Abstract

Background: Effective hospital teams can improve outcomes, yet, traditional hospital staffing, leadership, and rounding practices discourage effective teamwork and communication. Under the Accountable Care Unit model, physicians are assigned to units, team members conduct daily structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds, and physicians and nurses are jointly responsible for unit outcomes.

Objectives: To evaluate the impact of ACUs on patient outcomes.

Design: Retrospective, pre-post design with concurrent controls.

Patients: 23,406 patients admitted to ACU and non-ACU medical wards at a large academic medical center between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2012.

Measures: In-hospital mortality and discharge to hospice, length of stay, 30-day readmission.

Results: Patients admitted to ACUs were less likely to be discharged dead or to hospice (-1.8 percentage point decline [95% CI: -3.3, -0.3; p = .015]) ACUs did not reduce 30 day readmission rates or have a significant effect on length-of-stay.

Conclusions: Results suggest ACUs improved patient outcomes. However, it is difficult to identify the impact of ACUs against a backdrop of low inpatient mortality and the development of a hospice unit during the study period.

Keywords

quality improvement, teamwork, hospital medicine, care standardization

Introduction

Under the traditional model of inpatient staffing, hospitals nurses and allied health professionals are assigned to a unit, while hospital medicine physicians treat patients on multiple units. Care is delivered asynchronously. Physicians see patients when their schedules permit, usually early in the morning or in the late afternoon and update orders at those times. Nurses and other professionals care for patients separately. They may not see the physician during rounds, and their priorities for patient care may be different from those of the physician. In our experience, they often obtain information from second-hand sources or the often difficult-to-decipher notes in patients’ charts.

The traditional, physician-centric model of inpatient care poses significant coordination and incentive problems. Beginning in October 2010, Emory University Hospital re-organized two medical units into Accountable Care Units (ACU® units). In the ACU care model, hospital-based physicians are assigned to a home unit where they can focus on the patients in the unit and work with the same nurse team. By assigning physicians to home units with other unit-based personnel such as nurses and having teams engage in structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds, ACUs enable clinicians to recognize preventable hospital complications and signs of deterioration or diagnostic error that might otherwise have been missed and implement a coordinated response.

Previous publications on the ACU model have been mostly descriptive in nature [1–4]. Using electronic medical records and a pre-post study design with concurrent controls, we retrospectively evaluated the effect of ACUs on patient mortality, length of stay, and readmissions at Emory University Hospital.

Methods

Intervention

Emory University Hospital is a 500 bed teaching hospital in Atlanta, Georgia. Prior to the implementation of ACUs, hospital medicine physicians at Emory University Hospital treated patients in as many as eight units. In the first unit to be organized into an ACU, patients were divided between five physician care teams prior the re-organization. Beginning in October 2010, Emory University Hospital assigned two physician care teams to each of two newly-constituted ACU units. ACUs combine a number of interventions, some of which have been implemented at other hospitals [5–8] , into a single, cohesive bundle.

ACU physician teams were assigned to units and included one hospital medicine attending physician, one internal medicine resident, and three interns. Within an ACU, two teams rotated call schedules over a 24 hour period. The team on-call admitted every patient who arrived at the unit. The same nurse teams continued to staff each unit as before the reorganization.

ACUs standardize communication through a series of brief but highly scripted intra- and inter-professional exchanges to review patients’ conditions and care plans. Each shift change begins with a five minute huddle where the departing staff hands over the unit to the incoming staff. During the huddle, the departing staff alerts the incoming staff to patient- and quality-related issues. After the huddle, nurses hand over individual patients at the bedside using a structured format, highlighting patient-level factors that might indicate patient instability or are outside the expected range. Once a day, each patient’s care team meets for structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds. Structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds bring the bedside nurse, attending physician, and unit-based allied health professionals to the bedside every day with the patient and family members to review the patient’s current condition, response to treatment, care plan, and discharge plan collaboratively [5–8]. Evidence-based actions, such as “bundles” to prevent hospital acquired conditions, are embedded in structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds, and reported on by the patient’s nurse. A scripted, standard communication protocol reduces extraneous communication and focuses the structured interdisciplinary bedside round team’s attention on aspects of patients’ conditions that are responsive to staff attention and effort.

