DOI: 10.31038/ASMHS.2019341

Abstract

Objectives: The objective of this pilot study was to determine if a 3-dimensional multiple object tracking training (3D-MOT) intervention could improve performance on measures of attention, psychomotor speed, and cognitive flexibility in healthy older adults.

Methods: Forty-six individuals aged 63–87 years old participated in the study. Twenty-five participants in the intervention group completed the Stroop task before and after intervention that consisted of seven training sessions with the Neurotracker, a 3D-MOT software program. Stroop test scores were examined for changes in selective attention, cognitive flexibility (CF), as well as psychomotor speed pre- and post-intervention. The 21 individuals in the control group completed the Stroop test at the pre-post interval, without completing the Neurotracker intervention.

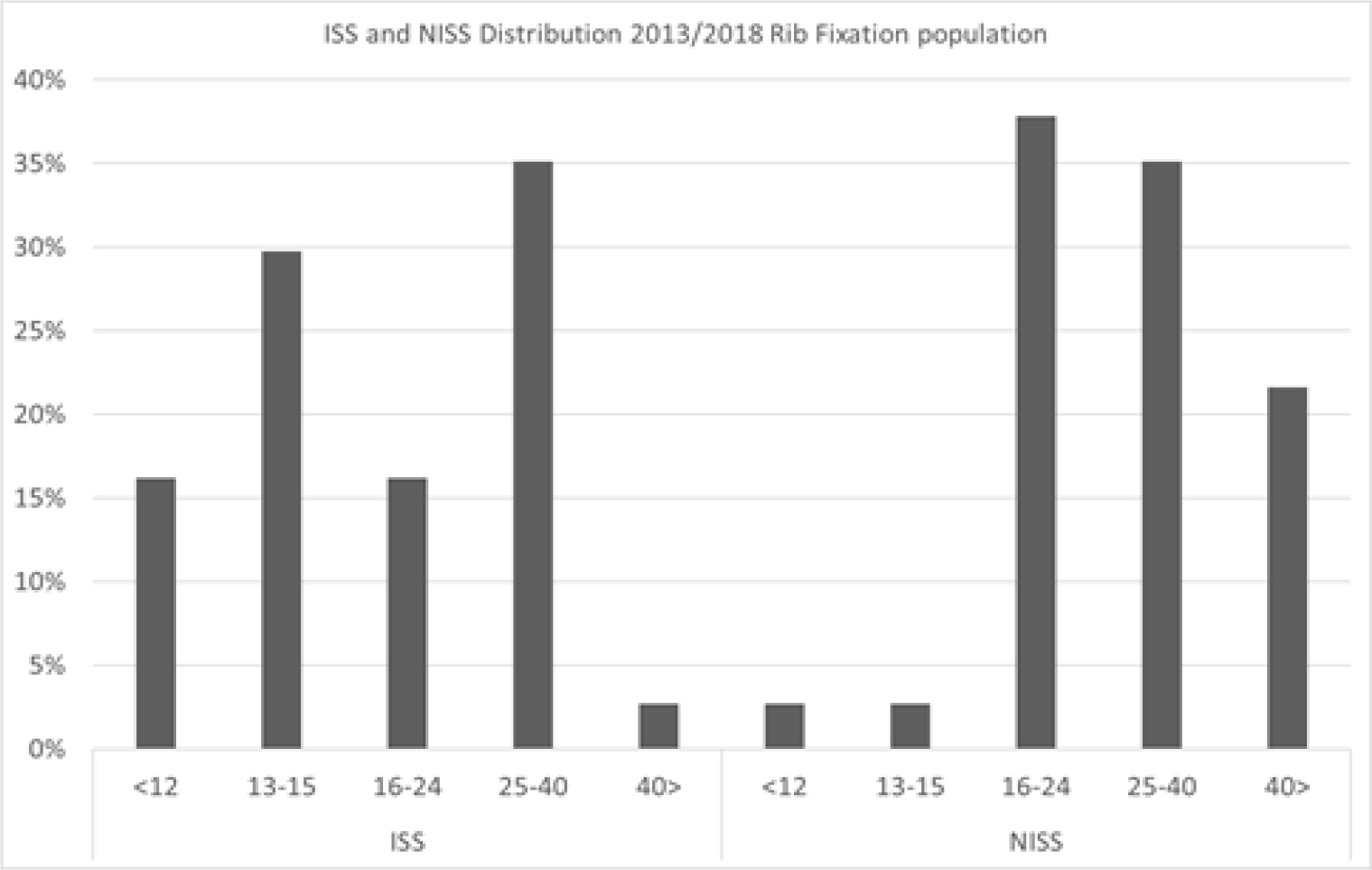

Results: The Neurotracker training intervention group showed significant improvements in both cognitive flexibility (M = 5.01, SE = 1.44, p = 0.002), and psychomotor speed and selective attention (M = 4.90, SE = 1.44, p = 0.002). Significant changes were also detected in a condition that measured psychomotor speed and cognitive flexibility together (M = 9.39, SE = 1.74, p < 0.001). No significant changes were detected in the control group.

Conclusion: The current results suggest that the Neurotracker may be an effective tool for improving selective attention, cognitive flexibility, and psychomotor speed in healthy older individuals.

Introduction

Changes in cognitive performance with normal aging have been well documented [1,2]. In particular, older adults are known to have reduced information processing speed and declines in executive functions (EF) [3,4]. Although EF captures many cognitive processes (e.g. complex attention, cognitive inhibition, working memory, and cognitive flexibility), changes in complex attention and cognitive flexibility are most frequently reported [3–5]. Specifically, complex attention includes divided attention, or the ability to attend to multiple stimuli simultaneously [6], while cognitive flexibility captures the mental ability to switch attention between multiple concepts. Therefore, such changes in EF may reduce an individuals’ capacity to behaviorally adapt to changing environment, and may help explain some of the difficulties experienced by older adults from tasks such as driving [1,2,7–10 ].

Age-related impairments in EF have been linked to structural alterations in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) in normal aging [4,11–13]. Additional changes, linked more specifically to declines in attention, include cortical thinning in the PFC [14], and decreased functional magnetic resonance imaging activation across the dorsolateral prefrontal and parietal cortices [15–17] and the anterior cingulate cortex [16,18]. Despite these structural and functional changes, the continued plasticity of the aging brain has been well-documented [19–21]. As a result, interventions for older adults have been a focus of emerging age-related research. However, current pharmacological and behavioral interventions to reduce age-related cognitive declines are limited in their efficacy. Therefore, increasing attention has been paid to the use of cognitive interventions as tools to improve cognition in older adults because they are readily available and easy to administer.

Three-dimensional multiple object tracking (3D-MOT) is a video game technology has been previously used to study attentional enhancement [22,23]. Specifically, 3D-MOT is thought to stimulate brain networks essential to executive functions, such as attention, cognitive flexibility and working memory [24]. As a result, 3D-MOT has been investigated as an emerging tool used to enhance perceptual cognitive abilities in both elite athletes [24–26] and the general population [27–30]. The video game requires subjects to follow a discrete number of moving sub-targets from an array of identical targets [31]. One of the major cognitive skills used in 3D-MOT is attention, including sustained, selective, and divided attention, as well as inhibition and reaction time [30]. Flexibility is conditioned by training the participant to allocate the correct attentional resource while tracking multiple objects [32,33]. Generally, individuals are able to track three to five targets efficiently; however, with age and associated cognitive decline, the ability to track multiple objects decreases [28]. Trick, Perl, and Sethi [34] assessed MOT performance in groups of young (M = 19 years old)and older adults (M = 73 years old), finding that young adults were able to efficiently track four items simultaneously, while older adults could effectively track three items. These results may be attributed to a general decline in attentional capacity: specifically, a decreased activation of the dorsal attentional network [35] that accompanies normal aging.

Given the documented cognitive differences in older adults and evidence that the 3D-MOT can improve cognitive performance in other groups, recent research has focused on whether interventions such as 3D-MOT can improve EF performance in older adults. One particularly relevant study by Legault et al. [28] examined differences in performance between ten young (M = 27 years old) and ten older adults (M = 66 years old) following 5 weeks of training on a 3D-MOT task. Older adults were poorer at tracking pre-intervention; however, they improved on the 3D-MOT task at the same rate as the younger group and continued to improve even when the young adults plateaued. These findings were attributed to the automaticity of tracking following multiple 3D-MOT training sessions, which reduced the attentional load necessary for tracking and thus improved performance. The importance of these findings is the notion that, while some degree of cognitive decline is unavoidable, cognitive decline may be delayed, or even improved, with sufficient training. However, there is debate whether the benefits of these training tools demonstrate far-transfer effects to more generalized cognitive domains, or whether the gains are limited to performance on the training tool itself. It remains unknown how such intervention-based changes may relate to standard measures of cognitive function. The objective of this pilot study was to examine the influence of 3D-MOT training on selective attention, psychomotor speed, and cognitive flexibility in healthy older adults. It was hypothesized that following 7 training sessions on the Neurotracker, a 3D-MOT software program, participants would show improvement in selective attention, cognitive flexibility, and psychomotor speed, as measured by scores on the Stroop test.

Methods

Participants

Older adults aged at least 60 years were recruited from various senior activity centers in Victoria, British Columbia. Participants at these sites were recruited following a brief presentation summarizing he research project. Additionally, a small subset of the sample responded to flyers posted at various seniors’ centres and health facilities. Approval for this project was obtained from the University of Victoria’s human research ethics board.

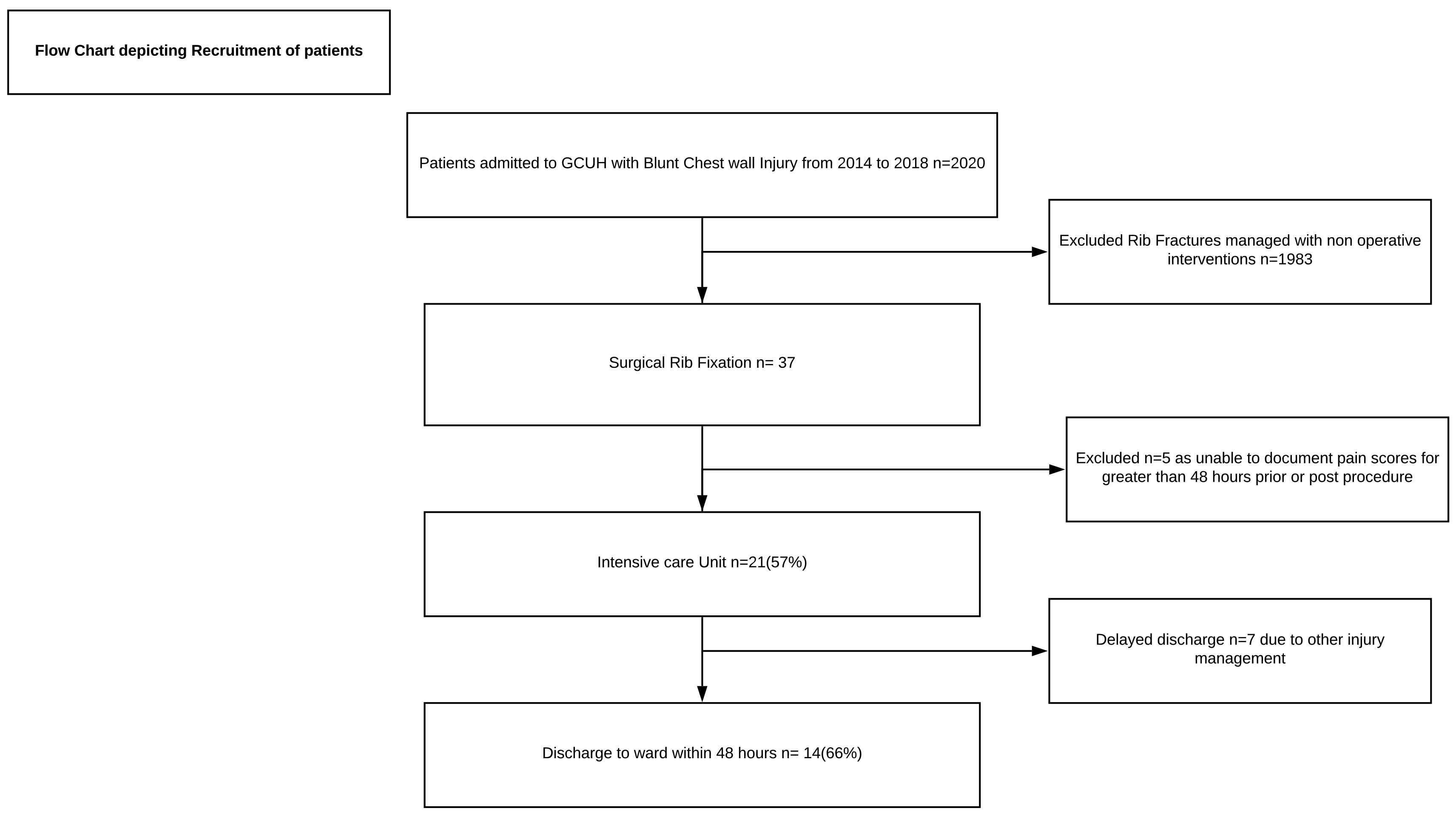

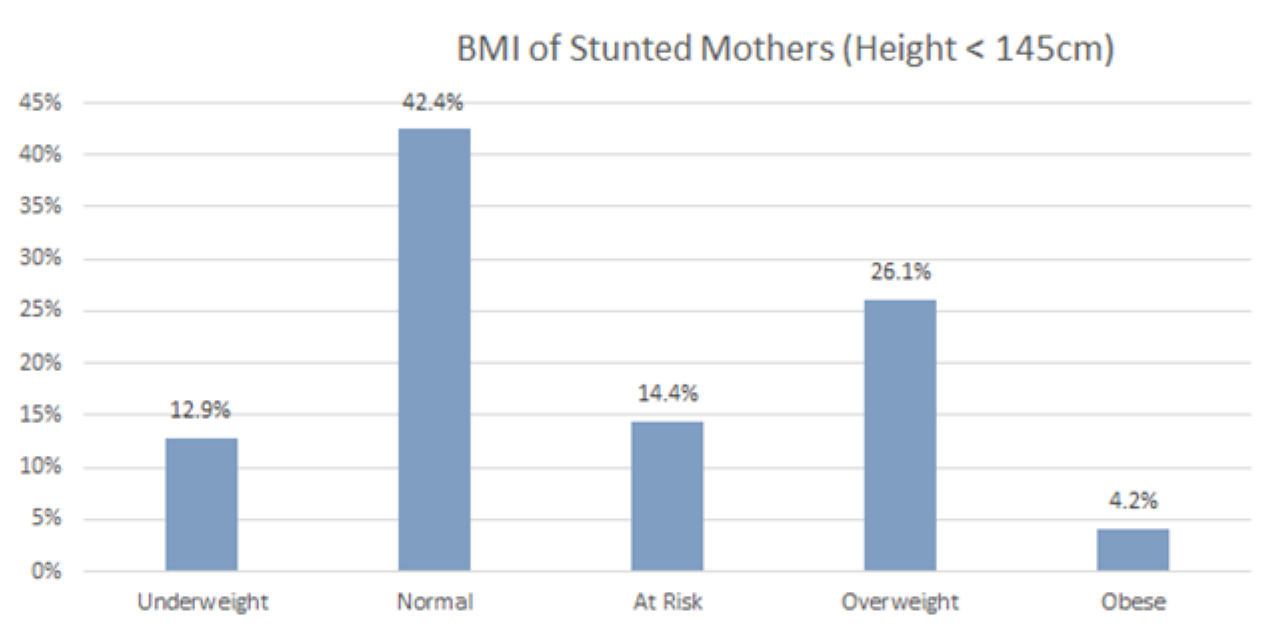

Eligibility criteria for inclusion included being aged 60 years or older, and able to fully complete an eight-week testing/training period. Age criteria were based on previous research demonstrating that age-related declines in cognition begin around aged 60 years and older [4,36,37]. Exclusion criteria included major neurocognitive diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia, or pronounced colour blindness, as the current study required participants to differentiate between colours on both the Stroop test and Neurotracker (Figure 1 for enrolment process).

