screening. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 48(1): 127–32. [Crossref]

- Holanda F Jr, Castelo A, Veras TM, de Almeida FM, et al. (2006) Primary screening for cervical cancer through self sampling. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 95: 179–184. [Crossref]

- Morris BJ, Rose BR. (2007) Cervical screening in the 21st century: the case for human papillomavirus testing of self-collected specimens. Clin Chem Lab Med. 45(5): 577–91. [Crossref]

- Gök M, Heideman DA, van Kemenade FJ, Berkhof J, et al. (2010) HPV testing on self collected cervicovaginal lavage specimens as screening method for women who do not attend cervical screening: cohort study. BMJ. 340: c1040. [Crossref]

- Arbyn M, Verdoodt F, Snijders PJ, Verhoef VM, et al. (2014) Accuracy of human papillomavirus testing on self-collected versus clinician-collected samples: a meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 15(2): 172–83. [Crossref]

- Porras C, Hildesheim A, González P, Schiffman M, et al. (2014) Performance of self-collected cervical samples in screening for future precancer using human papillomavirus DNA testing. J Natl Cancer Inst. 107(1): 400. [Crossref]

- Adamson PC, Huchko MJ, Moss AM, Kinkel HF, et al. (2015) Acceptability and Accuracy of Cervical Cancer Screening Using a Self-Collected Tampon for HPV Messenger-RNA Testing among HIV-Infected Women in South Africa. PLoS One. 10(9): e0137299. [Crossref]

- Arbyn M, Smith SB, Temin S, Sultana F, et al. (2018) Collaboration on Self-Sampling and HPV Testing. Detecting cervical precancer and reaching underscreened women by using HPV testing on self samples: updated meta-analyses. BMJ. 363: k4823. [Crossref]

- Senkomago V, Ting J, Kwatampora J, Gukare H, et al. (2018) High-risk HPV-RNA screening of physician- and self-collected specimens for detection of cervical lesions among female sex workers in Nairobi, Kenya. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 143(2): 217–224. [Crossref]

- Elliott T, Kohler RE, Monare B, Moshashane N, et al. (2019) Performance of vaginal self-sampling for human papillomavirus testing among women living with HIV in Botswana. Int J STD AIDS.: 956462419868618. [Crossref]

- Fall NS, Tamalet C, Diagne N, Fenollar F, et al. (2019) Feasibility, Acceptability, and Accuracy of Vaginal Self-Sampling for Screening Human Papillomavirus Types in Women from Rural Areas in Senegal. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 100(6): 1552–1555. [Crossref]

- Fitzpatrick MB, Dube Mandishora RS, Katzenstein DA, McCarty K, et al. (2019) hrHPV prevalence and type distribution in rural Zimbabwe: A community-based self-collection study using near-point-of-care GeneXpert HPV testing. Int J Infect Dis. 82: 21–29. [Crossref]

- Fitzpatrick MB, El-Khatib Z, Katzenstein D, Pinsky BA, et al. (2019) Community-based self-collected human papillomavirus screening in rural Zimbabwe. BMC Public Health. 19(Suppl 1): 603. [Crossref]

- Racey CS, Withrow DR, Gesink D. (2013) Self-collected HPV testing improves participation in cervical cancer screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Public Health. 104(2): e159–66. [Crossref]