A unit leadership dyad, consisting of a nurse manager and senior physician, set explicit expectations for staff and manage unit process and performance. Physicians operating in the traditional model may be unaware of unit-level quality protocols and outcome measures. As part of the re-organization, a data analyst prepared quarterly unit-level performance reports describing rates of in-hospital mortality, blood stream infections, 30-day readmissions and patient satisfaction scores and length of stay. These reports are used by hospital administrators to set goals for the ACU leadership team and may figure into the performance evaluations of ACU administrators. Readers interested in additional details about the ACU model are urged to consult previous publications [1–4].

Following implementation of ACUs, physician teams assigned to ACUs saw patients on only 1.5 units, with 90% of their patients located in the ACUs, compared to non-ACU physician teams, which cared for patients spread across 6 to 8 units every day.1 The number of patient encounters per day for the ACU physician teams increased from 11.8 in the year before the ACUs (when the teams were not unit based) to 12.9 in the four years following implementation [1]. No changes were made to nurse staffing levels (1 to 4 or 5 nurses per patient).

During the study period, Emory University Hospital created two ACUs, but medical patients were also admitted to seven other units in the hospital. The units that became ACUs were selected because nearly all the patients were under the care of hospital medicine attending physicians so we could designate them as hospital medicine units. In other units, hospital medicine patients were mixed in with patients from other specialties (for example, cardiology). The assignment of patients to ACUs or other medical units was determined by bed control officers based on a mix of criteria that can include bed availability, relative patient wait times, and individual judgement. Bed managers know patients’ names, medical record number, and admitting diagnosis when they assign patients to units. They do not know have access to other prognostic indicators.

Study Sample

The study sample includes patients ages 18 and older admitted to the medical units of Emory University Hospital between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2013. Following an intent-to-treat framework, we grouped patients who were transferred into ACUs during their hospital stay with non-ACU patients. Patients admitted to surgical, orthopedic, observation, or other specialty units (e.g. medical oncology) were excluded from the analysis, as were patients with cystic fibrosis who are treated only within one of the two ACUs. Patients in the control group were spread across 38 units, though 70% were in just 8 of these units.

Data and Outcome Variables

All study variables are captured in Emory’s internal electronic medical record and administrative data systems. We evaluated the impact of ACUs on in-hospital mortality, discharge to hospice, length of stay, readmission or emergency department visit to Emory University hospital within 30 days, and hospital-acquired urinary tract infection and deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. We counted a patient as having hospital-acquired urinary tract infection and deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism if their records listed ICD-9 codes for these condition but not if they were among the present-on-admission ICD-9 codes.

Emory University Hospital opened an on-site hospice during the study period in November 2010, potentially reducing the barriers to transferring patients from the hospital to hospice care. While discharge to hospice is in many cases an indication of appropriate care, the opening of the inpatient hospice complicates efforts to measure trends in in-patient mortality. The opening of the unit may be responsible for changes in the site of death for patients admitted to the hospital over time. For this reason, we highlight the impact of ACUs on the combined outcome of in-hospital death or discharge to hospice.

Statistical Analysis

We compared patient characteristics between ACUs and control units using chi-squared tests. We estimated the impact of ACUs on these outcomes using a difference-in-difference study design (equivalently, a pre/post study with a concurrent control group). The pre period was January 1, 2008 to October 31, 2010. The post period was November 1, 2010 to December 31, 2012. We calculated the change in outcomes between the pre and post periods among patients admitted to the units that became ACUs and the change among patients in the control group. The difference of these changes is the difference-in-difference estimator. It assesses changes in outcomes in the units that became ACUs relative to changes in the control group. It assumes that absent any change in policy (i.e., the implementation of ACUs), trends in outcomes among patients admitted to the ACUs would have mirrored trends among patients in the control group. We calculated 95% confidence intervals for unadjusted estimates using z-tests. We used logistic regression with robust standard errors to estimate adjusted effects for in-hospital mortality and hospice discharges and readmissions. We used Poisson regression with robust standard errors to estimate adjusted effects for length of stay. We calculated standard errors and 95% confidence intervals for the difference-in-difference estimator using the Delta method [9].

In multivariable analysis, we adjusted estimates for patient age group, sex, race, primary payer, admission source (hospital or skilled nursing facility versus other), and Elixhauser comorbidities (based on all diagnosis codes) [10] that were present in at least 2.5% of patients in the sample. About one-third of the sample had missing values for admission source. We included each Elixhauser comorbidities as a separate variable in the model rather than collapsing the conditions into a count to avoid imposing unnecessary restrictions on the relationship between conditions and outcomes. Conditions are not mutually exclusive.