Figure 1. Flow diagram outlining participant inclusion process

Initially, 30 healthy participants were recruited for the intervention group, and 25 adults between the ages of 63–87 years old (M = 71.44, SD = 6.04) completed the study. Participants included twelve females (48%) and thirteen males (52%). Twenty-one healthy participants were recruited for the control group, which consisted of 5 males (24%) and 16 females (76%), aged 61–84 years (M = 71.76, SD = 7.47)

(Table 1 for participant education levels).

Table 1. Education obtainment frequencies and percentages of participants in the control and 3D-multiple object tracking training groups.

|

Education level

|

Control group (n = 21)

|

3D-MOT training group (n = 25)

|

|

Frequency

|

Percentage (%)

|

Frequency

|

Percentage (%)

|

|

High school

|

1

|

5

|

1

|

4

|

|

College

|

4

|

19

|

4

|

16

|

|

Bachelors

|

6

|

29

|

13

|

52

|

|

Masters/PhD

|

10

|

47

|

7

|

28

|

Apparatus and instruments

Neurotracker

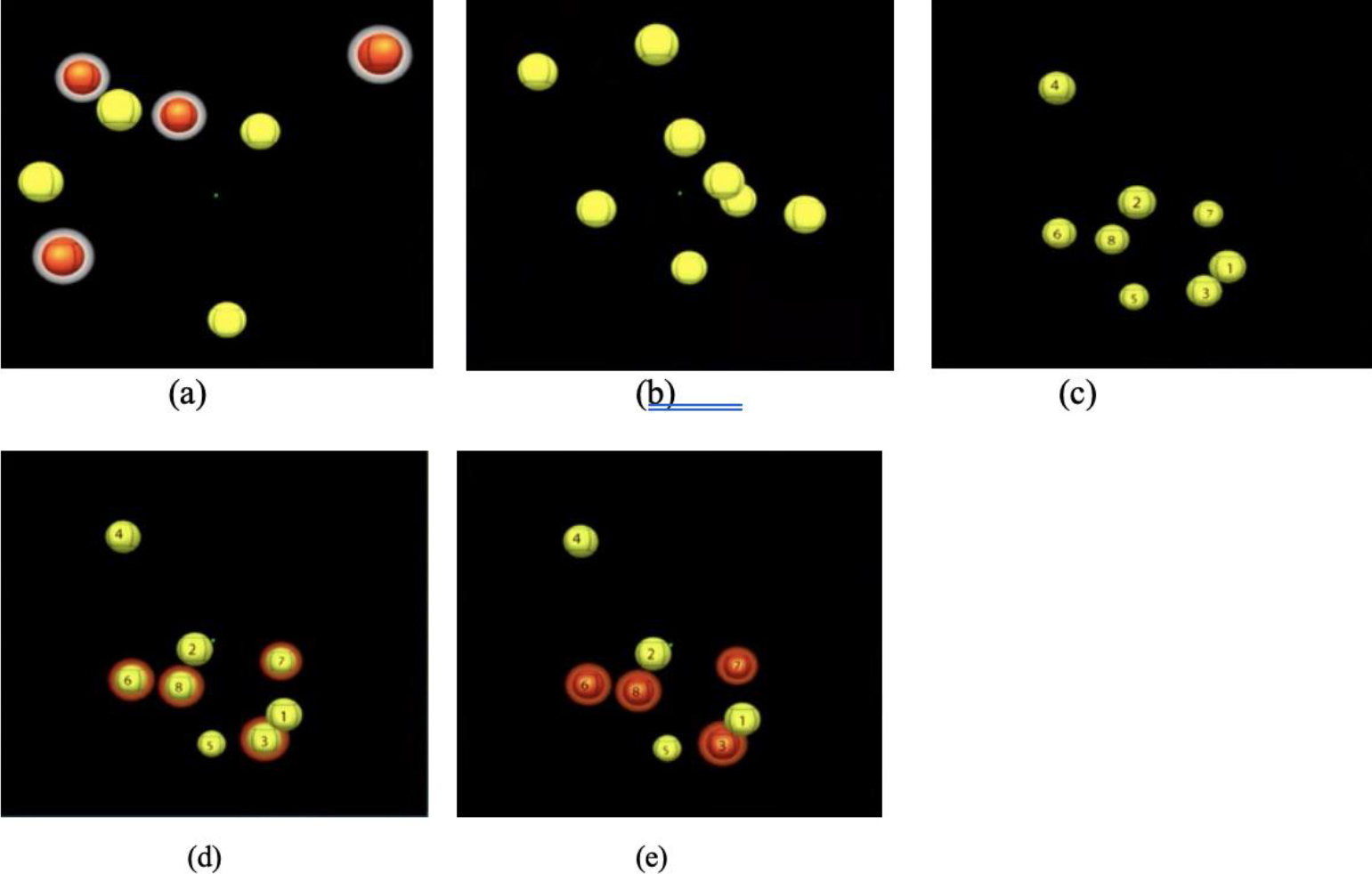

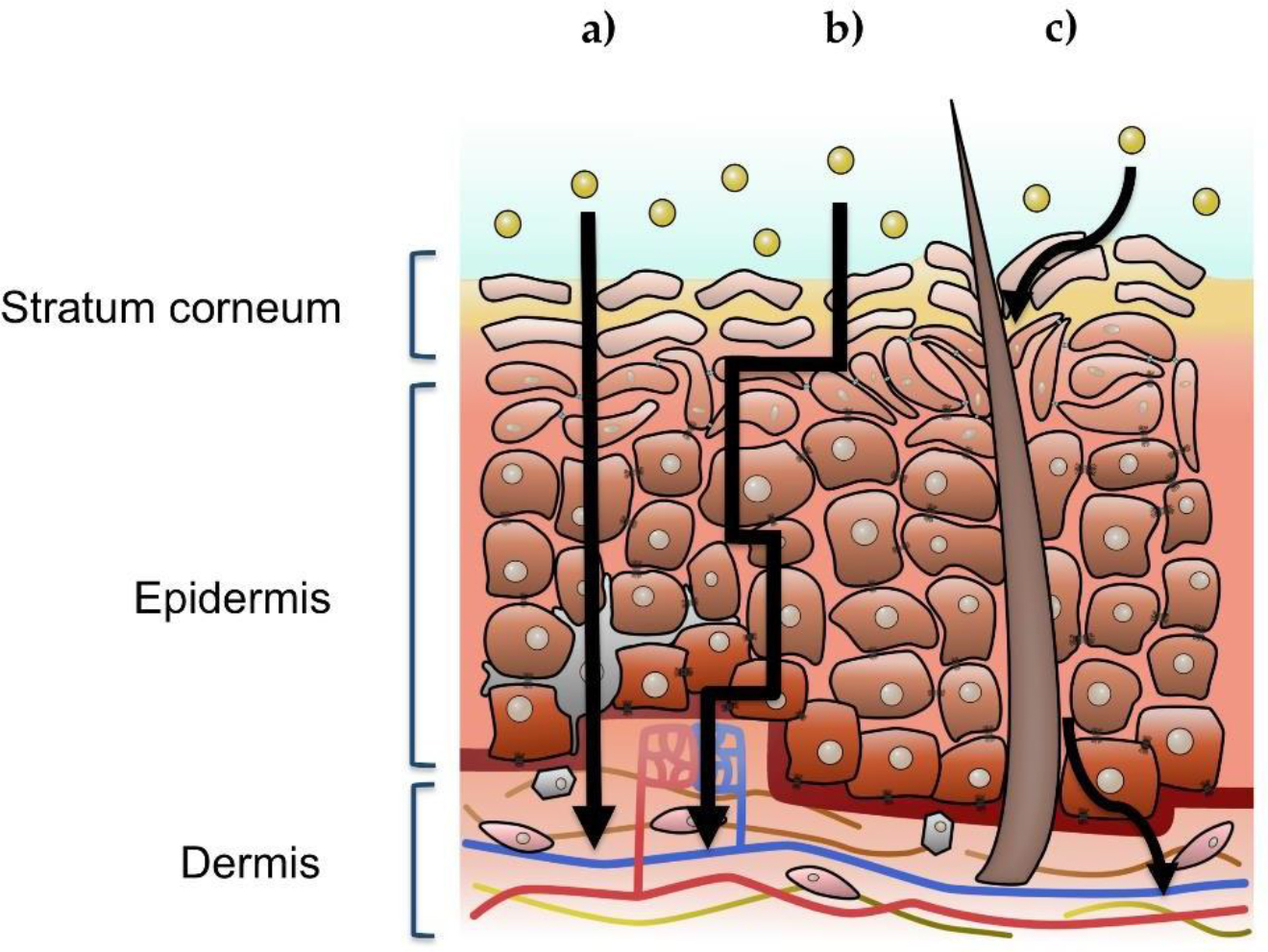

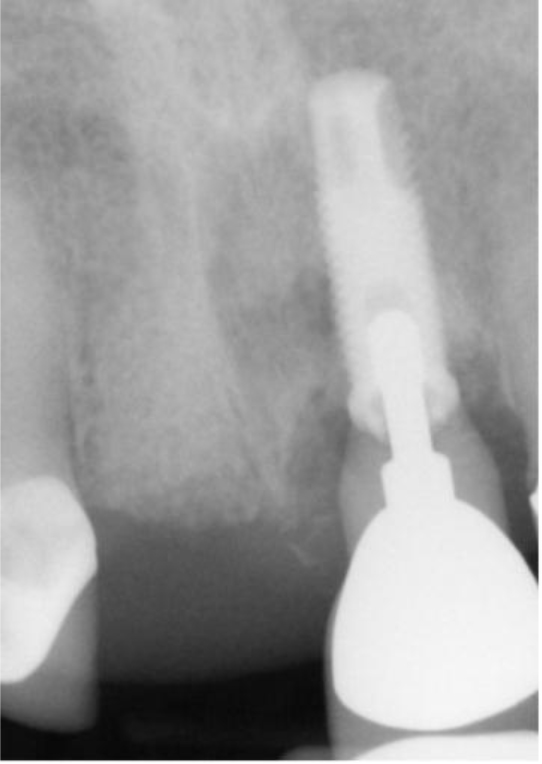

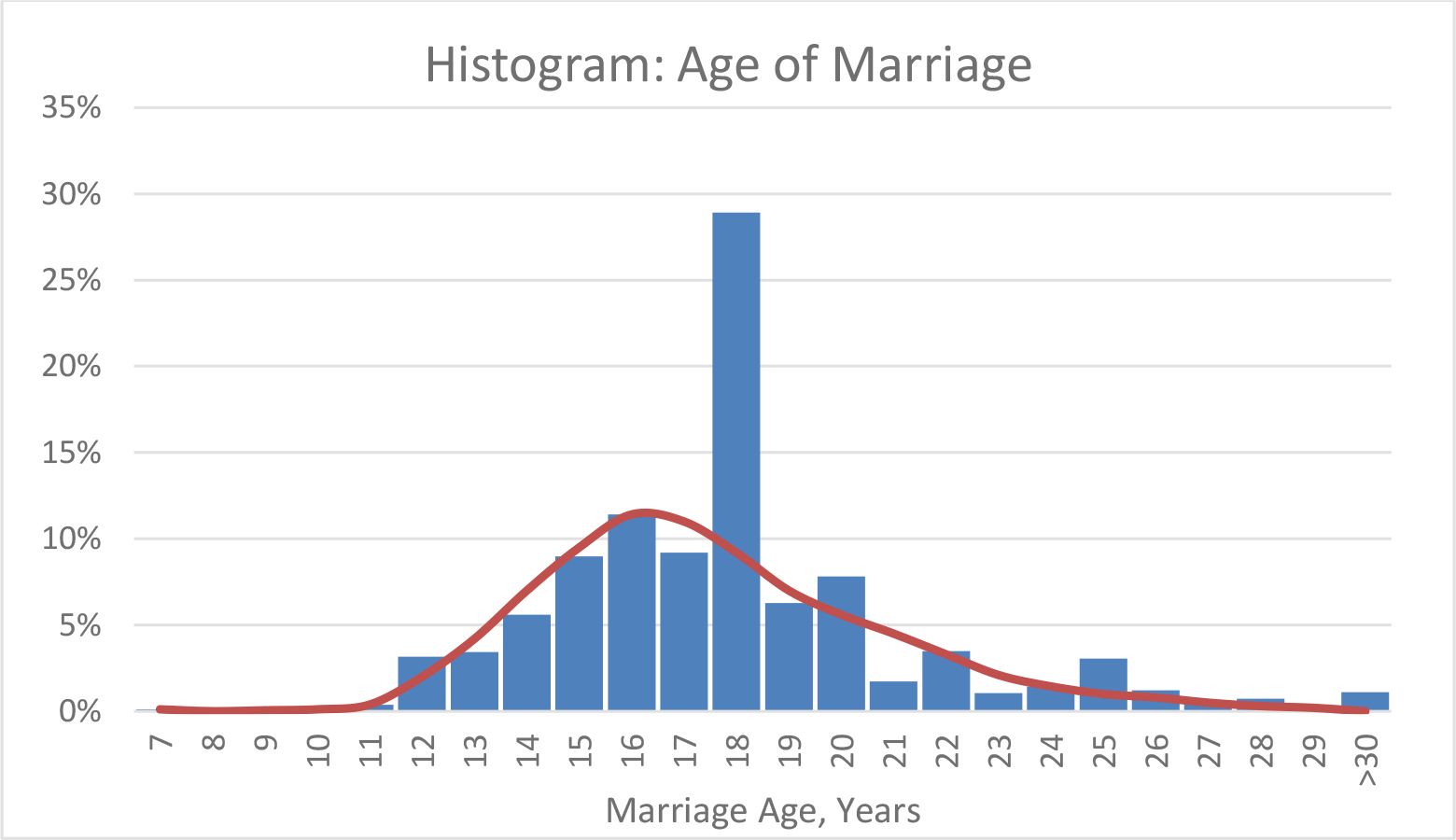

The Neurotracker is a computerized 3D-MOT perceptual-cognitive training system (CogniSens Athletic Inc., Montreal, Canada) that has been used for training cognitive abilities, including selective attention and cognitive flexibility [38]. Only participants in the intervention group completed the Neurotracker. In total, members of the intervention group completed 21 sessions with the Neurotracker. Specifically, each participant completed one appointment per week, and each appointment included three Neurotracker sessions. During each session, eight yellow projected spheres appeared as targets in a 3D volumetric cube in the screen. Four of the eight spheres briefly changed to red, and then reverted to yellow. The four target spheres were to be tracked as they moved in a linear trajectory. Prior to the first session at intake, participants were given verbal instructions on how to complete the Neurotracker task. The sessions were based on a staircase procedure [39], in which an algorithm shifts the speed of the target spheres in response to the participants’ performance. If all targets were correctly identified, the speed of the movement of the spheres increased by 0.05log; with each incorrect response, the speed decreased by 0.05log (see Figure 2 for Neurotracker procedure).

Figure 2. Procedure for completing Neurotracker sessions: (a) balls highlighted in white indicate the four targets to track; (b) targets will revert back to yellow and move randomly in 3D space amongst the distractors for eight seconds; (c) balls will stop moving after eight seconds and numbers will appear on all stimuli; participant uses a keyboard to select the original four targets; (d) the targets will be highlighted once selected (e) once the participant has made their selection, the correct targets will be shown by an orange highlight; the balls will then resume moving and the participant will continue tracking the original targets for the remainder of the session.

The Stroop test

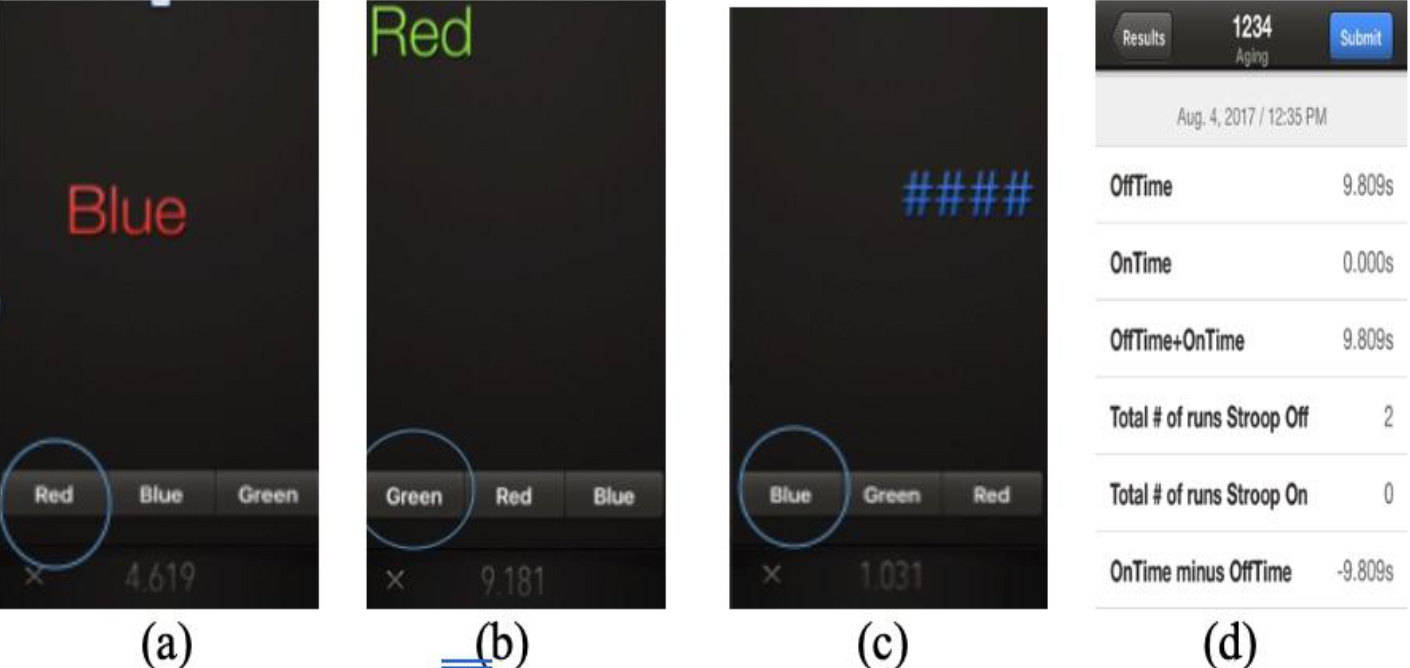

The Stroop test was delivered using the EncephalApp, a smartphone program developed originally to assess cognitive decline associated with hepatic encephalopathy [40]. The Stroop test has been supported as a valid and reliable measure of selective attention and cognitive flexibility [41,42]. In the pencil and paper version, the Stroop task presents an array of different colour words in two tasks. During the first task, the words are presented in a congruent colour (e.g. RED written in red ink). In the second task, they are presented in an incongruent colour (e.g. RED written in blue ink). During the incongruent task, there is a marked increase in response time due to the additional demands on selective attention and inhibition, and increased cognitive interference, a phenomenon referred to as the Stroop effect [43]. The Encephal App adheres to the same mechanism as the classic version, but presents the words one at a time, rather than all at once. Additionally, the order and spatial arrangements of the target words on the screen, and response options at the bottom of the screen, are randomized upon each administration, which has been identified as a potential protective measure against learning effects [44,45].

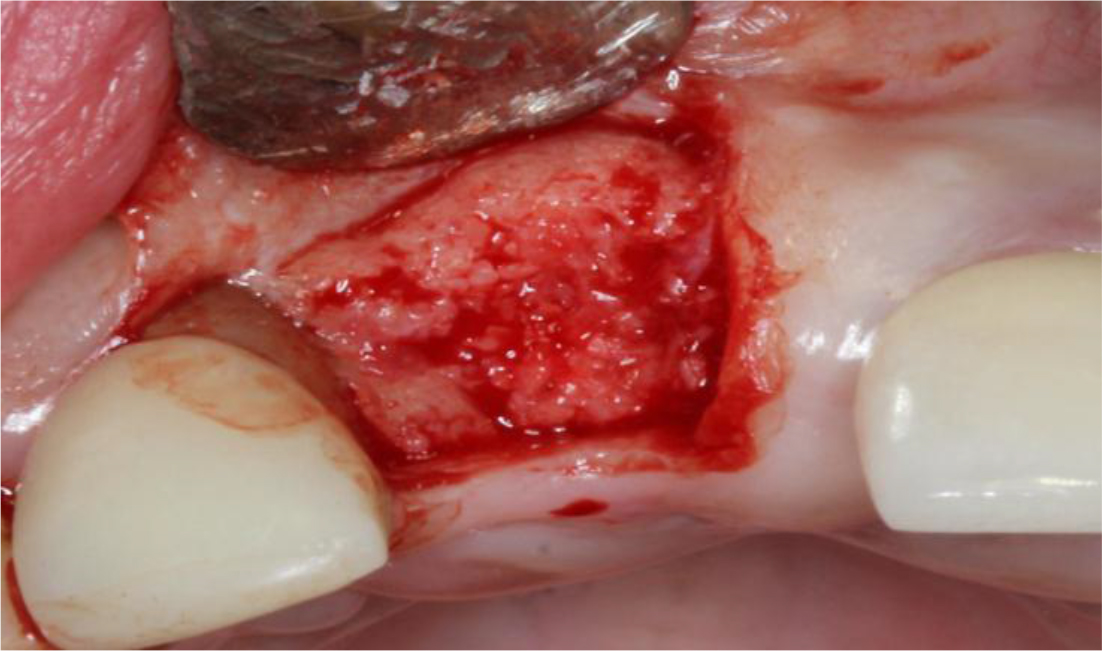

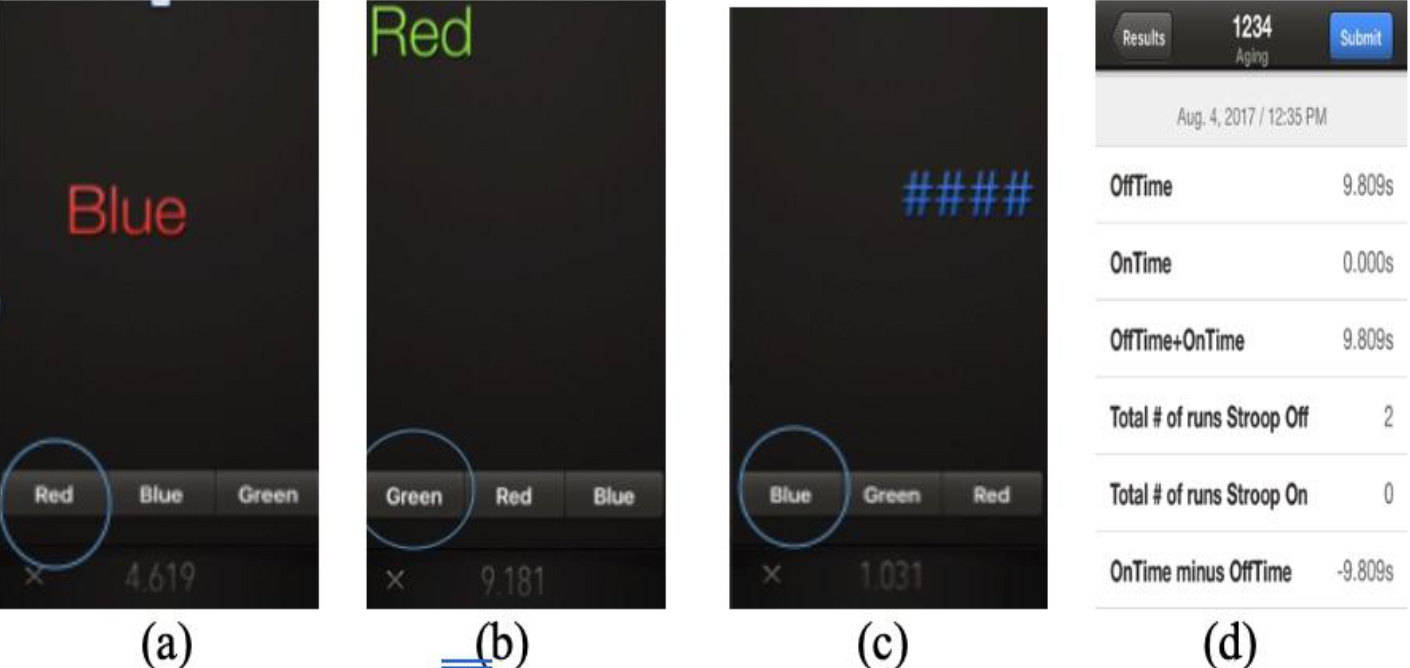

There are two main tasks in the EncephalApp: the Off task, requiring participants to identify the colours of number symbols (#), and the On task, requiring participants to identity the ink colours of words written in an incongruent colour. There were two practice trials that were unscored prior to each timed task. Ten words/symbols were presented during each timed task. Scores were measured based on the time taken to complete a full task without making any errors. If errors were made, the task would restart (Figure 3).

Figure 3. EncephalApp task. (a) and (b) Stroop effect turned on, where participants select the colour of the ink of the presented word, and not the word itself; (c) Stroop effect turned off, where participants select the colour of the ink of the presented symbols. Each session presents ten different symbols/words; sessions will restart when incorrect responses are given; (d) example of data upon completion of Stroop task.

Three scores were recorded. Off-time scores measured psychomotor speed and selective attention; On-Time scores measured psychomotor speed, divided attention, and cognitive flexibility; and On-Time minus Off-Time scores measured cognitive flexibility isolated from psychomotor speed [44] (see appendix B for raw data).

Procedure

The study took place at the University of Victoria Concussion Lab, Victoria, BC. Participants signed up for appointments using the online scheduling software, Web-Appointments. Members of the intervention group came in once a week for eight weeks.

During the first appointment, goals and aims of the study were explained, and participants were asked to read and sign a consent form. Participants completed a brief intake questionnaire that generated participant histories regarding neurological diseases, concussion experiences, and sensory deficits. Demographic measures were also recorded on the questionnaire, and included age, sex, and years of completed education. At intake, a baseline Stroop test, and three sessions with the Neurotracker were completed. The Stroop test was completed pre- and post-training (i.e. at the first appointment, and one week after the seventh session). The Neurotracker was performed at appointments one through seven. Seven appointments with the Neurotracker were chosen due to time constraints of the study and to ensure participant adherence.

At the eighth appointment, participants completed the Stroop test without the Neurotracker. This was required to get a measurement on the Stroop test that was representative of the conditions under which it was done at the intake (i.e. without having done the Neurotracker immediately before, to reduce the effects of mental fatigue from 3D-MOT training).

Members of the control group came in twice, with the appointments separated by seven weeks. At both appointments, participants completed the Stroop test only.

All participants were compensated for any travel costs accrued, including parking and/or bus fare.