Estimates from difference-in-difference models may be biased if there are pre-existing trends in outcomes that differ between ACU and non-ACU units. We tested for pre-existing trends by estimating a model that included, in addition to the variables described above, indicators for the years in the pre-period (2008 to 2010) and these year indicators interacted with treatment group (ACU versus non ACU). We assessed the significance of the year-group interactions and used a likelihood ratio test to compare the model fit with a model that omitted the year-group interactions [11].

Estimates of the impact of ACUs on in-hospital mortality and hospice discharge rates may be biased by differences in length of stay. An intervention that reduces length of stay but does not affect mortality rates will reduce in-hospital mortality rates by shifting the place of death from the hospital to the community. In a sensitivity analysis we assessed the robustness of logistic regression estimates by estimating a Weibull survival model with robust standard errors of the time to hospice discharge or in-hospital death. Records for patients who were not discharged to hospice or dead are censored.

Results

There were 23,403 patients included in the study sample, of whom 10,639 were admitted to the ACU units (including patients admitted to the units before they became ACUs) and 12,764 patients in the control group. There are significant differences in some of the characteristics of ACU and control group patients in the pre and post periods (Table 1), but most differences are qualitatively small. There are some clinically meaningful differences in patients’ diagnoses. For example, in the pre-ACU period, 8.2% of patients in the control group had a solid tumor compared to 6.7% in the ACU group.

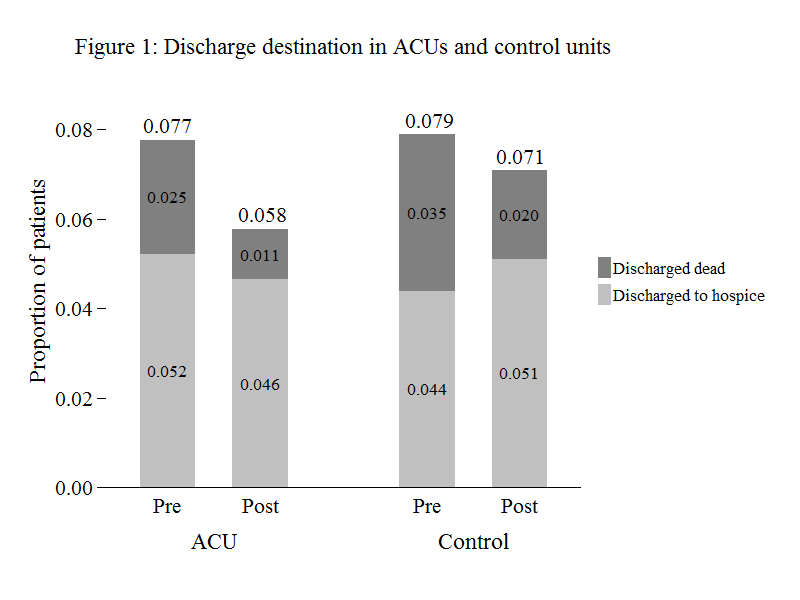

The unadjusted proportion of ACU patients discharged to hospice or dead declined from 7.7% to 5.8% (Figure 1) or -2.0 (95% CI: -2.9, -1.0) percentage points. The unadjusted proportion of patients discharged to hospice and dead both declined. A reduction in in-hospital mortality rates accounted for 70% of the decline (= [2.5–1.1] ÷ 2).