Statistical Analyses

The design was a single factor within-group research design. Data was collected and analyzed using the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 23 (SPSS) and Excel. Means and standard deviations were computed for demographics (sex and age), and the mode was computed for level of education (i.e. high school/college, Bachelor’s degree, or Master’s/PhD). A two-tailed paired t-tests were carried out using SPSS for On-Time minus Off-Time scores (cognitive flexibility) from the first and eighth appointments. As the sample consisted of a large number of active bridge players, Spearman’s rho correlations were computed for bridge players and non-bridge players and Stroop scores, to examine whether there was a correlation between active engagement in mentally stimulating activities and performance on the Stroop test, based on existing research demonstrating increased cognition in older adults who participate in these activities [46, 47]. Statistical correlations were thus calculated to assess whether this was an extenuating variable. Spearman’s rho correlations were also computed for sex and Stroop scores, and education level and Stroop scores. Pearson’s correlations were calculated for age groups (62–69 years old, 70–73 years old, and 74 and older) and Stroop scores, to assess the relationship between advanced ages and the degree of cognitive improvement following the Neurotracker intervention.

A second t-test was performed to test the hypothesis that psychomotor speed was significantly different following the intervention, as measured by the Off-Time conditions. Three paired t-tests were also performed on Stroop scores recorded for the control group. A paired t-test also demonstrated that there was no significant difference on Stroop test performance pre-intervention comparing the experimental group with the control group.

To verify whether Stroop test scores improved after seven sessions of 3D-MOT training, a two-tailed paired sample t-test was performed using SPSS. Scores obtained from the Stroop effect Off-Time condition (i.e. identifying the colour of number signs) represented psychomotor speed and were analyzed pre- and post-intervention. Scores obtained from the Stroop effect On-Time condition (i.e. identifying the ink colour of discordant-coloured stimuli) represented cognitive flexibility and psychomotor speed, and were analyzed pre- and post-intervention. Scores obtained from the On-Time minus Off-Time condition represented cognitive flexibility isolated from psychomotor speed, and were analyzed pre- and post-intervention.

Results

A Shapiro-Wilk test [48] and a visual inspection of their box plots showed that the Stroop scores for the On-Time minus Off-Time condition were normally distributed (p = .181). The skewness value of -.321 (SE = .464) and kurtosis of -.803 (SE = .902) were conducted to assess the assumption of normality pre- and post-training. These values met the criteria outlined by West, Finch, and Curran [49] of skewness and kurtosis values within ± 2 to demonstrated normality.

Pre-Intervention

Prior to 3D-MOT training, the mean Stroop test score for the intervention group participants was 77.23 (SD = 13.33) for Off-Time, and 92.05 (SD = 17.35) for On-Time. The mean score for On-Time minus Off-Time was 14.83 (SD = 9.30).

At baseline, the mean Stroop test scores for the control group was 80.88 (SD = 11.75) for Off-Time, 90.32 (SD = 24.96) for On-Time, and 16.36 (SD = 17.90) for On-Time minus Off-Time. There was no significant difference in Stroop test performance between the experimental and control group pre-intervention.

Post-Intervention

To test the hypothesis that cognitive flexibility was statistically different following the intervention, as measured by the On-Time minus Off-Time conditions, a dependent samples t-test was performed for both the experimental and control group (Table 2).

Table 2. Average Stroop test scores in seconds at baseline and 8 weeks post-intervention. The Neurotracker group post-intervention scores were measured following 21 training sessions using 3D-multiple object tracking over 7 weeks. The control group received no 3D-MOT training.

|

Control (n = 21)

|

Neurotracker group (n = 25)

|

|

EncephalApp results, baseline (mean ± SD)

|

|

|

|

Total Off-Time, sec.

|

80.88 ± 11.75

|

77.23 ± 13.33

|

|

Total On-Time, sec.

|

90.32 ± 24.96

|

92.5 ± 17.35

|

|

Total On-Time minus Off-Time, sec.

|

16.36 ± 17.90

|

14.86 ± 9.30

|

|

EncephalApp results, post-intervention (mean ± SD)

|

|

|

|

Total Off-Time, sec.

|

79.89 ± 11.19

|

72.33 ± 12.18*

|

|

Total On-Time, sec.

|

82.59 ± 35.99

|

82.66 ± 12.75**

|

|

Total On-Time minus Off-Time, sec.

|

25.75 ± 25.73

|

9.80 ± 6.84+

|

|

Notes: * = p = .002; ** = p < .001; + = p = .006

|

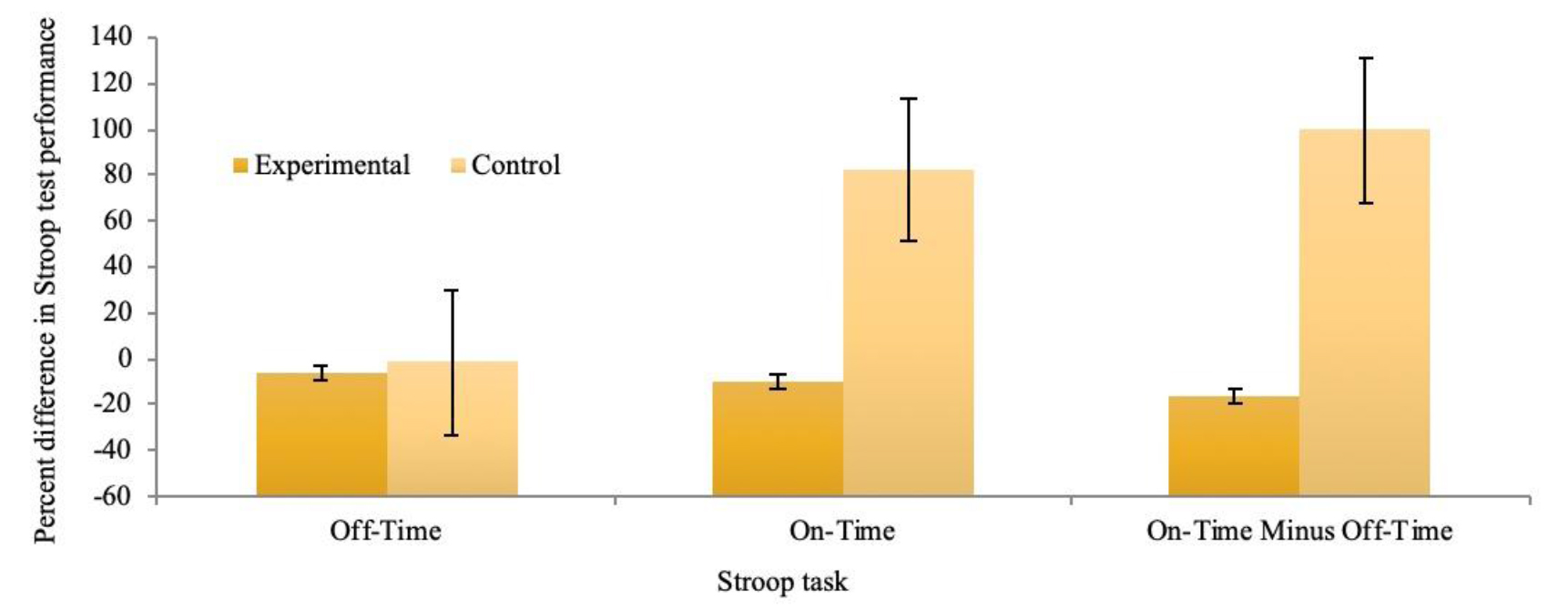

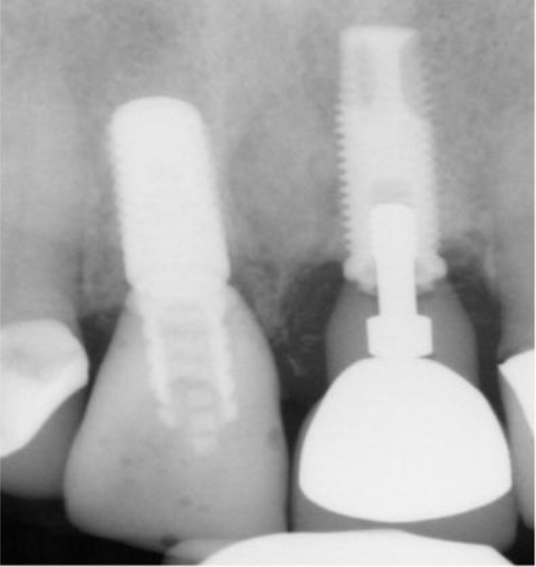

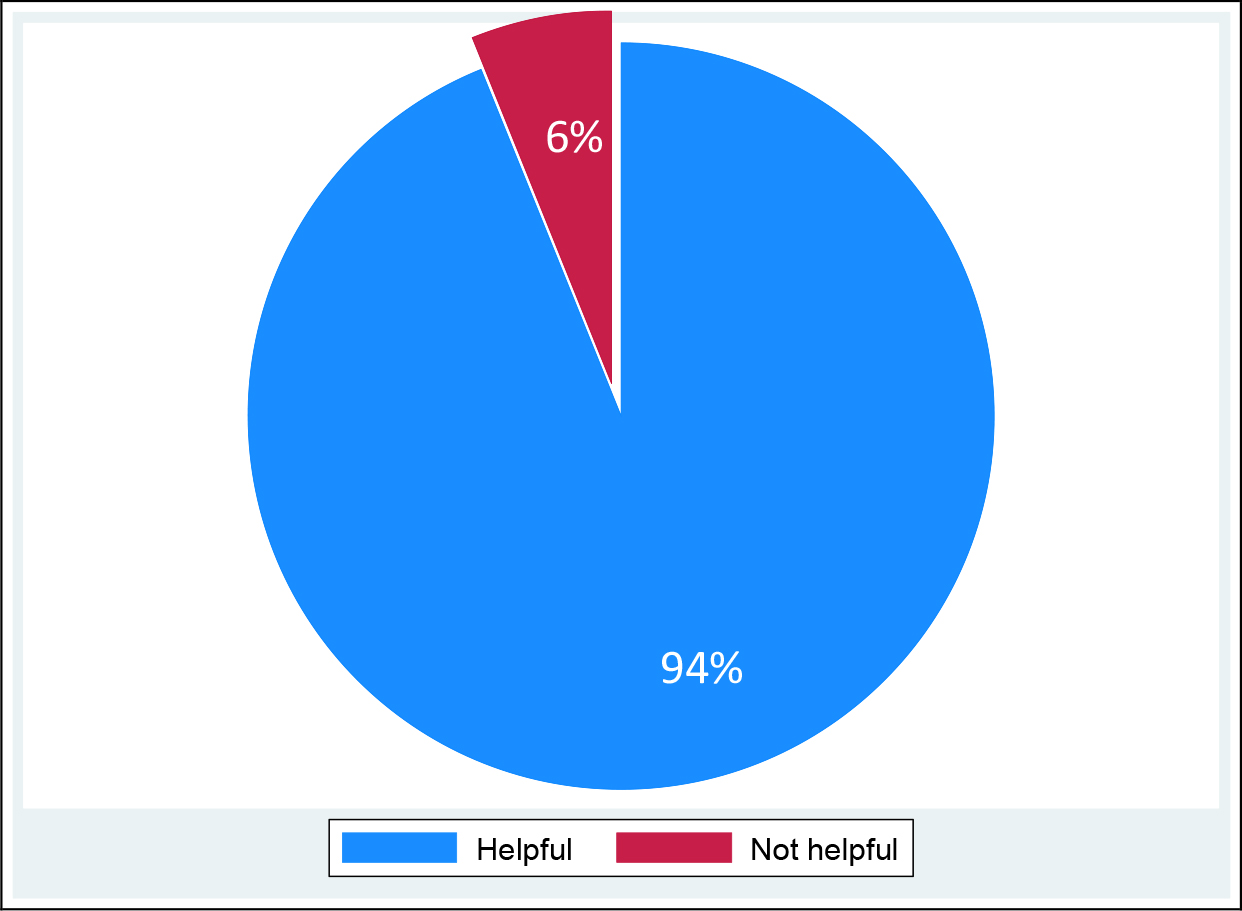

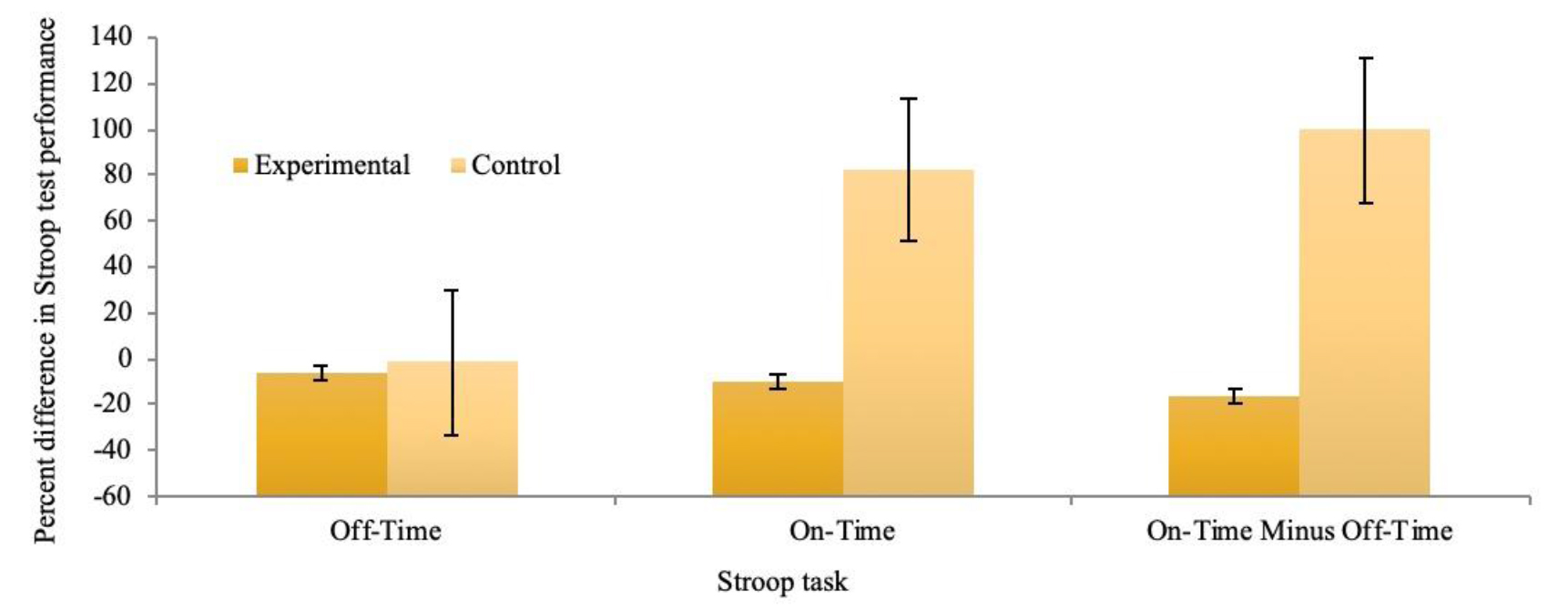

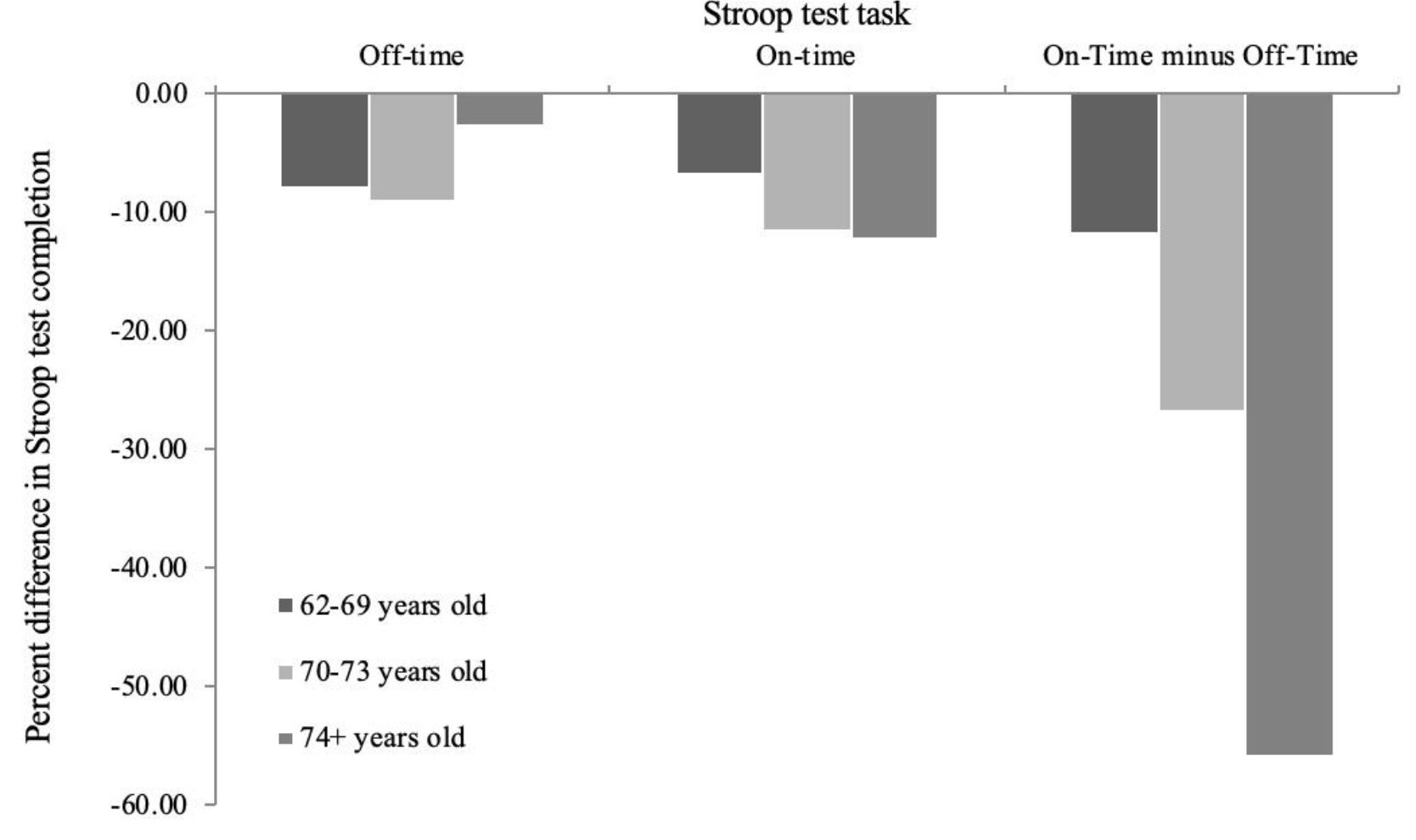

On average, the time taken to complete the Stroop test for the On-Time minus Off-Time condition significantly decreased between the initial appointment and final appointment for the experimental group (M = 5.01, SD = 7.19, SE = 1.44, CI [2.04, 7.97]), t(24) = 3.48, p = .002). Participants who completed 3D-MOT training demonstrated a 33.76% improvement in On-Time minus Off-Time scores, which was significantly greater than the control group (see figure 4).

Figure 4. Percent difference in 3 Stroop test tasks between initial appointment and 8 weeks later. The experimental group completed 21 sessions of 3D-multiple object tracking training over a 7-week period. The control group received no intervention.

A Cohen’s d value of 3.06 indicated a large effect size [50]. A second t-test was performed to test the hypothesis that psychomotor speed and selective attention were significantly different following the intervention, as measured by the Off-Time conditions. On average, the time taken to complete the Stroop test in the Off-Time condition significantly decreased from the initial appointment (M = 4.90, SD = 7.12, SE = 1.44, CI [1.94, 7.86]), t(24) = 5.41, p = .002. Participants who completed 3D-MOT training demonstrated a 6.24% improvement Off-Time scores, which was significantly greater than the control group (see figure 4).

A third t-test was performed to test the hypothesis that psychomotor speed and cognitive flexibility were statistically different following the intervention, as measured by the On-Time conditions. On average, the time taken to complete the Stroop test decreased significantly following the intervention (M = 9.39, SD = 8.68, SE = 1.74, CI [5.81, 12.98]), t(24) = 5.41, p > .001. Participants who completed 3D-MOT training demonstrated a 10.20% improvement in On-Time, which was significantly greater than the control group (see figure 4).

Three paired t-tests were performed on Stroop scores recorded for the control group. No significant changes were found in the On-Time, Off-Time, or On-Time minus Off-Time scores at week 8.