Figure 1. Discharge destination in ACUs and control units

Table 1. Sample characteristics

|

Pre |

Post |

||||||||||||

|

|

|

All |

|

Control patients |

ACU patients |

P-value |

Control patients |

ACU patients |

P-value |

||||

|

N (%) |

N (%) |

N (%) |

|||||||||||

|

N |

23,403 |

6,219 |

5,499 |

6,545 |

5,140 |

||||||||

|

Age |

<0.001 |

.043 |

|||||||||||

|

18–49 |

6,580 |

(28.1) |

1,721 |

(27.7) |

1,577 |

(28.7) |

1,827 |

(27.9) |

1,455 |

(28.3) |

|||

|

50–64 |

5,760 |

(24.6) |

1,459 |

(23.5) |

1,477 |

(26.9) |

1,582 |

(24.2) |

1,242 |

(24.2) |

|||

|

65–74 |

3,900 |

(16.7) |

1,000 |

(16.1) |

904 |

(16.4) |

1,089 |

(16.6) |

907 |

(17.6) |

|||

|

75–84 |

3,850 |

(16.5) |

1,063 |

(17.1) |

883 |

(16.1) |

1,051 |

(16.1) |

853 |

(16.6) |

|||

|

85+ |

3,313 |

(14.2) |

976 |

(15.7) |

658 |

(12.0) |

996 |

(15.2) |

683 |

(13.3) |

|||

|

White |

11,719 |

(50.1) |

3,314 |

(53.3) |

2,796 |

(50.8) |

.008 |

3,195 |

(48.8) |

2,414 |

(47.0) |

.047 |

|

|

Male |

9,939 |

(42.5) |

2,542 |

(40.9) |

2,393 |

(43.5) |

.004 |

2,746 |

(42.0) |

2,258 |

(43.9) |

.032 |

|

|

Insurance status |

.024 |

.965 |

|||||||||||

|

Medicare |

12,079 |

(51.6) |

3,144 |

(50.5) |

2,728 |

(49.6) |

3,470 |

(53.0) |

2,737 |

(53.2) |

|||

|

Medicaid |

2801 |

(12.0) |

632 |

(10.2) |

642 |

(11.7) |

849 |

(13.0) |

677 |

(13.2) |

|||

|

Self-pay |

1598 |

(6.8) |

416 |

(6.7) |

400 |

(7.3) |

439 |

(6.7) |

343 |

(6.7) |

|||

|

Private/Other |

2504 |

(10.7) |

5,171 |

(83.1) |

4,457 |

(81.1) |

5,257 |

(80.3) |

4,120 |

(80.2) |

|||

|

Admitted from facility |

2504 |

(10.7) |

798 |

(12.8) |

503 |

(9.1) |

<0.001 |

730 |

(11.2) |

473 |

(9.2) |

0.001 |

|

|

Diagnoses |

|||||||||||||

|

Congestive heart failure |

1,998 |

(8.5) |

438 |

(7.0) |

389 |

(7.1) |

.948 |

653 |

(10.0) |

518 |

(10.1) |

.857 |

|

|

Pulmonary circulation disorders |

1,211 |

(5.2) |

331 |

(5.3) |

252 |

(4.6) |

.066 |

399 |

(6.1) |

229 |

(4.5) |

<0.001 |

|

|

Hypertension |

719 |

(3.1) |

148 |

(2.4) |

179 |

(3.3) |

.004 |

217 |

(3.3) |

175 |

(3.4) |

.790 |

|

|

Other neurological disorders |

2,869 |

(12.3) |

530 |

(8.5) |

631 |

(11.5) |

<0.001 |

867 |

(13.2) |

841 |

(16.4) |

<0.001 |

|

|

Chronic pulmonary disease |

1,205 |

(5.1) |

287 |

(4.6) |

268 |

(4.9) |

.511 |

352 |

(5.4) |

298 |

(5.8) |

.326 |

|

|

Diabetes |

895 |

(3.8) |

188 |

(3.0) |

201 |

(3.7) |

.057 |

258 |

(3.9) |

248 |

(4.8) |

.020 |

|

|

Renal failure |

1,531 |

(6.5) |

234 |

(3.8) |

315 |

(5.7) |

<0.001 |

473 |

(7.2) |

509 |

(9.9) |

<0.001 |

|

|

Liver disease |

796 |

(3.4) |

142 |

(2.3) |

215 |

(3.9) |

<0.001 |

211 |

(3.2) |

228 |

(4.4) |

.001 |

|

|

Metastatic cancer |

694 |

(3.0) |

248 |

(4.0) |

170 |

(3.1) |

.009 |

152 |

(2.3) |

124 |

(2.4) |

.750 |

|

|

Solid tumor |

1,548 |

(6.6) |

512 |

(8.2) |

371 |

(6.7) |

.002 |

365 |

(5.6) |

300 |

(5.8) |

.547 |

|

|

Fluid and electrolyte disorders |

1,814 |

(7.8) |

410 |

(6.6) |

379 |

(6.9) |

.519 |

506 |

(7.7) |

519 |

(10.1) |

<0.001 |

|

|

Deficiency anemias |

672 |

(2.9) |

150 |

(2.4) |

176 |

(3.2) |

.010 |

179 |

(2.7) |

167 |

(3.2) |

.104 |

|

The unadjusted proportion of patients in the control group discharged to hospice or dead declined from 7.9% to 7.1%, or -0.8 (95% CI: -1.7, 0.1) percentage points. A decline in the proportion of patients discharged dead was offset by an increase in the proportion discharged to hospice.