Post–hoc demographic comparisons

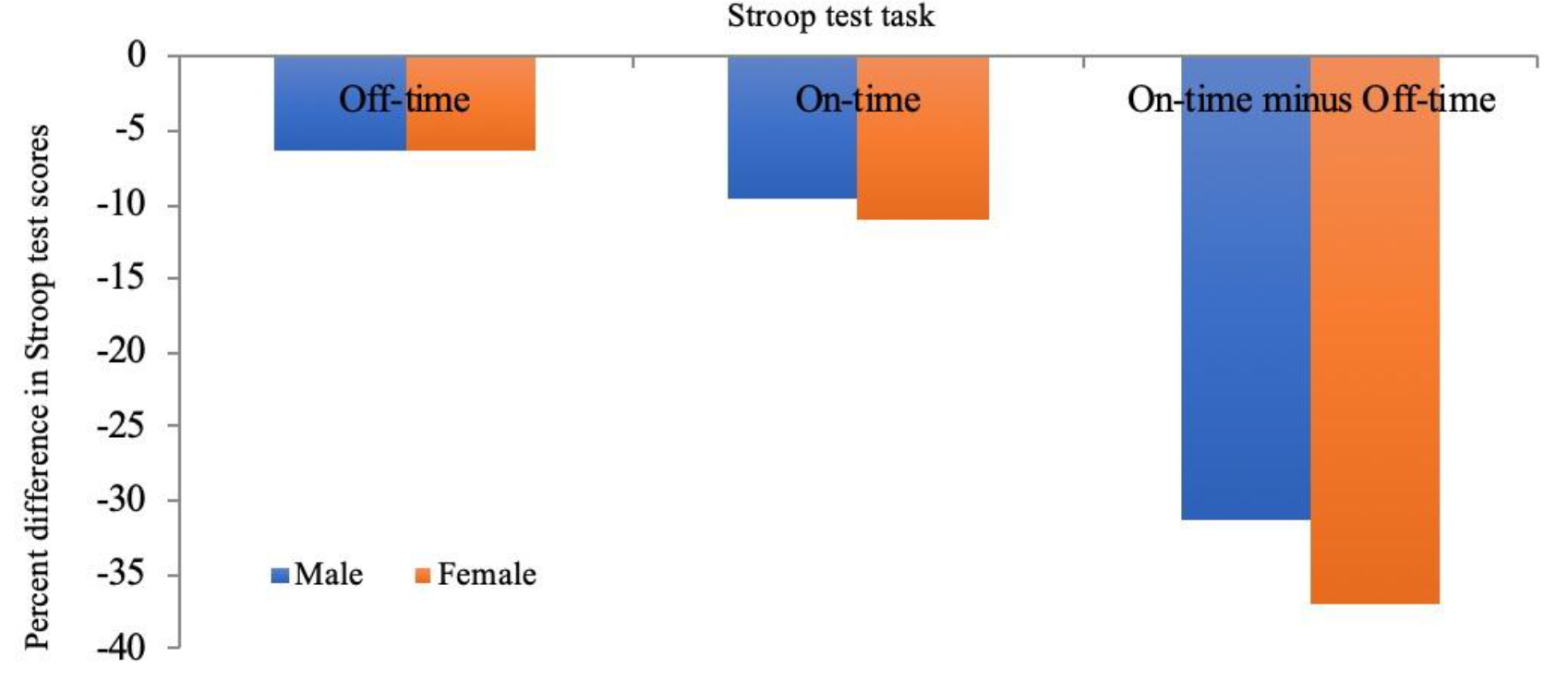

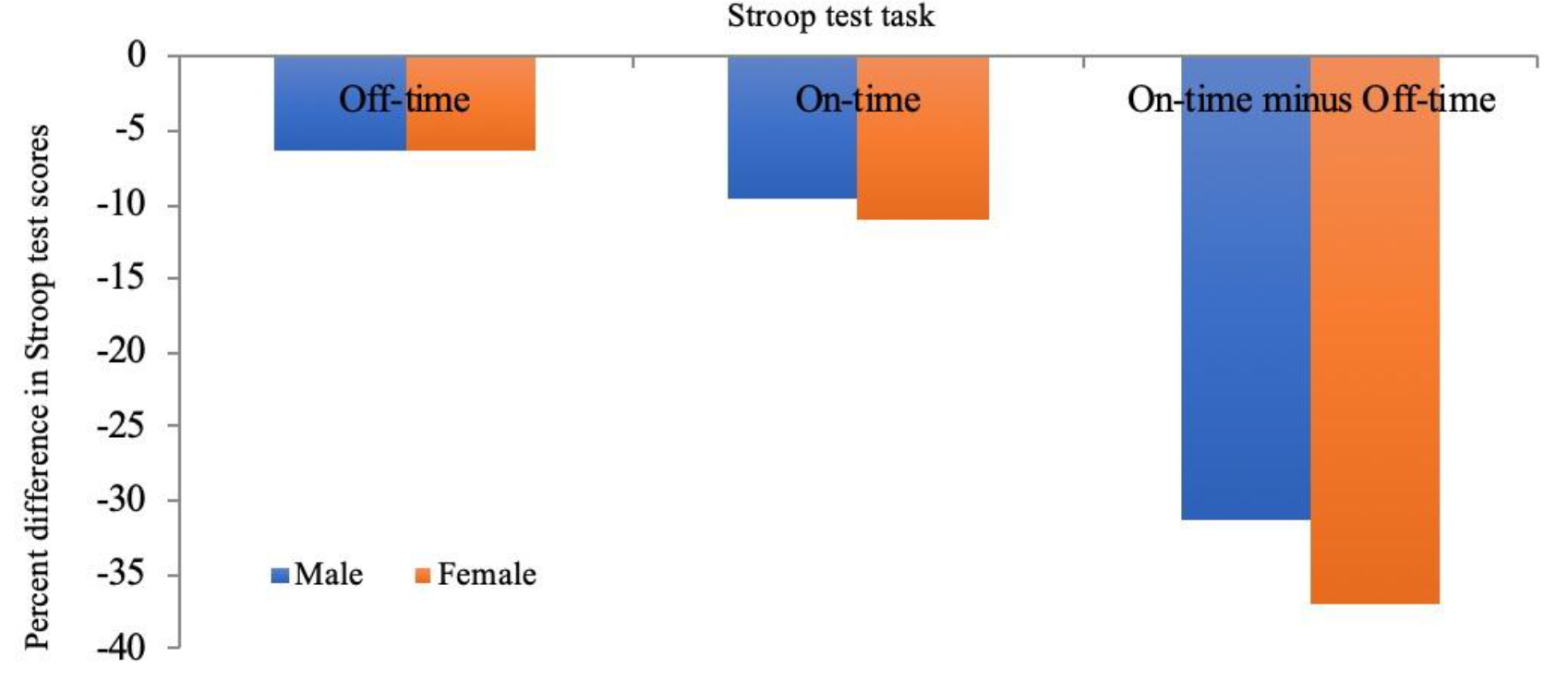

Sex

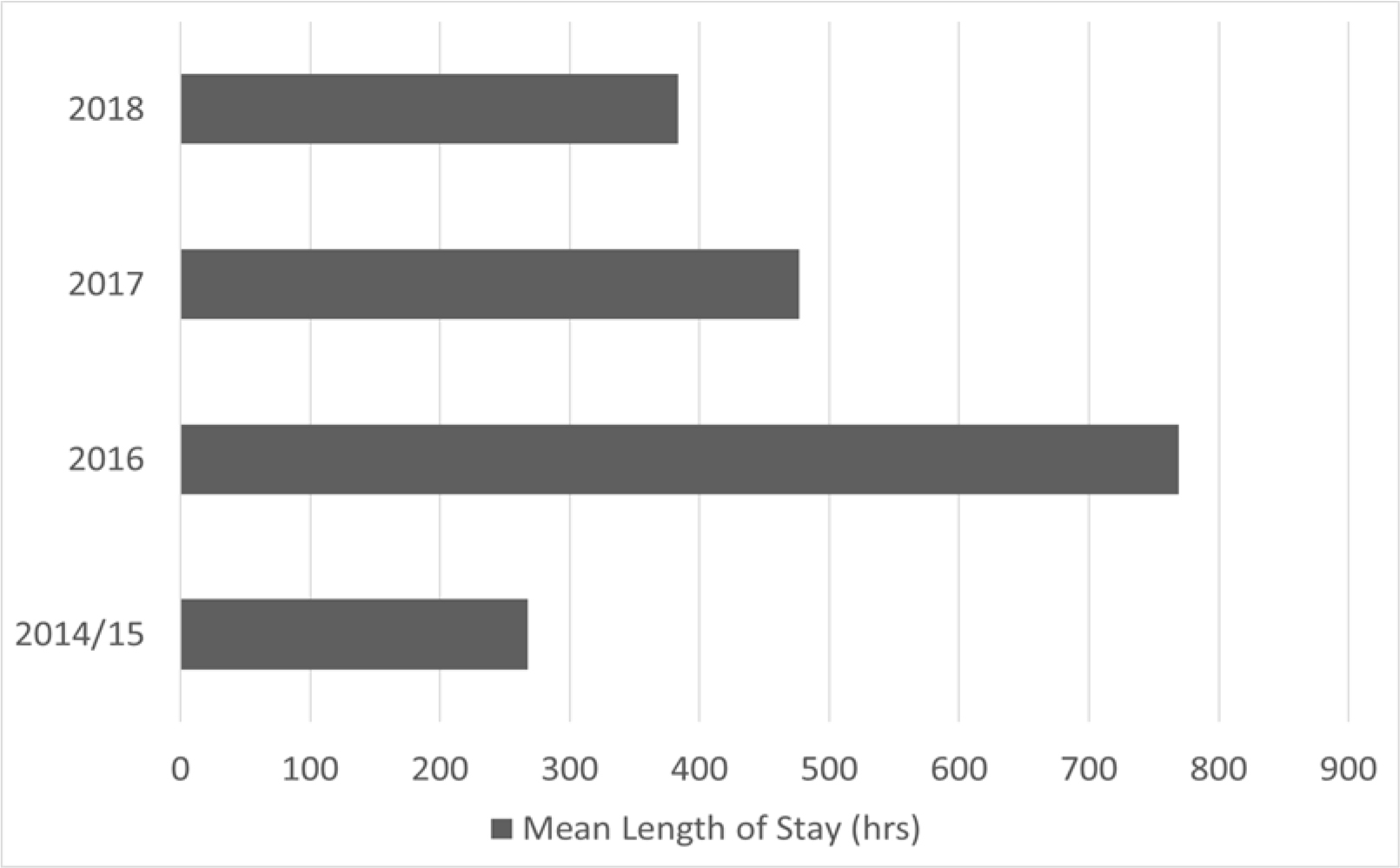

Scores were further analyzed to assess the influence of sex on Stroop test On-Time minus Off-Time scores. Prior to 3D-MOT training, there were significant sex differences in Stroop scores for the On-Time and Off-Time conditions, while there were no significant differences for the On-Time minus Off-Time condition. Following 3D-MOT training, these sex differences were maintained, with significant sex differences found in the On-Time (p < .001) and Off-Time (p = .004) conditions but not in the On-Time minus Off-Time conditions (see Figure 5 for percent differences in Stroop test scores as a factor of sex).

Figure 5. Percent differences in Stroop test task completion following 21 sessions of 3D-multiple object tracking completed over a 7-week period as a factor of sex.

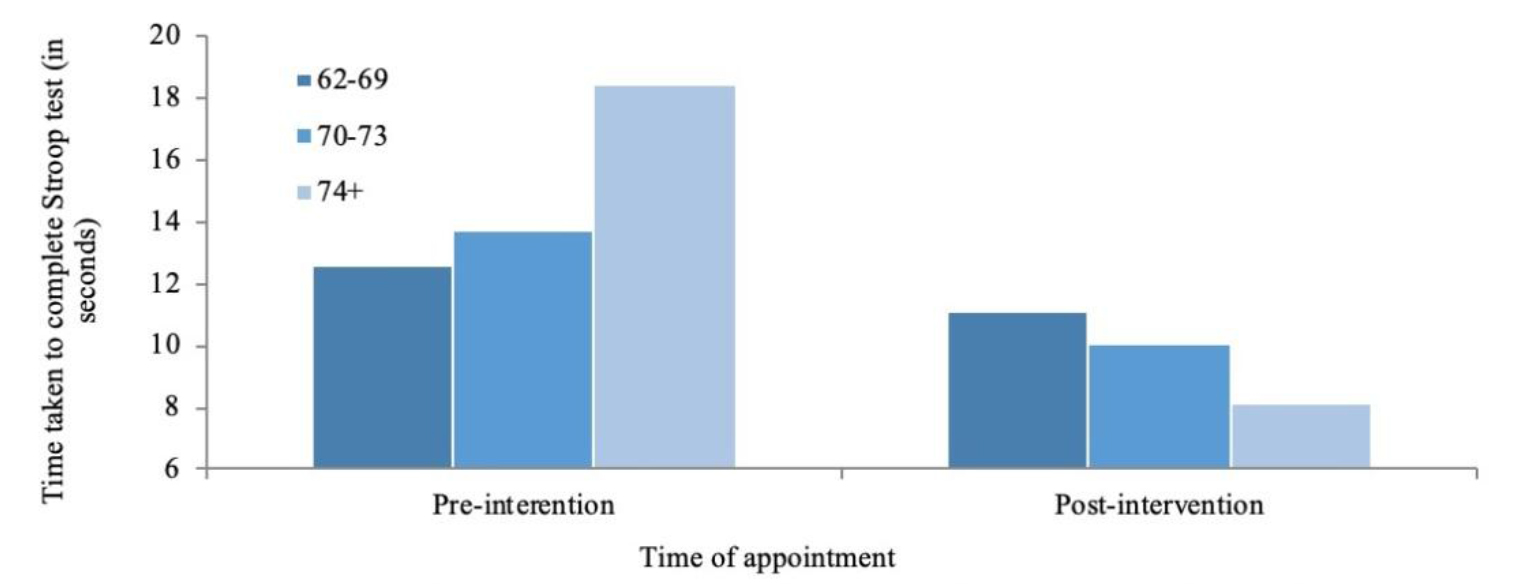

Age

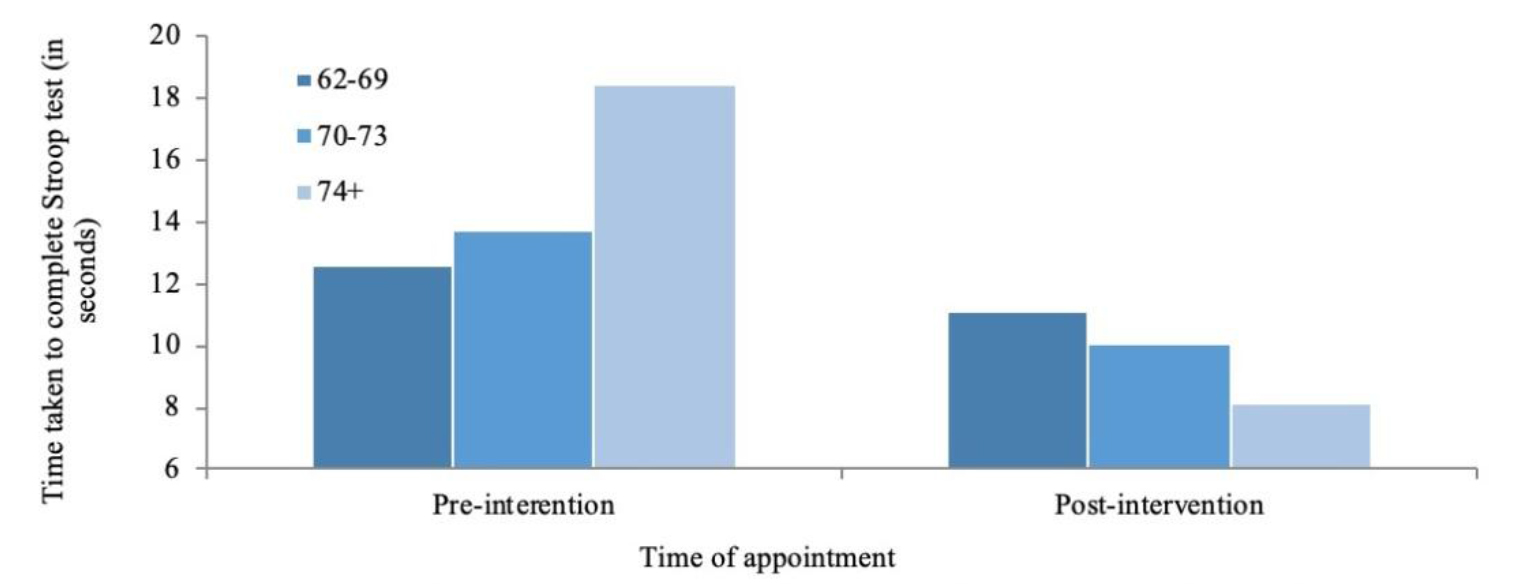

Scores were further analyzed to assess the influence of age on Stroop test On-Time minus Off-Time scores. Participants were divided into 3 age groups: 62–69 (n = 9), 70–73 (n = 8), and 74 years and older (n = 8). Participants were categorized into these age groups as these groupings allowed within-group variation to be minimized.Prior to 3D-MOT training, participants in the 74 and older group took the longest to complete the Off-Time (M = 83.85, SD = 14.18), On-Time (M = 102.33, SD = 14.80), and On-Time minus Off-Time conditions (M = 18.47, SD = 10.89) (Table 3).

Table 3. Average changes and percent differences in Stroop test scores as a factor of age at baseline and post-intervention for 3D-multiple object tracking training group and control group.

|

Baseline (mean ± SD)

|

Post-intervention (mean ± SD)

|

Difference (%)

|

|

Stroop test tasks

|

Control

|

3D-MOT training

|

Control

|

3D-MOT training

|

Control

|

3D-MOT training

|

|

Off-Time

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Age

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

62–69

|

76.86 ± 9.57

|

71.66 ± 6.14

|

73.48 ± 9.90

|

66 ± 4.96

|

-4.39

|

-7.82

|

|

70–73

|

76.41 ± 11.80

|

76.93 ± 16.55

|

76.66 ± 7.54

|

70.08 ± 11.24

|

0.33

|

-8.90

|

|

74+

|

86.49 ± 12.04

|

83.85 ± 14.18

|

85.03 ± 11.85

|

81.69 ± 14.03

|

-1.69

|

-3.90

|

|

On-Time

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Age

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

62–69

|

75.8 ± 35.30

|

84.18 ± 11.87

|

86.4 ± 10.82

|

78.54 ± 9.78

|

13.98

|

-6.70

|

|

70–73

|

90.4 ± 11.46

|

90.63 ± 21.20

|

92.55 ± 17.36

|

80.12 ± 11.99

|

2.38

|

-11.60

|

|

74+

|

101.56 ± 15.21

|

102.33 ± 14.80

|

99.82 ± 18.36

|

89.83 ± 14.71

|

-1.71

|

-12.22

|

|

On-Time minus Off-Time

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Age

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

62–69

|

19.83 ± 23.40

|

12.58 ± 7.36

|

12.92 ± 7.54

|

11.1 ± 8.35

|

-34.85

|

-11.76

|

|

70–73

|

13.99 ± 6.01

|

13.70 ± 9.66

|

15.95 ± 12.88

|

10.05 ± 4.51

|

14.01

|

-26.64

|

|

74+

|

14.97 ± 18.87

|

18.47 ± 10.89

|

15.44 ± 12.94

|

8.15 ± 7.42

|

3.14

|

-55.87

|

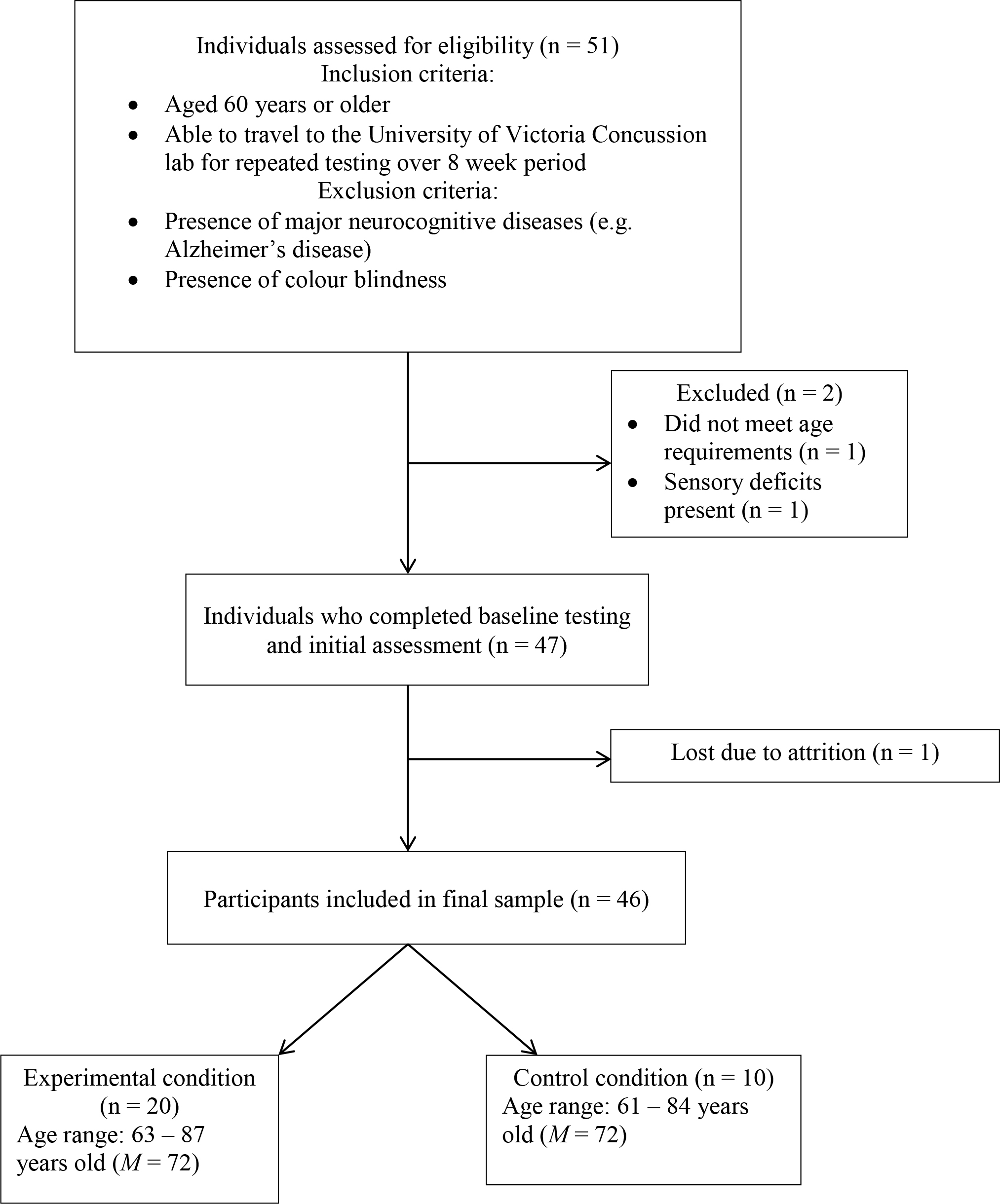

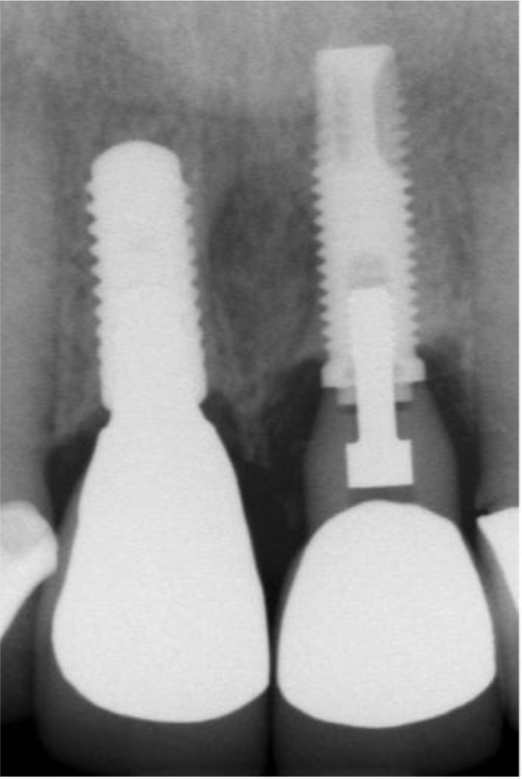

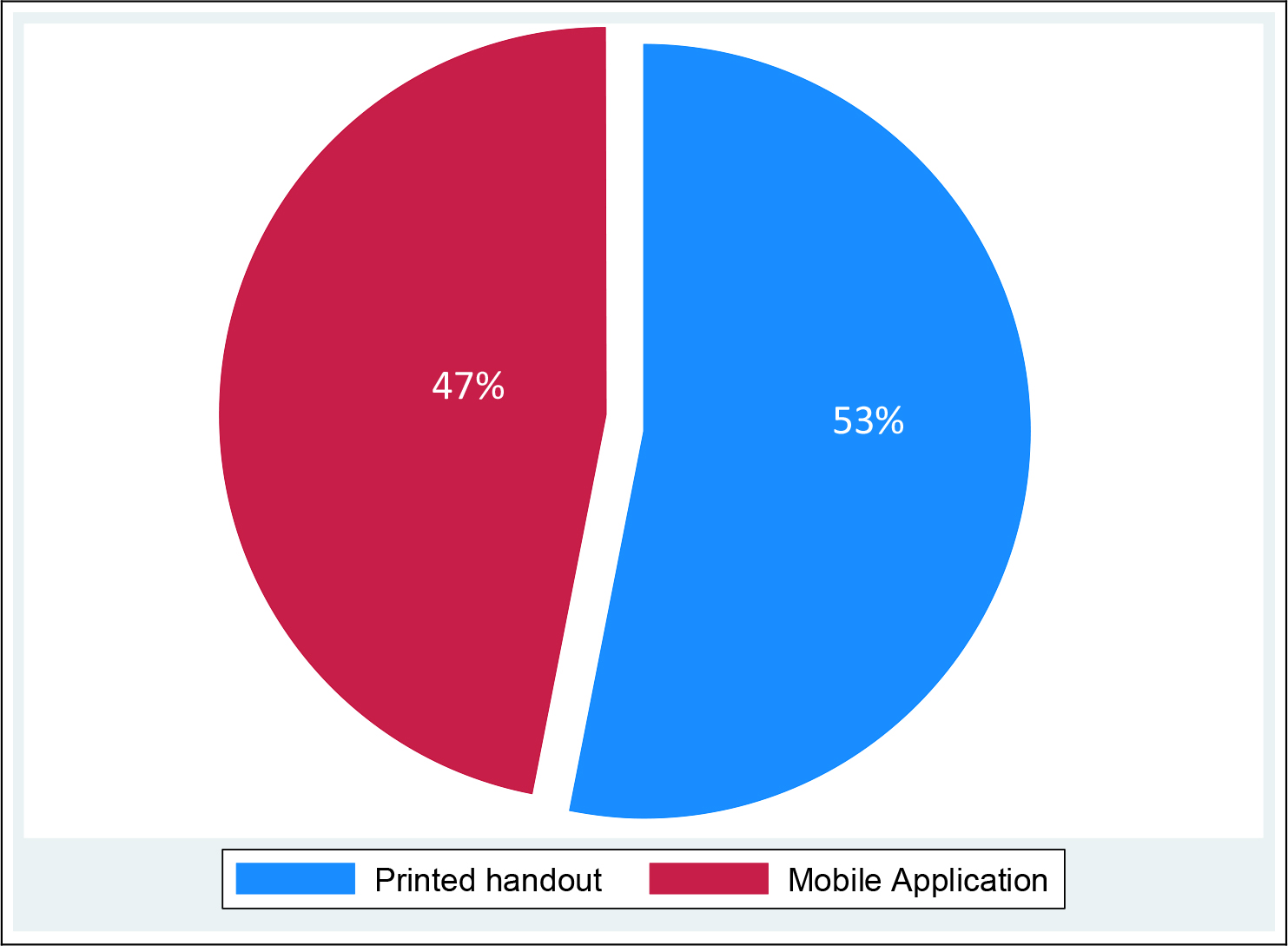

Following 3D-MOT training, the 74 and older group had the highest scores in the Off-Time (M = 81.69, SD = 14.03) and On-Time (M = 89.83, SD = 14.71) conditions, while participants in the 62–69 year old group had the highest scores in the On-Time minus Off-Time condition (M = 11.1, SD = 8.35) (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Changes in time take to complete the Stroop test On-Time minus Off-Time condition as a factor of age. Scores were taken once at baseline and again 8 weeks later following 21 sessions of 3D-multiple object tracking over a 7 week period.

Percent differences were calculated for the different age groups to measure improvement in Stroop test completion post-intervention following 21 training sessions on the Neurotracker. The 70–73 year old group had the largest percent decrease in time taken to complete the Stroop test Off-Time conditions (-8.90%), while the 74+ year old group had the largest percent decrease in time taken to complete the On-Time (-12.21%) and On-Time minus Off-Time (-55.90%) conditions (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Percent differences in Stroop test completion between baseline and following 21 sessions of 3D-multiple object tracking training over 7 weeks, as a factor of age.

Education

Scores were further analyzed to assess the influence of education level on Stroop test On-Time minus Off-Time scores. A Pearson’s correlation measurement showed that there was no significant correlation between education level and Stroop test performance pre- or post-intervention.

Discussion

The purpose of this pilot study was to evaluate the effect of 3D-multiple object tracking (MOT) training on selective attention and cognitive flexibility in the healthy aging population. Baseline Stroop test scores were assessed at the initial appointment, and again at the eighth week following 21 sessions of 3D-MOT training on the Neurotracker. Stroop scores were broken down to consider specific cognitive functions including selective attention, cognitive flexibility, and psychomotor speed. A control group was also assessed by measuring baseline Stroop test scores at the first appointment, and again at the eighth week without participating in the Neurotracker intervention. By measuring the effects of the Neurotracker pre- and post-intervention, it was hypothesized that Stroop test On-Time minus Off-Time scores would change, indicating an alteration in cognitive flexibility [42,44]. The hypothesis was supported; there was significant improvement in On-Time minus Off-Time scores following 3D-MOT training. Furthermore, scores for On-Time, measuring psychomotor speed plus cognitive flexibility, significantly improved, as did scores for the Off-Time condition, measuring psychomotor speed and selective attention. Additionally, there were no significant changes in Stroop scores measured in the control group, supporting the influence of 3D-MOT training on Stroop performance. These results suggest that weekly training sessions with the Neurotracker may improve selective attention and cognitive flexibility in older persons. There was no significant correlation between education levels and Stroop scores, consistent with previous research [44].

The improvement in cognitive performance in this study, as indicated by changes in Stroop test scores, is consistent with previous research demonstrating that customized video games serve as powerful tools to enhance cognitive control [51], processing speed [52], task switching, and working memory [53]. The current study expands on these findings by demonstrating additional benefits of computer training on selective attention, cognitive flexibility, and psychomotor speed. Two mechanisms may underlie the effect of 3D-MOT training to improve cognitive performance: isolation and overload [24,54]. Isolation refers to a limited and consistent number of cognitive abilities employed during 3D-MOT training. Overload refers to an adaptive increase in training difficulty, thereby continually challenging the participant beyond their current ability. Neurophysiological adaptation may explain the benefits of overload for cognitive-perceptual enhancement across the lifespan, and has been well documented [13,51,55].

The improvement in attention specifically, as indicated by significant decreases in On-Time minus Off-Time Stroop scores, may be due to increased activation of the neural structures and circuits employed during multiple object tracking. Increased activation in the dorsal frontoparietal attention network, and the intraparietal sulcus in particular, has been recorded by fMRI during 3D-MOT training. These neural areas are heavily involved during tasks of attending to multiple stimuli. Furthermore, a causal link has been established between increased activation of the intraparietal sulcus and improvement on MOT tasks. It is possible, then, that increased isolation and overload of these neural areas during Neurotracker completion may be responsible for improvements in attention, as measured by changes in On-Time minus Off-Time scores in the 3D-MOT training group.

A change in psychomotor speed and selective attention, as measured by Off-Time scores, was significant. This is consistent with previous research that has reported improvements in psychomotor speed following computerized cognitive interventions [19,56,57]. There is limited research, however, on changes in psychomotor speed following 3D-MOT in particular. Fragala and colleagues [58] found no significant changes in psychomotor speed, as measured by reaction time, following training with the Neurotracker. However, due to the small sample sized used in the current study, further replication is necessary to accurately assess psychomotor speed changes.

Participants in the 74 and older group had overall slower Stroop test scores compared to participants aged 62–73 years old. These results are consistent with previous research reporting decreased cognitive flexibility, attentional networks, and psychomotor speed in the oldest adults [59–61]. However, an interesting finding was the amount of improvement observed in the oldest participants; participants aged 74 and older demonstrated a significantly greater magnitude of improvement across all measurements of the Stroop test compared to younger participants, despite having overall slower scores. These results indicate that, even with a decrease in overall performance on cognitive tasks with age, learning capacity may be well preserved [62].

The age-related differences in Stroop test improvement reported in this study, however, are inconsistent with previous research [63–65], which reported plasticity and learning capacity in the oldest age groups, but at reduced levels compared to younger old adults. It is like that the sample size employed in this study was not large enough to statistically analyze distinct age groups; future research could benefit from measuring cognitive performance and learning capacity in the oldest of old following 3D-MOT training. Moreover, all members over the age of 74 years old self-reported high levels of exercise and involvement in mentally stimulating activities, such as the card game, Bridge. It is well documented that enhanced neuroplasticity is correlated with physical and mental exercise [66–68] and it is possible that, due to this, the oldest participants simply had a higher capacity for improvement, resulting in an increased learning curve. As this was a pilot study, these results should be interpreted with caution and future replication is needed to ensure reliability and validation.

Limitations

The findings may be limited by the use of the Stroop test twice throughout the course of the current study. Carryover effects may have influenced the results [69, 70]. However, Rosenbaum and colleagues [39] argue that the Stroop test is resistance to practice effects, reasoning that the randomized order of colour, spatial location, and words throughout each version of the test reduce practice effects. Furthermore, Bajaj et al. [44] demonstrated that healthy controls completing the EncephalApp showed no changes in scores across administration of the test when separated by a one-month period. This was seen as well in scores of the control group of the current study, who received no intervention. Taken together, these findings support the resistance of the Stroop test to practice effects and increase confidence that the changes in Stroop test performance observed in the current study are related to 3D-MOT training.

Additionally, the sample size employed for both the control and experimental group may limit the generalizations that can be made from these findings to the greater population of older adults. Further research would benefit from employing larger number of participants to increase confidence in the reliability and validity of the findings.

Another limitation of this study was the limited time allocated to Neurotracker training sessions. Twenty-one sessions of 3D-MOT training administered over the course of 7 weeks was selected due to time constraints. However, previous research has demonstrated that a plateau in 3D-MOT scores occurs around week ten in healthy young adults, and may take longer to reach in the older population. It may be that further 3D-MOT training could result in greater improvements on the Stroop test, indicating greater gains in attentional ability.

Notably, the use of only one cognitive task limited the findings. Though the Stroop test has been supported as an accurate measure of attention and cognitive flexibility, the results should be replicated by further research to ensure reliability. As this was a pilot study, and there is, to our knowledge, limited research on the use of the Neurotracker as an enhancement tool for selective attention and cognitive flexibility in the older population, future research would benefit from assessing transfer effects of daily activities that are affected by age-related declines in these cognitive areas. An additional limitation relates to the use of self-reporting on neurodegenerative disease history. In the early stages of dementia, the individual may lack insight into the cognitive changes that are occurring [71]. Therefore, the use of self-reporting may not have been a true measure of cognitive status. In the future, research would benefit from using a screening test, such as the Mini Mental State Examination, a valid questionnaire to measure cognitive impairment [72, 73].

A final limitation in this study is the lack of an active control. Current research demonstrates that older adults who spend regular and meaningful time on the computer have a lower risk of developing mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia [74]. Though the mechanism behind this is currently unknown, researchers Krell-Roesch and colleagues [47] attribute computer use with an increased demand for specific technical and manual skills which may have a protective effect against cognitive decline. Therefore, it is difficult to decipher whether it is the Neurotracker itself, or the use of a computer-based intervention, that is responsible for the gains in cognition measured in this study. Future research would benefit from employing an active control that consists of a Neurotracker experimental group, and a computer-based active control group.

Future Directions

The benefits of enhancement in selective attention, psychomotor speed, and cognitive flexibility as a result of training sessions with the Neurotracker have important implications for future research. Specifically, future research should examine, neurological and physiological changes can may accompany this cognitive enhancement intervention. Mozolic and colleagues [13] provided quantitative evidence that cognitive training is correlated with increased cerebral blood blow to the PFC in older persons following an attentional enhancement intervention. Similar physiology may also be seen following training sessions with the Neurotracker, would could provide a quantitative explanation for the Stroop test improvement demonstrated in this study. The use of neurological imaging and diagnostic tools, to quantitatively assess any changes occurring following 3D-MOT training, would be beneficial.