Adjusted estimates of the impact of ACUs are displayed in the last columns of Table 2. (Full regression results are available in the Appendix Table.) The adjusted estimate of the impact of ACUs on the composite outcome of discharged dead or to hospice is -1.8 (95% CI: -3.3, -0.3; p = .015) percentage points. The adjusted difference-in-difference estimate of the impact of ACUs on length of stay is negative but not statistically significant (-0.5 days [95% CI: -1.2, -0.3; p =.21]). The estimates for 30 day readmissions and hospital-acquired urinary tract infections are close to 0. The estimate of the impact of ACUs on the occurrence of pulmonary embolism/deep vein thrombosis was positive and borderline significant (0.6 percentage points [95% CI: -0.05, 1.3] p = .07).

Table 2. Changes in outcomes among ACU and non-ACU patients

|

|

|

|

Time period |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

Pre-ACU |

|

|

Post-ACU |

|

Unadjusted difference |

P-value |

Adjusted difference |

P-value |

|||||||

|

In-hospital mortality (%) |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

ACU |

2.5 |

(2.1, |

2.9) |

1.1 |

(0.8, |

1.4) |

-1.4 |

(-1.9, |

-0.9) |

||||||||||

|

Control |

3.5 |

(3.0, |

4.0) |

2.0 |

(1.6, |

2.3) |

-1.5 |

(-2.1, |

-1.0) |

||||||||||

|

Difference |

-1.0 |

(-1.6, |

-0.4) |

-0.9 |

(-1.3, |

-0.4) |

0.1 |

(-0.6, |

0.9) |

.765 |

-0.1 |

(-0.7, |

0.8) |

0.88 |

|||||

|

Hospice discharge (%) |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

ACU |

5.2 |

(4.6, |

5.8) |

4.6 |

(4.1, |

5.2) |

-0.6 |

(-1.4, |

0.3) |

||||||||||

|

Control |

4.4 |

(3.9, |

4.9) |

5.1 |

(4.6, |

5.6) |

0.7 |

(0.0, |

1.5) |

||||||||||

|

Difference |

0.8 |

(0.1, |

1.6) |

-0.5 |

(-1.2, |

0.3) |

-1.3 |

(-2.4, |

-0.2) |

.023 |

-1.8 |

(-3.2, |

-0.4) |

0.013 |

|||||

|

In-hospital mortality and hospice discharge (%) |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

ACU |

7.7 |

(7.0, |

8.5) |

5.8 |

(5.1, |

6.4) |

-2.0 |

(-2.9, |

-1.0) |

||||||||||

|

Control |

7.9 |

(7.2, |

8.6) |

7.1 |

(6.5, |

7.7) |

-0.8 |

(-1.7, |

0.1) |

||||||||||

|

Difference |

-0.1 |

(-1.1, |

0.8) |

-1.3 |

(-2.2, |

-0.4) |

-1.2 |

(-2.5, |

0.2) |

.083 |

-1.8 |

(-3.3, |

-0.3) |

0.015 |

|||||

|

Length of stay (days) |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

ACU |

6.5 |

(6.3, |

6.7) |

6.4 |

(6.2, |

6.6) |

-0.1 |

(-0.4, |

0.2) |

||||||||||

|

Control |

5.1 |

(4.6, |

5.7) |

5.4 |

(5.2, |

5.5) |

0.2 |

(-0.3, |

0.8) |

||||||||||

|

Difference |

1.4 |

(0.8, |

2.0) |

1.0 |

(0.8, |

1.3) |

-0.4 |

(-1.0, |

0.3) |

.281 |

-0.5 |

(-1.2, |

0.3) |

0.21 |

|||||

|

30 day readmissions (%) |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

ACU |

22.2 |

(21.1, |

23.3) |

21.0 |

(19.8, |

22.1) |

-1.2 |

(-2.8, |

0.3) |

||||||||||

|

Control |

22.3 |

(21.3, |

23.4) |

20.9 |

(19.9, |

21.9) |

-1.4 |

(-2.9, |

0.0) |

||||||||||

|

Difference |

-0.1 |

(-1.7, |

1.4) |

0.1 |

(-1.4, |

1.5) |

0.2 |

(-1.9, |

2.3) |

.852 |

0.3 |

(-1.8, |

2.4) |

0.80 |

|||||

|

Urinary tract infection (%) |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