Future research could also benefit from measuring the effects of 3D-MOT on daily activities requiring attention. In this study, we have demonstrated near-transfer effects from the Neurotracker to the Stroop test, two measurements that are similar in their demands for selective attention and cognitive flexibility. Future research would benefit from demonstrating transfer effects from the Neurotracker to daily tasks that influence independence and quality of life in older adults, such as driving and balance. Legault and Faubert [27] reported transfer effects from perceptual-cognitive training, demonstrating that 3D-MOT training correlated with increased biological motion perception in the healthy older population, indicating that the benefits of the Neurotracker may not be restricted solely to similar assessment test such as the Stroop test. Future research should examine the effects of 3D-MOT training on tasks that tend to decline due to an age-related loss of attention. For example, the Useful Field of View (UFV) test is a valid measurement of driving ability, and a predictor of crash risks [75]. Future research might examine transfer effects from the Neurotracker to the UFV, assessment whether 3D-MOT influences driving ability and safety. Future research would also benefit from measuring whether the gains in attention, cognitive flexibility, and psychomotor speed are sustained in the long term. The current study has demonstrated gains in these areas one week following the end of the Neurotracker intervention. Future research would benefit from assessing whether these gains are maintained in the long term without active engagement in Neurotracker training, or whether sustained 3D-MOT training is necessary to maintain these cognitive benefits.

Conclusions

The current study demonstrated improved performance in older adults on a measure of cognitive flexibility, selective attention, and psychomotor speed as a result of 3D-MOT intervention.Further research is essential to examine structural neuroplasticity and transfer effects from the Neurotracker to daily tasks. Taken together, the results of this study suggest that the Neurotracker may be an effective tool for cognitive-perceptual enhancement in the population of older adults.

References

- Harada CN, Natelson Love MC, Triebel KL (2013) Normal cognitive aging. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine 29: 737–752.

- Murman DL1 (2015) The Impact of Age on Cognition. Semin Hear 36: 111–121. [crossref]

- Kirova A, Bays RB, Lagalwar S (2015) Working memory and executive function decline across normal aging, mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease. BioMed Research International 2015: 748212.

- Salthouse TA (2009) When does age-related cognitive decline begin? Neurobiology of Aging 30: 507–514.

- Turner GR, Spreng RN (2012) Executive functions and neurocognitive aging: Dissociable patterns of brain activity. Neurobiology of Aging 33: 826.

- Eidels A, Townsend JT, Algom D (2009) Comparing perception of Stroop stimuli in focused versus divided attention paradigms: Evidence for dramatic processing differences. Cognition 114: 129–150.

- Karthaus M, Falkenstein M (2016) Functional changes and driving performance in older drivers: Assessment and interventions. Geriatrics 1: 12.

- Richardson ED, Marottoli RA (2003) Visual attention and driving behaviors among community-living older persons. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 58: 832–836.

- Svetina M (2016) The reaction times of drivers aged 20 to 80 during a divided attention driving. Traffic Injury Prevention 17: 810–814.

- Coubard OA, Duretz S, Lefebvre V, Lapalus P, Ferrufino L (2011) Practice of contemporary dance improves cognitive flexibility in aging. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 3: 1–12.

- Aron AR, Monsell S, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW (2004) A compenential analysis of task-switching deficits associated with lesions of left and right frontal cortex. Brain 127: 1561–1573.

- Johnson MK, Mitchell KJ, Raye CL, Greene EJ (2004) An age-related deficit in prefrontal cortical function associated with refreshing information. Psychological Science 15: 127–132.

- Mozolic JL, Hayasaka S, Laurienti PJ (2010) A cognitive training intervention increases resting cerebral blood flow in healthy older adults. Front Hum Neurosci 4: 16.

- Zamroziewicz MK, Zwilling CE, Barbey AK (2016) Inferior prefrontal cortex mediates the relationship between phosphatidylcholine and executive functions in healthy, older adults. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 8: 226.

- Cabeza R, Nyberg L (2000) Imaging cognition II: An empirical review of 275 PET and fMRI studies. J Cogn Neurosci 12: 1–47.

- Milham MP, Erickson KI, Banich MT, Kramer AF, Webb A et al. (2002)Attentional control in the aging brain: insights from an fMRI study of the stroop task. Brain Cogn 49: 277–296.

- Raz N (2000) Aging of the brain and its impact on cognitive performance: Integration of structural and functional findings. In: Craik, F.I.M. and Salthouse, T.A., Eds., The Handbook of Aging and Cognition, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah Pg No: 1–90.

- Solbakk, A., Fuhrmann, A., Furst, A., Hale, L., Oga, T., Chetty, S., Pickard, N, & Knight, R. (2008). Altered prefrontal function with aging: Insights into age-associated performance decline. Brain Res, 1232, 30–47.

- Bherer L, Kramer AF, Peterson MS, Colcombe S, Erickson K (2006) Testing the limits of cognitive plasticity in older adults: Application to attentional control. Acta Psychologica 123: 261–278.

- Kheirbek, M., & Hen, R. (2013). (Radio)active neurogenesis in the human hippocampus. Cell, 153, 1183–1184.

- Valkanova, V., Eguia, Rodriguez R., Ebmeier, K. (2014). Mind over matter – what do we know about neuroplasticity in adults? Int Psychogeriatr 26, 891–909.

- Pylyshyn, Z.W., & Storm, R.W. (1988). Tracking multiple independent targets: Evidence for a parallel tracking mechanism. Spatial Vision, 3: 179–197.

- Scholl BJ (2009) What have we learned about attention from multiple-object tracking (and vice-versa)? In Computation and Pylyshyn (pp. 49–77). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Romeas T, Guldner A, Faubert J (2016) 3D-multiple object tracking training task improves passing decision-making accuracy in soccer players. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 22: 1–9.

- Faubert J, Sidebottom L (2012) Perceptual-cognitive training of athletes. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology 6: 85–102.

- Faubert J (2013) Professional athletes have extraordinary skills for rapidly learning complex and neutral dynamic visual scenes. Scientific Reports 3: 1154.

- Legault I, Faubert J (2012) Perceptual-cognitive training improves biological motion perception: evidence for transferability of training in healthy aging. Neuroreport 23: 469–473.

- Legault I, Allard R, Faubert J (2013) Healthy older observers show equivalent perceptual-cognitive training benefits to young adults for multiple object tracking. Frontiers of Psychology 4: 323.

- Oshin V (2016) 3D multiple object tracking boosts working memory span: Implications for cognitive training in military populations. Military Psychology 28: 353–360.

- Parsons, B., Magill, T., Boucher, A., Zhang, M., Zogbo, K., Bérubé, S., . . . Faubert, J. (2014). Enhancing cognitive function using perceptual-cognitive training. Clinical EEG and Neuroscience, 47, 37–47.

- Drew T, McCollough AW (2009) Attentional enhancement during multiple-object tracking. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 16: 411–417.

- Colzato LS, van Leeuwen PJA, van den Wildenberg WPM, Hommel B (2010) DOOM’d to switch: Superior cognitive flexibility in players of first person shoot games. Frontiers of Psychology 1: 8.

- Vul E, Frank M, Alvarez G, Tenenbaum J (2009) Explaining human multiple object tracking as resource constrained approximate inference in a dynamic probabilistic model. Advances in neural information processing systems 22: 1955–1963.

- Trick LM, Perl T, Sethi N (2005) Age-related differences in multiple-object tracking. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 60: 102–105. [crossref]

- Tomasi D, Volkow ND (2012) Aging and functional brain networks. Molecular psychiatry 17: 471–558.

- Andrade C, Radhakrishnan R (2009) The prevention and treatment of cognitive decline and dementia: An overview of recent research on experimental treatments. Indian Journal of Psychiatry 51: 12–25.

- Konar A, Singh P, Thakur MK (2016) Age-associated cognitive decline: Insights into molecular switches and recovery avenues. Aging Disorders 7: 121–129.

- Faubert J (2001) Motion parallax, stereoscopy, and the perception of depth: Practical and theoretical issues. In B. Javidi, F. Okano (Eds.), Three-dimensional video and display: Devices and systems (CR76, pp. 168–191), Proceedings of SPIE.

- Hairston WD, Maldjian JA (2009) An adaptive staircase procedure for the E-prime programming environment. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 93: 104–108.

- Allampati S, Duarte-Rojo A, Tacker LR, Patidar KR, White MB, et al. (2016) Diagnosis of minimal hepatic encephalopathy using Stroop EncephalApp: A multicenter US-based norm-based study. American Journal of Gastroenterology 111: 78–86.

- Barbarotto R, Laiacona M, Frosio R, Vecchio M, Farinato A, et al. (1998) A normative study on visual reaction times and two Stroop colour-word tests. Ital J Neurol Sci 19: 161–170.

- Bench CJ, Frith CD, Grasby PM, Friston KJ, Paulesu E, et al. (1993) Investigations of the functional anatomy of attention using the Stroop test. Neuropsychologia 31: 907–922. [crossref]

- Macleod, C. (1991). Half a century of research on the Stroop effect: An integrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 109(2), 163–203.

- Bajaj JS, Heuman DM, Sterling RK, Sanyal AJ, Siddiqui M, et al. (2016) Validation of EncephalApp, smartphone-based Stroop test, for the diagnosis of covert hepatic encephalopathy. Clinical Gastroenterolgy Hepatology 13: 1828–1835.

- Rosenbaum AM, Arnett PA, Bailey CM, Echemendia RJ (2006) Neuropsychological assessment of sports-related concussion: Measuring clinically significant change. (pp. 137–169). Boston, MA: Springer US.

- Ball K, Berch DB, Helmers KF, Jobe JB, Leveck MD, et al. (2002) Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly Study Group. Effects of cognitive training interventions with older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Jama 288: 2271–2281.

- Krell-Roesch J, Vemuri P, Pink A, Roberts RO, Stokin GB, et al. (2017). Association between mentally stimulating activities in late life and the outcome of incident mild cognitive impairment, with an analysis of the APOE e4 genotype. JAMA Neurology 74: 332–338.

- Royston, P. (1992). Approximating the Shapiro-Wilk W-test for non-normality. Statistics and Computing, 2, 117–119.

- West SG, Finch JF, Curran PJ (1995) Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. In: R.H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues and applications Newbery Park, CA: Sage. Pg No: 56–75.

- Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences (2nd edn). Hillsdale, N.J: L. Erlbaum Associates.

- Anguera JA, Boccanfuso J, Rintoul JL, Al-Hashimi RO, Faraji F, et al. (2013) Video game training enhances cognitive control in older adults. Nature 501: 97–101.

- Ball K, Edwards JD, Ross LA (2007) The impact of speed of processing training on cognitive and everyday functions. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 62: 19–31.

- Basak C, Boot WR, Voss MW, Kramer AF (2008) Can training in a real-time strategy video game attenuate cognitive decline in older adults? Psychology and Aging 23: 765–777.

- Parsons B, Magill T, Boucher A, Zhang M, Zogbo K, et al. (2016) Enhancing cognitive function using perceptual-cognitive training. Clinical EEG and Neuroscience 47: 37–47.

- Envig A, Fjell AM, Westlye LT, Moberget T, Sundseth O, et al. (2010) Effects of memory training on cortical thickness in the elderly. Neuroimage 52: 1667–1676.

- Bherer L, Kramer AF, Peterson MS, Colcombe S, Erickson K, et al. (2008) Transfer effects in task-set cost and dual-task cost after dual-task training in older and younger adults: Further evidence for cognitive plasticity in attentional control in late adulthood. Experimental Aging Research 34: 188–219.

- Bisson E, Contant B, Sveistrup H, Lajoie Y (2007) Functional balance and dual-task reaction times in older adults are improved by virtual reality and biofeedback training. CyberPsychology & Behavior 10: 16–23.

- Fragala MS, Beyer KS, Jajtner AR, Townsend JR, Pruna GJ, et al. (2014). Resistance exercise may improve spatial awareness and visual reaction in older adults. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 28, 2079–2087.

- Gesta-Martino E, Ott BR, Heindel WC (2004) Interactions between phasic alerting and spatial orienting: Effects of normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology 18: 258–268.

- Gunstad J, Paul RH, Brickman AM, Cohen RA, Arns M, et al. (2006) Patterns of cognitive performance in middle-aged and older adults: A cluster analytic examination. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology 19: 59–64.

- Zhou S, Fan J, Lee TMC, Wang C, Wang K (2011) Age-related differences in attentional networks of alerting and executive control in young, middle-aged, and older Chinese adults. Brain and Cognition 75: 205–210.

- Clark R, Freedberg M, Hazeltine E, Voss MW (2015) Are there age-related differences in the ability to learn configural responses? PLoS One 10.

- Kliegl R, Smith J, Baltes PB (1990) On the locus and process of magnification of age differences during mnemonic training. Developmental Psychology 26: 894–904.

- Yang L, Krampe RT, Baltes PB (2006) Basic forms of cognitive plasticity extended into the oldest-old: Retest learning, age, and cognitive functioning. Psychology and Aging 21: 372–378.

- Singer T, Lindenberger U, Baltes PB (2003) Plasticity of memory for new learning in very old age: a story of major loss? Psychol Aging 18: 306–317. [crossref]

- Clarkson-Smith L, Hartley AA (1990) The game of bridge as an exercise in working memory and reasoning. J Gerontol 45: 233–238. [crossref]

- Gajewski PD, Falkenstein M (2016) Physical activity and neurocognitive functioning in aging – a condensed updated review. European Review of Aging and Physical Activity: Official Journal of the European Group for Research into Elderly and Physical Activity 13: 1.

- Williams K, Kemper S (2010) Exploring interventions to reduce cognitive decline in aging. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 48: 42–51.

- Collie A, Maruff P, Darby DG, McStephen M (2003) The effects of practice on the cognitive test performance of neurologically normal individuals assessed at brief test-retest intervals. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 9: 419–428.

- Goldberg TE, Harvey PD, Wesnes KA, Snyder PJ, Schneider LS (2015) Practice effects due to serial cognitive assessment: Implications for preclinical alzheimer’s disease randomized controlled trials. Alzheimer’s & Dementia (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 1: 103–111.

- Rajan KB, Wilson RS, Weuve J, Barnes LL, Evans DA (2015) Cognitive impairment 18 years before clinical diagnosis of alzheimer disease dementia. Neurology 85: 898.

- O’Bryant SE, Humphreys JD, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, Graff-Radford NR, et al. (2008) Detecting dementia with the mini-mental state examination in highly educated individuals. Archives of Neurology 65: 963–967.

- Santacruz KS, Swagerty D (2001) Early diagnosis of dementia. American Family Physician 63: 703.

- Liapis J, Harding KE (2017) Meaningful use of computers has a potential therapeutic and preventative role in dementia care: A systematic review. Australasian Journal on Aging 36: 299–307.

- Wood JM, Owsley C (2014) Useful field of view test. Gerontology 60: 315–318. [crossref]