ACU |

5.2 |

(4.6, |

5.8) |

6.6 |

(6.0, |

7.3) |

1.4 |

(0.5, |

2.3) |

||||||||||

|

Control |

5.5 |

(4.9, |

6.0) |

6.7 |

(6.1, |

7.3) |

1.3 |

(0.4, |

2.1) |

||||||||||

|

Difference |

-0.2 |

(-1.1, |

0.6) |

-0.1 |

(-1.0, |

0.8) |

0.1 |

(-1.1, |

1.4) |

.819 |

0.01 |

(-1.2, |

1.2) |

0.99 |

|||||

|

Pulmonary embolism/Deep vein thrombosis (%) |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

ACU |

1.8 |

(1.4, |

2.2) |

2.0 |

(1.7, |

2.4) |

0.2 |

(-0.3, |

0.8) |

||||||||||

|

Control |

1.8 |

(1.5, |

2.2) |

1.6 |

(1.3, |

1.9) |

-0.2 |

(-0.7, |

0.2) |

||||||||||

|

Difference |

0.0 |

(-0.5, |

0.4) |

0.4 |

(-0.1, |

0.9) |

0.5 |

(-0.2, |

1.2) |

.167 |

0.6 |

(-0.05, |

1.3) |

0.07 |

|||||

Models that included year-group interactions rejected the hypothesis of pre-existing trends for discharge status and readmissions (see Appendix for details). In the survival model estimating time to in-hospital death or discharge to hospice, the hazard ratio for the interaction of the ACU group indicator and the post period indicator was less than one but did not achieve significance at α = 0.05 threshold (0.80 [95% CI: .63 to 1.00]; p = .052).

Discussion

Results indicate that ACUs reduced the proportion of patients discharged dead or to hospice. Length of stay declined in ACUs relative to control units, but the effect was mostly driven by an increase in length of stay in control units rather than a decrease in ACUs. ACUs did not appear to affect readmission rates. The opening of an inpatient hospice unit coincided with the introduction of ACUs, making it more difficult to identify the discrete impact of ACUs. However, physicians in all units of the hospital could transfer patients to the inpatient hospice unit, and so it should not have differentially affected outcomes in ACU versus non-ACU patients. The proportion of patients discharged to hospice actually declined slightly in the units that implemented ACUs. This pattern may reflect mean-reversion (the hospice discharge rate was higher in ACU units in the pre-period).

Given the low rates of in-hospital mortality in this patient population and hospital-wide efforts to reduce in-hospital mortality, patient discharge status may not be particularly sensitive to the quality of care. The regular rotation of residents and movement of other unit staff through the hospital may have spread some of the features of ACUs and their processes, resulting in hospital-wide improvements in outcomes.

Consistent with our predetermined analysis plan, we evaluated trends in ACU units relative to trends in control units. However, there were baseline differences in mortality rates and length of stay.

ACUs did not reduce the occurrence of hospital-acquired urinary tract infections and pulmonary embolism/deep vein thrombosis, at least as measured from billing records. It is unclear whether these results reflect a failure of ACUs to improve care or whether they reflect “surveillance bias” [12] : ACU teams may be more likely to recognize and diagnose patients with these conditions. The hospital implemented an initiative to more accurately document patients’ conditions during the study period, which may account for the increase in urinary tract infection rates.

Lacking access to information about patient health after discharge, we were unable to determine the impact of being admitted to an ACU on long-term outcomes. Patients discharged too early may experience adverse outcomes. We found that readmission rates were similar between the ACU and control groups, suggesting that patients were not being discharged from ACUs prematurely.

Although we evaluated the impact of ACUs in a single, large academic medical center, there are no elements or features of the ACU model that would prevent it from being expanded to other care settings. ACUs have already been implemented in community hospitals in the US, Canada (see http: //www.rqhealth.ca/department/patient-flow/accountable-care-unit accessed April 19th 2019) and Australia (see http: //www.cec.health.nsw.gov.au/quality-improvement/team-effectiveness/insafehands accessed April 19th 2019).

Most prior studies on teams in inpatient and outpatient settings focus on single specialty teams (e.g. psychiatric care) and teams designed to address a specific quality issue (e.g., hospital acquired infections) [13,14].A recent report on the implementation of an Accountable Care Teams model, which shares many of the features of ACUs, at Indiana University Health Methodist Hospital found that implementation was associated with reductions in length of stay and costs but did not affect readmission rates or patient satisfaction [15].The assignment of hospitalists to units at Northwestern Memorial Hospital improved communication but did not increase physician-nurse agreement on patients’ care plans [16].

High risk industries with excellent safety records have recognized the value of teams to improving outcomes. ACUs, with their emphasis on patient-centered, interprofessional collaboration, were designed to address shortcomings of the traditional model of hospital organization. Our findings suggest that these and other features of the model were associated with reductions in the proportion of patients discharged dead or to hospice but did not affect other outcomes. Unfortunately, we were unable to assess the degree of fidelity of the study units to all features of the ACU model. Futures studies should include estimates of the extent to which units are implementing all four essential components of the model in estimating the effects of the model on distal outcomes.

Funding: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, R03 HS 022595-01

Conflicts of Interest: Dr Stein and Dr Chadwick are officers of 1Unit, a company that helps hospitals set up and run Accountable Care Units. Drs Howard, Shapiro, Murphy, and Ms Overton do not have any conflicts of interest.

References

- Stein J, Murphy DJ, Payne C et al. (2015) A Remedy for fragmented hospital care. Harvard Business Review-New England Journal of Medicine Online Forum: Leading Healthcare Innovation.

- Stein J, Payne C, Methvin A, et al. (2015) Reorganizing a Hospital Ward as an Accountable Care Unit. J Hosp Med 10: 36–40.

- Castle B, Shapiro S (2016) Accountable Care Units: A Disruptive Innovation in Acute Care delivery. Nurs Adm Q 40: 14–23.

- Shapiro S (2015) Accountable care at Emory Healthcare: Nurse-led interprofessional collaborative practice. VOICE of Nursing Leadership 13: 6–9

- Pronovost P, Berenholtz S, Dorman T, et al. (2003) Improving communication in the ICU using daily goals. J Crit Care 18: 71–75.

- O’Mahony S, Mazur E, Charney P, et al. (2007) Use of multidisciplinary rounds to simultaneously improve quality outcomes, enhance resident education, and shorten length of stay. J Gen Intern Med 22: 1073–1079.

- Cowan M, Shapiro M, Hays R, et al. (2006) The effect of a multidisciplinary hospitalist/physician and advanced practice nurse collaboration on hospital costs. J Nurs Adm 36: 79–85.

- Vazirani S, Hays RD, Shapiro MF, et al. (2005) Effect of a multidisciplinary intervention on communication and collaboration among physicians and nurses. Am J Crit Care 14: 71–77

- Dowd BE, Greene WH, Norton EC (2014) Computation of Standard Errors. Health Serv Res 49: 731–750.

- Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM (1998) Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care 36: 8–27.

- Volpp KG, Small DS, Romano PS (2013) Teaching hospital five-year mortality trends in the wake of duty hour reforms. J Gen Intern Med 28: 1048–1055.

- Bilimoria KY, Chung J, Ju MH, et al. (2013) Evaluation of surveillance bias and the validity of the venous thromboembolism quality measure. JAMA 310: 1482–1489.

- Bosch M, Faber M, Cruijsberg J, et al. (2009) Effectiveness of patient care teams and the role of clinical expertise and coordination: a literature review. Med Care Res Rev 66: 5S-35S.

- Pannick S, Davis R, Ashrafian H, Byrne BE, Beveridge I, et al (2015) Effects of Interdisciplinary Team Care Interventions on General Medical Wards: A Systematic Review. JAMA Intern Med. 175: 1288–98.

- Kara A, Johnson C, Nicely A, Neimeier MR, Hui SL (2015) Redesigning inpatient care: Testing the effectiveness of an Accountable Care Team model. Journal of Hospital Medicine 10: 773–779.

- O’Leary KJ, Wayne DB, Landler MP, et al. (2009) Impact of localizing physicians to hospital units on nurse-physician communication and agreement on the plan of care. J Gen Intern Med 24: 1223–1227.